Phenotypic vs Genotypic Resistance Testing: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of phenotypic and genotypic antimicrobial resistance testing methodologies for researchers and drug development professionals.

Phenotypic vs Genotypic Resistance Testing: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of phenotypic and genotypic antimicrobial resistance testing methodologies for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles distinguishing genetic potential from observable resistance, details current and emerging technological platforms, and offers comparative insights on performance validation. By synthesizing foundational concepts with practical applications, troubleshooting guidance, and comparative data, this resource aims to inform strategic decisions in antimicrobial development, surveillance, and diagnostic innovation.

Core Concepts: Defining Phenotypic and Genotypic Resistance

The genotype represents an organism's complete set of genetic material, comprising the specific alleles inherited from both parents that determine the potential for traits and biological functions [1] [2]. In contrast, the phenotype encompasses the observable characteristics—morphological, physiological, and behavioral—that result from the expression of this genetic information as influenced by environmental factors [3] [4]. This distinction, first formally proposed by Wilhelm Johannsen in 1911, remains fundamental to understanding heredity, evolution, and the mechanisms of disease [3] [4].

In antimicrobial resistance (AMR) research, this relationship takes on critical practical significance. Genotypic resistance refers to the presence of specific genetic determinants (e.g., mutations, acquired genes) within a pathogen's genome that confer the potential for resistance [5]. Phenotypic resistance describes the observable ability of a microbial population to survive or multiply despite antibiotic exposure, as determined through laboratory susceptibility testing [5]. The complex interplay between these concepts—where genetic potential does not always translate to observable expression—forms the cornerstone of modern resistance detection strategies and therapeutic decision-making.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Genotype: The Genetic Blueprint

The genotype constitutes the foundational genetic instruction set of an organism. Its composition and key characteristics are detailed below.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Genotype

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Definition | The complete set of genetic material; the specific alleles an organism possesses [1] [2]. |

| Composition | DNA sequences, including protein-coding genes, regulatory sequences, and non-coding DNA [1] [6]. |

| Inheritance | Inherited from both parents, forming the genetic basis passed to offspring [1]. |

| Stability | Generally remains constant throughout life, barring mutations [1]. |

| Determination | Requires genetic testing methods (e.g., DNA sequencing, PCR, microarrays) [1] [2]. |

Genotypes are described using allelic combinations (e.g., AA, Aa, aa for a diploid organism) and can be homozygous (identical alleles) or heterozygous (different alleles) [6] [2]. The relationship between genotype and resultant phenotype is modulated by concepts such as penetrance (the proportion of individuals with a genotype who show the expected phenotype) and expressivity (the range of phenotypic severity among individuals with the same genotype) [6] [2].

Phenotype: The Observable Manifestation

The phenotype represents the physical and functional outcome arising from the interaction between the genotype and the environment.

Table 2: Core Characteristics of Phenotype

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Definition | The observable characteristics or traits of an organism, resulting from its genotype and environmental influences [1] [3]. |

| Composition | Physical attributes (morphology), biochemical properties, physiological processes, and behavior [1] [3]. |

| Inheritance | Not directly inherited; emerges from genotype-environment interaction [1]. |

| Stability | Can change dynamically due to environmental factors, nutrition, climate, and lifestyle [1] [6]. |

| Determination | Assessed through direct observation, measurement, or phenotypic assays [1] [5]. |

A key property of many phenotypes is phenotypic plasticity—the ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in response to distinct environmental conditions [4] [7]. This plasticity is universal across life forms and can be a significant factor in evolution, potentially facilitating adaptation and the origin of novel traits [7].

Comparative Analysis: Genotypic Potential vs. Phenotypic Expression

The relationship between genotype and phenotype is not a simple one-to-one mapping. The following diagram illustrates the conceptual pathway and influencing factors from genetic potential to observable expression.

This complex interaction means that identical genotypes can yield different phenotypes (due to plasticity), and different genotypes can converge on similar phenotypes (due to genetic canalization or convergent evolution) [6] [4]. This has profound implications for predicting outcomes based on genetic information alone.

Application in Antimicrobial Resistance Testing

The genotype-phenotype distinction provides the conceptual framework for the two primary methodologies used in clinical and research laboratories to detect and characterize antimicrobial resistance.

Genotypic Resistance Testing

Genotypic testing identifies the genetic potential for resistance by detecting specific mutations or genes known to be associated with resistance mechanisms [5] [8].

Core Principle: The method involves identifying specific genetic markers—such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions, deletions, or acquired genes (e.g., blaCTX-M, mecA)—within the pathogen's genome that are known to confer resistance [5] [9].

Protocol 1: Genotypic Resistance Testing via PCR and Sequencing

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Isolate total DNA or RNA from a clinical sample (e.g., sputum, blood, urine) or a purified microbial culture. For RNA viruses, extract viral RNA.

- Amplification: For specific targets, use Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) with primers designed to flank the region of interest (e.g., a known resistance gene or mutation hotspot). For broader analysis, use whole-genome sequencing (WGS) approaches.

- Detection/Analysis:

- For Targeted PCR: Analyze amplification products via gel electrophoresis. The presence of a band of the expected size indicates the potential presence of the target gene.

- For Sequencing: Sequence the amplified PCR product or entire genome using next-generation sequencing platforms.

- Interpretation: Compare the generated DNA sequence to a wild-type (susceptible) reference sequence. Differences (mutations) are identified and interpreted using curated databases that link specific genetic changes to predicted resistance phenotypes [8].

Advantages and Limitations:

- Speed: Typically faster than phenotypic methods, yielding results in hours rather than days [9].

- Predictive Power: Can detect resistance potential even before it is expressed at a level detectable by phenotypic assays.

- Limitation: Only detects known mechanisms. A negative result does not rule out the presence of resistance conferred by novel, undetected genetic mechanisms [5]. Furthermore, the presence of a resistance gene does not always lead to its expression, potentially leading to overestimation of resistance.

Phenotypic Resistance Testing

Phenotypic testing directly measures the observable effect of an antimicrobial agent on microbial growth, providing a functional assessment of resistance [5] [10].

Core Principle: This approach exposes a standardized inoculum of the pathogen to a defined concentration of an antimicrobial drug and assesses the inhibition of growth, providing a direct measure of susceptibility [5] [9].

Protocol 2: Phenotypic Susceptibility Testing via Broth Microdilution

- Inoculum Preparation: Adjust the turbidity of a fresh, pure bacterial suspension to a standard density (e.g., 0.5 McFarland standard).

- Plate Preparation: Use a 96-well microtiter plate containing serial two-fold dilutions of various antibiotics in broth medium. This is often commercially prepared.

- Inoculation and Incubation: Dilute the standardized inoculum and add a precise volume to each well of the plate. Incubate under appropriate conditions (e.g., 35°C for 16-20 hours for many bacteria).

- Result Reading: Determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)—the lowest concentration of antibiotic that completely prevents visible growth.

- Interpretation: Compare the MIC to established clinical breakpoints (e.g., from CLSI or EUCAST guidelines) to categorize the organism as Susceptible (S), Intermediate (I), or Resistant (R) [10].

Advantages and Limitations:

- Functional Readout: Directly measures the net effect of all resistance mechanisms present and expressed in the tested isolate, including novel mechanisms.

- Clinical Relevance: Results directly inform therapeutic decisions by indicating which drugs are effective.

- Limitation: The process is slower, typically requiring 18-24 hours or more after a pure culture is obtained [9]. It does not identify the specific genetic mechanism of resistance.

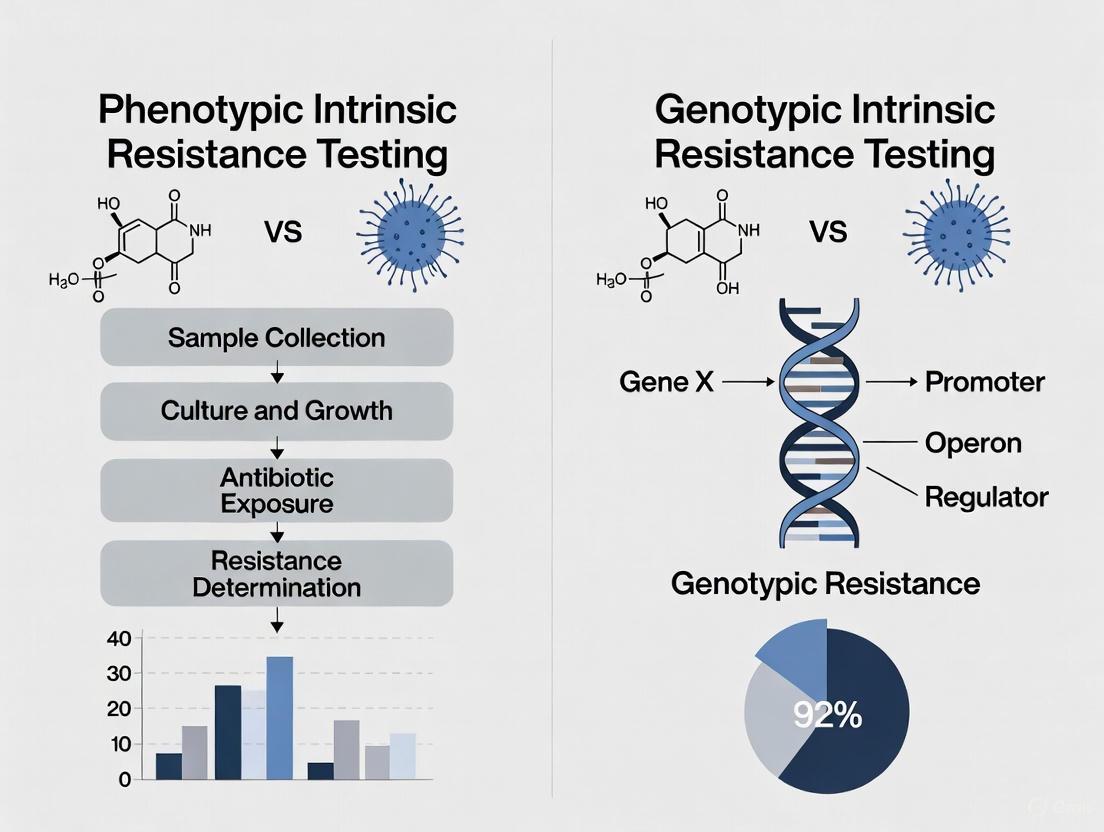

The following workflow summarizes the key steps and decision points in both genotypic and phenotypic testing methods.

Integrated Testing Approaches

Recognizing the complementary strengths and weaknesses of both methods, combined testing approaches are increasingly being adopted. For instance, the PhenoSense GT assay integrates genotypic and phenotypic data into a single report, providing information on both the key resistance mutations and the direct measurement of viral susceptibility to drugs [8]. This synergy offers clinicians the most comprehensive picture for designing effective treatment regimens.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of genotypic and phenotypic resistance studies requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AMR Testing

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| PCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing Taq polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, and MgCl₂ for robust and specific amplification of target DNA sequences in genotypic assays [2]. |

| Broth Microdilution Panels | Pre-manufactured microtiter plates containing lyophilized or liquid serial dilutions of antibiotics. Essential for standardized, high-throughput phenotypic MIC determination [10]. |

| CLSI M100 / EUCAST Standards | Documents providing internationally recognized interpretive criteria (breakpoints) for MIC values and zone diameters, ensuring consistent reporting of Susceptible, Intermediate, and Resistant categories [10]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Kits | Reagent kits for library preparation, target enrichment, and sequencing for comprehensive genotypic analysis, from single genes to whole genomes [2] [9]. |

| Quality Control Strains | Reference microbial strains with well-characterized genotypic and phenotypic resistance profiles. Used to validate the correct performance of both genotypic and phenotypic tests [10]. |

The precise distinction between genotypic potential and phenotypic expression is more than a theoretical concept; it is a practical framework that underpins modern approaches to combating antimicrobial resistance. Genotypic testing offers speed and predictive insight, while phenotypic testing provides a definitive functional assessment of resistance. The future of effective resistance management and personalized anti-infective therapy lies in leveraging the complementary nature of these two paradigms, often through integrated testing strategies. As technologies like whole-genome sequencing and artificial intelligence advance, the ability to more accurately predict phenotypic outcomes from genotypic data will continue to improve, further closing the loop between genetic potential and observable expression [9].

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most significant challenges to modern healthcare, with nearly 700,000 annual global deaths attributed to resistant infections and projections estimating 10 million deaths annually by 2050 if current trends continue [11]. The rise of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens, including Acinetobacter baumannii, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli, threatens to return modern medicine to a pre-antibiotic era where routine infections become untreatable [12] [13]. In this landscape, the speed and accuracy of antimicrobial resistance detection have transitioned from laboratory conveniences to critical determinants of patient survival and clinical outcomes.

The temporal relationship between appropriate antibiotic therapy and patient survival is unequivocal, particularly in bloodstream infections and sepsis, where delays in effective antimicrobial administration are directly associated with increased mortality [14]. Conventional antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) methods typically require 72 hours or more from specimen collection to results, forcing clinicians to rely on empiric therapy that may be ineffective against resistant strains [14]. This diagnostic delay creates a dangerous therapeutic gap during which patients may deteriorate despite broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage.

This application note examines the clinical imperative for rapid resistance detection technologies, framing the discussion within the broader context of phenotypic versus genotypic intrinsic resistance testing research. We present quantitative comparisons of current methodologies, detailed experimental protocols for implementation, and visualization of key pathways and workflows to guide researchers and clinicians in optimizing diagnostic strategies for improved patient outcomes.

Phenotypic vs. Genotypic Detection Methods: A Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Principles and Clinical Applications

Phenotypic and genotypic resistance detection methods operate on fundamentally different principles, each with distinct advantages and limitations in clinical practice. Phenotypic methods directly measure microbial growth or viability in the presence of antimicrobials, providing a functional assessment of resistance regardless of the underlying mechanism. These methods include disk diffusion, broth microdilution for minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination, and novel rapid phenotypic technologies [14]. In contrast, genotypic methods detect specific genetic determinants of resistance, including resistance genes (e.g., bla-NDM, bla-OXA-48), point mutations (e.g., in gyrA, gyrB, parC), and gene overexpression mechanisms [12] [15] [11].

The clinical value of each approach depends heavily on context. Phenotypic methods remain the gold standard for therapy guidance as they directly measure the interaction between pathogen and drug [11]. However, genotypic methods offer significant speed advantages, potentially providing results within hours rather than days, which is crucial for timely therapeutic adjustments [12] [16]. Recent advances in rapid phenotypic technologies are bridging this temporal gap, with numerous platforms in development that promise phenotypic results in significantly reduced timeframes [14].

Quantitative Comparison of Method Performance

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Phenotypic and Genotypic Detection Methods for Key Pathogens

| Pathogen | Phenotypic Detection Range | Genotypic Detection Rate | Key Resistance Mechanisms | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter baumannii (n=104) | 36.54%-89.42% [12] | 60% (56/93 isolates) [12] | OXA-48, NDM, VIM genes [12] | Life-threatening infections in critically ill patients [12] |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae (n=121) | Not assessed | 47.9% macrolide resistance mutations [16] [13] | 23S rRNA gene mutations [13] | 2.20x higher macrolide use (aOR); 0.41x lower tetracycline use (aOR) with rapid testing [16] |

| Pasteurella multocida (n=80) | High susceptibility to cephalosporins, phenicols (>90%); high resistance to clindamycin, sulfamethoxazole [11] | strA, sul2, tetH most prevalent; no bla-TEM or erm(42) [11] | SNPs in gyrA (Ser83Ile, Ser83Arg, Asp87Asn) [11] | Strong correlation for phenicols, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones; unexplained resistance to sulfamethoxazole, β-lactams [11] |

| Escherichia coli | Hypersensitivity to trimethoprim in knockout strains (ΔacrB, ΔrfaG, ΔlpxM) [15] | Efflux pump (acrB) and cell envelope (rfaG, lpxM) genes identified [15] | Efflux pumps, cell envelope biogenesis, LPS synthesis [15] | Targeting intrinsic resistance pathways sensitizes bacteria and limits resistance evolution [15] |

Correlation Between Methodologies

The relationship between phenotypic and genotypic resistance profiles varies significantly across pathogen-antibiotic combinations. For Pasteurella multocida, phenotypic results for phenicols, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones showed strong correlation with detected resistance genes, while resistance to sulfamethoxazole, β-lactams, and macrolides remained genetically unexplained, suggesting unidentified resistance mechanisms [11]. Similarly, in Acinetobacter baumannii, phenotypic methods demonstrated wider detection ranges (36.54%-89.42%) compared to genotypic methods (60%), indicating either superior sensitivity of phenotypic methods or limitations in current genetic target panels [12].

The broth microdilution method for MIC determination consistently shows stronger correlation with genotypic results compared to disk diffusion, making it more reliable for susceptibility testing despite being more resource-intensive [11]. This enhanced correlation likely reflects the quantitative nature of MIC data compared to the qualitative zone diameter measurements of disk diffusion.

The Impact of Rapid Testing on Clinical Decision-Making

Therapeutic Optimization and Antimicrobial Stewardship

Rapid resistance detection technologies directly influence antimicrobial prescribing patterns and stewardship outcomes. A retrospective study of 298 pediatric patients with Mycoplasma pneumoniae demonstrated that implementation of the Smart Gene Myco point-of-care test, which detects macrolide-resistance gene mutations, was associated with a 2.20-fold higher appropriate macrolide use (adjusted odds ratio) and a 0.41-fold lower tetracycline use (aOR) [16] [13]. This represents a significant optimization of antimicrobial selection based on rapid genotypic results, ensuring patients receive effective therapy while avoiding unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotics.

The clinical value of rapid testing extends beyond initial therapy selection to encompass de-escalation strategies. Rapid exclusion of resistance mechanisms enables clinicians to confidently narrow antibiotic spectra, reducing collateral damage to commensal microbiota and selective pressure for resistance development [14]. This is particularly valuable in critical care settings, where inappropriate initial antibiotic therapy increases mortality risk by 2- to 3-fold in patients with bloodstream infections [14].

Temporal Advantages in Clinical Workflows

Table 2: Turnaround Time Comparison of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Methods

| Testing Method | Time from Specimen Collection to Result | Time from Pure Colony to Result | Regulatory Status | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Phenotypic | ≥72 hours [14] | 4-24 hours [14] | Gold standard | Comprehensive, hypothesis-free |

| Rapid Phenotypic Technologies | Significantly faster than conventional [14] | <4 hours [14] | 12 with FDA 510(k)+CE; 6 with CE only [14] | Functional assessment, faster results |

| Genotypic Methods | Hours (post-culture) [12] | 2-8 hours [12] | Varies by platform | Rapid results, high specificity |

| Point-of-Care Genotypic | Potentially same-day [16] | <2 hours [16] | Emerging technologies | Bedside testing, immediate intervention |

The temporal advantage of rapid testing methodologies becomes clinically significant when considering the relationship between appropriate antibiotic therapy and patient survival. Studies consistently demonstrate that each hour of delay in effective antimicrobial administration increases mortality in septic patients by 7-10% [14]. Next-generation rapid phenotypic AST technologies can reduce total turnaround time from specimen collection to results through a combination of innovations, including direct specimen testing, reduced incubation periods, and accelerated detection methods [14].

Experimental Protocols for Resistance Detection

Protocol 1: Phenotypic Metallo-β-Lactamase Detection in Acinetobacter baumannii

Principle: This protocol detects MBL production in A. baumannii using both double-disk synergy tests and the MBL-E test, followed by confirmation with genotypic methods [12].

Materials:

- Mueller-Hinton agar plates

- Antibiotic disks: imipenem, meropenem, EDTA-containing disks

- MBL-E test strips or solutions

- Bacterial isolates (pure culture)

- PCR reagents for OXA-48, NDM, VIM gene detection

Procedure:

- Prepare 0.5 McFarland standard bacterial suspensions from fresh pure colonies.

- Lawn the suspensions onto Mueller-Hinton agar plates and allow to dry.

- For double-disk synergy test: Place imipenem and meropenem disks 20mm from EDTA-containing disks. Incubate at 35°C for 16-18 hours.

- For MBL-E test: Apply test strips or solutions according to manufacturer instructions. Incubate and observe for enhancement zones.

- Interpretation: Positive result indicated by ≥5mm increase in zone diameter between carbapenem and EDTA disks, or positive color change/zone in MBL-E test.

- Confirm positive phenotypes with PCR for OXA-48, NDM, and VIM genes.

Technical Notes: Among 93 drug-resistant A. baumannii isolates, phenotypic methods showed a detection range of 36.54%-89.42% compared to 60% with molecular methods [12]. Store antibiotic disks at -20°C until use. Include positive and negative controls in each batch.

Protocol 2: Genotypic Macrolide Resistance Detection in Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Principle: This protocol utilizes the Smart Gene Myco point-of-care testing platform to detect 23S rRNA gene mutations conferring macrolide resistance in M. pneumoniae [16] [13].

Materials:

- Smart Gene Myco test platform and reagents

- Nasopharyngeal swabs or respiratory specimens

- Nucleic acid extraction kit

- Positive and negative control samples

- Microcentrifuge and vortex mixer

Procedure:

- Extract nucleic acids from clinical specimens according to manufacturer instructions.

- Prepare reaction mixtures containing extracted nucleic acids, amplification reagents, and detection probes.

- Load samples into the Smart Gene Myco platform and initiate testing protocol.

- The system automatically performs nucleic acid amplification and detection of resistance mutations.

- Interpretation: Results indicate presence or absence of macrolide-resistance mutations in 23S rRNA gene.

- Report results to clinicians within 2 hours of specimen receipt.

Technical Notes: In clinical implementation, this test detected macrolide resistance mutations in 47.9% of pediatric patients, enabling more targeted antibiotic selection [16]. Ensure proper specimen collection and transport to maintain nucleic acid integrity.

Protocol 3: WHONET and R Software for AMR Surveillance

Principle: This protocol outlines a standardized approach for antimicrobial resistance surveillance using WHONET and R software for data analysis and visualization [17].

Materials:

- WHONET software (v.25.04.25)

- BacLink software (v.25.04.25)

- R software (v.4.4.0) with RStudio

- Microbiology laboratory data in compatible format (.csv, .txt, or laboratory-specific formats)

Procedure:

- Data Extraction: Export laboratory data including isolate identification, specimen type, collection date, and antibiogram results.

- Data Import with BacLink: Use BacLink to transform laboratory-native file formats into WHONET-compatible format.

- WHONET Configuration: Set up laboratory configuration in WHONET, including organism codes, antibiotic panels, and interpretation criteria (e.g., EUCAST guidelines).

- Data Analysis in WHONET: Generate resistance reports stratified by time period, pathogen, specimen type, or ward location.

- Data Export to R: Export aggregated resistance data from WHONET for advanced statistical analysis and visualization in R.

- Trend Analysis in R: Use R scripts to perform regression analysis of resistance trends over time and generate publication-ready figures.

Technical Notes: This standardized workflow enables reproducible AMR trend analysis with minimal resources, particularly valuable in low-resource settings [17]. The software tools are freely available, reducing economic barriers to implementation.

Visualization of Key Concepts and Workflows

Diagnostic Pathway for Antimicrobial Resistance Testing

Diagram 1: Diagnostic Pathway for Antimicrobial Resistance Testing. This workflow illustrates the parallel phenotypic and genotypic testing pathways from specimen collection to therapeutic decision-making, highlighting critical timepoints that impact patient outcomes.

Intrinsic Resistance Pathways in Escherichia coli

Diagram 2: Intrinsic Resistance Pathways in Escherichia coli. This diagram illustrates key intrinsic resistance mechanisms in E. coli, including efflux pumps and membrane barriers, and demonstrates how targeting these pathways can sensitize bacteria to antibiotics and reduce treatment failure risk [15].

Research Reagent Solutions for Resistance Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Antimicrobial Resistance Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Mueller-Hinton Agar, Blood Culture Bottles | Supports bacterial growth for phenotypic testing | Quality control essential for reproducible results [12] |

| Antibiotic Disks/Panels | EUCAST-approved disks, Broth microdilution panels | Determinination of susceptibility profiles (MIC, zone diameters) | Store according to manufacturer specifications [11] |

| Molecular Detection Kits | Smart Gene Myco, PCR reagents for resistance genes | Detection of specific resistance mechanisms | Enables rapid, targeted resistance detection [16] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Library prep kits, BV-BRC, CARD database | Comprehensive resistance gene identification | Identifies known and novel resistance determinants [11] |

| Software Tools | WHONET, R with specialized packages | AMR surveillance data management and analysis | Enables trend analysis and resistance pattern identification [17] |

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors | Chlorpromazine, Piperine, Verapamil | Study of efflux-mediated resistance mechanisms | Demonstrates proof-of-concept for resistance breaking [15] |

The clinical imperative for rapid antimicrobial resistance detection is unequivocally established, with demonstrated impacts on mortality, antimicrobial stewardship, and healthcare costs. The complementary strengths of phenotypic and genotypic methods create a powerful synergistic relationship when integrated into diagnostic pathways. Phenotypic methods provide functional assessment of resistance across all possible mechanisms, while genotypic methods offer rapid results for targeted therapeutic adjustments.

Future directions in resistance detection will likely focus on technologies that combine the comprehensive nature of phenotypic assessment with the speed of genotypic methods. Next-generation rapid phenotypic platforms currently in development promise to bridge this temporal gap, potentially revolutionizing antimicrobial stewardship programs [14]. Additionally, the strategic targeting of intrinsic resistance pathways, such as efflux pumps and membrane barrier systems, represents a promising approach for resensitizing resistant pathogens to existing antibiotics [15].

Implementation of the protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note requires multidisciplinary collaboration between clinical microbiologists, infectious disease physicians, data scientists, and antimicrobial stewardship teams. Through systematic adoption of rapid, accurate resistance detection technologies and surveillance systems, healthcare institutions can significantly impact patient outcomes while combating the global threat of antimicrobial resistance.

The escalation of antimicrobial and chemotherapeutic resistance represents a critical challenge in both clinical medicine and drug development. Resistance can be categorized into two fundamental concepts: genotypic resistance, which refers to the presence of specific genetic determinants that confer resistance potential (e.g., mutations in drug targets or acquired resistance genes), and phenotypic resistance, which describes the observable ability of a microbial or cancer cell population to survive and multiply despite therapeutic intervention [5]. These concepts are not mutually exclusive; rather, they represent different facets of the resistance spectrum. While genotypic testing reveals inherent resistance potential, phenotypic testing directly measures functional survival outcomes, providing the cornerstone for determining appropriate therapeutic strategies [5].

Understanding the mechanisms that bridge genetic mutations to functional survival is paramount for developing novel diagnostic tools and therapeutic interventions. This application note explores the quantitative methodologies and experimental protocols essential for delineating these mechanisms, providing researchers with structured frameworks to advance resistance testing in both microbiological and oncological research contexts within the broader scope of phenotypic versus genotypic intrinsic resistance investigations.

Quantitative Methodologies for Resistance Assessment

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Testing and Analysis

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) test serves as a fundamental phenotypic assay for quantifying resistance levels in microbial isolates. The MIC defines the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent that inhibits visible growth of a microorganism [18]. These tests produce data points that fall within a range of concentrations rather than representing exact values, resulting in a data structure known as censoring. Proper analysis requires recognition of three censoring types: left-censoring (inhibition at all dilutions), right-censoring (no inhibition at highest concentration), and interval-censoring (inhibition between two concentrations) [18].

Table 1: Censoring Types in MIC Data Analysis

| Censoring Type | Description | Report Format |

|---|---|---|

| Left-Censored | Observation known only to be below the lowest concentration tested | ≤J μg/mL (where J is the lowest concentration) |

| Right-Censored | Observation known only to be above the highest concentration tested | >J μg/mL (where J is the highest concentration) |

| Interval-Censored | Observation known to lie between two concentration values | True MIC lies between reported MIC and one step below on two-fold scale |

For analytical purposes, MIC data can be categorized using established breakpoints. Epidemiological cutoff values (ECOFFs) separate wild-type (WT) isolates lacking acquired resistance mechanisms from non-wild-type (non-WT) organisms possessing detectable resistance mechanisms [18]. Alternatively, clinical breakpoints partition MIC values into susceptibility categories ("susceptible," "intermediate," and "resistant") based on clinical outcome data [18]. The choice between these categorization methods depends on the research objective, with ECOFFs更适合 for tracking resistance emergence and clinical breakpoints更适合 for predicting therapeutic efficacy.

Advanced Statistical Approaches for MIC Data

Analysis of MIC data requires specialized statistical approaches that account for censoring. Logistic regression models are widely employed but require dichotomization of the continuous MIC distribution, potentially losing information about shifts within susceptibility categories [18]. Cumulative logistic regression can accommodate multiple ordered categories (susceptible, intermediate, resistant) without presuming equal spacing between categories. For more sophisticated analyses, accelerated failure time-frailty models and mixture models preserve the interval-censored nature of MIC data, providing enhanced detection of subtle changes in MIC distributions that might be missed when data is categorized [18]. Model selection should consider the study objective, degree of censoring in the data, and consistency of testing parameters across experiments.

Experimental Protocols for Resistance Mechanism Investigation

Protocol for Assessing Resistance Development Risk to Microbicides

This protocol, adapted from research on microbicide resistance, provides a framework for evaluating the risk of resistance development following exposure to antimicrobial compounds [19]. The approach measures changes in microbicide and antibiotic susceptibility as primary markers for resistance emergence.

Table 2: Protocol for Microbicide Resistance Risk Assessment

| Step | Procedure | Key Parameters | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Strain Selection | Select target organisms including reference strains and industrial isolates | Include Gram-positive and Gram-negative species; restrict to maximum 2 subcultures from original stock | Diverse panel of test organisms |

| 2. Baseline Assessment | Determine pre-exposure MIC and MBC for formulations and active ingredients | Use doubling dilutions in culture medium; incubate 24h at 37°C | Baseline susceptibility profile |

| 3. Controlled Exposure | Expose strains to product formulations at concentrations yielding 1-3 log₁₀ reduction | Follow standardized suspension testing (e.g., BS EN 1276:2009); 1min exposure time | Surviving population for further testing |

| 4. Post-Exposure Assessment | Determine MIC and MBC of formulations and active ingredients after exposure | Same methodology as baseline assessment | Post-exposure susceptibility profile |

| 5. Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiling | Test baseline and post-exposure populations against panel of clinically relevant antibiotics | Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion or MIC determination | Changes in antibiotic susceptibility patterns |

| 6. Phenotype Stability Testing | Passage exposed populations without selective pressure | 5-10 passages in non-selective medium; reassay susceptibility | Stability of resistance phenotype |

This integrated protocol generates reproducible data for initial prediction of resistance development risk, employing cost-effective, high-throughput techniques that allow manufacturers to efficiently provide regulatory bodies with safety assessment data [19]. The methodology can be adapted for various antimicrobial agents beyond microbicides.

Dose-Escalation Protocol for Studying Chemotherapy Resistance

Investigations into irinotecan resistance in cancer cells demonstrate the importance of dose-escalation protocols for studying resistance evolution. The following methodology outlines key steps for observing adaptive resistance development:

Cell Line and Culture Conditions:

- Use cloned cancer cell lines (e.g., HCT116 colon cancer cells) to ensure genetic uniformity

- Isolate multiple independent single-cell clones (SCCs) to account for clonal variation

- For irinotecan studies, use activated derivative SN-38 due to inefficient activation in cell culture [20]

Dose-Escalation Treatment Scheme:

- Begin with initial exposure at IC₅₀ concentration (e.g., 4nM SN-38 for sensitive clones)

- Monitor cells for death and senescence-like growth arrest (typically 14 days initially)

- Resume growth when cells recover from arrest

- Repeat treatment cycle with same concentration (observe shorter arrest periods with each cycle)

- After adaptation to initial concentration, escalate dose (e.g., to 40nM) and repeat process

- Continue through multiple cycles (3-5) until cells demonstrate stable resistance [20]

Phenotypic Monitoring:

- Document duration of growth arrest following each exposure

- Quantify fraction of cell death after each treatment

- Assess morphological changes (enlargement, vacuolization indicative of senescence)

- Use cell cycle reporters to track arrest and re-entry into cell cycle [20]

Barcoding for Clonal Tracking:

- Implement cellular barcoding (e.g., Cellecta 50M barcodes lentiviral library) prior to selection

- Compare barcode frequencies pre- and post-selection to quantify clonal survival

- Assess difference between dose-escalation versus direct high-dose selection [20]

This approach demonstrates that dose escalation significantly enhances resistant variant development compared to direct high-dose exposure, with barcode analysis revealing 100-fold higher survival with escalation protocols [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Resistance Mechanism Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Specification | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| HCT116 Colon Cancer Cells | Single-cell cloned populations | Irinotecan resistance studies; ensure genetic uniformity for adaptation experiments [20] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis Strains | Multiple lineage representatives (Lineages 1-4) | GWAS of drug resistance mechanisms; lineage-specific resistance propensity [21] |

| Cellecta 50M Barcodes Lentiviral Library | Complexity: 50 million unique barcodes | Clonal tracking in resistance evolution studies; quantifies population dynamics [20] |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium | Strains SL1344 and 14028S | Microbicide resistance profiling; Gram-negative model for susceptibility testing [19] |

| Cell Cycle Reporter Systems | Fluorescent cell cycle indicators | Monitoring growth arrest and recovery in therapy resistance; distinguishes senescence from proliferation [20] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Kits | Short-read and long-read technologies | Identification of resistance mutations; plasmid-encoded resistance gene detection [22] |

Signaling Pathways and Resistance Mechanisms

DNA Repair-Mediated Resistance in Chemotherapy

This diagram illustrates the mechanism of resistance development to Top1 inhibitors like irinotecan. Cancer cells initially sensitive to Top1 inhibitors due to increased cleavage sites gradually develop resistance through homology-directed repair of double-strand breaks, which reverts cleavage-sensitive "cancer" sequences back to cleavage-resistant "normal" sequences [20]. These mutations reduce DNA break generation upon subsequent exposures, leading to progressively increased drug resistance through dose escalation protocols.

DNA Repair Pathway Mutations in Antimicrobial Resistance

Genome-wide association studies of Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates have identified novel mutations in DNA repair genes (MutY, UvrA, UvrB, RecF) strongly associated with multidrug-resistant phenotypes [21]. These mutations collectively compromise DNA repair functions but paradoxically contribute to better bacterial survival under antibiotic and host stress conditions, facilitating the evolution of drug resistance through enhanced mutation rates or alternative survival pathways.

The intricate relationship between genetic mutations and functional survival outcomes underscores the complexity of resistance mechanisms across biological systems. The experimental frameworks and quantitative methodologies presented in this application note provide researchers with robust tools for dissecting these mechanisms, bridging the gap between genotypic prediction and phenotypic expression. As resistance continues to evolve, integrating these approaches within a comprehensive research strategy will be essential for developing next-generation diagnostics and therapeutics capable of overcoming adaptive survival mechanisms in both infectious diseases and oncology.

Within the framework of phenotypic versus genotypic intrinsic resistance research, a meticulously validated testing workflow is paramount. This protocol details the integrated application of phenotypic and genotypic methods to characterize intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms in bacteria. The strategic combination of these approaches provides a comprehensive resistance profile, bridging the gap between observable resistance phenotypes and their underlying genetic determinants [23] [22]. This is particularly critical for pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis and multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales, where delayed or inaccurate susceptibility results can directly impact patient outcomes and facilitate the spread of resistance [23] [24]. The following sections provide a detailed, actionable pathway from specimen collection to final analysis, enabling researchers to obtain reliable, actionable data for informing therapeutic strategies and surveillance programs.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following toolkit comprises essential reagents and kits for executing the resistance testing workflow.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Kits

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Löwenstein–Jensen (L-J) Medium [23] | Solid culture medium for phenotypic DST of M. tuberculosis | Requires 28-35 days for results; considered a reference standard |

| BACTEC MGIT 960 System [23] | Automated liquid culture for rapid phenotypic DST | Average time to result: 7.5 ± 1.8 days |

| GenoType MTBDRplus Assay [23] | Line Probe Assay for genotypic detection of RIF and INH resistance | Detects mutations in rpoB (RIF) and katG/inhA (INH) |

| Anaerobic Transport Medium (ATM) [25] | Preserves viability of obligate anaerobes during transport | Specially designed to exclude oxygen; critical for abscess aspirates |

| Copan eSwab [25] | Collection swab for aerobic culture | Used for MRSA surveillance; non-inhibitory to anaerobic bacteria |

| DeepChek Assay & Software [26] | Targeted amplicon sequencing and bioinformatic analysis | Compatible with multiple NGS platforms for resistance mutation detection |

Methods

Specimen Collection and Transport

Proper specimen collection is the critical first step that determines the validity of all subsequent results.

- Site Selection and Sampling: Collect specimens from the primary site of infection, avoiding contamination with normal flora where possible [25]. For anaerobic cultures (e.g., from deep abscesses), obtain tissue biopsies or needle aspirates. Swabs are not acceptable for anaerobic culture due to poor recovery and potential for contamination [25].

- Choice of Collection Device:

- Transport: Label all specimens accurately. Transport to the laboratory promptly at room temperature (for anaerobic specimens) to preserve bacterial viability. Specimens in ATM should be processed within 24 hours of collection [25].

Phenotypic Drug Susceptibility Testing (DST)

This method determines resistance by observing bacterial growth in the presence of antibiotics.

Table 2: Phenotypic Drug Susceptibility Testing Methods

| Method | Principle | Time to Result | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Löwenstein-Jensen (L-J) Solid Medium [23] | Growth of M. tuberculosis on antibiotic-containing solid medium | 28-35 days | Gold standard for first- and second-line TB DST |

| Liquid Culture (e.g., BACTEC MGIT 960) [23] | Automated detection of CO~2~ production by growing mycobacteria in liquid medium with antibiotics | ~7.5 days | Rapid phenotypic DST for M. tuberculosis |

| Broth Microdilution (MIC/MBC) [19] | Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) in a 96-well plate | 24 hours | Quantifying resistance levels; assessing cross-resistance risk |

Detailed Protocol: Broth Microdilution for MIC/MBC [19]

- Inoculum Preparation: Harvest an overnight broth culture by centrifugation. Resuspend the bacterial pellet in deionized water and standardize the suspension to 1 × 10^8^ CFU/mL.

- Plate Preparation: Prepare doubling dilutions of the antibiotic or microbicide of interest in a 96-well microtiter plate containing growth broth (e.g., Tryptone Soya Broth).

- Inoculation and Incubation: Add a standardized volume (e.g., 50 µL) of the bacterial inoculum to each well. Incub the plate at 37°C for 24 hours.

- MIC Determination: The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) is defined as the lowest concentration of antimicrobial agent that completely inhibits visible growth.

- MBC Determination: Subculture broth from wells showing no growth onto antibiotic-free solid agar medium. The Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) is the lowest concentration that results in a ≥99.9% reduction in the original bacterial inoculum.

Genotypic Drug Resistance Detection

These methods identify resistance by detecting specific genetic mutations known to confer resistance.

3.3.1 Line Probe Assay (e.g., GenoType MTBDRplus) [23]

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from a pure bacterial culture or directly from a clinical specimen.

- Amplification: Perform a multiplex PCR using biotinylated primers to amplify resistance-associated regions (e.g., rpoB for RIF, katG and inhA for INH).

- Hybridization and Detection: Denature the PCR products and hybridize them to membrane-bound probes. Subsequent enzymatic reaction produces a visible banding pattern.

- Interpretation: The presence or absence of specific wild-type and mutation bands determines the genotypic resistance profile.

3.3.2 Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for Resistance Profiling [26]

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract high-quality genomic DNA or RNA from the sample.

- Library Preparation:

- Amplification: Use targeted primer sets (e.g., DeepChek Assays) to generate amplicons covering key drug resistance-associated genes.

- Fragmentation and Adapter Ligation: Fragment the amplicons enzymatically, then ligate platform-specific sequencing adapters.

- Quality Control: Verify library quality and quantity using a fragment analyzer (e.g., Agilent TapeStation) and fluorometry (e.g., Qubit).

- Sequencing: Load the library onto an NGS platform (e.g., Illumina ISeq100, Oxford Nanopore MinION). This protocol is compatible with multiple short- and long-read technologies [26].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process the raw sequencing data using specialized software (e.g., DeepChek). The workflow includes:

- Read trimming and alignment to a reference genome.

- Variant calling to identify mutations.

- Interpretation of mutations against a curated database of known resistance markers.

Diagram 1: Integrated resistance testing workflow showing parallel phenotypic and genotypic pathways.

Results and Data Interpretation

Concordance and Discordance Between Methods

The integration of phenotypic and genotypic data is where true actionable insight is generated.

Table 3: Example Concordance Between Genotypic and Phenotypic DST for M. tuberculosis (n=66 Isolates) [23]

| Drug | Phenotypic Resistance Rate (%) | Overall Concordance with Genotype MTBDRplus (%) | Notes on Discordance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isoniazid (INH) | 84.85% | 95.16% | 2 cases: Genotypically susceptible but phenotypically resistant |

| Rifampicin (RIF) | 46.97% | 94.74% | 3 cases: Genotypically susceptible but phenotypically resistant |

| Streptomycin (STR) | 48.48% | Not specified | - |

| Ethambutol (EMB) | 30.30% | Not specified | - |

Interpreting Complex Results

- Actionable Result from Concordance: A genotype positive for a canonical rpoB mutation (e.g., S531L) and a corresponding resistant phenotype confirms MDR-TB, enabling immediate initiation of a second-line treatment regimen [23].

- Investigating Discordance: Isolates that are genotypically susceptible but phenotypically resistant (as noted in Table 3) suggest the presence of resistance mechanisms not detected by the genotypic assay (e.g., mutations in novel genes, efflux pump overexpression) [23] [24]. In such cases, the phenotypic result should take precedence for clinical decision-making, while further investigation via whole-genome sequencing is recommended for research.

- Beyond M. tuberculosis: The same principles apply to other pathogens. For example, in E. coli, intrinsic resistance mechanisms like efflux pumps (AcrB) and cell envelope integrity (LpxM, RfaG) are key regulators of susceptibility to diverse drug classes. Genotypic identification of such pathways can explain baseline phenotypic resistance and reveal targets for resistance-breaking adjuvants [24].

Diagram 2: Logic flow for integrating phenotypic and genotypic data to confirm a resistance mechanism.

This detailed protocol outlines a robust framework for moving from a clinical specimen to an actionable resistance profile. The synergistic use of phenotypic and genotypic methods compensates for the limitations inherent in each approach when used in isolation. Phenotypic testing provides a biologically relevant readout of resistance but is slow, while genotypic methods offer speed and precision but may miss novel or complex mechanisms [23] [27]. Adhering to this integrated workflow ensures that results are both timely and comprehensive, providing a solid foundation for effective patient management, antimicrobial stewardship, and ongoing resistance surveillance research.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a growing threat to global health, undermining the effectiveness of life-saving treatments and placing populations at heightened risk from common infections and routine medical interventions [28]. The World Health Organization's 2025 Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) report provides a stark quantification of this burden, drawing on more than 23 million bacteriologically confirmed cases of bloodstream infections, urinary tract infections, gastrointestinal infections, and urogenital gonorrhoea from 110 countries [28]. This extensive data collection enables adjusted global and regional estimates of AMR for 93 infection type–pathogen–antibiotic combinations, providing researchers and public health officials with critical evidence to guide intervention strategies [28].

The clinical challenge is particularly acute with multidrug-resistant pathogens like Acinetobacter baumannii, a common cause of nosocomial infections. Recent studies reveal that 89.4% of A. baumannii isolates demonstrate drug resistance, creating life-threatening therapeutic challenges, especially in critically ill and vulnerable patients [12]. This resistance is conferred through various mechanisms, including metallo-beta-lactamase (MBL) production detected in up to 60% of isolates via molecular methods [12]. The relentless evolution of resistant pathogens has created an urgent need for innovative diagnostic approaches that can rapidly guide targeted antimicrobial therapy, preserving the efficacy of existing treatments while curbing unnecessary antimicrobial use.

The Diagnostic Innovation Imperative

The slow progress toward implementing conventional clinical bacteriology in low-resource settings, coupled with the universal need for greater speed in antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST), has focused attention on next-generation rapid technologies [14]. Conventional AST workflows for bloodstream infections typically require a minimum of 72 hours from specimen collection to final susceptibility results, creating dangerous delays in appropriate antimicrobial administration [14]. This diagnostic gap fuels the overuse of empiric antimicrobials, further driving AMR emergence and spread.

The innovation imperative is particularly pressing in low-resource settings, where only approximately 1.3% of 50,000 medical laboratories in 14 sub-Saharan African countries offered any clinical bacteriology testing as of 2019 [14]. Barriers to conventional bacteriology implementation include requirements for specialized infrastructure, lack of automation, inadequate local access to complex supply chains, and human resource challenges [14]. Next-generation rapid phenotypic AST technologies promise to bridge this diagnostic gap by providing accurate susceptibility profiles within clinically relevant timeframes, potentially revolutionizing antimicrobial stewardship across diverse healthcare settings.

The Phenotypic vs. Genotypic Testing Paradigm

The debate between phenotypic and genotypic approaches for antimicrobial resistance detection represents a central frontier in diagnostic research. Phenotypic tests measure microbial growth or viability in the presence of antimicrobials to determine susceptibility, providing a functional assessment of resistance regardless of the underlying mechanism [14]. In contrast, genotypic methods detect specific resistance genes but may miss novel or unexpected resistance mechanisms.

Recent comparative studies highlight the complementary value of both approaches. A 2025 study comparing phenotypic and genotypic detection of drug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii found that while molecular detection of drug-resistance conferring genes can be more time-effective, phenotypic methods provided valuable functional validation [12]. The researchers concluded that additional research is needed to develop comprehensive testing panels that integrate both approaches, as each provides distinct but complementary information about resistance profiles [12].

Table 1: Comparison of Phenotypic and Genotypic AMR Detection Methods

| Feature | Phenotypic Methods | Genotypic Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Detection | Microbial growth/viability in presence of antimicrobials | Detection of specific resistance genes |

| Time to Result | Traditionally 16-24 hours (conventional); newer rapid methods <8 hours | Typically 2-4 hours |

| Mechanism Coverage | Detects all resistance mechanisms regardless of genetic basis | Limited to known, targeted resistance genes |

| Clinical Correlation | Direct functional assessment | Indirect prediction based on gene presence |

| Example from Literature | MBL-E test, double-disk synergy test [12] | Molecular detection of OXA-48, NDM, VIM genes [12] |

Emerging Technologies in Rapid Phenotypic AST

A comprehensive review published in Nature Communications in 2024 synthesized the landscape of next-generation rapid phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing, identifying over 90 distinct technologies at various development stages [14]. This analysis characterized technologies in terms of underlying technical innovations, technology readiness level (TRL), extent of clinical validation, and time-to-results from specimen collection. The review categorized technologies as commercialized (18 platforms, with 12 having FDA 510(k) clearance and CE marking) and non-commercialized (81 publications describing 67 phenotypic and 14 hypothesis-free nucleic acid-based platforms) [14].

These innovations employ diverse strategies to accelerate susceptibility testing, including:

- Direct specimen testing to eliminate culture steps

- Enhanced detection methods for early growth indication

- Microfluidic platforms for single-cell analysis

- Morphological changes detection using microscopy and AI

- Hypothesis-free nucleic acid-based tests using genomic recognition elements to detect or quantify bacteria in the presence of different antimicrobial conditions without pre-defined targets [14]

The standardized assessment of turnaround time from specimen collection revealed that many emerging technologies can provide reliable AST results within 8-24 hours compared to the conventional 72-hour workflow, representing a potentially practice-transforming advancement for clinical management of serious infections [14].

Case Study: Marple Rapid Diagnostic Tool

An exemplar of innovation targeting appropriate antimicrobial use is the Marple lateral flow device and smartphone app, currently in prototype phase and undergoing evaluation through a project led by Professor Jethro Herberg at Imperial College London with partners in The Gambia [29]. This test addresses the critical challenge of distinguishing between bacterial and viral respiratory infections using five immune response biomarkers identified through previous research [29].

Key features of this diagnostic tool include:

- Rapid results within 10 minutes

- Low production cost and minimal infrastructure requirements

- Smartphone app integration for algorithmic interpretation

- Pilot testing in both NHS and Gambian settings [29]

Professor Herberg emphasizes the potential impact: "A major driver of antimicrobial resistance is the unnecessary use of antibiotics in those who don't need them. By accurately finding out who has a bacterial infection and viral infection, we can ensure we only use antibiotics in those patients who need them" [29]. This project, funded by the £30 million PACE (Pathways to Antimicrobial Clinical Efficacy) initiative, represents the translation of 15 years of foundational research into a practical diagnostic solution with potential for global impact [29].

Table 2: Global AMR Surveillance Data and Response Initiatives

| Surveillance Metric | Reported Data | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| GLASS Data Volume | 23+ million bacteriologically confirmed cases [28] | Unprecedented scale of global AMR monitoring |

| Country Participation | 110 countries (2016-2023) [28] | Expanding global coordination in AMR surveillance |

| A. baumannii Drug Resistance | 89.4% of isolates (n=104) [12] | Highlights specific challenges with nosocomial pathogens |

| PACE Initiative Funding | £30 million [29] | Substantial investment in early-stage AMR innovation |

| EUP OHAMR Call Budget | €31+ million for 2026 [30] | Major transnational commitment to AMR research |

Experimental Protocols for AMR Detection

Protocol 1: Phenotypic Metallo-β-Lactamase Detection

Principle: This protocol detects metallo-β-lactamase (MBL) production in Gram-negative bacteria like Acinetobacter baumannii using a combination of double-disk synergy test, modified Hodge test, and MBL-E test [12].

Materials:

- Mueller-Hinton agar plates

- Imipenem and meropenem disks

- EDTA solution for MBL-E test

- Bacterial isolates (pure cultures)

- Incubator set at 35±2°C

Procedure:

- Prepare a 0.5 McFarland standard suspension of the test isolate in sterile saline.

- Lawn the suspension evenly onto Mueller-Hinton agar plates and allow to dry.

- For double-disk synergy test: Place an imipenem disk and EDTA-impregnated disk 15mm apart center-to-center.

- For MBL-E test: Use commercial MBL detection disks according to manufacturer instructions.

- Incubate plates at 35±2°C for 16-20 hours.

- Interpret results: Enhancement of the inhibition zone between the carbapenem and EDTA disks indicates MBL production.

Quality Control: Include known MBL-positive and MBL-negative control strains with each batch.

Protocol 2: Genotypic Detection of Carbapenem Resistance Genes

Principle: This protocol detects carbapenemase-encoding genes (OXA-48, NDM, VIM) in bacterial isolates using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [12].

Materials:

- Bacterial DNA extraction kit

- PCR master mix

- Primers for OXA-48, NDM, and VIM genes

- Thermal cycler

- Gel electrophoresis system

- DNA molecular weight markers

Procedure:

- Extract genomic DNA from pure bacterial colonies using standardized protocols.

- Prepare PCR reaction mixtures containing:

- 12.5μL PCR master mix

- 1μL forward primer (10μM)

- 1μL reverse primer (10μM)

- 2μL DNA template

- 8.5μL nuclease-free water

- Run amplification with the following cycling conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes

- 35 cycles of: 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 1 minute

- Final extension: 72°C for 7 minutes

- Analyze PCR products by gel electrophoresis (1.5% agarose).

- Visualize under UV transillumination and document results.

Interpretation: Compare amplicon sizes with expected sizes for target genes (OXA-48: 744bp, NDM: 621bp, VIM: 390bp).

Research Reagent Solutions for AMR Detection

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AMR Detection Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Mueller-Hinton Agar, Blood Culture Bottles | Standardized growth conditions for phenotypic AST [12] [14] |

| Antimicrobial Disks | Imipenem, Meropenem, EDTA-impregnated disks | Disk diffusion assays for resistance phenotype detection [12] |

| Molecular Biology Kits | DNA Extraction Kits, PCR Master Mix, Primers | Genotypic detection of resistance genes (OXA-48, NDM, VIM) [12] |

| Reference Strains | ATCC control strains for MBL production | Quality control for assay validation [12] |

| Rapid Test Components | Lateral Flow Strips, Specific Antibodies | Development of rapid diagnostic devices (e.g., Marple test) [29] |

| Microfluidic Chips | Custom-designed single-cell analysis chips | Next-generation rapid phenotypic AST platforms [14] |

Workflow Diagrams for AMR Testing

Diagram 1: Conventional vs. Rapid AST Workflows. This diagram compares the sequential steps and time requirements for conventional AST versus emerging rapid technologies that integrate or parallelize testing approaches.

Diagram 2: Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms and Detection Methods. This diagram illustrates the major resistance mechanisms and their relationship to phenotypic and genotypic detection approaches.

The global AMR burden represents both a public health emergency and a powerful driving force for diagnostic innovation. The surveillance data from WHO GLASS and research on specific high-priority pathogens like Acinetobacter baumannii provide the evidentiary foundation for intensified efforts to develop, validate, and implement novel AST technologies [12] [28]. The landscape of over 90 rapid phenotypic AST technologies in development reflects a robust pipeline of innovation targeting the critical need for faster, more accessible susceptibility testing [14].

Future progress will require continued investment in translational research, as exemplified by the EUP OHAMR's forthcoming 2026 call "Treatments and adherence to treatment protocols" with a budget exceeding €31 million, involving 37 funding organizations from 28 countries [30]. This transnational collaboration will explore new combination treatments, tools to improve adherence to treatment protocols, and assessment of antimicrobial impacts across human, animal, and environmental health sectors [30]. As these innovations mature, the integration of phenotypic and genotypic approaches will likely yield comprehensive diagnostic solutions that preserve the efficacy of existing antimicrobials while curbing the further emergence and spread of resistance across the One Health spectrum.

Technological Platforms: From Conventional Methods to Next-Generation Tools

In the ongoing research on antimicrobial resistance (AMR), the debate between phenotypic and genotypic testing methods is central. While genotypic methods rapidly detect known resistance genes, phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) remains the cornerstone for determining the actual response of bacteria to antimicrobial agents [31]. This document details the application and protocols for the three primary phenotypic gold standard methods, contextualized within intrinsic resistance research. These methods provide the definitive measurable phenotype against which genetic predictions must be ultimately correlated [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential materials and their specific functions for implementing phenotypic AST methods, as derived from cited research.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Phenotypic AST

| Item Name | Primary Function | Application Notes | Representative Examples (from search results) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB) | Standardized broth medium for dilution-based AST. | Ensures consistent ion concentration for reliable antibiotic activity. | Used in reference broth microdilution (BMD) methods [31]. |

| Iron-Depleted Mueller-Hinton (ID-MH) | Specialized medium for testing siderophore antibiotics. | Creates iron-limited conditions essential for drug uptake. | Critical for accurate cefiderocol testing [33]. |

| Commercial BMD Panels | Pre-configured microdilution plates for efficient MIC testing. | Validated for specific organism groups; reduces preparation time. | MICRONAUT-S Anaerobes MIC; Sensititre Anaerobe MIC [34]. |

| Gradient Diffusion Strips | Impregnated plastic strips for determining MIC on agar. | Provides flexibility for single-agent/single-isolate testing. | Liofilchem MIC Test Strips (MTS); bioMérieux Etest [34] [35]. |

| Antimicrobial Disks | Paper disks containing a defined antibiotic concentration for diffusion assays. | Enables qualitative susceptibility profiling and resistance screening. | Used in Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion (DD) method [33]. |

| Breakpoint Tables | Interpretive criteria defining S, I, and R categories. | Essential for translating MIC or zone diameter into a clinical prediction. | EUCAST Clinical Breakpoint Tables; CLSI M100 [36] [10]. |

Methodological Deep Dive: Protocols and Performance

Broth Microdilution (BMD)

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Preparation: Use sterile, cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB) for most aerobes. For fastidious organisms or specific drugs (e.g., cefiderocol), use specialized media like ID-MH [33].

- Inoculation: Prepare a standardized bacterial suspension (e.g., 0.5 McFarland) in saline or broth. Dilute the suspension to achieve a final inoculum of approximately 5 × 10^5 CFU/mL in each well of the microdilution plate [31].

- Incubation: Seal the plate to prevent evaporation and incubate at 35±2°C for 16-20 hours under ambient air. Incubation for 48 hours may be required for slow-growing bacteria or anaerobes [34].

- Reading and Interpretation: Examine each well for turbidity. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) is the lowest concentration of antimicrobial that completely inhibits visible growth. Compare the MIC to FDA or EUCAST breakpoints for categorical interpretation (S, I, R) [36] [10] [37].

Gradient Diffusion Method (GDM)

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Inoculation: Evenly swab a standardized bacterial suspension (0.5 McFarland) onto the surface of a suitable agar plate (e.g., Mueller-Hinton agar) to create a confluent lawn.

- Strip Application: Using sterile forceps, carefully apply the gradient strip onto the agar surface, ensuring full contact.

- Incubation: Invert the plate and incubate at 35±2°C for 16-20 hours.

- Reading and Interpretation: After incubation, the ellipse of inhibition will be visible. The MIC is read at the point where the ellipse's edge intersects the strip's scale [35]. This value is then interpreted using clinical breakpoints.

Disk Diffusion (DD)

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Inoculation and Disk Application: As with GDM, prepare a confluent bacterial lawn on Mueller-Hinton agar. Apply antibiotic disks to the surface using a sterilized dispenser or forceps, ensuring adequate spacing to prevent overlapping zones.

- Incubation: Invert and incubate the plate at 35±2°C for 16-18 hours.

- Reading and Interpretation: Measure the diameter of the complete inhibition zone (including the disk diameter) to the nearest millimeter. Interpret the zone diameter using standardized tables (e.g., EUCAST, CLSI) to categorize the isolate as Susceptible, Intermediate, or Resistant [33].

Comparative Performance Data

Recent studies highlight the performance characteristics of these methods against reference standards and each other.

Table 2: Comparative Analytical Performance of Phenotypic AST Methods

| Method | Organism Group | Essential Agreement (EA) with Reference | Categorical Agreement (CA) with Reference | Key Error Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broth Microdilution (Commercial Kits) | Clostridiales spp. [34] | Variable (48h incubation improved EA for some drugs) | >90% for metronidazole, piperacillin/tazobactam, vancomycin | Highest error rate for clindamycin |

| Gradient Diffusion Strips | Clostridiales spp. [34] | Lower than BMD for some drugs; acceptable for vancomycin | Above FDA threshold except for clindamycin & penicillin G | - |

| Gradient Diffusion (Etest) | Neisseria gonorrhoeae [35] | 95-96% with Agar Dilution | 66-83% for "alert" MICs (CRO, CFX, AZM) | Effective for rapid detection of emerging resistance |

| Commercial BMD (ComASP) | P. aeruginosa (Cefiderocol) [33] | 82.1% | 94.0% | Reliable for diagnostic use, possibly in combination |

| Commercial BMD (UMIC) | P. aeruginosa (Cefiderocol) [33] | 74.4% | 78.6% | Tendency to overestimate MICs |

Diagram 1: AST Workflow from Culture to Interpretation.

Critical Considerations for Research & Development

- Regulatory and Standards Alignment: A major update in 2025 saw the FDA fully recognize breakpoints from key CLSI standards (M100, M45), resolving a significant hurdle for test developers and ensuring U.S. laboratories can use current interpretive criteria [10] [37]. Researchers must align protocols with the latest EUCAST or CLSI guidelines.

- Resolving Genotype-Phenotype Discrepancies: Phenotypic AST is the definitive arbiter when genotypic predictions conflict with observed growth inhibition. A structured approach is required to investigate discrepancies, which may arise from off-target resistance mechanisms, gene expression levels, or technical factors [32].

- Tackling Technical Challenges: Specific organisms and antimicrobials present unique challenges. Testing anaerobes requires extended incubation (up to 48 hours) and specialized methods like the agar dilution reference [34]. Similarly, testing siderophore antibiotics like cefiderocol demands iron-depleted media to accurately simulate the in vivo environment and drug uptake [33].

Broth microdilution, disk diffusion, and gradient diffusion strips form an indispensable toolkit for grounding AMR research in measurable phenotypic reality. The choice of method depends on the required output (quantitative MIC vs. qualitative categorization), throughput, and organism-drug combination. As regulatory landscapes evolve and the complexity of resistance mechanisms increases, these phenotypic gold standards continue to provide the critical baseline against which novel genotypic methods and their predictions must be validated.

Application Notes

Next-generation phenotypic platforms represent a paradigm shift in biomedical research, moving beyond static, endpoint observations to dynamic, multi-parameter analyses of living systems. These integrated technological approaches—morphokinetic, microfluidic, and spectroscopic—provide unprecedented resolution for characterizing complex biological processes, from cellular development to drug resistance mechanisms. By capturing the temporal, spatial, and molecular dimensions of phenotypic expression, these platforms enable researchers to decipher the functional consequences of genetic variation and environmental perturbations with remarkable precision.

The integration of these technologies is particularly transformative for studying intrinsic resistance, where conventional genotypic approaches often fail to predict therapeutic outcomes due to the complex, multifactorial nature of drug resistance. Where genotypic testing identifies potential resistance markers based on genetic sequences, phenotypic platforms directly measure functional responses, capturing emergent properties that arise from complex biological networks. This capability is crucial for understanding non-genetic resistance mechanisms, adaptive cellular states, and the contribution of minority cell populations to treatment failure.

Technology-Specific Application Notes

Morphokinetic Profiling Platforms

Morphokinetic analysis leverages time-lapse monitoring to quantify the dynamic morphological changes and division kinetics of cells or embryos in response to experimental perturbations. This approach has demonstrated significant utility in predicting functional outcomes, including treatment efficacy and developmental potential.

In assisted reproduction research, morphokinetic parameters have proven highly predictive of live birth outcomes. A retrospective analysis of 429 blastocysts revealed that specific timing parameters, particularly the time to 5-blastomere stage (t5) and time to start of blastulation (tSB), showed statistically significant differences between embryos that resulted in live births versus those that failed to implant. Embryos with optimal morphokinetic parameters exhibited substantially higher developmental potential, enabling more reliable selection criteria [38].

The integration of artificial intelligence with morphokinetic analysis has further enhanced predictive accuracy. A comparative study evaluating 91 IVF cycles found that automated scoring systems (KIDScore and iDAScore) applied to time-lapse monitoring data effectively predicted live birth outcomes. KIDScore D5, which incorporates both morphokinetic parameters and morphological assessment, demonstrated particularly robust performance in identifying embryos with high implantation potential, providing a decision-support tool that outperforms conventional morphological assessment alone [39].

Table 1: Key Morphokinetic Parameters for Outcome Prediction

| Parameter | Biological Significance | Measurement Method | Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| t5 (time to 5 cells) | Embryo cleavage kinetics | Time-lapse imaging at 10-min intervals | Strong correlation with live birth outcome [38] |

| tSB (start of blastulation) | Initiation of differentiation process | Automated annotation of blastocoel formation | Significant predictor of implantation success [38] |

| KIDScore D5 | Composite algorithm of morphokinetics & morphology | AI-based analysis of time-lapse sequences | High efficiency in predicting live birth [39] |

| iDAScore | Fully automated blastocyst assessment | 3D convolutional neural network analysis | Correlates with reproductive outcome [39] |

Microfluidic Single-Cell Analysis Platforms

Microfluidic technologies enable high-resolution single-cell analysis under precisely controlled microenvironments, making them particularly valuable for detecting rare cell subpopulations that may contribute to intrinsic resistance. The single-cell encapsulation approach allows researchers to investigate cellular heterogeneity and identify resistant subsets that would be masked in bulk population analyses.

This technology operates on principles of pressure-driven flow and droplet generation, creating picoliter-scale aqueous compartments in an immiscible oil phase that serve as isolated microreactors for individual cells. The application of Poisson distribution statistics ensures optimal loading conditions, with recommended lambda values (λ) of 0.05-0.1 resulting in approximately 5% of droplets containing a single cell, while over 90% remain empty, and less than 0.5% contain multiple cells [40].

The applications of single-cell encapsulation span multiple research domains, each benefiting from the ability to resolve cellular heterogeneity:

- Oncology: Identifying rare resistant subpopulations carrying critical mutations

- Immunology: Characterizing diverse immune cell types and rare immune subsets

- Neurobiology: Constructing detailed neuronal maps and connection patterns

- Developmental Biology: Tracing lineage commitment and embryonic development

- Single-Cell Omics: Revealing tissue heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution [40]

This approach is particularly powerful for intrinsic resistance research, as it enables the functional characterization of rare persister cells that survive drug treatment through non-genetic adaptive mechanisms, potentially serving as reservoirs for eventual resistance development.

Spectroscopic Interaction Assays

Spectroscopic techniques provide label-free methods for quantifying molecular interactions in real-time, offering insights into the binding events that underlie drug efficacy and resistance mechanisms. These technologies have evolved toward increasingly sensitive detection limits, reduced sample requirements, and higher throughput capabilities.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Interaction Platforms

| Technique | Detection Principle | Key Applications | Sensitivity | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Reflectivity changes from surface plasmon waves | Protein-protein interactions, drug-target binding | pmol/L | Real-time kinetics, industry gold standard [41] |

| Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) | White light interference pattern shifts | Protein-small molecule interactions, antibody characterization | pmol/L | Simple operation, minimal sample consumption [41] |

| Back-Scattering Interferometry (BSI) | Refractive index changes in free solution | Molecular interactions without immobilization | Not specified | Free-solution technique, no surface attachment needed [41] |