Target Deconvolution Strategies: Bridging Phenotypic Screening to Mechanistic Insight in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of target deconvolution, the essential process of identifying the molecular targets of bioactive compounds discovered through phenotypic screening.

Target Deconvolution Strategies: Bridging Phenotypic Screening to Mechanistic Insight in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of target deconvolution, the essential process of identifying the molecular targets of bioactive compounds discovered through phenotypic screening. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles driving the resurgence of phenotypic approaches, details the core methodologies from affinity-based proteomics to novel computational tools, and addresses key challenges in implementation. Furthermore, it examines validation strategies and compares the relative advantages of phenotypic and target-based discovery paradigms, offering a holistic guide for integrating these techniques to accelerate the development of first-in-class therapeutics.

The Renaissance of Phenotypic Screening and the Imperative for Target Deconvolution

The landscape of drug discovery has been historically shaped by two foundational strategies: phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) and target-based drug discovery (TDD). The former identifies compounds based on their observable effects in biologically relevant systems without requiring prior knowledge of the specific molecular target, while the latter begins with a predefined, validated molecular target and employs rational design to develop modulating compounds [1] [2]. After a period dominated by reductionist target-based approaches, the field has witnessed a resurgence of phenotypic screening, driven by analyses revealing that between 1999 and 2008, a majority of first-in-class medicines were discovered through phenotypic methods [2]. Furthermore, from 2012 to 2022, the application of PDD in large pharmaceutical portfolios grew from less than 10% to an estimated 25-40% [3]. This shift is largely attributable to PDD's ability to identify therapeutics with novel mechanisms of action for complex diseases, effectively expanding the "druggable target space" [2]. Modern drug discovery now increasingly embraces integrated workflows that leverage the strengths of both paradigms, accelerated by advancements in artificial intelligence, multi-omics technologies, and high-content screening [1]. This application note examines these complementary approaches within the critical context of target deconvolution, providing researchers with structured comparisons, detailed protocols, and strategic frameworks for implementation.

Comparative Analysis of Screening Approaches

Core Principles and Strategic Applications

The fundamental distinction between phenotypic and target-based screening lies in their starting point and underlying philosophy.

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) is defined by its focus on modulating a disease phenotype or biomarker in a realistic model system without a pre-specified target hypothesis [2]. This biology-first, empirical strategy is particularly valuable when the therapeutic goal is to discover first-in-class drugs with novel mechanisms of action, or when the underlying disease biology is too complex or poorly understood to pinpoint a single causal target [1] [2]. It captures the complexity of cellular systems and can reveal unanticipated biological interactions or polypharmacology [1].

Target-Based Drug Discovery (TDD) is a hypothesis-driven approach that begins with the selection of a specific molecular target—typically a protein—with a well-established or strongly postulated role in the disease pathogenesis [1]. This strategy relies on a reductionist understanding of disease mechanisms and is highly effective for optimizing drug selectivity and potency against known pathways, especially for follow-on or best-in-class drugs [1] [2].

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of Phenotypic and Target-Based Screening Paradigms

| Feature | Phenotypic Screening | Target-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Disease phenotype in a biologically relevant system (cell-based, tissue, or whole organism) [2] | Predefined molecular target (e.g., enzyme, receptor) [1] |

| Key Advantage | Identifies novel targets/mechanisms; captures system complexity and polypharmacology [1] [2] | Rational design; streamlined optimization; generally simpler target deconvolution [1] |

| Primary Challenge | Complex, often lengthy target identification/deconvolution [1] | Relies on imperfect or incomplete target validation; can suffer from lack of efficacy in clinic [1] [2] |

| Ideal Application | First-in-class drugs, complex/polygenic diseases, poorly understood pathways [2] | Best-in-class drugs, well-validated targets, "druggable" target classes [1] |

| Throughput | Often medium, due to complex assays | Typically high, amenable to automation |

Quantitative Success Metrics and Notable Drug Discoveries

The value of both strategies is ultimately demonstrated by their track record in delivering new medicines. Analysis of new FDA-approved treatments from 1999 to 2017 shows that PDD contributed to the development of 58 out of 171 total drugs, while traditional TDD accounted for 44 approvals [3]. PDD has been notably prolific in generating first-in-class medicines [2].

Table 2: Exemplary Drugs Discovered Through Phenotypic and Target-Based Approaches

| Drug Name | Discovery Paradigm | Indication | Key Target/Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risdiplam [2] [3] | Phenotypic | Spinal Muscular Atrophy | Modulates SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing [2] |

| Daclatasvir [2] [3] | Phenotypic | Hepatitis C | Targets HCV NS5A protein [3] |

| Ivacaftor/Lumacaftor [2] [3] | Phenotypic | Cystic Fibrosis | CFTR potentiator and corrector [2] |

| Lenalidomide [1] [2] | Phenotypic | Multiple Myeloma | Binds cereblon, degrades IKZF1/3 [1] |

| Vamorolone [3] | Phenotypic | Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy | Dissociative steroid, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist [3] |

| Imatinib [2] | Target-Based | Chronic Myeloid Leukemia | BCR-ABL kinase inhibitor [2] |

| Sunitinib [4] | Target-Based | Renal Cell Carcinoma | Multi-targeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor [4] |

| Bispecific Antibodies [1] | Target-Based | Various Cancers | Engages two different antigens (e.g., immune cells and tumor cells) [1] |

The Critical Role of Target Deconvolution in Phenotypic Screening

Target deconvolution—the process of identifying the molecular target(s) responsible for a compound's observed phenotypic effect—is a critical, often bottleneck, step in phenotypic screening workflows. While not always strictly required for drug approval, as demonstrated by the post-approval target elucidation of lenalidomide [2], it is highly valuable for understanding the mechanism of action (MoA), derisking safety profiles, and guiding subsequent optimization of lead compounds [2].

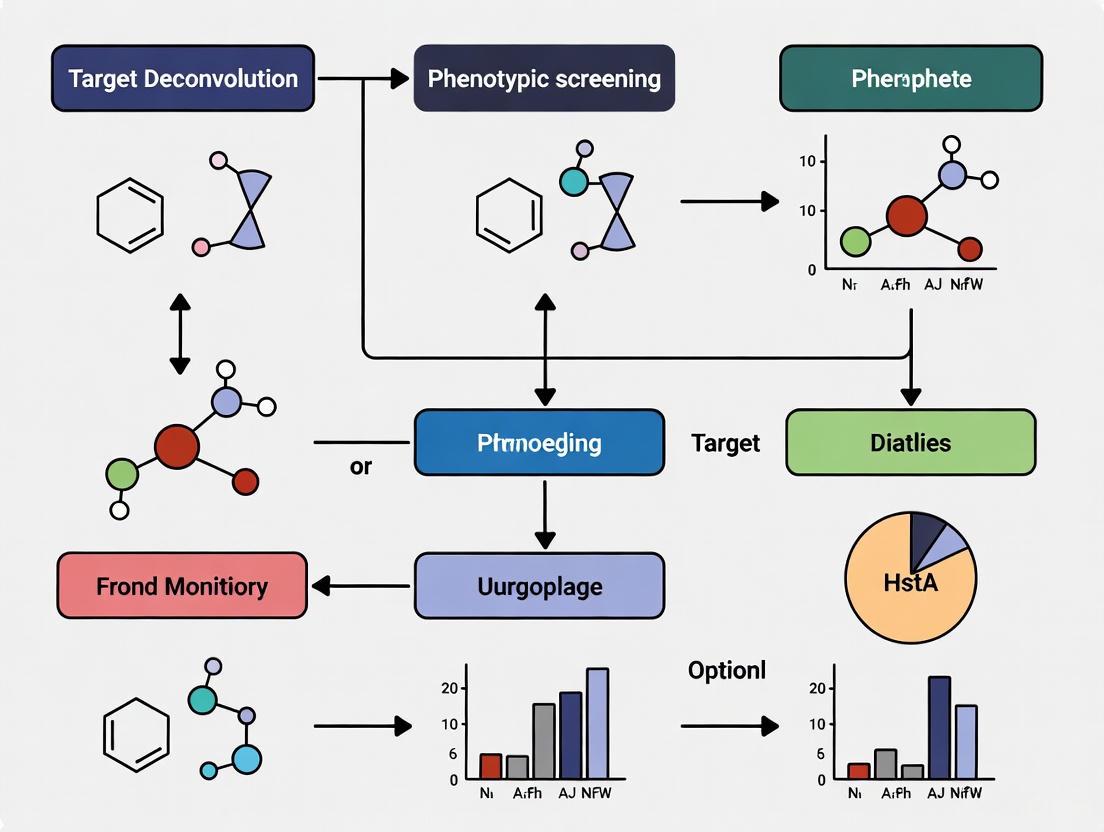

The following diagram illustrates the integrated modern drug discovery workflow, highlighting the central role of target deconvolution in bridging phenotypic and target-based paradigms.

Experimental Protocols for Target Deconvolution

Several methodologies have been established for target deconvolution. The choice of technique depends on the suspected nature of the target (e.g., protein, RNA), the available tools, and the project timeline.

Protocol 3.1.1: Affinity-Based Pull-Down and Proteomics

Purpose: To directly identify proteins that physically interact with a small molecule of interest [1]. Principle: A functionalized derivative of the hit compound (e.g., with a biotin tag) is synthesized and used as bait to capture binding proteins from a cell lysate. The captured protein complexes are then identified via mass spectrometry.

Materials:

- Functionalized compound (e.g., biotinylated)

- Streptavidin-coated beads

- Cell lysate from a relevant model system

- Lysis buffer (with protease/phosphatase inhibitors)

- Mass spectrometer (LC-MS/MS)

Procedure:

- Compound Immobilization: Incubate the functionalized compound with streptavidin-coated beads. Include a control with beads alone or an inactive analog.

- Lysate Preparation: Lyse cells and clarify the lysate by centrifugation.

- Pull-Down: Incubate the compound-bound beads with the cell lysate for 1-2 hours at 4°C.

- Washing: Wash the beads extensively with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute bound proteins using a competitive ligand (e.g., excess untagged compound) or by boiling in SDS-PAGE buffer.

- Analysis: Subject the eluted proteins to tryptic digestion and analysis by LC-MS/MS. Compare the results from the experimental sample to the control to identify specifically bound proteins.

- Validation: Confirm the interaction using orthogonal methods like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA).

Protocol 3.1.2: Functional Genomics for MoA Elucidation

Purpose: To identify genes whose loss-of-function (or gain-of-function) mimics or rescues the phenotypic effect of the compound. Principle: Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 knockout or RNAi screens are performed in the presence of a sub-lethal or sub-effective concentration of the compound. Genes whose perturbation alters cellular sensitivity to the drug are candidate targets or members of the same pathway.

Materials:

- Genome-wide CRISPR knockout or RNAi library

- Cells relevant to the phenotypic assay

- Viral packaging system (for lentiviral delivery)

- Puromycin or other selection agents

- Next-generation sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Library Transduction: Transduce cells with the CRISPR/RNAi library at a low MOI to ensure single guide RNA integration per cell.

- Selection: Select transduced cells with the appropriate antibiotic.

- Compound Challenge: Treat the library-containing cells with a sub-effective dose (IC10-IC20) of the compound. Maintain a DMSO-treated control arm in parallel.

- Harvesting: Harvest genomic DNA from both treated and control cells after 10-14 population doublings.

- Amplification & Sequencing: Amplify the integrated guide RNA sequences by PCR and subject them to next-generation sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify guide RNAs that are significantly enriched or depleted in the treated population compared to the control using specialized algorithms (e.g., MAGeCK). The genes targeted by these guides are high-priority candidates for the compound's MoA.

- Validation: Validate candidate genes using individual siRNA/shRNA or CRISPR constructs in the original phenotypic assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of integrated screening strategies requires a suite of reliable reagents and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Screening and Deconvolution

| Reagent / Tool Category | Example(s) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Target Prediction Software | MolTarPred [5], SwissTargetPrediction [4] | In silico prediction of potential protein targets for a small molecule, generating initial MoA hypotheses. |

| Genome-Editing Library | Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 knockout library [6] | Systematic loss-of-function screening to identify genes critical for compound activity. |

| Affinity Purification Tag | Biotin-Streptavidin System [1] | Immobilization of small molecule baits for direct pull-down of binding proteins from complex lysates. |

| Multi-Omics Profiling | Transcriptomics (e.g., Connectivity Map) [7], Proteomics | Generating global molecular signatures of drug action to infer MoA via pattern matching. |

| AI/ML Phenotypic Analysis | DrugReflector [7], High-Content Screening (HCS) AI platforms [3] | Automated analysis of complex phenotypic data (e.g., cell images) to predict bioactivity and MoA. |

The Rise of Integrated and Computational Approaches

The distinction between PDD and TDD is increasingly blurred by the adoption of hybrid workflows and powerful computational tools. A key integration point is the use of phenotypic assays to validate the functional effects of compounds initially identified through target-based design [1]. Conversely, phenotypic hits are now more rapidly characterized using in silico and multi-omics approaches.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are playing a transformative role. For instance, the DrugReflector framework uses a closed-loop active reinforcement learning process on transcriptomic data to improve the prediction of compounds that induce desired phenotypic changes, reportedly increasing hit rates by an order of magnitude compared to random library screening [7]. These AI tools are also enhancing the analysis of high-content screening data, extracting subtle morphological features to cluster phenotypes and predict MoA [3].

The following diagram illustrates how computational biology, particularly AI, integrates with and enhances both discovery paradigms.

The historical dichotomy between phenotypic and target-based drug discovery is evolving into a synergistic, integrated model. Phenotypic screening offers an unbiased path to first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms, as evidenced by breakthroughs in cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy, and oncology [2] [3]. Target-based discovery remains a powerful engine for developing highly specific, optimized therapies against validated pathways [1]. The critical bridge between these paradigms is effective target deconvolution, which transforms phenotypic observations into mechanistic understanding. As the field moves forward, the adoption of AI-driven tools [7] [8], functional genomics [6], and multi-omics integration [1] will continue to accelerate discovery cycles. For researchers, the strategic decision is no longer a binary choice but requires a thoughtful combination of both approaches, leveraging their complementary strengths to improve the efficiency and success of bringing new, impactful therapies to patients.

Why Target Deconvolution is the Critical Bridge from Phenotypic Hit to Viable Drug Candidate

Target deconvolution, the process of identifying the molecular targets of bioactive compounds, represents a pivotal stage in modern phenotypic drug discovery. This application note delineates the critical role of target deconvolution in transforming empirically-derived phenotypic hits into therapeutically viable drug candidates. We provide a comprehensive analysis of contemporary deconvolution strategies, detailed experimental protocols for key methodologies, and a curated toolkit of research solutions. By bridging the gap between observed phenotypic effects and understood molecular mechanisms, systematic target deconvolution significantly de-risks drug development and accelerates the translation of screening hits into clinically effective therapeutics.

Phenotypic drug discovery has experienced a significant resurgence as an alternative to purely target-based approaches, with evidence suggesting that compounds discovered through phenotypic techniques may be more efficiently translated into clinical innovations [9]. This paradigm shift acknowledges that complex biological contexts often reveal therapeutic effects that reductionist target-focused strategies might miss.

However, phenotypic screening presents a fundamental challenge: while it efficiently identifies compounds that produce desirable biological effects, it provides limited information about the specific molecular mechanisms through which these effects are mediated. This knowledge gap creates significant obstacles for downstream drug optimization, safety profiling, and clinical development. Target deconvolution directly addresses this limitation by identifying the precise molecular target(s) responsible for observed phenotypic responses [9] [10].

The critical importance of target deconvolution extends beyond mere mechanistic understanding. It enables researchers to:

- Guide medicinal chemistry efforts for compound optimization

- Identify potential safety liabilities through off-target profiling

- Discover polypharmacology that may contribute to efficacy

- Develop biomarkers for clinical development

- Reveal novel therapeutic targets for future drug discovery programs [10]

Experimental Approaches for Target Deconvolution

Multiple orthogonal methodologies have been developed for target deconvolution, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications. The most robust deconvolution strategies typically combine multiple complementary approaches to validate findings [10].

Affinity-Based Chemoproteomics

This "workhorse" technology involves modifying a compound of interest to create an immobilized bait that can capture binding proteins from biological samples [9].

Key Steps:

- Chemical Probe Design: The compound is modified with a functional handle (e.g., biotin) for immobilization without disrupting target binding

- Sample Preparation: Cell lysates or intact cellular systems are prepared under native conditions

- Affinity Enrichment: The immobilized bait captures direct binding partners from complex protein mixtures

- Target Identification: Captured proteins are eluted and identified via mass spectrometry

- Dose-Response Profiling: Quantitative measures (e.g., IC50 values) can be generated to characterize binding affinity [9]

This approach works well for a wide range of target classes but requires a high-affinity chemical probe that can be successfully immobilized without compromising target engagement [9].

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP)

ABPP employs bifunctional probes containing both a reactive group and a reporter tag to covalently label molecular targets based on their enzymatic activity [9].

Principal Variations:

- Direct Labeling: An electrophilic compound of interest is functionalized to directly label its binding targets

- Competitive ABPP: Samples are treated with a promiscuous electrophilic probe with and without the compound of interest; targets are identified as sites where probe occupancy is reduced by compound competition [9]

This approach is particularly powerful for profiling enzymes with conserved reactive residues but requires the presence of accessible reactive residues in target proteins [9].

Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL)

PAL utilizes trifunctional probes containing the compound of interest, a photoreactive moiety, and an enrichment handle to capture often transient drug-target interactions [9].

Mechanism of Action:

- The probe binds target proteins under physiological conditions

- UV exposure activates the photoreactive group, forming covalent bonds with neighboring target proteins

- The handle enables enrichment and identification of interacting proteins via mass spectrometry

PAL is particularly valuable for studying integral membrane proteins and identifying compound-protein interactions that may be too transient for detection by other methods [9].

Thermal Proteome Profiling (TPP)

TPP leverages the principle that drug binding often alters protein thermal stability, enabling proteome-wide identification of direct targets and downstream effects [11].

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Treatment: Cells or lysates are treated with compound or vehicle control

- Heat Gradients: Samples are subjected to a range of temperatures (e.g., 37-67°C)

- Soluble Protein Isolation: Heat-stable proteins remain soluble while denatured proteins precipitate

- Protein Quantification: Soluble proteins are quantified using multiplexed quantitative mass spectrometry

- Melting Curve Analysis: Shifted melting curves in compound-treated samples indicate potential target engagement [11]

Recent advances have improved TPP throughput and accessibility. Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) methods now provide cost-effective alternatives to traditional tandem mass tag (TMT) approaches, with library-free DIA-NN performing comparably to TMT-DDA in detecting target engagement [11]. Furthermore, the Matrix-Augmented Pooling Strategy (MAPS) enables concurrent testing of multiple drugs by mixing them in specific combinations followed by mathematical deconvolution, increasing experimental throughput by 60-fold compared to classic TPP [12].

Label-Free Target Deconvolution

Label-free strategies enable compound-protein interactions to be evaluated under native conditions without chemical modifications that might disrupt conformation or function [9].

Solvent-Induced Denaturation Shift Assays:

- Leverage changes in protein stability that occur with ligand binding

- Compare kinetics of physical or chemical denaturation before and after compound treatment

- Identify compound targets proteome-wide by detecting stabilization effects

- Particularly valuable for targets where probe modification is challenging [9]

Comparative Analysis of Deconvolution Methods

Table 1: Key Methodological Approaches for Target Deconvolution

| Method | Key Principle | Throughput | Sensitivity | Special Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity-Based Chemoproteomics | Immobilized compound captures binding proteins | Medium | High for abundant proteins | Broad target classes, dose-response profiling | Requires modifiable high-affinity probe |

| Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) | Reactive probes label active site residues | Medium-High | High for enzymes with reactive residues | Enzyme families, covalent inhibitors | Limited to proteins with reactive residues |

| Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) | Photoreactive groups capture transient interactions | Medium | Medium-High | Membrane proteins, transient interactions | Potential for non-specific labeling |

| Thermal Proteome Profiling (TPP) | Ligand binding alters protein thermal stability | Low-Medium (classic); High (MAPS) | Medium-High | Proteome-wide, direct and indirect targets | May miss targets without stability changes |

| Label-Free Methods | Native compound-protein interactions under physiological conditions | Medium | Variable | Native conditions, challenging targets | Can be challenging for low-abundance proteins |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Advanced TPP Methodologies

| Methodological Advance | Throughput Gain | Proteome Coverage | Cost Efficiency | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) | 2-3x vs. TMT-DDA | Comparable to TMT-DDA (library-free DIA-NN) | Significant improvement | Large-scale profiling, resource-limited settings |

| Matrix-Augmented Pooling Strategy (MAPS) | 60x vs. classic TPP; 15x vs. iTSA | Maintained with optimized pooling | Dramatic reduction in reagents and MS time | Multi-drug profiling, cell line comparisons |

| iTSA (single temperature) | 4x vs. classic TPP | Targeted to shifted proteins | High for focused studies | Rapid validation, high-throughput screening |

Research Reagent Solutions for Target Deconvolution

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Experimental Target Deconvolution

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Example Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| TargetScout | Affinity-based pull-down and profiling service | Commercial service for immobilized compound screening [9] |

| CysScout | Proteome-wide profiling of reactive cysteine residues | ABPP platform for cysteine-reactive compounds [9] |

| PhotoTargetScout | Photoaffinity labeling with optimization and identification modules | PAL service for membrane proteins and transient interactions [9] |

| SideScout | Proteome-wide protein stability assays | Label-free target deconvolution service [9] |

| Tandem Mass Tags (TMT) | Multiplexed protein quantification for thermal profiling | TMTpro 16-plex/18-plex for deep proteome coverage [11] |

| SISPROT | Sample preparation for multiplexed proteomics | Streamlined protocol for TMT-based experiments [12] |

Advanced Protocols: Thermal Proteome Profiling with MAPS

MAPS Experimental Workflow

The Matrix-Augmented Pooling Strategy revolutionizes thermal profiling by enabling concurrent assessment of multiple compounds through optimized sample pooling and computational deconvolution [12].

MAPS Experimental and Computational Workflow

Key Protocol Steps:

Sensing Matrix Design:

- Utilize a genetic algorithm to design an optimal binary sensing matrix (e.g., 9×15 for 15 drugs)

- Ensure each drug is represented in at least 3 sample pools

- Minimize correlation among drug mixtures to maximize information entropy [12]

Sample Preparation and Pooling:

- Prepare cell lysates or intact cells from relevant biological systems

- Add drugs to samples according to the sensing matrix design

- Include verification compounds with known targets as positive controls

- Consider structural diversity to minimize target overlap among pooled drugs [12]

Thermal Denaturation and Protein Processing:

- Subject pooled samples to a single denaturing temperature (optimized for the system)

- Separate soluble and insoluble fractions by centrifugation

- Digest soluble proteins and label with TMT reagents

- Pool labeled samples for multiplexed analysis [12]

Mass Spectrometry and Data Analysis:

- Perform LC-MS/MS analysis using high-resolution mass spectrometry

- Extract protein abundance values across samples

- Apply LASSO regression algorithm to deconvolve individual drug effects

- Compute LASSO paths and scores for each drug-protein pair

- Prioritize targets based on LASSO coefficients and statistical significance [12]

Critical Validation Steps for Deconvoluted Targets

Successful target deconvolution requires rigorous orthogonal validation to establish direct binding and functional relevance.

Orthogonal Validation Methods:

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Quantify binding affinity and kinetics in purified systems [11]

- Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA): Confirm target engagement in intact cellular environments [13]

- Functional Assays: Demonstrate that target modulation produces the observed phenotypic effect [10]

- Genetic Perturbation: Use CRISPRi/a or RNAi to validate target necessity for compound activity [10]

Case Study: Integrated Knowledge Graph and Experimental Approach

A recent innovative approach demonstrated the power of combining computational prediction with experimental validation for challenging target deconvolution problems, specifically for p53 pathway activators [14].

Integrated Workflow:

- Phenotypic Screening: Identify UNBS5162 as a p53 pathway activator using a high-throughput luciferase reporter system

- Knowledge Graph Construction: Build a protein-protein interaction knowledge graph (PPIKG) centered on p53 signaling

- Target Prioritization: Use PPIKG to narrow candidate targets from 1088 to 35 potential direct targets

- Molecular Docking: Perform virtual screening to identify USP7 as a high-probability target of UNBS5162

- Experimental Validation: Confirm USP7 binding and functional modulation through biochemical and cellular assays [14]

This integrated approach demonstrates how combining AI-driven target prediction with experimental validation can dramatically accelerate target deconvolution while reducing resource requirements.

Target deconvolution represents the essential bridge that connects empirically discovered phenotypic hits with mechanistically understood drug candidates. By employing the systematic approaches and detailed protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can effectively transform phenotypic screening outcomes into viable therapeutic development programs.

The future of target deconvolution lies in the intelligent integration of multiple orthogonal methods, leveraging the complementary strengths of chemoproteomic, biophysical, and computational approaches. Emerging technologies such as advanced mass spectrometry, CRISPR-based functional genomics, and artificial intelligence are rapidly expanding our capacity to resolve complex mechanisms of drug action across diverse biological contexts [15] [14] [16].

As these technologies mature, the field will increasingly move toward multi-dimensional deconvolution strategies that simultaneously map primary targets, off-target interactions, downstream pathway effects, and cell-type specific responses. This comprehensive understanding will ultimately enable more efficient development of safer and more effective therapeutics, fully realizing the promise of phenotypic drug discovery.

The Growing Pipeline of First-in-Class Drugs Originating from Phenotypic Approaches

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) has re-emerged as a powerful strategy for identifying first-in-class medicines, outperforming target-based approaches in generating pioneering therapies. By focusing on therapeutic effects in realistic disease models without a pre-specified molecular target hypothesis, PDD has expanded the "druggable" target space to include previously inaccessible cellular processes and mechanisms of action [2]. Between 1999 and 2008, a surprising majority of first-in-class drugs were discovered empirically without a target hypothesis, sparking renewed interest in modern phenotypic approaches that combine original concepts with contemporary tools and strategies [2]. This application note examines the growing pipeline of therapeutics originating from phenotypic screening, detailing key successes, experimental protocols for phenotypic screening and target deconvolution, and emerging technologies that enhance this productive discovery paradigm.

Recent Successes in Phenotypic Drug Discovery

Notable First-in-Class Therapies

Phenotypic screening has yielded numerous first-in-class therapies across diverse therapeutic areas, particularly for diseases with complex or poorly understood biology. These successes demonstrate PDD's unique ability to identify novel mechanisms and targets that would likely remain undiscovered through target-based approaches.

Table 1: Notable First-in-Class Drugs Discovered Through Phenotypic Screening

| Drug Name | Therapeutic Area | Molecular Target/Mechanism | Key Phenotypic Screen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ivacaftor, Tezacaftor, Elexacaftor [2] | Cystic Fibrosis | CFTR channel gating and folding correction | Cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants |

| Risdiplam, Branaplam [2] | Spinal Muscular Atrophy | SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing modulation | SMN2 splicing and SMN protein level assays |

| Lenalidomide, Pomalidomide [1] | Multiple Myeloma | Cereblon E3 ligase modulation (IKZF1/3 degradation) | TNF-α production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| Daclatasvir [2] | Hepatitis C | NS5A protein modulation (non-enzymatic target) | HCV replicon system |

| SEP-363856 [2] | Schizophrenia | Novel mechanism (target elucidated post-discovery) | Behavioral and neurochemical models |

| Crisaborole [2] | Atopic Dermatitis | Phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibition | Anti-inflammatory effects in cellular models |

Expansion of Druggable Target Space

PDD has significantly expanded the "druggable" target space to include unexpected cellular processes and novel target classes:

- Pre-mRNA splicing modulation: Risdiplam and branaplam stabilize the U1 snRNP complex to correct SMN2 splicing, an unprecedented drug target and mechanism [2]

- Pharmacological chaperones: Correctors such as tezacaftor and elexacaftor enhance the folding and plasma membrane insertion of misfolded CFTR proteins [2]

- Targeted protein degradation: Thalidomide analogs redirect cereblon substrate specificity to degrade specific transcription factors, pioneering the "molecular glue" concept [2]

- Non-enzymatic viral targets: Daclatasvir modulates NS5A, a HCV protein with no known enzymatic activity [2]

These successes demonstrate how phenotypic strategies reveal novel biology while delivering transformative therapies, particularly for diseases with unmet medical needs.

Experimental Protocols for Phenotypic Screening

Phenotypic Screening Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for phenotypic drug discovery, from assay development through lead optimization:

Protocol 1: High-Content Phenotypic Screening Using Cell Painting

Purpose: To identify compounds that induce biologically relevant phenotypic changes in disease models using high-content image-based profiling [17] [18].

Materials:

- Cell Line: U2OS osteosarcoma cells or disease-relevant primary cells

- Assay Kit: Cell Painting reagent kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

- Compounds: Diverse chemical library or focused collection

- Imaging Platform: High-content microscope (e.g., Yokogawa CQ1, ImageXpress)

- Analysis Software: CellProfiler, Deep Learning models (e.g., CNN, Vision Transformer)

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding and Treatment:

- Seed cells in 384-well plates at optimized density

- Treat with compounds at appropriate concentration (typically 1-10 μM) and time points

- Include appropriate controls (DMSO, positive/negative controls)

Staining and Fixation:

- Fix cells with 4% formaldehyde for 20 minutes

- Stain with Cell Painting cocktail:

- Mitochondria: MitoTracker Deep Red

- Nuclei: Hoechst 33342

- Endoplasmic reticulum: Concanavalin A, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate

- Golgi apparatus: Wheat Germ Agglutinin, Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate

- Actin cytoskeleton: Phalloidin, Alexa Fluor 647 conjugate

- Wash with PBS and seal plates

Image Acquisition:

- Acquire images using 20x or 40x objective

- Capture 9-25 fields per well to ensure adequate cell sampling

- Image all fluorescent channels

Feature Extraction and Analysis:

- Process images using CellProfiler to extract morphological features

- Generate ~1,500 morphological features per cell

- Apply machine learning for profile analysis and hit identification

- Use dimensionality reduction (t-SNE, UMAP) for visualization

Validation: Compare profiles to known reference compounds; assess reproducibility across replicates.

Protocol 2: Phenotypic Reporter Assay for Pathway Activation

Purpose: To identify compounds that modulate specific pathway activity using luciferase-based transcriptional reporters [14].

Materials:

- Reporter Cell Line: Stable cell line with pathway-specific response element driving luciferase expression

- Detection Reagent: Luciferase assay substrate (e.g., Steady-Glo, Bright-Glo)

- Compounds: Test compounds in DMSO

- Detection Platform: Plate reader capable of luminescence detection

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding:

- Seed reporter cells in white-walled 384-well plates

- Incubate for 24 hours to allow adherence

Compound Treatment:

- Treat cells with test compounds using automated liquid handling

- Include controls: DMSO (negative), pathway activator (positive)

- Incubate for appropriate time (typically 6-48 hours)

Luciferase Detection:

- Equilibrate plates to room temperature

- Add luciferase substrate according to manufacturer's protocol

- Incubate for 5-10 minutes to stabilize signal

- Measure luminescence using plate reader

Data Analysis:

- Normalize values to positive and negative controls

- Calculate Z'-factor for assay quality assessment

- Identify hits as compounds producing statistically significant activation

Validation: Confirm hits in secondary assays; dose-response analysis (EC50 determination).

Target Deconvolution Strategies

Target Deconvolution Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated approach for target deconvolution following phenotypic screening:

Protocol 3: Affinity-Based Chemoproteomics for Target Deconvolution

Purpose: To identify direct molecular targets of phenotypic hits using affinity enrichment and mass spectrometry [9] [19].

Materials:

- Chemical Probe: Phenotypic hit modified with affinity handle (biotin, alkyne, or photoaffinity group)

- Cell Lysate: Disease-relevant cell line or primary cells

- Affinity Matrix: Streptavidin beads (for biotinylated probes)

- Mass Spectrometry: LC-MS/MS system with high-resolution mass analyzer

Procedure:

- Probe Design and Synthesis:

- Derivatize hit compound with minimal modification to preserve activity

- Include negative control probe (inactive enantiomer or scrambled compound)

- Validate probe activity in phenotypic assay

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare cell lysates from relevant tissue or cell lines

- Incubate lysate with chemical probe (0.1-10 μM) for binding equilibrium

- For photoaffinity labeling: irradiate with UV light (365 nm) for crosslinking

Affinity Enrichment:

- Incubate probe-treated lysate with streptavidin beads

- Wash extensively with buffer to remove non-specific binders

- Elute bound proteins with Laemmli buffer or competitive elution

Protein Identification and Quantification:

- Digest proteins with trypsin

- Analyze peptides by LC-MS/MS

- Compare experimental samples to negative controls

- Identify significantly enriched proteins over controls

Validation: Confirm target engagement using cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA), siRNA knockdown, or biophysical methods.

Protocol 4: Knowledge Graph-Enhanced Target Identification

Purpose: To prioritize potential targets for phenotypic hits using protein-protein interaction knowledge graphs and computational analysis [14].

Materials:

- Knowledge Graph: Protein-protein interaction database (e.g., STRING, BioGRID)

- Computational Tools: Molecular docking software (AutoDock, Schrödinger)

- Data Integration Platform: Custom scripts for data analysis (Python/R)

Procedure:

- Knowledge Graph Construction:

- Compile protein-protein interactions for disease-relevant pathways

- Annotate with functional relationships and pathway information

- Incorporate genetic and chemical perturbation data

Candidate Target Prioritization:

- Input phenotypic screening data and pathway context

- Identify proteins central to relevant phenotypic networks

- Filter candidate targets based on network topology and druggability

Molecular Docking:

- Prepare protein structures from PDB or homology modeling

- Generate compound 3D structures and optimize geometry

- Perform flexible docking simulations

- Analyze binding poses and interaction energies

Experimental Triangulation:

- Test compound against prioritized targets in biochemical assays

- Use selective tool compounds to validate target-phenotype relationship

- Confirm functional effects of target engagement

Validation: Correlate compound activity with target expression; validate with genetic perturbation (CRISPR, RNAi).

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Phenotypic Screening and Target Deconvolution

| Reagent/Category | Supplier Examples | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Kits [17] | Thermo Fisher Scientific | High-content morphological profiling | Standardization across screens, batch effects |

| Affinity Purification Reagents [9] | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Sigma-Aldrich | Target identification via pull-down | Probe design, non-specific binding |

| Photoaffinity Labeling Probes [9] | Tocris, TargetMol | Covalent target capture | Photocrosslinking efficiency, probe reactivity |

| Selective Compound Libraries [19] | Selleckchem, MedChemExpress | Target hypothesis testing | Annotation quality, chemical diversity |

| CRISPR Screening Libraries [20] | Dharmacon, Sigma-Aldrich | Functional genomic validation | Coverage, efficiency, off-target effects |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms [9] | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bruker | Proteomic target identification | Sensitivity, resolution, quantification |

Discussion and Future Directions

The pipeline of first-in-class drugs originating from phenotypic approaches continues to grow, fueled by advances in disease modeling, profiling technologies, and target deconvolution strategies. Integration of phenotypic and target-based approaches represents the future of innovative drug discovery [1]. Key emerging trends include:

AI-Enhanced Predictive Modeling: Combining chemical structures with morphological and gene expression profiles improves bioactivity prediction, potentially increasing the number of predictable assays from 37% (chemical structures alone) to 64% when combined with phenotypic data [18]

Multi-Omic Integration: Combining functional genomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics with phenotypic data provides comprehensive systems-level understanding of compound mechanisms [1]

Advanced Disease Models: More physiologically relevant models including primary cells, co-cultures, and organoids increase the translational predictive power of phenotypic screens [2]

Hybrid Screening Approaches: Combining phenotypic screening with selective compound libraries facilitates preliminary target deconvolution while maintaining phenotypic relevance [19]

Despite these advances, challenges remain in phenotypic screening, including the limited coverage of chemogenomic libraries (interrogating only 1,000-2,000 of ~20,000 human genes) and the inherent difficulties in transitioning from phenotypic hits to target-optimized leads [20]. Continued innovation in experimental and computational methods will be essential to fully leverage the potential of phenotypic approaches for delivering transformative first-in-class medicines.

In modern drug discovery, elucidating the precise interactions between a small molecule and a biological system is paramount for developing effective and safe therapeutics. This document defines three pivotal concepts—Mechanism of Action (MoA), On-Target Interactions, and Off-Target Interactions—within the critical context of target deconvolution in phenotypic screening research. Phenotypic screening identifies compounds based on their ability to produce a desired change in a cell or organism, without prior knowledge of the specific molecular target[sitation:3]. The subsequent process of identifying the compound's molecular target(s) is known as target deconvolution[sitation:2][sitation:5]. Understanding whether the resulting phenotypic effects are driven by on-target or off-target interactions is a core objective of this process and is essential for lead optimization and human risk assessment[sitation:1].

Core Conceptual Definitions

Mechanism of Action (MoA)

The Mechanism of Action (MoA) describes the specific biochemical interaction through which a drug substance produces its pharmacological effect[sitation:4]. It typically includes mention of the specific molecular targets to which the drug binds, such as an enzyme or receptor, and the functional consequence of that binding (e.g., inhibition or activation)[sitation:4]. It is important to distinguish MoA from the related term "Mode of Action" (MoA), which describes the functional or anatomical changes at the cellular level that result from exposure to a substance[sitation:4].

On-Target Interactions

An on-target interaction refers to the desired, primary pharmacological effect that occurs when a drug binds to its intended molecular target[sitation:1]. However, the term "on-target" toxicity or side effect describes an adverse effect that arises from the drug binding to the intended target in healthy tissues, where its activity is not desired[sitation:1][sitation:7]. For example, skin rash is an on-target side effect observed with inhibitors of the MAP kinase pathway, as the target is present in both tumor and normal skin cells[sitation:7].

Off-Target Interactions

An off-target interaction occurs when a drug produces an adverse or unintended effect as a result of modulating biological targets that are unrelated to its primary intended target[sitation:1]. These effects are often unexpected and can be due to the compound's interaction with other proteins or a consequence of the drug's specific chemical structure[sitation:7]. Off-target interactions are a major source of compound toxicity and attrition in drug development.

Table 1: Summary and Comparison of Core Concepts

| Concept | Definition | Key Characteristics | Implication for Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action (MoA) | The specific biochemical interaction by which a drug produces its pharmacological effect[sitation:4]. | - Defines the molecular target- Describes the biochemical outcome (e.g., agonism, antagonism)- Distinct from "Mode of Action" | Enables rational drug design, patient stratification, and combination therapy strategies[sitation:4]. |

| On-Target Interaction | Interaction with the intended therapeutic target, or an adverse effect from modulating the intended target in normal tissues[sitation:1][sitation:7]. | - Primary desired pharmacologic effect- Can lead to mechanism-based toxicity- Effect is consistent with the target's known biology | Risk assessment involves understanding target expression and function in both diseased and healthy tissues[sitation:1]. |

| Off-Target Interaction | An adverse effect resulting from the modulation of biological targets unrelated to the primary therapeutic target[sitation:1][sitation:7]. | - Unintended and often unexpected- Can be predicted by comparing plasma concentration to off-target Ki[sitation:10]- Related to compound's polypharmacology | A major focus of safety pharmacology; requires thorough profiling to de-risk candidate compounds[sitation:10]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between a small molecule, its direct interactions, and the downstream effects that define its MoA and on/off-target profiles.

The Central Role in Phenotypic Screening and Target Deconvolution

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) is a strategy to identify substances that alter the phenotype of a cell or organism in a desired manner, without prior hypothesis about the molecular target[sitation:3]. A key limitation of this approach is that it provides little initial information on the compound's target or MoA[sitation:6]. Target deconvolution is the retrospective process of identifying the molecular target(s) that underlie the observed phenotypic response[sitation:2][sitation:5]. This process is crucial because:

- It bridges the gap between initial phenotypic hits and downstream lead optimization[sitation:5].

- It elucidates both on-target (therapeutic and toxic) and off-target (potentially toxic) interactions, informing human risk assessment[sitation:1].

- It can reveal novel biological targets and pathways for treating disease[sitation:6].

The following workflow maps the integrated process from phenotypic screening through target deconvolution and mechanistic validation.

Experimental Protocols for Target Identification and Validation

A broad panel of experimental strategies can be applied for target deconvolution[sitation:2]. The choice of method depends on the properties of the small molecule and the biological system[sitation:5]. Below are detailed protocols for key methodologies.

Affinity-Based Pull-Down and Mass Spectrometry

This "workhorse" method uses an immobilized version of the compound to capture and identify binding proteins directly from a complex biological mixture [21] [9].

Detailed Protocol:

- Probe Synthesis: Modify the compound of interest to include a linker and an affinity handle (e.g., biotin) or a solid support for immobilization. A cleavable linker is recommended for gentle elution [9].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a cell lysate from a disease-relevant cell line. Include protease and phosphatase inhibitors to maintain protein integrity. Pre-clear the lysate with bare beads to reduce non-specific binding.

- Affinity Enrichment: Incubate the cell lysate with the immobilized compound (the "bait"). Typically, this is performed for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation. A control sample (e.g., with bare beads or an inactive analog) must be run in parallel.

- Wash: Wash the beads extensively with a non-denaturing buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.1% Tween-20) to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute the bound proteins. This can be achieved by:

- Competitive Elution: Incubating with excess free compound of interest.

- Denaturing Elution: Using a low-pH buffer or SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

- On-Bead Digestion: Directly digesting the proteins while still on the beads.

- Protein Identification: Subject the eluted proteins to tryptic digestion and analysis by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Identify proteins by searching the resulting spectra against a protein sequence database.

- Data Analysis: Compare the list of proteins from the compound pull-down to the control pull-down. Specific binders are significantly enriched in the compound sample. Dose-response profiles and IC₅₀ values can be generated by performing the pull-down in the presence of increasing concentrations of free compound [9].

Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL)

PAL is particularly useful for studying integral membrane proteins and transient compound-protein interactions that may be difficult to capture with standard affinity methods [9].

Detailed Protocol:

- Probe Design and Synthesis: Synthesize a trifunctional probe containing:

- The small molecule of interest.

- A photoreactive moiety (e.g., aryl azide, diazirine).

- An enrichment handle (e.g., alkyne for subsequent "click chemistry" conjugation to biotin).

- Cell Treatment and Cross-Linking: Treat living cells or cell lysates with the photoaffinity probe. Allow the probe to bind its cellular targets under physiological conditions. Subsequently, expose the sample to UV light (at a wavelength specific to the photoreactive group) to activate it and form a covalent bond between the probe and its target protein(s).

- Cell Lysis and "Click" Chemistry: Lyse the cells. If the enrichment handle is an alkyne, perform a copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition ("click reaction") with a biotin-azide tag to conjugate biotin to the captured proteins.

- Streptavidin Pull-Down: Incubate the biotinylated protein mixture with streptavidin-coated beads to isolate the covalently tagged protein complexes.

- Wash and Elution: Wash the beads stringently to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute the captured proteins by boiling in SDS-PAGE buffer or via other denaturing conditions.

- Target Identification: Analyze the eluate by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting or by in-gel digestion followed by LC-MS/MS for protein identification.

Label-Free Target Deconvolution: Thermal Protein Profiling

This method identifies compound targets by measuring ligand-induced changes in protein thermal stability without requiring chemical modification of the compound [9].

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Treatment: Divide a cell lysate into two aliquots. Treat one with the compound of interest (or vehicle control) for a sufficient time to allow binding.

- Heat Denaturation: Divide each treated lysate into multiple aliquots and heat each to a different temperature (e.g., ranging from 37°C to 67°C) for a fixed time (e.g., 3 minutes).

- Solubility Separation: Centrifuge the heated samples to separate the soluble (non-denatured) protein fraction from the insoluble (aggregated) fraction.

- Proteomic Analysis: Digest the soluble protein fractions from all temperature points for both compound-treated and control samples and analyze them by LC-MS/MS using a label-free quantitation method.

- Data Analysis and Target Identification: For each protein, plot the soluble amount against the temperature to generate a melting curve. A ligand-induced shift in a protein's melting curve (i.e., thermal stability) is a strong indicator of direct binding. Proteins that are stabilized (shift to a higher melting temperature) in the compound-treated sample are considered potential direct targets.

Table 2: Summary of Key Target Deconvolution Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Requirement | Strengths | Common Readout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Pull-Down [21] [9] | Immobilized compound captures binding proteins from lysate. | High-affinity chemical probe that can be immobilized. | - Workhorse method- Provides dose-response data [9]- Wide target class applicability | LC-MS/MS |

| Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) [9] | Photoreactive probe covalently cross-links to targets in live cells or lysate. | Trifunctional probe with photoreactive group and handle. | - Captures transient interactions- Ideal for membrane proteins [9] | LC-MS/MS, Western Blot |

| Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) [9] | Bifunctional probe with reactive group covalently labels target enzyme families. | Reactive residue in accessible region of target protein. | - Directly reports on functional state- Can map binding sites | LC-MS/MS |

| Label-Free (Thermal Profiling) [9] | Ligand binding alters protein thermal stability. | No compound modification needed. | - Studies native interactions- No chemical synthesis required | LC-MS/MS, Thermal Melt Curves |

| Genomic Profiling (CRISPR/siRNA) [22] | Genetic perturbation identifies genes that abolish compound effect. | Functional genomic tools (e.g., CRISPR library). | - Functional validation built-in- Identifies pathway dependencies | Phenotypic Rescue, Next-Gen Sequencing |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful target deconvolution relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below lists essential materials and their functions in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Target Deconvolution

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Biotin-Azide / Alkyne Handles | Serve as affinity handles for "click chemistry" conjugation, enabling pulldown and visualization of target proteins in affinity-based and PAL methods [9]. |

| Photoreactive Groups (e.g., Diazirines, Aryl Azides) | Incorporated into photoaffinity probes; upon UV exposure, these groups generate highly reactive carbenes or nitrenes that form covalent bonds with nearby target proteins [9]. |

| Streptavidin-Coated Magnetic Beads | Used for the highly specific capture and purification of biotin-tagged protein complexes in affinity enrichment and PAL workflows [9]. |

| Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC) | A quantitative proteomics method that uses isotopic labeling to accurately compare protein abundance between compound-treated and control samples, distinguishing specific binders from background [22]. |

| CRISPR/siRNA Knockdown Libraries | Tools for functional genomics used in genetic modifier screening to identify genes whose loss abolishes or enhances the compound's phenotypic effect, validating target engagement and pathway context [22]. |

| Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) | Bifunctional chemical probes containing a reactive group that covalently labels the active site of enzyme families (e.g., kinases, proteases), used in ABPP for functional proteomics [9]. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | The core analytical platform for identifying proteins from complex mixtures. It separates peptides by liquid chromatography and identifies them by mass spectrometry and database searching [21] [9]. |

Case Study: Deconvolution of a Chondrocyte Differentiation Inducer

A seminal study demonstrates the power of combining phenotypic screening with modern MoA elucidation [22]. Researchers screened primary human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) using an image-based assay to identify compounds that induce chondrocyte differentiation, a potential therapy for osteoarthritis. The small molecule Kartogenin (KGN) was identified as a potent hit.

To determine its MoA, the team:

- Synthesized a Photoaffinity Probe: Created a KGN analog with a biotin tag and a phenyl azide photo-crosslinker.

- Identified the Target Protein: After treating cells, UV cross-linking, and streptavidin pull-down, they identified the protein Filamin A (FLNA) as the primary binding target.

- Validated the Target and Pathway: Knockdown of FLNA via shRNA recapitulated the chondrocyte differentiation phenotype. Further investigation revealed that KGN binding to FLNA disrupts its interaction with the transcription factor co-regulator CBFβ, causing CBFβ to translocate to the nucleus and activate RUNX-family transcription drivers of chondrogenesis.

This case highlights a complete workflow: from a therapeutically inspired phenotypic screen, through target deconvolution via affinity methods, to the validation of a novel on-target mechanism involving the disruption of a specific protein-protein interaction.

A Practical Guide to Modern Target Deconvolution Techniques and Technologies

Affinity-based chemoproteomics has established itself as a foundational methodology in modern phenotypic screening research, serving as the critical link between observed biological effects and their underlying molecular mechanisms. In target-based drug discovery, researchers begin with a known molecular target, while phenotypic drug discovery identifies compounds based on a desired biological response in cells or organisms, requiring subsequent target deconvolution to identify the specific proteins responsible for the observed phenotype [9]. As a core component of chemoproteomics, affinity-based protein profiling (ABPP) enables the systematic and unbiased determination of protein interaction profiles for bioactive small molecules, providing a powerful strategy for comprehensive target identification [23] [24]. By leveraging affinity chromatography with immobilized bioactive compounds, researchers can capture protein targets directly from complex biological systems, followed by identification through advanced mass spectrometry techniques [25]. This approach has become indispensable for validating compound mechanisms, identifying off-target interactions, and accelerating the development of novel therapeutics, particularly for challenging target classes that have historically been difficult to study using conventional methods [23].

Principles and Methodological Framework

Core Components of Affinity-Based Workflows

Affinity-based chemoproteomics relies on the strategic design of chemical probes that retain the biological activity of the parent compound while incorporating functionality for target capture and identification. These probes typically consist of three key elements: the bioactive small molecule responsible for specific protein binding, a spacer or linker region that minimizes steric interference, and an enrichment handle such as biotin or an alkyne for conjugation to solid supports or fluorescent tags [24] [26]. The fundamental principle involves incubating these functionalized probes with biological samples—including cell lysates, intact cells, or tissue extracts—to allow formation of compound-protein complexes, followed by affinity enrichment and subsequent protein identification via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [25].

A significant challenge in these workflows is that immobilized molecules on solid supports frequently exhibit reduced affinity for their target proteins compared to the free parent compounds, potentially leading to failure in capturing specific targets or unacceptable losses during washing steps [26]. To circumvent this limitation, innovative approaches such as small molecule-peptide conjugates (SMPCs) have been developed, enabling more efficient capturing of protein targets from both cell lysates and intact cells while preserving functional activity [26].

Quantitative Proteomics and Experimental Design

Robust target identification requires careful experimental design incorporating appropriate controls and quantitative proteomics strategies to distinguish specific binding partners from non-specific interactions. Competitive binding experiments using excess parent compound alongside the probe enable researchers to identify proteins that show reduced binding in the presence of the competitor, indicating specific, saturable interactions [23]. Modern quantitative approaches employ isobaric mass tags (TMT), stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC), or label-free quantification to accurately compare protein enrichment across experimental conditions [24].

Recent advances in quantitative ABPP methods have significantly enhanced throughput and precision. Tandem mass tag (TMT/TMTpro) approaches now enable simultaneous analysis of up to 35 samples in a single LC-MS/MS run, while streamlined workflows like SLC-ABPP incorporate iodoacetamide-based probes with post-proteolysis TMT labeling for comprehensive cysteine profiling [24]. For improved quantitative accuracy at the protein level, sCIP (silane-based cleavable isotopically labeled proteomics) employs a dialkoxydiphenylsilane acid-cleavable linker that incorporates stable isotopes early in the process, allowing sample pooling immediately after labeling and reducing variability [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Affinity Pull-Down with Immobilized Compound

This foundational protocol describes the standard workflow for target identification using small molecules immobilized on solid supports, suitable for initial target discovery and validation [25].

Materials

- Bioactive compound with known phenotypic activity

- Control compound (structurally similar but inactive)

- Agarose resin (e.g., NHS-activated Sepharose)

- Lysis buffer: 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, protease inhibitors

- Wash buffer: 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40

- Elution buffer: 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer or 2 M urea/100 mM glycine (pH 2.5)

- Pre-cleared cell lysate (1-5 mg/mL total protein)

- SDS-PAGE and Western blot equipment

- Mass spectrometry system (LC-MS/MS)

Procedure

Compound Immobilization

- Covalently conjugate the bioactive compound to NHS-activated agarose resin according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Prepare control resin with inactive compound using identical chemistry.

- Block remaining active groups with ethanolamine (1 M, pH 8.0) for 2 hours.

- Wash resins extensively with alternating pH buffers (0.1 M acetate/0.5 M NaCl, pH 4.0 followed by 0.1 M Tris/0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.0).

Affinity Purification

- Incubate immobilized compound resin (50 μL bed volume) with 1 mg of pre-cleared cell lysate for 2 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation.

- Perform parallel incubation with control resin.

- Pellet resin by gentle centrifugation (500 × g, 2 minutes) and remove supernatant.

- Wash resin sequentially with 10 bed volumes of:

- Wash buffer

- High-salt wash buffer (wash buffer + 500 mM NaCl)

- Low-salt wash buffer (wash buffer without NaCl)

Target Elution and Analysis

- Elute bound proteins with 2 bed volumes of SDS-PAGE loading buffer (95°C, 5 minutes) or low-pH elution buffer.

- For mass spectrometry analysis, separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and perform in-gel tryptic digestion.

- For specific detection, analyze eluates by Western blotting if candidate targets are known.

- Identify proteins by LC-MS/MS and database searching (e.g., MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer).

Data Analysis

- Compare protein identification between bioactive and control pull-downs.

- Prioritize proteins enriched in bioactive compound samples.

- Validate specific binding through orthogonal approaches (cellular thermal shift assay, surface plasmon resonance).

Protocol 2: Photoaffinity Labeling-Based Chemoproteomics

Photoaffinity labeling (PAL) represents a more advanced strategy that captures transient and low-affinity interactions in live cells, making it particularly valuable for membrane proteins and dynamic complexes [23] [24].

Materials

- Photoactivatable probe (diazirine or aryl azide-containing)

- UV light source (365 nm, 0.5-5 J/cm²)

- Click chemistry reagents: CuSO₄, THPTA, sodium ascorbate

- Biotin-azide or fluorescent azide

- Streptavidin beads

- Lysis buffer (as above, but without primary amines if using click chemistry)

- Mass spectrometry-compatible detergents (e.g., SDS, DOC)

Procedure

Live Cell Labeling

- Treat intact cells with photoactivatable probe (1 nM-10 μM) for predetermined time (typically 30 minutes to 2 hours) in culture medium.

- Include control samples with excess parent compound (100×) to compete specific binding.

- Wash cells with cold PBS and irradiate with UV light (365 nm, 1-5 minutes, 4°C) to activate crosslinking.

- Harvest cells by scraping or trypsinization.

Sample Processing and Enrichment

- Lyse cells in lysis buffer with sonication or passage through narrow-gauge needle.

- Perform copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) with biotin-azide:

- Add final concentrations: 100 μM biotin-azide, 1 mM CuSO₄, 100 μM THPTA, 1 mM sodium ascorbate

- React for 1 hour at room temperature with rotation

- Pre-clear lysate with control beads (30 minutes, 4°C)

- Incubate with streptavidin beads (2 hours, 4°C)

- Wash beads stringently as in Protocol 1

On-Bead Digestion and MS Analysis

- Wash beads with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate

- Reduce proteins with 5 mM DTT (30 minutes, 56°C)

- Alkylate with 10 mM iodoacetamide (30 minutes, room temperature, dark)

- Digest with trypsin (1:50 w/w, overnight, 37°C)

- Acidify with trifluoroacetic acid (0.5% final) and desalt peptides using C18 stage tips

- Analyze by LC-MS/MS

Data Processing and Target Validation

- Process raw files using standard proteomics software

- Normalize protein intensities and calculate enrichment ratios (probe/control)

- Perform statistical analysis (t-tests, ANOVA) to identify significantly enriched proteins

- Validate top candidates through cellular assays (siRNA, functional rescue) [25]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Affinity-Based Chemoproteomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Key Functions | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Supports | NHS-activated Sepharose, Streptavidin Beads | Compound immobilization, target enrichment | NHS chemistry for amine coupling; streptavidin for biotinylated probes [26] [25] |

| Photoactivatable Groups | Diazirines, Aryl Azides | UV-induced covalent crosslinking to proteins | Diazirines offer smaller size and broader reactivity; aryl azides require higher energy UV [27] [24] |

| Bioorthogonal Handles | Alkyne, Azide, Biotin | Enrichment and detection | Enable click chemistry conjugation to tags after binding [27] [24] |

| Mass Tags | TMTpro, SILAC, DiGly | Multiplexed quantification | TMTpro allows 16-plex analysis; SILAC for metabolic labeling [24] |

| Protease Systems | Trypsin, Lys-C | Protein digestion for MS | Generate peptides suitable for LC-MS/MS analysis [24] |

Table 2: Key Small Molecule Probe Designs and Their Applications

| Probe Type | Structural Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Directly Immobilized | Compound linked to solid support via covalent bond | Simple design, cost-effective | Potential loss of binding affinity, accessibility issues [26] |

| Small Molecule-Peptide Conjugate (SMPC) | Compound linked to customized peptide sequence | Preserves functional activity, enables live-cell application | More complex synthesis, potential immunogenicity [26] |

| Photoaffinity Probe | Compound with photoreactive group and enrichment handle | Captures transient interactions, works in live cells | Requires UV irradiation, potential non-specific labeling [27] [23] |

| Branched Design | Multiple functional groups on branched linker | Enhanced presentation to targets, improved capture | Larger size may affect cell permeability [27] |

Case Study: Target Profiling of MDM2 Inhibitor Navtemadlin

A recent implementation of affinity-based protein profiling demonstrates the power of this approach for characterizing clinical-stage therapeutics. Researchers developed photoactivatable clickable probes of Navtemadlin, a potent MDM2 inhibitor currently in Phase III clinical trials, to comprehensively map its cellular target engagement and selectivity [27].

Probe Design and Validation

Two distinct probe designs were synthesized, both incorporating a diazirine photoactivatable group and an alkyne handle for subsequent conjugation, but differing in their linker architecture—probe 1 featured a linear tag while probe 2 incorporated a branched design [27]. Competitive fluorescence anisotropy binding assays confirmed that both probes maintained sub-micromolar binding affinity for MDM2, albeit with a 4-fold and 10-fold reduction compared to the parent Navtemadlin for probes 1 and 2, respectively [27]. Critically, both probes retained the phenotypic activity of Navtemadlin, demonstrated by dose-dependent upregulation of p53-downstream proteins p21 and MDM2 in SJSA-1 and MCF-7 cell lines [27].

Cellular Target Identification

Application of these probes in ABPP experiments enabled robust identification of MDM2 as the primary cellular target across multiple cell lines [27]. The consistency of MDM2 engagement across different probe designs and cellular contexts reinforced Navtemadlin's high selectivity for its intended target. While some off-targets were detected, their inconsistent appearance across cell lines and probe designs suggested they likely represented non-specific interactions rather than biologically relevant off-target binding [27]. Whole proteome profiling at different time points further confirmed the expected p53-mediated phenotypic activity and revealed novel expression patterns for key proteins in the p53 pathway, providing a systems-level view of drug mechanism [27].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Effective analysis of affinity-based chemoproteomics data requires rigorous statistical approaches to distinguish true binding partners from background interactions. The following table outlines key analytical considerations:

Table 3: Data Analysis Framework for Affinity-Based Chemoproteomics

| Analytical Step | Key Parameters | Best Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Identification | Peptide spectral matches, false discovery rate (FDR) | Use target-decoy approach with 1% FDR cutoff; require ≥2 unique peptides per protein [24] |

| Quantification | Enrichment ratios, significance testing | Calculate fold-change (probe/control); apply moderated t-tests with multiple testing correction [24] |

| Specificity Assessment | Competition profile, dose-response | Prioritize targets showing saturable competition with parent compound [23] |

| Functional Annotation | Gene ontology, pathway enrichment | Use DAVID, GeneOntology for biological process mapping; KEGG for pathway analysis [27] |

| Validation Prioritization | Abundance, phenotypic correlation | Focus on targets expressed in relevant cells/tissues; consistent with observed phenotype [25] |

Integration with Phenotypic Screening Workflows

Affinity-based chemoproteomics serves as the crucial bridge between phenotypic screening and mechanistic understanding in modern drug discovery. The strategic placement of this methodology within a comprehensive phenotypic screening framework is illustrated below:

This workflow demonstrates how affinity-based chemoproteomics enables the transition from phenotypic observations to target-driven optimization, forming the core of modern drug discovery pipelines.

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Successful implementation of affinity-based chemoproteomics requires careful attention to potential technical challenges. Common issues include non-specific binding to solid supports, inadequate blocking of immobilization resins, insufficient washing stringency leading to high background, and loss of weak interactions during processing. Optimization should include titration of probe concentrations, evaluation of different blocking agents (BSA, casein, ethanolamine), and adjustment of wash buffer stringency based on target affinity [26]. For photoaffinity labeling approaches, UV dose optimization is critical to balance crosslinking efficiency against protein damage, and control experiments with excess parent compound are essential to distinguish specific from non-specific labeling [23].

Recent innovations address several historical limitations of affinity-based approaches. Small molecule-peptide conjugates (SMPCs) circumvent the affinity loss often observed with direct solid-support immobilization, while advanced quantitative workflows like sCIP-TMT merge custom capture reagents with commercially available TMT tags to enhance multiplexing capabilities without extensive custom synthesis [24] [26]. The integration of advanced separation technologies such as high-field asymmetric ion mobility spectrometry (FAIMS) further improves quantitative accuracy by effectively filtering interfering ions [24].

Affinity-based chemoproteomics has evolved into a sophisticated, indispensable platform for target deconvolution in phenotypic screening research. By enabling direct capture and identification of protein targets within biologically relevant systems, this methodology provides critical mechanistic insights that drive rational drug optimization. The continuing development of more sensitive probes, advanced quantitative mass spectrometry, and innovative enrichment strategies will further expand the applications of affinity-based chemoproteomics, solidifying its role as the workhorse of pull-down and profiling assays in modern drug discovery.

In the modern phenotypic drug discovery pipeline, identifying the molecular target of a bioactive compound—a process known as target deconvolution—remains a significant challenge [9]. Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) has emerged as a powerful functional proteomic technology that directly addresses this challenge by enabling the selective profiling of enzyme activities within complex proteomes [28] [29]. Unlike conventional methods that measure protein abundance, ABPP uses designed chemical probes to report directly on functional state of enzymes, categorically distinguishing active enzymes from their inactive forms [28] [30]. This capability is particularly valuable for profiling enzyme classes like hydrolases and proteases, which are often regulated by endogenous inhibitors and post-translational modifications, making them prominent targets in disease research [30] [31].

ABPP operates at the intersection of chemistry and proteomics, utilizing small molecule probes that covalently bind to the active sites of mechanistically related classes of enzymes [30]. Since its inception in the 1990s, the technology has evolved from a qualitative tool for studying specific enzyme families to a versatile, quantitative platform integral to drug discovery and development [28] [32] [29]. By directly interrogating the functional pockets of proteins, ABPP facilitates the identification of therapeutic targets, the discovery of highly selective inhibitors, and the validation of drug mechanism of action, thereby accelerating the translation of phenotypic hits into viable drug candidates [28] [9].

Fundamental Principles of ABPP

Core Components of Activity-Based Probes

The efficacy of ABPP hinges on the rational design of activity-based probes (ABPs), which typically consist of three fundamental components:

- Reactive Group (Warhead): This is an electrophilic moiety designed to covalently bind to nucleophilic residues (e.g., serine, cysteine) in the enzyme's active site [28] [29]. The warhead determines the scope of enzyme classes the probe can target. For instance, fluorophosphonate (FP) warheads are broadly reactive against serine hydrolases, while other warheads target cysteine proteases or metalloproteases [32] [30].

- Linker Region: A spacer that connects the reactive group to the reporter tag. The linker modulates the reactivity and specificity of the probe, and its length and composition can be optimized to reduce steric hindrance, enhancing access to the enzyme's active site [28] [29].

- Reporter Tag: This group enables the detection, enrichment, and identification of probe-labeled proteins. Common tags include fluorophores (e.g., for in-gel fluorescence scanning), biotin (for affinity enrichment), or small bio-orthogonal handles like alkynes or azides [28]. The use of small bio-orthogonal groups enables a two-step labeling strategy via "click chemistry," which improves cell permeability and allows for greater experimental flexibility [28] [29].

Probe Design Strategies: ABPs vs. AfBPs

ABPP strategies primarily employ two classes of probes, which differ in their mechanism of selectivity:

- Activity-Based Probes (ABPs): These probes rely on the intrinsic catalytic mechanism of an enzyme class for selectivity. The warhead is designed to irreversibly label conserved active-site nucleophiles, making ABPs ideal for profiling entire families of enzymes, such as the serine hydrolases, without requiring prior knowledge of individual members [28] [32].

- Affinity-Based Probes (AfBPs): These probes utilize a high-affinity recognition motif for a specific protein, coupled with a photo-affinity group (e.g., benzophenone, diazirine) that forms a covalent bond upon UV irradiation [28] [31]. AfBPs are particularly useful for targeting proteins that lack a catalytic nucleophile or for studying specific, known protein-ligand interactions [28].