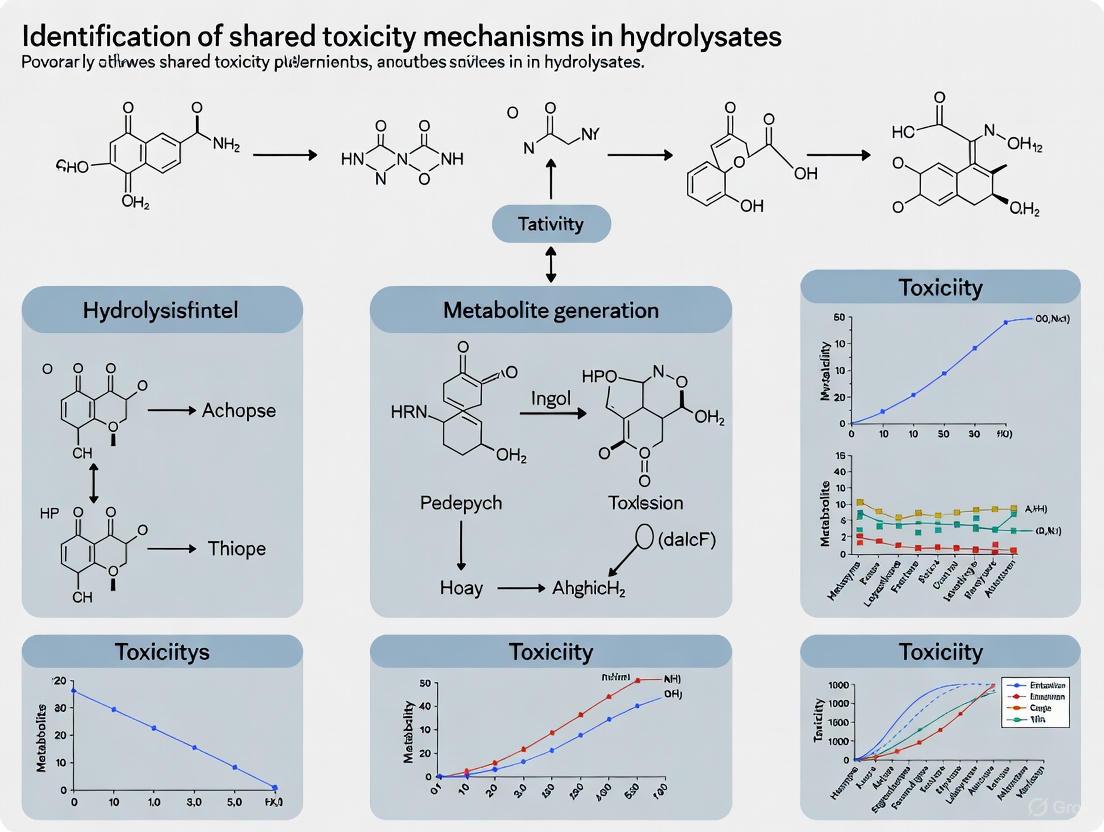

Shared Toxicity Mechanisms in Protein Hydrolysates: Identification, Analysis, and Clinical Implications for Safer Therapeutic Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on identifying and understanding shared toxicity mechanisms across different protein hydrolysates.

Shared Toxicity Mechanisms in Protein Hydrolysates: Identification, Analysis, and Clinical Implications for Safer Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on identifying and understanding shared toxicity mechanisms across different protein hydrolysates. Covering foundational concepts of hydrolysate-induced oxidative stress and cellular damage, the content explores advanced methodological approaches including proteomic and metabolomic analyses for mechanism identification. It addresses critical troubleshooting strategies for mitigating toxicity while preserving bioactivity, and examines validation frameworks through comparative toxicological assessments. By synthesizing current research findings and emerging trends, this resource aims to support the development of safer hydrolysate-based therapeutics through mechanistic understanding and risk mitigation.

Fundamental Toxicity Pathways: Understanding Hydrolysate-Induced Cellular Stress and Damage Mechanisms

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation and Oxidative Stress Induction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (O₂) and water, playing a dual role in biological systems as both deleterious molecules and crucial signaling agents [1]. In the context of hydrolysates research, understanding ROS generation and the subsequent induction of oxidative stress is paramount for identifying shared toxicity mechanisms. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the core principles, methodologies, and signaling pathways associated with ROS, framed specifically for researchers investigating the safety and biological effects of protein hydrolysates.

The Chemistry and Biology of ROS

Inventory of Key ROS

ROS encompass a variety of radical and non-radical oxygen derivatives. The most biologically significant ROS include [2] [1]:

- Superoxide anion (O₂·⁻): A free radical produced predominantly by the electron transport chain in mitochondria and by NADPH oxidases (NOXs) [2] [3].

- Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂): A non-radical molecule generated from the dismutation of superoxide. It is more stable than other ROS and can diffuse across membranes, functioning as a signaling molecule [2] [1].

- Hydroxyl radical (·OH): The most powerful and reactive ROS oxidant, with a very short half-life (10⁻⁹ s). It is formed via the Fenton reaction or the Haber-Weiss reaction and causes severe damage to cellular components [2] [4].

- Singlet oxygen (¹O₂): An excited, highly reactive form of oxygen often generated in chloroplasts and by photosensitizers [1].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Reactive Oxygen Species

| ROS Species | Chemical Nature | Half-Life | Primary Sources | Reactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide (O₂·⁻) | Free radical | 10⁻⁶ seconds | Mitochondrial ETC, NOX enzymes | Moderate |

| Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) | Non-radical | 10⁻³ seconds | Superoxide dismutation, various oxidases | Low-moderate |

| Hydroxyl radical (·OH) | Free radical | 10⁻⁹ seconds | Fenton reaction, water radiolysis | Very high |

| Singlet oxygen (¹O₂) | Excited state | 10⁻⁶ seconds | Photosensitization, chloroplasts | High |

Cells generate ROS through both metabolic processes (endogenous sources) and external factors (exogenous sources).

Endogenous Sources:

- Mitochondrial Respiration: The electron transport chain (ETC) is a major source, particularly at Complexes I and III, where an estimated 0.1-2% of electrons leak and prematurely reduce oxygen to superoxide anion [2] [1].

- Enzymatic Reactions: Enzymes such as NADPH oxidases (NOXs), xanthine oxidase, cytochrome P450 mono-oxygenases, and nitric oxide synthases actively produce ROS as part of their catalytic cycles [2] [5].

- Peroxisomes: These organelles generate H₂O₂ as a by-product of fatty acid beta-oxidation [2].

- Endoplasmic Reticulum: Protein folding and disulfide bond formation can lead to ROS production [2].

Exogenous Sources:

- Ionizing Radiation: Can generate damaging intermediates through water radiolysis, producing hydroxyl radicals and other ROS [1] [4].

- Environmental Stressors: Pollutants, heavy metals, cigarette smoke, drugs, and pesticides can stimulate ROS formation [1].

- UV Radiation: Can lead to ROS generation through photosensitization reactions [2].

ROS and Oxidative Stress: Molecular Mechanisms

The Dual Role of ROS: Physiological Signaling vs. Pathological Damage

ROS exhibit a dual nature in biological systems, functioning as essential signaling molecules at low levels but causing damage at high concentrations [2] [3].

Physiological Roles:

- Redox Signaling: At low concentrations, ROS, particularly H₂O₂, act as second messengers in cellular signaling pathways, regulating processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and immune response [3] [6].

- Immune Function: Phagocytes release ROS in large quantities to destroy invading pathogens [2] [5]. ROS also regulate immune cell signaling, including macrophage polarization and neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation [3].

Pathological Consequences - Oxidative Stress: Oxidative stress occurs when ROS production overwhelms the cellular antioxidant defense systems, leading to damage of key biomolecules [2] [3]:

- Lipid Peroxidation: ROS attack polyunsaturated fatty acids in membrane phospholipids, disrupting membrane integrity and generating reactive aldehydes that can propagate oxidative damage [2] [5].

- Protein Oxidation: ROS oxidize amino acid side chains, leading to protein fragmentation, aggregation, loss of enzyme activity, and disruption of metabolic pathways [2] [5].

- DNA Damage: ROS cause oxidative modifications to DNA bases (e.g., in guanine) and deoxyribose sugar, leading to strand breaks and mutations that can contribute to carcinogenesis and aging [2] [4].

Key Signaling Pathways in Oxidative Stress

ROS modulate numerous signaling pathways that influence cell fate, including survival, proliferation, and death. The following diagram illustrates the major pathways regulated by ROS.

The nuclear factor-erythroid factor 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway is one of the major cellular defense mechanisms against oxidative stress. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is bound to Keap1 in the cytoplasm and targeted for degradation. Upon oxidative stress, Nrf2 dissociates from Keap1, translocates to the nucleus, and activates the transcription of antioxidant response element (ARE)-containing genes, including glutathione S-transferases, NADPH quinone oxidoreductase, and heme oxygenase-1 [3] [4].

High levels of ROS activate cell death pathways, primarily apoptosis, through multiple mechanisms [6]:

- Mitochondrial Pathway: ROS induce mitochondrial membrane permeabilization, leading to the release of cytochrome c and activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3.

- Death Receptor Pathway: ROS can enhance the expression of death receptors and ligands, such as Fas and TNF-α, initiating the extrinsic apoptosis pathway.

- Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress: ROS disrupt protein folding in the ER, triggering the unfolded protein response (UPR) which can culminate in apoptosis if the stress is severe or prolonged.

Antioxidant Defense Systems

Cells maintain redox homeostasis through an intricate network of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems.

Table 2: Major Antioxidant Defense Systems

| Antioxidant System | Key Components | Cellular Location | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) | SOD1 (Cu/Zn-SOD), SOD2 (Mn-SOD), SOD3 (EC-SOD) | Cytoplasm, Mitochondria, Extracellular | Catalyzes dismutation of O₂·⁻ to H₂O₂ and O₂ [2] [4] |

| Glutathione System | Glutathione (GSH), Glutathione Peroxidases (GPX), Glutathione Reductase (GR) | Cytoplasm, Mitochondria | GPX reduces H₂O₂ and lipid hydroperoxides to water/alcohols using GSH; GR regenerates GSH from GSSG [3] [4] |

| Thioredoxin System | Thioredoxin (Trx), Thioredoxin Reductase (TrxR), NADPH | Cytoplasm, Mitochondria | Trx donates electrons to peroxiredoxins (Prx) to reduce H₂O₂; TrxR regenerates reduced Trx [4] |

| Catalase | CAT | Peroxisomes | Converts H₂O₂ to water and oxygen [3] [4] |

| Non-Enzymatic Antioxidants | Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Carotenoids, Flavonoids | Various compartments | Scavenge ROS directly, act as chain-breaking antioxidants in lipid peroxidation [5] [7] |

The glutathione and thioredoxin systems function in parallel and exhibit significant crosstalk, with components of one system potentially backing up the other during oxidative stress [4].

Experimental Assessment of ROS and Oxidative Stress

Methodologies for ROS Detection

Accurate detection and quantification of ROS are technically challenging due to their short half-lives and high reactivity. The following experimental workflow outlines a comprehensive approach for assessing ROS and oxidative stress in cellular models, particularly relevant for hydrolysates research.

Fluorescent Probes for ROS Detection:

- DCFDA (2',7'-Dichlorofluorescin diacetate): A cell-permeable dye that is deacetylated by cellular esterases and then oxidized primarily by H₂O₂ to form the fluorescent DCF, used for measuring general oxidative stress [8] [9] [10].

- Dihydroethidium (DHE) and MitoSOX Red: Specifically detect superoxide anion. DHE is used for cytosolic superoxide, while MitoSOX Red targets mitochondrial superoxide [9].

Biomarkers of Oxidative Damage:

- Lipid Peroxidation Products: Malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) are common markers measured by TBARS assay or HPLC [2] [5].

- Protein Carbonyls: Formed by oxidative modification of amino acid side chains, detectable by DNPH assay and Western blotting [2] [5].

- Oxidized DNA Bases: 8-Hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) is a prominent marker of DNA oxidation, measurable by ELISA or HPLC-MS [2] [5].

Cellular Antioxidant Activity Assays

For hydrolysates research, assessing cellular antioxidant activity is crucial for understanding potential protective effects. The following protocol is adapted from studies on protein hydrolysates from various sources [8] [9] [10]:

Protocol: Cellular Antioxidant Activity in Human Cell Lines

- Cell Culture: Maintain human cell lines (e.g., HepG2 hepatocarcinoma, Caco-2 colorectal adenocarcinoma, or HaCaT keratinocytes) in appropriate media.

- Pre-treatment: Incubate cells with various concentrations of the protein hydrolysate or peptide fractions for a defined period (e.g., 4-24 hours).

- Oxidative Stress Induction: Expose cells to an oxidative stressor such as H₂O₂ (e.g., 200-1000 µM) or an organic hydroperoxide for 1-6 hours.

- ROS Measurement:

- Wash cells with PBS and load with DCFDA (10-20 µM) in serum-free media for 30-60 minutes at 37°C.

- After washing, measure fluorescence (Ex/Em: 485/535 nm) using a microplate reader.

- Express results as percentage reduction in fluorescence compared to stressed but untreated controls.

- Cell Viability Assessment: Perform parallel experiments using MTT or similar assays to ensure that observed effects are not due to cytotoxicity.

- Mechanistic Studies:

- Analyze antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, CAT, GPx) using commercial kits.

- Measure glutathione levels (GSH/GSSG ratio) spectrophotometrically or fluorometrically.

- Evaluate activation of cytoprotective pathways (e.g., Nrf2 nuclear translocation by Western blotting).

Research Reagent Solutions for ROS Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ROS and Oxidative Stress Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| ROS Detection Probes | DCFDA, Dihydroethidium (DHE), MitoSOX Red, Amplex Red | Detection and quantification of specific ROS in cellular systems [8] [9] [10] |

| Oxidative Stress Inducers | Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), tert-Butyl hydroperoxide (tBHP), Menadione, Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Induction of controlled oxidative stress in experimental models [9] [10] |

| Antioxidant Enzyme Assay Kits | Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Assay Kit, Catalase Assay Kit, Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) Assay Kit | Quantification of antioxidant enzyme activities in cell lysates or tissues [3] [4] |

| Biomarker Detection Kits | Lipid Peroxidation (MDA) Assay Kit, Protein Carbonyl Content Assay Kit, 8-OHdG ELISA Kit | Measurement of oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA [2] [5] |

| Cell Viability Assays | MTT, WST-1, LDH Release Assay | Assessment of cytotoxicity and cell death in response to oxidative stress [9] |

| Western Blot Antibodies | Anti-Nrf2, Anti-HO-1, Anti-NF-κB, Anti-NLRP3, Anti-phospho Histone H2A.X | Analysis of oxidative stress signaling pathways and DNA damage response [3] [4] [10] |

Applications in Hydrolysates Research

In the context of hydrolysates research, the assessment of ROS generation and oxidative stress is critical for identifying potential toxicity mechanisms. Studies on protein hydrolysates from various sources (e.g., shrimp by-products, chickpea, jackfruit, moringa) have demonstrated both antioxidant and pro-oxidant effects, highlighting the importance of comprehensive ROS profiling [8] [9] [10].

Key considerations for hydrolysates research include:

- Dose-Dependent Effects: Low doses of hydrolysates may exhibit antioxidant properties and activate cytoprotective pathways like Nrf2, while high doses might induce oxidative stress and activate apoptotic pathways [9] [10] [6].

- Cellular Bioavailability: The structure, size, charge, and hydrophobicity of peptides influence their cellular uptake and intracellular localization, ultimately determining their biological effects [9].

- Dual ROS-Modulating Effects: Some hydrolysates may increase basal ROS levels to activate adaptive stress response pathways while simultaneously protecting against exogenous oxidative stress, a phenomenon known as hormesis [10].

Understanding these complex interactions between protein hydrolysates and cellular redox systems is essential for evaluating their safety and potential therapeutic applications while identifying shared toxicity mechanisms across different hydrolysate sources.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Membrane Potential Alteration

Mitochondrial dysfunction represents a convergent pathological mechanism across numerous human diseases, characterized fundamentally by the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). This critical parameter serves as both a key indicator of mitochondrial health and a central regulator of essential cellular processes, including ATP production, calcium homeostasis, and apoptotic signaling. Within the context of hydrolysates research, understanding ΔΨm alteration provides crucial insights into shared toxicity mechanisms, enabling more accurate safety assessments and therapeutic interventions. This technical guide comprehensively examines the molecular basis of ΔΨm, detailed methodologies for its assessment, and the intricate signaling pathways involved in its disruption, providing researchers with standardized protocols for evaluating mitochondrial toxicity mechanisms.

The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is the electrical gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), generated by the proton translocation activity of the electron transport chain (ETC). This electrochemical gradient, typically ranging from -150 to -180 mV (negative inside), represents a fundamental component of the proton motive force that drives ATP synthesis through FO F1 ATP synthase [11] [12]. As the primary indicator of mitochondrial functional status, ΔΨm reflects the integration of multiple physiological processes, including ETC efficiency, substrate availability, and membrane integrity.

Beyond its bioenergetic role, ΔΨm regulates critical cellular functions such as calcium buffering capacity, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and initiation of apoptotic pathways. The collapse of ΔΨm frequently serves as an early indicator of mitochondrial dysfunction preceding irreversible cellular damage [12] [13]. In toxicity studies, particularly involving hydrolysates, ΔΨm alteration provides a sensitive metric for identifying compromised cellular viability and understanding shared mechanisms of toxic action, including disrupted energy transduction, oxidative stress, and activation of programmed cell death pathways.

Molecular Mechanisms of Membrane Potential Generation and Maintenance

Thermodynamic Basis of ΔΨm Formation

The establishment of ΔΨm originates from the chemiosmotic principle wherein electron flow through ETC complexes I, III, and IV drives vectorial proton translocation from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space. This creates both an electrical gradient (ΔΨ) and a chemical proton gradient (ΔpH), collectively comprising the proton motive force (Δp) according to the equation:

Δp = ΔΨ - 2.303(RT/F)ΔpH

Where R is the gas constant, T is temperature, and F is Faraday's constant. In most cells, ΔΨ constitutes the dominant component (approximately 80%) of the total proton motive force [11] [12]. The integrity of this potential is maintained by the exceptional impermeability of the IMM to ions, which prevents short-circuiting of the electrochemical gradient.

Structural Determinants of ΔΨm Stability

The architectural organization of mitochondrial membranes plays a crucial role in maintaining ΔΨm. The inner mitochondrial membrane exhibits distinctive lipid composition, rich in cardiolipin, a unique phospholipid that optimizes the stability and function of ETC supercomplexes [12] [13]. The cristae architecture, maintained by proteins such as OPA1, creates specialized compartments that enhance the efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation and protect against ΔΨm dissipation [14] [15].

Table 1: Key Protein Complexes Involved in ΔΨm Generation and Regulation

| Complex/Protein | Localization | Primary Function | Impact on ΔΨm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) | IMM | Electron transfer from NADH to ubiquinone; proton translocation | Primary generator |

| Complex III (Cytochrome bc1 complex) | IMM | Electron transfer from ubiquinol to cytochrome c; proton translocation | Primary generator |

| Complex IV (Cytochrome c oxidase) | IMM | Electron transfer from cytochrome c to oxygen; proton translocation | Primary generator |

| ATP synthase (Complex V) | IMM | ATP synthesis coupled to proton influx | Primary consumer |

| ANT (Adenine nucleotide translocator) | IMM | ATP/ADP exchange across IMM | Modulator |

| Uncoupling proteins (UCPs) | IMM | Proton leak, thermogenesis | Dissipator |

| mPTP (Mitochondrial permeability transition pore) | IMM | Non-selective channel opening under stress | Collapse |

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of ΔΨm Alteration

Direct Toxic Insults to Electron Transport Chain

Multiple toxicity mechanisms converge on ΔΨm disruption through direct inhibition of ETC complexes. Hydrolysates may contain compounds that specifically target complex I (e.g., rotenone-like substances) or complex III (e.g., antimycin analogs), blocking electron flow and consequently impairing proton pumping [12] [13]. Additionally, numerous toxicants uncouple oxidative phosphorylation by increasing proton permeability of the IMM, dissipating ΔΨm without affecting electron transport, ultimately depleting cellular ATP reserves despite elevated oxygen consumption [16] [13].

Lipophilic compounds present in certain hydrolysates can accumulate in mitochondrial membranes, disrupting lipid-protein interactions essential for ETC function. Research demonstrates that hydrocarbons and other lipophilic substances integrate into the membrane lipid bilayer, compromising structural integrity and increasing non-specific permeability to protons and ions [16] [17]. This membrane-embedded toxicity represents a shared mechanism particularly relevant in hydrolysates containing organic solvents or amphiphilic compounds.

Oxidative Stress and ΔΨm Collapse

The intimate relationship between ΔΨm and ROS production creates a self-amplifying cycle of mitochondrial dysfunction. At high ΔΨm values (above -140 mV), electron transport slows, increasing the probability of electron leakage from ETC complexes and superoxide formation [12] [13]. Elevated ROS subsequently damages ETC components, lipid membranes (particularly cardiolipin), and mtDNA, further compromising ΔΨm generation. This vicious cycle represents a common final pathway in many toxicity paradigms, including those relevant to hydrolysates research.

Oxidative modification of cardiolipin deserves special emphasis, as this mitochondria-specific phospholipid is essential for maintaining cristae structure and the functional integrity of ETC supercomplexes. Peroxidation of its unsaturated fatty acid chains diminishes respiratory efficiency and promotes cytochrome c release, initiating apoptotic cascades [12] [13].

Mitochondrial Permeability Transition

Calcium overload coupled with oxidative stress triggers opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), a non-selective channel that permits uncontrolled flux of molecules <1.5 kDa across the IMM. This catastrophic event causes immediate ΔΨm collapse, osmotic swelling, and rupture of the outer mitochondrial membrane, culminating in necrotic cell death or apoptosis through cytochrome c release [12] [15]. Numerous toxic compounds in hydrolysates can promote mPTP opening either directly or indirectly through calcium dyshomeostasis, establishing this mechanism as a critical endpoint in toxicity assessment.

Diagram 1: Integrated Pathway of ΔΨm Collapse via mPTP Opening. This diagram illustrates the convergence of multiple toxic insults on mitochondrial permeability transition, culminating in ΔΨm collapse and cell death.

Experimental Methodologies for Assessing ΔΨm

Fluorescence-Based Approaches

Fluorometric assays represent the most accessible and widely implemented methodology for ΔΨm assessment in live cells. These approaches utilize potential-sensitive dyes that accumulate in mitochondria in a ΔΨm-dependent manner, with fluorescence intensity, quenching, or spectral shifts providing quantitative and semi-quantitative measurements [12] [18].

JC-10/JC-1 Assay Protocol:

- Principle: JC-10 and its analog JC-1 exist as green fluorescent monomers at low concentrations or low ΔΨm, but form red fluorescent J-aggregates upon accumulation in energized mitochondria. The red/green fluorescence ratio provides a semi-quantitative measure of ΔΨm independent of mitochondrial mass.

- Staining Solution: Prepare 5-10 μM JC-10 in DMSO, dilute in assay buffer to final concentration of 2-5 μM.

- Loading Conditions: Incubate cells for 20-30 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Washing: Replace dye-containing medium with fresh pre-warmed buffer.

- Measurement: Excite at 490 nm, measure emission at 530 nm (monomer) and 590 nm (J-aggregates).

- Controls: Include CCCP (10-20 μM) or FCCP (1-5 μM) as depolarization controls.

- Normalization: Calculate ratio of aggregate (red) to monomer (green) fluorescence. Report values as percentage of control treatments [18].

TMRM/TMRE Assay Protocol:

- Principle: These cationic dyes distribute between mitochondria and cytosol according to the Nernst equation, with accumulation proportional to ΔΨm. Quenching mode implementation provides more quantitative measurements.

- Staining Solution: Prepare 20-200 nM TMRM in assay buffer. For quenching mode, use higher concentrations (100-500 nM).

- Loading Conditions: Incubate for 20-60 minutes at 37°C.

- Measurement: Excite at 548 nm, measure emission at 574 nm.

- Quenching Mode Verification: Apply FCCP/CCCP at end of experiment - fluorescence should decrease by >60% for valid quenching conditions.

- Calibration: For absolute ΔΨm determination, use a K+ gradient with valinomycin according to the Nernst equation [18].

Ratiometric Pericam Protocol:

- Principle: Genetically encoded sensors provide compartment-specific ΔΨm measurement without dye loading variability.

- Transfection: Express mitochondrial-targeted rationetric pericam using appropriate transfection method.

- Measurement: Alternate excitation at 410 nm and 485 nm, measure emission at 535 nm.

- Calculation: Determine 485/410 nm excitation ratio.

- Advantages: Cell-specific expression, sub-mitochondrial localization, long-term monitoring capability [18].

Table 2: Comparison of Fluorescent ΔΨm Indicators

| Parameter | JC-10/JC-1 | TMRM/TMRE | Rhodamine 123 | Mitotracker CMXRos |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Mode | Ratiometric | Intensity/Quenching | Intensity | Intensity |

| Excitation/Emission | 514/529,585 | 548/574 | 507/529 | 579/599 |

| ΔΨm Sensitivity | High | High | Medium | Low-Medium |

| Photostability | Medium | High | Low | High |

| Toxicity | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Quantitative Potential | Semi-quantitative | Quantitative | Semi-quantitative | Qualitative |

| Recommended Use | Screening | Quantitative analysis | Kinetic studies | Fixed-cell imaging |

Oxygen Consumption Measurements

Respiratory parameters provide indirect but complementary information about ΔΨm through assessment of ETC function. Using high-resolution respirometry, sequential substrate-uncoupler-inhibitor titration (SUIT) protocols can distinguish between different states of mitochondrial respiration and their relationship to ΔΨm [18] [13].

Standardized SUIT Protocol for ΔΨm Assessment:

- Basal Respiration: Measure in glucose-containing medium.

- ATP-Linked Respiration: Add oligomycin (1-2 μg/mL) to inhibit ATP synthase.

- Maximal Respiratory Capacity: Titrate FCCP (0.5-2 μM) to induce maximal electron flow.

- Non-Mitochondrial Respiration: Apply rotenone (0.5 μM) + antimycin A (2.5 μM).

- Calculation: ATP-linked respiration = (Basal - Oligomycin); Proton leak = (Oligomycin - Non-mitochondrial); Spare respiratory capacity = (FCCP - Basal).

The LEAK respiration state (after oligomycin) reflects proton conductance across the IMM, directly correlating with ΔΨm maintenance costs. A high LEAK/respiration ratio indicates compromised coupling efficiency and potential ΔΨm instability [18].

Advanced Integrated Workflow for Comprehensive ΔΨm Assessment

A systematic, multi-parameter approach provides the most robust assessment of ΔΨm alterations in toxicity studies. The following integrated workflow combines complementary techniques to distinguish primary ΔΨm defects from secondary consequences of mitochondrial damage.

Diagram 2: Integrated Experimental Workflow for ΔΨm Assessment in Toxicity Studies. This workflow outlines a systematic approach for comprehensive evaluation of mitochondrial dysfunction mechanisms.

Research Reagent Solutions for ΔΨm Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ΔΨm Assessment

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔΨm-Sensitive Dyes | JC-10, TMRM, TMRE, Rhodamine 123 | Fluorescent indicators of mitochondrial polarization | JC-10 preferred for ratiometric measurements; TMRM for quantitative applications |

| ETC Inhibitors | Rotenone (Complex I), Antimycin A (Complex III), Oligomycin (ATP synthase) | Selective inhibition of respiratory complexes | Essential for mechanistic studies and assay validation |

| Uncouplers | FCCP, CCCP | Dissipate ΔΨm by increasing H+ permeability | Positive controls for depolarization; titration required |

| Ionophores | Valinomycin (K+), Ionomycin (Ca2+) | Modulate ion gradients across IMM | Valinomycin used for ΔΨm calibration |

| mPTP Inducers | Calcium chloride, phenylarsine oxide | Promote permeability transition | Study catastrophic ΔΨm collapse |

| Antioxidants | MitoTEMPO, MitoQ | Mitochondria-targeted ROS scavengers | Distinguish oxidative vs. non-oxidative mechanisms |

| Fluorometric Assay Kits | Commercial ΔΨm kits (Abcam, Cayman, ThermoFisher) | Standardized reagent systems | Improve reproducibility across laboratories |

| Genetically Encoded Probes | mt-cpYFP, CEPIA | Ratiometric ΔΨm sensors | Enable long-term monitoring in specific cell populations |

Data Interpretation and Integration Framework

Classification of ΔΨm Alteration Patterns

Systematic analysis of ΔΨm data in conjunction with complementary parameters enables discrimination between distinct toxicity mechanisms:

Primary ETC Inhibition Pattern:

- Characteristics: Immediate ΔΨm depolarization, proportional reduction in oxygen consumption, minimal ROS increase

- Associated Findings: Specific complex inhibition, preserved membrane integrity

- Interpretation: Direct inhibition of respiratory complexes by toxic compounds [12] [13]

Uncoupling Pattern:

- Characteristics: ΔΨm depolarization with stimulated oxygen consumption, elevated ROS production

- Associated Findings: Intact ETC function, reduced ATP synthesis efficiency

- Interpretation: Increased proton conductance across IMM [16] [13]

Oxidative Stress-Induced Pattern:

- Characteristics: Gradual ΔΨm loss preceded by ROS elevation, cardiolipin peroxidation

- Associated Findings: Secondary complex inhibition, glutathione depletion

- Interpretation: Self-amplifying cycle of oxidative damage [12] [13]

mPTP-Mediated Pattern:

- Characteristics: Abrupt, complete ΔΨm collapse, mitochondrial swelling

- Associated Findings: Calcium dysregulation, cytochrome c release

- Interpretation: Activation of permeability transition [12] [15]

Normalization Strategies and Quality Controls

Appropriate normalization is critical for meaningful ΔΨm interpretation:

- Mitochondrial Mass Normalization: Use citrate synthase activity or mitochondrial protein content

- Cell Number Normalization: Employ nuclear stains or total protein quantification

- Reference Standards: Include plate-based controls with established depolarizing agents

- Viability Correlation: Always correlate ΔΨm changes with cell viability assays

- Kinetic Monitoring: Prefer time-course measurements over single endpoints

Rigorous quality control should include:

- Verification of dye responsiveness using FCCP/CCCP validation

- Assessment of dye toxicity during incubation periods

- Confirmation of mitochondrial localization using compartment-specific markers

- Demonstration of assay linearity with cell number [18]

Mitochondrial membrane potential serves as a central integrator of mitochondrial functional status and a sensitive indicator of toxic insult. Within hydrolysates research, standardized assessment of ΔΨm alterations provides critical insights into shared toxicity mechanisms, enabling evidence-based risk assessment and targeted therapeutic interventions. The multiparameter framework outlined in this technical guide facilitates comprehensive characterization of ΔΨm pathology, distinguishing between distinct mechanisms of dysfunction and placing individual findings within a broader mechanistic context. As research advances, continued refinement of ΔΨm assessment methodologies will further enhance our understanding of mitochondrial toxicity pathways and strengthen the scientific foundation for safety evaluation in hydrolysates and related compounds.

Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, is a genetically regulated process essential for embryonic development, tissue homeostasis, and the elimination of damaged or unnecessary cells in multicellular organisms [19] [20]. This highly controlled process operates through two principal signaling pathways: the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway and the extrinsic (death receptor) pathway [19] [21] [20]. Both pathways converge to activate a cascade of proteases known as caspases, which execute the orderly dismantling of cellular components [22] [23]. The precise regulation of these mechanisms is crucial for health, and their dysregulation is implicated in a wide range of diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and autoimmune diseases [19] [20]. Understanding the molecular specifics of intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis activation is fundamental for identifying shared toxicity mechanisms in hydrolysates research.

Core Apoptotic Pathways: Molecular Mechanisms

The Extrinsic (Death Receptor) Pathway

The extrinsic pathway is initiated by the binding of specific death ligands from the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily to their corresponding death receptors on the cell surface [19] [21]. Ligands such as Fas Ligand (FasL) or TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) bind to receptors like Fas (CD95) or DR4/DR5, respectively [19] [21].

Upon ligand binding, the receptors recruit the adapter protein FADD (Fas-associated protein with death domain), which then recruits procaspase-8 [21]. This multi-protein complex forms the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) [21]. Within the DISC, caspase-8 undergoes autocatalytic activation [21]. A key regulatory component of this complex is cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (c-FLIP), which can competitively inhibit caspase-8 recruitment and modulate DISC activity [21].

Activated caspase-8 (an initiator caspase) then directly cleaves and activates executioner caspases (caspase-3 and -7), propagating the death signal [19].

The Intrinsic (Mitochondrial) Pathway

The intrinsic pathway is activated in response to intracellular stress signals, including DNA damage, oxidative stress, growth factor withdrawal, and cytotoxic insults [19] [21]. These stimuli are monitored and integrated by the Bcl-2 family of proteins, which act as critical regulators of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) [19] [21] [24].

The Bcl-2 family comprises both pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic members [21]. In response to cellular stress, pro-apoptotic "BH3-only" proteins (such as Bim, Bid, and Puma) are activated and neutralize the function of anti-apoptotic proteins (like Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL) [21]. This allows the pro-apoptotic effectors Bax and Bak to oligomerize and form pores in the mitochondrial outer membrane [21].

This pivotal event, MOMP, leads to the release of several pro-apoptotic proteins from the mitochondrial intermembrane space into the cytosol [19]. Key among these is cytochrome c [19] [24]. Once in the cytosol, cytochrome c binds to Apoptotic Protease-Activating Factor 1 (Apaf-1), triggering the formation of a multi-protein complex called the apoptosome [21]. The apoptosome recruits and activates the initiator caspase-9 [19] [21].

Pathway Integration and Execution

The intrinsic and extrinsic pathways are not isolated; they interconnect significantly, primarily through the BH3-only protein Bid [21]. Active caspase-8 from the extrinsic pathway can cleave Bid into its active form, tBid (truncated Bid) [21]. tBid then translocates to the mitochondria, where it promotes MOMP by activating Bax/Bak, thereby amplifying the apoptotic signal through the intrinsic pathway [21].

Regardless of the initiation route, both pathways converge on the activation of executioner caspases, primarily caspase-3, -6, and -7 [19] [20]. These enzymes orchestrate the systematic cleavage of a wide array of cellular substrates, leading to the characteristic morphological hallmarks of apoptosis, including chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and formation of apoptotic bodies [19] [20].

Table 1: Key Components of the Extrinsic and Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathways

| Pathway Component | Key Molecules | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Extrinsic Initiators | FasL, TRAIL, TNF-α | Death ligands that bind cell surface receptors [19] [21]. |

| Death Receptors | Fas (CD95), DR4/DR5, TNFR1 | Transmembrane receptors that transmit death signals upon ligand binding [21] [20]. |

| Signaling Complex | FADD, procaspase-8, c-FLIP | Forms the DISC, leading to caspase-8 activation [21]. |

| Intrinsic Regulators | Bcl-2, Bcl-xL (anti-apoptotic); Bax, Bak, Bim, Bid (pro-apoptotic) | Govern mitochondrial membrane integrity and MOMP [19] [21]. |

| Mitochondrial Signal | Cytochrome c, Smac/DIABLO | Released upon MOMP; activates caspases and inhibits IAPs [19]. |

| Signaling Complex | Apaf-1, cytochrome c, procaspase-9 | Forms the apoptosome, leading to caspase-9 activation [21]. |

| Executioner Caspases | Caspase-3, -6, -7 | Proteases that dismantle the cell by cleaving structural and functional proteins [19] [20]. |

Experimental Analysis of Apoptotic Pathways

Detecting and quantifying apoptosis is crucial for evaluating the toxicity of hydrolysates and other compounds. A multi-parametric approach is recommended to confirm activation and identify the involved pathway.

Core Methodologies and Workflow

Experimental analysis typically involves exposing a relevant cell line to the agent of interest (e.g., a hydrolysate) and subsequently assessing multiple apoptotic markers using techniques outlined below. The workflow often proceeds from initial viability and caspase assays to more specific analyses of pathway components and mitochondrial health.

Key Analytical Assays

The following assays are fundamental for characterizing apoptotic response in toxicity studies.

Table 2: Key Experimental Assays for Apoptosis Detection

| Assay Target | Method | Measurable Outputs | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability | MTT, XTT, ATP-based luminescence | Metabolic activity / ATP content | General cytotoxicity; decreased signal indicates cell death or metabolic inhibition [19]. |

| Caspase Activation | Fluorometric/luminescent assays using caspase-specific substrates (e.g., DEVD for caspase-3) | Caspase-3/7, -8, or -9 activity | Confirms apoptosis execution; caspase-8 implicates extrinsic, caspase-9 intrinsic pathway [19] [25]. |

| Membrane Integrity | Annexin V / Propidium Iodide (PI) staining by flow cytometry | Phosphatidylserine externalization (Annexin V+) and membrane integrity (PI+) | Distinguishes early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-) from late apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+/PI+) cells [20]. |

| Mitochondrial Function | JC-1 dye (flow cytometry/ microscopy), Cytochrome c immunofluorescence | Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), Cytochrome c localization | Loss of ΔΨm and cyt c release from mitochondria are hallmarks of intrinsic pathway activation [19] [24]. |

| Protein Expression & Cleavage | Western Blotting | Protein levels and cleavage products (e.g., Bcl-2/Bax ratio, PARP cleavage, caspase processing) | Defines molecular mechanisms; e.g., Bcl-2 downregulation suggests intrinsic pathway involvement [25]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This section details essential reagents and tools used in apoptosis research, particularly for investigating toxicity mechanisms.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Apoptosis Studies

| Reagent / Assay Kit | Primary Function / Target | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Death Ligands (e.g., FasL, TRAIL) | Activate specific death receptors on the cell surface [21]. | Selective induction of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway for mechanistic studies and positive controls. |

| Caspase Inhibitors (e.g., Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase), Z-DEVD-FMK (caspase-3)) | Irreversibly bind to the active site of caspases, inhibiting their proteolytic activity [19]. | To confirm caspase-dependent apoptosis and delineate the role of specific caspases in cell death. |

| JC-1 Dye | A fluorescent cationic dye that accumulates in mitochondria, forming aggregates (red fluorescence) in healthy cells and monomers (green) upon depolarization [19]. | To measure mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), a key early event in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. |

| Annexin V Binding Kits (often with Propidium Iodide) | Annexin V binds to phosphatidylserine (PS) exposed on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane in early apoptosis [20]. | To detect and quantify apoptosis by flow cytometry or microscopy, distinguishing stages of cell death. |

| Antibodies for Western Blot (e.g., anti-Bcl-2, anti-Bax, anti-cleaved caspase-3, anti-cleaved PARP, anti-cytochrome c) | Detect specific proteins, their post-translational modifications, and cleavage events indicative of apoptosis [25]. | To analyze expression levels of regulatory proteins and confirm activation of apoptotic executioners. |

| GSH/GSSG Assay Kit | Measures the ratio of reduced glutathione (GSH) to oxidized glutathione (GSSG), a key indicator of cellular redox state [25]. | To investigate oxidative stress, which is a common activator of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. |

Pathway Crosstalk and Broader Context

While apoptosis is a defined pathway, it does not operate in isolation. Cross-talk with other cell death forms is a critical consideration in toxicity studies. For instance, caspase-8 acts as a switch; its inhibition can shift cell fate from apoptosis to necroptosis, another form of regulated cell death [22] [23]. Furthermore, apoptotic caspases like caspase-3 can cleave gasdermin E (GSDME), leading to pyroptosis-like secondary necrosis and inflammation, blurring the lines between apoptotic and lytic cell death [22]. Recent research also highlights PANoptosis, an integrated inflammatory cell death pathway involving components from apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis, which may be relevant in complex toxicological responses [22].

The following diagram summarizes the key steps and major molecular players in the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways, illustrating their convergence point.

Cellular Membrane Integrity Compromise and Permeability Changes

Cellular membrane integrity is fundamental to maintaining homeostasis, and its compromise is a critical mechanism of toxicity in various pathological conditions, including the response to microbial toxins. Within hydrolysates research, identifying shared toxicity mechanisms often centers on understanding how bioactive components disrupt this vital barrier. The systemic response to severe infection, or sepsis, provides a powerful model for studying these events, as it involves well-characterized pathways of membrane disruption and permeability changes initiated by bacterial endotoxins. This guide details the mechanisms, assessment methodologies, and key reagents relevant to this field, providing a framework that can be applied to the investigation of hydrolysate-induced toxicity.

Core Mechanisms of Membrane Disruption

The compromise of cellular membranes, particularly in endothelial cells that form the vascular barrier, is a primary event in systemic intoxication. The following core mechanisms are central to this process.

Oxidative Stress and Lipid Peroxidation

A primary mechanism disrupting membrane integrity is oxidative stress, characterized by an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defenses [26] [27]. During the cellular response to pathogens, enzymes like NADPH oxidase and the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) generate large amounts of superoxide anion (O₂⁻) and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [26] [28]. When uncontrolled, these ROS induce lipid peroxidation—the oxidative degradation of polyunsaturated fatty acids within the lipid bilayer. This process directly damages membrane structure, increasing fluidity and permeability, and can also initiate signaling cascades that lead to programmed cell death [27] [28]. The collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential due to ROS further impairs ATP synthesis, leading to bioenergetic failure and exacerbating cellular stress [26].

Programmed Cell Death Pathways

The activation of specific programmed cell death (PCD) pathways is a major consequence of membrane-associated stress.

- Pyroptosis: This inflammatory form of PCD is triggered by intracellular lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which activates inflammatory caspases (caspase-4/5 in humans, caspase-11 in mice) [29]. This activation leads to the cleavage of gasdermin D (GSDMD). The N-terminal fragments of GSDMD oligomerize and form large, non-selective pores in the plasma membrane, resulting in cytolysis and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [29]. Endothelial GSDMD has been identified as a critical mediator of vascular injury and lethality in response to LPS [30].

- Ferroptosis: This iron-dependent form of PCD is characterized by the overwhelming accumulation of lipid peroxides, driven by the failure of the glutathione-dependent antioxidant system [27] [28]. The loss of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) activity is a pivotal event, leading to the irreversible oxidation of membrane lipids and subsequent membrane rupture.

- Apoptosis: Often initiated by mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis involves the formation of pores in the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOMP), releasing cytochrome c and other pro-apoptotic factors [26] [28]. Although it typically preserves membrane integrity until the final stages, the apoptotic cascade contributes to overall cellular demise and barrier dysfunction.

The concept of PANoptosis has emerged to describe the interplay and simultaneous activation of these PCD pathways, creating a complex cell death cascade that is particularly damaging in conditions like sepsis [28].

Direct Detergent Effects and Micelle Disruption

In hydrolysate and biophysical research, membrane integrity can be directly compromised by detergent-like molecules. Detergents are used to solubilize membrane proteins by forming mixed micelles with membrane lipids, effectively dissolving the lipid bilayer [31]. The critical micelle concentration (CMC) is a key parameter, representing the detergent concentration at which micelle formation and membrane solubilization begin. Maintaining detergent concentrations above the CMC is crucial for preserving the stability of extracted membrane protein complexes, while improper handling can lead to protein aggregation or complex dissociation [31]. This principle is directly applicable when evaluating the inherent toxicity of hydrolysates containing surfactant compounds.

Experimental Assessment of Membrane Integrity

A multi-faceted approach is required to experimentally evaluate membrane compromise. The following table summarizes key quantitative parameters and their assessment methods.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Assessing Membrane Integrity and Permeability

| Parameter | Assay/Method | Key Readout | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability & Cytolysis | Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release | % LDH released vs. total | Measures integrity of plasma membrane; high release indicates necrosis/lysis [28]. |

| Lipid Peroxidation | Malondialdehyde (MDA) assay; BODIPY 581/591 C11 probe | MDA concentration; fluorescence shift | MDA is a byproduct of lipid peroxidation; C11 probe oxidation shifts fluorescence from red to green [27]. |

| Ion Flux | Intracellular Ca²⁺ imaging (e.g., Fluo-4 AM) | Fluorescence intensity over time | Unregulated Ca²⁺ influx is a hallmark of membrane compromise and a trigger for downstream signaling [28]. |

| Membrane Permeability | Propidium Iodide (PI) or SYTOX Green uptake | Fluorescence intensity | These dyes are excluded by intact membranes; fluorescence increases upon binding to nucleic acids in compromised cells. |

| Trans-Endothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) | EVOM voltohmmeter or equivalent | Resistance (Ω × cm²) | Gold standard for real-time, label-free monitoring of endothelial and epithelial barrier integrity [29]. |

Detailed Protocol: Assessing LPS-Induced Endothelial Barrier Dysfunction

This protocol outlines the steps to model and measure toxin-induced permeability changes in an endothelial cell monolayer, a system directly relevant to studying sepsis and hydrolysate toxicity.

Objective: To quantify the disruption of endothelial barrier integrity by bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) using Trans-Endothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) and fluorescent dye leakage.

Materials:

- Cell Line: Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs).

- Culture Reagents: Endothelial Cell Growth Medium, trypsin-EDTA, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Assay Equipment: Transwell permeable supports (e.g., 0.4 µm pore size), EVOM voltohmmeter, fluorescence plate reader.

- Treatments: Ultrapure LPS from E. coli O111:B4, prepared as a stock solution in sterile water.

- Tracer Dye: Fluorescein isothiocyanate–dextran (FITC-dextran, 70 kDa).

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed HUVECs at a density of 1 × 10⁵ cells per well onto collagen-coated Transwell inserts. Culture for 3-5 days, replacing the medium every 2 days, until a stable, confluent monolayer is formed (typically indicated by a stable TEER value > 50 Ω × cm²).

- Baseline Measurement: Measure the TEER of each well using the EVOM voltohmmeter. Record these values as the baseline resistance.

- Treatment: Add LPS to the culture medium at a final concentration of 100 ng/mL. Include vehicle-only control wells.

- Kinetic TEER Monitoring: Measure and record TEER values at regular intervals post-treatment (e.g., 3, 6, 12, 24 hours). Express the data as a percentage of the baseline measurement for each well.

- Paracellular Permeability Assay: At the 24-hour endpoint, add FITC-dextran (0.5-1 mg/mL) to the upper chamber of the Transwell. Incubate for 1 hour at 37°C.

- Sample Collection: Collect 100 µL of medium from the lower chamber.

- Quantification: Measure the fluorescence of the samples from the lower chamber using a fluorescence plate reader (excitation ~490 nm, emission ~520 nm). The fluorescence intensity is directly proportional to the permeability of the endothelial monolayer.

Data Analysis: Statistical analysis (e.g., Student's t-test or ANOVA) should be performed to compare the TEER values and FITC-dextran flux of LPS-treated groups against the vehicle control group. A significant decrease in TEER and a significant increase in fluorescence in the lower chamber indicate compromised barrier integrity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying Membrane Integrity

| Reagent/Category | Example Compounds | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Toxins & Inducers | Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | A primary PAMP used to model gram-negative bacterial infection, inducing TLR4 signaling, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction [29]. |

| PCD Inhibitors | Necrostatin-1 (necroptosis), Ferrostatin-1 (ferroptosis), Z-VAD-FMK (apoptosis), Disulfiram (pyroptosis) | Pharmacological tools to inhibit specific programmed cell death pathways, allowing for mechanistic dissection of their individual contributions to toxicity [28]. |

| ROS Scavengers & Antioxidants | N-acetylcysteine (NAC), Vitamin C, Melatonin | Compounds that directly neutralize ROS or bolster endogenous antioxidant defenses, used to probe the role of oxidative stress [26] [27]. |

| Membrane Solubilization Detergents | n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltopyranoside (DDM), n-Octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (OG) | Non-ionic detergents used to solubilize membrane proteins while preserving protein-protein interactions for structural and biochemical studies like native mass spectrometry [31]. |

| Ion Chelators | Deferoxamine (DFO) | An iron chelator that inhibits iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, used to confirm and inhibit ferroptosis [27] [28]. |

Signaling Pathways in Membrane Integrity Loss

The following diagrams illustrate the key signaling pathways that converge on membrane disruption, as described in the literature on sepsis and endotoxin injury.

LPS-Induced Endothelial Activation and Pyroptosis

Oxidative Stress and Programmed Cell Death Crosstalk

The compromise of cellular membrane integrity is a convergent point for multiple toxicity pathways, from direct detergent-like effects to complex cellular signaling initiated by pathogen-associated molecules. The experimental frameworks and mechanistic insights derived from sepsis research, particularly those involving LPS-induced endothelial dysfunction, provide a robust and translatable model for the hydrolysates field. A systematic approach that integrates assessments of oxidative stress, activation of specific PCD pathways, and functional measurements of permeability is essential for deconvoluting shared toxicity mechanisms and identifying potential intervention strategies.

Inflammatory Response Mediation via NF-κB and MAPK Pathways

The inflammatory response is a complex biological process mediated through sophisticated intracellular signaling networks. Among these, the Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathways represent two crucial signaling cascades that regulate the production of pro-inflammatory mediators. These pathways function as central coordinators of immune responses, activating upon recognition of diverse stimuli including pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and cytokines [32] [33]. The NF-κB pathway, discovered nearly four decades ago, was initially identified as a pivotal regulator of inflammatory responses but has since been expanded to involve various signaling mechanisms, biological processes, and human diseases [32]. Similarly, MAPK pathways integrate multiple extracellular signals to determine cellular outcomes in inflammation. Understanding the intricate interplay between these pathways provides critical insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies for inflammatory diseases, including those relevant to hydrolysates research where unidentified components may trigger shared toxicity mechanisms through these conserved inflammatory cascades.

Molecular Mechanisms of NF-κB Pathway Activation

Canonical NF-κB Signaling

The mammalian NF-κB transcription factor family comprises five members: NF-κB1 (p105/p50), NF-κB2 (p100/p52), p65 (RELA), RELB, and c-REL [32]. These proteins share a conserved Rel homology domain (RHD) that facilitates formation of homo- or heterodimers, with the p65/p50 heterodimer being the most prevalent form [32] [33]. In resting cells, NF-κB dimers remain sequestered in the cytoplasm through interaction with inhibitory IκB proteins [32].

The canonical NF-κB pathway activates in response to numerous stimuli including bacterial and viral products, cytokines, and reactive oxygen species [32]. The key activation mechanism involves the I-kappaB kinase (IKK) complex, consisting of catalytic subunits IKKα and IKKβ and regulatory subunit NEMO (IKKγ) [32] [33]. Upon pathway activation, IKKβ phosphorylates IκB proteins, leading to their K48-linked ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation [33]. This process liberates NF-κB dimers (primarily p65/p50), allowing their translocation to the nucleus where they bind κB sites in promoter/enhancer regions to activate transcription of pro-inflammatory genes including cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), chemokines, and adhesion molecules [32] [33].

Non-Canonical NF-κB Signaling

The non-canonical NF-κB pathway activates through a more limited set of receptors, primarily members of the TNF receptor superfamily [33]. This pathway centers on NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK), which typically remains at low levels in steady-state conditions due to TRAF3-dependent ubiquitination and degradation [33]. Upon receptor engagement, TRAF3 degradation permits NIK accumulation, leading to IKKα phosphorylation and activation [33]. Activated IKKα then phosphorylates p100, prompting its processing to p52 and subsequent nuclear translocation of RelB/p52 dimers [33]. The non-canonical pathway exhibits slower but more persistent activation kinetics compared to the canonical pathway, aligning with its functions in immune cell development, lymphoid organogenesis, and immune homeostasis [33].

Molecular Mechanisms of MAPK Pathway Activation

The MAPK pathways comprise three major signaling cascades: extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 MAPK [34] [35]. These pathways transduce signals from cell surface receptors to intracellular targets, regulating diverse cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, stress responses, and inflammation [34].

Each MAPK pathway follows a similar three-tiered kinase architecture consisting of MAPK kinase kinases (MAP3Ks), MAPK kinases (MAP2Ks), and MAPKs [34]. The p38 MAPK pathway particularly serves as a crucial mediator of inflammatory responses, activating in response to cellular stresses and inflammatory cytokines [36] [35]. Upon activation, phosphorylated p38 MAPK translocates to the nucleus where it phosphorylates transcription factors such as ATF-2, leading to increased expression of pro-inflammatory genes [36].

MAPK signaling demonstrates significant complexity, with cross-talk occurring between different MAPK pathways and with other signaling cascades including NF-κB [34]. This interconnectivity enables fine-tuned cellular responses to diverse stimuli, with specific outcomes determined by signal intensity, duration, and cellular context.

Pathway Interplay and Crosstalk Mechanisms

NF-κB and MAPK pathways engage in extensive crosstalk, creating a sophisticated regulatory network that determines the ultimate inflammatory response. Multiple interaction points exist between these pathways, enabling mutual regulation and signal integration.

Research demonstrates that NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK), a central component of non-canonical NF-κB signaling, can activate MAPK pathways in certain contexts. In melanoma cells, NIK overexpression increases phosphorylation of ERK1/2, while dominant-negative ERK constructs suppress NF-κB promoter activity [37]. This NIK-MAPK signaling pathway represents a novel mechanism for regulating NF-κB activity in specific cell types [37].

Similarly, studies on flagellin fusion proteins reveal coordinated involvement of both NF-κB and MAPK signaling in dendritic cell cytokine production. Inhibition of MAPK signaling dose-dependently suppresses both pro-inflammatory (IL-6, TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines induced by flagellin fusion proteins [34]. Meanwhile, NF-κB signaling specifically regulates IL-12 production, demonstrating how different aspects of immune responses can be partitioned between these pathways [34].

The p38 MAPK/NF-κB axis represents another significant point of integration. In burned rats, debridement-induced reductions in systemic inflammation correlated with decreased phosphorylation of both p38 MAPK and NF-κB [36]. This coordinated downregulation suggests therapeutic interventions can simultaneously target both pathways to modulate inflammatory responses.

Table 1: Experimental Evidence of NF-κB/MAPK Crosstalk in Different Model Systems

| Experimental Model | Stimulus/Intervention | Observed Pathway Interaction | Biological Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma cells | NIK overexpression | NIK activates ERK1/2; ERK inhibition reduces NF-κB activity | Enhanced constitutive NF-κB activation and CXCL1 expression | [37] |

| Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells | Flagellin-allergen fusion protein (rFlaA:Betv1) | MAPK inhibition suppresses IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10; NF-κB inhibition blocks IL-12 | Coordinated regulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production | [34] |

| Burned rats | Debridement during shock period | Concurrent reduction in p38 MAPK and NF-κB phosphorylation | Accelerated decline of systemic inflammatory response | [36] |

| RAW 264.7 macrophages | LPS stimulation + phenethylferulate treatment | Compound inhibits both NF-κB and MAPK (ERK, JNK, p38) activation | Synergistic suppression of inflammatory mediators (PGE2, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) | [35] |

Quantitative Assessment of Pathway Activation

Measuring the activation status of NF-κB and MAPK pathways provides crucial information for evaluating inflammatory responses in hydrolysates research. The following parameters represent key quantitative indicators of pathway activity:

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for Assessing NF-κB and MAPK Pathway Activation

| Parameter Category | Specific Measurements | Experimental Methods | Significance in Pathway Activation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylation Status | Phospho-IκBα, phospho-p65, phospho-IKKα/β (NF-κB); phospho-ERK1/2, phospho-JNK, phospho-p38 (MAPK) | Western blot, phospho-specific ELISA, multiplex immunoassays | Indicates immediate upstream kinase activity and pathway initiation |

| Nuclear Translocation | p65 nuclear accumulation (NF-κB); phospho-MAPK nuclear localization | Immunofluorescence, cellular fractionation + Western blot, image-based cytometry | Demonstrates functional transcription factor activation |

| Downstream Cytokine Production | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8/CXCL1 | ELISA, multiplex cytokine arrays, mRNA quantification by RT-qPCR | Reflects functional transcriptional output of pathway activation |

| Enzyme Activity | IKK kinase activity, MAPK kinase assays | In vitro kinase assays with specific substrates | Provides direct measurement of catalytic function |

| Gene Expression | iNOS, COX-2, cytokine mRNA levels | RT-qPCR, RNA-seq, Northern blot | Indicates transcriptional targets of activated pathways |

Experimental data from various models illustrates how these parameters change upon pathway activation. In LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages, phenethylferulate (PF) treatment significantly inhibited phosphorylation of IκBα (82% reduction), ERK (75% reduction), JNK (68% reduction), and p38 (71% reduction) at 12μM concentration compared to LPS-only controls [35]. This correlated with reduced nuclear translocation of p65 and decreased production of inflammatory mediators including PGE2 (84% inhibition), TNF-α (79% inhibition), IL-1β (72% inhibition), and IL-6 (81% inhibition) [35].

In burned rats, debridement intervention significantly decreased phosphorylated p38MAPK and NF-κB levels in liver tissue (P < 0.05 to P < 0.01 compared to controls), which corresponded with reduced systemic levels of inflammatory factors including IL-6, TNF-α, and HMGB1 [36]. These quantitative measurements provide robust assessment of pathway modulation by therapeutic interventions.

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Analysis

Macrophage-based Inflammation Model

Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Maintain RAW 264.7 murine macrophages in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 units/mL penicillin, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO₂ [35].

- Seed cells at appropriate densities (5×10³ cells/well for MTT assay in 96-well plates; 3×10⁵ cells/well for cytokine measurement in 24-well plates; 1×10⁶ cells/well for Western blot analysis in 6-well plates) and allow to adhere overnight [35].

- Pre-treat cells with test compounds (e.g., hydrolysates fractions) for 1 hour before stimulating with LPS (1 μg/mL) for specified durations (typically 6-24 hours depending on readout) [35].

Viability Assessment:

- Perform MTT assay by adding 0.2 mg/mL MTT solution to cells and incubating for 4 hours [35].

- Remove medium and dissolve formed formazan crystals in DMSO [35].

- Measure absorbance at 570 nm using a microplate reader [35].

- Ensure test compounds do not reduce cell viability below 90% of untreated controls to exclude cytotoxicity-confounded results [35].

Protein Extraction and Western Blot:

- Lyse cells in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors [35].

- Determine protein concentration using BCA assay [35].

- Separate 30 μg total protein per sample by 10% SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membranes [35].

- Block membranes with 5% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature [35].

- Incubate with primary antibodies against target proteins (e.g., p-IκBα, p-p65, p-ERK, p-JNK, p-p38, iNOS, COX-2) overnight at 4°C [35].

- Incubate with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature [35].

- Detect signals using enhanced chemiluminescence substrate and quantify band intensities with ImageJ software [35].

- For nuclear translocation studies, perform cellular fractionation using nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents before Western blot analysis [35].

Cytokine Measurement:

- Collect culture supernatants after treatment by centrifugation at 1000×g for 10 minutes [35].

- Analyze levels of PGE2, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 using commercial ELISA kits according to manufacturer's protocols [35].

Pathway Inhibition Studies

Pharmacological Inhibition:

- Pre-treat cells with specific inhibitors 1 hour prior to stimulus: BMS-345541 or TPCA-1 (NF-κB inhibitors), U0126 (ERK inhibitor), SP600125 (JNK inhibitor), SB202190 (p38 inhibitor), or rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor) [34] [35].

- Use concentration ranges established in literature (typically 1-20 μM for most kinase inhibitors) and include DMSO vehicle controls [34].

- Assess pathway specificity by examining both targeted and non-targeted pathways to identify off-target effects.

Genetic Approaches:

- Utilize siRNA or CRISPR/Cas9 to knock down specific pathway components (IKK subunits, MAPKs, or adaptor proteins) [37].

- Confirm knockdown efficiency by Western blot 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Include appropriate negative controls (scrambled siRNA, non-targeting gRNA).

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NF-κB and MAPK Pathway Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Activators | LPS (TLR4 agonist), Flagellin (TLR5 agonist), TNF-α, IL-1β | Positive control stimuli for pathway induction | Validating experimental systems; establishing maximum response levels |

| NF-κB Inhibitors | BMS-345541 (IKK inhibitor), TPCA-1 (IKK-2 inhibitor), BAY-11-7082 (IκB phosphorylation inhibitor) | Pharmacological blockade of specific NF-κB pathway steps | Mechanism determination; pathway dissection |

| MAPK Inhibitors | U0126 (MEK1/2 inhibitor), SP600125 (JNK inhibitor), SB202190 (p38 inhibitor) | Selective inhibition of MAPK pathway branches | Evaluating contribution of specific MAPKs to inflammatory responses |

| Antibody Panels | Phospho-specific antibodies (p-IκBα, p-p65, p-ERK, p-JNK, p-p38), Total protein antibodies, Nuclear markers (Lamin-B1) | Detection of pathway activation and protein localization | Western blot, immunofluorescence, cellular fractionation studies |

| Cytokine Assays | ELISA kits for TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, PGE2; Multiplex bead arrays | Quantification of inflammatory mediators | Functional output measurement of pathway activation |

| Cell Lines | RAW 264.7 (murine macrophages), THP-1 (human monocytes), HEK-Blue TLR cells | Inflammatory model systems | Screening hydrolysates for immunomodulatory activity |

Pathway Visualization

NF-κB and MAPK Signaling Pathway Interplay

The diagram illustrates the coordinated activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways by common inflammatory stimuli and their convergence on inflammatory gene transcription. Critical crosstalk points (dashed lines) enable mutual regulation between these pathways, creating an integrated signaling network that determines the magnitude and duration of inflammatory responses.

The NF-κB and MAPK pathways represent central signaling axes that mediate inflammatory responses through complex individual mechanisms and sophisticated crosstalk. Their coordinated activation regulates the production of key inflammatory mediators including cytokines, chemokines, and enzymes. The experimental approaches and research tools outlined provide comprehensive methodologies for investigating these pathways in hydrolysates research, enabling identification of potential shared toxicity mechanisms. Quantitative assessment of pathway activation through phosphorylation status, nuclear translocation, and cytokine production offers robust evaluation of inflammatory potential, while pharmacological and genetic manipulation approaches allow mechanistic dissection of specific pathway contributions. Understanding these inflammatory cascades at molecular level provides critical insights for safety assessment and therapeutic intervention strategies in hydrolysates-related research and development.

Advanced Analytical Approaches: Proteomic, Metabolomic and in silico Strategies for Toxicity Mechanism Identification

Integrated Proteomic and Metabolomic Analysis for Metabolic Reprogramming Assessment

Integrated proteomic and metabolomic analysis represents a powerful multi-omics approach that provides a comprehensive view of cellular phenotypic states by simultaneously characterizing the proteome and metabolome of a biological system. This dual analysis enables researchers to uncover the molecular mechanisms underlying physiological and pathological processes, particularly metabolic reprogramming—a fundamental hallmark of various disease states and toxicological responses. The synergy between proteomics and metabolomics data offers unique insights into how protein expression changes drive alterations in metabolic pathways and, conversely, how metabolic shifts influence protein activity and signaling networks.

Within the context of hydrolysates research, this integrated approach is particularly valuable for identifying shared toxicity mechanisms. As the field moves toward sustainable alternatives in various industries, including aquaculture and pharmaceuticals, understanding the molecular-level effects of protein hydrolysates becomes paramount. Integrated proteomics and metabolomics can systematically identify both beneficial adaptations and adverse outcomes by revealing pathway-level perturbations that might remain obscured in single-omics studies. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for implementing this methodology specifically for metabolic reprogramming assessment in hydrolysates toxicity research, offering detailed protocols, data integration strategies, and visualization techniques tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations and Significance

Fundamental Principles

Integrated proteomic and metabolomic analysis operates on the principle that proteins and metabolites represent complementary functional layers of cellular activity. While proteomics captures the expressed effector molecules that catalyze biochemical reactions and regulate cellular processes, metabolomics provides a snapshot of the ultimate biochemical outputs resulting from these activities. This relationship creates a powerful feedback loop for interpretation: proteomic data can explain mechanistic drivers of observed metabolic changes, while metabolomic data can reveal the functional consequences of altered protein expression patterns.

The assessment of metabolic reprogramming—the strategic alteration of cellular metabolism in response to external stimuli—requires this dual perspective. Cells undergoing metabolic reprogramming typically exhibit coordinated changes across multiple pathways, including central carbon metabolism, amino acid metabolism, nucleotide biosynthesis, and energy homeostasis. Through integrated analysis, researchers can determine whether these metabolic shifts result from changes in enzyme abundance (detected via proteomics), post-translational modifications, or allosteric regulation (inferred from metabolite-protein relationships), thereby providing a more nuanced understanding of the regulatory hierarchy governing the metabolic adaptation.

Applications in Hydrolysates Research

In hydrolysates research, integrated proteomics and metabolomics has emerged as an essential tool for characterizing the complex biological effects of protein hydrolysates. This approach has proven particularly valuable in distinguishing between adaptive responses and genuinely toxic mechanisms. For instance, a study investigating soy protein hydrolysates in turbot revealed that hydrolysate supplementation restored fishmeal-equivalent growth through enhanced ribosomal biogenesis and mTOR signaling, while the non-hydrolyzed soy protein concentrate impaired energy metabolism through folate cycle disruption and endoplasmic reticulum proteostatic stress [38]. Without integrated multi-omics analysis, these contrasting mechanisms would have been difficult to disentangle.

The approach similarly illuminates toxicity pathways in other contexts. Research on 6PPD and its quinone derivative utilized network toxicology combined with molecular docking to identify specific and shared protein targets related to respiratory toxicity, including disruptions in mitochondrial electron transport chain, apoptotic pathway dysregulation, and activation of NF-κB/JAK-STAT inflammatory cascades [39]. Another study on methylglyoxal-induced neurotoxicity in human neuroblastoma cells employed integrated proteomics and metabolomics to reveal significant alterations in protein synthesis, cellular structural integrity, mitochondrial function, oxidative stress responses, and key metabolic pathways including arginine biosynthesis, glutathione metabolism, and the tricarboxylic acid cycle [40]. These examples demonstrate how integrated analysis provides mechanistic clarity for both efficacy and safety assessment of hydrolysates.

Methodological Framework

Experimental Design Considerations

Robust experimental design forms the foundation for successful integrated proteomics and metabolomics studies. For metabolic reprogramming assessment in hydrolysates research, several key considerations must be addressed:

Temporal Design: The timing of sample collection should capture both acute and chronic responses to hydrolysate exposure. For short-term studies, multiple time points (e.g., 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours) enable tracking of the progression of metabolic adaptations. For longer-term studies, such as the 56-day feeding trial in turbot [38], endpoint analyses should be complemented with intermediate sampling where feasible.

Dose-Response Relationships: Including multiple concentration levels allows for distinguishing adaptive from toxic responses. Studies should incorporate at least three treatment concentrations alongside appropriate controls, as demonstrated in the methylglyoxal neurotoxicity study which used 500, 750, and 1000 μM exposures to establish concentration-dependent effects [40].

Replication and Power: Adequate biological replication is essential for statistical rigor in omics studies. For animal or cell culture models, a minimum of 5-6 biological replicates per group provides sufficient power for detecting meaningful changes, as evidenced in the cardiac resynchronization therapy study using 5-6 dogs per experimental group [41] and the turbot study with appropriate statistical power [38].

Control Groups: Proper controls must be included to account for baseline biological variation. These typically include vehicle controls (for in vitro studies), placebo/formulation controls (for in vivo studies), and positive controls when assessing specific toxicity endpoints.

Sample Preparation Protocols

Standardized sample preparation is critical for generating high-quality proteomics and metabolomics data. The following protocols have been successfully employed in integrated multi-omics studies and can be adapted for hydrolysates research.

Tissue Sample Preparation

For tissue analyses, such as in the assessment of cardiac fibrosis mechanisms [41] or hepatic metabolic reprogramming in turbot [38], the following protocol is recommended:

Tissue Collection and Homogenization: Rapidly excise tissue samples and immediately flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen. For homogenization, pre-cool a mortar and pestle with liquid nitrogen and grind tissue to a fine powder. Transfer approximately 30 mg of powdered tissue to a pre-chilled microtube.

Dual Extraction for Proteomics and Metabolomics: Add 500 μL of cold methanol:water (4:1, v/v) containing internal standards for metabolomics to the powdered tissue. Homogenize using a pre-cooled rotor-stator homogenizer for 30 seconds at 4°C. Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

Metabolite Separation: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and evaporate under nitrogen stream. Reconstitute the metabolite fraction in 100 μL of methanol:water (1:1, v/v) for LC-MS analysis.

Protein Precipitation and Digestion: To the remaining pellet, add 500 μL of lysis buffer (8 M urea, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) and vortex vigorously. Sonicate for 30 seconds on ice, then centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and determine protein concentration using BCA assay. Reduce proteins with 5 mM dithiothreitol (56°C, 30 minutes), alkylate with 10 mM iodoacetamide (room temperature, 30 minutes in darkness), and digest with trypsin (1:50 enzyme-to-protein ratio, 37°C, overnight).

Peptide Desalting: Desalt digested peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction cartridges according to manufacturer's instructions. Elute peptides with 60% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid, dry under vacuum, and reconstitute in 0.1% formic acid for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Cell Culture Sample Preparation

For in vitro models, such as the SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line used in methylglyoxal neurotoxicity research [40], the following protocol is appropriate:

Cell Culture and Treatment: Culture cells in appropriate medium under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂). At approximately 80% confluence, treat with hydrolysates at predetermined concentrations. Include vehicle controls and positive controls if applicable.