Multi-Objective Optimization in Anticancer Drug Discovery: Building Better Compound Libraries with Machine Learning

This article explores the transformative role of multi-objective optimization (MOO) in developing selective and effective anticancer compound libraries.

Multi-Objective Optimization in Anticancer Drug Discovery: Building Better Compound Libraries with Machine Learning

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of multi-objective optimization (MOO) in developing selective and effective anticancer compound libraries. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it details the computational framework that simultaneously optimizes conflicting goals like biological activity (e.g., pIC50 against targets such as ERα) and ADMET properties (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity). We cover foundational concepts, key methodologies including QSAR models and algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and improved genetic algorithms, strategies to overcome challenges like data imbalance and reward hacking, and finally, validation through molecular dynamics and in vitro testing. This synthesis provides a roadmap for leveraging MOO to accelerate the creation of safer, more potent cancer therapeutics.

The Pressing Need for Multi-Objective Optimization in Anticancer Discovery

A primary challenge in modern oncology is the dual obstacle of drug resistance and treatment-related toxicity. Multi-objective optimization (MOO) provides a powerful computational framework to address this challenge by systematically balancing competing treatment goals, such as maximizing antitumor efficacy while minimizing harmful side effects [1] [2]. Instead of identifying a single "perfect" solution, these approaches generate a set of Pareto-optimal solutions representing the best possible trade-offs between objectives, enabling clinicians to select regimens based on individual patient needs and clinical priorities [3] [4].

In the context of anticancer compound research, MOO frameworks can be applied to optimize various aspects of therapy, including identifying selective drug combinations [1], determining optimal dosing schedules [2] [4], and designing nanoparticle drug delivery systems [3]. The fundamental strength of these approaches lies in their ability to incorporate quantitative models of tumor biology and drug effects to navigate complex decision spaces beyond human analytical capacity [5].

Key Quantitative Frameworks and Models

Modeling Drug Response and Therapeutic Selectivity

The foundation of effective optimization requires robust quantitative models of drug effects. A critical concept is the therapeutic effect (E), defined as the negative logarithm of the growth fraction (Q), where Q represents the relative number of live cells compared to an untreated control: E(c;l) = -logQ(c;l) [1]. This logarithmic formulation provides additivity for drugs acting independently under the Bliss independence model.

For combination therapies, the therapeutic effect can be modeled using a pair interaction model:

Where the first sum represents the Bliss model effect, and the second sum captures interaction effects (Bliss excess) between drug pairs [1]. This model enables prediction of higher-order combination effects based on pairwise measurements, significantly reducing experimental burden.

The nonselective effect, representing potential toxicities, can be modeled as the mean drug effect across multiple cell types, serving as a surrogate for adverse effects in healthy tissues [1]. This allows for optimization of cancer-selective treatments using cancer cell measurements alone without requiring simultaneous testing on healthy cells.

Modeling Drug Resistance Evolution

Understanding resistance dynamics is essential for sustainable treatment strategies. Mathematical frameworks can infer drug resistance dynamics from genetic lineage tracing and population size data without direct phenotype measurement [6]. These models typically incorporate:

- Pre-existing resistance fraction (ρ): The proportion of resistant cells at treatment initiation

- Phenotype-specific birth and death rates: Different growth characteristics for sensitive vs. resistant populations

- Phenotypic switching parameters (μ, σ): Probabilities of transitioning between sensitive and resistant states

- Fitness cost parameters (δ): Growth penalties for resistant phenotypes in untreated environments

Three progressively complex models can capture diverse resistance behaviors:

- Model A (Unidirectional Transitions): Simple sensitive⇌resistant transitions

- Model B (Bidirectional Transitions): Incorporates reversible phenotype switching

- Model C (Escape Transitions): Includes drug-dependent emergence of fit-resistant clones [6]

Diagram Title: Drug Resistance Evolution Models

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: High-Throughput Combination Screening for Selective Synergy

Objective: Identify synergistic drug combinations with maximal cancer cell inhibition and minimal non-selective toxicity.

Materials:

- Cancer cell lines relevant to research focus

- 384-well or 1536-well microplates

- Automated liquid handling system

- Compound libraries (see Section 5 for sources)

- Cell viability assay reagents (e.g., ATP-based quantification)

- DMSO as compound solvent

Procedure:

Plate Preparation:

- Seed cells in optimized density in assay plates (e.g., 1,000-5,000 cells/well for 384-well format)

- Incubate for 24 hours to allow cell attachment

Compound Transfer:

- Using automated liquid handlers, transfer compounds from library plates to assay plates

- Include DMSO-only controls for normalization

- Implement checkerboard design for combination matrices

Treatment and Incubation:

- Incubate plates for 72-96 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂

- Maintain consistent incubation periods across experiments

Viability Assessment:

- Add cell viability reagent (e.g., Cell Titer-Glo for ATP quantification)

- Measure luminescence using plate reader

Data Processing:

- Calculate growth fraction:

Q = (Signal_treated - Signal_blank) / (Signal_untreated - Signal_blank) - Compute therapeutic effect:

E = -log(Q) - Calculate Bliss excess for combinations:

Eij_XS = Eij(ci,cj) - Ei(ci) - Ej(cj)

- Calculate growth fraction:

Quality Control:

Protocol: Quantitative Measurement of Drug Resistance Dynamics

Objective: Track emergence and evolution of drug-resistant populations during prolonged treatment.

Materials:

- Lentiviral barcoding system

- Antibiotic selection agents (e.g., puromycin)

- DNA extraction kit

- Next-generation sequencing platform

- Cell culture vessels with appropriate capacity

Procedure:

Genetic Barcoding:

- Transduce cells with lentiviral barcode library at low MOI (<0.3) to ensure single integration

- Select with appropriate antibiotic for 5-7 days

- Expand population to create barcoded master cell bank

Experimental Evolution:

- Split barcoded cells into replicate populations

- Apply treatment regimens with periodic drug exposure

- Maintain parallel untreated control populations

- Passage cells before reaching confluence

Sampling and Monitoring:

- Collect cell samples at predetermined intervals (e.g., weekly)

- Count cells to track population sizes

- Preserve cell pellets for DNA extraction

Lineage Tracing:

- Extract genomic DNA from cell pellets

- Amplify barcode regions with PCR using indexed primers

- Sequence amplicons using high-throughput sequencing

- Map sequences to reference barcode library

Data Analysis:

- Quantify barcode frequencies across timepoints

- Apply mathematical framework to infer resistance parameters [6]

- Estimate pre-existing resistance fractions and switching rates

Diagram Title: Resistance Dynamics Workflow

Quantitative Data and Optimization Parameters

Multi-Objective Optimization Parameters in Cancer Therapy

Table 1: Key Parameters in Multi-Objective Optimization Frameworks

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Typical Range/Values | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Effect | E | Negative logarithm of growth fraction: E = -log(Q) | 0 (no effect) to >2 (strong effect) | All efficacy modeling [1] |

| Bliss Excess | E_XS | Deviation from expected independent drug action | Positive (synergy) or negative (antagonism) | Combination therapy optimization [1] |

| Pre-existing Resistance Fraction | ρ | Proportion of resistant cells before treatment | 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻² | Resistance evolution modeling [6] |

| Phenotypic Switching Rate | μ | Probability of sensitive→resistant transition per division | 10⁻⁸ (genetic) to 10⁻² (non-genetic) | Plasticity and resistance forecasting [6] |

| Fitness Cost | δ | Growth penalty for resistant phenotype without treatment | 0 (no cost) to 0.9 (strong cost) | Resistance management strategies [6] |

| Nanoparticle Diameter | d | Size of drug delivery particles | 1-1000 nm | Nanotherapy optimization [3] |

| Binding Avidity | α | Strength of nanoparticle attachment to targets | 10¹⁰-10¹² m⁻² | Targeted therapy design [3] |

| Drug Diffusivity | D | Rate of drug spread through tissue | 10⁻⁶-10⁻³ mm²/s | Drug delivery system optimization [3] |

Experimentally-Derived Optimization Outcomes

Table 2: Representative Multi-Objective Optimization Results from Experimental Studies

| Study Focus | Optimization Algorithm | Key Findings | Therapeutic Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer-selective combinations [1] | Exact multiobjective optimization | Identified co-inhibition partners for vemurafenib in BRAF-V600E melanoma | Improved selective inhibition vs. potential compensatory pathway effects |

| Nanoparticle design [3] | Derivative-free optimization | Smaller nanoparticles (288-334 nm) optimal for large tumors | Tumor targeting vs. tissue penetration depth |

| Chemotherapy scheduling [4] | Two-archive multi-objective Squirrel Search Algorithm (TA-MOSSA) | Effective regimens for combination chemotherapy | Tumor reduction vs. toxic side effects |

| Drug resistance management [6] | Bayesian inference frameworks | Distinct resistance mechanisms in SW620 vs. HCT116 cell lines | Immediate efficacy vs. long-term resistance prevention |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Anticancer Compound Optimization

| Resource | Description | Key Features | Application in MOO Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCI/DTP Open Chemical Repository [7] | >200,000 diverse compounds | Available as vials or plated sets; no cost except shipping | Primary source for diverse chemical structures |

| Approved Oncology Drugs Set XI [7] | 179 FDA-approved anticancer drugs | 3 microtiter plates; 10 mM in DMSO; quality controlled | Benchmarking and combination studies |

| NCI Diversity Set VII [7] | 1,581 structurally diverse compounds | Selected using 3D pharmacophore analysis; >90% purity | Initial screening for novel activities |

| MCE Anti-Cancer Compound Library [8] | 9,784 anti-cancer compounds | Targets key pathways; includes approved and experimental agents | Targeted pathway screening |

| Stanford HTS Collection [9] | >225,000 diverse compounds | Includes specialized kinase, CNS, and covalent libraries | High-throughput screening campaigns |

| NCI Mechanistic Set VI [7] | 802 compounds with known growth inhibition patterns | Selected based on NCI-60 cell line screening patterns | Mechanism-of-action studies |

| Natural Products Set V [7] | 390 natural product-derived compounds | Structural diversity; >90% purity | Exploring novel chemical space |

In modern anticancer drug discovery, the primary objective extends beyond merely discovering compounds with high biological activity. It necessitates a careful balance between potent target inhibition and favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles. The core of this balance lies in optimizing two key sets of parameters: biological activity, typically quantified by the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) and its negative logarithm (pIC50), and Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties. A compound exhibiting excellent in vitro potency becomes therapeutically irrelevant if it demonstrates poor solubility, inadequate metabolic stability, or unacceptable toxicity. Framing this challenge within the context of multi-objective optimization allows researchers to systematically navigate these competing objectives to design compound libraries with a higher probability of clinical success.

The evolution of computational methods has revolutionized this balancing act. Techniques like Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations now enable the prediction of both activity and ADMET properties early in the discovery pipeline. For instance, a study on naphthoquinone derivatives as MCF-7 breast cancer inhibitors successfully integrated these methods. Researchers developed QSAR models to predict pIC50, then applied ADMET screening to filter promising candidates, followed by docking and dynamics simulations to validate their binding to the target topoisomerase IIα [10]. This integrated approach exemplifies the modern strategy for defining and achieving balanced drug discovery objectives.

Core Data and Objectives

Quantitative Definition of Key Parameters

A precise understanding of the core parameters is fundamental to setting clear objectives. The table below defines and explains the key metrics involved in this balancing act.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Multi-Objective Optimization for Anticancer Compounds

| Parameter | Description | Role in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| pIC50 | The negative logarithm of the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), a measure of a compound's potency. | Primary indicator of biological activity against the cancer target; higher values indicate greater potency [10]. |

| ADMET Profile | A composite profile encompassing a compound's Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity. | Predicts pharmacokinetics and safety; used to filter out compounds with poor developability [10]. |

| Index of Ideality of Correlation (IIC) | A statistical metric used in QSAR model development to enhance predictive quality. | Improves the robustness and predictive power of QSAR models for pIC50 prediction [10]. |

| Correlation Intensity Index (CII) | Another statistical criterion used alongside IIC in optimizing QSAR models. | Further strengthens the statistical foundation of predictive activity models [10]. |

Establishing Target Thresholds

Defining the optimization objectives requires setting specific, quantitative thresholds for these parameters. The following table outlines typical target values for promising anticancer compounds, derived from established discovery campaigns.

Table 2: Exemplary Target Thresholds for Anticancer Compound Optimization

| Parameter | Exemplary Target / Observation | Context and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| pIC50 | > 6 (i.e., IC50 < 1 μM) | In a naphthoquinone study, 67 compounds showed pIC50 > 6, indicating significant potency against MCF-7 cells [10]. |

| ADMET Screening | Passage of defined filters | From 2300+ predicted compounds, only 16 passed the applied ADMET criteria, highlighting its critical role as a filter [10]. |

| Molecular Diversity | Presence of multiple unique clusters | A robust QSAR model for FLT3 inhibitors was built on a dataset with 124 clusters, ensuring coverage of a broad chemical space and model generalizability [11]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Predictive QSAR Modeling for pIC50

This protocol details the development of a robust QSAR model to predict pIC50 values, a critical first step in prioritizing compounds for synthesis and testing.

1. Dataset Curation:

- Collect a dataset of compounds with experimentally determined IC50 values against the specific cancer cell line or molecular target (e.g., MCF-7 for breast cancer).

- Ensure the dataset is sufficiently large and diverse. For example, a robust FLT3 inhibitor model was trained on 1,350 compounds, which was 14 times larger than previous studies [11].

- Convert IC50 values to pIC50 using the formula: pIC50 = -log10(IC50).

- Divide the dataset into training, validation, and test sets using a defined random split (e.g., 80/10/10).

2. Molecular Descriptor Calculation:

- Calculate molecular descriptors or generate molecular representations. Common approaches include:

- SMILES and Graph Descriptors: Use a hybrid of Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) notation and hydrogen-suppressed graphs (HSG) to generate descriptors [10].

- Fingerprints: Generate 2D fingerprints such as MACCS keys or extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFP) to represent molecular structures [12] [11].

- RDKit 2D Descriptors: Calculate a comprehensive set of physicochemical descriptors using software like RDKit [12].

3. Model Training and Validation:

- Algorithm Selection: Train a model using a suitable machine learning algorithm. The Random Forest Regressor (RFR) has demonstrated superior performance and resistance to overfitting in predicting pIC50 [11].

- Model Optimization: Employ techniques like Monte Carlo optimization to correlate descriptors with biological activity. Incorporate the Index of Ideality of Correlation (IIC) and Correlation Intensity Index (CII) to enhance model robustness [10].

- Validation: Perform rigorous internal validation (e.g., leave-one-out or 10-fold cross-validation) and external validation on a held-out test set. Report standard metrics including Q² (for cross-validation) and R² (for test set prediction) [11].

Protocol 2: Integrated ADMET Screening

This protocol describes the computational screening of compounds to eliminate those with unfavorable pharmacokinetic or toxicological profiles.

1. In silico ADMET Prediction:

- Utilize specialized software or web servers to predict key ADMET parameters for the compound library. Critical parameters to predict include:

- Absorption: Aqueous solubility, Caco-2 permeability, human intestinal absorption.

- Distribution: Plasma protein binding, volume of distribution.

- Metabolism: Interaction with major cytochrome P450 enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4).

- Excretion: Half-life, clearance.

- Toxicity: Mutagenicity (Ames test), hepatotoxicity, hERG channel inhibition (cardiotoxicity).

2. Application of Filtering Criteria:

- Establish strict, project-specific thresholds for each ADMET parameter based on known drug-like space and target product profile.

- Systematically filter the compound library, retaining only those compounds that pass all predefined criteria. This process is highly stringent; for example, a screening of 2,300 naphthoquinones resulted in only 16 candidates passing ADMET filters [10].

Protocol 3: Molecular Docking and Dynamics for Binding Confirmation

This protocol is used to validate the interaction between top-ranked compounds and the biological target, providing insights into the structural basis of activity.

1. Molecular Docking:

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., Topoisomerase IIα, PDB ID: 1ZXM) from the Protein Data Bank. Prepare the structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning bond orders, and optimizing side-chain conformations.

- Ligand Preparation: Generate 3D structures of the candidate compounds and assign correct protonation states at physiological pH.

- Docking Simulation: Perform molecular docking to predict the preferred orientation and binding affinity (scoring) of each ligand within the target's active site. Identify key interacting amino acid residues [10].

2. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations:

- System Setup: Solvate the top-ranked ligand-protein complex (e.g., compound A14) in a water box and add ions to neutralize the system.

- Production Run: Run an all-atom MD simulation for an extended period (e.g., 200-300 ns) under physiological conditions (temperature: 310 K, pressure: 1 bar) to assess the stability of the complex over time [10].

- Trajectory Analysis: Analyze the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), and specific ligand-protein interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) throughout the simulation trajectory to confirm binding stability.

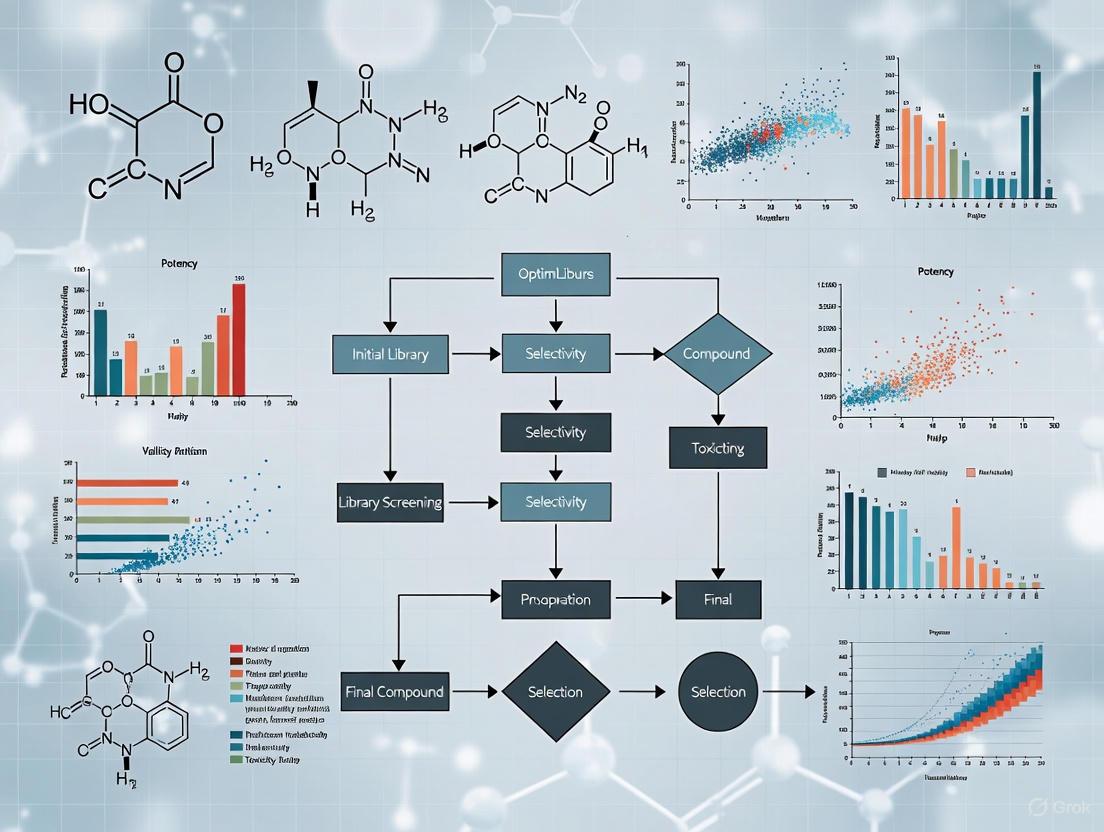

Diagram 1: Multi-Objective Compound Optimization Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the sequential integration of computational protocols to balance pIC50 and ADMET properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential computational tools and resources required to execute the described protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| CORAL Software | A software tool that uses Monte Carlo optimization to develop QSAR models based on SMILES notation and molecular graphs. | Protocol 1: Building predictive pIC50 models using IIC and CII criteria [10]. |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit that provides functionality for descriptor calculation and fingerprint generation. | Protocol 1: Calculating 2D molecular descriptors and MACCS keys for model training [12] [11]. |

| Random Forest Regressor | A robust machine learning algorithm available in libraries like scikit-learn, known for handling high-dimensional data and resisting overfitting. | Protocol 1: Training the core QSAR model for pIC50 prediction [11]. |

| ADMET Prediction Software | Specialized platforms (e.g., SwissADME, pkCSM, ProTox) for predicting pharmacokinetic and toxicity endpoints. | Protocol 2: In silico screening of compounds for desirable ADMET properties [10]. |

| Molecular Docking Software | Programs (e.g., AutoDock Vina, GOLD) that predict ligand binding modes and affinities to a protein target. | Protocol 3: Assessing the binding pose and affinity of candidate compounds [10]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Suites (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER) for simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | Protocol 3: Validating the stability of ligand-receptor complexes over hundreds of nanoseconds [10]. |

The Rise of Machine Learning and QSAR Models in Modern Drug Development

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling has fundamentally transformed modern drug development, shifting the paradigm from traditional trial-and-error approaches to predictive, data-driven methodologies [13] [14]. This revolution addresses critical bottlenecks in pharmaceutical research and development, which traditionally spans 10–15 years with costs exceeding $2.8 billion per approved drug [15]. Machine learning (ML) algorithms now enable researchers to analyze vast chemical and biological datasets, dramatically accelerating early-stage research and improving the prediction of compound efficacy, toxicity, and pharmacokinetic properties [16] [17].

These technological advances are particularly crucial for multi-objective optimization in anticancer compound library design, where the goal is to efficiently explore immense chemical spaces to identify molecules with desired therapeutic profiles. AI-driven QSAR models have evolved from basic linear regression to sophisticated deep learning architectures capable of capturing complex, non-linear relationships between molecular structure and biological activity, making them indispensable tools for prioritizing synthetic efforts and streamlining the hit-to-lead process [13] [18].

The Evolution of QSAR Modeling: From Classical Statistics to Deep Learning

Classical QSAR Foundations

Classical QSAR methodologies establish mathematical relationships between molecular descriptors—numerical representations of chemical structures—and biological activities using statistical techniques like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS), and Principal Component Regression (PCR) [15] [13]. These approaches are valued for their interpretability, speed, and regulatory acceptance, particularly when dealing with congeneric series of compounds where linear relationships are sufficient [13] [18]. Model validation traditionally relies on metrics such as R² (coefficient of determination) and Q² (cross-validated R²), with careful attention to the model's applicability domain to ensure reliable predictions for new chemical entities [15].

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Advancements

Modern QSAR modeling leverages machine learning and deep learning to handle high-dimensional, complex chemical datasets far beyond the capabilities of classical approaches [13]. Algorithms such as Random Forests (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) excel at capturing non-linear patterns and are widely used for virtual screening and toxicity prediction [13] [18]. More recently, deep learning architectures including Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and SMILES-based transformers have enabled the development of "deep descriptors" that automatically learn hierarchical molecular features from raw structural data without manual feature engineering [13] [18].

Table 1: Evolution of QSAR Modeling Approaches

| Modeling Era | Key Algorithms | Typical Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical QSAR | MLR, PLS, PCR | Lead optimization, mechanistic interpretation | High interpretability, fast computation, regulatory familiarity | Limited to linear relationships, struggles with large, complex datasets |

| Machine Learning | Random Forests, SVM, kNN | Virtual screening, toxicity prediction, ADMET profiling | Handles non-linear relationships, robust with noisy data | Requires careful feature selection, moderate interpretability |

| Deep Learning | Graph Neural Networks, Transformers | De novo drug design, ultra-large library screening | Automatic feature learning, superior predictive performance on complex tasks | "Black-box" nature, high computational resources, large data requirements |

Application Notes: AI-Driven QSAR in Anticancer Drug Discovery

Current Landscape and Clinical Impact

AI-driven drug discovery platforms have demonstrated remarkable success in advancing therapeutic candidates into clinical trials across multiple disease areas, with oncology being a predominant focus [16] [17]. By mid-2025, over 75 AI-derived molecules had reached clinical stages, with several platforms showcasing significant reductions in discovery timelines [16]. For instance, Insilico Medicine's AI-designed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis drug progressed from target discovery to Phase I trials in just 18 months, substantially faster than the traditional 5-year average for early discovery [16].

In anticancer drug development, QSAR models specifically tailored for lung cancer therapeutics have accelerated the identification and optimization of compounds targeting key pathways such as EGFR [19]. These models address critical bottlenecks in drug development, including data imbalance, model interpretability, and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) prediction failures, which are paramount for designing effective and safe oncology drugs [19].

Multi-Objective Optimization for Anticancer Compound Libraries

The design of anticancer compound libraries represents an NP-hard combinatorial challenge due to the immense chemical space of possible molecules [20]. Advanced computational approaches using multi-objective optimization enable simultaneous optimization of multiple molecular properties critical for anticancer activity. Recent methodologies employ genetic algorithms (GAs) such as NSGA-II to partition large peptide libraries into optimized subsets that maximize both library coverage and diversity while maintaining desirable physicochemical properties [20].

This multi-library approach effectively balances the synthetic effort required for library production with the downstream efficiency of hit deconvolution, ensuring thorough exploration of chemical space relevant to anticancer targets [20]. For example, simulated annealing-supported diversity analysis has enabled the optimization of libraries containing over 9.8 million sequences, overcoming previous computational constraints on library size [20].

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics of AI-Driven Drug Discovery Platforms in Oncology

| Company/Platform | AI Approach | Therapeutic Focus | Key Clinical Candidates | Reported Efficiency Gains |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia | Generative AI, Centaur Chemist | Oncology, Immuno-oncology | CDK7 inhibitor (GTAEXS-617), LSD1 inhibitor (EXS-74539) | 70% faster design cycles, 10x fewer synthesized compounds [16] |

| Insilico Medicine | Generative chemistry, target discovery | Fibrosis, Oncology | ISM001-055 (TNK inhibitor for IPF) | Target-to-clinic in 18 months [16] |

| Schrödinger | Physics-enabled ML design | Immunology, Oncology | TAK-279 (TYK2 inhibitor) | Advanced to Phase III trials [16] |

| BenevolentAI | Knowledge-graph target discovery | Multiple, including Oncology | Baricitinib repurposing for COVID-19 | Accelerated drug repurposing [16] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Development and Validation of a Robust QSAR Model for NF-κB Inhibitors

Background: This protocol outlines the development of QSAR models for predicting Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) inhibitory activity, following a case study of 121 compounds [15]. NF-κB is a promising therapeutic target for various immunoinflammatory and cancer diseases.

Materials and Reagents:

- Dataset: 121 compounds with reported IC₅₀ values against NF-κB [15]

- Software: Molecular descriptor calculation tools (DRAGON, PaDEL, RDKit) [13] [18]

- Computational Environment: Python/R with scikit-learn, KNIME, or AutoQSAR for model development [13]

Procedure:

Data Collection and Curation:

- Collect biological activity data (IC₅₀ values) for 121 NF-κB inhibitors from literature sources [15]

- Ensure consistent activity measurements obtained through standardized experimental protocols

- Apply Lipinski's rule of five and ADMET filters to remove compounds with undesirable properties

Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Selection:

Dataset Division:

- Randomly split compounds into training set (∼66%) and test set (∼34%) [15]

- Ensure structural diversity and activity range representation in both sets

Model Development:

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR): Develop linear models using selected descriptors

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANN): Train [8.11.11.1] architecture with selected descriptors as input nodes [15]

- Compare model performance using statistical metrics

Model Validation:

- Internal Validation: Calculate Q² through cross-validation on training set

- External Validation: Assess predictive power on test set compounds

- Applicability Domain: Define using leverage method to identify reliable prediction boundaries [15]

Virtual Screening Application:

- Apply validated model to screen new compound libraries for NF-κB inhibitory potential

- Prioritize top-ranking compounds for synthesis and experimental validation

Troubleshooting:

- If model performance is poor, revisit descriptor selection process

- If overfitting occurs, increase training set size or apply regularization techniques

- For limited dataset, consider transfer learning or data augmentation approaches

Protocol 2: Multi-Library Optimization for Anticancer Peptide Discovery

Background: This protocol describes a multi-library approach to parallelized sequence space exploration for designing optimized anticancer peptide libraries, enabling efficient coverage of vast chemical spaces [20].

Materials and Reagents:

- Initial Library: User-defined peptide library of interest

- Software: Access to specialized web server (https://deshpet.riteh.hr) with free registration required [20]

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing infrastructure for large library processing

Procedure:

Library Definition:

Multi-Objective Optimization Setup:

- Configure NSGA-II-based algorithm to partition initial library into optimized subsets [20]

- Set optimization objectives:

- Maximize intra-library diversity (mass diversity, sequence variance)

- Maximize cross-library diversity (minimize sequence overlap between libraries)

- Maximize coverage of original chemical space [20]

- Apply simulated annealing-supported hybrid assessment for libraries exceeding 9.8×10⁶ sequences [20]

Algorithm Execution:

- Implement adaptive parameter inference based on library characteristics

- Activate early stopping mechanism based on hyperarea oscillation monitoring to reduce execution time by ∼22% [20]

- Run optimization until convergence criteria are met

Library Output and Analysis:

- Generate multiple peptide libraries with maximized diversity and coverage

- Analyze library compositions for desired properties (charge, hydrophobicity, etc.)

- Integrate with antimicrobial QSAR model if dual functionality is desired [20]

Experimental Validation:

- Proceed with split-and-mix synthesis of optimized libraries

- Screen for anticancer activity through appropriate assays

- Conduct hit deconvolution on active library pools

Troubleshooting:

- For computational complexity issues, utilize simulated annealing approximation

- If diversity metrics are suboptimal, adjust objective function weights

- For specific anticancer targets, incorporate structure-based filters in optimization

Diagram 1: Multi-Library Peptide Optimization Workflow. This diagram illustrates the computational pipeline for designing multiple, diverse peptide libraries that maximize coverage of chemical space while maintaining synthetic feasibility.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AI-Driven QSAR

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Anticancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptor Software | DRAGON, PaDEL, RDKit | Calculation of 1D, 2D, 3D molecular descriptors | Encoding structural features for QSAR model development [13] [18] |

| Machine Learning Platforms | scikit-learn, KNIME, AutoQSAR | Implementation of ML algorithms for model development | Building predictive models for anticancer activity [13] |

| Multi-Objective Optimization Tools | Custom NSGA-II implementation, https://deshpet.riteh.hr | Parallel optimization of multiple library properties | Designing diverse anticancer compound libraries [20] |

| Cloud Computing Infrastructure | AWS, Google Cloud, Azure | Scalable computational resources for large dataset processing | Enabling complex deep learning models and virtual screening [16] [17] |

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem, ZINC | Sources of bioactivity data and compound libraries | Training data for QSAR models, sourcing screening compounds [21] |

| Interpretability Tools | SHAP, LIME | Explainable AI for model interpretation | Identifying structural features driving anticancer activity [13] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

Paradigm Shift in Model Evaluation Metrics

Traditional best practices for QSAR modeling have emphasized dataset balancing and balanced accuracy as key objectives. However, for virtual screening of modern ultra-large chemical libraries, a paradigm shift is occurring toward prioritizing Positive Predictive Value (PPV) over balanced accuracy [21]. This change recognizes the practical constraints of experimental validation, where typically only 128 compounds (a single 1536-well plate) can be tested despite virtual screening of billions of compounds [21].

Training models on imbalanced datasets with the highest PPV achieves hit rates at least 30% higher than using balanced datasets, directly translating to more efficient experimental follow-up in anticancer compound discovery [21]. This approach optimizes for the identification of true active compounds within the limited number of molecules that can be practically tested.

Regulatory Landscape and Ethical Considerations

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has established the CDER AI Council to provide oversight and coordination of AI activities in drug development, reflecting the rapid adoption of these technologies [22]. By 2023, the FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research had reviewed over 500 submissions incorporating AI components, with a significant increase observed in recent years [22]. This regulatory evolution is creating a framework for the responsible implementation of AI in anticancer drug discovery while ensuring patient safety and efficacy standards.

Future directions in AI-integrated QSAR modeling include increased focus on interpretability and explainability of complex deep learning models, integration with structural biology insights from molecular docking and dynamics, and application to novel therapeutic modalities such as PROTACs for targeted protein degradation in cancer therapy [13] [18]. As these technologies mature, they promise to further accelerate the discovery of innovative anticancer therapies through more efficient exploration and optimization of chemical space.

In the field of drug discovery, particularly in the development of anti-cancer compounds, researchers are consistently faced with the challenge of balancing multiple, often competing, objectives. An ideal anti-cancer drug candidate must demonstrate not only high biological activity (efficacy against the cancer target) but also favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity - ADMET) [23] [24]. Optimizing for one of these properties in isolation often leads to the degradation of others, creating a complex decision-making landscape. Multi-objective optimization (MOO) is a mathematical framework designed to address exactly this class of problems, and the Pareto Front is a central concept within this framework that helps researchers understand and navigate the inherent trade-offs [25] [26].

This article details the core principles of multi-objective optimization and the Pareto Front, framing them within the context of modern anticancer compound research. It provides application notes, detailed protocols, and visualization tools to equip scientists with the methodologies needed to advance their drug discovery programs.

Core Concepts and Mathematical Foundations

Multi-Objective Optimization

Multi-objective optimization involves the simultaneous optimization of two or more objective functions. In mathematical terms, a multi-objective optimization problem can be formulated as shown in the dot code below.

The diagram above illustrates the fundamental structure of a MOO problem. Formally, it is defined as:

min x ∈ X (f1(x), f2(x), …, fk(x))

where the integer k ≥ 2 is the number of objectives, x is the vector of decision variables (e.g., molecular descriptors or synthesis conditions), and X is the feasible region constrained by physical, chemical, or experimental limitations [25]. In anti-cancer drug discovery, typical objectives include maximizing biological activity (e.g., expressed as PIC50, the negative logarithm of the half-maximal inhibitory concentration) while minimizing toxicity and optimizing ADMET properties [23] [24].

Pareto Optimality and the Pareto Front

In the presence of conflicting objectives, a single solution that optimizes all objectives simultaneously rarely exists. Instead, the solution of a MOO problem is a set of solutions known as the Pareto optimal set.

- Pareto Optimality: A solution x* ∈ X is considered Pareto optimal (or non-dominated) if no other feasible solution exists that can improve one objective without causing a degradation in at least one other objective [25] [26]. In other words, you cannot find a better point for all the objectives at the same time.

- Pareto Front (PF): The image of the Pareto optimal set in the objective space is called the Pareto Front. It is the set of all objective function vectors corresponding to the Pareto optimal solutions [27]. The Pareto Front visually represents all the optimal trade-offs between the conflicting objectives. The following dot code visualizes the relationship between the decision space and the objective space, culminating in the Pareto Front.

For a two-objective problem where both are to be minimized, the Pareto Front typically appears as a curve where moving from one solution to another involves trading off an amount of one objective for a gain in the other. The ideal objective vector defines the lower bounds of the objectives (if they were independently achievable), while the nadir objective vector defines the upper bounds across the Pareto set, together bounding the front [25].

Applications in Anti-Cancer Compound Research

The MOO framework has been successfully applied across various stages of anti-cancer drug discovery, from initial candidate screening to combination therapy design. The table below summarizes key applications and their optimized objectives.

Table 1: Applications of Multi-Objective Optimization in Anti-Cancer Research

| Application Area | Optimization Objectives | Algorithm/Method Cited | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-Breast Cancer Candidate Drugs [23] [24] | Maximize biological activity (PIC50), Optimize ADMET properties (Caco-2, CYP3A4, hERG, HOB, MN) | Improved AGE-MOEA, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | A complete framework for selecting drug candidates with balanced activity and safety. |

| Cancer-Selective Drug Combinations [1] | Maximize therapeutic effect (cancer cell death), Minimize non-selective effect (toxicity to healthy cells) | Exact multiobjective optimization, Bliss excess model | Identification of pairwise and higher-order drug combinations that are selectively toxic to cancer cells. |

| Target-Aware Molecule Generation [28] [29] | Maximize binding affinity (docking score) to target protein(s), Maximize drug-likeness (QED), Minimize synthetic accessibility (SA Score) | Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), PMMG, ParetoDrug | De novo generation of novel molecular structures satisfying multiple property constraints. |

| Chemotherapy Dosing & Scheduling [2] | Maximize tumor cell kill, Minimize host cell (immune cell) toxicity | Simulated Annealing, Genetic Algorithms | Determination of optimal drug dosing and treatment-relaxation schedules to aid patient recovery. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A Protocol for Multi-Objective Optimization of Anti-Breast Cancer Compounds

The following workflow, adapted from a 2022 study, outlines a complete protocol for optimizing anti-breast cancer drug candidates [23].

Phase 1: Feature Selection

- Objective: Identify a reduced set of molecular descriptors from a large initial pool (e.g., 729 descriptors) that have strong explanatory power for biological activity and ADMET properties.

- Procedure:

- Preprocessing: Remove descriptors with zero variance and normalize the data.

- Unsupervised Selection: Use a feature selection method based on unsupervised spectral clustering. This involves calculating the correlation coefficient, cosine similarity, and grey correlation degree between features, clustering them, and selecting the most important features from each cluster to reduce redundancy [23].

- Supervised Selection: Further refine the feature set using a Random Forest model combined with SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values to identify the top 20 molecular descriptors with the greatest impact on biological activity (pIC50) [24].

- Output: A compact set of molecular descriptors for model building.

Phase 2: Relation Mapping (QSAR Model Construction)

- Objective: Construct high-fidelity Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models that map the selected molecular descriptors to the target objectives (biological activity and ADMET endpoints).

- Procedure:

- Model Training: Train multiple machine learning algorithms (e.g., CatBoost, LightGBM, XGBoost, Random Forest) on the selected features.

- Model Evaluation: Compare model performance using metrics like R² for regression (pIC50) and F1-score for classification (ADMET properties). For instance, a well-constructed model can achieve an R² of 0.743 for pIC50 prediction and an F1-score of 0.9733 for CYP3A4 inhibition prediction [24].

- Model Fusion: Employ ensemble methods (e.g., stacking) to combine the best-performing models (e.g., LightGBM, RandomForest, XGBoost) to create a final, more robust predictor [23] [24].

- Output: Trained and validated QSAR models for each objective.

Phase 3: Multi-Objective Optimization

- Objective: Find the values of the molecular descriptors that yield the best possible compromises between the multiple objectives.

- Procedure:

- Problem Formulation: Define the MOO problem formally. For example: maximize pIC50, maximize Caco-2 permeability, minimize hERG toxicity, etc. [23].

- Algorithm Selection: Use a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm (MOEA) like an improved AGE-MOEA or Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to search for the Pareto front [23] [24].

- Execution: Run the optimization algorithm, using the QSAR models from Phase 2 as surrogate objective functions to evaluate potential solutions. The algorithm will iteratively generate populations of candidate molecular descriptor sets, converging towards the Pareto front.

- Output: A set of non-dominated solutions (the approximated Pareto front) representing optimal candidate compounds.

Phase 4: Candidate Selection

- Objective: Select final candidate compounds from the Pareto front for further validation.

- Procedure: Researchers analyze the Pareto-optimal solutions, considering the specific trade-offs between activity and ADMET properties that best align with the project's goals. There is no single "best" solution; the choice depends on strategic priorities [26].

- Output: A shortlist of promising anti-breast cancer candidate drugs for in vitro or in vivo testing.

Protocol for Identifying Cancer-Selective Drug Combinations

This protocol uses MOO to find drug combinations that are selectively effective against cancer cells while minimizing harm to healthy cells, a crucial aspect of reducing side effects [1].

- Data Collection: Acquire dose-response data (growth fraction, Q) for single drugs and pairs of drugs across a panel of cancer cell lines. Public resources like NCI-ALMANAC can be used [1].

- Effect Calculation: For each drug and combination, calculate the therapeutic effect as E = -log(Q). This logarithmic formulation makes the effect additive for independent drugs [1].

- Modeling Combination Effects: For a combination of N drugs, model its total therapeutic effect using a pair interaction model: E(c; l) = Σi=1N Ei(ci; l) + Σj=1N-1 Σk=j+1N Ej,kXS(cj, ck; l) where Ej,kXS is the "Bliss excess," quantifying the interaction (synergy or antagonism) between the drug pair over the Bliss independence model [1].

- Define Nonselective Effect: Estimate the nonselective effect (a proxy for toxicity) of a drug as its average effect across a large number of diverse cancer cell lines. The nonselective effect of a combination is modeled similarly to its therapeutic effect [1].

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Formulate the problem with two objectives: maximize therapeutic effect (on the target cancer cell line) and minimize nonselective effect. Use an exact multiobjective optimization method to identify the Pareto-optimal set of drug combinations and their concentrations [1].

- Validation: Select promising combinations from the Pareto front for experimental validation in the target cancer cell line and a healthy cell model to confirm selectivity.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MOO in Anti-Cancer Research

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors (e.g., LipoaffinityIndex, MLogP, nHBAcc) [24] | Quantitative representations of molecular structure and properties used as inputs for QSAR models. | Feature selection and model building for predicting biological activity and ADMET properties. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [24] | A game-theoretic approach to explain the output of machine learning models; identifies the contribution of each descriptor. | Interpreting complex QSAR models and performing supervised feature selection. |

| CatBoost / LightGBM [23] [24] | High-performance, gradient-boosting machine learning algorithms designed to handle categorical features and large datasets efficiently. | Constructing accurate QSAR regression and classification models for relation mapping. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [24] | A computational optimization method inspired by social behavior, which iteratively improves candidate solutions. | Solving multi-objective optimization problems to find optimal molecular descriptor ranges. |

| Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm (MOEA) [23] | A population-based optimization algorithm inspired by natural selection, capable of finding a diverse set of non-dominated solutions. | Approximating the full Pareto Front in complex multi-objective problems. |

| Smina [28] | A software for molecular docking, used to predict the binding affinity and orientation of a small molecule to a target protein. | Evaluating one key objective: the binding affinity (docking score) of generated molecules. |

| Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) [28] [29] | A combinatorial search algorithm that guides molecular generation by balancing exploration and exploitation based on Pareto dominance. | De novo generation of novel molecular structures directly on the Pareto Front for multiple properties. |

Building the Framework: Key Algorithms and Workflows for MOO

In the field of anticancer drug discovery, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a powerful tool for investigating the correlation between the chemical properties and biological activities of molecules [30]. These models rely on molecular descriptors, which are numerical representations of a molecule's physical, chemical, structural, and geometric properties [30]. However, the high-dimensional nature of descriptor data, often comprising hundreds or thousands of features, introduces significant complexity into model development and analysis [30] [23]. This challenge underscores the critical importance of data preprocessing and feature selection in building robust, interpretable, and efficient QSAR models. Within the context of multi-objective optimization for anticancer compound libraries, the identification of a critical, minimized descriptor subset is not merely a preliminary step but a fundamental process that enables the simultaneous optimization of multiple, often competing, objectives such as high biological activity (e.g., low IC₅₀) and favorable ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties [23]. This protocol outlines a comprehensive workflow for preprocessing molecular descriptor data and selecting the most informative features to enhance model performance and facilitate multi-objective optimization in anticancer research.

Application Notes

The Role of Feature Selection in QSAR Modeling

Feature selection techniques are essential for improving the accuracy and efficiency of machine learning algorithms by identifying the subset of relevant features that significantly influence the target biological response [30]. In the context of multi-objective optimization, the goal extends beyond predicting a single activity to balancing multiple compound characteristics. For instance, in anti-breast cancer drug development, researchers must simultaneously consider biological activity (PIC₅₀) and a suite of ADMET properties [23]. A well-selected feature set reduces model complexity, mitigates overfitting, and provides clearer insights into the structural elements governing both efficacy and safety, thereby directly informing the multi-objective optimization process.

Comparative Performance of Preprocessing Methods

Different feature selection methods offer varying advantages. Studies comparing filtering methods like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and wrapper methods such as Forward Selection (FS), Backward Elimination (BE), and Stepwise Selection (SS) have demonstrated that FS, BE, and SS, particularly when coupled with nonlinear regression models, exhibit promising performance in assessing anti-cathepsin activity [30]. Furthermore, novel approaches like unsupervised feature selection based on spectral clustering (FSSC) have been proposed to select features with less redundancy and more comprehensive information expression capability, which is crucial for holistic compound evaluation [23].

Table 1: Comparison of Feature Selection Methods in QSAR Modeling

| Method Type | Examples | Key Characteristics | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Pearson Correlation, F-score [31] | Faster, model-agnostic, uses statistical measures. | Reduces redundancy; effective for high-dimensional initial filtering [31]. |

| Wrapper Methods | Forward Selection, Backward Elimination, Stepwise Selection [30] | Computationally expensive, uses model performance, avoids overfitting. | Promising performance with nonlinear models for activity prediction [30]. |

| Advanced Methods | Unsupervised Spectral Clustering [23] | Reduces feature redundancy, captures comprehensive information. | Selects features with stronger expressive ability for multi-objective tasks [23]. |

| Embedded Methods | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) [30] [31] | Combines model fitting with feature selection, model-specific. | Selects high-ranked features; used for optimal descriptor subset identification [31]. |

Experimental Protocols

Data Cleaning and Preprocessing

The initial phase focuses on ensuring data quality by identifying and removing noisy or uninformative data.

- Handle Missing Data: Identify descriptors with missing values across the compound library. Depending on the extent of missingness, either impute values using appropriate methods (e.g., mean/median) or remove the descriptor from the dataset.

- Remove Low-Variance Features: Apply a variance threshold algorithm to remove descriptors with zero or near-zero variance (i.e., features with the same or nearly the same value across all drug compounds). These features contribute little to differentiating between compounds [31].

- Data Structure Verification: Ensure the data is structured in a tabular format where each row represents a unique compound and each column represents a molecular descriptor or a target property (e.g., IC₅₀, ADMET endpoints) [32]. Verify the granularity and unique identification of each record.

Feature Selection Workflow

This protocol details a multi-stage feature selection process to arrive at an optimal subset of molecular descriptors.

Filter-Based Redundancy Reduction:

- Objective: Eliminate redundant and irrelevant descriptors based on statistical measures.

- Procedure: a. Compute the Pearson Correlation Coefficient matrix between all pairs of molecular descriptors [31]. b. Identify pairs of descriptors with a mutual correlation coefficient exceeding a predefined threshold (e.g., 0.9) [31]. c. From each highly correlated pair, remove one descriptor to reduce multicollinearity. The choice can be based on prior knowledge or simplicity.

- Output: A reduced dataset with lower feature redundancy.

Feature Ranking:

- Objective: Rank the remaining descriptors by their individual importance to the target variable(s).

- Procedure: a. Implement a ranking algorithm such as the F-score algorithm [31]. b. The F-score calculates the importance of each feature based on its correlation with the target label, without considering mutual information among the features themselves [31].

- Output: A ranked list of molecular descriptors.

Advanced Subset Selection via Wrapper or Clustering Methods:

- This step can be approached using one of two advanced methods:

- A. Wrapper Method: Recursive Feature Elimination and Cross-Validation (RFECV):

- Objective: To select the best-performing subset of features by iteratively training a model and pruning the least important features [31].

- Procedure: a. Train a supervised learning estimator (e.g., SVM linear classifier) using all features from the ranked list [31]. b. Recursively eliminate a low percentage of the least important features (e.g., 5%) in each iteration [31]. c. Use 10-fold cross-validation to evaluate model performance and select the optimal feature subset that yields the best predictive performance [31].

- B. Unsupervised Method: Spectral Clustering Selection:

- Objective: To select features with minimal redundancy and comprehensive information expression capability, which is valuable for multi-objective optimization [23].

- Procedure: a. Compute a feature correlation matrix using multiple metrics (e.g., correlation coefficient, cosine similarity, grey correlation degree) to mine hidden relationships from multiple perspectives [23]. b. Use a spectral clustering algorithm to cluster the correlation matrix, grouping highly correlated features together [23]. c. Within each cluster, calculate the importance of a feature as the sum of the weights of the edges connected to it. Select the most important feature from each cluster [23].

- A. Wrapper Method: Recursive Feature Elimination and Cross-Validation (RFECV):

- Output: A final optimized subset of molecular descriptors for model training and multi-objective optimization.

- This step can be approached using one of two advanced methods:

Figure 1: Feature Selection and Preprocessing Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Software for Descriptor Preprocessing and Selection

| Item/Resource | Function/Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn Library [31] | An open-source machine learning library for Python. | Provides implementations for variance threshold, correlation analysis, F-score, RFECV, and spectral clustering [31]. |

| Python/R Programming Environment | Environments for statistical computing and data analysis. | Used for scripting the entire data preprocessing and feature selection pipeline, offering flexibility and control. |

| Molecular Descriptor Software (e.g., DRAGON, PaDEL) | Software to calculate molecular descriptors from compound structures. | Generates the initial, high-dimensional descriptor matrix that serves as the input for this protocol. |

| CatBoost Algorithm [23] | A high-performance gradient boosting algorithm. | Can be used for the relation mapping between descriptors and biological activities/ADMET properties after feature selection [23]. |

| Multi-objective Optimization Algorithms (e.g., AGE-MOEA, NSGA-II) [23] | Algorithms for solving optimization problems with multiple conflicting objectives. | Utilizes the final descriptor subset to identify compounds optimally balancing efficacy and safety [23]. |

Integration with Multi-Objective Optimization

The ultimate goal of this detailed preprocessing is to enable effective multi-objective optimization (MOO). In MOO for anticancer compound libraries, the conflict between objectives like high potency (maximizing PIC₅₀) and low toxicity (a favorable ADMET profile) is a central challenge [23]. The selected molecular descriptors define the search space for the optimization algorithm. For example, after selecting critical descriptors, a multi-objective optimization problem can be formulated as shown in Equation 1 [23]:

Figure 2: From Descriptors to Multi-Objective Optimization.

The output of the MOO is a set of Pareto-optimal solutions—compounds where no objective can be improved without worsening another [23] [1]. This allows researchers to make informed decisions on candidate drug selection by considering the inherent trade-offs. This integrated approach has been successfully applied to identify cancer-selective therapies, maximizing therapeutic effect on cancer cells while minimizing non-selective effects as a surrogate for toxicity [1].

In the field of anticancer compound research, the efficient and accurate prediction of complex biological outcomes—such as drug synergy, solubility, and efficacy—is paramount. The high-dimensional, heterogeneous, and often categorical nature of pharmaceutical data, encompassing chemical structures, genomic profiles, and high-throughput screening results, presents a significant challenge for traditional statistical models. Machine learning, particularly advanced tree-based ensemble methods, has emerged as a powerful tool to navigate this complexity, offering robust predictive performance crucial for multi-objective optimization in compound library design.

This application note provides a detailed comparative analysis of four prominent ensemble algorithms—LightGBM, XGBoost, Random Forest (RF), and CatBoost—framed within the context of anticancer drug development. We summarize their quantitative performance across various biomedical tasks, provide standardized experimental protocols for their application, and visualize their integration into a typical drug discovery workflow. The objective is to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the practical knowledge to select and implement the most appropriate algorithm for their specific predictive modeling challenges.

Algorithm Comparison and Quantitative Performance

Understanding the core characteristics and relative performance of each algorithm is the first step in model selection. The following table summarizes their key attributes and empirical results from recent studies.

Table 1: Algorithm Overview and Key Characteristics

| Algorithm | Core Principle | Key Strengths | Ideal Use Cases in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Bagging: Builds many independent decision trees and averages their predictions [33]. | Robust against overfitting, handles high dimensionality well, good for mixed data types [33]. | An all-rounder for initial exploratory modeling and complex datasets [33]. |

| XGBoost | Boosting: Builds trees sequentially, each correcting errors of its predecessor [34]. | High predictive accuracy, fast execution, built-in regularization [33]. | Competitions and tasks requiring top predictive performance on structured/tabular data [33]. |

| LightGBM | Boosting: Uses leaf-wise tree growth and histogram-based methods [34]. | Fastest training speed and low memory usage, capable of handling large-scale data [33] [35]. | Large-scale data (e.g., high-throughput screening results) where computational speed is crucial [33]. |

| CatBoost | Boosting: Uses symmetric trees and ordered boosting to handle categorical data [36]. | Superior handling of categorical features without extensive preprocessing, reduces overfitting [36] [33]. | Datasets rich in categorical variables (e.g., drug targets, cell line identifiers) and ranking tasks [36] [33]. |

Table 2: Comparative Performance Metrics Across Various Studies

| Application Domain | Performance Metric | CatBoost | XGBoost | LightGBM | Random Forest | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrusion Detection (WSN) [37] | R² | 0.9998 | - | - | - | CatBoost optimized with PSO. |

| MAE | 0.6298 | - | - | - | ||

| Anticancer Drug Synergy Prediction [38] [39] | ROC AUC | 0.9217 | - | - | - | Outperformed DNN, XGBoost, and Logistic Regression. |

| MSE | 0.1365 | - | - | - | ||

| Drug Solubility in SC-CO₂ [40] | R² (Test) | 0.9795 | - | - | - | CNN performed best (0.9839); CatBoost was second. |

| Landslide Susceptibility [41] | Overall Performance | - | Better | Best | - | LightGBM & XGBoost led in all validation metrics. |

| General Benchmark (Avg. across 6 datasets) [35] | Average AUC | 0.943 | 0.936 | 0.931 | 0.925 | |

| Average Accuracy | 0.919 | 0.912 | 0.907 | 0.900 | ||

| Training Time (s) | 40.1 | 2.6 | 4.0 | 33.2 | Highlights computational efficiency differences. |

Experimental Protocols for Anticancer Research Applications

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for developing a predictive model for anticancer drug synergy, a critical task in multi-objective compound library optimization.

Protocol: Predicting Drug Synergy with CatBoost

Background: Synergistic drug combinations can improve efficacy and reduce toxicity and resistance in cancer therapy. This protocol uses features from drugs and cancer cell lines to predict synergy scores [38] [39].

Experimental Workflow:

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| NCI-ALMANAC Dataset | Provides benchmark data on drug combination synergies across cancer cell lines [38]. | Contains synergy scores for 104 drugs combined in 60 cell lines. |

| DrugComb Portal Data | A web-based resource aggregating multiple drug combination screening datasets [38]. | Used for external validation or as an alternative data source. |

| Morgan Fingerprints | Numerical representation of drug molecular structure. | Used as input features for the model; captures chemical information [39]. |

| Gene Expression Profiles | Quantitative data on RNA transcript levels in cell lines. | Describes the genomic context of the cancer cell lines (e.g., from CCLE) [39]. |

| CatBoost Library | The open-source machine learning library implementing the algorithm. | Available for Python and R; enables model construction [36]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game-theoretic method for explaining model predictions. | Identifies key features (e.g., genes, drug properties) driving synergy predictions [38] [39]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Source Data: Download the publicly available NCI-ALMANAC dataset or access data via the DrugComb portal [38].

- Compile Features: For each drug-drug-cell line triplet, assemble the following feature vectors:

- Drug Features: Encode each drug using 1024-bit Morgan fingerprints (radius 2), incorporate drug target information, and monotherapy response data [39].

- Cell Line Features: Use normalized gene expression profiles for the specific cancer cell line. Focus on cancer-related genes if dimensionality reduction is needed [39].

- Handle Missing Values: Apply appropriate imputation methods (e.g., median for numerical features) or remove instances with excessive missing data.

Feature Engineering and Data Splitting

- Categorical Features: Declare categorical feature indices to the CatBoost model. CatBoost will internally handle these using ordered target encoding, reducing preprocessing burden and risk of data leakage [36].

- Data Partitioning: Perform a stratified split of the dataset, allocating 70% for training and 30% for testing. Ensure a representative distribution of synergy scores in both sets.

Model Training and Hyperparameter Optimization

- Baseline Model: Initialize a

CatBoostRegressorwith its default parameters to establish a baseline performance [34]. - Advanced Optimization: For enhanced performance, optimize CatBoost's hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, depth, l2leafreg) using a metaheuristic algorithm like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [37].

- Training: Train the model on the training set, using an early stopping callback on a held-out validation set to prevent overfitting.

- Baseline Model: Initialize a

Model Validation and Interpretation

- Validation: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set using metrics relevant to the task: Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), R², and ROC AUC if converted to a classification problem [38] [39].

- Cross-Validation: Perform stratified 5-fold cross-validation to obtain a robust estimate of model performance and variance [39].

- Interpretation: Apply SHAP analysis to interpret the model's predictions globally and locally. This identifies the most important features (e.g., specific genes or chemical properties) and validates the model's biological plausibility [38] [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Algorithm Selection Guide

The choice of algorithm depends on the specific constraints and objectives of the research project. The following diagram and guidelines aid in this decision-making process.

- Choose CatBoost when your dataset contains numerous categorical features (e.g., cell line names, protein targets, chemical scaffolds) and you want to minimize preprocessing while achieving high accuracy. It is also a strong candidate for ranking tasks, such as prioritizing drug candidates [36] [33].

- Choose LightGBM when working with very large datasets (e.g., millions of compounds or high-dimensional omics data) and training speed or memory efficiency is a primary concern [33] [35].

- Choose XGBoost when you are aiming for the highest possible predictive accuracy on medium-sized, structured tabular data and are willing to perform manual encoding of categorical variables. It is a proven and highly reliable algorithm [33] [35].

- Choose Random Forest as a robust baseline model, especially with complex datasets or when you want a model that is less prone to overfitting without extensive parameter tuning. It is a versatile and reliable starting point [33].

Integrating these powerful machine learning algorithms into the anticancer compound research pipeline significantly enhances the capacity for predictive modeling and multi-objective optimization. CatBoost demonstrates exceptional performance in scenarios rich with categorical data and has proven highly effective in specific tasks like drug synergy prediction. LightGBM offers unparalleled speed for large-scale screening, while XGBoost remains a top contender for pure predictive accuracy on tabular data. Random Forest provides a reliable and robust baseline.

The provided protocols, comparisons, and decision framework empower scientists to make informed choices, accelerating the development of more effective and targeted cancer therapies through data-driven insights.

In the field of anti-cancer drug discovery, the process of optimizing lead compounds involves balancing multiple, often competing, objectives. Researchers aim to maximize biological activity against specific cancer targets while simultaneously ensuring favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles (ADMET properties: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) [42] [23]. Multi-objective optimization (MOO) algorithms provide a computational framework to address these challenges by identifying a set of optimal trade-off solutions, known as the Pareto front [23].

Among the various MOO approaches, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Genetic Algorithms (GAs) have demonstrated significant utility. Recent research has led to advanced versions of these algorithms, such as the improved AGE-MOEA (Adaptive Geometry Estimation-based Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm), which are specifically tailored to navigate the complex landscape of chemical space in cancer therapeutics [23]. This article provides a detailed comparison of these two algorithmic strategies, supported by experimental protocols and quantitative performance data for researchers in computational oncology and drug development.

Algorithmic Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

Mechanism: PSO is a population-based stochastic optimization technique inspired by the social behavior of bird flocking or fish schooling [42]. In PSO, a swarm of particles (potential solutions) navigates the multi-dimensional search space. Each particle adjusts its trajectory based on its own best-known position (pbest) and the best-known position in the entire swarm (gbest), moving toward optimal regions through iterative updates of its velocity and position [42].

Application in Anticancer Research: PSO has been effectively applied to optimize anti-breast cancer candidate drugs. It is typically used after constructing Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models to perform a global search for molecular structures that maximize biological activity (e.g., pIC50 values against Estrogen Receptor Alpha, ERα) while satisfying key ADMET constraints [42]. A study demonstrated that a PSO-based multi-objective optimization model successfully identified compounds with enhanced biological activity and improved ADMET properties, such as Caco-2 permeability (F1 score: 0.8905) and CYP3A4 inhibition (F1 score: 0.9733) [42].

Improved Genetic Algorithm (AGE-MOEA)

Mechanism: Genetic Algorithms are inspired by the process of natural selection. They operate on a population of potential solutions using selection, crossover (recombination), and mutation operators to evolve toward better solutions over generations [23] [43]. The improved AGE-MOEA incorporates an adaptive geometry estimation strategy to enhance its search performance in high-dimensional objective spaces. It improves upon traditional NSGA-II by offering better handling of problems where populations become non-dominated, which is common when the number of optimization objectives exceeds three [23].

Application in Anticancer Research: The improved AGE-MOEA has been deployed to solve the complex multi-objective optimization problem in anti-breast cancer candidate drug selection. It simultaneously optimizes six objectives: biological activity (pIC50) and five key ADMET properties (Caco-2, CYP3A4, hERG, HOB, MN) [23]. Experimental results confirmed that the improved algorithm achieved superior search performance compared to its predecessors, effectively identifying the value ranges of important molecular descriptors that lead to optimal drug candidates [23].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Performance of PSO and Improved AGE-MOEA in Anticancer Drug Optimization

| Feature | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Improved Genetic Algorithm (AGE-MOEA) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Inspiration | Social behavior (flocking birds) [42] | Natural selection (genetics) [23] |

| Key Operators | Velocity update, position update [42] | Selection, crossover, mutation [23] |

| Search Strategy | Follows pbest and gbest [42] | Non-dominated sorting, adaptive geometry estimation [23] |

| Primary Application in Reviewed Studies | QSAR model optimization for ERα antagonists [42] | Direct compound selection from multiple objectives [23] |

| Reported Advantages | Efficient global search, strong convergence [42] | Better handling of high-dimensional objectives, superior search performance [23] |

| Typical Output | Optimized molecular structures [42] | Pareto-optimal set of candidate compounds [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Algorithm Implementation

Protocol 1: PSO for Anti-Breast Cancer Drug Optimization

This protocol is adapted from a study that constructed a machine learning-based optimization model for anti-breast cancer candidate drugs [42].

Phase 1: Data Preprocessing and Feature Selection

- Data Cleaning: Remove molecular descriptors with all zero values from the initial set. Normalize the remaining data.

- Feature Selection: Perform grey relational analysis to select the top 200 molecular descriptors most related to biological activity (pIC50). Follow this with Spearman correlation analysis to reduce redundancy, retaining 91 features.

- Final Feature Identification: Use a Random Forest model combined with SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) value analysis to select the top 20 molecular descriptors with the greatest impact on biological activity.

Phase 2: QSAR Model Construction

- Model Training: Using pIC50 as the target variable, train multiple regression models (e.g., LightGBM, Random Forest, XGBoost) on the 20 selected features.

- Model Ensembling: Improve prediction accuracy by combining the top-performing models (LightGBM, RandomForest, XGBoost) using a stacking ensemble method. Use this final model to predict pIC50 values for target compounds.

Phase 3: ADMET Property Prediction

- Feature Selection for ADMET: Use Random Forest with Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) to select 25 important features for each of the five ADMET properties (Caco-2, CYP3A4, hERG, HOB, MN).

- Classification Models: Construct 11 machine learning classification models for each ADMET endpoint. Identify the best model for each property (e.g., LightGBM for Caco-2, XGBoost for CYP3A4 and MN).

Phase 4: Multi-Objective Optimization with PSO

- Model Integration: Construct a single-objective optimization model that aims to improve ERα biological activity while satisfying at least three ADMET properties. Select 106 feature variables highly correlated to both activity and ADMET properties.

- PSO Execution: Employ the PSO algorithm for multi-objective optimization search. Through multiple iterations, the swarm of particles converges to identify molecular configurations representing the optimal trade-offs between activity and ADMET properties. Record the best solution from each iteration.

Figure 1: PSO-based optimization workflow for anti-breast cancer drug candidates.

Protocol 2: Improved AGE-MOEA for Direct Compound Selection