Integrative Bioinformatics for Multi-Omics Data Mining: Methods, Tools, and Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of integrative bioinformatics methodologies for mining multi-omics data, addressing the critical challenges and opportunities in modern biomedical research.

Integrative Bioinformatics for Multi-Omics Data Mining: Methods, Tools, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of integrative bioinformatics methodologies for mining multi-omics data, addressing the critical challenges and opportunities in modern biomedical research. It explores foundational concepts, diverse computational strategies including machine learning and deep learning frameworks, practical troubleshooting for data integration hurdles, and validation approaches for translating findings into clinical applications. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to enable more effective extraction of biological insights from complex, high-dimensional omics datasets, with particular emphasis on precision medicine and therapeutic discovery.

The Evolution and Core Principles of Multi-Omics Integration

The field of biological sciences has undergone a fundamental transformation, evolving from a reductionist approach that studied individual molecular components to a holistic, systems-level understanding of biological complexity. This transition from single-omics investigations to integrative bioinformatics represents a pivotal advancement in how researchers decipher the intricate machinery of life, particularly in complex diseases like cancer. Where traditional single-omics approaches (focused solely on genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, or metabolomics in isolation) provided limited snapshots of biological systems, integrative bioinformatics now enables the simultaneous analysis of multiple molecular layers, revealing their dynamic interactions and collective influence on phenotype [1] [2].

This paradigm shift has been driven by both technological and computational innovations. The advent of high-throughput technologies has generated unprecedented volumes of biological data, while advances in bioinformatics, data sciences, and artificial intelligence have made integrative multiomics feasible [2]. The resulting integrated view has proven essential for understanding the sequential flow of biological information in the 'omics cascade,' where genes encode potential phenotypic traits, but protein and metabolite regulation is further influenced by physiological, pathological, and environmental factors [1]. This complex regulation makes biological systems challenging to disentangle into individual components, necessitating the integrated approaches that form the cornerstone of modern precision medicine initiatives [2].

The Single-Omics Era: Technological Foundations and Limitations

Early omics technologies provided revolutionary but isolated views of biological systems. Genomics mapped the static DNA blueprint, transcriptomics captured dynamic RNA expression patterns, proteomics identified functional protein effectors, and metabolomics revealed downstream metabolic activities. While each domain generated crucial insights, their siloed application suffered from fundamental limitations in capturing the complete biological narrative.

The primary constraint of single-omics approaches lies in their inability to establish causal relationships across molecular layers. For instance, mRNA abundance often correlates poorly with protein abundance due to post-transcriptional regulation, translational efficiency, and protein degradation mechanisms [1]. Similarly, genomic variants may not manifest phenotypically due to epigenetic modifications or compensatory metabolic pathways. This disconnect was evident in studies investigating transcription-protein correspondence, where researchers observed significant time delays between mRNA release and protein production/secretion [1].

Analytical methodologies in the single-omics era primarily relied on differential expression analysis and enrichment methods applied to individual data types. While statistically powerful for identifying changes within one molecular layer, these approaches could not determine whether upregulated genes translated to functional protein increases, or whether metabolic changes originated from genomic or environmental influences. This limitation became particularly problematic in heterogeneous systems like tumor microenvironments, where bulk measurements averaged signals across diverse cell populations, masking critical cell-type-specific relationships [3].

The Rise of Multi-Omics Integration: Technological Drivers

The transition to integrative bioinformatics was catalyzed by parallel advancements in both experimental technologies and computational infrastructure:

Measurement Technologies

Single-cell multiomics technologies fundamentally transformed resolution capabilities by simultaneously capturing transcriptional and epigenomic states at the level of individual cells [3]. Similarly, spatial transcriptomics preserved geographical context within tissues, while long-read sequencing technologies enabled more comprehensive coverage of complex genomic regions and full-length transcripts [4]. The emergence of liquid biopsies provided non-invasive access to multiple analyte types—including cell-free DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites—further expanding the scope of accessible multiomics data [4].

Computational and Analytical Advancements

The data complexity generated by multiomics technologies necessitated parallel computational innovations. Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms demonstrated particular promise for detecting intricate patterns and interdependencies across omics layers [4] [2]. Simultaneously, development of specialized bioinformatics platforms like SeekSoul Online provided user-friendly interfaces for single-cell multiomics analysis, making integrated approaches accessible to researchers without programming expertise [5]. Critical advances in cloud computing and data storage infrastructure enabled the handling of massive multiomics datasets that routinely exceed the capabilities of traditional computing resources [4].

Methodological Frameworks for Multi-Omics Integration

Integrative bioinformatics approaches can be categorized into distinct methodological frameworks based on their underlying computational principles and integration strategies.

Statistical and Correlation-Based Methods

Correlation analysis serves as a foundational approach for assessing relationships between omics datasets. Simple scatterplots visualize expression patterns, while statistical measures like Pearson's or Spearman's correlation coefficients quantify the degree of association [1]. The RV coefficient, a multivariate generalization of squared Pearson correlation, has been employed to test correlations between whole sets of differentially expressed genes across biological contexts [1].

Correlation networks extend these pairwise associations into graphical representations where nodes represent biological entities and edges indicate significant correlations. Weighted Gene Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA) identifies clusters (modules) of highly correlated, co-expressed genes that can be linked to clinically relevant traits [1]. The xMWAS platform performs pairwise association analysis by combining Partial Least Squares components and regression coefficients to generate integrative network graphs, with community detection algorithms identifying highly interconnected node clusters [1].

Table 1: Statistical Integration Methods and Applications

| Method | Key Features | Typical Application | Tools/Packages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Analysis | Quantifies pairwise relationships between omics features | Assessing transcription-protein correspondence; identifying discordant regulation | Pearson, Spearman, RV coefficient |

| WGCNA | Identifies co-expression modules; constructs scale-free networks | Linking gene modules to clinical traits; integrating transcriptomics and metabolomics | WGCNA R package |

| xMWAS | Performs multivariate association analysis; generates integrative networks | Multi-omics community detection; visualization of cross-omics relationships | xMWAS web tool |

| Procrustes Analysis | Assesses geometric similarity between datasets through transformation | Evaluating dataset alignment after integration | Procrustes R functions |

Multivariate Methods

Multivariate techniques project high-dimensional omics data into lower-dimensional spaces while preserving essential information. These methods include Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (NMF), and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression. Multivariate approaches are particularly valuable for identifying latent factors that capture shared variation across omics modalities, often revealing underlying biological processes that are not apparent when analyzing individual datasets separately.

Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

Machine learning approaches have dramatically expanded multi-omics integration capabilities. Multiple Kernel Learning (MKL) frameworks, such as the recently developed scMKL for single-cell data, merge the predictive power of complex models with the interpretability of linear approaches [3]. Deep learning architectures, particularly autoencoders, capture non-linear structure by mapping high-dimensional data into informative low-dimensional latent spaces [3]. These approaches have demonstrated superior performance in classification tasks across multiple cancer types, utilizing data from single-cell RNA sequencing, ATAC sequencing, and 10x Multiome platforms [3].

Semantic and Knowledge-Based Integration

Semantic technologies bring distinct advantages for contextualizing multi-omics findings within established biological knowledge. Ontologies provide standardized vocabularies and relationships for consistent annotation across datasets, while knowledge graphs integrate heterogeneous biological entities and their relationships into unified frameworks [6]. These approaches notably improve data visualization, querying, and management, thereby enhancing gene and pathway discovery while providing deeper disease insights [6].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Multiple Kernel Learning with scMKL for Single-Cell Multiomics

The scMKL framework exemplifies a modern approach for integrative analysis of single-cell multimodal data, combining multiple kernel learning with random Fourier features and group Lasso formulation [3].

Step 1: Input Data Preparation

- Process single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) and scATAC-seq data using standard preprocessing pipelines

- For RNA modality: Utilize Hallmark gene sets from Molecular Signature Database as prior biological knowledge

- For ATAC modality: Employ transcription factor binding sites from JASPAR and Cistrome databases

- Normalize counts but avoid extensive dimensionality reduction that may distort biological variation

Step 2: Kernel Construction

- Construct separate kernels for each modality (RNA and ATAC) using pathway-informed groupings

- Align kernel structures with the specific characteristics of RNA and ATAC data

- Use Random Fourier Features (RFF) to reduce computational complexity from O(N²) to O(N)

Step 3: Model Training and Regularization

- Implement repeated 80/20 train-test splits (100 iterations) with cross-validation

- Optimize regularization parameter λ using group Lasso formulation

- Higher λ values increase model sparsity and interpretability by selecting fewer pathways (ηᵢ≠0)

- Lower λ values capture more biological variation but may compromise generalizability

Step 4: Model Interpretation

- Extract model weights for each feature group to identify driving biological signals

- Identify key transcriptomic and epigenetic features, and multimodal pathways

- Transfer learned insights to independent datasets for validation

scMKL Experimental Workflow

Protocol: Correlation Network Analysis for Multi-Omics Integration

Correlation-based approaches provide an accessible entry point for multi-omics integration, particularly suitable for smaller-scale studies or preliminary analyses.

Step 1: Differential Expression Analysis

- Perform separate differential expression analysis for each omics dataset

- Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), proteins (DEPs), and metabolites

- Apply appropriate multiple testing corrections (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg)

Step 2: Correlation Matrix Calculation

- Compute pairwise correlations between significant features across omics layers

- Select correlation metric based on data distribution:

- Pearson's correlation for normally distributed data

- Spearman's rank correlation for non-parametric data

- Set significance thresholds for correlation coefficients and p-values (e.g., |r| > 0.7, p < 0.05)

Step 3: Network Construction and Visualization

- Construct correlation networks where nodes represent omics features

- Create edges between nodes that meet correlation thresholds

- Apply community detection algorithms to identify highly interconnected modules

- Visualize networks using cytoscape or similar tools

- Integrate with known biological networks (e.g., protein-protein interactions)

Step 4: Biological Interpretation

- Annotate network modules with functional enrichment analysis

- Identify hub nodes with high connectivity as potential key regulators

- Generate hypotheses about cross-omics regulatory mechanisms

Performance Benchmarks and Comparative Analyses

Rigorous benchmarking studies demonstrate the superior performance of integrative approaches compared to single-omics analyses. In comprehensive evaluations across multiple cancer types—including breast, prostate, lymphatic, and lung cancers—multiomics integration consistently outperformed single-modality approaches.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Multi-Omics Integration Methods

| Method | AUROC Range | Key Advantages | Limitations | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scMKL | 0.85-0.96 [3] | Interpretable feature weights; multimodal integration; scalable to single-cell data | Requires biological knowledge for kernel construction | Cancer subtyping; biomarker discovery; translational research |

| Statistical Correlation | Varies by dataset | Computational simplicity; intuitive interpretation | Limited to pairwise relationships; multiple testing burden | Preliminary analysis; hypothesis generation |

| Deep Learning (Autoencoders) | 0.82-0.94 [3] | Captures non-linear relationships; minimal feature engineering | Black-box nature; limited interpretability | Pattern recognition; clustering; predictive modeling |

| Semantic Integration | Qualitative improvements | Standardized annotations; knowledge discovery | Complex implementation; dependency on ontology quality | Knowledge discovery; data harmonization; cross-study integration |

The scMKL framework has demonstrated statistically significant superiority (p < 0.001) over other machine learning algorithms including Multi-Layer Perceptron, XGBoost, and Support Vector Machines, despite using fewer genes by leveraging biological knowledge [3]. This approach achieved better results while training 7× faster and using 12× less memory than comparable kernel methods like EasyMKL [3].

Successful multi-omics integration requires both wet-lab reagents and computational resources that form the foundation of reproducible integrative bioinformatics.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Multi-Omics Integration

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Knowledge Bases | MSigDB Hallmark Gene Sets [3] | Curated gene sets representing specific biological states | Provides prior knowledge for pathway-informed analysis |

| JASPAR/Cistrome TFBS [3] | Transcription factor binding site profiles | Guides ATAC-seq data interpretation and integration | |

| KEGG, GO Databases [1] | Pathway and functional annotation | Enables biological interpretation of integrated results | |

| Analysis Platforms | SeekSoul Online [5] | User-friendly single-cell multi-omics analysis | No programming foundation required; interactive visualization |

| xMWAS [1] | Correlation and multivariate analysis | Web-based tool for multi-omics network construction | |

| WGCNA [1] | Weighted correlation network analysis | Identifies co-expression modules across omics layers | |

| Reference Databases | Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) [2] | Population variation data | Source of putatively benign variants for interpretation |

| ClinVar, HGMD [2] | Clinical variant interpretation | Curated databases of disease-associated variants | |

| Computational Infrastructure | Cloud computing platforms [4] | Scalable data storage and analysis | Handles massive multi-omics datasets beyond local capacity |

Signaling Pathways and Biological Mechanisms Revealed Through Integration

Integrative multiomics has uncovered critical signaling pathways and regulatory mechanisms across various cancer types. In breast cancer, scMKL identified key regulatory pathways and transcription factors involved in the estrogen response by integrating RNA and ATAC modalities [3]. In prostate cancer, integrative analysis of sciATAC-seq data revealed tumor subtype-specific signaling mechanisms distinguishing low-grade versus high-grade tumors [3].

Multi-Layer Regulatory Network

The integration of multiple biological layers has been particularly transformative for understanding cancer heterogeneity and therapy resistance mechanisms. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), integrative analysis of independent scRNA-seq datasets collected under distinct protocols successfully identified biological pathways that distinguish treatment responses and molecular subtypes despite technical batch effects and class imbalance scenarios [3]. These findings highlight how multiomics integration can reveal conserved biological signals across heterogeneous datasets and experimental conditions.

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Despite significant advances, multiomics integration faces several persistent challenges that represent active research frontiers. Data heterogeneity remains a fundamental obstacle, as samples from multiple cohorts analyzed in different laboratories create harmonization issues that complicate integration [4]. The high-throughput nature of omics platforms introduces variable data quality, missing values, collinearity, and dimensionality concerns that intensify when combining datasets [1]. Significant computational barriers include the need for appropriate computing and storage infrastructure specifically designed for multiomic data [4].

Future developments will likely focus on several key areas. Improved standardization through robust methodologies and protocols for data integration is crucial for ensuring reproducibility and reliability [4]. Advanced AI and machine learning approaches will continue to evolve, with particular emphasis on enhancing interpretability while maintaining predictive power [3] [4]. Federated computing frameworks will enable collaborative analysis while addressing privacy concerns, especially for clinical applications [4]. Finally, increased attention to population diversity in genomic research is essential to address health disparities and ensure biomarker discoveries are broadly applicable across ancestral groups [2].

The trajectory from single-omics to integrative bioinformatics represents more than a technical evolution—it constitutes a fundamental shift in biological inquiry. By transcending traditional disciplinary boundaries and embracing computational innovation, integrative approaches are revealing the profound complexity of biological systems while generating actionable insights for precision medicine. As these methodologies mature and overcome existing challenges, they promise to accelerate the translation of molecular discoveries into improved human health outcomes across diverse populations.

The advent of high-throughput technologies has revolutionized biology, enabling comprehensive measurement of biological systems at various molecular levels. Multi-omics integration combines data from different omics layers—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—to provide a holistic view of biological processes that cannot be captured by single-omics analyses alone [7]. This integrated approach is transforming biomedical research by revealing previously unknown relationships between different molecular components and facilitating the identification of biomarkers and therapeutic targets for various diseases [7].

The core challenge in multi-omics research lies in effectively integrating these diverse data types, each with unique scales, noise ratios, and preprocessing requirements [8]. For instance, the correlation between mRNA expression and protein abundance is not always straightforward, as the most abundant protein may not correlate with high gene expression due to post-transcriptional regulation [8]. This disconnect, along with technical challenges like missing data and batch effects, makes integration a complex but essential task for advancing systems biology.

Core Omics Technologies and Their Relationships

Defining the Omics Layers

Biological information flows from genetic blueprint to functional molecules through distinct yet interconnected molecular layers:

Transcriptomics measures the expression levels of RNA transcripts, serving as an indirect measure of DNA activity and representing upstream processes of metabolism [7]. It captures the complete set of RNA transcripts in a cell or tissue, including both coding and non-coding RNAs.

Proteomics focuses on the identification and quantification of proteins, which are the functional products of genes and play critical roles in cellular processes, including maintaining cellular structure and facilitating direct interactions among cells and tissues [7]. Proteins typically have molecular weights >2 kDa.

Metabolomics comprehensively analyzes small molecules (≤1.5 kDa) that serve as intermediate or end products of metabolic reactions and regulators of metabolism [7]. The metabolome represents the ultimate mediators of metabolic processes and provides the most dynamic readout of cellular activity.

Table 1: Core Omics Technologies and Their Characteristics

| Omics Layer | Molecules Measured | Key Technologies | Molecular Weight Range | Biological Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics | RNA transcripts (mRNA, non-coding RNA) | RNA-seq, Microarrays | Varies | Indirect measure of DNA activity, upstream metabolic processes |

| Proteomics | Proteins and enzymes | LC-MS/MS, Antibody arrays | >2 kDa | Functional gene products, cellular structure and communication |

| Metabolomics | Metabolites (intermediate/end products) | LC-MS/MS, GC-MS | ≤1.5 kDa | Metabolic regulators, ultimate mediators of metabolic processes |

Information Flow Through Biological Systems

The relationship between these omics layers follows the central dogma of molecular biology while incorporating regulatory feedback mechanisms. Transcriptomics captures how genetic information is transcribed, proteomics identifies the functional effectors, and metabolomics reveals the ultimate biochemical outcomes that can feedback to regulate gene expression and protein function.

Strategies for Multi-Omics Data Integration

Computational Integration Approaches

Multi-omics integration methods can be categorized into three major approaches, each with distinct strengths and applications:

Combined Omics Integration attempts to explain what occurs within each type of omics data in an integrated manner while generating independent data sets. This approach maintains the integrity of each omics data type while enabling comparative analysis [7].

Correlation-Based Integration Strategies apply statistical correlations between different types of generated omics data and create data structures such as networks to represent these relationships. These methods include gene co-expression analysis, gene-metabolite networks, and similarity network fusion [7].

Machine Learning Integrative Approaches utilize one or more types of omics data, potentially incorporating additional information inherent to these datasets, to comprehensively understand responses at classification and regression levels, particularly in relation to diseases [7]. These methods can identify complex patterns and interactions that might be missed by conventional statistical approaches.

Horizontal, Vertical, and Diagonal Integration

The structural approach to integration depends on how samples are matched across omics layers:

Vertical Integration (Matched): Merges data from different omics within the same set of samples, using the cell as an anchor to bring these omics together. This approach requires technologies that profile multiple omics data from two or more distinct modalities from within a single cell [8].

Diagonal Integration (Unmatched): Integrates different omics from different cells or different studies, requiring derivation of anchors through co-embedded spaces where commonality between cells is found [8].

Mosaic Integration: An alternative to diagonal integration used when experiments have various combinations of omics that create sufficient overlap across samples [8].

Table 2: Multi-Omics Integration Tools and Their Applications

| Tool Name | Year | Methodology | Integration Capacity | Data Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA+ | 2020 | Factor analysis | mRNA, DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility | Matched |

| Seurat v4 | 2020 | Weighted nearest-neighbour | mRNA, spatial coordinates, protein, accessible chromatin | Matched |

| totalVI | 2020 | Deep generative | mRNA, protein | Matched |

| GLUE | 2022 | Variational autoencoders | Chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation, mRNA | Unmatched |

| LIGER | 2019 | Integrative non-negative matrix factorization | mRNA, DNA methylation | Unmatched |

| Cobolt | 2021 | Multimodal variational autoencoder | mRNA, chromatin accessibility | Mosaic |

| StabMap | 2022 | Mosaic data integration | mRNA, chromatin accessibility | Mosaic |

Experimental Design and Methodological Frameworks

Reference Materials and Quality Control

The Quartet Project provides a framework for quality assessment in multi-omics studies by offering multi-omics reference materials and reference datasets for QC and data integration. This initiative developed publicly available multi-omics reference materials of matched DNA, RNA, protein, and metabolites derived from immortalized cell lines from a family quartet of parents and monozygotic twin daughters [9].

These reference materials provide built-in truth defined by:

- Relationships among family members (Mendelian inheritance patterns)

- Information flow from DNA to RNA to protein (central dogma)

- Ability to classify samples into correct familial relationships [9]

The project introduced a ratio-based profiling approach that scales absolute feature values of study samples relative to those of a concurrently measured common reference sample, producing reproducible and comparable data suitable for integration across batches, labs, platforms, and omics types [9].

Case Study: Integrated Analysis of LPS-Treated Cardiomyocytes

A comprehensive multi-omics study demonstrates the practical application of integration methodologies to investigate the role of lncRNA rPvt1 in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated H9C2 cardiomyocytes [10]:

Experimental Design:

- Established LPS-induced cardiomyocyte injury model

- Achieved lncRNA rPvt1 silencing using lentiviral transduction system

- Performed transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic assays

- Conducted integrated multi-omics analysis

Methodological Details:

Transcriptomic Analysis:

- Total RNA quantification using Qubit RNA detection kit

- Sequencing libraries constructed with Hieff NGS MaxUp Dual-mode mRNA Library Prep Kit

- RNA enriched with oligo(dT) magnetic beads and fragmented

- Illumina HiSeq platform sequencing

- Differential expression analysis using DESeq R package (q < 0.05 and log₂|fold-change| > 1) [10]

Proteomic Analysis:

- Total protein quantification using BCA kit

- Protein digestion with trypsin into peptides

- Peptide separation using homemade reversed-phase analytical column

- Mass spectrometry using timsTOF Pro in parallel accumulation serial fragmentation mode

- MS/MS data processing using MaxQuant search engine [10]

Multi-Omics Workflow Integration:

Analytical Techniques for Data Integration

Correlation-Based Integration Methods

Correlation-based strategies involve applying statistical correlations between different omics data types to uncover and quantify relationships between molecular components:

Gene Co-Expression Analysis with Metabolomics Data:

- Perform co-expression analysis on transcriptomics data to identify gene modules

- Link these modules to metabolites from metabolomics data

- Identify metabolic pathways co-regulated with identified gene modules

- Calculate correlation between metabolite intensity patterns and module eigengenes [7]

Gene-Metabolite Network Construction:

- Collect gene expression and metabolite abundance data from same biological samples

- Integrate data using Pearson correlation coefficient analysis

- Identify genes and metabolites that are co-regulated or co-expressed

- Construct networks using visualization software like Cytoscape or igraph [7]

- Represent genes and metabolites as nodes with edges representing relationship strength

Knowledge Graphs and Advanced Data Structures

Knowledge graphs are gaining popularity for structuring multi-omics data, representing biological entities as nodes (genes, proteins, metabolites, diseases, drugs) and their relationships as edges (protein-protein interactions, gene-disease associations, metabolic pathways) [11].

The GraphRAG approach enhances retrieval by combining entity-aware graph traversal with semantic embeddings, enabling connections between genes to pathways, clinical trials, and drug targets that are difficult to achieve with text-only retrieval [11]. This approach:

- Converts unstructured and multi-modal data into knowledge graphs

- Retrieves documents with structured graph evidence for more accurate responses

- Enables transparent reasoning chains by anchoring outputs in verified graph-based knowledge

- Reduces hallucinations in AI-generated content [11]

Applications in Biomedical Research

Disease Subtyping and Classification

Multi-omics integration has proven particularly valuable for identifying disease subtypes and classifying samples into subgroups to understand disease etiology and select effective treatments. In one case study, iClusterPlus identified 12 distinct clusters by combining profiles of 729 cancer cell lines across 23 tumor types from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia [11].

The analysis revealed that while many cell lines grouped by their cell-of-origin, several subgroups were potentially created by mutual genetic alteration. For example, one cluster belonged to NSCLC and pancreatic cancer cell lines linked through detection of KRAS mutations [11].

Biomarker Discovery and Drug Development

Multi-omics approaches have shown significant advantages in biomarker prediction for many diseases including cancer, stroke, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and COVID-19 [11]. The integration of various omics information has great potential to guide targeted therapy:

- A single chemical proteomics strategy identified 14 possible targets, but simultaneous combination with targeted metabolomics enabled identification of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 and 2 as correct binding targets [11].

- Multi-omics integration accelerates drug development by improving therapeutic strategies, predicting drug sensitivity, and enabling drug repurposing through uncovering new mechanisms of action and potential synergies with other treatments [11].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Quartet Project Reference Materials (DNA, RNA, protein, metabolites) | Quality control, batch effect correction, method validation | Derived from family quartet enabling built-in truth validation [9] |

| Cell Lines | H9C2 cardiomyocytes, HEK293FT, B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) | Disease modeling, lentivirus production, multi-omics profiling | Immortalized cells providing consistent biological material [10] [9] |

| Library Prep Kits | Hieff NGS MaxUp Dual-mode mRNA Library Prep Kit | Transcriptomic library construction for Illumina platforms | Oligo(dT) magnetic bead enrichment, fragmentation compatibility [10] |

| Quantification Assays | Qubit RNA detection kit, BCA protein assay | Accurate biomolecule quantification before downstream analysis | RNA-specific and protein-specific quantification methods [10] |

| Analysis Software | MaxQuant, DESeq, Cytoscape, Seurat, MOFA+ | Data processing, differential analysis, visualization | Specialized tools for each omics type and integration [7] [8] [10] |

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, multi-omics integration faces several substantial challenges:

Technical and Analytical Challenges:

- Data heterogeneity: Omics technologies have different precision levels and signal-to-noise ratios that affect statistical power [11]

- Scalability and storage: High storage and processing needs with most existing analysis pipelines built for smaller datasets [11]

- Statistical power imbalance: Collecting equal numbers of samples results in different power across omics [11]

- Reproducibility and standardization: Many results fail replication due to practices like HARKing (hypothesizing after results are known) [11]

Emerging Solutions:

- Ratio-based profiling: Scaling absolute feature values relative to common reference samples to improve reproducibility [9]

- Knowledge graphs: Explicitly representing relationships between biological entities for improved integration [11]

- Automated curation: Reducing manual data preparation through automated annotation and validation pipelines [12]

The field continues to evolve with new computational approaches and reference materials that address these challenges, paving the way for more robust and reproducible multi-omics studies that can accelerate discoveries in basic biology and translational medicine.

The Biological Hierarchy of Omics Layers and Their Dynamic Relationships

The comprehension of complex biological systems necessitates an integrative approach that considers the multiple molecular layers constituting an organism. The biological hierarchy of omics layers represents the flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA to proteins and metabolites, culminating in the phenotypic expression of a cell or tissue. This hierarchy begins with the genome, which provides the foundational blueprint, and progresses to the epigenome, responsible for regulating gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. The transcriptome encompasses the complete set of RNA transcripts, reflecting actively expressed genes, while the proteome represents the functional effectors—the proteins that execute cellular processes. Finally, the metabolome comprises the end-products of cellular regulatory processes, offering a dynamic snapshot of the cell's physiological state [7].

In the era of high-throughput technologies, the field of omics has made significant strides in characterizing biological systems at these various levels of complexity. However, analyzing each omics dataset in isolation fails to capture the intricate interactions and regulatory relationships between these layers. Integrative multi-omics has thus emerged as a critical paradigm in bioinformatics and systems biology, enabling researchers to reconstruct a more comprehensive picture of biological systems by simultaneously considering multiple molecular dimensions [8] [7]. This holistic approach is particularly valuable for understanding complex diseases and advancing drug discovery, where interventions often target specific nodes within these interconnected networks.

The dynamic relationships between omics layers are governed by complex regulatory mechanisms that remain only partially understood. For instance, while open chromatin accessibility typically promotes active transcription, gene expression responses may not be directly coordinated with chromatin changes due to various biological regulatory factors. Similarly, the most abundant proteins may not always correlate with high gene expression due to post-transcriptional and post-translational regulation [8] [13]. Disentangling these complex, time-dependent relationships requires sophisticated computational frameworks that can model both the hierarchical structure and the dynamic interactions between omics layers.

The Omics Hierarchy: From DNA to Phenotype

Defining the Omics Layers

The foundational layers of biological information form a complex, interconnected hierarchy where each level contributes uniquely to cellular function and phenotype. The table below summarizes the key omics layers, their molecular components, and the technologies used to measure them.

Table 1: The Biological Hierarchy of Omics Layers

| Omics Layer | Molecular Components | Measurement Technologies | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequence, structural variants | Whole genome sequencing, exome sequencing | Provides genetic blueprint and inherited information |

| Epigenomics | DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin accessibility | ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, WGBS | Regulates gene expression without changing DNA sequence |

| Transcriptomics | mRNA, non-coding RNA | RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq | Acts as intermediary between DNA and protein, reflects actively expressed genes |

| Proteomics | Proteins, peptides (>2 kDa) | Mass spectrometry, LC-MS/MS | Functional effectors executing cellular processes |

| Metabolomics | Metabolites (≤1.5 kDa) | NMR, LC-MS, GC-MS | End-products of metabolic processes, dynamic physiological snapshot |

This hierarchy operates not as a simple linear pathway but as a complex network with extensive feedback and feedforward regulation. For example, the epigenome modulates transcriptome activity through mechanisms such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, while metabolites can influence epigenetic marks through metabolic co-factors, creating bidirectional regulatory loops [7]. Similarly, proteins and metabolites participate in complex interactions that ultimately determine cellular phenotype and response to environmental stimuli.

Dynamic Relationships Between Layers

The relationships between omics layers are characterized by both coupled and decoupled dynamics. In coupled relationships, changes in one omics layer directly correlate with changes in another over time. For instance, increased chromatin accessibility at gene promoters often correlates with enhanced transcription of those genes. In decoupled relationships, changes occur independently between layers due to various biological regulatory factors [13].

The HALO framework exemplifies how these dynamic relationships can be modeled computationally. It factorizes transcriptomics and epigenomics data into both coupled and decoupled latent representations, revealing their dynamic interplay. In this model:

- Coupled representations ((Z_c)) capture information where gene expression changes are dependent on chromatin accessibility dynamics over time, reflecting shared information across modalities.

- Decoupled representations ((Z_d)) extract information where gene expression changes independently of chromatin accessibility over time, emphasizing modality-specific information [13].

These dynamic relationships are further complicated by temporal factors, as changes in chromatin accessibility often precede changes in gene expression, creating time-lagged correlations that must be accounted for in integrative analyses.

Computational Frameworks for Multi-Omics Integration

Integration Strategies and Methodologies

The integration of multi-omics data presents significant computational challenges due to differences in data scale, noise characteristics, and biological meaning across omics layers. Three primary integration strategies have emerged, each with distinct approaches and applications.

Table 2: Multi-Omics Integration Strategies

| Integration Type | Data Characteristics | Key Methods | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical (Matched) | Multiple omics measured from the same cells | Seurat v4, MOFA+, totalVI, SCENIC+ | Cell type identification, regulatory network inference, cellular trajectory mapping |

| Diagonal (Unmatched) | Different omics from different cells/samples | GLUE, LIGER, Pamona, BindSC | Cross-study comparison, integration of legacy datasets, sample-level biomarker discovery |

| Mosaic | Various omic combinations across samples with sufficient overlap | COBOLT, MultiVI, StabMap | Integration of diverse experimental designs, leveraging partially overlapping datasets |

Vertical integration, also known as matched integration, leverages technologies that profile multiple omic modalities from the same single cell. The cell itself serves as the natural anchor for integration in this approach. Methods for vertical integration include matrix factorization approaches (e.g., MOFA+), neural network-based methods (e.g., scMVAE, DCCA), and network-based methods (e.g., Seurat v4) [8].

Diagonal integration addresses the more challenging scenario of integrating omics data drawn from distinct cell populations. Since the cell cannot be used as an anchor in this case, methods like GLUE (Graph-Linked Unified Embedding) project cells into a co-embedded space or non-linear manifold to find commonality between cells across different omics modalities [8].

Mosaic integration represents an alternative approach that can be employed when experimental designs feature various combinations of omics that create sufficient overlap. For example, if one sample was assessed for transcriptomics and proteomics, another for transcriptomics and epigenomics, and a third for proteomics and epigenomics, there is enough commonality between these samples to integrate the data using tools like COBOLT and MultiVI [8].

Network-Based Integration Methods

Network-based approaches have emerged as powerful tools for multi-omics integration due to their ability to naturally represent complex biological relationships. These methods can be categorized into four primary types:

Network Propagation/Diffusion: These methods, including CellWalker2, leverage graph diffusion models to propagate information across biological networks, enabling the annotation of cells, genomic regions, and gene sets while assessing statistical significance [14] [15].

Similarity-Based Approaches: Methods such as Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) construct similarity networks for each omics data type separately, then merge these networks to identify robust multi-omics patterns [7] [15].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Deep learning approaches that operate directly on graph-structured data, capable of learning complex patterns across multiple omics layers [15].

Network Inference Models: These include methods like weighted nodes networks (WNNets), which incorporate experimental data at the node level to create condition-specific networks, allowing the integration of quantitative measurements into network analysis [16].

CellWalker2 exemplifies the advancement in network-based integration methods. It constructs a heterogeneous graph that integrates cells, cell types, and genomic regions of interest, then performs random walks with restarts on this graph to compute influence scores. This approach enables the comparison of cell-type hierarchies across different contexts, such as species or disease states, while incorporating hierarchical relationships between cell types [14].

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Analysis

Protocol 1: Causal Relationship Analysis with HALO

The HALO framework provides a comprehensive protocol for analyzing causal relationships between chromatin accessibility and gene expression in single-cell multi-omics data.

Input Requirements:

- Paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data from the same cells

- Temporal information (real time points or estimated latent time)

Methodological Steps:

Data Preprocessing: Normalize scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq count matrices using standard single-cell preprocessing pipelines.

Representation Learning: Employ two distinct encoders to derive latent representations Z^A (ATAC-seq) and Z^R (RNA-seq).

Causal Factorization: Factorize the latent representations into coupled and decoupled components:

- ATAC-seq: (Z^A = [Zc^A, Zd^A])

- RNA-seq: (Z^R = [Zc^R, Zd^R])

Constraint Application:

- Apply coupled constraints to align (Zc^A) and (Zc^R)

- Apply decoupled constraints to enforce independent functional relations between (Zd^A) and (Zd^R)

Interpretation: Use a nonlinear interpretable decoder to decompose the reconstruction of genes or peaks into additive contributions from individual representations.

Gene-Level Analysis: Apply negative binomial regression to correlate local peaks with gene expression, calculating couple and decouple scores for individual genes.

Granger Causality Analysis: Explore underlying mechanisms of distal peak-gene regulatory interactions to identify instances where local peaks increase without corresponding changes in gene expression [13].

Protocol 2: Correlation-Based Integration for Transcriptomics and Metabolomics

This protocol enables the integration of transcriptomics and metabolomics data to identify key genes and metabolic pathways involved in specific biological processes.

Input Requirements:

- Gene expression data (transcriptomics)

- Metabolite abundance data (metabolomics)

- Samples from the same biological conditions

Methodological Steps:

Data Normalization: Normalize both transcriptomics and metabolomics datasets using appropriate methods (e.g., TPM for RNA-seq, Pareto scaling for metabolomics).

Co-expression Analysis: Perform weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) on transcriptomics data to identify modules of co-expressed genes.

Module Characterization: Calculate module eigengenes (representative expression profiles) for each co-expression module.

Integration with Metabolomics: Correlate module eigengenes with metabolite intensity patterns to identify metabolites associated with each gene module.

Network Construction: Generate gene-metabolite networks using visualization tools like Cytoscape, with edges representing significant correlations between genes and metabolites.

Functional Interpretation: Conduct pathway enrichment analysis on genes within significant modules to identify biological processes linking transcriptional and metabolic changes [7].

Protocol 3: Hierarchical Cell-Type Mapping with CellWalker2

This protocol enables the annotation and mapping of multi-modal single-cell data using hierarchical cell-type relationships.

Input Requirements:

- Count matrices from scRNA-seq (gene by cell) and/or scATAC-seq (peak by cell)

- Cell type ontologies with marker genes for each leaf node

- Optional: genomic regions of interest (e.g., genetic variants, regulatory elements)

Methodological Steps:

Graph Construction: Build a heterogeneous graph that integrates:

- Cell nodes with scATAC-seq, scRNA-seq, or multi-omics data

- Label nodes with predefined marker genes

- Annotation nodes with genomic coordinates or gene names

Edge Definition: Compute edges based on:

- Cell-to-cell: nearest neighbors in genome-wide similarity

- Cell-to-label: expression/accessibility of marker genes in each cell

- Annotation-to-cell: accessibility of genomic regions or expression of genes

Random Walk with Restarts: Perform graph diffusion to compute influence scores between all node types.

Statistical Significance Estimation: Perform permutations to estimate Z-scores for learned associations.

Cross-Context Comparison: Utilize label-to-label similarities to compare cell-type ontologies across different contexts (e.g., species, disease states) [14].

Visualization and Analysis of Multi-Omics Relationships

Causal Relationship Modeling Workflow

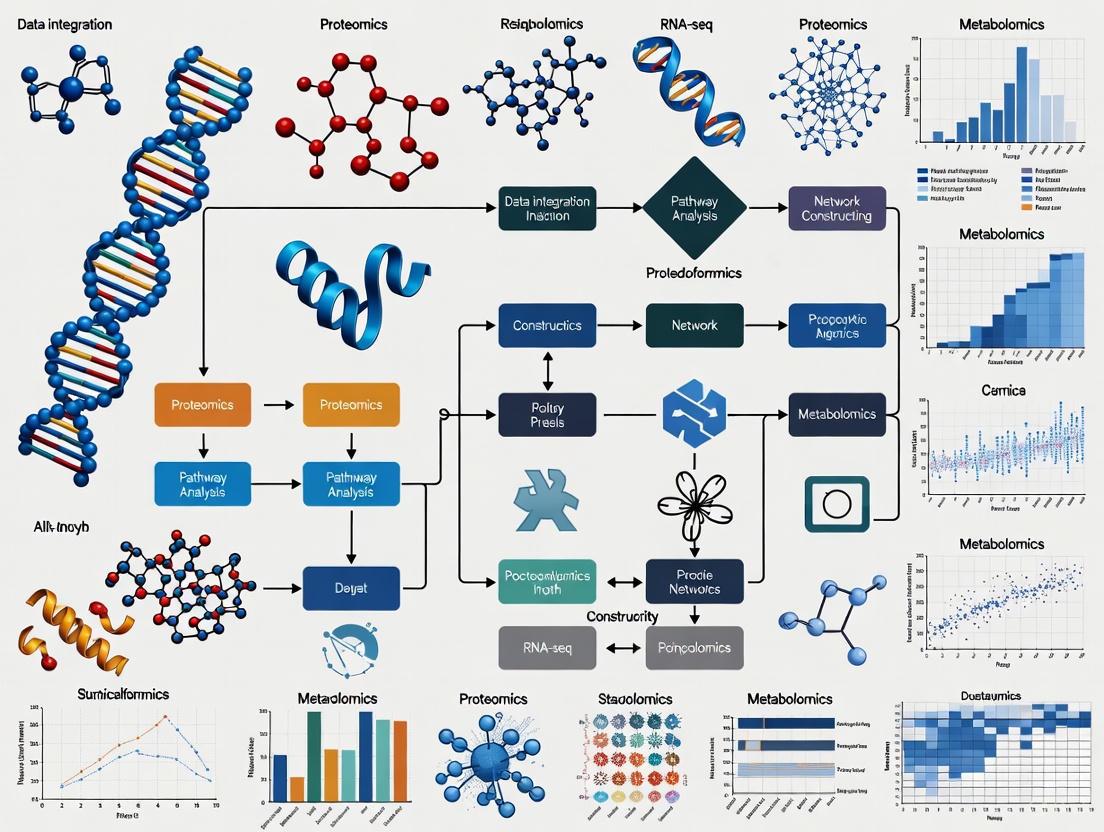

The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow for analyzing causal relationships between chromatin accessibility and gene expression using the HALO framework:

Figure 1: HALO Causal Modeling Workflow

Multi-Omics Integration Strategies

The following diagram illustrates the three primary strategies for multi-omics data integration and their relationships:

Figure 2: Multi-Omics Integration Strategies

Successful multi-omics research requires both wet-lab reagents for data generation and computational tools for data analysis. The following table outlines essential resources for conducting comprehensive multi-omics studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Resource | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Single-cell multi-ome kits | Simultaneous measurement of RNA and chromatin accessibility from same cell (e.g., 10x Multiome) | Vertical integration studies requiring matched transcriptome and epigenome |

| Antibody panels | Protein surface marker detection in CITE-seq experiments | Integration of transcriptome and proteome in single cells | |

| Spatial barcoding reagents | Capture location-specific molecular profiles | Spatial multi-omics integrating molecular data with tissue context | |

| Computational Tools | Seurat v4/v5 | Weighted nearest-neighbor integration for multiple modalities | Vertical integration of mRNA, protein, chromatin accessibility data |

| CellWalker2 | Graph diffusion-based model for hierarchical cell-type annotation | Mapping multi-modal data to cell types, comparing ontologies across species | |

| HALO | Causal modeling of epigenome-transcriptome relationships | Analyzing coupled/decoupled dynamics between chromatin accessibility and gene expression | |

| MOFA+ | Factor analysis for multi-omics integration | Identifying latent factors driving variation across omics layers | |

| GLUE | Graph-linked unified embedding using variational autoencoders | Diagonal integration of unmatched multi-omics datasets | |

| Database Resources | STRING | Protein-protein interaction networks with confidence scores | Network-based integration, identifying functional modules |

| KEGG/Reactome | Pathway databases with multi-omics context | Functional interpretation of integrated omics signatures | |

| CellOntology | Hierarchical cell type ontologies | Reference frameworks for cell type annotation across studies |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

The integration of multi-omics data through hierarchical modeling has demonstrated significant value in drug discovery and biomedical research. Network-based multi-omics integration approaches have been successfully applied to three key areas in pharmaceutical development:

Drug Target Identification: By integrating genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics data within biological networks, researchers can identify critical nodes that drive disease pathways. For example, Huang et al. combined single-cell transcriptomics and metabolomics data to delineate how NNMT-mediated metabolic reprogramming drives lymph node metastasis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, revealing potential therapeutic targets [15].

Drug Response Prediction: Multi-omics integration enables more accurate prediction of drug responses by capturing the complex interactions between drugs and their multiple targets across different molecular layers. Methods that incorporate hierarchical cell-type relationships, such as CellWalker2, improve the mapping of drug effects across different cellular contexts and species [14] [15].

Drug Repurposing: Network-based integration of multi-omics data facilitates drug repurposing by revealing novel connections between existing drugs and disease mechanisms. For instance, Liao et al. integrated multi-omics data spanning genomics, transcriptomics, DNA methylation, and copy number variations across 33 cancer types to elucidate the genetic alteration patterns of SARS-CoV-2 virus target genes, identifying potential repurposing opportunities [15].

The hierarchical understanding of omics layers also enables researchers to distinguish between different types of regulatory relationships that have distinct implications for therapeutic intervention. For example, HALO's differentiation between coupled and decoupled epigenome-transcriptome relationships helps identify contexts where chromatin remodeling directly coordinates with transcriptional changes versus situations where these layers operate independently [13]. This distinction is crucial for developing epigenetic therapies that effectively modulate gene expression programs.

The biological hierarchy of omics layers represents a complex, dynamic system where information flows through multiple regulatory tiers to determine cellular phenotype. Understanding the dynamic relationships between these layers—genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—requires sophisticated integrative approaches that can capture both coupled and decoupled behaviors across temporal and spatial dimensions.

Advances in computational methods, particularly network-based integration frameworks and causal modeling approaches, have dramatically improved our ability to reconstruct these hierarchical relationships from high-throughput data. Tools like HALO, CellWalker2, and GLUE represent a new generation of multi-omics integration methods that move beyond simple correlation to model the directional influences and hierarchical organization inherent in biological systems [14] [13] [15].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on incorporating temporal and spatial dynamics more explicitly, improving model interpretability, and establishing standardized evaluation frameworks. As single-cell and spatial technologies continue to advance, the integration of omics data across resolution scales—from single molecules to whole tissues—will present both new challenges and opportunities. The growing application of these methods in drug discovery underscores their translational potential, enabling more precise targeting of disease mechanisms and personalized therapeutic strategies [15].

Ultimately, the hierarchical framework for understanding omics layers provides not only a more accurate model of biological organization but also a practical roadmap for therapeutic intervention across multiple levels of regulatory control. By continuing to refine our computational approaches and experimental designs, we move closer to a comprehensive understanding of biological systems in health and disease.

The integration of multi-omics data represents a transformative approach within systems biology, converging various 'omics' technologies to concurrently evaluate multiple strata of biological information [17]. This field has witnessed unprecedented growth, with scientific publications more than doubling in just two years (2022–2023) since its first referenced mention in 2002 [17]. The potential benefits of robust multi-omics pipelines are plentiful, providing deep understanding of disease-associated molecular mechanisms, facilitating precision medicine by accounting for individual omics profiles, fostering early disease detection, aiding biomarker discovery, and spotlighting molecular targets for innovative drug development [17]. However, the analysis of these complex datasets presents significant computational and statistical challenges that must be addressed to realize the full potential of integrative bioinformatics methods for multi-omics data mining research.

The core challenges reside in three interconnected domains: the heterogeneity of data types and scales, the massive volume of generated data, and the extreme dimensionality that characterizes each omics layer. These challenges are particularly acute in clinical and translational research settings where samples may be processed across different laboratories worldwide, creating harmonization issues that complicate data integration [4]. Even when datasets can be combined, they are commonly assessed individually with results subsequently correlated, an approach that fails to maximize information content [4]. This technical review examines these fundamental challenges and presents established methodologies to address them, providing researchers with practical frameworks for multi-omics data mining.

Understanding the Core Computational Challenges

Data Heterogeneity: The Integration Imperative

Data heterogeneity in multi-omics research stems from measuring fundamentally different biological entities across multiple molecular layers. The integration of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and other omics fields creates a significant challenge because each modality has unique data scales, noise ratios, and requires specific preprocessing steps [8]. Convention suggests that actively transcribed genes should have greater open chromatin accessibility, but this correlation may not always hold true. Similarly, for RNA-seq and protein data, the most abundant protein may not correlate with high gene expression, creating a disconnect that makes integration difficult [8].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Omics Data Types Contributing to Heterogeneity

| Omics Layer | Measured Entities | Data Characteristics | Technical Variations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequences and variations | Static, high stability | Sequencing platforms, coverage depth |

| Epigenomics | DNA methylation, histone modifications | Dynamic, tissue-specific | Bisulfite treatment, antibody specificity |

| Transcriptomics | RNA expression levels | Highly dynamic, cell-specific | RNA capture methods, library preparation |

| Proteomics | Protein abundance and modifications | Moderate stability, post-translational regulation | Mass spectrometry platforms, sample prep |

| Metabolomics | Small molecule metabolites | Highly dynamic, real-time activity | Extraction methods, chromatography |

Furthermore, these omics are not captured with the same breadth, meaning there is inevitably missing data [8]. For instance, scRNA-seq can profile thousands of genes, while current proteomic methods have a more limited spectrum, perhaps detecting only 100 proteins [8]. This disparity in feature coverage makes cross-modality cell-cell similarity more difficult to measure and requires specialized computational tools.

Data Volume: The Storage and Processing Crisis

The volume of multi-omics data continues to grow exponentially, creating significant bottlenecks in storage, management, and computational processing. The fundamental issue lies in the massive scale of data in terms of volume, intensity, and complexity that often exceeds the capacity of standard analytic tools [18]. This challenge is particularly evident in studies such as the one by Chen et al. (2012), where over three billion measurements were collected across 20 time points for just one participant [17].

The data volume challenge manifests in two primary computational barriers: (1) datasets too large to hold in a computer's memory, and (2) computing tasks that take prohibitively long to complete [18]. These barriers necessitate specialized statistical methodologies and computational approaches tailored for massive datasets. As multi-omics technologies advance, particularly with the rise of single-cell and spatial omics approaches, these volume-related challenges are expected to intensify, requiring more sophisticated data infrastructure and management solutions [4].

Data Dimensionality: The Curse and Its Consequences

The "curse of dimensionality" refers to various phenomena that arise when analyzing and organizing data in high-dimensional spaces that do not occur in low-dimensional settings [19]. In multi-omics research, this challenge is particularly acute because each omics layer can contribute thousands to millions of features, creating a combinatorial explosion that complicates analysis and interpretation.

Table 2: Manifestations of the Curse of Dimensionality in Multi-Omics Research

| Phenomenon | Description | Impact on Multi-Omics Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial Explosion | Each variable can take several discrete values, creating a huge number of possible combinations that must be considered [19]. | Analysis of genetic interactions becomes computationally intractable |

| Data Sparsity | As dimensionality increases, the volume of space increases so fast that available data become sparse [19]. | Inadequate sampling of the possible feature space |

| Distance Function Degradation | Little difference in distances between different pairs of points in high-dimensional space [19]. | Clustering and similarity measures become less meaningful |

| Peaking Phenomenon | Predictive power first increases then decreases as features are added beyond an optimal point [19]. | Model performance deteriorates with too many features |

In high-dimensional datasets, all objects appear to be sparse and dissimilar in many ways, which prevents common data organization strategies from being efficient [19]. For example, in a dataset with 200 individuals and 2000 genes (features), the number of possible gene pairs exceeds 3.9 million, triple combinations exceed 7.9 billion, and higher-order combinations quickly become computationally intractable [19]. This dimensionality effect critically affects both computational time and space when searching for associations or optimal features to consider in multi-omics studies.

Methodological Approaches for Addressing Multi-Omics Challenges

Statistical and Computational Frameworks for Big Data

Several statistical methodologies have been developed specifically to address the computational challenges posed by massive datasets, which can be loosely grouped into three categories: subsampling-based, divide and conquer, and online updating for stream data [18].

Subsampling-based approaches include methods like the bag of little bootstraps (BLB), which provides both point estimates and quality measures such as variance or confidence intervals [18]. BLB combines subsampling, the m-out-of-n bootstrap, and the bootstrap to achieve computational efficiency by drawing s subsamples of size m from the original data of size n, then for each subset, drawing r bootstrap samples of size n. Leveraging methods represent another subsampling approach that uses nonuniform sampling probabilities so that influential data points are sampled with higher probabilities [18].

Divide and conquer approaches involve partitioning the data into subsets, analyzing each subset separately, and then combining the results [18]. This methodology facilitates distributed computing by allowing each partition to be processed by separate processors, significantly reducing computation time for very large datasets.

Online updating approaches are designed for stream data where observations arrive sequentially [18]. These methods update parameter estimates as new data arrives without recomputing from scratch, making them suitable for real-time analysis of continuously generated multi-omics data.

Multi-Omics Integration Strategies

The integration of multi-omics data can be conceptualized as operating at three distinct levels: horizontal, vertical, and diagonal integration [8].

Vertical integration merges data from different omics within the same set of samples, essentially equivalent to matched integration [8]. The cell itself serves as the anchor to bring these omics together. Methods for vertical integration include matrix factorization (e.g., MOFA+), neural network-based approaches (e.g., scMVAE, DCCA, DeepMAPS), and network-based methods (e.g., cite-Fuse, Seurat v4) [8].

Diagonal integration represents the most technically challenging form, where different omics from different cells or different studies are brought together [8]. Since the cell cannot serve as an anchor, these methods typically project cells into a co-embedded space or non-linear manifold to find commonality between cells in the omics space. Tools like Graph-Linked Unified Embedding (GLUE) use graph variational autoencoders to learn how to anchor features using prior biological knowledge [8].

Mosaic integration serves as an alternative to diagonal integration, used when experimental designs have various combinations of omics that create sufficient overlap [8]. For example, if one sample has transcriptomics and proteomics, another has transcriptomics and epigenomics, and a third has proteomics and epigenomics, there is enough commonality to integrate the data. Tools such as COBOLT and MultiVI enable this approach for integrating mRNA and chromatin accessibility data [8].

Visualization Approaches for Multi-Omics Data

Effective visualization tools are essential for interpreting complex multi-omics datasets. The Cellular Overview tool enables simultaneous visualization of up to four types of omics data on organism-scale metabolic network diagrams [20]. This tool paints individual omics datasets onto different "visual channels" of the metabolic-network diagram—for example, displaying transcriptomics data as the color of metabolic-reaction edges, proteomics data as reaction edge thickness, and metabolomics data as metabolite node colors [20].

Table 3: Multi-Omics Visualization Tools and Capabilities

| Tool | Visualization Type | Multi-Omics Capacity | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTools Cellular Overview | Metabolic network diagrams | Up to 4 data types simultaneously | Semantic zooming, animation, organism-specific diagrams |

| KEGG Mapper | Pathway diagrams | Multiple data types | Manual pathway drawings, widely adopted |

| Escher | User-defined pathways | Customizable | Manually drawn diagrams, flexible design |

| ReconMap | Full metabolic network | Up to 4 data types | Manually drawn human metabolic network |

| VisANT | General network layouts | Multiple data types | General layout algorithms |

Advanced visualization tools support semantic zooming that alters the amount of information displayed as users zoom in and out, and can animate datasets containing multiple time points [20]. These capabilities are particularly valuable for exploring dynamic biological processes captured through longitudinal multi-omics studies.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis

A robust protocol for multi-omics integration involves systematic steps from experimental design through data integration and interpretation. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive approach:

Step 1: Experimental Design - Carefully plan the study to ensure appropriate sample sizes, controls, and matched measurements across omics layers. Consider whether the research question requires longitudinal sampling, and determine the optimal frequency for different omics measurements based on their dynamic ranges [17].

Step 2: Sample Preparation - Implement standardized protocols for sample collection, storage, and processing. For single-cell multi-omics, optimize dissociation protocols to maintain cell viability while preserving molecular integrity [4].

Step 3: Data Generation - Utilize appropriate technologies for each omics layer, considering platform-specific advantages and limitations. For genomics, select between short-read and long-read sequencing based on the need for detecting structural variations or resolving complex regions [4].

Step 4: Preprocessing - Apply modality-specific preprocessing pipelines. For sequencing data, this includes adapter trimming, quality filtering, and read alignment. For proteomics data, perform peak detection, deisotoping, and charge state deconvolution [8].

Step 5: Quality Control - Implement rigorous quality control measures for each datatype, removing low-quality samples or features. Use principal component analysis to identify batch effects and outliers [21].

Step 6: Normalization - Apply appropriate normalization methods to address technical variation within each datatype. For RNA-seq data, this might include TPM normalization or DESeq2's median of ratios; for proteomics data, use variance-stabilizing normalization [21].

Step 7: Dimensionality Reduction - Employ techniques like PCA, UMAP, or autoencoders to reduce dimensionality while preserving biological signal. Select the number of components that capture sufficient biological variation without overfitting [19].

Step 8: Data Integration - Choose an integration strategy (vertical, diagonal, or mosaic) based on the experimental design and implement appropriate integration tools from Table 4 [8].

Step 9: Interpretation - Analyze the integrated data to extract biological insights, validate findings using independent methods, and generate testable hypotheses for further experimentation [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 4: Key Resources for Multi-Omics Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | GEO [21], PRIDE [21], MetaboLights [21] | Storage and retrieval of publicly available omics datasets |

| Integration Tools | Seurat v4 [8], MOFA+ [8], GLUE [8] | Computational integration of multiple omics datatypes |

| Visualization Software | PTools Cellular Overview [20], Escher [20] | Visual exploration and interpretation of multi-omics data |

| Statistical Platforms | R/Bioconductor, Python Scikit-learn | Implementation of statistical methods for big data analysis |

| Workflow Management | Nextflow, Snakemake | Orchestration of complex multi-omics analysis pipelines |

The challenges of data heterogeneity, volume, and dimensionality in multi-omics research are substantial but not insurmountable. As the field continues to evolve, several emerging trends are likely to shape future approaches to these challenges. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are becoming indispensable for analyzing vast, complex datasets, facilitating deeper insights into disease pathways and biomarkers [22]. Advances in data storage, computing infrastructure, and federated computing will further support the integration of diverse omics data [4]. The development of purpose-built analysis tools that can ingest, interrogate, and integrate a variety of omics data types will provide answers that have eluded biomedical research in mono-modal paradigms [4].

Furthermore, the application of multi-omics in clinical settings represents a significant trend, integrating molecular data with clinical measurements to improve patient stratification, predict disease progression, and optimize treatment plans [4]. Liquid biopsies exemplify this clinical impact, analyzing biomarkers like cell-free DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites non-invasively across various medical domains [4]. As these technologies mature, collaboration among researchers, industry, and regulatory bodies will be essential to drive innovation, establish standards, and create frameworks that support the clinical application of multi-omics [22]. By systematically addressing the challenges of heterogeneity, volume, and dimensionality, researchers can unlock the full potential of multi-omics data to advance personalized medicine and transform our understanding of human health and disease.

Integrative bioinformatics represents the cornerstone of modern multi-omics research, providing the computational framework necessary to synthesize information across genomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and other molecular layers. This approach has become indispensable for uncovering complex biological mechanisms and advancing precision medicine. Data integration in biological research is formally defined as the computational solution enabling users to fetch data from different sources, combine, manipulate, and re-analyze them to create new shareable datasets [23]. The paradigm has shifted from isolated analyses to unified approaches where multi-omics integration allows researchers to build comprehensive molecular portraits of biological systems.

The technical foundation for this integration relies on two primary computational frameworks: "eager" and "lazy" integration. Eager integration (warehousing) involves copying data to a global schema stored in a central data warehouse, while lazy integration maintains data in distributed sources, integrating on-demand using global schema mapping [23]. Each approach presents distinct advantages for different research scenarios, with warehousing providing performance benefits for frequently accessed data and federated approaches offering flexibility for rapidly evolving datasets. As biological datasets continue expanding at an unprecedented pace, with next-generation sequencing technologies generating terabytes of data, these computational strategies have become increasingly critical for managing the volume and complexity of multi-omics information [23].

Comprehensive Genomic and Multi-Omics Centers

Large-scale bioinformatics centers provide foundational data infrastructure supporting global multi-omics research. The National Genomics Data Center (NGDC), part of the China National Center for Bioinformation (CNCB), offers one of the most comprehensive suites of database resources supporting the global scientific community [24]. This center addresses the challenges posed by the ongoing accumulation of multi-omics data through continuous evolution of its core database resources via big data archiving, integrative analysis, and value-added curation. Recent expansions include collaborations with international databases and establishment of new subcenters focusing on biodiversity, traditional Chinese medicine, and tumor genetics [24].

The NGDC has developed innovative resources spanning multiple omics domains, including single-cell omics (scTWAS Atlas), genome and variation (VDGE), health and disease (CVD Atlas, CPMKG, Immunosenescence Inventory, HemAtlas, Cyclicpepedia, IDeAS), and biodiversity and biosynthesis (RefMetaPlant, MASH-Ocean) [24]. These resources collectively provide researchers with specialized tools for investigating specific biological questions while maintaining interoperability within the larger multi-omics landscape. The center also provides research tools like CCLHunter, facilitating practical analysis workflows [24]. All NGDC resources and services are publicly accessible through its main portal (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn), providing open access to the global research community.

Table 1: Major Integrated Multi-Omics Database Centers

| Center Name | Primary Focus | Key Resources | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) | Comprehensive multi-omics data | scTWAS Atlas, VDGE, CVD Atlas, RefMetaPlant | https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn |

| Database Commons | Curated catalog of biological databases | Worldwide biological database catalog | https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databasecommons/ |

| European Cancer Moonshot Lund Center | Cancer biobanking and multi-omics | Integrated proteomic, genomic, and metabolomic pipelines | Institutional collaboration |

Specialized Proteomics Databases

Proteomics databases provide essential resources for understanding protein expression, interactions, and modifications, offering critical functional context to genomic findings. UniProt (Universal Protein Resource) represents one of the most comprehensive protein sequence and annotation databases available, integrating data from multiple sources to provide high-quality information on protein function, structure, and biological roles [25]. Its components include UniProtKB (knowledgebase), UniRef (reference clusters), and UniParc (archive), each serving distinct roles in protein annotation. The platform also offers practical analysis tools, including BLAST for sequence alignment, peptide search, and ID mapping capabilities [25].

For mass spectrometry-based proteomics data, PRIDE (Proteomics Identifications Database) serves as a cornerstone repository, functioning as part of the ProteomeXchange consortium. PRIDE provides not only protein and peptide identification data from scientific publications but also the underlying evidence supporting these identifications, including raw MS files and processed results [25]. The Peptide Atlas extends this capability by aggregating mass spectrometry data reprocessed through a unified analysis pipeline, ensuring high-quality results with well-understood false discovery rates [25]. For human-specific protein research, the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) offers an exceptional knowledge base integrating tissue expression, subcellular localization, cell line expression, and pathology information across its twelve specialized sections [25].

Table 2: Essential Proteomics Databases for Multi-Omics Integration

| Database | Primary Focus | Key Features | Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|