Harnessing Directed Evolution and Whole-Genome Sequencing to Decode Antimicrobial Resistance

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the synergistic application of directed evolution and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) to identify and characterize antimicrobial resistance...

Harnessing Directed Evolution and Whole-Genome Sequencing to Decode Antimicrobial Resistance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the synergistic application of directed evolution and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) to identify and characterize antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes. It covers the foundational principles of mimicking natural evolution in the lab and leveraging high-throughput sequencing technologies. The scope extends to detailed methodological pipelines, from library generation and in vivo mutagenesis to bioinformatic analysis using tools like CARD and ResFinder. It further addresses troubleshooting for experimental and computational challenges and offers a comparative analysis against traditional phenotypic methods. The goal is to equip professionals with the knowledge to accelerate the discovery of resistance mechanisms and inform the development of novel therapeutics.

The Evolutionary Engine: Principles of Directed Evolution and WGS for AMR Discovery

Directed evolution is a powerful protein engineering method that mimics the process of natural selection in a laboratory setting to steer proteins or nucleic acids toward user-defined goals [1]. This approach harnesses natural evolutionary principles but operates on a much shorter timescale, enabling the rapid selection of biomolecule variants with properties that make them more suitable for specific applications [2]. Since the first in vitro evolution experiments performed by Sol Spiegelman in 1967, a wide range of techniques have been developed to tackle the two main steps of directed evolution: genetic diversification (library generation) and isolation of variants of interest [2] [1]. The development of directed evolution methods was recognized with the awarding of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Frances Arnold for the evolution of enzymes, and to George Smith and Gregory Winter for phage display [1].

Directed evolution functions through iterative rounds of mutagenesis (creating a library of variants), selection (expressing those variants and isolating members with the desired function), and amplification (generating a template for the next round) [1]. This process can be performed in vivo (in living organisms) or in vitro (in cells or free in solution) [1]. The fundamental requirement for evolution—variation between replicators, fitness differences upon which selection acts, and heritable variation—is maintained throughout these iterative cycles [1]. The likelihood of success in a directed evolution experiment is directly related to the total library size, as evaluating more mutants increases the chances of finding one with the desired properties [1].

Core Principles and Methodologies

The Directed Evolution Workflow

The directed evolution cycle consists of three fundamental steps that are repeated iteratively: diversification, selection, and amplification. This systematic approach enables researchers to navigate vast sequence spaces efficiently to identify variants with improved or novel functions.

Library Creation Methods

The first step in directed evolution involves creating genetic diversity through various mutagenesis techniques. The choice of method depends on the specific engineering goals, available structural information, and desired library size.

Table 1: Common Genetic Diversification Methods in Directed Evolution

| Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-prone PCR | Random point mutations via low-fidelity PCR | Easy to perform; no prior knowledge needed | Reduced sampling of mutagenesis space; mutagenesis bias | Subtilisin E, Glycolyl-CoA carboxylase [2] |

| DNA Shuffling | Random sequence recombination of parental genes | Recombination advantages; accesses new combinations | High homology between parental sequences required | Thymidine kinase, Non-canonical esterase [2] |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | Focused mutagenesis of specific positions | In-depth exploration of chosen positions; smart libraries reduce size | Libraries can become very large; only a few positions mutated | Widely applied to enzyme evolution [2] |

| RAISE | Insertion of random short insertions and deletions | Enables random indels across sequence | Introduces frameshifts | β-Lactamase evolution [2] |

| Gene Shuffling | Fragmentation and recombination of related sequences | Combines beneficial mutations from different parents | Requires multiple parent sequences | Antibody engineering [3] |

Selection and Screening Strategies

After generating variant libraries, the critical challenge lies in identifying the rare improved variants from the vast majority of neutral or deleterious mutations. The selection strategy is typically determined by the availability of high-throughput assays and the specific property being engineered.

Table 2: Selection and Screening Methods in Directed Evolution

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Display Techniques (Phage, Yeast) | Physical linkage of genotype to phenotype | Very High (10^7-10^11) | Extremely high throughput; direct selection | Limited to binding properties; not ideal for enzymes [2] [1] |

| FACS-based Methods | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting | High (10^7-10^9) | Very high throughput; quantitative | Requires fluorescence coupling [2] [4] |

| Colorimetric/Fluorimetric Assays | Colony-based screening with chromogenic substrates | Medium (10^3-10^6) | Simple, inexpensive; direct activity measurement | Limited to specific spectral properties [2] |

| In vivo Selection | Coupling desired function to cell survival | Ultra High (Limited by transformation efficiency) | Extremely high throughput; minimal equipment | Difficult to engineer; prone to artifacts [1] |

| MS-based Methods | Mass spectrometry for product detection | Medium (10^3-10^4) | Does not rely on specific substrate properties | Requires specialized equipment [2] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Error-Prone PCR for Random Mutagenesis

Purpose: To introduce random point mutations throughout a target gene sequence for creating diverse variant libraries.

Materials:

- Target DNA template (10-100 ng)

- Taq DNA polymerase or other low-fidelity polymerase

- dNTP mixture (standard concentration)

- PCR primers specific to target gene

- MgCl₂ (additional may be required)

- MnCl₂ (optional, to increase error rate)

Procedure:

- Prepare Reaction Mix:

- Combine in a PCR tube: 10-100 ng DNA template, 1× PCR buffer, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 0.5 μM each primer, 5-7 mM MgCl₂, 0.1-0.5 mM MnCl₂ (optional), and 2.5 U Taq polymerase.

- Adjust total volume to 50 μL with nuclease-free water.

PCR Amplification:

- Initial denaturation: 94°C for 3 minutes

- 25-30 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 45-65°C (primer-specific) for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb of template

- Final extension: 72°C for 7 minutes

Purification and Cloning:

- Purify PCR product using standard methods

- Clone into appropriate expression vector

- Transform into competent cells for library generation

Notes: Error rate can be modulated by adjusting Mg²⁺ concentration, adding Mn²⁺, using unequal dNTP concentrations, or increasing template concentration [3]. The mutation rate should be optimized to typically 1-5 amino acid substitutions per gene.

Protocol 2: Phage Display for Binding Selection

Purpose: To select protein variants (e.g., antibodies, peptides) with enhanced binding properties from large libraries.

Materials:

- Phage display library (10^9-10^11 diversity)

- Target antigen for selection

- Immunotubes or microtiter plates

- Washing buffers (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20)

- Elution buffer (0.1 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.2)

- Neutralization buffer (1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.0)

- E. coli host strain for phage amplification

Procedure:

- Panning Round:

- Coat immunotube with 10-100 μg/mL target antigen in PBS overnight at 4°C

- Block with 2% milk-PBS for 2 hours at room temperature

- Add phage library (10^11-10^12 phage) in 2% milk-PBS, incubate 1-2 hours with rotation

- Wash 10-20 times with PBS-0.1% Tween-20, then with PBS alone

Elution and Amplification:

- Elute bound phage with 1 mL glycine buffer (10 minutes, room temperature)

- Neutralize with 0.5 mL Tris buffer

- Infect log-phase E. coli with eluted phage for amplification

- Precipitate amplified phage with PEG/NaCl for next panning round

Iterative Selection:

- Repeat panning for 3-5 rounds with increasing stringency

- After final round, plate infected bacteria for individual clone analysis

- Screen individual clones for binding specificity and affinity

Notes: Selection stringency can be increased by reducing antigen concentration, increasing wash number, or adding competitors in later rounds [1]. The diversity of the output library should be monitored to avoid selection of overly dominant clones.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful directed evolution campaigns require specialized reagents and tools for creating diversity, expressing variants, and measuring improved functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Directed Evolution

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taq Polymerase | Low-fidelity PCR for random mutagenesis | Error-prone PCR for library generation | Naturally lower fidelity than high-fidelity polymerases [3] |

| NNK Degenerate Primers | Saturation mutagenesis of specific codons | Targeted diversification of active sites | NNK codons encode all 20 amino acids with only one stop codon [5] |

| Yeast Display System | Surface display for eukaryotic protein expression | Antibody engineering, protein stability | Allows for eukaryotic post-translational modifications [3] |

| Phage Display Vectors | Surface display on bacteriophage | Peptide and antibody selection | High diversity libraries (10^9-10^11 variants) [1] |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | High-throughput screening based on fluorescence | Enzyme engineering with coupled assays | Can screen >10^7 variants per hour [2] [4] |

| Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) | Reference database for resistance genes | Analysis of evolved antibiotic resistance | Uses Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) for prediction [6] |

Integration with Whole-Genome Sequencing for Resistance Gene Identification

The integration of directed evolution with whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has created powerful synergies for understanding and engineering resistance mechanisms. WGS enables comprehensive analysis of evolved variants, moving beyond single-gene studies to organism-level resistance profiling.

Directed evolution experiments have demonstrated that resistance to extended-spectrum β-lactams in Gram-negative bacteria can be accurately predicted from WGS data. In one study, WGS predictions showed sensitivity of 0.87, specificity of 0.98, positive predictive value of 0.97, and negative predictive value of 0.91 for identifying resistance to β-lactams used in treating neutropenic fever [7]. This approach successfully identified 133 putative instances of resistance, 65% of which would not have been detected by typical PCR-based methods targeting only β-lactamase genes [7].

Bioinformatics tools and databases play a crucial role in analyzing WGS data for resistance gene identification:

- CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database): A rigorously curated resource using the Antibiotic Resistance Ontology (ARO) for classification [6]

- ResFinder/PointFinder: Specialized tools for identifying acquired AMR genes and chromosomal point mutations [6]

- DeepARG: Machine learning-based tool for identifying novel or low-abundance ARGs [6]

Benchmarking datasets have been developed to standardize AMR gene detection from WGS data, containing 174 bacterial genomes representing 22 species with curated resistance profiles [8]. These resources enable robust comparison of different computational approaches for resistance gene identification.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Machine Learning-Enhanced Directed Evolution

Recent advances have integrated machine learning with directed evolution to overcome limitations of traditional approaches. Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) represents a cutting-edge development that uses uncertainty quantification to explore protein sequence space more efficiently [5].

In the ALDE workflow:

- A combinatorial design space on k residues is defined (20^k possible variants)

- Initial sequence-fitness data is collected through wet-lab screening

- Machine learning models predict fitness across sequence space

- Acquisition functions balance exploration and exploitation to select next variants

- Iterative cycles continue until fitness is optimized [5]

This approach has demonstrated remarkable efficiency in challenging engineering landscapes. In one application, ALDE optimized five epistatic residues in a protoglobin active site for a non-native cyclopropanation reaction, improving yield from 12% to 93% in just three rounds while exploring only ~0.01% of the design space [5].

High-Throughput Measurement Technologies

The effectiveness of directed evolution campaigns increasingly depends on high-throughput measurement (HTM) technologies that can quantitatively characterize genotype-phenotype relationships. Recent innovations include:

- Sort-seq: Combining fluorescence-activated cell sorting with deep sequencing [4]

- Deep mutational scanning: Comprehensive assessment of mutation effects [4]

- Repurposed sequencing flow cells: For in vitro characterization of binding kinetics [4]

These approaches enable quantitative characterization of up to 10^6 protein variants, providing rich datasets that fuel machine learning predictions and expand engineering capabilities [4]. The integration of HTMs with laboratory automation through biofoundries further accelerates the design-build-test-learn cycle in directed evolution [4].

Directed evolution has matured from a specialized protein engineering technique to a robust methodology that mimics natural selection in laboratory settings. The integration of whole-genome sequencing provides comprehensive analysis of evolved variants, while machine learning approaches like ALDE offer promising directions for navigating complex fitness landscapes more efficiently. As high-throughput measurement technologies continue to advance, directed evolution will remain an essential tool for engineering biological systems with precise specifications, from therapeutic antibodies to environmentally-friendly biocatalysts. The continued development of standardized protocols, benchmarking datasets, and computational resources will further enhance the reproducibility and impact of directed evolution across basic research and applied biotechnology.

The evolution of DNA sequencing technologies, from the Sanger chain-termination method to modern massively parallel next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms, has fundamentally transformed biological research and clinical applications. This technological shift has been particularly impactful in the field of directed evolution and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) research, enabling comprehensive analysis of entire genomes with unprecedented speed and resolution. Where Sanger sequencing once provided a reliable but narrow snapshot of genetic information, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) now offers researchers a powerful tool to observe genetic changes across entire organisms, track the emergence of resistance mechanisms, and engineer improved biomolecules through directed evolution approaches.

The transition between these sequencing eras represents more than just incremental improvement—it constitutes a paradigm shift in experimental capabilities. While Sanger sequencing remains suitable for interrogating single genes or small genomic regions, NGS technologies empower scientists to sequence hundreds to thousands of genes simultaneously, providing the comprehensive genetic landscape necessary for identifying novel resistance genes, understanding complex evolutionary pathways, and accelerating drug discovery pipelines [9] [10].

Technological Evolution: From Sanger to Next-Generation Sequencing

Fundamental Principles and Historical Context

First developed in 1977 by Frederick Sanger and colleagues, the chain-termination method formed the foundation of DNA sequencing for decades [10]. This technique relies on DNA polymerase to synthesize complementary strands to a single-stranded DNA template, with the incorporation of fluorescently-labeled dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) randomly terminating strand elongation. The resulting fragments are separated by capillary electrophoresis, generating a sequence readout based on their terminal ddNTPs [9]. Automated Sanger sequencing significantly advanced the field, enabling milestone projects like the first complete bacterial genome sequencing of Haemophilus influenzae in 1995, which required substantial time and resources [10].

The critical distinction of NGS technologies lies in their massively parallel sequencing approach. While Sanger sequencing processes a single DNA fragment per run, NGS simultaneously sequences millions of fragments, dramatically increasing throughput and reducing costs [9]. This parallelization enables researchers to sequence entire genomes in hours rather than years, at a fraction of the previous cost [10]. The underlying biochemistry varies across NGS platforms, with Illumina employing sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible dye terminators, Pacific Biosciences utilizing single-molecule real-time sequencing, and Oxford Nanopore relying on electronic signal detection as DNA passes through protein nanopores [10] [11].

Comparative Analysis of Sequencing Technologies

Table 1: Key Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics of Sequencing Platforms

| Technology/Platform | Read Length | Time per Run | Output per Run | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing | 500-1,000 bp | ~7 hours | 0.44 Mbp | Validation of genetic variants, small-target sequencing [10] |

| Illumina (Short-read) | 56-300 bp | 56 hours - 14 days | 15-600 Gbp | Whole-genome sequencing, transcriptomics, targeted sequencing [9] [10] |

| Ion Torrent | 200-400 bp | ~4 hours | 200 Mbp - 2.5 Gbp | Microbial sequencing, targeted panels [10] |

| Pacific Biosciences (Long-read) | 10->50 kb | 0.5-4 hours | 0.5-1 Gbp | De novo assembly, complex genomic regions [10] |

| Oxford Nanopore (Long-read) | 0.5->50 kb | 0.5-2 hours | 15-30 Gbp | Real-time sequencing, metagenomics, field sequencing [10] [11] |

Table 2: Advantages and Limitations of Sequencing Approaches for Directed Evolution and AMR Research

| Sequencing Method | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing | • High accuracy for single targets• Established, familiar workflow• Cost-effective for 1-20 targets | • Low throughput• Limited discovery power• Sensitivity ~15-20% [9] | • Validation of NGS findings• Confirming specific mutations• Small-scale projects |

| Short-read NGS (Illumina, Ion Torrent) | • High sequencing depth/sensitivity• Cost-effective for large target numbers• Detection of low-frequency variants (down to 1%)• High accuracy [9] [10] | • Limited read length challenges assembly• Difficulties with repetitive regions• GC bias [10] | • Variant detection across many samples• Resistance gene identification• Microbial genomics |

| Long-read NGS (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) | • Resolves complex genomic regions• Epigenetic modification detection• Real-time sequencing (Nanopore)• Improved de novo assembly [10] [11] | • Higher error rates (mitigated by consensus)• Higher DNA input requirements• Lower throughput than short-read [11] | • Complete genome assembly• Structural variant detection• Hybrid sequencing approaches |

The dramatic reduction in sequencing costs has been a pivotal driver of WGS adoption. The cost per million bases of DNA sequence has dropped from over $5,000 in 2001 to approximately $0.006 in 2022, while the cost to sequence an entire human genome has fallen from over $95 million to about $525 during the same period [10]. This cost reduction has made large-scale genomic studies feasible and enabled researchers to design more ambitious directed evolution experiments with comprehensive sequencing at multiple time points.

Whole-Genome Sequencing for Resistance Gene Identification

Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance

Antimicrobial resistance arises through diverse molecular mechanisms that WGS can comprehensively detect. These include: (1) point mutations in genes encoding drug targets (e.g., gyrA mutations conferring fluoroquinolone resistance); (2) acquired resistance genes encoding enzymes that inactivate antibiotics (e.g., β-lactamases); (3) target modification or bypass mechanisms; (4) changes in membrane permeability; and (5) efflux pump overexpression [6] [12]. WGS provides the resolution to identify all these mechanisms in a single assay, from single nucleotide variants to large structural rearrangements and horizontal gene transfer events.

The power of WGS extends beyond merely cataloging known resistance determinants. By providing a complete view of the bacterial genome, researchers can discover novel resistance mechanisms and understand the complex genetic networks that regulate resistance expression. This comprehensive approach is particularly valuable for tracking the mobilization of resistance genes through plasmids, integrons, and transposons, which drive the dissemination of AMR across bacterial populations [13] [6].

Bioinformatics Approaches for Resistance Gene Detection

Table 3: Key Bioinformatics Resources for Antibiotic Resistance Gene Identification

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARD [6] | Manually curated database | Comprehensive AMR detection | • Antibiotic Resistance Ontology (ARO)• Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) tool• CARD*Shark curation algorithm | • Requires experimental validation• Manual curation delays updates |

| ResFinder/PointFinder [6] [12] | Specialized detection tool | Identifies acquired AMR genes and chromosomal mutations | • K-mer-based alignment for rapid analysis• Integrated platform for genes and mutations• Phenotype prediction tables | • Focuses on known determinants• Limited novel gene discovery |

| DeepARG [6] | Machine learning tool | Predicts novel and low-abundance ARGs | • Deep learning model trained on known ARGs• Identifies distant ARG homologs• Suitable for metagenomic data | • Computational resource-intensive• Potential false positives |

| ARGMiner [6] | Consolidated database | Integrates multiple ARG resources | • Broad coverage from multiple sources• Text mining for literature curation• Regular updates | • Potential redundancy• Variable curation standards |

| MEGARes [6] | Manually curated database | AMR reference for metagenomics | • Hierarchical structure for precision• Comprehensive resistance mechanism coverage• Compatible with various analysis tools | • Focused on acquired resistance genes• Limited chromosomal mutation data |

Bioinformatics pipelines for resistance gene identification typically follow two main approaches: assembly-based methods, which reconstruct complete genomes or large contigs before ARG identification, and read-based methods, which identify ARGs directly from sequencing reads [6]. Assembly-based approaches generally offer higher accuracy, especially for complex or low-abundance resistance determinants, while read-based methods are faster and suitable for rapid screening. The selection of appropriate bioinformatics tools and databases depends on the research objectives, with considerations for database curation standards, annotation depth, and coverage of relevant resistance mechanisms [6].

Experimental Protocol: WGS for Antimicrobial Resistance Profiling

Protocol: Whole-Genome Sequencing and Analysis of Bacterial Isolates for Antibiotic Resistance Gene Identification

I. DNA Extraction and Quality Control

- Extract genomic DNA using validated kits (e.g., DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit, Qiagen; Maxwell RSC Cell DNA purification kit, Promega) [12].

- Assess DNA concentration using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit Fluorometer) and purity via spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8-2.0).

- Verify DNA integrity by agarose gel electrophoresis, ensuring high molecular weight bands without degradation.

II. Library Preparation and Sequencing

- For Illumina platforms: Fragment 500 ng genomic DNA to ~550 bp insert size using enzymatic (e.g., NEBNext Ultra II FS module) or mechanical shearing [12].

- Prepare sequencing libraries using kits such as KAPA HyperPlus (Roche) with platform-specific adapters.

- For NovaSeq 6000: Perform size selection with Pippin Prep (Sage Science) using CDF1510 1.5% agarose dye-free cassette [12].

- Quantify libraries by qPCR and pool equimolarly. Include 1% PhiX control library to enhance sequence diversity.

- Sequence on Illumina platforms (MiSeq, NextSeq, or NovaSeq 6000) using appropriate reagent kits (e.g., v2/v3 for MiSeq, SP for NovaSeq) to generate 2×250 bp or 2×300 bp paired-end reads [12].

III. Bioinformatic Analysis

- Assess raw read quality with FastQC (v0.11.4+) and perform adapter trimming and quality filtering with Trimmomatic or Cutadapt.

- Perform de novo assembly using SPAdes genome assembler with appropriate k-mer sizes [12].

- Assess assembly quality using QUAST, evaluating contiguity (N50), completeness, and potential contamination.

- Annotate resistance genes using a combination of tools:

- Determine sequence types (STs) using MLST schemes appropriate for the bacterial species (e.g., Achtman scheme for E. coli) [12].

IV. Validation and Phenotypic Correlation

- Compare genotypic predictions with phenotypic susceptibility testing using broth microdilution according to EUCAST standards [12].

- Calculate categorical agreement, major errors (resistant genotype/susceptible phenotype), and very major errors (susceptible genotype/resistant phenotype).

- Resolve discrepancies by manual inspection of sequencing coverage, assembly quality, and potential novel resistance mechanisms.

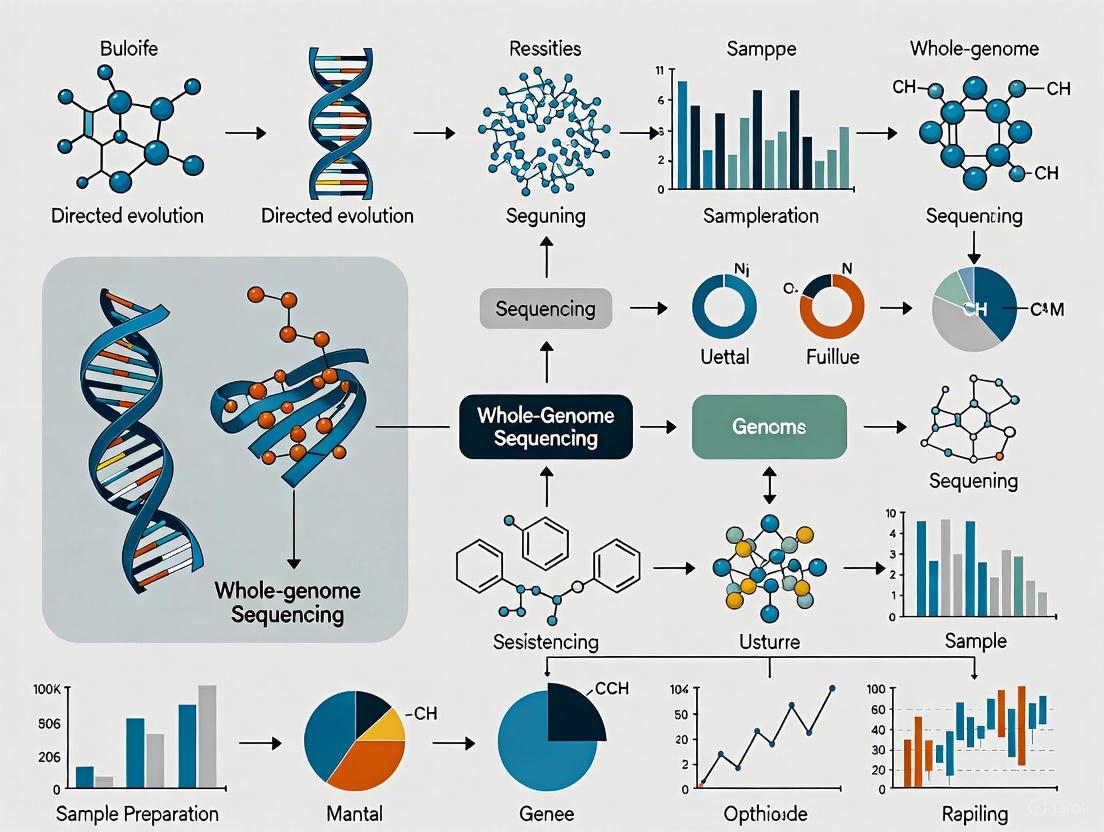

Figure 1: Comprehensive Workflow for Whole-Genome Sequencing and Analysis of Antibiotic Resistance Genes

Directed Evolution and Whole-Genome Sequencing

Directed Evolution Methodology

Directed evolution mimics natural selection in laboratory settings to engineer biomolecules with improved or novel functions. This powerful approach has become indispensable for developing enzymes with enhanced stability, activity, and specificity for industrial and therapeutic applications [2]. The process involves two fundamental steps: (1) generating genetic diversity in a target gene to create variant libraries, and (2) screening or selecting for variants with desired properties [2] [14].

Key techniques for generating genetic diversity include:

- Error-prone PCR: Randomly introduces point mutations throughout the target sequence through imperfect PCR conditions [2].

- DNA shuffling: Recombines sequences from related genes to create chimeric variants with beneficial mutations [2].

- Site-saturation mutagenesis: Systematically targets specific residues to explore all possible amino acid substitutions [2].

- RAISE (Random Insertion/Deletion Strategy): Creates random short insertions and deletions to explore more diverse sequence space [2].

- Orthogonal replication systems: Utilizes specialized DNA polymerases with inherent mutagenic properties for in vivo continuous evolution [2].

Following library generation, high-throughput screening methods identify improved variants. These include fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for binding or enzymatic activity, microplate-based assays, and display technologies such as phage display that physically link genotype to phenotype [2].

Integration of WGS in Directed Evolution Workflows

Whole-genome sequencing has become an invaluable tool in directed evolution campaigns, enabling researchers to move beyond simply identifying improved variants to understanding the genetic basis of those improvements. By sequencing populations throughout the evolution process, researchers can:

- Track the trajectory of beneficial mutations across generations

- Identify synergistic mutations that contribute to improved function

- Detect compensatory mutations that alleviate fitness costs

- Uncover mutational hotspots that tolerate or benefit from variation

- Guide subsequent library design based on empirical mutation data

In pharmaceutical applications, directed evolution coupled with WGS has enabled engineering of enzymes for improved drug synthesis, therapeutic proteins with enhanced pharmacokinetics, and antibodies with increased affinity and specificity [14]. The combination of these approaches accelerates the development of biocatalysts for industrial processes and biotherapeutics for clinical use.

Experimental Protocol: Directed Evolution with WGS Analysis

Protocol: Directed Evolution of Enzymes with Whole-Genome Sequencing Analysis

I. Library Generation through Mutagenesis

- For error-prone PCR: Use mutagenic conditions (e.g., unbalanced dNTP concentrations, Mn2+ supplementation, error-prone polymerases) to achieve 1-10 mutations per gene [2].

- For DNA shuffling: Fragment related genes with DNase I, reassemble through primerless PCR, then amplify full-length chimeras with flanking primers [2].

- For site-saturation mutagenesis: Design primers containing NNK degeneracy at target codons to cover all 20 amino acids, then amplify using high-fidelity polymerase [2].

- Clone variant libraries into appropriate expression vectors using Gibson assembly or restriction enzyme-based methods.

II. High-Throughput Screening/Selection

- Transform library into expression host (e.g., E. coli, yeast) to achieve >10x library coverage.

- For enzymatic activity: Implement fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with fluorogenic substrates or product entrapment strategies [2].

- For binding affinity: Utilize display technologies (phage, yeast, or ribosome display) with iterative rounds of panning/selection [2].

- For antibiotic resistance: Plate transformed cells on gradient antibiotic plates to select for enhanced resistance determinants [2].

- Isolate top-performing variants for further analysis and sequencing.

III. Whole-Genome Sequencing of Evolved Variants

- Prepare sequencing libraries from selected variants using kits such as KAPA HyperPrep or Nextera XT.

- For population dynamics analysis, include barcodes to multiplex multiple variants in a single sequencing run [11].

- Sequence on appropriate platform: Illumina for high accuracy, PacBio for complete gene assembly, or Nanopore for real-time monitoring.

- Ensure sufficient coverage (>50x for clonal isolates, >100x for population sequencing).

IV. Bioinformatics Analysis of Evolved Sequences

- Map sequencing reads to parental sequence using BWA or Bowtie2.

- Call variants with GATK or LoFreq, applying appropriate quality filters.

- Identify consensus mutations in improved variants and examine mutation frequencies across populations.

- For structural context, map mutations to protein structures using PyMOL or ChimeraX.

- Design next-generation libraries focusing on beneficial mutation combinations.

Figure 2: Directed Evolution Workflow Integrated with Whole-Genome Sequencing Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Whole-Genome Sequencing and Directed Evolution

| Product Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen), Maxwell RSC Cell DNA Purification Kit (Promega) | High-quality genomic DNA isolation from bacterial cultures | • Removal of inhibitors• High molecular weight DNA• Reproducible yields [12] |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | KAPA HyperPrep Kit (Roche), NEBNext Ultra II FS Module | Fragment DNA and add sequencing adapters | • Efficient library construction• Low bias• Compatible with automation [12] [14] |

| Target Enrichment | KAPA HyperCapture, Illumina Nextera Flex | Enrich specific genomic regions of interest | • Customizable target panels• Uniform coverage• High on-target rates |

| High-Fidelity Polymerases | KAPA HiFi DNA Polymerase (Roche) | Accurate amplification for library construction | • Engineered via directed evolution• Ultra-high fidelity• Robust performance [14] |

| Mutagenesis Kits | GeneMorph II Random Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent), commercial site-directed mutagenesis kits | Introduce genetic diversity for directed evolution | • Controllable mutation rates• Even mutation distribution• High efficiency [2] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CARD RGI, ResFinder, DeepARG, SPAdes | Analyze sequencing data and identify resistance genes | • Curated databases• User-friendly interfaces• Regular updates [6] [12] |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The integration of WGS into drug discovery pipelines has revolutionized multiple aspects of pharmaceutical development, from target identification to companion diagnostic development. In antimicrobial drug discovery, WGS enables comprehensive resistance profiling of clinical isolates, identification of novel resistance mechanisms, and tracking of resistance transmission in healthcare settings [10] [12]. This information guides the development of new antibiotics that circumvent existing resistance mechanisms and informs stewardship programs to preserve antibiotic efficacy.

In oncology, WGS facilitates comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors, identifying driver mutations, resistance mechanisms, and biomarkers for targeted therapy [15]. The ability to sequence circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) provides a non-invasive method for monitoring treatment response and detecting emergent resistance mutations during therapy [15]. For rare diseases, WGS can identify previously unknown genetic determinants, enabling development of targeted therapies for patient populations with specific genetic profiles [16].

The pharmaceutical industry increasingly utilizes WGS across the entire drug development pipeline:

- Target identification: Uncovering novel therapeutic targets through association of genetic variants with disease states [15]

- Preclinical development: Validating targets in disease models and assessing potential resistance mechanisms [15]

- Clinical trials: Stratifying patients based on genetic biomarkers and monitoring molecular responses [15] [16]

- Post-market surveillance: Tracking resistance development and understanding variable treatment responses [13]

The journey from Sanger sequencing to modern NGS platforms has unleashed transformative potential in biological research and therapeutic development. The power of whole-genome sequencing lies not only in its comprehensive scope but also in its integration with sophisticated bioinformatics tools and experimental approaches like directed evolution. For researchers focused on antimicrobial resistance, WGS provides an unparalleled tool for deciphering resistance mechanisms, tracking transmission pathways, and guiding the development of countermeasures against resistant pathogens.

As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, with improvements in read length, accuracy, and accessibility, their applications in drug discovery and resistance research will expand correspondingly. The convergence of WGS with directed evolution creates a powerful synergy—where sequencing reveals nature's solutions to chemical challenges, and directed evolution optimizes those solutions for human benefit. This integrated approach promises to accelerate the development of novel therapeutics and diagnostic tools, ultimately enhancing our ability to combat antimicrobial resistance and address unmet medical needs across diverse disease areas.

A central challenge in modern therapeutic development is the predictable and rapid emergence of drug resistance. Traditional laboratory evolution methods explore only a fraction of possible genetic sequences, often failing to identify rare resistance mutations and combinations thereof [17]. This application note details how the integration of directed evolution with whole-genome sequencing creates a powerful framework for definitively linking genetic diversity to resistance phenotypes. By moving beyond observational studies to actively generating and mapping genetic variation, researchers can systematically identify resistance mechanisms and predict their evolution, ultimately informing the development of more durable treatments. This document provides a detailed protocol for implementing Directed Evolution with Random Genomic Mutations (DIvERGE) and its application in both microbial and human cell systems.

Key Concepts and Quantitative Foundations

Resistance arises through two primary evolutionary pathways, each with distinct implications for drug development and monitoring.

- Genes-First Pathway: This classical model posits that a new gene mutation appears first and provides a reproductive advantage, leading to its spread in the population. This pathway is often driven by single-point mutations in the drug target [18].

- Phenotypes-First Pathway: An alternative model suggests that genetically identical cells can fluctuate between different, non-heritable cell states due to phenotypic plasticity. These transient states can later become stabilized by subsequent genetic or epigenetic changes, accelerating adaptation to therapeutic pressures [18].

The following table summarizes the core differences between these pathways, which can coexist within a single patient.

Table 1: Comparing Genes-First and Phenotypes-First Resistance Pathways

| Feature | Genes-First Pathway | Phenotypes-First Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Event | New gene mutation (e.g., in drug target) | Phenotypic variability and plasticity in isogenic cells |

| Stability | Heritable from onset | Initially transient, may stabilize later |

| Primary Driver | DNA-level events | Cell-intrinsic plasticity & microenvironmental signals |

| Detection Method | Genome sequencing | Single-cell transcriptomics, functional assays |

| Exemplary Context | BCR-ABL1 mutations in CML [18] | Ovarian cancer adaptation to Olaparib [18] |

Quantitative data from a meta-analysis of HIV-1 further illustrates the practical output of such research, demonstrating the prevalence of drug resistance mutations (DRMs) across different drug classes.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of HIV-1 Drug Resistance Mutations in East Africa (2025 Data)

| Antiretroviral Drug Class | Prevalence of DRMs | Most Frequent Mutations |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTI) | 36.5% | K103N |

| Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTI) | 25.5% | M184V |

| Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (INSTI) | 3.7% | - |

Data derived from 7,614 HIV-1 pol gene sequences. INSTI resistance, while currently low, warrants ongoing monitoring due to its clinical significance [19].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: DIvERGE in Bacterial Systems

Purpose: To rapidly generate and select for antibiotic resistance mutations in predefined genomic loci of bacterial species. Principle: This method uses pools of soft-randomized single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) oligonucleotides that fully cover the target locus. These oligos are incorporated into the genome via recombineering, introducing random mutations with a tunable rate and a uniform spectrum [17].

Procedure:

- Oligo Library Design and Synthesis:

- Design 90-nt ssDNA oligos complementary to the target genomic region, with oligos aligned in a partially overlapping pattern.

- Synthesize the oligo pool using a soft-randomization protocol. Spiking with a defined ratio (e.g., 2-5%) of mismatching nucleotides during synthesis ensures each possible mutation is represented while maintaining sufficient similarity to the wild-type sequence for efficient incorporation [17].

- Bacterial Preparation and Transformation:

- Grow the bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli K-12 MG1655) to mid-log phase.

- Induce the expression of recombineering proteins (e.g., using the pORTMAGE system) to make the cells competent for ssDNA incorporation [17].

- Electroporate the synthesized oligo pool into the competent cells.

- Mutagenesis and Selection:

- Allow for oligo incorporation and mutant outgrowth. This constitutes one DIvERGE cycle.

- Perform multiple iterative cycles (e.g., 5 cycles) to increase genetic diversity.

- Plate the mutagenized population on agar containing the antibiotic of interest at a concentration that inhibits wild-type growth.

- Isolate resistant colonies for downstream analysis [17].

- Analysis and Validation:

- Prepare genomic DNA from resistant clones.

- Sequence the targeted genomic regions using Illumina high-throughput sequencing to identify the precise resistance-conferring mutations [17].

Protocol B: In Vitro Evolution in Haploid Human Cells (IVIEWGA)

Purpose: To study chemotherapy drug resistance and identify resistance genes or drug targets in an isogenic human background. Principle: A near-haploid human cell line (HAP1) is subjected to increasing sublethal concentrations of a drug over multiple generations. Resistant clones are sequenced to identify de novo variants that confer the resistance phenotype [20].

Procedure:

- Cell Line and Compound Selection:

- Culture the HAP1 cell line, a near-haploid line derived from chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).

- Select compounds with potent growth inhibition (EC50 < 1 µM is ideal). Validate efficacy using a 48-hour dose-response assay (e.g., with CellTiterGlo) [20].

- Cloning and Selection for Resistance:

- Clone the parent HAP1 cells by limiting dilution to ensure an isogenic starting population.

- Initiate independent selection series from different parent clones.

- For each series, expose cells to a sublethal concentration of the drug (e.g., doxorubicin, gemcitabine).

- Once cells recover, apply a lethal challenge (~3-5 × EC50). Alternatively, use a stepwise selection method, increasing the drug concentration by 5-10% every 5 days.

- Continue selection for several weeks to months until resistant populations emerge [20].

- Phenotypic Validation and Sequencing:

- Isolate clones from the resistant populations.

- Confirm stable resistance by re-testing the EC50 after culturing without drug pressure for 8 weeks.

- Perform whole-genome or exome paired-end sequencing on resistant clones and their matched, drug-sensitive parent clones [20].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Develop a pipeline to compare resistant and sensitive genomes.

- Filter for high-frequency alleles that change protein sequence.

- Prioritize alleles that appear in the same gene across multiple independent selections with the same compound, as this provides high statistical confidence [20].

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core experimental workflow and the conceptual models of resistance emergence.

Diagram 1: DIvERGE Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Resistance Evolution Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and resources essential for implementing the described protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Soft-Randomized ssDNA Oligo Pools [17] | Induce random, tunable mutations in long, predefined genomic targets during DIvERGE. | Overlapping design; spiking with mismatching nucleotides (2-5%); 90-nt length. |

| pORTMAGE System [17] | Enables highly efficient allelic replacement in E. coli without off-target effects for DIvERGE. | Plasmid-based system for expressing recombineering proteins. |

| HAP1 Cell Line [20] | Near-haploid human cell line for IVIEWGA, simplifying the identification of resistance-conferring variants. | Haploid for all chromosomes except a fragment of chr15; exposes mutated phenotypes. |

| Stanford HIV Drug Resistance Database (HIVDB) [19] | Online tool for identifying and interpreting HIV-1 drug resistance mutations in sequenced isolates. | Curated public database; uses sequence data to predict resistance to ARV drugs. |

| Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) [21] | High-throughput method for discovering and genotyping SNPs in diverse germplasm, e.g., plant collections. | Identifies 100,000+ SNPs; used for population structure and GWAS. |

The fields of directed evolution and resistance gene identification represent pillars of modern biotechnology and therapeutic development. These disciplines, though seemingly distinct, share a common historical foundation built upon the pioneering work of Sol Spiegelman and his contemporaries in nucleic acid research. This application note traces the critical path from these early molecular experiments to the sophisticated high-throughput screening (HTS) technologies available today. By examining key milestones and methodologies, we provide researchers with both a historical framework and practical protocols to advance their work in engineering biomolecules and identifying genetic determinants of resistance. The integration of directed evolution with whole-genome sequencing has created a powerful paradigm for interrogating biological function, accelerating the development of novel enzymes, therapeutics, and diagnostic tools.

Historical Timeline and Key Developments

The following table summarizes the pivotal milestones that have shaped directed evolution and screening technologies since Spiegelman's foundational experiments.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Directed Evolution and Screening

| Year | Milestone | Key Researchers/Group | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | Invention of DNA-RNA Hybridization | Hall and Spiegelman [22] | Provided first direct evidence of RNA as a DNA transcript; enabled detection of specific genetic sequences. |

| 1965 | Spiegelman's Monster Experiment | Spiegelman et al. [23] | Demonstrated first in vitro Darwinian evolution of RNA; showed selective pressure (replication speed) drives evolution of minimal replicons (218 nucleotides). |

| 1967 | Pioneering in vitro Evolution | Spiegelman [2] | Established foundational principles for all subsequent directed evolution work. |

| 1975 | De novo RNA Generation | Sumper and Luce [23] | Showed Qβ replicase could spontaneously generate self-replicating RNA, bridging prebiotic chemistry and early evolution. |

| 1980s-1990s | Phage Display Development | Smith et al. [2] | Provided first application-driven directed evolution platform for selecting binding peptides and antibodies. |

| 1990s-2000s | Automation & Miniaturization | Various (Industry & Academia) [2] [24] | Enabled High-Throughput Screening (HTS), dramatically increasing testing capacity to >100,000 compounds per day [24]. |

| 2000s-Present | Advanced Recombination Methods | Various [2] | Development of DNA shuffling, StEP, and other methods to overcome limitations of point mutagenesis. |

| 2025 | AI-Powered RNA Structure Prediction | Kihara Lab (NuFold) [25] | End-to-end deep learning approach for predicting RNA 3D structure from sequence, accelerating RNA-targeted drug discovery. |

The progression from these foundational discoveries to modern applications illustrates a consistent trend toward greater throughput, miniaturization, and computational integration. Spiegelman's work established the core principle that evolutionary pressures could be applied in a controlled laboratory environment to select for desired molecular traits. This principle now underpins sophisticated campaigns to identify resistance genes and engineer novel biocatalysts.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro RNA Evolution (Based on Spiegelman's Experiment)

This protocol outlines the core procedure for the Darwinian evolution of RNA molecules in a cell-free system, replicating the essential elements of Spiegelman's work [23].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Qβ Bacteriophage RNA: The initial template (~4500 nucleotides).

- Qβ Replicase: RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from the Qβ bacteriophage.

- Nucleotide Mixture: Contains ATP, GTP, CTP, and UTP.

- Replication Buffer: Provides optimal ionic strength and pH for Qβ replicase activity.

- Dilution Buffer: Fresh replication buffer for serial transfers.

2. Procedure: 1. Initial Reaction Setup: In a microcentrifuge tube, combine the following: - 1 µg Qβ RNA - 10 U Qβ Replicase - 1 mM each NTP - 1X Replication Buffer - Bring to a final volume of 100 µL with nuclease-free water. 2. Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 37°C for 20 minutes to allow for RNA replication. 3. Serial Transfer: Take a 10 µL aliquot from the initial reaction and transfer it to a new tube containing 90 µL of fresh, pre-warmed Replication Buffer with NTPs and Qβ Replicase. 4. Repetition: Repeat the serial transfer process (Step 3) every 20 minutes. This constitutes one "generation." 5. Monitoring: Continue the serial transfers for 74 or more generations. Monitor the reaction products periodically by denaturing gel electrophoresis (e.g., 8% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gel).

3. Analysis:

- Gel Electrophoresis: Analyze the RNA products from different generations. A progressive shift toward faster-migrating (shorter) RNA species over time will be visually evident.

- Sequencing: Extract the dominant RNA band from the final generations and subject it to RNA sequencing to confirm the emergence of a minimal replicon (~218 nucleotides) [23].

4. Key Considerations:

- Aseptic Technique: Maintain RNase-free conditions throughout the procedure to prevent RNA degradation.

- Control Reactions: Include a control without Qβ replicase to confirm that replication is enzyme-dependent.

- Selection Pressure: The dilution factor and fixed incubation time create the selective pressure for faster-replicating (and consequently shorter) RNA molecules.

Protocol 2: A Modern High-Throughput Screening Workflow for Enzyme Variants

This protocol describes a generic, cell-based HTS workflow suitable for identifying enzyme variants with improved properties (e.g., activity, stability) from a library generated by directed evolution [2] [24] [26].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Variant Library: A library of clones (e.g., in E. coli) expressing different enzyme variants.

- Assay Plates: 384-well or 1536-well microplates.

- Growth Medium: Appropriate sterile liquid medium with selective antibiotic.

- Substrate: A fluorogenic or chromogenic substrate that yields a detectable signal upon enzyme activity.

- Lysis Buffer: (If needed) A buffer to permeabilize cells and release the enzyme.

- Stop Solution: A reagent to quench the reaction at the endpoint.

2. Procedure: 1. Cell Dispensing: Using a liquid handler, dispense a suspension of each variant clone into individual wells of the assay plate. Include positive (wild-type enzyme) and negative (empty vector) controls in designated wells. 2. Cell Growth: Incubate the assay plates at the appropriate temperature with shaking to allow for cell growth and enzyme expression. 3. Assay Initiation: Add the substrate solution to all wells, either manually or via automated dispensing. 4. Signal Incubation: Incubate the plates for a predetermined time to allow the enzymatic reaction to proceed. 5. Signal Detection: Read the plate using a microplate reader configured for absorbance, fluorescence, or luminescence detection.

3. Analysis: 1. Data Normalization: Normalize the raw signal from each well against the positive and negative controls on the same plate. A common metric is the Z'-factor, which assesses the quality of the assay based on the separation between positive and negative controls [26]. 2. Hit Identification: Variants that produce a signal statistically significantly above a set threshold (e.g., 3 standard deviations above the mean of the negative control) are designated as "hits" [26]. 3. Validation: The hits from the primary screen are re-tested in a secondary, more quantitative screen (e.g., to determine IC50 or Ki values) to confirm the desired activity.

4. Key Considerations:

- Assay Robustness: The assay must be optimized for minimal variability and a high Z'-factor (>0.5 is excellent) before screening the entire library.

- Automation: The entire process is typically automated using robotic systems for plate handling, liquid dispensing, and incubation to achieve high throughput [26].

- Miniaturization: Using 1536-well plates and low (µL) volumes reduces reagent costs and enables ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) [24].

The logical flow of this HTS protocol, from library preparation to hit validation, is depicted below.

Diagram 1: HTS Workflow for Enzyme Variants

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of directed evolution and HTS campaigns relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key components for building and screening genetic libraries.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution and HTS

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Qβ Replicase | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase that catalyzes RNA replication. | In vitro evolution of RNA molecules (e.g., Spiegelman's Monster) [23]. |

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Introduces random point mutations into a gene of interest during amplification. | Generating genetic diversity for the first step of a directed evolution campaign [2]. |

| DNA Shuffling Kit | Recombines fragments of homologous genes to create chimeric libraries. | Accelerating evolution by combining beneficial mutations from different parent genes [2]. |

| KAPA HiFi DNA Polymerase | A high-fidelity polymerase engineered via directed evolution for ultra-high accuracy in PCR. | High-fidelity amplification of NGS libraries to avoid introducing errors during preparation [14]. |

| 384/1536-Well Microplates | Miniaturized assay plates that enable high-density, low-volume reactions. | Conducting HTS assays to screen hundreds of thousands of compounds or enzyme variants [24] [26]. |

| Fluorogenic/Chromogenic Substrates | Compounds that produce a measurable signal (fluorescence/color) upon enzyme activity. | Detecting and quantifying enzyme activity in a high-throughput format [26]. |

| NuFold Algorithm | A deep learning-based computational tool for predicting RNA 3D structure from sequence. | Accelerating RNA-targeted drug discovery by providing structural models where experimental data is lacking [25]. |

The strategic selection of these reagents is critical for experimental success. For instance, the choice of DNA polymerase can directly impact the quality and diversity of a mutant library, while the selection of an appropriate substrate is paramount for developing a robust HTS assay.

Integrated Data Analysis and Interpretation

The massive datasets generated by HTS require robust analytical methods for quality control and hit selection. Key metrics include the Z-factor, which evaluates the quality and separation band of an assay, and the Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD), which is a more powerful statistic for assessing the size of effects and data quality [26]. For hit selection in screens without replicates, the z-score method is often employed, whereas screens with replicates benefit from the use of t-statistics or SSMD, which can directly estimate variability for each compound [26].

The integration of whole-genome sequencing with HTS data is a cornerstone of resistance gene identification. After an HTS campaign identifies a clone with a desired phenotype (e.g., drug resistance), its genome is sequenced and compared to the parent strain. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions, deletions, and gene amplifications are identified. The causal mutation is then confirmed by reintroducing it into a naive background and re-assaying the phenotype. This closed-loop workflow powerfully links genotype to phenotype.

The logical progression from a phenotypic screen to the identification of a causal gene is summarized in the following diagram.

Diagram 2: Resistance Gene Identification Workflow

The journey from Spiegelman's simple test tube containing a "monster" RNA to the automated, AI-enhanced laboratories of today underscores a remarkable trajectory in biotechnology. The core principle remains unchanged: the application of selective pressure to populations of biomolecules drives the evolution of desired traits. However, the tools available to the researcher have been transformed. Modern directed evolution leverages high-throughput methodologies that allow for the screening of library sizes unimaginable just decades ago. Furthermore, the integration of whole-genome sequencing provides an unambiguous link between selected phenotype and underlying genotype, making the identification of resistance genes and beneficial mutations a systematic process. As computational tools like NuFold [25] continue to mature and merge with experimental screening, the cycle of design-build-test-learn will only accelerate, opening new frontiers in enzyme engineering, drug discovery, and fundamental biological research.

Application Notes

The relentless evolution of bacterial pathogens and the escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) demand a new generation of precise and adaptable countermeasures. The integration of directed evolution with advanced whole-genome sequencing (WGS) technologies is creating a powerful paradigm shift in how we identify resistance genes and engineer novel biological agents to combat pathogens. This approach moves beyond static solutions, allowing researchers to rapidly optimize biomolecules and therapies in direct response to the genetic mechanisms of resistance. The following application notes illustrate the breadth of this expanding scope, showcasing how these technologies are being deployed to develop new antimicrobials, gene therapies, and pathogen control strategies.

Application Note 1: Engineering Host-Defense Peptides as Non-Resistance-Inducing Antimicrobials

- Challenge: Conventional antibiotics increasingly fail due to resistance, and the pharmaceutical pipeline for novel antibiotics is limited. There is a critical need for new classes of antimicrobials that attack bacteria via mechanisms for which resistance is difficult to develop.

- Solution & Technology: Recent research has re-examined human chemokines, a class of immune signaling molecules known to have secondary antimicrobial properties. Using structure-function studies guided by mechanistic insights, researchers are engineering these peptides to enhance their direct killing power.

- Key Experimental Data: Investigations revealed that specific chemokines, such as CCL20, kill bacteria by binding to negatively charged phospholipids (cardiolipin and phosphatidylglycerol) in the bacterial cell membrane and disrupting its integrity [27]. Crucially, unlike conventional antibiotics, repeated exposure to CCL20 did not lead to increased bacterial resistance, even after multiple generations [27].

- Insight: This approach leverages a fundamental vulnerability—the bacterial membrane—which is less mutable than the protein targets of many antibiotics. Directed evolution campaigns can now be designed to optimize chemokine variants for enhanced binding to these phospholipids, creating a promising new class of resistance-resistant therapeutics.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Antimicrobial Chemokine Activity

| Chemokine/Peptide | Target Bacteria | Key Mechanism | Resistance Development? |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCL20 | E. coli | Binds cardiolipin & phosphatidylglycerol, disrupting cell membrane | No resistance observed after multiple exposures [27] |

| Beta-defensin 3 (Comparison) | E. coli | Antimicrobial peptide activity | Not specified in study [27] |

Application Note 2: Directed Evolution of Bridge Recombinases for Universal Gene Replacement Therapies

- Challenge: Correcting large or diverse genetic mutations in monogenic diseases is inefficient with CRISPR-based tools, which rely on error-prone DNA repair and struggle with inserting full-length genes.

- Solution & Technology: Bridge recombinases are a novel class of genome-editing enzymes that use a bridge RNA (bRNA) to precisely insert large DNA donor fragments into a genome without creating double-stranded breaks [28]. To enhance their efficiency and specificity for therapeutic use, researchers are applying directed evolution.

- Key Experimental Data: A proof-of-concept project targeting Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (A1ATD) has established a complete workflow. This includes:

- Identification of target sites in the SERPINA1 gene.

- Use of deep mutational learning (DML), a machine-learning method, to screen thousands of recombinase variants [28].

- Implementation of two directed evolution systems: E. coli Orthogonal Replicon (EcORep) and Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution (PACE) to select for recombinases with improved activity [28].

- Insight: The goal is a universal therapy where a single evolved bridge recombinase can insert a healthy gene copy to treat all patients with a disease, regardless of their specific mutation. This demonstrates how WGS identifies pathogenic mutations, and directed evolution creates the tools to correct them.

Application Note 3: Expanding Phage Host Range to Target Multidrug-Resistant Infections

- Challenge: Bacteriophage (phage) therapy is a promising alternative to antibiotics, but naturally occurring phages often have a narrow host range, limiting their utility against diverse clinical isolates of a pathogen like Klebsiella pneumoniae.

- Solution & Technology: The Appelmans protocol (in vitro directed evolution) was used to train a cocktail of five myophages against a panel of 11 bacterial strains, including phage-resistant clinical isolates [29].

- Key Experimental Data: After multiple passages, evolved phage variants were isolated and sequenced. The study found:

- Host Range Shift: Some variants gained the ability to lyse previously resistant strains while losing activity against formerly susceptible ones.

- Host Range Expansion: Several variants demonstrated broadly expanded activity [29].

- Genetic Basis: Whole-genome sequencing identified that mutations and recombination events in tail fiber genes were likely responsible for the altered host tropism [29].

- Insight: Directed evolution is a powerful method to generate phages with tailored host ranges for therapeutic cocktails, overcoming a major limitation of phage therapy and providing a dynamic strategy to combat evolving multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Table 2: Outcomes of Phage Host Range Expansion via Directed Evolution

| Phage Variant Type | Change in Host Range | Primary Genetic Mechanism | Therapeutic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant A | Expanded to include previously resistant strains | Mutations in tail fiber genes [29] | High; improves cocktail coverage |

| Variant B | Shifted from old hosts to new resistant hosts | Recombination events in tail fiber genes [29] | Moderate; requires careful cocktail design |

Experimental Protocols

The following protocols provide detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the application notes, enabling researchers to replicate and build upon these advanced techniques.

Protocol 1: In Vitro Directed Evolution of Phages Using the Appelmans Protocol

Purpose: To isolate bacteriophage variants with expanded or altered host ranges for therapeutic use against multidrug-resistant bacterial strains [29].

Materials:

- Bacterial Strains: A panel of target bacterial strains, including a permissive host and clinical phage-resistant isolates.

- Parental Phages: A mixture of phages with complementary initial host ranges.

- Growth Media: Appropriate liquid broth (e.g., LB) and soft agar for plaque assays.

- Equipment: Sterile culture flasks/tubes, incubator, centrifuge, filtration units (0.22 µm).

Procedure:

- Preparation: Mix the parental phage cocktail and a portion of the bacterial panel (excluding the permissive host) in a flask containing growth medium.

- Co-culture Incubation: Incubate the culture with shaking until visible lysis is observed or for a predetermined period (e.g., 24 hours).

- Harvesting: Centrifuge the culture to remove bacterial debris. Filter the supernatant through a 0.22 µm filter to obtain a phage lysate containing progeny from the initial round.

- Repassaging: Use a small volume of the filtered lysate to infect a fresh batch of the bacterial panel. Repeat steps 2-4 for multiple serial passages (e.g., 10-20 rounds).

- Plaque Isolation & Screening: After the final passage, perform plaque assays on both the permissive host and the previously resistant strains. Isplicate individual plaques from plates showing lysis.

- Characterization: Amplify the isolated phage variants and characterize their new host ranges against a comprehensive diversity panel of bacterial strains. Confirm genomic changes through whole-genome sequencing [29].

Protocol 2: Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment (QMRA) Integrating ARG Mobility from Metagenomic Data

Purpose: To move beyond simple abundance counts of Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs) and incorporate their mobility potential, as a proxy for dissemination risk, into environmental surveillance risk models [30].

Materials:

- Environmental Samples: (e.g., water, sediment, wastewater).

- DNA Extraction Kit: Suitable for complex environmental samples.

- Sequencing Platform: Illumina, Oxford Nanopore, or PacBio for metagenomic sequencing.

- Bioinformatics Tools: ARG databases (CARD, ResFinder), MGE databases, metagenomic assembly tools (SPAdes, metaSPAdes), and contig binning software.

Procedure:

- Sample Collection & DNA Extraction: Collect environmental samples in triplicate. Extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA.

- Metagenomic Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries and perform whole-community shotgun sequencing using short-read (Illumina) and/or long-read (Nanopore, PacBio) technologies to facilitate better assembly [30].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Assembly & Binning: Assemble quality-filtered reads into contigs. Bin contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) to infer bacterial hosts.

- ARG & MGE Annotation: Annotate contigs using ARG and MGE databases to identify resistance determinants and mobile genetic elements (plasmids, integrons, transposons).

- Mobility Linkage: Analyze co-localization of ARGs and MGEs on the same contig or within the same MAG. This physical linkage is a strong indicator of mobility potential [30].

- Risk Integration: Calculate a risk score that incorporates both the abundance of high-risk ARGs (e.g., those ranked by clinical relevance) and their association with MGEs. Integrate this score into a QMRA framework for hazard identification and exposure assessment [30].

Protocol 3: Engineering a Chimeric Peptidoglycan Hydrolase for Enhanced Anti-Listerial Activity

Purpose: To improve the efficacy and specificity of a novel M23 peptidase (StM23) against Listeria monocytogenes by creating a chimeric enzyme fused with a high-affinity cell wall-targeting domain [31].

Materials:

- Gene Fragments: DNA encoding the catalytic domain of StM23 and the cell wall-targeting domain (CWT) from Staphylococcus pettenkoferi (SpM23B).

- Expression Vector & Host: Plasmid (e.g., pET series) and E. coli expression strain (e.g., BL21(DE3)).

- Chromatography Systems: Equipment for protein purification (e.g., Ni-NTA affinity chromatography).

- Bacterial Strains: Target strains (e.g., L. monocytogenes, Bacillus subtilis) and safety evaluation models (zebrafish, moth larvae, human cell lines).

Procedure:

- Gene Design & Synthesis: Design a synthetic gene encoding the StM23 catalytic domain fused via a flexible linker to the SpM23B CWT domain. The construct is codon-optimized for the expression host.

- Cloning & Expression: Clone the chimeric gene (StM23_CWT) into an expression vector. Transform into the expression host and induce protein production with IPTG.

- Protein Purification: Lyse the cells and purify the chimeric enzyme using affinity chromatography based on an engineered tag (e.g., His-tag).

- Enzyme Characterization:

- Activity Assay: Measure bacteriolytic activity against planktonic cultures of L. monocytogenes and other Gram-positive bacteria. Compare the chimeric enzyme's efficacy to the EAD-alone construct.

- Biofilm Disruption: Test the ability of StM23_CWT to disrupt pre-formed biofilms on relevant surfaces (glass, stainless steel, silicone).

- Environmental Tolerance: Assess enzymatic activity under varying pH and salt conditions to determine industrial applicability [31].

- Safety Evaluation: Conduct toxicity assessments using zebrafish embryos, moth larvae, and human cell culture models to confirm a non-toxic profile [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and tools essential for research in directed evolution and antimicrobial discovery.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Directed Evolution and Pathogen Combatting

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution (PACE) | Links target protein activity to phage replication, enabling continuous directed evolution without intervention [28]. | Evolving bridge recombinases for improved gene insertion efficiency [28]. |

| Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) | A manually curated resource and ontology for identifying AMR genes and mutations from genomic data [6]. | Annotating and predicting ARGs from whole-genome or metagenome sequences in surveillance studies [6]. |

| Bridge Recombinase System | An RNA-guided system for precise insertion of large DNA fragments without double-strand breaks [28]. | Developing universal gene replacement therapies for monogenic diseases like Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency [28]. |

| High-Throughput qPCR (HT-qPCR) | Allows simultaneous quantification of hundreds of ARGs and MGEs from environmental or clinical DNA extracts [32]. | Profiling the abundance and diversity of resistance genes in wastewater to assess environmental impact [32]. |

| Antibiotic Resistance Gene Index (ARGI) | A standardized metric to compare overall AMR levels across different samples or studies [32]. | Benchmarking the performance of wastewater treatment plants in reducing AMR load [32]. |

From Mutation to Data: A Step-by-Step Pipeline for Resistance Gene Identification

Directed evolution stands as a powerful protein engineering methodology that mimics natural evolution in laboratory settings, enabling the development of biomolecules with enhanced or novel properties for therapeutic, industrial, and research applications [2]. This approach has revolutionized our ability to optimize enzymes, antibodies, and other proteins without requiring comprehensive prior knowledge of structure-function relationships [33]. The fundamental process of directed evolution consists of two critical phases: (1) the creation of genetic diversity (library generation), and (2) the screening or selection of variants with desired traits [2]. Library generation techniques form the foundation of this process, determining the nature and quality of diversity available for selection. Within the specific context of resistance gene identification research, these methodologies enable the systematic investigation of molecular adaptation mechanisms and the identification of critical genetic determinants conferring resistance phenotypes [6] [20]. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for three key library generation techniques—Error-Prone PCR, DNA Shuffling, and RAISE—framed within directed evolution and whole-genome sequencing for resistance gene identification.

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Key Library Generation Techniques

| Technique | Primary Mechanism | Diversity Type | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR | Random point mutations during PCR amplification | Point mutations throughout sequence | • Does not require prior structural knowledge• Technically straightforward to perform• Wide accessibility [33] | • Biased mutation spectrum• Limited amino acid substitutions due to codon bias [33]• Reduced sampling of mutagenesis space [2] | • Initial exploration of sequence-function relationships• Stability engineering• Activity optimization |

| DNA Shuffling | Fragmentation and recombination of homologous sequences | Recombination of existing diversity | • Combines beneficial mutations• Can remove deleterious mutations [33]• Mimics natural evolutionary process | • Requires high sequence homology between parents [2]• Can introduce unwanted neutral mutations | • Family shuffling of homologous genes• Directed evolution of multi-domain proteins• Pathway engineering |

| RAISE | Random insertion and deletion of short sequences | Insertions and deletions (indels) | • Generates random indels across sequence• Accesses distinct mutational space compared to point mutations [2] | • Can introduce frameshifts• Limited to small insertions/deletions | • Exploring structural flexibility• Loop engineering• Domain linking optimization |

Method Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate library generation method depends on several factors, including the starting genetic material, desired diversity type, and screening capabilities. Error-prone PCR serves as an excellent starting point for novel targets with limited structural information, providing broad mutational coverage across the entire gene [33]. DNA shuffling demonstrates particular utility when multiple parent sequences with beneficial mutations are available, enabling the combination of advantageous traits [33] [2]. RAISE offers unique capabilities for exploring structural conformations and access to distinct sequence space through indel mutations, which are underrepresented in other methods [2]. For comprehensive resistance gene studies, iterative approaches combining these techniques often yield superior results, allowing researchers to explore diverse mutational landscapes and identify non-obvious resistance mechanisms.

Error-Prone PCR: Application Notes and Protocols

Principle and Applications in Resistance Research

Error-prone PCR (epPCR) introduces random point mutations throughout a DNA sequence by reducing the fidelity of DNA polymerase during amplification [33]. This technique has become one of the most accessible and widely used methods for generating initial diversity in directed evolution experiments, particularly for investigating resistance mechanisms [33] [34]. In resistance gene identification, epPCR enables researchers to explore how random mutations throughout a gene sequence affect drug binding, efflux, or metabolic bypass mechanisms. The method's advantage lies in its ability to identify unexpected resistance mutations outside of known functional domains, potentially revealing novel resistance mechanisms [20].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Table 2: Error-Prone PCR Reaction Setup

| Component | Standard PCR | Error-Prone PCR | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | 1-10 ng | 1-10 ng | Target gene for mutagenesis |

| Primers | 0.2-0.5 μM each | 0.2-0.5 μM each | Gene-specific amplification |

| dNTPs | 200 μM each | Unequal concentrations (e.g., 0.2 mM dGTP, 1 mM dTTP) [33] | Increased misincorporation |

| MgCl₂ | 1.5-2.0 mM | 2.5-7.0 mM | Reduced fidelity, enhanced processivity |

| Additional Cations | None | 0.1-0.5 mM MnCl₂ [33] | Significant reduction in polymerase fidelity |

| Polymerase | High-fidelity Taq | Standard Taq or error-prone variants | DNA amplification |

| Buffer | Manufacturer's recommendation | Manufacturer's recommendation | Optimal enzyme activity |

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare the error-prone PCR reaction mixture according to Table 2 components in a total volume of 50 μL. MnCl₂ should be added after other components as it can precipitate in PCR buffer.

- Thermal Cycling:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes

- 25-35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 55-65°C (gene-specific) for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute/kb

- Final extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes

- Mutation Rate Control: Modulate mutation frequency by adjusting Mn²⁺ concentration (0.1-0.5 mM) and number of PCR cycles [33]. Higher Mn²⁺ and more cycles increase mutation rates.