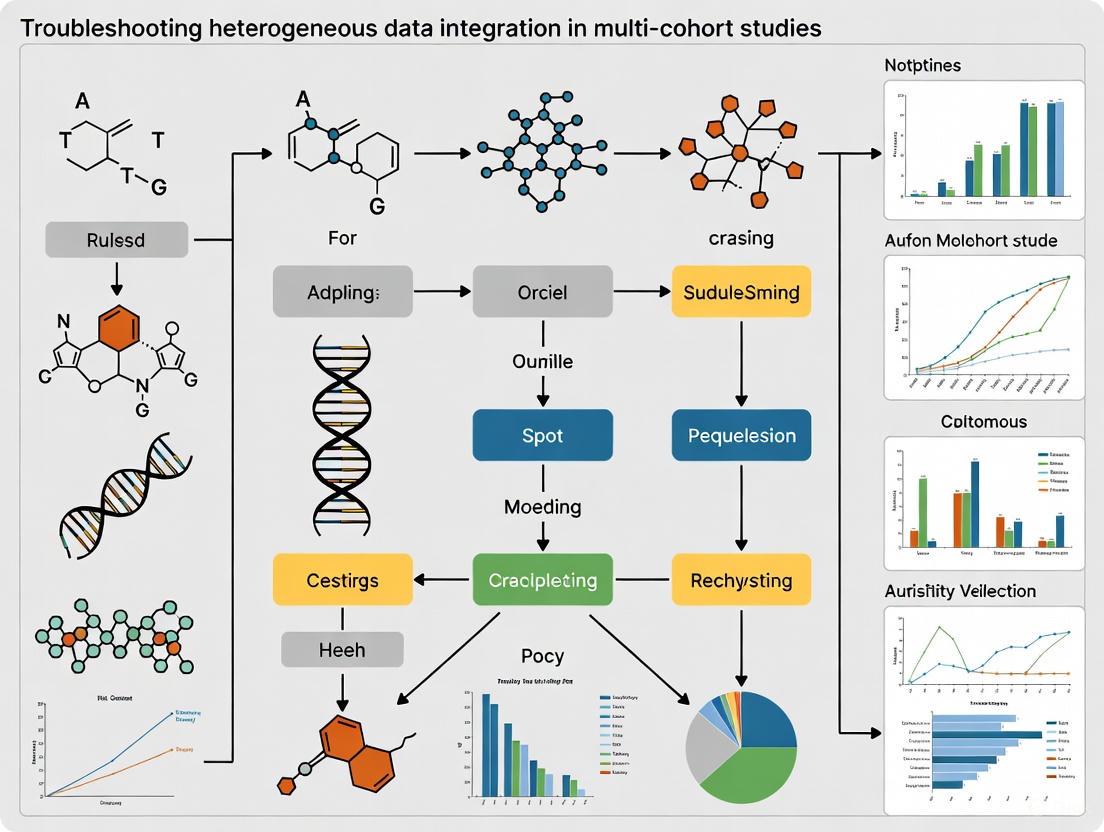

Troubleshooting Heterogeneous Data Integration in Multi-Cohort Studies: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Integrating heterogeneous data from multiple cohort studies is crucial for enhancing statistical power and enabling novel discoveries in biomedical research, yet it presents significant challenges in data harmonization, technical variability,...

Troubleshooting Heterogeneous Data Integration in Multi-Cohort Studies: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

Integrating heterogeneous data from multiple cohort studies is crucial for enhancing statistical power and enabling novel discoveries in biomedical research, yet it presents significant challenges in data harmonization, technical variability, and analytical methodology. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals, covering foundational concepts, practical methodologies, common troubleshooting scenarios, and validation techniques. By addressing key intents from exploration to validation, it offers actionable strategies to overcome data inconsistency, implement robust integration pipelines, and build generalizable models, ultimately facilitating more reliable and impactful multi-cohort research.

Understanding the Landscape: Core Concepts and Challenges of Heterogeneous Data in Multi-Cohort Research

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary types of data formats encountered in biomedical research, and how do they differ? Biomedical data is categorized into three main formats, each with distinct characteristics [1]:

- Structured Data: Highly organized data that fits into predefined models and is easily searchable. Examples in healthcare include patient demographics in Electronic Health Records (EHRs), medical billing codes (CPT, ICD), and clinical trial data like patient enrollment and outcomes [1]. This data is typically stored in rows and columns within relational databases.

- Unstructured Data: Data that lacks a predefined format or structure. This constitutes the majority (approximately 80% or more) of healthcare data [2] [3] [4]. Examples include clinical notes, medical images (X-rays, MRIs), pathology reports, and doctors' audio dictations [1] [4]. Analyzing this data requires advanced techniques like Natural Language Processing (NLP) and image recognition.

- Semi-Structured Data: Data that does not conform to a rigid schema but contains tags or other markers to enforce a hierarchy of records and fields. Examples include HL7 FHIR resources, C-CDA documents for health information exchange, and JSON or XML files [1] [5]. It balances structure with flexibility, facilitating data exchange between disparate systems.

Q2: What are the most significant challenges when integrating these heterogeneous data types in multi-cohort studies? Integrating heterogeneous data presents a cascade of challenges [6], which can be categorized as follows:

- Technical and Semantic Heterogeneity: Data sources vary in structure, format, and content. Combining data from different hospitals, registries, and omics technologies often involves matching patient variables by hand due to a lack of common data standards, which is time and resource-intensive [7] [8].

- Data Complexity and Preprocessing: Unstructured and semi-structured data require significant preprocessing and feature extraction before they can be analyzed or integrated [9] [3]. This includes cleaning, normalizing, and transforming data, which is complicated by the high-dimensional nature of biomedical data where variables often far outnumber samples [6].

- Interoperability and Schema Evolution: The lack of fixed schema in semi-structured and unstructured data, along with the use of different terminology systems (e.g., SNOMED-CT, RxNorm), creates interoperability barriers [8]. Furthermore, schemas can evolve over time, complicating integration efforts [5].

- Regulatory and Privacy Concerns: Fusing data streams increases the risk of patient re-identification. Managing sensitive health data requires strict adherence to privacy laws like HIPAA and GDPR, which governs data de-identification, consent processes, and access control [8] [4].

Q3: What methodologies can be used to categorize and merge unstructured clinical data from different sources? One effective methodology involves semantic categorization and clustering [9]:

- Sub-category Identification: Begin with the existing titles or labels provided by dataset providers (e.g., "Diagnosis," "Differential Diagnosis").

- Semantic Similarity Computation: Extract semantic information from the unstructured text in these sub-categories. Use medical ontologies to identify terms and compute semantic similarity between sub-categories from different datasets. Techniques like hierarchical clustering and similarity measures such as Hausdorff distance can be employed.

- Cluster and Merge: Group semantically similar sub-categories (e.g., "Findings," "Observation," and "Diagnosis") into clusters. Based on the contents of the merged data elements, identify attributes for a new, integrated database schema. This approach has been shown to reduce the number of original sub-categories significantly, enabling the design of a unified schema [9].

Q4: How can Natural Language Processing (NLP) transform unstructured data for use in research? NLP uses several core processes to convert unstructured text into structured, analyzable information [4]:

- Tokenization: Breaking down text into smaller units like words or phrases.

- Named Entity Recognition (NER): Identifying and classifying key entities such as patient names, medications, and diseases.

- Sentiment Analysis: Assessing the tone or emotion in text, useful for analyzing patient feedback.

- Text Classification: Assigning categories or labels to text, such as flagging a clinical note as "urgent." These techniques allow for the extraction of clinical information from doctors' notes, automation of medical coding and billing, acceleration of drug discovery by scanning research papers, and improvement of clinical trial matching by analyzing patient records [4].

Q5: What are the common strategies for integrating multi-omics data, which is inherently heterogeneous? Multi-omics data integration strategies for vertical data (data from different omics layers) can be categorized into five types [6]:

- Early Integration: All omics datasets are concatenated into a single large matrix before analysis. This is simple but can result in a complex, high-dimensional matrix.

- Mixed Integration: Each dataset is separately transformed into a new representation and then combined, which helps reduce noise and dimensionality.

- Intermediate Integration: Datasets are integrated simultaneously to produce both common and omics-specific representations.

- Late Integration: Each omics dataset is analyzed separately, and the final predictions or results are combined. This does not capture inter-omics interactions well.

- Hierarchical Integration: Prior knowledge about regulatory relationships between different omics layers is incorporated, truly embodying the goal of trans-omics analysis, though this is a nascent field.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Data Format and Schema Mismatches

Problem: Researchers encounter errors when trying to query or combine datasets due to incompatible structures or schemas (e.g., different date formats, missing fields, or varying code systems).

Investigation & Solution:

| Step | Action | Example/Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Profiling | Systematically analyze the structure, content, and quality of all source datasets. | Identify differences in data types (e.g., string vs. categorical), value formats (e.g., DD/MM/YYYY vs. MM-DD-YYYY), and the use of controlled terminologies (e.g., different ICD code versions) [7]. |

| 2. Standardization | Map data elements to common data models (CDMs) and standard terminologies. | Adopt models like OMOP CDM or use standards like FHIR for semi-structured data [1] [8]. Map local medication codes to a standard like RxNorm [8]. |

| 3. Schema Mapping | Define explicit rules to transform source schemas to a unified target schema. | Create a mapping table that defines how each source field (e.g., Pat_DOB, PatientBirthDate) corresponds to the target integrated field (e.g., birth_date). Tools with mapping engines can automate this for structured data [2]. |

| 4. Validation | Perform checks to ensure data integrity and accuracy after transformation. | Run queries to check for null values in critical fields, validate that value ranges are plausible, and spot-check mapped records against source data. |

Guide 2: Addressing High Preprocessing Burden for Unstructured Data

Problem: The effort required to clean, normalize, and extract features from unstructured data (like clinical notes) is prohibitive and delays analysis.

Investigation & Solution:

| Step | Action | Example/Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Tool Selection | Implement an NLP pipeline suited to the biomedical domain. | Use NLP libraries with pre-trained models for tasks like tokenization, Named Entity Recognition (NER), and sentiment analysis specifically tuned for clinical text [4]. |

| 2. Information Extraction | Apply the NLP pipeline to convert unstructured text into structured data. | Extract entities such as diagnoses, medications, and symptoms from clinical notes and insert them into structured fields in a database [4]. |

| 3. Dimensionality Reduction | Apply techniques to manage the high number of features resulting from data integration. | When integrating diverse data, the resulting matrix can be highly dimensional. Use techniques like PCA or autoencoders to create efficient abstract representations of the data, reducing complexity for downstream analysis [8] [6]. |

| 4. Workflow Automation | Script the preprocessing steps into a reproducible workflow. | Use a data processing framework (e.g., based on Snowpark or similar) to create a reusable pipeline that handles data loading, transformation, and feature extraction, reducing manual effort for subsequent studies [1]. |

Guide 3: Managing Data Integration and Computational Workflows

Problem: Data integration workflows are computationally intensive, difficult to scale, and yield inconsistent results.

Investigation & Solution:

| Step | Action | Example/Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Architecture Choice | Select a data integration strategy aligned with your research question. | Choose between horizontal integration (combining data from different studies measuring the same entities) and vertical integration (combining data from different omics levels) and select a corresponding strategy (early, intermediate, or late integration) [6]. |

| 2. Parallel Processing | Leverage distributed computing frameworks to handle large data volumes. | Use platforms like Snowflake or Apache Spark that support parallel processing to distribute the computational workload, significantly improving processing time for complex queries on large, semi-structured, and unstructured datasets [1] [5]. |

| 3. Provenance Tracking | Implement systems to track the origin and processing history of all data. | Maintain metadata about data sources, transformation steps, and algorithm parameters. This is crucial for reproducibility, auditability, and debugging in complex, multi-step integration pipelines [8]. |

Table 1: Comparison of Data Formats in Biomedical Research

| Aspect | Structured Data | Semi-Structured Data | Unstructured Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Data with fixed attributes, types, and formats in a predefined schema [5]. | Data with some structure (tags, metadata) but no rigid data model [5]. | Data not in a pre-defined structure, requiring substantial preprocessing [3]. |

| Prevalence in Healthcare | Makes up a smaller proportion; ~50% of clinical trial data can be structured [2]. | Not explicitly quantified, but used in key interoperability standards. | Majority of data; estimates of 80% or more [2] [3] [4]. |

| Examples | EHR demographic fields, lab results, billing codes [1]. | FHIR resources, C-CDA documents, JSON, XML [1] [5]. | Clinical notes, medical images, pathology reports [1] [4]. |

| Ease of Analysis | Easy to search and analyze with traditional tools and SQL [1]. | Requires specific query languages (XQuery, SPARQL) or processing [1] [5]. | Requires advanced techniques (NLP, machine learning, image recognition) [1] [4]. |

| Primary Challenge | Limited view of patient context [4]. | Schema evolution, query efficiency [5]. | High volume, complexity, and preprocessing needs [3] [4]. |

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration Strategies for Vertical Data [6]

| Integration Strategy | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Concatenates all datasets into a single matrix before analysis. | Simple and easy to implement. | Creates a complex, noisy, high-dimensional matrix; discounts data distribution differences. |

| Mixed Integration | Transforms each dataset separately before combining. | Reduces noise, dimensionality, and dataset heterogeneities. | Requires careful transformation. |

| Intermediate Integration | Integrates datasets simultaneously to output common and specific representations. | Captures interactions between datatypes. | Requires robust pre-processing due to data heterogeneity. |

| Late Integration | Analyzes each dataset separately and combines the final predictions. | Avoids challenges of assembling different datatypes. | Does not capture inter-omics interactions. |

| Hierarchical Integration | Incorporates prior knowledge of regulatory relationships between omics layers. | Truly embodies trans-omics analysis; reveals interactions across layers. | Nascent field; methods are often less generalizable. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Semantic Categorization and Merging of Clinical Data

This methodology is designed to integrate unstructured clinical data from different sources by leveraging semantic similarity [9].

Detailed Methodology:

- Data Acquisition and Sub-category Identification: Collect clinical data from multiple heterogeneous sources (e.g., public medical datasets like EURORAD, MIRC RSNA). Identify the existing sub-categories provided within these datasets, which are titles describing the information type (e.g., "History," "Diagnosis," "Imaging Findings").

- Semantic Information Extraction: For each sub-category, process the underlying unstructured text data (clinical cases) to extract semantic information. This involves using medical ontologies to identify and standardize key terms and concepts.

- Similarity Computation and Clustering: Compute the semantic similarity between all pairs of sub-categories from different datasets. Use a measure like Hausdorff distance. Employ a hierarchical clustering algorithm to group sub-categories based on their semantic similarity. A predetermined confidence threshold (e.g., empirically set based on cluster analysis) is used to determine which sub-categories are sufficiently similar.

- Cluster Merging and Schema Design: Merge the clustered sub-categories to form new, unified super-categories (e.g., merging "Findings," "Observation," and "Diagnosis" into one category). Analyze the content of the merged data elements to identify the necessary attributes. Use these attributes to design a final, integrated database schema.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Semantic Data Integration

Protocol 2: NLP-Powered Transformation of Clinical Notes

This protocol details the process of converting unstructured clinical notes into a structured, analyzable format using a standard NLP pipeline [4].

Detailed Methodology:

- Data Collection: Source raw, unstructured text from clinical narratives, such as doctors' notes, discharge summaries, or radiology reports stored in EHRs.

- NLP Preprocessing:

- Tokenization: Break the text into individual words, phrases, or sentences (tokens).

- Dependency Parsing: Analyze the grammatical structure of sentences to understand how words relate to each other, capturing context and nuance.

- Information Extraction:

- Named Entity Recognition (NER): Identify and classify relevant clinical entities within the tokenized text. This includes extracting mentions of diseases, medications, procedures, symptoms, and anatomical sites.

- Text Classification: Categorize entire documents or sections of text into predefined classes (e.g., "urgent" vs. "routine," or by medical specialty).

- Post-processing and Storage: Validate and normalize the extracted entities (e.g., mapping medication names to standard codes). Insert the structured output into designated fields in a database or EHR for further analysis, reporting, or use in clinical decision support systems.

Diagram Title: NLP Pipeline for Unstructured Text

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Heterogeneous Data Integration

| Tool / Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| OMOP Common Data Model (CDM) | A standardized data model that allows for the systematic analysis of disparate observational databases by transforming data into a common format [1]. | Enables large-scale analytics across multiple institutions and structured EHR data. |

| FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) | A standard for exchanging healthcare information electronically using RESTful APIs and resources in JSON or XML format [1] [8]. | Facilitates the exchange of semi-structured data between EHRs, medical devices, and research applications. |

| NLP Libraries (e.g., CLAMP, cTAKES) | Software toolkits with pre-trained models for processing clinical text. Perform tasks like tokenization, NER, and concept mapping [4]. | Essential for extracting structured information from unstructured clinical notes and reports. |

| Snowflake / Distributed Computing Platforms | A cloud data platform that supports processing and analyzing structured and semi-structured data (JSON, XML) at scale, leveraging parallel computing [1]. | Handles large-volume data integration and transformation workloads, including for healthcare interoperability standards. |

| i2b2 (Informatics for Integrating Biology & the Bedside) | An open-source analytics platform designed to create and query integrated clinical data repositories for translational research [8]. | Used for cohort discovery and data integration in clinical research networks. |

| HYFTs Framework (MindWalk) | A proprietary framework that tokenizes biological sequences into a common data language, enabling one-click normalization and integration of multi-omics data [6]. | Aims to simplify the integration of heterogeneous public and proprietary omics data for researchers. |

Understanding Core Data Structures and Integration Types

What is the fundamental difference between horizontal and vertical data integration?

The terms "horizontal" and "vertical" describe how multi-omics datasets are organized and integrated, corresponding to the complexity and heterogeneity of the data [6].

Horizontal integration (also called homogeneous integration) involves combining data from across different studies, cohorts, or labs that measure the same omics entities [6]. For example, combining gene expression data from multiple independent studies on the same disease [10] [11]. This approach typically deals with data generated from one or two technologies for a specific research question across a diverse population, representing a high degree of real-world biological and technical heterogeneity [6].

Vertical integration (also called heterogeneous integration) involves analyzing multiple types of omics data collected from the same subjects [12] [11]. This includes data generated using multiple technologies probing different aspects of the research question, traversing various omics layers including genome, metabolome, transcriptome, epigenome, proteome, and microbiome [6]. A typical example would be collectively analyzing gene expression data along with their regulators (such as mutations, DNA methylation, and miRNAs) from the same patient cohort [11].

Table: Comparison of Horizontal vs. Vertical Integration Approaches

| Feature | Horizontal Integration | Vertical Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Data Source | Multiple studies/cohorts measuring same variables [6] | Multiple omics layers from same subjects [12] |

| Primary Goal | Increase sample size, validate findings across populations [13] | Understand regulatory relationships across molecular layers [12] |

| Data Heterogeneity | Technical and biological variation across cohorts [6] | Different omics modalities with distinct distributions [6] |

| Complexity | Cohort coordination, data harmonization [13] | Computational integration of diverse data types [12] |

| Typical Methods | Meta-analysis, cross-study validation [10] | Multi-omics factor analysis, similarity network fusion [12] |

What are the main technical challenges researchers face with each integration type?

Horizontal Integration Challenges:

- Data harmonization complexity: Different cohorts often use varied data capture methods, representations, and documentation standards, requiring extensive manual alignment of equivalent variables across studies [7].

- Administrative hurdles: Multi-cohort projects involve complicated management with many administrative obstacles, including obtaining relevant permits and ethics approvals from multiple governing bodies [13].

- Cohort heterogeneity: Different cohorts have specific purposes, focus areas, policies, and established methods of managing, collecting, and sharing data [13].

Vertical Integration Challenges:

- Data heterogeneity: Integrating completely different data distributions and types that require unique scaling, normalization, and transformation [6].

- High-dimension low sample size (HDLSS): Variables significantly outnumber samples, causing machine learning algorithms to overfit and decrease generalizability [6].

- Missing values: Omics datasets often contain missing values that hamper downstream integrative analyses, requiring additional imputation processes [6].

- Regulatory relationships: Effective integration must account for regulatory relationships between different omics layers to accurately reflect multidimensional data nature [6].

Integration Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

What methodologies are available for vertical integration of multi-omics data?

Five distinct integration strategies have been defined for vertical data integration in machine learning analysis [6]:

Table: Vertical Data Integration Strategies for Multi-Omics Analysis

| Strategy | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Concatenates all omics datasets into single matrix [6] | Simple implementation [6] | Creates complex, noisy, high-dimensional matrix; discounts dataset size differences [6] |

| Mixed Integration | Separately transforms each dataset then combines [6] | Reduces noise, dimensionality, and heterogeneities [6] | Requires careful transformation selection [6] |

| Intermediate Integration | Simultaneously integrates datasets to output multiple representations [6] | Creates common and omics-specific representations [6] | Requires robust pre-processing for data heterogeneity [6] |

| Late Integration | Analyzes each omics separately then combines predictions [6] | Circumvents challenges of assembling different datasets [6] | Does not capture inter-omics interactions [6] |

| Hierarchical Integration | Includes prior regulatory relationships between omics layers [6] | Embodies true trans-omics analysis intent [6] | Most methods focus on specific omics types, limiting generalizability [6] |

Can you provide a specific experimental workflow for integrative analysis?

The miodin R package provides a streamlined workflow-based syntax for multi-omics data analysis that can be adapted for both horizontal and vertical integration [12]. Below is a generalized workflow diagram for integrative analysis:

Detailed Workflow Steps:

Study Design Declaration: Use expressive vocabulary to declare all study design information, including samples, assays, experimental variables, sample groups, and statistical comparisons of interest [12]. The

MiodinStudyclass facilitates this through helper functions likestudySamplingPoints,studyFactor,studyGroup, andstudyContrast[12].Data Import and Validation: Import multi-omics data from different modalities (transcriptomics, genomics, epigenomics, proteomics) and experimental techniques (microarrays, sequencing, mass spectrometry) [12]. Automatically validate sample and assay tables against the declared study design to detect potential clerical errors [12].

Data Pre-processing: Address dataset-specific requirements including missing value imputation, normalization, scaling, and transformation to account for technical variations across platforms and batches [6].

Quality Control: Perform modality-specific quality control checks to identify outliers, technical artifacts, and data quality issues that might affect downstream integration and analysis.

Data Integration: Apply appropriate integration strategies (early, mixed, intermediate, late, or hierarchical) based on the research question and data characteristics [6]. Methods like Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA), similarity network fusion, or penalized clustering can be employed [12].

Statistical Analysis: Conduct both unsupervised (clustering, dimension reduction) and supervised (differential analysis, predictive modeling) analyses to extract biologically meaningful patterns [12] [11].

Biological Interpretation: Interpret results in context of existing biological knowledge, pathways, and regulatory networks to generate actionable insights into health and disease mechanisms [12].

Troubleshooting Common Integration Problems

How can researchers address missing data in multi-omics datasets?

Missing values are a common challenge in omics datasets that can hamper downstream integrative analyses [6]. Implementation strategies include:

- Imputation methods: Apply appropriate imputation techniques (mean/mode, k-nearest neighbors, matrix completion) to infer missing values before statistical analysis [6].

- Missing data mechanisms: Assess whether data is missing completely at random (MCAR), missing at random (MAR), or missing not at random (MNAR) to select appropriate handling methods.

- Algorithm selection: Choose integration methods that can handle missing data natively, such as MOFA, which can accommodate missing values across different omics modalities [12].

What strategies help manage the high-dimension low sample size (HDLSS) problem?

When variables significantly outnumber samples, machine learning algorithms tend to overfit, decreasing generalizability to new data [6]. Addressing strategies include:

- Dimension reduction: Apply principal component analysis, sparse PCA, or other dimension reduction techniques to reduce variable space while preserving biological signal [10].

- Feature selection: Use prior biological knowledge to prescreen genes or features [10]. For mental disorders analysis, focusing on relevant signaling pathways (ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, tryptophan metabolism, neurotrophin signaling) has proven effective [10].

- Regularization methods: Employ penalized regression and regularization techniques (lasso, ridge, elastic net) that constrain model complexity to prevent overfitting [10].

How can researchers effectively coordinate multi-cohort studies?

Multi-cohort projects present significant administrative and coordination challenges [13]. The PGX-link project demonstrated a 6-step approach:

Key coordination strategies:

- Early engagement: Involve cohort collaborators during grant writing, not after funding approval, to ensure scientific questions are feasible and clearly defined [13].

- Unified protocols: Establish common data standards, collection methods, and sharing policies across cohorts to facilitate interoperability [13] [7].

- Realistic timelines: Allocate sufficient time (potentially up to one year) for the preparation phase involving ethics approvals, scientific board reviews, and administrative setup [13].

- Clear communication channels: Establish regular communication protocols between cohort representatives to address challenges and maintain project momentum [13].

What software tools are available for integrative multi-omics analysis?

Table: Key Software Tools for Multi-Omics Data Integration

| Tool/Platform | Functionality | Integration Type | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| miodin R package [12] | Workflow-based multi-omics analysis | Vertical & Horizontal | Streamlined syntax, study design vocabulary, Bioconductor interoperability |

| MOFA [12] | Multi-Omics Factor Analysis | Vertical | Unsupervised integration, handles missing data, generalization of PCA |

| mixOmics [12] | Multivariate analysis | Vertical | PLS, CCA, generalization to multi-block data |

| Similarity Network Fusion [12] | Patient similarity networks | Vertical | Constructs fused multi-omics patient networks for clustering |

| MindWalk HYFT [6] | Biological data tokenization | Both | One-click normalization using HYFT framework |

What analytical techniques support horizontal integration of related disorders?

Horizontal integration of related mental disorders (e.g., bipolar disorder and schizophrenia) employs advanced statistical techniques [10]:

- Sparse principal component analysis: Identifies latent components that explain covariation patterns across disorders while selecting relevant features [10].

- Penalized regression methods: Incorporates regularization to identify robust biomarkers and patterns that generalize across related conditions [10].

- Pathway-based prescreening: Focuses analysis on biologically relevant signaling pathways (ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, tryptophan metabolism, neurotrophin signaling) to improve reliability and reduce computational cost when sample size is limited [10].

The experimental protocol for such analysis involves:

- Data acquisition from repositories like Stanley Medical Research Institute Online Genomics Database

- Prescreening of genes based on prior biological knowledge from KEGG pathways

- Data matching across disorders and omics modalities

- Application of sparse modeling and regularization techniques

- Validation of findings through resampling and biological interpretation [10]

Implementation FAQs

When should researchers choose horizontal versus vertical integration?

Choose horizontal integration when:

- Your research question requires larger sample sizes than a single cohort can provide [13]

- You need to validate findings across diverse populations or study designs [10]

- You are investigating related disorders or conditions with potential shared mechanisms [10]

Choose vertical integration when:

- You want to understand regulatory relationships across different molecular layers [12] [11]

- Your research focuses on complex mechanisms that span multiple biological levels [12]

- You need to identify biomarkers or signatures that incorporate multiple types of omic measurements [11]

How can researchers assess the quality of integrated analysis results?

Quality assessment strategies include:

- Biological validation: Verify that findings align with established biological knowledge and pathways [10]

- Method consistency: Compare results across different integration methods and parameters to identify robust patterns [6]

- Predictive performance: Evaluate whether integrated models improve prediction accuracy compared to single-omics approaches [11]

- Reproducibility: Ensure analyses are reproducible through workflow tools like Nextflow and container technology like Docker [12]

What standards facilitate more effective data integration?

Implementation of standards is crucial for reducing integration challenges:

- Data standards: Use common data elements, ontologies, and formats during data collection to facilitate future integration [7]

- Metadata documentation: Comprehensively document sample processing, experimental conditions, and data transformations [7]

- Sharing policies: Establish clear data sharing agreements and access policies during project initiation [13]

- Workflow transparency: Use tools that promote transparent data analysis and reduce technical expertise requirements [12]

FAQs on Data Heterogeneity

What are the main types of heterogeneity in multi-database studies? In multi-database studies, statistical heterogeneity arises from two primary sources: methodological diversity and true clinical variation. Methodological diversity includes differences in study design, database selection, variable measurement, and analysis methods, which can introduce varying degrees of bias to a study's internal validity. In contrast, true clinical variation reflects genuine differences in population characteristics and healthcare system features across different countries or settings, meaning the exposure-outcome association truly differs between populations [14].

How can I systematically investigate sources of heterogeneity in my study? A structured framework can be used to explore heterogeneity systematically [14]:

- Conceptualize the Heterogeneity: Distinguish whether observed differences are due to methodological diversity or true clinical variation.

- Explore Methodological Diversity: Use a checklist to compare differences in eligibility criteria, database structures, coding practices, confounder adjustment, and outcome ascertainment across study sites.

- Generate Hypotheses on True Variation: After accounting for methodological differences, remaining heterogeneity may be attributed to genuine variations in patient populations, clinical practices, or healthcare systems.

What is an example of how data source structure creates heterogeneity? The intended purpose and structure of a database directly influence the data it contains and can introduce significant heterogeneity [15]:

- Spontaneous Reporting Systems (e.g., FAERS): Rely on voluntary reports, which can lead to underreporting or overreporting of specific events, influenced by factors like media attention or how long a drug has been on the market.

- Electronic Health Records (EHRs): Designed for clinical care, not research. Data can be incomplete due to patients moving between health systems, and medication use (especially over-the-counter) is often inconsistently documented.

- Claims Databases: Contain structured billing data across providers but often lose patients to follow-up when they change insurance providers.

The table below summarizes the impact of different database purposes and structures.

| Database Type | Primary Purpose | Key Structural Limitations Introducing Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous Reporting Systems (e.g., FAERS) | Collect voluntary adverse event reports | Underreporting/overreporting; reporting bias; variable data quality [15] |

| Electronic Health Records (EHR) | Patient care delivery & administration | Inconsistent medication/adherence data; loss to follow-up between systems; unstructured clinical notes [15] |

| Claims Data | Insurance & billing processing | Loss to follow-up with insurer changes; contains only coded billing information [15] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Data Heterogeneity

Challenge: Schema and format variations across data sources.

Different sources often use different schemas and formats, making it difficult to map fields consistently. For example, a field might be named user_id in one source and userId in another, or dates might be stored as strings in a CSV file but as datetime objects in a SQL database [16].

- Solution: Use automated ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) frameworks or schema mapping tools to transform data into a common structure. Implement careful manual oversight to handle edge cases and ensure alignment [16].

Challenge: Integrating data from disparate systems. Combining data from relational databases, NoSQL stores, and flat files introduces integration hurdles. For instance, merging relational customer data with semi-structured application logs requires resolving different data models. Differences in time zones or date formats further complicate this process [16].

- Solution: Develop robust transformation logic that accounts for discrepancies like time zones and units. For real-time data integration, implement buffering or windowing strategies to align streaming data with batch reports [16].

Challenge: Varying data quality and consistency. Heterogeneous sources often have different data quality standards, leading to missing values, duplicates, or conflicting entries (e.g., a patient's age differing between sources) [16].

- Solution: Establish validation pipelines with defined rules for anomaly detection. For regulated data, incorporate anonymization or filtering steps to comply with standards like HIPAA or GDPR during the extraction process [16].

FAQs on Missing Data

What are the different mechanisms of missing data? Missing data can be categorized into three mechanisms [17]:

- Missing Completely at Random (MCAR): The probability of data being missing is unrelated to any observed or unobserved variables.

- Missing at Random (MAR): The probability of data being missing may depend on observed variables but not on the unobserved missing data itself.

- Missing Not at Random (MNAR): The probability of data being missing depends on the unobserved missing values themselves.

When is a complete-case analysis valid? A complete-case analysis (excluding subjects with any missing data) can be valid only when the data is Missing Completely at Random (MCAR). In some specific situations, it may also be valid for data that is Missing at Random (MAR), but in most real-world research scenarios, this approach leads to biased estimates and reduced statistical power [17]. Its use should be justified with great caution.

What is the recommended approach for handling missing data? Multiple Imputation (MI) is a widely recommended and robust approach for handling missing data, particularly when the Missing at Random (MAR) assumption is reasonable. With MI, multiple plausible values are imputed for each missing datum, creating several complete datasets. The desired statistical analysis is performed on each dataset, and the results are pooled, accounting for the uncertainty introduced by the imputation process [18] [19]. It is highly advised over single imputation methods like mean imputation [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Missing Data with Multiple Imputation

Protocol: Implementing Multiple Imputation This protocol outlines the key steps for performing Multiple Imputation, using the example of developing a model to predict 1-year mortality in patients hospitalized with heart failure [18] [19].

- Step 1: Develop the Imputation Model. Decide on the variables to include in the imputation model. It is good practice to include all variables that will be used in the final analysis, as well as auxiliary variables that are related to the missingness or the missing values themselves [18].

- Step 2: Create Multiple Imputed Datasets. Generate

Mcompleted datasets (common choices forMrange from 5 to 20, or higher depending on the fraction of missing information). This reflects the uncertainty about the imputed values [18] [19]. - Step 3: Perform Statistical Analysis. Run the same statistical model (e.g., a logistic regression for 1-year mortality) separately on each of the

Mimputed datasets [18]. - Step 4: Pool the Results. Combine the parameter estimates (e.g., regression coefficients) and their standard errors from the

Manalyses into a single set of results using Rubin's rules. These rules account for both the within-imputation variance and the between-imputation variance, producing valid confidence intervals [18] [19].

FAQs on High-Dimension Low Sample Size (HDLSS)

What defines an HDLSS problem?

HDLSS, or "High-Dimension Low Sample Size," refers to datasets where the number of features or variables (p) is vastly larger than the number of available samples or observations (n). This imbalance is common in fields like genomics, proteomics, and medical imaging, where a study might involve expression levels of tens of thousands of genes from only a few dozen patients [20].

What are the primary challenges when working with HDLSS data? HDLSS data presents several key challenges [20]:

- Overfitting: Models can fit the training data perfectly but fail to generalize to new, unseen data because they learn noise and spurious patterns specific to the small sample.

- Curse of Dimensionality: In high-dimensional spaces, traditional distance-based measures become less meaningful, and data points can appear equally distant from each other, weakening algorithms that rely on these measures.

- Feature Selection and Statistical Significance: It is difficult to identify which features are truly relevant, and achieving statistical significance is harder due to the small sample size relative to the vast number of tests performed.

Are there specific machine learning techniques for HDLSS classification? Yes, specialized methods have been developed. For example, one state-of-the-art approach involves using a Random Forest Kernel with Support Vector Machines (RFSVM). This method uses the similarity measure learned by a Random Forest as a precomputed kernel for an SVM. This learned kernel is particularly suited for capturing complex relationships in HDLSS data and has been shown to outperform other methods on many HDLSS problems [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: The HDLSS Problem

Challenge: Model overfitting and poor generalizability. With thousands of variables and only a small sample, models are prone to overfitting [20].

- Solution: Employ regularization techniques like Lasso (L1) or Ridge (L2) regression, which penalize model complexity. Dimensionality reduction methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can project data into a lower-dimensional space. Cross-validation and bootstrapping are essential for validating model performance and assessing generalizability [20].

Challenge: Identifying meaningful features among thousands. Many variables in an HDLSS dataset may be irrelevant or redundant [20].

- Solution: Use feature selection algorithms to narrow down the variable set. In genomics, this can involve focusing on biologically relevant pathways. Regularized models like Lasso inherently perform feature selection by driving some coefficients to zero. Combining domain knowledge with algorithmic selection is often the most effective strategy [20].

Strategy: Improve generalizability by embracing cohort heterogeneity. Models trained on a single, homogeneous cohort may not perform well in new settings due to population or operational heterogeneity [22].

- Solution: Train models on data from multiple cohorts. While this introduces more heterogeneity into the training data, it dilutes cohort-specific patterns and helps the model learn more general, disease-specific predictors. This approach has been shown to produce models with better external performance than models trained on the same amount of data from a single cohort [22]. Note that model calibration should be carefully checked after training on mixed cohorts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Method | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Imputation | A statistical technique that handles missing data by creating multiple plausible datasets, analyzing them separately, and pooling results. | Handling missing data in clinical research datasets under the MAR assumption [18] [17]. |

| Regularization (L1/Lasso, L2/Ridge) | Prevents overfitting in high-dimensional models by adding a penalty term to the model's loss function, shrinking coefficient estimates. | Building predictive models with HDLSS data to improve generalizability [20]. |

| Dimensionality Reduction (PCA, t-SNE) | Reduces the number of random variables under consideration by obtaining a set of principal components or low-dimensional embeddings. | Visualizing and pre-processing HDLSS data (e.g., genomic, proteomic) for analysis [20]. |

| Random Forest Kernel (RFSVM) | A learned similarity measure from a Random Forest used as a kernel in a Support Vector Machine, designed for complex, high-dimensional data. | HDLSS classification tasks where traditional algorithms fail [21]. |

| Heterogeneity Assessment Checklist | A systematic tool for identifying differences in study design, data source, and analysis that may contribute to variation in results. | Planning and interpreting multi-database or multi-cohort studies [14]. |

| Cross-Validation / Bootstrapping | Resampling techniques used to assess how the results of a statistical model will generalize to an independent dataset and to estimate its accuracy. | Model validation and selection, especially in HDLSS contexts to avoid overfitting [20]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

What are variable encoding differences and how do they disrupt my multi-cohort analysis?

Variable encoding differences occur when the same conceptual data is represented using different formats, structures, or coding schemes across various cohort studies. This creates significant semantic barriers that can disrupt integrated analysis.

Problem Example: In a harmonization project between the LIFE (Jamaica) and CAP3 (United States) cohorts, researchers encountered variables collecting the same data but with different coding formats [23]. For instance, a "smoking status" variable might be coded as:

- Study A:

0=Non-smoker,1=Current smoker,2=Former smoker - Study B:

1=Never,2=Past,3=Present

Impact: If merged directly, these encoding differences would misclassify participants, leading to incorrect prevalence estimates and flawed statistical conclusions about smoking-related health risks.

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Create a Data Dictionary Map: Document all variable encodings from each source study.

- Define a Common Model: Establish a unified coding scheme for the integrated dataset.

- Develop a Mapping Table: Implement a transformation logic to convert all source values to the common model. The LIFE-CAP3 project used a user-defined mapping table for this recoding process [23].

Table: Example Mapping Table for Smoking Status Variable

| Source Study | Source Code | Source Label | Target Code | Target Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study A | 0 | Non-smoker | 1 | Never |

| Study B | 1 | Never | 1 | Never |

| Study A | 2 | Former smoker | 2 | Past |

| Study B | 2 | Past | 2 | Past |

| Study A | 1 | Current smoker | 3 | Present |

| Study B | 3 | Present | 3 | Present |

What is schema drift and how can I prevent it from invalidating my research results?

Schema drift refers to unexpected or unintentional changes to the structure of a database—such as adding, removing, or modifying tables, columns, or data types—that create inconsistencies across different environments or over time [24].

Problem Example: A new column like "Patient Type" is added to a production database to support a new business need but is not replicated in the development or testing environments. Applications or researchers expecting the old schema structure will encounter failures or corrupted data [24].

Impact: Schema drift can lead to data integrity issues, application downtime, increased maintenance costs, and compliance or security concerns [24].

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Detection: Use automated schema monitoring and comparison tools to track changes and alert teams to unexpected modifications [24].

- Version Control: Implement version control for database schemas, similar to software code, to track and synchronize changes across environments [24].

- Automated Validation: Incorporate schema validation into continuous integration/continuous delivery (CI/CD) pipelines to detect drift early [24].

- Regular Audits: Perform routine audits of database schemas to identify and address drift before it causes operational problems [24].

Table: Common Causes and Impacts of Schema Drift

| Cause of Schema Drift | Potential Impact on Research | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Evolving business requirements (e.g., new variables) | Incomplete data, failed analyses | Comprehensive documentation and communication |

| Multiple development teams working independently | Inconsistent data models, pipeline failures | Version control systems (e.g., Git) |

| Frequent updates to production databases | Mismatch between development and production data | Automated testing and CI/CD pipelines |

| Changes in external data sources or APIs (Source Schema Drift) [24] | Disrupted data pipelines, analytics errors | Proactive monitoring of source systems |

What is the step-by-step methodology for prospectively harmonizing active cohort studies?

Prospective harmonization occurs before or during data collection and is a powerful strategy for reducing future integration costs. The established ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) process provides a structured framework [23].

Experimental Protocol: The LIFE and CAP3 harmonization project followed this methodology [23]:

Extract

- Objective: Collect raw data from source cohort studies.

- Action: Use secure Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) to routinely download data from each study's data management platform (e.g., REDCap). Automate this process with server-side jobs.

Transform

- Objective: Convert and map source variables to a common, unified structure.

- Action:

- Variable Mapping: Identify shared data elements across studies. Create a mapping table that defines the relationship between each source variable and its corresponding target variable in the integrated dataset [23].

- Recoding: Apply logic to handle different data types and coding schemes, using the mapping table to recode values for consistency [23].

- Data Cleaning: Address missing values and ensure data quality.

Load

- Objective: Insert the transformed data into a single, integrated database.

- Action: Upload the harmonized data to a central project. Implement automated, weekly cycles to keep the integrated database synchronized with source studies [23].

Quality Assurance: Conduct routine quality checks. Pull a random sample from the integrated database and cross-check it against the source data. Correct any errors at the source to maintain integrity [23].

How do I manage the integration of highly heterogeneous data (structured, semi-structured, unstructured)?

Integrating heterogeneous data—which includes structured tables, semi-structured JSON/XML, and unstructured text or images—requires a robust architectural approach to handle varying formats, structures, and semantics [25].

Problem Example: A multi-omics study might need to combine structured clinical data (e.g., from a REDCap database), semi-structured genomic annotations (e.g., in JSON format), and unstructured text from pathology reports [6].

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Unified Ingestion Layer: Use tools that can collect, process, and deliver diverse data types from various sources, supporting both batch and real-time ingestion patterns [25].

- Transformation and Normalization Engines: Apply specialized processing for different data types. This includes scaling, normalization, encoding categorical data, and preprocessing text or images to make them suitable for analysis [25].

- Centralized Metadata Management: Produce standardized metadata from all sources. Use common standards and tools to create an integrated, accessible metadata system that improves data governance and simplifies querying [25].

- Unified Storage Abstraction: Implement a software layer that provides a standard interface for interacting with diverse underlying storage systems, simplifying development and enabling centralized management [25].

Table: Components of a Heterogeneous Data Architecture

| Architectural Layer | Function | Example Tools/Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Ingestion Layer | Collects mixed-format data from diverse sources | Hybrid patterns (batch/real-time), Schema-on-read |

| Transformation Engine | Prepares raw data for analysis; handles scaling, encoding, etc. | Min-max scaling, Z-score standardization, NLP for text |

| Metadata Management | Creates standardized, integrated metadata for governance | Metadata management tools, Semantic annotations (DCAT-AP, ISO19115) |

| Storage Abstraction | Provides a unified interface to access different storage systems | Data lake architectures, Pluggable frameworks |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Heterogeneous Data Integration

| Tool / Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| REDCap API [23] | Enables secure, automated data extraction and exchange from the REDCap platform. | Extracting data from multiple clinical cohort studies for central pooling. |

| Schema Migration Tools (e.g., Flyway, Liquibase) [24] | Automate and version-control the application of schema changes across environments. | Preventing schema drift by ensuring consistent database structures in development, testing, and production. |

| Mapping Tables | User-defined tables that define the logic for recoding variables from a source format to a target format [23]. | Resolving variable encoding differences during the "Transform" stage of the ETL process. |

| Data Observability Platform (e.g., Acceldata) [24] | Monitors pipeline health, automatically detects schema changes, data quality errors, and data source changes. | Providing end-to-end visibility into data health, crucial for managing complex, multi-source pipelines. |

| HYFTs Framework (MindWalk Platform) [6] | Tokenizes all biological data (sequences, text) into a common set of building blocks ("HYFTs"). | Enabling one-click normalization and integration of highly heterogeneous multi-omics and non-omics data. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical data privacy regulations affecting multi-cohort studies in 2025? A complex maze of global regulations now exists. The EU's GDPR remains foundational, while in the US, researchers must comply with a patchwork of laws including the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), Texas Data Privacy and Security Act (TDPSA), and the health-specific HIPAA [26]. Brazil's LGPD and India's Personal Data Protection Bill also impact international studies. Non-compliance can lead to fines and loss of consumer trust, with data breach costs averaging $10.22 million in the US as of 2025 [27].

Q2: How can we handle Data Subject Access Requests (DSARs) efficiently across pooled datasets? Regulations like GDPR and CCPA give individuals rights to access, rectify, or erase their data. To manage these requests, you need deep visibility into your data landscape. Implement processes and tools for comprehensive data mapping and inventory to quickly identify, retrieve, and modify personal data across all source systems and storage locations [26]. A centralized data catalog can be instrumental in streamlining the DSAR process.

Q3: Our data sources have different variable encodings for the same concept. How can we harmonize them? This is a common challenge in heterogeneous data integration. One robust solution is to use an automated harmonization algorithm like SONAR (Semantic and Distribution-Based Harmonization). This method uses machine learning to create embedding vectors for each variable by learning from both variable descriptions (semantic learning) and the underlying participant data (distribution learning), achieving accurate concept-level matching across cohorts [28].

Q4: What is the best way to structure a data integration workflow for active, ongoing cohort studies? A prospective harmonization approach, using a structured ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) process, is highly effective. This involves mapping variables across projects before or during data collection. A proven method is to use a platform like REDCap, which supports APIs for automated data pooling. Researchers create a mapping table to direct the integration, and a custom application can routinely download and upload data from all studies into a single, integrated project on a scheduled basis [23].

Q5: How can we prevent costly mistakes when scaling our data integration architecture? Avoid three common strategic errors: 1) Betting everything on cloud-only tools in a hybrid reality, which can create compliance risks and visibility gaps; 2) Treating scale and performance as future problems, which causes latency and failed data jobs under AI workloads; and 3) Locking your future to today's architecture with vendor-specific APIs, which leads to costly "migration tax" later. The solution is to plan for hybrid, elastic, and portable data integration from the start [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Data Silos and Incompatible Systems

Problem: Data is trapped in a patchwork of legacy systems, modern cloud tools, and niche applications, preventing a unified view.

Solution:

- Action 1: Adopt a flexible integration platform with pre-built connectors for common applications (e.g., CRMs, ERPs) to reduce integration time [30].

- Action 2: Implement a data fabric architecture, which acts as a unified framework for managing and integrating different data types across various systems, simplifying access and sharing [30].

- Action 3: For semantic inconsistencies, use an ontology-based data integration approach. This provides a joint knowledge base that acts as a common reference point, solving heterogeneity at the semantic level [31].

Issue 2: Poor Data Quality and Integrity

Problem: Integrated data is inconsistent, inaccurate, or contains duplicates, undermining trust in analytics.

Solution:

- Action 1: Use AI-driven validation and cleansing tools to automate data quality assurance. These tools can be built into your integration platform to ensure integrity throughout the data pipeline [30].

- Action 2: Implement a Data Quality Management System to proactively validate data at the point of entry, preventing bad data from contaminating systems [32].

- Action 3: Track data lineage to trace where duplicates or errors originate. Encourage a culture of collaboration where teams share updates openly to prevent redundant records [32].

Issue 3: Real-Time Data Integration Failures

Problem: Batch processing is too slow for time-sensitive decisions in fields like finance or healthcare, leading to missed opportunities.

Solution:

- Action 1: Build event-driven architectures that trigger integration workflows the moment new data arrives [32].

- Action 2: Use stream processing technologies like Apache Kafka for real-time data handling and continuous ingestion [32].

- Action 3: Ensure your integration platform supports real-time data streaming and synchronization to keep critical systems updated instantly [30].

Issue 4: Managing Data Privacy and Security During Integration

Problem: Sensitive data is exposed during integration, creating compliance risks and vulnerability to breaches.

Solution:

- Action 1: Embed compliance protocols directly into data integration workflows. This includes using encryption (for data in transit and at rest), role-based access controls, and maintaining detailed audit trails [30].

- Action 2: Develop a Data Compliance Framework with core components like data mapping/inventory, risk management tools, and monitoring processes. This framework ensures personal data is handled responsibly per legal requirements [26].

- Action 3: For AI-driven projects, prioritize transparency in how models use personal data and implement safeguards against bias to prepare for upcoming AI-specific regulations [26].

Table 1: Key Global Data Privacy Regulations (2025)

| Regulation/Region | Scope & Key Requirements | Potential Fines & Penalties |

|---|---|---|

| GDPR (EU) | Protects personal data of EU citizens; mandates rights to access, erasure, and data portability. | Up to €20 million or 4% of global annual turnover [26]. |

| US State Laws (CCPA, TDPSA, etc.) | A patchwork of laws granting consumers rights over their personal data; requirements vary by state. | Significant financial penalties; brand damage and loss of customer trust [26]. |

| HIPAA (US) | Safeguards protected health information (PHI) for covered entities and business associates. | Civil penalties up to $1.5 million per violation per year [26]. |

Table 2: Data Integration Strategies for Multi-Cohort Studies

| Integration Strategy | Description | Best Used For |

|---|---|---|

| Prospective Harmonization | Variables are mapped and standardized before or during data collection [23]. | Active, ongoing cohort studies where data collection instruments can be aligned. |

| Retrospective Harmonization | Data is integrated after collection from completed or independent studies [23]. | Leveraging existing datasets where the study design cannot be changed. |

| ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) | Data is extracted from sources, transformed into a unified format, and loaded into a target system [31]. | Creating a physically integrated, analysis-ready dataset (e.g., a data warehouse). |

| Virtual/Federated Integration | A mediator layer allows querying of disparate sources without physical data consolidation [31]. | Scenarios requiring real-time data from source systems with minimal storage costs. |

| SONAR (Automated Harmonization) | An ensemble ML method that uses semantic and distribution learning to match variables across cohorts [28]. | Large-scale studies with numerous variables where manual curation is infeasible. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Prospective Data Harmonization for Active Cohorts

This protocol is based on a successful implementation integrating cohort studies in Jamaica and the United States [23].

- Variable Mapping: Hold working group sessions with epidemiologists, domain experts, and research assistants to identify shared data elements. Group items into domains (e.g., demographics, medical history).

- Create Mapping Table: Develop a mapping table (e.g., within a REDCap project) that links source variables from each cohort to a common destination variable. Include metadata for recoding values if data types differ.

- Automate ETL Process: Develop a custom application (e.g., in Java) that uses APIs (like REDCap's API) to routinely download data from all cohort studies.

- Transform and Load: The application uses the mapping table to recode and transform the data, then uploads it to a central, integrated project on a scheduled basis (e.g., weekly).

- Quality Assurance: Implement routine checks. Pull a random sample from the integrated database weekly and cross-check it against the source data. Correct any errors at the source.

Protocol 2: Automated Variable Harmonization Using SONAR

This protocol uses the SONAR method for accurate variable matching within and between cohort studies [28].

- Data Extraction: Gather variable documentation (name, description, accession ID) and patient-level data from all cohort studies (e.g., from dbGaP).

- Preprocessing: Filter for the data type of interest (e.g., continuous variables). Remove temporal information (e.g., "at baseline," "visit 2") from variable descriptions to focus on the core concept.

- Model Training: Apply the SONAR algorithm, which learns an embedding vector for each variable by combining:

- Semantic Learning: Infers meaning from the variable description strings.

- Distribution Learning: Analyzes the underlying patient-level data patterns for each variable.

- Similarity Scoring: Calculate pairwise cosine similarity scores between all variable embeddings to identify matches.

- Validation: Evaluate harmonization performance against a manually curated gold standard using metrics like area under the curve (AUC) and top-k accuracy.

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Prospective Harmonization & ETL Workflow

Prospective Harmonization ETL Flow

Diagram 2: Data Privacy & Security Compliance Framework

Data Privacy Compliance Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Solutions for Data Integration and Privacy

| Tool / Solution | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) | A secure, HIPAA-compliant web application for building and managing data collection surveys and databases; its APIs enable automated data pooling for harmonization [23]. |

| Data Catalog | A centralized tool that provides a view of all data sources, storage locations, and lineage. Essential for tagging, mapping, and governing data for specific regulatory requirements (e.g., DSARs) [26]. |

| Data Fabric Architecture | A unified framework that connects structured and unstructured data from diverse sources, simplifying access, sharing, and management of complex datasets across the organization [30]. |

| Encryption & Role-Based Access Controls (RBAC) | Security measures to protect data in transit and at rest (encryption) and to restrict data access to authorized users based on their role (RBAC) [32] [30]. |

| AI-Driven Data Validation & Cleansing Tools | Automated tools that identify and correct data quality issues (e.g., duplicates, inaccuracies) within integration pipelines, ensuring the reliability of pooled data [30]. |

| SONAR Algorithm | An ensemble machine learning method for automated variable harmonization across cohorts, using both semantic (descriptions) and distribution (patient data) learning [28]. |

Building Robust Integration Pipelines: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

Troubleshooting Guide: Common ETL Harmonization Challenges

Data Mapping and Variable Alignment

| Challenge | Symptom | Solution | Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic Heterogeneity | Same variable names measure different concepts (e.g., different age ranges for "young adults") [33] | Create detailed data dictionaries; implement crosswalk tables for value recoding [23] | Prospective: Establish common ontologies during study design [34] |

| Structural Incompatibility | Dataset formats conflict (event data vs. panel data); routing errors during integration [33] | Use intermediate transformation layer; implement syntactic validation checks [35] | Adopt standardized data collection platforms like REDCap across studies [23] |

| Variable Coverage Gaps | Incomplete mapping—only 74% of forms achieve >50% variable harmonization [34] | Prioritize core variable sets; accept partial integration where appropriate [7] | Prospective harmonization of core instruments before data collection [34] |

Technical Implementation and Quality Assurance

| Challenge | Symptom | Solution | Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missing Data Patterns | Systematic missingness in key variables hampers pooled analysis [6] | Implement multiple imputation techniques; document missingness patterns [36] | Standardize data capture procedures; implement real-time validation [23] |

| High-Dimensionality | Variables significantly outnumber samples (HDLSS problem); algorithm overfitting [6] | Apply dimensionality reduction; use mixed integration approaches [6] | Plan variable selection strategically; avoid unnecessary data collection [34] |

| Cohort Heterogeneity | Statistical power diminished due to clinical/methodological differences [7] | Apply covariate adjustment; stratified analysis; random effects models [7] | Characterize cohort differences early; document protocols thoroughly [13] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between prospective and retrospective harmonization, and when should I choose each approach?

A: Prospective harmonization occurs before or during data collection, with studies designed specifically for integration, while retrospective harmonization occurs after data collection is complete, requiring alignment of existing datasets [36].

- Choose prospective harmonization when designing new multi-cohort studies: it achieves higher variable coverage (74% of forms harmonized >50% of variables in the LIFE/CAP3 integration) [34] and reduces costs long-term.

- Choose retrospective harmonization when working with legacy datasets: it enables resource leveraging from completed studies but requires manual variable alignment and complex mapping [7].

Q2: Our multi-cohort project is experiencing significant delays in ethics approvals and data sharing agreements. What strategies can help accelerate this process?

A: Multi-cohort projects typically require ≥1 year for preparation phase alone [13]. Effective strategies include:

- Establish communication channels early with all cohort governance bodies (scientific boards, foundation boards) [13]

- Develop a unified protocol that addresses all cohorts' requirements simultaneously rather than sequentially

- Leverage existing cohort relationships - cohorts with prior collaboration history experience fewer administrative hurdles [13]

- Engage ethics committees early with clear documentation on data protection measures (HIPAA/GDPR compliance through platforms like REDCap) [23]

Q3: What are the most effective ETL tools for cohort harmonization, particularly for research teams with limited programming expertise?

A: Tool selection depends on technical capacity and harmonization scope:

- REDCap with APIs provides secure, web-based data collection with built-in harmonization features, ideal for multi-site studies with varying technical expertise [23]

- BIcenter offers visual, drag-and-drop ETL interfaces that reduce dependency on programming support, successfully applied to harmonize 6,669 Alzheimer's disease subjects [35]

- Custom Python implementations (like CMToolkit) provide flexibility for complex transformations but require more technical resources [37]

- OHDSI Common Data Model enables standardized schema migration for observational data, though it requires initial technical investment [37]

Q4: How can we effectively handle the "high-dimension, low sample size" (HDLSS) problem in multi-omics data integration?

A: The HDLSS problem, where variables drastically outnumber samples, causes machine learning algorithms to overfit [6]. Effective strategies include:

- Mixed Integration: Separately transform each omics dataset before combination, reducing noise and dimensionality [6]

- Early Integration: Concatenate datasets into a single matrix but apply rigorous variable selection to minimize dimensionality [6]

- Hierarchical Integration: Incorporate prior knowledge of regulatory relationships between omics layers to guide analysis [6]

- Feature Selection: Prioritize biologically relevant variables rather than attempting to integrate all available omics data [6]

Experimental Protocols: Successful Harmonization Methodologies

Protocol 1: Prospective ETL Harmonization for Active Cohorts

Based on the successful integration of LIFE (Jamaica) and CAP3 (Philadelphia) cohorts [34]:

Key Implementation Details:

- Variable Mapping Algorithm: Direct mapping for identical variables; user-defined mapping tables for differently coded variables [23]

- Technical Infrastructure: REDCap APIs with custom Java applications for automated weekly data pooling [23]

- Quality Assurance: Random sampling with cross-referencing against source data; error correction at source level [23]

- Coverage Validation: Quantitative assessment of variable completeness across all integrated forms [34]

Protocol 2: Retrospective Harmonization of Legacy Datasets

Based on the MASTERPLANS consortium experience with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus trials [7]:

Key Implementation Details:

- Manual Variable Alignment: Required when standards weren't implemented at source; matching equivalent patient variables across studies [7]

- Research-Driven Process: Focus on specific research questions to make harmonization feasible within realistic timelines [7]

- Flexible Approach: Accept inferential equivalence rather than insisting on identical measures [33]

- Systematic Preparation: Comprehensive data cleaning and organization before integration attempts [7]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

ETL Platforms and Data Integration Tools

| Tool | Function | Use Case | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| REDCap with APIs [23] | Secure data collection and harmonization platform | Multi-site cohort studies with varying technical capacity | HIPAA/GDPR compliant, role-based security, automated ETL capabilities |

| BIcenter | Visual ETL tool with drag-and-drop interface | Complex medical concept harmonization (e.g., Alzheimer's disease) | No programming expertise required, collaborative web platform [35] |

| CMToolkit (Python) [37] | Programmatic cohort harmonization | Large-scale data migration to common data models | OHDSI CDM support, open-source (MIT license) |

| OHDSI Common Data Model | Standardized schema for observational data | Integrating electronic health records with research data | Enables systematic analysis across disparate datasets [37] |

Integration Strategy Framework

| Strategy | Approach | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Concatenate all datasets into single matrix | Simple, quick implementation | Increases dimensionality, noisy, discounts data distribution differences [6] |

| Mixed Integration | Transform datasets separately before combination | Noisy, heterogeneous data | Requires careful transformation design [6] |

| Intermediate Integration | Simultaneous integration with multiple representations | Capturing common and dataset-specific variance | Requires robust pre-processing for heterogeneous data [6] |

| Late Integration | Analyze separately, combine final predictions | Preserving dataset integrity | Doesn't capture inter-dataset interactions [6] |

| Hierarchical Integration | Incorporate regulatory relationships between layers | Multi-omics data with known biological pathways | Less generalizable, nascent methodology [6] |

Key Lessons from Active Implementations

Prospective Harmonization Success Factors

The LIFE/CAP3 integration demonstrated that 74% of questionnaire forms can achieve >50% variable harmonization when studies implement prospective design [34]. Critical success factors included:

- Cross-disciplinary working groups during variable selection (epidemiologists, psychologists, laboratory scientists) [23]

- Leveraging existing platforms with built-in security compliance (REDCap with HIPAA/GDPR) [23]

- Automated ETL processes with weekly synchronization and quality checks [23]

Retrospective Harmonization Realities

The MASTERPLANS consortium experience with Lupus trials revealed that retrospective harmonization remains possible without source standards, but requires [7]:

- Substantial manual effort for variable alignment

- Focus on specific research questions to make the process manageable

- Flexibility in accepting inferentially equivalent rather than identical measures

- Systematic preparation and data cleaning before integration

Effective ETL processes for cohort harmonization—whether prospective or retrospective—require careful planning, appropriate tool selection, and acknowledgment that some challenges require pragmatic compromises rather than perfect solutions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is vertical integration in the context of multi-omics data? Vertical integration, or cross-omics integration, involves combining multiple types of omics data (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) collected from the same set of samples to gain a comprehensive understanding of biological systems and disease mechanisms [11] [38] [39].

2. What are the main challenges of heterogeneous data integration in multi-cohort studies? Key challenges include:

- High Dimensionality and Low Sample Size (HDLSS): Variables vastly outnumber samples, leading to a "lack of information" and risk of overfitting in machine learning models [11] [38] [6].

- Data Heterogeneity: Omics datasets differ in scale, distribution, and data type, making integration difficult [38] [6].

- Technical Noise and Batch Effects: Unwanted variations introduced across different platforms, labs, or batches can confound true biological signals [39].

- Missing Data: Omics datasets often contain missing values that can hamper downstream integrative analysis [38] [6].

3. How do I choose the right vertical integration strategy for my study? The choice depends on your research question and data structure. Early Integration is simple but struggles with highly dimensional data. Late Integration is flexible but may miss inter-omics interactions. Intermediate and Mixed Integration are powerful for capturing complex relationships but can be computationally intensive. Hierarchical Integration is ideal for leveraging known biological prior knowledge [38] [6].