Next-Generation Cheminformatics: AI-Powered ADMET Prediction for Smarter Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern cheminformatics tools and artificial intelligence (AI) models for predicting Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties.

Next-Generation Cheminformatics: AI-Powered ADMET Prediction for Smarter Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern cheminformatics tools and artificial intelligence (AI) models for predicting Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the evolution from traditional methods to advanced machine learning, including practical guidance on algorithm selection, feature engineering, and platform usage. The content further addresses critical challenges like data quality and model interpretability, explores validation strategies for industrial application, and concludes with future directions, offering a holistic resource to reduce late-stage attrition and accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapeutics.

The ADMET Challenge: Why Predicting Drug Behavior is Critical for Success

The high failure rate of drug candidates in clinical development represents one of the most significant challenges in pharmaceutical research and development. Analyses of clinical trial data reveal that 90% of drug candidates that enter clinical trials ultimately fail, with 40-50% failing due to lack of clinical efficacy and approximately 30% failing due to unmanageable toxicity [1]. These staggering statistics highlight the critical importance of early assessment of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties in the drug discovery pipeline.

The financial implications of this high attrition rate are profound, with the average cost to bring a new drug to market reaching $2.6 billion and the process typically requiring 10-15 years [2]. Furthermore, each day a drug spends in development represents approximately $37,000 in direct costs and $1.1 million in opportunity costs due to lost revenue [3]. This economic reality has driven the pharmaceutical industry to adopt a "fail early, fail cheap" strategy, with computational ADMET prediction emerging as a transformative approach to identify problematic candidates before substantial resources are invested [4].

This Application Note examines how ADMET problems drive drug attrition and provides detailed protocols for integrating computational ADMET prediction into early-stage drug discovery workflows, framed within the broader context of chemoinformatics tools for predicting ADMET properties.

The ADMET Attrition Landscape

Quantitative Analysis of Drug Failure Reasons

Table 1: Reasons for clinical drug development failure based on analysis of 2010-2017 clinical trial data [1]

| Failure Reason | Percentage | Primary Contributing ADMET Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Clinical Efficacy | 40-50% | Poor tissue exposure/selectivity, inadequate bioavailability, insufficient target engagement |

| Unmanageable Toxicity | 30% | Off-target binding, reactive metabolite formation, tissue accumulation |

| Poor Drug-like Properties | 10-15% | Low solubility, poor permeability, metabolic instability |

| Commercial/Strategic Factors | ~10% | Not applicable |

The structure–tissue exposure/selectivity–activity relationship (STAR) framework provides a valuable approach for classifying drug candidates based on their potential for clinical success [1]. This framework emphasizes that tissue exposure and selectivity are as critical as potency and specificity, which have been traditionally overemphasized in drug optimization campaigns.

- Class I Drugs: High specificity/potency and high tissue exposure/selectivity; requires low dose to achieve superior clinical efficacy/safety with high success rate

- Class II Drugs: High specificity/potency but low tissue exposure/selectivity; requires high dose to achieve clinical efficacy with high toxicity

- Class III Drugs: Relatively low specificity/potency but high tissue exposure/selectivity; requires low dose to achieve clinical efficacy with manageable toxicity

- Class IV Drugs: Low specificity/potency and low tissue exposure/selectivity; achieves inadequate efficacy/safety and should be terminated early

Historical Impact of ADMET Optimization

The implementation of early ADMET screening has already demonstrated significant impact on drug failure profiles. In 1993, 40% of drugs failed in clinical trials due to pharmacokinetics and bioavailability problems. By the late 1990s, after the widespread adoption of early ADMET assessment, this figure had dropped to approximately 11% [3]. This dramatic improvement underscores the value of integrating ADMET evaluation early in the discovery process.

Computational ADMET Prediction Frameworks

Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative technology for ADMET prediction, revolutionizing early-stage drug discovery by enhancing accuracy, reducing experimental burden, and accelerating decision-making [5]. ML-based models have demonstrated significant promise in predicting key ADMET endpoints, frequently outperforming traditional quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models [5].

Table 2: Machine learning approaches for ADMET prediction [5] [6]

| ML Approach | Key Strengths | Representative Applications | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Directly learns from molecular structure; captures complex spatial relationships | Solubility prediction, toxicity assessment | High accuracy with sufficient data; requires careful hyperparameter tuning |

| Ensemble Methods (Random Forest, etc.) | Robust to noise; provides feature importance; handles diverse data types | Metabolic stability, CYP inhibition | Generally strong performance; less prone to overfitting |

| Multitask Learning | Leverages correlations between related properties; improved generalization | Simultaneous prediction of multiple ADMET endpoints | Reduces data requirements for individual endpoints |

| Deep Learning Architectures | Automates feature engineering; models complex nonlinear relationships | PBPK modeling, clearance prediction | Requires large datasets; computationally intensive |

Molecular Modeling Techniques

Molecular modeling represents a complementary approach to data-driven ML methods, incorporating structural information of ADMET-related proteins [4].

- Ligand-Based Methods: Include pharmacophore modeling and shape-focused approaches that derive information on protein active sites based on known ligands

- Structure-Based Methods: Utilize molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations to predict interactions between compounds and ADMET-related proteins

- Quantum Mechanical (QM) Calculations: Provide accurate description of electrons in atoms and molecules; particularly valuable for predicting metabolic transformations

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Consensus-Based ADMET Screening for Lead Optimization

This protocol describes a comprehensive approach for evaluating Druglikeness and ADMET properties using a consensus of computational platforms, adapting methodology from recent research on tyrosine kinase inhibitors [7].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research reagent solutions for computational ADMET screening

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Druglikeness Screening | Molsoft Druglikeness, SwissADME, Molinspiration | Assess compliance with rule-based criteria (Lipinski, Veber, etc.) | Web-based services |

| Physicochemical Property Prediction | SwissADME, admetSAR 3.0, ADMETlab 3.0 | Calculate molecular weight, LogP, TPSA, H-bond donors/acceptors | Freely accessible web servers |

| ADME Property Prediction | ADMETlab 3.0, pkSCM, PreADMET, Deep-PK | Predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion parameters | Mixed free and commercial |

| Toxicity Prediction | admetSAR 3.0, T.E.S.T, ADMETlab 3.0 | Assess mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, organ toxicity | Freely accessible |

| Validation Databases | PharmaBench, ChEMBL, DrugBank | Provide experimental data for model validation | Publicly available |

Procedure

Step 1: Compound Selection and Preparation

- Select promising compounds based on primary activity (e.g., IC50, Ki)

- Prepare molecular structures in standardized format (SMILES recommended)

- Perform structural curation: neutralize salts, remove duplicates, standardize representation

Step 2: Multi-Platform Druglikeness Assessment

- Submit compounds to multiple druglikeness screening tools (minimum of 3 platforms)

- Evaluate compliance with established rules: Lipinski, Ghose, Veber, Egan

- Calculate Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness (QED) where available

- Identify compounds passing ≥80% of applied rules

Step 3: Consensus ADMET Property Prediction

- For each compound, collect predictions from multiple platforms for key properties:

- Absorption: Caco-2 permeability, HIA, P-gp substrate/inhibition

- Distribution: Plasma protein binding, volume of distribution, blood-brain barrier penetration

- Metabolism: CYP450 inhibition/substrate status for major isoforms (3A4, 2D6, 2C9, 2C19, 1A2)

- Excretion: Total clearance

- Toxicity: Ames mutagenicity, hERG inhibition, hepatotoxicity, carcinogenicity

- Apply scoring system (e.g., 0-1 scale) for each property based on desirability

- Calculate composite ADMET score as weighted average of individual properties

Step 4: Data Integration and Compound Classification

- Integrate results from all platforms, giving preference to consensus predictions

- Classify compounds using STAR framework based on potency, tissue exposure/selectivity

- Prioritize Class I and III compounds for further development

- Terminate Class IV compounds early

Step 5: Validation and Model Refinement

- Compare computational predictions with available experimental data

- Refine models based on validation results

- Establish confidence intervals for key physicochemical properties of successful compounds

Troubleshooting

- Inconsistent predictions between platforms: Favor consensus predictions or those from tools with validated performance for specific endpoints [8]

- Limited experimental validation data: Utilize public databases (e.g., PharmaBench, ChEMBL) to expand validation sets [9]

- Compounds outside applicability domain: Flag predictions for compounds structurally distinct from training data

Protocol 2: Development of Robust QSAR Models for ADMET Endpoints

This protocol provides methodology for building and validating QSAR models for specific ADMET properties, based on comprehensive benchmarking studies [8].

Materials and Reagents

- Software: OPERA, RDKit, or other QSAR modeling environments

- Datasets: Curated ADMET datasets from PharmaBench, ChEMBL, or literature sources

- Descriptors: 2D molecular descriptors, ECFP fingerprints, estate indices

- Modeling Algorithms: Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, Neural Networks

Procedure

Step 1: Data Collection and Curation

- Identify relevant experimental datasets from public databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem)

- Apply rigorous curation: standardize structures, identify and handle duplicates, remove outliers

- Address experimental condition variability using multi-agent LLM systems where necessary [9]

Step 2: Chemical Space Analysis

- Compare dataset chemical space with reference chemical space (drugs, industrial chemicals, natural products)

- Ensure representative coverage of relevant chemical classes

- Apply principal component analysis using molecular fingerprints to visualize chemical space

Step 3: Model Training with Applicability Domain Assessment

- Split data into training/test sets using random and scaffold splitting

- Train multiple algorithm types (RF, SVM, etc.) with different descriptor sets

- Implement applicability domain assessment using leverage and vicinity methods

- Optimize hyperparameters using cross-validation

Step 4: Model Validation and Benchmarking

- Evaluate model performance on external validation sets

- Compare performance with existing tools and benchmarks

- Assess performance for specific chemical classes and within applicability domain

Step 5: Model Interpretation and Implementation

- Identify most important molecular descriptors for predictive outcomes

- Develop user-friendly implementation for high-throughput screening

- Establish protocols for regular model updating and maintenance

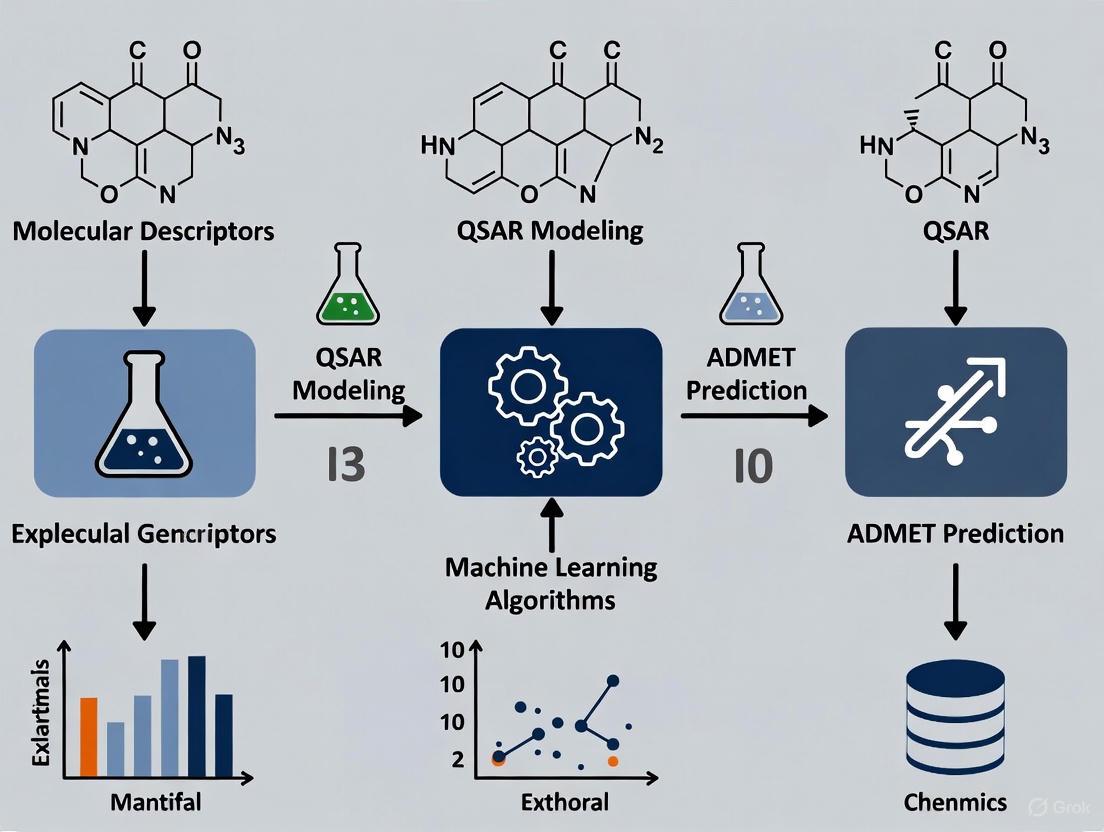

Visualization of ADMET Prediction Workflows

ADMET Failure and Computational Solution Pathway

Diagram 1: ADMET failure and computational solution pathway illustrating how ADMET problems drive clinical attrition and computational approaches provide early risk assessment.

Computational ADMET Benchmarking Workflow

Diagram 2: Computational ADMET benchmarking workflow showing comprehensive process from data collection to implementation in drug discovery pipeline.

ADMET problems remain a primary driver of drug attrition, contributing to the overwhelming 90% failure rate in clinical drug development. The implementation of computational ADMET prediction strategies, including machine learning models, QSAR approaches, and consensus-based screening methods, provides a powerful framework for identifying high-risk candidates early in the discovery process. The protocols outlined in this Application Note offer practical methodologies for integrating these approaches into drug discovery workflows, potentially reducing late-stage failures and improving the efficiency of pharmaceutical R&D.

As computational methods continue to evolve, with advances in graph neural networks, multitask learning, and large-scale benchmarking datasets, the accuracy and applicability of ADMET prediction will further improve. This progression promises to transform drug discovery from a high-attrition process to a more predictable, efficient endeavor, ultimately delivering safer and more effective therapeutics to patients in a more timely and cost-effective manner.

The evolution of cheminformatics from its origins reliant on hand-crafted rules to the current era of high-throughput, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven prediction represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery. This transformation is acutely evident in the prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties, where computational models have progressed from simple heuristic filters to sophisticated machine learning (ML) systems. These systems are now capable of navigating the complex multi-parameter optimization required to reduce the high attrition rates in late-stage drug development [10] [11]. This application note details the key stages of this evolution, provides a protocol for benchmarking modern ADMET prediction tools, and visualizes the workflow integrating these advanced methodologies into the drug discovery pipeline.

The Evolutionary Journey: From Rules to AI

The methodologies for in silico ADMET prediction have advanced through several distinct phases, each marked by increasing computational power and data availability.

The Era of Hand-Crafted Rules and Simple Descriptors

The initial phase was dominated by expert-derived rules and simple quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models. The most famous example, the Rule of 5, served as an early computational filter for absorption liability. It flagged compounds with excessive lipophilicity (MLogP > 4.15), large molecular weight (MWt > 500), too many hydrogen bond donors (HBDH > 5), or too many hydrogen bond acceptors (M_NO > 10) [12]. While revolutionary for its time, this approach was limited to identifying potential issues without providing quantitative predictions for a broad range of endpoints.

The Rise of Machine Learning on Public Data

The advent of machine learning algorithms, including Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forests (RF), applied to larger, publicly available datasets marked a significant leap forward [13] [10]. These models used various molecular representations, such as RDKit descriptors and Morgan fingerprints, to build predictive models for properties like intestinal absorption, aqueous solubility, and cytochrome P450 interactions [13]. However, reliance on public data introduced limitations, including publication bias, data heterogeneity from different laboratories, and insufficient coverage of relevant chemical space [14].

The Current Paradigm: High-Throughput AI and Diverse Data

The current state-of-the-art leverages deep learning (DL), graph neural networks (GNNs), and multitask learning on expansive, high-quality datasets [15]. The focus has shifted from algorithm development to data quality and diversity. Key developments include:

- Proprietary Models: Training models on high-quality, consistent internal experimental data, which provides higher accuracy and relevance for specific therapeutic areas [14].

- Federated Learning: Enabling multiple pharmaceutical organizations to collaboratively train models on distributed proprietary datasets without sharing sensitive data, dramatically expanding the chemical space covered and improving model robustness [11].

- Large-Scale Benchmarking: Initiatives like PharmaBench use large language models (LLMs) to systematically curate massive, consistent datasets from public sources, addressing previous issues of scale and variability [9].

Table 1: Evolution of Key Paradigms in Cheminformatics for ADMET Prediction

| Era | Core Methodology | Example Tools/Techniques | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand-Crafted Rules | Heuristic filters based on molecular properties | Rule of 5, ADMET Risk [12] | Simple, interpretable, fast | Qualitative; limited scope; no quantitative prediction |

| Machine Learning on Public Data | QSAR, SVM, Random Forests [13] [10] | RDKit descriptors, Morgan fingerprints [13] | Quantitative predictions; handles complex relationships | Limited by public data quality and heterogeneity |

| High-Throughput AI & Diverse Data | Deep Learning, GNNs, Federated Learning [15] [11] | Proprietary models (e.g., AIDDISON), Federated networks [11] [14] | High accuracy; broad applicability domain; data privacy | Complex "black box" models; requires significant data infrastructure |

Application Note: Benchmarking ADMET Prediction Tools

Background and Objective

With dozens of computational tools available, selecting the optimal one for a specific ADMET endpoint is challenging. A recent comprehensive study benchmarked twelve software tools implementing QSAR models for 17 physicochemical (PC) and toxicokinetic (TK) properties using 41 rigorously curated validation datasets [16]. The objective of this application note is to summarize the findings and provide a protocol for researchers to conduct their own rigorous tool evaluations.

The external validation study emphasized the performance of models inside their applicability domain. Overall, models for PC properties generally outperformed those for TK properties.

Table 2: Summary of Software Performance for Key ADMET Properties (Adapted from [16])

| Property | Category | Performance Metric | Representative High-Performing Tools / Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| LogP/LogD | Physicochemical | R² Average = 0.717 (PC) | Several tools demonstrated robust predictivity. |

| Water Solubility | Physicochemical | R² Average = 0.717 (PC) | Models showed strong performance in external validation. |

| Caco-2 Permeability | Toxicokinetic | R² Average = 0.639 (Regression) | Predictive performance varied; top tools were identified. |

| Fraction Unbound (FUB) | Toxicokinetic | R² Average = 0.639 (Regression) | Predictive performance varied; top tools were identified. |

| Bioavailability (F30%) | Toxicokinetic | Balanced Accuracy = 0.780 (Classification) | Predictive performance varied; top tools were identified. |

| P-gp Substrate/Inhibitor | Toxicokinetic | Balanced Accuracy = 0.780 (Classification) | Models for categorical endpoints showed good accuracy. |

Experimental Protocol: A Rigorous Workflow for Model Evaluation

This protocol outlines a structured approach for evaluating and optimizing machine learning models for ADMET prediction, incorporating best practices from recent literature [13] [16].

Data Curation and Standardization

Function: To create a clean, consistent, and reliable dataset for model training and testing. Procedure:

- Standardize Structures: Use a tool like the RDKit Python package to canonicalize SMILES strings, neutralize salts, adjust tautomers, and remove inorganic/organometallic compounds [13] [16].

- Remove Inconsistencies:

- Filter Outliers: Calculate the Z-score for each data point and remove compounds with a Z-score >3 (intra-outliers). For inter-outliers (same compound across datasets), apply the same duplicate criteria and remove inconsistent entries [16].

Feature Selection and Model Training

Function: To systematically identify the most informative molecular representation and train a predictive model. Procedure:

- Feature Generation: Calculate a diverse set of molecular features for the curated dataset. This should include:

- Iterative Feature Combination: Iteratively combine different feature sets (e.g., start with descriptors, then add fingerprints) and evaluate model performance to identify the best-performing representation combination [13].

- Model Training with Cross-Validation: Train a suite of ML models (e.g., Random Forest, LightGBM, SVM, MPNN) using a scaffold split to ensure the training and test sets contain distinct molecular scaffolds. Perform hyperparameter tuning in a dataset-specific manner [13].

Statistical Evaluation and Hypothesis Testing

Function: To robustly compare models and ensure performance improvements are statistically significant. Procedure:

- Performance Metrics: Calculate appropriate metrics (e.g., R² for regression, Balanced Accuracy for classification) across all cross-validation folds.

- Hypothesis Testing: Apply statistical hypothesis tests (e.g., paired t-test) to the distributions of performance metrics from different models or feature sets. This adds a layer of reliability beyond simple average performance comparison [13].

- Hold-out Test Evaluation: Evaluate the final optimized model on a completely held-out test set to assess its generalizability [13].

Practical Validation and External Generalization

Function: To assess model performance in a real-world scenario, mimicking the use of external data. Procedure:

- External Dataset Validation: Take a model trained on one data source (e.g., a public dataset) and evaluate it on a test set from a different source (e.g., an in-house assay) for the same property [13].

- Data Combination Test: Train the optimized model on a combination of data from two different sources to evaluate the impact of augmenting internal data with external sources [13].

Diagram 1: A rigorous workflow for evaluating and optimizing ADMET prediction models, from data curation to practical validation.

Modern cheminformatics relies on a suite of software tools, data resources, and computational frameworks.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Modern Cheminformatics Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to ADMET Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Generation of molecular descriptors and fingerprints [13] [16] | Creates essential feature representations for QSAR and ML models. |

| PharmaBench | Benchmark Dataset | Curated, large-scale ADMET data for model training and testing [9] | Provides a robust standard for evaluating model performance on relevant chemical space. |

| ADMET Predictor | Commercial Software | Platform for predicting over 175 ADMET properties [12] | Offers state-of-the-art, ready-to-use models and serves as a benchmark in studies. |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Data Resource | Aggregated public datasets for machine learning [13] | A starting point for accessing a variety of public ADMET datasets. |

| Federated Learning Platform (e.g., Apheris) | Computational Framework | Enables collaborative training on distributed private data [11] | Allows building more robust models without sharing proprietary data, expanding the applicability domain. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Algorithm | Learns directly from molecular graph structures [15] | Powerful deep learning approach for molecular property prediction that captures structural information. |

The journey of cheminformatics from hand-crafted rules to high-throughput AI has fundamentally enhanced our ability to predict critical ADMET properties early in drug discovery. The current paradigm, emphasizing data quality, diversity, and rigorous evaluation, is yielding models with greater predictive power and broader applicability. By adopting structured protocols for benchmarking and leveraging new approaches like federated learning, researchers can continue to accelerate the development of safer and more effective therapeutics.

In modern drug discovery, the journey from a theoretical compound to a marketed therapeutic is paved with stringent evaluations that extend beyond mere biological potency. A potent molecule must successfully navigate the complex biological system of the human body to reach its target site in sufficient concentration, remain there long enough to exert its therapeutic effect, and do so without causing harm. This comprehensive profile is captured by three interconnected concepts: drug-likeness, lead-likeness, and ADMET parameters. Framed within chemoinformatics research, this application note details the core definitions, quantitative benchmarks, and standard computational protocols for evaluating these essential characteristics, providing scientists with a structured framework to prioritize compounds with the highest probability of clinical success [17] [18].

Core Conceptual Definitions

Drug-likeness

Drug-likeness is a qualitative concept used in drug design to estimate the probability that a molecule possesses the physicochemical and structural characteristics commonly found in successful oral drugs, with a primary focus on good bioavailability [19]. It is grounded in the retrospective analysis of known drugs, aiming to define a favorable chemical space for new chemical entities. The concept does not evaluate specific biological activity but rather the inherent physicochemical properties that enable a compound to be effectively administered, absorbed, and distributed within the body [19] [17].

Lead-likeness

Lead-likeness is a tactical refinement of the drug-likeness concept. It serves as a guide for selecting optimal starting points for chemical optimization, rather than final drug candidates. A "lead" compound is typically of lower molecular weight and complexity than a drug, possessing clear, demonstrable but modifiable activity against a therapeutic target. This provides the necessary chemical space for medicinal chemists to optimize for both potency and ADMET properties during the development process, thereby increasing the likelihood of delivering a viable "drug-like" candidate at the end of the program [20].

ADMET Parameters

ADMET is an acronym that encompasses the key pharmacokinetic and safety profiles of a compound in vivo:

- Absorption: The process by a compound enters the systemic circulation from its site of administration (e.g., the gastrointestinal tract).

- Distribution: The reversible transfer of a compound between the blood and various tissues and organs of the body.

- Metabolism: The enzymatic modification of a compound, primarily in the liver, which can lead to its inactivation or, in some cases, activation.

- Excretion: The removal of the parent compound and its metabolites from the body.

- Toxicity: The potential of a compound to cause harmful or adverse effects [6] [17].

Suboptimal ADMET properties are a major cause of failure in late-stage clinical development; therefore, their early assessment is critical for de-risking drug discovery pipelines [6].

Quantitative Property Ranges and Benchmarks

Property Ranges for Drug-likeness and Lead-likeness

Table 1: Comparative Ranges for Key Physicochemical Properties

| Property | Drug-like Ranges | Lead-like Ranges | Primary Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight (MW) | 200 - 600 Da [19]; <500 Da [17] | Lower than Drug-like [20] | Impacts membrane permeability and solubility; lower MW allows for optimization growth [19] [20]. |

| logP (Lipophilicity) | logP ≤ 5 [17]; -0.4 to 5.6 [19] | Lower than Drug-like [20] | Balances solubility in aqueous (blood) and lipid (membrane) phases; high logP linked to poor solubility and promiscuity [19]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD) | ≤ 5 [17] | Information Missing | Influences solubility and permeability; excessive HBDs can impair membrane crossing [19] [17]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) | ≤ 10 [17] | Information Missing | Impacts solubility and permeability [19] [17]. |

| Molar Refractivity (MR) | 40 - 130 [19] | Information Missing | Related to molecular volume and weight [19]. |

| Number of Atoms | 20 - 70 [19] | Information Missing | Correlates with molecular size and complexity [19]. |

Key ADMET Property Benchmarks

Table 2: Critical ADMET Properties and Their Favorable Ranges

| ADMET Category | Specific Property | Favorable Range / Outcome | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Caco-2 Permeability | High | Predicts effective intestinal absorption [6]. |

| P-glycoprotein (P-gp) Substrate | Non-substrate | Avoids active efflux, which can limit absorption and brain penetration [6]. | |

| Distribution | Plasma Protein Binding (PPB) | Not excessively high | High PPB can limit tissue distribution and free concentration for activity [6]. |

| Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Penetration | As required by target | For CNS targets, penetration is key; for peripheral targets, avoidance is safer [21]. | |

| Metabolism | Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Inhibition | Non-inhibitor | Avoids drug-drug interactions [6] [21]. |

| CYP Substrate (e.g., 3A4) | Metabolically stable | Ensures adequate half-life and reduces first-pass metabolism [6]. | |

| Excretion | Total Clearance | Low to Moderate | Prevents rapid elimination from the body [6]. |

| Toxicity | hERG Channel Inhibition | Non-inhibitor | Avoids cardiotoxicity risk (QTc prolongation) [21]. |

| Ames Test | Negative | Indicates low mutagenic potential [12]. | |

| Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI) | Low risk | Cruggle for patient safety and compound attrition [12] [21]. |

Experimental Protocols for In Silico Evaluation

Protocol 1: Rapid Drug-likeness Screening using Rule-Based Filters

Purpose: To quickly triage large virtual compound libraries and identify molecules with basic drug-like properties suitable for oral administration. Principle: This protocol applies a set of heuristic rules derived from statistical analysis of known drugs, such as the widely used Lipinski's Rule of Five [17].

Materials:

- Input: A library of compounds in SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) or SDF (Structure-Data File) format.

- Software: Cheminformatics toolkits (e.g., RDKit, OpenBabel) or online platforms like SwissADME [18].

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Standardize molecular structures. For salts, extract the neutral parent compound. Generate canonical SMILES [13].

- Descriptor Calculation: For each molecule, compute the following key physicochemical properties:

- Molecular Weight (MW)

- Octanol-water partition coefficient (logP)

- Number of Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD)

- Number of Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA)

- Rule Application: Apply the "Rule of Five" filter. A molecule is considered to have a high risk of poor absorption if it violates two or more of the following conditions:

- MW ≤ 500

- logP ≤ 5

- HBD ≤ 5

- HBA ≤ 10

- Result Interpretation: Compounds with 0 or 1 violation are prioritized for further analysis. Those with 2 or more violations are typically deprioritized, though notable exceptions exist (e.g., natural products, substrates for transporters) [19] [17].

Protocol 2: Comprehensive ADMET Profiling using Machine Learning Platforms

Purpose: To obtain a multi-parameter, quantitative prediction of critical ADMET endpoints for a focused set of lead compounds. Principle: This protocol leverages state-of-the-art machine learning (ML) models, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and ensemble methods, trained on large-scale experimental datasets to predict complex ADMET properties with high accuracy [6] [22].

Materials:

- Input: A focused library of compounds (typically 100 - 10,000) in SMILES or SDF format.

- Software: Web-based platforms such as ADMETlab 3.0 [22], ADMET-AI [23], or commercial software like ADMET Predictor [12].

Procedure:

- Platform Selection & Input: Choose an ADMET prediction platform. Prepare and upload a file containing the SMILES strings of the compounds to be evaluated.

- Endpoint Selection: Select the desired ADMET endpoints for prediction. A standard panel includes:

- Physicochemical: Water solubility (LogS), pKa, logD.

- Absorption: Caco-2 permeability, P-gp substrate/inhibition, Human Intestinal Absorption (HIA).

- Distribution: PPB, VDss, BBB penetration.

- Metabolism: CYP inhibition (1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4), CYP substrate, microsomal/hepatocyte clearance.

- Toxicity: hERG inhibition, Ames mutagenicity, DILI risk, skin sensitization.

- Model Execution: Run the prediction job. The platform will process the molecules using its underlying ML models (e.g., DMPNN for ADMETlab 3.0, Chemprop-RDKit for ADMET-AI) [22] [23].

- Result Analysis and Interpretation:

- Review results in interactive tables and plots (e.g., radial plots for key properties).

- Use the platform's reference data (e.g., comparison to known drugs in DrugBank) to contextualize predictions [23].

- Pay attention to model confidence indicators or uncertainty estimates, which flag predictions that may be less reliable [22].

- Integrate the ADMET profile with potency data to make informed lead optimization or selection decisions.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Conceptual Relationship and Screening Workflow

Figure 1: A sequential workflow for compound screening and optimization, illustrating the progression from initial drug-likeness filtering through lead optimization and detailed ADMET profiling.

The Bioavailability Radar

Figure 2: The Bioavailability Radar conceptualizes six key physicochemical properties that define drug-likeness. A compound's profile must fall entirely within the pink zone to be considered optimally drug-like [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Predicting Drug-likeness and ADMET Properties

| Tool Name | Type/Availability | Key Features | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| SwissADME [18] | Free Web Tool | Computes physicochemical descriptors, drug-likeness rules (e.g., Lipinski), and key PK parameters like bioavailability radar and BOILED-Egg. | Rapid, single-compound or small-batch evaluation for early-stage discovery. |

| ADMETlab 3.0 [22] | Free Web Tool | Predicts 119 ADMET endpoints using a Directed Message Passing Neural Network (DMPNN). Includes uncertainty evaluation. | Comprehensive ADMET profiling for a batch of designed compounds prior to synthesis. |

| ADMET-AI [23] | Free Web Tool / CLI | Fast predictions for 41 ADMET properties using a Chemprop-RDKit model. Benchmarks predictions against DrugBank compounds. | High-throughput screening of large virtual libraries, with contextual results. |

| ADMET Predictor [12] | Commercial Software | Industry-standard platform predicting over 175 properties. Includes PBPK modeling, metabolism simulation, and an "ADMET Risk" score. | Enterprise-level, deep ADMET analysis and modeling for lead optimization in pharma. |

| Chemprop [13] | Open-Source Python Package | A message-passing neural network for molecular property prediction. Highly flexible for building custom models. | For research groups developing and training their own tailored ADMET models. |

Within the framework of chemoinformatics tools for predicting Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties, public databases and resources serve as the foundational bedrock. The ability to predict these properties computationally is crucial in drug discovery to mitigate late-stage failures due to unfavorable pharmacokinetics or toxicity [24]. This application note provides a detailed overview of key public databases, structured protocols for their use, and visual guides to integrate these resources into a robust chemoinformatics workflow, empowering researchers to make data-driven decisions in early-stage drug development.

A number of public databases provide curated ADMET-associated data for research. The selection below includes established and community-benchmarked resources essential for model training and validation.

Table 1: Key Public Databases and Resources for ADMET Data

| Database/Resource Name | Primary Focus & Description | Key ADMET Endpoints Covered | Data Scale (Unique Compounds/Data Points) | Accessibility & Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) [25] | A comprehensive benchmark platform for machine learning in drug discovery. | 22 ADMET datasets across Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity [25]. | Varies by dataset (e.g., ~578 to ~13,130 compounds per endpoint) [25]. | Free access; Provides curated train/validation/test splits (e.g., scaffold split); Performance leaderboards. |

| admetSAR [26] | An open-source, structure-searchable database for ADMET property prediction and optimization. | 45 kinds of ADMET-associated properties, including toxicity, metabolism, and permeability [26]. | Over 210,000 ADMET annotated data points for >96,000 unique compounds [26]. | Free web service; Provides predictive models for 47 endpoints (as of version 2.0); Data from published literature. |

| OpenADMET [27] | An open science initiative combining high-throughput experimentation, computation, and structural biology. | Focus on "avoidome" targets (e.g., hERG, CYP450s) to avoid adverse effects [27]. | Data generation and blind challenges are ongoing (e.g., a 2025 challenge with 560 datapoints) [28]. | Community-driven; Hosts blind prediction challenges; Aims to provide high-quality, consistently generated assay data. |

| Antiviral ADMET Challenge 2025 (ASAP Discovery x OpenADMET) [28] | A specific blind challenge dataset for predicting ADMET properties of antiviral compounds. | 5 key endpoints: Metabolic stability (MLM, HLM), Solubility (KSOL), Lipophilicity (LogD), Permeability (MDR1-MDCKII) [28]. | 560 data points (with sparse measurement across assays) [28]. | Publicly available unblinded dataset; Represents a real-world, sparse data scenario for model testing. |

Access and Utilization Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Data Retrieval from TDC for Benchmarking

This protocol outlines the steps to retrieve a benchmark ADMET dataset from TDC, which is critical for training and evaluating machine learning models.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Software Environment: A Python 3.7+ environment.

- Key Python Package:

tdcpackage (install viapip install PyTDC). - Supporting Libraries: Standard data science libraries (e.g.,

pandas,scikit-learn).

Procedure:

- Installation and Import: Install the TDC package and import necessary modules in your Python environment.

Retrieve Benchmark Names: Identify the available ADMET benchmarks within the group.

Load a Specific Dataset: Select and load a dataset of interest, such as the Caco-2 permeability dataset. The get method automatically returns the data partitioned into training/validation and test sets using a scaffold split, which groups molecules by their core structure to assess model generalization to novel chemotypes [25].

Model Training and Evaluation: Train your model on the train_val set. Generate predictions (y_pred) on the test set and use TDC's built-in evaluator for a standardized performance assessment.

Protocol 2: Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering for ADMET Modeling

High-quality inputs are paramount for reliable model performance. This protocol details a data cleaning and feature extraction workflow, drawing on best practices from recent benchmarking studies [13].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cheminformatics Library: RDKit.

- Standardization Tool: The standardisation tool by Atkinson et al. [13].

- Data Visualization: DataWarrior for visual inspection [13].

Procedure:

- Remove Inorganics and Extract Parent Compounds: Filter out inorganic salts and organometallic compounds. For compounds in salt form, extract the neutral, parent organic structure for consistent representation [13].

- Standardize Molecular Representation: Use a standardization tool to normalize SMILES strings. This includes adjusting tautomers to a consistent representation and canonicalizing the SMILES [13].

- Deduplication: Identify duplicate molecular structures. If duplicates have consistent target values (identical for classification, within a tight range for regression), keep the first entry. Remove the entire group of duplicates if their target values are inconsistent [13].

- Feature Extraction: Compute molecular descriptors and fingerprints. RDKit is a standard tool for this task.

- Data Splitting: For final model training and evaluation, use a scaffold split to ensure that structurally dissimilar molecules are used for training and testing, providing a more realistic assessment of a model's predictive power on novel chemotypes [25] [13].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for utilizing public ADMET data, from data acquisition to model deployment in a drug discovery pipeline.

ADMET Prediction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Software and Computational Tools for ADMET Predictions

Item Name

Function / Application

Key Features / Notes

RDKit

Open-source cheminformatics toolkit.

Used for molecule manipulation, descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation (e.g., Morgan fingerprints), and scaffold-based splitting [13].

Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC)

A one-stop benchmark platform for machine learning in drug discovery.

Provides pre-processed, curated ADMET datasets with standardized splits and evaluation metrics, enabling fair model comparison [25].

Chemprop

A deep learning library for molecular property prediction.

Implements Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) that directly learn from molecular graphs; often a top performer in benchmark studies [13].

Scikit-learn

A core library for classical machine learning in Python.

Provides implementations of algorithms like Random Forests and Support Vector Machines, and tools for model evaluation and hyperparameter tuning [13].

admetSAR Web Service

A free online platform for ADMET prediction.

Allows for quick, single-molecule or batch predictions using built-in models without requiring local installation or model training [26].

AI and Machine Learning in Action: Building and Applying ADMET Models

Molecular representation learning serves as the foundational step in computer-aided drug design, bridging the gap between chemical structures and their biological activities [29]. The transformation of molecules into computer-readable formats enables machine learning and deep learning models to predict crucial Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties early in the drug discovery pipeline [29]. As the pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to reduce development costs and attrition rates, accurate in silico prediction of ADMET properties has become indispensable for prioritizing viable drug candidates [30] [31]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of current molecular representation methodologies, their performance benchmarks in ADMET prediction, and detailed experimental protocols for their implementation.

Molecular Representation Fundamentals

Definition and Significance

Molecular representation involves converting chemical structures into mathematical or computational formats that algorithms can process to model, analyze, and predict molecular behavior [29]. Effective representation is crucial for various drug discovery tasks, including virtual screening, activity prediction, and scaffold hopping, enabling efficient navigation of chemical space [29]. The choice of representation significantly impacts the accuracy and generalizability of learning algorithms applied to chemical datasets, with different representations capturing distinct aspects of molecular structure and function [32].

The ADMET Prediction Context

ADMET properties play a determining role in a compound's viability as a drug candidate. Undesirable ADMET profiles remain a leading cause of failure in clinical development phases [30]. Experimental determination of these properties is complex and expensive, creating an urgent need for robust computational prediction methods [33] [30]. Molecular representations serve as the input features for these predictive models, with their quality directly influencing prediction reliability [13].

Classification of Molecular Representations

Traditional Molecular Representations

Traditional representation methods rely on explicit, rule-based feature extraction and have established a strong foundation for computational approaches in drug discovery [29].

Molecular Descriptors encompass quantified physical or chemical properties of molecules, ranging from simple count-based statistics (e.g., atom counts) to complex measures including quantum mechanical properties [32]. RDKit descriptors represent a widely implemented example.

Molecular Fingerprints encode substructural information as binary strings or numerical values [29]. These can be further categorized into:

- Substructure Key Fingerprints (e.g., MACCS keys) encode specific chemical substructures using predefined structural fragments [33] [32].

- Circular Fingerprints (e.g., Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints - ECFP) capture molecular features based on atom connectivity within increasingly larger radii [33] [32].

- Path-Based Fingerprints (e.g., Topological fingerprints) enumerate all possible paths between atoms in a molecule [33].

- Pharmacophore Fingerprints incorporate information about the spatial orientation and interactions of a molecule [32].

Table 1: Classification of Traditional Molecular Representations

| Representation Type | Key Examples | Underlying Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | RDKit Descriptors, alvaDesc | Quantification of physico-chemical properties | Physically interpretable, computationally efficient | May not capture complex structural patterns |

| Structural Key Fingerprints | MACCS, PUBCHEM | Predefined dictionary of chemical substructures | High interpretability, fast similarity search | Limited to known substructures |

| Circular Fingerprints | ECFP, FCFP | Atom environments within increasing radii | Captures local structure, alignment-free | Limited stereochemistry awareness |

| Path-Based Fingerprints | Topological, DFS, ASP | Linear paths through molecular graph | Comprehensive structural coverage | Computationally intensive for large molecules |

| 3D Fingerprints | E3FP | 3D atom environments | Captures conformational information | Requires geometry optimization |

Modern Data-Driven Representations

Advanced artificial intelligence techniques have enabled a shift from predefined rules to data-driven learning paradigms [29] [32].

Language Model-Based Representations treat molecular sequences (e.g., SMILES, SELFIES) as a specialized chemical language [29]. Models such as Transformers tokenize molecular strings at the atomic or substructure level and process these tokens into continuous vector representations [29].

Graph-Based Representations conceptualize molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [30]. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) then learn representations by passing and transforming information along the molecular graph structure [30] [31]. Advanced implementations incorporate attention mechanisms and physical constraints such as SE(3) invariance for chirality awareness [31].

Multimodal and Fusion Approaches integrate multiple representation types to overcome limitations of individual formats. For example, MolP-PC combines 1D molecular fingerprints, 2D molecular graphs, and 3D geometric representations using attention-gated fusion mechanisms [34].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Representations in ADMET Prediction

| Representation Category | Specific Type | Representative Model/Approach | Key ADMET Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Fingerprints | ECFP | Random Forest | Consistently strong performance across multiple ADMET endpoints [35] [33] |

| Traditional Fingerprints | Combination (ECFP, Avalon, ErG) | CatBoost | Enhanced performance over single fingerprints [35] |

| Graph-Based | Graph Attention | Custom GNN | Effective for CYP inhibition classification; bypasses descriptor computation [30] |

| Graph-Based | Multi-task Graph Attention | ADMETLab 2.0 | State-of-the-art on multiple ADMET benchmarks [31] |

| Multimodal Fusion | 1D+2D+3D fusion | MolP-PC | Optimal performance in 27/54 ADMET tasks [34] |

| Hybrid Framework | Hypergraph-based | OmniMol | State-of-the-art in 47/52 ADMET tasks; handles imperfect annotation [31] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fingerprint-Based ADMET Prediction

This protocol outlines the procedure for developing predictive ADMET models using traditional molecular fingerprints, based on methodologies established in FP-ADMET and related studies [35] [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure Standardization | Ensures consistent molecular representation | Standardiser tools; RDKit canonicalization |

| Fingerprint Generation | Encodes molecular structure as feature vector | RDKit (ECFP, MACCS); CDK (PubChem, Avalon) |

| Machine Learning Algorithm | Builds predictive model from fingerprints | Random Forest, CatBoost, SVM |

| Model Evaluation Framework | Assesses prediction performance and generalizability | Cross-validation; external test sets; TDC benchmarks |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Curation and Preprocessing

- Collect experimental ADMET data from reliable sources such as OCHEM, ChEMBL, or TDC [33].

- Standardize molecular structures using tools like the Chemistry Development Kit (CDK) or RDKit [33]. Remove salts, neutralize charges, and generate canonical tautomers.

- Remove duplicates and compounds with inconsistent measurements. For salts, extract the organic parent compound [13].

- Apply appropriate data transformations (e.g., log-transformation for skewed distributions) [13].

Fingerprint Calculation

- Generate multiple fingerprint types for comparative analysis:

- Circular fingerprints: ECFP4 (radius=2, 1024 bits) and FCFP4

- Substructure keys: MACCS (166 bits) and PubChem fingerprints (881 bits)

- Path-based: Topological fingerprints (1024 bits) [33]

- Use established cheminformatics toolkits (RDKit, CDK) with consistent parameterization.

- Generate multiple fingerprint types for comparative analysis:

Model Training with Hyperparameter Optimization

- Implement multiple algorithms: Random Forest, CatBoost, and Support Vector Machines [35] [33].

- Split data into training (80%) and test (20%) sets using scaffold-aware splitting to ensure structural diversity [33].

- Perform five-fold cross-validation on the training set for hyperparameter tuning.

- For Random Forests, optimize the number of trees (500-1000), maximum depth, and minimum samples per leaf [33].

- Address class imbalance using techniques like SMOTE for classification tasks [33].

Model Evaluation and Validation

- Evaluate performance on the held-out test set using task-appropriate metrics:

- Regression: R², RMSE, MAE

- Classification: Balanced Accuracy, AUC-ROC, Sensitivity, Specificity [33]

- Conduct y-randomization tests to confirm model robustness [33].

- Define applicability domains using methods such as quantile regression forests (regression) or conformal prediction (classification) [33].

- Evaluate performance on the held-out test set using task-appropriate metrics:

Protocol 2: Graph Neural Network for ADMET Prediction

This protocol details the implementation of attention-based Graph Neural Networks for ADMET property prediction, based on current state-of-the-art approaches [30] [31].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Molecular Graph Construction

- Convert SMILES strings to molecular graphs where atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges [30].

- Create multiple adjacency matrices to capture different bond types: single (

A1), double (A2), triple (A3), and aromatic (A4) bonds [30]. - Construct node feature matrix incorporating atomic properties: atom type (atomic number), formal charge, hybridization, ring membership, aromaticity, and chirality [30].

Graph Neural Network Architecture

- Implement a message-passing framework where node representations are updated based on neighboring nodes [30].

- Incorporate attention mechanisms to weight the importance of different neighbors during message aggregation [30] [31].

- Use a multi-task learning approach with a shared backbone and task-specific components when predicting multiple ADMET endpoints [31].

Advanced Implementation: OmniMol Framework

- Formulate molecules and properties as a hypergraph to handle imperfectly annotated data [31].

- Implement a task-routed Mixture of Experts (t-MoE) backbone to capture correlations among properties and produce task-adaptive outputs [31].

- Integrate SE(3)-equivariant layers for chirality awareness and physical symmetry, applying equilibrium conformation supervision [31].

Training and Optimization

- Use multi-task training with a combined loss function that incorporates all available molecular-property pairs [31].

- Apply recursive geometry updates and scale-invariant message passing to facilitate learning-based conformational relaxation [31].

- Regularize using dropout and weight decay specific to the multi-task setting.

Model Interpretation

Performance Benchmarking and Practical Considerations

Quantitative Performance Insights

Recent comprehensive benchmarking studies reveal several key insights regarding molecular representation performance in ADMET prediction:

Fingerprint Combinations Enhance Performance: Gradient-boosted decision trees (particularly CatBoost) using combinations of ECFP, Avalon, and ErG fingerprints, along with molecular properties, demonstrate exceptional effectiveness in ADMET prediction [35]. Incorporating graph neural network fingerprints further enhances performance [35].

Task-Dependent Performance: No single representation universally outperforms others across all ADMET endpoints. Optimal representation selection depends on the specific property being predicted and the characteristics of the available data [36] [13].

Multi-Task Learning Advantages: Frameworks like OmniMol that leverage multi-task learning and hypergraph representations achieve state-of-the-art performance, particularly valuable when dealing with imperfectly annotated data where properties are sparsely labeled across molecules [31].

Traditional Methods Remain Competitive: Despite advances in deep learning, traditional fingerprint-based random forest models yield comparable or better performance than more complex approaches for many ADMET endpoints [33].

Practical Implementation Guidance

Data Quality Considerations Data cleanliness significantly impacts model performance. Implement rigorous standardization including salt removal, tautomer normalization, and duplicate removal with consistency checks [13]. Address skewed distributions through appropriate transformations (e.g., log-transformation) [13].

Representation Selection Strategy Begin with fingerprint-based approaches (ECFP, MACCS) for baseline models, particularly with limited data [33] [13]. Progress to graph-based representations when prediction accuracy is prioritized and sufficient data is available [30]. Consider multi-view fusion approaches for critical applications where maximal performance is required [34].

Evaluation Best Practices Incorporate cross-validation with statistical hypothesis testing for robust model comparison [13]. Use scaffold splitting to assess generalization to novel chemotypes [13]. Evaluate model performance on external datasets from different sources to test real-world applicability [13].

Molecular representations form the foundational layer of modern computational ADMET prediction, directly influencing model accuracy and interpretability. Traditional fingerprints maintain strong performance for many applications, while graph-based and multimodal approaches offer state-of-the-art capabilities for complex prediction tasks. The optimal representation strategy depends on specific project needs, data availability, and required performance levels. As molecular representation methods continue to evolve, particularly through incorporation of physical constraints and multi-task learning frameworks, their impact on accelerating drug discovery and reducing attrition rates continues to grow.

The integration of machine learning (ML) for predicting Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents a paradigm shift in computational drug discovery. This transition is largely motivated by the need to reduce the high attrition rates of drug candidates during late-stage development, with approximately 40-50% of failures attributed to unfavorable ADMET properties [10]. The application of ML spans the entire drug discovery pipeline, from initial compound screening to lead optimization, significantly enhancing the efficiency of identifying viable drug candidates by providing rapid, cost-effective, and reproducible alternatives to traditional experimental methods [37].

Early in silico models primarily relied on classical quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) approaches. However, the field has rapidly evolved to incorporate a diverse array of ML algorithms, including tree-based methods, support vector machines, and, more recently, sophisticated deep learning and graph neural network architectures [15] [37]. These modern techniques have demonstrated remarkable success in predicting key ADMET endpoints such as intestinal permeability, aqueous solubility, human intestinal absorption, plasma protein binding, metabolic stability, and toxicity, thereby enabling earlier risk assessment and more informed compound prioritization [10] [37].

Foundational Machine Learning Algorithms

Classical Machine Learning Approaches

Classical machine learning algorithms form the backbone of many robust ADMET prediction models, particularly when dealing with limited dataset sizes. These methods typically operate on fixed molecular representations such as fingerprints and descriptors.

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees during training and outputs the average prediction (for regression) or the mode of classes (for classification) of the individual trees. This bagging approach enhances predictive accuracy and controls over-fitting. In ADMET modeling, RF has been widely applied for tasks such as human intestinal absorption prediction and blood-brain barrier permeation classification [10] [37].

Support Vector Machines (SVM) represent another foundational approach, particularly effective in high-dimensional spaces. SVMs operate by finding the hyperplane that best separates different classes with the maximum margin, though they can also be adapted for regression tasks. Early applications of SVMs in ADMET prediction demonstrated their utility across a spectrum of properties, including cytochrome P450 interactions and metabolic stability [10].

Gradient Boosting Methods, including XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting), have emerged as particularly powerful algorithms for ADMET prediction. These models build ensembles of weak prediction models, typically decision trees, in a sequential manner where each new model attempts to correct the errors of the previous ones. Recent benchmarking studies have consistently shown that XGBoost delivers superior performance for various ADMET endpoints, including Caco-2 permeability prediction and metabolic stability assessment [38] [39].

Algorithm Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance comparison of machine learning algorithms across ADMET endpoints

| Algorithm | ADMET Endpoint | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | Caco-2 Permeability | Superior prediction on test sets | Generally provided better predictions than comparable models [38] |

| Random Forest | Caco-2 Permeability | Competitive performance | Robust across different molecular representations [38] |

| Boosting Models | Caco-2 Permeability | R² = 0.81, RMSE = 0.31 | Achieved better results than other methods in prior study [38] |

| XGBoost | Multiple ADME Endpoints | Top performer on 4/5 endpoints | Outperformed other tree-based models and GNNs when trained on 55 descriptors [39] |

| Deep Learning | ADME Prediction | Statistically significant improvement | Significantly outperformed traditional ML in ADME prediction [40] |

| Classical Methods | Potency Prediction | Highly competitive | Remain strong for predicting compound potency [40] |

Advanced Deep Learning Architectures

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

Graph Neural Networks represent a transformative advancement in molecular modeling by directly operating on the inherent graph structure of molecules, where atoms constitute nodes and bonds form edges [41]. This approach effectively captures the topological relationships within compounds, leading to unprecedented accuracy in ADMET property prediction [41] [37].

The Directed Message Passing Neural Network (DMPNN) architecture has demonstrated particular efficacy in ADMET applications. DMPNNs operate by passing messages along chemical bonds, with each node (atom) aggregating information from its neighbors to build increasingly sophisticated representations of molecular structure. This message-passing mechanism enables the model to learn complex chemical patterns and relationships that are difficult to capture with traditional fingerprint-based methods [38].

CombinedNet represents another innovative approach that leverages hybrid representation learning. This architecture combines Morgan fingerprints, which provide information on substructure existence, with molecular graphs that convey connectivity knowledge [38]. This multi-view representation allows the model to integrate both local and global chemical information, often resulting in enhanced predictive performance for complex ADMET endpoints.

Transformer Networks and Pretraining Strategies

Transformer architectures, originally developed for natural language processing, have been successfully adapted for molecular representation learning by treating Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings as chemical "sentences." These models can be pretrained on large, unlabeled chemical databases (such as ChEMBL) using self-supervised objectives, then fine-tuned for specific ADMET prediction tasks [39].

Recent studies have explored innovative training strategies such as gradual partial fine-tuning, where models are progressively adapted from pretrained weights to specific ADMET endpoints. This approach has demonstrated strong performance in blind challenges, achieving mean absolute error of approximately 0.79 for potency prediction tasks [39]. The ability to leverage transfer learning from large-scale chemical databases addresses the fundamental challenge of limited experimental ADMET data, particularly for novel chemical series.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Building a Classical ML Model for Caco-2 Permeability Prediction

Objective: Implement a tree-based model for predicting Caco-2 permeability using curated public datasets and molecular descriptors.

Materials and Reagents:

- Software Requirements: Python 3.7+, RDKit for descriptor calculation, Scikit-learn for machine learning algorithms, XGBoost library

- Data Sources: Public Caco-2 permeability datasets (e.g., datasets from Wang et al. [38])

- Computational Resources: Standard workstation with 8+ GB RAM

Procedure:

- Data Curation and Preparation:

- Collect experimental Caco-2 permeability values from public datasets [38]

- Convert permeability measurements to cm/s × 10–6 and apply logarithmic transformation (base 10)

- Perform molecular standardization using RDKit's MolStandardize to achieve consistent tautomer canonical states and final neutral forms while preserving stereochemistry

- Calculate mean values for duplicate entries, retaining only those with standard deviation ≤ 0.3

- Split the curated dataset into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio

Molecular Representation:

- Compute Morgan fingerprints (radius 2, 1024 bits) using RDKit implementation

- Calculate RDKit 2D descriptors using descriptastorus with normalization based on cumulative density function from Novartis' compound catalog

- Perform feature selection using correlation-based methods to identify the most predictive 55 descriptors [39]

Model Training and Optimization:

- Initialize XGBoost regressor with default parameters

- Implement 10-fold cross-validation on training set to optimize hyperparameters

- Train final model on complete training set using optimized parameters

- Validate model performance on held-out test set

Model Evaluation:

- Assess prediction accuracy using Pearson correlation coefficient, RMSE, and MAE

- Perform Y-randomization test to confirm model robustness

- Conduct applicability domain analysis to evaluate model generalizability

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Address dataset imbalance through appropriate sampling techniques

- Ensure chemical diversity in training/test splits to prevent bias

- Validate descriptor calculations against known standards

Protocol 2: Implementing Graph Neural Networks for ADMET Prediction

Objective: Develop a GNN-based model for predicting multiple ADMET endpoints using molecular graph representations.

Materials and Reagents:

- Software Requirements: PyTorch Geometric or Deep Graph Library, ChemProp package [38]

- Data Sources: ADMET datasets from public challenges (e.g., ASAP-Polaris-OpenADMET Antiviral Challenge) [40] [39]

- Computational Resources: GPU-enabled system (NVIDIA GPU with 8+ GB VRAM recommended)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Curate ADMET datasets ensuring consistent measurement units and experimental conditions

- Convert molecular structures to graph representations (G=(V,E)), where (V) represents atoms (nodes) and (E) represents bonds (edges)

- Initialize node features using atom properties (element type, hybridization, formal charge, etc.)

- Initialize edge features using bond properties (bond type, conjugation, stereochemistry, etc.)

Model Architecture Configuration:

- Implement DMPNN architecture with 6 message passing layers

- Set hidden dimension to 300 units per layer

- Include global activation function (ReLU) and batch normalization between layers

- Add attention mechanism to weight important molecular substructures

Training Protocol:

- Employ transfer learning by pretraining on large chemical databases (e.g., ChEMBL)

- Apply gradual partial fine-tuning strategy for specific ADMET endpoints [39]

- Use Adam optimizer with initial learning rate of 0.001 and reduce on plateau

- Implement early stopping with patience of 50 epochs based on validation loss

Multi-task Learning:

- Design shared GNN backbone with task-specific output heads for multiple ADMET endpoints

- Weight loss functions according to task importance and data quality

- Regularize shared representations to prevent task interference

Validation and Interpretation:

- Implement gradient-based attribution methods to identify important molecular substructures

- Visualize message passing paths to interpret model decisions

- Benchmark against classical ML models and existing tools

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for developing machine learning models in ADMET prediction, covering data curation, model selection, training, and deployment.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key software tools and resources for ADMET machine learning research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in ADMET |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular descriptor calculation and fingerprint generation | Compute Morgan fingerprints and 2D descriptors for classical ML [38] |

| XGBoost | Machine Learning Library | Gradient boosting framework | Build high-performance models for Caco-2 and other ADMET endpoints [38] [39] |

| ChemProp | Deep Learning Package | Graph neural network implementation | Message passing neural networks for molecular property prediction [38] |

| Descriptastorus | Descriptor Tool | Normalized molecular descriptor calculation | Generate RDKit 2D descriptors normalized using Novartis compound catalog [38] |

| Public ADMET Databases | Data Resources | Experimental measurement collections | Sources for Caco-2, solubility, metabolic stability data [38] [37] |

| ASAP-Polaris-OpenADMET | Benchmarking Platform | Blind prediction challenges | Model validation and performance benchmarking [40] [39] |

Comparative Analysis and Strategic Implementation

Algorithm Selection Framework

The choice between classical machine learning and advanced deep learning approaches depends on multiple factors, including dataset size, computational resources, and specific ADMET endpoints. Classical methods like XGBoost demonstrate exceptional performance for many ADMET prediction tasks, particularly with limited data (n < 10,000 compounds) and well-curated molecular descriptors [38] [39]. These methods offer advantages in computational efficiency, interpretability, and robustness.

In contrast, deep learning approaches including GNNs and transformers show particular strength when applied to larger datasets (n > 10,000 compounds) and for modeling complex endpoints influenced by intricate molecular patterns and long-range dependencies [40] [41]. The architectural advantage of GNNs in directly processing molecular graphs eliminates the need for manual feature engineering, potentially capturing novel structure-property relationships missed by predefined descriptors.

Integrated Modeling Strategy

Figure 2: Decision framework for selecting machine learning algorithms based on dataset size and ADMET endpoint complexity.

A strategic approach to ADMET model development should consider the specific context and constraints of the drug discovery project. For early-stage projects with limited chemical data, classical ML methods with careful feature engineering provide the most pragmatic solution. As projects advance and accumulate more experimental data, hybrid approaches that ensemble classical and deep learning methods often deliver superior performance [39]. For organizations with substantial computational resources and large, diverse chemical libraries, investment in deep learning infrastructure and transfer learning methodologies can provide long-term advantages, particularly for predicting complex pharmacokinetic properties influenced by multiple biological mechanisms.

The field of ADMET prediction continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its trajectory. Hybrid AI-quantum frameworks show promise for capturing complex molecular interactions with unprecedented accuracy, while multi-omics integration aims to contextualize ADMET properties within broader biological systems [15]. The development of foundation models for chemistry, pretrained on massive compound libraries, represents another frontier with potential to revolutionize molecular property prediction through enhanced transfer learning capabilities [41] [39].

In conclusion, the strategic selection and implementation of machine learning algorithms—from robust classical methods like Random Forests and XGBoost to advanced Graph Neural Networks—are revolutionizing ADMET prediction in drug discovery. By understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate application contexts of each algorithm, researchers can build predictive models that significantly reduce late-stage attrition and accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapeutics. The continuous benchmarking of these approaches through community challenges and industrial validation ensures that the field progresses toward increasingly reliable and actionable predictive tools [40] [38] [39].

The high failure rate of drug candidates due to unsatisfactory Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties has made computational prediction an indispensable component of modern drug discovery. [42] Today's researchers have access to an evolving ecosystem of tools ranging from freely accessible academic web servers to sophisticated proprietary AI platforms. These tools leverage advanced machine learning algorithms, comprehensive datasets, and user-friendly interfaces to provide critical early insights into the pharmacokinetic and safety profiles of chemical compounds, thereby helping to de-risk the development pipeline. This application note provides a detailed overview of leading ADMET prediction tools, with specific protocols for their effective use in research settings.

admetSAR3.0: A Comprehensive Free Tool for Academic Research

admetSAR3.0 represents a significant evolution in freely accessible ADMET prediction platforms. Developed by academic researchers, this web server has grown substantially since its initial launch in 2012. The platform now hosts over 370,000 manually curated experimental ADMET data points for more than 100,000 unique compounds, sourced from peer-reviewed literature and established databases like ChEMBL, DrugBank, and ECOTOX. [43] [44]

A key advancement in admetSAR3.0 is its dramatic expansion of predictive endpoints, now offering 119 distinct ADMET properties—more than double the previous version. [43] This includes new dedicated sections for environmental and cosmetic risk assessment, broadening its application beyond pharmaceutical development into chemical safety evaluation. [43] The platform employs an advanced multi-task graph neural network framework (CLMGraph) that leverages contrastive learning pre-training on 10 million small molecules to enhance prediction robustness. [43]

Table 1: Key Features of admetSAR3.0

| Feature Category | Specification | Practical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Data Foundation | 370,000+ experimental data points; 104,652 unique compounds [43] | High-quality training data improves model reliability |

| Prediction Scope | 119 endpoints across 5 categories [43] | Comprehensive property coverage for thorough assessment |

| Technical Architecture | CLMGraph neural network framework [43] | State-of-the-art machine learning for accurate predictions |

| Specialized Modules | ADMETopt for molecular optimization [43] | Guides structural improvement of problematic compounds |

| Accessibility | Free web access; no login required [43] | Democratizes access for academic and small biotech researchers |

Proprietary AI-Driven Drug Discovery Platforms

The commercial landscape for AI-driven drug discovery has matured significantly, with several platforms demonstrating tangible success in advancing candidates to clinical trials. These platforms typically employ more specialized architectures and leverage massive proprietary datasets.

Exscientia's End-to-End Platform exemplifies the integrated approach, utilizing AI at every stage from target selection to lead optimization. [45] The company has reported designing clinical compounds in cycles approximately 70% faster while requiring 10-fold fewer synthesized compounds than industry standards. [45] Their platform uniquely incorporates patient-derived biology through high-content phenotypic screening of AI-designed compounds on actual patient tumor samples, enhancing translational relevance. [45]