Target Families in Chemogenomics: A 2025 Guide to Multi-Target Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemogenomics and its application to target families for researchers and drug development professionals.

Target Families in Chemogenomics: A 2025 Guide to Multi-Target Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemogenomics and its application to target families for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational concepts of protein families like kinases and GPCRs, details methodological advances in machine learning and library design, addresses key challenges in data quality and model interpretability, and examines validation frameworks through public-private partnerships and consortium data. The content synthesizes current trends to offer a practical guide for leveraging chemogenomic strategies to accelerate systematic drug discovery.

What Are Target Families? Defining the Chemogenomic Landscape

For decades, drug discovery operated under a reductionist paradigm famously described by the 'lock and key' model, where the goal was to identify a single selective drug ('key') for a single specific target ('lock') [1]. This 'one-drug-one-target' approach, motivated by a desire for specificity and minimal off-target effects, dominated pharmaceutical research and development. However, despite several successful applications, this strategy has proven insufficient for addressing complex diseases, often yielding compounds that show efficacy in vitro but lack clinical effectiveness in vivo [1]. The increasing costs of drug development, staggering attrition rates in clinical trials, and the fact that many drugs demonstrate limited effectiveness across patient populations—with some therapeutic areas like oncology showing as low as 25% patient response rates—have exposed critical flaws in this reductionist model [2].

The recognition of these limitations, coupled with advances in systems biology and the ever-growing understanding of biological complexity, has catalyzed a fundamental shift in pharmaceutical science. Instead of viewing biological systems as collections of isolated components, researchers now recognize that clinical effects often result from interactions of single or multiple drugs with multiple targets [1]. This understanding has given rise to systems pharmacology, an emerging discipline that integrates systems biology, computational modeling, and pharmacology to study drug action in the context of complex, interconnected biological networks [3] [4]. This paradigm shift moves beyond single-target modulation toward deliberately designing therapeutic interventions that engage multiple targets simultaneously, acknowledging the inherent polypharmacology of effective drugs and offering new hope for treating complex, multifactorial diseases [2].

The Theoretical Foundation: From Single-Target to Multi-Target Models

The Emergence of Polypharmacology and Network Medicine

The conceptual cornerstone of systems pharmacology is polypharmacology—the recognition that most small-molecule drugs interact with multiple biological targets, and that this multi-target activity often underlies their therapeutic efficacy [1]. Rather than representing undesirable 'promiscuity,' a growing body of evidence suggests that carefully engineered polypharmacology can yield superior therapeutic outcomes, particularly for complex diseases like cancer, Alzheimer's disease, and metabolic disorders, which involve dysregulation across multiple pathways and biological processes [2]. This represents a significant evolution in thinking: from seeking 'key' compounds that fit single-target 'locks' to identifying 'master key' compounds that favorably interact with multiple targets to produce desired clinical effects [1].

This multi-target perspective aligns with the principles of network medicine, which views diseases not as consequences of single gene defects but as perturbations within complex molecular networks [5] [4]. Within this framework, biological systems are represented as interconnected networks where nodes represent molecular entities (proteins, metabolites, DNA) and edges represent interactions or relationships between them. The topological analysis of these networks helps identify key targets whose modulation can restore the network to a healthy state, providing a rational basis for multi-target drug discovery [4]. Systems pharmacology leverages this network-centric view to understand how drug-induced perturbations propagate through biological systems, ultimately producing therapeutic and adverse effects [3].

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP): A Formal Framework

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) has emerged as a formal discipline that provides the mathematical and computational foundation for systems pharmacology. QSP is defined as the "quantitative analysis of the dynamic interactions between drug(s) and a biological system that aims to understand the behavior of the system as a whole" [6]. QSP models integrate diverse data types—from molecular interactions to clinical outcomes—to quantitatively simulate drug effects across multiple biological scales [5] [4].

QSP approaches typically share several defining features [6]:

- A coherent mathematical representation of key biological connections consistent with current knowledge

- Consideration of complex systems dynamics resulting from biological feedback, cross-talk, and redundancies

- Integration of diverse data types, biological knowledge, and hypotheses

- The ability to quantitatively explore and test hypotheses via biology-based simulation

- A representation of the pharmacology of therapeutic interventions or strategies

Table 1: Key Differences Between Traditional and Systems Pharmacology Approaches

| Feature | Traditional Pharmacology | Systems Pharmacology |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Single drug-target interactions | Network-level interactions and perturbations |

| Target Strategy | 'One-drug-one-target' | Deliberate multi-targeting ('master keys') |

| Modeling Approach | Reductionist | Holistic/integrative |

| Key Methods | Molecular docking, QSAR | QSP modeling, network analysis, chemogenomics |

| Data Utilization | Focused on specific targets | Integrates multi-omics and clinical data |

| Therapeutic Optimization | Maximizing selectivity | Balancing multi-target efficacy and safety |

Core Methodologies and Experimental Frameworks

Chemogenomics: Systematically Mapping Chemical-Biological Space

Chemogenomics represents a foundational methodology in systems pharmacology, aiming to systematically identify all possible ligands for all possible targets, thereby comprehensively mapping the interactions between chemical and biological spaces [1]. This approach leverages large-scale compound libraries annotated with biological activity data to establish relationships between chemical structures and their effects across multiple targets, facilitating the prediction of new drug-target interactions and potential off-target effects [7].

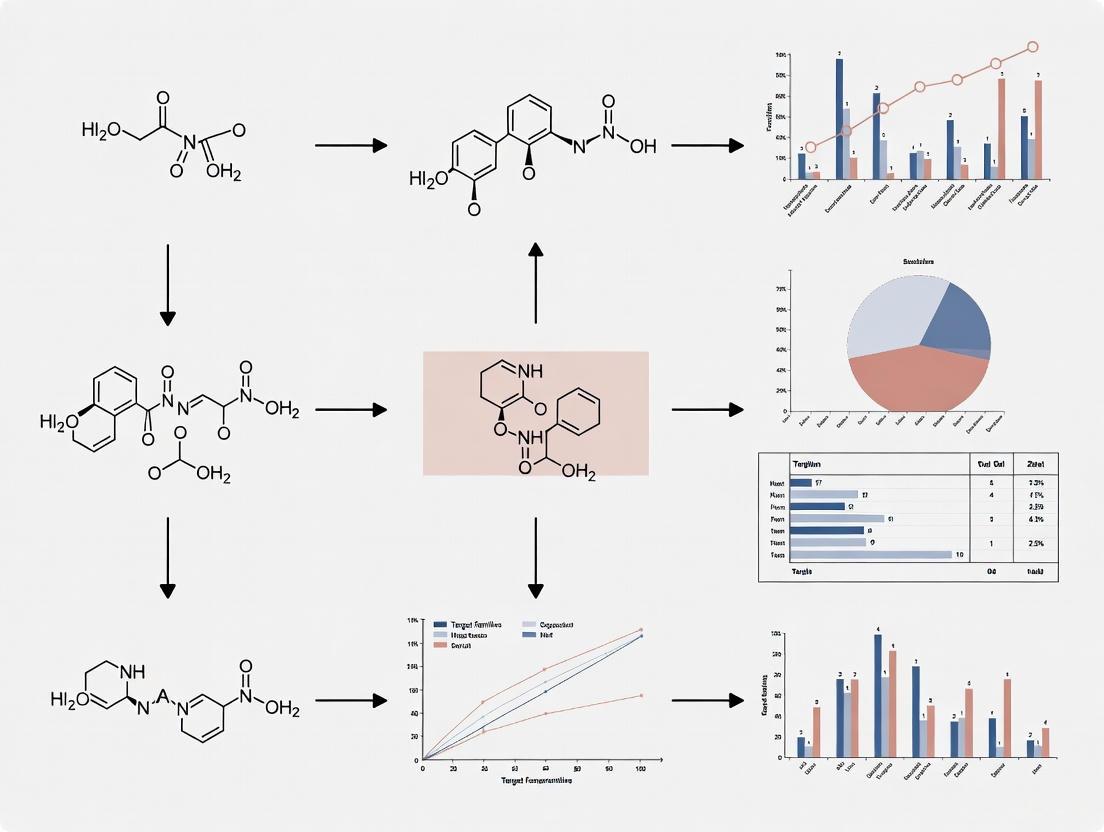

Major initiatives are advancing chemogenomics, including the EUbOPEN project (Enabling and Unlocking Biology in the OPEN), a public-private partnership that aims to create, distribute, and annotate the largest openly available set of high-quality chemical modulators for human proteins [8]. This project contributes to Target 2035, a global initiative seeking to identify pharmacological modulators for most human proteins by 2035. EUbOPEN focuses on four key areas: (1) developing chemogenomic library collections, (2) chemical probe discovery and technology development, (3) profiling bioactive compounds in patient-derived disease assays, and (4) collecting, storing, and disseminating project-wide data and reagents [8].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents in Systems Pharmacology

| Reagent Type | Description | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | Potent (≤100 nM), selective (≥30-fold), cell-active small molecules | Target validation and functional studies [8] |

| Chemogenomic (CG) Compounds | Compounds with well-characterized multi-target profiles | Systematic exploration of target space and pathway deconvolution [8] |

| Negative Control Compounds | Structurally similar but inactive analogs | Control for off-target effects in cellular assays [8] |

| Patient-Derived Cells | Primary cells from patients with specific diseases | More physiologically relevant compound profiling [8] |

Computational and Modeling Approaches

Computational methods form the backbone of modern systems pharmacology, enabling the integration and analysis of complex, multi-scale data. These approaches span multiple levels of biological organization, from molecular interactions to whole-body physiology.

Molecular-level modeling includes traditional methods like molecular docking and dynamics simulation, which provide insights into drug-target interactions at atomic resolution [4]. These are complemented by machine learning approaches that predict drug-target interactions based on chemical similarity and known bioactivity data [7] [4]. For example, similarity-based methods like the Nearest Profile approach predict interactions for new compounds based on their similarity to compounds with known targets [7].

Network modeling integrates disease-related genes, pathways, targets, and drugs into unified network models, providing frameworks for understanding how cellular regulation emerges from interactions between components [4]. Important nodes and edges in these networks can be identified through topological analysis, while network dynamics simulation can determine how global network characteristics change in response to perturbations. These models provide theoretical foundations for developing multi-target drugs and drug combinations, and have been applied to understand cancer combination therapy, identify origins of drug-induced adverse events, and optimize treatment regimens [4].

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) modeling employs mathematical representations of biological systems to quantitatively simulate drug effects. A proposed six-stage workflow for robust QSP application includes [6]:

- Project needs and goals: Defining key questions and establishing collaborations

- Reviewing biology and determining scope: Identifying biological scope and required model behaviors

- Model building and calibration: Developing mathematical representations and parameterizing them with experimental data

- Model validation: Testing model predictions against independent datasets

- Simulation and analysis: Using the model to explore biological and therapeutic hypotheses

- Application and dissemination: Applying model insights to research decisions and sharing results

The following diagram illustrates this iterative QSP workflow:

QSP models typically span multiple biological scales, from molecular interactions to tissue-level and organism-level responses. The following diagram illustrates the multi-scale nature of these models and their applications:

Practical Applications and Case Studies

Drug Repurposing and Repositioning

Drug repurposing represents one of the most direct and successful applications of systems pharmacology principles. This approach identifies new therapeutic uses for existing approved drugs, leveraging their known polypharmacology to accelerate drug discovery [1]. Repurposing offers significant advantages over traditional drug development, including reduced costs, shorter development timelines, and lower risk since repurposed candidates have already undergone extensive safety testing [1] [7].

Systems pharmacology enables systematic drug repurposing through computational analysis of the complex relationships between drugs, targets, and diseases. For example, the drug Gleevec (imatinib mesylate) was initially developed to target the Bcr-Abl fusion gene in chronic myeloid leukemia but was later found to interact with PDGF and KIT, leading to its repositioning for gastrointestinal stromal tumors [7]. This example illustrates how understanding a drug's multi-target profile can reveal new therapeutic applications beyond its original indication.

Computational approaches to drug repurposing include:

- Chemical similarity methods: Predicting new targets for existing drugs based on structural similarity to compounds with known targets

- Biological similarity methods: Identifying new indications based on shared pathway perturbations or genetic associations

- Network-based approaches: Analyzing drug-target-disease networks to identify novel therapeutic relationships

- Machine learning methods: Training predictive models on known drug-target interactions to forecast new interactions

Target Deconvolution and Mechanism Elucidation

A significant challenge in drug discovery, particularly for compounds identified through phenotypic screening, is target deconvolution—identifying the molecular targets responsible for observed phenotypic effects [1]. Systems pharmacology approaches address this challenge through chemogenomic strategies that use well-characterized compound sets with overlapping target profiles.

The EUbOPEN project exemplifies this approach through its development of chemogenomic compound collections covering approximately one-third of the druggable proteome [8]. These collections consist of compounds with comprehensively characterized target profiles, enabling researchers to identify targets responsible for specific phenotypes by observing consistent effects across compounds with shared targets. This strategy is particularly valuable for studying under-explored target families like solute carriers (SLCs) and E3 ubiquitin ligases, where selective chemical probes may not yet be available [8].

Multi-Target Drug Development

Systems pharmacology provides a rational foundation for deliberate multi-target drug development, moving beyond the limitations of single-target therapies for complex diseases. This approach is particularly relevant for conditions like cancer, Alzheimer's disease, and metabolic disorders, where multiple pathways are dysregulated simultaneously.

For example, in Alzheimer's disease, QSP models have been used to explore combination therapies that simultaneously target amyloid-beta production, tau pathology, and neuroinflammation—addressing multiple aspects of the disease pathology in an integrated manner [5] [4]. Similarly, in cancer, systems pharmacology approaches have identified optimal drug combinations that target multiple signaling pathways while minimizing overlapping toxicities [4].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for systems pharmacology-driven drug discovery:

The paradigm shift from 'one-drug-one-target' to systems pharmacology represents a fundamental transformation in how we approach therapeutic intervention. This new paradigm acknowledges the inherent complexity of biological systems and the network-based nature of diseases, leveraging this understanding to develop more effective therapeutic strategies. By integrating multi-scale data through computational modeling, systems pharmacology enables more predictive approaches to drug discovery and development, with the potential to reduce attrition rates and improve therapeutic outcomes.

Future advances in systems pharmacology will likely be driven by several key developments. First, the continued expansion of open-source chemical and biological resources, such as those being developed by initiatives like EUbOPEN and Target 2035, will provide increasingly comprehensive coverage of the druggable genome [8]. Second, advances in computational methods, particularly in artificial intelligence and multi-scale modeling, will enhance our ability to predict drug effects in silico before proceeding to costly clinical trials [5] [4]. Third, the integration of patient-specific data, including genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, will enable more personalized therapeutic approaches tailored to individual patients' biological networks [3].

Ultimately, the adoption of systems pharmacology approaches promises to transform drug discovery from a primarily empirical process to a more predictive, quantitative science. This transformation is already underway, with QSP models being used in regulatory decision-making and pharmaceutical R&D [6]. As these approaches continue to mature and evolve, they offer the potential to address some of the most challenging obstacles in modern therapeutics, delivering safer, more effective medicines for complex diseases that have thus far eluded successful treatment.

Chemogenomics represents a systematic approach in drug discovery that investigates the interaction of chemical compounds with biological targets on a genome-wide scale. This field relies on the concept of "druggability" – the likelihood that a protein can be effectively targeted by small-molecule drugs. The four major families discussed in this whitepaper – Kinases, G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs), E3 Ubiquitin Ligases, and Solute Carriers (SLCs) – constitute a significant portion of the druggable proteome and are the focus of intensive research in both academic and industrial settings. The exploration of these families is being dramatically accelerated by large-scale public-private partnerships such as the EUbOPEN consortium, which aims to generate and characterize chemical tools for thousands of human proteins by 2035 as part of the Target 2035 initiative [8]. These efforts are producing chemogenomic libraries, comprehensive sets of well-annotated compounds that allow researchers to link biological phenotypes to specific targets within these families, thereby driving innovation in therapeutic development [9] [10].

Table 1: Overview of Major Druggable Target Families

| Target Family | Representative Members | Approved Drugs (Count) | Key Therapeutic Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinases | EGFR, BCR-ABL, BTK, CDK4/6 | 100+ small-molecule inhibitors [11] | Oncology, Inflammation |

| GPCRs | CGRPR, GLP-1R, CCR4 | 516 drugs (36% of all approved drugs) [12] | Metabolic, CNS, Cardiovascular |

| E3 Ligases | CRBN, VHL, DCAF2 | Limited (but key for TPD) [13] | Oncology, Undruggable targets |

| SLC Transporters | SLC39A10, SLC22B5, SLC55A2 | Emerging targets [14] | Metabolic disorders, Oncology |

Protein Kinases

Biological Significance and Therapeutic Validation

Protein kinases constitute one of the most successfully targeted enzyme families in pharmaceutical research, with the FDA having approved the 100th small-molecule kinase inhibitor in 2025 [11]. These enzymes catalyze protein phosphorylation, a fundamental regulatory mechanism that controls nearly all cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. The transformative approval of imatinib (Gleevec) in 2001 for chronic myeloid leukemia demonstrated that kinases were indeed druggable targets, overcoming initial skepticism about achieving specificity among the more than 500 human kinases that share structurally similar ATP-binding pockets [11]. This breakthrough initiated a "kinase craze" in drug discovery that continues to yield new therapeutics. Kinase inhibitors have evolved from initial focus on cancer to applications in inflammatory diseases, neurological disorders, and other therapeutic areas. The top-selling kinase inhibitors include osimertinib (EGFR-T790M; $6.6B in 2024 sales), ibrutinib (BTK; $6.4B), and upadacitinib (JAK1; $6B), reflecting both their clinical impact and commercial significance [11].

Key Experimental Approaches for Kinase Research

The development of kinase-targeted therapies relies on specialized experimental frameworks that address the challenges of target specificity and resistance mechanisms.

Chemogenomic Library Screening: The kinase chemogenomic set (KCGS), comprising well-annotated kinase inhibitors with defined selectivity profiles, enables systematic screening in disease-relevant assays [9]. This approach allows researchers to identify kinases critical for specific pathological processes by observing phenotypic responses to inhibitors with overlapping but distinct target spectra. The EUbOPEN consortium has extended these efforts through creation of comprehensive chemogenomic libraries covering approximately one-third of the druggable proteome [8].

Resistance Mechanism Analysis: As seen with EGFR and ALK inhibitors, acquired resistance commonly emerges through gatekeeper mutations (e.g., T790M in EGFR) or alternative pathway activation [11]. Profiling resistant cell lines using next-generation sequencing and structural biology (cryo-EM and crystallography) informs the design of next-generation inhibitors capable of overcoming these resistance mechanisms. Osimertinib exemplifies this approach, specifically designed to target the T790M mutant while sparing wild-type EGFR [11].

Selectivity Profiling: Assessing kinase inhibitor specificity through broad-scale profiling across the kinome is essential for understanding both efficacy and toxicity. Techniques include competitive binding assays, kinome-wide selectivity panels, and functional cellular assays that measure pathway modulation.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Kinase Inhibitor Development

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Kinase Studies

| Reagent Type | Specific Example | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemogenomic Library | EUbOPEN Kinase Set [8] | Target identification and validation through phenotypic screening |

| Selectivity Profiling Panel | Kinobeads / KINOMEscan | Comprehensive assessment of inhibitor specificity across kinome |

| Resistance Models | T790M EGFR mutant cell lines [11] | Study resistance mechanisms and test next-generation inhibitors |

| Structural Biology Tools | Cryo-EM structures of kinase-ligand complexes [13] | Rational drug design based on binding modes |

G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs)

Structural Diversity and Therapeutic Relevance

G-Protein Coupled Receptors constitute the largest family of membrane proteins in the human genome, with approximately 800 members that detect diverse extracellular stimuli including photons, odorants, tastants, ions, small molecules, peptides, and proteins [12]. These receptors share a characteristic seven-transmembrane α-helical structure but are divided into six classes based on sequence homology and functional characteristics: Class A (Rhodopsin-like; ~80% of GPCRs), Class B (Secretin/Adhesion), Class C (Glutamate), and Class F (Frizzled/Taste2) [15]. GPCRs mediate their effects through activation of heterotrimeric G proteins (Gα and Gβγ) or β-arrestin signaling pathways, subsequently regulating production of second messengers including cAMP and Ca²⁺ to influence cellular functions [15]. Their central role in physiological processes and accessibility at the cell surface have made GPCRs highly successful drug targets, with 516 approved drugs (36% of all approved drugs) targeting 121 GPCRs [12]. These therapeutics span all major disease areas, including cardiovascular disorders, metabolic diseases, cancer, and neurological conditions.

Emerging Modalities and Research Methods

While small molecules continue to dominate the GPCR therapeutic landscape, new modalities are emerging that address limitations of traditional approaches.

Antibody-Based Therapeutics: GPCR-targeting antibodies offer several advantages over small molecules, including superior specificity for extracellular domains, longer half-lives (enabling weekly or monthly dosing), and limited central nervous system exposure due to inability to cross the blood-brain barrier [15]. Currently, three GPCR-targeting antibodies have received FDA approval: mogamulizumab (CCR4; T-cell lymphoma), erenumab (CGRPR; migraine prevention), and fremanezumab/galcanezumab (CGRP; migraine) [15]. The remarkable commercial success of CGRP-targeting antibodies (>$5 billion combined annual sales) has validated this approach and stimulated development of over 170 additional GPCR-targeting antibody candidates currently in preclinical to Phase III development [15].

Targeted Protein Degradation: Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) and other targeted protein degradation technologies represent a promising new approach for targeting GPCRs that have proven refractory to conventional modulation [16]. These bifunctional molecules simultaneously bind to the target GPCR and an E3 ubiquitin ligase, inducing ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of the receptor. Although application to membrane proteins like GPCRs presents unique challenges, early successes in degrading receptors such as the β2-adrenoceptor and CXCR4 demonstrate feasibility [16]. Key to advancing this approach is the discovery of intracellular allosteric small-molecule binders that can serve as GPCR-targeting warheads for PROTAC design.

Advanced Protein Production Platforms: The complex seven-transmembrane structure of GPCRs has historically made production of high-quality antigens challenging. Recent advances in virus-like particle (VLP) and Nanodisc platforms maintain native GPCR conformation and bioactivity by preserving the essential phospholipid bilayer environment [15]. These technologies enable critical applications in antibody development including phage display panning, yeast display screening, SPR analysis, and FACS assays, accelerating discovery of biologics targeting previously intractable GPCRs.

Figure 2: Simplified GPCR Signaling Pathway

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

Biological Functions and Emerging Therapeutic Applications

E3 ubiquitin ligases constitute a diverse family of more than 600 enzymes that confer substrate specificity to the ubiquitin-proteasome system, orchestrating the transfer of ubiquitin to target proteins and thereby influencing their stability, activity, or localization [13] [17]. These enzymes function as critical regulators of virtually all cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, DNA damage repair, and signal transduction. While only a handful of E3 ligases have been pharmacologically targeted to date, they represent promising therapeutic targets both for direct modulation in diseases where their activity is dysregulated and as recruitment hubs for targeted protein degradation (TPD) strategies [17]. The latter application has generated substantial excitement as it enables addressing previously "undruggable" targets, including transcription factors and non-enzymatic proteins that lack conventional binding pockets for small-molecule inhibition.

Research Strategies for E3 Ligase Exploration

Chemical Probe Development: A primary bottleneck in E3 ligase research has been the scarcity of high-quality chemical probes – potent, selective, cell-active small molecules that modulate E3 function [8]. The EUbOPEN consortium has established stringent criteria for E3 ligase chemical probes, requiring potency <100 nM in vitro, at least 30-fold selectivity over related proteins, demonstrated target engagement in cells at <1 μM, and adequate cellular toxicity windows [8]. These probes serve as essential tools for validating E3 ligases as therapeutic targets and as starting points for degrader development.

Ligase Handle Identification: For TPD applications, researchers must identify "E3 handles" – small molecule ligands that bind to E3 ligases and provide attachment points for linker incorporation in PROTAC design [8]. Recent work has identified DCAF2 as a novel E3 ligase that can be harnessed for TPD, particularly promising for cancer applications given its frequent overexpression in tumors [13]. Advanced structural biology techniques, particularly cryo-electron microscopy, have been instrumental in characterizing these ligases and their ligand interactions, as demonstrated by the first reported structures of DCAF2 in both apo and liganded states [13].

Covalent Targeting Strategies: Some E3 ligases have proven resistant to conventional orthosteric inhibition due to extensive protein-protein interaction interfaces or absence of deep binding pockets. Covalent targeting strategies offer an alternative approach, as exemplified by recent development of small-molecule covalent inhibitors targeting the Cul5-RING ubiquitin E3 ligase substrate receptor subunit SOCS2 [8]. These compounds employ structure-based design to target specific cysteine residues within challenging binding domains, expanding the range of addressable E3 ligases.

Table 3: Research Resources for E3 Ligase Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Applications and Features |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | EUbOPEN Donated Chemical Probes [8] | Peer-reviewed compounds with negative controls; 50 new probes developed |

| Covalent Inhibitors | SOCS2-targeting compounds [8] | Target hard-to-drug domains like SH2; employ pro-drug strategies for permeability |

| Structural Resources | Cryo-EM structures of DCAF2 [13] | Guide rational design of ligands and degraders |

| E3 Handle Collection | Emerging E3 ligase ligands [8] | Provide starting points for PROTAC design against novel E3s |

Solute Carriers (SLCs)

Physiological Roles and Disease Associations

The solute carrier superfamily represents a vast group of more than 450 membrane transport proteins organized into 65 distinct families based on sequence similarity and transport function [14]. These transporters facilitate movement of diverse substrates including drugs, metabolites, and ions across cellular membranes, thereby regulating metabolic pathways, signal transduction, and nutrient sensing. SLCs are increasingly recognized as important players in disease pathophysiology, particularly in cancer where they frequently undergo altered expression to support the metabolic demands of rapidly proliferating cells. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), for example, comprehensive analysis has revealed significant dysregulation of SLC transporters, with 355 SLC genes showing marked upregulation and 43 showing downregulation in tumor compared to normal tissues [14]. Specific transporters including SLC39A10, SLC22B5, SLC55A2, and SLC30A6 demonstrate strong association with unfavorable overall survival, highlighting their potential as prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Research Methodologies for SLC Investigation

Multi-Omics Profiling: Integrative analysis of SLCs requires combining genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic datasets from resources such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) [14]. Differential expression analysis between normal and disease tissues identifies consistently dysregulated transporters, while survival analysis using Kaplan-Meier plots and Cox proportional hazards models evaluates prognostic significance. These approaches have identified SLC39A10 as a particularly promising target in PDAC, with high expression associated with a hazard ratio of 1.89 for overall survival [14].

Functional Enrichment Analysis: Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) applied to SLC expression data reveals involvement in critical oncogenic pathways. In PDAC, key SLC transporters are significantly enriched in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), TNF-α signaling, and angiogenesis pathways [14], providing mechanistic insight into how these transporters influence cancer progression and suggesting potential combination therapeutic strategies.

Structural Prediction and Validation: The structural characterization of SLCs has been accelerated by deep learning-based prediction tools such as AlphaFold and AlphaMissense, which generate highly detailed 3D models and analyze functional consequences of missense mutations [14]. These computational approaches guide experimental validation and structure-based drug design for this challenging protein class.

Chemogenomic Library Screening: As with kinases and GPCRs, SLC-focused chemogenomic sets are being developed to enable systematic functional screening. The EUbOPEN project includes SLCs among its priority target families, creating well-annotated compound collections that allow researchers to link transport phenotypes to specific SLC modulation [8].

Integrated Experimental Framework for Target Family Research

Chemogenomic Library Implementation

The power of chemogenomic approaches lies in the systematic application of compound sets with defined target profiles to elucidate novel biology and therapeutic opportunities. Implementation follows a standardized workflow:

Library Design and Curation: Chemogenomic sets are assembled from hundreds of thousands of bioactive compounds generated by medicinal chemistry efforts in both industrial and academic sectors [8]. These collections include compounds with varying selectivity profiles – from highly specific chemical probes to broader inhibitors that simultaneously engage multiple targets within a family. The EUbOPEN consortium applies family-specific criteria for compound selection, considering availability of well-characterized compounds, screening possibilities, ligandability of different targets, and ability to collate multiple chemotypes per target [8].

Phenotypic Screening: Application of chemogenomic sets to disease-relevant cellular models, including patient-derived primary cells, generates rich phenotypic datasets [8]. For the EUbOPEN project, particular focus areas include inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, and neurodegeneration. The use of multiple compounds with overlapping target profiles enables sophisticated target deconvolution through pattern recognition approaches.

Target Validation and Mechanistic Follow-up: Compounds producing phenotypes of interest undergo rigorous validation, including dose-response studies, counter-screening, and genetic validation using CRISPR/Cas9 or RNA interference. The availability of comprehensive bioactivity data for these compounds accelerates the transition from phenotypic hit to validated target.

Data Integration and Resource Accessibility

A critical component of modern target family research is the development of integrated data platforms that consolidate chemical, biological, and clinical information. Resources such as GPCRdb provide comprehensive information on approved drugs and clinical trial agents targeting GPCRs, including pharmacological data, structural information, and disease indications [12]. Similarly, the EUbOPEN consortium is establishing centralized repositories for its chemical probes, chemogenomic sets, and associated screening data, ensuring broad accessibility to the research community [8]. These resources incorporate sophisticated visualization tools, such as Sankey diagrams illustrating connections between agents, targets, and diseases, along with filtering capabilities that enable researchers to identify agents being repurposed across indications or novel targets entering clinical development [12].

The systematic investigation of major druggable target families – kinases, GPCRs, E3 ligases, and SLCs – represents a cornerstone of modern drug discovery. While kinases and GPCRs have established robust track records of therapeutic success, E3 ligases and SLCs constitute emerging frontiers with substantial untapped potential. Advances in structural biology, chemical probe development, and chemogenomic library screening are accelerating our understanding of these protein families and their roles in disease pathophysiology. Large-scale collaborative initiatives such as EUbOPEN and Target 2035 are critically important for generating the high-quality chemical tools and datasets needed to fully exploit the therapeutic potential of the druggable proteome. As these efforts continue to mature, researchers will be increasingly equipped to develop innovative therapeutics targeting not only well-validated proteins but also challenging targets currently considered undruggable, ultimately expanding the medicine cabinet available for addressing human disease.

Twenty years after the sequencing of the human genome, a profound disconnect remains between our genetic knowledge and the development of effective medicines. While the human proteome consists of approximately 20,000 proteins, only about 5% has been successfully targeted for drug discovery [18]. Approximately 35% of the human proteome remains functionally uncharacterized—often referred to as the "dark proteome"—creating a significant bottleneck in translating genomic insights into new therapeutics [18]. The Target 2035 Initiative emerged as an ambitious international response to this challenge, with the primary goal of developing a pharmacological modulator for every protein in the human proteome by the year 2035 [19]. Founded on open science principles and structured as a federation of biomedical scientists from both public and private sectors, this initiative recognizes that proteins, not genes, are the primary executers of biological function and that understanding disease mechanisms requires sophisticated tools to study protein function at scale [18] [20].

The initiative's conceptual framework is intrinsically linked to chemogenomics research, which seeks to systematically understand interactions between chemical compounds and protein families. Chemical probes—high-quality, selective small molecules or biological agents that modulate protein function—serve as essential tools for validating therapeutic targets and de-risking early drug discovery [18]. By creating these research tools for the entire proteome, Target 2035 aims to illuminate biological pathways and accelerate the development of new medicines for unmet medical needs, ultimately bridging the gap between genomics and therapeutics through a systematic, protein-family-centric approach [18].

Quantitative Landscape of the Druggable Proteome

Current Status of Protein Targeting

The following table summarizes the current landscape of drug targets and the scope of the challenge facing Target 2035:

Table 1: The Druggable Proteome - Current Status and Projected Goals

| Category | Number of Proteins | Percentage of Proteome | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins targeted by FDA-approved drugs [21] | 754 | ~3.8% | Primarily enzymes, transporters, ion channels, and receptors |

| Druggable genome [19] | ~4,000 | ~20% | Proteins with binding pockets capable of binding drug-like molecules |

| Characterized human proteome [18] | ~13,000 | ~65% | Proteins with varying degrees of functional annotation |

| Dark proteome [18] | ~7,000 | ~35% | Uncharacterized proteins lacking functional information or research tools |

| Target 2035 Goal [19] | ~20,000 | ~100% | Pharmacological modulators for the entire human proteome |

Protein Family Distribution of Current Drug Targets

The limited universe of currently targeted proteins reveals a distinct bias toward specific protein families that have historically been most accessible to drug discovery efforts:

Table 2: Protein Family Classification of FDA-Approved Drug Targets [21]

| Protein Class | Number of Genes | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | 304 | Gastric triacylglycerol lipase (LIPF) |

| Transporters | 182 | - |

| G-protein coupled receptors | 103 | Thyroid stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) |

| Voltage-gated ion channels | 55 | CACNA1S |

| CD markers | 79 | - |

| Nuclear receptors | 21 | - |

Membrane-bound or secreted proteins constitute approximately 67% of current drug targets, reflecting the historical preference for targets accessible to antibody-based therapies or small molecules that can modulate extracellular domains [21]. This distribution highlights the significant technical challenges that must be overcome to target intracellular protein-protein interactions and other non-traditional target classes.

The Target 2035 Implementation Framework

Phase-Based Strategic Roadmap

Target 2035 operates through a carefully structured two-phase implementation plan designed to build momentum and systematically address technical challenges [19]:

Phase 1 (2020-2025): Foundation Building

- Collect and characterize existing pharmacological modulators for key representatives from all protein families in the current druggable genome (~4,000 proteins) [19]

- Develop centralized infrastructure for data collection, curation, dissemination, and mining [18]

- Create centralized facilities for quantitative genome-scale biochemical and cell-based profiling assays [19]

- Establish quality criteria and validation standards for chemical probes to ensure research reproducibility [18]

- Launch technology development initiatives for hit-finding and characterization, including benchmarking computational methods [19]

Phase 2 (2025-2035): Proteome-Scale Expansion

- Apply developed technologies and infrastructure to generate complete sets of pharmacological modulators for the entire human proteome [19]

- Tackle challenging protein classes including intrinsically disordered proteins, protein-protein interactions, and non-enzymatic functions [18]

- Expand into undruggable target space using new modalities such as targeted protein degradation [18]

- Leverage artificial intelligence to prioritize targets and design compounds for the most challenging targets [22]

Target 2035 Initiative Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow and key initiatives within the Target 2035 ecosystem:

Key Methodologies and Experimental Frameworks

Computational Hit-Finding Benchmarking (CACHE)

The Critical Assessment of Computational Hit-finding Experiments (CACHE) initiative represents a public-private partnership that provides a platform for benchmarking computational hit-finding algorithms through prospective experimental validation [20]. Unlike retrospective benchmarks that evaluate methods on known binders, CACHE operates prospectively: participants predict compounds for novel targets, these compounds are procured and tested experimentally, and binding data are returned to participants [20]. This approach evaluates real-world performance metrics including hit rate, diversity, and drug-likeness rather than merely binding pose accuracy [20].

Experimental Protocol:

- Target Selection: Expert-curated novel protein targets with no publicly known binders are selected (e.g., LRRK2 WD40 repeat domain, SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 RNA-binding domain) [20]

- Compound Prediction: Computational groups submit up to 100 predicted ligands for each target [20]

- Experimental Testing: Predicted compounds are purchased and evaluated using biophysical and biochemical methods [20]

- Feedback Loop: Successful participants proceed to a second round of predictions incorporating initial experimental results [20]

- Data Dissemination: All binding data and outcomes are made publicly available to advance the field [20]

Chemogenomic Library Development (EUbOPEN)

The EUbOPEN (Enable and Unlock Biology in the OPEN) consortium is generating the largest freely available set of high-quality chemical modulators for human proteins, with a goal of covering 1,000 targets by 2025 [10] [18]. This initiative takes a protein family approach, focusing on understudied target classes such as solute carriers (SLCs) and ubiquitin ligases (E3s) where high-quality small-molecule binders have historically been scarce [18].

Methodological Framework:

- Target Prioritization: Selection based on biological relevance, disease association, and tool compound availability [18]

- Assay Development: Implementation of robust biochemical and cell-based assays suitable for high-throughput screening [18]

- Compound Profiling: Comprehensive characterization of selectivity, potency, and cellular activity across established and novel assay systems [18]

- Data Annotation: Integration of activity data from multiple orthogonal assays, including those derived from primary patient cells [18]

- Resource Sustainability: Partnership with chemical vendors and database providers to ensure long-term availability of compounds and data [18]

Open Science and Private Sector Collaboration

Target 2035 leverages unprecedented private sector engagement through various open science initiatives:

Table 3: Private Sector Contributions to Target 2035 [20]

| Organization | Initiative | Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Bayer | Chemical Probe Donation & Co-development | 28 chemical probes donated to open science, including BAY-678 (HNE inhibitor) and BAY-598 (SMYD2 inhibitor) |

| Boehringer Ingelheim | opnMe Platform | 74 probe molecules available "Molecules to Order"; additional compounds for collaboration |

| Multiple Companies | CACHE Initiative | Co-development of computational benchmarking challenges and experimental validation |

| Pharmaceutical Consortium | EUbOPEN Project | Contribution of compounds, expertise, and screening capabilities for chemogenomic library development |

Knowledge Graphs and AI-Driven Target Prioritization

A central technological paradigm within Target 2035 involves the construction of comprehensive knowledge graphs that integrate multi-scale data from the gene level down to individual protein residues [22]. These graphs synthesize information from public resources including:

- Open Targets: Target-disease associations and tractability assessments [22]

- PDBe-KB: Residue-level functional annotations in the context of 3D structures [22]

- canSAR: Integrated data and predictions for drug discovery applications [22]

Automated Workflow for Structural Druggability Assessment:

- Structure Preparation: Automated processing of experimental and predicted structures (including AlphaFold 2 models) to ensure consistency and completeness [22]

- Pocket Detection: Identification of potential binding sites across all available structures for a given target [22]

- Hotspot Analysis: Residue-level druggability assessment using molecular dynamics or static structure approaches [22]

- Druggability Scoring: Integration of multiple parameters including pocket physicochemical properties, conservation, and functional relevance [22]

- Knowledge Graph Integration: Incorporation of residue-level tractability annotations with target-level evidence for AI-based navigation [22]

The complexity of these integrated knowledge graphs exceeds human analytical capacity, necessitating the use of graph-based AI algorithms to expertly navigate the data and identify high-priority targets [22]. This approach enables the systematic expansion of the druggable genome into novel and overlooked areas by automating the multi-parameter assessment traditionally performed by multidisciplinary teams.

Target 2035 Knowledge Graph Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the structure of the integrated knowledge graph that supports AI-driven target prioritization:

Research Reagent Solutions for the Target 2035 Ecosystem

The implementation of Target 2035 relies on a diverse set of research reagents and platforms that enable the systematic mapping of the druggable proteome. The following table details key resources available to researchers:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms in Target 2035

| Resource/Platform | Type | Function/Role | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| EUbOPEN Chemogenomic Library [10] [18] | Compound Collection | Curated set of ~4,000-5,000 compounds covering major target families; enables phenotypic screening and target deconvolution | Publicly available via EUbOPEN Gateway |

| MAINFRAME [23] | Data & Collaboration Network | International network of ML researchers providing access to curated datasets and experimental feedback for model benchmarking | Membership-based collaboration |

| CACHE Challenges [23] [20] | Benchmarking Platform | Experimental testing of computational predictions for real-world algorithm validation | Open participation |

| Open Chemistry Networks [18] | Distributed Chemistry | Community-driven synthetic chemistry resources for probe development | Open contribution model |

| SGC Protein Contribution Network [23] | Protein Production | Supply of purified, high-quality proteins for ligand screening | Contributor network |

| opnMe Portal (Boehringer Ingelheim) [20] | Compound Access | Well-characterized preclinical molecules available free-of-charge for research | Open ordering system |

| PDBe-KB [22] | Knowledge Base | Residue-level structural annotations and druggability assessments | Public database |

| IDG Resources [18] | Target Characterization | Chemical tools, assays, expression data, and knockout mice for dark genome proteins | Public portal access |

Target 2035 represents a paradigm shift in how the biomedical research community approaches the fundamental challenge of linking genomics to therapeutics. By establishing an open science framework that systematically addresses the "dark proteome" through pharmacological tool development, the initiative creates the necessary foundation for a new era of target-informed drug discovery. The protein family-centric approach, coupled with innovative computational benchmarking and knowledge graph technologies, provides a scalable model for expanding the druggable genome.

The success of Target 2035 hinges on continued collaboration across sectors and disciplines, technological innovation in computational and experimental methods, and sustained commitment to open science principles. If successful, the initiative will not only provide critical research tools for the entire human proteome but will also establish a new model for pre-competitive collaboration that accelerates the translation of basic biological insights into medicines for patients.

Chemogenomics represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, moving from single-target approaches to the systematic exploration of interactions across entire biological systems. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of ligand and target space concepts framed within the context of target families in modern chemogenomics research. We define the core principles of chemogenomic space, present analytical frameworks for studying ligand-target interactions, and detail experimental and computational methodologies for mapping these complex relationships. The article includes comprehensive protocols for key experiments, visualizations of critical workflows, and a curated toolkit of research reagents essential for chemogenomic investigations. By integrating both ligand-based and target-based perspectives, this work aims to equip researchers with the fundamental knowledge and practical methodologies needed to navigate and exploit the vast landscape of ligand-target interactions for therapeutic discovery.

Chemogenomics is an interdisciplinary approach to drug discovery that combines traditional ligand-based methods with biological information on drug targets, operating at the interface of chemistry, biology, and informatics [24]. The ultimate goal in chemogenomics is to understand molecular recognition between all possible ligands and all possible drug targets in the proteome [24]. This field has emerged from advances in genomics and high-throughput screening technologies, enabling a more global and comparative analysis of potential therapeutic targets compared to traditional single-target approaches [25].

The ligand space encompasses all possible molecules that can potentially interact with biological targets. The chemical space of reasonably sized molecules (up to ~600 Da molecular weight) is extraordinarily large, with mid-range estimates reaching approximately 10^62 possible compounds [24]. In contrast, the target space consists of all biological macromolecules that can interact with ligands, with the human proteome estimated to contain more than 1 million different proteins arising from phenomena such as alternative splicing and post-translational modifications [24]. The relationship between ligand and binding partner is a function of charge, hydrophobicity, and molecular structure, with binding occurring through intermolecular forces such as ionic bonds, hydrogen bonds, and Van der Waals forces [26].

The intersection between these spaces creates a sparse chemogenomic grid where experimental data is available for only a very limited fraction of possible protein-ligand complexes [24]. This sparsity represents both a challenge and opportunity for drug discovery, necessitating sophisticated computational and experimental approaches to map and exploit this vast interaction space. Understanding the organization of this space around target families—groups of proteins with structural or sequential similarity—has become a fundamental strategy for navigating chemogenomic relationships and predicting novel interactions [25].

The Ligand-Target Matrix: Framework for Chemogenomic Analysis

The ligand-target knowledge space is conceptually organized as a two-dimensional matrix where targets form the x-axis and ligands constitute the y-axis [27]. Each cell in this matrix contains information about the activity of a specific ligand against a particular target, creating a comprehensive interaction map. This representation enables systematic analysis of polypharmacology—how single ligands interact with multiple targets—and target profiling—how single targets interact with multiple ligands [27].

Data Sparsity and Completeness Challenges

A fundamental challenge in working with ligand-target matrices is their extreme sparsity, as most ligand-target pairs lack any experimental data [28]. This sparsity can be quantified through several metrics:

- Global Data Completeness (GDC): The overall fraction of tested ligand-target pairs in the matrix [28]

- Ligand-based Local Data Completeness (LDC(l)): The fraction of targets tested for a specific ligand [28]

- Target-based Local Data Completeness (LDC(t)): The fraction of ligands tested against a specific target [28]

The average values of LDC(l) and LDC(t) equal the GDC, providing complementary perspectives on data distribution [28]. This sparsity means that publicly available datasets often appear as "islands of data floating on a largely empty sea," creating significant challenges for comprehensive analysis [28].

Ternary Set-Theoretic Formalism

Traditional binary approaches (active/inactive) are insufficient for representing ligand-target interactions due to this sparsity. A more robust ternary set-theoretic formalism incorporates three states for each ligand-target pair [28]:

- Active pairs: Ligand-target interactions exceeding a defined activity threshold

- Inactive pairs: Ligand-target pairs tested below the activity threshold

- Null pairs: Pairs with unknown interaction status

This ternary approach enables more accurate modeling of polypharmacology by accounting for uncertainty in untested interactions and providing bounds for potential activities [28]. The formalism allows projection of ternary relations into simpler unary relations for practical computation of pharmacological properties while preserving information about data completeness and uncertainty [28].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Target-Centric and Ligand-Centric Approaches

Computational prediction of ligand-target interactions generally falls into two categories [29]:

Target-centric methods focus on the properties of biological targets, using techniques such as:

- Molecular docking: Predicting ligand orientation and binding affinity within target binding sites [29]

- Structure-based QSAR: Relating target structural features to ligand activity [30]

- Machine learning models: Training classifiers on target sequence, structure, or family information [29]

Ligand-centric methods focus on compound properties, including:

- Similarity searching: Identifying similar known ligands to infer target interactions [29]

- Chemical similarity profiling: Comparing compound structural fingerprints [25]

- Activity spectrum analysis: Matching biological activity profiles [25]

Recent approaches increasingly integrate both perspectives to improve prediction accuracy, acknowledging that ligand-target binding is ultimately determined by complementary properties of both interaction partners [30] [29].

Fragment Interaction Model (FIM)

The Fragment Interaction Model provides a sophisticated framework for understanding the structural basis of ligand-target recognition [30]. This approach decomposes binding sites and ligands into fragments or substructures, then models interactions between these components:

- Target dictionary creation: Cluster protein trimers based on physicochemical properties to create a fragment library [30]

- Ligand dictionary creation: Define molecular substructures representing chemical features [30]

- Interaction mapping: Build a fragment interaction network capturing relationships between target and ligand fragments [30]

- Binding prediction: Use the interaction network to predict novel ligand-target interactions [30]

FIM has demonstrated superior predictive performance (AUC = 92%) compared to other methods and provides chemical insights into binding mechanisms through its fragment-level resolution [30].

Diagram: Fragment Interaction Model (FIM) Workflow. This diagram illustrates the process of building a fragment interaction model from protein and ligand structures to predict novel interactions.

Chemogenomic Library Screening

Systematic screening of compound libraries against target families represents a core experimental methodology in chemogenomics [8]. The EUbOPEN consortium exemplifies this approach through its development of:

- Chemical probes: Highly characterized, potent, and selective cell-active small molecules that modulate specific protein functions [8]

- Chemogenomic (CG) compounds: Potent inhibitors or activators with narrow but not exclusive target selectivity, enabling target deconvolution through selectivity patterns [8]

High-quality chemical probes must meet strict criteria including potency <100 nM in vitro, at least 30-fold selectivity over related proteins, demonstrated target engagement in cells at <1 μM, and reasonable cellular toxicity windows [8].

Data Analysis and Visualization Techniques

Principal Component Analysis of Protein-Ligand Space

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) provides a powerful method for visualizing and analyzing high-dimensional chemogenomics data [24]. The standard workflow involves:

- Descriptor calculation: Compute sequence-based descriptors for proteins and 0D-2D descriptors for ligands [24]

- Data integration: Combine protein and ligand descriptors into a unified feature space [24]

- Dimension reduction: Apply PCA to project data into 2D or 3D visualizations [24]

- Space comparison: Use nearest neighbor methods to quantify overlap between different chemogenomics datasets [24]

This approach enables researchers to visualize global relationships in protein-ligand space, identify clusters of similar interactions, and compare different subspaces such as structural protein-ligand space versus approved drug-target space [24].

Diagram: PCA Analysis of Protein-Ligand Space. This workflow shows the process of reducing multidimensional chemogenomic data into visualizable components.

Target Prediction Method Performance

Comparative studies of target prediction methods provide guidance for selecting appropriate computational approaches. A recent systematic evaluation of seven prediction methods revealed significant performance differences [29]:

Table 1: Target Prediction Method Performance Comparison

| Method | Type | Algorithm | Key Features | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolTarPred | Ligand-centric | 2D similarity | MACCS or Morgan fingerprints | Most effective method in evaluation [29] |

| PPB2 | Ligand-centric | Nearest neighbor/Naïve Bayes/DNN | MQN, Xfp and ECFP4 fingerprints | Top 2000 similar ligands [29] |

| RF-QSAR | Target-centric | Random forest | ECFP4 fingerprints | Top 4, 7, 11, 33, 66, 88 and 110 [29] |

| TargetNet | Target-centric | Naïve Bayes | Multiple fingerprint types | FP2, Daylight-like, MACCS, E-state [29] |

| ChEMBL | Target-centric | Random forest | Morgan fingerprints | Based on ChEMBL database [29] |

| CMTNN | Target-centric | Neural network | ONNX runtime | ChEMBL 34 database [29] |

| SuperPred | Ligand-centric | 2D/fragment/3D similarity | ECFP4 fingerprints | Combines multiple similarity measures [29] |

Optimization strategies can significantly impact performance. For MolTarPred, Morgan fingerprints with Tanimoto similarity outperformed MACCS fingerprints with Dice similarity [29]. High-confidence filtering of training data improves precision but reduces recall, making it less suitable for drug repurposing applications where sensitivity is prioritized [29].

Essential Databases and Tools

Successful chemogenomics research requires access to comprehensive databases and specialized analytical tools:

Table 2: Essential Chemogenomics Research Resources

| Resource | Type | Key Contents | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL | Database | 2.4M+ compounds, 15.5K+ targets, 20.7M+ interactions [29] | Target prediction, polypharmacology analysis, model training [29] |

| PDB | Database | 50,000+ macromolecular structures [24] | Structural analysis, binding site characterization, docking [24] |

| DrugBank | Database | 1,492 approved drugs with target information [24] | Drug repurposing, side-effect prediction, target validation [24] |

| EUbOPEN CG Library | Compound library | Chemogenomic compounds covering 1/3 of druggable proteome [8] | Target family screening, selectivity profiling, chemical biology [8] |

| EUbOPEN Chemical Probes | Compound collection | 100+ high-quality chemical probes with negative controls [8] | Target validation, mechanistic studies, assay development [8] |

| Fragment Interaction Model | Computational method | Target and ligand fragment dictionaries [30] | Binding mechanism analysis, interaction prediction [30] |

| MolTarPred | Prediction tool | 2D similarity-based target prediction [29] | Drug repurposing, target identification, polypharmacology [29] |

Experimental Protocols

Fragment Interaction Model Implementation

Purpose: To predict ligand-target interactions through fragment-fragment recognition patterns [30]

Steps:

- Data Preparation: Extract target-ligand complexes from sc-PDB database. Define binding sites as amino acid residues with at least one atom within 8Å of the ligand [30]

- Target Dictionary Generation:

- Ligand Dictionary Creation:

- Feature Vectorization:

- Model Building and Validation:

Applications: Target identification for orphan compounds, polypharmacology prediction, binding mechanism analysis [30]

Chemogenomic Compound Profiling

Purpose: To characterize compound activity across multiple targets within a target family [25]

Steps:

- Assay Selection: Identify representative targets covering diversity within target family [25]

- Concentration Range Testing: Determine IC50, Ki, or EC50 values across appropriate concentration ranges (typically 0.1 nM - 10 μM) [8]

- Selectivity Assessment: Calculate selectivity scores and generate interaction profiles [25]

- Cellular Target Engagement: Verify cellular activity and measure toxicity windows [8]

- Data Integration: Compile results into ligand-target interaction matrix and analyze selectivity patterns [25]

Quality Standards: For chemical probes, require <100 nM potency, ≥30-fold selectivity, cellular target engagement at <1 μM, and adequate toxicity window [8]

The systematic exploration of ligand and target space represents the foundation of modern chemogenomics research. By integrating ligand-based and target-based perspectives through computational and experimental approaches, researchers can navigate the complex landscape of molecular recognition relationships. The methodologies, resources, and protocols outlined in this technical guide provide a framework for advancing target family-based research, enabling more efficient drug discovery through better understanding of polypharmacology, selectivity, and molecular recognition principles. As public-private partnerships like EUbOPEN continue to expand the available chemogenomics toolbox [8], and computational methods become increasingly sophisticated [29], the systematic mapping of ligand-target interactions will play an increasingly central role in therapeutic development.

Chemogenomic Methods: From Library Design to Machine Learning Prediction

Designing Chemogenomic Libraries for Phenotypic and Target-Based Screening

Chemogenomics represents a systematic approach to understanding the interactions between small molecules and the products of the genome, with the ultimate goal of modulating biological function and discovering new therapies [31]. This field integrates chemistry, biology, and molecular informatics to establish, analyze, and expand a comprehensive ligand-target structure-activity relationship (SAR) matrix [31]. The design of chemogenomic libraries is fundamentally structured around the concept of target families—groups of proteins with structural similarities or related biological functions—enabling more efficient exploration of chemical space and facilitating the discovery of selective or promiscuous compounds.

The contemporary drug discovery paradigm has evolved from a reductionist "one target–one drug" vision toward a systems pharmacology perspective that acknowledges most drugs interact with multiple targets [32]. This shift is particularly relevant for complex diseases like cancer, neurological disorders, and diabetes, which often result from multiple molecular abnormalities rather than single defects [32]. Within this framework, chemogenomic libraries serve as essential tools for both phenotypic screening (which identifies compounds based on observable cellular effects) and target-based screening (which focuses on specific molecular targets), bridging the gap between compound discovery and target validation [33] [32].

Fundamental Principles of Chemogenomic Library Design

Key Design Objectives

Effective chemogenomic library design pursues several interconnected objectives. Diversity ensures coverage of a broad chemical space, increasing the probability of identifying hits against unexpected targets. Target Family Coverage focuses on representing compounds that interact with members of key protein families such as kinases, GPCRs, ion channels, and nuclear receptors. Structural Integrity guarantees that compounds have confirmed structures and purity, as error rates in public databases can reach 8% according to some analyses [34]. Bioactivity Relevance prioritizes molecules with demonstrated biological activity, typically sourced from established bioactivity databases like ChEMBL [32].

The cellular response to drug perturbation appears limited in scope, with research suggesting that chemogenomic responses can be categorized into a finite set of signatures. One comprehensive analysis of yeast chemogenomic datasets revealed that the cellular response to small molecules can be described by a network of just 45 chemogenomic signatures, with the majority (66.7%) conserved across independent datasets [33]. This finding underscores the importance of targeted library design that captures these fundamental response patterns.

Data Curation and Quality Control

Robust data curation is prerequisite for reliable chemogenomic library design. The integration of chemogenomic data from public repositories such as ChEMBL, PubChem, and PDSP is complicated by concerns about data quality and reproducibility [34]. Studies indicate that only 20-25% of published assertions concerning biological functions for novel deorphanized proteins are consistent with pharmaceutical companies' in-house findings, with one analysis at Amgen showing a reproducibility rate of just 11% [34].

An integrated chemical and biological data curation workflow should address both structural and bioactivity data quality [34]:

- Chemical Curation: Identification and correction of structural errors, removal of problematic compounds (inorganics, organometallics, mixtures), structural cleaning (detection of valence violations), ring aromatization, normalization of specific chemotypes, and standardization of tautomeric forms.

- Stereochemistry Verification: Confirmation of correct stereochemical assignments, particularly important for bioactive compounds with multiple asymmetric centers.

- Bioactivity Processing: Detection and resolution of chemical duplicates where the same compound appears multiple times with different bioactivity measurements, which can artificially skew QSAR model predictivity [34].

Table 1: Common Data Quality Issues in Chemogenomic Repositories

| Issue Category | Specific Problems | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structures | Erroneous structures (average 2 per publication); 8% error rate in some databases [34] | Incorrect structure-activity relationships; flawed model development |

| Bioactivity Data | Mean error of 0.44 pKi units with standard deviation of 0.54 pKi units [34] | Reduced reproducibility and translational potential |

| Experimental Variability | Differences in screening technologies (e.g., tip-based vs. acoustic dispensing) [34] | Inconsistent results across laboratories; compromised model performance |

| Annotation | Incomplete target and pathway associations | Limited mechanistic understanding |

Library Design Strategies for Different Screening Approaches

Target-Family Focused Libraries

Target-family focused libraries are constructed around specific protein families with shared structural features or functional characteristics. This approach leverages the concept that related targets often bind similar ligands, enabling knowledge transfer across a target class. Examples include kinase-focused libraries, GPCR-targeted collections, and ion channel-directed sets [32]. These libraries typically contain compounds with demonstrated activity against family members or structural features known to interact with conserved binding sites.

The construction of target-family libraries benefits from chemogenomic knowledgebases that integrate drug-target-pathway-disease relationships. One such approach utilizes a systems pharmacology network built using Neo4j graph database technology, incorporating data from ChEMBL, KEGG pathways, Gene Ontology, Disease Ontology, and morphological profiling data [32]. This network-based framework enables identification of proteins modulated by chemicals that correlate with specific phenotypic responses.

Phenotypic Screening Libraries

With the renewed interest in phenotypic drug discovery, specialized chemogenomic libraries optimized for phenotypic screening have emerged [32]. These libraries are designed to interrogate complex biological systems without preconceived notions about specific molecular targets, instead focusing on eliciting and measuring phenotypic changes.

Phenotypic screening libraries should encompass several key characteristics [32]:

- Target Diversity: Representation of a broad panel of drug targets involved in diverse biological processes and diseases

- Structural Diversity: Inclusion of diverse chemotypes and scaffolds to increase the probability of identifying novel bioactivities

- Polypharmacology Potential: Compounds with appropriate selectivity profiles that may simultaneously modulate multiple targets relevant to complex diseases

- Morphological Profiling Compatibility: Compatibility with high-content imaging technologies like Cell Painting that capture multidimensional phenotypic responses

One developed chemogenomic library of 5,000 small molecules was designed to represent a large panel of drug targets involved in diverse biological effects and diseases, with filtering based on scaffolds to ensure diversity while covering the druggable genome [32]. This library was integrated with a high-content image-based assay for morphological profiling, creating a platform for linking chemical perturbations to phenotypic outcomes.

Universal Chemogenomic Libraries

Universal chemogenomic libraries aim for comprehensive coverage of the druggable genome without specific focus on particular target families. These libraries typically incorporate several thousand compounds selected to maximize diversity and target coverage. The NIH's Mechanism Interrogation PlatE (MIPE) library and the GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Biologically Diverse Compound Set (BDCS) represent examples of such comprehensive collections [32].

Table 2: Comparison of Chemogenomic Library Design Strategies

| Library Type | Size Range | Primary Screening Application | Key Characteristics | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target-Family Focused | 1,000-5,000 compounds | Target-based screening | High specificity for protein family; enriched with known pharmacophores | Kinase libraries; GPCR collections; Ion channel sets |

| Phenotypic Screening | 5,000-30,000 compounds | Phenotypic profiling | Diverse target coverage; compatible with high-content assays; includes compounds with known MoA | Custom phenotypic libraries; Cell Painting-compatible sets |

| Universal Chemogenomic | 5,000-20,000 compounds | Both phenotypic and target-based screening | Maximum diversity; broad target coverage; includes annotated bioactivities | MIPE library; GSK BDCS; Pfizer chemogenomic library |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Chemogenomic Fitness Profiling

Chemogenomic fitness profiling represents a powerful approach for understanding genome-wide cellular responses to small molecules. The HaploInsufficiency Profiling and HOmozygous Profiling (HIP/HOP) platform employs barcoded heterozygous and homozygous yeast knockout collections to identify chemical-genetic interactions [33]. This methodology provides direct, unbiased identification of drug target candidates as well as genes required for drug resistance.

HIP/HOP Protocol Overview [33]:

- Strain Pool Preparation: Construction of pools of heterozygous and homozygous yeast knockout strains, with each strain containing unique molecular barcodes.

- Competitive Growth Assays: Cultivation of pooled strains in the presence of compounds versus vehicle control, typically with robotic sampling to ensure consistency.

- Barcode Sequencing: Quantification of strain abundance through sequencing of unique molecular barcodes.

- Fitness Defect Scoring: Calculation of Fitness Defect (FD) scores representing the relative abundance and drug sensitivity of each strain.

- Data Normalization: Application of robust statistical normalization to account for technical variability, including batch effects and tag-specific performance.

In the HIP assay, drug-induced haploinsufficiency identifies heterozygous strains deleted for one copy of essential genes that show heightened sensitivity to compounds targeting the gene product. The complementary HOP assay interrogates homozygous deletion strains to identify genes involved in the drug target biological pathway and those required for drug resistance [33]. The combined HIP/HOP chemogenomic profile provides a comprehensive genome-wide view of the cellular response to specific compounds.

High-Content Morphological Profiling

The Cell Painting assay provides a high-content imaging-based approach for phenotypic profiling that can be integrated with chemogenomic library screening [32]. This methodology enables the capture of multidimensional morphological features resulting from chemical perturbations.

Cell Painting Protocol [32]:

- Cell Preparation: Plating of appropriate cell lines (e.g., U2OS osteosarcoma cells) in multiwell plates.

- Compound Treatment: Perturbation with test compounds at relevant concentrations and exposure times.

- Staining: Application of multiplexed fluorescent dyes targeting various cellular compartments:

- Mitochondria

- Endoplasmic reticulum

- Nucleus

- Cytoplasm

- Actin cytoskeleton

- Image Acquisition: High-throughput microscopy using automated imaging systems.

- Image Analysis: Automated feature extraction using CellProfiler software, identifying individual cells and measuring morphological features (intensity, size, shape, texture, granularity, etc.).

- Profile Generation: Creation of morphological profiles representing the compound-induced phenotypic state.

The resulting morphological profiles enable comparison of phenotypic impacts across different compounds, grouping into functional pathways, and identification of disease signatures [32]. For a published dataset (BBBC022), 1,779 morphological features were measured across three cellular objects: cell, cytoplasm, and nucleus [32].

Network Pharmacology Integration

Advanced chemogenomic library design increasingly incorporates network pharmacology approaches that integrate heterogeneous data sources to build comprehensive drug-target-pathway-disease relationships [32].

Network Construction Methodology [32]:

- Data Collection: Integration of data from ChEMBL (bioactivities), KEGG (pathways), Gene Ontology (biological processes), Disease Ontology (disease associations), and morphological profiling.

- Scaffold Analysis: Deconstruction of molecules into representative scaffolds and fragments using tools like ScaffoldHunter, which applies deterministic rules to identify characteristic core structures.

- Graph Database Implementation: Construction of a network pharmacology database using Neo4j graph database technology, with nodes representing molecules, scaffolds, proteins, pathways, and diseases.

- Relationship Mapping: Establishment of edges between nodes representing biological relationships (e.g., molecule-target interactions, target-pathway associations).

- Enrichment Analysis: Application of clusterProfiler and DOSE R packages for GO, KEGG, and Disease Ontology enrichment analysis to identify statistically overrepresented biological concepts.