Overexpression vs Knockdown Screens: A Comprehensive Guide for Functional Genomics and Drug Discovery

This article provides a systematic comparison of overexpression (gain-of-function) and knockdown (loss-of-function) genetic screens, two pivotal methodologies in functional genomics.

Overexpression vs Knockdown Screens: A Comprehensive Guide for Functional Genomics and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of overexpression (gain-of-function) and knockdown (loss-of-function) genetic screens, two pivotal methodologies in functional genomics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles, distinct applications, and complementary strengths of each approach. The content delves into modern implementation using CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and interference (CRISPRi) technologies, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and presents a framework for rigorous validation and comparative analysis. By synthesizing insights from current literature and real-world case studies in oncology and neuroscience, this guide aims to inform strategic decisions in experimental design to deconvolute disease mechanisms and identify novel therapeutic targets.

Core Concepts: Unraveling the Principles of Gain-of-Function and Loss-of-Function Screens

Core Concepts and Mechanisms at a Glance

In functional genomics and drug development, overexpression and knockdown represent two foundational, complementary paradigms for probing gene function. Overexpression is primarily used to study gain-of-function (GOF) effects, while knockdown is used to study loss-of-function (LOF) effects [1]. The table below summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Overexpression and Knockdown Paradigms

| Feature | Overexpression (GOF) | Knockdown (LOF) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Introduce a functional gene to assess the effects of its enhanced activity [2]. | Reduce expression of an endogenous gene to study the consequences of its depletion [3]. |

| Molecular Mechanism | Increased protein levels leading to heightened or novel biological activity [4] [1]. | Reduced mRNA or protein levels, diminishing the gene's native function [3] [5]. |

| Typical Applications | • Identifying therapeutic genes for cell reprogramming [6]• Studying oncogene function [4]• Differentiation therapy [2] | • Validating essential genes for survival [3]• Modeling haploinsufficiency diseases [1]• Synthetic lethality screens [6] |

| Key Outcome | Emergence of new phenotypes or enhanced cellular processes [2] [4]. | Disruption of normal cellular functions, revealing gene necessity [3] [5]. |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Empirical data from recent studies highlight the distinct transcriptional outcomes and phenotypic consequences of these two approaches.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison from Experimental Studies

| Study Context | Perturbation Method | Key Quantitative Findings | Phenotypic Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Retina Regeneration [7] | Cyclin D1 Overexpression & p27Kip1 Knockdown | • p27Kip1 knockdown alone: minimal MG proliferation• Cyclin D1 overexpression alone: 3-fold increase in MG proliferation vs. p27Kip1 knockdown• Combined approach: 5-fold increase in MG proliferation vs. cyclin D1 alone | Robust, self-limiting Müller glia (MG) proliferation, enabling potential neuron regeneration. |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) [2] | KDM6A Overexpression | Significant alteration in proliferation rate, cell cycle pattern, colony formation, and migration capacity of Huh-7 cells. | Attenuation of cancerous features, promotion of hepatocytic differentiation. |

| Cell Adhesion Study [3] | CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout & RNAi Knockdown | • Antibody transfection & CRISPR-Cas9: induced fewer deregulated mRNAs than RNAi• siRNAs: only 10% overlap of deregulated transcripts with negative controls | Distinct temporal onset dynamics for each method; antibodies induced phenotypic changes without altering target expression. |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) [5] | TDP-43 Loss-of-Function | Identification of 227 cryptic alternative polyadenylation (APA) events upon TDP-43 knockdown. | Nuclear depletion-induced cryptic APA, contributing to neurodegenerative disease pathology. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of overexpression and knockdown experiments relies on a suite of specialized molecular tools.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Genetic Perturbation Experiments

| Reagent / Method | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) [7] | In vivo gene delivery for overexpression or knockdown. | High transduction efficiency, cell-type-specific promoters (e.g., GFAP), broad tropism with different serotypes. |

| Lentiviral Vectors [2] | Stable integration of transgenes (e.g., KDM6A) or shRNAs into the host genome. | Enables long-term, stable gene expression or repression; suitable for difficult-to-transfect cells. |

| CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) [8] [9] | Targeted gene knockdown using a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressor domains. | High specificity, reversible repression, minimal off-target effects compared to RNAi; uses dCas9-SALL1-SDS3 or dCas9-KRAB. |

| Synthetic sgRNA [9] | Chemically synthesized guide RNA for CRISPRi/CRISPRa applications. | Rapid delivery (transfection/electroporation), gene repression evident within 24 hours, enables easy multiplexing. |

| RNA Interference (RNAi) [3] | Sequence-specific degradation of mRNA using small interfering RNA (siRNA). | Rapid knockdown, but can have moderate off-target effects due to nonspecific mRNA binding. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AAV-Mediated Overexpression and KnockdownIn Vivo

This protocol, based on retinal regeneration research [7], demonstrates a dual-vector strategy for manipulating gene expression in vivo.

- Vector Design: Clone the gene of interest (e.g., cyclin D1) or short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against the target (e.g., p27Kip1) into an AAV vector. Use a cell-type-specific promoter (e.g., GFAP for Müller glia) to restrict expression.

- Virus Production and Purification: Package the recombinant genome into AAV capsids (e.g., serotype 7m8 for retinal studies) using a standard transfection method in HEK293T cells. Purify the virus via ultracentrifugation.

- In Vivo Injection: Anesthetize the animal (e.g., postnatal day 6 mice) and perform intravitreal injection of the AAV vector into the eye.

- Phenotype Tracking: Administer a pulse of a nucleotide analog like EdU to label proliferating cells. After a predetermined period, harvest the tissue for analysis.

- Validation and Analysis:

- Immunohistochemistry: Analyze tissue sections for EdU incorporation and cell-type-specific markers (e.g., Sox9 for Müller glia) to quantify proliferation.

- qPCR: Quantify the level of target gene knockdown and/or transgene overexpression from harvested tissue.

Protocol 2: Lentiviral Overexpression in Cell Lines

This protocol, used to study tumor suppressors in hepatocellular carcinoma [2], outlines the process for stable gene overexpression in cultured cells.

- Lentiviral Vector Construction: Amplify the coding sequence (CDS) of the target gene (e.g., KDM6A) and clone it into a lentiviral expression plasmid (e.g., pLenti) using Gibson assembly. Verify the sequence.

- Lentivirus Production: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with the transfer plasmid (pLenti-KDM6A) and packaging plasmids (psPAX2 and pMD2.G) using a lipofectamine reagent.

- Virus Harvest and Titration: Collect the viral supernatant 48 hours post-transfection, filter it through a 0.45 μm membrane, and concentrate if necessary. Determine the viral titer using a suitable cell line (e.g., HT-1080).

- Cell Transduction: Seed the target cells (e.g., Huh-7) and transduce them with the viral supernatant in the presence of polybrene to enhance infection efficiency.

- Selection and Expansion: Select transduced cells using an antibiotic (e.g., puromycin) for 4-10 days. Expand the resistant population for downstream experiments.

- Phenotypic Assessment:

- Functional Assays: Perform proliferation assays (MTT), migration assays (scratch/wound healing), and colony formation assays.

- Molecular Analysis: Use qRT-PCR and Western blot to confirm gene expression and analyze downstream markers (e.g., EMT markers, differentiation genes).

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

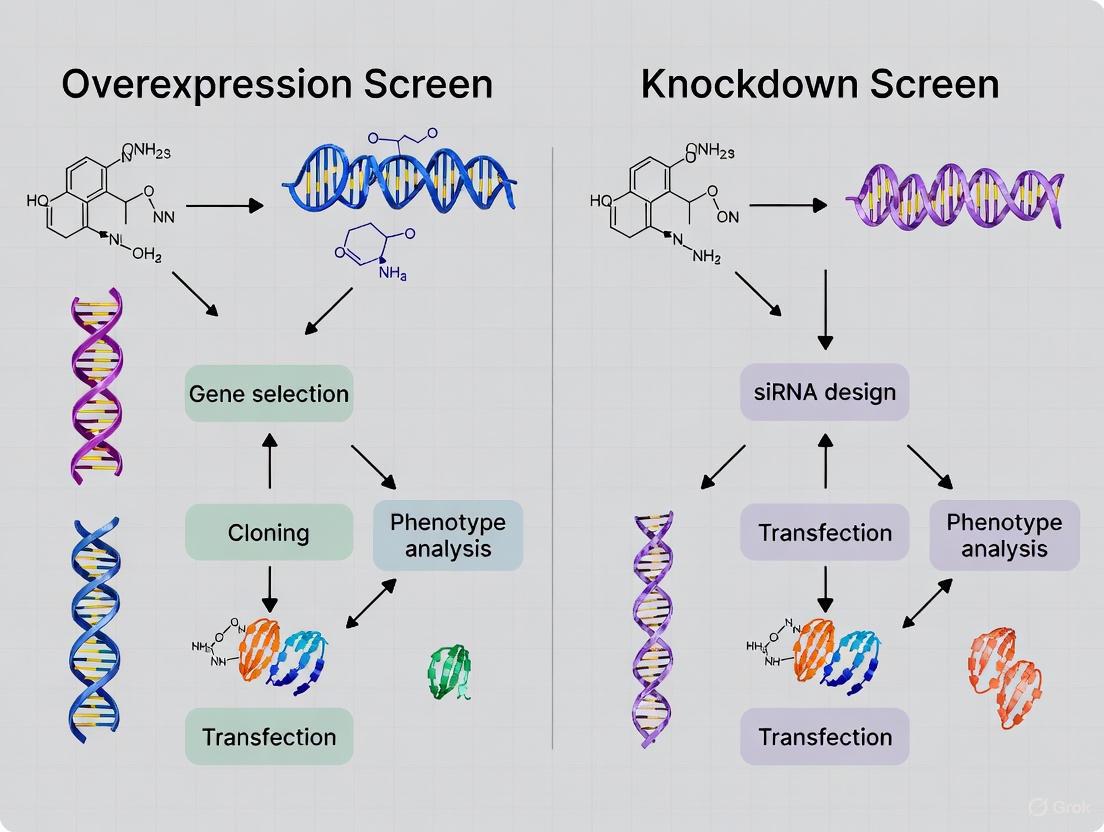

Diagram 1: Core Mechanistic Pathways of GOF and LOF

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Combined GOF/LOF Study

The journey from cDNA libraries to modern CRISPR tools represents one of the most significant technological evolution in molecular biology. This transition has fundamentally transformed how researchers investigate gene function, moving from broad observational approaches to precise, systematic genetic manipulation. Within the context of comparing overexpression versus knockdown screening methodologies, this evolution highlights complementary approaches for understanding gene function—either by reducing gene expression to infer function or by enhancing expression to observe gain-of-function effects. This guide objectively compares these approaches through their historical development and current applications.

From cDNA to CRISPR: A Technical Revolution

The development of genetic screening tools has progressed through several distinct phases, each building upon the limitations of previous technologies. cDNA libraries, collections of complementary DNA sequences synthesized from messenger RNA, were among the first tools for gene discovery and expression studies. While revolutionary for their time, they lacked the precision for systematic functional genetics.

The emergence of RNA interference (RNAi) technologies marked a significant advancement, enabling targeted gene knockdown through introduction of small interfering RNAs. However, RNAi suffered from off-target effects and incomplete knockdown, limiting its reliability for large-scale screens [10].

The CRISPR-Cas9 system, adapted from a bacterial immune mechanism, represents the current state-of-the-art. Its precision, efficiency, and programmability have made it the preferred tool for both small-scale investigations and genome-wide screens [11]. The technology continues to evolve with base editing, prime editing, and activation/inhibition systems expanding its capabilities [12].

Comparative Analysis of Screening Approaches

Modern genetic screening employs two primary complementary approaches: loss-of-function (knockdown/knockout) and gain-of-function (overexpression) studies. The table below summarizes their key characteristics:

| Feature | Knockdown/Knockout Screens | Overexpression Screens |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Utilizes CRISPR knockout (CRISPRn) or inhibition (CRISPRi) to disrupt or reduce gene function [12] [13] | Employs CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) or cDNA overexpression to enhance gene expression [13] |

| Primary Application | Identifying essential genes, drug targets, and genes whose loss confers resistance [13] | Discovering genes that drive phenotypes when overexpressed, including drug resistance mechanisms [13] |

| Typical Library Size | Varies from minimal (3-6 gRNAs/gene) to comprehensive (10+ gRNAs/gene) [14] | Similar range to knockout libraries, with 4-10 gRNAs per gene common [13] |

| Key Advantages | Reveals gene essentiality; identifies synthetic lethal interactions | Uncovers oncogenes and resistance mechanisms; complements knockout findings [13] |

| Limitations | May miss genes requiring overexpression to reveal function | Can produce non-physiological effects; may activate compensatory mechanisms |

Table 1: Comparison of knockdown/knockout versus overexpression screening approaches

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Data

Recent benchmarking studies provide quantitative comparisons of CRISPR library performance. The table below summarizes key metrics from empirical evaluations:

| Library Name | gRNAs per Gene | Essential Gene Depletion | Non-essential Enrichment | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vienna-single | 3 | Strongest depletion | Minimal enrichment | Minimal library size applications [14] |

| Yusa v3 | 6 | Moderate depletion | Moderate enrichment | Standard screening conditions [14] |

| Croatan | 10 | Strong depletion | Low enrichment | High-sensitivity essentiality screens [14] |

| Vienna-dual | 3 pairs | Strongest depletion | Some fitness reduction observed | Maximum sensitivity screens [14] |

| Brunello | 4 | Strong depletion | Low enrichment | General purpose knockout screens [13] |

Table 2: Performance benchmarking of commonly used CRISPR libraries

Notably, recent studies demonstrate that minimal libraries with only 3 highly efficient guides per gene can perform as well or better than larger libraries when guides are selected using principled criteria like VBC scores [14]. Dual-targeting libraries, where two sgRNAs target the same gene simultaneously, show enhanced depletion of essential genes but may induce a mild fitness cost even in non-essential genes, possibly due to increased DNA damage response [14].

Experimental Protocols: From Library Design to Analysis

CRISPR Knockout Screen Protocol

The following workflow details a typical genome-wide CRISPR knockout screen, based on established methodologies [13]:

- Library Selection: Choose an appropriate library (e.g., Brunello with 4 gRNAs per gene targeting 19,114 genes) [13]

- Lentiviral Production: Package the sgRNA library into lentiviral particles in HEK293T cells

- Cell Transduction: Transduce target cells at low MOI (~0.1) to ensure single integration events

- Selection: Apply puromycin selection (1 μg/mL) for 3-7 days to eliminate untransduced cells

- Screening: Split cells into treatment and control groups; for ATR inhibitor screens, use high doses (e.g., 1.5μM VE822) that kill ~90% of cells over 108 hours [13]

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest surviving cells and extract genomic DNA after 10-14 days

- sgRNA Amplification: PCR-amplify sgRNA regions using barcoded primers for multiplexing

- Sequencing: Perform Illumina sequencing to quantify sgRNA abundance

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Use MAGeCK or RSA algorithms to identify significantly enriched/depleted sgRNAs [13]

CRISPR Activation Screen Protocol

CRISPR activation screens follow a similar workflow with key modifications [13]:

- Library Selection: Employ a CRISPR activation library (e.g., Calabrese library)

- dCas9-VPR Expression: Use cells stably expressing the dCas9-VPR activation system

- sgRNA Delivery: Transduce with activation library as described above

- Selection and Screening: Follow similar selection and treatment steps as knockout screens

- Analysis: Identify genes whose overexpression confers resistance or other phenotypes

Library Customization Protocol

Customizing existing libraries using CRISPR/Cas9 itself provides a efficient alternative to building new libraries [15]:

- Identify Target gRNAs: Select gRNAs to eliminate from existing library

- Design rc-gRNAs: Create reverse-complementary gRNAs targeting undesired gRNAs in the library plasmid DNA

- Form RNPs: Complex purified Cas9 proteins with rc-gRNAs to form ribonucleoproteins

- Library Treatment: Incubate pooled CRISPR library plasmid DNA with RNPs (e.g., 20μg library DNA with 10μg Cas9 + 7.5μg rc-gRNAs for 8h at 37°C) [15]

- Purify Depleted Library: Recover processed library DNA through isopropanol precipitation

- Quality Control: Verify specific gRNA depletion via qPCR and deep sequencing

Visualizing Screening Approaches and Workflows

Knockdown vs. Overexpression: Conceptual Framework

Integrated Screening Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent/Library | Type | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brunello Library [13] | CRISPR knockout | Genome-wide loss-of-function screens | 76,441 gRNAs targeting 19,114 genes; 4 gRNAs/gene |

| Calabrese Library | CRISPR activation | Genome-wide gain-of-function screens | dCas9-VPR system; targeted gene overexpression |

| GeCKO v2 | CRISPR knockout | Customizable screening | Dual-sgRNA libraries; modular design |

| Vienna Library | CRISPR knockout/activation | Minimal library screens | Top 3 VBC-scored gRNAs per gene; high efficiency [14] |

| ATR Inhibitors (VE822, AZD6738) [13] | Small molecule compounds | DNA damage response studies | Selective ATR kinase inhibition; clinical relevance |

| MAGeCK | Bioinformatics tool | CRISPR screen analysis | Identifies positively/negatively selected genes |

| Chronos | Bioinformatics tool | Time-series screen analysis | Models gene fitness across multiple timepoints [14] |

Table 3: Essential research reagents for genetic screens

The evolution from cDNA libraries to modern CRISPR tools has provided researchers with an unprecedented ability to systematically probe gene function. The choice between knockdown and overexpression approaches depends heavily on the biological question:

- Knockdown/knockout screens excel at identifying essential genes and synthetic lethal interactions, particularly for investigating drug sensitivity [13].

- Overexpression/activation screens powerfully reveal oncogenes, resistance mechanisms, and genes that produce phenotypes only when upregulated [13].

- Dual screening approaches, combining both methods, provide the most comprehensive understanding of gene function in biological processes and therapeutic contexts [13].

Recent advances in library design, particularly minimal libraries with highly efficient guides, have made genome-wide screens more accessible and cost-effective [14]. Furthermore, AI tools like CRISPR-GPT are now accelerating experimental design and making CRISPR technologies accessible to non-specialists [16]. As these technologies continue to converge, they promise to further accelerate the pace of functional genomics and therapeutic discovery.

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Key Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi Effectors | dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-SALL1-SDS3, dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) [9] [17] [18] | Engineered fusion proteins that bind DNA without cutting and recruit repressive complexes to silence target genes. |

| CRISPRa Effectors | dCas9-VP64, dCas9-VPR, SAM system (dCas9-VP64-MS2-P65-HSF1) [18] [19] [20] | Fusion proteins or complexes that recruit transcriptional activators to the promoter region to upregulate gene expression. |

| Guide RNAs | Synthetic sgRNA, crRNA:tracrRNA duplex, Lentiviral sgRNA [9] [19] | Programmable RNA components that direct the dCas9 effector to specific genomic loci based on sequence complementarity. |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lentiviral particles, Transient mRNA, Plasmids, Baculovirus (for ASCs) [9] [19] [20] | Methods for introducing CRISPR components into cells; chosen based on desired duration (transient vs. stable) and cell type. |

| Controls | Non-targeting sgRNA, Targeting sgRNA for housekeeping genes (e.g., PPIB) [9] [21] | Essential reagents to account for non-specific effects of delivery and the CRISPR machinery itself. |

CRISPRa/i, RNAi, and cDNA Overexpression: A Comparative Guide

In the functional genomics toolkit, researchers have multiple methods to perturb gene expression and investigate gene function. The key strategic choice often lies between gain-of-function (GOF) and loss-of-function (LOF) approaches [22]. cDNA overexpression is a classic GOF technique, while CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and RNA interference (RNAi) are two central LOF methods [23] [22]. This guide objectively compares the performance, specificity, and applications of these key technological platforms—CRISPRi, RNAi, and cDNA overexpression—framed within the context of overexpression versus knockdown screens for target discovery and validation.

The core distinction between these technologies lies in their mechanism and level of action: CRISPRi acts at the genomic DNA level to prevent transcription, RNAi operates at the mRNA level to trigger transcript degradation, and cDNA overexpression introduces an exogenous transcript to augment gene function [18] [21] [22].

The following table provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of their key characteristics.

| Feature | CRISPRi | RNAi | cDNA Overexpression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | dCas9-repressor fusion binds DNA and blocks transcription [9] [18]. | siRNA/shRNA binds mRNA, leading to its degradation [21]. | Introduces exogenous cDNA copy of the gene to increase expression [22]. |

| Level of Intervention | Transcriptional (DNA level) [18]. | Post-transcriptional (mRNA level) [21]. | Transcriptional (via exogenous promoter) [22]. |

| Reversibility | Reversible (knockdown) [18] [22]. | Reversible (knockdown) [23]. | Reversible (dependent on delivery method). |

| Genetic Alteration | Epigenetic/modulation, no DNA cleavage [9] [18]. | None (targets mRNA) [21]. | Addition of genetic material. |

| Typical Knockdown Efficiency | Robust (down to 20-30% of baseline) [9]. | Variable, can be high [21]. | Not Applicable (Overexpression) |

| Duration of Effect | Extended (days to weeks) [9]. | Transient (typically 3-7 days) [9]. | Variable (transient to stable). |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (easy to pool multiple sgRNAs) [9] [22]. | Moderate (can be limited by competition) [9]. | Low (limited by vector capacity and promoter compatibility). |

| Major Source of Off-Target Effects | Off-target DNA binding [21]. | Seed sequence homology with non-target mRNAs [21]. | Ectopic, non-physiological expression levels. |

| Key Advantages | High specificity; reversible; gentle knockdown; excellent for non-coding genes [9] [18] [22]. | Rapid deployment; well-established [21]. | Studies dominant-positive effects; expresses mutated genes; complements knockdown studies [10]. |

Supporting Experimental Data and Performance

Independent, direct comparisons and functional assays highlight critical performance differences between these methods.

- Efficiency and Duration: In head-to-head tests, CRISPRi-mediated gene repression is evident 24 hours after transfection and persists through at least 96 hours, with maximal repression at 48-72 hours [9]. RNAi effects are typically transient, often lasting a few days, which can be a limitation for long-term studies [9].

- Specificity and Off-Target Effects: A systematic study comparing off-target effects at the whole-transcriptome level found that all three major LOF methods (RNAi, LNA gapmers, and CRISPRi) yielded non-negligible off-target effects [21]. However, the nature of these effects differs. RNAi off-targets are largely driven by seed sequence homology in the siRNA, leading to unintended mRNA degradation [21]. In contrast, CRISPRi introduced in a polyclonal population showed limited sequence-dependent off-target effects, though single-cell clones from this population could exhibit unique and reproducible transcriptional signatures [21].

- Multiplexing and Screening Performance: CRISPRi and CRISPRa are highly effective for pooled genetic screens. CRISPRi knockdown phenotypes robustly identify essential genes, while CRISPRa can reveal genes whose overexpression is detrimental, such as tumor suppressors [22]. A key advantage of CRISPRi synthetic sgRNA is the straightforward pooling of guides to enhance knockdown of a single gene or to enable the simultaneous knockdown of multiple genes without substantial loss of efficiency, a process known as multiplexing [9].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, below are detailed methodologies for implementing these technologies, as cited in the literature.

CRISPRi Knockdown with Synthetic sgRNA

This protocol is adapted from Horizon Discovery's CRISPRi application guide [9].

- Cell Line: U2OS cells stably expressing integrated dCas9-SALL1-SDS3 or dCas9-KRAB.

- Transfection:

- Plate cells at 10,000 cells/well in a multi-well plate.

- Transfect with a pool of pre-designed synthetic sgRNAs (total concentration 25 nM) using DharmaFECT 4 Transfection Reagent.

- Include a non-targeting control (NTC) sgRNA.

- Harvest and Analysis:

- Harvest cells at 72 hours post-transfection for maximal repression.

- Isolate total RNA and synthesize cDNA.

- Measure relative gene expression using RT-qPCR with the ∆∆Cq method, using GAPDH or ACTB as a housekeeping gene.

RNAi Knockdown with siRNA

This protocol is based on the methods used in the ADAM28 prostate cancer study [24].

- Cell Line: Human prostate cancer cells (e.g., LNCaP, DU145).

- Transfection:

- Seed cells into 12-well culture dishes.

- Transfert with 10 nM Silencer Select siRNA (e.g., targeting ADAM28) using X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent.

- Use a scrambled siRNA sequence as a negative control.

- Incubate for 48 hours in growth media free of penicillin/streptomycin.

- Functional Assays:

- Assess proliferation using assays like MTT or BrdU.

- Assess migration using Transwell or wound-healing assays.

- Confirm knockdown via western blotting or RT-qPCR.

cDNA Overexpression

This protocol is illustrative of the approach used in GOF studies, as seen in the ADAM28 study [24].

- Cell Line: Relevant cell model (e.g., RWPE1 normal prostate epithelial cells).

- Transfection:

- Transfect cells with plasmid vectors (e.g., pCMV Tag4A ADAM28) using a suitable transfection reagent.

- Use an empty vector (e.g., pCMV Tag4A) as a control.

- Validation and Functional Assays:

- Confirm overexpression 48 hours post-transfection using immunocytochemistry or western blotting.

- Perform functional assays (proliferation, migration) paralleling the knockdown experiments.

Visualization of Workflows and Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the core mechanisms and experimental workflows for these technologies.

Experimental Workflow for Functional Screening

In functional genomics, the systematic manipulation of gene expression levels—through either overexpression or knockdown—serves as a fundamental strategy for elucidating gene function. The core premise is that observing phenotypic consequences resulting from too much or too little of a gene product can reveal its normal biological role within a cell or organism [25]. Overexpression studies introduce an excess of a gene's product, often revealing its potential roles in driving cellular processes and potentially uncovering dominant-negative or neomorphic effects. Conversely, knockdown techniques reduce gene expression, mimicking loss-of-function mutations and highlighting genes essential for specific biological processes [26]. Together, these complementary approaches form a powerful toolkit for deconstructing complex biological systems, defining signaling pathways, and identifying potential therapeutic targets in disease contexts such as cancer [27] [13] [28].

Experimental Approaches for Modulating Gene Expression

Gene Knockdown Methodologies

Gene knockdown refers to experimental techniques that reduce the expression of one or more genes. This can be achieved through methods that do not permanently alter the chromosomal DNA, leading to a transient knockdown, or through genetic modification, resulting in a stable "knockdown organism" [25].

- RNA Interference (RNAi): This is a widely used knockdown method that utilizes double-stranded RNA to induce sequence-specific gene silencing. The process involves introducing small double-stranded interfering RNAs (siRNAs) into the cytoplasm. These siRNAs are loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which uses them as a template to locate and cleave complementary messenger RNA (mRNA) transcripts, preventing their translation into protein [25] [29]. For stable, long-term knockdown, short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) can be expressed from viral or plasmid vectors, which are then processed into siRNAs inside the cell [29].

- CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi): While the CRISPR-Cas system is famously used for gene knockout, it can also be engineered for knockdown. Using a catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressive domains, the system can be targeted to specific gene promoters to block transcription without cutting the DNA, effectively reducing gene expression [13] [25].

- Morpholino Oligonucleotides: These are antisense oligonucleotides used primarily in developmental biology models like zebrafish. They are designed to bind to specific mRNA sequences, blocking translation or pre-mRNA splicing. A key advantage is their stability, as they are not degraded by cellular enzymes, but their effect is diluted with each cell division [26].

Gene Overexpression Methodologies

Overexpression studies aim to increase the production of a specific gene product to observe the resulting phenotypic effects.

- Recombinant Expression Vectors: This common method involves cloning the cDNA of a target gene into a plasmid vector under the control of a strong promoter, such as the CAG promoter (a hybrid of CMV enhancer and chicken beta-actin promoter) [30]. The recombinant plasmid is then transfected into cells, leading to the production of the target gene's mRNA and protein at levels significantly higher than normal [31].

- cDNA Screening: In this approach, libraries containing hundreds of cDNAs are systematically transfected into cell lines. This allows for the high-throughput identification of genes that, when overexpressed, modulate specific pathways of interest, such as the Sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway [28].

- CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa): This gain-of-function version of CRISPR uses a dCas9 protein fused to transcriptional activators. When guided to a gene's promoter, the complex can significantly upregulate the gene's transcription, providing a powerful tool for genome-wide overexpression screens [13].

Advanced Screening Platforms

Modern genetic screens often employ dual approaches to comprehensively map gene function. A prime example is the use of dual genome-wide CRISPR knockout and CRISPR activation screens to identify genes that confer resistance or sensitivity to drugs like ATR inhibitors. This dual strategy allows researchers to simultaneously probe loss-of-function and gain-of-function phenotypes in a single, systematic experiment [13].

Furthermore, innovative tools like the "Double UP" plasmid address technical challenges in functional studies. This dual-fluorescent plasmid uses a LoxP-flanked cassette and limiting Cre recombinase to generate an internal control within the same population of transfected cells. This allows for a direct and robust comparison between control (e.g., mNeonGreen-positive) and experimentally manipulated (e.g., mScarlet-positive) cells, significantly reducing variability and improving the reliability of conclusions drawn from overexpression or knockdown experiments [30].

Comparative Analysis: Overexpression vs. Knockdown Screens

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, applications, and outputs of overexpression and knockdown screens, illustrating their complementary nature in functional genomics.

Table 1: Comparative overview of overexpression and knockdown screens.

| Feature | Overexpression Screens | Knockdown Screens |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Identify genes that drive processes or confer capabilities when overexpressed [13] [28]. | Identify genes essential for specific biological processes or cell viability when suppressed [13] [25]. |

| Typical Approach | cDNA libraries, CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) [13] [28]. | RNAi (siRNA/shRNA), CRISPR knockout [13] [25]. |

| Key Readouts | Enhanced proliferation, migration, drug resistance, pathway activation [27] [28] [31]. | Impaired proliferation, migration, increased apoptosis, pathway inhibition, sensitization to drugs [27] [13]. |

| Major Utility | Uncovering oncogenes, signaling pathway modulators, and mechanisms of drug resistance [13] [28]. | Identifying tumor suppressors, essential genes, and synthetic lethal interactions for therapy [27] [13]. |

Case Studies in Cancer Research

Targeting the P2X7 Receptor in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

A clear example of how both overexpression and knockdown validate a therapeutic target comes from research on the P2X7 receptor in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Researchers constructed recombinant plasmids to overexpress or knock down the P2X7 receptor in LLC and LA795 lung cancer cells.

- Overexpression Effects: Forcing the expression of the P2X7 receptor promoted the migration and invasion of lung cancer cells. It also activated pro-tumorigenic signaling pathways, including PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β and JNK, and induced changes associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [27].

- Knockdown Effects: Reducing P2X7 receptor expression produced the opposite effects: it suppressed cell proliferation, promoted apoptosis, and inhibited tumor growth in both cell-based and animal models. The expression levels of PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β, JNK, and EMT markers were consistently downregulated, confirming the pathway involvement [27].

This dual-approach study conclusively demonstrated that downregulating the P2X7 receptor effectively suppresses tumor growth and progression, establishing its potential as a therapeutic target for NSCLC [27].

Table 2: Quantitative effects of P2X7 receptor modulation in lung cancer models (based on [27]).

| Experimental Group | Proliferation Impact | Migration/Invasion Impact | Key Signaling Pathway Modulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2X7 Overexpression | Promoted growth | Increased migration and invasion | Activation of PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β and JNK; induction of EMT |

| P2X7 Knockdown | Suppressed growth; promoted apoptosis | Inhibited migration and invasion | Suppression of PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β and JNK; inhibition of EMT |

Identifying Modulators of ATR Inhibitor Resistance

The power of dual CRISPR screens is exemplified in research aimed at understanding resistance to ATR inhibitors (ATRi), emerging cancer therapeutics. A study performed both genome-wide CRISPR knockout and CRISPR activation screens in HeLa and MCF10A cells treated with two different ATR inhibitors, VE822 and AZD6738 [13].

- Knockdown Screen Findings: The knockout screen identified genes that, when lost, made cells more resistant to ATR inhibitors. The top hits were enriched for biological pathways like protein translation, DNA replication, and sister chromatid cohesion [13].

- Overexpression Screen Findings: The parallel activation screen identified genes that, when overexpressed, could also confer resistance to ATRi.

- Integrated Analysis: By combining both screens, the study revealed that resistance mechanisms are varied. They can involve restoring DNA replication fork progression or preventing ATR inhibitor-induced apoptosis. For instance, the study described how MED12-mediated inhibition of the TGFβ pathway can regulate replication fork stability and survival upon ATR inhibition [13].

This comprehensive approach successfully cataloged genetic determinants of ATRi resistance, providing a foundation for personalized cancer medicine by identifying potential biomarkers to predict patient response [13].

Dissecting Sonic Hedgehog Signaling in Down Syndrome

Research into the link between trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) and cerebellar defects showcases the use of a targeted overexpression screen. Given that chromosome 21 does not encode any known canonical Sonic hedgehog (SHH) pathway components, researchers systematically overexpressed 163 chromosome 21 cDNAs in SHH-responsive mouse cell lines to find which ones modulated the pathway [28].

- Functional Discovery: The screen successfully identified specific chromosome 21 genes that either upregulated (e.g., DYRK1A) or inhibited (e.g., HMGN1) SHH signaling [28].

- Validation in Disease Models: The relevance of these findings was confirmed by analyzing gene expression in the cerebella of Ts65Dn and TcMAC21 mouse models of Down syndrome. Furthermore, overexpressing four prioritized genes (B3GALT5, ETS2, HMGN1, and MIS18A) in primary granule cell precursors inhibited their SHH-dependent proliferation, linking these genes to the cerebellar hypoplasia phenotype [28].

This study highlights how a focused overexpression screen can pinpoint dosage-sensitive genes that disrupt key developmental pathways, suggesting new therapeutic avenues for ameliorating associated phenotypes [28].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The experimental strategies discussed rely on a suite of core reagents and tools that enable precise genetic manipulation.

Table 3: Key research reagents and solutions for modulation of gene expression.

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| siRNA / shRNA | Synthetic double-stranded RNAs for transient (siRNA) or stable (shRNA) gene knockdown via the RNAi pathway [25] [29]. | Knockdown of EpCAM in colorectal cancer cells to study migration [31]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | A versatile system using a Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA (gRNA) for targeted gene knockout. Can be adapted for knockdown (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) [13] [25]. | Dual genome-wide screens for ATR inhibitor resistance genes [13]. |

| Morpholino Oligos | Stable antisense oligonucleotides that block mRNA translation or splicing; ideal for embryonic studies [26]. | Gene knockdown in zebrafish models for developmental biology [26]. |

| Plasmid Vectors | Engineered DNA constructs for delivering genes (for overexpression) or shRNA sequences (for knockdown) into cells [31] [30]. | pCDH-EpCAM for overexpression; pGMC-KO-EpCAM for knockdown [31]. |

| Transfection Reagents | Lipid-based or other reagents that facilitate the uptake of nucleic acids (siRNA, plasmids) into cultured cells [29]. | siLenFect for siRNA delivery into MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells [29]. |

| The Double UP Plasmid | A dual-fluorescent plasmid that, when co-transfected with limiting Cre, generates internal control and experimental cell populations in a single culture [30]. | Controlling for variability in in utero electroporation experiments studying neuronal migration [30]. |

Visualizing the Core Concepts and Workflows

How Gene Dosage Reveals Function

This diagram illustrates the fundamental biological rationale that underpins both overexpression and knockdown studies. It shows how deviations from normal gene expression levels can lead to observable phenotypic changes, thereby revealing the gene's function.

Dual CRISPR Screening Workflow

This flowchart outlines the integrated experimental pipeline for conducting dual genome-wide CRISPR knockout and activation screens, as used to identify mechanisms of drug resistance.

Key Signaling Pathway in a Functional Study

This diagram summarizes a key signaling pathway identified through overexpression/knockdown studies, showing how a target gene (P2X7R) influences cancer hallmarks through specific molecular cascades.

In functional genomics, researchers employ two powerful, complementary approaches to decipher gene function: overexpression and knockdown. Overexpression (or activation) screens investigate the consequences of increasing a gene's expression level, revealing insights into gene function when it is amplified or activated. Conversely, knockdown (or knockout) screens reduce or abolish gene expression to understand a gene's normal function by observing the phenotypic consequences of its loss. While often used independently, when applied in tandem, these strategies provide a more complete picture of gene function and its role in biological systems, from fundamental cellular processes to disease mechanisms and therapeutic development. This guide objectively compares the performance, applications, and experimental outcomes of these two foundational approaches in modern biological research.

Core Conceptual Frameworks and Biological Questions

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Overexpression and Knockdown Approaches

| Feature | Overexpression/Activation | Knockdown/Knockout |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Identify genes whose increased activity induces a phenotype (e.g., drug resistance, pathogen restriction). | Identify genes whose loss induces a phenotype (e.g., cell death, sensitization to a drug). |

| Typical Screen Output | Hits that confer a selective advantage (e.g., survival, growth). | Hits that confer a selective disadvantage or synthetic lethality. |

| Key Biological Questions | What genes can drive a specific process or cellular state when activated? What genes can suppress a phenotype when overexpressed? | What genes are essential for a specific process or for cell survival? What genes enhance a phenotype when lost? |

| Common Technologies | cDNA libraries, ORF archives, CRISPR activation (CRISPRa). | RNAi (siRNA, shRNA), CRISPR knockout (CRISPRko). |

Experimental Designs and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols

The choice of experimental protocol is critical for the success and interpretation of both overexpression and knockdown screens.

Protocol 1: Dual Genome-Wide CRISPR Knockout and Activation Screening This protocol, as employed in a study investigating resistance to ATR inhibitors, leverages the power of CRISPR technology to simultaneously probe loss-of-function and gain-of-function phenotypes in a single, integrated workflow [13].

- 1. Library Design:

- 2. Cell Transduction: Transduce a population of cells (e.g., HeLa, MCF10A) with the lentiviral library at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) to ensure most cells receive a single genetic perturbation [13].

- 3. Selection Pressure: Apply a selective pressure, such as a drug (e.g., ATR inhibitors VE822 or AZD6738). The dose and duration are critical; high doses can be used to specifically select for resistant clones [13].

- 4. Hit Identification: Harvest surviving cells, amplify integrated sgRNAs via PCR, and perform next-generation sequencing (NGS). Bioinformatics tools (e.g., the RSA algorithm) are used to identify sgRNAs, and thus genes, that are significantly enriched or depleted in the treated population compared to a control [13].

Protocol 2: Overexpression Screen Using a Defined Gene Library This methodology is used to identify individual genes that can induce a specific phenotype, such as resistance to pathogen infection [32].

- 1. Library Cloning: Curate a library of genes of interest (e.g., 414 interferon-stimulated genes) into a lentiviral expression vector that often co-expresses a fluorescent marker like tagRFP for tracking [32].

- 2. Cell Transduction: Transduce target cells (e.g., A549 lung epithelial cells) with the library. A "one-gene-per-well" format in a plate-based assay is common for such focused screens [32].

- 3. Phenotypic Assay: Challenge the transduced cells with the stimulus (e.g., GFP-expressing Toxoplasma gondii) [32].

- 4. Automated Analysis: Use high-throughput automated microscopy and image analysis to quantitatively measure the phenotypic outcome (e.g., size and number of parasitophorous vacuoles) [32].

- 5. Hit Validation: Identify genes that potently restrict the phenotype (e.g., infection) and validate them through secondary assays in multiple cell lines [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Overexpression and Knockdown Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Knockout Library (e.g., Brunello) | A pooled library of sgRNAs for genome-wide loss-of-function screening [13]. | Identifying essential genes and drug sensitizers [13] [33]. |

| CRISPR Activation Library (e.g., Calabrese) | A pooled library of sgRNAs for targeted transcriptional activation of endogenous genes [13]. | Identifying genes that confer drug resistance or suppress phenotypes when overexpressed [13]. |

| ASKA Library (E. coli ORF Archive) | A complete set of E. coli open reading frames (ORFs) for overexpression screening [34]. | Genome-scale screening of beneficial upregulation targets in bacteria [34]. |

| Synthetic sRNAs (e.g., BHR-sRNA Platform) | Engineered small RNAs for targeted gene knockdown at the translational level in diverse bacteria [35]. | Knocking down virulence factors in pathogens or metabolic genes in industrial strains [35]. |

| Lentiviral Expression Vectors (e.g., pSUPER.retro) | Viral delivery systems for stable integration and expression of shRNAs or cDNAs in mammalian cells [36]. | Achieving stable, long-term gene knockdown or overexpression [36]. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | Technology to sort cells based on fluorescent markers, often used to isolate populations with desired phenotypes in screens [34]. | Enriching for cells with high production of a metabolite (e.g., free fatty acids) or specific surface markers [34]. |

Comparative Experimental Data and Outcomes

Direct comparisons and individual studies highlight the distinct yet complementary insights gained from overexpression and knockdown screens.

Table 3: Comparative Experimental Data from Overexpression and Knockdown Studies

| Study Context | Overexpression Findings | Knockdown Findings | Complementary Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) [27] | Overexpression of the P2X7 receptor promoted migration, invasion, and tumor growth of NSCLC cells, involving PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β and JNK pathways. | Knockdown of the P2X7 receptor suppressed proliferation, migration, invasion, promoted apoptosis, and inhibited tumor growth. | The P2X7 receptor functions as a consistent oncogenic driver; its bidirectional modulation validates it as a high-confidence therapeutic target. |

| ATR Inhibitor Resistance [13] | A genome-wide CRISPRa screen identified genes that, when overexpressed, confer resistance to ATR inhibitors (e.g., via restoring replication fork progression). | A parallel CRISPRko screen identified genes whose loss confers resistance to ATR inhibitors (e.g., by preventing apoptosis). | Dual screens revealed varied resistance mechanisms, providing a more comprehensive landscape of potential biomarkers for therapy. |

| Free Fatty Acid Production in E. coli [34] | Overexpression of rfaY (involved in LPS biosynthesis) increased FFA production by 207.8% by enhancing membrane stability and homeostasis. |

(Inferred) Knockdown of competing pathway genes would be used to redirect metabolic flux, but was not the focus of this specific overexpression screen. | Highlights how overexpression can be used to identify non-obvious, non-metabolic gene targets (membrane integrity) for enhancing bioproduction. |

| Bacterial Gene Knockdown [35] | (Not Applicable) | A broad-host-range synthetic sRNA platform achieved >50% knockdown of target genes in 12 diverse bacterial species, mitigating virulence and optimizing metabolism. | Demonstrates the robustness and wide applicability of knockdown tools across diverse organisms, which is crucial for comparative biology and engineering. |

Integrated Workflow and Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and complementary nature of the two approaches within a typical functional genomics investigation, leading to a unified biological insight.

The mechanistic insights gained from these screens are often visualized through signaling pathways. The study on the P2X7 receptor in NSCLC provides a clear example of how a single target can be interrogated from both directions to validate its role and mechanism [27].

Overexpression and knockdown screens are not opposing strategies but are fundamentally complementary. As the experimental data demonstrates, knockdown screens excel at identifying genes that are essential for a biological process, revealing vulnerabilities and core components of pathways. Overexpression screens, in contrast, are powerful for discovering genes that are sufficient to drive a process, uncovering potential oncogenes, resistance mechanisms, and limiting factors in biosynthetic pathways.

The most powerful insights emerge when these approaches are used in tandem. The dual CRISPR screen on ATR inhibitor resistance is a prime example, where both methods identified resistance genes but through entirely different mechanisms [13]. Similarly, the bidirectional modulation of the P2X7 receptor provides a more robust and validated conclusion about its function in cancer than either approach could alone [27].

A critical consideration in interpreting these screens is the potential for non-specific or confounding effects. A notable analysis of LINCS L1000 data revealed that transcriptional profiles from knocking down and overexpressing the same gene were often positively correlated, contrary to the intuitive expectation of anticorrelation [10]. This highlights a "not a happy cell" effect, where perturbations can induce a general stress response, underscoring the necessity for careful validation through secondary assays, such as the CelFi assay for cellular fitness [33].

In conclusion, the strategic selection between overexpression and knockdown—or better yet, their integrated application—provides a powerful toolkit for deconstructing complex biological systems. For researchers in drug development, this combined approach is indispensable for target identification, understanding mechanism of action, and anticipating resistance, ultimately paving the way for more effective and personalized therapeutic strategies.

From Theory to Bench: Implementing Modern Overexpression and Knockdown Screens

Traditional genetic screens have long relied on methods that create permanent, binary changes—either completely disrupting a gene's function, as with CRISPR knockout (CRISPRko), or introducing exogenous genetic material for overexpression. While powerful, these approaches have inherent limitations. The advent of CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) has revolutionized functional genomics by enabling reversible, tunable, and precise control over endogenous gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [37]. These technologies use a catalytically deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) that acts as a programmable DNA-binding platform, directing transcriptional effector domains to specific gene promoters to either enhance (CRISPRa) or repress (CRISPRi) transcription [38]. This shift from permanent editing to transient modulation is particularly valuable for studying essential genes, modeling drug actions, understanding complex genetic networks, and conducting sensitive screens in disease-relevant cell types. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of CRISPRa and CRISPRi, detailing their mechanisms, performance data against alternative technologies, and practical protocols for their implementation in research and drug development.

Fundamental Mechanisms of CRISPRa and CRISPRi

The Core System: dCas9 and Transcriptional Effectors

At the heart of both CRISPRa and CRISPRi is the catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9). Through point mutations (D10A and H840A in S. pyogenes Cas9), the nuclease activity of Cas9 is abolished, transforming it into a programmable DNA-binding protein that can be precisely targeted to any genomic locus using a guide RNA (gRNA) [38] [37]. The fundamental difference between CRISPRa and CRISPRi lies in the transcriptional effector domains fused to dCas9.

CRISPRi (Interference): For gene repression, dCas9 is typically fused to repressor domains such as the Krüppel-associated box (KRAB). KRAB recruits repressive chromatin-modifying complexes, leading to histone methylation and the formation of heterochromatin, which effectively silences gene transcription [38] [22] [37]. The dCas9-KRAB fusion binds to the transcription start site (TSS), sterically hindering the binding of RNA polymerase and other transcriptional machinery.

CRISPRa (Activation): For gene activation, dCas9 is fused to transcriptional activators. Early systems used simple domains like VP64 (a tetramer of VP16). However, more potent systems have been developed that recruit multiple distinct activator domains simultaneously. Key advanced systems include [38] [22]:

- SAM (Synergistic Activation Mediator): dCas9-VP64 is co-expressed with a modified gRNA containing MS2 RNA aptamers. These aptamers recruit effector proteins (p65 and HSF1 activation domains fused to the MS2 coat protein), creating a powerful multi-component activator complex [38] [22].

- VPR: A tripartite activator directly fused to dCas9, comprising VP64, the p65 subunit of NF-κB, and the Rta transactivator from Epstein-Barr virus [22].

- SunTag: This system uses a dCas9 fused to an array of peptide epitopes (GCN4). These epitopes recruit multiple copies of an antibody single-chain variable fragment (scFv) fused to VP64, thereby amplifying the activation signal [22] [37].

The following diagram illustrates the core components and mechanisms of these systems.

Optimized Guide RNA (gRNA) Design

A critical factor for the success of CRISPRa/i experiments is the design of the gRNA. Unlike CRISPRko, where gRNAs are typically designed to target early exons, CRISPRa and CRISPRi require targeting specific regions relative to the transcription start site (TSS) [38].

- CRISPRi gRNA Design: The optimal window for CRISPRi repression spans from -50 to +300 base pairs (bp) from the TSS, with the most effective gRNAs targeting the first 100 bp downstream of the TSS [38]. This positioning allows dCas9-KRAB to effectively block the assembly of the transcription machinery.

- CRISPRa gRNA Design: For CRISPRa activation, the optimal targeting window is typically -400 to -50 bp upstream of the TSS [38]. This region often contains promoter and enhancer elements where activator complexes can most effectively recruit the transcriptional machinery.

Systematic tiling screens have led to the development of sophisticated algorithms that incorporate chromatin accessibility, nucleosome positioning, and sequence features to predict highly active gRNAs [39]. This has enabled the creation of optimized, genome-wide libraries such as Calabrese (CRISPRa) and Dolcetto (CRISPRi), which achieve high performance with a compact design of 3-10 gRNAs per gene [40].

Performance Comparison with Alternative Technologies

CRISPRi vs. RNAi and CRISPRko

CRISPRi offers several distinct advantages over RNA interference (RNAi) and traditional CRISPR knockout (CRISPRko) for loss-of-function studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Loss-of-Function Technologies

| Feature | CRISPRi | RNAi | CRISPR Knockout (CRISPRko) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | dCas9-repressor blocks transcription at the DNA level [38] [37] | siRNA/miRNA mediates mRNA degradation in the cytoplasm [38] [22] | Cas9 nuclease induces double-strand breaks, leading to frameshift mutations [38] |

| Efficiency & Robustness | High; more robust phenotypes in large-scale screens with fewer off-targets [38] [39] | Variable; prone to incomplete knockdown and off-target effects [38] | High for complete gene disruption |

| Reversibility | Reversible and titratable [37] | Reversible | Permanent |

| Toxicity/Genomic Impact | Minimal; no DNA damage, avoids genomic instability [38] [39] | Minimal | High; can induce cytotoxicity and genomic instability from DNA breaks [38] |

| Target Range | Coding & non-coding genes (lncRNAs) [38] [22] | Primarily coding genes; less efficient for nuclear RNA [38] | Coding & non-coding regions (requires large deletions for some) [38] |

| Application in Essential Gene Studies | Ideal; allows partial knockdown without cell death [38] | Suitable | Suboptimal; complete knockout can be lethal [38] |

Key Comparative Insights:

- CRISPRi vs. RNAi: CRISPRi generates more robust and reliable phenotypes in large-scale screens. It outperforms RNAi by avoiding the off-target effects associated with displacing endogenous small RNAs from the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) [38]. Furthermore, CRISPRi can efficiently target long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which are often difficult to study with RNAi [22].

- CRISPRi vs. CRISPRko: CRISPRko is a powerful tool for generating complete and permanent loss-of-function. However, the double-strand breaks it introduces can be cytotoxic and confound screens with DNA damage response phenotypes [38] [39]. CRISPRi, by avoiding DNA cleavage, circumvents this issue and is superior for studying essential genes, as cells can often tolerate a partial knockdown but not a complete knockout [38]. A screen in K562 cells demonstrated that the optimized Dolcetto CRISPRi library performed comparably to the Brunello CRISPRko library in detecting essential genes, highlighting its efficacy [40].

CRISPRa vs. ORF Overexpression

For gain-of-function studies, CRISPRa provides a compelling alternative to traditional open reading frame (ORF) overexpression.

Table 2: Comparison of Gain-of-Function Technologies

| Feature | CRISPRa | ORF Overexpression |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Activates endogenous gene from its native genomic context [37] | Introduces exogenous cDNA copy, often driven by a strong viral promoter (e.g., CMV) [38] [22] |

| Expression Level | Physiological or near-physiological; supraphysiological levels are challenging to achieve [38] | Often supraphysiological, non-physiological |

| Splice Variant Expression | Activates the gene's natural splice variants [38] | Typically overexpresses a single, predefined splice variant |

| Genomic Context | Endogenous; preserves native regulatory elements & chromatin environment [41] | Ectopic; subject to positional effects from random integration |

| Library Scalability | Highly scalable; easier and more cost-effective to synthesize genome-wide libraries [38] | More difficult and expensive to synthesize at genome scale |

Key Comparative Insights:

- Physiological Relevance: CRISPRa upregulates genes in their native genomic context, preserving natural splicing and regulatory elements. This often results in more physiologically relevant expression levels compared to the frequently supraphysiological levels driven by strong viral promoters in ORF overexpression [38] [37]. This makes CRISPRa better suited for modeling diseases and processes where correct gene dosage is critical.

- Comprehensive Screening: CRISPRa is more likely to upregulate the most relevant splice variants, which is particularly advantageous when these are unknown [38]. Furthermore, the synthesis of genome-scale CRISPRa libraries is more straightforward and cost-effective than creating comprehensive ORF libraries [38]. In a direct comparison, the Calabrese CRISPRa library identified more vemurafenib resistance genes than an ORF overexpression screen [40].

Quantitative Performance of Optimized Libraries

The development of optimized sgRNA design rules has led to significant performance improvements in CRISPRa/i screens. The table below summarizes key metrics from validated, genome-scale libraries.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Optimized Genome-wide Libraries

| Library Name | Modality | Key Design Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brunello [40] | CRISPRko | 4 sgRNAs/gene; designed with Rule Set 2 | Outperformed earlier libraries (GeCKO, Avana); high distinction between essential/non-essential genes (dAUC metric) |

| Dolcetto [40] | CRISPRi | Compact design; optimized sgRNA selection | Performed comparably to CRISPRko (Brunello) in detecting essential genes; outperformed earlier CRISPRi libraries |

| Calabrese [40] | CRISPRa | Optimized sgRNA selection for activation | Identified more vemurafenib resistance genes than the SAM library approach |

| hCRISPRi-v2 [39] | CRISPRi | 5 or 10 sgRNAs/gene; incorporates chromatin and sequence features | Detected >90% of essential genes with minimal false positives; lacked non-specific toxicity from DNA breaks |

| hCRISPRa-v2 [39] | CRISPRa | 5 or 10 sgRNAs/gene; optimized for TSS targeting | Identified 60% more genes affecting growth upon overexpression than v1 library |

Experimental Protocols for CRISPRa/i Screening

The following workflow outlines the key steps for conducting a pooled CRISPRa or CRISPRi screen, a common application for identifying genes involved in a biological process of interest.

Detailed Methodologies

Step 1: Generate a Stable Helper Cell Line

- Objective: Create a cell line that stably expresses the dCas9-effector fusion (e.g., dCas9-KRAB for CRISPRi or dCas9-VPR for CRISPRa). This ensures uniform and consistent expression of the CRISPR machinery across the cell population [38] [42].

- Protocol:

- Select a Vector: Use lentiviral vectors optimized for efficient delivery and stable integration, such as those available from commercial suppliers (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich) [38].

- Transduce Cells: Transduce the target cells (e.g., HEK293, K562, or iPSCs) with the dCas9-effector lentivirus. For difficult-to-transfect cells, lentiviral transduction is the method of choice [38].

- Select and Validate: Apply antibiotics (e.g., puromycin, blasticidin) to select for successfully transduced cells. Validate expression of dCas9-effector via Western blot or fluorescence (if tagged with a reporter like BFP) [42]. For inducible systems, functionality must be validated upon addition of the inducer (e.g., doxycycline or trimethoprim) [42] [43].

Step 2: Deliver the sgRNA Library

- Objective: Introduce a pooled sgRNA library into the helper cell line at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive only one sgRNA [40].

- Protocol:

- Library Selection: Choose a genome-scale library (e.g., Calabrese for CRISPRa, Dolcetto for CRISPRi) or a custom, focused library [40].

- Lentiviral Production: Package the sgRNA library into lentiviral particles in HEK293T cells.

- Transduction: Transduce the helper cell line with the sgRNA library virus. Use a sufficient cell number to maintain ~500x coverage of the library to prevent stochastic loss of sgRNAs [40].

- Selection: Apply selection (e.g., puromycin) for 3-7 days to remove untransduced cells. This time point is often harvested as the "T0" baseline.

Step 3: Apply Selection Pressure and Phenotype Readout

- Objective: Culture the cell population under conditions that enrich for or against cells with specific genetic perturbations.

- Protocol:

- Proliferation/Survival Screen: Passage cells for a set duration (e.g., 2-3 weeks), harvesting population samples at multiple time points to track sgRNA dynamics [22].

- Drug Sensitivity Screen: Split the transduced cell population into treated (with drug/toxin) and untreated (vehicle) cohorts. Culture both in parallel for a defined period [22].

- FACS-Based Screen: Use fluorescent reporters or antibodies to sort cells based on a specific phenotype (e.g., surface marker expression, ROS levels) [22] [43].

- Single-Cell RNA-seq Readout: Use CROP-seq or similar methods to capture both the sgRNA identity and the whole transcriptome of single cells [42] [43].

Step 4: Harvest Genomic DNA and Sequence

- Objective: Quantify the relative abundance of each sgRNA in the final population(s) compared to the T0 baseline.

- Protocol:

- Harvest gDNA: Extract genomic DNA from all time points and experimental conditions using standard methods.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the sgRNA cassette from the genomic DNA using primers that add Illumina sequencing adapters and sample barcodes.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Pool the PCR products and sequence on an Illumina platform to obtain millions of reads, allowing for quantitative counting of each sgRNA [40].

Step 5: Bioinformatic Analysis and Hit Identification

- Objective: Identify sgRNAs and genes that are significantly enriched or depleted under the selection pressure.

- Protocol:

- Read Alignment: Map sequencing reads to the reference sgRNA library to generate count tables for each sgRNA in each sample.

- Normalization and Scoring: Use specialized algorithms (e.g., MAGeCK [43], pinAPL) to normalize counts and calculate fold-changes and statistical significance for each sgRNA and gene.

- Hit Calling: Genes with multiple sgRNAs showing consistent and significant depletion (in a loss-of-function screen) or enrichment (in a gain-of-function or resistance screen) are identified as high-confidence hits.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of a CRISPRa/i screen relies on a suite of key reagents and tools.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for CRISPRa/i Screens

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Examples & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Effector Construct | Core programmable DNA-binding platform fused to activator/repressor domains. | CRISPRi: dCas9-KRAB [38]. CRISPRa: dCas9-VPR, SAM system, SunTag system [22]. |

| Optimized sgRNA Library | Pooled guides targeting genes of interest; determines screen coverage and specificity. | Genome-wide: Calabrese (CRISPRa), Dolcetto (CRISPRi) [40]. Targeted: Custom libraries for specific pathways. Format: Lentiviral plasmid library. |

| Lentiviral Packaging System | Produces viral particles to deliver genetic material into target cells. | Second/third-generation systems (psPAX2, pMD2.G) for safe production of replication-incompetent virus. |

| Cell Line Engineering Tools | Reagents for selecting and validating stable cell lines. | Antibiotics for selection (puromycin, blasticidin); antibodies for validation (Western blot, FACS). |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Enables quantitative tracking of sgRNA abundance in pooled screens. | Illumina platforms; primers with unique barcodes for multiplexing samples [40]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | For analyzing screen data, normalizing counts, and identifying hit genes. | MAGeCK [43], CERES, pinAPL. |

CRISPRa and CRISPRi have firmly established themselves as premier tools for controlled genetic perturbation. Their ability to provide reversible, titratable, and precise modulation of endogenous gene expression offers a more nuanced and physiologically relevant approach compared to traditional knockout and overexpression methods. As demonstrated in diverse applications—from uncovering neuron-specific vulnerabilities in neurodegenerative disease [43] to identifying drivers of chemoresistance in cancer [22]—these technologies are unlocking new dimensions of biology.

The true power of CRISPRa and CRISPRi is often realized when they are used in combination. Parallel loss-of-function and gain-of-function screens can reveal complementary insights, such as identifying both tumor suppressors (which cause phenotypes when overexpressed) and essential oncogenes (which cause phenotypes when knocked down) in the same cell line [38] [22]. Furthermore, their integration with single-cell omics technologies is paving the way for high-resolution mapping of gene regulatory networks and their functional outcomes [42] [43].

As the field advances, future developments will focus on improving the efficiency and specificity of effector domains, expanding the toolset to include epigenetic modifiers, and adapting these platforms for in vivo therapeutic applications. For researchers and drug developers, mastering CRISPRa and CRISPRi is no longer a niche skill but a fundamental requirement for systematically interrogating gene function and accelerating the pace of discovery in the era of precision biology.

The choice between genome-wide and focused library designs represents a critical first step in the planning of functional genetic screens, directly influencing the scope, resolution, and resource requirements of a study. Genome-wide screens aim to interrogate every gene in the genome, offering an unbiased and comprehensive discovery platform. In contrast, focused screens target a predefined subset of genes—such as those encoding cell surface proteins, kinases, or other specific functional classes—to achieve higher depth, statistical power, and practical efficiency within a particular biological context. The decision is not merely a technicality but a strategic consideration that shapes the biological insights one can attain. Furthermore, the choice of perturbation technology—whether loss-of-function (e.g., CRISPR knockout, RNAi) or gain-of-function (e.g., ORF overexpression)—adds another layer of complexity, as each approach can reveal distinct and complementary aspects of gene function [44]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these different library design strategies, supported by experimental data, to inform their optimal application in biological research and drug development.

Comparative Performance of Screening Approaches

Genome-Wide vs. Focused CRISPR Screens

Direct comparative studies demonstrate that focused libraries can significantly enhance the efficiency of identifying relevant hits in specific biological processes. A systematic comparison of a genome-wide CRISPR library and a surfaceome-focused library (targeting 1,344 cell surface proteins) in a rhinovirus (RV) infection model revealed stark differences in performance. The surfaceome screen markedly outperformed the genome-wide screen, with a ~6-fold higher success rate in identifying hit genes crucial for viral infection [45].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Genome-Wide vs. Surfaceome CRISPR Screen

| Screening Metric | Genome-Wide Screen | Surfaceome Screen |

|---|---|---|

| Total Genes Targeted | 18,421 | 1,344 |

| Percentage of Genes with Significant Hits | 0.54% | 3.2% |

| Key Identified Hit | ICAM-1 (known receptor) | ICAM-1 & novel factor OLFML3 |

| Primary Advantage | Unbiased, comprehensive discovery | Higher hit rate and efficiency for a defined protein class |

Both screens successfully identified ICAM-1, the known receptor for major-group rhinoviruses, validating the approach. However, the surfaceome screen also robustly identified olfactomedin-like 3 (OLFML3) as a novel host dependency factor, a finding missed by the genome-wide screen under its standard significance thresholds. This demonstrates that focused designs can powerfully deconvolute complex biological processes by reducing background noise and increasing the detection sensitivity for relevant pathways [45].

Knockdown/Knockout vs. Overexpression Screens

Loss-of-function (LOF) and gain-of-function (GOF) screens represent complementary approaches for dissecting gene function. LOF screens (using CRISPR knockout or RNAi) identify genes whose activity is necessary for a phenotype, revealing essential pathways and vulnerabilities. In contrast, GOF screens (using cDNA overexpression) identify genes that can drive or enhance a phenotype, uncovering potential activators or mechanisms of resistance.

A seminal systematic comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 knockout and shRNA-based knockdown screens in the K562 chronic myeloid leukemia cell line found that while both techniques effectively identified essential genes with high precision (AUC > 0.90), their results showed surprisingly low correlation and were enriched for distinct biological processes [44]. For example, CRISPR-Cas9 screens more strongly identified genes involved in the electron transport chain as essential, whereas shRNA screens more effectively pinpointed subunits of the chaperonin-containing T-complex. This indicates that each technology can access different aspects of biology, potentially due to differences in the timing and completeness of gene perturbation, or technology-specific off-target effects. Combining data from both LOF technologies using a statistical framework (casTLE) improved performance, yielding a more robust set of essential genes [44].

GOF screens are particularly powerful for discovering genes that can confer new functions or resistance to treatments. A genome-scale GOF screen using a library of nearly 12,000 barcoded human open reading frames (ORFs) in primary human T cells identified positive regulators of proliferation, such as the lymphotoxin beta receptor (LTBR) [46]. This approach is invaluable for engineering cell therapies, as it can uncover synthetic drivers that enhance desired effector functions. Dual genome-wide LOF and GOF screens for regulators of cellular resistance to ATR inhibitors (ATRi) further highlight the power of a combined strategy. This approach comprehensively identified genes that, when either knocked out or overexpressed, altered ATRi resistance, uncovering multiple mechanisms including regulation of apoptosis and replication fork stability [47].

Table 2: Comparison of Loss-of-Function and Gain-of-Function Screening Approaches

| Feature | Loss-of-Function (LOF) Screens | Gain-of-Function (GOF) Screens |

|---|---|---|

| Perturbation Type | CRISPR knockout, CRISPRi, RNAi | CRISPR activation (CRISPRa), cDNA ORF overexpression |

| Biological Question | What genes are necessary for a phenotype? | What genes can induce or enhance a phenotype? |

| Typical Library | sgRNAs or shRNAs targeting all genes | sgRNAs for activation or ORF clones |

| Key Applications | Identifying essential genes, drug targets, vulnerability factors | Discovering synthetic drivers, resistance mechanisms, therapeutic genes |

| Complementary Insight | Identifies MED12 as an ATRi resistance factor when knocked out [47] | Identifies LTBR as a driver of T-cell proliferation when overexpressed [46] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Screen Types

Protocol 1: Focused Surfaceome CRISPR Knockout Screen

This protocol is adapted from the screen that identified OLFML3 as a rhinovirus host factor [45].

- Library Design: Construct a focused sgRNA library targeting a curated set of genes encoding cell surface proteins. The library used in the cited study contained 16,975 sgRNAs targeting 1,344 surface proteins, with 12 sgRNAs per gene to ensure robust coverage [45].

- Library Production: Package the sgRNA library into lentiviral particles. Titrate the virus to determine the multiplicity of infection (MOI).

- Cell Line Engineering: Transduce the target cell line (e.g., H1-Hela cells for rhinovirus infection) with the lentiviral library at a low MOI (e.g., 0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA. Select transduced cells with puromycin for 7-10 days.

- Phenotypic Selection:

- Split the library-containing cells into experimental and control groups.

- Challenge the experimental group with the selective agent (e.g., rhinovirus RV-B14 at an MOI of 1.0).

- Maintain the control group under mock conditions.

- Culture cells for the duration of the selection period (e.g., 48 hours for RV-induced cell death).

- Sample Collection and Sequencing: Harvest genomic DNA from the surviving cells in the experimental group and from the control group. PCR-amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences and subject them to next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Use specialized algorithms (e.g., MAGeCK) to compare the abundance of each sgRNA in the experimental group versus the control. Significantly enriched sgRNAs indicate genes whose knockout confers a survival advantage, pointing to key host factors [45].

Protocol 2: Genome-Wide ORF Overexpression Screen

This protocol is based on the screen that identified LTBR as a synthetic driver of T-cell proliferation [46].

- Library Design: Utilize a genome-wide ORF library, such as one containing ~12,000 full-length human ORFs, each tagged with multiple unique DNA barcodes to track individual clones [46].

- Cell Transduction: Transduce the target cells (e.g., primary human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from multiple donors) with the ORF library at a low MOI. Use a cell number that ensures high coverage of the library (e.g., 200-fold coverage).

- Phenotypic Selection:

- Stimulate the transduced T cells via the T-cell receptor (e.g., using anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies).

- Culture the cells for a defined period (e.g., 14 days) to allow for proliferation.

- Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate the top fraction of cells exhibiting the highest proliferation (e.g., based on dye dilution) or activation (e.g., based on surface marker expression).

- Barcode Sequencing and Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from the sorted population and the unsorted control population. Amplify and sequence the ORF-associated DNA barcodes. Identify significantly enriched barcodes (and thus ORFs) in the sorted population compared to the control using statistical methods. Enriched ORFs represent genes that enhance T-cell proliferation upon overexpression [46].

Visualization of Screening Strategies and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows and conceptual relationships between the different screening strategies discussed in this guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of high-quality genetic screens relies on a suite of well-validated reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials used in the featured studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Screens

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Screening | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Knockout Library | Enables systematic gene disruption via Cas9-induced double-strand breaks. | GeCKO v2 library [48]; Brunello library [47]. Designed with 4-12 sgRNAs/gene to ensure robustness. |

| ORF Overexpression Library | Enables systematic gene activation through expression of full-length cDNA. | Lentiviral library of ~12,000 barcoded human ORFs [46]. Allows tracking of clones via unique barcodes. |

| Lentiviral Delivery System | Efficiently delivers genetic perturbation elements (sgRNAs, ORFs) into a wide variety of cell types, including primary and non-dividing cells. | Used in nearly all cited studies [45] [46] [48]. |