From Trial-and-Error to AI: The Evolution of the Chemical Biology Platform in Modern Drug Discovery

This article traces the transformative journey of the chemical biology platform from its origins bridging chemistry and pharmacology to its current state as a multidisciplinary, AI-powered engine for drug discovery.

From Trial-and-Error to AI: The Evolution of the Chemical Biology Platform in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article traces the transformative journey of the chemical biology platform from its origins bridging chemistry and pharmacology to its current state as a multidisciplinary, AI-powered engine for drug discovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles established in the late 20th century, the integration of modern methodologies like AI and high-throughput screening, strategic solutions for persistent bottlenecks, and the comparative analysis of contemporary platforms driving translational success. By synthesizing historical context with 2025 trends, this review provides a comprehensive roadmap for designing mechanistic studies that effectively incorporate translational physiology and precision medicine.

The Roots of Revolution: Bridging Chemistry and Biology for Targeted Therapies

The final quarter of the 20th century marked a pivotal juncture in pharmaceutical research. While the era saw the development of increasingly potent compounds capable of targeting specific biological mechanisms with high affinity, the industry collectively faced a formidable obstacle: demonstrating unambiguous clinical benefit in patient populations [1]. This challenge, often termed the "translational gap," between laboratory efficacy and clinical success, necessitated a fundamental restructuring of drug discovery and development philosophies. The inability to reliably predict which potent compounds would deliver therapeutic value in costly late-stage clinical trials acted as the primary catalyst for change, spurring the evolution from traditional, siloed approaches toward the integrated, multidisciplinary framework known as the chemical biology platform [1]. This platform emerged as the engine for a new paradigm, bridging the disciplines of chemistry, physiology, and clinical science to foster a mechanism-based approach to clinical advancement.

The Historical Imperative: From Serendipity to Systems

The traditional drug development model, which relied heavily on trial-and-error and phenotypic screening in animal models, became increasingly unsustainable in the face of growing regulatory and economic pressures [1]. The Kefauver-Harris Amendment of 1962, enacted in reaction to the thalidomide tragedy, formally demanded proof of efficacy from "adequate and well-controlled" clinical trials, fundamentally altering the landscape by dividing the clinical evaluation process into distinct phases (I, IIa, IIb, and III) [1]. This regulatory shift underscored the inadequacy of existing models and highlighted the urgent need for a more predictive, science-driven framework.

The initial response within the industry was to bridge the foundational disciplines of chemistry and pharmacology. Chemists focused on synthesis and scale-up, while pharmacologists and physiologists used animal and cellular models to demonstrate potential therapeutic benefit and develop absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) profiles [1]. However, this linear process lacked a formal mechanism for connecting preclinical findings to human clinical outcomes, leaving a critical gap in predicting which compounds would ultimately prove successful.

The Chemical Biology Platform: A New Organizational Framework

The chemical biology platform was introduced as an organizational strategy to systematically optimize drug target identification and validation, thereby improving the safety and efficacy of biopharmaceuticals [1]. Unlike its predecessors, this platform leverages a multidisciplinary team to accumulate knowledge and solve problems, often relying on parallel processes to accelerate timelines and reduce the costs of bringing new drugs to patients [1].

Core Principles and Definitions

- Chemical Biology: The study and modulation of biological systems using small molecules, often selected or designed based on the structure, function, or physiology of biological targets. It involves creating biological response profiles to understand protein network interactions [1].

- Translational Physiology: The examination of biological functions across multiple levels of organization, from molecules and cells to organs and populations. It forms the core of the chemical biology platform by providing the essential biological context [1].

- Platform Goal: To connect a series of strategic steps that determine whether a newly developed compound could translate into clinical benefit, using translational physiology as a guiding principle [1].

The Four-Step Catalyst Framework

A pivotal, systematic framework based on Koch's postulates was developed to indicate the potential clinical benefit of new agents [1]. This framework provided the necessary rigor to transition from potent compounds to clinical proof.

Table 1: The Four-Step Framework for Establishing Clinical Proof

| Step | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify a Disease Biomarker | Identify a specific, measurable parameter linked to the disease pathophysiology. | To establish an objective, quantifiable link between a biological process and a clinical condition. |

| 2. Modify Parameter in Animal Model | Demonstrate that the drug candidate modifies the identified biomarker in a relevant animal model of the disease. | To provide initial proof of biological activity in a living system. |

| 3. Modify Parameter in Human Disease Model | Show that the drug modifies the same parameter in a controlled human disease model. | To bridge the gap from animal physiology to human biology and establish early clinical feasibility. |

| 4. Demonstrate Dose-Dependent Clinical Benefit | Establish a correlation between the drug's dose, the change in the biomarker, and a corresponding clinical benefit. | To confirm the therapeutic hypothesis and validate the biomarker as a surrogate for clinical outcome. |

A seminal case study that validated this approach was the development and subsequent termination of CGS 13080, a thromboxane synthase inhibitor from Ciba [1]. The framework successfully guided the evaluation: the drug was shown to decrease thromboxane B2 (Step 1-3) and reduce pulmonary vascular resistance in patients undergoing mitral valve surgery (Step 4). However, the program was terminated due to a very short half-life and the infeasibility of creating an effective oral formulation [1]. This example underscores how the platform enables early, data-driven decisions to terminate non-viable compounds, preventing costly late-stage failures.

Enabling Technologies and Methodologies

The chemical biology platform synergized with concurrent technological revolutions, dramatically enhancing its predictive power.

The Molecular Biology and Omics Revolution

Advances in molecular biology provided the tools to identify and target specific DNA, RNA, and proteins involved in disease processes [1]. The development of immunoblotting in the late 1970s and early 1980s, for instance, allowed for the relative quantitation of protein abundance. This evolved into modern systems biology techniques, which the platform integrates to understand protein network interactions. These include:

- Transcriptomics: For analyzing global gene expression patterns.

- Proteomics: For large-scale study of protein expression and function.

- Metabolomics: For profiling the unique chemical fingerprints of cellular processes [1].

High-Throughput and High-Content Screening

The rise of combinatorial chemistry and high-throughput screening (HTS) enabled the rapid testing of vast compound libraries against defined molecular targets [1]. This was complemented by high-content analysis, which uses automated microscopy and image analysis to quantify multiparametric cellular events such as:

- Cell viability and apoptosis

- Cell cycle analysis

- Protein translocation

- Phenotypic profiling [1]

Additional cellular assays integral to the platform include reporter gene assays for assessing signal activation and various techniques, including voltage-sensitive dyes and patch-clamp electrophysiology, for screening ion channel targets in neurological and cardiovascular diseases [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental workflows within the chemical biology platform rely on a suite of essential reagents and materials.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions in the Chemical Biology Platform

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|

| Small Molecule Compounds | Chemical tools to perturb and study specific biological targets and pathways; used for dose-response studies and phenotypic screening. |

| Antibodies (Primary & Secondary) | Key reagents for immunoblotting (Western Blot), immunofluorescence, and immunohistochemistry to detect and quantify specific protein targets. |

| Reporter Gene Constructs (e.g., Luciferase, GFP) | Engineered DNA vectors used in reporter assays to visualize and quantify signal transduction pathway activation upon ligand-receptor engagement. |

| Voltage-Sensitive Dyes | Fluorescent probes used to screen ion channel activity and monitor changes in membrane potential in cellular assays. |

| Cell Viability/Proliferation Assay Kits (e.g., MTT, ATP-based) | Reagents to quantitatively measure the effects of compounds on cell health, proliferation, and death. |

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | Synthetic RNA molecules for targeted gene knockdown, enabling functional validation of drug targets in genetic screens. |

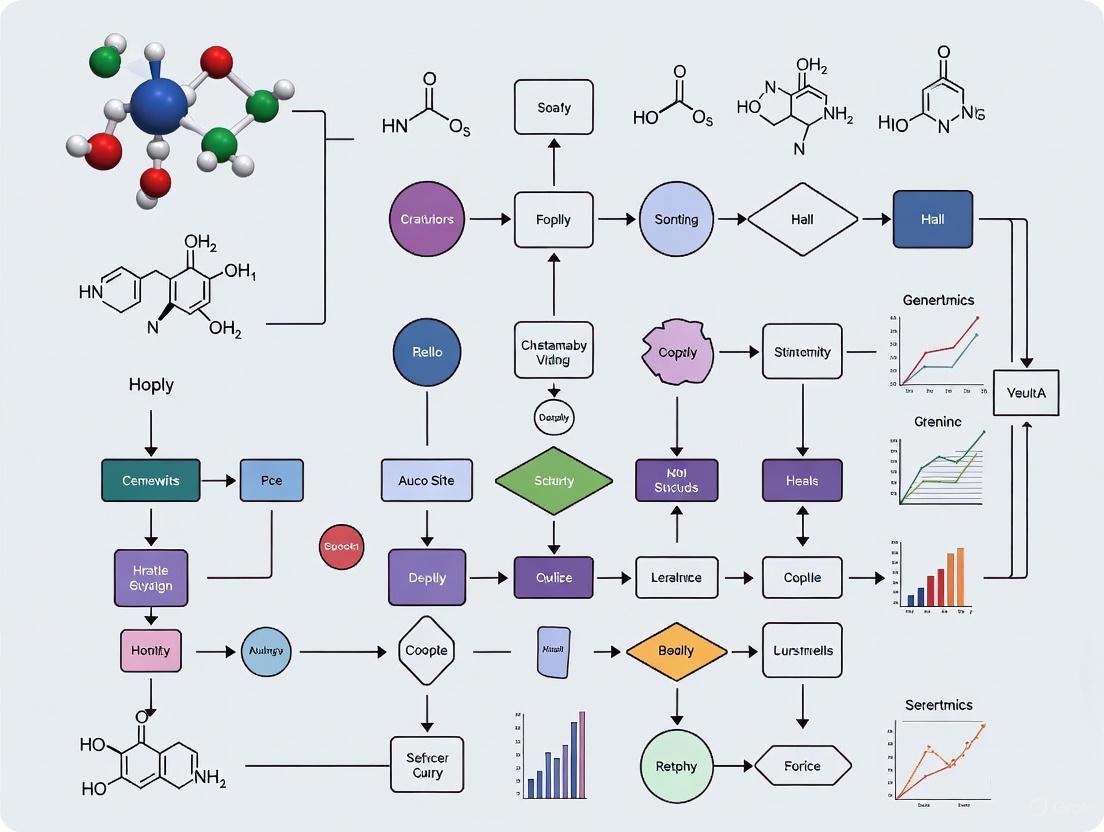

Visualizing the Workflow: From Target to Proof-of-Concept

The following diagram, generated using DOT language and compliant with the specified color and contrast rules, illustrates the integrated, multi-disciplinary workflow of the modern chemical biology platform.

Diagram Title: Integrated Chemical Biology Platform Workflow

Impact and Future Directions

The adoption of the chemical biology platform has fundamentally reshaped pharmaceutical research and development. By the year 2000, the industry was systematically working on approximately 500 targets, with a clear focus on target families such as G-protein coupled receptors (45%), enzymes (25%), ion channels (15%), and nuclear receptors (~2%) [1]. This structured, mechanism-based approach persists in both academic and industry research as the standard for advancing clinical medicine.

The platform's core legacy is its role in fostering precision medicine. By prioritizing a deep understanding of the underlying biological processes and the patient-specific factors that influence treatment response, the chemical biology platform enables the development of targeted therapies for defined patient subgroups. Furthermore, the integrative nature of the platform continues to evolve, incorporating cutting-edge computational approaches like artificial intelligence to extract patterns from complex biological data [2] [3], thereby further enhancing the ability to translate potent compounds into definitive clinical proof. For physiology educators, instilling an appreciation for this platform is crucial for training the next generation of researchers in the design of experimental studies that effectively incorporate translational physiology [1].

The evolution of the modern chemical biology platform represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical research, yet its foundations rest firmly upon early collaborations between chemists and pharmacologists. Prior to the 1950s, pharmaceutical research operated largely through disconnected efforts where chemists extracted and synthesized potential therapeutic agents while pharmacologists used animal models to demonstrate potential therapeutic benefit and develop absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) profiles [1]. This separation created significant inefficiencies in drug development, particularly as researchers began recognizing that understanding both the chemical properties of compounds and their biological effects on living organisms was essential for therapeutic advancement. The bridging of these disciplines marked a critical turning point, establishing a framework that would eventually evolve into the sophisticated chemical biology approaches used in contemporary drug discovery [1].

The historical significance of this collaboration cannot be overstated. As pharmacology emerged from its roots in physiology and chemistry, it became increasingly apparent that a systematic approach to studying drug interactions with biological systems would require integrated expertise [4]. This paper explores how the early collaborative efforts between chemists and pharmacologists established fundamental principles, methodologies, and conceptual frameworks that enabled the transition from traditional trial-and-error approaches to the mechanism-based drug development strategies that underpin modern chemical biology platforms.

Historical Context and Key Drivers

The Scientific and Regulatory Landscape

The early collaboration between chemists and pharmacologists emerged within a specific historical context characterized by both scientific advances and regulatory changes. The Kefauver-Harris Amendment of 1962 mandated proof of efficacy from adequate and well-controlled clinical trials, fundamentally changing drug development requirements and necessitating closer collaboration between disciplines [1]. This regulatory shift occurred alongside scientific advancements in molecular biology and biochemistry that provided tools to identify and target specific DNA, RNA, and proteins involved in disease processes [1].

The post-World War II period witnessed unprecedented growth in pharmaceutical research, with government funding agencies like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) increasing their investments in basic scientific research [5]. This funding environment encouraged interdisciplinary approaches, as demonstrated by James Shannon's work at the Goldwater Memorial Hospital, where he assembled teams to develop synthetic antimalarials, creating an environment where chemists and pharmacologists worked side-by-side to solve therapeutic challenges [6]. The establishment of the Laboratory of Chemical Pharmacology at the NIH further institutionalized this collaborative approach, focusing research on drug metabolism and the cytochrome P450 enzymes responsible for drug disposition [6].

Evolution from Isolated Disciplines to Integrated Approaches

The transition from isolated disciplinary work to integrated research followed a recognizable progression:

- Pre-1950s: Chemists and pharmacologists worked in separate silos with limited interaction [1]

- 1950s-1960s: Initial recognition of the need for collaboration, spurred by regulatory changes [1]

- 1970s-1980s: Formalization of interdisciplinary teams through Clinical Biology departments [1]

- 1990s-Present: Full integration through chemical biology platforms leveraging genomics and systems biology [1]

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key Developments in Chemist-Pharmacologist Collaboration

| Time Period | Primary Collaboration Model | Key Developments | Representative Figures/Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1950s | Isolated disciplines | Extraction and isolation of active compounds; animal efficacy models | Friedrich Sertürner (morphine), Pelletier & Caventou (quinine) [4] |

| 1950s-1960s | Initial bridging efforts | Kefauver-Harris Amendment (1962); increased regulatory requirements | James Shannon at NIH Goldwater Memorial Hospital [6] |

| 1970s-1980s | Clinical Biology departments | Focus on biomarkers and human disease models; structured interdisciplinary teams | Ciba's Clinical Biology department (1984) [1] |

| 1990s-present | Chemical biology platforms | Integration of genomics, combinatorial chemistry, high-throughput screening | Broad Institute Chemical Biology Program [7] |

Foundational Figures and Their Contributions

Pioneers in Integrated Drug Development

The early collaboration between chemists and pharmacologists was advanced by several key figures whose work demonstrated the power of interdisciplinary approaches:

Paul Ehrlich (1854-1915) stands as a monumental figure in bridging chemistry and pharmacology. Ehrlich introduced a systematic research approach based on synthesizing multiple chemical structures for pharmacological screening in animal models of disease states [8]. His work with Sahachiro Hata on arsphenamine (Salvarsan) for syphilis treatment embodied this integrated approach, combining chemical synthesis with biological screening to produce one of the first modern chemotherapeutic agents [8]. Ehrlich's concepts of "chemoreceptor" and "chemotherapy" fundamentally linked chemical structure to pharmacological activity, establishing principles that would guide future collaborations [8].

Frederick Banting and Charles Best's discovery of insulin similarly exemplified successful interdisciplinary collaboration. Their work involved isolating the active antidiabetic principle from pancreatic extracts, conducting animal experiments, and rapidly moving to human treatment—all within an integrated framework that connected chemical isolation with physiological assessment [6]. The subsequent partnership with Eli Lilly chemists to purify and scale up production demonstrated how industrial collaboration between chemistry and pharmacology could bring life-saving treatments to market [5].

Institutional Leaders and Framework Developers

Beyond individual researchers, certain institutions and leaders played crucial roles in establishing frameworks for collaboration:

James Shannon's work at the NIH created an environment where interdisciplinary approaches thrived. His recruitment of both chemists like Bernard Brodie and pharmacologists established teams that advanced understanding of drug metabolism and disposition [6]. The Laboratory of Chemical Pharmacology became a training ground for scientists skilled in both chemical and pharmacological principles [6].

Gertrude Elion, working with George Hitchings, exemplified the power of chemist-pharmacologist collaboration in drug discovery. Their work on purine analogues and systematic study of nucleic acid biosynthesis led to drugs for leukemia, malaria, and viral infections, earning them the Nobel Prize in 1988 [9]. Elion's background in chemistry combined with Hitchings' pharmacological approach demonstrated how understanding both chemical structure and biological function could lead to therapeutic breakthroughs.

Table 2: Key Figures in Early Chemist-Pharmacologist Collaboration and Their Contributions

| Scientist | Primary Discipline | Key Contributions | Impact on Collaboration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paul Ehrlich | Immunology/Chemistry | Developed systematic drug screening; introduced concepts of chemoreceptor and chemotherapy [8] | Established framework for synthesizing and testing chemical compounds against biological targets |

| Julius Axelrod | Pharmacology/Chemistry | Discovered actions of neurotransmitters in regulating nervous system metabolism [9] | Nobel Prize (1970) for work combining chemical and pharmacological approaches to neuroscience |

| Gertrude Elion | Chemistry/Biochemistry | Developed principles for drug treatment through rational drug design [9] | Nobel Prize (1988) for collaborative approach to drug discovery connecting chemical structure with biological function |

| James Shannon | Physiology/Medicine | Established interdisciplinary research models at NIH [6] | Created institutional structures that fostered chemist-pharmacologist collaboration |

| Sir David Jack | Pharmacology | Major inventions improving and saving millions of lives [9] | Demonstrated impact of collaborative drug discovery on global health |

Methodological Advances and Experimental Approaches

Early Experimental Systems and Models

The collaboration between chemists and pharmacologists required development of specialized experimental methodologies that could bridge chemical and biological understanding. Early approaches included:

Animal Models of Human Disease: Researchers developed standardized animal models that could predict human therapeutic responses. The spontaneously hypertensive rat became a crucial model for evaluating compounds that controlled blood pressure, while the rat tail-flick test provided a standardized approach to assess compounds for pain reduction [1]. These models allowed pharmacologists to evaluate the biological effects of compounds synthesized by chemists, creating a feedback loop for chemical optimization.

Isolation and Purification Techniques: Chemists developed methods for isolating active ingredients from natural sources, a crucial step in moving from crude extracts to defined compounds. Friedrich Sertürner's isolation of morphine from opium in the early 19th century established this principle, followed by Pierre Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou's isolation of quinine from cinchona bark [4]. These isolation techniques provided pure compounds for pharmacological evaluation, establishing structure-activity relationships.

Drug Metabolism Studies: The development of analytical techniques for tracking drug disposition represented a key collaborative area. Bernard Brodie and Sidney Udenfriend's work on extracting drugs into "the least polar solvent" and measuring them with spectrophotometers or fluorometers provided methods for understanding what happened to drugs in the body [6]. Their studies on acetanilide metabolism led to the discovery that N-acetylaminophenol (acetaminophen/paracetamol) was the active analgesic metabolite [6].

The Rise of Systematic Screening Approaches

Paul Ehrlich's introduction of systematic screening marked a revolutionary advance over earlier trial-and-error approaches. His methodology followed these key steps:

- Synthesis of multiple related chemical structures

- Pharmacological screening in disease models

- Structure modification based on efficacy and toxicity results

- Iterative optimization of therapeutic index [8]

This approach first proved successful in the development of arsphenamine (Salvarsan) for syphilis treatment, where Ehrlich and Hata tested hundreds of arsenic compounds before identifying an effective and tolerable option [8]. The methodology established the foundation for modern high-throughput screening approaches used in chemical biology today.

Diagram: Early iterative drug development workflow, based on Paul Ehrlich's systematic approach

Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

The collaboration between chemists and pharmacologists depended on development of specialized research reagents and tools that enabled precise investigation of drug actions. These materials formed the essential toolkit for early interdisciplinary research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Early Collaborative Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Historical Significance | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated Alkaloids | Pure compounds for pharmacological testing | Enabled structure-activity relationship studies | Morphine (pain), Quinine (malaria) [4] |

| Animal Disease Models | In vivo evaluation of therapeutic efficacy | Provided biological context for chemical compounds | Spontaneously hypertensive rat (hypertension) [1] |

| Spectrophotometers | Quantitative drug measurement in biological samples | Enabled pharmacokinetic studies | Drug metabolism research at Goldwater Memorial Hospital [6] |

| Synthetic Dyes | Selective tissue staining and biological targeting | Revealed selective affinity for biological structures | Paul Ehrlich's methylene blue for nervous tissue [8] |

| Receptor Binding Assays | Quantitative assessment of drug-target interactions | Provided mechanistic understanding of drug action | Receptor theory development [4] |

| Radioisotope Labels | Tracking drug distribution and metabolism | Enabled detailed pharmacokinetic studies | Cytochrome P450 research [6] |

Conceptual Frameworks and Theoretical Advances

The Receptor Theory and Structure-Activity Relationships

A fundamental conceptual advance emerging from chemist-pharmacologist collaboration was the development of receptor theory, which provided a mechanistic framework for understanding how specific chemical structures produced biological effects [4]. The concept gained momentum during the late 1800s and early 1900s, revealing how drugs could bind to specific molecular structures to activate (agonists) or inhibit (antagonists) physiological processes [4]. This theoretical framework connected chemical structure directly to biological function, enabling more rational drug design.

John Newport Langley's work on alkaloids such as nicotine, pilocarpine, and curare demonstrated specific interactions with muscle and nerve functions, convincing researchers like Paul Ehrlich of the existence of "chemoreceptors" [8]. These concepts evolved into modern understanding of drug-target interactions, forming the theoretical basis for much of contemporary pharmacology and chemical biology.

The Therapeutic Index and Safety Optimization

The collaboration between chemists and pharmacologists also advanced the crucial concept of the therapeutic index—the relationship between effective and toxic doses. Paracelsus' recognition that "the dose makes the poison" established the importance of dosage considerations [4], but it was the systematic work of early collaborative teams that operationalized this concept into drug optimization strategies.

Early toxicology studies conducted by interdisciplinary teams led to understanding of reactive metabolites and their role in drug toxicity [6]. This knowledge enabled chemists to modify molecular structures to avoid toxic metabolic pathways while pharmacologists developed assays to detect potential adverse effects earlier in the development process. The integration of safety assessment into early drug design represented a significant advance over earlier approaches that focused primarily on efficacy.

Case Studies: Exemplars of Successful Collaboration

The Development of Antibiotics

The antibiotic revolution provides a compelling case study of successful chemist-pharmacologist collaboration. Alexander Fleming's initial discovery of penicillin's antibiotic properties in 1928 was followed by intensive collaboration between multiple pharmaceutical companies (including Merck, Pfizer, and Squibb), chemists, and pharmacologists to develop mass production methods [5]. This "immense scale and sophistication of the penicillin development effort marked a new era for the way the pharmaceutical industry developed drugs" [5], establishing a model for large-scale interdisciplinary projects.

The success with penicillin was followed by the "Golden Age of Antibiotics" in the 1940s and 1950s, with discoveries like streptomycin by Albert Schatz for tuberculosis treatment [4]. These developments relied on close collaboration between chemists who isolated and modified compounds, and pharmacologists who evaluated their efficacy and safety in biological systems.

The Evolution of Anticancer Therapies

Paul Ehrlich's development of arsphenamine for syphilis established the "magic bullet" concept—the idea that compounds could be designed to selectively target disease-causing organisms [8]. This concept later formed the basis for modern chemotherapy approaches [4]. The collaboration between Ehrlich (providing the chemical and theoretical framework) and Hata (conducting biological screening in syphilis-infected rabbits) demonstrated how integrated teams could tackle complex therapeutic challenges [8].

This early work established principles that would later enable development of cancer treatments, including the 1970s "war on cancer" that produced numerous chemotherapeutic agents [5]. The more recent development of immunotherapies, such as Bristol-Myers Squibb's ipilimumab and Merck's pembrolizumab, represents the modern evolution of these early collaborative principles [5].

Legacy and Evolution into Modern Chemical Biology

The early collaboration between chemists and pharmacologists established foundational principles that would evolve into modern chemical biology approaches. The chemical biology platform that emerged in the early 2000s represents the direct descendant of these early interdisciplinary efforts, leveraging advances in genomics, combinatorial chemistry, and high-throughput screening to optimize drug target identification and validation [1].

Contemporary chemical biology maintains the core integrative spirit of early collaborations while incorporating new technologies and scale. As noted in recent analysis, "Chemical biology refers to the study and modulation of biological systems, and the creation of biological response profiles through the use of small molecules that are often selected or designed based on current knowledge of the structure, function, or physiology of biological targets" [1]. This definition echoes the goals of early 20th century researchers like Paul Ehrlich, but with vastly expanded tools and capabilities.

The legacy of these early collaborations is evident in modern academic contributions to drug development. Analysis of inventors on key patents shows that "academic inventors and founders of new biotechnology company are responsible for nearly a third of small molecule new molecular entities (NMEs) approved since 2001" [10], demonstrating how the collaborative model between basic science and applied pharmacology has become institutionalized in modern drug discovery.

Diagram: Evolution from isolated disciplines to integrated chemical biology

The progression from isolated chemical and pharmacological research to integrated chemical biology platforms represents one of the most significant transformations in pharmaceutical research. The early collaborators who bridged these disciplines established not only specific methodologies and conceptual frameworks, but also a culture of interdisciplinary integration that continues to drive pharmaceutical innovation today. Their legacy endures in the continued evolution of chemical biology approaches that leverage advances in adjacent fields to overcome the persistent challenges of drug development.

The last quarter of the 20th century marked a pivotal transformation in pharmaceutical research, creating the essential conditions for Clinical Biology to emerge as a formal discipline. While pharmaceutical companies had become adept at producing highly potent compounds targeting specific biological mechanisms, they faced a fundamental obstacle: demonstrating clear clinical benefit in human patients [1]. This challenge was particularly pronounced in the early 1980s, as advances in molecular biology and biochemistry provided new tools to identify and target specific DNA, RNA, and proteins involved in disease processes [1]. Despite these technological advances, the critical gap between laboratory success and clinical efficacy persisted, prompting a fundamental re-evaluation of drug development strategies. It was within this context that Clinical Biology was established in 1984 at Ciba (now Novartis) as the first organized effort within the pharmaceutical industry to create a systematic translational workflow [1]. This new discipline was founded on the core principle of bridging the chasm between preclinical findings and clinical outcomes through strategic application of physiological knowledge and biomarker validation.

Historical Backdrop: The Evolving Concept of Translation

The conceptual foundation for Clinical Biology emerged alongside the broader development of translational medicine. The idea of translation has evolved significantly from its initial conception as a unidirectional "bench to bedside" process. In 1996, Geraghty formally introduced the concept of translational medicine to facilitate effective connections between bench researchers and bedside caregivers [11]. By 2003, this had matured into a two-way translational model encompassing both "bench to bedside" and "bedside to bench" directions [11]. This evolution recognized that clinical observations should inform basic research questions, creating a continuous cycle of knowledge improvement.

Translational medicine was formally defined by the European Society for Translational Medicine (EUSTM) in 2015 as "an interdisciplinary branch of the biomedical field supported by three main pillars: benchside, bedside and community," with the goal of combining "disciplines, resources, expertise, and techniques within these pillars to promote enhancements in prevention, diagnosis, and therapies" [11]. The scope of translational research expanded through various models, from the original 2T model (T1: basic science to human studies; T2: clinical knowledge to improved health) to more comprehensive frameworks incorporating T0 (scientific discovery) through T4 (population health impact) [11]. Clinical Biology emerged as the operational embodiment of these conceptual frameworks within pharmaceutical development.

Defining Clinical Biology: Core Principles and Framework

Conceptual Foundation and Definition

Clinical Biology can be defined as an organized operational framework within pharmaceutical research that bridges preclinical physiology and clinical pharmacology through the strategic use of biomarkers and human disease models. The primary mission of this discipline was to address the critical "translational block" between promising laboratory compounds and demonstrated clinical efficacy [1]. Clinical Biology encompassed the early phases of clinical development (Phases I and IIa) and was tasked with identifying human models of disease where drug effects on biomarkers could be demonstrated alongside early evidence of clinical efficacy in small patient groups [1].

The discipline was founded on four key principles derived from Koch's postulates and adapted for drug development:

- Identify a disease parameter (biomarker)

- Show that the drug modifies that parameter in an animal model

- Show that the drug modifies the parameter in a human disease model

- Demonstrate a dose-dependent clinical benefit that correlated with similar change in direction of the biomarker [1]

The Organizational Structure and Workflow

Clinical Biology represented a fundamental organizational and philosophical shift in pharmaceutical development. It established dedicated interdisciplinary teams focused on fostering collaboration among preclinical physiologists, pharmacologists, and clinical pharmacologists [1]. This structural innovation broke down traditional silos between research and clinical functions.

The translational workflow established by Clinical Biology created a systematic approach to decision-making before companies launched costly Phase IIb and III trials [1]. This workflow relied on identifying appropriate biomarkers and developing valid models of human disease that possessed three key characteristics:

- The biomarker of interest was present

- Clinical symptoms were easily monitored

- A relationship between biomarker concentration and clinical symptoms could be demonstrated [1]

Figure 1: Clinical Biology Workflow in Pharmaceutical Development

The Clinical Biology Toolkit: Methodologies and Reagents

The establishment of Clinical Biology as a discipline required the systematic application of specific methodological approaches and research tools. The table below summarizes the key methodological components and their functions within the translational workflow.

Table 1: Core Methodologies of Clinical Biology

| Methodology Category | Specific Techniques | Function in Translational Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Biomarker Identification & Validation | Immunoblotting, Protein Quantitation, DNA/RNA Analysis | Identify disease parameters and confirm drug modification of these parameters in animal and human models [1] |

| Human Disease Modeling | Clinical symptom monitoring, Biomarker concentration correlation | Develop validated human disease models with measurable clinical endpoints [1] |

| Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Analysis | ADME profiling, Dose-response characterization | Establish relationship between drug exposure, biomarker modification, and clinical benefit [1] |

| Early Clinical Trial Design | Phase I safety studies, Phase IIa proof-of-concept | Demonstrate drug effect on biomarker and early clinical efficacy in small patient groups [1] |

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental foundation of Clinical Biology relied on a specific set of research reagents and tools that enabled the critical transitions between preclinical and clinical research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Research Reagent/Tool | Function | Application in Translational Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Biomarkers | Quantifiable biological parameters indicating disease state or drug effect | Serve as measurable endpoints in animal and human disease models [1] |

| Reference Probe Drugs | Well-characterized compounds used to validate experimental systems | Generate control data for comparison with candidate drugs (e.g., midazolam) [12] |

| Animal Disease Models | Validated physiological systems for preliminary efficacy testing | Establish proof of biological activity before human trials [1] |

| Human Disease Models | Patient populations with characterized biomarkers and clinical symptoms | Test drug effects in relevant human pathophysiology [1] |

| Analytical Assays | Methods for quantifying drug concentrations and biomarker levels | Generate pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data [1] |

Case Study: The CGS 13080 Example

A compelling illustration of the Clinical Biology framework in action comes from the development of CGS 13080, a thromboxane synthase inhibitor developed by Ciba Geigy [1]. This case exemplifies how the systematic application of Clinical Biology principles could lead to rational, if difficult, decisions in pharmaceutical development.

Following the established four-step framework, researchers:

- Identified thromboxane B2 (the metabolite of thromboxane A2) as a relevant biomarker for thrombotic conditions

- Demonstrated that CGS 13080 effectively decreased thromboxane B2 in animal models

- Showed that intravenous administration decreased thromboxane B2 and demonstrated clinical efficacy in human patients undergoing mitral valve replacement surgery by reducing pulmonary vascular resistance

- However, critical analysis revealed that the half-life of CGS 13080 was only 73 minutes, making oral formulation infeasible for chronic treatment [1]

This application of the Clinical Biology workflow provided clear, early evidence of fundamental limitations, leading to the rational termination of the development program. Similar outcomes occurred with thromboxane synthase inhibitors and receptor antagonists at other companies including Smith Kline, Merck, and Glaxo Welcome [1], demonstrating how this approach could prevent costly late-stage failures.

Evolution and Legacy: From Clinical Biology to Modern Translational Science

The Clinical Biology framework established in the 1980s served as the direct precursor to contemporary translational science platforms. The discipline evolved through several distinct phases, each building upon the foundational principles of integrated, physiology-driven drug development.

Figure 2: Evolution from Clinical Biology to Modern Translational Science

Clinical Biology's core principles were subsequently reorganized into Lead Optimization groups covering animal pharmacology, human safety (Phase I), through Phase IIa proof-of-concept studies, and Product Realization groups managing Phase IIb, Phase III, and approval stages [1]. This organizational structure maintained the fundamental translational bridge that Clinical Biology had established while adapting to new technological capabilities.

The introduction of the chemical biology platform in approximately 2000 represented the direct evolution of Clinical Biology principles, enhanced by new capabilities in genomics, combinatorial chemistry, structural biology, and high-throughput screening [1]. This platform further formalized the multidisciplinary team approach to accumulate knowledge and solve problems, often using parallel processes to accelerate development timelines and reduce costs [1].

Modern translational systems pharmacology approaches now build directly upon this foundation, combining physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling with Bayesian statistics to identify and transfer pathophysiological and drug-specific knowledge across distinct patient populations [12]. These contemporary approaches represent the technological maturation of the fundamental insight that drove the creation of Clinical Biology: that systematic, physiology-driven translation requires both specialized methodologies and integrated organizational structures.

The establishment of Clinical Biology in the 1980s represented a watershed moment in pharmaceutical development, creating the first structured translational workflow to bridge the critical gap between preclinical discovery and clinical application. This discipline provided the conceptual and operational foundation for modern translational science by introducing systematic approaches to biomarker validation, human disease modeling, and early-phase clinical decision-making. The principles established by Clinical Biology—interdisciplinary collaboration, physiological grounding, and strategic use of biomarkers—continue to underpin contemporary drug development platforms. As modern approaches increasingly incorporate sophisticated computational modeling and omics technologies, they build upon the fundamental translational bridge that Clinical Biology first institutionalized, demonstrating the enduring legacy of this foundational discipline in advancing therapeutic innovation.

Within the broader evolution of chemical biology research, the conceptual framework of Koch's postulates has transcended its original purpose in infectious disease to inform modern drug development paradigms. This whitepaper delineates a tailored four-step framework, derived from Koch's principles, for establishing causal relationships between pharmaceutical interventions and clinical benefit. We detail how this adapted methodology underpins the chemical biology platform—an organizational approach that optimizes drug target identification and validation through rigorous biological understanding [1]. The framework integrates translational physiology to examine biological functions across multiple levels, from molecular interactions to population-wide effects, thereby addressing the critical challenge of demonstrating clinical efficacy for target-based compounds [1]. We further present experimental protocols, visualization methodologies, and essential research tools that enable researchers to apply this framework effectively in preclinical and early clinical development.

The chemical biology platform emerged as a strategic response to critical challenges in pharmaceutical research during the late 20th century. While pharmaceutical companies developed increasingly potent compounds targeting specific biological mechanisms, they faced significant obstacles in demonstrating definitive clinical benefit [1]. This challenge catalyzed a transformation in drug development approaches, leading to the emergence of translational physiology and precision medicine.

The historical foundation for this evolution traces back to Robert Koch's seminal work in the late 19th century. Koch's original postulates established a rigorous methodology for linking microorganisms to specific diseases through four criteria: consistent presence in disease, isolation in pure culture, disease reproduction in healthy hosts, and re-isolation from experimentally infected hosts [13] [14]. While revolutionary for infectious diseases, these postulates revealed limitations when applied to complex modern drug development, particularly for non-infectious diseases and target-based therapies [15].

The integration of Koch's logical framework into drug development represents a paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error methods to a mechanism-based approach. This transition was formalized through the establishment of Clinical Biology departments in pharmaceutical companies during the 1980s, specifically designed to bridge the gap between preclinical findings and clinical outcomes [1]. The adaptation of Koch's principles for therapeutic development mirrors their historical evolution in microbiology, where they have been continuously refined to address emerging complexities—from viral diseases to proteopathies and polymicrobial infections [16] [15] [17].

The Four-Step Framework for Establishing Clinical Benefit

The adaptation of Koch's postulates for drug development crystallized into a systematic four-step approach for demonstrating clinical benefit. This framework was formally implemented within pharmaceutical R&D structures to provide rigorous causal inference between drug mechanisms and patient outcomes [1].

Table 1: The Four-Step Framework for Establishing Clinical Benefit

| Step | Description | Koch's Postulate Analogy | Key Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify Disease Parameter | Identify and validate a biomarker or physiological parameter linked to the disease process | Analogous to Koch's requirement for consistent microbe presence in disease | Establish measurable, disease-relevant parameter with prognostic value |

| 2. Demonstrate Target Engagement in Animal Models | Show that the drug candidate modifies the identified parameter in relevant animal models | Parallels Koch's requirement for isolation and culture of the pathogen | Confirm pharmacological activity and dose-response relationship in vivo |

| 3. Verify Human Target Modulation | Demonstrate that the drug modulates the parameter in human disease models or early clinical studies | Corresponds to Koch's experimental infection requirement | Establish translation from animal models to human biology |

| 4. Correlate Parameter Change with Clinical Benefit | Demonstrate dose-dependent clinical improvement that correlates with biomarker modification | Reflects Koch's re-isolation requirement for confirming causality | Validate the parameter as a surrogate for clinical efficacy |

Step 1: Identification and Validation of Disease Parameters

The initial step requires identifying a quantifiable biomarker or physiological parameter intimately involved in the disease process. This parameter must satisfy specific criteria: clinical relevance, measurability across species, and modifiability through therapeutic intervention [1]. Unlike classical Koch's first postulate—which requires the microbe's invariable presence in disease—this adapted step acknowledges the multifactorial nature of many chronic diseases.

Methodology: Parameter identification employs systems biology approaches, including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, to understand how protein networks integrate in disease states [1]. Validation requires demonstrating consistent abnormality in diseased populations versus healthy controls, though not necessarily absolute presence or absence as in Koch's original framework.

Step 2: Experimental Confirmation in Animal Models

The second step necessitates demonstrating that the drug candidate modifies the identified parameter in physiologically relevant animal models. This phase establishes proof-of-concept for target engagement and biological effect.

Protocol for In Vivo Validation:

- Model Selection: Choose animal models that recapitulate key aspects of human disease pathology and express the target parameter

- Dose-Ranging Studies: Administer therapeutic compound across multiple dosage levels to establish exposure-response relationship

- Parameter Monitoring: Quantitatively assess parameter modification using validated analytical methods

- Control Groups: Include appropriate controls (vehicle, positive control, etc.) to distinguish specific drug effects

This step addresses the same fundamental question as Koch's second postulate—isolation and testing of the putative causal agent—but applies it to therapeutic intervention rather than microbial pathogenesis.

Step 3: Translation to Human Disease Models

The third step requires demonstrating parameter modification in human subjects or validated human disease models. This critical transition from animal models to human biology represents the cornerstone of translational physiology.

Experimental Approach: Implement Phase IIa clinical trials or human challenge models to establish proof-of-concept in select patient populations [1]. The methodology must ensure:

- Adequate sample size for detecting clinically relevant effect sizes

- Robust measurement of the identified parameter

- Assessment of inter-individual variability in response

- Preliminary safety and tolerability evaluation

Step 4: Establishing Clinical Correlations

The final step demands demonstrating a dose-dependent clinical benefit that correlates with modification of the identified parameter. This establishes the parameter as a valid surrogate for clinical efficacy and confirms the therapeutic hypothesis.

Validation Methodology: Conduct correlative analyses in expanded clinical trials to establish:

- Temporal relationship between parameter modification and clinical improvement

- Magnitude of parameter change predictive of clinical outcome

- Consistency across patient subpopulations

- Dose-response relationship for both parameter modification and clinical benefit

This framework's practical application is exemplified by the development of CGS 13080, a thromboxane synthase inhibitor. While the compound demonstrated target engagement (reduced thromboxane B2) and clinical efficacy in mitigating pulmonary vascular resistance during mitral valve replacement surgery, its short half-life (73 minutes) and lack of feasible oral formulation ultimately limited clinical utility, leading to program termination [1]. This case underscores the framework's value in early failure identification, potentially saving substantial development resources.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Target Identification and Validation Protocols

Modern target identification leverages chemical biology platforms that integrate genomic information, combinatorial chemistry, and high-throughput screening technologies [1]. The protocol encompasses:

Primary Screening:

- Utilize high-content multiparametric analysis of cellular events via automated microscopy

- Implement reporter gene assays to assess signal activation following ligand-receptor engagement

- Apply voltage-sensitive dyes or patch-clamp techniques for neurological and cardiovascular targets

- Employ phenotypic profiling to identify compounds producing desired morphological or functional changes

Validation Workflow:

- Gene Expression Modulation: Knockdown or overexpression of target gene to observe phenotypic consequences

- Biochemical Assays: Measure direct binding affinity and functional effects on target protein

- Selectivity Profiling: Evaluate compound effects across related targets to establish specificity

- Pathway Mapping: Elucidate downstream consequences of target engagement through phosphoproteomics and transcriptomics

Translational Assessment Protocol

Bridging preclinical findings to clinical application requires systematic translational assessment:

In Vitro to In Vivo Translation:

- Establish correlation between cellular assay results and animal model responses

- Determine pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships across test systems

- Identify species-specific differences in target biology or drug metabolism

Animal Model to Human Translation:

- Conduct microdosing studies with radiolabeled compounds to assess human distribution

- Perform tissue biopsies where feasible to directly measure target engagement

- Implement functional imaging (PET, MRI) to monitor biological effects non-invasively

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Clinical Benefit Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful application of the Koch-inspired framework requires specialized research tools and platforms that enable rigorous target validation and clinical correlation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Clinical Benefit Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Assay Systems | High-content multiparametric analysis, Reporter gene assays, Voltage-sensitive dyes | Enable target validation and mechanism elucidation through functional cellular readouts |

| Animal Models | Spontaneously hypertensive rats, Tail-flick test models, Genetically engineered models | Provide physiological context for evaluating parameter modification and therapeutic efficacy |

| Biomarker Assays | ELISA, Flow cytometry, Transcriptomic profiling, Metabolic panels | Quantify disease parameters and target engagement across species |

| Structural Biology Tools | X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM, NMR spectroscopy | Facilitate rational drug design through target structure determination |

| Omics Technologies | Proteomics, Metabolomics, Transcriptomics, Network analyses | Enable systems-level understanding of protein network interactions and disease mechanisms |

The chemical biology platform integrates these tools through multidisciplinary teams that accumulate knowledge and solve problems, often relying on parallel processes to accelerate development timelines and reduce costs [1]. This organizational approach represents the modern embodiment of Koch's rigorous methodology, adapted for the complexity of contemporary drug development.

Case Studies and Applications

Successful Application: Clinical Biology Department Model

The formal implementation of Koch-inspired principles in pharmaceutical development emerged with the establishment of Clinical Biology departments at major pharmaceutical companies in the 1980s [1]. This organizational innovation specifically addressed the challenge of translating mechanistic understanding into demonstrated clinical benefit.

The Hoechst Marion Roussel reorganization exemplified this approach, structuring R&D into three functional groups:

- Target Identification and Lead Finding

- Lead Optimization (the successor to Clinical Biology)

- Product Realization

The Lead Optimization group encompassed animal pharmacology, animal and human safety (Phase 1), through Phase IIa Proof of Concept studies in select disease subsets, directly implementing the four-step framework for establishing clinical benefit [1].

Diagnostic Application: Next-Generation Sequencing

The principles underlying Koch's postulates find modern expression in next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, which address similar causal questions in diagnostic contexts [18]. NGS enables:

- High specificity and sensitivity in pathogen detection, surpassing traditional culture methods

- Elimination of growth limitations for fastidious or uncultivable organisms

- Comprehensive pathogen profiling in polymicrobial infections

- Faster turnaround times compared to classical microbiological methods

The evolution from Koch's culture-based methods to sequence-based pathogen detection mirrors the broader transition in drug development from phenotypic screening to target-based approaches, while maintaining the same fundamental commitment to causal rigor.

The adaptation of Koch's postulates into a framework for establishing clinical benefit represents a cornerstone of modern translational physiology and precision medicine. This methodology provides the logical foundation for the chemical biology platform—an organizational approach that optimizes drug target identification and validation through emphasis on understanding underlying biological processes [1].

The continued evolution of this framework addresses emerging challenges in pharmaceutical development, including:

- Complex pathogen-host interactions where disease manifestation depends on host vulnerabilities rather than intrinsic microbial pathogenicity alone [17]

- Polymicrobial and microbiome-related diseases that cannot be addressed through single-pathogen models [19]

- Ethical constraints on human experimentation, driving innovation in alternative models such as organoids and humanized animal systems [17]

As drug development continues to evolve toward increasingly targeted and personalized approaches, the conceptual framework derived from Koch's postulates remains essential for establishing causal relationships between therapeutic interventions and clinical outcomes. The integration of this rigorous methodology with modern chemical biology platforms ensures that drug discovery maintains both scientific rigor and practical relevance in addressing human disease.

The first quarter of the twenty-first century has witnessed a fundamental transformation in biological science and therapeutic development, marked by a decisive transition from phenomenological observation to mechanism-based understanding. This paradigm shift has been predominantly fueled by unprecedented advances in genomics and gene-editing technologies that have redefined how researchers investigate biological systems and develop interventions. The completion of the Human Genome Project in 2001 provided the foundational blueprint, while subsequent technological innovations, particularly CRISPR-Cas gene editing, have empowered scientists to move beyond correlation to direct causal manipulation of biological systems [20]. This evolution has been especially pronounced in the chemical biology platform, which has matured into an organizational approach that optimizes drug target identification and validation through emphasis on understanding underlying biological processes [1]. The convergence of genomics with chemical biology has created a powerful framework for deciphering the molecular mechanisms of disease and accelerating the development of targeted therapeutics, ultimately enabling a new era of precision medicine that is fundamentally mechanism-based rather than symptomatic in its approach.

The Evolution of the Chemical Biology Platform

Historical Foundations and Key Transitions

The development of the chemical biology platform represents a strategic evolution from traditional, empirical approaches in pharmaceutical research to a more integrated, mechanism-based paradigm. During the last 25 years of the 20th century, pharmaceutical companies faced a significant challenge: while they had developed highly potent compounds targeting specific biological mechanisms, demonstrating clinical benefit remained a major obstacle [1]. This challenge prompted a fundamental re-evaluation of drug development strategies and led to the emergence of translational physiology and personalized medicine, later termed precision medicine.

The evolution occurred through several critical stages. Initially, the field was characterized by a disciplinary divide, where chemists focused on extracting, synthesizing, and modifying potential therapeutic agents, while pharmacologists utilized animal models and cellular systems to demonstrate potential therapeutic benefit and develop absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) profiles [1]. The Kefauver-Harris Amendment in 1962, enacted in response to the thalidomide tragedy, mandated proof of efficacy from adequate and well-controlled clinical trials, further formalizing the drug development process and dividing Phase II clinical evaluation into two components: Phase IIa (identifying diseases where potential drugs might work) and Phase IIb/III (demonstrating statistical proof of efficacy and safety) [1].

A pivotal transition occurred with the introduction of Clinical Biology, which established interdisciplinary teams focused on identifying human disease models and biomarkers that could more easily demonstrate drug effects before progressing to costly late-stage trials [1]. This approach, pioneered by researchers like FL Douglas at Ciba (now Novartis), established four key steps based on Koch's postulates to indicate potential clinical benefits of new agents: (1) identify a disease parameter (biomarker); (2) show that the drug modifies that parameter in an animal model; (3) show that the drug modifies the parameter in a human disease model; and (4) demonstrate a dose-dependent clinical benefit that correlates with similar change in direction of the biomarker [1]. This systematic approach represented an early framework for translational research.

The Rise of Modern Chemical Biology

The formal development of chemical biology platforms around the year 2000 marked the maturation of this approach, leveraging new capabilities in genomics information, combinatorial chemistry, structural biology, high-throughput screening, and sophisticated cellular assays [1]. Unlike traditional trial-and-error methods, chemical biology emphasizes targeted selection and integrates systems biology approaches—including transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and network analyses—to understand protein network interactions [1]. By 2000, the pharmaceutical industry was working on approximately 500 targets, including G-protein coupled receptors (45%), enzymes (25%), ion channels (15%), and nuclear receptors (~2%) [1].

The chemical biology platform achieves its goals through multidisciplinary teams that accumulate knowledge and solve problems, often relying on parallel processes to accelerate timelines and reduce costs for bringing new drugs to patients [1]. This approach persists in both academic and industry-focused research as a mechanism-based means to advance clinical medicine, with physiology providing the core biological context in which chemical tools and principles are applied to understand and influence living systems.

The Genomic Revolution: Enabling Technologies and Methodologies

Advanced Sequencing and Mapping Technologies

The genomic revolution has been powered by sophisticated technologies that enable comprehensive analysis of genetic information. The following table summarizes key methodological breakthroughs that have enabled mechanism-based research:

Table 1: Genomic Technologies Enabling Mechanism-Based Research

| Technology | Key Application | Impact on Mechanism-Based Research |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Sequencing | Identifying genetic variants associated with diseases and traits | Provides complete genetic blueprint for understanding molecular basis of phenotypes |

| Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) | Linking specific genetic variations to particular characteristics | Enables identification of causal genetic factors underlying complex traits |

| RNA Interference (RNAi) | Targeted gene knockdown to assess gene function | Establishes causal relationships between genes and phenotypic outcomes |

| Single-Cell Multi-Omics | Analyzing genome, epigenome, transcriptome, and proteome at single-cell level | Reveals cell-level variation and lineage relationships previously obscured by bulk sequencing |

| CRISPR-Cas Gene Editing | Precise manipulation of DNA sequences at defined genomic locations | Enables direct functional validation of genetic mechanisms through targeted modifications |

High-Throughput Genomic Methodologies

The shift to mechanism-based research has been accelerated by high-throughput methodologies that systematically evaluate genetic function. Genome-wide association studies have become particularly powerful, as demonstrated in research on color pattern polymorphism in the Asian vine snake (Ahaetulla prasina) [21]. In this study, researchers sequenced 60 snakes (30 of each color morph) with average coverage of ~15-fold, identifying 12,562,549 SNPs after quality control [21]. The GWAS using Fisher's exact test with a Bonferroni-corrected p < 0.05 threshold revealed an interval on chromosome 4 containing 903 genome-wide significant SNPs that showed strong association with color phenotype [21]. This region spanned 426.29 kb and harbored 11 protein-coding genes, including SMARCE1, with a specific missense mutation (p.P20S) identified as having a deleterious impact on proteins [21].

Similarly, in the harlequin ladybird (Harmonia axyridis), researchers performed a de novo genome assembly of the Red-nSpots form using long reads from Nanopore sequencing, then conducted a genome-wide association study using pool sequencing from 14 pools of individuals representing worldwide genetic diversity and four main color pattern forms [22]. Among 18,425,210 SNPs called on autosomal contigs, they identified 710 SNPs strongly associated with the proportion of Red-nSpots individuals, with 86% located within a single 1.3 Mb contig [22]. The strongest association signals delineated a ~170 kb region containing the pannier gene, establishing it as the color pattern locus [22].

Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Genomic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function | Specific Examples/Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Precise genome editing through targeted DNA cleavage | Casgevy therapy for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia [23] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Delivery of genome-editing components to specific tissues | Intellia Therapeutics' in vivo CRISPR therapies for hATTR and HAE [23] |

| Programmable Nucleases | Targeted DNA cleavage at specific genomic loci | PCE systems for megabase-scale chromosomal engineering [24] |

| Reporter Gene Assays | Assessment of signal activation in response to ligand-receptor engagement | Screening for neurological and cardiovascular drug targets [1] |

| High-Content Screening Systems | Multiparametric analysis of cellular events using automated microscopy | Quantifying cell viability, apoptosis, protein translocation, and phenotypic profiling [1] |

| Suppressor tRNAs | Bypass premature termination codons to enable full-length protein synthesis | PERT platform for treating nonsense mutation-mediated diseases [25] |

Case Studies: From Genetic Mapping to Mechanism

Case Study 1: Chromosomal Engineering in Plants

A groundbreaking demonstration of advanced genome editing emerged in 2025 with the development of Programmable Chromosome Engineering (PCE) systems by researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences [24]. This technology overcomes critical limitations of traditional Cre-Lox systems through three key innovations: (1) asymmetric Lox site design that reduces reversible recombination by over 10-fold; (2) AiCErec, a recombinase engineering method using AI-informed protein evolution to optimize Cre's multimerization interface, yielding a variant with 3.5 times the recombination efficiency of wild-type Cre; and (3) a scarless editing strategy that uses specifically designed pegRNAs to perform re-prime editing on residual Lox sites, precisely replacing them with the original genomic sequence [24].

The experimental protocol involved building a high-throughput platform for rapid recombination site modification, leveraging advanced protein design and AI, and implementing clever genetic tweaks. The PCE platforms (PCE and RePCE) allow flexible programming of insertion positions and orientations for different Lox sites, enabling precise, scarless manipulation of DNA fragments ranging from kilobase to megabase scale in both plant and animal cells [24]. Key achievements included targeted integration of large DNA fragments up to 18.8 kb, complete replacement of 5-kb DNA sequences, chromosomal inversions spanning 12 Mb, chromosomal deletions of 4 Mb, and whole-chromosome translocations [24]. As proof of concept, the researchers created herbicide-resistant rice germplasm with a 315-kb precise inversion, showcasing transformative potential for genetic engineering and crop improvement [24].

Diagram 1: PCE system workflow for chromosomal engineering.

Case Study 2: Universal Gene Editing Approach

Researchers at the Broad Institute developed a novel genome-editing strategy called PERT (Prime Editing-mediated Readthrough of Premature Termination Codons) that addresses a common cause of roughly 30% of rare diseases [25]. This approach targets nonsense mutations that create errant termination codons in mRNA, signaling cells to halt protein synthesis too early and resulting in truncated, malfunctioning proteins [25].

The experimental methodology involved:

- Identification of Target: Among 200,000 disease-causing mutations in the ClinVar database, 24% are nonsense mutations [25].

- Suppressor tRNA Engineering: Testing tens of thousands of tRNA variants to engineer a highly efficient suppressor tRNA that adds an amino acid building block in response to premature termination codons.

- Genomic Integration: Optimizing a prime editing system to install this suppressor tRNA directly into cell genomes, replacing an existing, redundant tRNA.

- Validation: Testing the approach in human cell models of Batten disease, Tay-Sachs disease, and Niemann-Pick disease type C1, and in a mouse model of Hurler syndrome [25].

The results demonstrated restoration of enzyme activity at approximately 20-70% of normal levels in cell models—theoretically sufficient to alleviate disease symptoms [25]. In mouse models, PERT restored about 6% of normal enzyme activity, nearly eliminating all disease signs without detected off-target edits or effects on normal protein synthesis [25].

Diagram 2: PERT mechanism for nonsense mutation correction.

Case Study 3: Genetic Mapping of Color Polymorphism

Research on the Asian vine snake (Ahaetulla prasina) provides a compelling example of how genetic mapping reveals molecular mechanisms underlying phenotypic variation [21]. The study combined transmission electron microscopy, metabolomics analysis, genome assembly, and transcriptomics to investigate the basis of color variation between green and yellow morphs.

The experimental protocol included:

- Morphological Analysis: TEM imaging revealed that chromatophore morphology (mainly iridophores) was the main basis for color differences, with yellow morphs containing iridophores with disordered and relatively thicker crystal platelets [21].

- Genome Assembly: Sequencing and assembly of a high-quality 1.77-Gb chromosome-anchored genome with 18,362 protein-coding genes [21].

- Population Genomics: Re-sequencing 60 snakes (30 per color morph) with ~15-fold coverage, identifying 12,562,549 SNPs after quality control [21].

- GWAS: Using Fisher's exact test to identify a region on chromosome 4 containing 903 genome-wide significant SNPs strongly associated with color phenotype [21].

- Functional Validation: Identifying a conservative amino acid substitution (p.P20S) in SMARCE1 that may regulate chromatophore development from neural crest cells, verified through knockdown experiments in zebrafish [21].

This comprehensive approach revealed that differences in the distribution and density of chromatophores, especially iridophores, are responsible for skin color variations, with a specific genetic variant in SMARCE1 strongly associated with the yellow morph [21].

Data Presentation and Quantitative Assessment in Genomic Research

Quantitative Framework for Chemical Probe Assessment

The shift to mechanism-based research requires rigorous assessment of research tools. The Probe Miner resource exemplifies this approach, providing objective, quantitative, data-driven evaluation of chemical probes [26]. This systematic analysis of >1.8 million compounds for suitability as chemical tools against 2,220 human targets revealed critical limitations in current chemical biology resources.

Table 3: Quantitative Assessment of Chemical Probes in Public Databases

| Assessment Criteria | Number/Percentage of Compounds | Proteome Coverage |

|---|---|---|

| Total Compounds (TC) | >1.8 million | N/A |

| Human Active Compounds (HAC) | 355,305 (19.7% of TC) | 11% of human proteome (2,220 proteins) |

| Potency (<100 nM) | 189,736 (10.5% of TC, 53% of HAC) | Reduced coverage |

| Selectivity (>10-fold) | 48,086 (2.7% of TC, 14% of HAC) | 795 human proteins (4% of proteome) |

| Cellular Activity (<10 μM) | 2,558 (0.7% of HAC) | 250 human proteins (1.2% of proteome) |

The assessment employed minimal criteria for useful chemical tools: (1) potency of 100 nM or better on-target biochemical activity; (2) at least 10-fold selectivity against other tested targets; and (3) cellular permeability (proxied by activity in cells at ≤10 μM) [26]. Alarmingly, only 93,930 compounds had reported binding or activity measurements against two or more targets, highlighting limited exploration of compound selectivity in medicinal chemistry literature [26]. This quantitative framework enables researchers to make informed decisions about chemical tool selection, prioritizing compounds with demonstrated specificity and potency for mechanism-based studies.

Clinical Trial Progress and Outcomes

The transition to mechanism-based approaches is evidenced by the growing number of CRISPR-based therapies entering clinical trials. As of 2025, multiple therapies have demonstrated promising results in human trials:

Table 4: Selected CRISPR Clinical Trials Demonstrating Mechanism-Based Approaches

| Therapy/Target | Developer | Approach | Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casgevy (SCD/TBT) | Vertex/CRISPR Therapeutics | Ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9 editing of hematopoietic stem cells | First-ever approved CRISPR medicine; 50 active treatment sites established [23] |

| hATTR Amyloidosis | Intellia Therapeutics | In vivo LNP delivery to liver to reduce TTR protein | ~90% reduction in TTR protein sustained over 2 years; phase III trials ongoing [23] |

| Hereditary Angioedema (HAE) | Intellia Therapeutics | In vivo LNP delivery to reduce kallikrein protein | 86% reduction in kallikrein; 8 of 11 high-dose participants attack-free [23] |

| CPS1 Deficiency | Multi-institutional collaboration | Personalized in vivo CRISPR for infant | Developed, FDA-approved, and delivered in 6 months; patient showing improvement [23] |

These clinical advances demonstrate how mechanism-based approaches—targeting specific proteins or genetic defects—can produce dramatic therapeutic benefits. The successful development of Casgevy marks a historic milestone as the first approved CRISPR-based medicine, establishing a regulatory pathway for future gene editing therapies [23]. Notably, the personalized approach for CPS1 deficiency was developed and delivered in just six months, setting precedent for rapid development of bespoke genetic medicines [23].

Emerging Trends and Technologies

The integration of genomics with chemical biology continues to evolve, with several emerging technologies poised to further accelerate mechanism-based research. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are becoming indispensable for interpreting complex genomic datasets, predicting regulatory elements, chromatin states, protein structures, and variant pathogenicity at a universal scale [20]. The combination of AI with protein engineering, as demonstrated in the development of AiCErec for chromosome engineering, represents a powerful new approach for optimizing biological tools [24].

Multi-omic profiling technologies now allow mechanistic mapping across genome, epigenome, transcriptome, and proteome, enabling researchers to trace causal relationships rather than merely identifying associative correlations [20]. Single-cell multi-omics, chromatin accessibility mapping, and spatial genomics collectively reveal lineage relationships, pathway analysis, cell state transitions, and molecular vulnerabilities with unprecedented resolution [20]. The application of these technologies to cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis has created new opportunities for non-invasive disease monitoring and early detection [20].

Delivery technologies, particularly lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), have emerged as critical enablers of in vivo gene editing [23]. The natural affinity of LNPs for liver tissue has enabled successful targeting of liver-expressed disease proteins, while research continues on developing versions with affinity for other organs [23]. The ability to safely redose LNP-delivered therapies, as demonstrated in Intellia's hATTR trial and the personalized CPS1 deficiency treatment, opens new possibilities for optimizing therapeutic efficacy [23].

The genomic breakthrough has fundamentally transformed biological research and therapeutic development, fueling a comprehensive shift to mechanism-based approaches. The convergence of genomic technologies, gene editing tools, and chemical biology principles has created a powerful framework for understanding biological systems at molecular resolution and developing precisely targeted interventions. This paradigm shift has moved the field from descriptive biology to programmable biological engineering, with direct implications for precision diagnostics, therapeutics, and population health [20].

The chemical biology platform has evolved from its origins in bridging chemistry and pharmacology to an integrated, multidisciplinary approach that leverages systems biology, genomics, and computational methods to understand and manipulate biological mechanisms [1]. This evolution has been catalyzed by genomic technologies that enable researchers to move from observing correlations to establishing causality through direct genetic manipulation and functional validation.