In Silico Chemogenomics: The AI-Powered Future of Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of in silico chemogenomics, a discipline that systematically identifies small molecules for protein targets using computational tools.

In Silico Chemogenomics: The AI-Powered Future of Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of in silico chemogenomics, a discipline that systematically identifies small molecules for protein targets using computational tools. It covers foundational concepts, core methodologies like machine learning and molecular docking, and their application in virtual screening and polypharmacology. The content also addresses critical challenges such as data sparsity and model validation, offering troubleshooting strategies. Finally, it explores validation frameworks and comparative analyses of state-of-the-art tools, presenting a forward-looking perspective on how integrating AI and high-quality data is transforming drug discovery for researchers and development professionals.

The Foundations of Chemogenomics: Bridging Chemical and Biological Space

Defining In Silico Chemogenomics and Its Role in Modern Drug Discovery

In silico chemogenomics represents a powerful, interdisciplinary strategy at the intersection of computational biology and chemical informatics. It aims to systematically identify interactions between small molecules and biological targets on a large scale. The core objective of chemogenomics is the exploration of the entire pharmacological space, seeking to characterize the interaction of all possible small molecules with all potential protein targets [1] [2]. However, experimentally testing this vast interaction matrix is an impossible task due to the sheer number of potential small molecules and biological targets. This is where computational approaches, collectively termed in silico chemogenomics, become indispensable [1]. These methods leverage advancements in computer science, including cheminformatics, molecular modelling, and artificial intelligence, to analyze millions of potential interactions in silico. This computational prioritization rationally guides subsequent experimental testing, significantly reducing the associated time and costs [1] [3].

The paradigm has become crucial in modern pharmacological research and drug discovery by enabling the identification of novel bioactive compounds and therapeutic targets, elucidating the mechanisms of action of known drugs, and understanding polypharmacology—the phenomenon where a single drug binds to multiple targets [1] [4]. The growing availability of large-scale public bioactivity databases, such as ChEMBL, PubChem, and DrugBank, has provided the essential fuel for the development and refinement of these computational models, opening the door to sophisticated machine learning and AI applications [1] [5].

Key Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Target Prediction Using an Ensemble Chemogenomic Model

Target prediction is a fundamental application of in silico chemogenomics, crucial for identifying the protein targets of a small molecule, which can reveal therapeutic potential and off-target effects early in the discovery process [4].

1. Principle: This protocol uses an ensemble chemogenomic model that integrates multi-scale information from both chemical structures and protein sequences to predict compound-target interactions. The underlying hypothesis is that similar compounds are likely to interact with similar targets, and this relationship can be learned by models that simultaneously consider both the chemical and biological spaces [4] [6].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Query Compound: The small molecule of unknown target profile.

- Target Database: A comprehensive database of protein targets (e.g., 859 human targets from ChEMBL27) [4].

- Training Data: A large dataset of known compound-target interactions with associated bioactivity data (e.g., Ki ≤ 100 nM for positive set, Ki > 100 nM for negative set) sourced from public databases like ChEMBL and BindingDB [4].

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Data Preparation and Representation.

- Represent the query compound using multiple molecular descriptors. Common descriptors include:

- Mol2D Descriptors: A set of 188 2D molecular descriptors capturing constitutional, topological, charge, and other properties [4].

- ECFP4 (Extended Connectivity Fingerprint): A circular fingerprint that captures molecular features within a bond diameter of 4, providing a representation of the molecule's topology [4].

- Represent each protein target in the database using protein descriptors. Common descriptors include:

- Protein Sequence Descriptors: Information derived directly from the amino acid sequence.

- Gene Ontology (GO) Terms: Annotations from the GO database covering Biological Process (BP), Molecular Function (MF), and Cellular Component (CC) [4].

- Represent the query compound using multiple molecular descriptors. Common descriptors include:

- Step 2: Model Construction and Training.

- Construct multiple individual chemogenomic models. Each model takes a vector of descriptors representing a single compound-target pair as input and outputs a probability score indicating the likelihood of an interaction [4].

- Combine these individual models into an ensemble model. The ensemble approach integrates predictions from models built on different descriptor sets, improving overall robustness and predictive performance. The best-performing ensemble model is selected as the final predictor [4].

- Step 3: Target Prediction and Ranking.

- Create a set of compound-target pairs by combining the query compound with every protein target in the database.

- Input each pair into the trained ensemble model to obtain an interaction probability score.

- Rank all targets based on their scores. The top-k (e.g., top 1 to top 10) ranked targets are considered the most likely potential targets for the query compound [4].

4. Validation: Performance is typically validated using stratified tenfold cross-validation and external datasets. Key performance metrics include the fraction of known targets identified in the top-k list. For example, one model achieved a 26.78% success rate for top-1 predictions and 57.96% for top-10 predictions, representing approximately 230-fold and 50-fold enrichments, respectively [4].

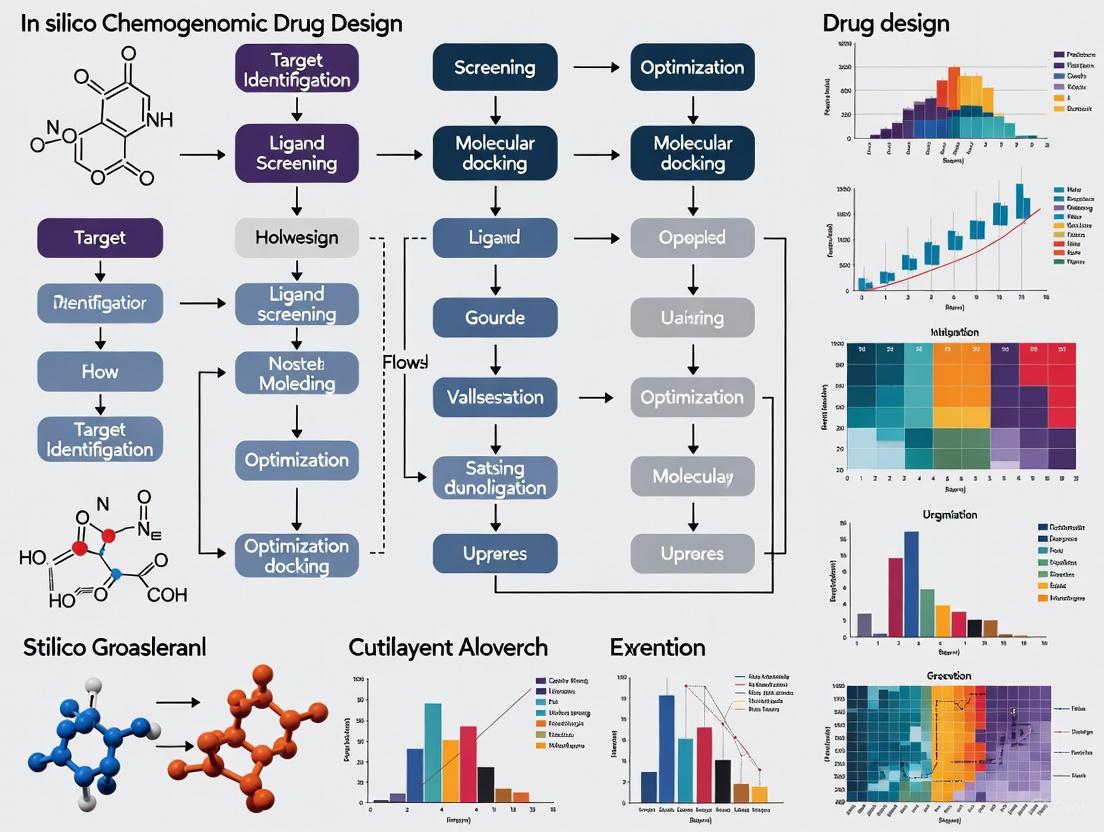

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-step process:

Protocol 2: An Integrated Pipeline for Polypharmacology and Affinity Prediction

This protocol describes an integrated approach that combines qualitative target prediction with quantitative proteochemometric (PCM) modelling to simultaneously predict a compound's polypharmacology and its binding affinity/potency against specific targets [7].

1. Principle: The pipeline first uses a Bayesian target prediction algorithm to qualitatively assess the potential interactions between a compound and a panel of targets. Subsequently, quantitative PCM models are employed to predict the binding affinity or potency of the compound for the identified targets. PCM is a technique that correlates both compound and target descriptors to bioactivity values, building a single model for an entire protein family [7].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Query Compound(s): The small molecule(s) of interest.

- Qualitative Target Prediction Model: A model trained on a large network of ligand-target associations (e.g., 553,084 associations covering 3,481 targets) [7].

- Quantitative PCM Model: A model trained on a dataset comprising multiple related target sequences (e.g., 20 DHFR sequences) and distinct compounds (e.g., 1,505 compounds) with associated bioactivity data (e.g., pIC50) [7].

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Qualitative Polypharmacology Prediction.

- Input the query compound into the Bayesian target prediction model.

- The model calculates and returns the probability of interaction between the compound and each target in its panel, providing a qualitative polypharmacology profile [7].

- Step 2: Quantitative Potency Prediction.

- For targets identified in Step 1, use the pre-trained PCM model to predict the binding affinity or potency (e.g., pIC50) of the compound.

- The PCM model utilizes combined descriptors of the compound and the specific target sequence to make a quantitative prediction, outperforming models based solely on compound or target information [7].

- Step 3: Data Integration and Analysis.

- Integrate the results from both models. Compounds identified as active by both the qualitative target predictor and the quantitative PCM model (with a predicted potency above a chosen threshold) are considered high-confidence hits for experimental validation [7].

4. Validation: In a retrospective study on Plasmodium falciparum DHFR inhibitors, the qualitative model achieved a recall of 79% and precision of 100%. The quantitative PCM model exhibited high predictive power with R² test values of 0.79 and RMSEtest of 0.59 pIC50 units [7].

The integrated nature of this pipeline is visualized below:

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

The performance of in silico chemogenomics methods is rigorously evaluated using cross-validation and external test sets. The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from recent studies for easy comparison.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of In Silico Chemogenomics Methods

| Method / Study | Application / Target | Key Performance Metrics | Outcome / Enrichment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble Chemogenomic Model [4] | General target prediction for 859 human targets | Fraction of known targets identified in top-k list: 26.78% (Top-1), 57.96% (Top-10) | ~230-fold (Top-1) and ~50-fold (Top-10) enrichment over random |

| Integrated PCM & Target Prediction [7] | Prediction of Plasmodium falciparum DHFR inhibitors | Qualitative recall: 79%, Precision: 100%. Quantitative PCM: R² test = 0.79, RMSEtest = 0.59 pIC50 | Outperformed models using only compound or target information |

| Ligand-Based VS for GPCRs [6] | Virtual screening of G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) | Accurate prediction of ligands for GPCRs with known ligands and orphan GPCRs | Estimated 78.1% accuracy for predicting ligands of orphan GPCRs |

Successful implementation of in silico chemogenomics protocols relies on a suite of well-curated data resources and software tools. The following table details key reagents and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for In Silico Chemogenomics

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Protocols | Relevant Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL [4] [5] | Bioactivity Database | Source of curated ligand-target interaction data for model training and validation. | Protocol 1, Protocol 2 |

| PubChem [5] | Bioactivity Database | Large repository of compound structures and bioassay data, including inactive compounds. | Protocol 1 |

| ExCAPE-DB [5] | Integrated Dataset | Pre-integrated and standardized dataset from PubChem and ChEMBL for Big Data analysis; facilitates access to a large chemogenomics dataset. | Protocol 1 |

| UniProt [4] | Protein Database | Source of protein sequence and functional annotation (e.g., Gene Ontology terms) for target representation. | Protocol 1 |

| Open PHACTS Discovery Platform [8] | Data Integration Platform | Integrates compound, target, pathway, and disease data from multiple sources; used for annotating phenotypic screening hits and target validation. | Protocol 2 (Annotation) |

| IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY [8] | Pharmacological Database | Provides curated information on drug targets and their prescribed ligands; used for selecting selective probe compounds. | Protocol 2 (Validation) |

| Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) [9] | Drug Target Database | Provides information about known therapeutic protein and nucleic acid targets; used for drug repositioning studies. | Drug Repositioning |

| DrugBank [4] [9] | Drug Database | Contains comprehensive molecular information about drugs, their mechanisms, and targets. | Protocol 1, Drug Repositioning |

In silico chemogenomics has firmly established itself as a cornerstone of modern drug discovery. By providing a systematic computational framework to explore the complex interplay between chemical and biological spaces, it directly addresses critical challenges such as target identification, polypharmacology prediction, and drug repurposing. The protocols outlined here—from ensemble-based target prediction to integrated qualitative-quantitative pipelines—offer researchers detailed methodologies to leverage this powerful strategy. As the volume and quality of public chemogenomics data continue to grow, and machine learning algorithms become increasingly sophisticated, the accuracy and scope of in silico chemogenomics will only expand. This progression promises to further accelerate the efficient and rational discovery of new therapeutic agents, solidifying the discipline's role as an indispensable component of pharmacological research.

The pharmaceutical industry faces a profound innovation crisis, characterized by a 96% overall failure rate in drug development [10]. This inefficiency is a primary driver behind the soaring costs of new medicines, with the journey from preclinical testing to final approval often taking over 12 years and costing more than $2 billion [11]. A staggering 40-50% of clinical failures are attributed to lack of clinical efficacy, while 30% result from unmanageable toxicity [12]. This article examines how in silico chemogenomic approaches—the systematic computational analysis of interactions between small molecules and biological targets—can help overcome these challenges by improving target validation, candidate optimization, and predictive toxicology.

Quantitative Analysis of the Drug Development Pipeline

The following table summarizes key challenges and corresponding chemogenomic solutions across the drug development pipeline:

Table 1: Drug Development Challenges and Chemogenomic Solutions

| Development Stage | Primary Challenge | In Silico Chemogenomic Solution | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | High false discovery rate (92.6%) in preclinical research [10] | Genomic-wide association studies (GWAS) & target fishing [10] [13] | Reverses probability of late-stage failure [10] |

| Lead Optimization | Over-reliance on structure-activity relationship (SAR) overlooking tissue exposure [12] | Structure-tissue exposure/selectivity-activity relationship (STAR) [12] | Balances clinical dose/efficacy/toxicity [12] |

| Preclinical Testing | Poor predictive ability of animal models for human efficacy [12] | Virtual screening & molecular dynamics simulations [3] | Reduces time/costs, prioritizes experimental tests [1] [3] |

| Clinical Development | Lack of efficacy (40-50%) and unmanageable toxicity (30%) [12] | Drug repurposing & in silico toxicology predictions [1] | Identifies novel bioactive compounds and mechanisms [1] |

The crisis extends beyond scientific challenges to economic sustainability. Pharmaceutical companies increasingly face diminishing returns on capital investment, prompting a shift toward acquiring innovations from external sources rather than internal R&D [14]. This "productivity-cost paradox" – where increased R&D spending does not correlate with more approved drugs – has led to the emergence of asset-integrating pharma company (AIPCO) models adopted by industry leaders like Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and AbbVie [14].

Chemogenomic Approaches to Target Identification & Validation

The Genomics Advantage

Human genomics represents a transformative approach for target identification. Where traditional preclinical studies suffer from a 92.6% false discovery rate, genome-wide association studies offer a more reliable foundation because they "rediscovered the known treatment indication or mechanism-based adverse for around 70 of the 670 known targets of licensed drugs" [10]. This approach systematically interrogates every potential druggable target concurrently in the correct organism – humans – while exploiting the naturally randomized allocation of genetic variants that mimics randomized controlled trial design [10].

In Silico Target Fishing

Computational target fishing technologies enable researchers to "predict new molecular targets for known drugs" and "identify compound-target associations by combining bioactivity profile similarity search and public databases mining" [13]. This approach is particularly valuable for drug repurposing, where existing drugs can be rapidly evaluated against new disease indications. The process involves screening compounds against chemogenomic databases using multiple-category Bayesian models to identify potential target interactions, significantly expanding the potential therapeutic utility of existing chemical entities [13].

Experimental Protocols for In Silico Drug Design

Protocol 1: Virtual Screening for Novel Inhibitors

Purpose: To identify novel inhibitors of disease-associated protein targets through computational screening. Application Example: Identification of inhibitors for Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1-R132C), an oncogenic metabolic enzyme [3].

- Library Preparation: Curate a diverse chemical library (e.g., 1.5 million commercial synthetic compounds) in appropriate format for docking [3].

- Protein Preparation: Obtain 3D structure of target protein (IDH1-R132C mutant). Perform energy minimization and optimize protonation states.

- Molecular Docking: Conduct docking-based virtual screening using software such as AutoDock Vina or Glide.

- Post-Docking Analysis: Rank compounds by docking score and binding pose. Cluster results and select top candidates for further evaluation.

- Cellular Inhibition Assays: Experimentally validate top computational hits (e.g., T001-0657 for IDH1-R132C) in relevant cellular models [3].

- Molecular Dynamics Validation: Perform MD simulations (100-200 ns) and free energy calculations to confirm binding stability and mechanism [3].

Protocol 2: Multi-QSAR Modeling for Compound Optimization

Purpose: To characterize and optimize lead compounds through quantitative structure-activity relationship modeling. Application Example: Characterization of aryl benzoyl hydrazide derivatives as H5N1 influenza virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors [3].

- Dataset Curation: Compile experimental bioactivity data for compound series (30+ derivatives recommended).

- Descriptor Calculation: Generate comprehensive set of molecular descriptors (topological, electronic, steric).

- 2D-QSAR Model Development: Use partial least squares or machine learning regression to correlate descriptors with activity.

- 3D-QSAR Model Development: Perform comparative molecular field analysis (CoMFA) or comparative molecular similarity indices analysis (CoMSIA).

- Pharmacophore Modeling: Generate structure-based pharmacophore model from protein-ligand complexes.

- Model Validation: Use leave-one-out cross-validation and external test sets to validate predictive power.

Protocol 3: Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity-Activity Relationship (STAR)

Purpose: To classify drug candidates based on both potency/selectivity and tissue exposure/selectivity for improved clinical success [12].

- Tissue Exposure Profiling: Determine drug exposure in disease versus normal tissues using advanced PK/PD modeling.

- Selectivity Assessment: Evaluate target specificity against related target families (e.g., kinase panels).

- STAR Classification:

- Class I: High specificity/potency + high tissue exposure/selectivity (needs low dose, superior efficacy/safety)

- Class II: High specificity/potency + low tissue exposure/selectivity (requires high dose, high toxicity)

- Class III: Adequate specificity/potency + high tissue exposure/selectivity (low dose, manageable toxicity)

- Class IV: Low specificity/potency + low tissue exposure/selectivity (inadequate efficacy/safety, terminate early) [12]

- Dose Optimization: Based on STAR classification, optimize clinical dose regimen to balance efficacy/toxicity.

Visualization of Key Workflows

In Silico Chemogenomic Drug Discovery Pipeline

STAR Classification Framework for Lead Optimization

Virtual Screening & Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Databases

Table 2: Key Research Reagents & Databases for Computational Chemogenomics

| Resource Type | Name | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL [13] | Bioactivity data for drug-like molecules, target annotations |

| DrugBank [13] | Comprehensive drug-target interaction data | |

| Target Databases | Therapeutic Target Database [13] | Annotated disease targets and targeted drugs |

| Potential Drug Target Database [13] | Focused on potential drug targets | |

| Computational Tools | Docking Software (AutoDock, Glide) | Structure-based virtual screening |

| QSAR Modeling Software | Predictive activity modeling from chemical structure | |

| Molecular Dynamics (GROMACS, AMBER) | Simulation of protein-ligand interactions over time | |

| Specialized Platforms | DBPOM [3] | Database of pharmaco-omics for cancer precision medicine |

| TarFisDock [13] | Web server for identifying drug targets via docking |

The drug discovery crisis demands integrated solutions that leverage the full potential of in silico chemogenomic approaches. By systematically implementing GWAS for target identification, virtual screening for compound selection, STAR frameworks for lead optimization, and rigorous computational validation through molecular dynamics and QSAR modeling, researchers can significantly improve the probability of clinical success. The future of drug discovery lies in the intelligent integration of these computational approaches with experimental validation, creating a more efficient, predictive, and cost-effective pipeline for delivering innovative therapies to patients.

Chemogenomics is a systematic approach in drug discovery that involves screening targeted chemical libraries of small molecules against entire families of drug targets, such as GPCRs, nuclear receptors, kinases, and proteases. The primary goal is the parallel identification of novel drugs and drug targets, leveraging the completion of the human genome project which provided an abundance of potential targets for therapeutic intervention [15]. This field represents a significant shift from traditional "one-compound, one-target" approaches, instead studying the intersection of all possible drugs on all potential targets.

The fundamental strategy of chemogenomics integrates target and drug discovery by using active compounds (ligands) as probes to characterize proteome functions. The interaction between a small compound and a protein induces a phenotype, allowing researchers to associate proteins with molecular events. Compared with genetic approaches, chemogenomics techniques can modify protein function rather than genes and observe interactions in real-time, including reversibility after compound withdrawal [15].

Core Methodological Approaches

Forward and Reverse Chemogenomics

Current experimental chemogenomics employs two distinct approaches, each with specific applications and workflows [15]:

Forward Chemogenomics (Classical Approach):

- Begins with the study of a particular phenotype where the molecular basis is unknown

- Identifies small compounds that interact with this function

- Uses identified modulators as tools to identify the protein responsible for the phenotype

- Main challenge lies in designing phenotypic assays that lead immediately from screening to target identification

Reverse Chemogenomics:

- Identifies small compounds that perturb the function of a specific enzyme in controlled in vitro tests

- Analyzes the phenotype induced by the molecule in cellular or whole-organism tests

- Confirms the role of the enzyme in the biological response

- Enhanced by parallel screening and the ability to perform lead optimization on multiple targets within one family

Table 1: Comparison of Chemogenomics Approaches

| Aspect | Forward Chemogenomics | Reverse Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Phenotype with unknown molecular basis | Known enzyme or protein target |

| Screening Method | Phenotypic assays on cells or organisms | In vitro enzymatic tests |

| Primary Goal | Identify protein responsible for phenotype | Validate biological role of known target |

| Challenge | Designing assays for direct target identification | Connecting in vitro results to physiological relevance |

| Throughput Capability | Moderate, due to complex phenotypic readouts | High, enabled by parallel screening |

In Silico Chemogenomic Models

Modern chemogenomics increasingly relies on computational approaches, particularly chemogenomic models that combine protein sequence information with compound-target interaction data. These models utilize both ligand and target spaces to extrapolate compound bioactivities, addressing limitations of traditional machine learning methods that consider only ligand information [4].

Advanced implementations use ensemble models incorporating multi-scale information from chemical structures and protein sequences. By combining descriptors representing compound-target pairs as input, these models predict interactions between compounds and targets, with scores indicating association probabilities. This approach allows target prediction by screening a compound against a target database and ranking potential targets by these scores [4].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Ensemble Chemogenomic Models

| Validation Method | Top-1 Prediction Accuracy | Top-10 Prediction Accuracy | Enrichment Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stratified Tenfold Cross-Validation | 26.78% | 57.96% | ~230-fold (Top-1), ~50-fold (Top-10) |

| External Datasets (Natural Products) | Not Specified | >45% | Not Specified |

Experimental Protocols

Yeast Chemogenomic Profiling Protocol

This protocol is adapted from the genome-wide method for identifying gene products that functionally interact with small molecules in yeast, resulting in inhibition of cellular proliferation [16].

Materials and Reagents:

- Complete collection of heterozygous yeast deletion strains

- Compounds for screening (e.g., anticancer agents, antifungals, statins)

- Growth media appropriate for yeast strains

- Microtiter plates for high-throughput screening

- Plate readers for proliferation assessment

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation: Grow heterozygous yeast deletion strains to mid-log phase in appropriate media.

- Compound Exposure: Treat yeast strains with test compounds at appropriate concentrations in 96-well or 384-well format.

- Proliferation Monitoring: Measure cellular proliferation over 24-48 hours using optical density or metabolic activity assays.

- Data Collection: Record proliferation data for each strain-compound combination.

- Hit Identification: Identify gene deletions showing hypersensitivity or resistance to each compound.

- Validation: Confirm hits through secondary assays and dose-response curves.

Applications: This protocol has identified both previously known and novel cellular interactions for diverse compounds including anticancer agents, antifungals, statins, alverine citrate, and dyclonine. It has also revealed that cells may respond similarly to compounds of related structure, enabling identification of on-target and off-target effects in vivo [16].

In Silico Target Prediction Protocol

This protocol describes the computational prediction of small molecule targets using ensemble chemogenomic models based on multi-scale information of chemical structures and protein sequences [4].

Data Collection and Preparation:

- Target Selection: Collect human target proteins from databases such as ChEMBL. The protocol described 859 human targets covering kinases, GPCRs, proteases, enzymes, and other categories.

- Compound-Target Interactions: Extract bioactivity data (Ki values) from BindingDB and ChEMBL databases. Use a threshold of 100 nM Ki to define positive (Ki ≤ 100 nM) and negative (Ki > 100 nM) samples.

- Data Curation: Resolve multiple bioactivity values for the same compound-target pair by taking the median if differences are below one magnitude; exclude pairs with differences exceeding one magnitude.

Descriptor Calculation:

- Molecular Descriptors: Calculate three types of compound descriptors:

- 188 Mol2D descriptors (molecular constitutional, topological, connectivity indices, etc.)

- Extended Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP4)

- Additional structural descriptors capturing comprehensive chemical space

- Protein Descriptors: Calculate descriptors representing:

- Physicochemical properties

- Protein sequence information

- Gene Ontology (GO) terms covering biological process, molecular function, and cellular component

Model Training and Validation:

- Model Construction: Build multiple chemogenomic models using different descriptor combinations and machine learning algorithms.

- Ensemble Development: Combine individual models to create an ensemble model with superior prediction performance.

- Performance Validation: Validate using stratified tenfold cross-validation and external datasets including natural products.

- Target Prediction: For a query compound, generate compound-target pairs with all potential targets, input to the model, and rank targets by predicted interaction scores.

Visualization of Chemogenomic Workflows

Forward and Reverse Chemogenomics Pathways

In Silico Target Prediction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Chemogenomic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Heterozygous Yeast Deletion Collection | Genome-wide screening of gene-compound interactions | Complete set of deletion strains for functional genomics [16] |

| Targeted Chemical Libraries | Systematic screening against target families | Libraries focused on GPCRs, kinases, nuclear receptors, etc. [15] |

| Bioactivity Databases | Source of compound-target interaction data | ChEMBL, BindingDB, DrugBank, TTD [4] |

| Molecular Descriptors | Computational representation of chemical structures | Mol2D descriptors (188 types), ECFP4 fingerprints [4] |

| Protein Descriptors | Computational representation of protein targets | Sequence-based descriptors, Gene Ontology terms [4] |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Building predictive chemogenomic models | Ensemble models combining multiple descriptor types [4] |

Applications in Drug Discovery

Determining Mechanisms of Action

Chemogenomics has been successfully applied to identify mechanisms of action (MOA) for traditional medicines, including Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and Ayurveda. Compounds in traditional medicines often have "privileged structures" – chemical structures more frequently found to bind different living organisms – and comprehensively known safety profiles, making them attractive for lead structure identification [15].

In one case study on TCM, the therapeutic class of "toning and replenishing medicine" was evaluated. Target prediction programs identified sodium-glucose transport proteins and PTP1B (an insulin signaling regulator) as targets linking to the hypoglycemic phenotype. For Ayurvedic anti-cancer formulations, target prediction enriched for cancer progression targets like steroid-5-alpha-reductase and synergistic targets like the efflux pump P-gp [15].

Identifying Novel Drug Targets

Chemogenomics profiling enables identification of novel therapeutic targets through systematic approaches. In antibacterial development, researchers capitalized on an existing ligand library for the murD enzyme in peptidoglycan synthesis. Using chemogenomics similarity principles, they mapped the murD ligand library to other mur ligase family members (murC, murE, murF, murA, and murG) to identify new targets for known ligands [15].

Structural and molecular docking studies revealed candidate ligands for murC and murE ligases, with expected broad-spectrum Gram-negative inhibitor properties since peptidoglycan synthesis is exclusive to bacteria [15].

Biological Pathway Elucidation

Chemogenomics approaches have helped identify genes in biological pathways that remained mysterious despite years of research. For example, thirty years after diphthamide (a posttranslationally modified histidine derivative) was identified, chemogenomics discovered the enzyme responsible for the final step in its synthesis [15].

Researchers used Saccharomyces cerevisiae cofitness data – representing similarity of growth fitness under various conditions between deletion strains – to identify YLR143W as the strain with highest cofitness to strains lacking known diphthamide biosynthesis genes. Experimental confirmation showed YLR143W was the missing diphthamide synthetase [15].

Chemogenomics represents a powerful, systematic framework for identifying small molecule-target interactions that integrates experimental and computational approaches. The core principles of forward and reverse chemogenomics, combined with advanced in silico modeling using multi-scale chemical and protein information, provide robust methodologies for target identification, mechanism of action studies, and drug discovery. As chemogenomic databases expand and computational methods advance, this approach will continue to transform early drug discovery by efficiently connecting chemical space to biological function, ultimately reducing attrition rates in clinical development through better target validation and understanding of polypharmacology.

Exploring the Relevant Chemical and Biological Spaces for Novel Target Discovery

The discovery of novel therapeutic targets is a critical bottleneck in the drug development pipeline. Modern in silico chemogenomic approaches provide a powerful framework for systematically exploring the vast chemical and biological spaces to identify and validate new drug targets. These methodologies integrate heterogeneous data types—including genomic sequences, protein structures, ligand chemical features, and interaction networks—to predict novel drug-target interactions (DTIs) with high precision. This application note details practical protocols and computational strategies for leveraging chemogenomics in target discovery, underpinned by case studies and quantitative performance data from state-of-the-art machine learning models. The protocols are designed for researchers and scientists engaged in early-stage drug discovery, emphasizing reproducible, data-driven methodologies that reduce the time and cost associated with experimental target validation.

Chemogenomics represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, moving beyond the traditional "one drug, one target" hypothesis to a more holistic view of polypharmacology and systems biology. It is founded on the principle that similar targets often bind similar ligands, thereby enabling the prediction of novel interactions by extrapolating from known data [17] [18]. The core objective is to systematically map the interactions between the chemical space (encompassing all possible drug-like molecules) and the biological space (encompassing all potential protein targets) [19].

The impetus for this approach is clear: conventional drug discovery is often hampered by high costs, lengthy timelines, and a high attrition rate [20]. In silico methodologies, particularly computer-aided drug design (CADD), have demonstrated a significant impact by rationalizing the discovery process, reducing the need for random screening, and even decreasing experimental animal use [20]. Furthermore, the explosion of available biological and chemical data—from genomic sequences and protein structures to vast libraries of compound bioactivities—has made data-driven target discovery not just feasible, but indispensable [19] [21].

Exploring the chemogenomic space requires the integration of multiple data dimensions, which can be categorized as follows:

- Ligand-Based Information: Utilizing chemical structures, physicochemical properties, and known biological activities of small molecules to infer interactions with novel targets.

- Target-Based Information: Leveraging protein sequences, 3D structures, and functional annotations to identify potential binding sites for chemical ligands.

- Interaction Data: Employing known drug-target pairs, often sourced from public databases, to train machine learning models for predicting novel interactions.

- Network and Systems Biology Data: Incorporating protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks and pathway information to understand the context of a target within the cellular system and to assess potential therapeutic or side effects [22] [23].

This document provides detailed protocols for applying these principles through specific computational techniques, from foundational ligand- and structure-based methods to advanced integrative machine learning models.

Key Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Ligand-Based and Structure-Based Screening

Principle: Ligand-based methods operate on the principle of "chemical similarity," where molecules with similar structures are likely to share similar biological activities. Structure-based methods, conversely, rely on the 3D structure of a protein target to identify complementary ligands through molecular docking [20] [18].

Protocol 1: Ligand-Based Virtual Screening using Pharmacophore Modeling

- Define the Pharmacophore Model: Compile a set of known active ligands for a target of interest. Identify and align their common chemical features essential for biological activity (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, charged groups) using software such as MOE or Discovery Studio.

- Validate the Model: Test the model's ability to distinguish known actives from known inactives in a decoy set. Optimize feature definitions and tolerance settings to maximize enrichment.

- Screen Chemical Libraries: Use the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen large virtual compound libraries (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL). Compounds that fit the pharmacophore model are considered potential hits.

- Post-Screening Analysis: Subject the hit compounds to molecular docking (see Protocol 2) and further filtering based on drug-likeness (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) to create a final list for experimental testing.

Protocol 2: Structure-Based Virtual Screening using Molecular Docking

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or generate it via homology modeling. Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands. Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and define protonation states of residues at physiological pH.

- Binding Site Definition: Identify the binding site of interest, typically from the location of a co-crystallized native ligand or through computational binding site prediction tools.

- Ligand Preparation: Prepare the library of small molecules for docking by generating 3D structures, optimizing geometry, and assigning correct tautomeric and ionization states at pH 7.4.

- Molecular Docking: Perform docking simulations using software such as AutoDock Vina or GOLD. The software will generate multiple poses for each ligand within the defined binding site.

- Scoring and Ranking: Rank the generated poses based on a scoring function that estimates the binding affinity. Select the top-ranked compounds for further analysis and experimental validation.

Table 1: Summary of Key Virtual Screening Software

| Software/Tool | Methodology | Application | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular Docking | Structure-based virtual screening of ligand poses and affinity prediction. | Open Source |

| MOE | Pharmacophore Modeling, Docking | Ligand- and structure-based design, QSAR modeling. | Commercial |

| Schrödinger Suite | Molecular Docking (Glide) | High-throughput virtual screening and lead optimization. | Commercial |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics | Chemical similarity search, descriptor calculation, and molecule manipulation. | Open Source |

Proteochemometric and Machine Learning Modeling

Principle: Proteochemometric (PCM) models, a subset of chemogenomic methods, simultaneously learn from the properties of both compounds and proteins to predict interactions. This overcomes limitations of ligand- or target-only models, especially for proteins with few known ligands [19] [18].

Protocol 3: Building a Proteochemometric Model with Shallow Learning

- Data Curation: Collect a dataset of known drug-target interactions from databases like DrugBank, ChEMBL, or STITCH. Represent each (drug, target) pair with numerical descriptors.

- Compound Descriptors: Calculate molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, MACCS) or physicochemical descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP).

- Protein Descriptors: Use amino acid composition, dipeptide composition, or more advanced sequence-derived descriptors like auto-cross covariance (ACC) transformations.

- Feature Combination: For each interacting pair, create a unified feature vector by combining the compound and protein descriptors. A common method is the Kronecker product of their individual descriptor vectors [19].

- Model Training: Train a machine learning model, such as a Support Vector Machine (e.g., kronSVM) or a Regularized Matrix Factorization model (e.g., NRLMF), on the combined feature vectors to classify or rank potential interactions [19] [18].

- Model Validation: Evaluate model performance using cross-validation and hold-out test sets. Common metrics include Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC), precision, and recall.

Protocol 4: Building a Chemogenomic Neural Network with Deep Learning

- Data Representation:

- Molecules: Represent molecules as molecular graphs. Use a Graph Neural Network (GNN) to learn abstract, task-specific molecular representations from node (atom) and edge (bond) features [19].

- Proteins: Represent proteins by their amino acid sequences. Use a recurrent neural network (RNN) or convolutional neural network (CNN) to learn protein representations from the sequence.

- Model Architecture (Chemogenomic Neural Network):

- Encoders: Employ separate GNN and protein sequence encoders to generate numerical representations (embeddings) for each molecule and protein.

- Combiner: Combine the two embeddings, for example, by concatenation or element-wise multiplication.

- Predictor: Feed the combined representation into a feed-forward neural network (multi-layer perceptron) to output a probability of interaction [19].

- Training and Optimization: Train the end-to-end neural network using a binary cross-entropy loss function. For small datasets, employ transfer learning by pre-training the encoders on larger, related datasets (e.g., pre-training the GNN on a general chemical property prediction task) [19].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Different DTI Prediction Models on Benchmark Datasets

| Model Type | Model Name | Key Features | Reported AUC | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shallow Learning | kronSVM [19] | Kronecker product of drug and target kernels | >0.90 (dataset dependent) | Small to medium datasets |

| Shallow Learning | NRLMF [19] | Matrix factorization with regularization | Outperforms other shallow methods on various datasets [19] | Datasets with sparse interactions |

| Deep Learning | Chemogenomic Neural Network [19] | Learns representations from molecular graph and protein sequence | Competes with state-of-the-art on large datasets [19] | Large, high-quality datasets |

| Network-Based | drugCIPHER [22] | Integrates drug therapeutic/chemical similarity & PPI network | 0.935 (test set) [22] | Genome-wide target identification |

Network-Based and Genome-Wide Target Identification

Principle: This approach integrates pharmacological data (drug similarity) with genomic data (protein-protein interactions) to infer drug-target interactions on a genome-wide scale. It leverages the context that proteins targeted by similar drugs are often functionally related or located close to each other in a PPI network [22].

Protocol 5: Genome-Wide Target Prediction using drugCIPHER

- Construct Similarity Matrices:

- Drug Similarity: Calculate a drug-drug similarity matrix based on either therapeutic indications (phenotypic similarity) or chemical structure (2D fingerprints).

- Target Relevance: From a comprehensive PPI network (e.g., from BioGRID or STRING), calculate the network-based relevance between all pairs of protein targets.

- Model Building (drugCIPHER-MS): Build a linear regression model that relates the drug similarity matrix to the target relevance matrix. The integrated model (drugCIPHER-MS) combines both therapeutic and chemical similarity for enhanced predictive power [22].

- Prediction and Validation: Use the trained model to predict interaction profiles for novel drugs or new targets for existing drugs across the entire genome. The output is a ranked list of potential targets.

- Hypothesis Generation: Analyze the top predictions to identify unexpected drug-drug relations, suggesting potential novel therapeutic applications or side effects. These hypotheses require subsequent experimental validation [22].

Workflow for a General Chemogenomic Analysis

Case Study: Target Discovery for Schistosomiasis

Background: Schistosomiasis, a neglected tropical disease, relies almost exclusively on the drug praziquantel for treatment, creating an urgent need for new therapeutics. A target-based chemogenomics screen was employed to repurpose existing drugs for use against Schistosoma mansoni [17].

Application of Protocol:

- Target Compilation (Data Curation): A set of 2,114 S. mansoni proteins, including differentially expressed genes across life stages and targets from the TDR Targets database, was compiled [17].

- Homology Screening (Ligand/Structure-Based Principle): Each parasite protein was used as a query to search drug-target databases (TTD, DrugBank, STITCH) for human proteins with significant sequence homology (E-value ≤ 10⁻²⁰). The underlying assumption is that an approved drug active against the human target might also be active against the homologous schistosome protein [17].

- Refinement and Validation: Predicted drug-target interactions were refined by analyzing the conservation of functional regions and chemical space. The method successfully retrospectively predicted drugs known to be active against schistosomes, such as clonazepam and artesunate, validating the pipeline [17].

- Novel Predictions: The model identified 115 approved drugs not previously tested against schistosomes, such as aprindine and clotrimazole, providing a prioritized list for experimental assessment and potentially accelerating drug development for a neglected disease [17].

Drug Repurposing via Homology

Successful chemogenomic analysis relies on access to high-quality data and specialized computational tools. The following table details key resources.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Chemogenomic Target Discovery

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Target Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| DrugBank [17] [18] | Database | Comprehensive drug, target, and interaction data. | Source for known drug-target pairs for model training and validation. |

| ChEMBL [18] | Database | Bioactivity data for drug-like molecules. | Provides quantitative binding data for structure-activity relationship studies. |

| STITCH [17] [18] | Database | Chemical-protein interaction networks. | Integrates data for predicting both direct and indirect interactions. |

| Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) [17] | Database | Information on approved therapeutic proteins and drugs. | Curated resource for validated targets and drugs. |

| STRING/BioGRID [22] [23] | Database | Protein-protein interaction networks. | Provides genomic context for network-based methods like drugCIPHER. |

| EUbOPEN Chemogenomic Library [24] | Compound Library | A collection of well-annotated chemogenomic compounds. | Experimental tool for target deconvolution and phenotypic screening. |

| Cytoscape [25] [23] | Software | Network visualization and analysis. | Visualizes and analyzes complex drug-target-pathway networks. |

| PyTorch/TensorFlow | Software | Deep Learning Frameworks. | Enables building and training custom chemogenomic neural networks. |

| RDKit | Software | Cheminformatics Toolkit. | Calculates molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and handles chemical data. |

Concluding Remarks

The systematic exploration of chemical and biological spaces through in silico chemogenomics has fundamentally transformed the approach to novel target discovery. The protocols outlined herein—spanning ligand-based screening, proteochemometric modeling, deep learning, and network-based integration—provide a robust, multi-faceted toolkit for modern drug discovery scientists. The integration of diverse data types and powerful machine learning algorithms allows for the generation of high-confidence, testable hypotheses regarding new drug-target interactions, thereby de-risking and accelerating the early stages of drug development. As public and private initiatives like Target 2035 and EUbOPEN continue to expand the available open-access chemogenomic resources, these computational methods will become increasingly accurate and impactful, paving the way for the discovery of next-generation therapeutics [24].

The field of in silico chemogenomic drug design is undergoing a transformative shift, primarily propelled by two key drivers: the unprecedented expansion of publicly available bioactivity data and continuous advancements in computational power. These elements are foundational to modern computational methods, enabling the development of more accurate and predictive models for target identification, lead optimization, and drug repurposing. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols that leverage these drivers, framed within the context of a doctoral thesis on advanced chemogenomic research. The contained methodologies are designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to implement state-of-the-art computational workflows.

The volume of bioactivity data available for research has grown exponentially, creating a robust foundation for data-driven drug discovery. The following table summarizes key quantitative metrics of modern datasets.

Table 1: Key Metrics of Major Public Bioactivity Databases

| Database Name | Approximate Data Points | Unique Compounds | Protein Targets | Key Features and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papyrus [26] | ~60 million | ~1.27 million | ~6,900 | Aggregates ChEMBL, ExCAPE-DB, and other high-quality sources; includes multiple activity types (Ki, Kd, IC50, EC50). |

| ChEMBL30 [26] | ~19.3 million | ~2.16 million | ~14,855 | Manually curated bioactivity data from scientific literature. |

| ExCAPE-DB [26] | ~70.9 million | ~998,000 | ~1,667 | Large-scale compound profiling data. |

| BindingDB [4] | Data integrated into larger studies | Data integrated into larger studies | Data integrated into larger studies | Focuses on measured binding affinities. |

| Dataset from Yang et al. [4] | ~153,000 interactions | ~93,000 | 859 (Human) | Curated for human targets; used for ensemble chemogenomic model training. |

This vast data landscape enables the application of machine learning (ML) algorithms that require large datasets for training. The "Papyrus" dataset, for instance, standardizes and normalizes around 60 million data points from multiple sources, making it suitable for proteochemometric (PCM) modeling and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) studies [26]. The critical mass of data now available allows researchers to build models with significantly improved generalizability and predictive power for identifying drug-target interactions (DTIs).

Advanced Computational Methodologies in Chemogenomics

Concurrent with data growth, computational methodologies have evolved from single-target analysis to system-level, multi-scale approaches. The table below compares the primary computational paradigms in use today.

Table 2: Comparison of In Silico Drug Discovery Approaches

| Methodology | Key Principle | Data Requirements | Typical Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network-Based [27] [28] | Analyzes biological systems as interconnected networks (nodes and edges). | Protein-protein interactions, gene expression, metabolic pathways. | Target identification for complex diseases, drug repurposing, polypharmacology prediction. | Provides a system-wide view but requires complex data integration. |

| Ligand-Based [28] | "Similar compounds have similar properties." Compares chemical structures. | 2D/3D molecular descriptors, fingerprints of known active compounds. | Virtual screening, target fishing, hit expansion. | Limited by the chemical space of known actives; can be affected by activity cliffs. |

| Structure-Based [29] [28] | Uses 3D protein structures to predict ligand binding. | Protein crystal structures, homology models. | Molecular docking, de novo drug design, lead optimization. | Dependent on the availability and quality of protein structures. |

| Chemogenomic (PCM) [4] | Integrates both ligand and target descriptor information. | Bioactivity data paired with compound and protein descriptors. | Target prediction, profiling of off-target effects, virtual screening. | Leverages both chemical and biological information; can predict for targets with limited data. |

| Deep Learning (CPI) [30] | Uses complex neural networks to learn from raw or featurized data. | Very large datasets of compound-target interactions (millions of points). | Binding affinity prediction, activity cliff identification, uncertainty quantification. | High predictive performance but requires significant computational resources and data. |

Protocol: Developing an Ensemble Chemogenomic Model for Target Prediction

This protocol details the methodology for constructing a high-performance ensemble model for in-silico target prediction, as described by Yang et al. [4].

Objective

To build a computational model that predicts potential protein targets for a query small molecule by integrating multi-scale information from chemical structures and protein sequences.

Materials and Reagents

- Software & Libraries: Python programming environment (e.g., Anaconda), RDKit for chemical informatics, Scikit-learn for machine learning, DeepChem for deep learning workflows.

- Computing Resources: Multi-core CPU workstation or high-performance computing (HPC) cluster; GPU acceleration is recommended for deep learning components.

- Bioactivity Data: A curated dataset of compound-target interactions with associated binding affinity values (e.g., Ki ≤ 100 nM for positive labels). Example sources include ChEMBL and BindingDB [4].

- Protein Information: UniProt database for retrieving protein sequences and Gene Ontology (GO) terms.

Procedure

Data Curation and Preprocessing:

- Source Data: Collect compound-target interaction data from public databases like ChEMBL and BindingDB. Focus on human targets for relevant drug discovery applications.

- Labeling: Define a binding affinity threshold (e.g., Ki ≤ 100 nM) to create a binary classification dataset (positive interactions vs. negative/non-interactions).

- Data Cleaning: Remove duplicate entries and resolve conflicts where bioactivity values for the same compound-target pair differ by more than one order of magnitude.

Molecular and Protein Descriptor Calculation:

- Compound Representation: Generate multiple descriptor sets for each compound to capture different aspects of chemical structure.

- 2D Descriptors: Calculate 188 Mol2D descriptors encompassing constitutional, topological, and charge-related features [4].

- Molecular Fingerprints: Generate Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP4) to represent molecular substructures.

- Protein Representation: Generate multiple descriptor sets for each target protein.

- Sequence Descriptors: Compute composition- and transition-based descriptors from the amino acid sequence.

- Gene Ontology (GO) Terms: Annotate proteins with their GO terms related to Biological Process, Molecular Function, and Cellular Component to incorporate functional knowledge.

- Compound Representation: Generate multiple descriptor sets for each compound to capture different aspects of chemical structure.

Model Training and Ensemble Construction:

- Base Model Development: Train several individual machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, Neural Networks) using different combinations of the compound and protein descriptors.

- Model Validation: Evaluate the performance of each base model using stratified 10-fold cross-validation. Metrics should include AUC-ROC, precision, recall, and enrichment factors in top-k predictions.

- Ensemble Assembly: Select the top-performing base models and combine them into an ensemble model. This can be achieved through stacking or by averaging the prediction scores, which typically yields more robust and accurate predictions than any single model [4].

Target Prediction for a Novel Compound:

- For a query compound, calculate its full set of molecular descriptors.

- Create a set of compound-target pairs by combining the query compound's descriptors with the descriptors of all protein targets in the model's scope.

- Input all compound-target pairs into the trained ensemble model to obtain an interaction probability score for each pair.

- Rank the potential targets based on these scores. The top 1-10 targets with the highest scores are considered the most likely candidates for experimental validation [4].

Workflow Visualization: Ensemble Chemogenomic Modeling

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the ensemble chemogenomic modeling protocol.

Diagram 1: Ensemble chemogenomic modeling and prediction workflow.

The following table details key resources required for conducting in silico chemogenomic research, as featured in the protocols and literature.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for In Silico Chemogenomics

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevant Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Papyrus Dataset [26] | Curated Bioactivity Data | Provides a standardized, large-scale benchmark dataset for training and testing predictive models. | Used for baseline QSAR and PCM model development. |

| ChEMBL Database [27] [4] [26] | Bioactivity Database | A manually curated repository of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used for model training and validation. | Source of compound-target interaction data for building classification models. |

| UniProt Knowledgebase [4] | Protein Information Database | Provides comprehensive protein sequence and functional annotation data (e.g., Gene Ontology terms). | Used for calculating protein descriptors in chemogenomic models. |

| RDKit [4] [26] | Cheminformatics Library | Open-source toolkit for cheminformatics, including descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation, and molecular operations. | Used for standardizing compound structures and generating molecular descriptors. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [29] [26] | 3D Structure Database | Repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes. | Essential for structure-based drug design (SBDD) and homology modeling. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch) | Computational Library | Provide the foundation for building and training complex deep neural network models for CPI prediction. | Used to implement models like GGAP-CPI for robust bioactivity prediction [30]. |

| Homology Modeling Tools (e.g., MODELLER) | Computational Method | Predicts the 3D structure of a protein based on its sequence similarity to a template with a known structure. | Applied when experimental structures are unavailable for SBDD [29]. |

Core Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Drug Development

Computational chemogenomics represents a pivotal discipline in modern pharmacological research, aiming to systematically identify the interactions between small molecules and biological targets on a large scale [1]. Within this framework, ligand-based drug design provides powerful computational strategies for discovering novel bioactive compounds when the structural information of the target is limited or unavailable. These methods operate on the fundamental principle that molecules with similar structural or physicochemical characteristics are likely to exhibit similar biological activities [31]. The primary ligand-based techniques—Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR), pharmacophore modeling, and molecular similarity searching—enable researchers to extract critical information from known active compounds to guide the optimization of existing leads and the identification of new chemical entities. By abstracting key molecular interaction patterns, these approaches facilitate "scaffold hopping" to discover novel chemotypes with desired biological profiles, thereby expanding the explorable chemical space in drug discovery campaigns [32] [33].

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

Molecular Similarity Principle

The cornerstone of all ligand-based approaches is the molecular similarity principle, which posits that structurally similar molecules are more likely to have similar biological properties [31]. This concept enables virtual screening of large chemical libraries by comparing new compounds to known active molecules using various molecular descriptors. These descriptors range from one-dimensional physicochemical properties to two-dimensional structural fingerprints and three-dimensional molecular fields and shapes [32]. The effectiveness of similarity searching depends heavily on the choice of molecular representation and similarity metrics, with different approaches exhibiting varying performance across different chemical classes and target families [31].

Pharmacophore Theory

A pharmacophore is abstractly defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [34]. In practical terms, a pharmacophore model represents the essential chemical functionalities and their spatial arrangement required for biological activity. The most significant pharmacophoric features include [34]:

- Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA)

- Hydrogen bond donors (HBD)

- Hydrophobic areas (H)

- Positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI)

- Aromatic rings (AR)

Table 1: Core Pharmacophoric Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Chemical Groups | Role in Molecular Recognition |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | Carbonyl, ether, hydroxyl | Forms hydrogen bonds with donor groups on target |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | Amine, amide, hydroxyl | Donates hydrogen for bonding with acceptor groups |

| Hydrophobic | Alkyl, aryl rings | Participates in van der Waals interactions |

| Positively Ionizable | Primary, secondary, tertiary amines | Forms salt bridges with acidic groups |

| Negatively Ionizable | Carboxylic acid, tetrazole | Forms salt bridges with basic groups |

| Aromatic Ring | Phenyl, pyridine, heterocycles | Engages in π-π stacking and cation-π interactions |

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR)

Fundamental Principles and Methodology

QSAR modeling establishes mathematical relationships between the chemical structures of compounds and their biological activities, enabling the prediction of activities for untested compounds [33]. Traditional QSAR utilizes physicochemical descriptors such as hydrophobicity (logP), electronic properties (σ), and steric parameters (Es) to create linear regression models. Contemporary QSAR approaches employ more sophisticated machine learning algorithms and thousands of molecular descriptors derived from 2D and 3D molecular structures [33].

The standard QSAR workflow involves:

- Data Collection - compiling compounds with measured biological activities

- Descriptor Calculation - generating numerical representations of molecular structures

- Model Building - applying statistical or machine learning methods to relate descriptors to activity

- Model Validation - assessing predictive power using internal and external validation techniques

Advanced Protocol: 3D-QSAR with Pharmacophore Fields

3D-QSAR methods extend traditional QSAR by incorporating spatial molecular information. The following protocol outlines the process for developing a 3D-QSAR model using pharmacophore fields, based on the PHASE methodology [33]:

Step 1: Compound Selection and Preparation

- Select a diverse set of 20-50 compounds with measured biological activities spanning at least 3 orders of magnitude

- Generate biologically relevant conformational ensembles for each compound using tools like iConfGen with default settings and a maximum of 25 output conformations [33]

- Ensure consistent protonation states appropriate for physiological conditions

Step 2: Molecular Alignment

- Identify common pharmacophore features across the active compounds

- Perform systematic conformational analysis to determine the bioactive conformation

- Align molecules based on their pharmacophoric features using rigid or flexible alignment algorithms

Step 3: Pharmacophore Field Calculation

- Create a 3D grid around the aligned molecules

- Calculate pharmacophore interaction fields at each grid point, representing the potential for specific molecular interactions (H-bond donation, H-bond acceptance, hydrophobic interactions, etc.)

- Use a grid spacing of 1.0-2.0 Å for optimal resolution

Step 4: Model Development and Validation

- Apply Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to correlate pharmacophore fields with biological activity

- Use cross-validation (typically 5-fold) to determine the optimal number of components and avoid overfitting

- Validate the model using an external test set not used in model building

- Calculate statistical metrics including R², Q², and RMSE to evaluate model performance

Table 2: Statistical Benchmarks for Valid QSAR Models

| Statistical Parameter | Threshold Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| R² (Regression Coefficient) | >0.8 | Good explanatory power |

| Q² (Cross-Validation Correlation Coefficient) | >0.6 | Good internal predictive ability |

| RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) | As low as possible | Measurement of prediction error |

| F Value | >30 | High statistical significance |

Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling creates 3D pharmacophore hypotheses using only the structural information and physicochemical properties of known active ligands [34]. This approach is particularly valuable when the 3D structure of the target protein is unavailable. The methodology involves identifying common chemical features and their spatial arrangement conserved across multiple active compounds.

Protocol: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Model Development

Step 1: Data Set Curation

- Select 10-30 known active compounds with diverse structural scaffolds but similar mechanism of action

- Include 5-10 inactive or weakly active compounds to enhance model selectivity

- Ensure activities span a range of at least 2-3 orders of magnitude for quantitative models

Step 2: Conformational Analysis

- Generate comprehensive conformational ensembles for each compound

- Use energy window of 10-20 kcal/mol above the global minimum to ensure coverage of biologically relevant conformations

- Apply molecular dynamics or stochastic search methods for flexible molecules

Step 3: Common Feature Identification

- Perform systematic comparison of conformational ensembles across active compounds

- Identify pharmacophoric features consistently present in highly active compounds

- Determine optimal spatial tolerances (typically 1.5-2.5 Å) for each feature type

Step 4: Hypothesis Generation and Validation

- Generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses using algorithms like Hypogen [33]

- Score hypotheses based on their ability to discriminate between active and inactive compounds

- Validate models using test set compounds not included in model building

- Assess enrichment factors through decoy tests to evaluate virtual screening performance

Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPHAR)

The QPHAR methodology represents a novel approach to building quantitative activity models directly from pharmacophore representations [33]. This method offers advantages over traditional QSAR by abstracting molecular interactions and reducing bias toward overrepresented functional groups.

Protocol: QPHAR Model Implementation [33]

Step 1: Pharmacophore Alignment

- Generate a consensus pharmacophore (merged-pharmacophore) from all training samples

- Align individual pharmacophores to the merged-pharmacophore based on feature correspondence

Step 2: Feature-Position Encoding

- For each aligned pharmacophore, extract information regarding feature positions relative to the merged-pharmacophore

- Encode spatial relationships using appropriate descriptors capturing distances and orientations

Step 3: Model Training

- Apply machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, PLS) to establish quantitative relationships between pharmacophore features and biological activities

- Use default parameters for initial model building: maximum of 25 conformations per compound, 5-6 PLS components [33]

- For datasets with 15-20 training samples, employ strict cross-validation to ensure model robustness

Step 4: Model Application

- Use the trained model to predict activities of new pharmacophores

- In virtual screening, apply the model to rank pharmacophore models and prioritize those with predicted high activity

Molecular Similarity Searching

Molecular Descriptors and Similarity Metrics

Molecular similarity searching involves comparing chemical structures using various representation schemes to identify compounds similar to known active molecules [31]. The effectiveness of similarity searching depends on the appropriate choice of molecular descriptors and similarity coefficients.

Key Descriptor Categories:

- 2D Fingerprints: Binary vectors representing the presence or absence of structural patterns

- Circular Fingerprints: Capture radial environments around each atom (e.g., ECFP, FCFP series)

- Atom Environment Descriptors: Represent the chemical environment of each heavy atom at topological distances [35]

Similarity Metrics:

- Tanimoto Coefficient: Most widely used metric for fingerprint comparisons

- Cosine Similarity: Alternative metric less sensitive to fingerprint density

- Euclidean Distance: Geometric distance in descriptor space

Protocol: Similarity-Based Virtual Screening

Step 1: Reference Compound Selection

- Choose 1-3 known active compounds with desired activity profile and clean chemical structures

- Consider selecting multiple reference compounds to cover diverse active chemotypes

Step 2: Molecular Representation

- Generate appropriate molecular descriptors for reference compounds and database molecules

- For general screening, use circular fingerprints (ECFP4 or ECFP6) which have demonstrated superior performance in benchmark studies [31]

- For natural products or complex molecules, consider atom environment descriptors (e.g., MOLPRINT 2D) which have shown nearly 10% better retrieval rates in some studies [35]

Step 3: Similarity Calculation

- Compute similarity between each database compound and reference compound(s)

- Apply Tanimoto coefficient for fingerprint-based similarities

- For multiple reference compounds, use maximum similarity or average similarity approaches

Step 4: Result Analysis and Hit Selection

- Rank database compounds by decreasing similarity to reference compounds

- Apply additional filters (e.g., physicochemical properties, structural alerts) to remove undesirable compounds

- Select top-ranked compounds for experimental testing, considering both high-similarity compounds and diverse analogs with moderate similarity

Integrated Workflows and Advanced Applications

Combined Ligand-Based and Structure-Based Approaches

Integrating ligand-based and structure-based methods creates synergistic workflows that overcome the limitations of individual approaches [32]. Three primary integration schemes have been established:

1. Sequential Approaches Ligand-based methods provide initial filtering of large chemical libraries, followed by more computationally intensive structure-based methods on the reduced subset. This strategy optimizes the tradeoff between computational efficiency and accuracy [32].

2. Parallel Approaches Both ligand-based and structure-based methods are run independently, with results combined at the end. The consensus ranking from both methods typically shows increased performance and robustness over single-modality approaches [32].

3. Hybrid Approaches These integrate ligand and structure information simultaneously, such as using pharmacophore constraints in molecular docking or incorporating protein flexibility into similarity searching [32].

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for selecting ligand-based, structure-based, or integrated approaches in virtual screening.

Application in Natural Product Drug Discovery

Natural products present unique challenges for ligand-based methods due to their structural complexity, high molecular weight, and abundance of stereocenters [31]. Specialized approaches have been developed to address these challenges:

Protocol: Similarity Searching for Natural Products [31]

Step 1: Specialized Molecular Representation

- For modular natural products (nonribosomal peptides, polyketides), use biosynthetically-informed descriptors such as those implemented in GRAPE/GARLIC algorithms

- These methods perform in silico retrobiosynthesis and comparative analysis of resulting biosynthetic information

- For general natural product screening, apply circular fingerprints with larger radii (ECFP6) to capture complex structural environments

Step 2: Similarity Assessment

- Leverage the Tanimoto coefficient for standard fingerprint comparisons

- For biosynthetically-informed descriptors, use specialized similarity metrics based on biosynthetic alignment

- Account for macrocyclization patterns and post-assembly tailoring reactions in similarity calculations

Step 3: Result Interpretation

- Prioritize compounds with similar biosynthetic origins when using retrobiosynthetic approaches

- Consider both structural similarity and biosynthetic logic in hit selection

- Apply stricter similarity thresholds for complex natural products due to their structural complexity

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Ligand-Based Drug Design

| Tool Name | Application Area | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHASE | 3D-QSAR, Pharmacophore Modeling | Pharmacophore field calculation, PLS regression | Commercial (Schrödinger) |

| Catalyst/Hypogen | Pharmacophore Modeling | Quantitative pharmacophore modeling, exclusion volumes | Commercial (BioVia) |

| LEMONS | Natural Product Analysis | Enumeration of modular natural product structures | Open Source |

| QPHAR | Quantitative Pharmacophore Modeling | Direct pharmacophore-based QSAR, machine learning | Methodology [33] |

| MOLPRINT 2D | Similarity Searching | Atom environment descriptors, Bayesian classification | Algorithm [35] |

| LigandScout | Pharmacophore Modeling | Structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophores | Commercial |

| ChEMBL | Data Source | Curated bioactive molecules with target annotations | Public Database |

| RCSB PDB | Data Source | Experimental protein structures with bound ligands | Public Database |

Concluding Remarks

Ligand-based approaches remain indispensable tools in the chemogenomics toolkit, providing efficient and effective methods for hit identification and lead optimization when structural information on biological targets is limited. The continuing evolution of these methods—particularly through integration with structure-based approaches and adaptation to challenging chemical spaces like natural products—ensures their ongoing relevance in modern drug discovery. As chemical and biological data resources continue to expand, and machine learning algorithms become increasingly sophisticated, ligand-based methods will continue to play a crucial role in systematic drug discovery efforts aimed at comprehensively exploring chemical-biological activity relationships.