Computational Docking in Chemogenomic Library Design: Strategies, Challenges, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integral role computational docking plays in the design and optimization of chemogenomic libraries for modern drug discovery.

Computational Docking in Chemogenomic Library Design: Strategies, Challenges, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integral role computational docking plays in the design and optimization of chemogenomic libraries for modern drug discovery. It explores the foundational principles of chemogenomics and docking, details current methodological approaches and their practical applications in creating targeted libraries for areas like precision oncology, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies for improving predictive accuracy, and discusses rigorous validation frameworks essential for translational success. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent advances, including the integration of artificial intelligence and high-throughput validation techniques, to guide the effective application of in silico methods for systematic drug-target interaction analysis and library prioritization.

The Foundations of Chemogenomics and Computational Docking

Chemogenomics is a crucial discipline in pharmacological research and drug discovery that aims towards the systematic identification of small molecules that interact with protein targets and modulate their function [1]. The field operates on the principle of exploring the vast interaction space between chemical compounds and biological targets on a systematic scale, moving beyond the traditional one-drug-one-target paradigm. The final goal of chemogenomics is identifying small molecules that can interact with any biological target, although this task is essentially impossible to achieve experimentally due to the enormous number of existing small molecules and biological targets [1].

Developments in computer science-related disciplines, such as cheminformatics, molecular modelling, and artificial intelligence (AI) have made possible the in silico analysis of millions of potential interactions between small molecules and biological targets, prioritizing on a rational basis the experimental tests to be performed, thereby reducing the time and costs associated with them [1]. These computational approaches represent the toolbox of computational chemogenomics [1], which forms the foundation for systematic exploration of drug-target space.

Historical Evolution and Conceptual Framework

The philosophy behind chemical library design has changed radically since the early days of vast, diversity-driven libraries. This change was essential because the large numbers of compounds synthesised did not result in the increase in drug candidates that was originally envisaged [2]. Between 1990 and 2000, while the number of compounds synthesised and screened increased by several orders of magnitude, the number of new chemical entities remained relatively constant, averaging approximately 37 per annum [2].

This led to a rapid evolution in library design strategy with the introduction of significant medicinal chemistry design components. Libraries are now more frequently 'focused,' through design strategies intended to hit a single biological target or family of related targets [2]. This shift from 'drug-like' to 'lead-like' designs followed from published analysis of marketed drugs and the leads from which they were developed, observing that marketed drugs were more soluble, more hydrophobic and had a larger molecular weight than the original lead [2].

Table 1: Evolution of Library Design Strategies in Chemogenomics

| Era | Primary Strategy | Key Focus | Typical Library Size | Success Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990s | Diversity-driven | Maximizing chemical diversity | Very large (>100,000 compounds) | Number of compounds synthesized |

| Early 2000s | Drug-like | Compliance with Lipinski rules | Large (10,000-100,000 compounds) | Chemical properties compliance |

| Modern Era | Lead-like, Focused | Biological relevance, ADMET optimization | Targeted (1,000-10,000 compounds) | Hit rates, scaffold diversity |

Computational Methodologies in Chemogenomics

Molecular Docking Fundamentals

Molecular docking is a computational technique that predicts the binding affinity of ligands to receptor proteins and has developed into a formidable tool for drug development [3]. This technique involves predicting the interaction between a small molecule and a protein at the atomic level, enabling researchers to study the behavior of small molecules within the binding site of a target protein and understand the fundamental biochemical process underlying this interaction [3].

The process of docking involves two main steps: sampling the ligand and utilizing a scoring function [3]. Sampling algorithms help to identify the most energetically favorable conformations of the ligand within the protein's active site, taking into account their binding mode. These confirmations are then ranked using a scoring function [3].

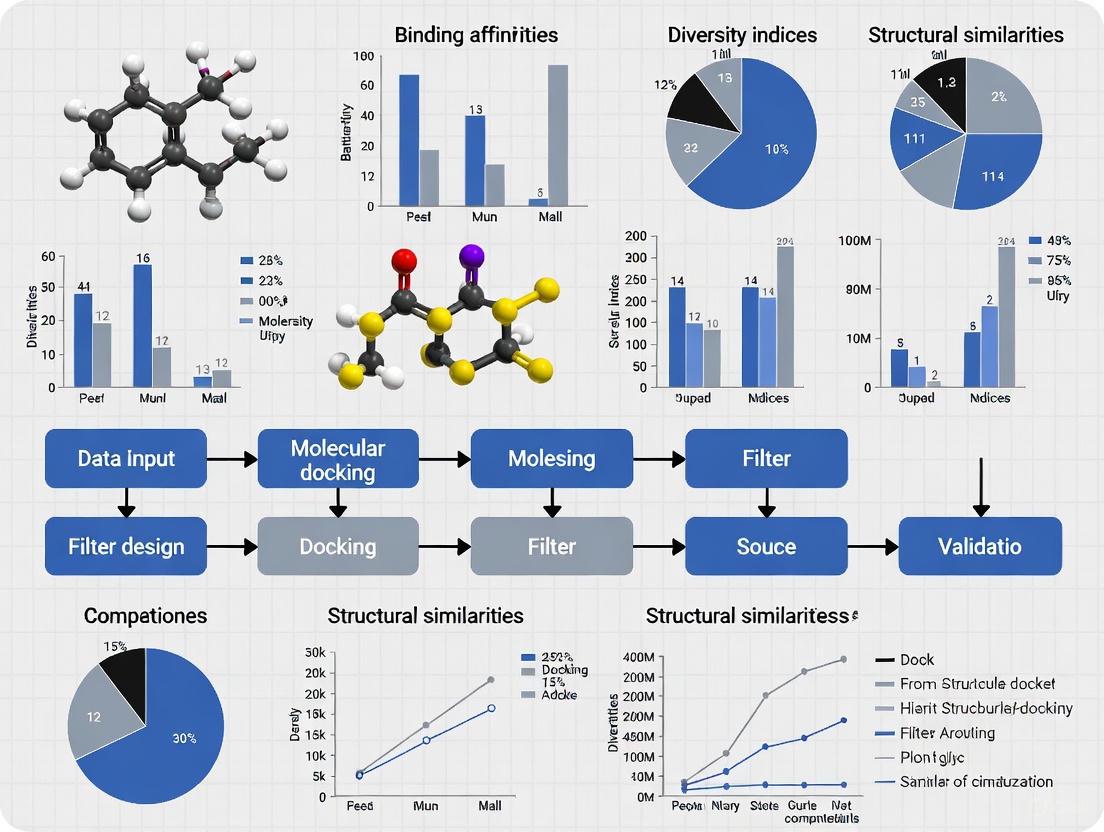

Figure 1: Molecular Docking Workflow illustrating the key steps in predicting ligand-protein interactions.

Search Algorithms and Scoring Functions

Search algorithms in molecular docking are classified into systematic methods and stochastic methods [3]. Systematic methods include conformational search (gradually changing torsional, translational, and rotational degrees of freedom), fragmentation (docking multiple fragments that form bonds between them), and database search (creating reasonable conformations of molecules from databases) [3]. Stochastic methods include Monte Carlo (randomly placing ligands and generating new configurations), genetic algorithms (using population of postures with transformations of the fittest), and tabu search (avoiding previously exposed conformational spaces) [3].

Scoring functions are equally critical and are categorized into four main groupings [3]:

- Force field-based: Adds the contribution of non-bonded interactions including van der Waal forces, hydrogen bonding, and Columbic electrostatics.

- Empirical function: Relies on repeated linear relapse analysis of a prepared set of complex structures using protein-ligand complexes with known binding affinities.

- Knowledge-based: Statistically assesses a collection of complex structures, providing elements, atoms, and functional groupings.

- Consensus: Fuses the evaluations or orders obtained through multiple evaluation methods.

Table 2: Common Molecular Docking Software and Their Applications

| Software | Algorithm Type | Key Features | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Gradient Optimization | Fast execution, easy to use | Virtual screening, binding pose prediction |

| DOCK 3.5.x | Shape-based matching | Transition state modeling | Enzyme substrate identification |

| Glide | Systematic search | High accuracy pose prediction | Lead optimization |

| GOLD | Genetic Algorithm | Protein flexibility handling | Protein-ligand interaction studies |

| FlexX | Fragment-based | Efficient database screening | Large library screening |

Practical Implementation: Chemogenomic Library Design

Multi-Objective Optimization in Library Design

Modern combinatorial library design represents a multi-objective optimization process, which requires consideration of cost, synthetic feasibility, availability of reagents, diversity, drug- or lead-likeness, likely ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) and toxicity properties, in addition to biological target focus [2]. Several groups are developing statistical approaches to allow multi-objective optimization of library design, with programs like SELECT and MoSELECT being developed for this purpose [2].

The shift toward ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Elimination, Toxicity) prediction at the library-design stage followed the pharmaceutical industry's concern over high attrition rates in drug development. Most pharmaceutical companies now introduce some degree of ADMET prediction at the library-design stage in an attempt to decrease this high failure rate [2]. The later drugs fail in the development process the more costly to the company, thus early identification and avoidance of potential problems is preferred [2].

Targeted Library Design Strategies

Various computational strategies are employed in targeted library design:

- QSAR-based Targeted Library Design: Using quantitative structure-activity relationship models to predict biological activity.

- Similarity Guided Design: Leveraging chemical similarity to known active compounds.

- Diversity-based Design: Ensuring appropriate chemical diversity within targeted space.

- Pharmacophore-guided Design: Using 3D pharmacophore models to focus library design.

- Protein Structure Based Methods: Utilizing protein structural information for structure-based design [4].

Figure 2: Chemogenomic Library Design Workflow showing the multi-objective optimization process.

Case Study: NR3 Nuclear Hormone Receptor Chemogenomics

A recent practical application of chemogenomics principles demonstrates the systematic approach to exploring drug-target space. Researchers compiled a dedicated chemogenomics library for the NR3 nuclear hormone receptors through rational design and comprehensive characterization [5].

Library Assembly Methodology

The library assembly followed a rigorous filtering process [5]:

- Initial Compound Identification: 9,361 NR3 ligands (EC50/IC50 ≤ 10 µM) were annotated from public compound/bioactivity databases with asymmetric distribution over the nine NR3 receptors.

- Filtering Criteria: Commercially available compounds with potency ≤1 µM were prioritized (with exceptions for poorly covered NR3B family at ≤10 µM potency).

- Selectivity Requirements: Up to five annotated off-targets were accepted in initial compound selection.

- Chemical Diversity Optimization: Chemical diversity was evaluated based on pairwise Tanimoto similarity computed on Morgan fingerprints, with candidate combination optimized for low similarity using a diversity picker.

- Mode of Action Diversity: Ligands with diverse modes of action (agonist, antagonist, inverse agonist, modulator, degrader) were included where available.

Experimental Validation Protocol

The selected candidates underwent comprehensive experimental characterization [5]:

- Cytotoxicity Screening: Conducted in HEK293T cells considering growth-rate, metabolic activity, and apoptosis/necrosis induction.

- Selectivity Profiling: Compounds tested for agonistic, antagonistic, and inverse agonistic activity in uniform hybrid reporter gene assays on twelve receptors representing NR1, NR2, NR4, and NR5 families.

- Liability Screening: Binding to a panel of liability targets assessed by differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) at 20 µM test concentration.

The final NR3 chemogenomics set comprised 34 compounds fully covering the NR3 family with 12 NR3A ligands, 7 NR3B ligands, and 17 NR3C ligands, including at least two modes of action with activating and inhibiting ligands for every NR3 subfamily [5]. The collection exhibited high chemical diversity with low pairwise similarity and high scaffold diversity, with the 34 compounds representing 29 different skeletons [5].

Table 3: NR3 Nuclear Hormone Receptor Chemogenomics Library Characteristics

| Parameter | NR3A Subfamily | NR3B Subfamily | NR3C Subfamily | Overall Library |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Compounds | 12 | 7 | 17 | 34 |

| Potency Range | Sub-micromolar | ≤10 µM | Sub-micromolar | Varied |

| Recommended Concentration | 0.3-1 µM | 3-10 µM | 0.3-1 µM | Target-dependent |

| Scaffold Diversity | High | High | High | 29 different skeletons |

| Modes of Action | Agonist, antagonist, degrader | Agonist, antagonist | Agonist, antagonist, modulator | Multiple represented |

Advanced AI Approaches in Modern Chemogenomics

Multitask Learning for Drug-Target Interaction

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have introduced sophisticated multitask learning frameworks that simultaneously predict drug-target binding affinities and generate novel target-aware drug variants. The DeepDTAGen framework represents one such approach, using common features for both tasks to leverage shared knowledge between drug-target affinity prediction and drug generation [6].

This model addresses key challenges in chemogenomics by [6]:

- Predicting drug-target binding affinity (DTA) values while simultaneously generating target-aware drugs

- Utilizing shared feature space for both tasks to learn structural properties of drug molecules, conformational dynamics of proteins, and bioactivity between drugs and targets

- Implementing the FetterGrad algorithm to address optimization challenges associated with multitask learning, particularly gradient conflicts between distinct tasks

Performance Metrics and Validation

Comprehensive evaluation of such AI models involves multiple metrics [6]:

- Binding Affinity Prediction: Mean Squared Error (MSE), Concordance Index (CI), R squared (r²m), and Area under precision-recall curve (AUPR)

- Compound Generation: Validity (proportion of chemically valid molecules), Novelty (valid molecules not present in training/testing sets), Uniqueness (proportion of unique molecules among valid ones)

- Chemical Analyses: Solubility, Drug-likeness, Synthesizability, and structural analysis (atom types, bond types, ring types)

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Chemogenomics

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem, BindingDB | Bioactivity data repository | Source of annotated ligands and activity data |

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD | Molecular docking simulations | Predicting ligand-target interactions |

| Chemical Descriptors | Morgan Fingerprints, MAP4 | Molecular representation | Chemical diversity assessment and similarity searching |

| Target Annotation | IUPHAR/BPS, Probes&Drugs | Target validation and annotation | Compound-target relationship establishment |

| ADMET Prediction | Various QSAR models | Property prediction | Early assessment of drug-like properties |

The field of chemogenomics continues to evolve with advances in computer science and AI, as well as the growing availability of experimental data opening the door to the development and refinement of new computational models [1]. The convergence of computer-aided drug discovery and artificial intelligence is leading toward next-generation therapeutics, with AI enabling rapid de novo molecular generation, ultra-large-scale virtual screening, and predictive modeling of ADMET properties [7].

Key future directions include:

- Expansion of Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS): Exploring underexplored regions including metal-containing molecules, macrocycles, protein-protein interaction modulators, and beyond Rule of 5 (bRo5) compounds [8].

- Universal Descriptor Development: Creating structure-inclusive, general-purpose descriptors that can accommodate entities ranging from small molecules to biomolecules [8].

- Integration of Experimental and Computational Approaches: Combining automated laboratories with AI design to revolutionize drug discovery timelines [7].

Chemogenomics represents a systematic, knowledge-based approach to drug discovery that leverages computational methodologies to efficiently explore the vast drug-target interaction space. By integrating computational predictions with experimental validation, chemogenomics provides a powerful framework for identifying novel bioactive compounds, elucidating mechanisms of action, and accelerating the development of new therapeutics.

The Evolution of Computational Docking in Drug Discovery

Computational docking has evolved from a specialized computational technique into a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, profoundly impacting chemogenomic library design. This evolution is marked by the transition from rigid-body docking of small libraries to the flexible, AI-enhanced docking of ultra-large virtual chemical spaces encompassing billions of molecules. In the context of chemogenomic research, which requires the systematic screening of chemical compounds against families of pharmacological targets, docking has become indispensable for prioritizing synthetic effort and enriching libraries with high-value candidates. This application note details the key stages of this evolution, presents quantitative performance benchmarks, and provides structured protocols for implementing state-of-the-art docking workflows to drive efficient chemogenomic library design.

The Evolutionary Trajectory of Docking Methods

The development of computational docking can be categorized into three distinct generations, each defined by major technological shifts in sampling algorithms, scoring functions, and the scale of application. The table below summarizes these key developmental stages.

Table 1: Key Stages in the Evolution of Computational Docking

| Generation | Time Period | Defining Characteristics | Sampling Algorithms | Scoring Functions | Typical Library Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Generation: Rigid-Body Docking | 1980s-1990s | Treatment of protein and ligand as rigid entities; geometric complementarity. | Shape matching, clique detection [9] | Simple energy-based or geometric scoring [9] | Hundreds to Thousands [10] |

| Second Generation: Flexible-Ligand Docking | 1990s-2010s | Incorporation of ligand flexibility; rise of stochastic search methods. | Genetic Algorithms (GA), Monte Carlo (MC), Lamarckian GA (LGA) [9] [11] | Empirical and force-field based functions [12] [9] | Millions [10] |

| Third Generation: AI-Enhanced & Large-Scale Docking | 2010s-Present | Integration of machine learning; handling of ultra-large libraries and target flexibility. | Hybrid AI/physics methods, gradient-based optimization [13] [9] | Machine learning-scoring functions, hybrid physics/AI scoring [14] [9] | Hundreds of Millions to Billions [13] [10] |

This progression has directly enabled the current paradigm of chemogenomic library design, where the goal is to efficiently explore chemical space against multiple target classes. The advent of third-generation docking allows researchers to pre-emptively screen vast virtual libraries, ensuring that synthesized compounds within a chemogenomic set have a high predicted probability of success against their intended targets.

Benchmarking Docking Performance for Informed Protocol Selection

Selecting an appropriate docking program is critical for the success of any structure-based virtual screening campaign. Independent benchmarking studies provide essential data for this decision. The following table summarizes the performance of several popular docking programs in reproducing experimental binding modes (pose prediction) and identifying active compounds from decoys (virtual screening enrichment).

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Common Docking Programs

| Docking Program | Pose Prediction Performance (RMSD < 2.0 Å) | Virtual Screening AUC (Area Under the Curve) | Key Strengths & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glide | 100% (COX-1/COX-2 benchmark) [12] | 0.92 (COX-2) [12] | High accuracy in pose prediction and enrichment; suitable for lead optimization [12]. |

| GOLD | 82% (COX-1/COX-2 benchmark) [12] | 0.61-0.89 (COX enzymes) [12] | Robust performance across diverse target classes; widely used in virtual screening [12]. |

| AutoDock | 76% (COX-1/COX-2 benchmark) [12] | 0.71 (COX-2) [12] | Open-source; highly tunable parameters; good balance of speed and accuracy [12] [11]. |

| FlexX | 59% (COX-1/COX-2 benchmark) [12] | 0.61-0.76 (COX enzymes) [12] | Fast docking speed; efficient for large library pre-screening [12]. |

| AutoDock Vina | Not Specifically Benchmarked | Not Specifically Benchmarked | Exceptional speed; user-friendly; ideal for rapid prototyping and smaller-scale docking [11]. |

These results demonstrate that no single algorithm is universally superior. Glide excels in accuracy, while AutoDock Vina offers a balance of speed and ease of use. The choice of software should be tailored to the specific project goals, whether it is high-accuracy pose prediction for lead optimization or faster screening for initial hit identification.

Advanced Protocols for Modern Docking Applications

Protocol: Large-Scale Virtual Screening for Chemogenomic Library Design

This protocol is adapted from established practices for screening ultra-large libraries and is designed for integration into a chemogenomic pipeline where multiple targets are screened in parallel [10].

Step 1: Target Preparation and Binding Site Definition

- Structure Preparation: Obtain a high-resolution crystal structure of the target protein (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org). Using a molecular modeling suite, remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands not critical for binding. Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and correct for missing residues or loops where necessary [10] [12].

- Grid Generation: Define the docking search space by creating a 3D grid box centered on the binding site of interest. The box should be large enough to accommodate a range of ligand sizes but constrained to reduce computational time. Tools like AutoGrid (for AutoDock) are used for this purpose [10] [11].

Step 2: Virtual Library Curation and Preparation

- Library Sourcing: Select a virtual screening library, such as ZINC15, which contains billions of "make-on-demand" compounds, or a bespoke chemogenomic library [13] [10].

- Ligand Preparation: Filter the library based on drug-likeness (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) and desired physicochemical properties. Prepare the ligands by generating plausible 3D conformations, optimizing geometry, and assigning correct ionization states at physiological pH using tools like RDKit or commercial suites [13].

Step 3: Docking Execution and Pose Prediction

- Parameter Configuration: Select a docking algorithm (see Table 2) and configure its parameters. For large-scale screens, balance accuracy with computational cost. The Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) in AutoDock is a common choice [10] [11].

- High-Performance Computing (HPC): Distribute the docking of millions of compounds across a computer cluster or cloud computing platform. Modern platforms can screen billions of compounds by leveraging such resources [10] [15].

Step 4: Post-Docking Analysis and Hit Prioritization

- Primary Ranking: Rank all docked compounds by their predicted binding affinity (docking score).

- Interaction Analysis: Manually inspect the top-ranking compounds (e.g., the top 1,000) to evaluate the quality of protein-ligand interactions, such as hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts. Clustering based on structural motifs can ensure diversity in the selected hits [10].

- Experimental Triaging: Select a final, manageable set of 100-500 compounds for purchase and experimental validation in biochemical or cellular assays [10].

Protocol: Machine Learning-Guided Algorithm Selection for Per-Target Optimization

The "No Free Lunch" theorem implies that no single docking algorithm is optimal for every target. This protocol uses a machine learning-based algorithm selection approach to automatically choose the best algorithm for a specific protein-ligand docking task, a critical consideration for robust chemogenomic studies across diverse protein families [9].

Step 1: Create an Algorithm Pool

- Configure a single docking engine, such as AutoDock, with a diverse set of parameters to create a pool of distinct algorithm variants. For example, varying the population size, number of evaluations, and rate of mutation in the LGA can generate 28 or more unique algorithm configurations [9].

Step 2: Feature Extraction for the Target Instance

- For a given protein and ligand, compute a set of descriptive features that characterize the docking instance. These should include:

Step 3: Algorithm Recommendation and Docking

- Employ a pre-trained algorithm recommender system (e.g., ALORS). The system takes the computed feature vector as input and recommends the top-performing algorithm from the pool created in Step 1 [9].

- Execute the docking calculation using the recommended algorithm configuration.

Step 4: Performance Validation

- Validate the approach by comparing the performance of the selected algorithm against the default algorithm and other candidates. The selected algorithm should consistently achieve lower binding energies or more accurate pose reproduction for a given target [9].

ML-Driven Docking Workflow: This diagram illustrates the automated protocol for selecting an optimal docking algorithm for a specific protein-ligand pair using machine learning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

A modern computational docking workflow relies on a suite of software tools and data resources. The following table details the key components of the computational chemist's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Computational Docking

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Docking | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Suite (AutoDock4, Vina) [11] | Docking Software | Core docking engine for pose prediction and scoring. | Open-source; includes LGA; Vina is optimized for speed [11]. |

| RDKit [13] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Ligand preparation, descriptor calculation, and chemical space analysis. | Open-source; extensive functions for molecule manipulation and featurization [13]. |

| Glide [12] | Docking Software | High-accuracy docking and virtual screening. | High performance in pose prediction and enrichment factors [12]. |

| ZINC15 [13] [10] | Compound Database | Source of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | Contains billions of purchasable molecules with associated data [13]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [12] | Structural Database | Source of experimental 3D structures of target proteins. | Essential for structure-based drug design and target preparation [12]. |

Computational docking is poised for further transformation through deeper integration with artificial intelligence and experimental data. Key trends defining its future include:

- AI and Generative Chemistry: AI is now used to not just score compounds, but to generate novel, optimized molecular structures de novo from scratch. Techniques like gradient-based optimization allow for the direct generation of molecules with desired properties, such as high binding affinity and solubility, moving beyond simple virtual screening [13] [16].

- Integration with Experimental Validation: Technologies like CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) are becoming standard for confirming target engagement in cells, providing critical experimental validation for computationally derived hits and closing the loop in the design-make-test-analyze cycle [14].

- Hybrid and Explainable AI: The future lies in hybrid models that combine the interpretability of physics-based force fields with the pattern-recognition power of machine learning. This will improve not only predictive accuracy but also the explainability of AI-generated results, which is crucial for building scientific trust and generating testable hypotheses [16] [9].

In conclusion, the evolution of computational docking has fundamentally reshaped chemogenomic library design, enabling a shift from serendipitous discovery to rational, data-driven design. By leveraging the advanced protocols and insights outlined in this document, researchers can confidently employ docking to navigate the vastness of chemical and target space, accelerating the delivery of novel therapeutic agents.

Molecular docking, virtual screening, and binding affinity prediction represent foundational methodologies in modern structure-based drug design. These computational approaches enable researchers to predict how small molecules interact with biological targets, significantly accelerating the identification and optimization of potential therapeutic compounds [17]. Within chemogenomic library design—a discipline focused on systematically understanding interactions between chemical spaces and protein families—these techniques provide the critical link between genomic information and chemical functionality. By integrating molecular docking with chemogenomic principles, researchers can design targeted libraries that maximize coverage of relevant target classes while elucidating complex polypharmacological profiles [18]. The continuing evolution of these methods, particularly through incorporation of machine learning, is transforming their accuracy and scope in early drug discovery.

Core Computational Methodologies

Molecular Docking: Principles and Workflows

Molecular docking computationally predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule ligand when bound to a protein target. The process involves two fundamental components: a search algorithm that explores possible ligand conformations and orientations within the binding site, and a scoring function that ranks these poses by estimating interaction strength [19]. Docking serves not only to predict binding modes but also to provide initial estimates of binding affinity, forming the basis for virtual screening.

Successful docking requires careful preparation of both protein structures and ligand libraries. Protein structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) typically require removal of water molecules, addition of hydrogen atoms, and assignment of partial charges. Small molecules must be converted into appropriate 3D formats with optimized geometry and often converted to specific file formats such as PDBQT for tools like AutoDock Vina [20]. The docking process itself is guided by defining a search space, typically centered on known or predicted binding sites, with dimensions sufficient to accommodate ligand flexibility.

Table 1: Common Docking Software and Their Key Characteristics

| Software Tool | Scoring Function Type | Key Features | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Empirical & Knowledge-based | Fast, easy to use, supports ligand flexibility | Virtual screening, pose prediction [20] |

| QuickVina 2 | Optimized Empirical | Faster execution while maintaining accuracy | Large library screening [20] |

| PLANTS | Empirical | Efficient stochastic algorithm | Benchmarking studies [21] |

| FRED | Shape-based & Empirical | Comprehensive, high-throughput | Large-scale virtual screening [21] |

| Glide SP | Force field-based | High accuracy pose prediction | Lead optimization [22] |

Virtual Screening Approaches

Virtual screening (VS) applies docking methodologies to evaluate large chemical libraries, prioritizing compounds with highest potential for binding to a target of interest. Structure-based virtual screening leverages 3D structural information of the target protein to identify hits, while ligand-based approaches utilize known active compounds when structural data is unavailable [17]. The dramatic growth of make-on-demand chemical libraries containing billions of compounds has created both unprecedented opportunities and significant computational challenges for virtual screening [23].

Advanced virtual screening protocols often incorporate machine learning to improve efficiency. These approaches typically involve docking a subset of the chemical library, training ML classifiers to identify top-scoring compounds, and then applying these models to prioritize molecules for full docking assessment. This strategy can reduce computational requirements by more than 1,000-fold while maintaining high sensitivity in identifying true binders [23]. The CatBoost classifier with Morgan2 fingerprints has demonstrated optimal balance between speed and accuracy in such workflows [23].

Binding Affinity Prediction Methods

Accurate prediction of protein-ligand binding affinity remains a central challenge in computational drug design. Binding affinity quantifies the strength of molecular interactions, with direct impact on drug efficacy and specificity [24]. Traditional methods include scoring functions within docking software, which provide fast but approximate affinity estimates, and more rigorous molecular dynamics-based approaches like MM-PBSA/GBSA that offer improved accuracy at greater computational cost [19].

The emergence of deep learning has revolutionized binding affinity prediction. DL models automatically extract complex features from raw structural data, capturing patterns that elude traditional methods. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), graph neural networks (GNNs), and transformer-based architectures have demonstrated superior performance in predicting binding affinities, though they require large, high-quality training datasets [24]. Methods like RF-Score and CNN-Score have shown hit rates three times greater than traditional scoring functions at the top 1% of ranked molecules [21].

Diagram 1: Workflow of integrated structure-based drug design, showing the relationship between molecular docking, virtual screening, and binding affinity prediction.

Application Notes: Protocol for Automated Virtual Screening

System Setup and Software Installation

A robust virtual screening pipeline requires proper setup of computational environment and dependencies. For Unix-like systems (including Windows Subsystem for Linux for Windows users), the following installation protocol provides necessary components [20]:

Timing: Approximately 35 minutes

System Update and Essential Packages:

Install AutoDockTools (MGLTools):

Install fpocket for Binding Site Detection:

Install QuickVina 2 (AutoDock Vina variant):

Download and Configure Protocol Scripts:

Virtual Screening Execution Protocol

The following protocol outlines a complete virtual screening workflow using the jamdock-suite, which provides modular scripts automating each step of the process [20]:

Timing: Variable, depending on library size and computational resources

Compound Library Generation (

jamlib):Generates energy-minimized compounds in PDBQT format, addressing format compatibility issues with databases like ZINC.

Receptor Preparation and Binding Site Detection (

jamreceptor):Uses fpocket to detect and characterize binding cavities, providing druggability scores to guide docking site selection.

Grid Box Setup: Manually edit configuration file to define search space coordinates based on fpocket output or known binding site information.

Molecular Docking Execution (

jamqvina):Supports execution on local machines, cloud servers, and HPC clusters for scalable screening.

Results Ranking and Analysis (

jamrank):Applies two scoring methods to identify most promising hits and facilitates triage for experimental validation.

Machine Learning-Guided Screening for Ultra-Large Libraries

For screening multi-billion compound libraries, traditional docking becomes computationally prohibitive. The following protocol integrates machine learning to dramatically improve efficiency [23]:

Initial Docking and Training Set Generation:

- Dock 1 million randomly selected compounds from the target library

- Label compounds as "active" or "inactive" based on docking score threshold (typically top 1%)

Classifier Training:

- Train CatBoost classifier on Morgan2 fingerprints of the training set

- Use 80% of data for training, 20% for calibration

- Implement Mondrian conformal prediction framework for validity

Library Prioritization:

- Apply trained classifier to entire multi-billion compound library

- Select significance level (ε) to control error rate and define virtual active set

- Typically reduces docking candidate pool by 10-100x while retaining >85% of true actives

Final Docking and Validation:

- Perform explicit docking only on the predicted virtual active set

- Experimental validation of top-ranking compounds confirms method efficacy

Performance Benchmarking and Validation

Comparative Performance of Docking Methods

Rigorous benchmarking establishes the relative strengths and limitations of different docking approaches. Evaluation across multiple dimensions—including pose prediction accuracy, physical plausibility, virtual screening efficacy, and generalization capability—provides comprehensive assessment [22].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Docking Methods Across Key Metrics

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Pose Accuracy (RMSD ≤ 2Å) | Physical Validity (PB-valid) | Virtual Screening Enrichment | Computational Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Docking | Glide SP, AutoDock Vina | Medium-High (60-80%) | High (>94%) | Medium-High | Medium |

| Generative Diffusion Models | SurfDock, DiffBindFR | High (>75%) | Medium (40-63%) | Variable | Fast (after training) |

| Regression-based Models | KarmaDock, QuickBind | Low (<40%) | Low (<20%) | Low | Very Fast |

| Hybrid Methods | Interformer | Medium-High | Medium-High | High | Medium |

| ML-Rescoring | RF-Score-VS, CNN-Score | N/A | N/A | Significant improvement over base docking | Fast |

Recent comprehensive evaluations reveal a performance hierarchy across method categories. Traditional methods like Glide SP consistently excel in physical validity, maintaining PB-valid rates above 94% across diverse test sets. Generative diffusion models, particularly SurfDock, achieve exceptional pose accuracy (exceeding 75% across benchmarks) but demonstrate deficiencies in modeling physicochemical interactions, resulting in moderate physical validity. Regression-based models generally perform poorly on both pose accuracy and physical validity metrics [22].

Machine Learning Rescoring Enhancements

Integration of machine learning scoring functions as post-docking rescoring tools significantly enhances virtual screening performance. Benchmarking studies against malaria targets (PfDHFR) demonstrate that rescoring with CNN-Score consistently improves enrichment metrics. For wild-type PfDHFR, PLANTS combined with CNN rescoring achieved an enrichment factor (EF1%) of 28, while for the quadruple-mutant variant, FRED with CNN rescoring yielded EF1% of 31 [21]. These improvements substantially exceed traditional docking performance, particularly for challenging drug-resistant targets.

Rescoring performance varies substantially across targets and docking tools, highlighting the importance of method selection tailored to specific applications. For AutoDock Vina, rescoring with RF-Score-VS and CNN-Score improved screening performance from worse-than-random to better-than-random in PfDHFR benchmarks [21]. The pROC-Chemotype plots further confirmed that these rescoring combinations effectively retrieved diverse, high-affinity actives at early enrichment stages—a critical characteristic for practical drug discovery applications.

Diagram 2: Advanced workflow incorporating machine learning rescoring and pose refinement to enhance docking accuracy and binding affinity prediction.

Key Databases for Virtual Screening

High-quality, curated datasets are prerequisite for effective virtual screening and method development. Several publicly available databases provide structural and bioactivity data essential for training and validation [25].

Table 3: Essential Databases for Virtual Screening and Binding Affinity Prediction

| Database | Content Type | Size (as of 2021) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDBbind | Protein-ligand complexes with binding affinity data | 21,382 complexes (general set); 4,852 (refined set); 285 (core set) | Scoring function development, method validation [25] |

| BindingDB | Experimental protein-ligand binding data | 2,229,892 data points; 8,499 targets; 967,208 compounds | Model training, chemogenomic studies [25] |

| ChEMBL | Bioactivity data from literature and patents | 14,347 targets; 17 million activity points | Ligand-based screening, QSAR modeling [25] |

| PubChem | Chemical structures and bioassay data | 109 million structures; 280 million bioactivity data points | Compound sourcing, activity profiling [25] |

| ZINC | Commercially available compounds for virtual screening | 13 million in-stock compounds | Library design, compound acquisition [20] |

| DEKOIS | Benchmark sets for docking evaluation | 81 protein targets with actives and decoys | Docking method benchmarking [21] |

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Molecular Docking and Virtual Screening

| Tool/Resource | Category | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina/QuickVina 2 | Docking Software | Predicting ligand binding modes and scores | Open Source [20] |

| MGLTools | Molecular Visualization | Protein and ligand preparation for docking | Open Source [20] |

| OpenBabel | Chemical Toolbox | File format conversion, molecular manipulation | Open Source [20] |

| fpocket | Binding Site Detection | Identifying and characterizing protein binding pockets | Open Source [20] |

| PDB | Structural Database | Source of experimental protein structures | Public Repository [25] |

| BEAR (Binding Estimation After Refinement) | Post-docking Refinement | Binding affinity prediction through MD and MM-PBSA/GBSA | Proprietary [19] |

| CNN-Score | ML Scoring Function | Improved virtual screening through neural network scoring | Open Source [21] |

| RF-Score-VS | ML Scoring Function | Random forest-based scoring for enhanced enrichment | Open Source [21] |

Advanced Applications in Chemogenomics

Within chemogenomic library design, molecular docking and virtual screening enable systematic mapping of compound-target interactions across entire protein families. This approach facilitates development of targeted libraries optimized for specific target classes like kinases or GPCRs, while also elucidating polypharmacological profiles critical for drug efficacy and safety [18]. By screening compound libraries across multiple structurally-related targets, researchers can identify selective compounds and promiscuous binders, informing both targeted drug development and understanding of off-target effects.

Advanced implementations have demonstrated practical utility in precision oncology applications. For glioblastoma, customized chemogenomic libraries covering 1,320 anticancer targets enabled identification of patient-specific vulnerabilities through phenotypic screening of glioma stem cells [18]. The highly heterogeneous responses observed across patients and subtypes underscore the value of targeted library design informed by structural and chemogenomic principles. These approaches provide frameworks for developing minimal screening libraries that maximize target coverage while maintaining practical screening scope.

Molecular docking, virtual screening, and binding affinity prediction constitute essential components of modern computational drug discovery, particularly within chemogenomic library design frameworks. The integration of machine learning across these methodologies continues to transform their capabilities, enabling navigation of vast chemical spaces with unprecedented efficiency. As deep learning approaches mature and experimental data resources expand, these computational techniques will play increasingly central roles in rational drug design, accelerating the discovery of therapeutic agents for diverse diseases. The protocols and benchmarks presented provide practical guidance for implementation while highlighting performance characteristics that inform method selection for specific research applications.

The foundation of any successful computational docking campaign, particularly within the strategic framework of chemogenomic library design, rests upon the quality and appropriateness of the underlying structural and chemical data. Chemogenomics aims to systematically identify small molecules that interact with protein targets to modulate their function, a task that relies heavily on computational approaches to navigate the vast space of potential interactions [1]. The selection of starting structures—whether experimentally determined or computationally predicted—directly influences the accuracy of virtual screening and the eventual experimental validation of hits. This application note details the primary public data sources for protein structures and related benchmark data, providing structured protocols to guide researchers in constructing robust and reliable docking workflows for precision drug discovery [18].

The following table summarizes the core public resources that provide protein structures and essential benchmark data for docking preparation and validation.

Table 1: Key Public Data Resources for Molecular Docking

| Resource Name | Data Type | Key Features & Scope | Use Case in Docking |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [26] | Experimentally-determined 3D structures | Primary archive for structures determined by X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM, and NMR; includes ligands, DNA, and RNA. | Source of target protein structures and experimental ligand poses for validation. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [27] | Computed Structure Models (CSM) | Over 200 million AI-predicted protein structures; broad coverage of UniProt. | Target structure when no experimental model is available. |

| PLA15 Benchmark Set [28] | Protein-Ligand Interaction Energies | Provides reference interaction energies for 15 protein-ligand complexes at the DLPNO-CCSD(T) level of theory. | Benchmarking the accuracy of energy calculations for scoring functions. |

| Protein-Ligand Benchmark Dataset [29] | Binding Affinity Benchmark | A curated dataset designed for benchmarking alchemical free energy calculations. | Validating and training free energy perturbation (FEP) protocols. |

Experimental Protocols for Data Preparation and Docking

A rigorous docking protocol requires careful preparation of both the protein target and the ligand library, followed by validation to ensure the computational setup can reproduce known biological interactions.

Protocol 1: Protein Structure Preparation and Selection

This protocol ensures the protein structure is optimized for docking simulations [10] [12].

- Structure Retrieval: Download the target protein structure from RCSB PDB [26] or AlphaFold DB [27]. Prioritize structures with high resolution (e.g., < 2.5 Å for X-ray crystallography) and low R-free values where applicable.

- Structure Editing and Preparation:

- Remove redundant chains, crystallographic water molecules, and non-essential ions and cofactors using molecular visualization software (e.g., DeepView) [12].

- Add missing hydrogen atoms and assign protonation states to key residues (e.g., His, Asp, Glu) at physiological pH.

- For metalloproteins, carefully curate the identity and coordination geometry of metal ions, noting that ongoing remediations aim to improve these annotations [26].

- Binding Site Definition:

- If the structure is co-crystallized with a ligand, define the binding site using the geometric coordinates of the native ligand.

- For apo structures or novel sites, use computational methods like FTMap or built-in tools in docking software to identify potential binding pockets [10].

- Structure Optimization (Optional): Perform a brief energy minimization of the protein structure, keeping the backbone atoms restrained. This step relieves minor steric clashes introduced during the addition of hydrogens and assignment of charges.

Protocol 2: Control Docking and Benchmarking

Before embarking on large-scale virtual screens, it is critical to validate the docking protocol's ability to reproduce experimental results [10] [12].

- Pose Reproduction Control:

- Extract the native co-crystallized ligand from the PDB file.

- Re-dock the ligand back into the prepared protein structure using the chosen docking software.

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) between the heavy atoms of the docked pose and the original crystallographic pose. An RMSD of less than 2.0 Å is generally considered a successful prediction [12].

- Virtual Screening Control (ROC Analysis):

- Dataset Curation: Compile a set of known active ligands and a set of inactive or decoy molecules for your target.

- Docking Screen: Dock the combined library of actives and decoys.

- Performance Evaluation: Perform Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis by ranking the compounds based on their docking scores and calculating the Area Under the Curve (AUC). A higher AUC indicates a better ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds. Enrichment factors at the top 1% of the screened library can also be calculated [12].

The workflow below illustrates the key steps involved in preparing for and validating a docking campaign.

Diagram 1: Data preparation and control docking workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential software tools and their primary functions in a docking pipeline, as highlighted in recent evaluations.

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for a Docking Pipeline

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Key Application in Docking |

|---|---|---|

| Glide (Schrödinger) [12] | Molecular Docking Software | Demonstrated top performance in correctly predicting binding poses (RMSD < 2Å) for COX enzyme inhibitors. |

| g-xTB [28] | Semiempirical Quantum Method | Provides highly accurate protein-ligand interaction energies for benchmarking scoring functions. |

| AutoDock Vina [10] | Molecular Docking Software | Widely used open-source docking engine; balances speed and accuracy. |

| MOE (Chemical Computing Group) [30] | Integrated Molecular Modeling | All-in-one platform for structure-based design, molecular docking, and QSAR modeling. |

| PyRx [31] | Virtual Screening Platform | User-friendly interface that integrates AutoDock Vina for screening large compound libraries. |

| OpenEye Toolkits [31] | Computational Chemistry Software | Provides fast, accurate docking (FRED) and shape-based screening (ROCS) capabilities. |

The meticulous preparation and validation of input data are not merely preliminary steps but are central to the success of any structure-based docking project. By leveraging the rich, publicly available data from repositories like the RCSB PDB and AlphaFold DB, and adhering to standardized protocols for structure preparation and control docking, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their virtual screening hits. In the context of chemogenomic library design, where the goal is the systematic exploration of chemical space against biological targets [1] [18], this rigorous approach to foundational data ensures that subsequent steps of lead optimization are built upon a solid and trustworthy computational foundation.

The Shift from Diversity-Based to Biologically-Focused Library Design

The design of compound libraries for high-throughput screening (HTS) has undergone a significant paradigm shift, moving from purely diversity-based selection to biologically-focused design strategies. Whereas early approaches to diversity analysis were based on traditional descriptors such as two-dimensional fingerprints, the recent emphasis has been on ensuring that a variety of different chemotypes are represented through scaffold coverage analysis [32]. This evolution is driven by the high costs associated with HTS coupled with the limited coverage and bias of current screening collections, creating continued importance for strategic library design [32].

The similar property principle—that structurally similar compounds are likely to have similar properties—initially drove diversity-based approaches aimed at maximizing coverage of structural space while minimizing redundancy [32]. However, whether designing diverse or focused libraries, it is now widely recognized that designs should aim to achieve a balance in a number of different properties, with multiobjective optimization providing an effective way of achieving such designs [32]. This shift represents a maturation of computational chemistry-driven decision making in lead generation.

Conceptual Framework: From Diversity to Focus

The Rationale for Diversity-Based Design

Diversity selection retains importance in specific scenarios, particularly when little is known about the target. In such cases, sequential screening strategies are employed—an iterative process that starts with a small representative set of diverse compounds, with the aim of deriving structure-activity information during the first round of screening, which is then used to select more focused sets in subsequent rounds [32]. Diversity analysis also remains crucial when purchasing compounds from external vendors to augment existing collections, as even large corporate libraries of 1-10 million compounds represent a tiny fraction of conservative estimates of drug-like chemical spaces (approximately 10¹³ compounds) [32].

The Transition to Biologically-Focused Approaches

The transition to focused design has been driven by several factors, including the recognition that rationally designed subsets often yield higher hit rates compared to random subsets [32]. Focused screening involves the selection of a subset of compounds according to an existing structure-activity relationship, which could be derived from known active compounds or from a protein target site, depending on available knowledge [32]. This approach directly leverages the growing understanding of target families and accumulated structural biology data to create libraries enriched with compounds more likely to interact with specific biological targets.

Quantitative Comparison of Library Design Strategies

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Library Design Strategies

| Design Parameter | Diversity-Based Approach | Biologically-Focused Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Maximize structural space coverage | Maximize probability of identifying hits for specific target |

| Target Information Requirement | Minimal | Substantial (SAR, structure, or known actives) |

| Typical Screening Strategy | Sequential screening | Direct targeted screening |

| Descriptor Emphasis | 2D fingerprints, physicochemical properties | Scaffold diversity, molecular docking scores |

| Chemical Space Coverage | Broad and diverse | Focused on relevant bioactivity regions |

| Hit Rate Potential | Variable, often lower | Generally higher |

| Resource Optimization | Higher initial screening costs | Reduced experimental validation costs |

Table 2: Performance Metrics from Library Design Studies

| Evaluation Metric | Diversity-Based Libraries | Focused Libraries | Combined Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Hit Rates | Lower | Higher (3-5x improvement) | Balanced |

| Scaffold Diversity | High | Moderate to low | Controlled diversity |

| Lead Development Potential | Variable | Higher | Optimized |

| Chemical Space Exploration | Extensive | Targeted | Strategic |

| Multi-parameter Optimization | Challenging | More straightforward | Integrated |

Experimental Protocols for Library Design

Protocol for Diversity-Focused Library Design

Objective: To create a structurally diverse screening library that maximizes coverage of chemical space while maintaining drug-like properties.

Materials and Reagents:

- Compound databases (e.g., ZINC15, PubChem)

- Cheminformatics software (e.g., RDKit, PaDEL Descriptor)

- Computational resources for descriptor calculation

Procedure:

Compound Collection and Preprocessing

Descriptor Calculation and Selection

Chemical Space Mapping and Diversity Analysis

Multiobjective Optimization

Validation:

- Evaluate library diversity using multiple metrics

- Assess drug-likeness using established filters (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five)

- Verify synthetic accessibility of selected compounds

Protocol for Biologically-Focused Library Design

Objective: To design a target-focused compound library using structure-based and ligand-based approaches.

Materials and Reagents:

- Target protein structure (experimental or homology model)

- Known active compounds (if available)

- Molecular docking software (e.g., DOCK3.7, AutoDock Vina)

- Cloud-based computational resources for large-scale screening

Procedure:

Target Preparation and Binding Site Analysis

- Obtain protein structure from PDB or create homology model

- Prepare protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, correcting protonation states

- Define binding site using experimental data or computational methods [10]

- Generate molecular interaction fields to characterize binding site properties

Virtual Library Creation and Filtering

Structure-Based Virtual Screening

Ligand-Based Design (when actives are known)

Library Optimization and Selection

- Apply multiobjective optimization to balance potency, selectivity, and properties

- Ensure appropriate scaffold diversity to mitigate risk

- Select final compounds for experimental testing

Validation:

- Evaluate enrichment of known actives in virtual screening

- Assess predicted binding affinity and complementarity

- Verify chemical tractability and synthetic feasibility

Computational Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Workflow for Integrated Library Design

Structure-Based Focused Design Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Library Design

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Library Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Software | Molecular descriptor calculation and manipulation | Structure searching, similarity analysis, descriptor calculation [13] |

| DOCK3.7 | Molecular Docking Software | Structure-based virtual screening | Large-scale docking of compound libraries [10] |

| PaDEL Descriptor | Descriptor Calculation | 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptor calculation | Feature extraction for QSAR and machine learning [33] |

| ZINC15 | Compound Database | Publicly accessible database of commercially available compounds | Source of screening compounds for virtual libraries [13] |

| Genetic Function Algorithm (GFA) | Modeling Algorithm | Variable selection for QSAR models | Descriptor selection and model development [33] |

| Pareto Ranking | Optimization Method | Multiobjective optimization | Balancing multiple properties in library design [32] |

| ChemicalToolbox | Web Server | Cheminformatics analysis interface | Downloading, filtering, visualizing small molecules [13] |

Implementation Considerations and Best Practices

Controls for Large-Scale Docking

When implementing structure-based focused design, establishing proper controls is essential for success. Prior to undertaking large-scale prospective screens, evaluate docking parameters for a given target using control calculations [10]. These controls help assess the ability of the docking protocol to identify known active compounds and reject inactive ones. Additional controls should be implemented to ensure specific activity for experimentally validated hit compounds, including confirmation of binding mode consistency and selectivity profiling [10].

Data Integration Strategies

The integration of diverse biological and chemical data through cheminformatics leverages advanced computational tools to create cohesive, interoperable datasets [13]. Integrated data pipelines are crucial for efficiently managing vast chemical and biological datasets, streamlining data flow from acquisition to actionable insights [13]. Implementation of in silico analysis platforms that combine computational methods like molecular docking, quantum chemistry, and molecular dynamics simulations enables more accurate prediction of drug-target interactions and compound properties [13].

Multiobjective Optimization Framework

Whether designing diverse or focused libraries, implementing a multiobjective optimization framework is essential for balancing the multiple competing priorities in library design. Pareto ranking has emerged as a popular way of analyzing data and visualizing the trade-offs between different molecular properties [32]. This approach allows researchers to identify compounds that represent the optimal balance between properties such as potency, selectivity, solubility, and metabolic stability, ultimately leading to more developable compound series.

The shift from diversity-based to biologically-focused library design represents a maturation of computational approaches in early drug discovery. By leveraging increased structural information and advanced computational methods, researchers can now create screening libraries that are strategically enriched for compounds with higher probabilities of success against specific biological targets. The integration of cheminformatics, molecular docking, and multiobjective optimization provides a powerful framework for navigating the complex landscape of chemical space while maximizing the efficiency of resource allocation in drug discovery pipelines.

The future of library design lies in the intelligent integration of diverse data sources and computational methods, creating a synergistic approach that leverages the strengths of both diversity-based and focused strategies. As computational power continues to increase and algorithms become more sophisticated, this integrated approach will likely yield even greater efficiencies in the identification of novel chemical starting points for drug development programs.

Methodologies and Practical Applications in Library Design

Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Design Strategies

In the field of computational drug discovery, structure-based and ligand-based design strategies represent two foundational paradigms for identifying and optimizing bioactive compounds. Structure-based drug design (SBDD) relies on three-dimensional structural information of the biological target to guide the development of molecules that can bind to it effectively [34] [35]. In contrast, ligand-based drug design (LBDD) utilizes information from known active molecules to predict and design new compounds with similar activity, particularly when structural data of the target is unavailable [34] [36]. Within chemogenomics research, which aims to systematically identify small molecules that interact with protein targets across entire families, both approaches provide crucial methodologies for exploring the vast chemical and target space in silico [1]. The integration of these complementary approaches has become increasingly valuable in early hit generation and lead optimization campaigns, enabling researchers to leverage all available chemical and structural information to maximize the success of drug discovery projects [37] [38].

Core Conceptual Frameworks

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD)

SBDD is fundamentally rooted in the molecular recognition principles that govern the interaction between a ligand and its macromolecular target. This approach requires detailed knowledge of the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, typically obtained through experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) [34] [39]. The core premise of SBDD is that by understanding the precise spatial arrangement of atoms in the binding site—including its topology, electrostatic properties, and hydropathic character—researchers can design molecules with complementary features that optimize binding affinity and selectivity [35].

The SBDD process typically follows an iterative cycle that begins with target structure analysis, proceeds through molecular design and optimization, and continues with experimental validation [34] [35]. When a lead compound is identified, researchers solve the three-dimensional structure of the lead bound to the target, examine the specific interactions formed, and use computational methods to design improvements before synthesizing and testing new analogs [39]. This structure-guided optimization continues through multiple cycles until compounds with sufficient potency and drug-like properties are obtained.

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD)

LBDD approaches are employed when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown or difficult to obtain, but information about active ligands is available. These methods operate under the molecular similarity principle, which posits that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activities [34] [37]. By analyzing the structural features and physicochemical properties of known active compounds, researchers can develop models that predict the activity of new molecules without direct knowledge of the target structure [34].

Key LBDD techniques include quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, which establishes mathematical relationships between molecular descriptors and biological activity; pharmacophore modeling, which identifies the essential steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition; and similarity searching, which compares molecular fingerprints or descriptors to identify compounds with structural resemblance to known actives [34] [37]. These approaches are particularly valuable for target classes where structural determination remains challenging, such as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) prior to the resolution of their crystal structures [40].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of SBDD and LBDD Approaches

| Aspect | Structure-Based Design (SBDD) | Ligand-Based Design (LBDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Required Information | 3D structure of target protein | Known active ligands |

| Key Methodologies | Molecular docking, molecular dynamics, de novo design | QSAR, pharmacophore modeling, similarity search |

| Primary Advantage | Direct visualization of binding interactions; rational design | No need for target structure; rapid screening |

| Main Limitation | Dependency on quality and relevance of protein structure | Limited to known chemical space; scaffold hopping challenging |

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) Protocol

Molecular docking represents a cornerstone technique in SBDD, enabling the prediction of how small molecules bind to a protein target and the estimation of their binding affinity [35]. The following protocol outlines a standard structure-based virtual screening workflow using molecular docking:

Step 1: Target Preparation

- Obtain the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through homology modeling [35] [41].

- Process the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and correcting any missing residues or atoms.

- Define the binding site coordinates based on known ligand interactions or structural features of the protein.

Step 2: Ligand Library Preparation

- Curate a database of small molecules for screening, applying appropriate filters for drug-likeness and chemical diversity [35].

- Generate three-dimensional conformations for each compound and optimize their geometries using molecular mechanics force fields.

- Assign appropriate atomic charges and prepare structures in formats compatible with the docking software.

Step 3: Molecular Docking

- Select an appropriate docking algorithm based on the system requirements (e.g., AutoDock, GOLD, Glide, DOCK) [35].

- Configure docking parameters, including search algorithms and scoring functions.

- Execute the docking simulations to generate multiple binding poses for each compound.

- Apply post-docking minimization to refine the predicted binding geometries.

Step 4: Analysis and Hit Selection

- Rank compounds based on their docking scores and examine the predicted binding modes of top-ranked molecules.

- Assess key intermolecular interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-π stacking) between ligands and the target.

- Select a subset of diverse compounds with favorable binding characteristics for experimental validation.

Diagram 1: Structure-Based Virtual Screening Workflow

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) Protocol

Ligand-based virtual screening employs similarity metrics and machine learning models to identify novel active compounds based on known actives. The following protocol describes a typical LBVS workflow:

Step 1: Reference Ligand Curation

- Compile a set of known active compounds with demonstrated activity against the target of interest.

- Include structurally diverse actives to capture different aspects of structure-activity relationships.

- Optionally, collect inactive compounds to enhance model specificity.

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation

- Compute molecular descriptors that encode structural, topological, and physicochemical properties.

- Generate fingerprints that capture key molecular features (e.g., ECFP, FCFP, MACCS keys).

- Select appropriate descriptors based on the target class and available data.

Step 3: Model Development

- For QSAR modeling: Develop mathematical models that correlate descriptor values with biological activity using methods such as partial least squares (PLS) or machine learning algorithms [34].

- For pharmacophore modeling: Identify essential chemical features and their spatial arrangement required for biological activity [34] [37].

- Validate models using cross-validation and external test sets to ensure predictive performance.

Step 4: Database Screening

- Apply the developed models to screen virtual compound libraries.

- Rank compounds based on predicted activity or similarity to known actives.

- Apply additional filters based on drug-like properties or structural diversity.

Step 5: Hit Selection and Analysis

- Select compounds with high predicted activity or similarity scores.

- Cluster hits based on structural similarity to ensure chemical diversity.

- Propose selected compounds for experimental testing.

Table 2: Common Ligand-Based Screening Techniques

| Technique | Key Principle | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 2D Similarity Search | Compares molecular fingerprints | Rapid screening of large libraries |

| 3D Pharmacophore | Matches spatial arrangement of chemical features | Scaffold hopping; target with unknown structure |

| QSAR Modeling | Relates molecular descriptors to activity | Lead optimization; activity prediction |

| Machine Learning | Learns complex patterns from known actives | Large annotated chemical libraries available |

Hybrid Strategies: Integrating SBDD and LBDD

The integration of structure-based and ligand-based methods has emerged as a powerful strategy that leverages the complementary strengths of both approaches [37] [38]. Hybrid strategies can be implemented in sequential, parallel, or fully integrated manners to enhance the efficiency and success rate of virtual screening campaigns.

Sequential Integration Protocols

Sequential approaches apply SBDD and LBDD methods in consecutive steps, typically beginning with faster ligand-based methods to filter large compound libraries before applying more computationally intensive structure-based techniques [37] [38]. The following protocol outlines a sequential hybrid screening strategy:

Protocol: Sequential Hybrid Screening

Initial Ligand-Based Filtering

- Perform 2D similarity searching against known active compounds using molecular fingerprints.

- Apply QSAR models to predict compound activity and remove compounds with low predicted potency.

- Select the top 5-10% of compounds from the initial library for further analysis.

Structure-Based Refinement

- Perform molecular docking of the pre-filtered compound set against the target structure.

- Analyze binding poses to ensure compounds form key interactions with the target.

- Apply more rigorous scoring functions or binding affinity estimation methods to the top docking hits.

Final Selection

- Combine ligand-based and structure-based rankings using consensus scoring methods.

- Apply additional filters for drug-like properties, synthetic accessibility, and structural diversity.

- Select a final set of compounds for experimental testing.

Parallel and Integrated Approaches

Parallel approaches run SBDD and LBDD methods independently on the same compound library and combine the results through consensus scoring [37] [38]. Integrated approaches more tightly couple the methodologies, such as using pharmacophore constraints derived from protein-ligand complexes to guide docking studies.

Protocol: Parallel Consensus Screening

Independent Screening

- Run ligand-based similarity searching and QSAR predictions on the entire compound library.

- Simultaneously, perform molecular docking of all compounds against the target structure.

- Generate separate ranked lists from each approach.

Consensus Scoring

- Normalize scores from different methods to a common scale.

- Apply rank-based or score-based fusion methods to combine rankings.

- Prioritize compounds that rank highly in both ligand-based and structure-based screens.

Binding Mode Analysis

- Examine the predicted binding modes of consensus hits.

- Verify that compounds form key interactions with the target protein.

- Select final hits that satisfy both ligand-based similarity and structure-based interaction criteria.

Diagram 2: Hybrid Virtual Screening Strategy

Application in Chemogenomic Library Design

The strategic integration of SBDD and LBDD approaches is particularly valuable in chemogenomic library design, where the goal is to create compound collections that efficiently explore chemical space against multiple targets within a protein family [1]. This integrated approach enables the design of targeted libraries with optimized properties for specific target classes while maintaining sufficient diversity to explore novel chemotypes.

Targeted Library Design Protocol

Step 1: Target Family Analysis

- Identify conserved structural features and binding site characteristics across the protein family.

- Analyze known ligands to identify common pharmacophoric elements and privileged substructures.

Step 2: Multi-Target Compound Profiling

- Perform docking studies against representative structures from different subfamilies.

- Apply ligand-based similarity methods to identify compounds with potential polypharmacology.

- Prioritize compounds with balanced affinity profiles across multiple targets of interest.

Step 3: Diversity-Oriented Synthesis Planning

- Design compound libraries that explore key regions of chemical space relevant to the target family.

- Incorporate structural features that address both conserved and divergent regions of binding sites.

- Apply computational filters to ensure favorable drug-like properties and synthetic accessibility.

Benchmarking and Validation

Robust benchmarking is essential for evaluating the performance of virtual screening methods in chemogenomic applications. The Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD) provides a validated set of benchmarks specifically designed to minimize bias in enrichment calculations [41]. This benchmark set includes physically matched decoys that resemble active ligands in their physical properties but differ topologically, providing a rigorous test for virtual screening methods.

Table 3: Benchmarking Metrics for Virtual Screening

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | (Hitssampled / Nsampled) / (Hitstotal / Ntotal) | Measures concentration of actives in top ranks |

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | Area under ROC curve | Overall performance across all rankings |

| Robust Initial Enhancement (RIE) | Weighted average of early enrichment | Early recognition capability |

| BedROC | Boltzmann-enhanced discrimination ROC | Emphasizes early enrichment with parameter α |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of SBDD and LBDD strategies requires access to specialized computational tools, databases, and resources. The following table outlines essential research reagents and their applications in computational drug discovery.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | PDB, PDBj, wwPDB | Source of experimental protein structures for SBDD |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, ChEMBL, DrugBank | Collections of screening compounds with annotated activities |

| Docking Software | AutoDock, GOLD, Glide, DOCK | Structure-based virtual screening and pose prediction |

| Ligand-Based Tools | OpenBabel, RDKit, Canvas | Molecular descriptor calculation and similarity searching |

| Benchmarking Sets | DUD, DUD-E, DEKOIS | Validated datasets for method evaluation and comparison |

| Visualization Software | PyMOL, Chimera, Maestro | Analysis and visualization of protein-ligand interactions |