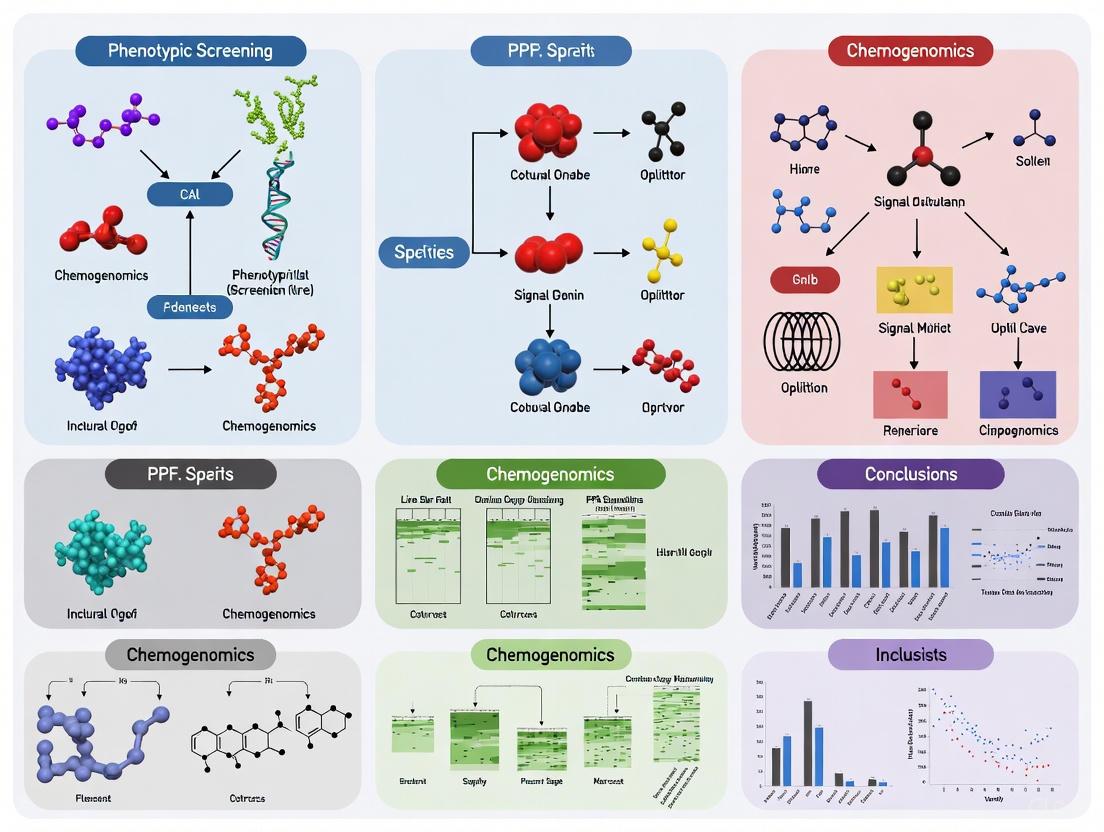

Phenotypic Screening Meets Chemogenomics: A Modern Strategy for Target Deconvolution and Drug Discovery

This article explores the powerful synergy between phenotypic screening and chemogenomics, a strategy that is reshaping modern drug discovery.

Phenotypic Screening Meets Chemogenomics: A Modern Strategy for Target Deconvolution and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the powerful synergy between phenotypic screening and chemogenomics, a strategy that is reshaping modern drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of forward and reverse chemogenomics approaches and their application in deconvoluting complex mechanisms of action. The content delves into practical methodologies for building and annotating chemogenomic libraries, supported by case studies in areas like antifilarial drug development and traditional medicine. It also addresses key challenges in phenotypic screening, such as managing polypharmacology and distinguishing specific from non-specific effects, and examines how emerging technologies like high-content imaging and machine learning are validating and enhancing these approaches. The article concludes by synthesizing how this integrated strategy accelerates the identification of novel drug targets and bioactive compounds, offering a robust framework for tackling complex diseases.

The Chemogenomics Foundation: Bridging Phenotypes and Molecular Targets

Chemogenomics represents a systematic approach to drug discovery that involves screening targeted libraries of small molecules against families of related biological targets, such as G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), kinases, nuclear receptors, and proteases [1] [2]. This interdisciplinary field operates on the fundamental principle that similar receptors bind similar ligands, thereby allowing for the efficient exploration of chemical and biological spaces in parallel [1]. The strategy marks a paradigm shift from traditional single-target drug discovery toward a cross-receptor view, where receptors are no longer investigated as single entities but as grouped sets of related proteins that can be explored systematically [1].

Within the context of phenotypic screening, chemogenomics provides a powerful framework for target identification and mechanism deconvolution [3]. By using small molecules as probes to characterize proteome functions, researchers can observe phenotype modifications upon compound treatment and subsequently associate these changes with specific molecular targets and pathways [2]. This approach is particularly valuable for investigating complex diseases like cancer, neurological disorders, and diabetes, which often result from multiple molecular abnormalities rather than single defects [3].

Key Applications in Drug Discovery

Target Identification and Validation

Chemogenomics enables the systematic identification of novel drug targets through both forward and reverse approaches [4] [2]. Forward chemogenomics begins with a phenotypic screen to identify compounds that induce a desired cellular response, followed by target identification for the active compounds [2]. Conversely, reverse chemogenomics starts with a specific protein target and screens for modulators, then characterizes the phenotypic effects of these modulators in cellular or organismal models [4] [2]. This bidirectional strategy has proven particularly effective for target classes with well-characterized binding sites, such as GPCRs and kinases [1].

Mechanism of Action (MOA) Studies

Chemogenomic approaches have been successfully applied to determine the mechanism of action for compounds derived from traditional medicines, including Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ayurveda [2]. By creating databases containing chemical structures and associated phenotypic effects, researchers can use computational target prediction to establish links between traditional remedies and modern molecular targets [2]. For example, compounds from the "toning and replenishing medicine" class of TCM have been linked to targets such as sodium-glucose transport proteins and PTP1B, providing mechanistic insights for their hypoglycemic activity [2].

Polypharmacology Profiling

The systematic nature of chemogenomics makes it ideally suited for investigating polypharmacology—the ability of compounds to interact with multiple targets [3]. By profiling compounds against entire target families rather than individual proteins, researchers can identify unexpected "off-target" interactions that may contribute to both efficacy and toxicity [4]. This comprehensive profiling is especially valuable for complex diseases where modulation of multiple targets may be therapeutically advantageous [3].

Table 1: Representative Chemogenomics Libraries and Their Applications

| Library Name | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GlaxoSmithKline Biologically Diverse Compound Set | Targets GPCRs & kinases with varied mechanisms [4] | Phenotypic screening, target identification [4] | Broad biological and chemical diversity [4] |

| Pfizer Chemogenomic Library | Target-specific pharmacological probes [4] | Lead identification, selectivity profiling [4] | Focus on ion channels, GPCRs, and kinases [4] |

| Prestwick Chemical Library | FDA/EMA-approved drugs [4] | Repurposing, safety assessment [4] | High bioavailability and established safety profiles [4] |

| NCATS MIPE 3.0 | Oncology-focused, kinase inhibitor dominated [4] | Anticancer phenotype screening [4] | Designed for mechanism interrogation [4] |

| LOPAC1280 | Pharmacologically active compounds [4] | GPCR studies, phenotypic effects [4] | Commercial library with known biology [4] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Development of a Targeted Chemogenomics Library

Purpose: To create a targeted chemical library for phenotypic screening that represents a diverse panel of drug targets involved in various biological effects and diseases [3].

Materials and Reagents:

- Source databases (ChEMBL, KEGG, Gene Ontology, Disease Ontology) [3]

- Chemical structures in SMILES or SDF format [3]

- Scaffold analysis software (e.g., ScaffoldHunter) [3]

- Graph database platform (e.g., Neo4j) for data integration [3]

- Cell painting assay reagents for morphological profiling [3]

Procedure:

- Data Collection and Integration:

- Extract bioactivity data from ChEMBL database, including IC₅₀, Kᵢ, and EC₅₀ values [3]

- Incorporate pathway information from KEGG and biological process data from Gene Ontology [3]

- Integrate disease association data from Disease Ontology [3]

- Include morphological profiling data from Cell Painting experiments when available [3]

Chemical Structure Curation:

Scaffold Analysis and Diversity Assessment:

- Use ScaffoldHunter to classify compounds based on hierarchical scaffold decomposition [3]

- Identify representative core structures at different abstraction levels [3]

- Apply clustering algorithms to ensure structural diversity [3]

- Select final compounds to maximize target coverage while maintaining structural diversity [3]

Network Pharmacology Construction:

- Implement a graph database using Neo4j to integrate compounds, targets, pathways, and diseases [3]

- Establish relationships between chemical structures, protein targets, biological pathways, and disease associations [3]

- Enable query capabilities for identifying compounds associated with specific phenotypes [3]

Library Validation:

Diagram 1: Chemogenomics library development workflow illustrating the key stages from data collection to final library validation.

Protocol: Forward Chemogenomics Screening for Phenotypic Drug Discovery

Purpose: To identify novel drug targets by screening chemical compounds for specific phenotypic effects in cellular models [2].

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell line relevant to disease biology (e.g., U2OS cells for Cell Painting) [3]

- Chemical library (5000-30,000 compounds) [3] [4]

- Cell staining reagents for morphological profiling (Cell Painting assay) [3]

- High-content imaging system [3]

- Image analysis software (e.g., CellProfiler) [3]

Procedure:

- Assay Development:

Compound Screening:

Phenotypic Profiling:

Hit Identification:

Target Deconvolution:

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Chemogenomic Data Curation Workflow

High-quality data curation is essential for reliable chemogenomics studies. The following integrated workflow addresses both chemical and biological data quality [5]:

Chemical Structure Curation:

Bioactivity Data Processing:

Target Annotation:

Table 2: Common Data Sources for Chemogenomics Studies

| Data Type | Primary Sources | Key Applications | Quality Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structures | ChEMBL [3], PubChem [5], ChemSpider [5] | Library design, similarity searching | Error rates 0.1-8% require curation [5] |

| Bioactivity Data | ChEMBL [3], PDSP Ki Database [5] | QSAR modeling, target profiling | Mean pKi error ~0.44 units [5] |

| Target Information | UniProt, Gene Ontology [3], KEGG [3] | Pathway analysis, polypharmacology | Consistency in target identifiers [3] |

| Morphological Profiles | Cell Painting [3], Broad Bioimage Benchmark Collection [3] | Phenotypic screening, MOA studies | Feature selection and normalization [3] |

Network Pharmacology Analysis

The construction of a pharmacology network integrating drug-target-pathway-disease relationships enables systematic exploration of chemogenomics data [3]:

Graph Database Implementation:

Enrichment Analysis:

Morphological Profiling Integration:

Diagram 2: Network pharmacology relationships illustrating the connections between small molecules, their protein targets, biological pathways, and phenotypic outcomes.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomics Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database [3] | Bioactivity data repository | Contains >1.6M molecules with standardized bioactivity data; requires curation for optimal use [3] |

| Cell Painting Assay [3] | Morphological profiling | Provides 1,779+ morphological features; enables phenotypic comparison across compounds [3] |

| ScaffoldHunter [3] | Scaffold-based analysis | Hierarchical decomposition of compounds into scaffolds; enables diversity assessment [3] |

| RDKit [5] | Cheminformatics toolkit | Open-source platform for chemical curation and descriptor calculation [5] |

| Neo4j [3] | Graph database platform | Enables integration of heterogeneous data sources and network pharmacology analysis [3] |

| GPCR-Focused Library [1] | Target-class specific screening | Example: 30,000 compounds selected using neural network classification [1] |

| Kinase Inhibitor Set [4] | Targeted chemogenomics library | Enables systematic profiling of kinase family members; useful for polypharmacology studies [4] |

| ClusterProfiler [3] | Functional enrichment tool | Identifies overrepresented GO terms, KEGG pathways, and disease associations [3] |

Implementation Considerations

Data Quality and Reproducibility

The effectiveness of chemogenomics approaches depends heavily on data quality and reproducibility [5]. Studies have indicated error rates of 0.1-3.4% in chemical structures across public databases, with approximately 8% error rate in medicinal chemistry publications [5]. Furthermore, biological data reproducibility concerns have been raised, with one analysis finding only 20-25% consistency between published assertions and in-house findings [5]. Implementation of rigorous curation protocols, including chemical structure standardization, bioactivity data verification, and assay annotation, is essential for generating reliable results [5].

Integration with Phenotypic Screening

The combination of chemogenomics with advanced phenotypic screening technologies represents a powerful strategy for modern drug discovery [3]. High-content imaging approaches like Cell Painting generate multidimensional morphological profiles that can be connected to specific targets and pathways through chemogenomic databases [3]. This integration facilitates target identification for phenotypic hits and enables mechanism of action deconvolution by comparing unknown profiles with those of compounds with known targets [3].

Computational Infrastructure

Successful implementation of chemogenomics requires substantial computational infrastructure for data storage, integration, and analysis [3]. Graph databases have emerged as particularly valuable for representing the complex networks of relationships between compounds, targets, pathways, and phenotypes [3]. Additionally, machine learning approaches, including deep learning and support vector machines, are increasingly being applied to predict novel drug-target interactions and optimize compound properties across target families [4].

The resurgence of phenotypic screening in drug discovery has created a critical need for efficient target identification and mechanism deconvolution. Chemogenomics, the systematic screening of targeted chemical libraries against families of drug targets, provides a powerful framework to address this challenge [4] [2]. This approach operates at the intersection of chemical and biological spaces, using small molecules as probes to modulate and characterize proteome function [2]. Within phenotypic screening research, two complementary strategies have emerged: forward chemogenomics, which begins with a phenotype to identify molecular targets, and reverse chemogenomics, which starts with a specific protein target to validate phenotypic outcomes [4] [2]. This application note details the core principles, methodologies, and practical applications of both strategies to guide researchers in selecting and implementing appropriate approaches for their drug discovery programs.

Core Conceptual Distinctions

The fundamental distinction between forward and reverse chemogenomics lies in their starting points and directional workflows, each addressing different stages of the target identification and validation process.

Forward chemogenomics (also termed "classical" or "phenotype-first") investigates a specific phenotypic response without prior knowledge of the molecular mechanism involved. This approach identifies small molecules that produce a target phenotype, then uses these modulators as tools to identify the responsible proteins [2]. The major challenge lies in designing phenotypic assays that can efficiently transition from screening to target identification [2].

Reverse chemogenomics (or "target-first") begins with a specific protein target and identifies small molecules that perturb its function in vitro. Once modulators are identified, the molecule-induced phenotype is analyzed in cellular or whole-organism systems to confirm the target's role in a biological response [4] [2]. This approach resembles traditional target-based drug discovery but is enhanced by parallel screening capabilities across multiple targets within the same family [2].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Forward and Reverse Chemogenomics

| Parameter | Forward Chemogenomics | Reverse Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Observable phenotype | Known protein target |

| Primary Objective | Identify novel drug targets | Validate phenotypic function of known targets |

| Screening Approach | Phenotypic assays on compound libraries | Target-based assays (enzymatic, binding) |

| Key Challenge | Deconvoluting molecular target from phenotype | Translating in vitro activity to physiologically relevant phenotype |

| Information Yield | Novel target-phenotype associations | Target validation and mechanistic understanding |

| Ideal Application | Target discovery for complex or poorly understood diseases | Lead optimization, safety profiling, polypharmacology |

| Throughput Potential | Moderate (complex phenotypic readouts) | High (standardized target-focused assays) |

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow and fundamental differences between these two approaches:

Experimental Protocols

Forward Chemogenomics Protocol: Phenotype-Driven Target Discovery

Objective: Identify molecular targets responsible for a specific phenotypic response using small molecule probes.

Workflow Overview:

Phenotypic Assay Development

- Establish a robust, biologically relevant assay measuring the desired phenotype (e.g., inhibition of tumor growth, alteration of cell morphology, change in reporter gene expression)

- Implement appropriate controls and validation experiments to ensure assay specificity

- For high-content applications, incorporate morphological profiling technologies such as Cell Painting, which quantifies ~1,800 cellular features across multiple channels [6]

Compound Library Screening

- Select a diverse chemogenomic library covering broad target space (see Section 5: Research Reagent Solutions)

- Perform primary screening at appropriate concentrations (typically 1-10 µM) in biological triplicate

- Identify hit compounds producing the target phenotype using statistically rigorous thresholds (e.g., Z-score > 2, p-value < 0.01)

Target Deconvolution

- Employ one or more of the following target identification methods:

- Affinity-based Pull-down: Conjugate hit compound to solid support (agarose beads) or affinity tag (biotin); incubate with cell lysate; purify and identify bound proteins via SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry [7]

- Photoaffinity Labeling: Incorporate photoreactive group (e.g., diazirine) into compound structure; upon UV irradiation, form covalent bonds with target proteins; isolate and identify via mass spectrometry [7]

- Label-free Methods: Utilize techniques such as native mass spectrometry to directly detect protein-ligand complexes in mixtures without chemical modification [8]

- Genetic Approaches: Generate drug-resistant clones and identify mutated genes; or use gene expression profiling to infer mechanisms [8]

- Employ one or more of the following target identification methods:

Target Validation

- Confirm functional relevance using orthogonal approaches (genetic knockdown, selective inhibitors)

- Demonstrate dose-dependent correlation between target engagement and phenotypic response

- Establish specificity through counter-screens against related targets

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key experimental stages:

Reverse Chemogenomics Protocol: Target-Driven Phenotypic Validation

Objective: Characterize the phenotypic effects of compounds known to interact with a specific protein target.

Workflow Overview:

Target Selection and Assay Development

- Select therapeutically relevant protein target (e.g., kinase, GPCR, ion channel)

- Develop in vitro binding or functional assay (e.g., enzymatic activity, receptor binding)

- Validate assay with known reference compounds

Compound Screening and Profiling

- Screen focused chemical libraries against the target using the in vitro assay

- Confirm hits in dose-response experiments to determine potency (IC50, Ki values)

- Select compounds with desired potency and selectivity profile for further study

Cellular Phenotypic Screening

- Test active compounds in disease-relevant cellular models

- Incorporate multiple phenotypic readouts where possible (viability, morphology, signaling pathways, functional responses)

- For compounds showing concordant in vitro and cellular activity, proceed to mechanistic studies

Mechanism and Pathway Analysis

- Use chemoproteomic approaches to identify potential off-target interactions

- Employ pathway analysis tools to connect target modulation to observed phenotype

- Validate mechanism through genetic approaches (CRISPR, RNAi) targeting the protein of interest

Lead Optimization

- Use structure-activity relationship (SAR) data to optimize compounds for both target potency and phenotypic efficacy

- Employ parallel screening across multiple related targets to understand selectivity implications

Table 2: Comparison of Target Deconvolution Methods in Forward Chemogenomics

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Throughput | Key Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Pull-down | Compound-tag conjugation; affinity purification | Moderate | Medium | Chemical handle for conjugation; sufficient compound |

| Photoaffinity Labeling | UV-induced covalent crosslinking; purification & MS | High | Medium | Specialized probe synthesis; optimization of crosslinking |

| Native Mass Spectrometry | Direct detection of protein-ligand complexes | High | Medium-High | Protein mixtures; instrument capability |

| CETSA | Thermal stability shift upon ligand binding | Moderate-High | Medium | Proteomic capabilities; thermal shift platform |

| Genetic Resistance | Selection of resistant mutants; gene identification | High | Low | Suitable selection pressure; genetic system |

Applications in Drug Discovery

Determining Mechanisms of Action

Forward chemogenomics has proven particularly valuable for determining mechanisms of action (MOA) for compounds with unknown targets, including natural products and traditional medicines [2]. For example, this approach has been applied to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and Ayurvedic formulations, where target prediction programs can identify potential protein targets linked to observed therapeutic phenotypes [2]. In one case study, the therapeutic class of "toning and replenishing medicine" was evaluated, with sodium-glucose transport proteins and PTP1B identified as targets relevant to the hypoglycemic phenotype [2].

Identifying Novel Drug Targets

Chemogenomics enables systematic discovery of novel therapeutic targets through its comprehensive approach to mapping chemical-biological interactions. In antibacterial development, researchers have leveraged existing ligand libraries for enzymes in essential bacterial pathways (e.g., the peptidoglycan synthesis mur ligase family) to identify new targets for known ligands [2]. This approach successfully predicted murC and murE ligases as targets for broad-spectrum Gram-negative inhibitors, demonstrating how chemogenomic similarity principles can expand target space [2].

COVID-19 Drug Discovery Applications

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the utility of chemogenomic approaches for rapid drug repurposing. Both forward and reverse strategies were deployed to identify potential SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics, with computational chemogenomics playing a particularly important role in prioritizing compounds for experimental testing [9]. Ligand-based similarity searching and target prediction models enabled rapid identification of existing drugs with potential activity against coronavirus targets such as the main protease (Mpro) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomics Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Key Applications | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pfizer Chemogenomic Library | Compound Library | Reverse chemogenomics, target family screening | Focused on ion channels, GPCRs, kinases; broad biological diversity |

| GSK Biologically Diverse Compound Set | Compound Library | Phenotypic screening, forward chemogenomics | Targets GPCRs & kinases with varied mechanisms |

| Prestwick Chemical Library | Compound Library | Drug repurposing, safety profiling | FDA/EMA-approved drugs; known safety profiles |

| MIPE 3.0 (NCATS) | Compound Library | Oncology-focused screening, mechanism interrogation | Kinase inhibitor dominated; anticancer phenotypes |

| Cell Painting Assay | Phenotypic Profiling | Forward chemogenomics, mechanism deconvolution | ~1,800 morphological features; high-content imaging |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity Database | Target prediction, chemogenomic modeling | >2.4M compounds; >20M bioactivities; >15K targets |

| Native Mass Spectrometry | Analytical Platform | Label-free target identification | Direct detection of protein-ligand complexes |

| Photoaffinity Probes | Chemical Tools | Target identification (forward chemogenomics) | Diazirine, benzophenone, or arylazide photoreactive groups |

Forward and reverse chemogenomics represent complementary paradigms in modern drug discovery, particularly within phenotypic screening workflows. Forward chemogenomics excels at novel target discovery for complex phenotypes, while reverse chemogenomics provides a systematic approach for validating target-phenotype relationships and understanding polypharmacology. The integration of both approaches, supported by specialized chemical libraries and advanced target identification technologies, creates a powerful framework for accelerating the development of new therapeutics. As chemogenomic databases expand and analytical technologies advance, these systematic approaches will play an increasingly important role in bridging the gap between phenotypic observations and molecular mechanisms in drug discovery.

The druggable genome comprises the subset of human genes encoding proteins that can be bound and modulated by drug-like molecules. Current estimates suggest that of the approximately 20,000 protein-coding genes in the human genome, only about 4,000-4,500 belong to this druggable category [10] [11] [12]. Despite this substantial potential target space, existing medicines act on only a few hundred proteins, leaving the majority of the druggable genome unexplored therapeutic territory [10]. This untapped potential is particularly concentrated within three key protein families: G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), ion channels, and protein kinases [10].

Chemogenomics represents a strategic framework that expands this universe by using chemical compounds as probes to systematically understand and target biological systems. This approach utilizes defined compound libraries to interrogate protein families based on shared structural or functional features, thereby bridging the gap between genetic information and therapeutic intervention. By creating focused chemical libraries tailored to specific protein families or disease contexts, chemogenomics provides researchers with powerful tools to illuminate previously undruggable or understudied targets, ultimately accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic candidates [13].

Quantitative Landscape of the Druggable Genome

Table 1: Estimations and Categorizations of the Druggable Genome

| Category | Gene Count | Description | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Protein-Coding Genes | ~20,300-20,360 | The full complement of human protein-coding genes [11] [12]. | Baseline for assessing druggable proportion. |

| Total Druggable Genome | ~4,479-4,600 | Genes encoding proteins predicted to bind drug-like molecules [11] [10]. | Represents ~22% of the protein-coding genome. |

| Tier 1: Clinically Validated | 1,427 | Targets of approved drugs and clinical-phase candidates [11]. | Strongest human evidence for druggability. |

| Understudied Druggable Proteins | ~1,500 | Members of key families (GPCRs, ion channels, kinases) with unknown functions [10]. | Primary focus of the IDG program; high potential for novel discoveries. |

The druggable genome is not a static concept but has evolved significantly over the past two decades. Early work by Hopkins and Groom identified approximately 3,000 druggable proteins based on sequence and structural similarity to targets of existing drugs [11] [12]. Subsequent research has expanded this catalog by incorporating targets of newly approved drugs (including biologics), clinical-stage candidates, and proteins with confirmed binding to drug-like small molecules [11] [12]. This expanded view recognizes that druggability extends beyond traditional small molecules to include modalities such as monoclonal antibodies and other biotherapeutics, which now constitute a substantial portion of new drug approvals [11].

A critical insight is that "druggable does not equal drugged" [12]. While the druggable genome is substantial, a significant portion remains unexplored, particularly in the context of human disease biology. The NIH's Illuminating the Druggable Genome (IDG) program was established specifically to address this gap by systematically generating knowledge and tools for understudied proteins from the three key druggable families, thereby building a foundation for future therapeutic development [10].

Chemogenomics Library Design and Applications

Strategic Library Assembly for Phenotypic Screening

Chemogenomics libraries are strategically assembled collections of compounds designed to probe specific biological questions. In the context of phenotypic screening, these libraries can be enriched to increase the probability of identifying hits with desired polypharmacological profiles. One advanced approach involves tailoring libraries to a specific disease context, such as glioblastoma (GBM), through a multi-step process:

- Target Identification: Analysis of tumor genomic data (e.g., from The Cancer Genome Atlas) identifies differentially expressed genes and somatic mutations specific to the disease [13].

- Network Analysis: The implicated genes are mapped onto large-scale human protein-protein interaction networks to construct a disease-specific subnet, highlighting key pathways and complexes [13].

- Druggable Site Identification: Protein structures for network components are analyzed to classify and identify druggable binding pockets at catalytic sites, protein-protein interfaces, or allosteric sites [13].

- Virtual Screening: An in-house compound library is computationally docked against the identified druggable binding sites. Compounds predicted to bind multiple targets within the network are prioritized for experimental screening [13].

This rational enrichment process ensures that the chemical library is biased toward compounds capable of engaging multiple disease-relevant targets, increasing the likelihood of discovering agents with selective polypharmacology – the desired ability to modulate a collection of targets across different signaling pathways specific to the disease state without undue toxicity [13].

Integration with Phenotypic Screening

The power of chemogenomics is fully realized when these designed libraries are deployed in biologically complex phenotypic assays. This combination helps transcend the limitations of traditional target-centric approaches. For example, sophisticated phenotypic assays now include:

- Three-dimensional spheroids and organoids that better recapitulate the tumor microenvironment and its signaling complexities compared to traditional 2D monolayers [13].

- High-content imaging and single-cell technologies that capture subtle, disease-relevant phenotypes at scale [14].

- Multiplexed assays, such as the Cell Painting assay, which uses fluorescent dyes to visualize multiple cellular components, generating rich morphological profiles that serve as a high-dimensional readout of cellular state [14].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomics and Phenotypic Screening

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Relevance to Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Pharos (IDG Knowledge Base) | Centralized data portal for understudied targets from the IDG program [10]. | Provides integrated knowledge on target biology, tractability, and ligands to prioritize research. |

| Cell Painting Assay | High-content morphological profiling using multiplexed fluorescent dyes [14]. | Enables unbiased characterization of compound effects; identifies compounds inducing desired phenotypic patterns. |

| CRISPR-based Functional Genomic Libraries | Tools for systematic gene perturbation (e.g., knockout, activation) [15]. | Validates novel drug targets and identifies synthetic lethal interactions (e.g., WRN in MSI-high cancers). |

| Chemogenomic Tool Compound Libraries | Collections of well-annotated, target-specific chemical probes [15]. | Used for target hypothesis generation and drug repurposing in phenotypic screens. |

| Thermal Proteome Profiling (TPP) | Proteome-wide method to monitor protein thermal stability changes upon compound binding [13]. | Unbiased identification of a compound's direct and indirect protein targets in a complex cellular milieu. |

A significant challenge with traditional chemogenomic libraries is that they typically interrogate only 1,000-2,000 targets, a small fraction of the human genome, leaving many potential targets unaddressed [15]. This limitation underscores the need for continued expansion of chemical space coverage through the design and synthesis of novel compounds, such as those derived from diversity-oriented synthesis (DOS) [13].

Experimental Protocol: A Phenotypic Screening Workflow Using a Target-Enriched Chemogenomics Library

This protocol details the process of creating a target-enriched chemogenomics library and deploying it in a phenotypic screen, based on a validated approach for glioblastoma (GBM) spheroids [13]. The workflow integrates genomic data, computational filtering, and complex phenotypic assays to identify compounds with selective polypharmacology.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for a target-enriched phenotypic screen, from genomic data to lead compound identification.

Materials and Equipment

- Patient-derived GBM cells and relevant culture reagents.

- Normal control cells (e.g., primary astrocytes, CD34+ progenitor cells).

- In-house or commercially available compound library (~9,000 compounds used in the cited study).

- TCGA GBM genomic data (RNA-seq and mutation data).

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) structures for homology modeling.

- Molecular docking software (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide).

- Protein-protein interaction network data (e.g., from Rolland et al.).

- Low-attachment spheroid formation plates (e.g., Corning Ultra-Low Attachment).

- Cell viability assay kits (e.g., CellTiter-Glo 3D).

- Tube formation assay materials (Matrigel, brain endothelial cells).

- RNA sequencing and mass spectrometry facilities.

Procedure

Step 1: Target Identification and Library Enrichment

- Retrieve Genomic Data: Download and process GBM patient RNA sequencing and somatic mutation data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) or equivalent database [13].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Perform statistical analysis to identify genes significantly overexpressed in GBM tumors compared to normal samples (e.g., p < 0.001, FDR < 0.01, log2FC > 1) [13].

- Construct Disease Subnetwork: Map the list of overexpressed and mutated genes onto a consolidated human protein-protein interaction (PPI) network. Filter for proteins with at least one interaction to create a GBM-specific PPI subnetwork [13].

- Identify Druggable Binding Sites: For each protein in the GBM subnetwork, analyze available PDB structures or homology models to identify and classify druggable binding pockets (e.g., catalytic sites, protein-protein interaction interfaces, allosteric sites) [13].

- Virtual Screening: Dock each compound from your in-house library against all identified druggable binding sites. Use a knowledge-based scoring function (e.g., SVR-KB) to predict binding affinities [13].

- Compound Prioritization: Rank-order compounds based on their predicted ability to bind multiple targets within the GBM subnetwork. Select the top candidates (e.g., 47 compounds as in the cited study) for experimental validation [13].

Step 2: Phenotypic Screening in Disease-Relevant Models

- Culture Patient-Derived GBM Spheroids: Seed low-passage GBM cells in ultra-low attachment plates to form 3D spheroids. Allow spheroids to mature for 3-5 days [13].

- Compound Treatment: Treat GBM spheroids with the prioritized compounds across a range of concentrations (e.g., 1-100 µM). Include standard-of-care controls (e.g., temozolomide) and vehicle controls.

- Viability Assessment: After an appropriate incubation period (e.g., 72-120 hours), measure spheroid viability using a 3D-optimized ATP-based assay (e.g., CellTiter-Glo 3D). Calculate IC50 values for active compounds [13].

- Selectivity Counter-Screen: Treat non-malignant control cells (e.g., primary astrocytes in 2D culture or CD34+ progenitor cell spheroids) with active compounds. Confirm selective cytotoxicity toward GBM cells with minimal effect on normal cells [13].

Step 3: Secondary Phenotypic and Mechanistic Studies

- Functional Phenotypic Assays: Subject lead compounds to additional disease-relevant assays. For anti-angiogenic activity, perform a tube formation assay by seeding brain endothelial cells on Matrigel and quantifying the disruption of tubular networks upon compound treatment [13].

- Mechanism of Action Elucidation:

- RNA Sequencing: Treat GBM spheroids with the lead compound and perform RNA-seq. Analyze differential gene expression and pathway enrichment to infer the compound's biological effects and potential mechanisms [13].

- Target Engagement Validation: Perform thermal proteome profiling (TPP). Treat cells with the compound, subject them to a range of temperatures, and identify proteins with shifted thermal stability via mass spectrometry. This confirms direct physical engagement of the predicted multi-target portfolio within the cellular environment [13].

Data Integration and AI-Driven Discovery

The future of chemogenomics lies in the integration of multimodal data and the application of artificial intelligence. AI and machine learning models are now capable of fusing complex datasets—including high-content phenotypic data, transcriptomics, proteomics, and genomic information—to reveal patterns beyond human analytical capacity [14]. Platforms like Ardigen's PhenAID exemplify this trend, integrating cell morphology data from assays like Cell Painting with omics layers to identify phenotypic patterns correlated with mechanism of action, efficacy, or safety [14].

A key enabler for AI-driven discovery is the construction of comprehensive knowledge graphs that link annotations from the gene level down to individual protein residues. These graphs incorporate data on target-disease associations, protein structures, binding pockets, and known ligands, creating a rich, computer-readable resource. As noted by researchers at Exscientia, such complexity is difficult for the human mind to utilize effectively at scale, but graph-based AI methods can expertly navigate these knowledge graphs to select the most promising future targets [12].

Diagram 2: AI-powered data integration workflow for target identification and validation.

The systematic exploration of the druggable genome through chemogenomics represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery. By moving beyond single-target approaches to embrace selective polypharmacology, and by leveraging enriched chemical libraries in complex phenotypic models, researchers can now tackle diseases with multi-factorial etiologies like never before. The continued integration of genomic data, structural biology, and AI-driven analytics promises to further illuminate the dark corners of the druggable genome, transforming our understanding of human biology and accelerating the development of more effective therapeutics.

Orphan receptors, defined as proteins with no identified endogenous ligands, represent both a substantial challenge and untapped potential in therapeutic development. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and nuclear receptors constitute two major families where numerous orphans remain. As of recent assessments, 57 human class A GPCRs alone are still classified as orphans, alongside numerous nuclear receptors awaiting comprehensive ligand discovery [16] [17]. The deorphanization of these receptors has historically led to breakthrough therapies, exemplified by the discovery of PARP inhibitors for BRCA-mutant cancers following the identification of BRCA mutations [15]. Similarly, the pairing of cognate ligands with previously orphaned receptors like the free fatty acid receptors (FFA1-FFA4) and hydroxycarboxylic acid receptors (HCA1-HCA3) has opened new therapeutic avenues for metabolic diseases [16].

The process of moving from an orphan receptor to a validated drug target requires sophisticated approaches that integrate multiple technologies. Phenotypic screening has re-emerged as a powerful strategy for investigating incompletely understood biological systems, allowing researchers to observe how cells or organisms respond to chemical perturbations without presupposing a specific molecular target [15] [14]. However, a significant limitation of traditional phenotypic screening has been the difficulty in identifying the mechanisms of action underlying observed phenotypes. This is where chemogenomics—the systematic screening of chemical libraries against biological targets or phenotypes—provides a critical bridge, enabling the parallel exploration of protein families and the deconvolution of complex biological responses [18] [3] [19].

Chemogenomic Approaches for Orphan Receptor Investigation

Design Principles for Targeted Chemical Libraries

The development of specialized chemogenomic libraries represents a foundational step in orphan receptor research. Unlike diverse compound collections for broad screening, chemogenomic libraries are rationally designed to maximize target coverage across specific protein families while maintaining chemical diversity and defined pharmacological activities. According to recent studies, the best chemogenomics libraries currently interrogate approximately 1,000-2,000 targets out of the 20,000+ protein-coding genes in the human genome, highlighting both the progress and limitations in current coverage [15].

Effective chemogenomic library design incorporates several key principles. First, libraries should encompass a large and diverse panel of drug targets involved in multiple biological processes and diseases [3]. Second, they should include compounds with annotated bioactivities from reliable databases such as ChEMBL, which contains over 1.6 million molecules with bioactivity data against more than 11,000 targets [3] [20]. Third, libraries must be optimized for complementary activity and selectivity profiles across the target family, enabling the deconvolution of complex phenotypic responses [19]. Finally, chemical diversity across multiple scaffolds ensures orthogonality and reduces the risk of shared off-target effects [19].

Table 1: Essential Components of a Chemogenomic Library for Orphan Receptor Research

| Component | Specifications | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Selection | 5,000-10,000 compounds with annotated bioactivities | Maximize target coverage while maintaining screening feasibility |

| Target Coverage | Focus on druggable genome with emphasis on understudied protein families | Ensure relevance to orphan receptor space |

| Chemical Diversity | Multiple Murcko frameworks with Tanimoto similarity <0.7 | Minimize redundant structure-activity relationships |

| Activity Annotation | Potency (IC50, Ki, EC50) ≤10 µM, preferably ≤1 µM | Ensure biological relevance of interactions |

| Selectivity Data | Up to five off-targets at working concentration | Enable mechanism deconvolution |

Assembly and Validation of Chemogenomic Sets

The assembly of a high-quality chemogenomic set requires rigorous validation at multiple levels. A recent effort to create a chemogenomic set for NR1 nuclear hormone receptors exemplifies this process. Researchers started with 30,862 compounds with annotated NR1 activity from public repositories, applying stringent filters for potency (≤10 µM, preferably ≤1 µM), selectivity (up to five off-targets), and commercial availability [19]. Through iterative profiling, this set was refined to 69 comprehensively annotated modulators covering all members of the NR1 family.

Validation must extend beyond primary target activity to include assessment of cell viability effects across multiple cell lines (e.g., HEK293T, U-2 OS, MRC-9 fibroblasts), liability profiling against common off-targets (kinases, bromodomains), and in-family selectivity screening [19]. Techniques such as differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) can identify promiscuous binders through protein melting temperature shifts (ΔTm > 1.8°C considered relevant) [19]. Additional quality control includes verification of compound identity and purity (≥95%) through NMR, LC-UV, LC-ELSD, and LC-MS analyses [19].

Experimental Workflows: From Screening to Validation

Phenotypic Screening with Chemogenomic Libraries

The integration of chemogenomic libraries with advanced phenotypic screening platforms has revolutionized orphan receptor research. Modern phenotypic screening employs high-content imaging, single-cell technologies, and functional genomics to capture subtle, disease-relevant phenotypes at scale [14]. The Cell Painting assay, for instance, uses six fluorescent dyes to mark major cellular components, generating rich morphological profiles that can connect chemical perturbations to biological pathways [3]. When combined with chemogenomic libraries, this approach enables the systematic mapping of chemical structure to phenotypic outcome and potentially to molecular targets.

A proven workflow for phenotypic screening begins with the selection of a disease-relevant cellular model. For glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), researchers have successfully used patient-derived spheroids that better recapitulate the tumor microenvironment compared to traditional 2D cultures [13]. Following compound treatment, multiple phenotypic endpoints are assessed, including cell viability, morphological changes, and functional responses [13]. Active compounds are then counter-screened against normal cells (e.g., primary astrocytes, CD34+ progenitor cells) to identify selective agents [13].

Table 2: Key Phenotypic Assays for Orphan Receptor Research

| Assay Type | Cellular Model | Endpoint Measurements | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-content Imaging | U2OS cells, patient-derived cells | 1,779 morphological features (intensity, size, texture, granularity) | Morphological profiling, mechanism of action studies [3] |

| 3D Spheroid | Patient-derived GBM spheroids | Cell viability, invasion, matrix remodeling | Tumor growth inhibition, selective toxicity [13] |

| Tube Formation | Brain endothelial cells | Tube length, branching points | Anti-angiogenic activity [13] |

| Reporter Gene | Engineered cell lines | Luciferase or GFP expression | Receptor activation, transcriptional activity [18] |

Target Deconvolution and Validation

Once phenotypic hits are identified, the challenging process of target deconvolution begins. Multiple complementary approaches have proven effective for orphan receptor research. Transcriptomic profiling through RNA sequencing can reveal gene expression changes induced by active compounds, providing clues to their mechanisms of action [13]. Thermal proteome profiling (TPP) measures protein thermal stability changes upon compound binding across the proteome, directly identifying engaged targets [13]. For cases where specific hypotheses exist, cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) with antibodies can confirm compound binding to individual targets [13].

In a successful application of these methods, the compound IPR-2025 was discovered through phenotypic screening against GBM spheroids. Transcriptomic analysis suggested its mechanism involved cell cycle regulation and DNA damage response, while thermal proteome profiling confirmed direct engagement with multiple protein targets, demonstrating the polypharmacology often required for effective cancer therapeutics [13].

In Silico Methods for Enhanced Efficiency

Computational approaches have become indispensable for prioritizing candidates and generating testable hypotheses in orphan receptor research. Target prediction methods like MolTarPred leverage chemical similarity to compounds with known targets to suggest potential interactions [20]. Molecular docking can identify compounds capable of simultaneously binding multiple proteins, enabling the design of selective polypharmacology agents [13]. Network pharmacology integrates drug-target-pathway-disease relationships to contextualize screening results within broader biological systems [3].

A comparative analysis of target prediction methods identified MolTarPred as particularly effective, utilizing 2D similarity searching with MACCS fingerprints against the ChEMBL database [20]. For structure-based approaches, the availability of high-quality protein structures—increasingly enabled by AlphaFold—has expanded target coverage for virtual screening [21]. In one implementation, researchers docked approximately 9,000 compounds against 316 druggable binding sites on proteins in a glioblastoma subnetwork, successfully identifying compounds with desired polypharmacology profiles [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Orphan Receptor Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Chemical Tools | NR1 CG set (69 compounds), NR4A modulator set (8 compounds) [19] [18] | High-quality chemical probes for target family screening |

| Cell Line Models | HEK293T, U-2 OS, MRC-9 fibroblasts, patient-derived spheroids [19] [13] | Phenotypic screening in disease-relevant contexts |

| Assay Systems | Gal4-hybrid reporter gene assays, Cell Painting, thermal shift assays [18] [3] [13] | Target engagement and phenotypic profiling |

| Database Resources | ChEMBL, IUPHAR-DB, Guide to Pharmacology [20] [17] | Bioactivity data and target annotation |

Protocol: Implementation of a Phenotypic Screening Campaign

Stage 1: Library Preparation and Quality Control (2-3 weeks)

- Compound Selection: Identify 5,000-10,000 compounds representing diversity in structure and target coverage, prioritizing those with annotated activities in ChEMBL or similar databases [3].

- Liquid Handling: Prepare 10 mM DMSO stock solutions using acoustic dispensing to minimize volume errors.

- Quality Control: Assess compound identity via LC-MS and purity by HPLC (≥95% pure) [19].

- Plate Formatting: Transfer compounds to 384-well assay plates, including controls (positive/negative, DMSO vehicle).

Stage 2: Phenotypic Screening and Hit Confirmation (3-4 weeks)

- Cell Seeding: Plate disease-relevant cells (e.g., patient-derived GBM spheroids) in 384-well plates optimized for imaging [13].

- Compound Treatment: Add compounds at 1-10 µM final concentration using pintool transfer, maintaining DMSO concentration ≤0.1%.

- Incubation: Culture cells for 48-72 hours under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2).

- Staining and Imaging: For Cell Painting, stain with six fluorescent dyes (Mitotracker, ConA, Hoechst, etc.), image with high-content microscope [3].

- Image Analysis: Extract morphological features using CellProfiler, normalize data, and identify hits showing significant phenotypic changes [3].

- Hit Confirmation: Re-test hits in dose-response (8-point, 1 nM-30 µM) to determine IC50/EC50 values.

Stage 3: Target Deconvolution (4-6 weeks)

- Transcriptomic Profiling: Treat cells with compound vs. vehicle, isolate RNA after 24h, perform RNA-seq, conduct differential expression and pathway analysis [13].

- Thermal Proteome Profiling: Treat cell lysates or intact cells with compound vs. vehicle, heat at 10 temperatures, quantify soluble proteins via mass spectrometry, identify targets showing thermal stability shifts [13].

- Functional Validation: Apply genetic approaches (CRISPR, RNAi) against candidate targets to determine if they recapitulate compound phenotype [15].

The integration of chemogenomic libraries with phenotypic screening represents a powerful framework for elucidating the function of orphan receptors and transforming them into validated therapeutic targets. This approach has already demonstrated success across multiple target classes, from nuclear receptors to kinases and GPCRs. As chemical library diversity expands, screening technologies become more sophisticated, and computational methods more predictive, the systematic deorphanization of the proteome becomes an increasingly achievable goal. The protocols and resources outlined herein provide a roadmap for researchers to contribute to this exciting frontier in drug discovery.

Building and Applying Chemogenomic Libraries in Phenotypic Screens

Design Principles for Targeted and Diverse Chemogenomics Libraries

Chemogenomic (CG) libraries are indispensable tools in modern drug discovery, serving as powerful resources for phenotypic screening and target deconvolution. These carefully curated collections of compounds enable researchers to probe biological systems by modulating specific protein families or pathways, thereby linking chemical structure to biological function. Unlike highly selective chemical probes, chemogenomic compounds may interact with multiple targets but are characterized by well-understood activity profiles, making them particularly valuable for understanding complex biological systems and identifying novel therapeutic targets. The design and construction of these libraries represent a critical strategic endeavor that balances diversity, target coverage, and pharmacological properties to maximize their utility in drug discovery campaigns. Framed within the broader context of phenotypic screening applications, this article outlines the core design principles, practical implementation strategies, and experimental protocols for developing targeted and diverse chemogenomic libraries that drive innovative chemogenomics research.

Core Design Principles for Chemogenomic Libraries

Diversity and Representativeness

A foundational principle in chemogenomic library design is ensuring comprehensive structural and functional diversity. The BioAscent Diversity Set exemplifies this approach, having been selected by medicinal chemists to provide good starting points for discovery programs. This library contains approximately 57,000 different Murcko Scaffolds and 26,500 Murcko Frameworks, demonstrating extensive chemical diversity [22]. For more focused screening, smaller subsets (3,000-12,000 compounds) can be designed as structurally representative subsets of larger libraries, balancing structural fingerprint and physicochemical descriptor diversity while maintaining pharmacological relevance [22].

Focused Target Family Coverage

Chemogenomic libraries can be strategically designed to target specific protein families. The EUbOPEN consortium's ambitious initiative aims to create a chemogenomic library covering one-third of the druggable proteome, with particular emphasis on challenging target classes such as kinases, E3 ubiquitin ligases, and solute carriers (SLCs) [23]. This targeted approach enables systematic exploration of understudied target families while leveraging well-annotated compounds with overlapping target profiles for effective target deconvolution based on selectivity patterns [23].

Quality Control and Compound Integrity

Maintaining compound integrity and quality is paramount for generating reliable screening data. Proper storage conditions are essential, with examples including DMSO solutions (2mM & 10mM) in individual-use REMP tubes to ensure stability and prevent freeze-thaw degradation [22]. Additionally, the inclusion of PAINS (Pan-Assay Interference Compounds) sets and other problematic compounds during assay development helps identify potential liabilities and minimize false-positive results through appropriate counter-screening approaches [22].

Bioactivity and Selectivity Profiling

Comprehensive characterization of compound activity and selectivity is crucial for effective library design. The EUbOPEN consortium establishes strict criteria for compound qualification, including potency measurements (<100 nM in vitro), significant selectivity (at least 30-fold over related proteins), demonstrated cellular target engagement (<1 μM), and acceptable cellular toxicity windows [23]. These compounds are further annotated through suite of biochemical and cell-based assays, including those utilizing primary patient-derived cells representing diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, and neurodegeneration [23].

Table 1: Key Design Criteria for High-Quality Chemogenomic Libraries

| Design Parameter | Specification | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Diversity | High scaffold and framework diversity | 57,000 Murcko Scaffolds; 26,500 Murcko Frameworks [22] |

| Target Coverage | Broad proteome coverage with focus on specific families | Coverage of 1/3 of druggable genome; emphasis on E3 ligases, SLCs [23] |

| Potency Criteria | In vitro activity <100 nM | EUbOPEN compound qualification standards [23] |

| Selectivity Threshold | ≥30-fold selectivity over related proteins | Family-specific criteria for different target classes [23] |

| Cellular Activity | Target engagement <1 μM (or <10 μM for PPIs) | Demonstration of cellular target engagement [23] |

| Storage Conditions | DMSO solutions in individual-use REMP tubes | 2mM & 10mM concentrations; solid stock availability [22] |

Implementation and Workflow Strategies

Library Assembly and Validation

The assembly of chemogenomic libraries leverages hundreds of thousands of bioactive compounds generated by medicinal chemistry efforts in both industrial and academic sectors. When the EUbOPEN project launched in 2020, public repositories contained 566,735 compounds with target-associated bioactivity ≤10 μM, covering 2,899 human target proteins as potential chemogenomic compound candidates [23]. Kinase inhibitors and GPCR ligands historically dominate these collections, though other target families are becoming increasingly represented [23].

Validation of library quality often involves screening representative subsets against diverse biological targets to demonstrate utility. For example, a 5,000-compound subset of the BioAscent library was screened against 35 diverse targets including enzymes, nuclear hormone receptors, GPCRs, protein-protein interactions, and phenotypic cell growth/death assays, resulting in high-quality hits across these screens [22].

Application in Phenotypic Screening

In phenotypic screening contexts, chemogenomic libraries enable powerful target deconvolution strategies. When a phenotype is observed, the overlapping target profiles of multiple active compounds can be analyzed to identify the specific target responsible for the biological effect [23]. This approach was successfully applied in phenotypic profiling of glioblastoma patient cells, where chemogenomic library screening provided insights into potential therapeutic targets [24].

Diagram 1: Chemogenomic Library Screening Workflow. This workflow illustrates the sequential process from library assembly through target deconvolution, highlighting how selectivity patterns across multiple compounds enable target identification.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Design and Assembly of a Focused Chemogenomic subset

Objective: Create a targeted chemogenomic library subset for a specific protein family (e.g., kinases).

Materials:

- Compound collections with bioactivity data

- Computational infrastructure for virtual screening

- Chemical databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem)

- Medicinal chemistry expertise for compound selection

Procedure:

- Target Family Definition: Define the target family of interest and identify all relevant proteins within that family.

- Compound Sourcing: Identify available compounds with demonstrated activity against the target family from public repositories and commercial sources.

- Selectivity Analysis: Evaluate compound selectivity profiles using available bioactivity data, prioritizing compounds with well-characterized off-target activities.

- Structural Diversity Assessment: Ensure coverage of multiple chemotypes per target where possible, analyzing Murcko scaffolds and frameworks to avoid structural redundancy.

- Property Filtering: Apply drug-like property filters, considering parameters such as molecular weight, lipophilicity, and polar surface area.

- Validation Subset Creation: Select a representative subset (e.g., 5,000 compounds) enriched in bioactive chemotypes using Bayesian models or similar approaches [22].

Protocol 2: Phenotypic Screening and Target Deconvolution Using Chemogenomic Libraries

Objective: Identify molecular targets responsible for observed phenotypic effects in disease-relevant cellular models.

Materials:

- Curated chemogenomic library

- Disease-relevant cell models (e.g., patient-derived glioblastoma cells [24])

- Phenotypic readout equipment (e.g., high-content imager)

- Target annotation databases

Procedure:

- Library Preparation: Plate the chemogenomic library in appropriate format (e.g., 384-well plates) using liquid handling systems.

- Cell Seeding and Compound Treatment: Seed disease-relevant cells and treat with library compounds at appropriate concentrations (typically 1-10 μM).

- Phenotypic Assessment: Measure relevant phenotypic endpoints after appropriate incubation period (e.g., 72-144 hours).

- Hit Identification: Identify active compounds based on predefined significance thresholds for phenotypic modulation.

- Target Analysis: Compile target annotations for all active compounds and identify frequently occurring targets across the active compound set.

- Pathway Mapping: Map enriched targets to biological pathways to identify potential mechanisms underlying the observed phenotype.

- Validation: Confirm identified targets using orthogonal approaches (e.g., genetic knockdown, selective chemical probes).

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomic Screening

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | BioAscent Diversity Set (86,000 compounds); EUbOPEN CG Library [22] [23] | Source of chemical perturbations for phenotypic screening |

| Selective Probes | EUbOPEN chemical probes (100 probes with negative controls) [23] | Target validation and follow-up studies |

| Cell Models | Glioblastoma patient-derived cells [24]; Primary disease-relevant cells [23] | Biologically relevant screening systems |

| Annotation Databases | Public compound/bioactivity databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) [23] | Target annotation and selectivity assessment |

| PAINS Compounds | BioAscent PAINS Set [22] | Assay validation and counter-screening |

Data Management and Exploration

Effective data management is crucial for leveraging the full potential of chemogenomic libraries. The EUbOPEN consortium and related initiatives emphasize comprehensive data deposition in public repositories, with additional resources for data exploration [24]. For example, some projects provide web-based platforms for data visualization and exploration (e.g., www.c3lexplorer.com) [24], enabling researchers to contextualize their findings within broader screening datasets.

Standardized metadata collection and adherence to FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) ensure that screening data can be effectively integrated across studies and related to compound annotations [23]. This approach facilitates meta-analyses and comparisons across different experimental systems, increasing the utility and impact of chemogenomic screening data.

Diagram 2: Chemogenomic Library Design Strategy. This diagram illustrates the multi-faceted approach to library design, incorporating structural diversity, target family focus, comprehensive annotation, and quality control measures to enable effective phenotypic screening applications.

The design of targeted and diverse chemogenomic libraries represents a strategic integration of multiple principles: comprehensive structural diversity, focused target family coverage, rigorous quality control, and detailed bioactivity profiling. These libraries serve as powerful tools for phenotypic screening and target identification, particularly when applied to disease-relevant models such as patient-derived cells. The ongoing efforts of consortia like EUbOPEN, which aim to cover significant portions of the druggable proteome with well-annotated chemogenomic compounds, are dramatically expanding the toolbox available for probing biological systems and validating novel therapeutic targets. As these resources continue to grow and evolve, adhering to the design principles outlined in this article will ensure that chemogenomic libraries remain fit-for-purpose in the increasingly complex landscape of drug discovery, ultimately contributing to the development of new therapeutics for human disease.

The drug discovery landscape is undergoing a paradigm shift from a traditional single-target approach to a systems-level, multi-target strategy [25]. Classical pharmacology, with its linear receptor-ligand model, often experiences high failure rates in clinical trials (approximately 60-70%) and a greater risk of side effects, particularly for complex, multifactorial diseases like cancer, metabolic syndromes, and neurodegenerative disorders [25]. Systems pharmacology addresses these limitations by viewing diseases as perturbations within complex biological networks rather than as consequences of isolated molecular defects [26] [25]. This approach leverages network pharmacology to understand the sophisticated interactions among drugs, targets, and disease modules, thereby enabling the identification of multi-target therapeutics, drug repurposing, and personalized treatment regimens [27] [25]. Building integrated drug-target-pathway-disease networks is thus critical for understanding complex biological systems, predicting therapeutic efficacy, and minimizing adverse drug reactions in the context of phenotypic screening and chemogenomics applications [26].

Table 1: Comparison of Drug Discovery Paradigms

| Feature | Traditional Pharmacology | Network Pharmacology |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting Approach | Single-target | Multi-target / network-level |

| Disease Suitability | Monogenic or infectious diseases | Complex, multifactorial disorders |

| Model of Action | Linear (receptor–ligand) | Systems/network-based |

| Risk of Side Effects | Higher (off-target effects) | Lower (network-aware prediction) |

| Failure in Clinical Trials | Higher (60–70%) | Lower due to pre-network analysis |

| Technological Tools | Molecular biology, pharmacokinetics | Omics data, bioinformatics, graph theory |

| Personalized Therapy | Limited | High potential (precision medicine) |

Key Concepts and Network Theory

Central to systems pharmacology is the "network target" theory, which posits that the disease-associated biological network itself is the therapeutic target, rather than any single molecule [26]. Diseases emerge from disturbances in these complex networks, and effective interventions aim to restore the entire network's equilibrium [26] [25]. This holistic perspective is fundamental to interpreting phenotypic screening outcomes, as a phenotypic hit implies a successful perturbation of a disease-relevant network.

To standardize the representation of these complex biological processes, the community has developed the Systems Biology Graphical Notation (SBGN) [28]. SBGN provides a unified visual language for depicting pathways, ensuring that network diagrams are unambiguous and computationally interpretable. Furthermore, the Biological Pathway Exchange (BioPAX) format serves as a standard language for representing and exchanging pathway data at the molecular and cellular level, facilitating the integration of fragmented knowledge from over 300 pathway-related databases [29] [30]. The use of these standards is crucial for building consistent, reusable, and integrable network models.

Application Note: A Protocol for Network Construction and Analysis

This protocol details a workflow for constructing and analyzing a drug-target-pathway-disease network to identify potential multi-target drug candidates or repurpose existing drugs, a common goal in chemogenomics research.

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key stages of the network construction and analysis protocol.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Data Retrieval and Curation

Objective: To gather and standardize high-quality data from multiple public databases for network construction.

Materials:

- Computing Resources: Workstation with high-speed internet.

- Software: Scripting environment (e.g., Python/R) for data wrangling.

Procedure:

- Retrieve Drug and Target Information: Query drug-related data (chemical structures, targets, pharmacokinetics) from DrugBank, PubChem, and ChEMBL [25]. Represent drug structures using SMILES notation from PubChem [26].

- Acquire Disease Associations: Source disease-associated genes and molecular targets from DisGeNET, OMIM, and GeneCards [25].

- Obtain Omics Data: Download relevant omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) from repositories like GEO and TCGA to build disease-specific networks [26] [25].

- Compile Protein-Protein Interactions (PPI): Source PPI data from STRING, BioGRID, and IntAct, focusing on high-confidence interactions [26] [25].

- Data Curation:

- Standardize all identifiers (e.g., UniProt IDs for proteins, MeSH terms for diseases).

- Perform de-duplication of entries.

- Filter interactions based on confidence scores and relevance to the disease context [25].

Protocol 2: Network Construction and Integration

Objective: To integrate curated data into a unified, computable network model.

Materials:

- Software: Cytoscape (preferred for visualization and analysis) or NetworkX (Python library) [25].

Procedure:

- Construct Core Networks:

- Generate a drug-target bipartite network where edges connect drugs to their known protein targets.

- Build a target-disease network linking molecular targets to associated diseases.

- Create a PPI network to provide the functional context for the targets [25].

- Integrate Networks: Merge the drug-target, target-disease, and PPI networks into a single, interconnected drug-target-pathway-disease network.

- Map Pathway Information: Annotate the integrated network with pathway data from KEGG and Reactome to identify enriched biological pathways [25].

- Standardize Output: Export the network in a standard format like BioPAX for exchange or SBGN-ML for visualization [28] [30].

Protocol 3: Topological and Module Analysis

Objective: To identify key players and functional modules within the constructed network.

Materials:

- Software: Cytoscape with plugins (CytoHubba, MCODE, ClueGO) [25].

Procedure:

- Calculate Topological Metrics: Use graph-theoretical measures to analyze the network:

- Degree Centrality: Identifies highly connected nodes (hubs).

- Betweenness Centrality: Identifies bottleneck proteins that connect network modules.

- Closeness Centrality: Measures how quickly a node can access others in the network [25].

- Detect Functional Modules: Apply community detection algorithms like Louvain or MCODE to identify densely connected clusters of nodes that may represent functional units or synergistic drug targets [25].

- Perform Enrichment Analysis: Subject the key hub nodes and identified modules to functional enrichment analysis using DAVID or g:Profiler to determine overrepresented Gene Ontology terms and biological pathways [25].

Protocol 4: Predictive Modeling and In Vitro Validation

Objective: To predict novel drug-disease interactions and validate findings experimentally.

Materials:

- Computing Resources: GPU-accelerated computing environment for deep learning.

- Laboratory Equipment: Cell culture facility, equipment for cytotoxicity assays (e.g., MTS, CellTiter-Glo).

Procedure:

- Model Training: Train machine learning models, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) or Random Forests, on datasets like DeepPurpose or DeepDTnet to predict new drug-target or drug-disease interactions [26] [25].

- Model Validation: Evaluate model performance using cross-validation and metrics like the Area Under the Curve (AUC). A recent model achieved an AUC of 0.9298 and an F1 score of 0.6316 for predicting drug-disease interactions [26].

- In Vitro Validation:

- Select top-predicted drug combinations for a specific disease context (e.g., a cancer type).

- Perform in vitro cytotoxicity assays on relevant human cell lines to experimentally confirm synergistic effects [26].

- Use techniques like qPCR or Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) to validate target engagement and mechanism of action where applicable [25].

Results and Data Presentation

The application of the above protocols generates quantitative data that can be summarized for clear interpretation and decision-making.

Table 2: Key Databases and Tools for Network Pharmacology [25]

| Category | Tool/Database | Functionality |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Information | DrugBank, PubChem, ChEMBL | Drug structures, targets, pharmacokinetics |

| Gene-Disease Associations | DisGeNET, OMIM, GeneCards | Disease-linked genes, mutations |

| Target Prediction | Swiss Target Prediction, SEA | Predicts protein targets from compound structures |

| Protein-Protein Interactions | STRING, BioGRID, IntAct | High-confidence PPI data |

| Pathway Enrichment | KEGG, Reactome, DAVID | Identifies biological pathways and gene ontology |

| Network Visualization & Analysis | Cytoscape | Visual network construction, module analysis, plugin support |

Table 3: Example Performance Metrics of a Novel Network-Based Prediction Model [26]

| Metric | Performance on Drug-Disease Interactions | Performance on Drug Combinations (after fine-tuning) |

|---|---|---|

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | 0.9298 | - |

| F1 Score | 0.6316 | 0.7746 |

| Scope of Prediction | 88,161 interactions between 7,940 drugs and 2,986 diseases | - |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, software, and data resources essential for conducting research in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Type | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cytoscape | Software | Open-source platform for complex network visualization and analysis. Essential for integrating, visualizing, and topologically analyzing multi-layer networks. Use with CytoHubba and MCODE plugins. |

| STRTING Database | Data Resource | A database of known and predicted protein-protein interactions. Used as the foundational source for constructing the background PPI network. |

| DrugBank | Data Resource | A comprehensive database containing detailed drug and drug-target information. Critical for building the drug-target layer of the network. |

| BioPAX Format | Data Standard | A standard exchange format for pathway data. Allows for the integration of pathway information from multiple databases into a unified model for analysis [30]. |

| SBGN-ML | Visualization Standard | An XML-based file format for storing SBGN maps. Enables the exchange of pathway visualizations between different software tools [28]. |

| Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) | Data Resource | A public database that curates chemical-gene/protein interactions and chemical-disease relationships. Serves as a key source for known drug-disease interactions [26]. |

| Human Signaling Network | Data Resource | A signed PPI network meticulously annotated with activation and inhibition interactions. Used for simulating the propagation of drug effects through signaling pathways [26]. |

Network Visualization and Interpretation

The final integrated network provides a systems-level view of how a drug or combination perturbs a disease system. The following conceptual diagram represents a simplified drug-target-pathway-disease network, illustrating key relationships and the multi-target nature of interventions.

Interpretation Guide:

- Hub Nodes (e.g., Target 1): Highly connected proteins; their modulation can have widespread effects on the network.

- Bottleneck Nodes (e.g., Target 3): Proteins with high betweenness centrality; critical for communication between network modules.

- Multi-Target Drugs (e.g., Drug A): Single drugs that interact with multiple targets, potentially leading to synergistic effects or polypharmacology.

- Pathway Convergence: Multiple targets or drugs influencing the same pathway (or different pathways leading to the same disease phenotype) can reveal robust points for therapeutic intervention and explain phenotypic screening outcomes.