Cross-Species Chemical Genomics: A One Health Strategy for Combating Infectious Diseases and Antimicrobial Resistance

This article explores the transformative potential of cross-species chemical genomics in infectious disease research and drug development.

Cross-Species Chemical Genomics: A One Health Strategy for Combating Infectious Diseases and Antimicrobial Resistance

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of cross-species chemical genomics in infectious disease research and drug development. By integrating chemical-genetic interaction profiling across diverse pathogens and host organisms, this approach accelerates the identification of novel drug targets, unravels mechanisms of antibiotic resistance, and informs therapeutic strategies for zoonotic threats. We cover foundational principles, key methodologies like CRISPRi screening, and applications in understanding pathogen biology. The discussion extends to troubleshooting experimental challenges, validating findings through comparative genomics, and leveraging a 'One Health' framework to combat pressing issues such as multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and emerging zoonotic viruses. This synthesis provides a roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to harness cross-species insights for next-generation antimicrobial discovery.

Foundations of Chemical Genomics and the One Health Imperative

Defining Cross-Species Chemical Genomics in Infectious Disease Research

Cross-species chemical genomics represents a transformative approach in infectious disease research, integrating comparative genomics with chemical biology to identify and target evolutionarily conserved molecular vulnerabilities across pathogens and their hosts. This methodology is predicated on the systematic identification of essential genes and pathways that are conserved between pathogen species or at the host-pathogen interface, followed by high-throughput screening of chemical compounds to discover agents that modulate these targets. The field has gained significant momentum with advances in large-scale genomic sequencing and computational biology, enabling researchers to move beyond single-organism studies toward a comprehensive understanding of cross-species functional conservation [1] [2].

The fundamental premise of cross-species chemical genomics lies in its ability to distinguish between conserved biological processes that are essential for pathogen survival and host-specific adaptations. By comparing genomic data across multiple species—from bacteria to mammals—researchers can identify genes that have been maintained through evolutionary time, suggesting critical functional importance [2]. When applied to infectious diseases, this approach facilitates the discovery of chemical compounds that target these conserved elements, potentially yielding broad-spectrum therapeutics effective against multiple pathogens or enabling host-directed therapies that modulate conserved infection mechanisms. This strategy is particularly valuable for addressing the challenges posed by rapidly evolving pathogens and emerging antimicrobial resistance, as targeting evolutionarily constrained systems reduces the likelihood of resistance development [1].

Framed within the broader thesis of cross-species chemical genomics for infectious disease research, this approach represents a paradigm shift from pathogen-specific drug discovery to the identification of core biological networks that govern infection across taxonomic boundaries. The integration of computational genomics with high-throughput chemical screening creates a powerful framework for understanding the fundamental principles of host-pathogen interactions while simultaneously accelerating the development of novel therapeutic strategies with potentially broader efficacy spectra than conventional antibiotics and antivirals [1] [3].

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

Core Principles of Comparative Genomics

Comparative genomics provides the foundational framework for cross-species chemical genomics by enabling systematic analysis of genetic similarities and differences across organisms. At its core, this discipline involves comparing genome sequences of different species to identify what distinguishes them at the molecular level and to understand how evolutionary processes have shaped their genetic architectures [2]. The power of comparative genomics stems from the fundamental biological principle that functionally important elements of genomes remain conserved through evolutionary time due to selective pressure, while non-functional sequences diverge more rapidly. This conservation allows researchers to identify genes critical for cellular functions across diverse organisms, including those between pathogens and their hosts [2].

The analytical process begins with identifying synteny—the conservation of gene order and arrangement across different species. As illustrated by comparisons between human and mouse genomes, syntenic blocks reveal chromosomal segments that have been preserved through millions of years of evolution, highlighting regions of potential functional importance [2]. Finer-resolution comparisons involve aligning homologous DNA sequences from different species to identify conserved coding and non-coding elements. The phylogenetic distance between compared organisms determines the type of information that can be extracted: comparisons at large evolutionary distances (e.g., over one billion years) primarily reveal conserved genes, while analyses of closely related species (e.g., human and chimpanzee) can identify sequence differences accounting for biological variations [2].

Integration with Chemical Genomics

Chemical genomics expands upon comparative genomics by systematically testing how chemical compounds affect biological systems, mapping interactions between small molecules and their cellular targets. When integrated with cross-species genomic comparisons, this approach enables the identification of compounds that target evolutionarily conserved processes. The underlying hypothesis is that chemical probes or therapeutics effective against conserved targets in multiple pathogen species may have broader spectrum activity, while compounds targeting host factors conserved with model organisms may facilitate translation of findings from experimental systems to human applications [1].

This integrated approach relies on the concept of functional conservation—the preservation of biological roles across species despite potential sequence divergence. By identifying functionally equivalent genes and pathways through comparative genomics, researchers can prioritize targets for chemical screening that have higher probabilities of success across multiple pathogen species or in both model organisms and humans. The emergence of large-language models (LLMs) and other artificial intelligence approaches in biology has further enhanced this capability by enabling more sophisticated identification of long-range dependencies and contextual relationships within biological sequences that signify functional importance [1].

Biological Language Models for Sequence Analysis

Large language models (LLMs) originally developed for natural language processing have been successfully adapted for biological sequence analysis, transforming how researchers identify conserved functional elements across species. These models treat genomic and protein sequences as linguistic entities with distinctive patterns and structural characteristics, enabling them to capture long-range dependencies and contextual relationships within biological data [1]. Through self-supervised learning on massive datasets, biological LLMs acquire generalizable patterns, evolutionary characteristics, and structural features that can be specialized for specific comparative analyses with smaller, labeled datasets.

The table below summarizes the primary classes of biological LLMs relevant to cross-species chemical genomics:

Table 1: Classes of Biological Large Language Models for Cross-Species Analysis

| Model Type | Architecture Variants | Training Data | Key Applications in Cross-Species Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Language Models (pLMs) | Encoder-decoder (ProtT5, xTrimoPGLM), Encoder-only (ESM-1b, ESM-2), Decoder-only (ProtGPT2, ProGen) | UniRef50, UniRef90, BFD100, ColabFoldDB | Predicting mutation effects, protein structure inference, functional annotation across species [1] |

| Genomic Language Models (gLMs) | Transformer architectures with specialized tokenization | Genomic sequences from multiple species | Identifying conserved regulatory elements, predicting variant effects, annotating functional regions [1] |

| Multimodal Models | Integrated architectures combining multiple data types | Multi-omics datasets (genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic) | Cross-species pathway analysis, host-pathogen interaction prediction, integrative functional annotation [1] |

These models employ different architectural frameworks, each with distinct advantages for biological questions. Encoder-decoder models like ProtT5 and xTrimoPGLM transform protein sequences into contextual embeddings then generate outputs from these representations, supporting both understanding (alignment, classification) and generation (protein design) tasks [1]. Encoder-only models such as ESM-1b and ESM-2 focus exclusively on generating high-quality contextual embeddings, effectively capturing residue-level dependencies through self-attention, making them suitable for secondary structure prediction and mutation effect analysis across species [1]. Decoder-only models, including ProtGPT2 and ProGen, excel at generating new sequences based on learned patterns, valuable for designing novel proteins or predicting evolutionary trajectories.

Comparative Genomics Platforms and Databases

Specialized computational platforms have been developed to facilitate cross-species genomic comparisons, with the Comparative Genome Dashboard representing a particularly advanced tool for interactive exploration of functional similarities and differences between organisms. This web-based software provides a high-level graphical survey of cellular functions and enables users to drill down to examine subsystems of interest in greater detail [3]. The dashboard is organized hierarchically, with top-level panels for cellular systems such as biosynthesis, energy metabolism, transport, and non-metabolic functions, each containing bar graphs that plot numbers of compounds or gene products for each organism across related subsystems [3].

The dashboard employs three primary types of subsystems for functional comparison:

- Pathway-based subsystems compute compound production or consumption capabilities based on pathway classes and metabolite classes, using the Pathway Tools algorithm to determine pathway presence in organism-specific databases [3].

- Transport-based subsystems identify substrate transport capabilities by analyzing all transport reactions defined in a Pathway/Genome Database (PGDB), categorizing transported compounds by class [3].

- Gene Ontology (GO)-based subsystems quantify functional capabilities by counting genes annotated to specific GO terms or their child terms, excluding those in exception lists [3].

This hierarchical structure enables researchers to quickly transition between high-level functional surveys and detailed mechanistic analyses, facilitating rapid identification of conserved functions potential chemical targets across multiple pathogen species or between pathogens and model organisms [3].

Additional essential databases for cross-species chemical genomics include:

- BioCyc collection: A comprehensive resource of Pathway/Genome Databases (PGDBs) for thousands of organisms, enabling systematic comparison of metabolic pathways and transport capabilities [3].

- COG (Clusters of Orthologous Genes): Categorizes protein families into functional groups, though with less granularity than the Comparative Genome Dashboard [3].

- Genome Properties: Defines phenotypic traits based on protein families and pathway presence using rule-based systems [3].

Table 2: Quantitative Genomic Comparisons Across Model Organisms

| Organism | Genome Size (Million Base Pairs) | Number of Genes | Chromosome Number | Notable Features for Chemical Genomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens | 3,000 | ~25,000 | 46 | Reference for host-pathogen interactions, conservation analysis |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 157 | ~25,000 | 5 | Demonstrates that genome size doesn't correlate with gene number [2] |

| Drosophila melanogaster | 165 | ~13,000 | 4 | 60% gene conservation with humans; model for host defense mechanisms [2] |

| Escherichia coli | 4.6 | ~4,300 | 1 | Model bacterial pathogen; reference for antibacterial target identification |

Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

Cross-Species Target Identification Pipeline

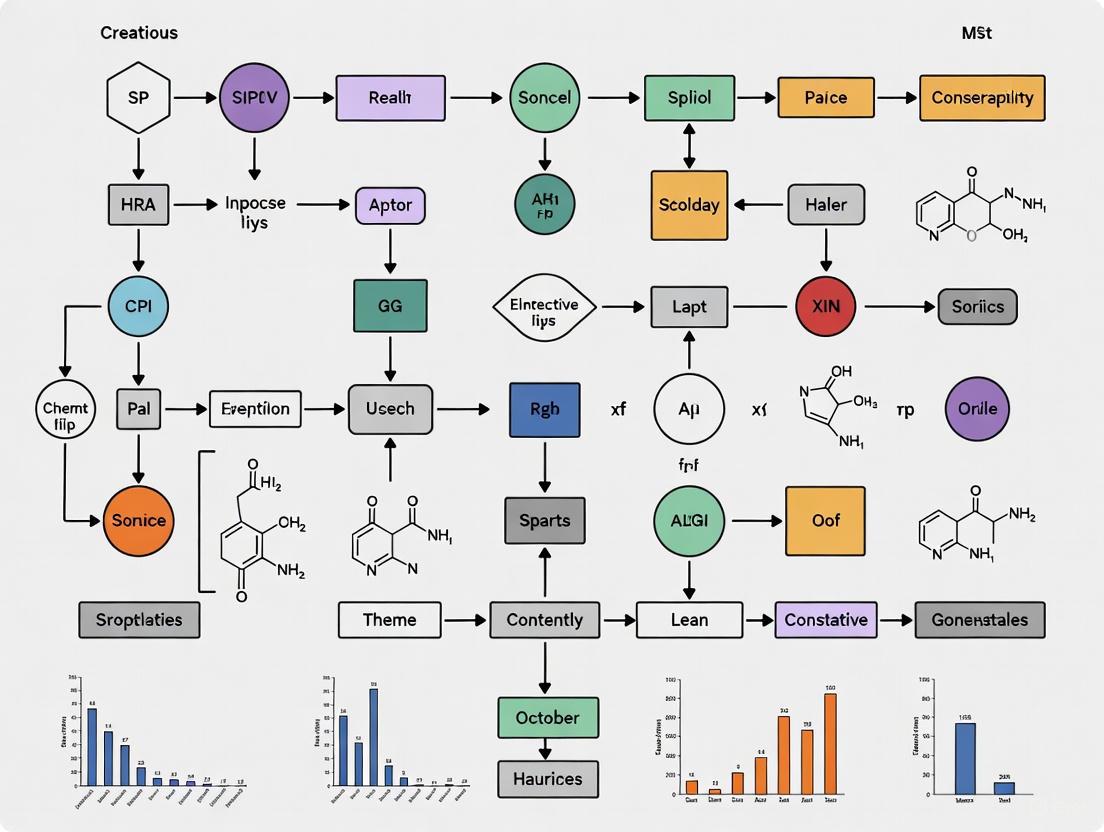

The identification of conserved targets for chemical intervention follows a systematic workflow that integrates computational genomics with experimental validation. The diagram below illustrates the key decision points and processes in this pipeline:

Cross-Species Target Identification Workflow

The experimental protocol begins with multi-species genome sequencing to generate comprehensive datasets for comparison. High-throughput sequencing technologies produce vast datasets encompassing pathogen genomes, host responses, and evolutionary trajectories across genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics [1]. For cross-species analysis, sequencing should include multiple pathogen strains/species and relevant host organisms, with particular emphasis on including both closely and distantly related species to distinguish conserved elements from lineage-specific adaptations.

Comparative genomic analysis employs tools such as the Comparative Genome Dashboard to identify functionally conserved elements across species. This involves:

- Ortholog Identification: Using protein sequence similarity and phylogenetic analysis to identify genes sharing common ancestry across species.

- Synteny Analysis: Examining conservation of gene order and genomic context to identify functionally constrained regions.

- Sequence Conservation Scoring: Quantifying evolutionary conservation through metrics like evolutionary rate (dN/dS ratios) and phylogenetic distribution.

- Functional Annotation Integration: Combining sequence data with pathway information (e.g., MetaCyc), Gene Ontology terms, and protein family databases to assign putative functions [3].

Target prioritization applies multiple filters to identify the most promising candidates for chemical screening:

- Essentiality Assessment: Integrating data from gene knockout studies to identify genes required for viability or pathogenesis.

- Selectivity Filtering: Distinguishing between targets conserved across pathogens (for broad-spectrum approaches) and those with limited host conservation (for selective toxicity).

- Druggability Prediction: Using structural information and known ligand-binding data to assess the likelihood of identifying small-molecule modulators.

High-Throughput Cross-Species Chemical Screening

Once potential targets are identified, they advance to experimental validation through chemical screening. The protocol for cross-species screening must account for differences in biology while maintaining comparability across species:

Compound Library Preparation:

- Curate diverse chemical libraries spanning multiple chemotypes and mechanism-of-action classes.

- Include known bioactive compounds as positive controls for specific target classes.

- Implement quality control through liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to verify compound identity and purity.

Multi-Species Assay Development:

- Establish comparable assay conditions for each species, optimizing for physiological relevance while maintaining cross-species comparability.

- Implement appropriate controls for species-specific background signals and assay interference.

- Use standardized readouts (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence) that function consistently across biological systems.

Primary Screening:

- Conduct concentration-response profiling for all compounds against each species in parallel.

- Include replicate measurements to assess technical variability.

- Normalize responses to species-specific positive and negative controls.

Hit Identification:

- Apply statistical methods to distinguish significant effects from background variation.

- Use cross-species activity patterns to prioritize compounds with desired selectivity profiles (e.g., broad-spectrum anti-pathogen activity or species-specific effects).

- Apply cheminformatic analysis to identify structure-activity relationships across species.

Validation and Mechanistic Studies

Following primary screening, hit compounds undergo rigorous validation to confirm activity and determine mechanisms of action:

Secondary Assay Development:

- Implement orthogonal assays to confirm primary screening results.

- Establish counterscreens to exclude compounds acting through non-specific mechanisms.

- Develop species-specific functional assays to quantify compound effects on predicted targets.

Mode-of-Action Studies:

- Apply chemical genomics approaches in model organisms, screening for genetic modifiers of compound sensitivity.

- Use biochemical methods (e.g., affinity chromatography, surface plasmon resonance) to identify direct molecular targets.

- Implement omics profiling (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to characterize compound-induced physiological changes across species.

Structural Biology Integration:

- Determine high-resolution structures of compound-target complexes when possible.

- Use comparative structural analysis to understand species-selective compound effects.

- Guide rational optimization of compound selectivity through structure-based design.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful implementation of cross-species chemical genomics requires specialized reagents and computational resources. The table below catalogues essential materials and their applications in this field:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Species Chemical Genomics

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Cross-Species Chemical Genomics |

|---|---|---|

| Comparative Genomics Platforms | Comparative Genome Dashboard, COG, Genome Properties, microTrait | Identify functionally conserved elements across species through systematic comparison of genomic features [3] [2] |

| Biological Language Models | ESM-2, ProtT5, xTrimoPGLM, genomic LLMs | Predict protein structures and functions, identify conserved domains, analyze mutational effects across species [1] |

| Pathway Databases | BioCyc, MetaCyc, KEGG | Annotate and compare metabolic and signaling pathways across multiple organisms [3] |

| Compound Libraries | Bioactive compound collections, diversity-oriented synthesis libraries, natural product extracts | Source of chemical probes for modulating conserved targets identified through comparative genomics |

| Model Organism Resources | Knockout collections, protein expression systems, transgenic lines | Validate target essentiality and compound mechanism of action across multiple species |

| Omics Profiling Technologies | RNA-seq, proteomic, metabolomic platforms | Characterize compound-induced changes across species and identify conserved response pathways |

These resources enable the systematic identification of conserved biological processes and the discovery of chemical compounds that modulate these processes across species boundaries. The integration of computational tools with experimental reagents creates a powerful pipeline for translating evolutionary conservation into therapeutic strategies [1] [3] [2].

Application to Infectious Disease Mechanisms

Influenza Virus Cross-Species Transmission

Influenza viruses provide a compelling illustration of how cross-species chemical genomics can address fundamental infectious disease mechanisms. Influenza A viruses (IAVs) demonstrate remarkable cross-species versatility, with genomic surveillance identifying infections across 12 mammalian orders and all major avian taxa [4]. This host breadth is driven by co-evolution with aquatic wild birds as ancient reservoirs and adaptive mutations in the viral hemagglutinin (HA) protein that enable flexible receptor binding [4]. The diagram below illustrates key molecular determinants of influenza cross-species transmission that can be targeted through chemical genomics:

Influenza Cross-Species Transmission Mechanism

Key molecular determinants include:

- Hemagglutinin (HA) mutations such as G228S and Q226L that alter receptor binding specificity from avian-type (α2,3-linked sialic acid) to human-type (α2,6-linked sialic acid) receptors [4].

- Neuraminidase (NA) adaptations that maintain balance with HA properties to ensure efficient viral release from infected cells.

- Polymerase complex mutations in PB2, PB1, and PA subunits that enhance replication efficiency in mammalian cells [4].

- Host factor interactions with viral proteins that differ between species, creating opportunities for host-directed therapies.

Cross-species chemical genomics approaches these challenges by identifying compounds that target:

- Conserved regions of viral proteins essential across multiple strains

- Host pathways required for viral replication across species

- Evolutionary bottlenecks that constrain viral adaptation

Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Development

The chemical genomics approach enables identification of broad-spectrum antivirals targeting conserved viral elements or host factors. For influenza, this includes:

Viral Polymerase Inhibitors:

- Target the highly conserved active site of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- Screen against polymerase complexes from multiple influenza strains and species

- Assess resistance potential through mutational analysis of conserved regions

Host-Directed Therapies:

- Identify host factors required for viral replication across multiple species

- Screen for compounds modulating these factors without excessive toxicity

- Validate using genetic knockdown in multiple cell types and species

Entry Inhibitors:

- Target conserved regions of HA or host receptors

- Assess activity against diverse viral strains with different receptor specificities

- Evaluate potential for resistance development

Data Integration and Visualization Frameworks

Effective cross-species chemical genomics requires sophisticated data integration to synthesize information across multiple dimensions. The Comparative Genome Dashboard exemplifies this approach, providing hierarchical visualization of functional capabilities across organisms [3]. The system enables researchers to:

- Survey cellular systems at multiple levels from high-level functional categories (biosynthesis, energy metabolism, transport) to specific subsystems and individual compounds or genes [3].

- Identify conserved and divergent functions through visual comparison of capability profiles across species.

- Drill down to mechanistic details including specific pathway diagrams, transporter complements, and gene annotations [3].

This visualization framework supports the core objectives of cross-species chemical genomics by highlighting functional conservation patterns that might not be apparent from sequence comparisons alone. For example, different enzyme combinations achieving the same metabolic outcome across species would be detected as conserved functional capabilities despite sequence divergence [3].

Implementation of such integrative frameworks requires:

- Standardized functional ontologies such as Gene Ontology, Pathway Ontology, and Enzyme Commission numbers to enable cross-species comparisons.

- Quantitative assessment of functional capability based on defined rules for pathway presence, transporter annotation, and GO term assignment [3].

- Interactive visualization tools that allow users to dynamically explore relationships across species and functional categories.

The power of these integrated visualization systems lies in their ability to transform comparative genomic data into testable hypotheses about conserved vulnerabilities that can be targeted with chemical compounds, effectively bridging the gap between genomic sequencing and therapeutic discovery [3] [2].

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and emerging zoonotic pathogens represent a convergent crisis, undermining a century of medical progress and posing an existential threat to global health, food security, and economic stability. This whitepaper examines this nexus through the lens of cross-species chemical genomics, a discipline critical for deciphering the complex interactions at the human-animal-environment interface. We synthesize the latest surveillance data, present advanced methodological frameworks for investigating resistance mechanisms, and highlight innovative technologies, including artificial intelligence, that are reshaping infectious disease research. The evidence compels an urgent, integrated One Health response, combining enhanced genomic surveillance, interdisciplinary collaboration, and novel therapeutic discovery to safeguard present and future health security.

The simultaneous rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and the increasing frequency of zoonotic disease emergence represents one of the most pressing challenges in modern infectious disease research. AMR threatens to reverse a century of medical progress, creating a silent pandemic that directly challenges human health, environmental integrity, and economic stability worldwide [5]. Concurrently, data indicates that the number of new infectious disease outbreaks per year has more than tripled since 1980, with a significant proportion being of zoonotic origin [6]. A foundational study of 1,407 known human pathogens found that 58% were zoonotic, and among emerging pathogens, this proportion rises to three-quarters [6].

The One Health framework is essential for understanding and addressing this convergence, as it recognizes the inextricable linkages between human, animal, and environmental health. Global ecological changes—including climate change, deforestation, intensified agriculture, and wildlife trade—have significantly elevated the risk of zoonotic disease transmission and the dissemination of resistance genes [7] [6]. This whitepaper examines this urgent need by integrating the latest epidemiological surveillance data with cutting-edge experimental approaches in chemical genomics, providing a technical roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this complex threat landscape.

Global Burden and Transmission Dynamics

The Scale of the AMR Threat

The global burden of AMR is both profound and escalating. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), AMR is associated with nearly 5 million deaths annually globally [8]. In the United States alone, more than 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur each year, resulting in over 35,000 deaths [8]. The economic burden is equally staggering, with the estimated national cost to treat infections caused by six common antimicrobial-resistant pathogens exceeding $4.6 billion annually [8]. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this situation, leading to a 20% combined increase in six key bacterial antimicrobial-resistant hospital-onset infections and a nearly five-fold increase in clinical cases of the multidrug-resistant fungus Candida auris from 2019 to 2022 [8].

Table 1: Global and National Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance

| Metric | Global Burden (2019) | U.S. Burden (2019) |

|---|---|---|

| Resistant Infections | Not Specified | 2.8 million per year |

| Deaths Associated with AMR | 4.95 million | 35,000+ |

| Deaths (Including C. diff) | Not Specified | 48,000+ |

| Economic Cost | Not Specified | >$4.6 billion annually (for 6 pathogens) |

Pathways for AMR Emergence and Zoonotic Transmission

The drivers of AMR and zoonotic pathogen emergence are deeply intertwined within the One Health continuum. Key hotspots and transmission pathways include:

- Clinical Environments: Neglected reservoirs of resistance, such as Nocardia species, continuously accumulate and diversify resistance determinants, narrowing therapeutic options and facilitating transmission across interconnected systems [5].

- Food Production Systems: Comprehensive analysis of Enterococcus faecium from China's food chain (2015-2024) shows it serves as a reservoir that accumulates and diversifies antimicrobial resistance traits, revealing a critical evolutionary pathway for AMR propagation [5].

- Open Markets: These markets, particularly prevalent in East and Southeast Asia, pose significant public health risks by facilitating zoonotic transmission and AMR spread through high human-animal interactions, poor hygiene, and unregulated antimicrobial use [9].

- Environmental Pathways: Aquatic environments, such as the Yellow River system, function as natural reservoirs and transmission highways for AMR. Surveillance data (2023-2024) confirms the widespread presence of clinically significant blaCTX-M genes, with phylogenetic evidence tracing these isolates to pig manure treatment systems [5].

- Global Trade Networks: Genomic investigations reveal that international trade functions as an evolutionary accelerator. Salmonella Rissen isolates in Shanghai show extensive contemporary gene flow, with Thailand identified as a primary source, enabling the widespread distribution of high-risk plasmids harboring up to 15 resistance genes [5].

Table 2: Key Frontline Evidence of AMR and Zoonotic Risks from One Health Surveillance

| Frontline | Key Evidence | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Nocardia isolates developing resistance to first-line trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. | Narrowing therapeutic options in healthcare settings. |

| Food Chain | E. faecium with elevated multidrug resistance rates in China's food chain. | Food chain acts as a silent amplifier of resistance traits. |

| Environment | blaCTX-M genes in Yellow River isolates genetically linked to pig manure. | Waterways disseminate resistance from agricultural sources. |

| Community | Asymptomatic food workers showing 41.9% MDR Salmonella carriage. | Human populations act as asymptomatic AMR bridges. |

| Globalization | S. Rissen plasmids carrying up to 15 resistance genes via international trade. | Global commerce accelerates pan-drug-resistant pathogen spread. |

Chemical Genomics: A Methodological Framework for Cross-Species Investigation

Chemical genomics provides a powerful systems biology framework for deciphering the complex networks governing cellular functions and pathogen responses to therapeutic interventions. This approach is particularly suited for studying AMR in zoonotic pathogens, as it enables high-throughput analysis of gene-chemical interactions across species barriers.

Core Protocol: CRISPRi Chemical Genomics Screening

The following methodology, adapted from a seminal study on Acinetobacter baumannii, outlines a robust pipeline for probing essential gene function and antibiotic interactions in bacterial pathogens [10].

1. Library Design and Construction:

- Objective: Target putatively essential genes for knockdown without complete gene deletion.

- Procedure:

- Compile a library of putatively essential genes from prior transposon sequencing (Tn-seq) data.

- For each target gene, design and clone multiple single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs): four "perfect-match" sgRNAs and ten "mismatch" sgRNAs with single-base variations to titrate knockdown efficacy.

- Include a large set (e.g., 1000) of non-targeting control sgRNAs to establish a baseline.

- Clone the sgRNA library into an appropriate vector containing an inducible dCas9 system for the target pathogen.

2. Pooled Competition Fitness Assays:

- Objective: Measure the phenotypic impact of gene knockdown under chemical stress.

- Procedure:

- Grow the pooled CRISPRi library under conditions that induce knockdown.

- Split the culture and expose to sublethal concentrations of target chemicals (antibiotics, heavy metals, etc.). Maintain an unexposed control.

- Incubate for a sufficient number of generations to allow for competitive growth while preserving library diversity.

- Harvest genomic DNA from both treated and control samples.

3. Sequencing and Phenotype Scoring:

- Objective: Quantify the fitness of each knockdown strain under treatment.

- Procedure:

- Amplify and sequence the sgRNA spacer regions from all samples using high-throughput sequencing.

- For each gene, calculate a Chemical-Gene (CG) score as the median log2 fold change (medL2FC) in abundance of its perfect-match sgRNAs in the treated sample versus the control.

- Apply statistical thresholds (e.g., medL2FC ≥ |1| with p < 0.05) to identify significant interactions. A negative CG score indicates knockdown sensitized the strain to the chemical.

4. Data Analysis and Network Construction:

- Objective: Derive biological insights from the interaction dataset.

- Procedure:

- Perform functional enrichment analysis (e.g., using STRING database) on genes with many negative CG scores to identify pathways critical for chemical resistance.

- Construct essential gene networks by correlating CG score profiles across all conditions, linking poorly characterized genes to well-understood biological processes.

- Integrate phenotypic data with chemoinformatic analysis of compound structures to distinguish modes of action and suggest inhibitor targets.

Diagram 1: CRISPRi chemical genomics screening workflow.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of the above protocol relies on a suite of specialized research reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemical Genomics Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Inducible dCas9 System | Enables targeted gene knockdown without double-strand breaks. | Knockdown of essential genes in A. baumannii for fitness studies [10]. |

| sgRNA Library | Pools of guide RNAs for high-throughput, parallel gene perturbation. | Screening 406 essential genes against 45 chemical stressors [10]. |

| Non-Targeting sgRNAs | Controls for off-target effects and establishes baseline fitness. | 1000 non-targeting guides used to normalize screen data [10]. |

| Chemical Compound Libraries | Diverse collections of antibiotics, inhibitors, and molecules. | Profiling gene interactions with clinical antibiotics and heavy metals [10]. |

| STRING Database | Tool for functional enrichment analysis of gene sets. | Identifying lipooligosaccharide transport as key for chemical resistance [10]. |

Technological Innovations: AI and Advanced Surveillance

Artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing the fight against AMR by enabling the extraction of sophisticated insights from complex, large-scale datasets [11]. Key applications directly relevant to zoonotic AMR research include:

- Sepsis Prediction: AI models like COMPOSER, which integrates electronic health record data, have demonstrated a 17% relative decrease in in-hospital mortality from sepsis by enabling earlier, more targeted antibiotic intervention [11].

- Bacterial Identification: Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) applied to Raman spectroscopy data can rapidly identify bacterial species and their resistance profiles from minimal samples, bypassing time-consuming culture steps [11].

- Antibiotic Discovery: AI models can rapidly screen vast chemical libraries in silico to identify novel antibiotic candidates. This has led to the discovery of new compounds effective against multidrug-resistant pathogens like Acinetobacter baumannii [11].

- Genomic Surveillance: Machine learning applied to whole-genome sequencing data can uncover novel resistance mechanisms and predict resistance phenotypes from genomic signatures, enhancing real-time public health surveillance and outbreak response [11].

The evidence is unequivocal: antimicrobial resistance and emerging zoonotic pathogens constitute a metastasizing emergency that compounds in severity across interconnected biological and social systems [5]. The "Act Now" imperative championed by global health bodies is both a warning and a call to action for the research community [5].

The path forward requires a reinforced commitment to the One Health paradigm, operationalized through:

- Integrated Surveillance: Building proactive, early-warning networks that seamlessly integrate human, animal, and environmental monitoring to track resistance and pathogen evolution [5] [7].

- Cross-Disciplinary Research: Leveraging chemical genomics, AI, and structural biology to deconstruct transmission mechanisms and identify novel therapeutic targets [10] [11].

- Global Solidarity and Governance: Reinvesting in multilateral cooperation and knowledge sharing to address the transnational nature of AMR and zoonotic threats, countering the vulnerabilities created by nationalistic policies [6].

The application of cross-species chemical genomics is foundational to this mission, providing the mechanistic understanding required to develop the next generation of diagnostics, therapeutics, and preventive strategies. By transforming political commitments into accountable, coordinated interventions, the scientific community can protect our present and secure a healthier future.

The integration of chemical-genomic interactions with the complex dynamics of host-pathogen relationships represents a transformative frontier in infectious disease research. Cross-species chemical genomics provides a powerful framework for systematically understanding how small molecules affect biological systems across different species, revealing fundamental insights into drug mechanisms of action (MoA), host-pathogen interactions, and evolutionary conservation of drug targets [12] [13] [14]. This approach leverages the genetic tractability of model organisms while extending findings to clinically relevant pathogens and hosts, enabling more predictive drug discovery and development.

At its core, this field investigates how chemical perturbations interact with genetic backgrounds to influence phenotypic outcomes across species boundaries. The theoretical foundation rests on the principle that functional modules and biological pathways are more evolutionarily conserved than individual gene-drug interactions [12]. This modular conservation enables meaningful extrapolation of drug effects even between distantly related species, providing critical insights for infectious disease therapeutics and the development of host-directed therapies [15] [13].

Key Methodological Approaches in Cross-Species Chemical Genomics

Experimental Design Frameworks

Cross-species chemical genomics employs systematic approaches to map gene-chemical interactions across multiple organisms. The core methodology involves screening comprehensive mutant libraries against chemical compounds and quantitatively analyzing fitness profiles [12] [14].

Library Design Considerations:

- Loss-of-function libraries: Gene knockout or knockdown collections (e.g., haploid deletion mutants)

- Gain-of-function libraries: Systematic gene overexpression systems

- Controlled genetic variation: CRISPR-based modulation (CRISPRi, CRISPRa) of essential and non-essential genes

- Natural genetic variation: Utilization of diverse natural isolates to capture population-level diversity [14]

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Pooled Competitive Growth Chemogenomic Screening

This protocol enables genome-wide assessment of gene-drug interactions in a single experiment through barcode sequencing [16] [14].

Step 1: Library Preparation and Compound Treatment

- Grow pooled mutant library to mid-exponential phase in appropriate medium

- Split culture into treatment (sub-inhibitory drug concentration) and control (no drug) conditions

- Incubate for predetermined generations (typically 8-12)

- Harvest cells and isolate genomic DNA or plasmid pools

Step 2: Barcode Amplification and Sequencing

- Amplify unique molecular barcodes from each sample using PCR with indexing primers

- Purify amplified products and quantify by qPCR

- Pool equimolar amounts of each library for multiplexed sequencing

- Sequence on appropriate platform (Illumina recommended)

Step 3: Data Analysis and Hit Identification

- Map sequencing reads to reference barcode list using alignment tools

- Calculate abundance ratios (treatment vs. control) for each mutant

- Normalize data using robust statistical methods (e.g., median normalization)

- Identify significant hits using appropriate thresholds (typically >2-fold change, FDR <5%)

Protocol 2: Cross-Species Halo Assay for Compound Bioactivity Screening

This method provides rapid assessment of compound bioactivity across multiple species [12].

Step 1: Agar Plate Preparation

- Prepare appropriate agar medium for target species

- Pour plates to uniform depth and allow to solidify

- Create lawn of indicator organism (0.1-0.2 OD600)

Step 2: Compound Application and Incubation

- Apply compounds to sterile filter paper disks or directly to agar

- Incubate at optimal growth temperature for 16-48 hours

- Measure inhibition zones (halos) using calipers or automated imaging

Step 3: EC50 Prediction

- Measure halo diameters across compound concentration series

- Fit dose-response curves using four-parameter logistic regression

- Calculate predicted EC50 values from curve parameters

- Compare relative sensitivity between species

Quantitative Profiling and Data Analysis

Chemical-Genetic Interaction Scoring

The quantitative analysis of chemical-genetic interactions relies on robust fitness metrics that enable cross-species comparisons. The drug score (D-score) system provides a standardized approach for quantifying gene-compound interactions [12].

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Chemical-Genetic Profiling

| Metric | Calculation Method | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-score | Deviation from expected growth (observed - expected) | Negative = sensitivity; Positive = resistance | Cross-species comparison of gene-drug interactions |

| Fitness Defect | log2(treatment/control abundance) | Values <0 indicate fitness cost; >0 indicate benefit | Pooled mutant screens (e.g., Bar-seq) |

| Interaction Score | ε = (Wxy - WxW_y) | Positive = alleviating interaction; Negative = aggravating interaction | Genetic interaction networks |

| EC50 Ratio | EC50species1/EC50species2 | Values >1 indicate species2 more sensitive | Cross-species potency comparisons |

Cross-Species Conservation Analysis

The conservation of drug responses across species follows distinct patterns that inform target engagement and mechanism of action.

Table 2: Conservation Patterns in Cross-Species Chemical Genomics

| Conservation Level | Key Features | Experimental Evidence | Implications for Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Module-Level Conservation | Functional pathways show conserved drug sensitivity | Compound-functional module relationships conserved between S. cerevisiae and S. pombe [12] | Enables predictive MoA analysis across species |

| Gene-Level Divergence | Individual gene-drug interactions show limited conservation | Only 31% of resistance-enhancing genes overlap between AMPs [16] | Complicates direct gene-to-gene extrapolation |

| Target Conservation | Essential drug targets show highest conservation | Overexpression of drug target confers cross-species resistance [14] | Supports target-based drug development approaches |

| Physicochemical Determinants | Bioactivity correlates with compound properties | Bioactive compounds show higher ClogP, lower PSA [12] | Informs compound selection for cross-screening |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Cross-Species Chemical Genomics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Organism Mutant Libraries | S. cerevisiae deletion collection, S. pombe deletion library, E. coli Keio collection | Systematic screening of gene-drug interactions | Ortholog mapping essential for cross-species analysis [12] [14] |

| Chemical Libraries | NCI Diversity Set, NCI Mechanistic Set, Custom natural product libraries | Compound bioactivity screening across species | Structural diversity enhances discovery potential [12] |

| CRISPR Modulation Systems | CRISPRi knockdown libraries, CRISPRa activation pools | Essential gene targeting, dose-response studies | Enables bacterial essential gene screening [14] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | ECOdrug, SeqAPASS, Chemogenomic profilers | Evolutionary conservation analysis, target prediction | Critical for cross-species data integration [13] |

| Reporting Plasmids | Barcoded overexpression vectors, Fluorescent reporter constructs | Gene dosage studies, pathway activation reporting | Enables multiplexed competitive growth assays [16] [14] |

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

Cross-Species Chemogenomic Screening Workflow

Cross-Species Chemogenomic Screening

Chemical-Genetic Interaction Interpretation

Chemical-Genetic Interaction Mechanisms

Host-Pathogen Interaction Signaling Network

Host-Pathogen Interaction Network

Applications in Infectious Disease Research

Mechanism of Action Deconvolution

Cross-species chemical genomics enables systematic identification of drug targets and mechanisms of action through several complementary approaches [14]:

Haploinsufficiency Profiling (HIP)

- Applied in diploid organisms (e.g., yeast)

- Heterozygous deletion mutants show increased sensitivity when target gene is diluted

- Particularly effective for identifying essential gene targets

Homozygous Profiling (HOP)

- Uses complete gene deletions in haploid organisms

- Identifies resistance mechanisms and parallel pathways

- Reveals complex cellular responses to chemical perturbation

Chemical-Genetic Similarity Profiling

- Compares drug signatures across mutant libraries

- Implements "guilt-by-association" approach

- Groups compounds with similar mechanisms based on profile correlation [12] [16]

Resistance Mechanism Mapping

The comprehensive mapping of resistance determinants reveals both conserved and compound-specific mechanisms [16]:

Table 4: Resistance Mechanisms Identified Through Chemical Genomics

| Resistance Category | Genetic Elements | Cross-Resistance Potential | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efflux Systems | ABC transporters, MFS pumps, RND family | High for structurally similar compounds | Combination therapies with efflux inhibitors |

| Target Modification | Target gene mutations, overexpression | Target-specific | Higher barrier to resistance with combination therapies |

| Metabolic Bypass | Alternative pathway activation, precursor supplementation | Pathway-specific | Identifies compensatory pathways for targeting |

| Cell Envelope Alteration | Membrane composition genes, cell wall modifiers | Broad-spectrum | Challenges for membrane-targeting compounds |

Host-Directed Therapeutic Development

Chemical genomics approaches enable identification of host factors essential for pathogen replication and virulence [15] [17]:

Genome-wide CRISPR Screens

- Identification of host dependency factors

- Revelation of pathogen manipulation mechanisms

- Discovery of novel host-directed therapy targets

Multi-omics Integration

- Combination of chemogenomic data with transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles

- Construction of network models revealing regulatory nodes

- Identification of critical host-pathogen interfaces [18]

Cross-Species Target Conservation Analysis

- Assessment of drug target evolutionary conservation

- Prediction of off-target effects across species

- Informed selection of animal models for preclinical testing [13]

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of chemical-genomics and host-pathogen dynamics is rapidly evolving with several transformative technologies enhancing research capabilities:

Large Language Models for Biological Sequence Analysis

- Protein language models for predicting pathogen virulence factors

- Genomic language models for identifying resistance determinants

- Multimodal integration of chemical and biological data [19]

Advanced Microphysiological Systems

- Organoid and organ-on-chip technologies for host-pathogen interaction modeling

- Physiologically relevant microenvironments bridging in vitro and in vivo systems

- Incorporation of mechanical, chemical, and immune gradients [18]

Targeted Protein Degradation Platforms

- PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) for infectious disease applications

- Selective elimination of microbial proteins or host factors critical for infection

- Recruitment of E3 ligases to target pathogen essential factors [15] [20]

Single-Cell Multi-omics Profiling

- High-resolution analysis of host-pathogen interactions at single-cell level

- Identification of heterogeneous cellular responses to infection

- Spatial transcriptomics for tissue microenvironment characterization [15]

These advanced approaches, integrated within a cross-species chemical genomics framework, promise to accelerate therapeutic discovery and enhance our fundamental understanding of infectious disease mechanisms.

The One Health framework is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals, and ecosystems [21]. It recognizes that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment are closely linked and interdependent [21]. This collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach operates at local, regional, national, and global levels with the goal of achieving optimal health outcomes by recognizing the interconnections between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment [22]. The approach has gained significant importance in recent years because many factors have changed interactions between people, animals, plants, and our environment, including growing human populations expanding into new geographic areas, changes in climate and land use, and increased movement of people, animals, and animal products through international travel and trade [22].

The One Health approach is particularly relevant for addressing complex global health challenges such as emerging infectious diseases, antimicrobial resistance, and food safety [21]. The interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health creates a crucial foundation for infectious disease research, especially when integrated with advanced approaches like cross-species chemical genomics. This integration enables researchers to systematically study how chemical compounds affect biological systems across different species, providing valuable insights for drug discovery and understanding disease mechanisms [23] [12]. The application of this combined framework allows for a more comprehensive understanding of disease transmission, pathogenesis, and therapeutic interventions across the human-animal-environment interface.

Quantitative Evidence Supporting the One Health Approach

A scoping review of quantitative outcomes following the adoption of a One Health approach provides substantial evidence of its benefits [24]. This review systematically identified and analyzed 85 studies that described monetary and non-monetary outcomes, revealing that the majority reported positive or partially positive results [24]. The health issues addressed in these studies were diverse, with rabies and malaria being the top two biotic health issues, and air pollution as the top abiotic health concern [24]. The collaborations most commonly reported were between human and animal disciplines (42 studies) and human and environmental disciplines (41 studies), with interventions frequently including vector control and animal vaccination programs [24].

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of One Health Interventions from 85 Studies

| Outcome Category | Specific Metrics Used | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Monetary Outcomes | Cost-benefit ratios, Cost-utility ratios | Positive economic returns reported for interventions like animal vaccination and integrated surveillance systems [24]. |

| Non-Monetary Outcomes | Disease frequency measurements, Disease burden metrics (e.g., DALYs) | Significant reductions in disease incidence and burden achieved through cross-sectoral interventions [24]. |

| Health Issues Addressed | Rabies, Malaria, Air pollution | Top priorities successfully managed using One Health approaches [24]. |

| Collaboration Types | Human-animal (42 studies), Human-environment (41 studies) | Most common interdisciplinary partnerships formed [24]. |

The quantitative evidence demonstrates that One Health approaches can achieve measurable success in diverse contexts. Monetary outcomes were commonly expressed as cost-benefit or cost-utility ratios, while non-monetary outcomes were described using disease frequency or disease burden measurements such as Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) [24]. These findings provide tangible evidence for policy-makers and funding agencies regarding the value of cross-sectoral collaborations, which is essential for justifying the initial investments required for such integrated approaches [24].

Cross-Species Chemical Genomics in One Health Research

Fundamental Concepts and Methodologies

Cross-species chemical genomics represents a powerful methodological platform for drug discovery and mode of action studies within the One Health framework. This approach involves screening libraries of genetic mutants across multiple species against diverse chemical compounds to derive quantitative drug scores (D-scores) that identify mutants sensitive or resistant to particular compounds [12]. The core principle is that comparing drug fitness profiles across species allows for more accurate prediction of a compound's mode of action and provides evolutionary insights into drug response conservation [12]. Research has demonstrated that compound-functional module relationships are more conserved than individual compound-gene interactions between species, highlighting modularity as a key aspect of drug response conservation [12].

The experimental workflow typically begins with screening compound libraries against model organisms using high-throughput assays that measure growth inhibition [12]. For example, in a study screening 2,957 compounds from the National Cancer Institute Diversity and Mechanistic Sets against two yeast species (Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe), researchers identified 270 bioactive compounds, 132 of which had effects in both species [12]. Subsequent chemogenomic profiling involves screening these bioactive compounds against collections of deletion mutants arrayed in agar plates, using algorithms designed to quantitatively assign genetic interactions based on colony size [12]. This generates comprehensive drug scores indicating compound effects on individual mutations.

Application to Veterinary Drug Discovery from Herbal Medicines

A significant application of cross-species chemogenomics in One Health is the development of novel veterinary drugs from herbal medicines [23]. Researchers have created a cross-species chemogenomic screening platform that systematically analyzes traditional herbal remedies using modern computational and experimental approaches [23]. This platform involves multiple stages: first, a cross-species drug-likeness evaluation approach screens lead compounds in veterinary medicines based on critically examined pharmacology and text mining; second, a specific cross-species target prediction model infers drug-target connections; third, heterogeneous network convergence and modularization analysis explores multiple target interference effects of veterinary medicines [23].

This approach was exemplified through the study of Erchen decoction, a traditional Chinese formulation for treating bovine pneumonia composed of Pinellia ternata, Tangerine Peel, Poria cocos, and Glycyrrhiza uralensis (Licorice) [23]. The methodology included calculating drug-likeness (DL) using Tanimoto similarity between herbal compounds and the average molecular properties of all veterinary drugs in the FDA database, with ingredients scoring DL ≥ 0.15 considered candidate bioactive molecules [23]. This integrated strategy allows for the systematization of traditional knowledge of veterinary medicine and its application to developing new drugs for animal diseases, representing a practical implementation of One Health principles bridging traditional medicine, veterinary science, and modern drug discovery [23].

Experimental Protocols in Cross-Species Chemical Genomics

Protocol 1: Cross-Species Chemogenomic Screening

Objective: To identify conserved drug responses and mechanisms of action across species using chemogenomic profiling [12].

Materials:

- Model Organisms: Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe deletion mutant collections [12]

- Compound Library: 2,957-member National Cancer Institute Diversity and Mechanistic Sets [12]

- Growth Media: Appropriate agar and liquid media for each species

- Automated Imaging System: For high-throughput quantification of colony sizes [12]

Procedure:

- Primary Compound Screening:

- Array deletion mutants of both species on agar plates using robotic pinning tools [12]

- Apply compounds at varying concentrations using a high-throughput halo assay [12]

- Incubate plates under optimal growth conditions for each species

- Measure inhibition zones (halos) to determine bioactive compounds and predict EC₅₀ values [12]

Chemogenomic Profiling:

- Select bioactive compounds for detailed analysis against comprehensive deletion libraries [12]

- Grow deletion mutants in the presence of sub-inhibitory compound concentrations

- Quantify colony sizes after specified incubation periods

- Calculate quantitative drug scores (D-scores) using established algorithms that compare observed growth to expected growth under a neutral model [12]

Data Analysis:

- Identify sensitive (D-score < 0) and resistant (D-score > 0) mutants for each compound [12]

- Generate compound-genetic interaction profiles by combining D-scores across all mutants

- Compare profiles between species to identify conserved and species-specific responses

- Cluster compounds with similar interaction profiles to infer common mechanisms of action [12]

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Cross-Species Chemical Genomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Haploid Deletion Mutant Libraries | Comprehensive collections of gene deletion strains for chemogenomic screening [12] | S. cerevisiae: ~4,800 mutants; S. pombe: ~3,000 mutants [12] |

| NCI Compound Collections | Structurally diverse chemical libraries for primary screening [12] | Diversity Set: Structural diversity; Mechanistic Set: Tested in human tumor cell lines [12] |

| Drug-Likeness Evaluation Metrics | Computational assessment of compound suitability as drug candidates [23] | 1,533 molecular descriptors; Tanimoto similarity calculation; DL threshold ≥0.15 [23] |

| Chemical-Genetic Interaction Scoring | Quantitative measurement of compound effects on mutants [12] [16] | D-scores based on colony size comparisons; Sensitivity (D-score <0); Resistance (D-score >0) [12] |

Protocol 2: Chemical-Genetic Mapping of Antimicrobial Peptides

Objective: To comprehensively map genetic determinants of bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) using chemical-genetic approaches [16].

Materials:

- E. coli ORF Overexpression Library: Pooled plasmid collection overexpressing all ~4,400 E. coli genes [16]

- AMP Panel: 15 structurally and functionally diverse antimicrobial peptides [16]

- Growth Monitoring System: For sensitive competition assays (e.g., spectrophotometer, deep sequencing capability) [16]

Procedure:

- Chemical-Genetic Screen:

- Grow E. coli cells carrying the pooled plasmid library in presence and absence of each AMP at sub-inhibitory concentrations (concentration that increases doubling time by 2-fold) [16]

- Culture for approximately 12 generations to allow selection effects to manifest [16]

- Isolate plasmid pool from each selection condition

- Determine relative abundance of each plasmid by deep sequencing [16]

Interaction Scoring:

- Calculate chemical-genetic interaction scores (fold-change values) by comparing plasmid abundances in presence vs. absence of each AMP [16]

- Identify statistically significant sensitivity-enhancing genes (decreased abundance) and resistance-enhancing genes (increased abundance) [16]

- Validate hits through minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) measurements on selected overexpression strains [16]

Cross-Resistance Analysis:

Integration of One Health and Chemical Genomics for Infectious Disease Research

Conceptual Framework and Workflow Integration

The integration of One Health principles with cross-species chemical genomics creates a powerful framework for infectious disease research and therapeutic development. This integrated approach recognizes that infectious diseases operate at the human-animal-environment interface and that understanding disease mechanisms and therapeutic interventions requires studying these connections across species boundaries [21] [12]. The conceptual framework begins with the recognition that human, animal, and ecosystem health are inextricably linked, and that addressing health challenges requires collaborative efforts across multiple disciplines and sectors [22] [21].

The workflow integration involves several key stages: First, disease surveillance within a One Health framework identifies emerging health threats at the human-animal-environment interface [22] [25]. Second, cross-species chemical genomic approaches are applied to understand disease mechanisms and identify potential therapeutic targets across species [23] [12]. Third, drug discovery and development leverage insights from chemical-genetic interactions to design compounds with desired activity profiles [23] [16]. Finally, intervention implementation and monitoring occur within the same One Health framework, assessing impacts on human, animal, and environmental health [24].

Application to Infectious Disease Modeling and Intervention

The integrated One Health-chemical genomics framework has significant applications in infectious disease modeling and intervention development. Mathematical modeling within a One Health framework prioritizes collaborative approaches, including multi-sectoral models, data integration, and risk assessment tools [25]. These models incorporate data from human, animal, and environmental surveillance to predict disease spread and evaluate intervention strategies [25]. When combined with chemical-genomic insights into pathogen vulnerabilities and drug mechanisms, these models become powerful tools for designing targeted interventions with minimal cross-resistance and optimal efficacy across species [16].

Recent research applications demonstrate the utility of this integrated approach. Studies have focused on diverse health threats including avian influenza, Lyme disease, toxoplasmosis, and antimicrobial resistance [25]. For example, machine learning approaches integrating environmental, socioeconomic, and vector factors have been used to project Lyme disease risk, while studies of avian influenza spillover into poultry have examined environmental influences and biosecurity protections [25]. In each case, the combination of One Health surveillance with molecular insights from chemical-genomic approaches provides a more comprehensive understanding of disease dynamics and potential intervention points.

Visualization of Chemical-Genetic Interactions in Cross-Species Experiments

Experimental Workflow for Cross-Species Chemogenomic Screening

Understanding the experimental workflow for cross-species chemogenomic screening is essential for implementing this approach within One Health infectious disease research. The following diagram illustrates the key stages in this process, from compound screening to data integration:

Data Integration and Analysis Framework

The interpretation of chemical-genetic interaction data requires careful analysis and integration across multiple dimensions. The following diagram outlines the key analytical steps for deriving biological insights from cross-species chemogenomic data:

The integration of the One Health framework with cross-species chemical genomics represents a transformative approach to infectious disease research and therapeutic development. By recognizing the fundamental interconnections between human, animal, and environmental health [22] [21], and leveraging advanced methodologies for studying chemical-genetic interactions across species [23] [12], this integrated approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of disease mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. The quantitative evidence supporting One Health interventions [24], combined with the powerful insights from chemical-genomic profiling [12] [16], creates a robust foundation for addressing complex global health challenges.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this integrated framework offers practical methodologies for identifying therapeutic targets, understanding compound modes of action, and designing interventions with minimal cross-resistance [16]. The experimental protocols and analytical approaches outlined in this guide provide a roadmap for implementing these strategies in infectious disease research. As the field continues to evolve, the combination of One Health principles with chemical-genomic technologies will play an increasingly important role in promoting global health security and addressing emerging health threats at the human-animal-environment interface [21] [25].

Historical Precedents and Evolutionary Insights from Comparative Immunology

Comparative immunology represents a foundational discipline that examines the immune systems across diverse species, providing critical evolutionary context for understanding immune function and dysfunction. The field officially emerged as a recognized scientific discipline around 1977, though its conceptual origins trace back to Élie Metchnikoff's pioneering 19th-century studies of phagocytosis in invertebrates [26]. These early observations established the fundamental dichotomy between cellular and humoral immunity that still underpins modern immunology. The core premise of comparative immunology investigates how immune systems have evolved across the tree of life, with invertebrate models representing early innate systems and vertebrates possessing both innate and adaptive immunity [26].

This evolutionary perspective provides invaluable insights for contemporary infectious disease research, particularly in the context of cross-species chemical genomics. By understanding the conservation and diversification of immune pathways across species, researchers can identify critical regulatory nodes amenable to therapeutic intervention, develop animal models that better recapitulate human immune responses, and predict zoonotic transmission potential through shared immunological mechanisms. The integration of comparative immunology with chemical genomics represents a powerful approach for addressing the growing threat of emerging infectious diseases through the lens of evolutionary medicine.

Historical Foundations and Key Developments

The historical development of comparative immunology reveals a progressive elucidation of immune system evolution, characterized by key discoveries that have shaped our current understanding of host-pathogen interactions across species.

Metchnikoff's Legacy and the Dawn of Cellular Immunology

Élie Metchnikoff's prescient experiments in the 19th century established the fundamental principles of cellular immunity through his observations of phagocytosis in invertebrate models [26]. This work not only splintered immunology into its two main components—cellular and humoral—but also established the value of comparative approaches for understanding universal immune mechanisms. Metchnikoff recognized that studying simpler organisms could reveal conserved biological processes relevant to more complex vertebrates, a perspective that continues to inform modern comparative immunology.

The formal establishment of comparative immunology as a discipline gained momentum with the creation of the journal Developmental and Comparative Immunology in 1977 and the formation of the International Society of Developmental and Comparative Immunology (ISDCI) [26]. These institutional developments provided dedicated platforms for disseminating research on immune system evolution and facilitated collaboration among researchers investigating diverse model systems. National societies subsequently emerged in Japan, Italy, Germany, and sporadically in the United States, further consolidating the field's scientific identity.

Conceptual Evolution: From "One Medicine" to "One Health"

A significant conceptual advancement in comparative immunology has been the formal adoption of the "One Medicine - One Health" paradigm, which emphasizes the mutual interest and benefit of interdisciplinary cooperation between human and animal medicine [27]. This perspective recognizes that combining the respective expertise of physicians, veterinarians, and other health professionals enables comparative studies relevant to both human and animal health. Journals such as Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (CIMID) explicitly aim to respond to this concept by providing a venue for scientific exchange at the human-animal health interface [27].

The operationalization of this paradigm has shifted the focus of comparative immunology toward applied veterinary and human medicine, particularly regarding zoonotic pathogens. This emphasis reflects the growing recognition that approximately 60% of emerging infectious diseases in humans originate from animals, necessitating a comparative understanding of immune mechanisms across species boundaries. The integration of ecological context with immunological function has further enriched the field, giving rise to "ecological immunology"—the study of immune variation in natural settings [28] [29].

Evolutionary Patterns in Immune System Components

Evolutionary analysis of immune genes reveals remarkably consistent evidence of selection, modification, and diversification across the tree of life, with parasites serving as a key selective force driving immune adaptation [28].

Deep Evolutionary Conservation of Immune Mechanisms

Recent research has demonstrated surprising conservation of fundamental immune mechanisms across distantly related species. One striking example comes from the MR1/MAIT cell system, which functions as an evolutionarily conserved molecular alarm system present in multiple species [30]. This system enables the presentation of molecules from diverse bacteria and fungi, alerting the immune system to microbial invasion. The conservation of this mechanism across humans, cows, mice, sheep, and pigs enables meaningful comparative studies, although significant quantitative differences exist—humans possess the largest population of MAIT cells (tenfold greater than other species), while pigs show no obvious MAIT cell population despite encoding the MR1 protein [30].

The IL-12 family of cytokines and their receptors provides another compelling example of evolutionary conservation with functional diversification. Phylogenetic analysis across 405 animal species has revealed that IL-12 receptor subunits originated prior to the mollusk era (514-686.2 million years ago), while ligand subunits p19/p28 emerged later during the mammalian and avian epoch (180-225 million years ago) [31]. This pattern suggests that receptor architectures predated their contemporary ligands, with subsequent co-evolution shaping specific immune functions. Structural characterization has identified three evolutionarily invariant signature motifs within the fibronectin type III (fn3) domain that are essential for receptor-ligand interface stability [31].

Evolutionary Trajectories of Specific Immune Components

Table 1: Evolutionary Origins and Functions of IL-12 Family Components

| Component | Evolutionary Origin | Key Functions | Therapeutic Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-12Rs | Pre-mollusk era (514-686.2 Mya) [31] | Signal transduction for IL-12 family cytokines | Conservation enables cross-species therapeutic targeting |

| Ligand subunits p19/p28 | Mammalian/avian epoch (180-225 Mya) [31] | Formation of IL-23 (p19+p40) and IL-27 (p28+EBI3) | Targeted by biologics for autoimmune diseases |

| EBI3 subunit | Conserved across multiple species [31] | Component of IL-27, IL-35, and IL-39 | Role in both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses |

| fn3 domain motifs | Ultra-conserved across evolution [31] | Maintain receptor-ligand interface stability | Candidate therapeutic epitopes for intervention |

The evolutionary patterns observed in immune gene families reflect both deep conservation and lineage-specific adaptations. Immune genes consistently show evidence of positive selection, particularly in regions involved in pathogen recognition, reflecting the continuous co-evolutionary arms race between hosts and pathogens [28]. This dynamic evolutionary process creates a natural repository of immunological solutions to pathogen challenges, providing a rich resource for identifying novel therapeutic approaches through comparative analysis.

Modern Research Approaches and Methodologies

Contemporary comparative immunology employs sophisticated genomic, phylogenetic, and experimental approaches to unravel the evolutionary history and functional diversity of immune systems.

Comparative Genomics and Phylogenetic Analysis

Advanced genomic techniques have revolutionized comparative immunology by enabling systematic analysis of immune gene evolution across hundreds of species simultaneously. A comprehensive study of IL-12 family ligands and receptors across 405 species exemplifies this approach, utilizing phylogenetic reconstruction, synteny analysis, and sequence alignment to delineate evolutionary trajectories and functional diversification [31]. This methodology involves:

- Genome Acquisition and Quality Control: Sourcing genomes from databases such as NCBI, Ensembl, CNCB, and Macgenome, with quality assessment using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) analysis [31].

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Identifying single-copy orthologous sequences, alignment using MAFFT, trimming with trimAl, and maximum-likelihood phylogeny construction using IQtree with 1000 bootstrap replicates [31].

- Sequence Identification and Analysis: Standardizing genome and annotation files, extracting longest isoforms, and employing batch processing of coding sequences and protein sequences [31].

These methods enable researchers to identify evolutionarily conserved regions that represent critical functional domains, as well as lineage-specific adaptations that reflect particular ecological pressures or life history strategies.

The Immunogram: A Multiparametric Approach to Immune Analysis

A novel methodological development in comparative immunology is the "Immunogram"—a systematic approach for processing multiparametric immunological data that represents a subject's immunological fingerprint [32]. This method involves:

- Comprehensive Immune Profiling: Analyzing lymphocyte subpopulations using monoclonal antibodies with multiple fluorochromes to measure various lymphocyte subsets with different functions and activation states [32].

- Database Integration: Creating a reference database of immunological parameters from approximately 8,000 subjects, enabling comparative analysis [32].

- Percentile Rank Calculation: Calculating the percentile rank of a subject's values compared to age-matched references in the database, visualized in a comprehensive graph [32].

- Dynamic Monitoring: Superimposing fingerprints from the same subject at different time points to produce a dynamic picture of immune status, particularly useful for tracking responses to therapeutic interventions [32].

This systematic approach facilitates the identification of immunological patterns across species and conditions, supporting the translation of basic immunological findings into clinically relevant applications.

Applications in Infectious Disease Research and Therapeutic Development

The insights gained from comparative immunology have profound implications for understanding infectious disease mechanisms and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Predicting Zoonotic Transmission and Emergence

Comparative genomics of zoonotic pathogens has revealed key genetic determinants that enable host switching and cross-species transmission [33]. These studies have demonstrated the critical importance of factors such as: