Phenotypic Screening Platforms: A Comparative Analysis of Modern Technologies, AI Integration, and Clinical Success

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of contemporary phenotypic screening platforms, tailored for drug discovery researchers and professionals.

Phenotypic Screening Platforms: A Comparative Analysis of Modern Technologies, AI Integration, and Clinical Success

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of contemporary phenotypic screening platforms, tailored for drug discovery researchers and professionals. It explores the foundational shift from target-based to biology-first approaches, detailing the core technologies like high-content imaging and single-cell sequencing that enable unbiased discovery. The scope covers the integration of multi-omics data and AI/ML for enhanced mechanistic insight, tackles practical challenges in hit validation and data interpretation, and validates the approach through case studies of first-in-class medicines. The analysis synthesizes these elements to offer a strategic framework for platform selection and application, highlighting future directions in precision medicine.

The Resurgence of Phenotypic Screening: From Empirical Roots to a Modern Powerhouse for First-in-Class Drugs

The journey of bringing a new therapeutic to market is paved with critical strategic decisions, the most fundamental of which is the choice of discovery approach. Historically, drug discovery has been guided by two principal strategies: the phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) and the target-based drug discovery (TDD) approaches [1]. The PDD strategy involves identifying active compounds based on their measurable effects on whole cells, tissues, or organisms—their phenotype—often without prior knowledge of the specific molecular target [1] [2]. This "biology-first" strategy captures the complexity of biological systems and has been pivotal for uncovering first-in-class therapies and novel therapeutic mechanisms [1] [2]. In contrast, the TDD strategy begins with a well-characterized molecular target, such as a protein or gene, understood to play a key role in a disease pathway. Using advances in structural biology and genomics, this "rational design" approach aims to develop highly specific compounds that modulate the activity of this predefined target [1].

The debate between these paradigms is not about identifying a single superior method, but rather about understanding their complementary strengths, limitations, and optimal applications within a modern research pipeline. This guide provides an objective comparison of PDD and TDD, equipping researchers with the data and context needed to select the appropriate strategy for their specific discovery goals.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

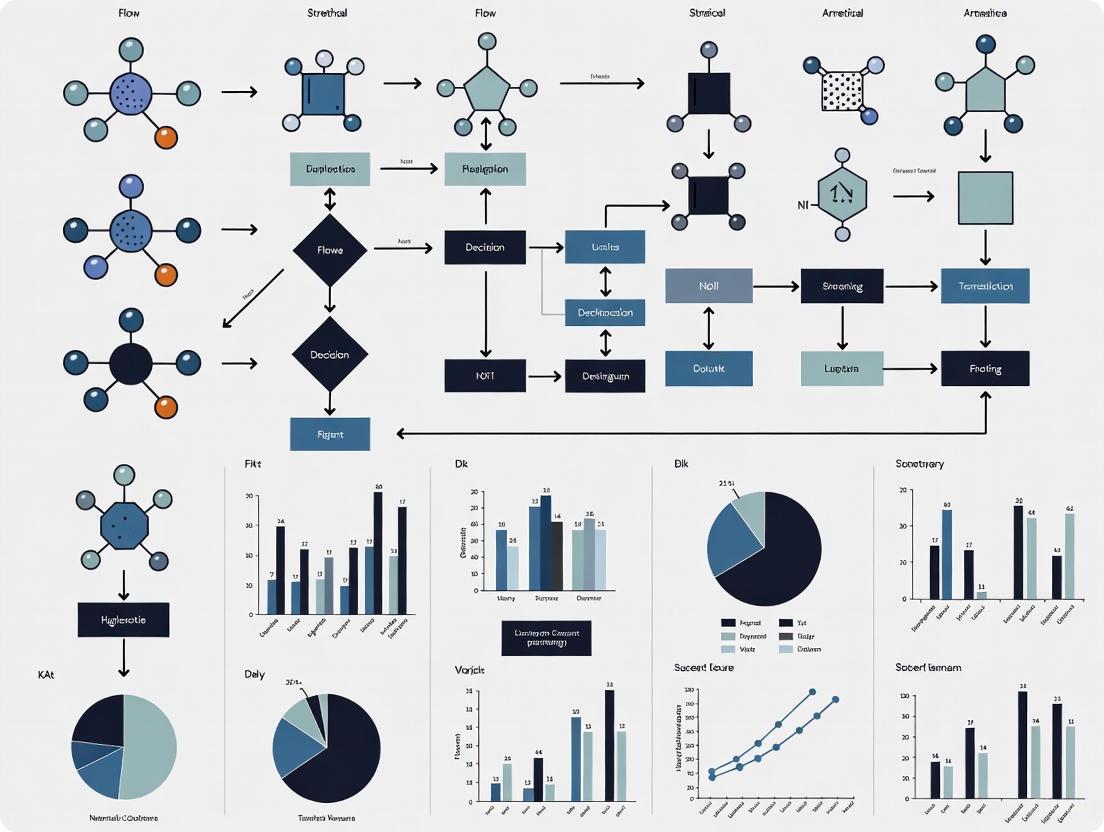

At their core, PDD and TDD differ in their starting point, primary screening focus, and underlying philosophy. The following workflow illustrates the distinct and interconnected paths of these two strategies.

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows of Phenotypic and Target-Based Drug Discovery Strategies

The fundamental distinction lies in the initial screening logic. PDD asks, "Does this compound produce a therapeutic effect in a biologically relevant system?" without presupposing the target. Conversely, TDD asks, "Does this compound potently and selectively modulate my predefined target?" [1] [2]. This difference has profound implications for the types of discoveries each approach enables, as detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Phenotypic and Target-Based Drug Discovery

| Feature | Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) | Target-Based Drug Discovery (TDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Disease model (cell, tissue, organism); no target hypothesis required [2] | Predefined, validated molecular target (e.g., protein, gene) [1] |

| Primary Screening Focus | Measurable therapeutic phenotype (e.g., cell death, morphological change) [1] [2] | Specific interaction with the target (e.g., binding affinity, enzyme inhibition) [1] |

| Key Advantage | Identifies first-in-class drugs; captures biological complexity and polypharmacology; expands "druggable" target space [1] [2] | Rational, efficient optimization; clearer initial Mechanism of Action (MoA); streamlined chemistry efforts [1] |

| Primary Challenge | Target deconvolution can be difficult and time-consuming; complex assays may have lower throughput [1] [2] | Relies on incomplete knowledge of disease biology; high attrition due to flawed target hypotheses [1] [2] |

| Success Profile | Disproportionate source of first-in-class medicines [2] | More effective for best-in-class drugs that improve on existing mechanisms [1] |

Key Experimental Data and Methodologies

Phenotypic Screening: From Simple Viability to High-Content Imaging

Modern phenotypic screening leverages complex disease models and high-content readouts. A key methodological advance is compressed phenotypic screening, which pools perturbations to scale up testing in physiologically relevant models.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Compressed Phenotypic Screening [3]

| Protocol Step | Description | Key Parameters & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Model & Perturbation | Use of biologically relevant models (e.g., patient-derived organoids, PBMCs) treated with pooled compounds. | Pool Size (P): 3-80 compounds per pool. Replication (R): Each compound appears in 3-7 distinct pools. Purpose: P-fold compression reduces sample number, cost, and labor [3]. |

| 2. High-Content Readout | Cell Painting assay: multiplexed fluorescent dyes image multiple cellular components. | Dyes: Hoechst 33342 (nuclei), ConA-AF488 (ER), MitoTracker Deep Red (mitochondria), etc. Purpose: Generates 886+ morphological features for deep phenotypic profiling [3]. |

| 3. Data Deconvolution | Computational framework using regularized linear regression and permutation testing. | Method: Infers single perturbation effects from pooled data. Output: Mahalanobis Distance (MD) quantifies overall morphological effect size for each compound [3]. |

| 4. Hit Identification | Analysis of phenotypic clusters and correlation with MoA. | Output: Drugs grouped by phenotypic response; identification of hits with conserved morphological impacts and novel biology [3]. |

Target-Based Screening: Leveraging Selectivity for Deconvolution

While traditional TDD is well-established, a hybrid approach uses target-based principles to solve the PDD challenge of target deconvolution. This involves screening with highly selective tool compounds to link phenotypes to targets.

Table 3: Experimental Protocol for Selective Ligand-Based Target Deconvolution [4]

| Protocol Step | Description | Key Parameters & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Compound Curation | Mine bioactivity databases (e.g., ChEMBL) to identify highly selective tool compounds. | Filters: pChEMBL > 6 (IC50 < 1µM); exclude PAINS; purchasable. Selectivity Score: Rewards activity on primary target and inactivity on others [4]. |

| 2. Phenotypic Screening | Screen selective compound library in disease-relevant phenotypic assay. | Model: NCI-60 cancer cell line panel. Concentration: 10 µM. Readout: Cell growth inhibition (%) [4]. |

| 3. Hit Analysis | Correlate phenotypic hits with known targets of selective compounds. | Purpose: A hit implies the compound's target is relevant to the observed phenotype, providing immediate MoA direction [4]. |

| 4. Validation | Confirm target engagement and causal role in phenotype through follow-up studies. | Outcome: Identifies novel, therapeutically relevant targets (e.g., HSF1, RORγ) linked to cancer cell growth inhibition [4]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of either paradigm relies on a suite of specialized reagents, assays, and computational tools.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Drug Discovery Screening

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Utility | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay | A high-content, multiplexed imaging assay that uses up to six fluorescent dyes to visualize and quantify morphological features of cells [3]. | PDD: Profiling compound-induced phenotypic changes; clustering compounds by MoA. |

| Patient-Derived Organoids | 3D cell cultures derived from patient tissues that better recapitulate in vivo physiology and disease states compared to traditional cell lines [3]. | PDD: High-fidelity disease modeling for phenotypic screening. |

| ChEMBL Database | A manually curated database of bioactive, drug-like small molecules containing bioactivity data, assays, and targets [4] [5]. | TDD & PDD: Source for target validation, tool compound identification, and selectivity analysis. |

| Selective Tool Compound Library | A collection of small molecules with well-characterized and highly selective target profiles [4]. | PDD: Used for direct target deconvolution in phenotypic screens. |

| JUMP-CP Cell Painting Dataset | A large public cell imaging dataset from genetic and chemical perturbations, used for training AI models [6]. | PDD: Reference dataset for interpreting morphological profiles and predicting MoA. |

| PhenAID Platform | An AI-powered platform that integrates cell imaging data with AI-chem and computer vision to analyze high-content screens and design molecules [6] [7]. | PDD: AI-driven analysis of phenotypic data, MoA prediction, and virtual screening. |

Integrated and Future Approaches

The dichotomy between PDD and TDD is increasingly blurring. The most productive modern pipelines adopt integrated hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both paradigms [1] [7]. A common strategy is to use PDD for initial hit identification in a biologically complex system, followed by TDD methods for lead optimization and MoA elucidation. Conversely, compounds discovered via TDD are frequently validated in phenotypic assays to confirm their functional effects in a more physiologically relevant context [1].

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are now central to this integration. AI models can analyze high-dimensional data from phenotypic screens (e.g., Cell Painting) to predict MoA and identify compounds that induce a desired phenotype [6] [7]. Furthermore, ML techniques are powerful tools for multi-target drug discovery, helping to design compounds with intentional polypharmacology by predicting drug-target interactions across complex biological networks [5]. The future of drug discovery lies in adaptive, integrated workflows that connect functional phenotypic insights with mechanistic target-based understanding to enhance efficacy and overcome therapeutic resistance [1].

The biopharmaceutical industry is undergoing a significant strategic realignment, marked by a nuanced recalibration of therapeutic modalities within R&D portfolios. While the past decade witnessed the spectacular rise of biologics, recent data reveals a compelling and often overlooked trend: the enduring strategic significance of the small-molecule drug. An analysis of FDA approvals from 2012 to 2022 shows that small molecules consistently accounted for approximately 57% of all novel therapies reaching the market. This momentum has accelerated, with small molecules comprising 72% of novel drug approvals as of mid-2025 [8]. This resurgence is not a simple reversion to the past but is instead driven by advances in screening technologies, new therapeutic classes, and a refined understanding of the economic and clinical value of compact compounds. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the forces reshaping pharmaceutical portfolios, offering experimental data and methodologies central to this ongoing transformation.

Quantitative Analysis of Portfolio Shifts: Small Molecules vs. Biologics

The strategic calculus for pharmaceutical R&D hinges on a clear-eyed comparison of the two dominant therapeutic modalities. The table below summarizes the core differences and performance metrics of small molecules and biologics, providing a foundational dataset for portfolio analysis [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Small Molecules and Biologics

| Property | Small Molecules | Biologics |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size | Low molecular weight (typically <900 Da) | High molecular weight (hundreds to thousands of times larger) |

| Synthesis | Chemically synthesized in a lab | Derived from living organisms/cells |

| Stability | Generally stable, can be stored at room temperature | Sensitive to light and heat; require specialized storage |

| Administration Route | Oral (pill, capsule), topical, or injection | Injection or infusion only |

| Mechanism of Action | Can penetrate cell membranes to target intracellular proteins | Tend to act on cell surfaces or extracellular components |

| FDA Pathway | New Drug Application (NDA) | Biologics License Application (BLA) |

| Follow-on Products | Generics (ANDA Pathway) | Biosimilars (BPCIA Pathway) |

Beyond these fundamental characteristics, the economic and developmental profiles of these modalities reveal a more complex and often counterintuitive story. A comprehensive study analyzing 599 new therapeutic agents approved between 2009 and 2023 provides the following comparative data [8]:

Table 2: Strategic Development and Economic Profile Comparison

| Development & Economic Factor | Small Molecules | Biologics |

|---|---|---|

| Median R&D Cost | ~$2.1 Billion | ~$3.0 Billion |

| Median Development Time | ~12.7 Years | ~12.6 Years |

| Clinical Trial Success Rate | Lower at every phase | Higher at every phase |

| Median Patent Count | 3 patents | 14 patents |

| Median Time to Competition | 12.6 Years | 20.3 Years |

| Median Annual Treatment Cost | $33,000 | $92,000 |

| Median Peak Revenue | $0.5 Billion | $1.1 Billion |

The data indicates that while development times are nearly identical and costs are only slightly higher for biologics, their higher clinical trial success rates and significantly higher peak revenues reshape the investment calculus. Furthermore, the stronger intellectual property protection, evidenced by a median of 14 patents for biologics versus 3 for small molecules, offers a longer competitive shield [8].

Experimental Protocols: Phenotypic Screening and AI-Driven Discovery

The resurgence of small molecules is inextricably linked to the adoption of new, more powerful discovery methodologies. The re-emergence of phenotypic screening—a biology-first approach that observes how cells respond to perturbations without presupposing a target—is a key driver [7].

Protocol: Integrated Phenotypic Screening Workflow

This protocol outlines the modern workflow for phenotypic screening, which integrates high-content data and AI.

Sample Preparation and Perturbation:

- Cell Source: Utilize patient-derived cells or genetically engineered cell lines. For higher physiological relevance, patient-derived organoids (PDOs) are increasingly used as they preserve the cellular composition and heterogeneity of the parental tumor [9].

- Perturbation: Treat cells with chemical compounds (small molecule libraries) or genetic perturbations (e.g., CRISPR-based). Modern approaches use pooled perturbation screens (e.g., Perturb-seq) with computational deconvolution to dramatically reduce sample size, labor, and cost while maintaining information-rich outputs [7].

High-Content Phenotypic Profiling:

- Assay: Employ the Cell Painting assay, a high-content microscopic technique that uses fluorescent dyes to visualize multiple fundamental cellular components (e.g., nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, cytoskeleton) [7].

- Imaging: Use automated, high-throughput microscopy to capture detailed morphological images of the stained cells after perturbation.

Data Processing and Feature Extraction:

- Image Analysis: Apply image analysis pipelines to convert raw images into quantitative data. These pipelines extract thousands of morphological features (e.g., cell size, shape, texture, organellar organization) for each cell, generating a rich phenotypic profile [7].

- Data Normalization: Normalize data to correct for technical variation (e.g., plate-to-plate differences) using standardized algorithms.

AI-Powered Data Integration and Analysis:

- Data Fusion: Use machine learning (ML) and deep learning models to integrate the high-dimensional phenotypic data with other multi-omics data (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics) [7]. This fusion creates a unified model of the compound's effect.

- Pattern Recognition: Train AI models to detect subtle, disease-relevant phenotypic patterns that correlate with the mechanism of action (MoA), efficacy, or safety of the tested compounds [7].

- Hit Validation: The output identifies promising "hit" compounds that induce a desired phenotypic change, which are then prioritized for further validation.

Modern Phenotypic Screening Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Phenotypic Screening

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Modern Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay Dyes | A panel of fluorescent dyes that stain specific cellular compartments (e.g., nuclei, cytoskeleton, mitochondria) to enable high-content morphological analysis [7]. |

| Matrigel / BME | A basement membrane extract used as a 3D scaffold for culturing patient-derived organoids, providing a more physiologically relevant environment than 2D plastic [9]. |

| Rho-kinase (ROCK) Inhibitor | A key supplement (e.g., Y-27632) in organoid and primary cell culture media that inhibits anoikis (cell death upon detachment), significantly improving cell viability and culture success rates [9]. |

| Culturing Factors (WENR) | A combination of growth factors and signaling molecules (Wnt3a, EGF, Noggin, R-spondin-1) critical for the long-term growth and differentiation of stem-cell-derived organoids [9]. |

| Pooled Perturbation Libraries | Collections of genetic (e.g., CRISPR) or chemical perturbations designed to be screened in a pooled format, which are later deconvoluted computationally to identify individual effects [7]. |

Drivers of the Small Molecule Resurgence and Strategic Implications

The renewed focus on small molecules is not accidental. It is the result of several converging technological and market forces that have altered their strategic value.

Novel Modalities and Target Space: The success of new small-molecule drug classes, most notably GLP-1 receptor agonists for obesity and diabetes, has demonstrated the blockbuster potential and transformative health impact of this modality [10] [11]. Furthermore, small molecules remain the primary modality for targeting intracellular proteins and can cross the blood-brain barrier, granting access to a target space that is often inaccessible to larger biologics [8].

AI-Powered Discovery Platforms: Artificial intelligence is rewriting the R&D equation for small molecules. AI platforms can predict drug-target interactions, optimize molecular designs, and significantly compress discovery timelines. For instance, Insilico Medicine designed a novel compound and brought it to Phase 1 clinical trials in under 30 months—a process that normally takes a decade [11]. This "discovery by design" increases the probability of success and reduces the cost of small molecule R&D [11] [12].

Economic and Clinical Logistics: Small molecules offer inherent advantages in manufacturing, storage, and administration. Their stability at room temperature simplifies supply chains, and their ability to be formulated as oral solid dosages (e.g., pills) greatly improves patient convenience and adherence compared to injectable biologics [8] [12]. This can lead to better real-world outcomes and reduced treatment costs.

The Evolving Biologics Landscape: While biologics are crucial, their market dynamics are changing. The arrival of biosimilars is increasing competition for original biologics. Furthermore, a growing scientific consensus, supported by over 600 studies, suggests that for biosimilars with proven analytical similarity and pharmacokinetic equivalence, comparative efficacy studies may be redundant [13]. This could lower biosimilar development costs and accelerate patient access, intensifying price competition in the biologics space and making a balanced portfolio more critical [13].

Key Drivers of Small Molecule Resurgence

The evidence indicates that the future-ready pharmaceutical company will not be one that bets exclusively on a single modality. Instead, the most future-ready organizations—such as Johnson & Johnson, Roche, and AstraZeneca, which lead the 2025 Future Readiness Indicator—are those that maintain broadly diversified portfolios, spanning traditional small molecules, biologics, and next-generation platforms like cell and gene therapies [11]. The industry is shifting from a pure "products" model to an "industry of solutions," where pairing therapies with devices, apps, and data services creates deeper patient engagement and improves outcomes [11]. The resurgence of the small molecule, powered by phenotypic screening, AI, and novel chemistry, is a testament to the dynamic nature of pharmaceutical innovation. It underscores the need for a nuanced, data-driven portfolio strategy that leverages the unique strengths of all therapeutic modalities to deliver maximum patient and shareholder value.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Resurgence of an Empirical Powerhouse

- Quantifying Success: PDD's Disproportionate Impact

- Mechanisms of Discovery: How PDD Uncovers Novel Therapeutics

- The Phenotypic Screening Workflow: From Assay to Candidate

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for PDD

- Comparative Analysis: PDD Versus Target-Based Drug Discovery

- Conclusion: The Integrated Future of Drug Discovery

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) is a strategy for identifying pharmacologically active molecules based on their effects in realistic, cell-based or whole-organism disease models, without prior knowledge of the specific molecular target [2]. In contrast to target-based drug discovery (TDD), which focuses on modulating a predefined, hypothesized drug target, PDD is mechanism-agnostic, allowing biology to reveal novel therapeutic pathways [14] [15]. After being overshadowed by TDD following the molecular biology revolution, PDD has experienced a major resurgence over the past decade. This renewed interest was catalyzed by a seminal analysis revealing that between 1999 and 2008, a majority of first-in-class small-molecule drugs were discovered through empirical, PDD-like approaches [14] [2]. Modern PDD combines this empirical philosophy with advanced tools such as human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), high-content imaging, and sophisticated bioinformatics, establishing itself as an indispensable discovery modality for tackling unmet medical needs and identifying unprecedented mechanisms of drug action [15] [2].

Quantifying Success: PDD's Disproportionate Impact

The value of PDD is most clearly demonstrated by its track record of producing first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms of action (MoA). The following table summarizes key approved drugs originating from phenotypic screens, highlighting the novel biology they revealed.

Table 1: Notable First-in-Class Medicines Discovered Through PDD

| Drug Name | Disease Area | Key PDD Assay System | Novel Mechanism of Action (MoA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daclatasvir [14] [2] | Hepatitis C (HCV) | Target-agnostic HCV replicon assay in human cells | Identified NS5A, a viral protein with no known enzymatic function, as a pivotal drug target. |

| Ivacaftor, Tezacaftor, Elexacaftor [14] [2] | Cystic Fibrosis (CF) | Cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants | Includes "correctors" that enhance CFTR protein folding and trafficking, an unexpected MoA. |

| Risdiplam, Branaplam [14] [2] | Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) | Cell-based reporter assays for SMN2 splicing modulation | Modulates SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing by stabilizing the U1 snRNP complex, a novel target. |

| Lenalidomide [2] | Multiple Myeloma | Clinical observation (derivative of thalidomide) | Binds to E3 ubiquitin ligase Cereblon, redirecting it to degrade specific transcription factors (IKZF1/3). |

This track record is further supported by quantitative analyses of drug approval patterns. A key study examining New Molecular Entities (NMEs) approved by the U.S. FDA between 1999 and 2008 found that phenotypic screening strategies were responsible for the discovery of a majority of first-in-class drugs [14]. In contrast, the majority of "follower" drugs were discovered using target-based approaches. This analysis concluded that the mechanistic knowledge available when a program is initiated is often insufficient to provide a blueprint for first-in-class medicines, a knowledge gap that PDD is uniquely positioned to address empirically [14].

Mechanisms of Discovery: How PDD Uncovers Novel Therapeutics

PDD expands the "druggable target space" by uncovering therapeutics that work through cellular processes and targets often considered intractable by rational design.

- Novel Target Identification: PDD can reveal entirely new drug targets, as exemplified by the discovery of NS5A for Hepatitis C. The initial phenotypic screen using an HCV replicon system identified daclatasvir; only subsequent isolation of drug-resistant mutations identified the molecular target, NS5A, a protein with no previously known biochemical function [14] [2].

- Unprecedented Mechanisms for Known Targets: PDD can also identify novel MoAs for known targets. The discovery of CFTR correctors for Cystic Fibrosis revealed a small-molecule mechanism for improving the folding and plasma membrane insertion of a misfolded protein, a function not predicted by the target's known role as an ion channel [14] [2].

- Polypharmacology: Phenotypic screens can identify molecules whose therapeutic effect depends on simultaneous, moderate modulation of multiple targets (on-target polypharmacology). This can be a powerful strategy for complex, polygenic diseases where single-target approaches have shown limited success [2].

The Phenotypic Screening Workflow: From Assay to Candidate

A robust PDD campaign involves a series of methodical steps, from developing a biologically relevant assay to identifying a clinical candidate. The workflow below visualizes this multi-stage process.

Diagram Title: The Phenotypic Drug Discovery Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Phases:

Assay Development and Primary Screening:

- Objective: To establish a robust, disease-relevant system for high-throughput compound testing.

- Methodology: A key advance is the use of high-content, image-based phenotypic screens [16]. This involves:

- Reporter Cell Lines: Utilizing engineered cells, often with fluorescent protein tags marking specific cellular compartments or proteins of interest, to enable automated image analysis. For example, a library of triply-labeled live-cell reporters (e.g., nuclear, cytoplasmic, and a specific protein biomarker) can be constructed [16].

- Phenotypic Profiling: Cells are treated with compounds from diverse libraries. Automated microscopy captures images, which are then computationally analyzed to extract hundreds of quantitative features related to cell morphology, protein intensity, texture, and localization [16].

- Profile Generation: For each compound, differences in feature distributions between treated and control cells are summarized into a numerical "phenotypic profile" vector using statistical measures like the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic [16].

Hit Validation and Prioritization:

- Objective: To confirm the activity of initial "hits" and prioritize those with the most promising therapeutic profiles.

- Methodology: This involves:

- Dose-Response Confirmation: Retesting hits across a range of concentrations to confirm potency and efficacy.

- Counter-Screens: Ruling out non-specific or undesirable mechanisms (e.g., general cytotoxicity, assay interference).

- Hit Triage: Using the phenotypic profiles to cluster hits with known drugs, providing early, mechanism-informed prioritization before resource-intensive target deconvolution begins [17] [16].

Target Deconvolution:

- Objective: To identify the molecular mechanism of action (MMOA) of a validated phenotypic lead.

- Methodology: This remains a challenge but can be addressed with several tools:

- Genetic Approaches: Using CRISPR/Cas9 or RNAi screens to identify genes whose modification abrogates the compound's phenotypic effect [15].

- Biochemical Methods: Affinity chromatography using immobilized compound baits to pull down interacting proteins from cell lysates, followed by mass spectrometry for identification [2].

- Resistance Mapping: Isolating compound-resistant mutant cells and sequencing their genomes to identify mutated genes that may encode the drug target or resistance pathway components [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for PDD

Successful implementation of PDD relies on a suite of specialized research reagents and biological tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Phenotypic Discovery

| Reagent / Tool | Function in PDD | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter Cell Lines [16] | Engineered cells that serve as the biosensor for the phenotypic readout, enabling high-content imaging. | Genetically tagged with fluorescent proteins (e.g., YFP, CFP, RFP) for organelles or pathway-specific biomarkers. "ORACL" lines can be identified for optimal drug classification [16]. |

| iPSC-Derived Cells [14] [15] | Provide physiologically relevant, human-derived disease models (e.g., neurons, cardiomyocytes). | Critical for modeling complex diseases; used in screens for SMA and other neurological disorders [14]. |

| Compound Libraries [14] | Diverse collections of small molecules used for screening. | Design balances chemical diversity, tractability, and biological target coverage. Includes biologically active libraries and genetic-derived tools (cDNA, shRNA) [14]. |

| High-Content Imaging Biomarkers [16] | Fluorescent tags or dyes used to quantify cellular phenotypes. | Includes fluorescent protein tags, immunofluorescent antibodies, and chemical dyes for monitoring cell health, morphology, and pathway activity. |

| Microphysiological Systems (Organs-on-Chips) [17] | Advanced 3D cell culture systems that mimic human organ physiology and disease. | Emerging tool for increasing the translatability of phenotypic assays and supporting clinical pathway decisions [17]. |

Comparative Analysis: PDD Versus Target-Based Drug Discovery

Choosing between PDD and TDD depends on project goals, available knowledge, and the acceptable level of risk. The table below provides a structured comparison.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of PDD and Target-Based Drug Discovery (TDD)

| Feature | Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) | Target-Based Drug Discovery (TDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Disease phenotype or biomarker in a complex biological system [14] [15]. | A predefined molecular target (e.g., protein, gene) with a hypothesized role in disease [14]. |

| Key Strength | High potential for first-in-class medicines and novel target/MoA discovery [14] [2]. | Streamlined, hypothesis-driven process with a clear, known mechanism from the outset [14]. |

| Primary Challenge | Target deconvolution can be difficult, time-consuming, and sometimes unsuccessful [15]. | Requires complete and correct understanding of disease biology; high risk of translational failure if hypothesis is wrong [14]. |

| Success Rate (First-in-Class) | Higher – responsible for a majority of first-in-class small-molecule drugs (1999-2008) [14]. | Lower – more successful for "follower" drugs that modulate previously validated targets [14]. |

| Best Application | Areas with poor biological understanding, for novel MoAs, or when targeting complex, polygenic diseases [2]. | When the target is well-validated and its modulation is confidently expected to yield a safe, therapeutic effect. |

The empirical power of Phenotypic Drug Discovery is undeniable, with a proven track record of delivering transformative, first-in-class medicines for some of the most challenging diseases. Its ability to bypass incomplete biological knowledge and empirically identify effective therapeutics, including those with unprecedented mechanisms, ensures its enduring value. Rather than a competition between paradigms, the future of drug discovery lies in the strategic integration of PDD and TDD. PDD will continue to be the engine for initial innovation, uncovering novel biology and lead compounds. Subsequently, target-based approaches and modern tools like functional genomics and artificial intelligence will be crucial for optimizing these leads, deconvoluting their mechanisms, and derisking their path to the clinic. This synergistic combination promises to fuel the next generation of successful drug discovery projects.

Phenotypic screening has re-emerged as a powerful strategy in modern drug discovery, enabling the identification of first-in-class therapeutics by focusing on therapeutic effects in realistic disease models without requiring prior knowledge of a specific molecular target [2] [18]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of contemporary phenotypic screening platforms, evaluating their performance, experimental protocols, and applicability for investigating complex disease biology.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Phenotypic Screening

- Comparative Platform Analysis

- Experimental Protocols & Workflows

- Key Research Reagent Solutions

- Conclusion

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) is defined by its focus on modulating a disease phenotype or biomarker in a physiologically relevant model system to provide a therapeutic benefit, rather than beginning with a pre-specified molecular target [2]. This unbiased approach is particularly valuable for tackling complex, polygenic diseases and when the underlying biological pathways are poorly characterized [1]. It has successfully expanded the "druggable target space" by uncovering novel mechanisms of action (MoA), such as small molecules that modulate pre-mRNA splicing or induce targeted protein degradation, leading to first-in-class medicines for conditions like spinal muscular atrophy and multiple myeloma [2] [18]. The core principle lies in leveraging chemical interrogation to link therapeutic biology to previously unknown signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms.

Comparative Platform Analysis

The following section objectively compares the performance and characteristics of several modern phenotypic screening approaches, from AI-powered virtual screens to high-content imaging platforms.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Phenotypic Screening Platforms

| Platform / Model Name | Core Technology | Reported Performance Advantage | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| PhenoModel/PhenoScreen [19] | Multimodal foundation model integrating molecular structures & cell phenotype images (Cell Painting) | Superior performance in DUD-E and LIT-PCBA benchmarks for virtual screening; outperforms traditional structure-based methods [19] | Target- and phenotype-based virtual screening for novel inhibitors |

| DrugReflector [20] | Closed-loop active reinforcement learning on transcriptomic signatures | An order of magnitude improvement in hit-rate compared to screening a random drug library [20] | Predicting compounds that induce desired phenotypic changes from gene expression data |

| Ardigen phenAID [21] | Proprietary transformer-based AI model using image-derived features | 3x better performance than predefined benchmarks; 2x improvement in predictive accuracy vs. human-defined features [21] | Biologist-accessible virtual phenotypic screening for hit identification |

| Self-supervised Image Representation [22] | Deep learning on high-content screening (HCS) images (e.g., U2OS cells, CellPainting) | Provides robust representations less affected by batch effects; achieves performance on par with standard supervised approaches [22] | Mode of action and property prediction from cellular images |

Table 2: Characteristics and Applicability of Screening Approaches

| Platform / Model Name | Data Input Type | Chemical Diversity | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| PhenoModel/PhenoScreen [19] | SMILES strings, cell images | 4x higher than structure-based screening [19] | Discovering novel scaffolds with similar activity to known actives |

| DrugReflector [20] | Transcriptomic signatures | Information not specified | Complex disease signatures compatible with proteomic/genomic inputs |

| Ardigen phenAID [21] | Not explicitly stated | High (broader chemical space explored) [21] | Deployable enterprise-scale screening within pharmaceutical pipelines |

| Self-supervised Image Representation [22] | High-content microscopy images | Information not specified | Building universal, generalizable models for HCS data analysis |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed methodologies are critical for interpreting results and replicating studies. This section outlines standard and emerging experimental workflows in phenotypic screening.

Phenotypic Screening and Target Deconvolution Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a generalized integrated workflow that bridges phenotypic screening with accelerated mechanistic follow-up, incorporating advanced technologies for hit prioritization and target identification.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AI-Guided Virtual Phenotypic Screening using PhenoModel

- Objective: To identify active molecules for multiple cancer cell lines by integrating molecular structure and cell phenotype data.

- Methodology:

- Molecular Feature Extraction: A four-layer Weisfeiler-Lehman Network (WLN) pre-trained with GeminiMol weights encodes molecular structures (from SMILES strings) into high-dimensional embeddings [19].

- Cell Image Feature Extraction: A Vision Transformer (ViT) model based on QFormer, which incorporates a Quadrangle Attention mechanism, is applied to encode cell images from high-content screening [19].

- Dual-space Joint Training: The molecular and image encoders are simultaneously trained using contrastive learning to align the two feature spaces and enhance model performance [19].

- Virtual Screening: The trained PhenoModel ranks molecules by their likelihood of inducing the desired phenotype. For the PhenoScreen pipeline, known active compounds are used to screen for other molecules with similar activities but novel scaffolds [19].

Protocol 2: Integrated Phenotypic Screening and Target Identification using µMap

- Objective: To rapidly prioritize and characterize small molecule hits from a high-throughput phenotypic screen, using targeted protein degradation as a test case [23].

- Methodology:

- Primary Phenotypic Screen: Conduct a high-throughput screen to identify compounds that induce a desired phenotypic outcome, such as the degradation of a specific protein (e.g., BACH2) [23].

- Hit Triage with Immunophotoproximity Labeling (µMapX): Profile shortlisted hit compounds using µMapX. This technology uses photoproximity labeling to characterize drug-induced interactome changes of an endogenous protein target, helping to triage hits with promising or discrete mechanisms [23].

- Target Engagement with Photocatalytic µMap (µMap TargetID): Apply µMap TargetID to characterize direct protein engagement for the candidate compounds. This provides orthogonal mechanistic insight and helps confirm the direct cellular targets of the phenotypic hits [23].

Protocol 3: Transcriptomic Phenotypic Screening with DrugReflector

- Objective: To predict compounds that induce desired phenotypic changes based on gene expression signatures [20].

- Methodology:

- Model Training: Train the DrugReflector model on a large resource of compound-induced transcriptomic signatures, such as the LINCS Connectivity Map [20].

- Closed-Loop Active Learning: Implement a reinforcement learning framework. The model's predictions are tested experimentally, and the resulting new transcriptomic data is fed back into the model for iterative refinement, creating a closed-loop that improves prediction accuracy over cycles [20].

- Screening: Use the trained model to screen and prioritize compounds from a library that are most likely to produce the desired transcriptomic signature associated with a target phenotype [20].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful phenotypic screening relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below details essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Screening | Specific Example / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay [22] | A high-content, multiplexed imaging assay that uses fluorescent dyes to label multiple cell components, revealing morphological profiles for thousands of cells. | Used for generating image-based profiles for chemical and genetic perturbations in the JUMP-CP consortium dataset [22]. |

| µMap Photoproximity Labeling Reagents [23] | Small molecule probes that, upon photoactivation, label biomolecules in their immediate vicinity (< 10 nm), enabling mapping of protein interactions and engagement. | Used for hit triage (µMapX) and target identification (µMap TargetID) in integrated phenotypic screening platforms [23]. |

| U2OS Cell Line [22] | A commonly used osteosarcoma cell line in high-content screening due to its adherent properties, large cytoplasm, and suitability for imaging-based assays. | A primary cell model used in conjunction with the Cell Painting protocol for generating universal representation models for HCS data [22]. |

| Cereblon (CRBN) Binders [1] [2] | Small molecules (e.g., Lenalidomide, Pomalidomide) that bind to the E3 ubiquitin ligase cereblon, altering its substrate specificity. | Serves as both phenotypic immunomodulatory drugs and key tools for targeted protein degradation (e.g., in PROTACs) [1] [2]. |

| LINCS Connectivity Map [20] | A large-scale public database containing transcriptomic profiles of human cells treated with bioactive small molecules. | Serves as a foundational training dataset for AI models like DrugReflector that predict compounds based on gene expression signatures [20]. |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates a clear evolution in phenotypic screening platforms. Traditional, purely experimental screens are being augmented and, in some cases, replaced by integrated, AI-driven approaches that dramatically improve efficiency and success rates. Platforms like PhenoModel and Ardigen phenAID show that leveraging multimodal data and advanced machine learning can yield higher hit-rates and greater chemical diversity than traditional structure-based methods [19] [21]. Furthermore, the integration of novel mechanistic tools like µMap photoproximity labeling directly addresses the historical bottleneck of target deconvolution, creating a more seamless pipeline from phenotype to mechanism [23]. For researchers investigating complex disease biology, the modern toolkit for unbiased investigation is increasingly defined by these hybrid strategies that combine the physiological relevance of phenotypic assays with the predictive power of computational models.

Inside the Toolbox: A Comparative Look at High-Content, Genomic, and AI-Driven Screening Technologies

This guide provides an objective comparison of three core platform technologies—High-Content Imaging, Single-Cell Sequencing, and Functional Genomics. It is designed to help researchers and drug development professionals select optimal technologies for phenotypic screening by presenting performance data, experimental protocols, and essential toolkits.

The integration of high-content imaging (HCI), single-cell sequencing, and functional genomics is reshaping phenotypic screening by providing multi-dimensional data on cellular responses. High-content imaging captures morphological and subcellular changes in response to perturbations, with recent advancements enabling high-throughput screening of complex 3D models [24]. Single-cell sequencing technologies, particularly single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), dissect cellular heterogeneity within tissues or organoids by profiling gene expression at individual cell resolution, which is crucial for building cell atlases [25]. Functional genomics focuses on understanding gene function and interactions through targeted perturbations, with key applications in identifying disease mechanisms and drug targets [26] [27].

These platforms are increasingly used complementarily. For example, spatial transcriptomics technologies, an extension of single-cell sequencing, map gene expression within tissue architecture, bridging cellular morphology with genomic readouts [28]. Similarly, functional genomics approaches can leverage imaging-based fingerprints from HCI to predict compound activity in unrelated biological assays, effectively repurposing primary screening data [29].

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Data

Benchmarking Single-Cell Sequencing Platforms

Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics platforms were systematically compared using Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tumor samples to evaluate performance metrics crucial for translational research [28].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms using FFPE Samples

| Platform | Panel Size (Genes) | Average Transcripts per Cell | Key Performance Findings | Tissue Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CosMx (SMI) | 1,000 | Highest (p<2.2e-16) | Some key immune markers (e.g., CD3D, FOXP3) expressed at levels similar to negative controls in older samples. | Limited (545 μm × 545 μm FOVs) |

| MERFISH | 500 | Lower in older ICON TMAs; Higher in newer MESO TMAs (p<2.2e-16) | Lacked negative control probes, preventing full assessment of background signal. | Full tissue core |

| Xenium (Unimodal) | 339 (289-plex + 50 custom) | Higher than Xenium-MM (p<2.2e-16) | Minimal target gene probes expressed similarly to negative controls. | Full tissue core |

| Xenium (Multimodal) | 339 (289-plex + 50 custom) | Lower than Xenium-UM (p<2.2e-16) | Few target gene probes (0.6%) expressed similarly to negative controls. | Full tissue core |

Benchmarking Data Integration for Single-Cell Genomics

As single-cell datasets grow in complexity, robust data integration methods are essential. A comprehensive benchmark of 16 integration methods on 13 tasks representing over 1.2 million cells evaluated methods on their ability to remove batch effects while conserving biological variation [30]. Key findings include:

- Top-performing methods: scANVI, Scanorama, scVI, and scGen performed well, particularly on complex integration tasks involving data from multiple tissues, laboratories, and conditions [30].

- Importance of preprocessing: Highly variable gene (HVG) selection improved the performance of most data integration methods, while scaling pushed methods to prioritize batch removal over conservation of biological variation [30].

- Evaluation metrics: Methods were assessed using 14 metrics balancing batch effect removal (e.g., kBET, kNN graph connectivity) and biological conservation (e.g., trajectory conservation, cell-type ASW) [30].

High-Content Imaging: Confocal vs. Widefield

The choice between confocal and widefield imaging significantly impacts data quality in HCI, especially for 3D samples.

- Confocal Imaging: Benefits include improved signal-to-noise ratio and rejection of out-of-focus background fluorescence, which is critical for 3D cellular cluster analysis and colocalization studies [31].

- Widefield Imaging with Deconvolution: A software-based solution that can sharpen images and reveal signal over noise, though it requires considerable processing time and can suffer from probe bleaching [31].

Advanced systems like the ImageXpress HCS.ai with AgileOptix technology now combine multiple confocal geometries (pinhole and slit) with AI-enabled analysis software to address throughput and analysis challenges in 3D biology [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Spatial Transcriptomics Profiling of FFPE Tissues

This protocol is adapted from a study comparing imaging-based spatial transcriptomics platforms [28].

Step 1: Sample Preparation

- Use serial 5 μm sections of FFPE surgically resected tissue samples (e.g., lung adenocarcinoma, pleural mesothelioma) assembled in Tissue Microarrays (TMAs).

- Ensure samples represent different archive years (e.g., 2016-2022) to assess platform performance across tissue ages.

Step 2: Platform-Specific Processing

- Process serial TMA sections on each platform (CosMx, MERFISH, Xenium) according to manufacturers' instructions.

- Gene Panel Selection: Employ the best available immuno-oncology panel for each platform, ensuring a set of shared genes (e.g., 93 genes) for cross-platform comparison.

Step 3: Data Acquisition and Imaging

- CosMx: Select multiple non-overlapping Fields of View (FOVs) of 545 μm × 545 μm within tissue cores.

- MERFISH & Xenium: Image the entire mounted tissue area as per standard protocols.

Step 4: Cell Segmentation and Transcript Counting

- Apply each platform's proprietary cell segmentation algorithm (e.g., unimodal vs. multimodal segmentation in Xenium).

- Generate raw transcript count matrices and cell boundary coordinates.

Step 5: Quality Control and Filtering

- Filter cells based on platform-specific recommendations:

- CosMx: Remove cells with <30 transcripts and those with an area 5x larger than the geometric mean of all cell areas.

- MERFISH & Xenium: Remove cells with <10 transcripts.

- Assess signal-to-background using negative control and blank probes.

- Filter cells based on platform-specific recommendations:

Step 6: Data Analysis and Cross-Platform Validation

- Compare transcripts per cell and unique genes per cell, normalized for panel size.

- Validate spatial data and cell type annotations against orthogonal methods: Bulk RNA-seq, GeoMx Digital Spatial Profiling, multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF), and H&E staining from serial sections.

Spatial Transcriptomics Workflow for FFPE Samples

Protocol: Repurposing High-Content Imaging Data for Predictive Modeling

This protocol enables the prediction of compound activity in orthogonal assays using data from a single high-throughput imaging assay [29].

Step 1: Conduct a Primary High-Throughput Imaging (HTI) Screen

- Perform a standard HTI assay (e.g., a three-channel microscopy-based screen for glucocorticoid receptor translocation).

- Use a diverse compound library to ensure broad coverage of chemical and morphological space.

Step 2: Extract Image-Based Fingerprints

- Use image analysis software (e.g., CellProfiler) to extract a multi-dimensional feature vector for each cell.

- Capture general morphology, shape, intensity, and patterning of fluorescent markers (e.g., 842 features per cell).

- Normalize each feature using the mean and standard deviation of negative controls on each plate.

- For each compound, compute the median value for each feature across all cells to generate a single, representative image-based fingerprint.

Step 3: Integrate Bioactivity Data from Orthogonal Assays

- Collate existing bioactivity data (e.g., IC50, active/inactive labels) for the screened compounds from assays of interest (Y).

- This creates a compound-by-activity matrix for model training.

Step 4: Train Predictive Machine Learning Models

- Employ supervised machine learning to predict bioactivity (Y) from image-based fingerprints (X).

- Model Options:

- Bayesian Matrix Factorization (e.g., Macau): A multitask method suitable for modeling multiple related assays jointly, which provides uncertainty estimates and can incorporate side information.

- Multitask Deep Neural Networks (DNNs): A nonlinear approach that uses shared hidden layers to learn a common representation across multiple prediction tasks (assays). Use regularization (e.g., dropout, early stopping) to prevent overfitting.

Step 5: Model Validation and Compound Selection

- Validate model performance using cross-validation or a held-out test set.

- Use high-quality models to predict activity for new compounds and select top candidates for in-vitro testing in the orthogonal assay.

Workflow for Repurposing HCI Data via Machine Learning

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Core Technology Platforms

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| FFPE Tissue Sections | Preserved tissue samples for spatial -omics; standard in pathology archives. | Profiling tumor microenvironments in translational research [28]. |

| Validated Antibody Panels | Detection of specific proteins in multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF). | Orthogonal validation of cell type annotations from spatial transcriptomics [28]. |

| CellProfiler Software | Open-source platform for automated image analysis and feature extraction. | Generating image-based compound fingerprints from high-content screens [29]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Kits & Reagents | Enable library preparation, target enrichment, and sequencing for functional genomics. | Transcriptomics, variant detection, and CRISPR screen validation [27]. |

| High-Quality Multiwell Plates | Standardized plates with flat, optical-quality bottoms for automated microscopy. | Ensuring consistent image quality and reliable autofocus in HCS [31]. |

| Commercial scRNA-seq Kits | Integrated reagents and protocols for single-cell RNA library preparation. | Generating benchmark datasets for cell atlas construction [25]. |

Phenotypic screening has historically been a powerful driver of first-in-class therapeutic discoveries, identifying compounds based on functional outcomes in complex biological systems without requiring prior knowledge of the specific molecular target [1]. However, a significant challenge of this approach is target deconvolution—the subsequent process of identifying the precise molecular mechanisms through which a hit compound exerts its effect [1]. Modern drug discovery is increasingly addressing this challenge by integrating multi-omics technologies—including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—into phenotypic screening workflows.

This integration provides a comprehensive molecular context, transforming observational data into mechanistic understanding. By layering multiple biological data types, researchers can now move beyond simply observing that a compound works to understanding how it works at a systems level, thereby accelerating target identification, validation, and rational drug optimization [32] [33].

Multi-Omics Technologies: Definitions and Contributions to Phenotypic Context

Each omics layer provides a distinct and complementary perspective on cellular activity. When combined, they offer a powerful framework for interpreting phenotypic observations.

Transcriptomics involves the study of all RNA transcripts in a cell population, including mRNA and non-coding RNAs. It reveals how genetic information is dynamically expressed in response to compound treatment or disease state [33]. In phenotypic screening, transcriptomic profiling can identify upstream regulatory networks and pathways affected by active compounds, providing early clues about mechanism of action.

Proteomics focuses on the large-scale study of proteins, including their expression levels, post-translational modifications, and interactions. As proteins are the primary functional actors in cells, proteomic data offers a more direct correlation with phenotypic outcomes than transcriptomic data alone [33]. Advanced proteomic techniques, particularly mass spectrometry-based methods, can quantify thousands of proteins, revealing drug-induced changes in cellular signaling pathways, protein complexes, and enzymatic activities [33].

Metabolomics involves the systematic study of small molecule metabolites, which represent the ultimate functional readout of cellular processes. Metabolomic profiling provides a snapshot of the biochemical activity and physiological state of a cell or tissue [33]. In phenotypic screening, metabolomics can reveal immediate functional consequences of compound treatment, such as disruptions in energy metabolism, signaling lipid networks, or biosynthetic pathways.

Technical Specifications of Major Multi-Omics Platforms

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Multi-Omics Platform Technologies

| Technology Type | Key Platforms/Methods | Primary Output | Key Applications in Phenotypic Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics | RNA-Seq, scRNA-Seq | Gene expression profiles, differential expression | Identifying pathway activation, regulatory networks, and cellular responses [33] |

| Proteomics | Mass spectrometry, affinity proteomics, protein chips | Protein identification, quantification, and modification status | Target deconvolution, understanding functional protein complexes and signaling [33] |

| Metabolomics | LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR | Identification and quantification of small molecule metabolites | Revealing immediate functional consequences of treatment on biochemical pathways [33] |

| Spatial Multi-Omics | Spatial transcriptomics, multiplexed imaging | Tissue localization of molecular signatures | Preserving tissue architecture context for phenotypic analysis [34] |

Experimental Design and Workflows for Multi-Omics Integration

Successfully integrating multi-omics data into phenotypic screening requires careful experimental design and execution. The following workflow outlines a standardized approach for generating high-quality, integrable multi-omics datasets.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Integrated Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis for Mechanism Elucidation

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating molecular mechanisms of stress tolerance, demonstrating how transcriptomic and proteomic data can be combined to uncover conserved pathways relevant to phenotypic outcomes [35].

Sample Preparation: Treat experimental models (e.g., cell lines, tissues) with compounds identified in phenotypic screens alongside appropriate controls. Use sufficient biological replicates (typically n≥3) to ensure statistical power.

Parallel Nucleic Acid and Protein Extraction: Isolate both RNA and protein from the same biological samples using validated extraction kits that preserve molecular integrity.

Transcriptomic Profiling: Conduct RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) using standard protocols including library preparation, cluster generation, and sequencing on platforms such as Illumina. Generate at least 20 million reads per sample for robust quantification.

Proteomic Analysis: Perform protein digestion and analysis using tandem mass spectrometry (Tandem MS). Utilize liquid chromatography separation followed by mass spectrometric detection and database searching for protein identification and quantification.

Data Integration and Analysis: Process transcriptomic and proteomic data through bioinformatic pipelines for normalization, differential expression analysis, and pathway enrichment. Identify concordant and discordant features between transcript and protein levels to distinguish transcriptional from post-transcriptional regulation [35].

Protocol 2: Multi-Omics for Biomarker Discovery and Patient Stratification

This protocol leverages multi-omics data to identify predictive biomarkers that can stratify patient populations for targeted therapies, enhancing the translational impact of phenotypic screening [32].

Cohort Selection: Define well-characterized patient cohorts representing different disease subtypes or treatment response categories.

Multi-Omics Profiling: Generate comprehensive genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic datasets from patient-derived samples, ensuring standardized processing across all platforms.

Data Integration: Apply computational integration methods to identify multi-omics signatures that correlate with clinical outcomes or treatment responses.

Biomarker Validation: Confirm candidate biomarkers in independent validation cohorts using targeted assays suitable for clinical implementation.

Visualizing the Multi-Omics Integration Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between phenotypic screening and multi-omics data integration for comprehensive mechanism elucidation:

Case Studies: Multi-Omics in Action

Elucidating Immunomodulatory Drug Mechanisms

The discovery and optimization of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) such as thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide exemplifies the power of combining phenotypic screening with subsequent molecular investigation. These compounds were initially identified through phenotypic screening for their ability to inhibit tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production, with second-generation analogs optimized through functional assays [1].

Critical mechanistic insights came only later through integrated molecular approaches that identified cereblon (CRBN) as the primary molecular target. Multi-omics analyses revealed that IMiDs binding to cereblon alters the substrate specificity of the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, leading to targeted degradation of specific transcription factors including IKZF1 (Ikaros) and IKZF3 (Aiolos) [1]. This mechanistic understanding, achieved through proteomic and transcriptomic profiling, not only explained the anti-myeloma activity of these drugs but also revealed a correlation between cereblon expression levels and clinical response, with responders showing approximately threefold higher cereblon expression compared to non-responders [1].

Enhancing Plant Stress Tolerance - A Translational Model

A robust example of integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analysis comes from plant biology, where researchers investigated the molecular mechanisms by which carbon-based nanomaterials (CBNs) enhance salt tolerance in tomato plants [35]. This study exemplifies how multi-omics integration can decode complex phenotypic responses.

Researchers combined RNA-Seq (transcriptomics) and tandem mass spectrometry (proteomics) to analyze tomato seedlings under salt stress with and without CBN treatment. Their integrated analysis revealed that exposure to carbon nanotubes resulted in complete restoration of expression for 358 proteins and partial restoration for 697 proteins that had been disrupted by salt stress [35].

The study identified that the elevated salt tolerance phenotype in CBN-treated plants was associated with activation of specific signaling pathways, including MAPK and inositol signaling, enhanced ROS clearance, stimulation of hormonal and sugar metabolism, and regulation of water transport through aquaporins [35]. This comprehensive molecular understanding would not have been possible through single-omics approaches alone.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Implementing robust multi-omics studies requires specialized reagents, platforms, and computational resources. The following table details key solutions essential for generating and analyzing multi-omics data.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Integration

| Category | Specific Solution | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina RNA-Seq, scRNA-Seq | Transcriptome profiling at bulk and single-cell resolution [33] [34] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Tandem MS, LC-MS/MS | Protein identification, quantification, and post-translational modification analysis [35] [33] |

| Spatial Biology Tools | Multiplexed imaging, spatial transcriptomics platforms | Mapping molecular distributions within tissue architecture [34] |

| Cell Painting Reagents | CellPainting kit (JUMP-CP consortium) | Standardized morphological profiling for high-content phenotypic screening [22] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Network analysis software, AI/ML algorithms | Integrating heterogeneous omics datasets, identifying patterns and biomarkers [36] [32] [33] |

| Data Resources | Open-access multi-omics databases (e.g., GWAS, TCGA) | Reference datasets for cross-study validation and model training [32] [33] |

Comparative Analysis: Single-Omics vs. Multi-Omics Approaches

The value of multi-omics integration becomes evident when comparing its outputs to those achievable through single-omics approaches. The following diagram illustrates how multi-omics data reveals regulatory relationships across biological layers that are invisible to single-omics studies:

Performance Comparison: Single vs. Multi-Omics Approaches

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Single vs. Multi-Omics Approaches

| Analysis Aspect | Single-Omics Approach | Multi-Omics Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic Insight | Limited to one molecular layer; may miss regulatory cascades | Reveals cross-layer regulatory networks and feedback loops [36] [33] |

| Biomarker Discovery | Often yields correlative markers with limited causal understanding | Identifies functional biomarker panels with improved predictive power [32] [33] |

| Target Deconvolution | Frequently incomplete; challenging to distinguish direct from indirect effects | Enables comprehensive mapping of drug mechanisms and off-target effects [1] [32] |

| Patient Stratification | Limited resolution based on single data types | Enables fine-grained stratification using complementary molecular information [32] [33] |

| Technical Challenges | Simplified analysis but limited biological context | Requires advanced computational integration but provides systems-level understanding [36] [32] |

The integration of transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data layers represents a fundamental advancement in phenotypic screening research. By adding rich molecular context to functional observations, multi-omics approaches address the critical bottleneck of target deconvolution while providing a systems-level understanding of compound mechanisms [1] [32].

The future of this field lies in further technological refinements, particularly in single-cell and spatial multi-omics that preserve cellular heterogeneity and tissue architecture [34], and increasingly sophisticated AI-driven integration methods that can extract biologically meaningful patterns from these complex datasets [32] [33]. As these technologies become more accessible and standardized, multi-omics integration will undoubtedly become an indispensable component of the phenotypic screening workflow, accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics and biomarkers across diverse disease areas.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is fundamentally reshaping phenotypic screening in drug discovery. This revolution addresses a central challenge in pharmaceutical research: efficiently extracting meaningful biological insights from complex, high-dimensional data. Modern phenotypic screening generates vast datasets, particularly from high-content imaging, which transcend human analytical capacity. AI and ML algorithms are now enabling researchers to not only analyze this data at unprecedented scale and speed but also to deconvolute mechanisms of action (MoA) and identify high-quality hits with improved efficiency. This comparative analysis examines how different AI-driven platforms and methodologies are performing across these critical tasks, providing researchers with a practical framework for evaluating technologies in this rapidly evolving landscape.

The transition to AI-powered workflows represents a significant paradigm shift from traditional approaches. Where conventional methods relied on simplistic readouts and manual analysis, AI platforms can process complex morphological profiles from cellular images, link these profiles to biological functions, and predict compound activity with increasing accuracy. This review synthesizes experimental data and performance metrics from current platforms, offering an objective comparison of their capabilities in image analysis, MoA elucidation, and hit identification—the three pillars of modern phenotypic screening.

Comparative Analysis of AI Platforms and Performance

Platform Approaches and Technological Differentiators

Table 1: Leading AI-Driven Phenotypic Screening Platforms and Their Core Technologies

| Platform/Company | Core AI Methodology | Primary Screening Focus | Key Technological Differentiators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recursion Pharmaceuticals [37] | Deep Learning on Cellular Imagery | Phenomic profiling & MoA deconvolution | Automated high-content imaging combined with deep learning models to detect subtle phenotypic changes |

| Exscientia [37] | Generative AI & Centaur Chemist | Hit Identification & Optimization | End-to-end AI-integrated design-make-test-analyze cycles; patient-derived biology integration |

| Insilico Medicine [37] | Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Target ID & Hit Generation | Generative chemistry for novel molecular structure design; deep learning on biological data |

| Schrödinger [37] | Physics-Informed ML & Molecular Simulation | Hit Identification & Optimization | Hybrid approach combining physics-based molecular modeling with machine learning |

| BenevolentAI [37] | Knowledge Graphs & ML | Target Identification & Validation | AI-driven mining of scientific literature and biomedical data to hypothesize novel targets |

The technological landscape for AI in phenotypic screening is diverse, with platforms employing distinct approaches to address key challenges. Recursion Pharmaceuticals has pioneered an approach that combines automated, high-throughput cellular imaging with deep learning models to quantify subtle phenotypic changes induced by genetic or compound perturbations [37]. This "phenomics-first" strategy generates massive, multidimensional datasets that enable the systematic classification of MoAs. Exscientia's platform exemplifies the "Centaur Chemist" approach, which strategically integrates algorithmic intelligence with human domain expertise to iteratively design, synthesize, and test novel compounds [37]. Their acquisition of Allcyte in 2021 further enhanced this by incorporating high-content phenotypic screening of AI-designed compounds on actual patient tumor samples, ensuring translational relevance [37].

Another prominent approach is exemplified by Insilico Medicine, which utilizes generative adversarial networks (GANs) and other deep learning models for de novo molecular design [37]. Their platform has demonstrated the ability to accelerate the early drug discovery timeline, progressing from target identification to Phase I trials for an idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis drug candidate in just 18 months—a fraction of the traditional 4-6 year timeline [37]. In contrast, Schrödinger employs a physics-enabled design strategy that integrates molecular simulations based on fundamental physical principles with machine learning [37]. This hybrid approach aims to improve the accuracy of predicting molecular behavior, as evidenced by the advancement of its TYK2 inhibitor, zasocitinib, into Phase III clinical trials [37].

Quantitative Performance Metrics in Hit Identification

A critical measure of an AI platform's utility is its performance in identifying biologically active compounds, or "hits." However, comparing hit rates requires careful consideration of the discovery context and chemical novelty.

Table 2: Experimentally Validated Hit Rates for AI Platforms in Hit Identification Campaigns

| AI Model/Platform | Reported Hit Rate | Therapeutic Target(s) | Activity Concentration (μM) | Key Experimental Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChemPrint (Model Medicines) [38] | 46% (41 compounds tested) | AXL, BRD4 | ≤20 | In silico prediction followed by in vitro validation of binding affinity (Kd) and biological activity |

| Schrödinger [38] | 26% (Claimed) | Not Specified | ≤30 (Data incomplete) | Physics-based molecular simulation and ML for virtual screening; hit confirmation in biochemical assays |

| Insilico Medicine [38] | 23% (Claimed) | Not Specified | ≤20 | Generative AI for novel molecular design; experimental validation in target-specific assays |

| LSTM RNN Model [38] | 43% | Context-Dependent | ≤20 | Deep learning model trained on chemical data; output compounds tested for bioactivity |

| GRU RNN Model [38] | 88% | Context-Dependent | ≤20 | Gated recurrent unit model for compound prediction; experimental hit confirmation |

The hit rates reported in Table 2 must be interpreted with an understanding of the "campaign type." Hit Identification—discovering entirely novel bioactive chemistry for a target—is the most challenging phase. Hit Expansion (exploring chemical space around a known hit) and Hit Optimization (refining a well-defined lead) typically yield higher success rates as they operate within a better-understood structure-activity relationship (SAR) framework [38]. The data in Table 2 focuses on the more challenging Hit Identification campaigns.

Strikingly, the ChemPrint platform demonstrated a 46% hit rate (19 out of 41 predicted compounds showed novel biological activity in vitro), alongside strong chemical novelty, with Tanimoto similarity scores of 0.3-0.4 to known bioactive compounds in databases like ChEMBL [38]. This suggests an ability to explore novel chemical space effectively. While the GRU RNN Model claims an exceptional 88% hit rate, the lack of available training set data makes a full assessment of its novelty difficult [38]. It is crucial for researchers to assess not only the hit rate but also the chemical novelty and diversity of the identified hits to gauge a model's capacity for true innovation beyond rediscovering known chemistry.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Workflow for AI-Enhanced Phenotypic Screening and Hit Deconvolution

The following diagram illustrates a generalized, integrated workflow for an AI-driven phenotypic screening campaign, from initial imaging through to MoA elucidation and hit validation.

This workflow begins with the treatment of a biologically relevant cell model (e.g., primary cells, patient-derived cells, or engineered reporter lines) with compound libraries. The cells undergo high-content imaging using automated microscopes, capturing multichannel, high-resolution images [37]. The next critical step is morphological feature extraction, where software quantifies thousands of features—such as cell shape, texture, organelle distribution, and intensity—from the segmented images [37] [39].

These features are aggregated into a multivariate phenotypic profile for each treatment condition. This profile is then processed by AI models, most commonly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) that can learn directly from image data, or Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) that can model complex relationships within the data [37] [40]. These models classify profiles, predict MoAs by comparing them to profiles induced by compounds with known mechanisms, and identify outliers that represent novel biology [37]. This analysis enables hit identification and prioritization based on both the strength of the phenotypic response and the novelty or interest of the predicted MoA.

The prioritized compounds proceed to experimental validation, which includes orthogonal assays to confirm target binding (e.g., SPR, FRET) and functional biological activity (e.g., cell proliferation, reporter gene assays) at a defined concentration threshold, typically ≤20 μM for initial hits [38]. Successful validation leads to Mechanism of Action Elucidation, which may involve further experimental work such as genetic knockdown (CRISPR) or proteomics to confirm the AI-predicted target pathway. A key feature of this workflow is that the validation data feeds back into the AI model, creating a closed-loop design-make-test-analyze cycle that continuously refines its predictive power [37].

AI Model Selection: The "Goldilocks Paradigm" for Drug Discovery

Choosing the right machine learning algorithm is crucial and depends heavily on the size and diversity of the available dataset. The "Goldilocks Paradigm" provides a heuristic for model selection based on empirical comparisons [41].

As illustrated, Few-Shot Learning Classification (FSLC) models tend to outperform both classical ML and transformers when the training set is very small (fewer than 50 molecules) [41]. For medium-sized datasets (50-240 molecules), transformer models like MolBART, which leverage transfer learning from pre-training on large chemical corpora, show superior performance, especially when the dataset is structurally diverse (containing many unique Murcko scaffolds) [41]. Finally, for larger datasets (exceeding 240 molecules), classical machine learning models such as Support Vector Classification (SVC) or Random Forest often provide the best predictive power, as they can effectively learn from the ample data without the overhead of complex model architectures [41]. This paradigm provides a practical guide for researchers to match their data resources with the most suitable AI methodology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Successful execution of an AI-driven phenotypic screening campaign relies on a suite of specialized research reagents and computational tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools