Validating PfATP4 as a High-Value Antimalarial Target: A Roadmap for Yeast Model Systems

The Plasmodium falciparum cation transporter PfATP4 is a leading antimalarial drug target, with inhibition causing rapid parasite death.

Validating PfATP4 as a High-Value Antimalarial Target: A Roadmap for Yeast Model Systems

Abstract

The Plasmodium falciparum cation transporter PfATP4 is a leading antimalarial drug target, with inhibition causing rapid parasite death. However, validating its function and screening for inhibitors has been hampered by an inability to express functional protein in heterologous systems like yeast, a challenge underscored by recent discoveries of its essential binding partner, PfABP. This article provides a comprehensive methodological framework for researchers aiming to establish a yeast model for PfATP4. We cover the foundational biology of PfATP4 and its regulators, strategic design for heterologous expression, troubleshooting of persistent expression hurdles, and a suite of functional assays for validating pump activity and inhibitor sensitivity. By synthesizing the latest structural insights and known resistance mutations, this guide aims to accelerate the development of a much-needed platform for next-generation antimalarial discovery.

Deconstructing PfATP4: Essential Biology and a Newly Discovered Regulator

The Critical Role of PfATP4 in Parasite Sodium Homeostasis and Survival

The Plasmodium falciparum Cation ATPase 4 (PfATP4) has emerged as one of the most promising antimalarial drug targets in recent decades, representing a critical vulnerability in the parasite's physiological machinery. This P-type ATPase transporter is localized to the parasite plasma membrane where it functions primarily as a sodium efflux pump, maintaining the low intracellular sodium concentration essential for parasite survival [1] [2]. The parasite inhabits a challenging ionic environment within the host erythrocyte, where sodium concentrations approximate those of blood plasma (~130-135 mM) due to parasite-induced new permeability pathways in the host cell membrane [1] [3]. Despite this high extracellular sodium concentration, the parasite maintains its cytosolic sodium at approximately 10 mM, establishing a substantial inward sodium electrochemical gradient that serves as an energy source for nutrient uptake [1]. PfATP4 is postulated to function as a Na+/H+-ATPase, extruding sodium ions from the parasite in exchange for protons, thereby simultaneously regulating intracellular sodium concentration and imposing an "acid load" on the parasite [2] [4]. The critical nature of this homeostatic function is evidenced by the fact that PfATP4 inhibition triggers rapid sodium dysregulation, parasite swelling, and ultimately parasite death [2] [5].

The validation of PfATP4 as a drug target represents a case study in modern antimalarial discovery. Unlike traditional target-based approaches, PfATP4 emerged from phenotypic screening campaigns followed by resistance mutation mapping [1] [6]. This protein has demonstrated remarkable "druggability," with multiple structurally distinct chemical classes - including spiroindolones, pyrazoleamides, aminopyrazoles, and dihydroisoquinolones - converging on PfATP4 as their primary target [1] [6] [4]. The clinical potential of targeting PfATP4 was demonstrated by cipargamin (KAE609), a spiroindolone that progressed through Phase II clinical trials with favorable results [1] [4]. However, the emergence of resistance mutations in PfATP4 has highlighted the need for deeper understanding of its structure and function to design next-generation inhibitors [3] [7].

Physiological Function of PfATP4 in Sodium Homeostasis

Ionic Challenges of the Intraerythrocytic Environment

The Plasmodium falciparum parasite faces extraordinary ionic challenges during its intraerythrocytic lifecycle. Upon invading a human red blood cell, the merozoite transitions from the high-sodium environment of blood plasma to the low-sodium, high-potassium environment of the host erythrocyte cytosol [1]. However, this relatively stable environment is short-lived. Approximately 12-18 hours after invasion (at the ring stage), the parasite induces "New Permeability Pathways" (NPPs) in the host erythrocyte membrane that dramatically increase permeability to various solutes, including sodium and potassium [1] [3]. The resulting sodium influx overwhelms the host erythrocyte's ouabain-sensitive Na+/K+-ATPase, leading to a progressive increase in erythrocyte cytosolic sodium concentration that eventually equilibrates with the extracellular plasma [1]. The intraerythrocytic parasite is further enclosed by the parasitophorous vacuole membrane, which contains high-conductance broad-selectivity channels thought to render it freely permeable to ions at the metabolically active trophozoite stage [1] [3]. Consequently, the parasite is bathed in a high-sodium environment at the parasitophorous vacuole space, creating a substantial challenge for maintaining ionic homeostasis.

PfATP4-Mediated Sodium Regulation

To survive in this hostile ionic environment, the parasite maintains a low cytosolic sodium concentration (~10 mM) through the active extrusion of sodium ions via PfATP4 [1] [2]. The sodium electrochemical gradient maintained by PfATP4 is substantial, combining the concentration gradient with the parasite's inwardly negative membrane potential (approximately -95 mV) [1]. This gradient serves not only to protect the parasite from sodium toxicity but also provides energy for secondary transport processes. A key example is the Na+-coupled phosphate transporter PfPiT, which relies on the sodium gradient established by PfATP4 to import essential inorganic phosphate for nucleotide, nucleic acid, and phospholipid synthesis [8]. This relationship underscores the integrated nature of ion regulation and nutrient acquisition in the parasite.

Direct evidence for PfATP4's role in sodium extrusion comes from experiments demonstrating orthovanadate-sensitive Na+ efflux from pre-loaded parasites against a steep concentration gradient [1]. Additionally, parasites with resistance-conferring mutations in PfATP4 show altered sodium regulation when exposed to PfATP4 inhibitors [2]. The essential nature of PfATP4-mediated sodium homeostasis is further highlighted by the observation that PfATP4 inhibitors trigger a rapid increase in intraparasitic sodium concentration and pH, leading to parasite swelling and eventual lysis [2] [5]. This distinctive biochemical signature has become a hallmark of PfATP4-targeting compounds and provides a reliable method for classifying compounds with this mechanism of action.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of PfATP4 Function

| Characteristic | Description | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Localization | Parasite plasma membrane | Immunofluorescence and epitope tagging [1] |

| Ion Specificity | Na+ extrusion, potentially in exchange for H+ | Na+ efflux assays, intracellular pH measurements [1] [2] |

| Intracellular [Na+] | ~10 mM in parasite cytosol vs. ~130 mM in host erythrocyte | Fluorescent indicator measurements [1] |

| Inhibitor Sensitivity | Orthovanadate-sensitive; targeted by multiple chemotypes | ATPase activity assays, resistance mutation mapping [1] [6] |

| Essential Function | Critical for parasite survival | Transposon mutagenesis, inhibitor studies [8] [2] |

Yeast Models in PfATP4 Research: Methodologies and Applications

Yeast as a Heterologous System for Malaria Research

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has emerged as a powerful heterologous system for studying Plasmodium falciparum proteins, including PfATP4 and other essential parasite transporters. Yeast offers several advantages for malaria research: well-established genetic tools, rapid growth, and the ability to functionally express membrane proteins that often prove challenging in other expression systems [8]. Additionally, yeast shares fundamental cellular processes with Plasmodium while lacking the complex ethical and technical challenges associated with continuous parasite culture. The utility of yeast models extends beyond basic functional characterization to include high-throughput drug screening against specific parasite targets, enabling rapid identification of novel inhibitors without immediate need for parasite culture [8].

A key strength of yeast-based systems is the ability to create conditionally dependent strains where parasite proteins replace essential yeast proteins, creating assays where yeast survival directly reports on the function of the parasite protein of interest. This approach has been successfully applied to multiple Plasmodium transporters, including the equilibrative nucleoside transporter PfENT1 and the sodium-coupled phosphate transporter PfPiT [8]. In these engineered strains, chemical inhibition of the parasite transporter results in measurable growth defects, providing a straightforward readout for inhibitor identification and characterization.

Experimental Workflow for Yeast-Based PfPiT Studies

The application of yeast models to study sodium-coupled transport in Plasmodium is exemplified by recent work on PfPiT, which depends on the sodium gradient established by PfATP4. The experimental workflow involves:

Strain Engineering: The parent yeast strain EY918, which lacks four of the five endogenous phosphate transporters and relies solely on Pho84 for phosphate uptake, serves as the starting point [8]. Through targeted gene replacement, the PHO84 coding sequence is replaced with a yeast codon-optimized version of PfPiT, creating a strain where phosphate uptake and consequently viability are entirely dependent on PfPiT function [8].

Functional Characterization: The PfPiT-dependent strain is subjected to radioactive phosphate uptake assays to determine kinetic parameters (Km = 56 ± 7 μM in 1 mM NaCl, decreasing to 24 ± 3 μM in 25 mM NaCl) and ion dependence, confirming its function as a sodium-coupled phosphate transporter [8].

Growth Assay Development: Conditions are established under which yeast growth is strictly dependent on phosphate uptake mediated by PfPiT, creating a 22-hour growth assay suitable for high-throughput screening [8].

Compound Screening: Libraries of compounds are screened for inhibition of PfPiT-dependent yeast growth, followed by confirmation of direct transport inhibition using radioactive uptake assays [8].

This workflow has already proven successful in identifying specific PfPiT inhibitors from small compound collections, demonstrating the utility of yeast-based systems for antimalarial discovery [8].

Yeast-Based Screening Workflow for Sodium-Coupled Transporters

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for PfATP4 and Associated Transport Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae EY918 strain | Parent strain with four endogenous phosphate transporters knocked out | Base for engineering PfPiT-dependent strain [8] |

| Yeast codon-optimized PfPiT | Heterologous expression of parasite transporter in yeast | Creation of phosphate uptake-dependent strain [8] |

| Radioactive [³²P]phosphate | Direct measurement of phosphate transport kinetics | Determination of Km and ion dependence [8] |

| Synthetic complete media with variable phosphate | Controlled phosphate availability for growth assays | PfPiT-dependent growth condition optimization [8] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 for P. falciparum | Endogenous tagging and gene editing in parasites | C-terminal 3×FLAG tagging of PfATP4 for native purification [3] |

| PfATP4 inhibitors (Cipargamin, PA21A092) | Positive controls for PfATP4 disruption | Validation of Na+ homeostasis assays [3] [2] |

| Na+-depleted culture media | Manipulation of extracellular sodium environment | Testing Na+ dependence of physiological processes [2] |

Structural Insights into PfATP4 Function and Inhibition

CryoEM Structure Reveals Novel Features

For years, attempts to determine the high-resolution structure of PfATP4 using heterologous expression systems proved unsuccessful, hindering structure-based drug design [3] [7]. This barrier was recently overcome through innovative approaches that enabled the endogenous purification of PfATP4 directly from CRISPR-engineered P. falciparum parasites cultured in human red blood cells [3]. The resulting 3.7 Å resolution cryoEM structure represents a landmark achievement that provides unprecedented insights into PfATP4 organization and function.

The structure confirms that PfATP4 contains the five canonical domains characteristic of P2-type ATPases: the transmembrane domain (TMD), nucleotide-binding (N) domain, phosphorylation (P) domain, actuator (A) domain, and extracellular loop (ECL) domain [3]. The TMD consists of 10 helices arranged in three clusters (TM1-2, TM3-4, TM5-10), with the ion-binding site located between TM4, TM5, TM6, and TM8 [3]. Although the resolution was insufficient to directly visualize bound Na+ ions, the arrangement of coordinating sidechains closely matches that of cation-bound SERCA (sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase), suggesting the structure represents a Na+-bound state [3]. The ATP-binding site between the N and P domains shows generally conserved architecture with other P2-type ATPases, though notable differences in sidechain arrangements were observed that may have implications for inhibitor specificity [3].

Discovery of PfABP: A Novel Regulatory Protein

Perhaps the most surprising revelation from the endogenous PfATP4 structure was the discovery of a previously unknown interacting protein, designated PfATP4-Binding Protein (PfABP) [3] [7]. This apicomplexan-specific protein forms a conserved interaction with TM9 of PfATP4 and was found to be the third most abundant protein in tryptic digest mass spectrometry of purified PfATP4 samples [3]. Functional studies demonstrated that loss of PfABP leads to rapid degradation of PfATP4 and parasite death, indicating its essential role in stabilizing the transporter [3] [7]. This discovery opens entirely new avenues for antimalarial development, as PfABP represents a potential drug target that may be less prone to resistance mutations than PfATP4 itself [7].

PfATP4 Function in Parasite Sodium Homeostasis

Mapping Resistance Mutations Informs Drug Design

The endogenous PfATP4 structure has provided a crucial framework for understanding the structural basis of drug resistance. When resistance-conferring mutations identified in both laboratory-selected strains and clinical isolates are mapped onto the structure, striking patterns emerge [3]. Mutations conferring resistance to the spiroindolone cipargamin (such as G358S/A) primarily cluster around the proposed sodium-binding site within the TMD [3]. Structural analysis suggests that the G358S mutation may block cipargamin binding by introducing a serine sidechain into the inhibitor binding pocket [3]. Similarly, the A211V mutation that arose under pyrazoleamide (PA21A092) pressure is located within TM2 adjacent to the ion-binding site [3]. Interestingly, parasites with the A211V mutation show increased susceptibility to cipargamin, suggesting complex interactions between different inhibitor classes and their binding sites [3] [6].

Table 3: Clinically Relevant PfATP4 Mutations and Their Impact

| Mutation | Compound Selector | Structural Location | Proposed Resistance Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| G358S/A | Cipargamin (Spiroindolone) | TM3, near Na+ binding site | Steric hindrance of inhibitor binding [3] |

| A211V | PA21A092 (Pyrazoleamide) | TM2, adjacent to ion-binding site | Altered binding pocket conformation [3] [6] |

| I203L | GNF-Pf4492 (Aminopyrazole) | TM2 | Modified inhibitor access pathway [6] |

| A187V | GNF-Pf4492 (Aminopyrazole) | TM1/TM2 interface | Allosteric effects on binding site [6] |

| S374R | MB14 | Not specified in results | Reduced inhibitor affinity [2] |

PfATP4 Inhibitors: Mechanisms and Experimental Assessment

Diverse Chemotypes Converge on PfATP4

PfATP4 represents a remarkable example of target convergence, where multiple structurally distinct chemical classes have been identified that disrupt its function [1] [6] [4]. These include:

Spiroindolones (e.g., cipargamin/KAE609): This class progressed to Phase II clinical trials and demonstrated faster parasite clearance than standard artemisinin treatments [1] [4]. Spiroindolones trigger rapid Na+ accumulation and parasite swelling [2].

Pyrazoleamides (e.g., PA21A092): These compounds show potent antimalarial activity and disrupt Na+ homeostasis similarly to spiroindolones, though resistance mutations map to distinct but adjacent regions of PfATP4 [3] [6].

Aminopyrazoles (e.g., GNF-Pf4492): Identified through phenotypic screening, this class selects for resistance mutations in PfATP4 (A187V, I203L, A211T) and produces the characteristic Na+ dysregulation phenotype [6].

Dihydroisoquinolones (e.g., (+)-SJ733): This class shares phenotypic effects with other PfATP4 inhibitors and shows cross-resistance patterns indicating a shared target [1].

Additionally, screening of the Medicines for Malaria Venture's 'Malaria Box' and 'Pathogen Box' revealed that 7% and 9% of antimalarial compounds in these collections, respectively, exhibit the biochemical signature of PfATP4 inhibition [2]. This remarkable convergence underscores both the essential nature of PfATP4 function and its unique "druggability."

Mechanism of Action: From Ionic Disruption to Parasite Death

The pathway from PfATP4 inhibition to parasite death involves a cascade of biochemical and cellular events:

Direct Inhibition: Compounds bind to PfATP4, blocking its Na+ extrusion capability [2] [5].

Sodium Accumulation: Intracellular Na+ concentration rises rapidly due to continued influx through various pathways [1] [2].

pH Perturbation: As PfATP4 may function as a Na+/H+ exchanger, inhibition leads to cytosolic alkalinization [2].

Osmotic Imbalance: Elevated Na+ concentration draws water into the parasite, causing swelling [2] [5].

Parasite Lysis: Severe swelling culminates in membrane rupture and parasite death [2] [5].

This mechanism is distinct from traditional antimalarials that target metabolic pathways or hemozoin formation, offering potential against multidrug-resistant parasites [5].

Beyond Trophozoite Death: Disruption of Parasite Egress

Recent research has revealed that PfATP4 inhibitors exert additional effects beyond killing intraerythrocytic trophozoites. Several PfATP4-associated compounds from the Malaria Box and Pathogen Box disrupt the schizont-to-ring transition by blocking merozoite egress from infected erythrocytes [2]. Detailed investigation demonstrates that these compounds prevent egress rather than invasion, and appear to work by inhibiting the activation of protein kinase G (PfPKG), an essential regulator of the egress cascade [2]. This effect is attenuated in Na+-depleted media and in parasites with resistance-conferring PfATP4 mutations, establishing a direct link between PfATP4 function and egress regulation [2]. This expanded understanding of PfATP4's role throughout the parasite lifecycle enhances its attractiveness as a drug target.

The critical role of PfATP4 in parasite sodium homeostasis and survival is now firmly established through multiple lines of evidence: physiological studies, genetic validation, structural biology, and inhibitor phenotyping. The convergence of diverse chemical classes on this target underscores its fundamental importance to parasite biology. Recent advances - particularly the endogenous PfATP4 structure and discovery of PfABP - have opened new avenues for drug development that may overcome existing resistance challenges.

The integration of yeast-based screening models with parasite studies creates a powerful pipeline for identifying and optimizing novel inhibitors, not only of PfATP4 itself but also of dependent transport systems like PfPiT. As drug resistance continues to undermine current antimalarial therapies, targeting PfATP4 and associated proteins offers a promising strategy for next-generation treatments that exploit essential ion regulatory pathways in the malaria parasite.

The pursuit of validating PfATP4, a sodium efflux pump in Plasmodium falciparum, as a premier antimalarial drug target has been significantly hampered by a persistent and critical roadblock: the repeated failure to achieve its functional expression in heterologous systems. This review objectively compares the unsuccessful attempts at heterologous expression against the successful application of endogenous parasite studies and surrogate yeast models. We summarize quantitative biochemical data gathered from native sources, detail the experimental protocols that ultimately proved successful, and situate these findings within the broader context of using yeast-based research to validate antimalarial targets. The analysis reveals that the inherent molecular complexity of PfATP4, including its recently discovered essential binding partner, fundamentally limited the utility of heterologous systems and directed the field toward more physiologically relevant expression platforms.

The Heterologous Expression Bottleneck: A Persistent Challenge

The functional characterization of any membrane protein, including its biochemical properties, transport kinetics, and inhibitor sensitivity, typically relies on the ability to express and purify the protein in a heterologous system. For PfATP4, this approach was deemed essential for structural studies and high-throughput drug screening.

However, multiple independent laboratories have consistently reported an inability to express functional PfATP4 in standard heterologous systems such as Xenopus laevis oocytes and presumably yeast or bacterial cultures [9]. One study explicitly notes that while an initial report described some success in oocytes, subsequent efforts to replicate this work were unsuccessful, stating that "at least one other laboratory has been unable to reproduce this finding or to achieve functional expression of the transporter" [9]. This reproducibility crisis significantly stalled the mechanistic study of PfATP4 and the direct biochemical validation of proposed inhibitors.

The recent discovery of a previously unknown protein partner, PfATP4-Binding Protein (PfABP), has provided a compelling explanation for these historical failures [3] [7] [10]. This essential modulator was found to co-purify with PfATP4 directly from parasite-infected human red blood cells. Crucially, experiments showed that the loss of PfABP led to the rapid degradation of PfATP4 and parasite death, indicating its critical role in stabilizing the pump [7] [10]. Its absence in heterologous expression systems likely explains the instability and lack of function of recombinant PfATP4.

Table 1: Documented Challenges in Heterologous Expression of PfATP4

| Heterologous System | Reported Outcome | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Xenopus laevis Oocytes | Non-functional expression / Unreproducible | Initial report of Ca²⁺-dependent ATPase activity could not be replicated by other labs [9]. |

| Yeast/Bacterial Systems | Implied failure | Lack of published success and noted "inability to achieve functional expression in a heterologous system" [11]. |

Successful Endogenous Characterization: A Path to Validation

Faced with the heterologous expression barrier, researchers pivoted to studying PfATP4 directly from its native environment—the Plasmodium falciparum parasite. This approach yielded the first high-resolution structural data and definitive biochemical characterization.

Protocol 1: Endogenous Protein Purification and Cryo-EM from Parasites

- Parasite Culture: CRISPR-Cas9 was used to insert a 3×FLAG epitope tag at the C-terminus of the PfATP4 gene in Dd2 P. falciparum parasites [3].

- Membrane Preparation: PfATP4 was affinity-purified directly from parasites cultured in hundreds of liters of human red blood cells [10].

- Functional Assay: The purified protein was confirmed to exhibit Na⁺-dependent ATPase activity that was inhibited by known PfATP4 inhibitors like cipargamin, validating its functionality [3].

- Structure Determination: A 3.7 Å resolution cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) structure was determined from the endogenously purified protein, revealing the overall architecture and the unexpected density for PfABP [3].

Protocol 2: Membrane ATPase Assay in Native Parasite Membranes

- Membrane Preparation: Membranes were isolated from intact asexual blood-stage P. falciparum parasites [9].

- ATPase Activity Measurement: ATP hydrolysis was measured by quantifying inorganic phosphate (Pi) production over time. Na⁺-dependent activity was isolated by comparing Pi production in high (152 mM) vs. low (2 mM) Na⁺ conditions, with choline as a substitute cation [9].

- Inhibitor Sensitivity: The "PfATP4-associated ATPase activity" was defined as the fraction of Na⁺-dependent ATPase activity that was sensitive to inhibition by 500 nM cipargamin. This assay confirmed PfATP4 as the direct target for multiple chemical classes [9].

Quantitative Biochemical Profile from Native Studies

The endogenous characterization of PfATP4 provided the first direct kinetic and biochemical data, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Biochemical Properties of Native PfATP4

| Biochemical Parameter | Experimental Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Apparent Kₘ for ATP | 0.2 mM | Measured in parasite membrane preparations [9]. |

| Apparent Kₘ for Na⁺ | 16-17 mM | Measured in parasite membrane preparations [9]. |

| Inhibitor Potency (Cipargamin) | IC₅₀ in the nanomolar range | Inhibited Na⁺-dependent ATPase activity in WT parasite membranes; potency reduced in PfATP4-mutant parasites [9]. |

| Transport Coupling | Na⁺ efflux / H⁺ influx (proposed) | Inhibition leads to increased cytosolic [Na⁺] and increased cytosolic pH [4]. |

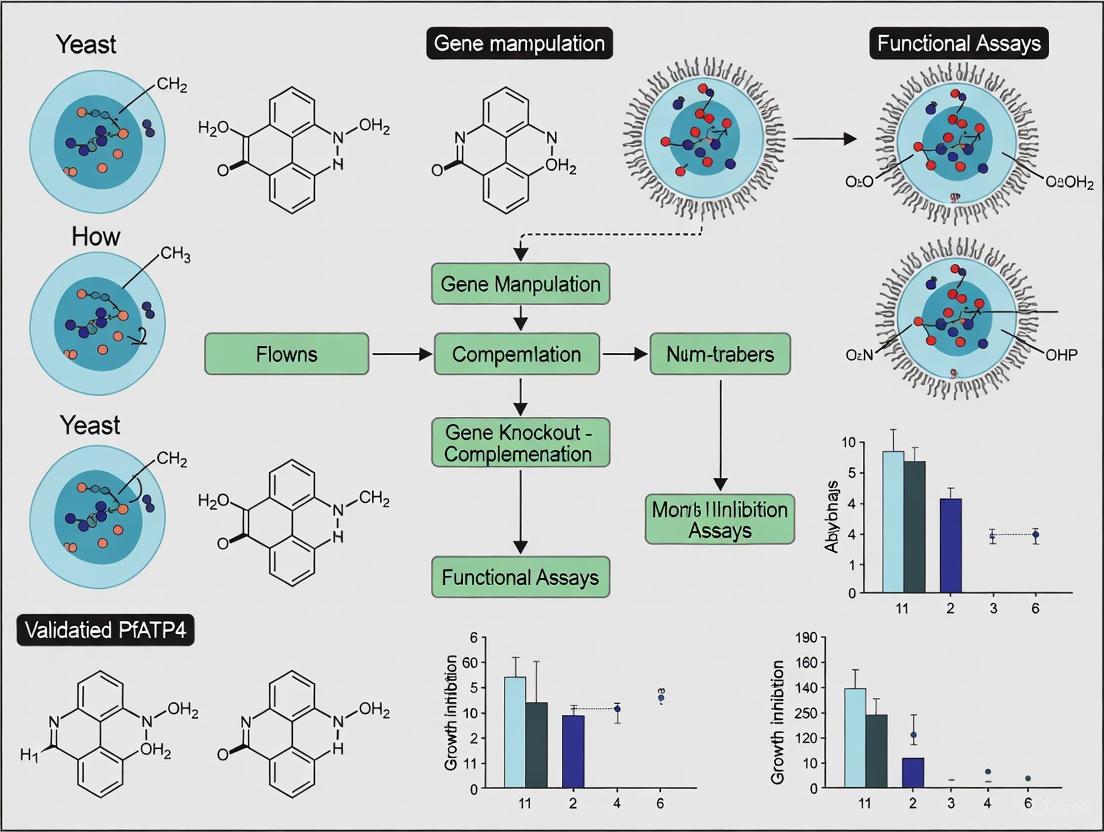

Figure 1: A comparative workflow diagram illustrating the failed heterologous expression path versus the successful endogenous study path for PfATP4. The discovery of PfABP provided the key explanation for the initial failures.

The Yeast Model Alternative: A Surrogate Success Story

While heterologous expression of PfATP4 itself failed, the use of yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) as a surrogate model for antimalarial target validation has proven highly successful for other essential Plasmodium membrane transporters. The case of the phosphate transporter PfPiT serves as an exemplary contrast.

Experimental Protocol for Yeast-Based Drug Screening

Protocol: Developing a Yeast Growth Assay for PfPiT Inhibitor Screening

- Strain Engineering: The parent yeast strain EY918, which has four of its five endogenous phosphate transporters knocked out and relies solely on Pho84 for viability, was used [8].

- Gene Replacement: A yeast codon-optimized gene for PfPiT was synthesized. Genome editing was used to replace the PHO84 coding sequence with the PfPiT gene, creating a strain where PfPiT was the sole phosphate transporter [8].

- Functional Validation: A radioactive [³²P]phosphate uptake assay confirmed the transporter's function and ion dependence, showing a Km for phosphate of 56 ± 7 μM in 1 mM NaCl [8].

- Growth Inhibition Screen: A robust 22-hour growth assay was developed under conditions where yeast growth was strictly dependent on phosphate uptake via PfPiT. This assay was used to screen compounds for PfPiT-specific inhibition, successfully identifying two hits from a small library [8].

Comparative Analysis: PfATP4 Failure vs. PfPiT Success in Yeast

Table 3: Contrasting Outcomes for Two Malaria Targets in Heterologous Models

| Aspect | PfATP4 in Heterologous Systems | PfPiT in Engineered Yeast |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Outcome | Failure / Non-functional [9] [11] | Successful functional expression [8] |

| Key Enabling Factor | Requires unknown partner PfABP [3] | Functions as a single subunit transporter |

| Ion Dependence | Inferred from native studies (Na⁺) [9] | Directly measured in yeast (Na⁺-coupled) [8] |

| Drug Screening Utility | Not feasible in heterologous systems | Feasible (e.g., 22-h growth assay) [8] |

| Target Validation | Relied on native parasites & genetics [6] [11] | Achieved via surrogate yeast physiology [8] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials derived from the successful endogenous and yeast-based studies, providing a resource for researchers in the field.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PfATP4 and Surrogate Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Source/Example |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Engineered Dd2 Parasites | Allows endogenous tagging and purification of PfATP4 from its native context for structural and biochemical studies. | PfATP4-3×FLAG tagged P. falciparum [3]. |

| EY918 Yeast Strain | Parent strain for engineering surrogate models; lacks four phosphate transporters, allowing dependency on a single introduced transporter. | S. cerevisiae strain with pho86Δ, pho87Δ, pho89Δ, pho90Δ, leu2Δ [8]. |

| PfPiT-Expressing Yeast Strain | Validated surrogate system for high-throughput screening of inhibitors against a essential malaria transporter. | EY918 with PHO84 replaced by yeast-codon-optimized PfPiT [8]. |

| Cipargamin | A leading clinical PfATP4 inhibitor; used as a positive control in membrane ATPase assays and resistance studies. | Synthetic spiroindolone; Na⁺-ATPase inhibitor [9]. |

| Radioactive [³²P]Phosphate | Tracer for direct measurement of phosphate uptake kinetics in engineered yeast strains. | Used to determine Km of PfPiT in yeast [8]. |

Figure 2: A schematic illustrating the molecular rationale for the failure of heterologous PfATP4 expression. The absence of its essential stabilizing partner, PfABP, in the heterologous host leads to the degradation and non-function of the pump.

The historical failure to express PfATP4 in heterologous systems was not a mere technical setback but an instructive lesson in the complexity of malaria parasite biology. It underscored that some Plasmodium proteins do not function as solitary units but within essential, pathogen-specific complexes. The discovery of PfABP from endogenous studies vindicated this "failure," turning it into a discovery that opens a new avenue for antimalarial strategies targeting the PfATP4-PfABP interaction [3] [7].

While the yeast model was not a successful platform for PfATP4 itself, its demonstrated success in functionally expressing and enabling drug screening for other essential targets like PfPiT confirms its immense value in the antimalarial toolkit [8]. The path forward for validating complex antimalarial targets will likely involve a synergistic approach: using endogenous parasite systems for definitive structural and functional studies, while continuing to leverage engineered yeast for targets amenable to surrogate expression. This combined strategy maximizes the strengths of each platform to accelerate the development of novel therapies against a formidable global disease.

The validation of PfATP4, a sodium efflux pump located on the plasma membrane of the Plasmodium falciparum parasite, as a promising antimalarial target, represents a critical frontier in the battle against malaria [12] [3]. This P-type ATPase is essential for parasite survival, maintaining low intracellular sodium concentrations in the face of high sodium levels in the host bloodstream [7] [13]. The strategic inhibition of PfATP4 by novel drug candidates such as Cipargamin and PA21A092 causes rapid parasite death, underscoring its therapeutic potential [12] [14]. However, the parasite's notorious ability to develop resistance through mutations in PfATP4 has necessitated a deeper, structural understanding of this target [3] [15].

Research models, particularly yeast-based systems, have historically been instrumental in deconstructing the biology of complex pathogenic proteins. Yeast offers a tractable eukaryotic chassis for expressing and characterizing parasite proteins, allowing for controlled genetic manipulation and high-throughput functional assays [16]. The broader thesis of using yeast model research to validate PfATP4 gains profound significance in this context. It provides a platform not only to study the pump's inherent function and drug inhibition but also to dissect the impact of resistance mutations. The recent, groundbreaking discovery of an essential binding partner, PfATP4-Binding Protein (PfABP), introduces a new variable into this equation [12] [3]. This paradigm shift suggests that future validation efforts in yeast must now account for this stabilizing partner, potentially requiring the co-expression of both proteins to accurately recapitulate the native, functional complex found within the malaria parasite.

Structural & Functional Comparison: PfATP4 With and Without PfABP

The recent elucidation of the high-resolution 3.7 Å cryoEM structure of PfATP4, purified endogenously from CRISPR-engineered parasites, has fundamentally altered our perception of this drug target [12] [3]. The most striking revelation was the identification of a previously unknown protein, PfABP, firmly bound to TM9 of PfATP4's transmembrane domain (TMD) [12] [3]. PfABP is a conserved, apicomplexan-specific protein of unknown function, now recognized as an essential modulator [14]. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of PfATP4's key characteristics in the presence and absence of its binding partner.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of PfATP4 Properties With and Without PfABP

| Feature | PfATP4 with PfABP (Stabilized State) | PfATP4 without PfABP (Degraded State) |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Stability | Stabilized structure [7] [13] | Rapid degradation of the pump [7] [13] |

| Parasite Viability | Essential for parasite survival [3] [13] | Leads to parasite death [3] [13] |

| Structural State | Na+-bound state conformation; Conserved TMD with 10 helices [12] | Not applicable (protein degraded) |

| Drug Target Profile | Primary target for Cipargamin & PA21A092; Resistance mutations present [12] | Not a viable target (parasite dead) |

| Regulatory Role | Likely modulatory interaction, fine-tuning activity [3] | No regulatory function |

This comparative data underscores PfABP's non-redundant role as a stabilizing factor. Experimentally, the loss of PfABP leads directly to the rapid degradation of the PfATP4 sodium pump and, consequently, the death of the parasite, highlighting that the PfATP4-PfABP complex is the biologically relevant unit for drug targeting [7] [13]. Furthermore, because PfABP appears to be more conserved and less prone to mutations than PfATP4 itself, targeting the interaction interface offers a promising strategy to circumvent existing resistance mechanisms [7] [15].

Experimental Protocols for Key PfABP-PfATP4 Interaction Studies

Protocol 1: Endogenous Purification and CryoEM Structure Determination

The discovery of PfABP was contingent on a methodology that preserved the native state of PfATP4 within the parasite [7] [13].

- CRISPR-Cas9 Engineering: The C-terminus of the PfATP4 gene in Dd2 P. falciparum parasites was engineered to include a 3×FLAG epitope tag using CRISPR-Cas9 [12] [3].

- Endogenous Purification: The tagged PfATP4 protein was affinity-purified directly from parasites cultured in human red blood cells. This endogenous approach was critical for co-purifying native binding partners [12] [3].

- Functional Validation: The purified protein's activity was confirmed through Na+-dependent ATPase assays, which were inhibited by known PfATP4 inhibitors like PA21A092 and Cipargamin [12] [3].

- CryoEM and Modeling: A 3.7 Å resolution structure was determined using single-particle cryo-electron microscopy [12] [3].

- Identification of PfABP: An unassigned helix interacting with TM9 of PfATP4 was identified. Sequence-independent modeling and a search using findMySequence identified this helix as the C-terminus of the protein PF3D7_1315500, which was named PfABP. Its presence was further confirmed by its status as the third most abundant protein in tryptic digest mass spectrometry of the purified sample [3].

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of PfABP via Knockdown

The essential function of PfABP was established through loss-of-function experiments.

- Genetic Disruption: PfABP expression was suppressed or knocked down in P. falciparum parasites [7] [13].

- Phenotypic Assessment: Parasite viability was monitored following the loss of PfABP. The experiments showed rapid parasite death, establishing PfABP as essential for survival [13] [17].

- Biochemical Analysis: The stability of the PfATP4 protein was assessed following PfABP knockdown. Immunoblotting or similar techniques confirmed that PfATP4 levels collapsed, indicating that PfABP is required for the pump's stability [7] [13].

Visualizing the Discovery and Impact of PfABP

The following diagrams outline the key experimental workflow that led to the discovery of PfABP and the logical relationship between PfABP loss and its fatal consequence for the parasite.

Diagram 1: The experimental workflow for the endogenous structural determination of PfATP4, which was crucial for the discovery of its binding partner, PfABP.

Diagram 2: The causal pathway from the experimental knockdown of PfABP to the death of the parasite, demonstrating PfABP's essential role.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The critical experiments characterizing the PfATP4-PfABP interaction rely on a specific set of reagents and tools. The table below details these key resources, providing a guide for researchers aiming to replicate or build upon these findings.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying PfATP4 and PfABP

| Research Reagent | Function and Application in PfATP4/PfABP Research |

|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Used for endogenous epitope tagging (e.g., 3×FLAG) of PfATP4 in P. falciparum parasites, enabling subsequent purification [12] [3]. |

| 3×FLAG Epitope Tag | An affinity tag inserted at the C-terminus of PfATP4 to facilitate immunoaffinity purification of the native protein complex from parasites [12] [3]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy | The primary technique used to determine the 3.7 Å resolution structure of endogenously purified PfATP4, revealing the bound PfABP [7] [3]. |

| PfATP4 Inhibitors (Cipargamin, PA21A092) | Established chemical tools to functionally validate purified PfATP4 activity in Na+-dependent ATPase assays and study inhibition mechanisms [12] [14]. |

| ModelAngelo & findMySequence | Computational tools used for sequence-independent modeling of the unidentified PfABP helix and for identifying its amino acid sequence within the P. falciparum proteome [3]. |

| Human Red Blood Cells & Culture Medium | The essential native environment for culturing P. falciparum parasites, required for the endogenous purification of correctly assembled and partnered PfATP4 [7] [13]. |

The discovery of PfABP marks a true paradigm shift in the pursuit of PfATP4 as an antimalarial target. It moves the focus from a single target protein to an essential, two-component complex. This new understanding has profound implications for the broader thesis of using models like yeast for target validation. Future work must now incorporate PfABP to create a more physiologically relevant system for studying PfATP4 function, inhibitor binding, and the mechanistic basis of resistance. The spatial organization of known resistance mutations, such as G358S, can now be analyzed in the context of this complete structure, potentially revealing new drug-binding pockets that are less susceptible to resistance [12] [3]. Ultimately, targeting the PfATP4-PfABP interaction interface presents a novel, and potentially more durable, therapeutic avenue. By designing compounds that disrupt this essential partnership, the scientific community can exploit a critical vulnerability in the malaria parasite, offering fresh hope in the global fight against this resilient disease [7] [15].

Cataloging Clinically Relevant Resistance Mutations (e.g., G358S, A211V)

Plasmodium falciparum ATP4 (PfATP4) has emerged as a leading antimalarial target due to its essential function in maintaining sodium homeostasis in the malaria parasite. This P-type ATPase functions as a Na+ efflux pump located on the parasite plasma membrane, exporting Na+ from the parasite cytosol while importing H+ equivalents [1] [18]. The critical nature of this ion regulation is highlighted by the fact that parasites maintain a low cytosolic [Na+] (~10 mM) despite being surrounded by an environment with ~135 mM Na+ in the host erythrocyte cytosol and parasitophorous vacuole [3] [12]. The validation of PfATP4 as a drug target comes from its identification as the target of structurally diverse antimalarial compounds including spiroindolones (e.g., cipargamin), pyrazoleamides (e.g., PA21A092), and dihydroisoquinolones (e.g., (+)-SJ733) [3] [1] [18]. Inhibition of PfATP4 induces rapid parasite death through disruption of intracellular Na+ homeostasis, causing a rise in cytosolic [Na+] that leads to osmotic swelling and parasite clearance [18] [19]. The clinical relevance of this target is further strengthened by the emergence of resistance mutations in PfATP4 under drug pressure both in laboratory settings and in clinical trials [3] [18] [19].

Clinically Relevant PfATP4 Mutations and Their Functional Impact

Comprehensive Mutation Catalog

Research has identified numerous mutations in PfATP4 associated with resistance to various chemotypes. The table below summarizes key clinically relevant mutations, their resistance profiles, and functional consequences.

Table 1: Clinically Relevant PfATP4 Resistance Mutations

| Mutation | Location/ Domain | Resistance Profile | Functional Consequences | Clinical/Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G358S | TM3, near Na+ binding site | Confers high-level resistance to cipargamin and (+)-SJ733 [3] [18] [19] | Reduces PfATP4 affinity for Na+; increases resting cytosolic [Na+]; blocks drug binding [3] [18] | Emerged in 22/25 recrudescent cases in cipargamin Phase 2b trial [18] [19] |

| A211V | TM2, adjacent to ion-binding site | Decreased sensitivity to pyrazoleamides (PA21A092); increased susceptibility to spiroindolones (cipargamin) [3] [20] | Alters drug binding pocket; may cause conformational changes affecting compound access [3] [20] | Selected under continuous pyrazoleamide pressure in vitro; confirmed via CRISPR-Cas9 [3] [20] |

| G358A | TM3, near Na+ binding site | Resistance to cipargamin and (+)-SJ733 [3] | Similar mechanism to G358S; steric hindrance of drug binding [3] | Found in recrudescent parasites from clinical trials [3] |

| A211T | TM2 | Resistance to pyrazoleamide GNF-Pf4492; increased cipargamin sensitivity [20] | Alters ion transport function; hypersensitizes to spiroindolones [20] | Selected in vitro under GNF-Pf4492 pressure for 70 days [20] |

Structural Basis of Resistance

Recent structural insights from a 3.7 Å cryoEM structure of PfATP4 have illuminated the molecular mechanisms underlying these resistance mutations [3] [12]. The G358S mutation is located on transmembrane helix 3 (TM3), immediately adjacent to the proposed Na+ coordination site within the transmembrane domain. The introduction of a serine sidechain at this position potentially blocks cipargamin binding by steric hindrance within the proposed drug binding pocket [3]. Similarly, the A211V mutation resides within TM2 near both the ion-binding site and the proposed cipargamin binding site, suggesting that the valine substitution may alter the conformation of the drug binding pocket in a way that interferes with pyrazoleamide binding while potentially creating a more favorable interaction surface for spiroindolones [3] [20]. This structural information provides a framework for understanding how distinct mutations confer differential resistance patterns across chemotypes.

Experimental Methodologies for Characterizing PfATP4 Mutations

Resistance Selection Protocols

In Vitro Evolution Experiments

To generate PfATP4-mutant parasites resistant to cipargamin, researchers have implemented sequential drug pressure protocols [18] [19]. Parasite cultures (typically Dd2 or 3D7 strains) are exposed to incrementally increasing concentrations of cipargamin over approximately four months, starting with sub-nanomolar concentrations (e.g., 0.5 nM) and gradually escalating to micromolar levels (up to 5 μM) as parasites adapt [18] [19]. Cultures are maintained with regular medium changes and drug replenishment, with parasite survival monitored via thin blood smears or SYBR Green fluorescence assays. Resistant populations are cloned by limiting dilution, and their genomes are sequenced to identify resistance-conferring mutations in pfatp4 [18].

CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing

For functional validation of specific mutations, CRISPR-Cas9 has been employed to introduce point mutations into endogenous pfatp4 [3] [20]. The protocol involves:

- Design of repair templates: Single-stranded oligonucleotides containing the desired mutation (e.g., A211V) with ~35 bp homology arms

- sgRNA construction: Guide RNAs targeting sequences near the mutation site

- Transfection: Delivery of Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes and repair templates to infected erythrocytes via electroporation

- Selection: Drug selection (e.g., with WR99210 if using hDHFR selectable marker) and clone isolation

- Genotype confirmation: Sanger sequencing of the modified pfatp4 locus [3] [20]

Phenotypic Characterization Assays

Drug Sensitivity Profiling

The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of PfATP4 inhibitors against mutant parasites is determined using standardized growth inhibition assays [20] [18]. Synchronized ring-stage parasites are cultured in 96-well plates at 1% parasitemia and 3% hematocrit with serial dilutions of compounds (typically spanning 0.1 nM to 1 μM). After 48 hours of exposure, parasite growth is quantified via 3H-hypoxanthine incorporation or SYBR Green I fluorescence using flow cytometry. Dose-response curves are fitted using non-linear regression to calculate IC50 values [20].

Intracellular Sodium Measurement

Resting cytosolic [Na+] in mutant parasites is measured using the Na+ indicator dye Sodium Green Tetraacetate [18] [19]. Synchronized trophozoite-stage parasites are isolated by saponin lysis of erythrocytes, loaded with 10 μM Sodium Green AM ester for 60 minutes at 37°C, washed, and resuspended in Na+-free medium. Fluorescence is measured using a fluorescence microplate reader (excitation 490 nm, emission 535 nm). Calibration is performed using the ionophores gramicidin and monensin in buffers with known Na+ concentrations to convert fluorescence values to [Na+] [18].

Figure 1: Workflow for Drug Sensitivity Profiling of PfATP4 Mutations

Resistance Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Molecular Mechanisms of PfATP4 Inhibition and Resistance

The molecular mechanisms of PfATP4 inhibition and subsequent resistance development involve complex interactions at the drug binding site and alterations in ion transport function. The recently solved cryoEM structure of PfATP4 reveals that the protein contains five canonical P-type ATPase domains: transmembrane domain (TMD), nucleotide-binding (N) domain, phosphorylation (P) domain, actuator (A) domain, and extracellular loop (ECL) domain [3] [12]. The ion-binding site is located between TM4, TM5, TM6, and TM8, similar to other P2-type ATPases like SERCA [3]. PfATP4 inhibitors such as cipargamin and pyrazoleamides bind within the transmembrane domain, interfering with Na+ binding and transport. Resistance mutations primarily cluster around the Na+ binding site, with G358S on TM3 and A211V on TM2 both positioned to directly or allosterically influence drug binding [3].

The G358S mutation confers resistance through a dual mechanism: it directly impedes drug binding through steric hindrance while simultaneously reducing the pump's affinity for Na+ [18] [19]. This results in parasites with elevated resting cytosolic [Na+] that are less susceptible to further Na+ dysregulation by PfATP4 inhibitors. Interestingly, the A211V mutation exhibits a paradoxical resistance profile, conferring resistance to pyrazoleamides while hypersensitizing parasites to spiroindolones [3] [20]. This suggests that rather than generally compromising drug binding, this mutation induces specific conformational changes that differentially affect how distinct chemotypes interact with the binding pocket.

Figure 2: Mechanism of PfATP4 Inhibition and Resistance Development

Metabolic Adaptation Pathways

Beyond direct target mutations, parasites exhibit metabolic adaptations to PfATP4 inhibition. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses of A211V mutant parasites under sublethal drug pressure reveal significant alterations in phospholipid signaling pathways [20]. Specifically, parasites treated with PA21A092 show increased enzymatic activities associated with phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylserine, and phosphatidylinositol synthesis, suggesting activation of protein kinases via phospholipid-dependent signaling as a compensatory mechanism to ionic perturbation [20]. This metabolic adaptation represents a separate resistance mechanism that could be targeted to prevent emergence of resistance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for PfATP4 Mutation Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Specific Example | Research Application | Key Features/Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engineered Parasite Lines | Dd2A211V (CRISPR-edited) [20] | Resistance mechanism studies; cross-resistance profiling | Confirmed A211V mutation; hypersensitive to cipargamin; resistant to pyrazoleamides |

| PfATP4 Inhibitors | Cipargamin (KAE609) [18] [19] | Positive control for assays; resistance selection | Spiroindolone; clinical candidate; IC50 ~0.4-1.1 nM against wild-type |

| PfATP4 Inhibitors | PA21A092 [3] [20] | Pyrazoleamide representative; cross-resistance studies | Pyrazoleamide; selects for A211V/T mutations |

| Fluorescent Indicators | Sodium Green Tetraacetate [18] [19] | Cytosolic Na+ measurements | Cell-permeant AM ester; fluorescence increases with Na+ binding |

| Antimalarial Controls | Artemether-lumefantrine [18] [19] | Off-target resistance assessment; combination studies | Standard care ACT; no cross-resistance with PfATP4 mutations |

| Expression Systems | TgATP4 in T. gondii [18] [19] | Heterologous functional characterization | ATP4 homolog; functional conservation with PfATP4 |

Discussion and Clinical Implications

The cataloging of clinically relevant PfATP4 mutations reveals critical patterns with direct implications for antimalarial development. The emergence of the G358S mutation in clinical trials demonstrates the real-world potential for resistance development to even the most promising PfATP4 inhibitors [18] [19]. The differential resistance patterns observed with mutations like A211V – conferring resistance to one chemotype while hypersensitizing to another – suggest opportunities for strategic combination therapies that could suppress resistance emergence [3] [20]. Furthermore, the discovery of an apicomplexan-specific PfATP4-binding protein (PfABP) in the recent cryoEM structure presents a novel avenue for inhibitor design that might circumvent existing resistance mechanisms [3] [12].

The structural biology advances represented by the 3.7 Å PfATP4 cryoEM structure now enable structure-guided drug design to develop next-generation inhibitors less susceptible to existing resistance mechanisms [3] [12]. Additionally, the metabolic adaptations observed in resistant parasites highlight the potential for targeting compensatory pathways to preserve the efficacy of PfATP4-directed compounds. As resistance to current artemisinin-based combinations spreads in Africa [21], the validation of PfATP4 mutations and their functional characterization provides critical insights for developing new antimalarial strategies with improved resistance profiles.

Building the Yeast Model: From Vector Design to Functional Expression

Strategic Selection of Yeast Expression Systems and Promoters

The rising spread of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum parasites underscores a pressing need for novel antimalarial drugs with new mechanisms of action [8]. Target-based screening in heterologous expression systems offers a powerful strategy for early drug discovery. The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has emerged as a preferred chassis for functional expression and validation of Plasmodium membrane proteins and essential enzymes, bridging the gap between target identification and compound screening in parasites [8] [22] [23].

This guide objectively compares yeast expression systems and promoter strategies, focusing on their application in validating the antimalarial target PfATP4 and other targets like PfPiT. We present comparative performance data and detailed methodologies to inform selection for malaria drug discovery projects.

Comparison of Yeast Expression Systems for Malaria Target Validation

The table below summarizes three distinct yeast-based expression platforms developed for the functional study and inhibition screening of different Plasmodium targets.

Table 1: Comparison of Yeast-Based Platforms for Malaria Target Validation

| Malaria Target | Target Function & Rationale | Yeast Genetic Engineering | Key Assay Readout | Performance & Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PfPiT [8] [24] | Sodium-coupled inorganic phosphate (Pi) transporter; essential for parasite proliferation. | Replacement of endogenous yeast Pi transporter (PHO84) with a yeast-codon-optimized PfPiT gene. |

|

|

| PfCHA [22] | Ca²⁺/H⁺ antiporter; fundamental for Ca²⁺ signalling in parasite life cycle. | Expression of PfCHA in a yeast strain lacking the vacuolar Ca²⁺/H⁺ exchanger (vcx1Δ). |

|

|

| PvDHS [23] | Deoxyhypusine synthase; essential for post-translational modification of eIF5A. | Replacement of the endogenous yeast DYS1 gene with genes for P. vivax DHS (PvDHS) or human DHS (HsDHS). |

|

|

The following workflow generalizes the process of developing and using such a yeast-based screening platform:

Promoter Engineering Strategies for Controlled Gene Expression

Precise control of target gene expression is critical. Synthetic biology provides tools to engineer promoters with specific strengths and regulatory properties.

Table 2: Comparison of Yeast Promoter Engineering Strategies

| Engineering Strategy | Key Methodology | Induction/Strength Profile | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid Promoters [25] | Fusion of Upstream Activating Sequences (UAS) from one promoter to the core promoter of another. | Dynamic range up to 50-fold for galactose-inducible systems. | Tuning expression levels of toxic proteins or pathway enzymes. |

| Minimal Leaky Promoters [26] | Direct fusion of bacterial operators upstream of TATA-box, plus >1-kbp insulator sequences. | >10³-fold induction with minimal leakiness. | High-throughput screening where background growth is undesirable. |

| Constitutive Promoters [25] | Use of strong, unregulated native promoters (e.g., pGPD, pTEF1). | Constant high-level expression. | Complementation assays or expressing selection markers. |

The diagram below illustrates the design principle for constructing a high-performance, minimal-leak synthetic promoter.

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Assays

This protocol outlines the key steps for a growth inhibition screen against a phosphate transporter target.

Strain and Media Preparation:

- Use the engineered S. cerevisiae strain where PfPiT is the sole phosphate transporter.

- Culture yeast in synthetic complete media with 25 mM phosphate (SC+25Pi) prior to the assay.

- For the assay, use 2x synthetic complete media with 24 mM phosphate (2xSC+24Pi).

Growth Inhibition Assay:

- Dilute overnight cultures to a standardized optical density (OD600).

- Dispense cells into a 96-well plate containing the test compounds.

- Incubate the plate with continuous shaking for 22 hours at 30°C.

- Monitor growth by measuring OD600 at regular intervals.

Counter-Screen and Validation:

- Counter-screen all compounds against the parental yeast strain (expressing the native transporter Pho84) to identify off-target effects.

- Confirm hits using a radioactive [³²P]phosphate uptake assay to directly measure inhibition of phosphate transport.

This protocol measures the function of ion transporters in real-time.

Strain Transformation and Culture:

- Co-transform yeast with the plasmid expressing the malaria target (e.g., PfCHA) and a plasmid expressing the calcium-sensitive protein apoaequorin.

- Grow transformed cells in selective media with glucose to exponential phase.

Gene Expression and Apoaequorin Reconstitution:

- Wash cells and transfer to media with galactose for 4 hours to induce target gene expression.

- Harvest cells and resuspend in test medium.

- Incubate cells with coelenterazine (the apoaequorin cofactor) for 30 minutes in the dark to form functional aequorin.

Cation Challenge and Luminescence Measurement:

- Transfer the cell suspension to a luminometer.

- Inject a pulse of the cation of interest (e.g., Ca²⁺, Mn²⁺, Mg²⁺).

- Monitor the resulting burst of luminescence, which is inversely proportional to the transporter's ability to clear the cation from the cytoplasm.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Yeast-Based Malaria Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experimental Workflow | Specific Examples from Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | For precise endogenous tagging or gene knockout in yeast and Plasmodium. | Endogenous C-terminal 3xFLAG tagging of PfATP4 in P. falciparum [3]. |

| Codon-Optimized Genes | Enhances functional expression of Plasmodium genes in the heterologous yeast host. | A S. cerevisiae codon-optimized version of the PfPiT gene was synthesized [8]. |

| Reporter Assays | Provides a quantitative readout for target activity or cellular stress. | Apoaequorin for cytosolic Ca²⁺ [22]; GFP for promoter activity [26]; Western blot for eIF5A hypusination [23]. |

| Specialized Media | Creates selective pressure or defined conditions for functional assays. | Phosphate-limited media for PfPiT screens [8]; Galactose media for inducible expression [22]. |

Yeast expression systems provide a versatile and powerful platform for validating novel antimalarial targets like PfATP4 and PfPiT. The strategic selection of a chassis depends on the target type: essential enzymes like PvDHS require clean gene replacement backgrounds [23], while ion transporters like PfPiT and PfCHA necessitate the knockout of specific endogenous transporters and specialized functional assays [8] [22].

The choice of promoter is equally critical. For initial functional expression and complementation, strong constitutive promoters are effective. For high-throughput compound screening where background growth can lead to false negatives, modern synthetic promoters with high induction ratios and minimal leakiness are superior [26]. By matching the engineered yeast system and expression strategy to the biological and chemical questions at hand, researchers can de-risk early antimalarial drug discovery and accelerate the identification of novel inhibitory compounds.

The ongoing battle against malaria, a disease causing hundreds of thousands of deaths annually, is increasingly threatened by the spread of parasite resistance to first-line treatments like artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) [8]. This urgent need has accelerated research into novel antimalarial drug targets, particularly essential parasite membrane transport proteins. Among these, the Plasmodium falciparum sodium efflux pump PfATP4 has emerged as a promising target for multiple new compound classes [4]. However, a significant challenge in validating and targeting PfATP4 has been the historical difficulty of expressing this protein in heterologous systems [3] [12]. This guide explores and compares a groundbreaking solution to this problem: the co-expression of PfATP4 with its newly discovered binding partner, PfABP. We frame this innovative co-expression strategy within the established context of yeast-based antimalarial target validation, a approach that has proven successful for other essential parasite transporters such as PfPiT [8].

PfATP4 as a High-Value Antimalarial Target

PfATP4 is a P-type ATPase cation pump located on the plasma membrane of the Plasmodium falciparum parasite. Its primary physiological role is to maintain low intracellular sodium concentration ([Na+] ~10 mM) by actively extruding Na+ against a steep gradient, a process crucial for parasite survival within host red blood cells where sodium levels are much higher (~135 mM) [3] [10]. Chemically distinct compound classes, including spiroindolones (e.g., Cipargamin) and pyrazoleamides, have converged upon PfATP4 as their target [4]. Inhibition of PfATP4 leads to a rapid disruption of cytosolic Na+ homeostasis, resulting in a cascade of lethal events for the parasite: cellular swelling, changes in membrane lipid composition, and induction of premature schizogony [11]. The clinical potential of this target is underscored by Cipargamin's successful progression through Phase II clinical trials, demonstrating potent and rapid clearance of parasites [4] [11].

The Power of Yeast-Based Validation

Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) expression systems provide a powerful platform for validating essential parasite genes as drug targets. The approach is based on a simple yet robust principle: if an essential parasite protein can functionally replace its non-essential yeast homolog, then yeast growth becomes dependent on the parasite protein's function. This system can then be used to screen for compounds that specifically inhibit the parasite protein, thereby halting yeast growth.

A proven precedent for this strategy exists with PfPiT, the parasite's single sodium-coupled inorganic phosphate transporter. Researchers created a yeast strain where all five endogenous phosphate transporters were knocked out and replaced with PfPiT as the sole phosphate transporter [8]. In this system, yeast growth became strictly dependent on PfPiT-mediated phosphate uptake. This engineered strain enabled the development of a 22-hour growth assay to screen for PfPiT inhibitors, successfully identifying two specific inhibitors from a small compound library [8]. This successful application provides a strong methodological foundation for applying similar strategies to other targets, including PfATP4.

Table: Successful Yeast-Based Assay for a Malaria Transporter

| Aspect | Description for PfPiT Assay [8] |

|---|---|

| Target | PfPiT (Plasmodium phosphate transporter) |

| Yeast Engineering | Knockout of 5 endogenous phosphate transporters; expression of PfPiT as sole transporter |

| Validated Function | Sodium-coupled phosphate uptake (Km = 24-56 µM) |

| Assay Readout | 22-hour growth assay |

| Screening Outcome | 2 specific inhibitors identified from 21 compounds |

| Key Advantage | Simple, inexpensive, high-throughput capable |

A Paradigm Shift: The Discovery of PfABP

Overcoming the PfATP4 Expression Barrier

A major obstacle in PfATP4 research had been the consistent failure to express functional PfATP4 in heterologous systems, which prevented high-resolution structural studies and detailed functional characterization [3] [12]. A groundbreaking advancement came in late 2024 and 2025, when researchers determined the first cryoEM structure of PfATP4 at 3.7 Å resolution by purifying the protein directly from CRISPR-engineered P. falciparum parasites cultured in human red blood cells [3] [10] [12].

This structural breakthrough led to a critical discovery: an additional helix interacting with transmembrane helix 9 (TM9) of PfATP4 that did not belong to the pump itself. This helix was identified as the C-terminus of a previously uncharacterized protein, PF3D7_1315500, now named PfATP4-Binding Protein (PfABP) [3] [12]. This discovery was only possible because the complex was isolated from its native environment, highlighting a significant limitation of previous heterologous expression attempts.

The Essential Role of PfABP

PfABP forms a conserved, apicomplexan-specific interaction with PfATP4 and appears to play a crucial modulatory role. Key findings establish its importance:

- Stabilization: Loss of PfABP leads to the rapid degradation of PfATP4, indicating PfABP is essential for maintaining PfATP4 stability [10].

- Essentiality: PfABP is itself essential for parasite survival [3] [10].

- Conservation: PfABP is highly conserved across malaria parasites but is absent in humans, making the PfATP4-PfABP interface a unique therapeutic opportunity with potentially reduced risk of off-target effects in humans [10].

- Regulation: The interaction suggests PfABP likely modulates PfATP4's ATPase activity and sodium transport function, similar to how regulatory subunits control human ion pumps [10].

The discovery of PfABP fundamentally changes the perspective on PfATP4, indicating it does not function in isolation but as part of a protein complex. This presents a new vulnerability that can be exploited for drug development.

Co-expression Strategy: PfATP4 with PfABP

Conceptual Workflow and Rationale

The historical difficulties in expressing PfATP4 alone, combined with the new knowledge of its essential partnership with PfABP, strongly suggest that a co-expression strategy is necessary for functional studies. Attempting to express PfATP4 in heterologous systems like yeast without its binding partner likely fails because the parasite pump requires PfABP for proper folding, stability, or regulation. Co-expression aims to replicate the native biological context found in the malaria parasite, providing the necessary cellular environment for PfATP4 to function as it does in vivo.

Comparative Analysis: PfPiT vs. PfATP4 Co-expression

The successful yeast model for PfPiT provides a benchmark against which a potential PfATP4-PfABP co-expression system can be evaluated. The table below contrasts the two approaches, highlighting both the established methodology and the novel requirements for the PfATP4-PfABP complex.

Table: Comparison of Yeast-Based Engineering Strategies for Two Malaria Transporters

| Engineering & Functional Aspect | PfPiT Strategy (Validated) [8] | PfATP4-PfABP Strategy (Proposed) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identity | Phosphate transporter (PfPiT) | Sodium pump (PfATP4) with binding partner (PfABP) |

| Yeast Host Engineering | Knockout of 5 endogenous phosphate transporters (Δpho84, etc.) | Likely knockout of ENA ATPases or other cation transporters |

| Parasite Gene Expression | Single gene (PfPiT) integrated as sole phosphate transporter | Two genes (PfATP4 + PfABP) requiring coordinated expression |

| Molecular Function | Sodium-coupled phosphate uptake | Sodium efflux, ATP-dependent |

| Critical Cofactors/Partners | Sodium ions | Sodium ions, ATP, PfABP binding partner |

| Validated Inhibitors | Yes (2 identified from small screen) | Multiple (Cipargamin, PA21A092) but resistance exists |

| Key Challenge | Creating phosphate auxotrophy | Achieving stable PfATP4 expression via PfABP co-expression |

Experimental Design & Protocols

Proposed Protocol for Yeast Co-expression

Building upon the validated PfPiT protocol [8] and incorporating insights from the native PfATP4 purification [3] [12], the following detailed protocol is proposed for establishing a yeast co-expression model.

Step 1: Yeast Strain Engineering

- Parent Strain: Select an appropriate background strain (e.g., EY918, used for PfPiT, which has auxotrophic markers and defined transporter knockouts) [8].

- Gene Knockout: Use CRISPR-Cas9 to delete non-essential yeast cation exporters (e.g., ENA ATPases) to create a sodium-sensitive background, making yeast growth dependent on functional PfATP4.

- Plasmid Construction: Clone a yeast codon-optimized version of the PfATP4 gene and the PfABP gene into expression vectors with strong, inducible yeast promoters (e.g., GAL1/GAL10). A polycistronic vector or two compatible plasmids with different selection markers are viable options.

- Transformation: Co-transform the PfATP4 and PfABP constructs into the engineered yeast strain and select on appropriate dropout media.

Step 2: Functional Validation Assays

- Growth Assay: Test transformants on media with high sodium (~135 mM, mimicking blood plasma [3]) and low sodium conditions. Growth in high sodium should be dependent on the expression of both PfATP4 and PfABP.

- Biochemical Assay: Measure Na+-dependent ATPase activity in yeast membranes, comparing strains expressing PfATP4 alone versus PfATP4+PfABP. The assay should demonstrate ATP hydrolysis that is inhibited by known PfATP4 inhibitors like Cipargamin [3] [12].

- Localization:

Step 3: High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Ready Assay

- Optimization: Determine the optimal pH, incubation time (a 22-hour assay was successful for PfPiT [8]), and cell density for a robust growth-based HTS assay.

- Validation: Test known PfATP4 inhibitors (Cipargamin, PA21A092) to confirm they inhibit the growth of the co-expression strain but not control strains.

- Screening: Implement the assay in a 384-well format to screen large compound libraries for novel inhibitors that disrupt PfATP4 function or the PfATP4-PfABP interaction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and their critical functions, derived from both the established PfPiT protocol and the novel PfATP4-PfABP research, that are essential for implementing this co-expression strategy.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for PfATP4-PfABP Co-expression Studies

| Research Reagent | Function & Application | Experimental Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Engineering yeast host strain by knocking out endogenous cation transporters. | Used for C-terminal tagging of PfATP4 in parasites [3] [12]. |

| S. cerevisiae Strain EY918 | Parental yeast strain with auxotrophic markers; background for creating transporter knockouts. | Used as parent strain for PfPiT expression [8]. |

| Codon-Optimized PfATP4/PfABP Genes | Ensures high expression levels of parasite proteins in the yeast heterologous system. | A yeast codon-optimized PfPiT gene was successfully synthesized and expressed [8]. |

| Synthetic Complete Media (SC) | Defined media for culturing engineered yeast strains; allows control of sodium/phosphate levels. | SC+25Pi media used for PfPiT yeast culture and assays [8]. |

| Cipargamin (KAE609) | Known PfATP4 inhibitor; critical control compound for validating the functional output of the assay. | Inhibits Na+-dependent ATPase activity of native PfATP4 [3] [4] [12]. |

| Epitope Tags (3×FLAG, HA) | For protein detection, localization (immunofluorescence), and interaction studies (co-IP). | 3×FLAG tag used for endogenous purification of PfATP4 [3] [12]. |

| Antibodies for Detection | To verify protein expression and co-localization of PfATP4 and PfABP in yeast. | Mass spectrometry confirmed PfABP identity in native complex [3]. |

The discovery of PfABP as an essential stabilizing partner for PfATP4 represents a paradigm shift in antimalarial drug discovery. It provides a clear explanation for past failures in heterologous expression and outlines a clear path forward: the co-expression of this protein complex. Implementing this strategy within a yeast model, following the blueprint successfully established for PfPiT, offers a promising and cost-effective platform to validate this crucial target. This system would not only enable the screening of direct PfATP4 inhibitors but also open the door to discovering first-in-class compounds that disrupt the PfATP4-PfABP interaction. By targeting this apicomplexan-specific partnership, researchers can aim to develop novel antimalarials that are less susceptible to existing resistance mechanisms and offer a higher therapeutic index, potentially overcoming one of the most significant challenges in modern malaria control.

The validation of PfATP4, a sodium efflux pump located on the Plasmodium falciparum plasma membrane, as a promising antimalarial target represents a significant advance in parasitology [1]. However, its functional study in heterologous systems, such as yeast, presents substantial challenges due to the complex native membrane environment essential for its stability and activity [3]. Recent structural studies reveal that PfATP4's native state within the parasite involves a specific lipid milieu and a critical, previously unknown binding partner, the PfATP4-Binding Protein (PfABP) [3] [10] [7]. This guide objectively compares different experimental approaches for studying PfATP4, emphasizing the importance of mimicking its native membrane and chaperone interactions to generate physiologically relevant data for drug discovery.

Comparative Analysis of PfATP4 Expression Systems

The table below compares the key characteristics of heterologous expression systems with the native parasite system for PfATP4 study.

Table 1: Comparison of Systems for Studying PfATP4 Function and Inhibition

| Experimental System | Key Features & Components | Advantages | Limitations | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Expression (e.g., Yeast, Xenopus oocytes) | Requires only PfATP4 gene; lacks native P. falciparum lipids and PfABP [3] [1]. | Potentially higher protein yield; scalable for initial screening [27]. | Historically unsuccessful for PfATP4 structural studies; lacks regulatory subunits; may not reflect true conformation or drug sensitivity [3] [7]. | Initial inference of Ca2+-dependent ATPase activity (later disputed) [1]. |

| Native Parasite Expression (Endogenous Purification) | Full complement of native lipids; presence of the essential modulator PfABP [3] [10]. | Reveals physiologically accurate structure and authentic protein-protein interactions [3] [7]. | Technically challenging; requires culture of parasites in human RBCs; lower protein yield [10]. | Discovery of PfABP; high-resolution structure (3.7 Å); mapping of resistance mutations; identification of true Na+-bound state [3]. |

The Critical Role of PfABP as a Native Chaperone

A pivotal finding from endogenous studies is the discovery of PfATP4-Binding Protein (PfABP), an apicomplexan-specific protein that forms a conserved, modulatory interaction with PfATP4 [3]. This interaction was entirely missed in previous heterologous expression attempts.

- Stabilizing Function: PfABP acts as a essential chaperone, binding tightly to TM9 of PfATP4's transmembrane domain. Loss of PfABP leads to the rapid degradation of PfATP4 and parasite death, confirming its crucial role in maintaining the pump's stability [10] [7].

- Modulatory Role: PfABP is hypothesized to regulate PfATP4's activity, functioning similarly to regulatory subunits found in human ion pumps. This presents a novel, unexplored avenue for drug design [10].

- Target Advantage: As PfABP is conserved across malaria parasites but absent in humans, targeting the PfATP4-PfABP interface offers potential for high selectivity and a lower risk of side effects in future therapeutics [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Endogenous PfATP4 Purification and Structural Analysis fromP. falciparum

This protocol, derived from recent cryo-EM studies, is critical for capturing the native state of PfATP4 [3].

- Parasite Culture and Engineering: Culture P. falciparum Dd2 strain parasites in human red blood cells. Use CRISPR-Cas9 to insert a 3×FLAG epitope tag at the C-terminus of the endogenous pfatp4 gene.

- Membrane Protein Extraction: Harvest infected red blood cells. Solubilize parasite membranes using a suitable detergent to extract PfATP4 in its native complex.

- Affinity Purification: Use anti-FLAG affinity resin to isolate the PfATP4 complex from the solubilized membrane extract.

- Functional Validation: Confirm biological activity of the purified protein via a Na+-dependent ATPase activity assay. Validate target engagement by demonstrating inhibition of this activity with known PfATP4 inhibitors like Cipargamin and PA21A092 [3].

- Cryo-EM Structure Determination:

- Prepare the purified sample on cryo-EM grids and vitrify.

- Collect single-particle cryo-EM data.

- Perform 3D reconstruction to achieve a high-resolution structure (3.7 Å).

- Build an atomic model, identifying and modeling unassigned densities, such as the helix corresponding to PfABP [3].

Protocol B: Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Assay for PfATP4-PfABP Interaction Mapping

The Y2H system is ideal for validating and characterizing the binary interaction between PfATP4 and PfABP in a eukaryotic in vivo environment [27].

- Strain and Plasmid Preparation:

- Use AH109 or Y187 yeast reporter strains.

- Clone the gene for PfATP4 (as "Bait") into a vector fused to the Gal4 DNA-Binding Domain (BD).

- Clone the gene for PfABP (as "Prey") into a vector fused to the Gal4 Activation Domain (AD) [27].

- Co-transformation and Selection:

- Co-transform both plasmids into the yeast reporter strain.

- Plate the transformed yeast on synthetic dropout (SD) media lacking leucine and tryptophan (-Leu/-Trp) to select for cells containing both plasmids [27].

- Interaction Testing: