SAR Matrix Analysis: From Ligand-Target Predictions to Accelerated Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) matrix analysis for ligand-target prediction, a critical computational approach in modern drug discovery.

SAR Matrix Analysis: From Ligand-Target Predictions to Accelerated Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) matrix analysis for ligand-target prediction, a critical computational approach in modern drug discovery. It covers foundational concepts of polypharmacology and SAR transfer, explores diverse methodological frameworks including ligand-centric, target-centric, and advanced deep learning models like DeepSARM for dual-target design. The content details common optimization challenges and solutions, alongside rigorous validation protocols and performance benchmarking of state-of-the-art tools such as MolTarPred, RF-QSAR, and proteochemometric modeling. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current computational strategies to efficiently identify drug targets, repurpose existing therapeutics, and design novel polypharmacological agents.

Understanding SAR Matrices: The Bedrock of Modern Drug Discovery

Defining SAR Matrices and Ligand-Target Interactions

Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) are foundational to modern drug discovery, providing a systematic framework for understanding how the chemical structure of a molecule influences its biological activity against a specific target [1]. At its core, SAR analysis is based on the principle that similar compounds tend to exhibit similar biological effects, a concept often referred to as the principle of similarity [2]. The primary objective of SAR studies is to rationally explore chemical space—which is essentially infinite in the absence of guiding principles—to identify structural modifications that optimize molecular properties such as potency, selectivity, and bioavailability [1].

A ligand-target interaction describes the molecular recognition between a drug-like molecule (the ligand) and its biological target, typically a protein. These interactions are local events determined by the physical-chemical properties of the target's binding site and the complementary substructures of the ligand [3]. Cell proliferation, differentiation, gene expression, metabolism, and signal transduction all require the participation of ligands and targets, making their interaction a fundamental biological process worthy of detailed investigation [3].

The SAR matrix provides a structured format for organizing and analyzing SAR data, typically consisting of chemical structures and their corresponding biological activities. This matrix serves as the analytical backbone for understanding how systematic structural variations translate into changes in biological activity, forming the basis for rational drug design [4].

Computational Approaches for SAR Matrix Analysis

Ligand-Based and Target-Based Methods

Computational methods for analyzing SAR matrices and predicting ligand-target interactions can be broadly categorized into ligand-based and target-based approaches, with recent hybrid methods combining elements of both [5] [3].

Ligand-based methods operate on the principle of similarity, where candidate ligands are compared with known active compounds for a given target. These approaches include similarity searching, pharmacophore modeling, and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models [5] [3]. The 3D-QSAR methods like Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) align ligands capable of binding to a given target and measure field intensities around the aligned molecules, then regress these intensities with activity values to create predictive models [3].

Target-based methods utilize structural information about the biological target to predict interactions. Molecular docking is a prominent target-based approach that predicts the preferred orientation of a ligand when bound to a target protein through conformation searching and energy minimization [6] [3]. Other target-based methods compare target similarities using sequences, EC numbers, domains, or 3D structures [3].

Hybrid methods that consider both target and ligand information have proven particularly promising. For example, the Fragment Interaction Model (FIM) describes interactions between ligand substructures and binding site fragments, generating an interaction matrix that can predict unknown ligand-target relationships while providing binding details [3].

Key Methodological Considerations

When employing these computational approaches, several critical factors must be addressed to ensure reliable results:

Domain of Applicability: All QSAR models have a defined scope beyond which predictions become unreliable. The domain of applicability can be determined by assessing the similarity of new molecules to the training set, using approaches such as similarity to the nearest neighbor or the number of neighbors within a defined similarity cutoff [1].

Model Interpretability: For SAR exploration, models must be interpretable to provide insights into how specific structural features influence observed activity. Linear regression and random forests are examples of interpretable models, while more complex "black box" models may require specialized visualization techniques [1] [7].

Activity Landscapes and Cliffs: The activity landscape concept views SAR data as a topographic map where structural similarity forms the x-y plane and activity represents the z-axis. Smooth regions indicate gradual activity changes with structural modifications, while activity cliffs represent sharp changes in activity resulting from small structural modifications, highlighting key structural determinants [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Approaches for SAR Analysis

| Method Type | Key Features | Common Algorithms/Tools | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-Based | Relies on compound similarity; used when target structure is unknown | 2D/3D similarity, QSAR, Pharmacophore modeling | Virtual screening, lead optimization, toxicity prediction |

| Target-Based | Utilizes target structure information; requires 3D protein structure | Molecular docking, Molecular dynamics | Binding mode prediction, structure-based design |

| Hybrid Methods | Integrates both ligand and target information | Fragment Interaction Model (FIM), BLM-NII | Comprehensive interaction analysis, novel target prediction |

Experimental Protocols for SAR Matrix Construction

Data Curation and Preparation

The foundation of any robust SAR analysis is high-quality, well-curated data. The following protocol outlines key steps for preparing SAR data:

Data Source Identification: Extract bioactivity data from curated databases such as ChEMBL, BindingDB, or PubChem. ChEMBL is particularly valuable for its extensive, experimentally validated bioactivity data, including drug-target interactions, inhibitory concentrations, and binding affinities [5].

Data Filtering: Apply confidence filters to ensure data quality. For example, in ChEMBL, use a minimum confidence score of 7 (indicating direct protein complex subunits assigned) to include only well-validated interactions [5].

Redundancy Removal: Eliminate duplicate compound-target pairs, retaining only unique interactions to prevent bias in the analysis [5].

Activity Data Standardization: Convert all activity measurements (IC₅₀, Ki, EC₅₀) to consistent units (typically nM) and apply appropriate thresholds (e.g., <10,000 nM) to focus on relevant interactions [5].

Structural Standardization: Generate canonical representations of chemical structures (e.g., canonical SMILES) and compute molecular descriptors or fingerprints for subsequent analysis [5].

SAR Expansion and Exploration

Once a preliminary dataset is established, systematic SAR exploration can proceed through the following methodology:

Scaffold Pruning: Iteratively remove functional group substitutions from the core scaffold of initial hit compounds to identify the basic structural requirements for activity (pharmacophore identification) [4].

SAR Expansion: Identify commercially available compounds possessing the hit scaffold with varying functional group substitutions using chemical database search tools (e.g., CAS SciFinder, ChEMBL) [4].

Compound Validation: Rigorously assess commercially acquired compounds for purity and identity using established methods (LC-MS and NMR) before biological testing [4].

Rational Analog Selection: Follow systematic approaches such as the Topliss scheme for analog selection, which provides a decision tree for choosing substituents based on their electronic and hydrophobic properties [4].

QSAR Model Development: When sufficient compounds are available, develop preliminary QSAR models to quantitatively correlate structural features with biological activity, informing the hit advancement process [4].

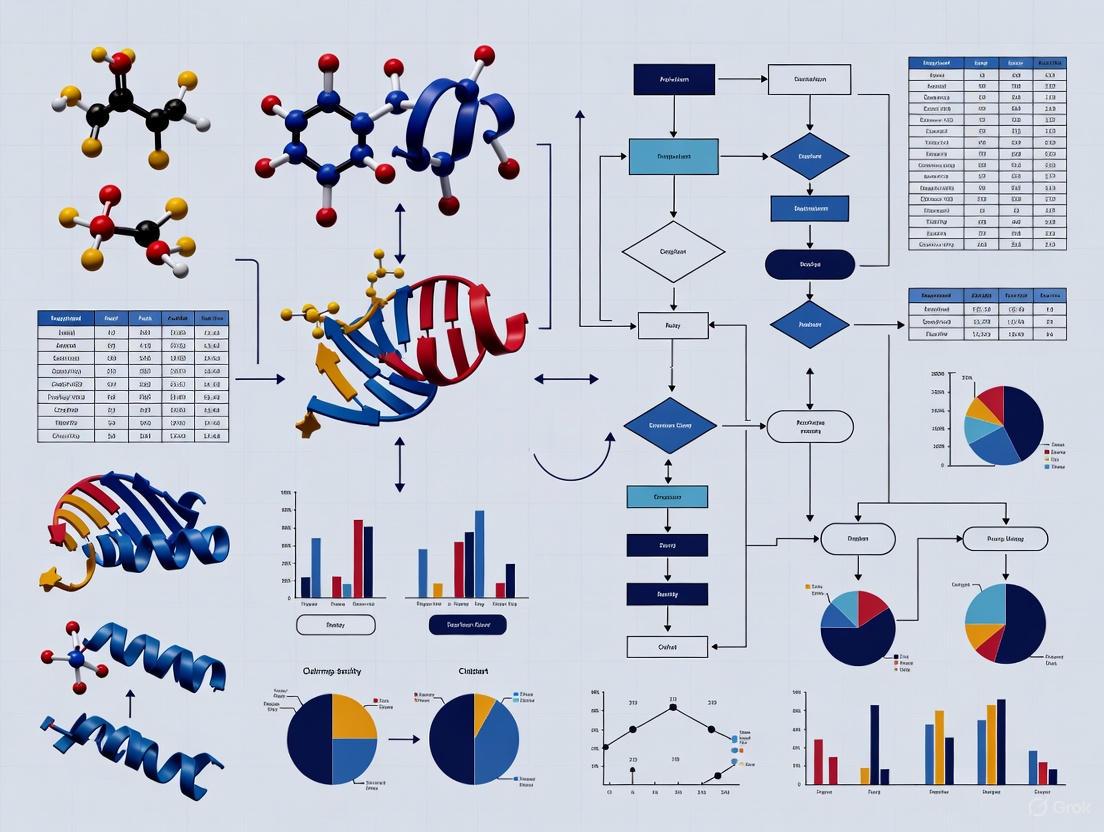

Diagram 1: SAR Matrix Construction and Analysis Workflow. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of building and analyzing SAR matrices, from initial data collection through lead optimization.

Advanced Analytical Frameworks

Fragment Interaction Model (FIM)

The Fragment Interaction Model (FIM) provides an advanced framework for understanding the structural basis of ligand-target interactions at the atomic level. This approach is based on the premise that target-ligand interactions are local events determined by interactions between specific substructures [3].

The FIM methodology proceeds through these key steps:

Complex Data Extraction: Obtain target-ligand complexes from structural databases such as the sc-PDB database, an annotated archive of druggable binding sites from the Protein Data Bank [3].

Binding Site Definition: Define binding sites as amino acid residues possessing at least one atom within 8Å around the ligand, capturing the immediate interaction environment [3].

Target Dictionary Creation:

- Represent each amino acid by its physical-chemical properties (e.g., residue volume, polarizability, solvation free energy)

- Reduce dimensionality using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to create 5-dimensional feature vectors

- Permutate and combine twenty amino acids into 4200 trimers

- Cluster trimers into 199 clusters based on chemical properties using hierarchical clustering (Ward's algorithm) [3]

Ligand Substructure Dictionary: Create a dictionary of chemical substructures from sources like PubChem fingerprints, removing single atoms and bonds to maintain appropriate structural granularity [3].

Interaction Matrix Generation: Build the FIM by generating an interaction matrix M representing the fragment interaction network, which can subsequently predict unknown ligand-target interactions and provide binding details [3].

Diagram 2: Fragment Interaction Model (FIM) Framework. This diagram outlines the process of building a Fragment Interaction Model, from structural data to predictive capability.

Visual Validation of SAR Models

Visual validation complements statistical validation by enabling graphical inspection of QSAR model results, helping researchers understand how endpoint information is employed by the model. The CheS-Mapper software implements this approach through:

Chemical Space Mapping: Compounds are embedded in 3D space based on chemical similarity, with each compound represented by its 3D structure [7].

Feature Space Analysis: Model predictions are compared to actual activity values in feature space, revealing whether endpoints are modeled too specifically or generically [7].

Activity Cliff Inspection: Researchers can visually identify activity cliffs—pairs of structurally similar compounds with large activity differences—which highlight critical structural determinants [7].

Model Refinement: Visual validation helps identify misclassified compounds, potentially revealing data quality issues, inappropriate feature selection, or model over/underfitting [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for SAR Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for SAR Matrix and Ligand-Target Interaction Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Resource | Function and Application in SAR Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL | Provides experimentally validated bioactivity data, drug-target interactions, and binding affinities for SAR modeling [5] |

| BindingDB | Curated database of protein-ligand interaction affinities, focusing primarily on drug targets [5] | |

| PubChem | Repository of chemical molecules and their activities against biological assays, including patent-extracted structures [4] [3] | |

| Structural Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, essential for structure-based methods [6] |

| sc-PDB | Annotated archive of druggable binding sites extracted from PDB, specifically focused on ligand-binding sites [3] | |

| Computational Tools | Molecular Docking Software (GOLD, AutoDock) | Predicts binding orientation and affinity of small molecules to protein targets using genetic algorithms [6] |

| CheS-Mapper | 3D viewer for visual validation of QSAR models, enabling exploration of small molecules in virtual 3D space [7] | |

| QsarDB Repository | Digital repository for archiving, sharing, and executing QSAR models in a standardized format [8] | |

| Target Prediction Methods | MolTarPred | Ligand-centric target prediction method based on 2D similarity searching against ChEMBL database [5] |

| RF-QSAR | Target-centric prediction using random forest QSAR models built from ChEMBL data [5] |

SAR matrices and ligand-target interaction analyses represent a sophisticated framework for understanding the molecular basis of drug action and optimizing therapeutic compounds. The integration of computational approaches—ranging from traditional QSAR to advanced fragment-based models—with experimental validation provides a powerful paradigm for modern drug discovery. As structural databases expand and computational methods evolve, particularly with the incorporation of machine learning and artificial intelligence, the precision and predictive power of these analyses will continue to improve. The resources and methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for advancing ligand-target SAR matrix analysis, ultimately contributing to more efficient and effective drug development.

The Critical Role of Polypharmacology in Drug Efficacy and Repurposing

For much of the past century, drug discovery was dominated by a "one target–one drug" paradigm, focused on developing highly selective ligands for individual disease proteins. While this strategy achieved some successes, it has major limitations, with approximately 90% of such candidates failing in late-stage trials due to lack of efficacy or unexpected toxicity [9]. These failures often stem from the reductionist oversight of the complex, redundant, and networked nature of human biology. In contrast, polypharmacology—the rational design of small molecules that act on multiple therapeutic targets—offers a transformative approach to overcome biological redundancy, network compensation, and drug resistance [9].

The clinical success of many "promiscuous" drugs that were later found to hit multiple targets has shifted the paradigm toward deliberately designing multi-target-directed ligands (MTDLs). This "magic shotgun" approach provides a holistic strategy to restore perturbed network homeostasis in complex diseases, particularly in areas where single-target therapies have consistently failed, such as oncology, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic diseases [9].

Scientific Rationale for Polypharmacology in Complex Diseases

Therapeutic Advantages of Multi-Target Engagement

Polypharmacology provides several distinct advantages over single-target approaches, particularly for complex diseases with multifactorial etiologies [9]:

- Synergistic Therapeutic Effects: Simultaneously modulating several key disease pathways can yield synergistic effects greater than single-target approaches.

- Mitigation of Drug Resistance: Pathogens and cancer cells frequently develop resistance to highly specific drugs through mutations. A drug inhibiting several unrelated targets substantially lowers the probability that a single genetic change confers full resistance.

- Reduced Adverse Effects: By distributing pharmacological activity across multiple pathways, multi-target agents can produce the desired therapeutic outcome without excessively pushing any single target to the point of toxicity.

- Improved Patient Compliance: A single polypharmacological agent simplifies treatment regimens compared to combination therapies, improving adherence particularly in elderly populations.

Disease Applications of Polypharmacology

Oncology

Cancer is a polygenic disease that activates multiple redundant signaling pathways. Multi-kinase inhibitors such as sorafenib and sunitinib suppress tumor growth and delay resistance by blocking multiple pathways simultaneously. Polypharmacology is especially advantageous in cancers driven by intricate networks (e.g., PI3K/Akt/mTOR), as multi-target agents can induce synthetic lethality and prevent compensatory mechanisms [9].

Neurodegenerative Disorders

Diseases like Alzheimer's (AD) and Parkinson's (PD) involve complex pathological processes including β-amyloid accumulation, tau hyperphosphorylation, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and neurotransmitter deficits. Multi-target-directed ligands (MTDLs) integrate activities like cholinesterase inhibition with anti-amyloid or antioxidant effects within one molecule. For example, the MTDL "memoquin" was designed to inhibit acetylcholinesterase while combating β-amyloid aggregation and oxidative damage [9].

Metabolic and Infectious Diseases

In metabolic syndrome, drugs that simultaneously address glycemic control, weight loss, and cardiovascular risk provide superior outcomes. The dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist tirzepatide has shown superior glucose-lowering and weight reduction compared to single-target drugs [9]. For infectious diseases, antibiotic hybrids—single molecules that attack multiple bacterial targets—reduce resistance risk since bacteria would need simultaneous mutations in different pathways to survive [9].

Computational Framework for Polypharmacology

Ligand-Target SAR Matrix Analysis

The prediction of drug-target interactions is fundamental to rational polypharmacology. Research employs various computational methods to fill the ligand-target interaction matrix, where rows correspond to ligands and columns to targets [10]. Four primary virtual screening scenarios exist:

- Scenario S0: Search for new interactions where each ligand and each protein are represented by some number of interactors

- Scenario S1: Prediction of the activity of a new ligand towards targets with known ligand spectra

- Scenario S2: Prediction of the activity of a new protein towards ligands with known target spectra

- Scenario S3: Prediction of the interaction of a new ligand and a new protein

Scenarios S2 and S3 can be implemented only with proteochemometric (PCM) modeling, which represents both targets and ligands by their descriptors in a single model, while S1 is typical for SAR models based on structural descriptions of ligands [10].

Comparative Performance of Target Prediction Methods

Recent systematic comparisons of target prediction methods have evaluated stand-alone codes and web servers using shared benchmark datasets of FDA-approved drugs. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of major prediction methods [5].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Target Prediction Methods for Polypharmacology

| Method | Type | Algorithm | Data Source | Key Application | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolTarPred | Ligand-centric | 2D similarity, MACCS fingerprints | ChEMBL 20 | Drug repurposing | Most effective method in comparative studies; optimal with Morgan fingerprints |

| PPB2 | Ligand-centric | Nearest neighbor/Naïve Bayes/deep neural network | ChEMBL 22 | Polypharmacology profiling | Uses MQN, Xfp and ECFP4 fingerprints; examines top 2000 similar ligands |

| RF-QSAR | Target-centric | Random forest | ChEMBL 20 & 21 | Target prediction | Employs ECFP4 fingerprints; considers multiple similarity thresholds |

| TargetNet | Target-centric | Naïve Bayes | BindingDB | Target profiling | Uses multiple fingerprint types including FP2, MACCS, E-state |

| CMTNN | Target-centric | ONNX runtime | ChEMBL 34 | Multi-target prediction | Stand-alone code with neural network architecture |

| SuperPred | Ligand-centric | 2D/fragment/3D similarity | ChEMBL & BindingDB | Target fishing | Uses ECFP4 fingerprints for similarity assessment |

The evaluation reveals that MolTarPred demonstrates superior performance for drug repurposing applications, particularly when using Morgan fingerprints with Tanimoto scores rather than MACCS fingerprints with Dice scores [5]. High-confidence filtering of interaction data (using confidence score ≥7) improves prediction reliability but reduces recall, making it less ideal for comprehensive drug repurposing where broader target identification is valuable.

SAR vs. Proteochemometric Modeling Performance

Comparative studies between SAR and PCM modeling under the S1 scenario (predicting activity of new ligands against known targets) have yielded important insights. Research utilizing data from nuclear receptors (NR), G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), chymotrypsin family proteases (PA), and protein kinases (PK) from the Papyrus dataset (based on ChEMBL) demonstrates that including protein descriptors in PCM modeling does not necessarily improve prediction accuracy for S1 scenarios [10].

The validation employed a rigorous five-fold cross-validation using ligand exclusion repeated five times. For SAR models, separate models were created for each distinct protein target using training sets of ligands classified by their target identifiers. For PCM models, both ligand and protein descriptors were incorporated, with the same ligand-based splitting to ensure comparable validation [10].

Table 2: SAR vs. PCM Model Performance Comparison (S1 Scenario)

| Protein Family | SAR Model R² | PCM Model R² | Performance Advantage | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Receptors | 0.58 | 0.55 | SAR superior | Limited protein diversity reduces PCM benefits |

| GPCRs | 0.62 | 0.59 | SAR superior | High ligand specificity favors ligand-based models |

| Protein Kinases | 0.65 | 0.63 | SAR superior | Conservative binding pockets limit PCM value |

| Proteases | 0.61 | 0.60 | Comparable | Mixed protein characteristics show similar performance |

The findings indicate that increasing the dimensionality of the feature space by including protein descriptors may lead to an unjustified increase in computational costs without improving predictive accuracy for the common S1 virtual screening scenario [10].

Experimental Protocols for Polypharmacology Validation

Workflow for Multi-Target Drug Discovery

The integrated computational and experimental workflow for polypharmacology research involves multiple stages from initial design to final validation [9] [5].

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Target Prediction Protocol Using MolTarPred

Purpose: To identify potential protein targets for a query small molecule using the optimal ligand-centric approach [5].

Materials:

- Query molecule in SMILES format

- Local installation of ChEMBL database (version 34 recommended)

- MolTarPred stand-alone code

- PostgreSQL with pgAdmin4 for database management

Procedure:

- Database Preparation:

- Retrieve bioactivity records from ChEMBL with standard values (IC50, Ki, or EC50) below 10000 nM

- Filter out targets with names containing "multiple" or "complex"

- Remove duplicate compound-target pairs

- Apply high-confidence filtering (confidence score ≥7) for improved reliability

Similarity Calculation:

- Convert query molecule to Morgan fingerprints (radius 2, 2048 bits)

- Calculate Tanimoto similarity against all compounds in the database

- Retrieve targets of the top 1, 5, 10, and 15 most similar compounds

Target Prioritization:

- Rank targets based on similarity scores and occurrence frequency

- Apply consensus scoring from multiple similarity thresholds

- Generate mechanism of action hypotheses for further validation

Validation:

- Use five-fold cross-validation with ligand exclusion

- Repeat validation five times with different random seeds

- Benchmark against known FDA-approved drugs excluded from training data

SAR vs. PCM Comparative Validation Protocol

Purpose: To rigorously compare the predictive performance of SAR and PCM models under the S1 virtual screening scenario [10].

Materials:

- Papyrus dataset or ChEMBL database with "Medium" and "High" quality entries

- Protein targets from major families (NR, GPCRs, PA, PK)

- Standardized molecular descriptors for ligands (e.g., ECFP4, Morgan fingerprints)

- Protein descriptors (e.g., amino acid composition, domain information)

Procedure:

- Data Curation:

- Select data for four protein families: nuclear receptors, GPCRs, proteases, kinases

- Exclude mutant variants to maintain consistency

- Standardize pKi values for uniform activity measurement

Model Training:

- For SAR: Create separate models for each protein target using random forest classifiers

- For PCM: Build unified models incorporating both ligand and protein descriptors

- Use identical training/test splits for fair comparison

Validation Scheme:

- Implement five-fold cross-validation using ligand exclusion

- Repeat the process five times with different random partitions

- Evaluate using R², RMSE, and concordance index metrics

Analysis:

- Compare performance metrics between SAR and PCM approaches

- Conduct statistical significance testing (e.g., paired t-tests)

- Analyze computational requirements and scalability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Polypharmacology Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Key Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL, BindingDB, PubChem, DrugBank | Provide experimentally validated drug-target interactions | Foundation for ligand-centric prediction and model training |

| Target Prediction Servers | MolTarPred, PPB2, SuperPred, TargetNet | Identify potential targets for query molecules | Initial hypothesis generation for drug repurposing |

| Chemical Informatics | RDKit, OpenBabel, CDK | Compute molecular descriptors and fingerprints | Feature generation for QSAR and machine learning models |

| Structure-Based Tools | AutoDock, Schrödinger, MOE | Molecular docking and structure-based design | Target-centric polypharmacology for targets with 3D structures |

| AI/ML Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn | Build predictive models for multi-target activity | Deep learning approaches for polypharmacology optimization |

| Validation Assays | SPR, HTRF, AlphaScreen | Experimental confirmation of multi-target engagement | In vitro validation of predicted polypharmacological profiles |

AI-Driven Advancements in Polypharmacology

Artificial Intelligence has dramatically accelerated polypharmacology research through several key technological approaches [9] [11]:

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Applications

Machine learning (ML) algorithms, including random forest, support vector machines, and naïve Bayes classifiers, enable the prediction of multi-target activities from chemical structures. Deep learning (DL) approaches, particularly multilayer perceptrons (MLP), convolutional neural networks (CNN), and long short-term memory recurrent neural networks (LSTM-RNN), show superior performance in handling large and complex datasets for polypharmacology prediction [11].

These AI methods can identify complex, non-linear relationships between chemical features and biological activities across multiple targets, enabling the de novo design of dual and multi-target compounds. Several AI-generated compounds have demonstrated biological efficacy in vitro, validating the computational predictions [9].

Network Biology and Systems Pharmacology

Network-based approaches study relationships between molecules, emphasizing their location affinities to reveal drug repurposing potentials. By analyzing protein-protein interactions (PPIs), drug-disease associations (DDAs), and drug-target associations (DTAs), these methods provide a systems-level understanding of how multi-target drugs modulate biological networks [9].

The integration of omics data, CRISPR functional screens, and pathway simulations further enhances the rational design of polypharmacological agents tailored to the complexity of human disease networks [9].

Polypharmacology has evolved from a controversial concept to a mainstream principle in drug discovery. The intentional design of multi-target therapeutics represents a paradigm shift that acknowledges the network nature of human disease. Computational approaches, particularly AI-driven methods, have been instrumental in this transition, enabling the prediction and optimization of polypharmacological profiles with increasing accuracy.

The integration of robust computational prediction with rigorous experimental validation provides a powerful framework for addressing the complexity of multifactorial diseases. As these methodologies continue to mature, AI-enabled polypharmacology is poised to become a cornerstone of next-generation drug discovery, with the potential to deliver more effective therapies tailored to the complex network pathophysiology of human diseases [9]. The critical role of polypharmacology extends beyond initial drug discovery to drug repurposing, where understanding multi-target profiles can reveal new therapeutic applications for existing drugs, accelerating the delivery of treatments to patients while reducing development costs and risks.

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) data mining is a cornerstone of modern rational drug design, enabling researchers to understand how chemical modifications influence a compound's biological activity. By analyzing SAR patterns, medicinal chemists can optimize lead compounds for enhanced potency, selectivity, and favorable pharmacokinetic properties. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to three pivotal databases—ChEMBL, DrugBank, and BindingDB—for SAR data mining within the context of ligand-target SAR matrix analysis research. These databases provide complementary data types and functionalities that, when used collectively, offer a powerful infrastructure for investigating the complex relationships between chemical structures and their biological effects against therapeutic targets. The integration of these resources enables the construction of comprehensive SAR matrices that map multiple chemical series against diverse biological targets, facilitating pattern recognition and predictive model building essential for accelerating drug discovery pipelines.

Database Origins and Specializations

ChEMBL is a manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, maintained by the European Bioinformatics Institute. It brings together chemical, bioactivity, and genomic data to aid the translation of genomic information into effective new drugs [12]. Since its first public launch in 2009, ChEMBL has grown significantly to become a Global Core Biodata Resource recognized by the Global Biodata Coalition [13]. The database predominantly contains bioactivity data extracted from scientific literature and patents, with a focus on quantitative measurements such as IC50, Ki, and EC50 values essential for SAR analysis.

DrugBank is a comprehensive database containing detailed information about FDA-approved and experimental drugs, along with their targets, mechanisms, and pharmacokinetic properties [14]. Unlike ChEMBL, DrugBank places greater emphasis on clinical and regulatory information, making it particularly valuable for understanding established drug-target relationships and repurposing opportunities. The database contains over 17,000 drug entries and 5,000 protein targets, with information meticulously validated through both manual and automated processes [14].

BindingDB specializes in measured binding affinities, focusing primarily on the interactions of proteins considered to be candidate drug-targets with small, drug-like molecules [15]. As the first public molecular recognition database, BindingDB contains approximately 3.2 million binding data points for 1.4 million compounds and 11.4 thousand targets [16] [15]. The database derives its data from various measurement techniques, including enzyme inhibition and kinetics, isothermal titration calorimetry, NMR, and radioligand and competition assays [15].

Quantitative Database Comparison

Table 1: Key Characteristics of SAR Mining Databases

| Characteristic | ChEMBL | DrugBank | BindingDB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Bioactive molecules & drug-target interactions | Approved drugs & clinical candidates | Protein-ligand binding affinities |

| Total Compounds | ~2.4 million research compounds [13] | ~17,000 drugs [14] | ~1.4 million compounds [16] |

| Bioactivity Measurements | ~20.3 million [14] | Not specifically quantified | ~3.2 million binding data [15] |

| Target Coverage | Broad, including proteins, cell lines, tissues | ~5,000 protein targets [14] | ~11,400 proteins [16] |

| Curation Approach | Manual expert curation [14] | Hybrid (manual + automated) [14] | Hybrid (manual + automated) [14] |

| Data Types | IC50, Ki, EC50, ADMET, clinical candidates | Mechanisms, pharmacokinetics, pathways | Kd, Ki, IC50, ITC, NMR data |

| Access | Free and open [14] | Free for non-commercial use [13] | Free and open [14] |

| Update Frequency | Periodic major releases [13] | Regularly updated | Monthly updates [16] |

Table 2: Data Content and SAR Applications

| Feature | ChEMBL | DrugBank | BindingDB |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAR-Ready Data | Extensive quantitative bioactivities | Limited quantitative data | Focused on binding affinities |

| Clinical Context | Clinical candidate drugs [13] | Comprehensive drug information | Limited clinical context |

| Target Validation | Strong for early-stage discovery | Strong for clinical targets | Strong for biophysical studies |

| Specialized Content | Natural product-likeness, chemical probes | Drug metabolism, pathways | Host-guest systems, CSAR data |

| Polypharmacology | Extensive via target cross-screening | Drug-focused interactions | Limited to binding data |

| Structure Formats | SMILES, Standardized InChIs | SMILES, 2D structures | SMILES, 2D/3D SDF files [16] |

Methodologies for SAR Data Mining

Workflow for Comprehensive SAR Matrix Construction

Diagram 1: SAR data mining workflow

Protocol 1: Multi-Database SAR Extraction

Objective: Extract comprehensive SAR data for a target protein family across all three databases.

Materials:

- Database access credentials (where required)

- Chemical structure standardization toolkit (e.g., RDKit)

- Data integration platform (e.g., KNIME, Python pandas)

Procedure:

- Target Identification: Define UniProt IDs or gene symbols for target proteins of interest.

- ChEMBL Query:

- Use ChEMBL web services or direct database queries to retrieve bioactivity data

- Filter for specific assay types (e.g., 'B' for binding) and measurement types (IC50, Ki)

- Extract associated chemical structures, standard InChI keys, and exact activities

- DrugBank Query:

- Search for approved drugs and clinical candidates targeting protein family

- Extract known mechanisms of action, therapeutic indications, and structural data

- Cross-reference with ChEMBL compounds to identify clinical-stage molecules

- BindingDB Query:

- Data Integration:

- Standardize chemical structures using consistent representation

- Align activity measurements using uniform units (nM preferred)

- Resolve conflicts through source priority ranking (curated > literature-derived)

Protocol 2: SAR Matrix Analysis for Lead Optimization

Objective: Construct and analyze SAR matrices to guide chemical optimization.

Materials:

- Molecular fingerprinting methods (Morgan, MACCS)

- Similarity calculation algorithms (Tanimoto, Dice)

- Data visualization tools (Matplotlib, Spotfire)

Procedure:

- Chemical Series Identification:

- Cluster compounds based on structural similarity (Tanimoto > 0.7)

- Identify core scaffolds and R-group substitution patterns

- SAR Matrix Population:

- Create compound-target activity matrices with cells representing -log(activity) values

- Highlight data gaps for future testing priorities

- Pattern Recognition:

- Identify activity cliffs (small structural changes leading to large potency changes)

- Map selectivity profiles across related targets

- Corrogate substituent effects with potency and physicochemical properties

- Visualization:

- Generate heatmaps with hierarchical clustering of compounds and targets

- Create R-group decomposition diagrams to visualize substituent effects

- Plot matched molecular pairs to isolate specific structural transformations

Database-Specific Technical Implementation

ChEMBL: Advanced SAR Mining Techniques

ChEMBL provides several specialized features for deep SAR analysis. The database includes approximately 17,500 approved drugs and clinical candidate drugs in addition to its 2.4 million research compounds, enabling researchers to contextualize their SAR within the landscape of known therapeutics [13]. For SAR matrix analysis, particularly valuable features include:

Target Family Profiling: ChEMBL's extensive target classification system enables systematic analysis of compound selectivity across protein families. Researchers can extract all bioactivity data for kinase, GPCR, or protease families to build comprehensive selectivity profiles.

Time-Resolved SAR Analysis: The database includes temporal information about when compounds were published, allowing analysis of how SAR for particular targets has evolved over time, revealing trends in medicinal chemistry strategies.

Activity Confidence Grading: ChEMBL assigns confidence scores to target-compound interactions, enabling data quality filtering to ensure robust SAR interpretations. High-confidence interactions (score 9) provide the most reliable basis for SAR modeling.

DrugBank: Clinical SAR Contextualization

While DrugBank contains fewer quantitative bioactivity measurements than ChEMBL or BindingDB, it provides crucial clinical context for SAR analysis. Key SAR-relevant features include:

Drug-Target Pathway Mapping: DrugBank links drugs to their protein targets within biological pathways, enabling systems-level SAR analysis where compound effects can be understood in the context of network perturbations rather than isolated target interactions.

Pharmacokinetic SAR Integration: The database provides extensive ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) data for drugs, allowing correlation of structural features not just with potency but with drug-like properties essential for clinical success.

Mechanism of Action Annotations: Precise mechanism data (e.g., agonist, antagonist, allosteric modulator) enables researchers to classify SAR by mechanism type, recognizing that different mechanisms may have distinct structural requirements even for the same target.

BindingDB: High-Quality Affinity Data for Structure-Based SAR

BindingDB specializes in providing detailed binding affinity data particularly suited for structure-based SAR analysis and computational method validation:

Biophysical Method Annotation: BindingDB tags data with measurement methods (ITC, SPR, etc.), enabling method-specific SAR analysis important because different techniques may yield systematically different affinity measurements [15].

Structure-Ready Data: The database provides compounds in ready-to-dock 2D and 3D formats, facilitating direct integration with molecular modeling workflows [16]. The 3D structures are computed with Vconf conformational analysis, ensuring biologically relevant geometries.

Validation Sets: BindingDB offers specifically curated validation sets for benchmarking SAR prediction methods, including time-split sets useful for assessing model performance on novel chemotypes [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for SAR Mining Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function in SAR Analysis | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| KNIME Analytics Platform | Workflow-based data integration and analysis | BindingDB-provided KNIME workflows for data retrieval and target prediction [16] |

| RDKit Cheminformatics Library | Chemical structure standardization and descriptor calculation | Generating Morgan fingerprints for compound similarity analysis [17] |

| MolTarPred | Target prediction for novel chemotypes | Generating hypotheses for off-target effects in SAR matrices [17] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Validation of binding affinities for key compounds | Orthogonal confirmation of SAR trends from database mining [18] |

| FASTA Sequence Files | Target similarity analysis and selectivity assessment | BindingDB target sequences for understanding cross-reactivity [16] |

| Structure-Activity Modeling Tools | Quantitative SAR model development | Converting SAR matrices to predictive models for compound prioritization |

Integrated SAR Mining Case Study: Kinase Inhibitor Profiling

To illustrate the power of integrating all three databases, consider a case study on kinase inhibitor profiling:

Step 1: Using ChEMBL, extract all available bioactivity data for compounds tested against kinase targets, focusing on IC50 values from enzymatic assays. This yields a preliminary SAR matrix covering multiple chemical series.

Step 2: Query DrugBank to identify approved kinase inhibitors and their specific clinical indications, adding important therapeutic context to the SAR analysis.

Step 3: Access high-quality binding affinity data from BindingDB for key kinase-compound pairs, particularly those measured using biophysical methods like SPR that provide precise Kd values.

Step 4: Integrate data sources to build a comprehensive kinase inhibitor SAR matrix, highlighting how different chemical scaffolds achieve selectivity across the kinome.

Step 5: Validate SAR trends using experimental data from the original publications referenced across all three databases.

This integrated approach reveals structure-selectivity relationships that would be difficult to discern from any single database, enabling more informed design of selective kinase inhibitors with reduced off-target effects.

ChEMBL, DrugBank, and BindingDB provide complementary and powerful resources for SAR data mining within ligand-target matrix analysis research. ChEMBL offers broad coverage of bioactive compounds with quantitative activities, DrugBank provides essential clinical context, and BindingDB delivers high-quality binding affinity data suitable for structural studies. By leveraging the unique strengths of each database through the methodologies outlined in this technical guide, researchers can construct comprehensive SAR matrices that accelerate the identification and optimization of novel therapeutic agents. The continued evolution of these databases, particularly their increasing integration with computational modeling and AI approaches, promises to further enhance their utility in future drug discovery campaigns.

In the field of computational drug discovery, predicting the interaction between small molecules and their biological targets is a fundamental challenge. Two dominant computational paradigms have emerged: target-centric and ligand-centric prediction approaches [19] [20]. These methodologies address the reverse problem of virtual screening and serve crucial roles in polypharmacology prediction, drug repositioning, and target deconvolution of phenotypic screening hits [19] [20]. Within the broader context of structure-activity relationship (SAR) matrix analysis research, understanding the fundamental principles, relative strengths, and limitations of these approaches is essential for designing effective drug discovery pipelines. This foundational comparison examines the core architectures of these methodologies, their technical implementation, and performance characteristics, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate strategies for specific applications.

Core Conceptual Frameworks

Target-Centric Approaches

Target-centric methods operate on the principle of building a dedicated predictive model for each individual biological target [19] [20]. In this architecture, a panel of models is constructed, with each model trained to estimate the likelihood that a query molecule will interact with its specific protein target. These methods typically employ supervised learning techniques, using known active and inactive compounds for each target to train classifiers such as Random Forest, Naïve Bayes, or Support Vector Machines [5] [21]. The model training process utilizes quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) principles, where molecular descriptors or fingerprints of ligands are correlated with biological activity against a specific target [10] [21].

A significant limitation of target-centric approaches is their restricted coverage of the proteome. These methods can only evaluate targets for which sufficient bioactivity data exists to build a reliable model [19] [20]. For instance, some methods require a minimum number of known ligands per target (e.g., 5-30 ligands) to qualify for model construction [19] [20]. This constraint inherently limits target-centric methods to a fraction of the potential target space, making them potentially blind to thousands of biologically relevant targets that lack comprehensive ligand annotation.

Ligand-Centric Approaches

Ligand-centric approaches fundamentally differ by shifting the focus from target models to chemical similarity principles [19] [20]. These methods predict targets for a query molecule by comparing its chemical features to a large knowledge base of target-annotated molecules. The underlying hypothesis is that structurally similar molecules are likely to share biological targets [21] [20]. This strategy does not require building individual target models but instead relies on comprehensive databases of known ligand-target interactions, such as ChEMBL or BindingDB [5] [20].

The primary advantage of ligand-centric methods is their extensive coverage of the target space. Since these approaches can interrogate any target that has at least one known ligand, they typically evaluate thousands more potential targets compared to target-centric methods [19] [20]. This comprehensive coverage makes ligand-centric approaches particularly valuable for exploratory research where the relevant targets may not be known in advance, such as in target deconvolution of phenotypic screening hits [19].

Methodological Implementation

Data Requirements and Preparation

Both prediction approaches rely heavily on comprehensive, high-quality bioactivity data for training and validation. The ChEMBL database is widely utilized across both paradigms due to its extensive collection of experimentally validated bioactivity data, including drug-target interactions, inhibitory concentrations, and binding affinities [5] [19]. Proper data curation is essential for building reliable models, typically involving several standardization steps:

- Activity Data Filtering: Selecting bioactivity records with standard values (IC₅₀, Kᵢ, EC₅₀, Kd) below a specific threshold (commonly 10 µM for active compounds) [21]

- Confidence Scoring: Applying minimum confidence scores (e.g., 7-9 in ChEMBL) to ensure only well-validated direct target interactions are included [5] [20]

- Redundancy Removal: Eliminating duplicate compound-target pairs and filtering out non-specific or multi-protein targets [5]

- Data Partitioning: Implementing temporal splits or scaffold-based splits to avoid artificial inflation of performance metrics [10]

For ligand-centric methods, the knowledge base must be extensively populated to maximize target coverage. Recent implementations have utilized databases containing over 500,000 molecules annotated with more than 4,000 targets, representing nearly 900,000 ligand-target associations [20].

Algorithmic Approaches and Technical Execution

Target-Centric Workflow: Target-centric implementation involves training individual machine learning models for each qualifying target. The standard protocol includes:

- Target Selection: Identifying targets with sufficient bioactivity data (typically ≥20-30 known ligands) [19]

- Feature Engineering: Encoding molecular structures using fingerprints (ECFP, MACCS, Morgan) or chemical descriptors [5] [21]

- Model Training: Applying classification algorithms (Random Forest, Naïve Bayes, Neural Networks) to distinguish active from inactive compounds [5] [21]

- Model Validation: Using cross-validation techniques appropriate for the virtual screening scenario (S1 scenario: new compounds against known targets) [10]

Ligand-Centric Workflow: Ligand-centric implementation focuses on similarity searching and requires the following steps:

- Molecular Encoding: Representing both query and database molecules using appropriate fingerprints (Morgan, ECFP, MACCS) [5] [20]

- Similarity Metric Selection: Calculating molecular similarity using Tanimoto, Dice, or other appropriate coefficients [5]

- Nearest Neighbor Identification: Retrieving the top K most similar database molecules to the query (typically K=1-15) [5] [20]

- Target Inference: Transferring target annotations from nearest neighbors to the query molecule, often with confidence scoring [20]

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between Prediction Approaches

| Aspect | Target-Centric Approach | Ligand-Centric Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Unit of Modeling | Individual target proteins | Entire chemical space |

| Core Algorithm | QSAR classification per target | Similarity searching |

| Data Requirements | Multiple ligands per target | Single ligand per target suffices |

| Typical Features | Molecular fingerprints/descriptors | Molecular fingerprints |

| Coverage Scope | Limited to modeled targets | Comprehensive (any target with known ligands) |

| Implementation Examples | RF-QSAR, TargetNet, CMTNN [5] | MolTarPred, PPB2, SuperPred [5] |

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Rigorous benchmarking studies have provided insights into the relative performance of target-centric and ligand-centric approaches. A precise comparison study evaluating seven target prediction methods revealed that optimal performance depends on the specific application requirements [5]. The following table summarizes key performance characteristics based on recent systematic evaluations:

Table 2: Performance Comparison Based on Systematic Studies

| Performance Metric | Target-Centric (Best Performing) | Ligand-Centric (Best Performing) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | 0.75 [21] | 0.348 [20] | Varies significantly with query molecule |

| Recall | 0.61 [21] | 0.423 [20] | Dependent on target coverage |

| False Negative Rate | 0.25 [21] | N/A | Higher for approved drugs [19] |

| Target Space Coverage | Limited (hundreds of targets) [19] | Extensive (4,000+ targets) [20] | Ligand-centric covers 8-10x more targets |

| Drug Target Prediction | Challenging [19] | More challenging than non-drugs [19] | Drugs have harder-to-predict targets |

Application-Specific Performance

The suitability of each approach varies significantly depending on the application context:

Target-Centric Strengths:

- Scenario S1 Applications: Superior performance when predicting new ligands for established targets with abundant bioactivity data [10]

- Model Optimization: Capable of achieving high precision (f1-score >0.8) for well-characterized targets [21]

- Consensus Strategies: Combining multiple target-centric models can achieve true positive rates of 0.98 with minimal false negatives in top predictions [21]

Ligand-Centric Strengths:

- Exploratory Research: Maximum target space coverage enables discovery of unexpected off-target effects [19] [20]

- Novel Target Identification: Ability to identify targets with limited ligand information (as few as one known ligand) [19]

- Polypharmacology Profiling: Comprehensive mapping of drug-target interactions reveals an average of 8-11.5 targets per drug below 10 µM [19] [20]

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Standardized Benchmarking Protocol

To ensure fair comparison between prediction approaches, researchers should implement standardized benchmarking protocols:

Dataset Curation:

Performance Assessment:

Validation Strategies:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Tools and Resources for Target Prediction Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL [5] [19], BindingDB [5], PubChem [19] | Data sourcing for both approaches | Experimentally validated interactions, confidence scoring |

| Target-Centric Platforms | RF-QSAR [5], TargetNet [5], CMTNN [5] | Target-specific QSAR modeling | Random Forest, Naïve Bayes, Neural Network implementations |

| Ligand-Centric Platforms | MolTarPred [5], PPB2 [5], SuperPred [5] | Similarity-based target fishing | Multiple fingerprint support, similarity metrics |

| Fingerprint Methods | Morgan fingerprints [5], ECFP [5] [21], MACCS [5] | Molecular representation | Tanimoto and Dice similarity metrics |

| Validation Frameworks | TF-benchmark [19], Custom temporal splits [21] | Method performance assessment | Specialized for drug target prediction challenges |

Target-centric and ligand-centric prediction approaches represent complementary paradigms in computational target prediction, each with distinct advantages and optimal application domains. Target-centric methods excel in precision for well-characterized targets with abundant bioactivity data, making them suitable for lead optimization projects. In contrast, ligand-centric approaches provide unparalleled coverage of the target space, enabling discovery of novel drug-target interactions and comprehensive polypharmacology profiling. The choice between these approaches should be guided by the specific research objectives, with target-centric methods preferred for focused interrogation of known target families and ligand-centric methods superior for exploratory research and target deconvolution. As bioactivity databases continue to expand and machine learning methodologies advance, both approaches will play increasingly important roles in accelerating drug discovery and repositioning efforts. Future developments will likely focus on hybrid methodologies that leverage the strengths of both paradigms while addressing their respective limitations in coverage and precision.

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) analysis is a cornerstone of medicinal chemistry, providing the fundamental basis for compound optimization during hit-to-lead and lead optimization campaigns [22]. Traditionally, SAR exploration has been a target-dependent endeavor, where structural analogues are generated and tested against a specific protein target to elucidate the relationship between molecular structure and biological activity [23]. However, a transformative concept known as SAR transfer has emerged, enabling researchers to leverage SAR information across different protein targets [23]. This approach recognizes that pairs of analogue series (AS) consisting of compounds with corresponding substituents and comparable potency progression can represent SAR transfer events for the same target or across different targets [23].

SAR transfer plays a crucial role when an analogue series with desirable potency progression exhibits unfavorable in vitro or in vivo properties, necessitating its replacement with another series displaying comparable SAR characteristics [23]. This strategy effectively transfers medicinal chemistry knowledge from one structural context to another, potentially accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics with improved properties. The systematic computational identification of SAR transfer events has revealed that this phenomenon occurs frequently across different targets, suggesting that generally applied medicinal chemistry strategies—such as using hydrophobic substituents of increasing size to "fill" hydrophobic binding pockets—may underlie many cross-target SAR patterns [23] [24].

Table 1: Key Terminology in SAR Transfer Analysis

| Term | Definition | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Analogue Series (AS) | A set of compounds sharing a common core structure with different substitutions at one or more sites [25] | Forms the basic unit for SAR analysis and transfer |

| SAR Transfer | Transfer of potency progression patterns from one analogue series to another, potentially across different targets [23] | Enables knowledge transfer and scaffold hopping |

| Matched Molecular Pair (MMP) | A pair of compounds differing only at a single site [25] | Facilitates intuitive SAR analysis through minimal structural changes |

| Matched Molecular Series (MMS) | Series of compounds with a common core and systematic variations at a single site [25] | Extends MMP concept to series with multiple analogues |

| Proteochemometric (PCM) Modeling | Modeling approach that uses descriptors of both ligands and proteins [10] | Enables prediction of interactions for novel targets |

Computational Methodologies for Identifying SAR Transfer Events

Foundation Concepts and Analogue Series Identification

The systematic identification of SAR transfer events begins with the extraction of analogue series from large compound databases. Modern databases such as ChEMBL and PubChem contain millions of compounds with associated activity annotations, providing a rich resource for SAR analysis [25]. An analogue series is typically defined as a set of three or more compounds sharing the same core structure (key) with different substituents (value fragments) at one or more sites [23]. The Bemis-Murcko scaffold approach represents an early method for scaffold decomposition, defining scaffolds as combinations of ring systems and linker chains while ignoring acyclic terminal side chains [25]. However, this approach does not allow ring substitutions, limiting its applicability for comprehensive SAR transfer analysis.

The Matched Molecular Pair (MMP) concept has become fundamental to modern analogue series identification. An MMP is defined as a pair of compounds that differ only at a single site, enabling clear interpretation of SAR resulting from specific structural changes [25]. The fragmentation-based MMP algorithm introduced by Hussain and Rea systematically applies fragmentation rules to each molecule, cutting exocyclic single bonds to generate potential core-fragment pairs [23] [25]. This approach efficiently processes large datasets without relying on predefined transformations or costly pairwise comparisons. Extending the MMP concept leads to Matched Molecular Series (MMS), which comprise compounds with a common core and systematic variations at a single site, forming the basis for identifying analogue series with SAR transfer potential [25].

Context-Dependent Similarity Assessment Using NLP Techniques

A groundbreaking advancement in SAR transfer analysis involves the adaptation of Natural Language Processing (NLP) methodologies for assessing context-dependent similarity of molecular substituents. This innovative approach, conceptually novel in computational medicinal chemistry, treats value fragments (substituents) as "words" and analogue series as "sentences" [23]. The Continuous Bag of Words (CBOW) variant of Word2vec generates embedded fragment vectors (EFVs) by predicting fragments based on surrounding fragments in a sequence, effectively capturing the context in which specific substituents appear [23].

This context-dependent similarity assessment offers significant advantages over conventional fragment representation (CFR), which typically relies on Morgan fingerprints and molecular quantum number (MQN) descriptors [23]. While CFR quantifies structural and property similarity through fixed descriptors, EFVs capture the contextual relationships between substituents based on their occurrence patterns across multiple analogue series, enabling the identification of non-classical bioisosteres and more nuanced substituent-property relationships [23].

Analogue Series Alignment and SAR Transfer Detection

The core computational methodology for identifying SAR transfer events involves the alignment of analogue series based on substituent similarity. The Needleman-Wunsch dynamic programming algorithm, typically used for biological sequence alignment, is adapted to align pairs of analogue series by maximizing the overall similarity of their substituent sequences [23]. The alignment score is calculated using the recurrence relation:

[D{i,j} = \max\begin{cases} D{i-1,j-1} + s(qi,tj) \ D{i-1,j} - \text{gap} \ D{i,j-1} - \text{gap} \end{cases}]

where (qi) represents the i-th fragment of the query AS, (tj) represents the j-th fragment of the target AS, (s(qi,tj)) denotes the similarity between fragments (qi) and (tj), and gap represents the gap penalty [23]. For SAR transfer applications, the gap penalty is typically set to zero due to the short length of analogue series compared to biological sequences [23].

This alignment methodology enables the detection of SAR transfer events by identifying pairs of analogue series with different core structures but analogous potency progression patterns across corresponding substituents [23]. Furthermore, it facilitates the prediction of potent analogues for a query series by identifying "SAR transfer analogues" in target series that represent potential extensions to the query series with likely increased potency [23].

Diagram 1: Computational Workflow for SAR Transfer Analysis. The pipeline begins with compound database processing, proceeds through analogue series identification and embedding, and concludes with SAR transfer detection and analogue prediction.

Experimental Validation and Platform Technologies

Structural Dynamics Response (SDR) Assay Platform

The validation of SAR transfer events requires experimental platforms capable of efficiently profiling compound activity across multiple targets. Recent advances have led to the development of the Structural Dynamics Response (SDR) assay, a general platform for studying protein pharmacology using ligand-dependent structural dynamics [26]. This innovative approach exploits the finding that ligand binding to a target protein can modulate the luminescence output of N- or C-terminal NanoLuc luciferase (NLuc) fusions or its split variants utilizing α-complementation [26].

The SDR assay format provides several advantages for SAR transfer studies. First, it offers a gain-of-signal output accompanying ligand binding, contrary to the loss-of-signal typical for enzymatic inhibition assays [26]. Second, it enables direct detection of ligand binding without reliance on functional activity, making it applicable to diverse enzyme classes and even non-enzyme proteins [26]. Third, it can reveal mechanistic subtleties such as cofactor-dependent binding and allosteric effects that might be obscured in conventional activity-based assays [26]. The platform has been successfully applied to multiple protein families, including kinases, isomerases, reductases, and ligases, demonstrating its general applicability for SAR studies [26].

Experimental Protocol: SDR Assay for SAR Analysis

Purpose: To quantitatively measure ligand binding and detect SAR transfer events across different protein targets using the Structural Dynamics Response assay platform [26].

Materials:

- Target proteins of interest with C-terminal or N-terminal NLuc or HiBiT fusions

- NLuc substrate (furimazine)

- Ligand compounds for screening

- Assay buffers appropriate for each target protein

- White solid-bottom assay plates

- Luminescence plate reader

Procedure:

- Protein Preparation: Express and purify target proteins as NLuc fusions or prepare cell lysates containing endogenously expressed gene-edited proteins with HiBiT tags [26].

- Assay Setup: In a low-volume assay plate, mix the target protein with ligands across a concentration range suitable for generating concentration-response curves. Include appropriate controls (vehicle-only, reference ligands) [26].

- Signal Detection: Add NLuc substrate (furimazine) and immediately measure luminescence output using a plate reader. For HiBiT-tagged proteins, first supplement with LgBiT to enable α-complementation before substrate addition [26].

- Data Analysis: Calculate SDR50 values (concentration producing half-maximal signal response) from the concentration-response data. Compare SDR50 values with conventional IC50 values from functional assays where available [26].

- SAR Transfer Detection: Identify analogous potency progression patterns across different analogue series and target proteins by comparing the relative potencies of corresponding substituents [26].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SAR Transfer Studies

| Reagent/Technology | Function in SAR Transfer Studies | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| NanoLuc Luciferase (NLuc) | Reporter protein for SDR assays [26] | Small size, bright signal, ATP-independent |

| HiBiT/LgBiT System | Split luciferase for α-complementation [26] | Enables tagging with minimal perturbation |

| CHEMBL Database | Source of compound activity data [23] [10] | Curated bioactivity data, standardized targets |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics toolkit [23] | MMP fragmentation, descriptor calculation |

| Matched Molecular Pairs Algorithm | Identifies analogous compounds [23] [25] | Systematic single-cut fragmentation |

Analysis and Applications in Drug Discovery

Comparative Efficiency of SAR and Proteochemometric Modeling

The effectiveness of SAR transfer must be evaluated against alternative approaches for predicting bioactivity across multiple targets. Proteochemometric (PCM) modeling represents a complementary methodology that uses descriptors of both ligands and target proteins to build unified models for entire families of related targets [10]. PCM extends the applicability domain beyond traditional SAR models and enables virtual screening according to multiple scenarios, including prediction of activity for new ligands against known targets (S1), new targets against known ligands (S2), and completely novel ligand-target pairs (S3) [10].

Comparative studies have revealed that for the S1 scenario (predicting activity of new ligands against known targets), SAR models based solely on ligand descriptors can perform equally well or better than PCM models that include both ligand and protein descriptors [10]. This finding suggests that including protein descriptors does not necessarily improve prediction accuracy for this specific scenario and may unnecessarily increase computational complexity [10]. However, for scenarios S2 and S3, which involve predicting interactions with novel targets, PCM modeling provides capabilities beyond traditional SAR approaches [10].

Practical Applications and Impact on Drug Discovery

SAR transfer analysis directly enables several impactful applications in drug discovery. First, it facilitates scaffold hopping—the identification of novel core structures that retain biological activity—which is crucial for addressing intellectual property constraints, improving drug-like properties, or overcoming toxicity issues associated with existing series [27]. Modern computational methods, particularly those utilizing deep learning-generated molecular representations, have significantly expanded scaffold hopping capabilities by capturing nuanced structure-activity relationships that may be overlooked by traditional similarity-based approaches [27].

Second, SAR transfer supports lead optimization by providing structural hypotheses for potency improvement based on analogous series. The identification of SAR transfer analogues in aligned series can suggest specific substituents likely to enhance potency in the query series [23]. This approach effectively leverages the extensive medicinal chemistry knowledge embedded in large compound databases, enabling data-driven decision-making in lead optimization campaigns.

Diagram 2: Impact Pathway of SAR Transfer Technologies. Computational analysis of compound databases combined with experimental validation enables multiple applications that accelerate drug discovery.

SAR transfer represents a paradigm shift in how medicinal chemists leverage structure-activity relationship information across different structural classes and protein targets. By combining innovative computational methodologies—such as context-dependent similarity assessment based on natural language processing principles—with advanced experimental platforms like the Structural Dynamics Response assay, researchers can systematically identify and validate SAR transfer events [23] [26]. This approach enables more efficient utilization of the vast repository of medicinal chemistry knowledge embedded in large compound databases, potentially accelerating lead optimization and scaffold hopping efforts.

The integration of SAR transfer analysis with other emerging technologies in drug discovery—including targeted protein degradation, DNA-encoded libraries, and artificial intelligence-driven molecular design—promises to further enhance its impact [22]. As these methodologies continue to mature, SAR transfer is poised to become an increasingly central component of the drug discovery toolkit, enabling more efficient navigation of chemical space and facilitating the development of novel therapeutics with optimized properties. Future advances will likely focus on improving the prediction accuracy for cross-target SAR patterns and expanding the applicability of these approaches to challenging target classes traditionally considered undruggable.

Computational Methods and Practical Applications in SAR Analysis

Target fishing, the computational prediction of a small molecule's protein targets, is a crucial discipline in modern drug discovery for elucidating mechanisms of action, understanding polypharmacology, and predicting off-target effects [28] [5]. This process fundamentally relies on analyzing the structure-activity relationship (SAR) matrix, which maps compounds to their biological targets. Within this context, machine learning (ML) models have emerged as powerful tools for ligand-based target prediction, leveraging known chemical structures and bioactivity data to infer new interactions [29] [28]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three predominant ML algorithms—Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest, and Naïve Bayes—for target fishing applications. We detail their underlying mechanisms, implementation protocols, and performance benchmarks, providing researchers with the practical knowledge required to deploy these models within a broader ligand-target SAR matrix analysis framework.

Core Machine Learning Models in Target Fishing

Support Vector Machine (SVM)

Principle and Application: SVM is a discriminative classifier that finds the optimal hyperplane to separate data points of different classes in a high-dimensional feature space. For target fishing, this typically translates to separating active from inactive compounds for a specific protein target [30]. Its effectiveness is particularly notable in scenarios with clear margins of separation, and its capability to handle high-dimensional data is beneficial for complex chemical descriptor sets.

A key strength of SVM is its use of kernel functions, which allow it to perform non-linear classification without explicitly transforming the feature space. This makes it particularly suited for the complex, non-linear relationships often found in chemical data. In one application to HIV-1 protease inhibition, researchers used Molecular Interaction Energy Components (MIECs) as descriptors for SVM training, achieving a significant enrichment in virtual screening with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.998, even when true positives accounted for only 1% of the screening library [30].

Technical Implementation: The MIEC-SVM approach combined structure modeling with statistical learning to characterize protein-ligand binding based on docked complex structures. The MIEC descriptors included van der Waals and electrostatic interaction energies between protease residues and the ligand, solvation energy, hydrogen bonding, and geometric constraints. A linear kernel function was identified as optimal for this classification task, especially when dealing with highly unbalanced datasets where active compounds represent a very small fraction (1% or 0.5%) [30]. To handle this imbalance, a weight parameter for positive samples (K+) was optimized, with values of 0.8 and 2.6 found to be optimal for positive-to-negative ratios of 1:100 and 1:200, respectively.

Random Forest

Principle and Application: Random Forest is an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees during training and outputs the mode of the classes (classification) or mean prediction (regression) of individual trees [31]. This "wisdom of the crowd" approach capitalizes on the collective decision-making of multiple models, typically resulting in superior performance compared to individual classifiers.

The algorithm introduces randomness through bootstrapping (creating multiple training subsets with replacement) and feature randomness (randomly selecting a subset of features for each tree) [31]. This randomness ensures the trees are diverse and decorrelated, reducing overfitting and increasing model robustness. Random Forest provides native feature importance metrics, offering valuable insights into which molecular descriptors most significantly contribute to target prediction—critical information for SAR analysis.

Technical Implementation and OOB Error: A distinctive advantage of Random Forest is its built-in validation mechanism through the Out-of-Bag (OOB) error. During bootstrap sampling, approximately one-third of the original data is left out of each tree's training set; these "out-of-bag" samples serve as a natural validation set [31] [32]. The OOB error is calculated by aggregating predictions for each data point from only the trees that did not include it in their bootstrap sample, providing an unbiased estimate of model generalization without requiring a separate validation set.

Implementation requires setting key parameters including the number of trees (n_estimators), maximum tree depth (max_depth), and the number of features to consider for each split. The OOB score can be enabled by setting oob_score=True, with the error calculated as 1 - clf.oob_score_ [32]. This feature is particularly valuable for hyperparameter tuning and diagnosing overfitting, especially with limited bioactivity data.

Naïve Bayes

Principle and Application: Naïve Bayes classifiers are probabilistic models based on applying Bayes' theorem with strong feature independence assumptions. Despite this simplifying assumption, they perform remarkably well in chemical informatics tasks, offering rapid training and prediction times along with relative insensitivity to noise [29] [33].

These classifiers are particularly effective for target prediction when integrated with large-scale bioactivity data. For example, a Bernoulli Naïve Bayes algorithm trained on over 195 million bioactivity data points achieved a mean recall and precision of 67.7% and 63.8% for active compounds, and 99.6% and 99.7% for inactive compounds, respectively [29]. The explicit inclusion of inactive data during training produces models with superior early recognition capabilities and area under the curve compared to models trained solely on active data.

Technical Implementation: In the MOST (MOst-Similar ligand-based Target inference) approach, Naïve Bayes was employed alongside other classifiers to predict targets using fingerprint similarity and explicit bioactivity of the most-similar ligands [33]. The probability of a compound being active ((p_a)) is calculated using the algorithm's native method, often incorporating both structural similarity and potency information of known ligands. Studies comparing fingerprint schemes and machine learning methods found that while Naïve Bayes performed well, Logistic Regression and Random Forest methods generally achieved higher accuracy in cross-validation and temporal validation scenarios [33].

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Machine Learning Models in Target Fishing

| Model | Key Strengths | Typical Performance Metrics | Data Requirements | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|