Overcoming Class Imbalance in Drug-Target Interaction Prediction: Strategies, Benchmarks, and Future Directions

Accurate prediction of Drug-Target Interactions (DTIs) is crucial for accelerating drug discovery, yet it is severely challenged by class imbalance, where known interacting pairs are vastly outnumbered by non-interacting ones.

Overcoming Class Imbalance in Drug-Target Interaction Prediction: Strategies, Benchmarks, and Future Directions

Abstract

Accurate prediction of Drug-Target Interactions (DTIs) is crucial for accelerating drug discovery, yet it is severely challenged by class imbalance, where known interacting pairs are vastly outnumbered by non-interacting ones. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational causes and impacts of this imbalance. It details a suite of computational solutions, from data-level resampling techniques like SMOTE and GANs to algorithm-level approaches such as cost-sensitive learning and specialized deep learning architectures. The content further offers practical guidance for troubleshooting model performance and presents a rigorous framework for validating and benchmarking new methods against established standards, ultimately outlining a path toward more robust and predictive computational models in biomedicine.

The Class Imbalance Problem: Why Drug-Target Interaction Prediction is Inherently Biased

Defining Between-Class and Within-Class Imbalance in DTI Datasets

Frequently Asked Questions

What is class imbalance in Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) prediction? In DTI datasets, class imbalance occurs when the number of confirmed interacting pairs (the positive or minority class) is much smaller than the number of non-interacting or unlabeled pairs (the negative or majority class). This is a fundamental challenge because standard classification models become biased toward the majority class, making them poor at identifying the rare, but crucial, interacting pairs [1] [2].

What is the difference between "Between-Class" and "Within-Class" imbalance? This is a critical distinction for diagnosing issues in your dataset:

- Between-Class Imbalance: This is the overall skew in the dataset, where the total number of negative samples far exceeds the total number of positive samples [1]. It is the most commonly recognized form of imbalance.

- Within-Class Imbalance: This is a more subtle issue where, even within a single class (e.g., the minority positive class), there is a significant disparity in the representation of different subtypes. For instance, in the positive class, interactions for certain types of proteins (like enzymes) may be well-represented, while interactions for others (like nuclear receptors) are very rare [1].

Why is a model with high accuracy potentially misleading for DTI prediction? On a severely imbalanced dataset, a naive model that simply predicts "no interaction" for every drug-target pair will achieve a very high accuracy because it is correct for the vast majority of samples. However, its performance on the minority class of interest (the interactions) will be zero. This is why accuracy is a poor metric, and you should rely on metrics like the F1-score, Precision, Recall, and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) [3].

What are the most common strategies to mitigate class imbalance? The two primary categories of solutions are:

- Data-Level Strategies: These involve modifying the training dataset to create a more balanced class distribution. This includes random undersampling of the majority class, random oversampling of the minority class, and advanced synthetic oversampling techniques like SMOTE [4] [3].

- Algorithm-Level Strategies: These involve modifying the learning algorithm itself to compensate for the imbalance. This can include using ensemble methods like BalancedBaggingClassifier [3], adjusting class weights in the model's loss function [5], or employing specialized deep learning architectures designed for imbalanced data [1] [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My Model is Biased and Fails to Predict Any Interactions

Description After training, your model's predictions are skewed entirely towards the majority (non-interacting) class. It has effectively "given up" on learning to identify true drug-target interactions.

Diagnosis Steps

- Check Class Distribution: Calculate the ratio of negative to positive samples in your training set. A ratio higher than 10:1 indicates a severe between-class imbalance that requires intervention [1].

- Evaluate with Robust Metrics: Stop using accuracy. Instead, evaluate your model using a confusion matrix, precision, recall, and the F1-score for the positive class. A high accuracy with a recall of zero for the positive class confirms the bias [3].

- Perform EDA for Within-Class Issues: Cluster your positive samples based on protein family (e.g., Enzymes, GPCRs, Ion Channels) or drug properties. A highly uneven distribution among clusters signals a within-class imbalance problem [1].

Solutions

- For Between-Class Imbalance:

- Random Undersampling: Randomly remove samples from the majority class until the classes are balanced. This is computationally efficient but may discard potentially useful information [4] [3].

- Synthetic Oversampling (SMOTE): Generate new, synthetic examples for the minority class by interpolating between existing minority class instances. This creates a balanced dataset without simple duplication [3].

- Ensemble with Undersampling: To mitigate information loss from undersampling, train multiple deep learning models. In each model, keep all positive samples but use a different random subset of the negative samples. Then, aggregate the predictions [1].

- For Within-Class Imbalance:

- Cluster-Based Oversampling: Apply oversampling techniques (like SMOTE) not to the entire positive class, but separately within each underrepresented cluster of positive samples. This ensures all subtypes of interactions are adequately represented [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Data-Level Resampling Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Undersampling [4] [3] | Removes majority class examples at random. | Reduces dataset size, faster training. | Can discard useful data, potential loss of model performance. | Very large datasets where the majority class is vastly redundant. |

| Random Oversampling [4] [3] | Duplicates minority class examples at random. | Simple, no loss of information. | Can lead to overfitting due to exact copies of data. | Small datasets where the minority class is very small. |

| SMOTE [3] | Creates synthetic minority class examples via interpolation. | Increases diversity, reduces risk of overfitting. | May generate noisy samples if the feature space is complex. | Datasets with a moderately sized minority class and clear feature manifolds. |

| Ensemble + RUS [1] | Trains multiple models on different balanced subsets. | Mitigates information loss from undersampling. | Computationally more expensive. | Complex, high-value datasets where preserving all possible signals is critical. |

Problem: How to Systematically Design an Experiment to Address Imbalance

Description You need a reliable, reproducible protocol to test different imbalance mitigation strategies on your specific DTI dataset.

Experimental Protocol

1. Data Preparation and Feature Engineering

- Dataset: Use a standard benchmark like BindingDB [1] [2]. Define a binding affinity threshold (e.g., IC50 < 100 nM) to label positive and negative interactions [1].

- Feature Extraction:

- Splitting: Split the data into training (85%) and testing (15%) sets. Crucially, apply resampling techniques ONLY to the training set to avoid data leakage and obtain a realistic evaluation on the original, imbalanced test set [4].

2. Implement and Compare Strategies Train your chosen model (e.g., Random Forest, Deep Neural Network) on multiple versions of the training data:

- Baseline: The original, imbalanced training set.

- Strategy A: Training set after Random Undersampling.

- Strategy B: Training set after SMOTE oversampling.

- Strategy C: Training set after a combined approach (e.g., SMOTE followed by Tomek Links cleaning [4]).

3. Evaluation and Model Selection

- Evaluate all models on the same, untouched imbalanced test set.

- Use a table to compare key metrics. Prioritize Sensitivity (Recall) and F1-score for the positive class, as they are more informative than accuracy in this context [3]. The Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC) is also useful, but the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) is often more telling for imbalanced problems [1].

Table 2: Key Metrics for Evaluating DTI Models on an Imbalanced Test Set

| Metric | Formula / Principle | Interpretation in DTI Context |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (Recall) | ( \frac{TP}{TP+FN} ) | The model's ability to correctly identify true drug-target interactions. A low value means many interactions are missed. |

| Precision | ( \frac{TP}{TP+FP} ) | The reliability of the model's positive predictions. A low value means many predicted interactions are false leads. |

| F1-Score | ( 2 \times \frac{Precision \times Recall}{Precision + Recall} ) | The harmonic mean of precision and recall. A single balanced metric to optimize for. |

| Specificity | ( \frac{TN}{TN+FP} ) | The model's ability to correctly identify true non-interactions. |

| AUC-ROC | Area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve. | Measures the model's overall ability to distinguish between classes across all thresholds. |

| AUPRC | Area under the Precision-Recall curve. | More informative than AUC-ROC when the positive class is rare; focuses on performance for the class of interest. |

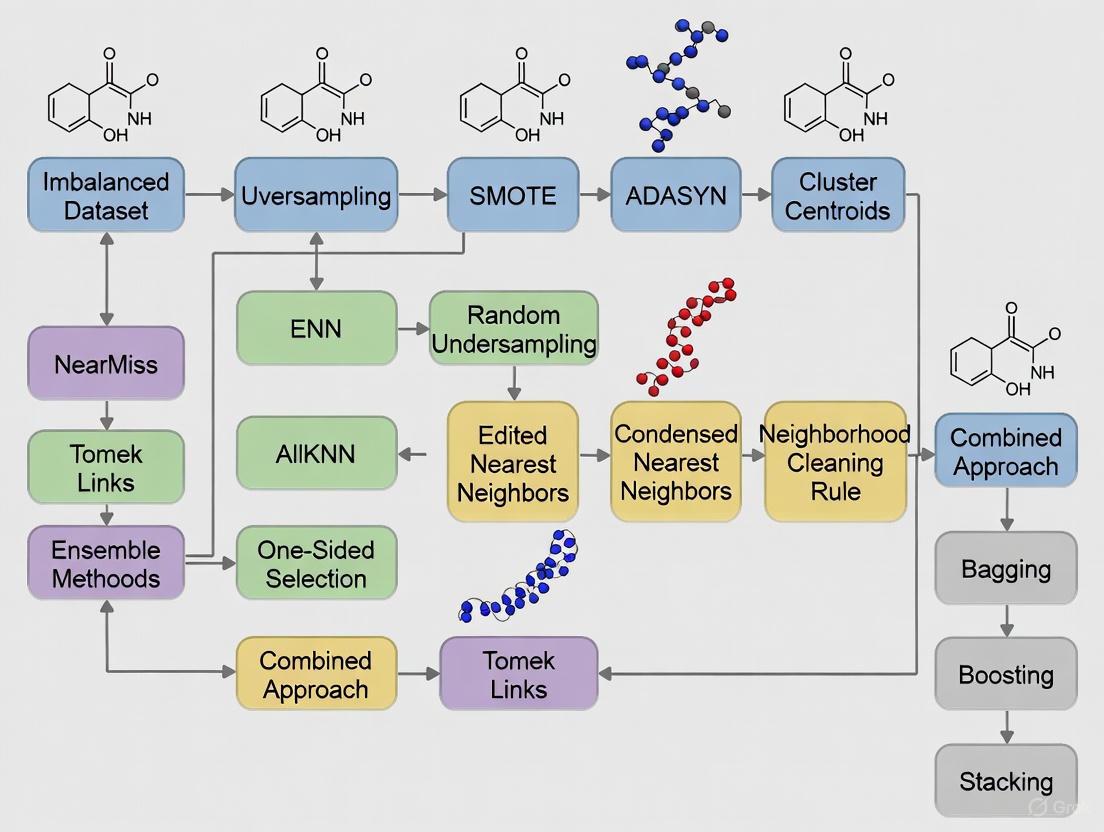

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental protocol for addressing class imbalance in DTI datasets.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for DTI Imbalance Research

| Item Name | Type | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| BindingDB [1] [2] | Dataset | A public, curated database of measured binding affinities for drug-target pairs. Serves as the primary source for positive and negative interaction labels. |

| imbalanced-learn [4] [3] | Python Library | Provides a wide range of resampling techniques, including RandomUnderSampler, RandomOverSampler, and SMOTE, for easy implementation of data-level solutions. |

| MACCS Keys / ErG Fingerprints [1] [2] | Drug Feature | A method to encode the molecular structure of a drug compound into a fixed-length binary bit vector, representing the presence or absence of specific substructures. |

| Amino Acid / Dipeptide Composition [1] [2] | Target Feature | A simple yet effective method to represent a protein sequence by its relative composition of single amino acids or pairs of adjacent amino acids. |

| BalancedBaggingClassifier [3] | Algorithm | An ensemble method that combines bagging with internal resampling to balance the data for each base estimator, directly tackling the class imbalance. |

| F1-Score & AUPRC [1] [3] | Evaluation Metric | The critical metrics for evaluating model performance, focusing on the correct identification of the minority (interacting) class rather than overall accuracy. |

Why is Class Imbalance a Critical Problem in Drug-Target Interaction Prediction?

A: Class imbalance is a fundamental challenge in drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction because the number of known interacting pairs is vastly outnumbered by non-interacting pairs. This creates a significant bias in machine learning models, causing them to prioritize predicting "non-interaction" to achieve deceptively high accuracy, while performing poorly at identifying the rare but crucial "interacting" pairs, which are the primary focus of drug discovery [7] [8]. If unaddressed, this imbalance degrades the predictive performance for the minority class of interacting pairs, leading to more false negatives and hindering the identification of new drug candidates [9].

What Are the Typical Imbalance Ratios in Publicly Available DTI Databases?

A: The imbalance ratios in popular DTI databases are severe. The table below summarizes the documented statistics, which illustrate the scale of the challenge.

| Database | Total Interactions | Number of Drugs | Number of Targets | Documented Imbalance Ratio (Non-interacting : Interacting) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DrugBank (v4.3) | 12,674 [7] [8] | 5,877 [7] [8] | 3,348 [7] [8] | Not explicitly stated, but the ratio is inherently high due to the combinatorial possibility of drug-target pairs. |

| BindingDB (Various Affinity Measures) | Not Explicitly Stated | Not Explicitly Stated | Not Explicitly Stated | ~99:1 (Approximated from dataset characteristics used in research) [9] |

Experimental Context from Research:

Research utilizing the BindingDB database often curates specific datasets for DTI prediction. One such study using a dataset derived from BindingDB reported an extreme imbalance where non-interacting pairs outnumbered interacting pairs by a factor of approximately 99 to 1 [9]. This level of imbalance is a typical characteristic of real-world DTI data and poses a major obstacle for predictive modeling.

What Experimental Protocols Are Used to Quantify and Address This Imbalance?

A: Researchers employ specific computational workflows to first quantify the imbalance and then apply techniques to mitigate its effects. The following diagram illustrates a general experimental protocol for handling class imbalance in DTI prediction.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Steps:

1. Data Representation (Drug & Target Feature Extraction):

- Drug Features: Molecular structures are converted into fixed-length numerical vectors. Common methods include:

- MACCS Keys: A set of binary fingerprints (0/1) indicating the presence or absence of specific chemical substructures and functional groups [9].

- Molecular Descriptors: Software packages like

Rcpiin R are used to calculate constitutional, topological, and geometrical descriptors that capture various molecular properties [7] [8].

- Target Features: Protein sequences are also converted into numerical descriptors using tools like the PROFEAT web server. Computed features include [7] [8]:

- Amino acid composition.

- Dipeptide composition.

- Autocorrelation descriptors.

- Quasi-sequence-order descriptors.

2. Imbalance Handling Techniques:

- Data-Level - Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): GANs are used to generate synthetic, but realistic, feature vectors for the minority class (interacting pairs). This artificially balances the dataset before training. A study using GANs with a Random Forest classifier on BindingDB data reported significant performance improvements, achieving accuracy over 97% [9].

- Algorithmic-Level - Ensemble Learning: This method involves creating multiple models. It first addresses between-class imbalance by using multiple balanced subset models of the majority class. It then tackles within-class imbalance (where some types of interactions are rarer than others) by using clustering to identify these "small disjuncts" and artificially enhancing them via oversampling to ensure the model learns these rare concepts [7] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in DTI Research |

|---|---|---|

| DrugBank | Database | A comprehensive repository containing chemical, pharmacological, and pharmaceutical drug data along with comprehensive drug target information [7] [8]. |

| BindingDB | Database | A public database of measured binding affinities, focusing primarily on interactions between drug-like chemicals and proteins deemed to be drug targets [9]. |

| PROFEAT | Web Server | Computes a comprehensive set of numerical descriptors for proteins and peptides directly from their amino acid sequences, enabling machine learning applications [7] [8]. |

| Rcpi | R Package | An R toolkit for generating various types of molecular descriptors and structural fingerprints from drug compounds, facilitating drug-centric feature extraction [7] [8]. |

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | Algorithm | A deep learning model used for data generation; in DTI, it creates synthetic data for the minority class to correct severe class imbalance [9]. |

In computational drug discovery, a model's high accuracy can be deceptive. A critical and often overlooked issue is class imbalance, where the number of inactive drug-target pairs in a dataset vastly outnumbers the active ones. This skew leads to models that are biased toward the majority class, failing to identify the rare but crucial active interactions that could lead to new therapies [10]. This technical guide addresses how to diagnose, troubleshoot, and resolve the problems caused by imbalanced data in your drug-target interaction (DTI) and drug-target affinity (DTA) prediction experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: My model has 95% accuracy, but my wet-lab team can't find any true active compounds. What's wrong?

Answer: High overall accuracy often masks poor performance on the minority class (active compounds) in imbalanced datasets. Standard accuracy is a biased metric when classes are skewed; a model can achieve over 90% accuracy by simply predicting "inactive" for every sample [11] [12]. This results in a high false negative rate, causing promising active compounds to be missed.

Solution:

- Use Robust Metrics: Replace accuracy with a suite of metrics that are sensitive to class imbalance.

- Prioritize: F1-score, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) [13] [12]. The table below summarizes key metrics to use.

| Metric | Description | Why Use It for Imbalanced Data? |

|---|---|---|

| F1-Score | Harmonic mean of precision and recall. | Balances the trade-off between finding all actives (recall) and ensuring predictions are correct (precision) [13]. |

| MCC | A correlation coefficient between observed and predicted classifications. | Considered a balanced measure that works well even on imbalanced datasets [13] [12]. |

| AUPR | Area under the Precision-Recall curve. | More informative than ROC-AUC when the positive class is rare [13]. |

| Balanced Accuracy | Average of recall obtained on each class. | Prevents over-optimistic estimates from the majority class [12]. |

FAQ 2: What are the most effective techniques to fix an imbalanced dataset for DTI prediction?

Answer: Both data-level and algorithm-level techniques are effective. Recent research indicates that random undersampling (RUS) of the majority class to a moderate imbalance ratio (e.g., 1:10) can be highly effective for highly skewed bioassay data [12].

Solution: A Comparison of Resampling Techniques The following table compares common resampling methods based on recent applications in cheminformatics.

| Technique | Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Undersampling (RUS) | Randomly removes majority class samples. | Simple, fast, can significantly boost recall & F1-score [12]. | Risks losing potentially useful data [10]. | Outperformed ROS and synthetic methods on highly imbalanced HIV, Malaria datasets [12]. |

| Synthetic Oversampling (SMOTE) | Creates synthetic minority class samples. | Mitigates overfitting from mere duplication [10]. | Can generate noisy samples; struggles with high dimensionality [10]. | Showed limited improvement in some DTI tasks; MCC lower than RUS in studies [12]. |

| NearMiss | Selectively undersamples majority class based on proximity to minority class. | Redizes computational cost and can improve recall [10] [12]. | Can discard critical majority class samples forming decision boundaries [10]. | Achieved highest recall but lowest precision and accuracy in validation [12]. |

FAQ 3: How can I ensure my model is fair and not biased against specific data subgroups?

Answer: Bias can manifest if a model performs well overall but poorly for a specific subset of targets or drug classes. Evaluating fairness metrics is essential for robust scientific models.

Solution:

- Define Facets: Identify potential subgroups in your data (e.g., different protein families or compound structural classes).

- Calculate Fairness Metrics: Use libraries like

AIF360orFairlearnto compute metrics such as Demographic Parity and Equal Opportunity [14]. - Interpretation: These metrics help answer questions like, "Does my model have an equal true positive rate across different protein families?" ensuring that predictive performance is equitable across the biological landscape [11] [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model is Overconfident and Unreliable in Real-World Screening

Explanation: Traditional deep learning models for DTI prediction often lack the ability to quantify uncertainty. They may produce a high prediction score for a novel drug-target pair that is actually outside the model's knowledge, leading to wasted experimental resources on false positives [13].

Solution: Implement Uncertainty Quantification (UQ)

- Method: Integrate Evidential Deep Learning (EDL) into your model architecture.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Modify the Output Layer: Replace the standard softmax output with a layer that parameterizes a Dirichlet distribution.

- Change the Loss Function: Use a loss function like the Dirichlet loss, which penalizes incorrect and uncertain predictions.

- Calculate Uncertainty: The model's output includes both a predictive probability and an uncertainty estimate (e.g., the entropy of the Dirichlet distribution).

- Application: In a framework like EviDTI, this allows the model to express "I don't know" for out-of-distribution samples. Predictions can then be prioritized by confidence, dramatically increasing the hit rate in experimental validation [13].

Problem: Poor Performance on New Drugs or Targets (The Cold-Start Problem)

Explanation: Models trained on imbalanced data often generalize poorly, especially for novel drugs or targets with no known interactions in the training set [13] [15].

Solution: Leverage Self-Supervised Pre-training

- Method: Use models pre-trained on large, unlabeled molecular and protein sequence databases (e.g., ProtTrans for proteins, MG-BERT or ChemBERTa for drugs) [13] [15] [16].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Feature Extraction: Use the pre-trained model to generate rich, contextual representations for all drugs and targets in your dataset.

- Transfer Learning: Fine-tune a downstream classifier (e.g., a simple neural network) on your smaller, labeled DTI dataset using these pre-trained features.

- Benefit: This approach provides the model with a strong foundational understanding of molecular and protein linguistics, helping it make better predictions on novel entities, even with limited labeled data [15]. The workflow below illustrates this process.

Experimental Workflow for Handling Imbalanced DTI Data

The following diagram illustrates a robust workflow that integrates the solutions discussed above to build a reliable DTI prediction model.

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent / Tool | Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| SMOTE / ADASYN | Software Algorithm | Generates synthetic samples of the minority class to balance datasets [10] [12]. |

| Random Undersampling (RUS) | Software Algorithm | Randomly removes samples from the majority class to achieve a desired imbalance ratio [12]. |

| Pre-trained Models (ProtTrans, ChemBERTa) | Software Library | Provides high-quality, contextual feature representations for proteins and drugs, improving model generalization [13] [16]. |

| Evidential Deep Learning (EDL) | Modeling Framework | Provides uncertainty estimates for predictions, allowing researchers to prioritize high-confidence candidates [13]. |

| Fairlearn / AIF360 | Software Library | Contains metrics and algorithms for assessing and improving fairness of models across subgroups [14]. |

| MCC (Matthews Correlation Coefficient) | Evaluation Metric | A single, balanced metric for evaluating classifier performance on imbalanced data [13] [12]. |

FAQs on Handling TWSNI in Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

What is a "Target with Few Known Interactions" and why is it a problem? A Target with Few Known Interactions (TWSNI) is a protein for which very few, or sparse, drug-target interactions have been experimentally confirmed [17]. This creates a significant "within-class imbalance" problem in machine learning. Unlike targets with many known interactions (TWLNI), TWSNI do not provide enough positive samples (known interactions) for a model to learn meaningful patterns, leading to poor prediction performance for these important but understudied targets [17].

What is the core computational strategy for improving TWSNI predictions? The most effective strategy is to use a different classification method for TWSNI than for TWLNI. For TWSNI, models must leverage information from "neighbor" targets—those that are biologically similar—by using the positive interaction samples from these neighbors to compensate for the lack of its own data [17]. This approach is a key part of multiple classification strategy methods like MCSDTI [17].

Beyond data-level fixes, what algorithmic approaches can help?

Using ensemble methods that are inherently more robust to class imbalance is beneficial. The BalancedBaggingClassifier is a prime example, as it combines bagging (bootstrap aggregating) with additional balancing during the training of each individual model in the ensemble [3]. This ensures that each classifier pays adequate attention to the minority class. Furthermore, adjusting class weights in your model to increase the penalty for misclassifying the rare TWSNI interactions can also improve performance [18].

Which evaluation metrics should I avoid and which should I use for TWSNI models? You should avoid using accuracy as a primary metric, as it is highly misleading with imbalanced data [18] [3]. Instead, use metrics that are sensitive to the performance on the minority class:

- Precision: Measures how many of the predicted TWSNI interactions are correct.

- Recall: Measures how many of the actual TWSNI interactions you managed to find.

- F1-score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single balanced metric [18] [3].

- AUC-ROC: Measures the model's ability to distinguish between interacting and non-interacting pairs across all thresholds and is insensitive to class imbalance [18].

What are the key differences in handling TWLNI vs. TWSNI?

| Feature | Targets with Larger Numbers of Interactions (TWLNI) | Targets with Smaller Numbers of Interactions (TWSNI) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Problem | Abundant positive samples [17] | Severe lack of positive samples (within-class imbalance) [17] |

| Primary Strategy | Predict interactions using their own sufficient data [17] | Predict interactions by leveraging data from similar "neighbor" targets [17] |

| Key Challenge | Sparsity of interactions in the drug-target pair space [17] | Positive samples are too few for a model to learn from effectively [17] |

| Independent Evaluation | Crucial to evaluate separately from TWSNI to see true performance [17] | Crucial to evaluate separately from TWLNI to prevent their results from being overwhelmed [17] |

Experimental Protocols for TWSNI Prediction

Protocol 1: Implementing the MCSDTI Framework

This protocol is based on the MCSDTI method, which uses multiple classification strategies [17].

1. Objective: To accurately predict drug-target interactions for both TWLNI and TWSNI by applying tailored classification strategies to each group.

2. Materials & Data Preprocessing:

- Datasets: Use established DTI datasets such as Nuclear Receptors (NR), Ion Channels (IC), GPCRs, or Enzymes (E) [17].

- Data Partitioning: Calculate the number of known interactions per target. Rank targets and split them into two groups:

- TWSNI: Targets with a number of interactions below a defined threshold (e.g., the median or a percentile).

- TWLNI: Targets with interactions above this threshold.

- Feature Extraction: For each drug-target pair, generate meaningful features. For drugs, this is often derived from their SMILES strings or molecular graphs. For targets, this is derived from their amino acid sequences or other protein descriptors [15].

3. Methodology:

- For TWLNI: Train a standard classifier (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) using only the known interactions for each specific TWLNI. The ample data for these targets makes this feasible [17].

- For TWSNI:

- Step 1 - Find Neighbors: For each TWSNI, identify a set of biologically similar "neighbor" targets based on protein sequence similarity or functional similarity.

- Step 2 - Aggregate Data: Pool the known positive interaction samples from the TWSNI with those from its identified neighbors to create an augmented training set.

- Step 3 - Train Model: Train a classifier on this augmented dataset to predict interactions for the specific TWSNI [17].

4. Independent Evaluation:

- Evaluate the prediction performance for TWLNI and TWSNI separately. This prevents the overall results from being dominated by the easier-to-predict TWLNI and provides a clear view of how well the method handles the challenging TWSNI [17].

Protocol 2: A Workflow for Handling Imbalanced DTI Data

This general protocol outlines steps to address class imbalance at both the data and algorithmic levels [18] [3].

1. Objective: To build a robust DTI prediction model that effectively identifies potential interactions for minority-class targets (TWSNI).

2. Data Resampling:

- Technique: Apply the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE).

- Procedure: Use the

imblearnlibrary in Python. SMOTE generates synthetic examples for the minority class (TWSNI interactions) by interpolating between existing minority class instances, rather than simply duplicating them [18] [3].

3. Algorithmic Approach:

- Technique: Use a Balanced Bagging Classifier.

- Procedure: Implement an ensemble model that combines the strengths of bagging with built-in balancing. This classifier trains multiple base estimators (e.g., Decision Trees) on balanced bootstrap samples of the data [3].

4. Model Evaluation:

- Metrics: Calculate Precision, Recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC on the test set [18] [3].

- Analysis: Use a confusion matrix to visually inspect the true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives, focusing on the model's performance on the minority TWSNI class [18].

Methodologies & Workflow Visualizations

MCSDTI Classification Strategy

This diagram illustrates the core decision process of the MCSDTI framework for handling different types of targets.

Multi-task Self-Supervised Learning for Cold Start

This diagram outlines the pre-training approach used by advanced frameworks like DTIAM to generate better representations for drugs and targets, which is particularly useful in cold-start scenarios like TWSNI.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| MCSDTI (Multiple Classification Strategy) | A computational framework that splits targets into TWSNI and TWLNI, applying a customized classification strategy for each group to optimize prediction [17]. |

| DTIAM | A unified framework that uses self-supervised learning on large amounts of unlabeled drug and target data to learn robust representations, improving predictions for DTI, binding affinity, and mechanism of action, especially in cold-start situations [15]. |

| SMOTE | A data-level technique that generates synthetic examples for the minority class (TWSNI interactions) to balance the dataset and reduce model bias [18] [3]. |

| BalancedBaggingClassifier | An ensemble algorithm that combines multiple base classifiers, each trained on a balanced bootstrap sample of the original data, making it inherently suited for imbalanced classification [3]. |

| Pre-training Models (Self-Supervised) | Models trained on large corpora of unlabeled molecular graphs and protein sequences. They learn general, powerful representations that can be fine-tuned for specific DTI tasks with limited labeled data, directly addressing the TWSNI data scarcity problem [15]. |

| F1-Score & AUC-ROC | Critical evaluation metrics that provide a truthful assessment of model performance on imbalanced datasets, focusing on the successful identification of the minority TWSNI class rather than misleading overall accuracy [18] [3]. |

A Toolkit of Solutions: From Data Resampling to Advanced Deep Learning

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why are data-level strategies like SMOTE or GANs necessary in drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction? In DTI prediction, the number of known interacting drug-target pairs (positive class) is vastly outnumbered by the number of non-interacting pairs (negative class). This is known as between-class imbalance [8]. Without correction, machine learning models become biased towards predicting the majority class (non-interacting), leading to poor performance in identifying therapeutically valuable interactions. Data-level strategies directly address this by synthetically creating new examples of the minority class to balance the dataset.

FAQ 2: My model has high accuracy but fails to predict any true drug-target interactions. What is happening? This is a classic symptom of class imbalance. Accuracy is a misleading metric when data is skewed. A model that simply predicts "non-interacting" for all examples will still achieve a high accuracy but is practically useless [19] [20]. You should switch to evaluation metrics that are more robust to imbalance, such as Precision, Recall, F1-Score, AUC-ROC, and especially AUC-PR [19] [20]. Furthermore, ensure you are using techniques like stratified sampling during train-test splits to preserve the class distribution in your validation sets [19].

FAQ 3: What is the fundamental difference between SMOTE/ADASYN and GANs for generating synthetic data? SMOTE and ADASYN are relatively simple, non-learned interpolation techniques. They create new data points by linearly combining existing minority class instances [21]. GANs, on the other hand, are deep learning models that learn the underlying probability distribution of the minority class data. Through an adversarial training process, they can generate highly realistic and novel synthetic data that can be more diverse than SMOTE-generated data [22].

FAQ 4: When should I consider using GANs over SMOTE for my DTI dataset? Consider GANs when:

- You have a sufficiently large and complex dataset, and you need to generate highly diverse and novel molecular structures [22].

- Advanced SMOTE variants (e.g., Borderline-SMOTE, SVM-SMOTE) still do not yield satisfactory performance.

- You have the computational resources and expertise to train a complex deep-learning model. For many standard applications, starting with SMOTE or one of its variants is recommended due to its simplicity and computational efficiency.

FAQ 5: After applying SMOTE, my model's performance on the independent test set did not improve. Why? This can occur due to several reasons:

- Overfitting on Synthetic Data: The model may have learned the specific patterns of the synthetically generated points, which do not generalize well to real-world data.

- Introduction of Noisy Samples: If synthetic instances are created in regions of the feature space that overlap with the majority class, they become "noisy" examples that confuse the classifier [21].

- Improper Application of SMOTE: SMOTE should only be applied to the training data after splitting. If you apply it to the entire dataset before splitting, you will cause data leakage, as information from the test set influences the training process, leading to over-optimistic and invalid performance estimates [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The synthetic data generated by SMOTE is causing overfitting.

Explanation: SMOTE generates synthetic data by linear interpolation between neighboring minority class instances. This can lead to the creation of overly simplistic and redundant samples if the minority class has a complex distribution or contains noise, causing the model to learn a non-generalizable decision boundary.

Solution Steps:

- Use Advanced SMOTE Variants: Switch from vanilla SMOTE to more sophisticated versions designed to mitigate this issue.

- Borderline-SMOTE: This method only generates synthetic samples for minority instances that are misclassified by a k-Nearest Neighbors classifier (the "danger" instances). This focuses the data generation on the class boundary where it is most needed [21].

- SVM-SMOTE: This uses a Support Vector Machine (SVM) to identify support vectors (which often lie near the decision boundary) and generates synthetic data near these points [21].

- KMeans-SMOTE: This first clusters the minority class, then allocates more synthetic samples to sparse clusters, ensuring a more balanced distribution across the minority class [21].

- Combine Sampling with Cleaning: Use hybrid methods like SMOTE-Tomek. The Tomek Links method identifies and removes overlapping examples from both classes after SMOTE application, which can help in refining the class boundary and reducing noise [4].

- Validate Rigorously: Use nested cross-validation to more robustly evaluate the model's performance and tune hyperparameters, ensuring that the reported performance is not biased by overfitting.

Problem: My dataset includes both numerical and categorical features (e.g., molecular fingerprints), and SMOTE fails.

Explanation: Standard SMOTE operates in continuous feature space and uses Euclidean distance, making it incompatible with categorical data. Applying it directly to such mixed data will produce meaningless interpolated values for categorical features.

Solution Steps:

- Use SMOTE-NC (SMOTE-Nominal Continuous): This is an extension of SMOTE specifically designed to handle datasets with both numerical and categorical features. For a mixed-type feature vector, SMOTE-NC calculates the median of the standard deviations of all numerical features. It then uses this value in the distance calculation to find k-nearest neighbors. When generating a new sample, it copies the most frequent category among the k-nearest neighbors for the categorical columns [21].

- Alternative: Feature Engineering: Consider transforming your categorical features into a numerical representation that captures their relationships, if possible, though this is often non-trivial in chemical informatics.

Problem: The generative AI model (e.g., GAN) produces invalid molecular structures.

Explanation: GANs, particularly those generating molecular structures as SMILES strings or graphs, can sometimes output sequences that do not correspond to valid, syntactically correct, or chemically stable molecules.

Solution Steps:

- Use Domain-Specific Generative Models: Employ generative models specifically designed for molecular generation, such as REINVENT4. These models incorporate chemical knowledge and rules into the generation process, leading to a much higher rate of valid molecules. For instance, one study showed that a character-level RNN produced only 3% valid molecules, while REINVENT4 achieved 100% validity [22].

- Implement Validity Checks: Integrate a post-processing step that filters out invalid SMILES strings using a chemical validation toolkit like RDKit.

- Reinforcement Learning (RL) Fine-tuning: Fine-tune the generative model using RL with a reward function that penalizes invalid structures and rewards desirable chemical properties [22].

Comparative Analysis of Synthetic Data Strategies

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of SMOTE, ADASYN, and GANs.

Table 1: Comparison of Data-Level Strategies for Handling Class Imbalance

| Feature | SMOTE | ADASYN | GANs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Interpolates between random minority class instances [21]. | Interpolates between instances, weighted by learning difficulty; focuses on "hard-to-learn" examples [20]. | Learns data distribution via adversarial training between generator and discriminator networks [22]. |

| Data Generation | Linear interpolation in feature space. | Linear interpolation, density-biased. | Non-linear, can model complex distributions. |

| Diversity of Data | Limited to convex combinations of existing data. | Limited to convex combinations, but more focused. | High potential for creating novel, diverse samples. |

| Computational Cost | Low [4]. | Low to Moderate. | Very High [22]. |

| Ease of Implementation | High (e.g., via imbalanced-learn). |

High (e.g., via imbalanced-learn). |

Low (requires deep learning expertise). |

| Handling of Within-Class Imbalance | No (treats all minority instances equally). | Yes (adaptively generates more data for harder examples). | Yes (can learn the full distribution, including rare sub-concepts). |

| Key Advantage | Simple, effective, and fast. Good starting point. | Can improve recall by focusing on difficult regions. | Can generate highly realistic and novel data. |

| Key Challenge | Can generate noisy samples in overlapping regions; ignores within-class imbalance [21]. | Can over-emphasize outliers. | Training instability; mode collapse; high resource demands [22]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance in Drug Discovery Contexts

| Method / Scenario | Key Performance Metric | Result | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative AI (REINVENT4) | Model Specificity on HTS Test Set (1:76 imbalance) | Improved from 0.08 to 0.56 [22] | Screening a large compound library; critical for reducing false positives. |

| Generative AI (REINVENT4) | ROC AUC on Scaffold Split Test | Improved from 0.72 to 0.81 [22] | Tests generalizability to novel chemical scaffolds. |

| Generative AI (REINVENT4) | G-Mean | Improved from 0.60 to 0.76 [22] | Geometric mean of sensitivity & specificity; good for imbalanced data. |

| FastUS (Undersampling) | AUC / F1-Score | Outperformed 4 state-of-the-art methods [8] | Highlights that sophisticated sampling can outperform simple random sampling. |

| Weighted Loss Function | Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | Can achieve high MCC, but less consistent than oversampling [23] | An algorithm-level strategy for comparison; performance can be volatile. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing SMOTE and its Variants for a DTI Dataset

This protocol outlines the steps to apply SMOTE and its advanced variants using the imbalanced-learn library in Python.

Objective: To balance an imbalanced DTI training set to improve classifier performance on the minority (interacting) class.

Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit):

- Software: Python with

imbalanced-learn(imported asimblearn),scikit-learn,pandas,numpy. - Data: A feature matrix (X) and label vector (y) for your DTI problem, split into training and testing sets.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing and Splitting:

- Perform necessary cleaning, normalization, and feature scaling on your dataset.

- Split the data into training and testing sets using stratified splitting (

train_test_splitwithstratify=y) to maintain the original imbalance ratio in the splits [19].

- Apply SMOTE (or variant) to Training Set Only:

- Crucially, apply the sampling technique only to the training data to prevent data leakage [4].

- For Standard SMOTE:

- For Borderline-SMOTE:

- Train Model and Evaluate:

- Train your chosen classifier (e.g., LightGBM, Random Forest) on the resampled training data (

X_train_resampled,y_train_resampled). - Make predictions on the original, unmodified test set (

X_test,y_test). - Evaluate performance using metrics like Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and AUC-PR.

- Train your chosen classifier (e.g., LightGBM, Random Forest) on the resampled training data (

The following diagram illustrates this workflow:

Workflow for Applying SMOTE

Protocol 2: A Generative AI Framework for Non-Active Compound Generation

This protocol is based on a published study that used generative models to address the scarcity of non-active compounds for GPCR targets [22].

Objective: To generate novel, valid non-active compounds for a specific protein target (e.g., M1 muscarinic receptor) to enhance the training set for a classification model.

Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit):

- Data Sources: Public bioactivity databases (ChEMBL, BindingDB, PubChem).

- Generative Models: CharRNN or more advanced models like REINVENT4.

- Validation Tools: Chemical validation toolkits (e.g., RDKit), clustering algorithms (e.g., for diversity analysis).

- Computing: Access to GPU resources for efficient model training.

Procedure:

- Data Curation:

- Collect known active and non-active compounds for your target from databases. Apply a clear activity threshold (e.g., ≤1μM for active, ≥10μM for non-active).

- Perform Tanimoto similarity analysis to ensure a clear structural distinction between active and non-active sets.

- Model Selection and Training:

- Select a generative model. The study found REINVENT4 vastly superior to CharRNN, producing 100% valid molecules compared to only 3% [22].

- Train the selected model on the curated set of known non-active compounds to learn their structural and physicochemical patterns.

- Generation and Validation:

- Use the trained model to generate a large number of candidate non-active molecules.

- Filter the generated molecules for chemical validity and desired properties.

- Perform clustering analysis (e.g., using Taylor-Butina clustering) to assess the structural diversity of the generated set compared to the original data.

- Model Enhancement:

- Incorporate the validated, generated non-active compounds into the training data for a DTI classifier.

- Re-train the classifier and evaluate its performance on a challenging external test set, such as a scaffold-split set or a high-throughput screening (HTS) dataset with a high imbalance ratio.

The following diagram illustrates this high-level framework:

Generative AI for Data Augmentation

Foundations: Tackling Class Imbalance in Drug Discovery

In computational drug discovery, the datasets used for training classification models, such as those predicting whether a compound is active against a biological target, are typically highly unbalanced. The number of inactive compounds vastly outnumbers the number of active substances. This class imbalance causes standard machine learning models to be biased toward the majority (inactive) class, leading to poor predictive performance for the critical minority (active) class you are often most interested in identifying [23].

Algorithm-level approaches directly modify machine learning algorithms to mitigate this bias. Unlike data-level methods (e.g., oversampling) that alter the training dataset, algorithm-level techniques preserve the original data distribution, maintaining its full informational content [24]. The two primary algorithm-level strategies are:

- Cost-Sensitive Learning (CSL): This strategy introduces distinct misclassification costs for each class during training. The underlying assumption is that a higher misclassification cost is assigned to samples from the minority class, forcing the model to pay more attention to them. The objective is to minimize the overall high-cost errors [24] [25].

- Ensemble Methods: These methods combine multiple base models to create a more robust and accurate classifier. When tailored for class imbalance, they often integrate principles from CSL or resampling techniques to strengthen the collective prediction for the minority class [24].

Troubleshooting Cost-Sensitive Learning

FAQ: What is the core principle behind Cost-Sensitive Learning? CSL operates on the principle that not all prediction errors are equal. Misclassifying a rare, active compound (a false negative) is more detrimental to a drug discovery campaign than misclassifying a common, inactive one (a false positive). CSL algorithms formalize this by assigning a higher penalty or cost to errors made on the minority class. The model's training objective then becomes the minimization of total cost, rather than total errors, which improves its ability to identify the critical class [24].

FAQ: I've implemented a cost-sensitive model, but I'm getting too many false positives. How can I refine the cost matrix? An excess of false positives indicates that the cost assigned to the minority class might be disproportionately high, causing the model to become overly sensitive. The following troubleshooting guide addresses this and other common issues.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High False Positive Rate | Cost for minority class is set too high, making the model overly sensitive. | Systematically reduce the cost assigned to the minority class and re-evaluate performance using metrics like Precision and F1-score [25]. |

| Poor Generalization (Overfitting) | The cost matrix is over-optimized for the training set, learning its noise. | Validate your cost matrix on a separate validation set or using cross-validation. Consider using a robust method like a Random Undersampling Ensemble (RUE) to feedback a more generalizable error rate for cost assignment [25]. |

| Persistent High False Negatives | Assigned costs for the minority class are still too low to overcome the data imbalance. | Increase the cost weight for the minority class. Explore advanced "personalized cost assignment" strategies that assign different costs to different instances based on their location information rather than a constant cost for the entire class [25]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Cost-Sensitive Random Forest A common and effective way to apply CSL is using a cost-sensitive variant of the Random Forest algorithm. Below is a detailed methodology based on common practices in the field [12].

- Data Preparation: Start with your pre-processed drug-target interaction dataset (e.g., molecular fingerprints and target features). Split the data into training, validation, and test sets, ensuring the imbalance ratio is consistent across splits.

- Baseline Model Training: Train a standard Random Forest classifier on the training set without any cost adjustments. This provides a performance baseline.

- Assign Class Weights: Implement CSL by calculating class weights. A standard method is to set the class weight to be inversely proportional to the class frequencies. For example, using the "balanced" mode in libraries like scikit-learn, where the weight for a class is given by:

weight = total_samples / (n_classes * count_of_class_samples). - Train Cost-Sensitive Model: Train a new Random Forest model on the same training set, but this time incorporate the calculated class weights. This tells the algorithm to penalize misclassifications of the rare class more heavily.

- Evaluation and Comparison: Evaluate both the baseline and cost-sensitive models on the validation set. Use metrics robust to imbalance, such as Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), F1-score, and Balanced Accuracy. The cost-sensitive model should show a marked improvement, particularly in recall for the minority class and MCC [23] [12].

Troubleshooting Ensemble Methods: Rotation Forest

FAQ: Why is the Rotation Forest algorithm particularly effective for imbalanced drug data? Rotation Forest is an ensemble method that aims to build accurate and diverse classifiers. It works by randomly splitting the feature set into subsets, performing Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on each subset, and then reconstructing a full feature space for training a base classifier (like a decision tree). This process enhances both the accuracy and diversity of the individual classifiers in the ensemble. For imbalanced data, this diversity is crucial as it allows the ensemble to capture complex patterns associated with the minority class that a single model might miss [26]. Its performance can be further boosted by hyperparameter optimization and feature selection [26].

FAQ: My Rotation Forest model is computationally expensive. How can I optimize it? The process of multiple PCA transformations is inherently more computationally intensive than simpler ensembles like Random Forest. To optimize it:

- Feature Selection: Prior to training, apply feature selection techniques (like Sequential Forward Selection or Exhaustive Feature Selection) to reduce the dimensionality of the data. This directly reduces the PCA computation load [26].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Use efficient hyperparameter optimization frameworks like Optuna with the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) sampler. This intelligently explores the hyperparameter space (e.g., number of subsets, base estimators) to find a high-performance configuration with fewer trials [26].

Experimental Protocol: Building an Optimized Rotation Forest Model This protocol outlines the steps for creating a high-performance Rotation Forest model, incorporating hyperparameter tuning and feature selection as described in recent research [26].

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize or standardize your dataset (e.g., the Breast Cancer Coimbra dataset with clinical biomarkers) to ensure that the PCA step in Rotation Forest is not dominated by features on different scales.

- Hyperparameter Optimization with Optuna:

- Define an objective function that trains a Rotation Forest model with a given set of hyperparameters (e.g., number of estimator subsets, PCA components).

- Use the F1-score on the training data (or via cross-validation) as the optimization metric.

- Run the Optuna optimizer with the TPE sampler for a set number of trials (e.g., 50) to find the best hyperparameters.

- Wrapper-Based Feature Selection: Using the optimized hyperparameters from Optuna, apply wrapper methods like Sequential Forward Selection (SFS) or Sequential Backward Selection (SBS) to identify the most relevant feature subset for the classification task.

- Ensemble Voting (Optional): For maximum performance, create an ensemble of multiple Rotation Forest models, each trained on the best feature subsets found in the previous step. Combine their predictions using a hard voting strategy (majority vote) which has been shown to achieve higher accuracy than soft voting in some bioinformatics applications [26].

- Model Evaluation: Rigorously evaluate the final model on a held-out test set. Report key metrics for imbalanced datasets: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score.

Performance Comparison & Decision Guide

The table below summarizes quantitative results from recent studies to help you choose the right algorithm-level approach.

| Algorithm / Strategy | Dataset / Context | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) with Weighted Loss Function | Molecular graph datasets (e.g., from MoleculeNet) | Achieved high Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), though with some variability. Weighted loss helps the model prioritize the minority class during training [23]. | [23] |

| Random Forest (RF) with Random Undersampling (RUS) | PubChem Bioassays (HIV, Malaria) with IR ~1:100 | RUS configuration (1:10 IR) significantly enhanced ROC-AUC, Balanced Accuracy, MCC, Recall, and F1-score compared to the model trained on the original data [12]. | [12] |

| Rotation Forest with Feature Selection & Hard Voting | Breast Cancer Coimbra (BCC) Dataset | An ensemble with a hard voting strategy achieved an accuracy of 85.71%, F1-score of 83.87%, and precision of 92.85% [26]. | [26] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key computational "reagents" and tools used in the development of the models discussed in this guide.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Optuna | Hyperparameter Optimization Framework | An open-source library that automates the search for the best model parameters using efficient algorithms like the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE), crucial for tuning complex models like Rotation Forest [26]. |

| BindingDB | Database of Drug-Target Interaction Data | A public database containing over 2.8 million experimentally determined small molecule-protein interactions (e.g., IC50 values), used as a primary source for training drug-target affinity prediction models [27]. |

| PubChem Fingerprints | Molecular Representation | An 881-dimensional binary vector denoting the presence or absence of specific chemical substructures, used as a feature representation for machine learning models in drug discovery [27]. |

| SMILES | Molecular Representation | A line notation (e.g., CC(=O)OC1=CC=CC=C1C(=O)O for aspirin) for encoding the structure of chemical molecules as text strings, which can be fed into deep learning models [27] [23]. |

| ChEMBL | Drug Database for Validation | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules, often used for external validation of trained models to assess their generalizability [27]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental advantage of using GNNs for drug-target data over traditional neural networks?

GNNs can directly operate on graph-structured data, which is a natural representation for many biological systems. Unlike traditional neural networks that require fixed-sized, grid-like inputs (e.g., images or sequences), GNNs use message-passing layers that allow nodes (e.g., atoms or proteins) to update their representations by aggregating information from their neighbors (e.g., chemical bonds or interaction networks) [28] [29]. This capability is essential for handling the variable-sized and complex relational data inherent in molecules and protein interactions, which traditional architectures struggle to process effectively.

FAQ 2: My dataset has major class imbalance—many more non-interacting drug-target pairs than interacting ones. Which strategy should I try first?

For severe class imbalance, a combination of data-level and algorithm-level techniques is recommended. Research indicates that exploring multiple techniques is crucial, as no single method outperforms all others universally [30]. Promising approaches include:

- Data-level: Using

SMOTETomek, which combines over-sampling (SMOTE) and under-sampling (Tomek links) to generate a balanced dataset [30]. - Algorithm-level: Applying

class-weightingwithin machine learning classifiers like Random Forest or Support Vector Machine to penalize misclassifications of the minority class more heavily [30]. - Threshold optimization: Techniques like

GHOSTor optimizing based on the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) can adjust the default prediction threshold to better account for imbalance [30].

FAQ 3: The MCSDTI framework splits targets into TWLNI and TWSNI. How is this split performed, and what classifier does it use?

In the MCSDTI framework, targets are divided into two groups based on the number of known interactions they have [17]:

- Targets with Larger Numbers of Interactions (TWLNI)

- Targets with Smaller Numbers of Interactions (TWSNI)

The specific threshold for this split is determined by the dataset's characteristics. The framework then employs different classification strategies for each group. For TWLNI, which have enough positive samples, a custom classifier is designed that uses only the target's own positive samples to avoid the negative impact of neighbors' data. For TWSNI, which have very few positive samples, a classifier that leverages positive samples from neighboring targets is used to improve prediction [17]. The original study used a novel classifier and evaluator for TWLNI and identified a strong pre-existing classifier for TWSNI, demonstrating improved AUC scores on multiple datasets [17].

FAQ 4: How can I implement a basic GNN for a molecular property prediction task?

A basic GNN for molecular property prediction (a graph-level task) can be built using the following components from a standard GNN architecture [28]:

- Input: Represent the molecule as a graph, with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges.

- Permutation Equivariant Layers (Message Passing): Use several message-passing layers (e.g., Graph Convolutional Network layers) where each atom updates its feature vector based on its own features and the features of its bonded neighbors [28].

- Global Pooling (Readout) Layer: After the message-passing layers, aggregate the updated feature vectors of all atoms into a single, fixed-size graph-level representation. This is typically done using a permutation-invariant function like element-wise

sum,mean, ormaximum[28]. - Output Layer: Feed the graph-level representation into a final fully-connected layer to produce the prediction (e.g., a toxicity score or binding affinity).

The following workflow diagram illustrates this process:

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Performance is Skewed by Class Imbalance

Symptoms

- High overall accuracy but very low recall or precision for the minority class (interacting pairs).

- The model fails to learn meaningful patterns for the positive class and defaults to predicting "no interaction" most of the time.

Diagnostic Steps

- Calculate Class Ratios: Determine the ratio of positive to negative samples in your dataset. A highly skewed ratio (e.g., 1:100) is a clear indicator [17] [30].

- Check Performance Metrics: Rely on metrics beyond accuracy. Use F1-score, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), Balanced Accuracy, and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) to get a true picture of model performance on the imbalanced data [30].

Solutions

The table below summarizes techniques validated on drug-discovery datasets for handling class imbalance.

| Technique | Type | Brief Description | Reported Performance Improvement (F1 / MCC / Bal. Acc.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMOTETomek [30] | Data-level | Hybrid resampling: creates synthetic minority samples & cleans overlapping majority samples. | Up to 375% / 33.33% / 450% (with RF/SVM) |

| Class-Weighting [30] | Algorithm-level | Adjusts model loss function to assign higher cost to minority class misclassifications. | Significant improvement over unbalanced baseline [30] |

| Threshold Optimization (GHOST) [30] | Algorithm-level | Finds an optimal prediction threshold instead of using the default 0.5. | Improves threshold-based metrics, no effect on AUC/AUPR [30] |

| AutoML Internal Balancing [30] | Hybrid | Leverages built-in class-balancing features in AutoML tools like H2O and AutoGluon. | Up to 383.33% / 37.25% / 533.33% |

Recommended Protocol:

- Start by applying class-weighting in your chosen model (e.g.,

class_weight='balanced'in scikit-learn), as it is straightforward and requires no data modification [30]. - If performance remains poor, use SMOTETomek to balance your training data. Be aware that synthetic data generation can sometimes introduce noise [30].

- Finally, apply threshold optimization on your model's predicted probabilities to fine-tune the trade-off between precision and recall for your specific application [30].

- Consider using AutoML tools (e.g., H2O AutoML) that have internal mechanisms to handle imbalance, as they have been shown to perform comparably to traditional ML methods in this context [30].

Problem: GNN Fails to Distinguish Between Different Molecular Structures

Symptoms

- The model predicts similar properties or interactions for two different molecules.

- Low test accuracy, especially on molecules with similar atoms but different bond structures.

Diagnostic Steps

- Check Model Expressivity: The Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) test sets a theoretical limit on the expressive power of GNNs. A basic GNN may be unable to distinguish certain graph structures that are different but isomorphic from a WL perspective [28].

- Visualize Node Receptive Fields: The receptive field of a node in a GNN is determined by the number of message-passing layers. With too few layers, nodes only have local information and cannot capture important global graph topology [28].

Solutions

- Increase Model Depth: Add more message-passing layers. Each layer allows information to propagate one "hop" further. Stacking

nlayers gives each node information about itsn-hop neighborhood [28]. - Use More Powerful GNN Architectures: Move beyond basic Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs). Implement architectures with higher expressive power:

- Graph Attention Networks (GATs): Use attention mechanisms to assign different levels of importance to a node's neighbors, improving the model's ability to focus on relevant structural features [28].

- Gated Graph Sequence Neural Networks (GGS-NN): Incorporate gated mechanisms, similar to LSTMs, to help preserve information over long distances within the graph [28].

- Incorporate Higher-Order Information: Design GNNs that operate on higher-dimensional graph constructs (e.g., simplicial complexes) to capture more complex topological features beyond pairwise interactions [28].

The following diagram contrasts the information flow in a shallow versus a deeper GNN:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key software tools and libraries essential for conducting research in GNNs and drug-target interaction prediction.

| Item Name | Type | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| PyTorch Geometric (PyG) [28] | Library | A powerful library built upon PyTorch for deep learning on graphs, providing numerous GNN layers and benchmark datasets. |

| Deep Graph Library (DGL) [28] | Library | A framework-agnostic platform that simplifies the implementation of graph neural networks and supports multiple backends like PyTorch and TensorFlow. |

| TensorFlow GNN [28] | Library | A scalable library for building GNN models within the TensorFlow ecosystem, designed for heterogeneous graphs. |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) [31] | Dataset/Platform | Provides access to curated datasets, AI-ready benchmarks, and learning tasks across the entire drug discovery pipeline. |

| DrugBank [17] [32] | Database | A comprehensive bioinformatics and cheminformatics resource containing detailed drug and drug-target information. |

| SMOTETomek [30] | Algorithm | A resampling technique to address class imbalance, available in libraries like imbalanced-learn (scikit-learn-contrib). |

| H2O AutoML / AutoGluon-Tabular [30] | Tool/AutoML | Automated machine learning tools that can be effective for tabular data tasks, including built-in handling of class imbalance. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is class imbalance a particularly critical issue in Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) prediction?

Class imbalance is a fundamental challenge in DTI prediction because the number of known, positive drug-target interactions is vastly outnumbered by the number of non-interacting or unknown pairs [8]. This creates a significant between-class imbalance, where a naive model might achieve high accuracy by simply always predicting "no interaction," thereby failing to identify therapeutically valuable interactions [2] [8]. Furthermore, a within-class imbalance often exists, where some types of interactions (e.g., binding to a specific protein family) are less represented than others, leading to poor prediction performance for these specific subsets [8].

Q2: My model has high accuracy but is failing to predict true interactions. What is the first thing I should check?

Before applying complex resampling techniques, your first step should be to re-evaluate your metrics and adjust the decision threshold [33]. Accuracy is misleading for imbalanced datasets. Instead, use metrics like ROC-AUC (threshold-independent) and precision-recall curves. For threshold-dependent metrics like precision and recall, avoid the default 0.5 probability threshold. Use the training set to tune this threshold to a value that better balances the trade-off between identifying true interactions and minimizing false positives [33].

Q3: When should I use resampling techniques like SMOTE versus trying a cost-sensitive learning algorithm?

The choice depends on your model and goals. Recent evidence suggests that for strong classifiers like XGBoost and CatBoost, tuning the probability threshold or using cost-sensitive learning is often as effective as, or better than, applying resampling [33]. However, if you are using weaker learners (e.g., logistic regression, standard decision trees) or models that do not output probabilities, then random oversampling or SMOTE can provide a significant performance boost [33]. Random oversampling is a simpler and often equally effective alternative to SMOTE [33].

Q4: What are the key feature representations for drugs and targets in a DTI classification pipeline?

Effective feature engineering is crucial. Common representations include:

- Drugs: Molecular fingerprints (e.g., MACCS keys, ECFP), SMILES strings, molecular descriptors, and graph-based encodings [34] [2].

- Targets: Amino acid sequences, dipeptide compositions, pseudo-amino acid composition, and features derived from pre-trained protein language models (e.g., ProtBERT) [34] [2] [8]. The choice of representation should enable the model to capture complex structural and functional properties.

Q5: How can I handle the computational cost of advanced resampling techniques like GANs on large-scale DTI datasets?

While Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have shown promise for generating synthetic minority-class samples, they are computationally intensive [2]. For large-scale initial experiments, consider starting with simpler and faster methods like random oversampling or the EasyEnsemble algorithm, which can be more scalable [33]. If using GANs, ensure you have access to sufficient computational resources (e.g., GPUs) and validate that the performance gain justifies the additional cost and complexity [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Recall for the Minority Class (Interacting Pairs)

Symptoms: The model shows a strong bias towards the majority class (non-interacting pairs). It has high specificity but fails to identify a large portion of the true drug-target interactions (high false negative rate).

Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of severe between-class imbalance, where the model has not learned sufficient patterns from the positive interaction class [8].

Solutions:

- Resampling the Training Set: Apply one of the following techniques only to the training data:

- Random Oversampling: Randomly duplicate examples from the minority class (interacting pairs) until the classes are balanced. This is a simple and effective baseline [33] [4].

- Synthetic Oversampling (SMOTE): Generates new synthetic examples for the minority class by interpolating between existing instances [33] [4].

- Undersampling: Randomly remove examples from the majority class. Use with caution as it can discard potentially useful information [33].

- Algorithmic Approach: Use ensemble methods designed for imbalance, such as Balanced Random Forest or EasyEnsemble, which internally balance the class distribution [33].

- Threshold Tuning: As a primary or complementary step, adjust the prediction probability threshold to favor the minority class, which can significantly increase recall without resampling [33].

Problem 2: Model Performance is Inconsistent Across Different Target Types

Symptoms: The model predicts interactions for certain protein families (e.g., kinases) well but performs poorly for others (e.g., GPCRs), even though all are present in the training data.

Diagnosis: This indicates within-class imbalance, where the "interaction" class is composed of several sub-concepts (interaction types), and some are less represented than others [8].

Solutions:

- Cluster and Oversample: Within the positive class, use clustering algorithms (e.g., k-means) to identify homogeneous groups of interactions. Then, apply oversampling (like SMOTE) specifically to the under-represented clusters to enhance their presence before training [8].

- Feature Enhancement: Ensure your target protein feature representation is rich enough to distinguish between different protein families. Consider using advanced embeddings from protein language models (e.g., ProtBERT) that capture deeper semantic and functional information [34] [16].

Problem 3: Good Training Performance but Poor Test Performance After Resampling

Symptoms: After applying oversampling, the model achieves near-perfect training scores (accuracy, F1-score), but performance drops significantly on the held-out test set.

Diagnosis: This is often a sign of overfitting caused by the resampling process. Synthetic oversampling techniques like SMOTE can lead to over-generalization if not properly validated [33].

Solutions:

- Apply Cross-Validation Correctly: Ensure that the resampling is applied after splitting the data into training and validation folds within your cross-validation loop. Resampling before splitting will leak information from the validation set into the training process, giving optimistically biased results.

- Use Simpler Resampling: Try random oversampling instead of SMOTE, as it can be less prone to creating overfitted decision boundaries in some cases [33].

- Regularize Your Model: Increase the regularization parameters in your classifier to make it less sensitive to the specific synthetic samples.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Detailed Methodology: A Hybrid GAN-RF Framework for DTI Prediction

The following protocol is based on a state-of-the-art approach that combines feature engineering, GAN-based imbalance handling, and a Random Forest classifier [2].

1. Feature Engineering Phase:

- Drug Feature Extraction: Encode each drug molecule using the MACCS keys fingerprint, which is a set of 166 structural keys indicating the presence or absence of specific chemical substructures [2].

- Target Feature Extraction: Represent each target protein using its amino acid composition (AAC) and dipeptide composition (DPC). AAC is the fraction of each of the 20 amino acids in the sequence. DPC is the fraction of each of the 400 possible pairs of adjacent amino acids, which captures local sequence information [2].

- Data Integration: Concatenate the drug fingerprint vector and the target composition vector to create a unified feature representation for each drug-target pair.

2. Data Balancing Phase:

- Data Preparation: Separate the labeled training data into majority (non-interacting) and minority (interacting) classes.

- Synthetic Sample Generation: Train a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) on the feature vectors of the minority class. The generator learns the underlying data distribution of the real interactions and produces new, synthetic feature vectors that are statistically similar [2].

- Balanced Dataset Creation: Combine the synthetically generated interaction samples with the original training data (both minority and majority classes) to create a balanced dataset.

3. Model Training & Evaluation:

- Classifier Training: Train a Random Forest Classifier on the balanced dataset. The RF is robust to high-dimensional data and can capture non-linear relationships [2].

- Performance Validation: Evaluate the model on a held-out test set that was not used in the balancing process. Use comprehensive metrics as shown in the table below.

Quantitative Performance Data [2]: The table below summarizes the performance of the GAN+RFC model on different BindingDB datasets, demonstrating its effectiveness.

| Dataset | Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity (Recall) | Specificity | F1-Score | ROC-AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BindingDB-Kd | 97.46% | 97.49% | 97.46% | 98.82% | 97.46% | 99.42% |

| BindingDB-Ki | 91.69% | 91.74% | 91.69% | 93.40% | 91.69% | 97.32% |

| BindingDB-IC50 | 95.40% | 95.41% | 95.40% | 96.42% | 95.39% | 98.97% |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end pipeline integrating feature engineering and imbalance handling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational tools and data resources essential for building an end-to-end DTI pipeline.

| Resource Name | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| MACCS Keys / ECFP | Molecular Fingerprint | Encodes the chemical structure of a drug molecule into a fixed-length bit vector, facilitating similarity search and machine learning [34] [2]. |

| ProtBERT / ESM | Protein Language Model | Provides deep contextualized vector representations (embeddings) of protein sequences, capturing structural and functional semantics beyond simple composition [34] [16]. |

| Imbalanced-Learn | Python Library | Provides a wide array of resampling techniques (e.g., RandomOverSampler, SMOTE, EasyEnsemble) to handle class imbalance in datasets [33] [4]. |

| Featuretools | Automated Feature Engineering | Automates the generation of features from relational and temporal datasets using Deep Feature Synthesis (DFS), which can be applied to multi-table chemical and biological data [35]. |