Strategic Chemogenomic Library Selection: Principles and Practices for Accelerated Drug Discovery

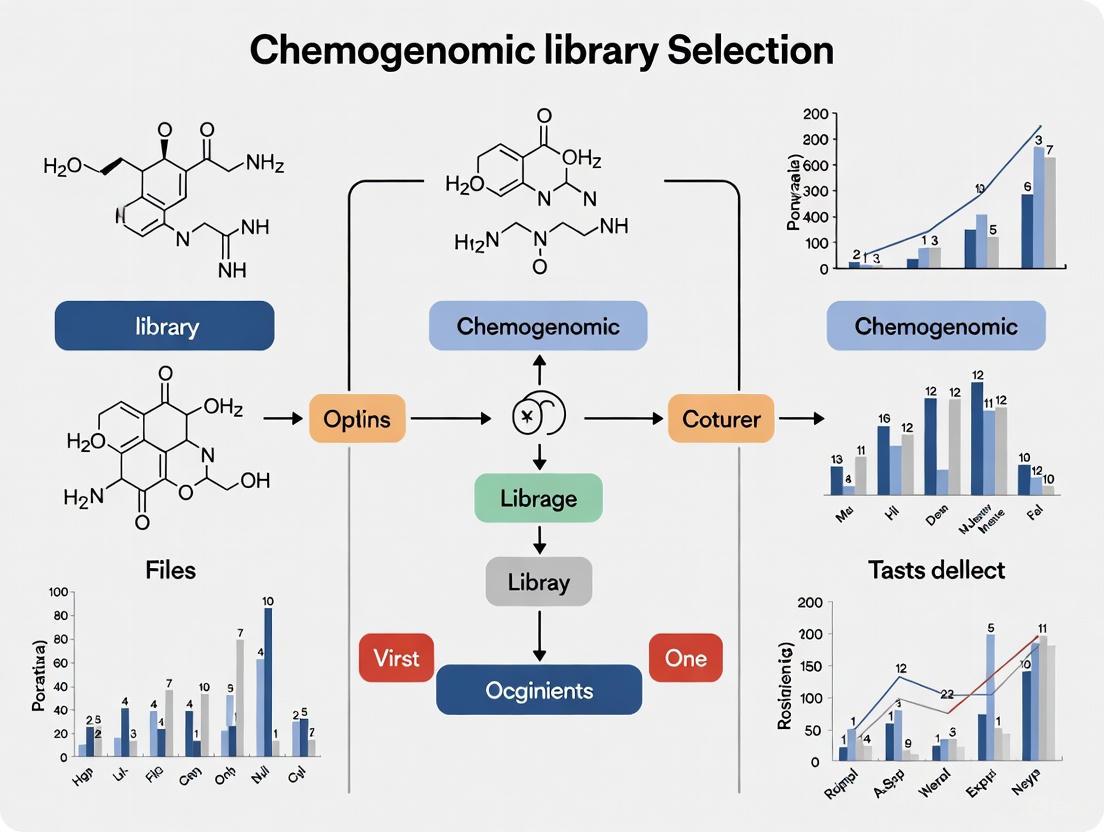

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the fundamental principles and strategic considerations for selecting and assembling chemogenomic libraries.

Strategic Chemogenomic Library Selection: Principles and Practices for Accelerated Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the fundamental principles and strategic considerations for selecting and assembling chemogenomic libraries. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it bridges the gap between foundational theory and practical application. The content systematically explores core definitions and the role of chemogenomics in modern phenotypic drug discovery, details methodological approaches for library design and data integration, addresses common limitations and optimization strategies, and establishes frameworks for library validation and comparative analysis. By synthesizing insights from current literature and case studies, this guide aims to empower teams to build more effective, targeted, and informative small-molecule libraries that enhance the efficiency of target identification and lead optimization.

What is a Chemogenomic Library? Core Concepts and Strategic Importance

Chemogenomics is an innovative approach in chemical biology that synergizes combinatorial chemistry with genomic and proteomic biology to systematically study the response of a biological system to a set of compounds [1]. This methodology enables the identification and validation of biological targets as well as the discovery of biologically active small molecules responsible for a phenotypic outcome [1]. Central to this strategy is the use of carefully selected compound collections known as chemogenomic libraries, which allow researchers to explore interactions between small molecules and a broad spectrum of biological targets, providing insights into druggable pathways and enhancing the efficiency of drug discovery [2] [3].

The field represents a paradigm shift from the traditional reductionist vision of "one target—one drug" to a more complex systems pharmacology perspective of "one drug—several targets" [4]. This shift acknowledges that complex diseases like cancers, neurological disorders, and diabetes are often caused by multiple molecular abnormalities rather than a single defect, requiring more comprehensive intervention strategies [4].

Key Applications and Strategic Approaches

Primary Research Applications

Chemogenomics serves multiple critical functions in modern drug discovery and chemical biology:

Target Discovery and Deconvolution: By screening chemogenomic libraries in disease-relevant assays, researchers can identify significant molecular targets for in-depth study [5]. The approach is particularly valuable for determining the mechanisms of action (MOA) of compounds identified in phenotypic screens [3] [4].

Target Validation: Well-characterized chemical modulators provide powerful tools for establishing the therapeutic relevance of novel targets [2].

Chemical Probe Development: The systematic exploration of chemogenomic space facilitates the creation of selective pharmacological agents for studying protein function [2] [3].

Polypharmacology Profiling: Chemogenomics enables the study of how compounds interact with multiple targets, which is crucial for understanding drug efficacy and safety profiles [4].

Chemogenomic Library Strategies

Two complementary approaches define chemogenomic library design and application:

*Focus Set Strategy*: These libraries contain compounds targeting specific protein families (e.g., kinases, GPCRs) with well-annotated activity profiles. Examples include the Kinase Chemogenomic Set (KCGS), which comprises inhibitors with narrow profiles targeting specific kinase subsets [5].

*Diversity Set Strategy*: These libraries aim for broad coverage across multiple target families, enabling systematic exploration of diverse biological pathways. The EUbOPEN project exemplifies this approach with a chemogenomic library covering approximately one-third of the druggable proteome [2].

Table 1: Classification of Chemogenomic Libraries by Strategic Approach

| Strategy Type | Target Coverage | Compound Characteristics | Primary Applications | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus Set | Single protein family or target class | High selectivity within target family; well-annotated activity profiles | Target family screening; structure-activity relationship studies | Kinase Chemogenomic Set (KCGS); GPCR-focused libraries [5] [4] |

| Diversity Set | Multiple target families across druggable proteome | Broad structural diversity; overlapping target profiles | Phenotypic screening; target deconvolution; systems pharmacology | EUbOPEN chemogenomic library; Pfizer chemogenomic library [2] [4] |

Chemogenomic Library Composition and Coverage

The composition of chemogenomic libraries reflects the current understanding of the druggable proteome and available chemical tools. Analysis of public repositories reveals that as of 2020, prominent databases contained 566,735 compounds with target-associated bioactivity ≤10 μM, covering 2,899 human target proteins as chemogenomic compound candidates [2]. Kinase inhibitors and G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) ligands dominate these annotated compounds, though coverage of other target families continues to expand [2].

The EUbOPEN consortium has established specific criteria for compound selection in chemogenomic libraries, taking into account the availability of well-characterized compounds, screening possibilities, ligandability of different targets, and the possibility to collate more than one chemotype per target [2]. This careful curation ensures that libraries contain compounds with overlapping target profiles, enabling researchers to identify the specific target responsible for a phenotype through pattern recognition [2].

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Chemogenomic Library Coverage

| Parameter | Public Repository Data | EUbOPEN Project Targets | Representative Target Families |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Compounds | 566,735 compounds with bioactivity ≤10 μM [2] | Library covering 1/3 of druggable proteome [2] | Kinases, GPCRs, SLCs, E3 ligases, epigenetic targets [5] [2] |

| Human Target Coverage | 2,899 human target proteins [2] | 100 chemical probes by 2025 [2] | Protein kinases, methyltransferases, solute carriers [3] |

| Library Size Examples | 5,000 compounds in specialized phenotypic screening libraries [4] | 50 new collaboratively developed chemical probes [2] | E3 ligases, SLCs, understudied target families [2] |

Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

Integrated Data Curation Workflow

Robust chemogenomics research requires rigorous data curation to ensure reliability and reproducibility. The following integrated workflow for chemical and biological data curation has been developed to address common quality issues [6]:

Chemogenomic Data Curation Workflow

Chemical Curation Steps:

- Structural Cleaning: Detection of valence violations, extreme bond lengths and angles, ring aromatization [6]

- Standardization: Normalization of specific chemotypes and tautomeric forms using tools such as RDKit or Chemaxon JChem [6]

- Stereochemistry Verification: Confirmation of correct stereochemical assignments, particularly for compounds with multiple asymmetric centers [6]

- Mixture Removal: Elimination of inorganic, organometallic, counterions, biologics, and mixtures that complicate computational analysis [6]

Bioactivity Curation Steps:

- Duplicate Processing: Identification of structurally identical compounds with multiple activity records to prevent over-optimistic model performance [6]

- Suspicious Entry Flagging: Application of cheminformatics approaches to identify potentially erroneous activity entries [6]

- Experimental Context Annotation: Documentation of critical experimental parameters such as screening technologies and assay conditions that influence results [6]

Phenotypic Screening and Target Deconvolution

Advanced phenotypic screening represents a major application of chemogenomics. The following workflow illustrates the integration of chemogenomic approaches with phenotypic screening for target identification:

Target Deconvolution Workflow

Morphological Profiling Integration:

- The Cell Painting assay provides high-content imaging-based phenotypic profiling, measuring 1,779 morphological features across cell, cytoplasm, and nucleus objects [4]

- Automated image analysis using CellProfiler identifies individual cells and quantifies morphological features to produce cell profiles [4]

- Comparison of cell profiles across treatment conditions enables grouping of compounds into functional pathways and identification of disease signatures [4]

Network Pharmacology Building:

- Integration of heterogeneous data sources (ChEMBL, KEGG, Gene Ontology, Disease Ontology) using graph databases such as Neo4j [4]

- Construction of system pharmacology networks connecting drug-target-pathway-disease relationships [4]

- Scaffold analysis using tools like ScaffoldHunter to identify characteristic core structures across active compounds [4]

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful chemogenomics research requires carefully selected reagents and computational resources. The following table details key components of the chemogenomics research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Chemogenomics

| Reagent/Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probe Compounds | EUbOPEN donated chemical probes; Selective kinase inhibitors [5] [2] | Target validation and functional studies | Potency <100 nM; selectivity ≥30-fold over related proteins; cellular target engagement <1 μM [2] |

| Chemogenomic Compound Collections | KCGS; EUbOPEN chemogenomic library; Pfizer/GSK compound sets [5] [2] [4] | Phenotypic screening; target deconvolution | Well-annotated target profiles; overlapping selectivity patterns; multiple chemotypes per target [2] |

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL; PubChem; PDSP Ki Database [6] | Compound-target interaction data mining | Publicly accessible; standardized bioactivity measurements; cross-referenced target information [6] |

| Pathway and Ontology Resources | KEGG; Gene Ontology; Disease Ontology [4] | Biological context annotation and network analysis | Manually curated pathways; standardized functional annotations; disease relationships [4] |

| Structural Curation Tools | RDKit; Chemaxon JChem; KNIME workflows [6] | Chemical structure standardization and validation | Automated structure cleaning; tautomer standardization; stereochemistry verification [6] |

Quality Standards and Validation Criteria

Chemical Probe Qualification

The development of high-quality chemical probes requires adherence to strict criteria established by consortia such as EUbOPEN [2]:

- Potency: In vitro activity less than 100 nM [2]

- Selectivity: At least 30-fold selectivity over related proteins [2]

- Cellular Target Engagement: Evidence of target engagement in cells at less than 1 μM (or 10 μM for shallow protein-protein interaction targets) [2]

- Toxicity Window: Reasonable cellular toxicity window unless cell death is target-mediated [2]

- Negative Controls: Availability of structurally similar inactive control compounds [2]

Data Quality and Reproducibility

Ensuring data quality is paramount in chemogenomics due to documented challenges with reproducibility in chemical biology literature [6]. Key considerations include:

- Error Rates: Chemical structure error rates in public databases range from 0.1% to 3.4%, with an average of two molecules with erroneous structures per medicinal chemistry publication [6]

- Experimental Variation: Subtle differences in screening technologies (e.g., tip-based versus acoustic dispensing) can significantly influence experimental responses and subsequent modeling results [6]

- Community Curation: Crowd-sourced curation efforts, as exemplified by ChemSpider, can achieve quality comparable to expert-curated databases [6]

Future Directions and Concluding Remarks

Chemogenomics continues to evolve with emerging technologies and approaches. Several areas show particular promise for advancing the field:

- Expanding Target Coverage: Chemoproteomics approaches using functionalized chemical probes with mass spectrometry analysis are mapping small molecule-protein interactions in cells, significantly expanding the ligandable proteome [3]

- New Modalities: Molecular glues, PROTACs, and other proximity-inducing small molecules represent new chemical modulators with unique properties that expand the druggable proteome [2]

- Open Science Initiatives: Projects such as EUbOPEN and Target 2035 aim to generate chemical or biological modulators for nearly all human proteins by 2035, making chemical tools and data freely available to the research community [2]

In conclusion, chemogenomics represents a powerful framework for systematically interrogating biological systems with small molecules. Through the strategic application of carefully designed compound libraries, robust experimental and computational methodologies, and rigorous quality standards, this approach continues to drive advances in target discovery, validation, and drug development.

Distinguishing Forward and Reverse Chemogenomics Approaches

Chemogenomics represents a systematic approach in drug discovery that investigates the interaction between chemical compounds and biological targets on a genome-wide scale. This field leverages the interplay between small molecules (chemo-) and the full set of potential drug targets (-genomics) to understand biological systems and identify novel therapeutic candidates [4]. Within this paradigm, two complementary strategies have emerged: forward chemogenomics (phenotype-based) and reverse chemogenomics (target-based). These approaches differ fundamentally in their starting points, methodologies, and applications throughout the drug discovery pipeline. The selection between these strategies directly influences library design, experimental protocols, and the types of therapeutic insights that can be generated, making their distinction critical for researchers designing chemogenomic studies [6] [4].

Forward chemogenomics begins with the observation of phenotypic changes in biological systems following chemical treatment, then works backward to identify the molecular targets and mechanisms responsible. Conversely, reverse chemogenomics starts with a predefined molecular target of interest and screens for compounds that selectively modulate its activity. Both approaches have demonstrated significant value in modern drug discovery, with the optimal choice depending on the research goals, available resources, and biological context [4]. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, methodological considerations, and practical applications of both approaches within the broader context of chemogenomic library selection research.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Defining the Approaches

Forward Chemogenomics (phenotype-based) utilizes phenotypic screening as its discovery engine. This approach involves screening compound libraries against cellular or organismal models to identify molecules that induce a desired phenotypic change, without requiring prior knowledge of specific molecular targets [4]. The strength of this method lies in its ability to identify novel therapeutic mechanisms and targets, making it particularly valuable for complex diseases where validated targets are lacking. Following hit identification, target deconvolution methods are employed to elucidate the mechanisms of action (MOA) of active compounds, often using chemogenomic libraries designed to cover diverse biological targets and pathways [4].

Reverse Chemogenomics (target-based) represents the traditional drug discovery paradigm that begins with a validated molecular target. This approach designs or screens compound libraries specifically against a predefined target, typically a protein implicated in disease pathology [7]. The screening is performed using target-specific assays (e.g., binding assays, enzymatic activity assays) to identify hits that modulate the target's activity. These hits are then optimized for potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties before being evaluated in cellular and animal models to assess their functional effects on phenotype [8].

Comparative Framework

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Forward and Reverse Chemogenomics

| Characteristic | Forward Chemogenomics | Reverse Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Phenotypic observation | Known molecular target |

| Screening Focus | Phenotypic changes (e.g., cell morphology, viability) | Target modulation (e.g., binding affinity, enzymatic inhibition) |

| Target Knowledge | Not required initially; identified during target deconvolution | Required before screening begins |

| Primary Strength | Identifies novel mechanisms and targets; more translatable to complex biology | More straightforward optimization; clearer structure-activity relationships |

| Key Challenge | Target deconvolution can be difficult and time-consuming | Limited to known biology; may miss polypharmacology effects |

| Library Design | Diverse compounds covering broad chemical space; often annotated with bioactivity data | Focused libraries for specific target classes (e.g., kinase inhibitors, GPCR ligands) |

| Hit Optimization | Based on phenotypic responses and secondary target validation | Based on target potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties |

Forward Chemogenomics: Methodology and Applications

Experimental Workflow

The forward chemogenomics workflow integrates several technologies from compound screening to mechanistic insight, with phenotypic assessment serving as the critical filter throughout the process.

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Phenotypic Screening Technologies form the foundation of forward chemogenomics. The Cell Painting protocol has emerged as a particularly powerful method, providing multivariate morphological profiling using multiple fluorescent dyes [4]. The standard protocol involves: (1) plating U2OS osteosarcoma cells or other relevant cell lines in multiwell plates; (2) compound treatment at appropriate concentrations and duration; (3) staining with a cocktail of dyes including MitoTracker (mitochondria), Phalloidin (actin), Concanavalin A (endoplasmic reticulum), SYTO 14 (nucleoli), and Wheat Germ Agglutinin (cell membrane and Golgi); (4) fixation and high-throughput microscopy; (5) automated image analysis using CellProfiler to extract morphological features (size, shape, texture, intensity, granularity) [4]. This generates approximately 1,779 morphological features that collectively form a "phenotypic fingerprint" for each compound.

Target Deconvolution Methods are critical for translating phenotypic hits into mechanistic insights. Key protocols include:

- Chemical Proteomics: Utilize immobilized active compounds as affinity probes to capture protein targets from cell lysates, followed by mass spectrometry identification [9].

- Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA): Monitor protein thermal stability changes upon compound binding using the HiBiT CETSA protocol, which employs a small luciferase fragment (HiBiT) for sensitive detection of target engagement in cellular contexts [9].

- Functional Genetic Approaches: Employ CRISPR-based genetic screens to identify genes whose perturbation modulates compound sensitivity, indicating potential targets or pathway members.

Chemogenomic Libraries for Phenotypic Screening

Effective forward chemogenomics requires carefully designed compound libraries that maximize the potential for identifying biologically active compounds and their mechanisms. These libraries typically contain 5,000-30,000 compounds selected to cover diverse chemical space while including annotated bioactivities across multiple target classes [4]. Essential design principles include:

- Target Diversity: Representation of compounds active against a broad range of protein families (kinases, GPCRs, ion channels, nuclear receptors, etc.)

- Structural Diversity: Inclusion of diverse molecular scaffolds to maximize chemical space coverage

- Bioactivity Annotation: Incorporation of existing bioactivity data (IC50, Ki, EC50 values) from databases like ChEMBL to facilitate target hypothesis generation [4]

- Phenotypic Profiling: Integration of historical phenotypic screening data, such as morphological profiles from Cell Painting assays

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Forward Chemogenomics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Dyes | MitoTracker Red CMXRos, Phalloidin (Alexa Fluor 488), Hoechst 33342, Wheat Germ Agglutinin (Alexa Fluor 647), Concanavalin A (Alexa Fluor 488) | Multiplexed morphological profiling of subcellular structures |

| Cell Lines | U2OS (osteosarcoma), A549 (lung carcinoma), iPSC-derived cells | Phenotypic screening in disease-relevant models |

| Chemogenomic Libraries | Pfizer chemogenomic library, GSK Biologically Diverse Compound Set, NCATS MIPE library | Diverse compound sets with annotated bioactivities for phenotypic screening |

| Image Analysis Software | CellProfiler, ImageJ, IN Cell Investigator, Harmony High-Content Imaging | Automated extraction of morphological features from cellular images |

| Target Deconvolution Tools | HiBiT Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA), Kinase Chemogenomics sets, DUB inhibitors | Identification of molecular targets for phenotypic hits |

Reverse Chemogenomics: Methodology and Applications

Experimental Workflow

Reverse chemogenomics follows a structured path from target selection through compound optimization, with target-focused assessment guiding each stage.

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Target-Focused Screening Technologies enable efficient identification of target modulators. The HiBiT Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (HiBiT CETSA) protocol provides a robust method for detecting target engagement in live cells: (1) Engineer cells to express the target protein tagged with the 11-amino acid HiBiT tag; (2) Treat cells with test compounds; (3) Heat cells to denature and precipitate unbound proteins; (4) Lyse cells and add LgBiT protein to complement with HiBiT tag; (5) Measure luminescence to quantify remaining soluble target protein [9]. Compounds that bind and stabilize the target will show increased luminescence at higher temperatures compared to untreated controls.

Kinase Selectivity Profiling represents another essential protocol for reverse chemogenomics, particularly using the NanoBRET Live-Cell Kinase Selectivity Profiling method: (1) Transiently transfect cells with Nanoluc-fused kinases; (2) Treat cells with test compounds and cell-permeable NanoBRET tracer; (3) Measure BRET signal to determine compound binding to each kinase; (4) Generate selectivity profiles across the kinome family [9]. This approach allows comprehensive assessment of compound selectivity in physiologically relevant cellular environments.

AI-Driven Compound Design has become increasingly integral to reverse chemogenomics. The Genotype-to-Drug Diffusion (G2D-Diff) framework exemplifies this trend: (1) Pre-train a chemical variational autoencoder (VAE) on ~1.5 million known compounds to learn molecular latent space; (2) Train a conditional diffusion model that generates compound latent vectors based on input genotype and desired drug response; (3) Decode generated vectors into SMILES representations using the chemical VAE decoder; (4) Validate generated compounds for drug-likeness, synthesizability, and predicted activity [7]. This approach directly generates novel compounds tailored to specific cancer genotypes without requiring separate predictors during generation.

Target-Focused Library Design

Reverse chemogenomics relies on carefully curated compound libraries optimized for specific target classes. These libraries typically range from a few hundred to several thousand compounds selected based on:

- Target Family Coverage: Compounds known to be active against specific protein families (e.g., kinase inhibitors, GPCR ligands, protease inhibitors)

- Structural Similarity: Analog series and scaffold hops around known active compounds

- Selectivity Profiles: Compounds with defined selectivity patterns across related targets

- Lead-like Properties: Favorable physicochemical properties for hit-to-lead optimization

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Reverse Chemogenomics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Target Engagement Assays | HiBiT CETSA, NanoBRET Kinase Profiling, Differential Scanning Fluorimetry | Detection of compound binding to specific targets in cellular contexts |

| Focused Libraries | Kinase Chemogenomics sets, GPCR-focused libraries, Protein-Protein Interaction inhibitors | Target-class specific compounds for screening |

| AI/Computational Tools | G2D-Diff model, Exscientia's Centaur Chemist, Schrödinger's physics-based platforms | De novo compound design for specific targets |

| Selectivity Panels | Kinase panels, GPCR panels, safety pharmacology panels | Assessment of compound selectivity against related targets |

| Structural Biology Tools | X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Structural characterization of compound-target interactions |

Integrated Approaches and Future Directions

The distinction between forward and reverse chemogenomics is becoming increasingly blurred as integrated approaches emerge. Modern drug discovery platforms now combine elements of both paradigms to leverage their complementary strengths. For instance, the merger of Recursion's phenomic screening capabilities with Exscientia's automated precision chemistry created a full end-to-end platform that leverages both phenotypic observations and target-focused design [8]. Similarly, the G2D-Diff model incorporates genotype information (reverse approach) with phenotypic drug response data (forward approach) to generate novel anti-cancer compounds [7].

The future of chemogenomics will likely see increased integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning across both approaches. AI platforms can analyze complex phenotypic data from forward screens to generate hypotheses about mechanisms of action, while also accelerating the compound design and optimization processes central to reverse chemogenomics [8] [7]. Furthermore, the growing emphasis on chemical biology and systems pharmacology approaches will continue to bridge the gap between these strategies, enabling more comprehensive understanding of compound mechanisms and polypharmacology.

For researchers designing chemogenomics studies, the choice between forward and reverse approaches should be guided by the specific research question, available resources, and stage of drug discovery. Forward chemogenomics offers particular value for exploring novel biology and identifying new therapeutic mechanisms, especially for complex diseases with poorly understood pathophysiology. Reverse chemogenomics remains highly effective for optimizing compounds against validated targets and pursuing precision medicine approaches where the genetic drivers of disease are well characterized. By understanding the principles, methodologies, and applications of both approaches, researchers can make informed decisions about chemogenomic library selection and experimental design to maximize the success of their drug discovery efforts.

The Central Role of Targeted Libraries in Phenotypic Drug Discovery

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD), an approach that identifies compounds based on their modulation of disease-relevant phenotypes rather than predefined molecular targets, has re-emerged as a powerful strategy for generating first-in-class medicines [10]. Historically, many pioneering therapeutics were discovered through observations of their effects on disease physiology, but this approach was largely supplanted by target-based drug discovery (TDD) following the molecular biology revolution [10]. The contemporary resurgence of PDD stems from its ability to address the incompletely understood complexity of diseases and to reveal novel mechanisms of action (MoA) that would be difficult to anticipate through reductionist approaches [10] [11].

The critical challenge in modern PDD lies in bridging the gap between the initial phenotypic hit and the subsequent understanding of its mechanism of action—a process known as target deconvolution. It is at this interface that targeted chemogenomic libraries play a transformative role. These libraries, comprising carefully selected compounds with well-annotated activities across specific protein families, provide a powerful solution for navigating the complexity of phenotypic screening outputs [2] [5]. By combining the biological relevance of phenotypic assays with the targeted coverage of key druggable proteomes, these libraries enable researchers to systematically explore chemical space while retaining the ability to generate testable hypotheses about molecular targets responsible for observed phenotypes.

The Strategic Rationale for Targeted Libraries in PDD

Expanding the Druggable Target Space

Phenotypic screening has repeatedly demonstrated its ability to expand the "druggable target space" by identifying compounds that modulate unexpected cellular processes and novel target classes [10]. Notable successes include:

- Modulators of pre-mRNA splicing (e.g., risdiplam for spinal muscular atrophy)

- CFTR correctors (e.g., tezacaftor and elexacaftor for cystic fibrosis)

- Molecular glues (e.g., lenalidomide and its novel mechanism involving Cereblon E3 ligase) [10]

These discoveries emerged from phenotypic approaches because they operated on targets and mechanisms that would have been difficult to predict through hypothesis-driven target-based approaches. Targeted libraries amplify this potential by providing systematic coverage of understudied protein families, thereby increasing the probability of engaging novel biological pathways in phenotypic screens.

Enabling Informed Polypharmacology

The traditional drug discovery paradigm has emphasized high selectivity for single molecular targets. However, polypharmacology—the ability of a compound to interact with multiple targets—is increasingly recognized as contributing to clinical efficacy for many complex diseases [10]. PDD naturally accommodates polypharmacology, as it identifies compounds based on holistic phenotypic effects rather than single-target engagement.

Targeted chemogenomic libraries are ideally suited to leverage polypharmacology because they comprise compounds with well-characterized selectivity profiles across target families. Rather than viewing multi-target activity as a liability, researchers can intentionally select compound sets with overlapping target coverage to identify synergistic target combinations or to balance efficacy and safety profiles [2] [10]. The EUbOPEN consortium, for instance, has established family-specific criteria for chemogenomic compounds that take into account ligandability, availability of multiple chemotypes, and screening possibilities [2].

Table 1: Recent Phenotypic Drug Discovery Successes with Novel Mechanisms

| Compound | Disease Area | Novel Target/Mechanism | Discovery Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risdiplam | Spinal Muscular Atrophy | SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing modulator | Phenotypic screen in patient-derived cells [10] |

| Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor | Cystic Fibrosis | CFTR correctors (protein folding/trafficking) | Phenotypic screen in CFTR mutant cell lines [10] |

| Lenalidomide | Multiple Myeloma | Cereblon E3 ligase modulator (molecular glue) | Clinical observation followed by phenotypic characterization [10] |

| Daclatasvir | Hepatitis C | NS5A inhibitor (non-enzymatic target) | HCV replicon phenotypic screen [10] |

Design and Composition of Targeted Chemogenomic Libraries

Key Protein Families in Chemogenomic Libraries

Targeted chemogenomic libraries are structured around protein families with established druggability and therapeutic relevance. The EUbOPEN consortium, one of the most comprehensive public-private partnerships in this domain, has focused its efforts on several key target families [2]:

- Kinases: Historically the most extensively studied target family in chemogenomics, with well-characterized inhibitor profiles and selectivity patterns [5]

- G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs): A major drug target family with compounds spanning agonists, antagonists, and allosteric modulators

- Solute Carriers (SLCs): An emerging target family with critical roles in metabolism and nutrient transport

- E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: Key regulators of protein degradation with growing importance for targeted protein degradation approaches

- Epigenetic regulators: Including histone modifying enzymes and readers [2] [5]

The EUbOPEN project aims to create a chemogenomic library covering approximately one-third of the druggable proteome, representing one of the most comprehensive publicly available resources for targeted screening [2].

Quality Standards and Annotation

The utility of a targeted library depends critically on the quality and completeness of compound annotation. The EUbOPEN consortium has established strict criteria for chemical probes, requiring [2]:

- Potency: <100 nM in in vitro assays

- Selectivity: At least 30-fold over related proteins

- Cellular target engagement: <1 μM (or <10 μM for shallow protein-protein interaction targets)

- Reasonable cellular toxicity window (unless cell death is target-mediated)

For chemogenomic compounds, which may have narrower but not exclusive selectivity, the consortium has developed family-specific criteria that consider the availability of well-characterized compounds, screening possibilities, and the potential to include multiple chemotypes per target [2].

Table 2: EUbOPEN Library Composition and Quality Standards

| Library Component | Coverage | Quality Standards | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | 100 high-quality probes (goal by 2025) | Potency <100 nM, selectivity >30-fold, cellular activity [2] | Peer-reviewed, accompanied by negative controls, distributed without restrictions |

| Chemogenomic Compound Library | ~1/3 of druggable proteome [2] | Family-specific criteria for selectivity and potency [2] | Well-annotated target profiles, overlapping selectivity for target deconvolution |

| Donated Chemical Probes | 50 additional probes from community | External peer-review against established criteria [2] | Openly available with usage guidelines to minimize off-target effects |

Experimental Framework: Integrating Targeted Libraries with Phenotypic Screening

Workflow for Phenotypic Screening with Targeted Libraries

The integration of targeted libraries into phenotypic screening campaigns follows a structured workflow that maximizes the biological insights gained while accelerating the target identification process. The diagram below illustrates this integrated approach:

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Phenotypic Assay Development

The foundation of any successful PDD campaign is a physiologically relevant assay system that robustly captures disease biology. Best practices include:

- Use of disease-relevant cellular models: Primary cells, patient-derived cells, iPSC-derived lineages, or engineered tissues that recapitulate key disease phenotypes [10] [11]

- Implementation of complex coculture systems: When cell-cell interactions are fundamental to disease mechanisms

- Application of high-content imaging and multi-parameter readouts: To capture nuanced phenotypic changes and reduce false positives [11]

- Focus on translational biomarkers: Those with established correlation to clinical outcomes when possible

The EUbOPEN consortium, for instance, profiles compounds in patient-derived disease assays with particular focus on inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, and neurodegeneration [2].

Library Selection and Screening Protocol

The selection of an appropriate targeted library requires careful consideration of the biological context and potential mechanisms. A typical screening protocol involves:

- Library composition: Selection of a targeted library matched to the disease biology (e.g., kinase-focused for oncology, GPCR-focused for neurology)

- Screening concentration: Typically 1-10 μM to balance identification of potent compounds while minimizing non-specific effects

- Counter-screening: Implementation of orthogonal assays to identify nuisance compounds (e.g., cytotoxicity, fluorescence interference)

- Concentration-response: Follow-up testing of primary hits across a range of concentrations (e.g., 0.1 nM - 100 μM) to confirm potency and begin assessing structure-activity relationships

Data Curation and Quality Control

The value of a targeted library depends entirely on the quality and reliability of its annotations. Best practices in data curation include [6]:

- Chemical structure standardization: Validation of structural integrity, stereochemistry, and removal of duplicates

- Bioactivity data harmonization: Normalization of activity measures (IC50, Ki, EC50) and units across different sources

- Selectivity profiling: Assessment of activity across related targets to establish selectivity patterns

- Cross-repository validation: Comparison of activity data across multiple public databases (ChEMBL, PubChem) to identify inconsistencies

Large-scale chemogenomics datasets like ExCAPE-DB, which integrates over 70 million structure-activity data points from PubChem and ChEMBL, exemplify the importance of rigorous data curation for building reliable targeted libraries [12].

Target Deconvolution Strategies Enabled by Targeted Libraries

The Chemogenomic Approach to Target Identification

Target deconvolution represents the most significant challenge in PDD. Targeted libraries facilitate this process through several complementary approaches:

- Selectivity pattern analysis: Using the known target profiles of multiple active compounds to identify common targets responsible for the phenotypic effect [2]

- Chemoproteomics: Employing library compounds as affinity reagents to pull down cellular targets

- Structural analog testing: Evaluating structurally related compounds with differing potency profiles to establish correlations with target engagement

- Resistance generation: Selecting for resistant clones in cellular models and identifying genomic changes that confer resistance

The diagram below illustrates the integrated target deconvolution workflow enabled by targeted libraries:

Case Studies: Successful Target Identification

The power of the targeted library approach is exemplified by several recent successes:

- SOCS2 inhibitors: EUbOPEN researchers developed covalent inhibitors of the Cul5-RING ubiquitin E3 ligase substrate receptor SOCS2 through structure-based design, creating qualified chemical probes that block substrate recruitment in cells [2]

- Kinase inhibitor profiling: The Kinase Chemogenomic Set (KCGS) developed by the SGC enables screening in disease-relevant assays to identify significant kinases for in-depth study, with inhibitors covering narrow and broad selectivity profiles across the kinome [5]

- NS5A inhibitors: The discovery of daclatasvir emerged from a hepatitis C virus (HCV) replicon phenotypic screen, revealing NS5A—a protein with no known enzymatic function—as a critical antiviral target [10]

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Implementation

Successful implementation of targeted library approaches requires access to well-characterized research reagents and tools. The table below details essential resources available to researchers:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Targeted Library Screening

| Resource | Description | Key Features | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| EUbOPEN Chemogenomic Library | Collection of chemogenomic compounds covering multiple target families [2] | Covers ~1/3 of druggable genome, comprehensively characterized, profiled in patient-derived assays | Available via EUbOPEN website [2] |

| Kinase Chemogenomic Set (KCGS) | Well-annotated kinase inhibitor set from SGC [5] | Includes inhibitors with narrow and broad selectivity profiles, enables kinome-wide exploration | Available through SGC [5] |

| EUbOPEN Chemical Probes | 100 high-quality chemical probes with negative controls [2] | Potency <100 nM, selectivity >30-fold, peer-reviewed, cell-active | Request via eubopen.org/chemical-probes [2] |

| ExCAPE-DB | Integrated large-scale chemogenomics dataset [12] | >70 million SAR data points from PubChem and ChEMBL, standardized structures and bioactivities | Available online at https://solr.ideaconsult.net/search/excape/ [12] |

| ChEMBL Database | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules [6] [12] | Extracted from literature, standardized bioactivities, target annotations | Publicly available at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/ |

Targeted chemogenomic libraries represent an essential component of the modern phenotypic drug discovery toolkit, effectively bridging the gap between untargeted phenotypic screening and mechanism-based drug development. By providing well-annotated chemical starting points with known target relationships, these libraries accelerate the target deconvolution process and increase the overall efficiency of drug discovery.

The ongoing development of public resources such as the EUbOPEN library and the Kinase Chemogenomic Set exemplifies the power of collaborative pre-competitive initiatives in expanding the available chemical tools for the research community [2] [5]. As these resources grow to cover more of the druggable proteome and incorporate new modalities such as molecular glues and PROTACs, their utility in phenotypic screening will continue to expand.

Looking forward, the integration of targeted libraries with emerging technologies—including functional genomics, artificial intelligence, and complex human cell models—promises to further enhance the impact of phenotypic approaches. By combining the physiological relevance of phenotypic screening with the mechanistic insights enabled by targeted libraries, researchers can systematically explore the complex landscape of disease biology while maintaining a path toward understanding and optimizing the mechanisms underlying therapeutic effects.

Chemogenomic libraries are collections of well-defined, biologically active small molecules organized to facilitate the functional annotation of proteins and the discovery of novel therapeutic targets within complex biological systems [13] [14]. In modern phenotypic drug discovery (PDD), these libraries serve as a critical bridge between phenotypic observations and target-based drug discovery. A fundamental premise of chemogenomics is that a hit from such a library in a phenotypic screen implies that the annotated target or targets of that pharmacological agent are involved in the observed phenotypic perturbation [13] [15]. This approach has the potential to significantly expedite the conversion of phenotypic screening projects into target-based drug discovery pipelines by providing initial hypotheses for mechanism of action [15].

Unlike highly selective chemical probes, which must meet stringent criteria for potency and selectivity, the small molecule modulators used in chemogenomics may not be exclusively selective for a single target [14]. This relaxation of selectivity criteria enables coverage of a much larger target space. For instance, while high-quality chemical probes have been developed for only a small fraction of potential targets, chemogenomic compound sets aim to cover a substantial portion of the druggable genome, with initiatives like EUbOPEN targeting approximately 30% of the estimated 3,000 druggable targets [14] [5]. These libraries are often organized into subsets covering major protein families such as kinases, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), membrane proteins, and epigenetic modulators [14] [5].

Core Component 1: Chemical Diversity

The Role of Scaffolds in Library Design

Chemical diversity is a foundational pillar of effective chemogenomic library design, ensuring broad coverage of chemical space and thereby increasing the probability of modulating diverse biological targets. A key strategy for achieving this diversity involves the systematic analysis of molecular scaffolds. Scaffolds represent the core structural frameworks of molecules, and their diversity is a primary determinant of a library's ability to interact with distinct target families.

The process of scaffold analysis typically involves deconstructing each molecule in a library into progressively simpler representative core structures. This process, which can be performed using software tools like ScaffoldHunter, involves: (i) removing all terminal side chains while preserving double bonds directly attached to a ring, and (ii) iteratively removing one ring at a time using deterministic rules to preserve the most characteristic core structure until only one ring remains [16]. These scaffolds are then distributed across different hierarchical levels based on their relational distance from the original molecule node, creating a scaffold tree that provides a comprehensive view of the library's structural diversity [16].

Quantitative Assessment of Structural Diversity

The structural diversity of chemogenomic libraries can be quantified using computational methods that assess aggregate structural similarity. One common approach involves calculating Tanimoto similarity coefficients, which measure the molecular fingerprint similarity between compounds within a library [17]. Molecular fingerprints are generated from chemical data represented as SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings, and these fingerprints are then compared to calculate the similarity coefficient or "distance" between compounds [17].

When comparing major libraries such as the Microsource Spectrum, MIPE 4.0, LSP-MoA, and DrugBank libraries, analysis reveals that their chemical similarity distributions and cluster size frequencies are often remarkably comparable (Figure 2B, C) [17]. This suggests that despite differences in their construction philosophies, these libraries generally achieve a high degree of internal diversity, a crucial characteristic for comprehensive phenotypic screening.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Chemical Library Diversity

| Library Name | Key Diversity Characteristics | Analysis Method | Primary Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSP-MoA Library | Optimized chemical library targeting the liganded kinome [17] | Tanimoto similarity analysis [17] | High internal diversity comparable to other major libraries [17] |

| MIPE 4.0 | Small molecule probes with known mechanism of action [17] | Tanimoto similarity analysis [17] | High internal diversity comparable to other major libraries [17] |

| Microsource Spectrum | Bioactive compounds for HTS or target-specific assays [17] | Tanimoto similarity analysis [17] | High internal diversity comparable to other major libraries [17] |

| Network Pharmacology-Based Library | 5,000 small molecules representing diverse targets [16] | ScaffoldHunter analysis creating scaffold trees [16] | Designed to encompass druggable genome via scaffold filtering [16] |

Core Component 2: Target Coverage

The Scope of the Druggable Genome

Target coverage refers to the breadth and depth of proteins and biological pathways that a chemogenomic library can modulate. The human genome encodes approximately 20,000 proteins, but current estimates suggest only a fraction of these—approximately 3,000—are "druggable," meaning they possess binding pockets that can be targeted by small molecules [14] [18]. A significant limitation of even the best chemogenomic libraries is that they only interrogate a fraction of this druggable genome, typically covering between 1,000 to 2,000 targets out of the 20,000+ human genes (Figure 1A) [18]. This coverage gap represents both a challenge and an opportunity for future library development.

The EUbOPEN initiative exemplifies efforts to systematically expand target coverage by developing chemogenomic sets for under-explored target families. Their library is organized into subsets covering major target families including protein kinases, GPCRs, solute carriers (SLCs), E3 ligases, and epigenetic modulators [14] [5]. This family-based approach ensures balanced coverage across diverse protein classes, increasing the utility of the library for probing different biological processes.

Specialized Libraries for Target Families

Focusing on specific protein families allows for the development of deeply annotated, high-quality libraries tailored to those target classes. The kinase chemogenomic set (KCGS) from the SGC is a prime example, comprising well-annotated kinase inhibitors that enable screening in disease-relevant assays to identify kinases worthy of in-depth study [5]. This set includes inhibitors with narrow selectivity profiles targeting specific kinase subsets, as well as broader inhibitors that explore inhibition across the kinome [5].

Similarly, other targeted libraries have been developed for GPCR-focused screening and for targeting protein-protein interactions [16]. These specialized libraries, when used in combination or as part of a larger, more diverse collection, provide both breadth and depth of target coverage, enabling researchers to probe specific biological pathways with high precision while maintaining the ability to discover novel biology outside of well-characterized target families.

Table 2: Exemplary Chemogenomic Libraries and Their Target Coverage

| Library Name | Number of Compounds | Primary Target Coverage | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| EUbOPEN Chemogenomics Library | Not specified | Kinases, GPCRs, SLCs, E3 ligases, epigenetic targets [14] [5] | Aims to cover ~30% of the druggable genome; peer-reviewed inclusion criteria [14] |

| Kinase Chemogenomic Set (KCGS) | Not specified | Kinome [5] | Well-annotated kinase inhibitors; includes narrow-selectivity and broad-profile compounds [5] |

| MIPE 4.0 | 1,912 [17] | Diverse targets [17] | Small molecule probes with known mechanism; developed by NCATS [17] |

| Network Pharmacology Library | 5,000 [16] | Broad druggable genome [16] | Based on systems pharmacology network; integrates multiple data sources [16] |

| Microsource Spectrum | 1,761 [17] | Bioactive compounds [17] | Bioactive compounds for HTS or target-specific assays [17] |

Core Component 3: Biological Annotation

Biological annotation transforms a simple collection of compounds into a powerful functional tool by linking small molecules to their known protein targets, associated pathways, and phenotypic outcomes. High-quality annotations enable researchers to form testable hypotheses about mechanisms of action when a compound shows activity in a phenotypic screen. The depth and reliability of these annotations are what differentiate chemogenomic libraries from general screening collections.

Annotations are typically derived from multiple sources, creating a multi-layered knowledge network. The primary sources include:

- Target Binding Data: In vitro binding data (Ki, IC50, Kd values) extracted from databases like ChEMBL [17] [16].

- Pathway Information: Data from resources like the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) that place targets within biological pathways [16].

- Gene Ontology (GO) Annotations: Functional information including biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components [16].

- Disease Associations: Connections to human diseases through resources like the Human Disease Ontology (DO) [16].

- Morphological Profiling: Data from high-content imaging assays like Cell Painting that capture the phenotypic effects of compounds on cells [16].

Integrating Annotations into a Searchable Network

Merely collecting annotation data is insufficient; it must be integrated into a queryable format that enables efficient knowledge retrieval. Modern approaches utilize graph databases like Neo4j to create system pharmacology networks that integrate drug-target-pathway-disease relationships [16]. In such a network, nodes represent different entity types (molecules, proteins, pathways, diseases, etc.), while edges represent the relationships between them (e.g., a molecule targeting a protein, a target acting in a pathway) [16].

This network-based approach allows for complex queries that can identify proteins modulated by chemicals that correlate with specific morphological perturbations at the cellular level, ultimately leading to connections with phenotypes and diseases [16]. For example, one can query the network to find all compounds that target proteins in a specific pathway and have been shown to induce a particular morphological profile in the Cell Painting assay, thereby rapidly generating hypotheses for both compound mechanism and pathway function.

Quantitative Assessment of Library Quality

The Polypharmacology Index (PPindex)

A critical quantitative metric for evaluating chemogenomic libraries is the Polypharmacology Index (PPindex), which measures the overall target specificity of a compound collection [17]. This metric is particularly important because polypharmacology (the ability of a single compound to interact with multiple targets) directly opposes the goal of target deconvolution in phenotypic screening. If a library contains highly promiscuous compounds, target identification becomes significantly more challenging when those compounds show activity in a screen [17].

The PPindex is derived through the following methodology:

- Target Annotation Enumeration: For each compound in a library, all known molecular targets are identified from databases like ChEMBL, using in vitro binding data (Ki, IC50 values) filtered for redundancy [17].

- Histogram Generation: The number of recorded molecular targets for each compound is counted, and a histogram of these counts is generated [17].

- Distribution Fitting: The histogram values are sorted in descending order and transformed into natural log values. The slope of the linearized distribution represents the PPindex [17].

- Interpretation: Larger absolute values of the slope (closer to a vertical line) indicate more target-specific libraries, while smaller values (closer to a horizontal line) indicate more polypharmacologic libraries [17].

Comparative Analysis of Library Polypharmacology

When comparing major libraries, the PPindex reveals significant differences in their polypharmacology profiles. Initial analysis shows that the DrugBank library appears highly target-specific (PPindex = 0.9594), but this is partly an artifact of its larger size and data sparsity, with many compounds having only one annotated target simply because they haven't been screened against others [17]. To reduce this bias, the distributions can be re-analyzed excluding compounds with zero or one annotated target, providing a more realistic comparison of library quality [17].

Table 3: Polypharmacology Index (PPindex) Comparison of Selected Libraries

| Library Name | PPindex (All Compounds) | PPindex (Without 0-Target Compounds) | PPindex (Without 0- or 1-Target Compounds) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DrugBank | 0.9594 [17] | 0.7669 [17] | 0.4721 [17] |

| LSP-MoA | 0.9751 [17] | 0.3458 [17] | 0.3154 [17] |

| MIPE 4.0 | 0.7102 [17] | 0.4508 [17] | 0.3847 [17] |

| Microsource Spectrum | 0.4325 [17] | 0.3512 [17] | 0.2586 [17] |

| DrugBank Approved | 0.6807 [17] | 0.3492 [17] | 0.3079 [17] |

This quantitative assessment enables objective comparison of libraries and provides guidance for library selection based on screening goals. For target deconvolution in phenotypic screens, libraries with higher PPindex values (greater target specificity) are generally preferable, as they provide clearer hypotheses about which targets are responsible for observed phenotypic effects [17].

Experimental Protocols for Library Evaluation

Protocol 1: Target Identification and Annotation

Purpose: To comprehensively identify and annotate the molecular targets of compounds within a chemogenomic library. Methodology:

- Compound Registration: Convert all library compounds to canonical SMILES strings, which preserve stereochemistry information and standardize molecular representation [17].

- Data Extraction: Query bioactivity databases (e.g., ChEMBL, DrugBank) for in vitro binding data (Ki, IC50, EC50 values) for each compound [17] [16].

- Similarity Expansion: Include compounds with high structural similarity (Tanimoto coefficient ≥0.99) in the query to account for salts, isomers, and closely related analogs [17].

- Affinity Filtering: Apply affinity cutoffs to distinguish true biological targets from weak, potentially non-specific interactions. Nanomolar affinities typically represent significant targets, while micromolar affinities are considered ambiguous [17].

- Data Integration: Integrate target annotations with pathway information from KEGG, functional annotations from Gene Ontology, and disease associations from Disease Ontology [16].

Protocol 2: Polypharmacology Index Determination

Purpose: To quantitatively assess the target specificity of a chemogenomic library. Methodology:

- Target Counting: For each compound in the library, count the number of distinct molecular targets with confirmed binding affinity below predetermined thresholds [17].

- Histogram Generation: Create a histogram representing the distribution of target counts per compound across the entire library [17].

- Distribution Linearization: Transform the histogram values by sorting in descending order and applying natural logarithm transformation [17].

- Slope Calculation: Fit a linear curve to the transformed data using ordinary least squares regression in software such as MATLAB. The absolute value of the slope represents the PPindex [17].

- Goodness of Fit: Verify that the fitted curve has a high R-squared value (typically >0.96 for a Boltzmann distribution) to ensure the reliability of the PPindex [17].

Protocol 3: Systems Pharmacology Network Construction

Purpose: To integrate diverse biological annotations into a queryable network for hypothesis generation. Methodology:

- Node Definition: Define node types to represent key entities: Molecules, Scaffolds, Proteins, Pathways, Diseases, and Morphological Profiles [16].

- Relationship Establishment: Establish relationship types between nodes: "partof" (scaffold to molecule), "targets" (molecule to protein), "participatesin" (protein to pathway), "associated_with" (protein to disease), and "induces" (molecule to morphological profile) [16].

- Database Implementation: Implement the network using a graph database such as Neo4j, which efficiently handles complex relationships and enables sophisticated traversal queries [16].

- Enrichment Analysis: Incorporate functional enrichment analysis using tools like clusterProfiler R package to identify statistically overrepresented GO terms, KEGG pathways, or disease associations within compound hit sets [16].

- Query Interface: Develop standardized query templates to support common investigation scenarios, such as identifying all compounds that target proteins in a specific pathway and produce a particular morphological phenotype [16].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomic Studies

| Resource Name | Type | Key Features/Functions | Applicable Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| EUbOPEN Chemogenomics Library | Compound Library | Covers kinases, GPCRs, SLCs, E3 ligases, epigenetic targets; peer-reviewed inclusion criteria [14] [5] | Target discovery and validation across multiple protein families [14] |

| SGC Chemical Probes | Quality-Controlled Compounds | Cell-active, small-molecule ligands meeting strict criteria (e.g., in vitro Kd < 100 nM, >30-fold selectivity) [19] | High-confidence target validation; studies requiring high specificity [19] |

| Cell Painting Assay | Phenotypic Profiling Method | High-content imaging assay measuring 1,779+ morphological features [16] | Generating morphological profiles for mechanism of action studies [16] |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity Database | Standardized bioactivity, molecule, target, and drug data extracted from literature [16] | Target annotation and polypharmacology assessment [17] [16] |

| ScaffoldHunter | Software Tool | Analyzes molecular scaffolds and creates hierarchical scaffold trees [16] | Assessing and optimizing chemical diversity in library design [16] |

| Neo4j | Graph Database Platform | Integrates heterogeneous data sources into a queryable network [16] | Building systems pharmacology networks for target deconvolution [16] |

The strategic development and application of chemogenomic libraries require careful balancing of three core components: chemical diversity, target coverage, and biological annotation. Chemical diversity, achieved through thoughtful scaffold-based design and analysis, ensures the library can probe diverse biological mechanisms. Target coverage, while currently limited to a fraction of the druggable genome, can be optimized through family-focused sets and continues to expand with initiatives like EUbOPEN. Biological annotation, particularly when integrated into queryable network pharmacology databases, transforms chemical libraries into powerful hypothesis-generation tools that accelerate target deconvolution in phenotypic screening.

Quantitative assessment methods like the Polypharmacology Index provide objective metrics for library evaluation and selection, while standardized experimental protocols enable consistent library characterization and application. As these libraries continue to evolve with improved annotation quality, expanded target coverage, and better understanding of polypharmacology, they will remain indispensable tools for bridging the gap between phenotypic observation and target-based drug discovery, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutic strategies for complex diseases.

Chemogenomic (CG) libraries are strategically designed collections of small molecules used to systematically probe biological systems. They represent a shift from the traditional "one target–one drug" paradigm toward a systems pharmacology perspective, where compounds may interact with multiple protein targets. This approach is particularly valuable for studying complex diseases like cancer, neurological disorders, and metabolic diseases, which often involve multiple molecular abnormalities rather than a single defect [4].

A key distinction exists between highly characterized chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds. Chemical probes are the gold standard—characterized by high potency (typically <100 nM), high selectivity (at least 30-fold over related proteins), and demonstrated target engagement in cells [2]. In contrast, chemogenomic compounds may bind to multiple targets but are valuable due to their well-characterized target profiles, enabling target deconvolution based on selectivity patterns when used in sets [2]. The European research infrastructure EU-OPENSCREEN supports such discoveries by providing open access to high-throughput screening and medicinal chemistry expertise [20].

Core Applications of Chemogenomic Libraries

Target Deconvolution in Phenotypic Screening

Target deconvolution—identifying the molecular targets responsible for an observed phenotype—is a primary application of chemogenomic libraries. In phenotypic drug discovery, where screening does not rely on prior knowledge of specific drug targets, CG libraries enable researchers to connect phenotypic outcomes to molecular targets [4].

The fundamental principle relies on using sets of well-characterized compounds with overlapping target profiles. When multiple compounds with known but differing selectivity profiles produce a similar phenotypic outcome, researchers can deduce the specific target responsible through pattern recognition [2]. This approach has been successfully applied across diverse target families, including kinases, G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), and nuclear hormone receptors [4] [21].

Table 1: Key Components for Target Deconvolution Workflows

| Component | Description | Function in Deconvolution |

|---|---|---|

| Annotated Compound Library | Collections with known target affinities and selectivity profiles | Provides the foundational dataset for linking phenotype to target |

| Cell Painting Assay | High-content imaging-based phenotypic profiling | Generates multidimensional morphological profiles for pattern recognition |

| Network Pharmacology Database | Integrates drug-target-pathway-disease relationships | Enables systems-level analysis of compound mechanisms |

| Selectivity Panels | Assay panels testing compounds against related targets | Establishes selectivity patterns essential for confident target identification |

Polypharmacology Profiling

Polypharmacology—the rational design of small molecules that act on multiple therapeutic targets—represents a transformative approach to overcome biological redundancy, network compensation, and drug resistance [22]. Chemogenomic libraries are instrumental in profiling these multi-target activities.

Polypharmacology offers significant advantages in treating complex diseases. By simultaneously modulating several disease-relevant pathways, multi-target drugs can achieve synergistic therapeutic effects greater than single-target approaches [22]. This approach also helps mitigate drug resistance, as pathogens and cancer cells would need to simultaneously adapt to multiple inhibitory actions [22].

CG libraries enable systematic polypharmacology profiling through several mechanisms:

- Target family coverage: Designed libraries cover multiple targets within protein families, revealing inherent polypharmacology

- Cross-family screening: Testing compounds against diverse target families identifies unexpected multi-target activities

- Selectivity profiling: Comprehensive annotation reveals both primary targets and off-target effects that may contribute to efficacy or toxicity

Table 2: Polypharmacology Applications in Disease Areas

| Disease Area | Rationale for Polypharmacology | Example Targets/Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Blocks multiple oncogenic signaling pathways to prevent resistance | Kinases (PI3K/Akt/mTOR), cell cycle regulators |

| Neurodegenerative Disorders | Addresses multiple pathological processes simultaneously | Cholinesterase, β-amyloid, tau protein, oxidative stress pathways |

| Metabolic Disorders | Manages interconnected abnormalities of metabolic syndrome | GLP-1/GIP receptors, PPAR pathways |

| Infectious Diseases | Reduces resistance emergence by targeting multiple essential pathogen processes | Viral replication enzymes, host factors, bacterial cell wall synthesis |

Experimental Protocols for Library Utilization

Protocol for Phenotypic Screening with Target Deconvolution

Objective: Identify molecular targets responsible for observed phenotypic changes in disease-relevant cell models.

Materials:

- Curated chemogenomic library (e.g., 5000-compound diversity set)

- Disease-relevant cell system (primary cells, iPSC-derived cells, or engineered cell lines)

- Phenotypic readout equipment (high-content imager, plate reader)

- Cell Painting reagents if performing morphological profiling

Procedure:

- Library Preparation:

- Reformulate compounds in DMSO at standardized concentration (typically 10 mM)

- Create working stock plates using liquid handling systems

- Include appropriate controls (vehicle, positive phenotypic controls)

Cell Seeding and Compound Treatment:

- Seed cells in assay-optimized multiwell plates

- Treat with CG compounds at predetermined concentrations (typically 0.3-10 μM based on compound potency)

- Incubate for appropriate duration (typically 24-72 hours)

Phenotypic Assessment:

- For Cell Painting: Fix cells, stain with multiplexed dyes (mitochondria, ER, nucleoli, actin, Golgi, DNA), image with high-content microscope [4]

- Extract morphological features using image analysis software (e.g., CellProfiler)

- Generate phenotypic profiles for each treatment condition

Data Analysis and Target Hypothesis Generation:

- Cluster compounds based on phenotypic similarity

- Identify compounds inducing phenotype of interest

- Analyze target annotations of active compounds to identify common targets

- Use network pharmacology approaches to prioritize candidate targets

Target Validation:

- Confirm candidate targets using orthogonal approaches (genetic knockdown, selective chemical probes)

- Use additional CG compounds with overlapping selectivity profiles to strengthen evidence

Protocol for Polypharmacology Profiling

Objective: Systematically characterize multi-target activities of compounds to identify promising polypharmacological profiles.

Materials:

- Focused chemogenomic library or individual compounds of interest

- Panel of biochemical or cellular assays representing therapeutic target space

- Data integration and analysis platform

Procedure:

- Assay Selection and Validation:

- Select target panel relevant to disease biology (e.g., kinase panel for cancer, GPCR panel for CNS disorders)

- Validate assay performance (Z' factor >0.5, appropriate controls)

Compound Profiling:

- Test compounds across assay panel at multiple concentrations (typically 8-point dilution series)

- Include reference compounds with known activity profiles

- Perform replicates to ensure data quality

Data Processing and Activity Calling:

- Calculate potency (IC50, EC50, Ki) for each compound-assay pair

- Apply activity thresholds (e.g., <1 μM potency considered active)

- Correct for promiscuity and assay artifacts

Polypharmacology Profile Analysis:

- Identify compounds with desired multi-target profiles

- Assess selectivity within target families

- Use computational approaches to relate multi-target profiles to therapeutic effects

Hit Prioritization and Validation:

- Prioritize compounds with optimal polypharmacology profiles

- Validate in secondary, more physiologically relevant assays

- Assess potential for off-target toxicity

Case Studies and Implementation Examples

EUbOPEN Initiative: A Large-Scale Implementation

The EUbOPEN consortium represents a major public-private partnership advancing chemogenomics with ambitious goals to create, distribute, and annotate the largest openly available set of high-quality chemical modulators for human proteins [2]. This initiative directly supports Target 2035, a global effort to identify pharmacological modulators for most human proteins by 2035 [2].

Key outputs and methodologies include:

- A chemogenomic compound library covering one-third of the druggable proteome

- 100 chemical probes profiled in patient-derived assays

- Development of family-specific criteria for compound selection and characterization

- Technology development to shorten hit identification and hit-to-lead optimization processes

The consortium has distributed over 6000 samples of chemical probes and controls to researchers worldwide without restrictions, accelerating target validation and serving as a foundation for drug discovery [2].

NR3 Nuclear Receptor Chemogenomics Library

A recent specialized implementation developed a focused CG library for steroid hormone receptors (NR3 family) [21]. This case exemplifies the methodology for creating target-family-focused libraries:

Library Design and Curation:

- Initially identified 9,361 NR3 ligands from public databases

- Applied multi-step filtering: commercial availability, potency (≤1 μM generally, ≤10 μM for poorly covered targets), limited off-targets (≤5 annotated off-targets)

- Prioritized chemical diversity using Tanimoto similarity-based diversity picking

- Included diverse modes of action (agonist, antagonist, inverse agonist, modulator, degrader)

Experimental Characterization:

- Toxicity screening in HEK293T cells (growth rate, metabolic activity, apoptosis/necrosis induction)

- Selectivity profiling across nuclear receptor superfamily using uniform reporter gene assays

- Liability screening against promiscuous targets (kinases, bromodomains) via differential scanning fluorimetry

Final Library Composition:

- 34 compounds covering all nine NR3 receptors

- High chemical diversity (29 different scaffolds among 34 compounds)

- Multiple modes of action for each NR3 subfamily

- Recommended working concentrations (0.3-10 μM) validated for minimal toxicity

This NR3 CG library successfully identified novel roles for ERR and GR receptors in endoplasmic reticulum stress resolution, validating its utility for uncovering new biology [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomics

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | Highly selective tool compounds for target validation | Potency <100 nM, selectivity >30-fold, cell activity <1 μM [2] |

| Chemogenomic Compounds | Well-annotated multi-target compounds for deconvolution | Known target profiles, overlapping selectivities within target families [2] |

| Cell Painting Assay | High-content morphological profiling | Multiplexed staining (mitochondria, ER, nucleoli, actin, Golgi, DNA) [4] |

| Network Pharmacology Databases | Integration of drug-target-pathway-disease relationships | ChEMBL, KEGG, Gene Ontology, Disease Ontology integrated in graph databases [4] |

| Selectivity Panels | Comprehensive selectivity profiling | Family-specific assay panels (kinases, GPCRs, nuclear receptors) [2] [21] |

| Primary Patient-Derived Cells | Physiologically relevant screening systems | Inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, neurodegeneration models [2] |

Future Directions and Concluding Remarks

The field of chemogenomics continues to evolve with several emerging trends. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are increasingly applied to predict polypharmacology profiles and optimize multi-target compounds [22]. The integration of CRISPR functional genomics with small molecule screening provides orthogonal approaches to target identification and validation [18]. Furthermore, the exploration of new therapeutic modalities such as molecular glues, PROTACs, and other proximity-inducing molecules expands the druggable proteome beyond traditional targets [2].

A key challenge remains the limited coverage of even the best chemogenomic libraries, which interrogate approximately 1,000-2,000 targets out of 20,000+ human genes [18]. Initiatives like EUbOPEN that aim to cover one-third of the druggable proteome represent significant progress, but continued expansion of high-quality chemical tools is essential [2].

In conclusion, chemogenomic libraries serve as indispensable tools for bridging phenotypic observations and target-based therapeutic design. Through strategic application in target deconvolution and polypharmacology profiling, these resources accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic strategies for complex diseases. As library quality, diversity, and accessibility continue to improve through initiatives like EUbOPEN and EU-OPENSCREEN, their impact on basic research and drug development will continue to grow.

Building Your Library: Methodologies for Design, Assembly, and Data Integration

The strategic selection of chemical libraries forms the cornerstone of modern drug discovery, bridging the gap between biological complexity and therapeutic intervention. Within chemogenomic research, two principal paradigms have emerged: target-focused libraries and phenotypically-optimized libraries. These approaches represent fundamentally different philosophies in early drug discovery, each with distinct advantages, challenges, and applications [23] [24]. Target-focused libraries are collections designed to interact with a specific protein target or protein family, leveraging prior structural or ligand knowledge to enrich for bioactive compounds [25]. In contrast, phenotypically-optimized libraries are employed in a target-agnostic fashion, where compounds are selected based on their ability to modulate disease-relevant phenotypes in complex biological systems without preconceived notions of specific molecular targets [11] [10].