Optimizing NGS Workflows for Chemogenomics: A Strategic Guide to Enhance Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) workflows specifically for chemogenomics applications.

Optimizing NGS Workflows for Chemogenomics: A Strategic Guide to Enhance Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) workflows specifically for chemogenomics applications. It covers foundational principles, from understanding the synergy between NGS and chemogenomics in identifying druggable targets, to advanced methodological applications that leverage automation and machine learning for drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction. The content delivers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing critical workflow stages, including sample-specific nucleic acid extraction and host depletion, and concludes with robust frameworks for the analytical and clinical validation of results. By integrating these elements, the guide aims to enhance the efficiency, accuracy, and translational impact of chemogenomics-driven research.

Laying the Groundwork: How NGS and Chemogenomics Converge in Modern Drug Discovery

NGS in Chemogenomics: Core Concepts

Question: What is the role of NGS in modern chemogenomic analysis?

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) accelerates chemogenomics by enabling unbiased, genome-wide profiling of how a cell's genetic makeup influences its response to chemical compounds. In practice, this involves using NGS to analyze complex pooled libraries of genetic mutants (e.g., yeast deletion strains) grown in the presence of drugs. This allows for the rapid identification of drug-target interactions and mechanisms of synergy between drug pairs on a massive scale, moving beyond targeted studies to discover novel biological pathways and combination therapies [1].

Question: What are the primary NGS workflows used in chemogenomics?

The foundational NGS workflow for chemogenomics mirrors standard genomic approaches but is tailored for specific assay outputs. The key steps are [2]:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Isolating high-quality genetic material from the pooled chemogenomic assay (e.g., extracting genomic DNA from a pooled pool of yeast deletion mutants after drug treatment).

- Library Preparation: Converting the extracted DNA into a sequenceable library by fragmenting, adding adapters, and amplifying the genetic barcodes that uniquely identify each strain in the pool.

- Sequencing: Using high-throughput NGS platforms to sequence these barcodes.

- Data Analysis: Using bioinformatics tools to quantify the relative abundance of each barcode from the sequencer output. This abundance data reveals which genetic mutants are sensitive or resistant to the drug, indicating potential drug targets [1] [2].

Troubleshooting NGS in Chemogenomic Assays

Question: Our chemogenomic HIP-HOP assay shows flat coverage and high duplication rates after sequencing. What could be wrong?

This is a classic sign of issues during library preparation. The root cause often lies in the early steps of the workflow. The table below summarizes common problems and solutions [3].

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Common Root Causes & Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Input / Quality | Low library complexity, smear in electropherogram [3] | • Cause: Degraded genomic DNA or contaminants (phenol, salts) from extraction.• Fix: Re-purify input DNA; use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) instead of UV absorbance alone [3] [4]. |

| Fragmentation & Ligation | Unexpected fragment size; sharp ~70-90 bp peak (adapter dimers) [3] | • Cause: Over- or under-fragmentation; inefficient ligation due to poor enzyme activity or incorrect adapter-to-insert ratio.• Fix: Optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter concentration; ensure fresh ligase and buffer [3]. |

| Amplification / PCR | High duplicate rate; overamplification artifacts [3] | • Cause: Too many PCR cycles during library amplification.• Fix: Reduce the number of amplification cycles; use an efficient polymerase. It is better to repeat the amplification from leftover ligation product than to overamplify a weak product [3]. |

| Purification & Cleanup | Incomplete removal of adapter dimers; significant sample loss [3] | • Cause: Incorrect bead-to-sample ratio during clean-up steps.• Fix: Precisely follow manufacturer's ratios for magnetic beads; avoid over-drying the bead pellet [3]. |

Question: Our Ion S5 system fails a "Chip Check" before a run. What should we do?

A failed Chip Check can halt an experiment. Follow these steps [5]:

- Inspect the Chip: Open the chip clamp, remove the chip, and look for signs of physical damage or water outside the flow cell.

- Reseat or Replace: If the chip appears damaged, replace it with a new one. If it looks intact, try reseating it properly in the socket.

- Re-run Check: Close the clamp and repeat the Chip Check.

- Contact Support: If the chip continues to fail, the issue may be with the chip socket itself, and you should contact Technical Support [5].

Question: We observe low library yield after preparation. How can we improve this?

Low yield is often a result of suboptimal conditions in the early preparation stages. The primary causes and corrective actions are [3]:

- Verify Input Quality: Re-purify your input DNA to remove enzyme inhibitors like salts or phenol. Check sample purity via absorbance ratios (260/280 ~1.8, 260/230 >1.8) [3].

- Check Quantification: Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) for accurate template quantification instead of NanoDrop, which can overestimate concentration by counting contaminants [3] [4].

- Optimize Ligation: Ensure your ligase is active and that you are using the correct molar ratio of adapters to DNA insert. An excess of adapters can lead to adapter-dimer formation, while too few will reduce yield [3].

- Review Purification: Avoid overly aggressive size selection and ensure you are not losing sample during clean-up steps by using the correct bead-to-sample ratio [3].

Experimental Protocols & Reagent Solutions

Question: Can you provide a methodology for a chemogenomic drug synergy screen using NGS?

The following protocol, adapted from foundational research, outlines the key steps for a pairwise drug synergy screen analyzed by NGS [1].

- Strain Pool and Growth: Use a comprehensive pooled library of barcoded yeast deletion mutants (e.g., the homozygous or heterozygous deletion collections).

- Checkerboard Drug Screening: Screen drug pairs in a checkerboard matrix. Along each axis of a 96-well plate, add one drug at progressively higher doses (e.g., IC0, IC2, IC5, IC10, IC20, IC50). Grow the pooled mutant library in each drug combination condition [1].

- Growth Phenotyping: Measure optical density (OD600) at regular intervals over 24-48 hours to generate growth curves for each condition.

- Synergy Calculation (Bliss Model):

- Calculate the growth inhibition ratio for each well (Area under the curve for drug / Area for no-drug control).

- Calculate the Bliss independence expectation: (Drug Aratio × Drug Bratio).

- Calculate epsilon (ε): ε = Observed GrowthAB – Expected GrowthAB.

- A negative epsilon indicates a synergistic interaction, where the combination is more effective than predicted [1].

- Sample Prep for NGS: After determining synergistic conditions, harvest cells from the assay. Isolate genomic DNA from the pooled mutants. Prepare an NGS library where the amplified product is the unique molecular barcode from each yeast deletion strain [1].

- Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence the barcodes and use bioinformatics to quantify the relative fitness of each strain under the synergistic drug condition compared to a control. Identify "combination-specific sensitive strains" that reveal the mechanism of synergy [1].

Question: What are the essential research reagent solutions for these experiments?

Key reagents are critical for success, especially those that enhance workflow robustness. The following table details several essential components [1] [6].

| Research Reagent | Function in Chemogenomic NGS Workflow |

|---|---|

| Barcoded Deletion Mutant Collection | A pooled library of genetic mutants (e.g., yeast deletion strains), each with a unique DNA barcode. This is the core reagent for genome-wide HIP-HOP chemogenomic profiling [1]. |

| Glycerol-Free, Lyophilized NGS Enzymes | Enzymes for end-repair, A-tailing, and ligation that are stable at room temperature. They eliminate the need for cold chain shipping and storage, reduce costs, and are ideal for miniaturized or automated workflows [6]. |

| Optimized Reaction Buffers | Specialized buffers that combine multiple enzymatic steps (e.g., end repair and A-tailing in a single step), streamlining the library preparation process and reducing hands-on time [6]. |

| High-Sensitivity DNA Assay Kits | Fluorometric-based quantification kits (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) for accurate measurement of low-abundance input DNA and final libraries, preventing over- or under-loading in sequencing reactions [3] [4]. |

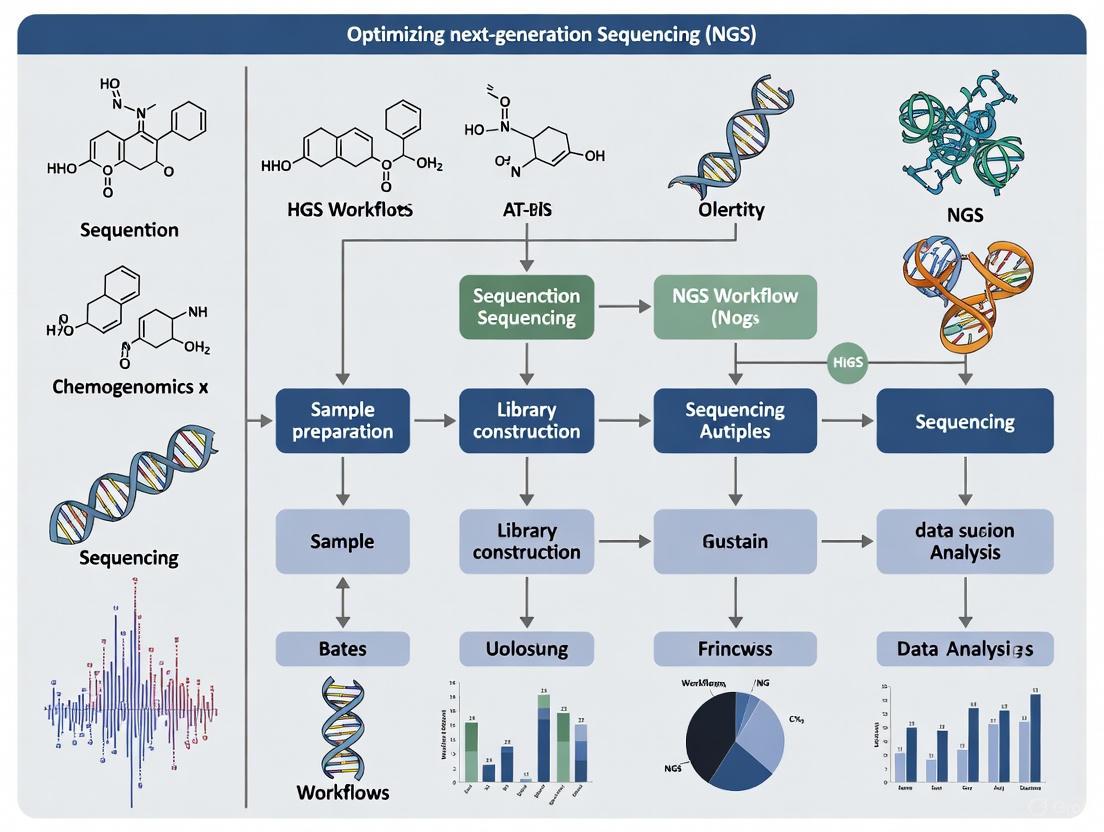

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of a chemogenomic NGS experiment, from assay setup to data interpretation.

Diagram Title: Chemogenomic NGS Workflow for Drug Synergy

This integrated troubleshooting guide and FAQ provides a foundation for optimizing your NGS workflows, ensuring that technical challenges do not hinder the discovery of powerful synergistic drug interactions in your chemogenomic research.

Foundational NGS Technologies for Chemogenomics

What is the role of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in modern chemogenomics research?

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is a foundational DNA analysis technology that reads millions of genetic fragments simultaneously, making it thousands of times faster and cheaper than traditional methods [7]. This revolutionary technology has transformed chemogenomics research by enabling comprehensive analysis of how chemical compounds interact with biological systems.

Key Capabilities of NGS in Chemogenomics:

- Speed: Sequences an entire human genome in hours instead of years [7]

- Cost: Reduced sequencing costs from billions to under $1,000 per genome [7]

- Scale: Processes millions of DNA fragments in parallel [7]

- Applications: Used in cancer research, rare disease diagnosis, drug discovery, and population studies [7] [8]

How do different NGS generations compare for chemogenomics applications?

Table 1: Comparison of Sequencing Technology Generations

| Feature | First-Generation (Sanger) | Second-Generation (NGS) | Third-Generation (Long-Read) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed | Reads one DNA fragment at a time (slow) | Millions to billions of fragments simultaneously (fast) | Long reads in real-time [7] |

| Cost | High, billions for a whole human genome | Low, under $1,000 for a whole human genome | Higher cost compared to short-read platforms [9] |

| Throughput | Low, suitable for single genes or small regions | Extremely high, suitable for entire genomes or populations | High for complex genomic regions [7] |

| Read Length | Long (500-1000 base pairs) | Short (50-600 base pairs, typically) | Very long (10,000-30,000 base pairs average) [9] |

| Primary Chemogenomics Use | Target validation, confirming specific variants | Whole-genome sequencing, transcriptome analysis, target identification | Solving complex genomic puzzles, structural variations [7] |

Troubleshooting NGS Workflows for Chemogenomics

What are the most common NGS library preparation failures and how can they be resolved?

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common NGS Library Preparation Issues

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Common Root Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Input / Quality | Low starting yield; smear in electropherogram; low library complexity [3] | Degraded DNA/RNA; sample contaminants (phenol, salts); inaccurate quantification [3] | Re-purify input sample; use fluorometric methods (Qubit) rather than UV for template quantification; ensure proper storage conditions [3] |

| Fragmentation & Ligation | Unexpected fragment size; inefficient ligation; adapter-dimer peaks [3] | Over-shearing or under-shearing; improper buffer conditions; suboptimal adapter-to-insert ratio [3] | Optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter:insert molar ratios; ensure fresh ligase and buffer [3] |

| Amplification & PCR | Overamplification artifacts; bias; high duplicate rate [3] | Too many cycles; inefficient polymerase or inhibitors; primer exhaustion or mispriming [3] | Reduce PCR cycles; use high-fidelity polymerases; optimize annealing temperatures [3] |

| Purification & Cleanup | Incomplete removal of small fragments or adapter dimers; sample loss; carryover of salts [3] | Wrong bead ratio; bead over-drying; inefficient washing; pipetting error [3] | Optimize bead:sample ratios; avoid over-drying beads; implement pipette calibration programs [3] |

How can researchers diagnose and prevent intermittent NGS failures in core facilities?

Intermittent failures often correlate with operator, day, or reagent batch variations. A case study from a shared core facility revealed that sporadic failures were primarily caused by:

Root Causes Identified:

- Deviations from protocol details: mixing method (vortex vs pipetting) or timing differences between operators [3]

- Ethanol wash solutions losing concentration over time through evaporation [3]

- Accidental discarding of beads instead of supernatant (or vice versa) during repetitive steps [3]

Corrective Steps & Impact:

- Introduced "waste plates" to temporarily catch discarded material, allowing retrieval in case of mistake [3]

- Highlighted critical steps in the SOP with bold text or color to draw attention [3]

- Switched to master mixes to reduce pipetting steps and errors [3]

- Enforced cross-checking, operator checklists, and redundant logging of steps [3]

Target Deconvolution Methodologies

What experimental approaches are available for target deconvolution in phenotypic screening?

Target deconvolution refers to the process of identifying the molecular target or targets of a particular chemical compound in a biological context [10]. This is essential for understanding the mechanism of action of compounds identified through phenotypic screens.

Diagram 1: Target Deconvolution Workflow Strategies

What are the key reagent solutions for chemical proteomics approaches?

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Target Deconvolution

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Probes | Immobilized compound on solid support [11] [10] | Isolate specific target proteins from complex proteome; identify direct binding partners | Requires knowledge of structure-activity relationship; modification may affect binding affinity [11] |

| Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) | Broad-spectrum cathepsin-C specific probe [11] | Monitor activity of specific enzyme classes; covalently label active sites | Requires reactive electrophile for covalent modification; targets specific enzyme families [11] |

| Photoaffinity Labels | Benzophenone, diazirine, or arylazide-containing probes [11] [10] | Covalent cross-linking upon light exposure; secures weakly bound interactions | Useful for integral membrane proteins and transient interactions; requires photoreactive group [10] |

| Click Chemistry Tags | Azide or alkyne tags [11] | Minimal structural perturbation for intracellular target identification; enables conjugation after binding | Particularly useful for intracellular targets; minimizes interference with membrane permeability [11] |

| Multifunctional Scaffolds | Benzophenone-based small molecule library [11] | Integrated screening and target isolation; combines photoreactive group, CLICK tag and protein-interacting functionality | Accelerates process from phenotypic screening to target identification [11] |

Polypharmacology and Drug Repositioning Strategies

How can polypharmacology guide drug repositioning efforts?

Polypharmacology involves the interactions of drug molecules with multiple targets of different therapeutic indications/diseases [12]. This approach is increasingly valuable for identifying new therapeutic uses for existing drugs.

Successful Applications:

- SARS-CoV-2 Treatment: Polypharmacology approaches identified drugs such as dihydroergotamine, ergotamine, bisdequalinium chloride, midostaurin, temoporfin, tirilazad, and venetoclax as multi-targeting agents against multiple SARS-CoV-2 proteins [13].

- Cancer Therapeutics: Drugs with multi-targeting potential are particularly interesting for repurposing because this dual synergistic strategy could offer better therapeutic alternatives and useful clinical candidates [12].

What computational and experimental workflows support polypharmacology research?

Diagram 2: Polypharmacology Drug Discovery Pipeline

What are the key reagent solutions for chemogenomics library development?

The development of specialized compound libraries is crucial for systematic exploration of target families. A recent example includes the NR3 nuclear hormone receptor chemogenomics library:

NR3 CG Library Characteristics:

- Comprehensive Coverage: 34 highly annotated and chemically diverse ligands covering all NR3 steroid hormone receptors [14]

- Selectivity Optimization: Compounds selected considering complementary modes of action, activity, selectivity, and lack of toxicity [14]

- Chemical Diversity: High scaffold diversity with 34 compounds representing 29 different skeletons [14]

- Validation: Proof-of-concept application validated endoplasmic reticulum stress resolving effects of NR3 CG subsets [14]

Integrating AI and Multi-Omics in Chemogenomics

How is artificial intelligence transforming genomic data analysis in drug discovery?

AI and machine learning algorithms have become indispensable in genomic data analysis, uncovering patterns and insights that traditional methods might miss [8].

Key AI Applications:

- Variant Calling: Tools like Google's DeepVariant utilize deep learning to identify genetic variants with greater accuracy than traditional methods [8]

- Disease Risk Prediction: AI models analyze polygenic risk scores to predict an individual's susceptibility to complex diseases [8]

- Drug Discovery: By analyzing genomic data, AI helps identify new drug targets and streamline the drug development pipeline [8]

What is the role of multi-omics integration in understanding polypharmacology?

Multi-omics approaches combine genomics with other layers of biological information to provide a comprehensive view of biological systems [8].

Multi-Omics Components:

- Transcriptomics: RNA expression levels [8]

- Proteomics: Protein abundance and interactions [8]

- Metabolomics: Metabolic pathways and compounds [8]

- Epigenomics: Epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation [8]

This integrative approach provides a comprehensive view of biological systems, linking genetic information with molecular function and phenotypic outcomes, which is particularly valuable for understanding the complex mechanisms underlying polypharmacological effects [8].

Chemogenomics research leverages chemical, genomic, and interaction data to discover new drug targets and therapeutic compounds, particularly for neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). Protein kinases represent a prime target class for these efforts due to their crucial roles in biological processes like signaling pathways, cellular communication, division, metabolism, and death [15]. The foundation of successful chemogenomics research lies in sourcing high-quality, validated data from public repositories and integrating it effectively within optimized Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) workflows. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to address specific issues researchers encounter when working with these complex data types and NGS methodologies, framed within the broader context of thesis research on optimizing NGS workflows for chemogenomics.

Essential Public Data Repositories

Publicly available datasets are invaluable for validating methods and benchmarking workflows in chemogenomics research. The table below summarizes essential repositories for sourcing chemical, genomic, and interaction data.

Table 1: Essential Public Data Repositories for Chemogenomics Research

| Repository Name | Data Type | Primary Use Case | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPI2ME (Oxford Nanopore) [16] | Real-time long-read sequencing data | Validation of NGS workflows against validated datasets (e.g., Genome in a Bottle, T2T assembly) | Cloud-based platform |

| PacBio SRA Database [16] | High-fidelity (HiFi) long-read sequences | Resolving complex genomic regions; benchmarking assembly and structural variant detection | PacBio website / NCBI SRA |

| 1000 Genomes Project (Phase 3) [16] | Human genetic variation from diverse populations | Studying population genetics and disease association; validating variant calls | IGSR / EBI portals |

| European Genome-Phenome Archive [16] | Exon Copy Number Variation (CNV) data | Orthogonal assessment of exon CNV calling accuracy in NGS | EGA portal |

| Chemogenomics Resources [15] | Protein kinase targets & ligand interactions | Prioritizing kinase drug targets and identifying potential inhibitors | Specialized tools (e.g., ChemBioPort, Chromohub, UbiHub) |

Troubleshooting NGS Workflows for Chemogenomics

Common NGS Preparation Failures and Solutions

Library preparation is a critical step where many NGS failures originate. The following table outlines common issues, their root causes, and corrective actions [3].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common NGS Library Preparation Failures

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Root Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Input & Quality [3] | Low yield; smear in electropherogram; low complexity | Degraded DNA/RNA; contaminants (phenol, salts); inaccurate quantification | Re-purify input; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit); check purity ratios (260/230 >1.8) |

| Fragmentation & Ligation [3] | Unexpected fragment size; inefficient ligation; adapter-dimer peaks | Over-/under-shearing; improper buffer conditions; suboptimal adapter-to-insert ratio | Optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter:insert ratios; ensure fresh ligase/buffer |

| Amplification & PCR [3] | Overamplification artifacts; high duplicate rate; bias | Too many PCR cycles; polymerase inhibitors; primer exhaustion | Reduce PCR cycles; re-purify to remove inhibitors; optimize primer and template concentrations |

| Purification & Cleanup [3] | Adapter dimer carryover; significant sample loss | Incorrect bead:sample ratio; over-dried beads; inadequate washing | Precisely follow bead cleanup protocols; avoid over-drying beads; use fresh wash buffers |

FAQs on Data Integration and Analysis

Q1: My NGS data has a high duplicate read rate. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A: A high duplicate rate often stems from over-amplification during library PCR (too many cycles) or from insufficient starting input material, which reduces library complexity [3]. To resolve this:

- Wet-Lab: Optimize your library prep by reducing the number of PCR cycles and ensuring accurate quantification of input DNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) instead of UV absorbance [3].

- Bioinformatics: During data analysis, use tools like FastQC to visualize the duplication levels and consider using deduplication tools in your pipeline, keeping in mind that some level of duplication is expected in targeted sequencing [17].

Q2: How can I minimize batch effects when scaling up my NGS experiments for a large chemogenomics screen?

A: Batch effects, often caused by researcher-to-researcher variation and reagent lot changes, can be mitigated by:

- Automation: Implementing automated sample prep systems to eliminate manual pipetting variability and improve consistency [18].

- Standardization: Using master mixes for reactions to reduce pipetting steps and inter-assay variation [3].

- Experimental Design: Processing cases and controls across different batches and dates, and including control samples in every batch for normalization during data analysis [18].

Q3: I suspect adapter contamination in my sequencing reads. How can I confirm and fix this?

A: Adapter contamination results from inefficient cleanup or ligation failures and produces sharp peaks at ~70-90 bp in an electropherogram [3].

- Confirmation: Use quality control tools like FastQC to detect overrepresented sequences, which will often match your adapter sequences [17].

- Solution:

- Wet-Lab: Optimize bead-based cleanup steps by using the correct bead-to-sample ratio to exclude small fragments effectively. Titrate adapter concentrations to find the optimal ratio that minimizes dimer formation [3].

- Bioinformatics: Use trimming tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove adapter sequences from your raw FASTQ files before alignment and analysis [17].

Q4: What is the most critical step to ensure high-quality data from a publicly available NGS dataset?

A: The most critical first step is to perform thorough quality control on the raw data. Before starting any analysis, you must [17]:

- Verify file type and structure (e.g., FASTQ, BAM, paired-end/single-end).

- Check read quality distribution using a tool like FastQC to identify issues with base quality, adapter contamination, or overrepresented sequences.

- Confirm metadata to ensure the reference genome version and experimental conditions are compatible with your research question.

Experimental Workflow and Visualization

Integrated Chemogenomics NGS Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the optimized end-to-end workflow for chemogenomics research, integrating data sourcing, sample preparation, and data analysis.

NGS Library Preparation Troubleshooting Logic

For diagnosing failed NGS library preparation, follow this logical troubleshooting pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for NGS and Chemogenomics Experiments

The following table details key reagents, their functions, and troubleshooting notes essential for robust NGS and chemogenomics workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions in NGS Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function | Troubleshooting Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorometric Quantification Kits (Qubit) [3] | Accurately measures nucleic acid concentration without counting non-template contaminants. | Prefer over UV absorbance (NanoDrop) to avoid overestimation of usable input material, a common cause of low yield. |

| Bead-Based Cleanup Kits [3] | Purifies and size-selects nucleic acid fragments after enzymatic reactions. | An incorrect bead-to-sample ratio can cause loss of desired fragments or adapter dimer carryover. Avoid over-drying beads. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Ligase & Buffer [3] | Binds adapters to fragmented DNA for sequencing. | Sensitive to enzyme activity and buffer conditions. Use fresh reagents and maintain optimal temperature for efficient ligation. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Mix [3] | Amplifies the library to add indexes and generate sufficient sequencing material. | Too many cycles cause overamplification artifacts and high duplicate rates. Use the minimum number of cycles necessary. |

| Fragmentation Enzymes [3] | Shears DNA to the desired insert size for library construction. | Over- or under-shearing reduces ligation efficiency. Optimize time and enzyme concentration for your sample type (e.g., FFPE, GC-rich). |

| Bioinformatics QC Tools (FastQC) [17] | Provides visual report on raw read quality, adapter content, and sequence duplication. | Essential first step for analyzing any dataset, public or private, to identify issues before proceeding with analysis. |

The journey of genomics in cancer research has been marked by pivotal breakthroughs that have reshaped our understanding of disease mechanisms and treatment paradigms. The discoveries surrounding KRAS and BRAF oncogenes represent landmark achievements in molecular oncology, revealing critical nodes in cancer signaling pathways that drive tumor progression. These historical discoveries laid the essential groundwork for large-scale genomic initiatives, most notably the 100,000 Genomes Project, which has dramatically expanded our ability to identify disease-causing genetic variants across diverse patient populations [19] [20]. This project, completed in December 2018, sequenced 100,000 whole genomes from patients with rare diseases and cancer, creating an unprecedented resource for the research community [20]. The convergence of foundational oncogene research with cutting-edge genomic sequencing has established new standards for personalized cancer treatment and diagnostic precision, while simultaneously introducing novel technical challenges that require sophisticated troubleshooting approaches within next-generation sequencing (NGS) workflows [21].

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Sample Quality & Preparation

Q: What are the primary causes of low DNA quality in FFPE samples and how can they be mitigated? A: DNA from Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) specimens suffers from fragmentation, crosslinks, abasic sites, and deamination artifacts that generate C>T mutations during sequencing. The 100,000 Genomes Project addressed this through optimized extraction protocols and bioinformatic correction methods to distinguish true variants from formalin-induced artifacts [20].

Q: How does sample quality impact variant calling sensitivity? A: Degraded samples exhibit reduced coverage uniformity and increased false positives, particularly in GC-rich regions. The project implemented rigorous QC thresholds, requiring minimum DNA integrity numbers (DIN > 7) and fragment size distributions for reliable variant detection [21].

Library Preparation & Sequencing

Q: What factors contribute to low library complexity in WGS experiments? A: Common causes include insufficient input DNA, PCR over-amplification, and suboptimal fragment size selection. The project utilized qualified automated library preparation systems with integrated size selection and qc checkpoints to maintain complexity while reducing hands-on time [22].

Q: How can batch effects in large-scale sequencing be minimized? A: The project employed standardized protocols across sequencing centers, including calibrated robotic liquid handling, matched reagent lots, and inter-run controls. Vendor-qualified workflows with predefined acceptance criteria ensured consistency across 100,000 genomes [22].

Data Analysis & Interpretation

Q: What bioinformatic approaches improve detection of structural variants in cancer genomes? A: The analysis pipeline incorporated multiple calling algorithms with integrated local assembly. For the KRAS and BRAF loci specifically, the project used duplicate marking, local realignment, and machine learning classifiers trained on validated variants to distinguish true oncogenic mutations from sequencing artifacts [21].

Q: How are variants of uncertain significance (VUS) handled in clinical reporting? A: The project established a tiered annotation system with evidence-based prioritization. Variants were cross-referenced against PanelApp gene panels and population frequency databases. Functional domains and known cancer hotspots (including specific KRAS codons 12/13/61 and BRAF V600) received prioritized interpretation [20].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Whole Genome Sequencing from Blood and Tissue

The 100,000 Genomes Project established this core methodology for generating comprehensive genomic data [21] [20]:

Sample Collection: Paired samples collected from cancer patients (blood and tumor tissue) or rare disease participants (blood from patient and parents)

DNA Extraction:

- Blood: Automated extraction from 3-5mL whole blood using magnetic bead-based platforms

- Tissue: Macro-dissection of FFPE sections with >70% tumor content or fresh-frozen equivalent

- Quality Control: Spectrophotometric (A260/280 ratio 1.8-2.0) and fluorometric quantification (minimum 1μg)

Library Preparation:

- Fragmentation: Acoustic shearing to 350bp insert size

- End Repair & A-tailing: Standard enzymatic treatment

- Adapter Ligation: Illumina paired-end adapters with dual-index barcodes

- PCR Amplification: Limited-cycle enrichment (4-6 cycles)

Sequencing:

- Platform: Illumina NovaSeq 6000

- Configuration: 150bp paired-end reads

- Coverage: 30X minimum for germline, 60X for tumor samples

- Quality Metrics: >80% bases ≥Q30

Protocol 2: Targeted Validation of KRAS/BRAF Mutations

This orthogonal confirmation method was employed for clinically actionable variants:

Variant Identification: Initial calling from WGS data using optimized parameters for oncogenic hotspots

Amplicon Design: Primers flanking KRAS codons 12/13/61 and BRAF V600 region

PCR Conditions:

- Template: 10ng DNA from original extraction

- Cycling: 95°C × 2min, [95°C × 30sec, 60°C × 30sec, 72°C × 45sec] × 35 cycles

- Purification: Exo-SAP treatment of amplicons

Sanger Sequencing:

- Chemistry: BigDye Terminator v3.1

- Capillary Electrophoresis: ABI 3730xl platform

- Analysis: Mutation confirmation via bidirectional sequencing

Table 1: Prognostic Genetic Factors Identified in the 100,000 Genomes Project [21]

| Gene | Cancer Types with Prognostic Association | Mutation Impact on Survival | Frequency in Cohort |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 | Breast, Colorectal, Lung, Ovarian, Glioma | Hazard Ratio: 1.2-2.1 | 8.7% |

| BRAF | Colorectal, Lung, Glioma | Hazard Ratio: 1.5-2.3 | 3.2% |

| PIK3CA | Breast, Colorectal, Endometrial | Hazard Ratio: 1.1-1.8 | 6.4% |

| PTEN | Endometrial, Glioma, Renal | Hazard Ratio: 1.4-2.0 | 2.9% |

| KRAS | Colorectal, Lung, Pancreatic | Hazard Ratio: 1.3-2.2 | 5.1% |

Table 2: Technical Performance Metrics of the 100,000 Genomes Project [21] [20]

| Parameter | Blood-Derived DNA | FFPE-Derived DNA | Fresh-Frozen Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Coverage | 35X | 58X | 62X |

| Mapping Rate | 99.2% | 97.8% | 98.9% |

| PCR Duplicates | 8.5% | 14.2% | 9.1% |

| Variant Concordance | 99.8% | 98.5% | 99.6% |

| Sensitivity (SNVs) | 99.5% | 97.2% | 99.1% |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for NGS Workflows [22] [21] [20]

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in Featured Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | Massive parallel sequencing | Primary sequencing platform for 100,000 Genomes Project |

| Magnetic bead-based NA extraction | Nucleic acid purification | Standardized DNA isolation from blood and tissue samples |

| FFPE DNA restoration kits | Repair of formalin-damaged DNA | Improved sequence quality from archival clinical samples |

| Illumina paired-end adapters | Library molecule identification | Sample multiplexing and tracking across batches |

| PanelApp virtual gene panels | Evidence-based gene-disease association | Variant prioritization and clinical interpretation |

| Automated liquid handling robots | Library preparation automation | Improved reproducibility and throughput for 100,000 samples |

Workflow Diagrams

NGS Data Generation and Analysis Pipeline

Cancer Signaling Pathway with Therapeutic Implications

100,000 Genomes Project Cohort Selection Process

From Data to Discovery: Implementing NGS-Chemogenomics Workflows in the Lab

In chemogenomics research, the success of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) workflows critically depends on the quality and integrity of the input nucleic acids. Inadequate extraction methods can introduce biases, artifacts, and failures in downstream applications, ultimately compromising drug discovery and development efforts. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and strategic guidance for extracting various nucleic acid types from diverse biological samples, enabling researchers to optimize this crucial first step in the NGS pipeline. [23] [24]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the five universal steps in any nucleic acid extraction protocol? Regardless of the specific chemistry or sample type, most nucleic acid purification protocols consist of five fundamental steps: 1) Creation of Lysate to disrupt cells and release nucleic acids, 2) Clearing of Lysate to remove cellular debris and insoluble material, 3) Binding of the target nucleic acid to a purification matrix, 4) Washing to remove proteins and other contaminants, and 5) Elution of the purified nucleic acid in an aqueous buffer. [24]

2. When should I consider magnetic bead-based purification over column-based methods? Magnetic bead-based systems are particularly advantageous for automated, high-throughput workflows. They offer higher purity and yields due to thorough mixing and exposure to target molecules, gentle separation that minimizes nucleic acid shearing (critical for HMW DNA), and scalability for processing many samples simultaneously. They also provide flexibility to target nucleic acids of specific fragment sizes. [25]

3. Why is the co-purification of cfDNA and cfRNA from liquid biopsies recommended? Co-purification is a powerful strategy to maximize the analytical sensitivity of liquid biopsy assays. Since the vast majority of circulating nucleic acids are non-cancerous, isolating both cfDNA and cfRNA from the same plasma aliquot increases the chance of capturing tumor-derived molecules. This approach is also cost- and time-effective and allows for the maximal use of valuable patient samples. [26]

4. How can I increase the detection sensitivity for low-abundance nucleic acids like cfDNA? For low-abundance targets, sensitivity can be enhanced by: a) Increasing the input volume of the starting sample (e.g., using more plasma), b) Increasing the volume of the extracted nucleic acid eluate added to a downstream digital PCR reaction (provided it does not cause inhibition), and c) Employing advanced error-correcting molecular methods. [26]

5. What is a key indicator of high-quality, pure cell-free DNA? High-quality cfDNA should show a characteristic fragment size distribution averaging around ~170 bp when analyzed by microfluid electrophoresis (e.g., TapeStation). A high percentage of fragments in this range (e.g., 64-94%) indicates good quality cfDNA with low fractions of high molecular weight (HMW) DNA contamination from lysed cells. [26]

Troubleshooting Common Extraction Issues

Problem: Low Yield from Plasma or Serum Samples

- Potential Cause: Inefficient binding of nucleic acids to the purification matrix due to improper buffer conditions or overloading.

- Solution:

- Ensure the lysate contains the correct concentration of chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine hydrochloride) or other binding agents as specified in the kit protocol. [24]

- Do not exceed the recommended binding capacity of the kit. If processing large plasma volumes (>1 mL), select a kit validated for that scale. [26]

- For magnetic bead-based systems, ensure thorough resuspension and mixing during the binding step to maximize contact with the target molecules. [25]

Problem: Co-purified DNA and RNA are not compatible with my downstream assays.

- Potential Cause: Carryover of contaminants like salts, alcohols, or enzymes from the extraction process.

- Solution:

- Ensure all wash buffers are prepared correctly and that wash steps are performed thoroughly. [24]

- After the final wash, briefly spin the column or plate and remove any residual wash buffer with a pipette.

- If using a column, allow it to air-dry for a few minutes before elution to let residual ethanol evaporate.

- To obtain pure DNA, add RNase A to the elution buffer. To obtain pure RNA, perform an on-column DNase digestion step. [24]

Problem: Genomic DNA is Sheared or Degraded

- Potential Cause: Overly vigorous physical disruption during lysis or excessive centrifugation.

- Solution:

- For tissues, use gentle homogenization methods and avoid generating heat.

- When extracting High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA, use specialized kits designed to minimize fragmentation, such as those based on magnetic bead technology that avoids columns, filters, and excessive centrifugation. [25]

- Process samples quickly and on ice to inhibit endogenous nucleases.

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Samples

- Potential Cause: Sample-to-sample variation in lysis efficiency or human error in manual protocols.

- Solution:

- Standardize sample input amounts and lysis times as much as possible.

- For complex or difficult-to-lyse samples (e.g., tissue, plants, bacteria), use a combination of physical, chemical, and enzymatic lysis methods. [24]

- Transition to semi-automated or automated purification systems to enhance reproducibility and reduce hands-on time. [26] [25]

Experimental Protocols and Data Comparison

Protocol 1: Sequential DNA/RNA Co-purification from a Single Sample

This protocol is ideal for maximizing information from precious samples like patient biopsies or blood. [25]

- Lysis: Apply a powerful, proprietary lysis solution to the sample (e.g., whole blood, bone marrow, or FFPE tissue) to completely disrupt cells and release both DNA and RNA simultaneously.

- Separation: The lysate is treated to separate the genomic DNA from the total RNA.

- Parallel Binding: The divided lysate is transferred to a purification plate where DNA binds to one set of wells and RNA binds to another.

- Washing and Elution: Independent wash and elution steps are performed for the DNA and RNA bound to their respective matrices, yielding separate, ready-to-use eluates.

Protocol 2: Evaluation of cfDNA/cfRNA Co-purification Kit Performance Using dPCR

This digital PCR (dPCR) framework allows for the precise quantification of extraction efficiency. [26]

- Sample Processing: Extract nucleic acids from a range of plasma input volumes (e.g., 0.06–4 mL) using the co-purification kits under evaluation.

- DNase Treatment: Treat an aliquot of the eluate with DNase to remove DNA, allowing for specific cfRNA quantification.

- dPCR Quantification: Use optimized duplex dPCR assays targeting highly abundant genes (e.g., CAVIN2/NRGN and AIF1/B2M) to quantify both cfDNA and cfRNA concentrations in the eluate.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the concentration (copies/µL) and total yield for both cfDNA and cfRNA to compare the performance of different kits across input volumes.

Performance Comparison of Nucleic Acid Extraction Methods

Table 1: Comparison of short-read sequencing technologies and their characteristics. [9]

| Platform | Sequencing Technology | Amplification Type | Read Length (bp) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing-by-synthesis | Bridge PCR | 36-300 | Overcrowding on the flow cell can spike error rate to ~1% |

| Ion Torrent | Sequencing-by-synthesis | Emulsion PCR | 200-400 | Inefficient determination of homopolymer length |

| 454 Pyrosequencing | Sequencing-by-synthesis | Emulsion PCR | 400-1000 | Deletion/insertion errors in homopolymer regions |

| SOLiD | Sequencing-by-ligation | Emulsion PCR | 75 | Substitution errors; under-represents GC-rich regions |

Table 2: Characteristics of different DNA sample types and purification challenges. [24]

| DNA Sample Type | Source | Expected Size | Typical Yield | Key Purification Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic (gDNA) | Cells (nucleus) | 50kb–Mb | Varies, high (µg–mg) | Shearing during extraction; contamination with proteins/RNA |

| High Molecular Weight (HMW) | Blood, cells, tissue | >100 kb | Varies, high (µg–mg) | Extreme sensitivity to fragmentation; requires very gentle handling |

| Cell-free (cfDNA) | Plasma, serum | 160–200 bp | Very low (<20 ng) | Low abundance; contamination with genomic DNA |

| FFPE DNA | FFPE tissue | Typically <1kb | Low (ng) | Cross-linked and fragmented; requires special deparaffinization |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents and kits for nucleic acid extraction, categorized by primary application.

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| MagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit [25] | Magnetic bead-based isolation of circulating cfDNA from plasma, serum, or urine. | Liquid biopsy for cancer genomics; non-invasive cancer diagnostics. |

| MagMAX HMW DNA Kit [25] | Isolates high-integrity DNA with large fragments >100 kb using gentle magnetic bead technology. | Long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio, Nanopore) for structural variation studies. |

| MagMAX Sequential DNA/RNA Kit [25] | Sequentially isolates high-quality gDNA and total RNA from a single sample of whole blood or bone marrow. | Hematological cancer studies; maximizing data from precious clinical samples. |

| MagMAX FFPE DNA/RNA Ultra Kit [25] | Enables sequential isolation of DNA and RNA from the same FFPE tissue sample after deparaffinization. | Archival tissue analysis; oncology research using biobanked samples. |

| miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Advanced Kit [26] | Manual spin-column kit for co-purification of cfDNA and cfRNA (including miRNA) from neat plasma. | Liquid biopsy workflows focusing on both DNA and RNA biomarkers. |

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., guanidine HCl) [24] | Disrupt cells, denature proteins (inactivate nucleases), and enable nucleic acid binding to silica matrices. | Essential component of lysis and binding buffers in silica-based purification. |

| RNase A [24] | Enzyme that degrades RNA. Added to the elution buffer to remove contaminating RNA from DNA preparations. | Production of pure, RNA-free genomic DNA for sequencing or PCR. |

| DNase I | Enzyme that degrades DNA. Used in on-column treatments to remove contaminating DNA from RNA preparations. | Production of pure, DNA-free total RNA for transcriptomic applications like RNA-seq. |

Workflow Visualization

Nucleic Acid Extraction Workflow. The process begins with sample-specific lysis, followed by a critical separation step where the purification path is chosen based on the target molecule(s). Final purification and elution yield nucleic acids ready for NGS.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low or Inconsistent Library Yields

Problem: Automated runs produce DNA libraries with lower or more variable concentrations compared to manual preparation.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate liquid handling | Check pipette calibration logs; verify dispensed volumes in clean-up steps. | Recalibrate the liquid handling module; use liquid level detection for viscous reagents [27]. |

| Inefficient bead mixing | Observe bead resuspension during clean-up steps; look for pellet consistency. | Optimize the mixing speed and duration in the protocol; ensure the magnetic module is correctly engaged/disengaged [28]. |

| Suboptimal reagent handling | Confirm reagents are stored and thawed according to the kit manufacturer's instructions. | Ensure all reagents are kept on a cooling block during the run; minimize freeze-thaw cycles by creating single-use aliquots [4]. |

Issue 2: Poor Sequencing Quality or Coverage Uniformity

Problem: Libraries pass QC but produce low-quality sequencing data with uneven coverage.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-contamination | Review sample layout on the deck; check for splashes or carryover between wells. | Use fresh pipette tips for every transfer; increase spacing between sample rows on the deck [27]. |

| Incomplete enzymatic reactions | Verify incubation times and temperatures for tagmentation and PCR steps. | Validate the accuracy of the heating/cooling module; ensure lids are heated to prevent condensation [29]. |

| Inaccurate library normalization | Re-quantify pooled libraries after automated normalization. | Confirm the normalization algorithm and input concentrations; use fluorometric methods over spectrophotometric for DNA quantification [28]. |

Issue 3: System Integration and Software Errors

Problem: The robotic platform fails to execute the protocol or interfaces poorly with other systems.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| File or format mismatch | Check that the protocol file is the correct version for the software and deck layout. | Re-upload the protocol from a verified source; use scripts provided and validated by the platform vendor [29] [27]. |

| Hardware communication failure | Review error logs for communication timeouts with deck modules (heater, magnet). | Power cycle the instrument; reseat all cable connections for deck modules [30]. |

| LIMS integration failure | Confirm sample and reagent ID formats match between the LIMS and automation software. | Standardize naming conventions; work with IT/automation specialists to validate the data transfer pipeline [27]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our automated library preps are consistent but our DNA yields are consistently lower than manual preps. What should we check? A1: First, verify the calibration of the liquid handler, specifically for small volumes (< 10 µL) which are common in library prep kits. Second, focus on the bead-based clean-up steps. Ensure the bead mixture is homogenous before aspiration and that the mixing steps post-elution are vigorous and long enough to fully resuspend the pellets. Incomplete resuspension is a common cause of DNA loss [27] [28].

Q2: How can we validate the performance of a new automated NGS library prep workflow? A2: A robust validation should include three key components:

- Yield and Quality Metrics: Compare the DNA concentration and size distribution of automated vs. manual libraries using a fragment analyzer [28].

- Sequencing Performance: Sequence the libraries and compare key metrics such as Q30 scores, coverage uniformity, and GC bias. The results should be highly comparable [29].

- Reproducibility: Process the same sample across multiple automated runs and by different operators. Assess the coefficient of variation for library yield and sequencing metrics to confirm consistency [29].

Q3: What are the critical steps to automate for the biggest gain in reproducibility? A3: The most significant gains come from automating steps prone to human timing and technique variations. Prioritize:

- Reagent Dispensing: Automated pipetting eliminates volume inconsistencies [27].

- Bead-Based Clean-ups: Robots provide precise and consistent control over incubation and mixing times, which is critical for reproducible recovery [29] [28].

- Library Normalization and Pooling: Automation ensures precise, volumetric normalization leading to balanced multiplexing [28].

Q4: How does automation help with regulatory compliance in a diagnostic or chemogenomics setting? A4: Automated systems enhance compliance by providing an audit trail, standardizing protocols to minimize batch-to-batch variation, and enabling integration with Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) for complete traceability. This supports adherence to standards like ISO 13485 and IVDR, which require strict documentation and process control [27].

Experimental Data & Protocols

The following table summarizes quantitative data from studies that compared automated and manual NGS library preparation, demonstrating the equivalence and advantages of automation [29] [28].

| Performance Metric | Manual Workflow | Automated Workflow | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hands-on Time (for 8 samples) | ~125 minutes [29] | ~25 minutes [29] | 80% Reduction |

| Total Turn-around Time | ~200 minutes [29] | ~170 minutes [29] | 30 minutes faster |

| Library Yield (DNA concentration) | Variable (e.g., 10.9 ng/µl in one case) [29] | Consistent, median 1.5-fold difference from manual [29] | Comparable, more reproducible |

| cgMLST Typing Concordance | 100% (Reference) [29] | 100% [29] | Full concordance |

| Barcode Balance Variability | Higher variability (manual pooling) [28] | Lower variability (automated pooling) [28] | Improved multiplexing |

| Sequencing Quality (Q30 Score) | >90% [28] | >90% [28] | Equally high quality |

Detailed Automated Protocol: Illumina DNA Prep

This protocol, adapted for a robotic liquid handler like the flowbot ONE or Myra, details the key steps for a reproducible automated workflow [29] [28].

Experimental Setup:

- Instrument: flowbot ONE (with 1- and 8-channel pipetting modules, heating/cooling, and magnetic devices) or Myra liquid handler.

- Samples: 8-24 samples per run (e.g., bacterial genomic DNA).

- Input: 20-150 ng of DNA per sample.

- Consumables: Use DNase/RNAse-free, low-retention tips and plates to prevent enzymatic inhibition and sample loss [4].

Methodology:

- Pre-Run Setup:

- Thaw all Illumina DNA Prep reagents and keep on a cooling block on the deck.

- Manually add unique Illumina DNA/RNA UD Indexes to each sample well to minimize freeze-thaw cycles of master stocks [29].

- Load the validated protocol script onto the liquid handler.

Automated Run:

- Tagmentation: The robot dispenses the tagmentation mix onto the DNA samples and transfers the plate to the off-deck thermal cycler.

- Post-Tagmentation Clean-up: The plate is returned to the deck. The system adds bead-based clean-up buffer, executes the incubation, engages the magnetic module, and removes the supernatant after bead pelleting.

- PCR Amplification: The robot dispenses the PCR mix into the samples. The user transfers the plate to a thermal cycler for amplification.

- Post-Amplification Clean-up: The plate is returned to the robot for a final bead-based clean-up and elution of the final library in a resuspension buffer. The workflow includes safe stopping points after major steps [29] [28].

Post-Processing:

- The finished libraries are quantified (e.g., via fluorometry or qPCR).

- The liquid handler is used to normalize and pool the libraries based on their concentrations [28].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Component | Function | Key Considerations for Automation |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kit (e.g., Illumina DNA Prep) | Provides enzymes and buffers for DNA fragmentation, end-repair, adapter ligation, and PCR. | Select kits validated for automation. Ensure reagent viscosities are compatible with automated liquid handling [29] [4]. |

| Magnetic Beads | Used for size selection and purification of DNA fragments between enzymatic steps. | Consistency in bead size and binding capacity is critical. Optimize mixing steps to keep beads in suspension [28]. |

| Index Adapters (Barcodes) | Uniquely identify each sample for multiplexing in a single sequencing run. | Manually add these expensive reagents to minimize freeze-thaw cycles and reduce the risk of robot error [29]. |

| DNase/RNAse-Free Consumables | Plates, tubes, and pipette tips. | Use low-retention tips and plates certified to be free of contaminants that can inhibit enzymatic reactions [4]. |

| Liquid Handling Robot | Automates pipetting, mixing, and incubation steps. | Platforms like flowbot ONE or Myra are equipped with magnetic modules, heating/cooling, and precise pipetting for end-to-end automation [29] [28]. |

Chemogenomics represents a powerful paradigm in modern drug discovery, integrating vast chemical and biological information to understand the complex interactions between drugs and their protein targets. The accurate prediction of Drug-Target Interactions (DTI) sits at the core of this field, serving as a critical component for accelerating therapeutic development, identifying new drug indications, and advancing precision medicine. Traditional experimental methods for DTI identification are notoriously time-consuming, resource-intensive, and low-throughput, often requiring years of laboratory work and substantial financial investment. The emergence of sophisticated machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) methodologies has revolutionized this landscape, offering computational frameworks capable of predicting novel interactions with remarkable speed and accuracy by learning complex patterns from chemogenomic data.

These computational approaches, however, are deeply intertwined with the quality and nature of the biological data they utilize. The rise of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies has provided an unprecedented volume of genomic and transcriptomic data, enriching the feature space available for DTI models and creating new opportunities and challenges for model performance and interpretation. This technical support document provides a comprehensive overview of modern chemogenomic approaches for DTI prediction, framed within the context of optimizing NGS workflows. It is designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the practical knowledge to implement, troubleshoot, and optimize these integrated experimental-computational pipelines.

Core Machine Learning Methodologies in DTI Prediction

Fundamental Approaches and Feature Representation

Modern DTI prediction models rely on informative numerical representations (features) of both drugs and target proteins. The choice of feature representation significantly influences model performance and its applicability to novel drug or target structures.

Drug Feature Representation: Molecular structure is commonly encoded using MACCS keys (Molecular ACCess System), a type of structural fingerprint that represents the presence or absence of 166 predefined chemical substructures. This provides a fixed-length binary vector that captures key functional groups and topological features [31]. Other popular representations include extended connectivity fingerprints (ECFPs) and learned representations from molecular graphs.

Protein Feature Representation: Target proteins are often described by their amino acid composition (the frequency of each amino acid) and dipeptide composition (the frequency of each adjacent amino acid pair). These compositions provide a global, sequence-order-independent profile of the protein that is effective for machine learning models. More advanced methods use evolutionary information from position-specific scoring matrices (PSSMs) or learned embeddings from protein sequences [31] [32].

The integration of these heterogeneous data sources is a active research area. Frameworks like DrugMAN exemplify this trend, leveraging multiple drug-drug and protein-protein networks to learn robust features using Graph Attention Networks (GATs), followed by a Mutual Attention Network (MAN) to capture intricate interaction patterns [33].

Advanced Deep Learning Architectures

Deep learning architectures have pushed the boundaries of DTI prediction by automatically learning relevant features from raw or minimally processed data.

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): Effective at extracting local, translation-invariant patterns from protein sequences (treated as 1D data) or from 2D structural representations of molecules [32].

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Transformers: Particularly suited for sequential data like protein sequences. RNNs, especially Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, can capture long-range dependencies. Transformer-based models, with their self-attention mechanisms, have shown superior performance in modeling complex contextual relationships within sequences [32].

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): As molecules are inherently graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges), GNNs provide a natural and powerful framework for learning drug representations. Models like MDCT-DTA utilize multi-scale graph diffusion convolution to capture intricate atomic interactions [31].

- Hybrid Models: Many state-of-the-art approaches combine multiple architectures. For instance, DeepLPI integrates a ResNet-based 1D CNN for initial feature extraction from raw sequences with a bi-directional LSTM to model temporal dependencies, culminating in a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) for final prediction [31].

Table 1: Summary of Advanced Deep Learning Models for DTI Prediction

| Model Name | Core Architecture | Key Innovation | Reported Performance (Dataset) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAN+RFC [31] | Generative Adversarial Network + Random Forest | Uses GANs for data balancing to address class imbalance. | Accuracy: 97.46%, ROC-AUC: 99.42% (BindingDB-Kd) |

| DrugMAN [33] | Graph Attention Network + Mutual Attention Network | Integrates multiplex heterogeneous functional networks. | Best performance under four different real-world scenarios. |

| MDCT-DTA [31] | Multi-scale Graph Diffusion + CNN-Transformer | Combines multi-scale diffusion and interactive learning for DTA. | MSE: 0.475 (BindingDB) |

| DeepLPI [31] | ResNet-1D CNN + bi-directional LSTM | Processes raw drug and protein sequences end-to-end. | AUC-ROC: 0.893 (BindingDB training set) |

| BarlowDTI [31] | Barlow Twins Architecture + Gradient Boosting | Focuses on structural properties of proteins; resource-efficient. | ROC-AUC: 0.9364 (BindingDB-kd benchmark) |

Integrating and Optimizing NGS Workflows for Chemogenomics

The predictive power of any DTI model is contingent on the quality and relevance of the underlying biological data. NGS technologies provide deep insights into the genomic and functional context of drug targets, but the resulting data must be carefully integrated and the NGS workflows meticulously optimized to ensure they serve the goals of chemogenomic research.

The Role of NGS Data in DTI Prediction

NGS data enhances DTI prediction in several key ways:

- Target Identification and Validation: Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) help identify genes associated with diseases, highlighting potential new drug targets [8].

- Understanding Target Variability: NGS reveals genetic variations (SNPs, indels) in target proteins across populations. This information is crucial for pharmacogenomics, predicting variable drug responses, and personalizing treatments [7] [8].

- Multi-omics Integration: Combining genomics with transcriptomics (RNA-Seq) and epigenomics provides a systems-level view of cellular states. This helps in understanding how gene expression and regulation in specific tissues or disease conditions (e.g., cancer) influence a drug's effect, moving beyond static sequence information [34] [8].

Key NGS Considerations for Robust DTI Models

To generate data that reliably informs DTI models, specific NGS parameters must be prioritized.

- Read Length and Coverage: For variant calling in target genes, short-read sequencing (e.g., Illumina) with high coverage depth is often preferred due to its base-level accuracy and cost-effectiveness for large cohorts [35]. For resolving complex genomic regions, repetitive sequences, or full-length transcript isoforms, long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore) is invaluable [36].

- Spatial Context: Emerging spatial transcriptomics technologies allow for the mapping of gene expression within the context of tissue architecture. This is particularly relevant for oncology drug discovery, as it can reveal tumor heterogeneity and the interaction between cancer cells and their microenvironment [34].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common experimental and computational challenges faced when integrating NGS workflows with DTI prediction pipelines.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My DTI model performs well on training data but generalizes poorly to novel protein targets. What could be the issue? A: This is a classic problem of model overfitting and data scarcity, particularly for proteins with low sequence homology to those in the training set. To address this:

- Utilize Transfer Learning: Leverage pre-trained protein language models (e.g., from Transformer architectures) that have learned generalizable features from vast, diverse protein sequence databases [32].

- Incorporate Heterogeneous Data: Use models like DrugMAN that integrate multiple sources of biological information (e.g., protein-protein interaction networks, Gene Ontology terms) to create richer, more context-aware protein representations that extend beyond the primary sequence [33].

- Data Augmentation: Employ sequence-based augmentation techniques or use generative models to create synthetic, realistic training examples for underrepresented target families.

Q2: My NGS data on target expression is noisy and is leading to inconsistent DTI predictions. How can I improve data quality? A: Noisy NGS data often stems from upstream library preparation. Focus on:

- Rigorous QC: Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) for accurate DNA quantification instead of UV absorbance, and an instrument like the BioAnalyzer to check for adapter contamination and fragment size distribution [3].

- Optimized Library Prep: If using amplicon-based approaches (e.g., for variant validation), ensure precise primer design and optimize PCR conditions to minimize off-target amplification and artifacts. Consider two-step indexing to reduce index hopping [3].

- Host Depletion in Relevant Samples: When working with clinical samples (e.g., tumor biopsies, infected tissue), a high host DNA background can obscure microbial or viral target signals or waste sequencing depth. Implement host depletion methods, such as the novel ZISC-based filtration, which can achieve >99% white blood cell removal and significantly enrich for microbial pathogen content [37].

Q3: What is the most significant data-related challenge in DTI prediction, and how can it be mitigated? A: Data imbalance is a pervasive issue, where the number of known interacting drug-target pairs (positive class) is vastly outnumbered by non-interacting or unlabeled pairs. This leads to models that are biased toward the majority class and exhibit high false-negative rates.

- Solution: A highly effective approach is the use of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). As demonstrated in a 2025 study, GANs can generate high-quality synthetic data for the minority class (interacting pairs), effectively balancing the dataset. This approach, combined with a Random Forest classifier, achieved a sensitivity of 97.46% and a notable reduction in false negatives on the BindingDB-Kd dataset [31].

Q4: How do I choose between a traditional ML model and a more complex DL model for my DTI project? A: The choice depends on your data and goals.

- Traditional ML (e.g., SVM, Random Forest): Preferable when working with well-curated, fixed-length feature vectors (like fingerprints and compositions) and when the dataset is small to medium in size. These models are often more interpretable and computationally less demanding [31].

- Deep Learning (e.g., GNNs, Transformers): Necessary when learning directly from raw data (e.g., SMILES strings, FASTA sequences), when dealing with highly complex and non-linear structure-activity relationships, or when integrating heterogeneous, high-dimensional data. They typically require large amounts of training data to avoid overfitting [31] [32].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Workflows

Problem: Low Library Yield in NGS Sample Preparation Low yield can cause poor sequencing coverage, leading to insufficient data for downstream analysis and unreliable feature extraction for DTI models.

- Root Causes and Corrective Actions:

- Cause: Poor input DNA/RNA quality or contamination from salts, phenol, or EDTA.

- Fix: Re-purify the input sample using clean columns or beads. Ensure 260/230 and 260/280 ratios are within optimal ranges (e.g., ~1.8 and ~2.0 respectively) [3].

- Cause: Inaccurate quantification via UV spectrophotometry.

- Fix: Use fluorometric methods (Qubit, PicoGreen) for accurate quantification of usable nucleic acid, as UV methods can overestimate concentration due to contaminants [3].

- Cause: Overly aggressive purification or size selection leading to sample loss.

- Fix: Optimize bead-based cleanup ratios and avoid over-drying the bead pellet, which makes resuspension inefficient [3].

Problem: High Duplicate Read Rates in NGS Data High duplication rates indicate low library complexity, meaning you are sequencing the same original molecule multiple times, which reduces effective coverage and can introduce bias.

- Root Causes and Corrective Actions:

- Cause: Insufficient input material, leading to over-amplification during PCR.

- Fix: Use the recommended amount of input DNA/RNA and minimize the number of PCR cycles. If yield is low, it is better to repeat the amplification from leftover ligation product than to over-amplify a weak product [3].

- Cause: Fragmentation bias, where certain genomic regions are over-represented.

- Fix: Optimize fragmentation parameters (time, energy) to ensure a uniform and random distribution of fragment sizes [3].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials critical for successful NGS and DTI prediction experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated NGS and DTI Workflows

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Kit |

|---|---|---|

| Host Depletion Filter | Selectively removes human host cells from blood or tissue samples to enrich microbial pathogen DNA for mNGS. | ZISC-based filtration device (e.g., "Devin" from Micronbrane); achieves >99% WBC removal [37]. |

| Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit | Post-extraction depletion of CpG-methylated host DNA to enrich for microbial sequences. | NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit (New England Biolabs) [37]. |

| DNA Microbiome Kit | Uses differential lysis to selectively remove human host cells while preserving microbial integrity. | QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit (Qiagen) [37]. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Prepares fragmented DNA for sequencing by adding adapters and barcodes; critical for data quality. | Ultra-Low Library Prep Kit (Micronbrane) used in sensitive mNGS workflows [37]. |

| MACCS Keys | A standardized set of 166 structural fragments used to generate binary fingerprint features for drug molecules in machine learning. | Used as a core drug feature representation method in DTI studies [31]. |

| Spike-in Control Standards | Validates the entire mNGS workflow, from extraction to sequencing, by providing a known quantitative signal. | ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control (Zymo Research) [37]. |

Workflow Diagrams and Data Presentation

Integrated NGS and DTI Prediction Workflow

The following diagram visualizes the integrated pipeline from biological sample to DTI prediction, highlighting key steps where optimization is critical.

Performance Comparison of DTI Models

The table below quantitatively summarizes the performance of various state-of-the-art DTI models as reported in recent literature, providing a benchmark for expected outcomes.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Recent DTI Models on BindingDB Datasets [31]

| Model / Dataset | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | F1-Score (%) | ROC-AUC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAN+RFC (Kd) | 97.46 | 97.49 | 97.46 | 98.82 | 97.46 | 99.42 |

| GAN+RFC (Ki) | 91.69 | 91.74 | 91.69 | 93.40 | 91.69 | 97.32 |

| GAN+RFC (IC50) | 95.40 | 95.41 | 95.40 | 96.42 | 95.39 | 98.97 |

| BarlowDTI (Kd) | - | - | - | - | - | 93.64 |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core difference between mNGS and tNGS in pathogen detection?

The core difference lies in the breadth of sequencing. Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) is a comprehensive, hypothesis-free approach that sequences all nucleic acids in a sample, allowing for the detection of any microorganism present [38]. In contrast, Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing (tNGS) uses pre-designed primers or probes to enrich and sequence only specific genetic targets of a predefined set of pathogens, which increases sensitivity for those targets and allows for simultaneous detection of DNA and RNA pathogens [38] [39].

Q2: When should I choose tNGS over mNGS for my pathogen identification study?

Targeted NGS (tNGS) is preferable for routine diagnostic testing when you have a specific suspect and want to detect antimicrobial resistance genes or virulence factors. mNGS is better suited for detecting rare, novel, or unexpected pathogens that would not be included on a targeted panel [39]. The decision can also be influenced by cost and turnaround time, as tNGS is generally less expensive and faster than mNGS [39].

Q3: What are the common causes of low library yield in NGS preparation, and how can I fix them?

Low library yield can stem from several issues during sample preparation. The table below outlines common causes and their solutions [3].

Table: Troubleshooting Low NGS Library Yield

| Root Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality/Contaminants | Enzyme inhibition from residual salts, phenol, or EDTA. | Re-purify input sample; ensure 260/230 > 1.8; use fresh wash buffers. |

| Inaccurate Quantification | Suboptimal enzyme stoichiometry due to concentration errors. | Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) over UV; calibrate pipettes. |

| Fragmentation Issues | Over- or under-fragmentation reduces adapter ligation efficiency. | Optimize fragmentation time/energy; verify fragment distribution beforehand. |

| Suboptimal Adapter Ligation | Poor ligase performance or incorrect adapter-to-insert ratio. | Titrate adapter:insert ratio; use fresh ligase/buffer; optimize incubation. |

Q4: How can I use in silico target prediction for drug repurposing in antimicrobial research?

In silico target prediction methods, such as MolTarPred, can systematically identify potential off-target effects of existing drugs by calculating the structural similarity between a query drug molecule and a database of known bioactive compounds [40]. This "target fishing" can reveal hidden polypharmacology, suggesting new antimicrobial indications for approved drugs, which saves time and resources compared to de novo drug discovery [40]. For example, this approach has suggested the rheumatoid arthritis drug Actarit could be repurposed as a Carbonic Anhydrase II inhibitor for other conditions [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting Pathogen Detection Failures in tNGS

Problem: A tNGS run for BALF samples returns no detectable signals for expected pathogens, or shows high background noise.

Investigation Flowchart: The following diagram outlines a systematic diagnostic workflow.

Detailed Corrective Actions:

- Re-purify Sample: If input quality is poor, use a clean-column or bead-based purification kit to remove contaminants like phenol, salts, or polysaccharides. Always validate quantity with a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit) rather than absorbance alone, as the latter can overestimate concentration [3].

- Optimize Ligation and PCR: A sharp peak at ~70-90 bp on an electropherogram indicates adapter dimers. To fix this, titrate the adapter-to-insert molar ratio and avoid excessive PCR cycles during library amplification, as overcycling can also skew representation and increase duplicates [3].

Guide 2: Addressing Poor Specificity in mNGS Wet-Lab Workflow

Problem: mNGS results report a high number of background or contaminating microbes, making true pathogens difficult to distinguish.

Investigation Flowchart: Follow this logic to resolve specificity issues.

Detailed Corrective Actions:

- Improve Host DNA Depletion: Use a commercial human DNA depletion kit (e.g., MolYsis) during nucleic acid extraction. This is a critical step for samples with high host content, like BALF, as it increases the proportion of microbial reads available for sequencing [38].

- Apply Rigorous Bioinformatics Thresholds: Use a reads-per-million (RPM) threshold to filter out background noise. For example, one protocol defines a positive result if the RPM ratio of the sample to the negative control is ≥ 10 for pathogens present in the control, or if the sample RPM is ≥ 0.05 for pathogens absent from the control [39].

Guide 3: Resolving Data Analysis and Interpretation Challenges

Problem: After sequencing, the data analysis pipeline produces confusing or unreliable variant calls or pathogen identifications.

Investigation Flowchart: Diagnose bioinformatics issues with this pathway.

Detailed Corrective Actions:

- Re-trim Raw Reads: Use tools like Fastp to remove low-quality bases, adapter sequences, and short reads. Inadequate QC can lead to inaccurate alignment and variant calling, undermining all downstream analysis [38] [41].

- Optimize Alignment Parameters: Fine-tune the settings of aligners like BWA to achieve an optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity. Avoid using only default settings, as the ideal parameters can depend on the genome size, read length, and experimental design [41] [42].