Validating Chemogenomic Hit Genes: Strategies for Target Confirmation in Drug Discovery

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of validating chemogenomic hit genes in modern drug discovery.

Validating Chemogenomic Hit Genes: Strategies for Target Confirmation in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of validating chemogenomic hit genes in modern drug discovery. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of chemogenomic screening, detailing both forward and reverse approaches for identifying potential drug targets. The article systematically examines experimental and computational validation methodologies, tackles common troubleshooting scenarios, and provides frameworks for comparative analysis across studies and model systems. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging technologies, this resource aims to equip scientists with robust strategies for transforming preliminary chemogenomic hits into confidently validated therapeutic targets, ultimately accelerating the development of novel treatments for human diseases.

Chemogenomics Fundamentals: From Screening Hits to Biological Insights

Defining Chemogenomic Hit Validation in Modern Drug Discovery

In the post-genomic era, chemogenomics—the systematic discovery of all possible drugs for all possible drug targets—has emerged as a powerful paradigm for accelerating pharmaceutical research [1]. This approach leverages the wealth of genomic information to screen chemical compounds against biological targets on an unprecedented scale. However, the initial identification of a compound-target interaction, or a "hit," is merely the starting point. The subsequent process of hit validation is crucial for distinguishing true therapeutic potential from spurious results, thereby ensuring the efficient allocation of resources in the drug discovery pipeline.

Hit validation in chemogenomics confirms that a observed interaction is real, biologically relevant, and has the potential to be developed into a therapeutic agent. It moves beyond simple binding confirmation to interrogate the functional consequences of target engagement within a complex biological system. As drug discovery increasingly integrates high-throughput screening, functional genomics, and artificial intelligence, the strategies for validating chemogenomic hits have evolved into a sophisticated, multi-faceted discipline. This guide objectively compares the performance of predominant validation methodologies, providing researchers with a framework to select the optimal approach for their specific project needs.

Core Principles and Definitions of Chemogenomic Hit Validation

A chemogenomic "hit" is typically defined as a small molecule that demonstrates a desired interaction with a target protein or phenotypic readout in a primary screen. The core objective of validation is to build a compelling case that this initial observation is both reproducible and physiologically meaningful. This process is governed by several key principles:

- Target Engagement: Demonstrating direct and specific binding between the compound and its intended protein target in a physiological context [2].

- Functional Modulation: Establishing that the binding event leads to a predictable and measurable change in the target's biological activity or pathway.

- Selectivity and Specificity: Confirming that the compound's activity is not due to off-target effects on unrelated proteins or pathways. For a high-quality chemical probe, this often means demonstrating >30-fold selectivity over closely related targets [2].

- Cellular Activity: Verifying that the compound produces the intended effect in live cells at a non-cytotoxic concentration, typically <1 μM [2].

The validation strategy must also account for the two primary screening approaches in modern discovery: target-based screening, which starts with a known protein, and phenotypic screening, which begins with a desired cellular or organismal outcome without a pre-specified molecular target [3].

Comparative Analysis of Major Validation Methodologies

This section provides a objective comparison of the primary experimental frameworks used for chemogenomic hit validation. The choice among these depends on the project's goals, available tools, and the desired level of mechanistic understanding.

Computational & AI-Driven Prediction

Computational methods are increasingly the first step in validating and prioritizing hits from large-scale screens. These approaches use machine learning and pattern recognition to predict a compound's mechanism of action (MOA) by integrating diverse datasets.

- Core Protocol: Tools like DeepTarget exemplify this approach. The methodology involves: 1) collecting large-scale drug viability screens (e.g., from DepMap) and genome-wide CRISPR knockout viability profiles from matched cell lines; 2) computing a Drug-Knockout Similarity (DKS) score, which quantifies the correlation between a drug's effect and the effect of knocking out a specific gene; and 3) integrating omics data (gene expression, mutation) to identify context-specific secondary targets and mutation-specific drug effects [4].

Performance Data:

- When benchmarked on eight gold-standard datasets of high-confidence cancer drug-target pairs, DeepTarget achieved a mean AUC of 0.73 for primary target identification, outperforming several structure-based prediction tools [4].

- It successfully clusters drugs by their known MOAs and has been prospectively validated in case studies, such as identifying pyrimethamine's effect on mitochondrial function [4].

Strengths: High scalability; ability to capture context-specific and polypharmacology effects; does not require a pre-defined protein structure.

- Limitations: Predictions are correlative and require experimental confirmation; performance is dependent on the quality and breadth of the underlying training data.

Phenotypic Screening & Profiling

This biology-first approach validates a hit based on its ability to induce a complex, disease-relevant phenotype. The subsequent challenge is to "deconvolute" the phenotype to identify the molecular target(s).

- Core Protocol: The workflow involves: 1) treating cells with the hit compound in a high-content screening setup, often using a Cell Painting assay to capture comprehensive morphological profiles; 2) extracting high-dimensional image-based features using software like CellProfiler or deep learning models; 3) comparing the compound's phenotypic profile to a reference database of profiles from compounds with known MOAs or genetic perturbations [3] [5].

Performance Data:

- Platforms like PhenAID can link morphological changes to known chemical and genetic perturbations, filtering out toxicity-driven signals to improve the biological relevance of selected hits [5].

- This integrated approach has successfully identified novel drug candidates, such as invasion inhibitors in lung cancer and antibacterial compounds, by backtracking from observed phenotypic shifts [3].

Strengths: Unbiased, disease-relevant starting point; captures complex systems-level biology and polypharmacology.

- Limitations: Target deconvolution can be challenging and time-consuming; may not clearly distinguish between primary and secondary effects.

Direct Biochemical & Biophysical Confirmation

This classical approach provides the most direct evidence of a compound interacting with its proposed target.

- Core Protocol: Key techniques include:

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): Measures the heat change during binding to determine affinity (KD) and stoichiometry.

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Monitors real-time binding kinetics (on-rate and off-rate) without labels.

- Crystallography/NMR: Provides atomic-resolution structures of the compound bound to its target, enabling structure-based optimization.

Performance Data:

- The development of the BET inhibitor (+)-JQ1 relied on ITC, demonstrating potent inhibition of BRD4 with a KD of 50 nM for its first bromodomain [2].

- These methods are considered the "gold standard" for confirming direct binding and assessing binding affinity and kinetics.

Strengths: Provides direct, quantitative evidence of binding; high informational value for medicinal chemistry.

- Limitations: Low-throughput; typically requires a purified protein target and may not reflect the cellular environment.

Functional Genetic Validation (CRISPR & RNAi)

This method uses genetic tools to modulate target expression or function, testing the hypothesis that the genetic and chemical perturbations will produce similar phenotypes.

- Core Protocol: The standard workflow is: 1) using CRISPR-Cas9 to knock out (KO) or RNA interference (RNAi) to knock down the putative target gene in a relevant cell model; 2) testing whether the hit compound loses its efficacy in the genetically modified cells compared to wild-type controls (a "rescue" experiment); 3) conversely, testing if genetic inhibition phenocopies the drug's effect [4].

Performance Data:

- The principle that CRISPR-KO of a drug's target should mimic the drug's effect forms the foundational hypothesis of the DeepTarget pipeline [4].

- This approach has been successfully applied to reveal the role of specific mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin-protein ligases in the efficacy of MCL1 inhibitors [4].

Strengths: Provides strong evidence for a target's role in the compound's mechanism of action; highly specific.

- Limitations: Can be confounded by genetic compensation or redundancy; does not directly prove physical binding.

Proteogenomic Integration

This emerging approach integrates mass spectrometry-based proteomics with genomic data to provide orthogonal, multi-layer evidence for hit validation.

- Core Protocol: The methodology involves: 1) analyzing cellular or tissue samples treated with the hit compound using high-resolution mass spectrometry (MS); 2) identifying and quantifying expressed proteins and post-translational modifications; 3) using a comparative proteogenomics approach across related species or conditions to distinguish true signals from artifacts, such as resolving "one-hit-wonders" in proteomics [6].

Performance Data:

- In a study of three Shewanella species, comparative proteogenomics provided supporting evidence for the expression of 329 proteins that would have been dismissed as "one-hit-wonders" based on single-species data alone [6].

- MS-based protein expression data can also be used to analyze conserved and differentially expressed pathways, adding functional context to a hit's activity [6].

Strengths: Provides direct evidence of protein expression and modification; can identify novel targets or mechanisms.

- Limitations: Technically complex and resource-intensive; requires sophisticated bioinformatics for data analysis.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Key Hit Validation Methodologies

| Methodology | Primary Readout | Key Performance Metrics | Typical Timeline | Resource Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational & AI-Driven | Predictive MOA & DKS Score | AUC (~0.73), Clustering Accuracy [4] | Days to Weeks | Low (post-data collection) |

| Phenotypic Profiling | High-Content Morphological Profile | Phenotypic Similarity Score, Hit Specificity [5] | Weeks | Medium to High |

| Biophysical Confirmation | Binding Affinity (KD), Kinetics | KD (e.g., <100 nM), Stoichiometry [2] | Days to Weeks | Medium |

| Functional Genetic | Genetic vs. Chemical Phenocopy | Loss-of-Effect in KO, Phenocopy Correlation [4] | Weeks to Months | Medium |

| Proteogenomic Integration | Protein Expression/Modification | Peptide/Protein Count, Spectral Evidence [6] | Weeks | High |

Table 2: Decision Matrix for Selecting a Validation Strategy

| Research Context | Recommended Primary Method | Recommended Orthogonal Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel Compound from HTS | Biophysical Confirmation (SPR, ITC) | Functional Genetic (CRISPR) | Confirms direct binding first, then establishes functional link to target. |

| Phenotypic Hit, Unknown Target | Phenotypic Profiling & AI | Proteogenomic Integration | Deconvolutes phenotype via profiling; MS provides physical evidence of engagement. |

| Repurposing Existing Drug | Computational & AI-Driven | Functional Genetic or Phenotypic | Efficiently predicts new MOAs; genetic tests provide inexpensive initial validation. |

| Optimizing a Chemical Probe | Biophysical Confirmation | Phenotypic Profiling | Ensures maintained potency and selectivity; confirms functional activity in cells. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Experiments

To ensure reproducibility, below are detailed protocols for two foundational validation experiments.

Protocol for DKS Score Calculation (AI-Driven Validation)

This protocol is adapted from the DeepTarget pipeline for primary target prediction [4].

- Data Acquisition: Obtain large-scale drug response profiles (e.g., viability curves) and Chronos-processed CRISPR-Cas9 knockout viability profiles for a matched panel of cancer cell lines from public repositories like DepMap.

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize both drug response and genetic dependency scores to account for screen-specific confounding factors (e.g., sgRNA efficacy, cell growth rates).

- Similarity Calculation: For each drug-gene pair, compute the Pearson correlation coefficient between the drug's response profile across the cell line panel and the profile of genetic dependency for that gene. This generates the raw DKS score.

- Regression Correction: Apply a linear regression model to the DKS scores to correct for residual technical biases and improve the specificity of the predictions.

- Target Prioritization: Rank genes based on their corrected DKS scores. A higher score indicates a stronger likelihood that the gene is a direct target of the drug.

Protocol for High-Content Phenotypic Hit Validation

This protocol outlines the steps for validating a hit using morphological profiling [3] [5].

- Cell Culture and Plating: Seed appropriate reporter cells (e.g., primary patient-derived cells if possible) into 384-well imaging plates at an optimized density.

- Compound Treatment: Treat cells with the hit compound across a range of concentrations (e.g., 1 nM - 10 µM), including appropriate controls: a negative control (DMSO vehicle) and positive controls (compounds with known, relevant MOAs).

- Staining and Fixation: At the desired endpoint (e.g., 24, 48, 72 hours), fix cells and stain with the Cell Painting assay dyes (e.g., labeling nuclei, cytoplasm, Golgi, actin, and mitochondria).

- Image Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution images using an automated high-content microscope with a minimum of 9 fields of view per well.

- Feature Extraction: Use image analysis software (e.g., CellProfiler) or a deep learning model to extract quantitative morphological features (e.g., cell size, shape, texture, intensity) for each cell.

- Profile Generation and Comparison: Average features across replicate wells to generate a stable morphological profile for the hit compound. Compare this profile to a reference database of profiles from known compounds using a similarity metric (e.g., Pearson correlation). A high similarity to a profile with a known MOA provides strong evidence for the hit's mechanism.

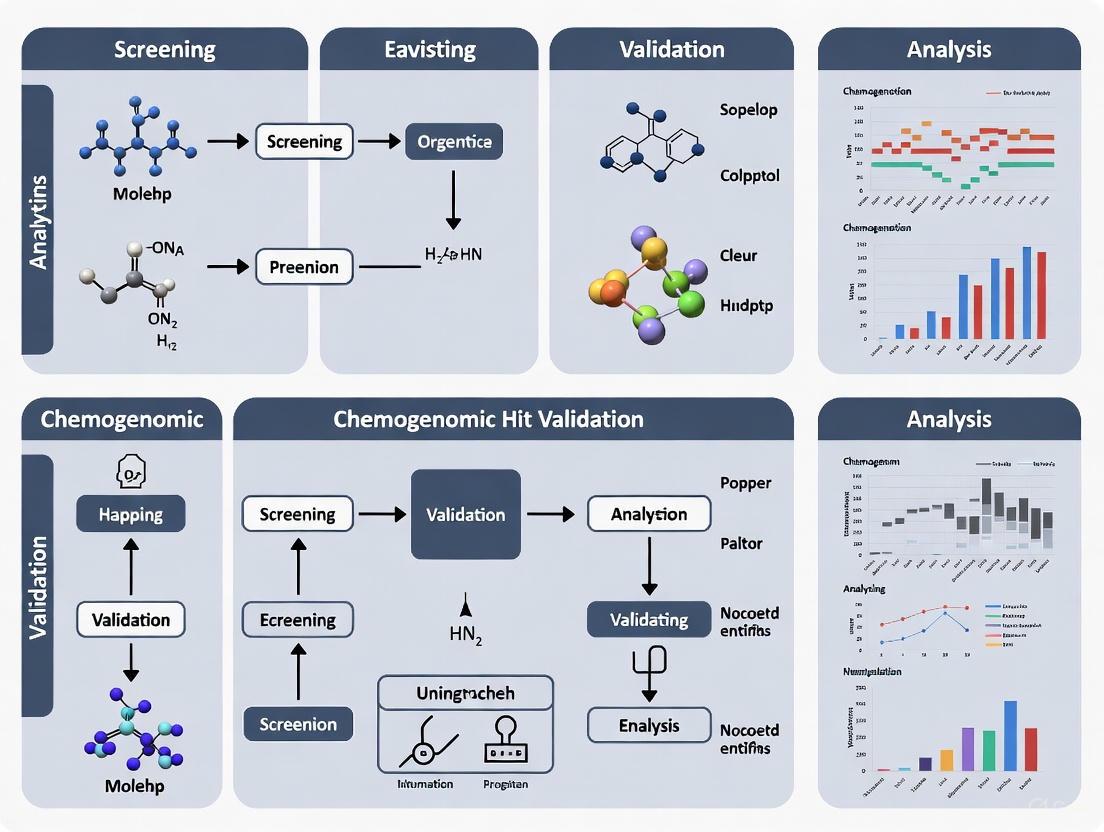

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow for hit validation and the relationship between different methodologies.

Diagram 1: A tiered workflow for hit validation, showing how computational prioritization feeds into orthogonal experimental validation.

Diagram 2: The interplay between computational and experimental validation methods, highlighting how AI guides specific experimental choices.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the described validation strategies requires a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The table below details key solutions for establishing a robust hit validation workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Hit Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Key Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Libraries | Targeted gene knockout | Functional genetic validation to test if target gene loss abrogates or mimics drug effect [4]. |

| Cell Painting Assay Kits | Multiplexed cellular staining | Generates high-dimensional morphological profiles for phenotypic validation and MoA prediction [3] [5]. |

| Validated Chemical Probes | Selective inhibition of specific targets | Used as positive controls in phenotypic and biochemical assays; defined by >30-fold selectivity and cellular activity <1µM [2]. |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Protein and peptide identification/quantification | Core technology for proteogenomic validation, identifying expressed proteins and post-translational modifications [6] [7]. |

| SPR/BLI Biosensors | Label-free analysis of biomolecular interactions | Provides direct, quantitative data on binding affinity (KD) and kinetics (kon, koff) for biophysical confirmation [2]. |

| Public Data Repositories (DepMap, ChEMBL) | Source of omics and drug response data | Provides essential datasets for computational validation and DKS score calculation [4] [8]. |

Hit validation is the critical gatekeeper in the chemogenomic drug discovery pipeline. No single methodology provides a complete picture; rather, a convergence of evidence from complementary approaches is required to confidently advance a compound. As this guide illustrates, the most robust validation strategies intelligently combine computational predictions with orthogonal experimental evidence from biophysical, phenotypic, genetic, and proteogenomic assays.

The future of chemogenomic hit validation lies in the deeper integration of these methodologies, powered by AI and ever-richer multi-omics datasets. By objectively comparing the performance, strengths, and limitations of each approach, researchers can design efficient, rigorous validation workflows that maximize the likelihood of translating a initial chemogenomic hit into a successful therapeutic candidate.

Chemogenomics represents a systematic approach in modern drug discovery that investigates the interaction between chemical libraries and families of biologically related protein targets [9]. This field operates on the fundamental principle that studying these interactions on a large scale enables the parallel identification of both novel therapeutic targets and bioactive compounds [9]. The completion of the human genome project has provided an abundance of potential targets for therapeutic intervention, and chemogenomics aims to systematically study the intersection of all possible drugs on these potential targets [9]. Within this framework, two distinct experimental paradigms have emerged: forward chemogenomics and reverse chemogenomics [9] [10]. These approaches differ primarily in their starting point and methodology, yet share the ultimate goal of linking small molecules to their biological targets and functions.

The core distinction between these strategies lies in their initial screening focus. Forward chemogenomics begins with the observation of a phenotypic outcome in a complex biological system, while reverse chemogenomics initiates with a specific, predefined protein target [11] [9]. This fundamental difference dictates all subsequent experimental design, technology requirements, and data interpretation methods. Both approaches have significantly contributed to hit gene validation in drug discovery, offering complementary pathways to establish meaningful connections between chemical structures and biological responses [9] [10].

Forward Chemogenomics: From Phenotype to Target

Conceptual Framework and Workflow

Forward chemogenomics, also termed "classical chemogenomics," represents a phenotype-first approach to target identification [9] [12]. This strategy begins with screening chemical compounds for their ability to induce a specific phenotypic response in cells or whole organisms, without prior knowledge of the molecular target involved [9] [13]. The fundamental premise is that small molecules which produce a desired phenotype can subsequently be used as tools to identify the protein responsible for that phenotype [9]. This approach is analogous to forward genetics, where a phenotype of interest is first identified, followed by determination of the gene or genes responsible [11].

The workflow typically initiates with establishing a cell-based assay that models a particular disease state or biological process [13]. A diverse library of compounds is then applied to this system, and the resulting phenotypic responses are measured [13]. Compounds that elicit the desired phenotype are selected as "hits" and subjected to follow-up studies to identify their protein targets [9] [13]. This methodology is considered unbiased because it does not require pre-selection of a specific molecular target, allowing for the discovery of novel druggable targets and biological pathways [13].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

A prominent example of forward chemogenomics in practice is the NCI60 screening program established by the National Cancer Institute [12]. This program screens compounds for anti-proliferative effects across a panel of 60 human cancer cell lines. The resulting cytotoxicity patterns create characteristic fingerprints that can be used to classify compounds and generate hypotheses about their mechanisms of action [12].

For target identification following phenotypic screening, several genetic approaches have been developed, particularly in model organisms like yeast where whole genome library collections are available [13]. Three primary gene-dosage based assays are commonly employed:

Haploinsufficiency Profiling (HIP): This assay utilizes heterozygous deletion mutants to identify drug targets based on the principle that decreased dosage of a drug target gene sensitizes cells to the compound [13]. When a strain shows increased growth inhibition upon drug treatment, it suggests the deleted gene may be the direct target or part of the same pathway [13].

Homozygous Profiling (HOP): Similar to HIP, HOP uses homozygous deletion collections but typically identifies genes that buffer the drug target pathway rather than direct targets [13].

Multicopy Suppression Profiling (MSP): This approach works on the opposite principle, where overexpression of a drug target gene confers resistance to drug-mediated growth inhibition [13]. Strains exhibiting growth advantage in the presence of the drug often directly identify the drug target [13].

These assays can be performed competitively in liquid culture using barcoded yeast strains, enabling genome-wide assessment of strain fitness in the presence of bioactive compounds [13].

Figure 1: Forward chemogenomics workflow begins with phenotypic screening and proceeds to target identification through multiple genetic and biochemical methods.

Applications and Case Studies

Forward chemogenomics has proven particularly valuable in cancer research, where the NCI60 screen has enabled classification of various anti-proliferative compounds and generated mechanistic hypotheses for novel cytotoxic agents [12]. The approach allows researchers to connect phenotypic patterns to potential mechanisms of action, facilitating the design of more targeted clinical trials and potentially leading to personalized chemotherapy approaches [12].

Another significant application lies in mode of action determination for traditional medicines [9]. For example, chemogenomics approaches have been used to study traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurveda, where compounds with known phenotypic effects but unknown mechanisms are investigated [9]. In one case study, the therapeutic class of "toning and replenishing medicine" was evaluated, and sodium-glucose transport proteins and PTP1B were identified as targets relevant to the hypoglycemic phenotype observed with these treatments [9].

Reverse Chemogenomics: From Target to Phenotype

Conceptual Framework and Workflow

Reverse chemogenomics adopts a target-first approach, beginning with a specific, predefined protein target and screening for compounds that modulate its activity [9] [10]. This methodology has been described as "reverse drug discovery" [14], where researchers start with a validated target of known relevance to a disease state and work to identify compounds that interact with it [13]. The process typically involves screening compound libraries in a high-throughput, target-based manner against specific proteins, followed by testing active compounds in cellular or organismal models to characterize the resulting phenotypes [9].

This approach benefits from prior target validation, where the relevance of a protein to a particular biological pathway, process, or disease has been established before screening begins [11]. The underlying assumption is that compounds which bind to or inhibit this validated target will produce the desired therapeutic effect [11]. Reverse chemogenomics essentially applies the principles of reverse genetics to chemical screening, where a specific gene/protein of interest is targeted first, followed by observation of the resulting phenotype when the target is modulated by small molecules [11].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

The reverse chemogenomics workflow typically begins with target selection and validation based on genomic, genetic, or biochemical evidence of its role in disease [11]. Once a target is selected, it is typically purified or expressed in a suitable system for high-throughput screening [11]. Screening assays can be divided into several categories:

Cell-free assays: These measure direct binding or inhibition of purified target proteins and are characterized by simplicity, precision, and compatibility with very high throughput approaches [12]. Universal binding assays allow clear identification of target-ligand interactions in the absence of confounding cellular variables [12].

Cell-based assays: These monitor effects on specific cellular pathways while maintaining some biological context [12].

Organism assays: These assess phenotypic outcomes in whole organisms but are typically lower throughput [12].

Following initial screening, hit compounds are validated and optimized before being tested in more complex biological systems to characterize the phenotypic consequences of target modulation [9]. This step confirms that interaction with the predefined target produces the expected biological effect [9].

Recent advances in reverse chemogenomics have been enhanced by parallel screening capabilities and the ability to perform lead optimization across multiple targets belonging to the same gene family [9]. This approach leverages structural and sequence similarities within protein families to identify compounds with selective or broad activity across multiple related targets [10].

Figure 2: Reverse chemogenomics workflow begins with target-based screening and proceeds to phenotypic characterization in progressively complex biological systems.

Applications and Case Studies

Reverse chemogenomics has proven particularly valuable for target families with well-characterized ligand-binding properties, such as G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), kinases, and ion channels [10]. For example, researchers have applied reverse chemogenomics to identify new antibacterial agents targeting the peptidoglycan synthesis pathway [9]. In this study, an existing ligand library for the enzyme murD was mapped to other members of the mur ligase family (murC, murE, murF, murA, and murG) to identify new targets for known ligands [9]. Structural and molecular docking studies revealed candidate ligands for murC and murE ligases, demonstrating how reverse chemogenomics can expand the utility of existing compound libraries [9].

The approach has also advanced through computational methods like proteochemometrics, which uses machine learning to predict protein-ligand interactions across all chemical spaces [10]. Deep learning approaches, including chemogenomic neural networks (CNNs), take input from molecular graphs and protein sequence encoders to learn representations of molecule-protein interactions [10]. These models are particularly valuable for predicting unexpected "off-targets" for existing drugs and guiding experiments to examine interactions with high probability scores [10].

Comparative Analysis of Forward and Reverse Chemogenomics

Direct Comparison of Key Parameters

Table 1: Systematic comparison of forward versus reverse chemogenomics approaches

| Parameter | Forward Chemogenomics | Reverse Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Phenotypic screen in cells or organisms [9] | Predefined, validated protein target [11] [9] |

| Screening Context | Complex cellular environment [13] | Reduced system (purified protein or cellular pathway) [12] |

| Target Identification | Post-screening, often challenging [9] | Predefined before screening [11] |

| Typical Assays | Phenotypic response measurement [13], HIP/HOP/MSP [13] | Target-binding assays, enzymatic inhibition [12] |

| Advantages | Unbiased discovery [13], biological relevance [11], identifies novel targets [9] | Straightforward optimization [11], high throughput capability [12] |

| Limitations | Target deconvolution challenging [9], lower throughput [11] | Limited to known biology [11], poor translation to in vivo efficacy [13] |

| Target Validation | Occurs after phenotypic observation [9] | Required before screening initiation [11] |

| Information Yield | Novel biological pathways [11], polypharmacology [11] | Selective compounds, structure-activity relationships [11] |

Practical Implementation Considerations

The choice between forward and reverse chemogenomics depends heavily on the research objectives, available tools, and stage of discovery. Forward approaches are particularly valuable when investigating poorly understood biological processes or when seeking entirely novel mechanisms of action [11] [13]. The maintenance of biological context throughout the initial screening phase provides more physiologically relevant information but comes with the challenge of subsequent target deconvolution [9].

Reverse approaches offer more straightforward medicinal chemistry optimization pathways since the molecular target is known from the outset [11]. This enables structure-based drug design and detailed structure-activity relationship studies [11]. However, this approach relies heavily on prior biological knowledge and may miss important off-target effects or polypharmacology that could be either beneficial or detrimental [11].

In practice, many successful drug discovery programs integrate elements of both approaches [11]. For instance, a reverse chemogenomics approach might identify initial hits against a validated target, while forward approaches in cellular or animal models could reveal unexpected biological effects or off-target activities that inform further optimization [11].

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for chemogenomics studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Libraries | Diverse small molecules for screening | GSK Biologically Diverse Set, LOPAC1280, Pfizer Chemogenomic Library, Prestwick Chemical Library [10] |

| Genomic Collections | Gene-dosage assays for target ID | Yeast Knockout (YKO) collection (homozygous/heterozygous), DAmP collection, MoBY-ORF collection [15] [13] |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Phenotypic screening | Engineered cell lines, primary cells, high-content imaging reagents [13] |

| Target Expression Systems | Protein production for reverse screening | Recombinant protein expression (bacterial, insect, mammalian) [12] |

| Detection Reagents | Assay readouts | Fluorescent probes, antibodies, radioactive ligands [12] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Data analysis and prediction | Structure-activity relationship analysis, binding prediction algorithms [10] |

Implementation Workflow and Best Practices

Successful implementation of chemogenomics approaches requires careful experimental design and quality control. For both forward and reverse approaches, the quality of chemical libraries is paramount, and proper curation of both chemical structures and associated bioactivity data is essential [16]. This includes verification of structural integrity, stereochemistry, and removal of compounds with undesirable properties or potential assay interference [16].

For forward chemogenomics, critical considerations include the selection of phenotypic assays that are sufficiently robust and informative to support subsequent target identification efforts [9]. The assay should ideally have a clear connection to disease biology while being tractable for medium-to-high throughput screening [13].

For reverse chemogenomics, target credentialing is a essential preliminary step, requiring demonstration of the target's relevance to the disease process through genetic, genomic, or other biological evidence [11]. The development of physiologically relevant screening assays that maintain biological significance while enabling high-throughput operation remains a key challenge [11].

Forward and reverse chemogenomics represent complementary paradigms for target identification and validation in modern drug discovery. The forward approach offers the advantage of phenotypic relevance and potential for novel target discovery but faces challenges in target deconvolution [9] [13]. The reverse approach provides straightforward structure-activity optimization but is limited by existing biological knowledge and may suffer from poor translation to in vivo efficacy [11] [13].

The choice between these strategies depends fundamentally on the research context: forward approaches excel when exploring new biology or when phenotypic outcomes are clear but mechanisms obscure, while reverse approaches are optimal when well-validated targets exist and efficient optimization is prioritized [11] [9]. Increasingly, the most successful drug discovery programs integrate elements of both approaches, leveraging their complementary strengths to navigate the complex journey from initial hit to validated therapeutic target [11].

As chemogenomics continues to evolve, advances in computational prediction, screening technologies, and genomic tools will further blur the distinctions between these approaches, enabling more efficient identification and validation of targets for therapeutic development [15] [10]. The ultimate goal remains the same: to systematically connect chemical space to biological function, accelerating the discovery of new medicines for human disease.

This guide provides an objective comparison of three essential screening platforms—HIP/HOP, Phenotypic Profiling, and Mutant Libraries—used for validating chemogenomic hit genes. We summarize their performance characteristics, experimental protocols, and applications to help researchers select the appropriate method for their functional genomics and drug discovery projects.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and performance metrics of the three screening platforms.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Essential Screening Platforms

| Screening Platform | Typical Organism/System | Primary Readout | Key Performance Metrics | Key Applications in Hit Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIP/HOP Chemogenomics | S. cerevisiae (Barcoded deletion collections) | Fitness Defect (FD) scores from barcode sequencing [17] | High reproducibility between independent datasets (e.g., HIPLAB vs. NIBR); Identifies limited, robust cellular response signatures [17] | Direct, unbiased identification of drug target candidates and genes required for drug resistance; Functional validation of chemical-genetic interactions [17] |

| Phenotypic Profiling (Cell Painting) | Mammalian cell lines (e.g., HCT116 colorectal cancer) | Multiparametric morphological profiles from fluorescent imaging [18] [19] | Capable of clustering compounds by mechanism of action (MoA); Identifies convergent phenotypes beyond target class (18 distinct phenotypic clusters reported) [18] [19] | Unbiased MoA exploration; Identification of multi-target agents and off-target activities; Functional annotation of chemical compounds [18] [3] |

| Mutant Library Screening (SATAY/CRISPR) | S. cerevisiae (SATAY); Mammalian cells (CRISPR) | Fitness effects from transposon or sgRNA sequencing abundance [20] [21] | Identifies both loss- and gain-of-function mutations in a single screen; Confirms cellular vulnerabilities (fitness ratio); Amenable to multiplexing [21] | Validation of hit genes from pooled screens (e.g., using CelFi assay); Uncovering novel resistance mechanisms and gene essentiality [20] [21] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

HIP/HOP Chemogenomic Profiling

HIP/HOP employs barcoded yeast knockout collections to perform HaploInsufficiency Profiling (HIP) and HOmozygous Profiling (HOP) in a single, competitive pool [17].

- Strain Pool Construction: The pooled library consists of approximately 1,100 heterozygous deletion strains for essential genes (for HIP) and ~4,800 homozygous deletion strains for non-essential genes (for HOP), each tagged with unique molecular barcodes [17].

- Compound Treatment & Growth: The pooled strain library is exposed to a compound of interest. HIP identifies drug targets by detecting hypersensitivity in heterozygous strains where one copy of an essential gene is deleted. HOP identifies genes involved in drug resistance or the biological pathway of the drug target by detecting hypersensitivity in homozygous deletion strains [17].

- Barcode Sequencing & Analysis: Samples are collected after a set number of doublings. Genomic DNA is extracted, and barcodes are amplified and sequenced. Fitness Defect (FD) scores are calculated as robust z-scores of the log2 ratio of barcode abundance in control versus treatment conditions. Strains with the most negative FD scores indicate the greatest sensitivity [17].

Phenotypic Profiling via Cell Painting Assay

The Cell Painting Assay uses fluorescent dyes to stain and quantify morphological changes in cells treated with small molecules [18] [19].

- Cell Culture & Compound Treatment: HCT116 colorectal cancer cells are seeded into 384-well plates and incubated for 24 hours. Test compounds are added (e.g., at 1 µM) and cells are incubated for 48 hours [18] [19].

- Staining & Fixation: Cells are stained with a panel of fluorescent dyes to mark key cellular components:

- Image Acquisition & Analysis: Plates are imaged using a high-content screening platform (e.g., CellInsight CX7). Hundreds of morphological features are extracted per cell. Profiles are analyzed using dimensionality reduction techniques like t-SNE and clustered to group compounds inducing similar phenotypes [18] [19].

Mutant Library Screening with SATAY

SAturated Transposon Analysis in Yeast (SATAY) uses random transposon mutagenesis to probe gene function and drug resistance [21].

- Library Generation: A dense transposon library is generated in S. cerevisiae, where every gene is disrupted by multiple independent transposon insertions [21].

- Selection & Sequencing: The library is grown under selective pressure (e.g., sub-lethal concentrations of an antifungal compound). Genomic DNA is harvested, and transposon insertion sites are amplified and sequenced en masse using next-generation sequencing [21].

- Fitness Analysis: The change in abundance of each insertion mutant under selection versus control conditions reveals the effect on fitness. Insertions that become enriched indicate loss-of-function mutations conferring resistance, while depleted insertions indicate genes essential for survival under that condition [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and resources essential for implementing these screening platforms.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Platform | Key Reagent/Resource | Function/Description | Specific Example/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIP/HOP | Barcoded Yeast Deletion Collection | A pooled library of ~6,000 knockout strains with unique molecular barcodes for genome-wide fitness profiling [17]. | Commercially available collections (e.g., from GE Healthcare/Dharmacon) [17]. |

| Phenotypic Profiling | Cell Painting Dye Set | A panel of 5-6 fluorescent dyes to stain major organelles for holistic morphological profiling [18] [19]. | Commercially available kits, or individual dyes (e.g., Hoechst, Concanavalin A, WGA, Phalloidin, MitoTracker) [18]. |

| High-Content Imaging System | Automated microscope for high-throughput acquisition of fluorescent images from multi-well plates. | Systems like the CellInsight CX7 LED Pro HCS Platform [19]. | |

| Mutant Library Screening | Transposon or CRISPR Library | A defined pool of transposons or sgRNAs for generating genome-wide loss-of-function mutations. | SATAY transposon library for yeast [21]; Genome-wide CRISPR KO libraries (e.g., from DepMap) for mammalian cells [20]. |

| Cas9 Protein (for CRISPR) | Ribonucleoprotein complex for precise DNA cleavage in CRISPR-based knockout validation. | SpCas9 protein complexed with sgRNA as RNP for the CelFi assay [20]. |

Visualized Workflows and Logical Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for each screening platform.

Diagram 1: HIP/HOP Chemogenomic Workflow

Diagram 2: Cell Painting Phenotypic Profiling

Diagram 3: SATAY Mutant Library Screening

Interpreting Fitness Signatures and Chemogenomic Profiles

Comparative Analysis of Large-Scale Chemogenomic Datasets

Chemogenomic profiling is a powerful, unbiased approach for identifying drug targets and understanding the genome-wide cellular response to small molecules. The reproducibility and robustness of these assays are critical for drug discovery. A major comparative study analyzed the two largest independent yeast chemogenomic datasets: one from an academic laboratory (HIPLAB) and another from the Novartis Institute of Biomedical Research (NIBR) [17].

The table below summarizes the core differences and robust common findings between these two large-scale studies.

Table 1: Comparison of HIPLAB and NIBR Chemogenomic Profiling Studies

| Comparison Aspect | HIPLAB Dataset | NIBR Dataset | Common Finding / Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Scope | Over 35 million gene-drug interactions; 6,000+ unique profiles [17] | Over 35 million gene-drug interactions; 6,000+ unique profiles [17] | Combined analysis revealed robust, conserved chemogenomic response signatures [17] |

| Profiling Method | Haploinsufficiency Profiling (HIP) & Homozygous Profiling (HOP) [17] | HIP/HOP platform [17] | Both methods report drug-target candidates (HIP) and genes for drug resistance (HOP) [17] |

| Key Signatures Identified | 45 major cellular response signatures [17] | Independent dataset with distinct experimental design [17] | 66.7% (30/45) of HIPLAB signatures were conserved in the NIBR dataset [17] |

| Data Normalization | Normalized separately for strain tags; batch effect correction [17] | Normalized by "study id"; no batch effect correction [17] | Despite different pipelines, profiles for established compounds showed excellent agreement [17] |

| Fitness Deficit (FD) Score | Robust z-score based on log₂ ratios [17] | Inverse log₂ ratio with quantile normalization [17] | Both scoring methods revealed correlated profiles for drugs with similar Mechanisms of Action (MoA) [17] |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that chemogenomic fitness signatures are highly reproducible across independent labs. The substantial concordance, despite methodological differences, provides strong validation for using these profiles to identify candidate drug targets and understand mechanisms of action [17].

Experimental Protocols for Chemogenomic Profiling

HIP/HOP Profiling Methodology

The HaploInsufficiency Profiling (HIP) and HOmozygous Profiling (HOP) platform uses pooled yeast knockout collections to perform genome-wide fitness assays under drug perturbation [17]. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow.

Key Procedural Steps

- Pool Construction: A pool is created containing thousands of individual yeast strains, each with a unique gene deletion and a corresponding DNA barcode. The HIP assay uses heterozygous deletions of essential genes (~1,100 strains), while the HOP assay uses homozygous deletions of non-essential genes (~4,800 strains) [17].

- Competitive Growth & Compound Treatment: The entire pool of strains is grown competitively in liquid culture, both in the presence of the drug compound and in a DMSO control. This process is typically performed robotically to ensure consistency [17].

- Sample Collection: Cells are collected after a specific number of doublings (HIPLAB) or at fixed time points (NIBR). The difference in collection strategy can affect which slow-growing strains remain detectable in the pool [17].

- Barcode Amplification and Sequencing: Genomic DNA is extracted from the collected samples. The unique molecular barcodes for each strain are amplified via PCR and sequenced using high-throughput methods [17].

- Fitness Defect (FD) Score Calculation: The relative abundance of each strain in the drug-treated sample is compared to its abundance in the control. A significant decrease in abundance indicates drug sensitivity. The FD score is a normalized metric (e.g., a robust z-score) that quantifies this fitness defect [17].

Data Processing and Normalization

The comparison between the HIPLAB and NIBR studies highlights critical steps in data processing that impact the final fitness signatures.

Table 2: Key Data Processing Steps in Chemogenomic Profiling

| Processing Step | HIPLAB Protocol | NIBR Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Strain Abundance Metric | Median signal intensity used for calculating relative abundance [17] | Average signal intensity used for calculating relative abundance [17] |

| Data Normalization | Separate normalization for uptags/downtags; batch effect correction applied [17] | Normalization by "study id" (~40 compounds); no batch effect correction [17] |

| Strain Filtering | Tags failing signal intensity thresholds are removed; "best tag" selected per strain [17] | Tags with poor correlation in controls are removed; remaining tags are averaged [17] |

| Fitness Score | Robust z-score (median and MAD of all log₂ ratios) [17] | Z-score normalized using per-strain median and standard deviation across experiments [17] |

Validation and Impact of Genetic Evidence in Drug Discovery

The ultimate validation of a chemogenomic "hit" is its successful progression to an approved drug. Large-scale evidence now confirms that genetic support for a drug target significantly de-risks the development process. A 2024 analysis found that the probability of success for drug mechanisms with genetic support is 2.6 times greater than for those without it [22].

The following diagram illustrates how genetic evidence informs and validates the drug discovery pipeline.

Key Findings on Genetic Validation

- Impact on Clinical Success: Drug targets with human genetic evidence are 2.6 times more likely to succeed from clinical development to approval. This effect is most pronounced in later development phases (Phase II and III), where demonstrating clinical efficacy is critical [22].

- Confidence in Causal Genes Matters: The predictive power of genetic evidence is stronger when there is high confidence in the variant-to-gene mapping. For example, targets supported by Mendelian disease data (OMIM) showed a relative success of 3.7, higher than the average for GWAS [22].

- Therapy Area Variation: The boost from genetic evidence varies, with the highest relative success observed in haematology, metabolic, respiratory, and endocrine diseases (all >3x) [22].

- Connection to Disease Mechanism: Genetic support is more prevalent for drugs believed to be disease-modifying rather than those that merely manage symptoms. This is evidenced by the higher genetic support for drug targets that are specific to a particular disease, compared to "promiscuous" targets used across many diverse indications [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successfully performing chemogenomic profiling and validating fitness signatures requires a suite of specialized biological and computational tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomic Profiling

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Yeast Knockout Collections | Provides the pooled library of deletion strains for competitive growth assays. The foundation for HIP/HOP profiling. | Includes both heterozygous deletion pool (for essential genes) and homozygous deletion pool (for non-essential genes) [17]. |

| Molecular Barcodes (Uptags & Downtags) | Unique 20bp DNA sequences that act as strain identifiers, enabling quantification via sequencing. | Allows thousands of strains to be grown in a single culture and tracked simultaneously [17]. |

| Fitness Defect (FD) Scoring Pipeline | Computational method to normalize sequencing data and calculate strain fitness. | Different pipelines exist (e.g., HIPLAB uses robust z-scores; NIBR uses quantile-normalized z-scores), but both identify sensitive/resistant strains [17]. |

| Validated Compound Libraries | Collections of bioactive small molecules with known mechanisms of action, used for benchmarking and discovery. | Screening these libraries helps build a reference database of chemogenomic profiles for MoA prediction [17]. |

| Genetic Variants of Target Proteins | Recombinant proteins or cell lines expressing natural genetic variants to test target-drug interaction specificity. | Critical for assessing how population-level genetic variation impacts drug efficacy and validating target engagement [23]. |

In the field of chemical biology and drug discovery, understanding the connection between molecular targets and observable phenotypes is fundamental. Research primarily follows two complementary approaches: phenotype-based (forward) and target-based (reverse) chemical biology [24]. The forward approach begins with an observed phenotypic effect in cells or organisms and works to identify the underlying genetic targets and molecular mechanisms. Conversely, the reverse approach starts with a known, validated target of interest and seeks compounds that modulate its activity to produce a desired phenotypic outcome [24]. Both strategies are crucial for validating chemogenomic hit genes and advancing therapeutic development, particularly in complex disease areas like cancer and neglected tropical diseases where target diversity has been continually challenging [24] [25] [26].

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies and Workflows

Phenotype-Based (Forward) Chemical Biology

Experimental Protocol:

- Compound Screening: A library of chemical compounds is screened against cellular or organismal models to identify those that induce a relevant phenotypic change (e.g., reduced cell viability, altered morphology) [24].

- Hit Validation: Active compounds ("hits") are confirmed through dose-response studies and counter-screens to rule out non-specific effects.

- Target Deconvolution: The biological target(s) of the active compound are identified. A common and effective method is affinity capture, where the compound is linked to beads and used to pull down interacting proteins from cell homogenates [26]. The success of this method has been demonstrated for various target classes, including kinases, PARP, and HDAC inhibitors [26].

- Mechanistic Exploration: The signaling pathways and biological processes affected by target engagement are elucidated to understand the mechanism leading to the observed phenotype.

Recent advances have improved the efficiency of this process. For example, the DrugReflector framework uses a closed-loop active reinforcement learning model trained on compound-induced transcriptomic signatures to predict molecules that induce desired phenotypic changes, reportedly increasing hit rates by an order of magnitude compared to random library screening [27].

Target-Based (Reverse) Chemical Biology

Experimental Protocol:

- Target Selection: A protein or gene, validated to play a critical role in a disease-associated pathway, is selected [24].

- Assay Development: A high-throughput screening assay is developed to measure compound binding or functional modulation of the target (e.g., enzyme activity inhibition).

- Compound Screening & Hit Identification: A targeted or diverse compound library is screened against the assay. The Nur77-targeted library from Wu's group at Xiamen University, containing over 300 derivatives based on the natural agonist cytosporone-B, is a prime example of a targeted library [24].

- Phenotypic Validation: Confirmed hits are then tested in cellular or animal models to verify they produce the anticipated therapeutic phenotype.

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the parallel workflows and their convergence in the drug discovery process.

Comparative Analysis of Approaches

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of the two main approaches for connecting targets to phenotypes.

Table 1: Comparison of Phenotype-Based and Target-Based Approaches

| Feature | Phenotype-Based (Forward) | Target-Based (Reverse) |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Observable biological effect (phenotype) [24] | Known or hypothesized molecular target [24] |

| Typical Screening Library | Diverse natural/synthetic compounds; can leverage traditional knowledge like TCM herbs [24] | Targeted libraries (e.g., kinase-focused); chemogenomic libraries [24] |

| Key Challenge | Target deconvolution can be technically challenging and slow [26] | Requires prior, robust validation of the target's role in the disease [24] [25] |

| Major Strength | Biologically unbiased; can identify novel mechanisms and targets; clinically translatable [27] [26] | Mechanistically clear; more straightforward optimization of compound properties |

| Attrition Risk | Higher risk later in process if target identification fails or reveals an undruggable target | Higher risk earlier if biological validation of the target fails in complex systems |

| Illustrative Example | Discovery of ATRA and As2O3 for APL treatment, with targets identified later [24] | Development of I-BET bromodomain inhibitors based on known target function [24] |

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful experimentation in this field relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential components for setting up relevant experiments.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Libraries | Collections of stored chemicals with associated structural and purity data [24]. | High-throughput screening to identify initial probe compounds or drug leads [24]. |

| Affinity Capture Beads | Matrices (e.g., agarose beads) for immobilizing compounds to pull down interacting proteins from complex biological samples [26]. | Target deconvolution for phenotypic screening hits; identification of direct molecular targets [26]. |

| Transcriptomic Signatures | Datasets profiling global gene expression changes in response to compound treatment (e.g., from Connectivity Map) [27]. | Training computational models (e.g., DrugReflector) to predict compounds that induce a desired phenotype [27]. |

| Validated Phenotype Algorithms | Computable definitions for health conditions using electronic health data, balancing sensitivity and specificity [28]. | Ensuring accurate cohort selection in observational research and retrospective analysis of drug effects [28]. |

| Genetically Encoded Sensors | Engineered biological systems that report on cellular activities in a dynamic manner [24]. | Probing signaling processes and cellular functions in real-time within live cells or organisms [24]. |

Case Studies in Cancer and Disease

Phenotype-Based Discovery: The Nur77 Story

Research on the orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 provides a powerful case study of the phenotype-based approach. A unique compound library was built by designing and synthesizing over 300 derivatives based on the natural agonist cytosporone-B [24]. Screening this library revealed compounds that induced distinct phenotypes by modulating Nur77 in different ways:

- Compound TMPA: Was found to bind Nur77, disrupting its interaction with LKB1. This led to LKB1 translocation to the cytoplasm and activation of AMPK, ultimately lowering glucose levels in diabetic mice [24].

- Compound THPN: Triggered the movement of Nur77 to mitochondria, where it interacted with Nix and ANT1. This caused mitochondrial pore opening and membrane depolarization, leading to irreversible autophagic cell death in melanoma cells and inhibition of metastasis in a mouse model [24].

This work not only produced valuable chemical tools but also elucidated novel, non-genomic signaling mechanisms of Nur77.

The Critical Role of Target Product Profiles (TPP) in Reverse Approaches

In target-based discovery, the Target Product Profile (TPP) is a crucial strategic tool that links target properties to clinical goals. A TPP is a list of the essential attributes required for a drug to be clinically successful and represents a significant benefit over existing therapies [25]. It defines the target patient population, acceptable efficacy and safety levels, dosing regimen, and cost of goods. The TPP is used to guide decisions throughout the drug discovery process, from target selection to clinical trial design, ensuring the final product meets the unmet medical need [25]. For example, a TPP for a new anti-malarial drug would specify essential features like oral administration, low cost (~$1 per course), efficacy against drug-resistant parasites, and stability under tropical conditions [25].

Advanced Concepts and Future Directions

Addressing Algorithm and Sample Size Challenges in Phenomics

The accurate definition and measurement of phenotypes is a critical challenge. In computational phenomics, using narrow phenotype algorithms (e.g., requiring a second diagnostic code) increases Positive Predictive Value (PPV) but decreases sensitivity compared to broad, single-code algorithms [28]. However, this practice incurs immortal time bias—a period of follow-up during which the outcome cannot occur because of the exposure definition [28]. The proportion of immortal time is highest when the required time window for the second code is long and the outcome time-at-risk is short [28].

Similarly, in neuroimaging-based phenotype prediction, performance scales as a power-law function of sample size. While accuracy improves 3- to 9-fold when the sample size increases from 1,000 to 1 million participants, achieving clinically useful prediction levels for many cognitive and mental health traits may require prohibitively large sample sizes, suggesting fundamental limitations in the predictive information within current imaging modalities [29].

Future Outlook

The future of connecting targets to phenotypes lies in the integration of approaches and technologies. Leveraging artificial intelligence for virtual phenotypic screening [27], combining multiple data modalities (e.g., structural and functional MRI) to boost prediction accuracy [29], and further developing dynamic methods like proximity-dependent labeling for mapping protein interactions [24] will be key. These advanced techniques will accelerate the validation of chemogenomic hit genes and the development of novel, precision therapeutics.

Validation Methodologies: Experimental and Computational Approaches

Orthogonal Biochemical Assays for Target Confirmation

In the challenging landscape of chemogenomic research, where vast libraries of small molecules are screened against numerous potential targets, confirming true positive hits represents a critical bottleneck. The complexity of biological systems and the prevalence of assay artifacts necessitate robust validation strategies. Orthogonal biochemical assays—employing different physical or chemical principles to measure the same biological event—have emerged as indispensable tools for confirming target engagement and compound efficacy. This approach provides independent verification that significantly reduces false positives and builds confidence in hit validation, ultimately accelerating the transition from initial screening to viable lead compounds in drug discovery pipelines.

The Critical Role of Orthogonality in Hit Validation

Orthogonal assays are fundamental to addressing the reproducibility crisis in preclinical research. By utilizing different detection methods, readouts, or experimental conditions to probe the same biological interaction, researchers can distinguish true target engagement from assay-specific artifacts.

Key Benefits of Orthogonal Assay Strategies

Minimization of False Positives: Compounds that interfere with specific detection technologies (e.g., fluorescence quenching, absorbance interference) can be identified and eliminated early. An assay cascade effectively removes pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) that otherwise consume valuable resources [30].

Enhanced Confidence in Hits: Consistent activity across multiple assay formats with different detection principles provides compelling evidence for genuine biological activity rather than technology-specific artifacts [31].

Mechanistic Insight: Combining assays that measure different aspects of target engagement (e.g., binding affinity, functional inhibition, cellular penetration) offers a more comprehensive understanding of compound mechanism of action [30].

Orthogonal Assay Methodologies and Experimental Design

Biochemical Assay Platforms

Direct Product Detection Methods

Mass spectrometry-based approaches, such as the RapidFire MS assay developed for WIP1 phosphatase, enable direct quantification of enzymatically dephosphorylated peptide products. This method provides high sensitivity with a limit of quantitation at 28.3 nM and excellent robustness (Z'-factor of 0.74), making it suitable for high-throughput screening in 384-well formats [31]. The incorporation of 13C-labeled internal standards further enhances quantification accuracy.

Fluorescence-Based Detection

The red-shifted fluorescence assay utilizing rhodamine-labeled phosphate binding protein (Rh-PBP) represents an orthogonal approach that detects the inorganic phosphate (Pi) released during enzymatic reactions. This real-time measurement capability enables kinetic studies and is scalable to 1,536-well formats for ultra-high-throughput applications [31].

Universal Detection Technologies

Platforms like the Transcreener ADP² Kinase Assay and AptaFluor SAH Methyltransferase Assay offer broad applicability across multiple enzyme classes by detecting universal reaction products (e.g., ADP, SAH). These homogeneous "mix-and-read" formats minimize handling steps and are compatible with various detection methods including fluorescence intensity (FI), fluorescence polarization (FP), and time-resolved FRET (TR-FRET) [32].

Table 1: Comparison of Orthogonal Biochemical Assay Platforms

| Assay Platform | Detection Principle | Throughput Capability | Key Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RapidFire MS | Mass spectrometric detection of reaction products | 384-well format | Phosphatases, kinases, proteases | Direct product measurement, high specificity |

| Phosphate Binding Protein | Fluorescence detection of released Pi | 1,536-well format | Phosphatases, ATPases, nucleotide-processing enzymes | Real-time kinetics, high sensitivity |

| Transcreener | Competitive immuno-detection of ADP | 384- and 1,536-well | Kinases, ATPases, GTPases | Universal platform, multiple readout options |

| Coupled Enzyme | Secondary enzyme system generating detectable signal | 384-well format | Various enzyme classes | Signal amplification, established protocols |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

RapidFire MS Assay for Phosphatase Activity

Reaction Setup: Incubate WIP1 phosphatase with native phosphopeptide substrates (e.g., VEPPLpSQETFS) in optimized buffer containing Mg2+/Mn2+ cofactors [31].

Reaction Quenching: Add formic acid to terminate enzymatic activity at predetermined timepoints.

Internal Standard Addition: Spike samples with 1 μM 13C-labeled product peptide as an internal calibration standard.

Automated MS Analysis: Utilize RapidFire solid-phase extraction coupled to MS for high-throughput sample processing with specific instrument settings (precursor ion: 657.3; product ions: 1061.5, 253.2; positive polarity) [31].

Data Analysis: Quantify dephosphorylated product using integrated peak areas normalized to internal standard, with linear calibration curves (0-2.5 μM range) [31].

Phosphate Sensor Fluorescence Assay

Reagent Preparation: Express and purify rhodamine-labeled phosphate binding protein (Rh-PBP) following published protocols [31].

Assay Assembly: Combine enzyme, substrate, and test compounds in low-volume microplates suitable for fluorescence detection.

Real-Time Monitoring: Continuously measure fluorescence signal (excitation/emission suitable for red-shifted fluorophores) to monitor Pi release kinetics.

Data Processing: Calculate initial velocities from linear phase of progress curves and determine inhibitor potency (IC50) through dose-response analysis.

Strategic Implementation in the Validation Cascade

A well-designed orthogonal assay cascade systematically progresses from primary screening to confirmed hits through multiple validation tiers. This strategic approach efficiently eliminates artifacts while building comprehensive understanding of genuine actives.

The validation cascade systematically eliminates various categories of false positives while building evidence for true target engagement. Detection artifacts are removed through orthogonal biochemical assays, while non-specific binders and promiscuous inhibitors are filtered out through biophysical confirmation and selectivity profiling [30].

Integration with Complementary Validation Techniques

Biophysical Methods for Target Engagement

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) provides direct binding information including affinity (KD) and binding kinetics (kon, koff), making it invaluable for confirming target engagement after initial orthogonal biochemical confirmation [30]. SPR is compatible with 384-well formats, enabling moderate throughput for hit triaging.

Differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) detects ligand-induced thermal stabilization of target proteins, offering a high-throughput, label-free method to confirm binding. The cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) extends this principle to intact cells, verifying target engagement in physiologically relevant environments [30].

X-ray crystallography remains the gold standard for confirming binding mode and providing structural insights for optimization, though its lower throughput positions it later in the validation cascade [30].

Mechanistic and Kinetic Characterization

Determining mechanism of inhibition through kinetic studies (e.g., effect on Km and Vmax) provides critical information about compound binding to enzyme-substrate complexes [30]. Assessment of reversibility through rapid dilution experiments distinguishes covalent from non-covalent inhibitors, with significant implications for drug discovery programs.

Research Reagent Solutions for Orthogonal Assays

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Orthogonal Assay Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Assay Development | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universal Detection Kits | Transcreener ADP2, AptaFluor SAH | Detect common enzymatic products across multiple target classes | Enable broad screening campaigns with consistent readouts |

| Phosphate Detection | Rhodamine-labeled PBP, Malachite Green | Quantify phosphatase activity through Pi release | Different sensitivity ranges and interference profiles |

| Mass Spec Standards | 13C-labeled peptide substrates | Internal standards for quantitative MS assays | Improve accuracy and reproducibility of quantification |

| Coupling Enzymes | Lactate Dehydrogenase, Pyruvate Kinase | Enable coupled assays for various enzymatic activities | Potential source of interference if not properly controlled |

| Specialized Substrates | DiFMUP, FDP, phosphopeptides | Provide alternative readouts for orthogonal confirmation | Varying physiological relevance and kinetic parameters |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Statistical Validation of Assay Performance

Robust assay performance is prerequisite for reliable hit confirmation. The Z'-factor, a statistical parameter comparing the separation between positive and negative controls to the data spread, should exceed 0.5 for screening assays, indicating excellent separation capability [32]. Signal-to-background ratios greater than 5 and coefficients of variation below 10% further validate assay quality.

Hit Progression Criteria

Systematic hit prioritization integrates data from multiple orthogonal assays:

Potency Consistency: Compounds should demonstrate similar potency rankings across different assay formats, though absolute IC50 values may vary due to different assay conditions and detection limits [31].

Structure-Activity Relationships: Clusters of structurally related compounds with consistent activity profiles increase confidence in genuine structure-activity relationships rather than assay-specific artifacts [30].

Selectivity Patterns: Meaningful selectivity profiles across related targets (e.g., within kinase families) provide additional validation of specific target engagement.

Case Study: WIP1 Phosphatase Inhibitor Discovery

The development of orthogonal assays for WIP1 phosphatase exemplifies the power of this approach. Researchers established a mass spectrometry-based assay using native phosphopeptide substrates alongside a red-shifted fluorescence assay detecting phosphate release [31]. This combination enabled successful quantitative high-throughput screening of the NCATS Pharmaceutical Collection (NPC), with subsequent confirmation through surface plasmon resonance binding studies [31]. The orthogonal approach validated WIP1 inhibitors while eliminating technology-specific false positives that could have derailed the discovery campaign.

Orthogonal biochemical assays represent a cornerstone of rigorous hit validation in chemogenomic research and drug discovery. By implementing a strategic cascade of complementary assays with different detection technologies and principles, researchers can effectively distinguish true target engagement from assay artifacts. The integration of biochemical, biophysical, and cellular approaches provides a comprehensive framework for confirming compound activity, ultimately leading to more robust and reproducible research outcomes. As drug discovery efforts increasingly target challenging proteins with complex mechanisms, the systematic application of orthogonal validation strategies will remain essential for translating initial screening hits into viable therapeutic candidates.

Leveraging Chemogenomic Libraries for Systematic Validation

The transition from phenotypic screening to understood mechanism of action represents a major bottleneck in modern drug discovery. Chemogenomic libraries have emerged as a powerful solution to this challenge, providing systematic frameworks for linking chemical perturbations to biological outcomes. These libraries are carefully curated collections of small molecules with annotated biological activities, designed to cover a significant portion of the druggable genome. Their fundamental value in hit validation lies in the ability to connect observed phenotypes to specific molecular targets through pattern recognition and comparative analysis. When a compound from a chemogenomic library produces a phenotypic effect, its known target annotations immediately generate testable hypotheses about the mechanism of action, significantly accelerating the target deconvolution process that traditionally follows phenotypic screening [33].

The composition and design of these libraries directly influence their effectiveness in validation workflows. Unlike diverse compound collections used in initial screening, chemogenomic libraries are enriched with tool compounds possessing defined mechanisms of action and known target specificities. This intentional design transforms them from simple compound collections into dedicated experimental tools for biological inference. The strategic application of these libraries enables researchers to move beyond simple hit identification toward systematic validation of chemogenomic hit genes, creating a more efficient path from initial observation to mechanistically understood therapeutic candidates [34] [33].

Comparative Analysis of Chemogenomic Libraries

The utility of a chemogenomic library for systematic validation depends on its specific composition, target coverage, and polypharmacology profile. Different libraries are optimized for distinct applications, ranging from broad target identification to focused pathway analysis.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Chemogenomic Libraries

| Library Name | Size (Compounds) | Key Characteristics | Polypharmacology Index (PPindex) | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSP-MoA | Not Specified | Optimized to target the liganded kinome | 0.9751 (All), 0.3458 (Without 0/1 target bins) | Kinase-focused screening, pathway validation |

| DrugBank | ~9,700 | Includes approved, biotech, and experimental drugs | 0.9594 (All), 0.7669 (Without 0 target bin) | Broad target deconvolution, drug repurposing |

| MIPE 4.0 | 1,912 | Small molecule probes with known mechanism of action | 0.7102 (All), 0.4508 (Without 0 target bin) | Phenotypic screening, mechanism identification |

| Microsource Spectrum | 1,761 | Bioactive compounds for HTS or target-specific assays | 0.4325 (All), 0.3512 (Without 0 target bin) | General bioactive screening, initial hit finding |

The Polypharmacology Index (PPindex) provides a crucial metric for library selection, quantitatively representing the overall target specificity of each collection. Libraries with higher PPindex values (closer to 1) contain compounds with greater target specificity, making them more suitable for straightforward target deconvolution. Conversely, libraries with lower PPindex values contain more promiscuous compounds, which may complicate validation but can reveal polypharmacological effects [34]. This quantitative assessment enables researchers to match library characteristics to their specific validation needs, whether pursuing single-target validation or exploring multi-target therapeutic strategies.

Experimental Approaches for Systematic Validation

Integrating Chemogenomic Libraries with Network Pharmacology

A powerful methodology for systematic validation combines chemogenomic libraries with network pharmacology approaches. This integrated framework creates a comprehensive system for linking compound activity to biological mechanisms through multiple data layers. The experimental workflow begins with assembling a network pharmacology database that integrates drug-target relationships from sources like ChEMBL, pathway information from KEGG, gene ontologies, disease associations, and morphological profiling data from assays such as Cell Painting [33]. Subsequently, a curated chemogenomic library of approximately 5,000 small molecules representing diverse drug targets and biological processes is screened against the phenotypic assay of interest. The resulting activity data is then mapped onto the network pharmacology framework to identify connections between compound targets, affected pathways, and observed phenotypes, enabling hypothesis generation about the mechanisms underlying the phenotype [33].

The critical validation phase employs multiple orthogonal approaches to confirm predictions. Gene Ontology and pathway enrichment analysis identifies biological processes significantly enriched among the targets of active compounds. Morphological profiling compares the cellular features induced by hits to established bioactivity patterns, providing additional evidence for mechanism of action. Finally, scaffold analysis groups active compounds by chemical similarity, distinguishing true structure-activity relationships from spurious associations. This multi-layered validation strategy significantly increases confidence in identified targets and mechanisms by converging evidence from chemical, biological, and phenotypic domains [33].

CRISPR-Cas9 Chemogenomic Profiling for Target Identification

CRISPR-Cas9 based chemogenomic profiling represents a sophisticated genetic approach for target identification and validation. This method enables genome-wide screening for genes whose modulation alters cellular sensitivity to small molecules, directly revealing efficacy targets and resistance mechanisms.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas9 Chemogenomic Profiling

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|