Informacophores: The Data-Driven Blueprint for Next-Generation Drug Discovery

This article explores the emerging concept of the informacophore, a transformative paradigm in data-driven medicinal chemistry that extends beyond traditional pharmacophores by integrating minimal chemical structures with computed molecular descriptors,...

Informacophores: The Data-Driven Blueprint for Next-Generation Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the emerging concept of the informacophore, a transformative paradigm in data-driven medicinal chemistry that extends beyond traditional pharmacophores by integrating minimal chemical structures with computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive examination of the informacophore's foundation, its methodological application in accelerating lead optimization and virtual screening, strategies to overcome challenges like model interpretability and data quality, and a comparative analysis with established approaches. The article synthesizes how informacophores, by leveraging ultra-large chemical libraries and AI, are poised to reduce intuitive bias, accelerate discovery timelines, and systematically identify novel bioactive compounds.

From Pharmacophore to Informacophore: Defining the Data-Driven Essence of Bioactivity

The Limitation of Classical Intuition in Drug Discovery

Medicinal chemistry is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from a reliance on classical intuition and heuristic approaches toward a rigorous, data-driven scientific discipline. Traditionally, hit-to-lead and lead optimization (LO) projects have progressed largely based on the intuition, experience, and individual contributions of practicing medicinal chemists [1]. This resource-intense and time-consuming process has often been perceived as more of an art form than rigorous science, with decisions about which compounds to synthesize next frequently made without comprehensive support from available data [1]. The emerging paradigm of data-driven medicinal chemistry (DDMC) addresses these limitations by leveraging computational informatics methods for data integration, representation, analysis, and knowledge extraction to enable evidence-based decision-making [1]. Central to this transformation is the concept of the informacophore – an extension of the traditional pharmacophore that incorporates computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations of chemical structure essential for biological activity [2].

The informacophore represents the minimal chemical structure, enhanced by data-driven insights, that is necessary for a molecule to exhibit biological activity [2]. Unlike traditional pharmacophores, which rely on human-defined heuristics and chemical intuition, informacophores are derived from the analysis of ultra-large datasets of potential lead compounds, enabling a more systematic and bias-resistant strategy for scaffold modification and optimization [2]. This approach significantly reduces the biased intuitive decisions that often lead to systemic errors while simultaneously accelerating drug discovery processes [2].

The Limitations of Classical Intuition in Drug Development

Cognitive Constraints and Heuristic Dependency

Human cognitive limitations present significant barriers to optimal decision-making in traditional medicinal chemistry. Humans have a limited capacity to process information, which forces reliance on heuristics – mental shortcuts that can introduce systematic errors and biases [2]. In practice, bioisosteric replacement often depends on limited and sometimes unstructured data, requiring highly experienced chemists to simplify decision-making paths based on visual chemical-structural motif recognition and association with retrosynthetic routes and pharmacological properties [2]. This intuition stems from the chemist's experience in pattern recognition but becomes increasingly inadequate when navigating the vast chemical spaces of modern drug discovery.

Resource Inefficiency and Confirmation Bias

Classical drug discovery follows a structured pipeline of complex and time-consuming steps, with estimates suggesting an average cost of $2.6 billion and a complete traditional workflow exceeding 12 years from inception to market [2]. This resource intensity is compounded by several limitations inherent in intuition-driven approaches:

Historical Data Neglect: Learning from data accumulating in-house over time remains an exception rather than the rule in the pharmaceutical industry, resulting in largely unexplored sources of drug discovery knowledge [1]. Exploring historical data requires dedicated resources that are often not allocated in environments where progress is rewarded over retrospective analysis [1].

Confirmation Bias: Decisions around which compounds to synthesize may or may not be supported by quantitative structure-activity relationship analysis or other computational design approaches [1]. It is rare that compound activity data available for the same or closely related targets are taken into consideration, even if such data were previously generated in-house [1].

Data Secrecy Culture: Maintaining an aura of data secrecy works against a culture of proactive and comparative data analysis and prevents the consideration of external data that are not IP relevant and are therefore thought to be 'less valuable' [1].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Classical vs. Data-Driven Medicinal Chemistry

| Aspect | Classical Medicinal Chemistry | Data-Driven Medicinal Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Decision Basis | Intuition, experience, individual heuristic approaches | Computational analysis of integrated internal and external data |

| Data Utilization | Limited historical data consideration, often project-siloed | Comprehensive data integration from multiple sources |

| Chemical Space Navigation | Limited by individual knowledge and cognitive capacity | Enabled by machine learning algorithms processing ultra-large libraries |

| Lead Optimization | Sequential analog generation based on molecular intuition | Predictive modeling and SAR analysis across diverse compound classes |

| Resource Efficiency | High resource intensity, extended timelines | Demonstrated 95% reduction in SAR analysis time [3] |

| Error Propagation | Subject to cognitive biases and systematic errors | Reduced biased intuitive decisions through objective data analysis |

Informacophores: The Data-Driven Evolution of Pharmacophores

From Pharmacophore to Informacophore

The concept of the pharmacophore has long been foundational to medicinal chemistry, defined by IUPAC as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [4]. Traditional pharmacophore models explain how structurally diverse ligands can bind to a common receptor site and are used to identify through de novo design or virtual screening novel ligands that will bind to the same receptor [4]. Typical pharmacophore features include hydrophobic centroids, aromatic rings, hydrogen bond acceptors or donors, cations, and anions [4].

The informacophore extends this established concept by integrating data-driven insights derived not only from structure-activity relationships (SARs) but also from computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations of chemical structure [2]. This evolution represents a fundamental shift from human-defined heuristics to evidence-based molecular feature optimization grounded in comprehensive data analysis.

Technical Foundation of Informacophores

The development of informacophore models leverages advanced computational infrastructure and machine learning approaches:

Data Integration: Informacophores require integration of internal and external data sources, including major public repositories for compounds and activity data from the medicinal chemistry literature and screening campaigns [1]. This integration presents technical challenges in data quality, heterogeneity, and representation that must be overcome through curation protocols and consistent data representation including visualization [1].

Feature Representation: While traditional pharmacophores focus on steric and electronic features, informacophores incorporate multiple layers of molecular representation including computed molecular descriptors, structural fingerprints, and learned representations from neural networks and other machine learning architectures [2].

Model Interpretability: Feeding essential molecular features into complex ML models offers greater predictive power but raises challenges of model interpretability [2]. Unlike traditional pharmacophore models, which rely on human expertise, machine-learned informacophores can be challenging to interpret directly, with learned features often becoming opaque or harder to link back to specific chemical properties [2].

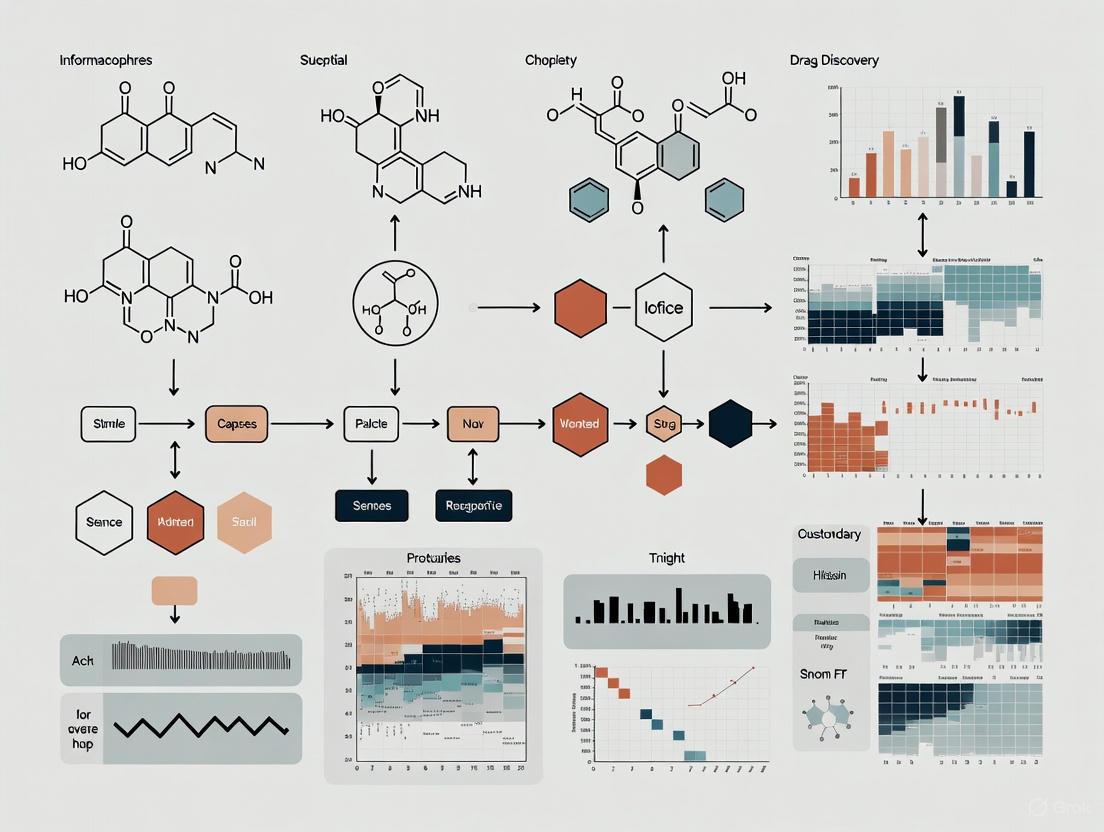

Diagram 1: Evolution from Classical Pharmacophore to Informacophore

Quantitative Assessment of Data-Driven Approaches

Case Study: Implementation at Daiichi Sankyo

A pioneering pilot study at Daiichi Sankyo Company implemented a data-driven medicinal chemistry model through the establishment of a Data-Driven Drug Discovery (D4) group, providing compelling quantitative evidence of the advantages over classical intuition-based approaches [3]. During the monitored 18-month project period involving 32 medicinal chemistry projects, the implementation demonstrated significant improvements in key performance metrics:

SAR Visualization Impact: Structure-activity relationship visualization approaches provided by the D4 group were used in all 32 evaluated projects, leading to highly significant reductions in the required time (95%) compared with the situation before D4 tools became available when SAR analysis was primarily carried out based on R-group tables [3].

Predictive Modeling Contribution: Data analytics and predictive modeling were applied in 18 projects (56% of cases), with 70% of these applications directly contributing to intellectual property (IP) generation, demonstrating the value of data-driven approaches in creating protectable innovations [3].

Tool Utilization Analysis: A total of 60 medicinal chemistry requests were generated and analyzed, containing more than 120 responses to D4 contributions, indicating extensive utilization of data science results and tools by medicinal chemistry project teams [3].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact Assessment of Data-Driven Medicinal Chemistry Implementation

| Metric Category | Implementation Results | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Project Coverage | SAR visualization used in all 32 monitored projects | Comprehensive adoption across portfolio |

| Time Efficiency | 95% reduction in SAR analysis time | Near-elimination of manual R-group table analysis |

| IP Generation | 70% of predictive modeling applications contributed to IP | Direct business value demonstration |

| Method Utilization | 56% of projects applied data analytics and predictive modeling | Balanced approach between visualization and prediction |

| Resource Engagement | 120+ responses to D4 contributions across 60 requests | High engagement and utilization by medicinal chemists |

Ultra-Large Library Screening Capabilities

The development of ultra-large, "make-on-demand" or "tangible" virtual libraries has dramatically expanded the scope of accessible drug candidate molecules beyond human cognitive capacity for pattern recognition [2]. These libraries consist of compounds that have not actually been synthesized but can be readily produced, with suppliers like Enamine and OTAVA offering 65 and 55 billion novel make-on-demand molecules, respectively [2]. To screen such vast chemical spaces, ultra-large-scale virtual screening for hit identification becomes essential, as direct empirical screening of billions of molecules is not feasible [2]. This scale of analysis fundamentally exceeds human intuitive capabilities and requires computational approaches.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Informacophore Model Development

The development of informacophore models follows a rigorous computational and experimental workflow that extends traditional pharmacophore development processes:

Diagram 2: Informacophore Model Development Workflow

Step 1: Training Set Selection Select a structurally diverse set of molecules including both active and inactive compounds for model development [4]. The training set should include compounds with known biological activities, preferably with quantitative IC50 or EC50 values to enable correlation with biological effects [5].

Step 2: Conformational Analysis Generate a set of low-energy conformations likely to contain the bioactive conformation for each selected molecule using methods such as:

- Molecular dynamics simulations

- Random sampling of rotatable bonds

- Precomputed conformational space using algorithms like Catalyst's "polling" algorithm that generates approximately 250 conformers [5]

Step 3: Molecular Superimposition Superimpose all combinations of the low-energy conformations of the molecules using either:

- Point-based techniques: Superimposing pairs of points (atoms or chemical features) by minimizing Euclidean distances using root-mean-square distance to maximize overlap [5]

- Property-based techniques: Using molecular field descriptors to create alignments with tools like GRID, calculating interaction energy for specific probes at each point [5]

Step 4: Feature Abstraction Transform the superimposed molecules into an abstract representation using pharmacophore features including:

- Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA)

- Hydrogen bond donors (HBD)

- Hydrophobic interactions (HYP)

- Ring aromatic (RA)

- Positive ionizable areas (P)

- Negative ionizable areas (N) [5]

Step 5: Machine Learning Integration Extend traditional pharmacophore features with data-driven elements:

- Compute molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, electronic, thermodynamic)

- Generate structural fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, FCFP)

- Apply machine learning algorithms to learn representations from ultra-large chemical libraries

- Integrate features using hybrid methods that combine interpretable chemical descriptors with learned features from ML models [2]

Step 6: Biological Validation Validate the informacophore model through experimental assays:

- Enzyme inhibition assays to measure potency (IC50)

- Cell viability assays to assess cytotoxicity

- Reporter gene expression assays for functional activity

- Pathway-specific readouts to confirm mechanism of action [2]

Step 7: Model Refinement Iteratively refine the model based on biological validation results:

- Incorporate new active compounds as they are discovered

- Adjust feature definitions based on false positive/negative analysis

- Update machine learning models with new screening data

- Optimize for specific drug properties (solubility, selectivity, etc.) [2]

Experimental Validation Framework

While computational tools and AI have revolutionized early-stage drug discovery, theoretical predictions must be rigorously confirmed through biological functional assays to establish real-world pharmacological relevance [2]. The experimental validation framework includes:

Primary Assays: High-throughput screening against intended target using enzyme inhibition, binding assays, or cellular phenotypic assays to confirm predicted activity [2].

Counter-Screening: Testing against related targets and antitargets to assess selectivity and identify potential off-target effects not predicted by computational models [2].

ADMET Profiling: Evaluation of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties using in vitro systems (e.g., microsomal stability, plasma protein binding, Caco-2 permeability) and in vivo models [2].

Lead Optimization Cycle: Iterative design-make-test-analyze cycles where informacophore models guide structural modifications, followed by synthesis and biological testing to validate predictions and refine models [2].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Informacophore Development and Validation

| Reagent/Category | Function in Informacophore Research | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Libraries | Provide diverse structures for model training and validation | Enamine (65B compounds), OTAVA (55B compounds) [2] |

| Cheminformatics Software | Molecular modeling, descriptor calculation, machine learning | MOE, LigandScout, Phase, Catalyst/Discovery Studio [6] [5] |

| Assay Technologies | Experimental validation of predicted activities | High-content screening, phenotypic assays, organoid/3D culture systems [2] |

| Bioinformatics Databases | Source of target and compound activity data | ChEMBL, PubChem Bioassay, Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1] [6] |

| Computational Infrastructure | Enable processing of ultra-large chemical libraries | High-performance computing clusters, Cloud computing resources |

Implementation Framework for Data-Driven Medicinal Chemistry

Organizational Integration Models

Successful implementation of data-driven approaches requires thoughtful organizational design beyond technical considerations. The Daiichi Sankyo D4 group model provides a proven framework for integration [3]:

Cross-Functional Team Composition: The D4 group comprised four data scientists and five researchers with backgrounds in medicinal chemistry, creating a balanced team with complementary expertise [3].

Infrastructure Development: The first year was primarily dedicated to building the team's computational infrastructure as well as initial tool development, implementation, and distribution, recognizing that technical foundations must precede full project engagement [3].

Dual Track Engagement Model: The group served both as a primary interaction partner for medicinal chemistry and as a center for developing and distributing analytical tools and methods [3].

Educational Transformation for Next-Generation Medicinal Chemists

Addressing the human capital requirements of data-driven medicinal chemistry necessitates evolution in educational approaches:

Informatics-Enhanced Chemistry Curricula: Traditionally conservative chemistry curricula must increasingly incorporate informatics education to prepare future generations of chemists for the challenges and opportunities of DDMC [1].

D4 Medicinal Chemist Training Model: At Daiichi Sankyo, individual medicinal chemists from project teams were temporarily assigned to the D4 group and trained to acquire advanced computational skills while applying data science approaches to support their projects [3]. Following a training period of 2 years, these 'D4 medicinal chemists' returned to their original project teams, creating a growing network of practitioners with dual expertise [3].

The limitations of classical intuition in drug discovery are no longer theoretical concerns but demonstrated constraints quantified through comparative implementation studies. The informacophore concept represents a fundamental advancement over traditional pharmacophore approaches by integrating data-driven insights with structural chemistry principles. As medicinal chemistry continues its transition from art to science, the systematic implementation of data-driven strategies will be critical for addressing the key questions that have persisted for years in drug discovery – such as when sufficient compounds have been made in a lead optimization project and no further progress can be expected, or if an initially observed structure-activity relationship can be further evolved [1].

The future of medicinal chemistry lies in hybrid approaches that leverage the pattern recognition capabilities of machine learning systems while maintaining the chemical intuition and creative problem-solving skills of experienced medicinal chemists. By embracing data-driven methodologies centered on concepts like the informacophore, the field can overcome the cognitive limitations and heuristic dependencies that have constrained innovation, ultimately leading to more efficient drug discovery pipelines with improved clinical success rates and reduced development timelines.

What is an Informacophore? A Multi-Faceted Definition

In the evolving landscape of data-driven medicinal chemistry, the informacophore represents a paradigm shift from traditional, intuition-based drug discovery to a computational, data-centric approach. It is defined as the minimal chemical structure, augmented by computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations, that is essential for a molecule to exhibit biological activity [2]. Similar to a skeleton key that unlocks multiple locks, the informacophore identifies the core molecular features that trigger a biological response [2]. This concept is pivotal in leveraging ultra-large chemical datasets and machine learning (ML) to reduce biased decision-making and accelerate the drug discovery process [2].

From Pharmacophore to Informacophore: An Evolutionary Leap

The informacophore is the modern evolution of the classic pharmacophore. While both concepts aim to define the structural essentials for bioactivity, they differ fundamentally in their origin and application.

- The Classical Pharmacophore: Traditionally, a pharmacophore represents the spatial arrangement of chemical features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, hydrophobic regions) essential for molecular recognition by a biological target. This model is rooted in human-defined heuristics and the chemical intuition of experienced medicinal chemists [2].

- The Modern Informacophore: The informacophore extends this idea by incorporating data-driven insights. It is derived not only from structure-activity relationships (SARs) but also from computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations of chemical structure [2]. This fusion of structural chemistry with informatics enables a more systematic and bias-resistant strategy for scaffold modification and optimization.

The following workflow illustrates how informacophores are developed and applied within a data-driven discovery pipeline:

The Computational Framework of Informacophores

The identification and application of informacophores rely on a robust computational infrastructure. The core of this framework involves specific data types and machine learning algorithms that work in concert to distill actionable insights from vast chemical datasets.

- Table 1: Core Computational Components of an Informacophore

| Component | Description | Role in Informacophore Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | Quantitative measures of a molecule's physicochemical properties (e.g., logP, molecular weight, polar surface area) [7]. | Provides a numerical representation of the chemical structure that influences biological activity [2]. |

| Molecular Fingerprints | Bit-string representations that encode the presence or absence of specific substructures or paths in a molecule [7]. | Enables rapid similarity searching and pattern recognition across ultra-large chemical libraries [2]. |

| Machine-Learned Representations | Abstract, high-dimensional vectors (embeddings) learned by neural networks (e.g., Graph Neural Networks, Autoencoders) [7]. | Captures complex, non-intuitive structure-activity relationships beyond human-defined features [2]. |

Machine learning models, particularly Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), are exceptionally well-suited for this task as they natively operate on molecular graph structures (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) [7]. Other techniques like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are used to explore the chemical space around an informacophore and generate novel compounds with the desired bioactivity [7]. A key challenge, however, is the interpretability of these complex models. Unlike traditional pharmacophores, machine-learned informacophores can be opaque, making it difficult to link features back to specific chemical properties. Hybrid methods that combine interpretable descriptors with learned features are emerging to bridge this gap [2].

Experimental Validation: From In-Silico Prediction to Biological Reality

Computational predictions of informacophores must be rigorously validated through experimental assays. This iterative cycle of prediction and validation is central to modern drug discovery, ensuring that data-driven hypotheses translate into real-world therapeutic potential [2].

- Table 2: Key Experimental Assays for Informacophore Validation

| Assay Type | Function | Protocol & Measured Output |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Assays | Confirm direct physical interaction between the compound and its protein target. | Method: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Thermal Shift Assay. Output: Binding affinity (KD, IC₅₀), a quantitative measure of interaction strength [2]. |

| Functional Assays | Determine the compound's effect on the biological function of the target (e.g., inhibition or activation). | Method: Enzyme inhibition, cell viability (MTT), or reporter gene assays. Output: Potency (EC₅₀), efficacy (maximum effect), and mechanism of action [2] [7]. |

| ADMET Profiling | Evaluate the compound's Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties. | Method: In vitro models like Caco-2 for permeability, microsomal stability tests, and hERG assays for cardiotoxicity. Output: Key parameters like metabolic half-life, permeability, and toxicity risk [7]. |

Case studies of discovered drugs highlight this critical synergy. For instance, the antibiotic Halicin was first identified by a deep learning model trained on antibacterial molecules. However, its broad-spectrum efficacy, including against multidrug-resistant pathogens, was conclusively demonstrated through subsequent in vitro and in vivo biological assays [2]. Similarly, the repurposing of Baricitinib for COVID-19, while suggested by an AI algorithm, required extensive in vitro and clinical validation to confirm its antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects [2]. These examples underscore that without biological functional assays, even the most promising computational leads remain hypothetical.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Data-Driven Discovery

The practical implementation of informacophore-based research requires a suite of computational and experimental resources.

- Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Informacophore Research |

|---|---|

| Ultra-Large Virtual Compound Libraries (e.g., Enamine: 65B molecules, OTAVA: 55B molecules) [2]. | Provide the vast chemical space for initial virtual screening and informacophore hypothesis generation. |

| Public Bioactivity Databases (e.g., ChEMBL [1], PubChem [1]) | Serve as critical sources of structured, publicly available SAR data for model training and validation. |

| Informatics & Data Science Platforms (e.g., Python with RDKit, TensorFlow/PyTorch for deep learning) | Enable the computation of molecular descriptors, model training, and chemical space analysis. |

| High-Content Screening Systems | Advanced experimental platforms that provide high-resolution, multiparametric data from phenotypic assays, feeding back into the informacophore refinement loop [2]. |

The informacophore represents a cornerstone of the ongoing digital transformation in medicinal chemistry. By providing a data-driven definition of the minimal features required for bioactivity, it enables the systematic and efficient navigation of ultra-large chemical spaces that are intractable for traditional methods. The future of this field hinges on overcoming the challenge of model interpretability and further strengthening the iterative feedback loop between artificial intelligence and experimental biology. As these methodologies mature, the informacophore is poised to significantly reduce the time and cost associated with bringing new therapeutics to market, solidifying its role as an indispensable concept in the data-driven drug discovery toolkit.

The evolution of data-driven medicinal chemistry has introduced the informacophore as a pivotal concept, representing the minimal chemical structure enhanced by computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations essential for biological activity [2]. This whitepaper provides a technical guide to the three core components that constitute an informacophore: the structural scaffold, which serves as the foundational molecular framework; molecular descriptors and fingerprints, which provide quantitative, human-interpretable representations of chemical properties and substructures; and machine-learned representations, which utilize deep learning to capture complex, non-linear structure-activity relationships [2] [8]. We detail the methodologies for their application, present quantitative comparisons, and visualize their integration in modern drug discovery workflows, offering researchers a comprehensive framework for leveraging informacophores in the design of novel therapeutic agents.

In contemporary medicinal chemistry, the traditional, intuition-based approach to drug design is being supplanted by a data-driven paradigm. Central to this shift is the informacophore, a concept that extends the classical pharmacophore by integrating not only the minimal structural features required for bioactivity but also the computed molecular descriptors and machine-learned representations that provide a more holistic and bias-resistant view of molecular function [2]. This synthesis enables a more systematic and efficient exploration of chemical space, significantly accelerating the hit identification and lead optimization processes [2] [9].

The informacophore model is particularly powerful because it addresses the limitations of human heuristics in processing the vast data generated from ultra-large virtual libraries, which can contain billions of readily synthesizable compounds [2] [9]. By objectively identifying the minimal set of features—both structural and informational—required for activity, the informacophore helps reduce systemic errors and streamlines the path from discovery to commercialization [2]. This guide delves into the three technical pillars that form the informacophore, providing researchers with the methodologies and tools needed for its practical application.

Structural Scaffolds: The Molecular Backbone

The structural scaffold, or core molecular framework, is the fundamental skeleton of a bioactive molecule. It defines the spatial orientation of key functional groups and is paramount for maintaining binding interactions with a biological target.

Scaffold Analysis and Classification

A primary method for organizing chemical datasets is the scaffold tree algorithm, which creates a hierarchical classification based on common core structures. The algorithm proceeds by first associating each compound with its unique scaffold, obtained by pruning all terminal side chains. This scaffold is then iteratively simplified by removing one ring at a time according to a set of deterministic rules designed to preserve the most characteristic core structure, terminating when a single-ring scaffold remains [10]. This hierarchy allows medicinal chemists to visualize the relationship between complex molecules and their simplified cores, identifying potential virtual scaffolds—those not present in the original dataset but generated during pruning—which represent promising starting points for novel compound design [10].

Scaffold hopping is a critical strategy that leverages this hierarchical understanding. It aims to discover new core structures that retain biological activity, often to improve properties like metabolic stability or to circumvent existing patents [8] [11]. The process can be categorized into several types, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Categories of Scaffold Hopping in Drug Design

| Hop Category | Description | Key Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Heterocyclic Substitutions | Replacing one ring system with another that has similar electronic or steric properties. | Bioisosteric replacement [8]. |

| Ring Opening/Closing | Transforming a cyclic scaffold into an acyclic one, or vice versa, while maintaining key pharmacophore distances. | 3D pharmacophore alignment [8] [11]. |

| Peptide Mimicry | Designing non-peptide scaffolds that mimic the topology and functionality of a peptide. | 3D molecule alignment (e.g., FlexS) [8] [11]. |

| Topology-Based Hops | Altering the core connectivity while preserving the overall spatial arrangement of functional groups. | Pharmacophore-based similarity screening (e.g., FTrees) [8] [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: Hierarchical Scaffold Analysis

Objective: To classify a dataset of bioactive compounds and identify key molecular scaffolds and their relationships. Materials: A dataset of chemical structures in SMILES or SDF format; software such as Scaffold Hunter [12] [10]. Methodology:

- Data Curation: Load the molecular dataset. Apply curation steps including removal of duplicates and salts, and standardization of tautomers and charges.

- Scaffold Extraction: For each molecule, generate its Bemis-Murcko scaffold by removing all terminal acyclic atoms, retaining only the ring systems and the linker atoms that connect them.

- Tree Construction: Apply the scaffold tree algorithm to hierarchically decompose each complex scaffold into simpler ancestors through iterative ring removal, following predefined rules that prioritize the preservation of aromatic over non-aromatic rings and more complex ring systems over simpler ones [10].

- Visualization & Analysis: Use the Scaffold Hunter framework to visualize the resulting scaffold tree. Analyze the distribution of molecules across different scaffolds, identify frequently occurring (privileged) scaffolds, and pinpoint virtual scaffolds that represent opportunities for chemical exploration [10].

Molecular Descriptors and Fingerprints: The Quantitative Lens

Molecular descriptors and fingerprints are mathematical representations that encode the physical, chemical, and structural properties of molecules, enabling quantitative analysis and modeling.

Key Types and Applications

Descriptors are numerical values that quantify specific molecular properties, such as molecular weight, logP (partition coefficient), topological polar surface area (TPSA), and molar refractivity. They are crucial for constructing Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models and for applying drug-likeness filters such as Lipinski's Rule of Five [12] [13].

Fingerprints are bit strings that represent the presence or absence of specific substructures or topological paths within a molecule. Common examples include Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP) and Molecular Access System (MACCS) keys. They are predominantly used for rapid similarity searching, clustering, and as input for machine learning models [12] [8].

Table 2: Key Molecular Descriptors and Fingerprints in Cheminformatics

| Representation Type | Specific Name | Function and Role in Informacophore Development |

|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical Descriptor | Crippen LogP | Predicts lipophilicity; critical for modeling absorption and distribution [13]. |

| Topological Descriptor | Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) | Estimates a molecule's ability to engage in hydrogen bonding; predictive of cell permeability [13]. |

| Constitutional Descriptor | Number of Hydrogen Bond Donors/Acceptors | Key parameter in Lipinski's Rule of Five for assessing drug-likeness [12]. |

| Fingerprint | Extended Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP6) | Encodes circular atom environments; used for similarity search and SAR analysis [12] [8]. |

| Fingerprint | MACCS Keys | A set of 166 structural keys used for substructure screening and rapid molecular similarity assessment [12]. |

Experimental Protocol: Predicting ADME Properties using ML and SHAP Analysis

Objective: To build a machine learning model for predicting human liver microsomal (HLM) stability and identify the most impactful molecular descriptors using SHAP analysis. Materials: A public ADME dataset comprising 3,521 compounds with HLM stability data and 316 pre-calculated RDKit molecular descriptors [13]. Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Divide the dataset into a training set (80%) and a test set (20%). Standardize the descriptor values by removing near-zero variance descriptors and applying scaling.

- Model Training: Train multiple regression models (e.g., Random Forest, LightGBM) on the training set using 5-fold cross-validation. Select the best-performing model based on the mean squared error (MSE) on the test set.

- Feature Importance Analysis: Perform feature permutation on the trained model to estimate the global importance of each molecular descriptor.

- SHAP Analysis: Calculate SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values for the test set predictions. Generate a beeswarm plot to visualize the impact and directionality (positive or negative) of the top descriptors on the model's prediction. For instance, analysis may reveal that higher LogP values negatively impact HLM stability predictions, while higher TPSA values are beneficial [13].

Machine Learning Representations: The Deep Learning Frontier

Machine learning representations, particularly those derived from deep learning, move beyond predefined rules to learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from molecular data.

Modern Representation Approaches

These approaches learn to represent molecules in a latent space where proximity often correlates with functional similarity, even in the absence of structural analogy, thereby facilitating tasks like scaffold hopping [8].

- Language Model-Based: Models like SMILES-BERT treat simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES) strings as a chemical language. They tokenize the string and use Transformer architectures to learn contextual relationships between atoms and substructures, capturing semantic molecular meaning [8].

- Graph-Based: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) natively represent a molecule as a graph with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. Through message-passing operations, GNNs learn to aggregate information from a node's local neighborhood, capturing complex topological patterns that are difficult to express with traditional fingerprints [8] [13].

- Multimodal and Contrastive Learning: These emerging frameworks integrate multiple views of a molecule (e.g., 2D graph, 3D conformation, SMILES string) to learn more robust representations that are invariant to trivial transformations and rich in biochemical context [8].

Experimental Protocol: Scaffold Hopping with a Generative Model

Objective: To use a generative deep learning model to propose novel scaffolds with high predicted activity against a target, starting from a known active compound. Materials: A benchmark dataset of molecules with known activity against the target (e.g., ChEMBL); a generative model architecture such as a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) or a Graph-based model [8] [14]. Methodology:

- Model Pretraining: Pre-train a molecular generative model on a large, diverse chemical library (e.g., ZINC) to learn a general-purpose latent space of chemical structures.

- Activity Fine-Tuning: Fine-tune the model on a smaller, target-specific dataset of active molecules. This shifts the latent space to prioritize regions associated with the desired bioactivity.

- Sampling and Generation: Sample latent vectors from the optimized region of the latent space and decode them into novel molecular structures (e.g., as SMILES strings or graphs).

- Evaluation and Filtering: Filter the generated molecules for drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility, and structural novelty. Validate the proposed scaffolds through in silico docking or by purchasing/comparing with make-on-demand library offerings from suppliers like Enamine [2] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Informacophore Research

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function in Informacophore Development |

|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Hunter [12] [10] | Visualization & Analysis | Interactive visual analytics for scaffold tree, clustering, and property analysis. |

| RDKit [12] [13] | Cheminformatics | Open-source toolkit for calculating molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and substructure searching. |

| KNIME [12] | Workflow Management | Platform for building and executing reproducible data analysis pipelines, integrating various cheminformatics nodes. |

| FTrees / InfiniSee [11] | Virtual Screening | Pharmacophore-based similarity searching for scaffold hopping in ultra-large chemical spaces. |

| FragAI [15] | Generative AI | 3D-aware generative model for designing novel ligands based on protein-ligand structural data. |

| SHAP [13] | Explainable AI | Explains the output of ML models by quantifying the contribution of each input feature. |

Integrated Workflow: From Molecules to Informacophores

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic relationship between the three core components in defining an informacophore for a drug discovery campaign.

The Informacophore Design Workflow. The process begins with input molecules, which are simultaneously analyzed through three parallel streams: structural scaffold identification, calculation of molecular descriptors and fingerprints, and generation of machine-learned representations. These streams converge to form the integrated informacophore model, which guides the iterative design and optimization of a lead candidate.

The informacophore represents a paradigm shift in medicinal chemistry, unifying the concrete molecular reality of structural scaffolds with the quantitative power of molecular descriptors and the predictive sophistication of machine learning representations. This triad forms an indispensable foundation for modern, data-driven drug discovery. As generative AI models and explainable AI techniques continue to mature, the ability to rapidly identify and optimize informacophores will become increasingly central to the efficient development of safer and more effective therapeutics. The methodologies and tools detailed in this guide provide a roadmap for researchers to harness this powerful concept, enabling the navigation of ultra-large chemical spaces with unprecedented precision and insight.

The concept of the informacophore represents a paradigm shift in data-driven medicinal chemistry, moving beyond traditional, intuition-based design to a computational approach that identifies the minimal chemical structure essential for biological activity. This "skeleton key" leverages machine-learned representations, molecular descriptors, and fingerprints to unlock multiple biological targets. By enabling the systematic analysis of ultra-large chemical datasets, the informacophore reduces biased decision-making and accelerates the discovery of novel therapeutic agents [2] [16]. This technical guide details the core principles, quantitative foundations, experimental protocols, and computational methodologies that underpin the informacophore approach in modern drug discovery.

In classical medicinal chemistry, the pharmacophore model has been a cornerstone, representing the spatial arrangement of chemical features essential for a molecule to recognize a biological target. This model, however, is largely rooted in human-defined heuristics and chemical intuition [2] [16].

The informacophore extends this concept into the big data era. It is defined as the minimal chemical structure, combined with its computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned structural representations, that is necessary for a molecule to exhibit biological activity [2] [16]. Like a skeleton key designed to unlock multiple locks, the informacophore aims to identify the fundamental molecular features that can trigger a range of desired biological responses. This approach is particularly powerful in poly-pharmacology, where a single drug is designed to interact with multiple targets, and for identifying privileged scaffolds that can be optimized for specific therapeutic applications [17]. The transition from a traditional pharmacophore to a data-driven informacophore marks a significant evolution in rational drug design (RDD), offering a more systematic and bias-resistant strategy for scaffold modification and optimization [2].

Core Principles and Quantitative Foundations

The informacophore framework integrates several core computational and chemoinformatic principles to create a predictive model for bioactivity.

Chemical Representation and Similarity

At the heart of ligand-based informacophore design is the principle of chemical similarity, which posits that structurally similar molecules are likely to have similar biological properties [17]. To operationalize this, molecular structures are converted into mathematical representations using several methods:

- Path-based fingerprints (e.g., Daylight fingerprints): Use potential paths of different bond lengths in a molecular graph as features [17].

- Substructure-based fingerprints (e.g., MACCS keys): Characterize molecules based on the presence or absence of predefined substructures using a binary array, which can aid in identifying scaffold hopping ligands [17].

- Machine-learned representations: Complex models, such as deep graph networks, can generate novel molecular features that may be opaque to human interpretation but offer high predictive power for activity [2] [18].

The similarity between two molecules is typically quantified using metrics like the Tanimoto index, which computes shared features between two fingerprints, with a value of 0.7-0.8 often indicating significant similarity [17].

Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters for Informacophore Validation

For an informacophore to be therapeutically viable, it must not only be bioactive but also possess favorable drug-like properties. The following table summarizes key experimental pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters derived from FDA-approved drugs, which serve as critical benchmarks during the informacophore optimization process [19].

Table 1: Key Experimental Pharmacokinetic Parameters for Drug Optimization

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Typical Range (Approved Drugs) | Interpretation & Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume of Distribution | VD | Liter | Median: 93 L [19] | Low value (<15L): Drug concentrated in blood. High value (>300L): Extensive tissue distribution [19]. |

| Clearance | Cl | Liter/hour | Median: 17 L/h; 86% of drugs <72 L/h [19] | Indicates elimination efficiency. High clearance shortens half-life [19]. |

| Half-Life | t~1/2~ | Hour | Reported for 1276 drugs [19] | Determines dosing frequency. |

| Plasma Protein Binding | PPB | % | Reported for 1061 drugs [19] | High binding reduces free drug available for activity. |

| Bioavailability | F | % | Reported for 524 drugs [19] | Critical for oral dosing; percentage of drug reaching systemic circulation. |

These PK parameters are optimized in tandem with pharmacodynamic (PD) properties, which summarize the mechanism of action, biological targets, and binding affinities [19]. The integration of PK/PD modeling is essential for transforming a bioactive informacophore into a viable drug candidate.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Identifying and validating an informacophore requires an iterative loop of computational prediction and experimental validation.

Computational Identification Workflow

The in silico process for informacophore discovery involves a multi-stage workflow for analyzing chemical data and predicting bioactive compounds.

Diagram 1: Informacophore Identification Workflow. This flowchart outlines the three-phase computational process for discovering informacophores, from data assembly to virtual screening.

This workflow leverages ultra-large, "make-on-demand" virtual libraries, such as those offered by Enamine (65 billion compounds) and OTAVA (55 billion compounds) [2]. Screening these vast chemical spaces is only feasible through ultra-large-scale virtual screening, as empirical screening of billions of molecules is not practical [2].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The following table details key resources required for the computational and experimental phases of informacophore research.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Informacophore Discovery

| Category / Item | Function in Informacophore Research | Key Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Large Virtual Compound Libraries | Provide billions of synthesizable compounds for virtual screening to identify novel informacophore hits. | Enamine (65B compounds), OTAVA (55B compounds) [2]. "Make-on-demand" or "tangible" libraries [2]. |

| Bioactivity Databases | Provide annotated chemical and biological data for model training and ligand-based target prediction. | ChEMBL, PubChem, DrugBank, BindingDB [17]. |

| Cheminformatics Software & AI Platforms | Perform molecular featurization, similarity searching, QSAR modeling, and de novo molecular generation. | Deep graph networks for analog generation [18]; Platforms for QSAR, ADMET prediction (e.g., SwissADME) [18]. |

| Target Engagement Assays | Experimentally validate that the hypothesized informacophore directly engages the intended biological target in a physiologically relevant context. | CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) for confirming direct binding in intact cells/tissues [18]. |

| Functional Biological Assays | Confirm the predicted biological activity and mechanism of action of the informacophore and its optimized analogs. | Enzyme inhibition, cell viability, high-content screening, organoid/3D culture systems [2] [16]. |

Experimental Validation Protocol

Computational predictions must be rigorously validated through a cascade of experimental assays. This forms a critical feedback loop for refining the informacophore model.

Diagram 2: Experimental Validation Cascade. This flowchart shows the multi-stage experimental process for validating computationally predicted informacophores, highlighting the critical feedback loop.

This validation protocol is exemplified in several successful AI-driven discoveries. For instance, the broad-spectrum antibiotic Halicin was first flagged by a neural network model, but its efficacy against multidrug-resistant pathogens was confirmed through subsequent in vitro and in vivo functional assays [2] [16]. Similarly, the repurposing of Baricitinib for COVID-19, while identified by machine learning, required extensive in vitro and clinical validation to confirm its antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects [2] [16].

Case Studies and Applications

The informacophore approach has demonstrated its utility across various drug discovery campaigns, particularly in accelerating the hit-to-lead process and enabling polypharmacology.

- Accelerated Potency Optimization: A 2025 study showcased the power of AI-driven informacophore optimization. Deep graph networks were used to generate over 26,000 virtual analogs from an initial hit, ultimately yielding sub-nanomolar MAGL inhibitors with a >4,500-fold potency improvement. This demonstrates the dramatic compression of traditional discovery timelines from months to weeks [18].

- Drug Repurposing via Target Prediction: Informatics methods enable the prediction of new molecular targets for existing drugs or active scaffolds. Ligand-based target prediction compares the informacophore of a query compound to a database of target-annotated ligands. Alternatively, structure-based methods like panel docking can identify potential off-targets or new therapeutic applications, a process central to network poly-pharmacology [17]. This approach successfully identified the antiviral potential of the oncology drug Capmatinib [2] [16].

The field of informacophore-based discovery is rapidly evolving, guided by several key trends. There is an increasing emphasis on using high-quality, real-world patient data for AI model training over synthetic data to improve clinical translatability [20]. Furthermore, the integration of functional biomarkers (e.g., event-related potentials in psychiatric drug development) is becoming crucial for providing scientifically valid, interpretable data to support informacophore validation in clinical trials [20].

In conclusion, the informacophore represents a foundational shift in medicinal chemistry. By serving as a data-derived "skeleton key," it provides a systematic, bias-resistant framework for identifying minimal bioactive scaffolds capable of interacting with multiple biological targets. While computational power drives the initial hypothesis, the iterative cycle of prediction and rigorous experimental validation remains paramount. As AI and bioinformatics continue to advance, the informacophore paradigm is poised to further accelerate the delivery of safer, more effective therapeutics.

Contrasting Traditional Pharmacophore and Data-Driven Informacophore Models

The process of drug discovery is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from intuition-led approaches to data-driven methodologies. At the heart of this transition lies the evolution from traditional pharmacophore models to next-generation informacophore frameworks. A pharmacophore represents an abstract description of molecular features essential for molecular recognition of a ligand by a biological macromolecule – "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" according to IUPAC definition [4]. In contrast, the emerging informacophore concept extends this foundation by incorporating computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations of chemical structure that are essential for biological activity [2] [16]. This paradigm shift enables a more systematic and bias-resistant strategy for scaffold modification and optimization in medicinal chemistry.

Table 1: Fundamental Definitions and Characteristics

| Aspect | Traditional Pharmacophore | Data-Driven Informacophore |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Ensemble of steric/electronic features for molecular recognition [4] | Minimal structure combined with computed descriptors & ML representations [2] |

| Basis | Human-defined heuristics and chemical intuition [2] | Data-driven insights from ultra-large datasets [2] |

| Feature Types | Hydrophobic centroids, aromatic rings, H-bond acceptors/donors, cations, anions [4] | Traditional features plus molecular descriptors, fingerprints, learned representations [16] |

| Primary Application | Virtual screening, de novo design, lead optimization [6] | Predictive modeling, bias reduction, accelerated discovery [2] |

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Contrasts

Traditional Pharmacophore Modeling

The development of traditional pharmacophore models follows a well-established workflow that heavily relies on expert knowledge and chemical intuition. This process typically encompasses several distinct phases [4]:

Training Set Selection: A structurally diverse set of molecules, including both active and inactive compounds, is selected to ensure the model can discriminate effectively.

Conformational Analysis: For each molecule, a set of low-energy conformations is generated, which should include the bioactive conformation.

Molecular Superimposition: All combinations of the low-energy conformations are superimposed, focusing on fitting similar functional groups common to all active molecules.

Abstraction: The superimposed molecules are transformed into an abstract representation, where specific chemical groups are designated as pharmacophore elements like 'aromatic ring' or 'hydrogen-bond donor'.

Validation: The model is validated by its ability to account for biological activities of known molecules and predict new actives.

The limitations of this approach include its dependency on human expertise, potential for bias, and limited capacity to process complex, high-dimensional data from modern ultra-large chemical libraries [2].

Informacophore Framework

The informacophore framework represents a significant evolution from traditional methods, positioning itself as the minimal chemical structure combined with computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations essential for biological activity [2]. This approach addresses key limitations of traditional pharmacophores through several fundamental advancements:

Data Integration: Informacophores leverage both internal and external data sources, including public repositories like ChEMBL and PubChem, to build comprehensive knowledge bases that far exceed human processing capacity [1].

Machine Learning Integration: By feeding essential molecular features into complex ML models, informacophores achieve greater predictive power, though this can introduce challenges in model interpretability [2].

Bias Reduction: The data-driven nature of informacophores significantly reduces biased intuitive decisions that may lead to systemic errors in traditional medicinal chemistry [2].

Automation Potential: Informacophore optimization through analysis of ultra-large datasets enables automation of standard development processes, parallelly accelerating drug discovery [16].

Diagram 1: Comparative workflows of traditional pharmacophore versus data-driven informacophore modeling approaches, highlighting the fundamental methodological differences.

Quantitative Comparison and Performance Metrics

Rigorous validation studies demonstrate the distinct performance characteristics of traditional pharmacophore versus informacophore approaches. The quantitative pharmacophore activity relationship (QPhAR) paradigm exemplifies the data-driven methodology, enabling direct performance comparisons.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Traditional vs QPhAR-Refined Pharmacophore Models

| Data Source | Traditional Pharmacophore FComposite-Score | QPhAR-Based Pharmacophore FComposite-Score | QPhAR Model R² | QPhAR Model RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ece et al. (2015) | 0.38 | 0.58 | 0.88 | 0.41 |

| Garg et al. (2019) | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 0.56 |

| Ma et al. (2019) | 0.57 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.44 |

| Wang et al. (2016) | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.46 |

| Krovat et al. (2005) | 0.94 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.70 |

The QPhAR-based refined pharmacophores generally score better than traditional baseline pharmacophores on the FComposite-score, demonstrating superior discriminatory power in virtual screening [21]. However, a dependency on the quality of the underlying QPhAR models can be observed, with lower-performing QPhAR models generating less reliable refined pharmacophores.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Traditional Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

Objective: To develop a validated pharmacophore model using established ligand-based approaches.

Materials and Methods:

Dataset Curation:

- Collect 20-50 compounds with known biological activities (IC₅₀ or Kᵢ values) against the target of interest.

- Ensure structural diversity while maintaining some common scaffold elements.

- Divide compounds into training (80%) and test sets (20%).

Conformational Analysis:

- Generate low-energy conformations for each compound using software such as LigandScout iConfGen [22].

- Apply molecular mechanics force fields (MMFF94, OPLS) for energy minimization.

- Set maximum conformations to 25-50 per molecule with energy window of 10-20 kcal/mol.

Molecular Superimposition:

- Select the most active compounds as alignment references.

- Perform systematic fitting of all combinations of low-energy conformations.

- Identify common steric and electronic features using clique detection algorithms.

Feature Abstraction and Model Generation:

- Convert aligned functional groups into abstract pharmacophore features:

- Hydrogen bond donors/acceptors

- Hydrophobic regions

- Aromatic rings

- Charged/ionizable groups

- Define spatial tolerances (typically 1.0-2.0 Å) for each feature.

- Convert aligned functional groups into abstract pharmacophore features:

Validation:

- Test model against external test set compounds.

- Evaluate using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and enrichment factors.

- Apply Cat-Scramble validation to assess statistical significance.

QPhAR-Based Informacophore Protocol

Objective: To develop a quantitative pharmacophore activity relationship model for predictive screening and optimization.

Materials and Methods:

Data Preparation:

- Curate dataset of 15-50 ligands with continuous activity values [21].

- Apply rigorous data curation: standardize activity measurements (IC₅₀, Kᵢ in nM), filter by assay type ('B' for binding), and target organism ('Homo sapiens') [22].

- Split data into training and test sets maintaining temporal or structural clustering.

Consensus Pharmacophore Generation:

- Generate input pharmacophores from all training samples.

- Create merged-pharmacophore (consensus model) representing common features across all active compounds.

Alignment and Feature Extraction:

- Align all input pharmacophores to the consensus model.

- Extract positional information relative to merged-pharmacophore features.

- Calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints for each aligned pharmacophore.

Machine Learning Model Training:

- Utilize positional and descriptor data as input features for ML algorithms.

- Implement partial least squares (PLS) regression or more advanced ensemble methods.

- Apply five-fold cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters and prevent overfitting.

Model Validation and Application:

- Validate on held-out test set using RMSE and R² metrics.

- Deploy refined pharmacophore for virtual screening of large compound databases.

- Rank screening hits by predicted activity values from QPhAR model.

Successful implementation of pharmacophore and informacophore approaches requires specialized computational tools and data resources. This section details essential components of the modern molecular informatics toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Pharmacophore and Informacophore Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Key Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | LigandScout [22], PHASE [6], Catalyst/Discovery Studio [21] | Pharmacophore perception, 3D modeling, virtual screening | Traditional pharmacophore development |

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL [1] [22], PubChem Bioassay [1], Enamine (65B compounds) [2] | Compound structures, bioactivity data, make-on-demand libraries | Data sourcing for informacophore development |

| Conformational Analysis | iConfGen [22], MOE | Low-energy conformation generation | Both traditional and data-driven approaches |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Descriptor calculation, predictive modeling, feature importance | Informacophore optimization |

| Validation Tools | ROCS, DUD-E dataset | Decoy generation, model validation, performance assessment | Method comparison and benchmarking |

Case Studies and Practical Applications

Automated Pharmacophore Optimization with QPhAR

A recent breakthrough in data-driven pharmacophore modeling demonstrates the power of automated feature selection using SAR information extracted from validated QPhAR models [21]. This approach addresses the fundamental limitation of traditional pharmacophore development: the manual, expert-dependent process of feature selection and refinement.

In a case study on the hERG K⁺ channel using the dataset from Garg et al., researchers implemented a fully automated end-to-end workflow that [21]:

- Generated a refined pharmacophore directly from a trained QPhAR model without requiring additional data

- Achieved a FComposite-score of 0.40 compared to 0.00 for traditional shared pharmacophore approaches

- Enabled virtual screening and hit ranking with quantitative activity predictions

This methodology represents a significant advancement over traditional heuristic-based pharmacophore refinement, which often depends on arbitrary activity cutoff values and subjective feature selection [21].

Data-Driven Medicinal Chemistry in Pharmaceutical R&D

A comprehensive pilot study at Daiichi Sankyo Company quantified the impact of integrating data science into practical medicinal chemistry [3]. The implementation of a Data-Driven Drug Discovery (D4) group demonstrated substantial improvements in project efficiency and outcomes:

SAR Visualization: Implementation of data analytics and visualization tools reduced the time required for structure-activity relationship analysis by 95% compared to traditional R-group table approaches [3].

Predictive Modeling: While under-utilized initially, predictive modeling approaches contributed significantly to intellectual property generation despite lower utilization rates [3].

Educational Transformation: The "D4 medicinal chemist" program successfully trained traditional medicinal chemists in advanced computational skills, creating hybrid experts capable of bridging both domains [3].

Diagram 2: Automated QPhAR-driven pharmacophore optimization workflow, demonstrating the data-driven approach to enhanced model discrimination and screening efficiency.

The evolution from traditional pharmacophore to data-driven informacophore models represents a fundamental paradigm shift in medicinal chemistry. While pharmacophores remain valuable as abstract representations of molecular interaction capacities, informacophores extend this concept by integrating computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations [2]. This integration enables more systematic and bias-resistant strategies for scaffold modification and optimization.

The future of molecular recognition modeling lies in hybrid approaches that leverage the interpretability of traditional pharmacophores with the predictive power of data-driven informacophores. As the field advances, successful implementation will require close collaboration between medicinal chemists and data scientists, enhanced educational programs to develop hybrid expertise, and continued development of computational infrastructures capable of processing ultra-large chemical datasets [1] [3]. Through these advancements, informacophore approaches promise to significantly reduce biased intuitive decisions, accelerate drug discovery processes, and ultimately improve clinical success rates in pharmaceutical development.

Building and Applying Informacophores: AI, Workflows, and Real-World Impact

Leveraging Ultra-Large Virtual and 'Make-on-Demand' Chemical Libraries

The field of medicinal chemistry is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from intuition-based design to quantitative, data-driven decision-making. This paradigm shift is critical for navigating the immense scale of modern chemical space, which is estimated to contain between 10^50 and 10^80 possible compounds—a number approaching the total atoms in the universe [23]. Within this nearly infinite chemical space, ultra-large virtual and "make-on-demand" chemical libraries have emerged as powerful resources for hit identification and optimization. These libraries, often comprising billions to trillions of synthetically accessible compounds, represent a fundamental shift from traditional screening collections that were limited to physically available molecules [24].

Framed within the broader thesis of informacophores—the minimal chemical structure combined with computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations essential for biological activity—these massive libraries provide the foundational data required for meaningful pattern recognition [16]. Unlike traditional pharmacophore models rooted in human-defined heuristics, informacophores leverage data-driven insights derived from structure-activity relationships (SARs) and machine learning representations of chemical structure. This approach enables a more systematic and bias-resistant strategy for scaffold modification and optimization, positioning informacophore analysis as the critical methodological bridge between massive chemical libraries and actionable medicinal chemistry insights [16].

The Landscape of Ultra-Large Chemical Libraries

Ultra-large chemical libraries represent a fundamental shift from traditional screening collections, moving from physically available compounds to virtually accessible, synthetically tractable molecules. These libraries are not exhaustively enumerated but are generated combinatorially from building blocks and reaction rules, enabling coverage of astronomical chemical space while maintaining synthetic accessibility [24].

Key Commercial Chemical Spaces

Table 1: Major Commercial "Make-on-Demand" Chemical Libraries

| Library Name | Provider | Size (No. of Compounds) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| eXplore | eMolecules | 5.0 trillion | Largest commercial space; DIY building blocks or synthesized compounds [24] |

| xREAL | Enamine/BioSolveIT | 4.4 trillion | Exclusive access via infiniSee; >80% synthesis success rate [24] |

| Synple Space | Synple Chem | 1.0 trillion | Cartridge-based, automation-ready synthesis [24] |

| KnowledgeSpace | BioSolveIT | 260 trillion | Literature-driven; virtual space for ideation [24] |

| FREEDOM Space 4.0 | Chemspace | 142 billion | ML-based filtering of building blocks; >80% synthesis success [24] |

| AMBrosia | Ambinter/Greenpharma | 125 billion | Favorable physicochemical properties for early discovery [24] |

| REAL Space | Enamine | 83 billion | Based on 172 in-house reactions; drug-like properties [24] |

| GalaXi | WuXi LabNetwork | 25.8 billion | Rich in sp³ motifs; diverse scaffolds [24] |

| CHEMriya | OTAVA | 55 billion | Unique ring-closing reactions; beyond rule-of-five entries [24] |

These combinatorial libraries surpass the constraints of traditional enumerated compound collections by dynamically generating compounds during searches, delivering only relevant results that are synthetically accessible or purchasable [24]. The "make-on-demand" nature of these libraries means that compounds identified through virtual screening can be synthesized and delivered within weeks, typically achieving synthesis success rates exceeding 80% [24].

Informacophores: The Theoretical Foundation for Navigating Chemical Space

The concept of informacophores represents an evolution from traditional pharmacophore models, integrating data-driven insights with structural chemistry to identify minimal chemical features essential for biological activity [16]. While classical pharmacophores rely on human-defined heuristics and chemical intuition, informacophores incorporate computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations of chemical structure, enabling more systematic and bias-resistant strategies for scaffold modification and optimization [16].

Informacophores function as a "skeleton key" that identifies molecular features triggering biological responses across diverse chemical scaffolds [16]. This approach is particularly valuable when analyzing ultra-large chemical libraries, where human capacity to process structural information reaches its limits. By leveraging machine learning algorithms that can process vast information repositories rapidly and accurately, informacophores can identify hidden patterns beyond the capacity of even expert medicinal chemists [16]. The development of ultra-large, "make-on-demand" virtual libraries has created both the opportunity and necessity for informacophore approaches, as these massive chemical spaces require computational guidance to navigate effectively toward biologically relevant regions [16].

Informacophore Conceptualization and Relationship to Chemical Space

The informacophore concept bridges massive chemical spaces with experimentally validated lead compounds through iterative computational and experimental cycles. This approach significantly reduces biased intuitive decisions that may lead to systemic errors while accelerating drug discovery processes [16].

Practical Implementation: Methodologies for Leveraging Ultra-Large Libraries

Active Learning for Efficient Library Screening

Active learning provides a strategic framework for navigating ultra-large chemical spaces when computational scoring functions are too expensive to apply exhaustively. This machine learning method iteratively selects the most informative compounds for scoring, dramatically reducing computational requirements [23].

Protocol: Active Learning Implementation for Virtual Screening

Initialization Phase:

- Select a random reference compound from the virtual library

- Choose a random sample of unlabeled data for initial scoring

- Label these initial compounds using the expensive scoring function (e.g., molecular docking, LogP calculation)

- Train an initial machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest Regressor) on these labeled data points [23]

Iterative Active Learning Cycle:

- Use the current ML model to score the entire virtual library

- Select the top-scoring compounds (based on model predictions) that lack experimental labels

- Apply the expensive scoring function to these selected compounds

- Add the newly labeled compounds to the training set

- Re-train the ML model on the expanded training set

- Repeat for a predetermined number of rounds or until convergence [23]

Early Stopping Criteria:

- Implement early termination if the optimal value is known and achieved

- Stop if performance plateaus across multiple iterations

- Define maximum computational budget as a stopping criterion [23]

Table 2: Active Learning Components and Their Functions

| Component | Implementation Example | Function in Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Expensive Scoring Function | Molecular docking, LogP calculation | Provides accurate but computationally costly compound evaluation |

| Machine Learning Model | Random Forest Regressor | Fast approximation of scoring function for entire library |

| Selection Strategy | Top-k scoring compounds | Identifies most promising candidates for expensive scoring |

| Fingerprint Representation | Morgan fingerprints (radius=2) | Encodes molecular structure for machine learning |

| Iteration Control | Fixed rounds or convergence criteria | Balances exploration and exploitation while managing resources |

This protocol enables efficient exploration of ultra-large libraries by focusing computational resources on the most promising regions of chemical space. For example, where exhaustive screening of a 48-billion compound library might take 32 years at one second per compound, active learning can identify optimal compounds with only a fraction of this computational expense [23].

Virtual Screening Hit Identification Criteria

Establishing appropriate hit identification criteria is crucial for successful virtual screening campaigns. Analysis of published virtual screening results between 2007-2011 reveals that only approximately 30% of studies reported clear, predefined hit cutoffs, with no consensus on selection criteria [25]. The majority of studies employed activity cutoffs in the low to mid-micromolar range (1-100 μM), with only rare use of sub-micromolar thresholds [25].

Recommended hit identification criteria should include:

- Size-Targeted Ligand Efficiency: Normalize activity by molecular size using metrics such as ligand efficiency (LE ≥ 0.3 kcal/mol/heavy atom) [25]

- Activity Thresholds: Set realistic cutoffs based on project goals (typically 1-25 μM for lead-like compounds) [25]

- Multi-Parameter Optimization: Consider additional properties including selectivity, solubility, and chemical tractability

- Experimental Validation: Include orthogonal assays, binding confirmation, and counter-screens to verify mechanism and specificity [25]

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ultra-Library Screening

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Services | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Spaces | eXplore, xREAL, REAL Space, GalaXi | Provide access to ultra-large compound collections for virtual screening [24] |

| Screening Software | infiniSee (Scaffold Hopper, Analog Hunter, Motif Matcher) | Enable navigation of chemical spaces using various similarity algorithms [24] |

| Building Block Suppliers | Enamine, WuXi, OTAVA, Ambinter | Source starting materials for combinatorial library synthesis [24] |

| Make-on-Demand Services | Synple Chem, Enamine, Chemspace | Translate virtual hits to tangible compounds through rapid synthesis [24] |

| Data Analysis Platforms | RDKit, Scikit-learn, Custom Python scripts | Process chemical data, implement machine learning models, and analyze results [23] |

| Biological Assay Services | CROs with HTS, binding, and functional assay capabilities | Experimentally validate computational predictions and establish SAR [16] |

Experimental Workflow for Informacophore-Driven Discovery