Ensuring Phenotypic Data Quality: A Guide to Multi-Parameter Gating for Robust Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing high-quality multi-parameter gating for phenotypic data.

Ensuring Phenotypic Data Quality: A Guide to Multi-Parameter Gating for Robust Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing high-quality multi-parameter gating for phenotypic data. It covers the foundational principles of immunophenotyping and the critical challenges of manual analysis, explores cutting-edge computational and automated methods, details strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing gating performance, and finally, outlines robust frameworks for validating and comparing gating strategies to ensure data reproducibility and reliability in clinical and research settings.

The Critical Foundation: Understanding Phenotypic Diversity and the Imperative for Rigorous Gating

Defining Immunophenotyping and Its Role in Disease Diagnosis and Monitoring

Immunophenotyping is a foundational technique in clinical and research laboratories that identifies and classifies cells, particularly those of the immune system, based on the specific proteins (antigens) they express on their surface or intracellularly [1] [2]. This process is most commonly performed using flow cytometry, a laser-based technology that can analyze thousands of cells per second in a high-throughput manner [3] [4]. By detecting combinations of these markers, researchers and clinicians can define specific immune cell subsets, identify aberrant cell populations, and track how these populations shift in response to disease, treatment, or other experimental conditions [3]. The ability to profile the immune system at the single-cell level makes immunophenotyping an indispensable tool for diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring of a wide range of diseases, from immunodeficiencies to cancers like leukemia and multiple myeloma [1] [5].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

This section addresses common challenges encountered during immunophenotyping experiments, providing evidence-based solutions to ensure data quality and reproducibility.

Troubleshooting Common Immunophenotyping Issues

| Problem Area | Common Issue | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample & Staining | High background noise/non-specific binding | Dead cells in sample; antibody concentration too high [3] [6] | Use a viability dye (e.g., 7-AAD) to gate out dead cells; titrate antibodies to find optimal separating concentration [3] [6]. |

| Data Acquisition | Unstable signal or acquisition interruptions | Air bubbles, cell clumps, or clogs in the fluidic system [7] | Use a time gate (SSC/FSC vs. time) to identify and gate on regions of stable signal; check sample filtration and fluidics [7]. |

| Gating Strategy | Inability to resolve dim populations or define positive/negative boundaries | Poor voltage optimization; spillover spreading; lack of proper controls [6] | Perform a voltage walk to determine Minimum Voltage Requirement (MVR); use FMO controls to accurately set gates for dim markers [6]. |

| Population Analysis | Doublets misidentified as single cells | Two or more cells stuck together and analyzed as one event [8] | Use pulse geometry gating (FSC-H vs. FSC-A or FSC-W vs. FSC-H) to exclude doublets and cell clumps [8] [7]. |

| Panel Design | Excessive spillover spreading compromising data | Poor fluorophore selection; bright dyes paired with highly expressed antigens [6] | Pair bright fluorophores with low-abundance markers and dim fluorophores with highly expressed antigens [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical controls for a multicolor immunophenotyping panel? The essential controls are:

- Unstained cells: To set background autofluorescence levels.

- Single-stained controls: For calculating compensation due to spectral overlap between fluorochromes.

- Fluorescence Minus One (FMO) controls: Tubes containing all antibodies except one. These are critical for accurately setting gates, especially for dimly expressed markers or when markers are expressed on a continuum [3] [6].

- Viability dye control: To distinguish and exclude dead cells that bind antibodies non-specifically [3] [6].

Q2: How do I determine the correct gate boundaries for a mixed or smeared cell population? Do not rely on arbitrary gates. Use FMO controls to define where "negative" ends and "positive" begins for each marker in the context of your full panel. This control accounts for the spillover spreading from all other fluorochromes into the channel of interest, allowing for confident and reproducible gating [6].

Q3: My experiment requires analyzing a very rare cell population. What should I consider? The number of cells that need to be collected depends on the rarity of the population. To ensure statistically significant results, you must acquire a sufficiently large total number of events. Furthermore, use a "loose" initial gate around your target population on FSC/SSC plots to avoid losing rare cells early in the gating strategy [7].

Q4: What is the limitation of manual gating, and are there alternatives? Manual gating is subjective, can be influenced by user expertise, and becomes time-consuming for high-parameter screens. Computational and automated gating methods (e.g., in FlowJo, SPADE, viSNE) offer a fast, reliable, and reproducible way to analyze samples and can even identify new cellular subpopulations that may be missed by a pre-defined manual strategy [7].

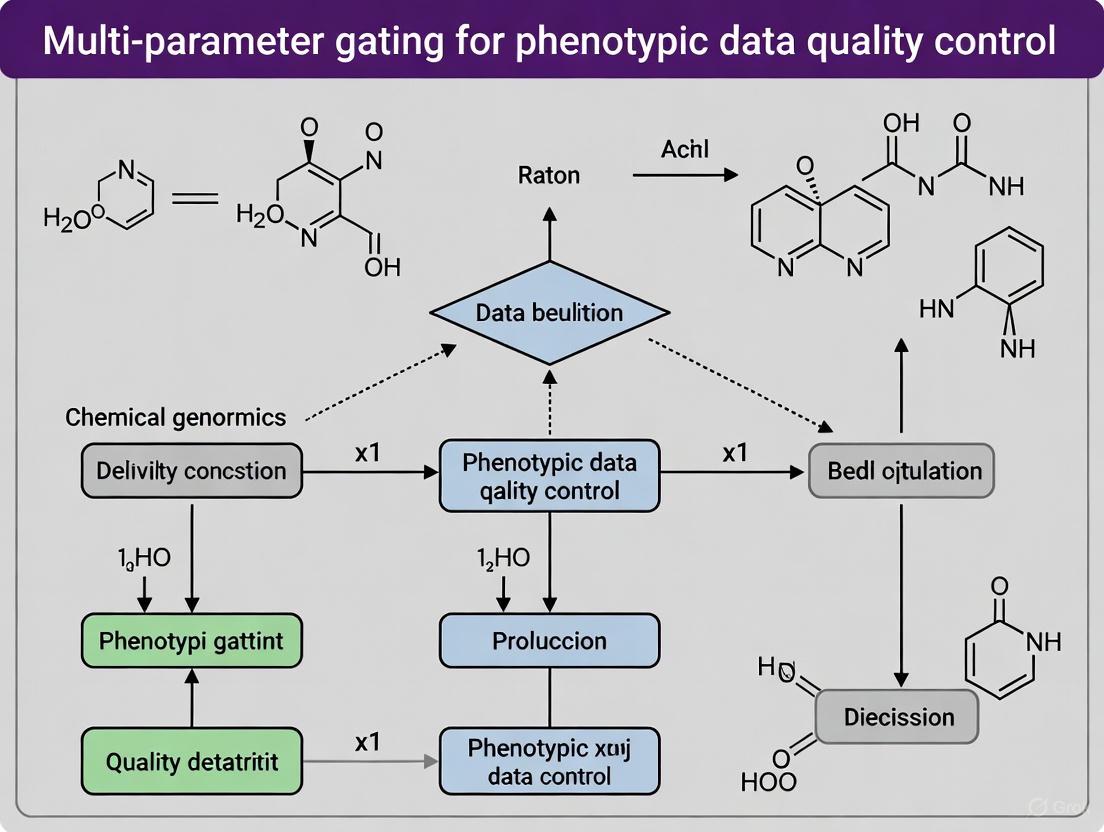

Core Experimental Workflow and Visualization

A standardized workflow is fundamental to generating high-quality, reproducible immunophenotyping data. The following diagram and protocol outline the key stages.

Immunophenotyping Workflow for Data Quality

Detailed Methodology for Multi-Parameter Flow Cytometry

Sample Preparation and Staining:

- Collect samples in appropriate anticoagulants (e.g., EDTA or heparin) [1].

- Create a single-cell suspension. For tissues, mechanical or enzymatic dissociation may be required.

- Wash cells with a buffer (e.g., PBS) containing a detergent like Triton X-100 to reduce non-specific binding [1].

- Incubate with a viability dye to mark dead cells.

- Stain with titrated, fluorophore-conjugated antibodies targeting specific surface and/or intracellular markers. Incubate in the dark, then wash to remove unbound antibody [1] [6].

Data Acquisition on Flow Cytometer:

- Use the fluidics system to transport cells single-file past a laser [8].

- As cells intercept the laser, light is scattered (Forward Scatter - FSC, Side Scatter - SSC) and fluorophores are excited, emitting light at specific wavelengths [8].

- Detectors (photodiodes and photomultiplier tubes) convert these light signals into electronic data for each cell [8].

Data Pre-processing & Multi-Parameter Gating:

- Exclude doublets: Plot FSC-H vs. FSC-A to gate on single cells [8] [7].

- Exclude dead cells: Gate on viability dye-negative cells [3].

- Apply compensation: Use single-stained controls to correct for spectral overlap [6].

- Sequential gating: Use a stepwise strategy to isolate the population of interest. A classic example for identifying human regulatory T cells (Tregs) is [3]:

- Gate on single cells -> Gate on live cells -> Gate on CD45+ leukocytes -> Gate on CD3+ T cells -> Gate on CD4+ T cells -> Identify Tregs as CD25high, FoxP3+, and optionally CD127low.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Fluorophore-conjugated Antibodies | Probes that bind with high specificity to target cell antigens (e.g., CD4, CD8, CD19); allow for detection and classification of cell types [3] [4]. |

| Viability Dyes | Amine-reactive dyes (e.g., 7-AAD, PI) that permeate dead cells; essential for excluding these cells from analysis to reduce background noise [3] [6]. |

| FMO Controls | A cocktail of all fluorophore-conjugated antibodies in a panel except one; critical for accurately defining positive and negative populations during gating [3] [6]. |

| Compensation Beads | Uniform beads that bind antibodies; used with single-color stains to create consistent and accurate compensation matrices for spectral overlap correction [6]. |

| Lymphocyte Isolation Kits | Reagents for density gradient centrifugation or negative selection to enrich for lymphocytes from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), reducing sample complexity. |

FAQs: Addressing Core Experimental Challenges

Q1: What are the primary sources of phenotypic heterogeneity in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) that can confound multiparameter gating?

A1: Phenotypic heterogeneity in AML stems from several sources that can create subpopulations with distinct marker expressions, challenging clear gating strategies.

- Genetic and Clonal Evolution: AML is not a single clone but often consists of multiple subclones with distinct genetic mutations (e.g., in FLT3, NPM1, IDH1/2). These subclones can evolve, especially under treatment pressure, leading to shifts in the phenotypic landscape detectable by flow cytometry [9].

- Epigenetic Regulation: Even within genetically identical cells, epigenetic heterogeneity can drive diverse gene expression profiles and cell states, influencing surface protein expression [9].

- Cell of Origin and Differentiation State: The disease arises from hematopoietic stem cells, and the phenotypic makeup can reflect varying degrees of differentiation block, resulting in mixtures of progenitor-like and more differentiated blast populations [10] [9].

Q2: In Multiple Myeloma (MM), how does the bone marrow microenvironment contribute to phenotypic heterogeneity and drug response variability?

A2: The bone marrow microenvironment is a critical contributor to MM heterogeneity, acting as a protective niche and influencing drug sensitivity.

- Protective Niche Interactions: Myeloma cells interact with immune cells, stromal cells, osteoclasts, and osteoblasts. These interactions provide survival and proliferative signals (e.g., via cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6) that can alter the phenotype and drug resistance of the malignant plasma cells [11].

- Inflammation and Treatment Stage: Ex vivo drug sensitivity in MM has been globally associated with bone marrow microenvironmental signatures that reflect the patient's treatment stage, clonality, and inflammation status [11].

- Non-Cell-Autonomous Resistance: The microenvironment can confer innate resistance to therapies, meaning that measuring myeloma cell phenotype alone is insufficient; the surrounding cellular context must also be considered in the analysis [11].

Q3: What advanced analytical techniques can help deconvolute complex, heterogeneous cell populations in these malignancies?

A3: Moving beyond traditional two-dimensional gating, several high-dimensional techniques are now essential.

- High-Parameter Flow and Mass Cytometry: Technologies like spectral flow cytometry (measuring full emission spectra) and mass cytometry (CyTOF) allow for the simultaneous measurement of 40+ parameters on a single-cell level. This dramatically increases the resolution to identify rare subpopulations and new cell phenotypes without significant signal spillover [12].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): This technique allows for the inference of gene regulatory networks (GRNs) at a single-cell resolution. It can capture patient-specific signatures of gene regulation that perfectly discriminate between AML and control cells, revealing heterogeneity that is masked in bulk analyses [10].

- Multiplexed Immunofluorescence and Deep Learning: Automated microscopy combined with deep-learning-based single-cell phenotyping can classify millions of cells from a bone marrow sample. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can identify latent phenotypic features and reliably distinguish malignant cells (e.g., large myeloma cells) from their benign counterparts based on size and marker expression [11].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Heterogeneity

Protocol 1: Single-Cell Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) Analysis in AML

Methodology: This protocol outlines the process for using single-cell RNA sequencing data to infer patient-specific GRNs, capturing regulatory heterogeneity [10].

- Sample Preparation & Sequencing: Obtain bone marrow samples from AML patients and healthy controls. Perform single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on sorted progenitor, monocyte, and dendritic cells.

- Data Preprocessing: Quality control, normalization, and filtering of the scRNA-seq count data.

- Network Inference: Infer gene regulatory networks using a consensus approach from multiple algorithms (e.g., ARACNE, CLR, MRNET, GENIE3) to build a robust consensus network.

- Single-Sample Network Construction: Apply the LIONESS (Linear Interpolation to Obtain Network Estimates for Single Samples) method to reconstruct a unique GRN for each individual patient and cell type.

- Downstream Analysis:

- Perform dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA, t-SNE) on network statistics or adjacency matrices.

- Use classification models (e.g., random forests) to test the predictive power of the single-cell GRNs.

- Conduct pathway enrichment analysis on highly connected and predictive genes.

Protocol 2: Image-Based Ex Vivo Drug Sensitivity Profiling in Multiple Myeloma

Methodology: This protocol, known as pharmacoscopy, details an image-based high-throughput screen to assess heterogeneous drug responses in MM patient samples [11].

- Sample Acquisition: Collect bone marrow aspirates from MM patients across different disease stages.

- Ex Vivo Drug Treatment: Plate bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMNCs) in multi-well plates. Treat with a panel of therapeutic agents (e.g., proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs, monoclonal antibodies) across a range of concentrations.

- Multiplexed Immunofluorescence and Imaging: Stain cells with fluorescent antibodies targeting key markers (e.g., CD138, CD319, CD3, CD14). Use automated high-throughput microscopy to image millions of cells per sample.

- Deep-Learning-Based Single-Cell Phenotyping:

- Train a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to classify every imaged cell into categories: CD138+/CD319+ plasma cells, CD3+ T cells, CD14+ monocytes, and "other" cells.

- A second neural network is used to identify "large" plasma cell-marker-positive cells as the putative myeloma cell population for analysis.

- Quantitative Analysis: For each drug condition, quantify the abundance and viability of the defined myeloma cell population. Integrate this ex vivo sensitivity data with matched genetic, proteomic, and clinical data to map molecular regulators of drug response.

Summarized Quantitative Data

Table 1: Technological Platforms for Multiparametric Cell Analysis

| Technology | Key Principle | Max Parameters | Advantages | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Flow Cytometry [12] | Fluorescent labels detected by lasers and PMTs/APDs | ~30 | High throughput, well-established | Fluorescence spillover complicates panel design |

| Spectral Flow Cytometry [12] | Full spectrum measurement; mathematical deconvolution | 40+ | Reduced spillover, flexible panel design | Sensitive to spectral changes in fluorescent labels |

| Mass Cytometry (CyTOF) [12] | Metal isotope labels; detection by time-of-flight mass spectrometry | 100+ | Minimal signal spillover, deep phenotyping | Lower throughput, destructive to cells, costly reagents |

| Image-Based Deep Learning [11] | Automated microscopy & CNN-based cell classification | Morphological + molecular | Provides spatial context, latent feature discovery | Computationally intensive, requires large datasets |

Table 2: Molecular and Phenotypic Heterogeneity in Case Studies

| Disease | Source of Heterogeneity | Experimental Evidence | Impact on Data Quality & Gating |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) [10] [9] | - Multiple genetic subclones- Epigenetic states- Cell of origin | - scRNA-seq GRNs enable 100% classification accuracy [10]- Mouse models require multiple mutations for disease [9] | Gating strategies based on limited markers may miss rare, resistant subclones that drive relapse. |

| Multiple Myeloma (MM) [13] [11] | - Familial predisposition [13]- Tumor microenvironment signals- Treatment-induced evolution | - Deep learning identifies phenotypically distinct "large" myeloma cells [11]- Ex vivo drug response correlates with clinical outcome [11] | Standard plasma cell gating (CD138+) may include non-malignant cells; size and multi-marker verification are critical. |

Visualized Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Single-Cell GRN Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Key Signaling Pathways in AML Pathogenesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Biological Role | Application in Featured Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorochrome Conjugated Antibodies [12] | Tag specific cell surface/intracellular proteins for detection by flow cytometry. | Panel design for high-content screening to identify multiple cell subsets simultaneously. |

| Stable Lanthanide Isotopes [12] | Metal tags for antibodies in mass cytometry; detected by time-of-flight. | Allows for >40-parameter detection with minimal spillover for deep immunophenotyping. |

| Single-Cell RNA Barcoding Kits [10] | Uniquely label mRNA from individual cells for sequencing. | Enables generation of single-cell RNA-seq data for gene regulatory network inference. |

| Recombinant Cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) [11] | Mimic bone marrow microenvironment signals in ex vivo cultures. | Used in functional assays to study their role in myeloma cell survival and drug resistance. |

| Targeted Inhibitors (e.g., Bortezomib, Venetoclax) [11] | Pharmacological probes to perturb specific pathways in cancer cells. | Applied in ex vivo drug screens to profile patient-specific sensitivity and resistance patterns. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary pitfalls of manual gating? Manual gating, the traditional method for analyzing cytometry data, suffers from three major pitfalls:

- Subjectivity: The process depends highly on the investigator's knowledge and is prone to human bias, leading to inconsistent results [14] [15].

- Time Consumption: It is a labor-intensive and slow process, with analysis of a single sample potentially taking 30 minutes to 1.5 hours [15] [16].

- Inter-Operator Variability: When multiple users analyze the same data, technical variability can be as high as 25-78% due to difficulties in reproducing the exact gating strategy [15] [16].

2. Why does increasing the number of parameters measured make manual gating unsustainable? The number of pairwise plots required for analysis increases quadratically with the number of measured parameters, an issue known as "dimensionality explosion" [14]. While instruments can now measure 40-50 parameters and are moving toward 100 dimensions, the 2D computer screen forces analysts to slice data into a series of 2D projections, a process that becomes unmanageable for large, high-dimensional datasets [14] [15].

3. Can automated methods truly replicate the expertise of a manual analyst? Yes, and they offer additional benefits. Automated gating methods, including unsupervised clustering and supervised auto-gating, are not only designed to reproduce expert manual gating but also to perform this task in a rapid, robust, and reproducible manner [14] [17]. Furthermore, some computational methods can act as "discovery" tools by identifying new, biologically relevant cellular populations that were not initially considered by the researcher, as they use mathematical algorithms to detect trends within the entire dataset [16].

4. What is the performance of automated tools compared to manual gating? Comprehensive evaluations have shown that several automated tools perform well. A 2024 study comparing 23 unsupervised clustering tools found that several, including PAC-MAN, CCAST, FlowSOM, flowClust, and DEPECHE, generally demonstrated strong performance in accurately identifying cell populations compared to manual gating as a truth standard [17]. Supervised approaches, which use pre-defined cell-type marker tables, can attain close to 100% accuracy compared to manual analysis [15].

5. How do automated methods improve reproducibility in multi-operator or multi-site studies? Automated methods are unbiased and based on unsupervised clustering or supervised algorithms, which apply the same mathematical rules to every dataset [14]. This eliminates the subjectivity inherent in manual human assessment, ensuring that the same input data will yield the same output populations regardless of who runs the analysis or where it is performed, thereby significantly enhancing reproducibility [16] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Inter-Operator Variability in Population Identification

Problem: Different scientists are gating the same samples differently, leading to inconsistent results and difficulties reproducing findings.

Solution: Implement automated gating algorithms to standardize analysis.

- Step 1: Choose an Analysis Approach. Select from two main categories of computer-aided methods [17]:

- Unsupervised Clustering: Cells are grouped into clusters based solely on marker intensities without human intervention. The resulting clusters require annotation by the researcher. Tools include FlowSOM and SPADE [14] [19].

- Supervised Auto-gating: The algorithm groups cells and also assigns cell-type labels based on a pre-specified marker table, requiring an initial training phase [17].

- Step 2: Apply the Chosen Tool. Use the selected software to analyze all samples within the study with an identical, predefined configuration.

- Step 3: Validate Results. Compare the automated output with manual gating on a small subset to ensure biological relevance. A strong correlation (e.g., r > 0.9) across key lymphocyte subsets has been demonstrated with validated AI tools [20].

Prevention: Establish a standard operating procedure (SOP) for data analysis that incorporates automated gating tools from the start of a project, especially for multi-operator or longitudinal studies [18].

Issue 2: Overwhelming Data Volume and Analysis Time

Problem: The massive data volumes from high-throughput or high-dimensional cytometry experiments make manual analysis too slow, creating a bottleneck.

Solution: Leverage computational tools for efficiency.

- Step 1: Utilize Dimensionality Reduction for Exploration. Use non-linear dimensionality reduction techniques like t-SNE or UMAP to visualize high-dimensional data in 2D or 3D plots. This allows for rapid exploratory analysis and identification of cellular heterogeneity with fewer plots [14] [19].

- Step 2: Employ Clustering for Population Identification. Apply clustering algorithms to simultaneously analyze multiple parameters across millions of cells. These algorithms can characterize and categorize diverse cell populations much faster than sequential manual gating [15].

- Step 3: Implement Automated Gating Pipelines. For routine analysis, use autogating pipelines that can be customized to robustly reproduce existing gating hierarchies. Once designed, the pipeline automatically adjusts gates for each sample, drastically reducing hands-on time [15].

Example Workflow: A clinical study using an AI-assisted workflow (DeepFlow) reduced the analysis time for each flow cytometry case to under 5 minutes, compared to the 10-20 minutes required for manual analysis [20].

Quantitative Comparison of Manual vs. Automated Gating

The table below summarizes key differences based on recent literature:

| Feature | Manual Gating | Automated Gating |

|---|---|---|

| Inherent Bias | High, depends on operator's knowledge [14] | Unbiased, based on mathematical algorithms [14] |

| Inter-Operator Variability | Can be as high as 25-78% [15] [16] | Minimal to none when the same parameters are used [16] |

| Analysis Time per Sample | 30 minutes to 1.5 hours [15] | Under 5 minutes for supervised AI tools [20] |

| Scalability with Dimensions | Poor; requires multiple biaxial plots, complexity increases quadratically [14] | Excellent; can efficiently visualize every marker simultaneously [14] |

| Discovery of Novel Populations | Limited by pre-defined gating strategy [16] | Enabled; can detect unexpected trends in the data [16] |

| Reproducibility | Low, difficult to replicate exactly [18] | High, analysis is fully objective and reproducible [18] |

Experimental Protocol: Validating an Automated Gating Tool

This protocol is adapted from a clinical validation study for an AI-assisted workflow [20].

Objective: To validate the performance of an automated gating algorithm against manual gating by expert hematopathologists as the gold standard.

Materials and Reagents:

- Biological Sample: Whole blood collected in EDTA tubes from 379 clinical cases.

- Staining Panel: A 3-tube, 10-color flow panel with 21 antibodies for immunodeficiency diseases (e.g., including CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD45, TCRαβ, IgD).

- Key Equipment and Software:

- Navios flow cytometer (or equivalent) for data acquisition.

- Kaluza software (or equivalent) for manual gating and analysis.

- DeepFlow software (or other AI-based gating tool) for automated analysis.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Process whole blood within 24 hours of collection.

- Lyse red blood cells using a lysing solution (e.g., from BD BioSciences).

- After centrifugation, resuspend the leukocyte pellet and divide it into three staining tubes.

- Incubate cells with fluorochrome-conjugated antibody panels for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature.

- Acquire data on the flow cytometer, collecting a minimum of 100,000 events per tube.

Data Analysis - Manual Gating (Gold Standard):

- Transfer the raw data files (e.g., LMD files) to analysis software.

- A technologist performs manual gating to identify lymphocyte subsets (T-cells, B-cells, NK cells, and relevant subpopulations) following a standard laboratory procedure.

- The manual gating results are reviewed and confirmed by a hematopathologist. These final percentages for each cell subset are used as the ground truth.

Data Analysis - Automated Gating:

- Process the same raw data files using the automated gating software (e.g., DeepFlow).

- The software automatically imports the files, performs clustering, and generates a report with cell counts and percentages for all defined immune cell subsets.

Validation and Statistical Comparison:

- Divide the 379 cases into training, validation, and testing sets chronologically.

- Train the AI model on the training set using the manual gating results as labels.

- Compare the automated results from the testing set against the manual gating gold standard.

- Calculate the correlation coefficient (e.g., Pearson's r) for each major lymphocyte subset to quantify the agreement between the two methods. A strong correlation (r > 0.9) indicates successful validation.

Visualization of Analysis Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the key differences in steps and outcomes between manual and automated gating workflows.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and software tools used in automated gating experiments, as cited in the literature.

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example Tools / Reagents |

|---|---|---|

| Clustering Algorithm | Identifies groups of phenotypically similar cells in an unsupervised manner, defining cell populations without prior bias. | FlowSOM [17] [19], SPADE [14] [19], flowEMMi [18] |

| Dimensionality Reduction Tool | Reduces high-dimensional data to 2D/3D for visualization and exploratory analysis, helping to reveal cellular heterogeneity. | t-SNE, UMAP [14] [19], viSNE [19] |

| Supervised Auto-gating Software | Uses pre-gated data to train a model that automatically identifies and labels cell populations in new datasets, improving consistency. | DeepFlow [20], Cytobank Automatic Gating [19] |

| Panel Design Tool | Assists in designing multicolor antibody panels by minimizing spectral overlap and matching fluorophore brightness to antigen density. | FluoroFinder's panel tool [7] |

| Viability Dye | Distinguishes live from dead cells during gating to exclude artifacts caused by non-specific antibody binding to dead cells. | Amine-based live/dead dyes [7] |

The Impact of Data Quality on Downstream Analysis and Clinical Decision-Making

Data Quality Fundamentals for Researchers

What is the tangible impact of data quality on clinical decision support systems (CDSS)?

Poor data quality directly compromises the accuracy of clinical decision support systems. Since these systems rely on patient data to provide guidance, inaccuracies or incomplete information can lead to incorrect medical recommendations.

- Accuracy and Completeness Rates: Studies have shown that data accuracy in medical registries can be as low as 67%, while completeness rates can plummet to 30.7% [21].

- Impact on System Output: The effect of poor data quality is not always straightforward. In some cases, incorrect data (e.g., a male patient coded as a female under 50) may still lead to the same clinical output as correct data, but it follows an erroneous decision path. This makes errors in clinical logic harder to detect than a simple wrong output [21].

The table below summarizes how different data quality dimensions affect clinical and research analyses [21] [22]:

| Data Quality Dimension | Impact on Downstream Analysis & Clinical Decision-Making |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | Incorrect data can lead to false positives/negatives in cell population identification and erroneous clinical guidance [21] [22]. |

| Completeness | Missing data can prevent comprehensive analysis of cell subsets and skew patient stratification and treatment decisions [21] [22]. |

| Consistency | Inconsistent data entry (e.g., "Street" vs. "St") hampers data integration and matching, crucial for multi-center research and patient record reconciliation [22]. |

| Uniqueness | Duplicate patient records can lead to incorrect cohort definitions in research and misidentification of patients in clinical care, risking patient safety [22]. |

What are the core components of a data quality assessment framework?

A systematic, business-driven approach to data quality assessment is essential for ensuring data is "fit for purpose." This involves defining and measuring quality against specific dimensions [22].

- Fitness for Purpose: Data quality is assessed against the needs of specific business processes. For example, a dataset may be incomplete if it lacks the attributes needed to run an effective record-matching algorithm [22].

- Targets and Thresholds: Organizations should define the desired state (target) and the minimum acceptable level of quality (threshold) for each data attribute and dimension [22].

- Stakeholder Engagement: Data quality is a business responsibility, not just an IT function. Representatives from across the patient lifecycle must be engaged to define requirements and targets [22].

The following table provides an example of how targets and thresholds can be defined for a data quality assessment [22]:

| Dimension | Definition | Threshold | Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Affinity of data with original intent; veracity as compared to an authoritative source. | 85% | 100% |

| Conformity | Alignment of data with the required standard. | 75% | 99.9% |

| Uniqueness | Unambiguous records in the data set. | 80% | 98% |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs for Experimental Data Quality

This section addresses common data quality issues encountered during experimental research, particularly in fields utilizing multi-parameter analysis like flow cytometry.

FAQ: During flow cytometry analysis, I am observing a weak fluorescence signal. What could be the cause?

A weak signal can stem from various issues in your sample preparation, panel design, or instrument setup [23].

- Potential Source: The antibody titer may be too dilute for your specific experimental conditions, even if it is validated for flow cytometry [23].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Titrate Antibodies: Perform a titration to determine the optimal concentration for your cell type and conditions [23].

- Match Fluorochrome to Antigen Density: Use bright fluorochromes for low-abundance (rare) proteins [23].

- Check Instrument Configuration: Verify that the correct laser and filter sets are used for your fluorochrome and that all lasers are properly aligned [23].

- Prevent Photobleaching: Protect samples from excessive light exposure, which can degrade fluorochromes, especially tandem dyes [23].

FAQ: My flow cytometry data shows high background fluorescence. How can I reduce it?

High background can obscure your true signal and is often related to sample viability, staining specificity, or compensation [23].

- Potential Source: Non-specific binding from dead cells or binding of the antibody's Fc region to Fc-receptors on cells [23].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Use Viability Dyes: Always include a viability dye (e.g., PI, 7-AAD) to identify and gate out dead cells, which bind antibodies non-specifically [23].

- Fc Receptor Blocking: Use an Fc receptor blocking reagent to prevent non-specific antibody binding [23].

- Increase Washes: Increase the volume, number, or duration of washes, particularly when using unconjugated primary antibodies [23].

- Review Compensation: Verify that compensation controls are brighter than the sample signal and that spillover spreading is not causing high background in adjacent channels [23].

FAQ: What are the best practices for gating in flow cytometry to ensure data quality?

Gating is a critical step that directly impacts the quality of your downstream analysis. A robust strategy is key to identifying a homogeneous cell population of interest [7].

- Start with Biology: Have a deep understanding of the expected cell size, granularity, and marker expression before you begin analysis [7].

- Use Appropriate Controls:

- Gating Strategy:

- Time Gate: Plot FSC or SSC against time to identify and exclude regions with acquisition problems like clogs or air bubbles [7].

- Singlets Gate: Use pulse geometry (e.g., FSC-H vs FSC-A) to exclude cell doublets and clumps [7].

- Loose Morphology Gate: Draw a relatively loose gate on FSC/SSC to isolate your main population of interest (e.g., lymphocytes) without unnecessarily excluding cells [7].

- Subset Gating: Use specific markers to further isolate the target cell population [7].

Experimental Protocols for Ensuring Phenotypic Data Quality

Protocol: A Standardized Workflow for High-Dimensional Phenotypic Data Analysis

This protocol outlines a methodology for analyzing highly multiplexed, single-cell-resolved tissue data, as implemented by tools like the multiplex image cytometry analysis toolbox (miCAT) [24]. This workflow ensures data quality from image processing through to the quantitative analysis of cell phenotypes and interactions.

- Principle: To comprehensively explore individual cell phenotypes, cell-to-cell interactions, and microenvironments within intact tissues by integrating image-based spatial information with high-dimensional molecular measurements [24].

- Applications: Defining molecular and spatial signatures in tissue biology, identifying clinically relevant features in disease, and investigating cellular "social networks" [24].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Acquisition & Single-Cell Segmentation:

- Acquire highly multiplexed images of the tissue using a technology such as Imaging Mass Cytometry (IMC) or multiplexed immunofluorescence [24].

- Apply a segmentation mask to identify individual cells within the images. This process extracts for each cell:

- The abundance of all measured markers.

- Spatial features (e.g., cell size, shape).

- Environmental information (e.g., neighboring cells) [24].

Data Compilation & Integration:

- Compile the extracted single-cell data into a standard flow cytometry file format (.fcs). This allows for the use of both image analysis and high-dimensional cytometry analysis tools in a "round-trip" fashion [24].

- Link all single-cell information back to its spatial coordinates in the original image for parallel visualization and analysis [24].

Cell Phenotype Characterization:

- Supervised Analysis: Use dimensionality reduction tools like t-SNE to project the multi-marker data into two dimensions. Manually gate and annotate cell populations based on marker expression visualized on the t-SNE map [24].

- Unsupervised Analysis: Apply clustering algorithms (e.g., PhenoGraph) to identify distinct cell phenotypes without prior bias. This reveals shared phenotype clusters across images and clinical subgroups [24].

Spatial Interaction Analysis:

- User-Guided Neighborhood Analysis: Select a population of interest (e.g., CD68+ macrophages) and retrieve all cells that are touching or are proximal to it for further analysis [24].

- Unbiased Neighborhood Analysis: Use a permutation-based algorithm to systematically compare all observed cell-to-cell interactions in a tissue against a randomized control. This identifies interactions that occur more or less frequently than expected by chance, revealing significant cellular organization [24].

- Visualize significant interactions as heatmaps or "social networks" of cells specific to conditions like tumor grade [24].

Protocol: Automated Quality Control for Phenotypic Datasets Using PhenoQC

For large-scale genomic and phenotypic research, robust computational quality control is necessary. This protocol uses the PhenoQC toolkit to automate the process of making phenotypic datasets analysis-ready [25].

- Principle: To provide a high-throughput, configuration-driven workflow that unifies data validation, ontology alignment, and missing-data imputation [25].

- Applications: Preparing phenotypic data for reliable genotype-phenotype correlation studies in genomic research, saving manual curation time [25].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Schema Validation:

Ontology-Based Semantic Alignment:

Missing-Data Imputation:

- Apply user-defined or state-of-the-art imputation methods to handle missing data. Available methods include:

- Traditional: Mean/Median/Mode.

- Machine Learning-based: K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE), Iterative SVD [25].

- The toolkit uses chunk-based parallelism for efficient processing of large datasets (up to 100,000 records) [25].

- Apply user-defined or state-of-the-art imputation methods to handle missing data. Available methods include:

Bias Quantification:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and tools used in the featured experiments and fields to ensure high-quality phenotypic data [23] [26] [24].

| Tool/Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Viability Dyes (e.g., PI, 7-AAD) | Distinguish live cells from dead cells to reduce non-specific background staining and false positives in flow cytometry [23] [7]. |

| Fc Receptor Blockers | Prevent non-specific binding of antibodies via Fc receptors, thereby reducing high background staining [23]. |

| Fluorescence-Minus-One (FMO) Controls | Critical controls for accurate gating in multicolor flow cytometry; help define positive and negative populations [23] [7]. |

| Panel Design Software (e.g., Spectra Viewer) | Tools to design multicolor panels by visualizing excitation/emission spectra, minimizing spillover spreading, and matching fluorochrome brightness to antigen density [23] [7]. |

| Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) | A standardized vocabulary for phenotypic abnormalities, allowing consistent annotation and sharing of clinical data in resources like the Genome-Phenome Analysis Platform (GPAP) [26]. |

| Metal-Isotope Labeled Antibodies | Enable highly multiplexed protein measurement (40+ parameters) in tissues via mass cytometry (e.g., CyTOF) and Imaging Mass Cytometry (IMC) [12] [24]. |

| PhenoQC Toolkit | An open-source computational toolkit for automated quality control of phenotypic data, performing schema validation, ontology alignment, and missing-data imputation [25]. |

| miCAT Toolbox | An open-source computational platform for the interactive, quantitative exploration of single-cell phenotypes and cell-to-cell interactions in multiplexed tissue images [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is a LAIP, and why is it fundamental to immunophenotypic MRD assessment? A Leukemia-Associated Immunophenotype (LAIP) is a patient-specific aberrant phenotype used to identify and track residual leukemic cells. It is characterized by one or more of the following features [27]:

- Asynchronous antigenic expression: Co-expression of immaturity and maturity biomarkers (e.g., CD34/CD117 with CD15/CD11b).

- Aberrant lineage antigen expression: Expression of lymphoid antigens on myeloid cells (e.g., CD19, CD7, CD56).

- Antigen overexpression, reduction, or loss: Abnormal expression levels of antigens like CD123, CD33, CD13, or HLA-DR [27]. LAIPs are fundamental because they allow for the detection of one leukemic cell in 10,000 normal cells, providing a highly sensitive method for Measurable Residual Disease (MRD) monitoring in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) [27] [28].

Q2: What is the difference between the "LAIP-method" and the "LAIP-based DfN-method"? These are two analytical approaches for MultiParameter Flow Cytometry (MFC)-MRD assessment [27]:

- The LAIP-method involves counting all cells within a patient-specific template created at diagnosis without further gating. It is specific but may not account for immunophenotypic shifts in the leukemic clone after therapy.

- The LAIP-based Different-from-Normal (DfN)-method involves further selecting only the cells that are positive for the LAIP-specific aberrant markers. This approach improves accuracy and comparability with molecular MRD techniques like RT-qPCR for NPM1 mutations [27]. The European LeukemiaNet (ELN) recommends using a combination of both approaches to leverage their respective advantages [27].

Q3: My gating strategy seems correct, but the MRD result is inconsistent with clinical findings. What could be wrong? Inconsistencies can arise from several sources related to LAIP quality and gating hierarchy [27]:

- Partial LAIP Expression: The most specific aberrant markers are often only partially expressed by the leukemic clone at diagnosis. Relying solely on these may miss a subset of residual cells.

- LAIP Instability: The immunophenotype of leukemic cells can shift between diagnosis and follow-up, causing the original LAIP template to become less effective.

- Operator Variability: Manual gating is subjective; differences in gate placement and strategy between operators or centers can lead to significantly different MRD results [28]. It is recommended to review your backgating hierarchy to visualize the population of interest within the context of its parent populations and confirm the gating logic [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Specificity in MRD Detection

Problem: A high background of normal cells is obscuring the true MRD signal, leading to potential false positives.

Solution:

- Refine the LAIP: Focus on incorporating high-specificity aberrant markers, particularly aberrant lineage antigen expression (e.g., CD7, CD56), which are more robust for distinguishing leukemic cells from normal hematopoietic stem cells [27] [28].

- Employ the DfN Approach: Use the LAIP-based DfN-method, which actively selects for aberrant marker positivity, to improve the signal-to-noise ratio [27].

- Leverage Computational Tools: Consider machine learning algorithms (e.g., FlowSOM, CellCnn) that can perform high-dimensional, objective analysis to highlight rare, suspect leukemic clusters that might be missed manually [28].

Issue 2: High Variability in Manual Gating Results

Problem: MRD levels quantified by manual gating differ significantly between trained operators or repeated analyses.

Solution:

- Standardize the Gating Hierarchy: Implement a pre-defined, step-wise gating strategy that is consistently applied across all samples. The following table summarizes a generalized protocol [28]:

Table 1: Standardized Gating Protocol for AML MRD Assessment

| Step | Gating Action | Purpose | Key Markers (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Select single cells | Remove doublets and cell aggregates | FSC-A vs. FSC-H |

| 2 | Identify viable nucleated cells | Remove debris and dead cells | Viability dye (e.g., DAPI-) |

| 3 | Gate blast population | Identify the lineage of interest | CD45 dim, SSC low |

| 4 | Apply patient-specific LAIP | Identify residual leukemic cells | Based on diagnostic aberrancies (e.g., CD34+/CD7+) |

- Implement a "Cluster-with-Normal" Pipeline: Use computational tools like FlowSOM to cluster cells and then compare follow-up samples to a reference of normal bone marrow. This objectifies the identification of aberrant populations [28].

- Review with Backgating: Use the backgating hierarchy view to visually explore your final gated population within its ancestral populations, ensuring the gates are logically and correctly placed [29].

Issue 3: Handling Samples with Complex Phenotypes or Rare Events

Problem: The leukemic population is phenotypically heterogeneous or present at a very low frequency, challenging the limits of detection.

Solution:

- Utilize High-Parameter Cytometry: If available, use spectral flow cytometry or mass cytometry (CyTOF). These technologies can measure 40+ parameters, allowing for a more granular dissection of complex phenotypes and better separation of rare cell populations from background [30].

- Apply Supervised Machine Learning: If a diagnostic sample is available, train a supervised classifier (e.g., k-Nearest Neighbors, Random Forest) on the diagnostic LAIP. This model can then be used to automatically find and classify phenotypically identical cells in follow-up samples, even at very low frequencies [28].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Validating MFC-MRD Results Against a Molecular Marker (NPM1 mutation)

This protocol outlines a method to validate and refine MFC-MRD assessment by comparing it with RT-qPCR for NPM1 mutations, a highly sensitive molecular benchmark [27].

1. Sample Collection and Preparation

- Collect bone marrow samples at diagnosis and post-treatment follow-up time points.

- Prepare mononuclear cells using standard Ficoll density gradient centrifugation.

- Split the sample for parallel analysis by MFC and RT-qPCR.

2. Multiparameter Flow Cytometry Analysis

- Staining: Stain ~1x10^6 cells with a pre-designed 8-color antibody panel. Include antibodies for standard blast identification (e.g., CD45, CD34) and a range of markers for LAIP identification (e.g., CD117, CD33, CD13, HLA-DR, CD7, CD56, CD4, CD15, CD123).

- Acquisition: Acquire a minimum of 500,000 events per sample on a flow cytometer to ensure sufficient sensitivity for rare event detection.

- Gating and Analysis: Perform sequential manual gating to identify the blast population. Apply both the LAIP-method and the LAIP-based DfN-method to quantify MRD.

3. Molecular MRD Assessment by RT-qPCR

- RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis: Extract total RNA from the parallel sample and synthesize cDNA.

- qPCR Amplification: Perform RT-qPCR using primers specific for the NPM1 mutation type identified at diagnosis.

- Quantification: Use a standard curve to quantify the copy number of the mutant NPM1 transcript, normalized to a control gene (e.g., ABL1). Report results as a percentage.

4. Data Correlation and Cut-off Determination

- Compare the MRD percentages obtained by the two MFC methods against the RT-qPCR results across all patient samples.

- Use statistical methods like Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis to determine the optimal MFC-MRD cut-off that best discriminates between positive and negative molecular MRD results. Note that these cut-offs may differ based on therapy (e.g., 0.034% for intensive chemotherapy vs. 0.095% for hypomethylating agents) [27].

Diagram 1: MRD validation workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for MFC-MRD Assays

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Multicolor Antibody Panels | To simultaneously detect multiple cell surface and intracellular antigens for LAIP identification. | Panels typically include CD45, CD34, CD117, CD33, CD13, HLA-DR, and a suite of lymphoid markers (CD7, CD56, CD19, etc.) [27] [28]. |

| Viability Dye | To distinguish and exclude dead cells during analysis, which can cause non-specific antibody binding. | e.g., DAPI, Propidium Iodide (PI), or fixable viability dyes. |

| Flow Cytometer | Instrument for acquiring multiparametric data from single cells in suspension. | Conventional (up to 60 parameters) or spectral flow cytometers (e.g., Cytek Aurora, Sony ID7000) offer enhanced parameter resolution [30]. |

| Normal Bone Marrow Controls | To establish a "different-from-normal" (DfN) baseline and understand the immunophenotype of regenerating marrow. | Essential for distinguishing true MRD from background hematopoietic progenitors, especially post-therapy [27]. |

| Computational Analysis Software | For automated, high-dimensional data analysis to reduce subjectivity and identify rare cell populations. | Tools include FlowSOM (clustering), UMAP/t-SNE (visualization), and supervised classifiers (e.g., kNN, Random Forest) [28]. |

Diagram 2: MFC-MRD core concepts

From Manual to Automated: A Landscape of Modern Gating Methodologies and Tools

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Algorithm Selection and Performance

Q1: My cell classification model has high accuracy on training data but poor performance on new samples. What is the cause and how can I fix it?

A: This is a classic sign of overfitting.

- For k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN): This occurs when the value of

Kis too small (e.g., K=1). A model with K=1 considers only its nearest neighbor, making it highly sensitive to noise and outliers in your training data [31].- Solution: Use a validation set to find the optimal

K. Plot the validation error rate for different K values; the K with the lowest error is optimal. Typically, higher values of K create a smoother decision boundary and reduce overfitting [31].

- Solution: Use a validation set to find the optimal

- For Support Vector Machines (SVM): Overfitting can occur if the regularization parameter

Cis too high. A highCvalue tells the model to prioritize correctly classifying every training point, even if it requires creating a highly complex, wiggly decision boundary that may not generalize [32].

Q2: How do I handle high-dimensional mass cytometry data where the number of markers (features) far exceeds the number of cells (samples)?

A: This is a common challenge in immune monitoring studies.

- SVM is particularly well-suited for this scenario. Its effectiveness depends on the support vectors and the margin, not the dimensionality of the input space, making it robust against the "curse of dimensionality" [32]. It can achieve high accuracy even when the number of features is greater than the number of samples [32].

- kNN, conversely, often performs worse with high-dimensional data. In high-dimensional space, the concept of "nearest neighbors" can become less meaningful as the distance between all points becomes more similar, a phenomenon known as the "distance concentration" problem [34].

Q3: My dataset has significant batch effects from multiple experimental runs. How can I prevent my classifier from learning these artifacts?

A: Batch effects are a major confounder in large-scale studies.

- Data Preprocessing is Critical: Implement a robust data preprocessing pipeline to correct for batch effects before training your classifier. This includes normalization and batch correction algorithms. For cytometry data, tools and packages like

CytoNormare specifically designed for this purpose [35]. - Confounder-Correcting SVM (ccSVM): A specialized approach involves using a confounder-correcting SVM (ccSVM). This method modifies the standard SVM objective function to minimize the statistical dependence (e.g., using Hilbert-Schmidt Independence Criterion - HSIC) between the classifier's predictions and the confounding variables (like batch ID). This forces the model to base its predictions on features independent of the confounder [36].

Data Preprocessing and Experimental Design

Q4: Why is my kNN model's performance so poor, even after choosing a seemingly good K value?

A: kNN is a distance-based algorithm and is highly sensitive to the scale of your features [34].

- Cause: If the markers in your mass cytometry data are on different scales (e.g., CD3 expression ranging from 0-1000 vs. CD4 ranging from 0-50), the marker with the larger scale will dominate the distance calculation, and the model will be biased towards that feature.

- Solution: Always standardize your data before using kNN. Apply either Standard Scaler (which transforms data to have zero mean and unit variance) or Min-Max Normalization (which scales data to a fixed range, e.g., [0, 1]) [34]. This ensures all markers contribute equally to the distance metric.

Q5: How can I ensure my functional variant assay results are reliable and not due to clonal variation or experimental artifacts?

A: Employ a well-controlled experimental design like CRISPR-Select. This method uses an internal, neutral control mutation (WT') knocked into the same cell population as the variant of interest [37].

- Protocol: The frequencies of the variant and the WT' control are tracked relative to each other over time, space, or cell state. By using this paired, internal control, the method effectively dilutes out confounding effects from clonal variation, CRISPR off-target effects, and other experimental variables. The key is to calculate the absolute numbers of knock-in alleles to ensure results are based on a sufficient number of cells for statistical power [37].

Table 1: Comparison of kNN and SVM for Cell Classification Tasks

| Aspect | k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) | Support Vector Machine (SVM) |

|---|---|---|

| Key Principle | Instance-based learning; class is determined by majority vote of the K nearest data points [34] [31] | Finds the optimal hyperplane that maximizes the margin between classes [36] [32] |

| Performance with High Dimensions | Poor; suffers from the curse of dimensionality [34] | Excellent; effective when features > samples [32] |

| Handling Noisy Data | Sensitive to irrelevant features and noise; requires careful feature selection and scaling [34] | Robust to noise due to margin maximization, but performance can degrade with significant noise [32] |

| Data Scaling Requirement | Critical; sensitive to feature scale, requires standardization [34] | Critical; performance improves with feature scaling [32] |

| Computational Load | High prediction time; must store entire dataset and compute distances to all points for prediction [34] [38] | High training time, especially for large datasets; but fast prediction [32] |

| Key Parameters to Tune | Number of neighbors (K), Distance metric (e.g., Euclidean, Manhattan), Weighting (uniform, distance) [31] [38] | Regularization (C), Kernel type (linear, RBF, etc.), Gamma (for RBF kernel) [32] [33] |

| Best Suited For | Smaller datasets, multi-class problems, data with low dimensionality after preprocessing [34] [31] | High-dimensional data (e.g., mass cytometry), data with clear margin of separation, complex non-linear problems (with kernel trick) [36] [32] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Cell Classification Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Generalization (Overfitting) | kNN: K value too low [31].SVM: C parameter too high, leading to a complex model [32]. | Tune K and C using validation curves and cross-validation. For kNN, increase K. For SVM, decrease C. |

| Slow Model Training | kNN: N/A (training is trivial) [34].SVM: Dataset is too large; algorithm complexity is high [32]. | For SVM, use stochastic gradient descent solvers. For large datasets, consider linear SVMs or other algorithms. |

| Model Bias Towards Majority Cell Populations | Imbalanced class distribution in the training data [32]. | Use resampling techniques (oversampling minority classes, undersampling majority classes). Apply class weights in the SVM or kNN algorithm. |

| Inconsistent Results Across Batches | Strong batch effects confounding the model [36] [35]. | Apply batch effect correction (e.g., CytoNorm [35]). Use confounder-correcting algorithms like ccSVM [36]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: kNN-Based Cell Population Classification from Mass Cytometry Data

This protocol details the steps for using kNN to classify cell populations in a standardized mass cytometry dataset.

Data Preprocessing and Normalization:

- Bead-Based Normalization: Use a tool like

CATALYSTto correct for instrument noise and signal drift over time [35]. - Transformations: Apply an arcsinh transformation with a cofactor of 5 to stabilize the variance of the cytometry data.

- Standardization: Standardize all marker expression values using Z-score normalization (Standard Scaler) to ensure no single marker dominates the distance calculation [34].

- Bead-Based Normalization: Use a tool like

Dimensionality Reduction and Feature Selection (Optional but Recommended):

- To mitigate the curse of dimensionality for kNN, reduce the number of features.

- Perform manual gating or use automated tools (

flowClean,flowDensity) to remove debris and dead cells [35]. - Use expert knowledge to select the most biologically relevant markers for the cell populations of interest.

Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning:

- Split the preprocessed data into training (e.g., 70%) and test (e.g., 30%) sets, using stratification to maintain class distribution.

- Initiate the

KNeighborsClassifier. UseGridSearchCVwith 5-fold cross-validation on the training set to find the optimalK(e.g., range 1-25), the bestdistance metric(e.g., Euclidean, Manhattan), andweightingscheme (uniform or distance-based) [38].

Model Evaluation:

- Use the optimized model to make predictions on the held-out test set.

- Evaluate performance using accuracy, F1-score, and a confusion matrix. For a visual assessment, project the test set into a 2D space using UMAP and plot the decision boundaries.

Protocol 2: SVM for High-Dimensional Phenotypic Classification with Batch Effect Correction

This protocol leverages SVM's strength in high-dimensional spaces and incorporates steps to mitigate batch effects.

Data Preprocessing and Batch Integration:

- Follow the same initial preprocessing and normalization steps as in Protocol 1.

- Critical Step - Batch Correction: If the data comes from multiple batches or days, apply a batch correction algorithm like

CytoNormto align the distributions of the different batches [35].

Model Training with Confounder Correction:

- Split the batch-corrected data into training and test sets.

- Option A - Standard SVM: Use

GridSearchCVto tune theCparameter and, if using an RBF kernel, thegammaparameter [33]. - Option B - Confounder-Correcting SVM (ccSVM): If batch effects persist, consider a ccSVM implementation. This involves formulating the SVM optimization to include a term that minimizes the dependence between the learned model and the batch information, effectively forcing the model to ignore batch-related variance [36].

Validation and Interpretation:

- Validate the final model on the test set.

- For linear SVMs, you can examine the weight vector

wto determine which markers (features) were most influential in the classification. Techniques like Recursive Feature Elimination with SVM (SVM-RFE) can also be used to rank feature importance [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Cell Classification Experiments

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application in Context |

|---|---|

| CRISPR-Select Cassette | A set of reagents (CRISPR-Cas9, ssODN with variant, ssODN with WT' control) for performing highly controlled functional assays to determine the phenotypic impact of genetic variants (e.g., on cell state or proliferation) in their proper genomic context [37]. |

| Mass Cytometry Panel (Antibodies) | A panel of metal-tagged antibodies targeting specific cell surface and intracellular markers. These are the primary features used for cell classification and phenotyping in mass cytometry experiments [35]. |

| Normalization Beads | Beads impregnated with a known concentration of heavy metals. They are run alongside cell samples and are used to correct for instrument noise and signal drift during acquisition, which is a critical first step in data preprocessing [35]. |

| CATALYST R Package | An R package for the pre-processing of mass cytometry data. Its functions include bead-based normalization and sample debarcoding, which are essential for ensuring data quality before analysis [35]. |

| CytoNorm R Package | An R package designed specifically for batch effect normalization in cytometry data. It is crucial for integrating data from large-scale, multicenter, or multibatch studies [35]. |

| FlowSOM & UMAP | Dimensionality reduction and clustering tools. FlowSOM is used for high-speed clustering of cells, while UMAP provides a 2D visualization of high-dimensional data, both aiding in data exploration and analysis [35]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

kNN vs SVM Cell Classification Workflow

This diagram illustrates the logical flow and key decision points for choosing and applying kNN or SVM to a cell classification problem.

High-Dimensional Data Analysis Pipeline

This diagram details the specific workflow for processing high-dimensional cytometry data, highlighting critical quality control and batch correction steps.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary strengths of FlowSOM and PhenoGraph? FlowSOM is renowned for its speed, scalability, and stability with large sample sizes. It performs well in internal and external evaluations and is relatively stable as sample size increases, making it suitable for high-throughput analysis [39] [40]. PhenoGraph is particularly powerful at identifying refined sub-populations and is highly effective at detecting rare cell types due to its graph-based approach [40].

Q2: How do I decide whether to use FlowSOM or PhenoGraph for my dataset? Your choice should balance the need for resolution, computational resources, and data size. The following table summarizes key decision factors:

| Consideration | FlowSOM | PhenoGraph |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Speed, stability, and handling of large datasets [40] | Identification of fine-grained and rare populations [40] |

| Clustering Resolution | Tends to group similar cells into meta-clusters; user-directed resolution [40] | Tends to split biologically similar cells; can over-cluster [41] [40] |

| Impact of Sample Size | Performance is relatively stable as sample size increases [40] | Performance and number of clusters identified can be impacted by increased sample size [40] |

| Best Use Case | Standardized, reproducible analysis pipelines; large datasets (>100,000 cells) [39] | Discovering novel or rare cell populations; datasets of at least 100,000 cells [41] |

Q3: Should I downsample my data before clustering? It is generally recommended to avoid downsampling whenever possible, as it can lead to the loss of rare cell populations [42]. If you must downsample, ensure you use a sufficient number of events (e.g., 100,000 cells) to maintain population diversity [41]. For large datasets, FlowSOM is a preferable choice as it can handle millions of events without requiring downsampling [42].

Q4: Is over-clustering or under-clustering better? Many experts recommend a strategy of intentional over-clustering, followed by manual merging of related clusters post-analysis. This is preferable to under-clustering, which can cause distinct populations to be grouped together and missed [42].

Q5: Why are my clustering results different each time I run PhenoGraph? PhenoGraph results can be highly sensitive to the number of input cells and the random seed used. For reproducible results with Rphenograph, always set a fixed random seed before running the analysis. The FastPG implementation, while faster, may not be fully deterministic and can produce variable results even with a fixed seed [41].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common FlowSOM Issues

Problem: FlowSOM analysis fails or runs very slowly. This is often due to the dataset exceeding memory limits.

- Solution: Check the event and channel limits on your platform (e.g., Cytobank). If you see a "data approaching memory limits" warning, try the following [43] [44]:

- Reduce the number of input events by sampling.

- Pre-gate your data to a population of interest (e.g., CD45+ cells) using the "Split Files by Population" feature to create a smaller, focused experiment [43].

- Ensure you are only selecting relevant phenotyping markers as clustering channels, excluding scatter, viability, and DNA content channels [44].

Problem: FlowSOM results contain too many very small clusters.

- Solution: The granularity of FlowSOM clusters is controlled by the

xdimandydimparameters (which define the grid size of the self-organizing map) and the final number of meta-clusters. Start with a smaller grid (e.g., 10x10) and a lower number of meta-clusters, then increase gradually to achieve the desired resolution [39] [44].

Problem: Unstable or unreliable clusters.

- Solution: This can occur if the Self-Organizing Map (SOM) is not sufficiently trained. Increase the

rlenparameter, which controls the number of training iterations. A higherrlen(e.g., 50-100) leads to more stable and reliable clustering outcomes [39].

Common PhenoGraph Issues

Problem: The number of clusters identified by PhenoGraph seems arbitrary and changes with settings.

The number of clusters (K) in PhenoGraph is highly dependent on the k parameter (nearest neighbors) and the total number of cells analyzed.

- Solution [42] [41]:

- Do not use a fixed

kvalue across all analyses. Optimize it for your specific dataset. - Use a sufficient number of cells as input (at least 100,000 is recommended).

- Use a strategy of over-clustering and then manually merge related clusters based on biological knowledge and marker expression patterns.

- Do not use a fixed

Problem: PhenoGraph splits a homogeneous population into multiple clusters.

- Solution: This is a known behavior of PhenoGraph. If a single biological population (e.g., naive T cells) appears as multiple clusters on a t-SNE plot, it is often appropriate to manually merge these clusters into one for downstream analysis [41].

Problem: PhenoGraph analysis takes too long.

- Solution: For large datasets, consider using the FastPG implementation, which offers a significant speed improvement. Be aware that FastPG may be less deterministic than the original Rphenograph [41].

General Clustering Issues

Problem: Algorithm fails (for FlowSOM, PhenoGraph, SPADE, viSNE).

- Solution [43]:

- Check file size: Files that are too large (in events or channels) are a common cause of failure. Reduce file size by pre-gating and using "Split Files by Population".

- Check FCS file keywords: Files not written with standard keywords can cause errors. Try re-writing the FCS files within your analysis platform.

- Check scaling: For algorithms like viSNE, ensure your data is transformed using arcsinh and not log scale.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standardized Clustering Workflow for High-Dimensional Cytometry Data

The following diagram outlines a robust, generalized workflow for applying FlowSOM and PhenoGraph to mass or spectral flow cytometry data, ensuring data quality and analytical rigor.

Key Parameter Optimization

Optimal clustering requires careful parameter tuning. The table below summarizes critical parameters for FlowSOM and PhenoGraph, with guidelines for optimization based on your data and goals [39] [42] [41].

| Algorithm | Parameter | Function & Impact | Optimization Guideline |

|---|---|---|---|

| FlowSOM | xdim / ydim |

Controls the number of nodes in the primary SOM grid; influences granularity. | Start with 10x10. Increase (e.g., to 14x14) for finer resolution on complex datasets [39]. |

rlen |

Number of iterations for SOM training; impacts stability. | Default is 10. Increase to 50-100 for more stable, reliable clusters [39]. | |

Meta-cluster Number (k) |

Final number of consolidated cell populations. | Use a number that reflects biological expectation. Start low and increase, or over-cluster and merge [42]. | |

| PhenoGraph | k (nearest neighbors) |

Size of the neighborhood graph; dramatically affects cluster number and size. | Test values (e.g., 30, 50, 100). Use a higher k for larger datasets. Aim to over-cluster [42] [41]. |

| Random Seed | Ensures computational reproducibility. | Always set a fixed random seed before analysis for reproducible results [41]. | |

| Input Cell Number | The total number of cells analyzed. | Use at least 100,000 cells for stable results. Avoid downsampling when possible [41]. |

The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for implementing unsupervised clustering workflows in high-dimensional cytometry.

| Tool / Resource | Function | Role in Phenotypic Data Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Cytobank Platform | Web-based platform for cytometry data analysis. | Provides integrated environments to run FlowSOM, viSNE, and CITRUS, often with guided workflows and troubleshooting support [43] [44]. |

| R Programming Language | Open-source environment for statistical computing. | The primary platform for running algorithms like Rphenograph and FlowSOM via specific packages, enabling customizable and reproducible analysis pipelines [45] [39]. |

| FastPG | A high-speed implementation of the PhenoGraph algorithm. | Drastically reduces computation time for large datasets, though users should be aware of potential variability in results compared to the original algorithm [41]. |

| t-SNE & UMAP | Dimensionality reduction algorithms. | Not clustering methods themselves, but essential for visualizing the high-dimensional relationships and cluster structures identified by FlowSOM and PhenoGraph [45] [46]. |

| ConsensusClusterPlus | An R package for determining the stability of cluster assignments. | Often used in the meta-clustering step of FlowSOM to help determine a robust number of final meta-clusters [42]. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting and guidance for researchers using BD ElastiGate Software, an automated gating tool for flow cytometry data analysis. ElastiGate addresses a key challenge in multi-parameter gating for phenotypic data quality research by using elastic image registration to adapt gates to biological and technical variability across samples [47] [48]. This document assists scientists in leveraging this technology to improve the consistency, objectivity, and efficiency of their flow cytometry workflows.

FAQ: Understanding BD ElastiGate

1. What is the core technology behind BD ElastiGate? BD ElastiGate uses a visual pattern recognition approach. It converts flow cytometry plots and histograms into images and then employs an elastic B-spline image registration algorithm. This technique warps a pre-gated training plot image to match a new, ungated target plot image. The same transformation is then applied to the gate vertices, allowing them to follow local shifts in the data [47] [49].

2. How does ElastiGate improve upon existing automated gating methods? Unlike clustering- or density-based algorithms (e.g., flowDensity), ElastiGate does not make assumptions about population shapes or rely on peak finding. It is designed to mimic how an expert analyst visually adjusts gates, making it particularly effective for highly variable data or continuously expressed markers where batch processing often fails [47] [48].

3. What are the main applications and performance metrics of ElastiGate? ElastiGate has been validated across various biologically relevant datasets, including CAR-T cell manufacturing, immunophenotyping, and cytotoxicity assays. Its accuracy, measured by the F1 score when compared to manual gating, consistently averages >0.9 across all gates, demonstrating performance similar to expert manual analysis [47] [50].

4. Where can I access and how do I install the BD ElastiGate plugin? The ElastiGate plugin is available for FlowJo v10 software. Installation involves downloading the plugin from the official FlowJo website, extracting the JAR file, and placing it in the FlowJo plugins folder. After restarting FlowJo, the plugin becomes available under the "Workspace > Plugins" menu [49].

5. Can ElastiGate handle all types of gates? ElastiGate supports polygon gates and linear gates for histograms. However, it converts ellipses into polygons and does not support Boolean gates [49].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Installation & Setup | Plugin not appearing in FlowJo. | Ensure the JAR file is in the correct plugins folder and rescan for plugins via FlowJo > Preferences > Diagnostics [49]. |

| Error when selecting target samples. | Confirm that target samples have the same parameters as the training files. Training files are automatically ignored as targets [49]. | |

| Gate Performance | Poor gate adjustment on sparse plots. | Lower the "Density mode" setting (e.g., to 0 or 1) to improve performance in low-density areas [49]. |

| Gate movement is too rigid. | Enable the "Interpolate gate vertices" option. This adds more vertices, allowing the gate to curve and follow data shifts more flexibly [49]. | |

| Gating fails when a population is missing in a target file. | Check the "Ignore non-matching populations" option. This uses a mask to focus registration only on populations present in both images [49]. | |

| Data Interpretation | High variability in gating results for a specific population. | Consult the validation data; populations with low event counts (e.g., intermediate monocytes) naturally have more variability. Manually review and adjust these gates if necessary [47]. |

Optimization Parameters Guide

The ElastiGate plugin offers several options to fine-tune performance for your specific data [49]:

- Density Mode (0-3): Use lower values (0,1) for sparse plots or when gate placement is determined by sparse areas. Use higher values (2,3) for dense populations.

- Interpolate Gate Vertices: Enable this for complex gate shapes to allow for more elastic deformation.

- Preserve Gate Type: Keep this checked to maintain rectangles and quad gates as their original type. Uncheck to convert them to more flexible polygons.

- Ignore Non-matching Populations: Essential for experiments where not all cell populations are present in every sample (e.g., FMO controls).

Experimental Protocols & Validation

The following table summarizes the experimental contexts in which BD ElastiGate has been rigorously validated, providing a benchmark for your own research.

| Experiment / Assay | Sample Type | Key Performance Metric (vs. Manual Gating) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysed Whole-Blood Scatter Gating | 31 blood-derived samples | Median F1 scores: Granulocytes (0.979), Lymphocytes (0.944), Monocytes (0.841) [47]. | [47] |

| Monocyte Subset Analysis | 20 blood samples | Median F1 scores >0.93 for most gates [47]. | [47] |

| Stem Cell Enumeration (SCE) | 128 samples (Bone Marrow, Cord Blood, Apheresis) | Median F1 scores >0.93, comparable to manual analysts [50]. | [50] |

| Lymphoid Screening Tube (LST) | 80 Peripheral Blood, 28 Bone Marrow | Median F1 scores >0.945 for most populations [50]. | [50] |

Detailed Protocol: Implementing ElastiGate for a Cell Therapy QC Assay

This protocol outlines the steps to use ElastiGate for quality control in cell therapy manufacturing, a common application cited in validation studies [47].

1. Training Sample Selection:

- Select one or more representative FCS files that have been meticulously gated by an expert according to your established gating strategy.

- Ensure the training files cover expected biological variability (e.g., different donors, processing conditions).

2. Plugin Setup in FlowJo:

- Open your workspace in FlowJo v10. Right-click on a fully gated training sample.

- Navigate to Workspace > Plugins > BD ElastiGate Plugin.