Comparative Genomics in P-type ATPase Inhibitor Discovery: From Target Identification to Therapeutic Applications

This article explores the transformative role of comparative genomics in discovering and developing P-type ATPase inhibitors, a class of enzymes crucial for cellular ion homeostasis and promising therapeutic targets.

Comparative Genomics in P-type ATPase Inhibitor Discovery: From Target Identification to Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of comparative genomics in discovering and developing P-type ATPase inhibitors, a class of enzymes crucial for cellular ion homeostasis and promising therapeutic targets. We examine foundational concepts of P-type ATPase diversity and evolution across species, detailing bioinformatic methodologies for identifying and characterizing these transporters in genomic data. The content addresses key challenges in inhibitor development, including selectivity and resistance, while highlighting validation strategies through case studies like antimalarial spiroindolones and anticancer polyoxovanadates. By integrating genomic insights with structural biology and chemical genomics, this resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for leveraging comparative genomics in next-generation therapeutic discovery targeting P-type ATPases.

P-type ATPases: Evolutionary Biology and Genomic Diversity

P-type ATPases constitute a large group of evolutionarily related ion and lipid pumps found in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes [1]. These integral membrane proteins are characterized by their formation of a covalent aspartyl-phosphorylated intermediate (hence "P-type") during their catalytic cycle [2]. This highly conserved reaction mechanism, which involves the auto-phosphorylation of a key aspartate residue, couples ATP hydrolysis to the active transport of substrates across cellular membranes against their electrochemical gradients [1] [3].

As primary active transporters, P-type ATPases perform fundamental physiological functions across all domains of life. They establish and maintain essential electrochemical gradients that drive numerous cellular processes, including nerve impulse transmission, muscle relaxation, nutrient absorption, kidney secretion, and intracellular signaling [1] [4]. The most prominent members of this superfamily include the sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+-ATPase), calcium pumps (Ca2+-ATPases), proton pumps (H+-ATPases), and heavy metal transporters [1] [2]. Additionally, certain P-type ATPases function as phospholipid flippases, maintaining asymmetric lipid distribution across biomembranes—a critical process for membrane biogenesis and function [4].

The first P-type ATPase discovered was the Na+/K+-ATPase, isolated by Jens Christian Skou in 1957, which later earned him a Nobel Prize [1]. Since this seminal discovery, the superfamily has expanded considerably through genome sequencing efforts, revealing remarkable diversity in substrate specificity and physiological roles while maintaining conserved structural and mechanistic features.

Structural Organization and Conserved Domains

P-type ATPases share a common structural architecture centered around a single catalytic subunit ranging from 70-140 kDa [1]. While variations exist between subfamilies, most members feature a conserved core structure consisting of cytoplasmic domains and a transmembrane section [1] [5].

Transmembrane Domain

The transmembrane domain typically comprises ten alpha-helices (M1-M10) that form the pathway for substrate translocation across the lipid bilayer [1]. These helices are organized into a core transport domain (M1-M6) containing the substrate-binding sites, and a support domain (M7-M10) that provides structural stability [1]. Notable exceptions include P1A ATPases with 7 transmembrane helices, P1B ATPases with 8, and P5 ATPases with 12 transmembrane segments [1]. The transport mechanism involves substrate access through a half-channel to the binding site located near the midpoint of the membrane, followed by release through another half-channel on the opposite side [1].

Cytoplasmic Domains

The cytoplasmic portion contains three principal domains that coordinate ATP hydrolysis and energy transduction:

Phosphorylation (P) Domain: This domain contains the conserved DKTGT motif where the aspartate residue (D) undergoes phosphorylation during the catalytic cycle [1]. The P domain exhibits a Rossmann fold with a seven-strand parallel β-sheet and eight short associated α-helices, characteristic of the haloacid dehalogenase (HAD) superfamily [1]. The phosphorylation occurs via an SN2 reaction mechanism, as observed in structural studies of SERCA1a with ADP and AlF4− [1].

Nucleotide Binding (N) Domain: Serving as a built-in protein kinase, the N domain contains the ATP-binding pocket and functions to phosphorylate the P domain [1]. This domain consists of a seven-strand antiparallel β-sheet flanked by two helix bundles, positioned to interact with the P-domain during catalysis [1].

Actuator (A) Domain: The smallest of the three cytoplasmic domains, the A domain acts as a built-in protein phosphatase that dephosphorylates the phosphorylated P domain [1]. It features a distorted jellyroll structure and two short helices, with a highly conserved TGES motif that is crucial for its dephosphorylation function [1]. The A domain serves as a mechanical actuator, transducing energy from ATP hydrolysis in the cytoplasmic domains to conformational changes in the transmembrane domain that drive substrate translocation [1].

Table 1: Core Structural Domains of P-type ATPases

| Domain | Key Features | Conserved Motifs | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmembrane Domain | 6-12 α-helices | Substrate-specific binding residues | Substrate recognition and translocation |

| Phosphorylation (P) Domain | Rossmann fold, 7-strand β-sheet | DKTGT (phosphorylation site) | Forms aspartyl-phosphorylated intermediate |

| Nucleotide Binding (N) Domain | 7-strand antiparallel β-sheet | ATP-binding pocket | Binds ATP and phosphorylates P domain |

| Actuator (A) Domain | Distorted jellyroll structure | TGES | Dephosphorylates P domain, mechanical transduction |

Some P-type ATPases possess additional regulatory domains, such as N- and C-terminal heavy metal-binding domains in P1B pumps, autoinhibitory domains in P2B Ca2+ ATPases that bind calmodulin, and C-terminal regulatory domains in P3A plasma membrane proton pumps that control pump activity through phosphorylation [1].

Classification System

The P-type ATPase superfamily is classified into major types (P1-P5) based on phylogenetic analysis of conserved sequence motifs, substrate specificity, and structural features [1] [2] [5]. This classification system, initially proposed by Axelsen and Palmgren in 1998 and subsequently expanded, reflects both evolutionary relationships and functional specialization [1] [6].

Diagram 1: P-type ATPase Classification and Substrate Specificity

Type I ATPases (Heavy Metal Pumps)

P1A ATPases represent a specialized group found in bacteria and archaea that function in potassium import [2]. Unlike most P-type ATPases, P1A members operate as part of a heterotetrameric complex (KdpFABC) where the actual potassium transport is mediated by the KdpA subunit, while KdpB provides the ATPase activity [1] [2].

P1B ATPases are heavy metal transporters responsible for the homeostasis and detoxification of soft Lewis acids including Cu+, Ag+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, and Co2+ [1] [2]. These pumps are present in all kingdoms of life and are particularly abundant in prokaryotes, where they constitute key elements for metal resistance [1] [6]. P1B ATPases typically feature 6-8 transmembrane helices and often contain additional N-terminal metal-binding domains that receive metals from chaperone proteins like CopZ before transport [1].

Type II ATPases (Cation Pumps)

P2A ATPases include the well-characterized sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases (SERCAs) that maintain calcium homeostasis by pumping Ca2+ into intracellular stores [2] [5]. These pumps play critical roles in muscle contraction, cell signaling, and neuronal function.

P2B ATPases are autoinhibited Ca2+-ATPases located at plasma membranes (PMCAs) and other cellular membranes in plants and animals [2]. They are regulated by calmodulin binding, which relieves autoinhibitory constraints in their N- or C-terminal domains in response to elevated calcium levels [1] [2].

P2C ATPases comprise the Na+/K+ and H+/K+ pumps that are essential for maintaining electrochemical gradients in animal cells [2] [5]. The Na+/K+-ATPase, the first discovered P-type ATPase, creates the sodium gradient that drives numerous secondary transport processes and maintains membrane potential in excitable cells [1].

P2D ATPases represent unique Na+ or K+ pumps found in fungi, protozoans, and bryophytes but absent in higher plants, where they contribute to salt tolerance [2].

Type III ATPases (H+ and Mg2+ Pumps)

P3A ATPases are plasma membrane H+-ATPases predominantly found in plants and fungi [2] [5]. These proton pumps generate proton motive force by extruding H+ from the cell, thereby establishing electrochemical gradients that energize secondary active transport [5]. In plants, PM H+-ATPases regulate cell expansion, stomatal opening, phloem loading, and numerous stress responses [5].

P3B ATPases function as Mg2+ transporters across bacterial plasma membranes [5].

Type IV and V ATPases

P4 ATPases act as phospholipid flippases that catalyze the transverse movement of phospholipids across cellular membranes, maintaining membrane asymmetry and supporting vesicle budding in the endocytic pathway [2] [5]. These pumps are found exclusively in eukaryotes and have been linked to various human diseases when dysfunctional [4].

P5 ATPases represent the least characterized family, restricted to eukaryotic inner membranes with substrates that remain largely unknown [2]. Recent evidence suggests they may function as polyamine exporters or play roles in protein folding and quality control [5].

Table 2: Comprehensive Classification of P-type ATPases

| Type | Subfamily | Main Substrates | Organismal Distribution | Key Physiological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1A | P1A | K+ | Bacteria, Archaea | Potassium uptake (KdpFABC complex) |

| P1B | P1B | Cu+, Ag+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, Co2+ | All kingdoms | Heavy metal homeostasis & detoxification |

| P2A | P2A | Ca2+ | Eukaryotes | SR/ER calcium storage (SERCA) |

| P2B | P2B | Ca2+ | Plants, Animals | Plasma membrane calcium extrusion (PMCA) |

| P2C | P2C | Na+/K+, H+/K+ | Animals | Electrochemical gradient generation |

| P2D | P2D | Na+, K+ | Fungi, Protozoa, Bryophytes | Salt tolerance |

| P3A | P3A | H+ | Plants, Fungi | Plasma membrane proton gradient generation |

| P3B | P3B | Mg2+ | Bacteria | Magnesium transport |

| P4 | P4 | Phospholipids | Eukaryotes | Membrane asymmetry (flippases) |

| P5 | P5 | Unknown/Polyamines | Eukaryotes | Endomembrane function, possibly polyamine export |

Transport Mechanism and Reaction Cycle

The catalytic mechanism of P-type ATPases follows a conserved reaction cycle known as the Post-Albers scheme, which involves alternating between at least two major conformational states designated E1 and E2 [1]. This mechanism ensures the coupled translocation of substrates against their concentration gradients through the energy derived from ATP hydrolysis.

The E1-E2 Transition Cycle

The generalized transport reaction for P-type ATPases is:

nLigand1 (out) + mLigand2 (in) + ATP → nLigand1 (in) + mLigand2 (out) + ADP + Pi [1]

The E1 conformation exhibits high affinity for the exported substrate on the cytoplasmic side, while the E2 conformation has high affinity for the imported substrate on the extracellular or luminal side [1]. The cycle comprises four cornerstone states with additional intermediates:

E1 State: The pump binds the cytoplasmic substrate (ion or phospholipid) with high affinity.

E1~P: ATP binding and hydrolysis leads to phosphorylation of the conserved aspartate residue in the P domain, forming a high-energy aspartyl-phosphoanhydride intermediate.

E2P: The protein undergoes a conformational change that occludes the substrate and reorients the binding sites toward the opposite side of the membrane.

E2-P*: The substrate is released, and the pump becomes susceptible to dephosphorylation.

E1/E2: Dephosphorylation by the A domain returns the pump to the E1 conformation, completing the cycle [1].

Diagram 2: P-type ATPase Reaction Cycle (Post-Albers Scheme)

This mechanism ensures the strict coupling of ATP hydrolysis to substrate transport, with the free energy of ATP hydrolysis driving the conformational changes that result in vectorial substrate movement. The A domain plays a pivotal role in this process by translating the chemical energy from ATP hydrolysis in the cytoplasmic domains into mechanical work for substrate translocation through the transmembrane domain [1].

Physiological Roles and Relevance to Human Health

P-type ATPases perform diverse physiological functions across all organisms, with particular importance in higher eukaryotes where they contribute to specialized tissue functions and whole-organism homeostasis [1] [4].

Essential Physiological Processes

In humans, P-type ATPases serve as the basis for nerve impulse propagation, muscle relaxation, secretion and absorption in the kidney, and nutrient absorption in the intestine [1]. The Na+/K+-ATPase maintains the resting membrane potential essential for neuronal excitability and drives secondary active transport processes [4]. Ca2+-ATPases (SERCAs and PMCAs) regulate intracellular calcium signaling, muscle contraction, and neurotransmitter release [4]. The H+/K+-ATPase in gastric parietal cells acidifies the stomach lumen for digestion [1].

Disease Associations

Dysfunction of P-type ATPases is linked to numerous human diseases, making them promising targets for therapeutic intervention [4]:

Neurological Disorders: Mutations in the alpha2 and alpha3 subunits of Na+/K+-ATPase cause rapid-onset dystonia-parkinsonism, familial hemiplegic migraine, and alternating hemiplegia of childhood [4].

Genetic Diseases: Mutations in Cu2+-ATPases (ATP7A and ATP7B) cause Menkes and Wilson disease, disorders of copper metabolism with neurological and hepatic manifestations [4]. Mutations in SERCA calcium pumps can lead to heart failure, Brody myopathy, and Darier disease [4].

Metabolic and Other Disorders: Deficiencies in phospholipid flippases have been linked to progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, obesity, diabetes, hearing loss, and various neurological diseases [4]. Dysregulation of Na+/K+-ATPase and plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPases may contribute to cancer progression [4].

Adaptation to Environmental Stress

In prokaryotes and unicellular eukaryotes, P-type ATPases primarily function in protection from extreme environmental stress [6]. Heavy metal P1B ATPases confer resistance to toxic metal concentrations, while P3A H+-ATPases help maintain intracellular pH homeostasis under acidic or alkaline conditions [6]. This adaptive function is particularly evident in extremophilic bacteria and environmental microorganisms like Enterobacter xiangfangensis, which possesses robust arsenals of P-type ATPases for heavy metal resistance and ionic stress tolerance [7].

Experimental Approaches for P-type ATPase Research

Genomic Identification and Bioinformatics

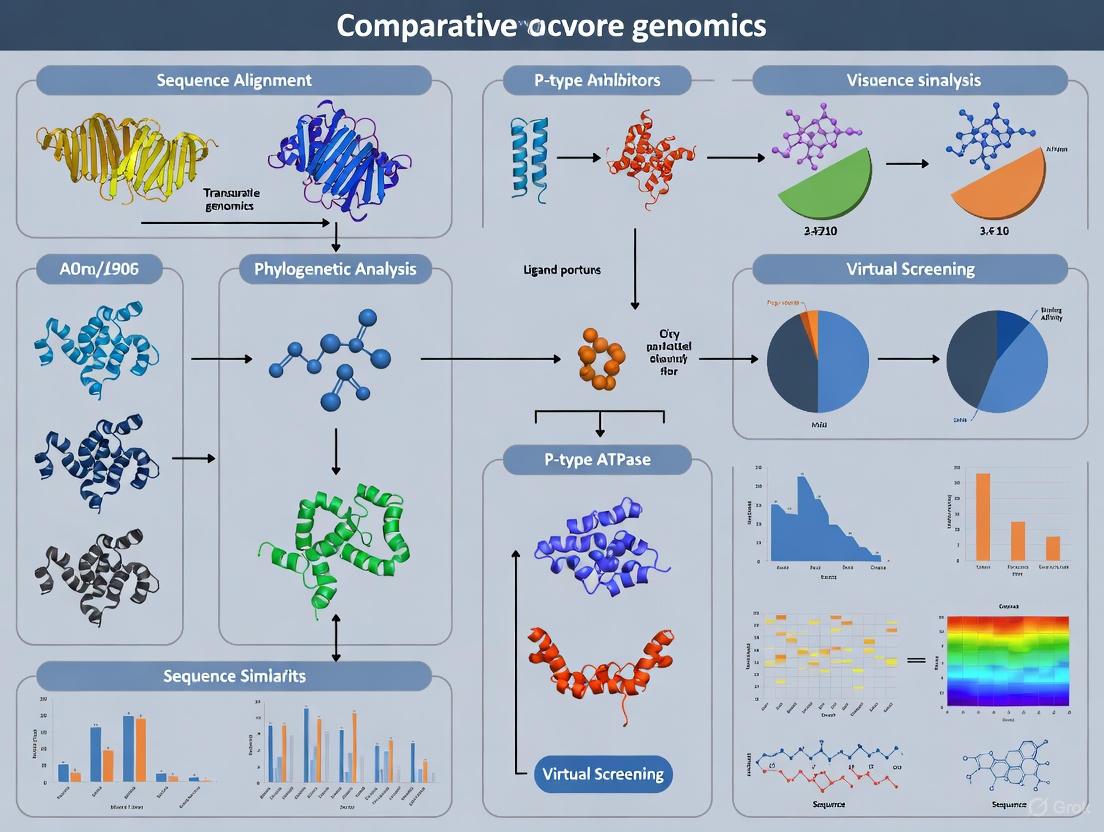

Comparative genomics has become a powerful approach for identifying and classifying P-type ATPases across diverse organisms [7] [8]. The standard methodology involves:

Sequence Retrieval: Whole genome sequencing provides the fundamental data for ATPase identification. For example, the Enterobacter xiangfangensis MDMC82 genome was sequenced using Illumina MiSeq technology with paired-end reads [7].

Hidden Markov Model (HMM) Searches: Profile HMMs for P-type ATPase domains (e.g., PF00122 or IPR006534) from databases like Pfam are used to screen proteomes [8]. The HMMER software package implements this with commands like

hmmsearch --domtblout output_file pfam_hmm protein_fasta.Domain Validation: Candidate sequences are verified using domain prediction tools such as SMART (Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool) and NCBI's Conserved Domain Database (CDD) to ensure the presence of characteristic P-type ATPase domains [8].

Phylogenetic Analysis: Multiple sequence alignment of identified ATPases followed by phylogenetic tree construction using maximum likelihood methods (e.g., with MEGA11 or IQ-TREE software) reveals evolutionary relationships and classifies ATPases into specific subfamilies [7] [8].

Functional Characterization

Functional studies employ biochemical, genetic, and cellular approaches:

ATPase Activity Assays: Enzymatic activity is measured by monitoring ATP hydrolysis, typically using colorimetric phosphate detection methods (e.g., malachite green assay) under various ionic conditions [9] [10]. For example, PfATP4 showed Na+-dependent ATPase activity inhibited by known antimalarials like Cipargamin [10].

Inhibitor Screening: Virtual screening of compound libraries followed by experimental validation identifies potential inhibitors. Docking-based screening of ~260,000 compounds from the NCI library identified pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine-3-carboxamide analogs as RUVBL1/2 ATPase inhibitors [9].

Gene Expression Analysis: Quantitative RT-PCR assesses ATPase expression under different conditions. In Puccinia striiformis, PMA gene expression varied significantly under temperature stress and during host infection [8].

Structural Studies: Cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography provide high-resolution structural insights. The recent 3.7 Å cryo-EM structure of native PfATP4 revealed a previously unknown binding partner, PfABP, highlighting the importance of endogenous protein purification [10].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Research Tool | Specific Example | Application/Function | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMMER Software | PF00122 HMM profile | Identification of P-type ATPases in genomic sequences | Genome-wide identification of PsPMA genes in wheat stripe rust [8] |

| Illumina Sequencing | MiSeq platform | Whole genome sequencing | Genomic analysis of Enterobacter xiangfangensis MDMC82 [7] |

| Cryo-EM | 300kV cryo-electron microscope | High-resolution structure determination | 3.7 Å structure of native PfATP4 from Plasmodium falciparum [10] |

| ATPase Activity Assay | Malachite green phosphate detection | Measurement of ATP hydrolysis activity | Na+-dependent ATPase activity of PfATP4 [10] |

| Virtual Screening | AutoDock 4.2.6 | In silico inhibitor identification | Screening of NCI library for RUVBL1/2 inhibitors [9] |

| qRT-PCR | SYBR Green protocol | Gene expression quantification | Expression analysis of PMA genes under temperature stress [8] |

Diagram 3: Experimental Workflow for P-type ATPase Characterization

Implications for Inhibitor Discovery through Comparative Genomics

The comparative genomics approach provides powerful insights for P-type ATPase inhibitor discovery, particularly through identification of species-specific adaptations and essential pathogen targets [7] [10] [8].

Target Identification in Pathogens

Comparative analysis of P-type ATPases across organisms reveals potential targets for antimicrobial development. For example, P3A H+-ATPases in fungi represent attractive antifungal targets since they are essential for fungal viability and pathogenicity but structurally distinct from mammalian P-type ATPases [8]. The identification of six PMA genes in the wheat stripe rust pathogen Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici through genomic analysis provides specific targets for developing novel antifungal agents [8].

The malarial parasite target PfATP4, a P2-type Na+ pump, exemplifies successful target identification through comparative genomics [10]. Structural studies of PfATP4 revealed unique features including an apicomplexan-specific binding partner (PfABP) not found in human hosts, presenting opportunities for selective inhibitor design [10]. Resistance mutations in PfATP4 (e.g., G358S, A211V) that arise under drug pressure map to specific structural regions, informing strategies for next-generation inhibitors that overcome resistance [10].

Cancer Therapeutics

The RUVBL1 and RUVBL2 AAA+ ATPases, though not classical P-type ATPases, demonstrate the principle of targeting essential ATPases in cancer [9]. These proteins are overexpressed in multiple cancer types and their inhibition disrupts chromatin remodeling complexes and cancer cell proliferation [9]. Virtual screening approaches identified pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine-3-carboxamides as RUVBL1/2 inhibitors with IC50 values of ~6 μM, demonstrating the feasibility of structure-based inhibitor discovery [9].

Environmental Adaptation Insights

Genomic analysis of extremophilic bacteria like Enterobacter xiangfangensis from desert environments reveals how P-type ATPases contribute to stress adaptation [7]. These organisms possess expanded repertoires of heavy metal and ion-transporting ATPases that enable survival under extreme conditions [7]. Understanding these adaptive mechanisms may inspire strategies for manipulating P-type ATPases in industrial or agricultural applications.

The integration of comparative genomics with structural biology and functional assays creates a powerful pipeline for identifying and validating P-type ATPases as drug targets, with particular promise for developing next-generation antimicrobials and anticancer therapies. As structural information expands and genomic databases grow, the potential for selective inhibitor design against pathogen-specific P-type ATPases continues to increase, offering new avenues for therapeutic intervention against infectious diseases, cancer, and other pathological conditions.

Comparative Genomics Reveals Evolutionary Conservation and Divergence

Comparative genomics has emerged as a pivotal methodology for elucidating the evolutionary conservation and divergence of protein families, providing critical insights for modern drug discovery. This whitepaper examines how comparative genomic approaches are revolutionizing the identification and characterization of P-type ATPases—an ancient superfamily of membrane transporter proteins with broad therapeutic potential. By integrating findings from recent structural studies, genomic analyses, and functional assays, we demonstrate how evolutionary patterns within this superfamily inform the rational design of inhibitors. Focusing specifically on the development of antimalarial therapeutics targeting PfATP4, we highlight how conserved functional domains and lineage-specific adaptations create unique targeting opportunities. This technical guide provides researchers with comprehensive methodologies, data frameworks, and visualization tools to advance the discovery of next-generation P-type ATPase inhibitors.

P-Type ATPase Superfamily: Classification and Physiological Significance

P-type ATPases constitute a large superfamily of ATP-driven transporter pumps that facilitate the transmembrane movement of charged substrates against concentration gradients. These enzymes are characterized by the formation of a phosphorylated intermediate (aspartyl-phosphate) during their catalytic cycle, which gives the "P-type" designation [11] [12]. These molecular pumps are found across all three domains of life and perform essential physiological functions including nerve impulse propagation, muscle contraction, nutrient absorption, and ion homeostasis [12]. The superfamily transports diverse substrates including H+, Na+/K+, Ca2+, heavy metals, and phospholipids [11] [12].

Phylogenetic analyses classify P-type ATPases into five major branches (P1-P5) with distinct substrate specificities and structural features [11] [13] [12]. The recent expansion of genomic data has revealed additional subgroups, with 13 newly identified families of unknown specificity awaiting functional characterization [12]. This diversity, coupled with their essential physiological roles, makes P-type ATPases promising targets for therapeutic intervention in numerous diseases.

Comparative Genomics in Evolutionary Analysis

Comparative genomics provides powerful computational frameworks for analyzing sequence conservation and divergence across evolutionary timescales. This approach enables researchers to identify functionally critical regions through conservation patterns, trace lineage-specific adaptations, and reconstruct evolutionary histories of protein families. For P-type ATPases, comparative analyses have revealed that despite fundamental conservation of the core catalytic mechanism, substantial structural and functional divergence has occurred across subgroups [13] [12].

The analytical power of comparative genomics stems from integrating multiple data types:

- Sequence comparisons: Identifying conserved motifs and catalytic residues

- Structural analyses: Resolving variations in membrane topology and domain architecture

- Phylogenetic reconstruction: Elucidating evolutionary relationships across taxa

- Genomic context analysis: Examining gene arrangements and regulatory elements

When applied to drug target discovery, these methods help distinguish conserved functional domains (which may cause off-target effects if inhibited) from pathogen-specific features that enable selective targeting.

Structural and Functional Diversity of P-Type ATPases

Conserved Core Structure and Catalytic Mechanism

All P-type ATPases share a common structural "core" consisting of three cytoplasmic domains and a transmembrane domain. The cytoplasmic domains include: the phosphorylation (P) domain containing the conserved aspartate residue that undergoes phosphorylation; the nucleotide-binding (N) domain that binds ATP; and the actuator (A) domain that coordinates conformational changes [10] [12]. The transmembrane domain typically comprises 6-10 helices that form the transport pathway and substrate-binding sites.

The catalytic cycle alternates between two principal conformational states (E1 and E2), driven by ATP hydrolysis and aspartyl-phosphate formation [8]. During this process, the enzyme undergoes substantial conformational changes that enable substrate transport against concentration gradients. Key conserved motifs include DKTGT (involved in phosphorylation), TGDN (in the nucleotide-binding domain), and PEGL (in the actuator domain) [12].

Evolutionary Divergence and Subgroup Specialization

Despite structural conservation, P-type ATPases have diversified significantly across evolution. P5 ATPases, which mark the origin of eukaryotes, exemplify this divergence. Phylogenetic evidence divides P5 ATPases into two distinct subgroups: P5A ATPases localize to the endoplasmic reticulum and function in protein maturation, while P5B ATPases localize to vacuolar/lysosomal membranes and play roles in neuronal health [13]. These subgroups differ in membrane topology, with P5A possessing two additional transmembrane segments and P5B having one extra transmembrane segment compared to other P-type ATPases [13].

Table 1: Major P-Type ATPase Subgroups and Their Characteristics

| Subgroup | Primary Substrates | Cellular Localization | Biological Functions | Therapeutic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1B | Heavy metals (Cu+, Zn2+, Cd2+) | Plasma membrane | Detoxification, copper homeostasis | Wilson disease, anticancer strategies |

| P2A & P2B | Ca2+ | Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum, plasma membrane | Muscle contraction, signaling | Heart failure, neurological disorders |

| P3A | H+ | Plasma membrane | pH homeostasis, nutrient transport | Antifungal drug target |

| P4 | Phospholipids | Plasma membrane | Membrane asymmetry | Neurological disorders |

| P5A & P5B | Unknown (possibly proteins) | ER (P5A), vacuolar/lysosomal (P5B) | Protein maturation, neuronal health | Parkinson's disease, cancer |

| P3A (Pathogen) | H+ | Plasma membrane | pH regulation, virulence | Antifungal, antimalarial targets |

Recent genomic analyses continue to reveal unexpected diversity within this superfamily. In the wheat stripe rust pathogen (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici), six P-type ATPase IIIA (PMA) genes were identified with distinct expression patterns under temperature stress and during host infection [8]. This expansion and specialization highlights how comparative genomics can identify pathogen-specific adaptations that may be exploited therapeutically.

Case Study: PfATP4 as a Model for Inhibitor Discovery

Target Validation and Essential Function inPlasmodium falciparum

PfATP4, a P2-type Na+ efflux pump in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, represents a promising antimalarial target with multiple compound classes under investigation. This cation pump maintains low intracellular Na+ concentrations (~10 mM) against the high Na+ environment of the bloodstream (~135 mM), which is essential for parasite survival [10]. PfATP4 inhibition causes rapid parasite death through disruption of Na+ homeostasis and colloid osmotic collapse, demonstrating its critical physiological function.

Genetic evidence further validates PfATP4 as a drug target. Ortholog replacement studies in P. knowlesi demonstrated that drug sensitivity is determined by PfATP4 primary sequence [10]. Additionally, resistance mutations in PfATP4 have emerged under drug pressure both in vitro and in clinical isolates, providing compelling genetic evidence that these compounds act directly on PfATP4 [10].

Structural Insights from Cryo-EM Analysis

Recent advances in cryo-electron microscopy have enabled high-resolution structural analysis of PfATP4 purified directly from CRISPR-engineered parasites. The 3.7 Å resolution structure reveals the canonical P-type ATPase architecture with five conserved domains: extracellular loop (ECL) domain, transmembrane domain (TMD), nucleotide-binding (N) domain, phosphorylation (P) domain, and actuator (A) domain [10].

The structure provides unprecedented insights into inhibitor binding and resistance mechanisms. The ion-binding site is located between TM4, TM5, TM6, and TM8, with all Na+-coordinating sidechains conserved and positioned similarly to corresponding residues in SERCA Ca2+-ATPase [10]. Most significantly, the structure revealed a previously unknown apicomplexan-specific binding partner, termed PfABP, which forms a conserved interaction with TM9 of PfATP4 [10]. This discovery presents an entirely new avenue for designing PfATP4 inhibitors that target this essential protein-protein interaction.

Resistance Mapping and Conservation Analysis

Comparative analysis of resistance mutations across PfATP4 isoforms reveals key functional regions and conserved residues. Mutations conferring resistance to the spiroindolone Cipargamin cluster around the Na+ binding site within the TMD [10]. Notably, the G358S/A mutation found in recrudescent parasites from clinical trials is located on TM3 adjacent to the Na+ coordination site, where it may block Cipargamin binding by introducing a bulkier sidechain into the inhibitor binding pocket [10].

Table 2: PfATP4 Resistance Mutations and Their Mechanisms

| Mutation | Drug Selectivity | Structural Location | Proposed Resistance Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| G358S/A | Cipargamin, (+)-SJ733 | TM3, adjacent to Na+ site | Steric hindrance in inhibitor binding pocket |

| A211V | PA21A092 (increased susceptibility to Cipargamin) | TM2, near ion-binding site | Conformational change affecting binding |

| L263V | Spiroindolones | TM2 | Altered access to binding pocket |

| V223M | Pyrazoleamides | ECL | Modified extracellular access route |

Strikingly, the A211V mutation conferring resistance to the pyrazoleamide PA21A092 paradoxically increases susceptibility to Cipargamin [10]. This demonstrates how understanding subtle differences in binding modes can inform combination therapies that suppress resistance emergence.

Experimental Methodologies for Comparative Genomic Analysis

Genomic Sequencing and Assembly

High-quality genome sequences form the foundation for comparative analyses. For the Enterobacter xiangfangensis MDMC82 strain isolated from the Merzouga desert, genomic DNA was extracted using the standard phenol-chloroform method and quantified with a Quantus fluorometer [7]. Sequencing libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT DNA sample preparation kit, and sequencing was performed in paired-end mode using an Illumina MiSeq instrument [7]. Generated reads were de novo assembled using SPAdes v3.11.1, with subsequent annotation via the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) v.6.2 [7].

For phylogenetic placement, assemblies can be submitted to the Type Strain Genome Server (TYGS) for whole genome-based identification [7]. Core genome phylogenies are constructed by extracting conserved sequences using Roary v.3.13.0 and building maximum likelihood trees with IQ-TREE software using appropriate evolutionary models and bootstrap validation [7].

Identification of P-Type ATPase Genes

Genome-wide identification of P-type ATPases employs hidden Markov model (HMM) profiles based on conserved domains. For analyzing the wheat stripe rust pathogen, researchers constructed an HMM file using the Pfam database to obtain the comparison file for the P-type ATPase IIIA gene subfamily domain (IPR006534) [8]. TBtools software was used to perform HMM searches against the pathogen protein database, followed by manual validation of domains using SMART and NCBI CDD to remove sequences lacking authentic P-type ATPase domains [8].

This bioinformatic pipeline identified six PMA genes in the Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici CYR34 race, designated PsPMA01-PsPMA06 [8]. The encoded proteins ranged from 811 to 960 amino acids, each containing a typical ATPase IIIA H superfamily domain distributed across four chromosomes [8].

Functional Annotation and Comparative Genomics

Functional annotation of genomes identifies genes involved in specific biological processes. For E. xiangfangensis MDMC82, researchers constructed a comprehensive database of genes associated with environmental adaptation through literature searches, then manually examined PGAP annotations to identify targeted genes [7]. Absent genes were further investigated using BLASTp searches against both PGAP and RAST outputs with an e-value cutoff of 1E-05 [7].

Pan-genome analysis assesses genetic diversity within species. Protein-coding gene clusters are identified with at least 95% sequence identity using Roary v.3.13.0, with results processed through Pagoo v.0.3.1.7 and Heap's law alpha value estimated using the R package micropan v.2.1 [7]. Core and accessory genes are functionally categorized by RPS-BLAST against clusters of orthologous groups (COGs) database using COGclassifier [7].

Structural Analysis Techniques

Cryo-electron microscopy has become indispensable for determining high-resolution structures of challenging membrane proteins like P-type ATPases. For PfATP4, researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 to insert a 3×FLAG epitope tag at the C-terminus in Dd2 P. falciparum parasites [10]. The protein was affinity-purified from parasites cultured in human red blood cells and demonstrated Na+-dependent ATPase activity inhibitable by known PfATP4 inhibitors [10]. Single-particle cryo-EM at 3.7 Å resolution enabled de novo modeling of 982 of 1264 residues, revealing unexpected structural features including the PfABP binding partner [10].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for P-Type ATPase Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq | Whole genome sequencing | Paired-end mode for coverage |

| Assembly Tools | SPAdes v3.11.1 | De novo genome assembly | Optimized for bacterial genomes |

| Annotation Pipelines | NCBI PGAP v6.2 | Automated gene annotation | Standardized functional assignments |

| Domain Databases | Pfam, SMART, NCBI CDD | Domain identification and validation | IPR006534 for P-type ATPase IIIA |

| HMM Search Tools | TBtools, HMMER | Gene family identification | Custom HMM profiles |

| Phylogenetic Software | IQ-TREE v2.2.0.3, MEGA11 | Evolutionary relationship inference | Maximum likelihood methods |

| Pan-genome Analysis | Roary v3.13.0, Pagoo v0.3.1.7 | Core/accessory genome determination | 95% sequence identity threshold |

| Structural Biology | Cryo-EM single particle analysis | Membrane protein structure determination | 3.7 Å resolution demonstrated for PfATP4 |

| Gene Editing | CRISPR-Cas9 | Endogenous tagging and validation | C-terminal 3×FLAG tagging for purification |

| Functional Validation | Na+-dependent ATPase assay | Target engagement confirmation | Inhibitor sensitivity profiling |

Visualization of P-Type ATPase Structure-Function Relationships

Discussion and Future Perspectives

Comparative genomics has fundamentally transformed our understanding of P-type ATPase evolution, revealing both deeply conserved functional mechanisms and lineage-specific structural adaptations. The integration of genomic, structural, and functional data creates powerful frameworks for rational inhibitor design, particularly for infectious disease targets like PfATP4. Several key principles emerge from current research:

First, evolutionary conservation patterns reliably identify functionally critical regions that may represent resistance hotspots if targeted. The clustering of resistance mutations around the PfATP4 ion-binding site underscores the functional importance of this region while highlighting the challenge of designing durable inhibitors against conserved catalytic sites.

Second, lineage-specific innovations provide unique targeting opportunities. The discovery of PfABP as an apicomplexan-specific binding partner of PfATP4 demonstrates how comparative genomics can identify pathogen-specific features that enable selective targeting without host cross-reactivity [10].

Third, integrated multi-omics approaches are essential for comprehensive target validation. The combination of comparative genomics, structural biology, functional assays, and resistance mapping provides orthogonal validation of target-inhibitor interactions and mechanisms of action.

Future directions in P-type ATPase inhibitor discovery will likely focus on targeting allosteric sites, protein-protein interactions, and species-specific structural features identified through expanded comparative analyses. The continued expansion of genomic databases, coupled with advances in structural prediction algorithms, will further accelerate the identification and validation of novel targets within this therapeutically important protein superfamily.

Bioinformatic Characterization of ATPase Families Across Eukaryotes

P-type ATPases constitute a large superfamily of primary active transporters that are critical for maintaining cellular homeostasis across all domains of life. This technical guide provides a comprehensive bioinformatic characterization of ATPase families within eukaryotic systems, focusing on their phylogenetic distribution, structural features, and functional specialization. Framed within the context of discovering novel P-type ATPase inhibitors through comparative genomics, this review integrates current structural biology findings with established classification systems to present a roadmap for target identification and validation in drug development programs. We provide detailed methodologies for phylogenetic analysis, structural characterization, and functional annotation that enable researchers to identify evolutionarily conserved motifs and organism-specific adaptations critical for selective inhibitor design.

P-type ATPases are biological pumps with diverse substrate specificities that share a common catalytic mechanism involving auto-phosphorylation of a conserved aspartate residue [14]. The name "P-type" derives from this transient phosphorylation event that occurs during the transport cycle [15]. These molecular pumps are found in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes, highlighting their fundamental role in cellular physiology [1]. Since Jens Christian Skou's discovery of the first P-type ATPase (Na+/K+-ATPase) in 1957, which earned him the Nobel Prize in 1997, this superfamily has expanded to include numerous transporters with diverse substrate specificities [14].

The significance of P-type ATPases in eukaryotic biology cannot be overstated. In humans, they serve as the basis for nerve impulses, muscle relaxation, renal secretion and absorption, intestinal nutrient uptake, and numerous other physiological processes [1]. From a pharmacological perspective, many P-type ATPases represent validated drug targets, with inhibitors already in clinical use or under development for conditions ranging from fungal infections to malaria [16] [17]. The comparative genomics approach to understanding ATPase families across eukaryotes provides a powerful framework for identifying new targets for therapeutic intervention while anticipating resistance mechanisms that may arise during treatment.

Classification and Phylogenetic Distribution

Historical Classification System

The P-type ATPase superfamily is historically divided into five major families (P1-P5) based on phylogenetic analysis of conserved sequence kernels, excluding the highly variable N and C terminal regions [14] [15]. A sixth family (P6) has since been identified. This classification system, initially proposed by Axelsen and Palmgren in 1998 after analyzing 159 sequences, remains the foundation for understanding the evolutionary relationships and functional diversification of these transporters [1] [14].

Table 1: Major P-type ATPase Families in Eukaryotes

| Family | Subfamilies | Main Substrates | Cellular Localization | Representative Members |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P1A, P1B | K+, Heavy metals (Cu+, Zn2+, Cd2+) | Plasma membrane | ATP7A, ATP7B (humans) |

| P2 | P2A, P2B, P2C, P2D | Ca2+, Na+, K+, H+ | SR/ER, Plasma membrane, Secretory pathway | SERCA, PMCA, Na+/K+-ATPase |

| P3 | P3A, P3B | H+, Mg2+ | Plasma membrane | AHA2 (A. thaliana), Pma1 (S. cerevisiae) |

| P4 | Multiple classes | Phospholipids | Various membranes | ATP8A1, ATP8B1, ATP11C |

| P5 | - | Unknown | Intracellular membranes | ATP13A2 |

| P6 | - | - | - | - |

Evolutionary Relationships

Phylogenetic analysis reveals that the diversification of the P-type ATPase family occurred prior to the separation of eubacteria, archaea, and eukaryota, underlining the significance of this protein family for cell survival under stress conditions [1]. The evolutionary relationship between families remains uncertain as the nodes at the central parts of the unrooted tree lack statistical support [14]. This deep evolutionary conservation makes comparative genomics particularly valuable for identifying functionally critical regions that can be targeted for therapeutic intervention.

Notably, different P-type ATPase families show distinct phylogenetic distributions. P1A ATPases (potassium pumps) are found only in prokaryotes, while P4 and P5 ATPases are unique to eukaryotes where they are omnipresent [14]. The heavy metal-transporting P1B ATPases are more common in archaea and bacteria but maintain important representatives in eukaryotic systems, where they function primarily in metal homeostasis and detoxification [15].

Structural Features and Functional Mechanisms

Conserved Structural Domains

All P-type ATPases share a common structural organization featuring a single catalytic subunit of 70-140 kDa with multiple functional domains [1]. The first structure of a P-type ATPase, the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA1a), was published in a landmark paper by Toyoshima et al. in 2001, and it is generally acknowledged that the structure of SERCA1a is representative for the superfamily of P-type ATPases [14].

Table 2: Characteristic Structural Domains of P-type ATPases

| Domain | Abbreviation | Function | Key Motifs | Role in Catalytic Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmembrane | M | Substrate binding and transport | Varies by family | Forms pathway for substrate translocation |

| Phosphorylation | P | Accepts phosphoryl group | DKTGT (D is phosphorylated) | Forms aspartyl-phosphoanhydride intermediate |

| Nucleotide-binding | N | ATP binding and hydrolysis | Multiple conserved residues | Serves as built-in protein kinase |

| Actuator | A | Dephosphorylation | TGES | Serves as built-in protein phosphatase |

| Support | S | Structural support | Varies | Stabilizes transmembrane domain |

The transmembrane domain (M) typically has ten transmembrane helices (M1-M10), with the binding sites for transported ligand(s) located near the midpoint of the bilayer [1]. The cytoplasmic section consists of three domains: the phosphorylation (P) domain containing the conserved aspartate residue that gets phosphorylated; the nucleotide-binding (N) domain that binds ATP; and the actuator (A) domain that facilitates dephosphorylation [1] [14].

Transport Mechanism

P-type ATPases follow an alternating access mechanism with two major conformations termed E1 and E2 (short for Enzyme1 and Enzyme2; the phosphorylated forms are denoted E1P and E2P, respectively) [14]. According to the Post-Albers model, the pump alternates between inward-facing E1 and outward-facing E2 conformations [14]. The conformational changes are induced by phosphorylation of E1, and E1P is spontaneously converted to E2P. Dephosphorylation of E2P is followed by the spontaneous conversion of E2 to E1 [14].

The generalized reaction for P-type ATPases is: nLigand1 (out) + mLigand2 (in) + ATP → nLigand1 (in) + mLigand2 (out) + ADP + Pi where the ligand can be either a metal ion or a phospholipid molecule [1].

Diagram 1: P-type ATPase catalytic cycle illustrating E1-E2 conformational transitions

Methodological Approaches for Bioinformatic Characterization

Sequence Identification and Retrieval

The initial step in characterizing ATPase families across eukaryotic species involves comprehensive identification of putative P-type ATPase sequences. This process typically begins with database mining using known P-type ATPase sequences as queries.

Protocol 4.1.1: Sequence Identification Pipeline

Query Selection: Identify representative P-type ATPase sequences from well-characterized model organisms (e.g., human, yeast, Arabidopsis). The Prosite motif PS00154 provides a useful starting point [1].

Database Search: Perform BLASTP searches against non-redundant (NR) protein sequence databases from target eukaryotic species. Use an expectation value (E) threshold of 0.01 for inclusion [18].

Iterative Search: Conduct iterative database searches using PSI-BLAST program with position-specific scoring matrices (PSSMs) until convergence to identify distant homologs [18].

Sequence Retrieval: Compile identified sequences and remove duplicates. For genome-wide analyses, search annotated genomes for sequences containing characteristic P-type ATPase motifs.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Reconstructing evolutionary relationships among identified ATPase sequences is essential for proper classification and functional prediction.

Protocol 4.2.1: Phylogenetic Reconstruction

Multiple Sequence Alignment: Use programs such as T_Coffee or PCMA followed by manual correction based on PSI-BLAST results to generate accurate alignments [18]. Focus on conserved catalytic regions while excluding highly variable terminal regions.

Tree Construction: Generate phylogenetic trees using appropriate algorithms (maximum likelihood, Bayesian inference). The analysis should be based on the conserved sequence kernel excluding the highly variable N and C terminal regions [14].

Statistical Validation: Assess node support using bootstrap analysis (minimum 100 replicates) or posterior probabilities. Note that nodes at the central parts of the tree may lack statistical support [14].

Family Assignment: Classify sequences into established families (P1-P6) based on their phylogenetic clustering with known representatives.

Structural Modeling and Validation

For ATPases without experimental structures, homology modeling provides insights into potential drug binding sites and functional mechanisms.

Protocol 4.3.1: Homology Modeling of P-type ATPases

Template Identification: Identify suitable structural templates (e.g., SERCA1a, PDB: 1SU4) using sequence similarity searches. SERCA1a is generally acknowledged as representative for the superfamily of P-type ATPases [1].

Model Building: Generate three-dimensional models using automated homology modeling servers or software (e.g., MODELLER).

Model Refinement: Manually adjust regions corresponding to substrate specificity determinants and known resistance mutation sites.

Validation: Verify model quality using structural validation tools (e.g., MolProbity). Compare with experimental structures when available. For example, recent cryoEM structures of PfATP4 revealed significant differences (RMSDs of 10.3-22.9 Å) from previous homology models [16].

Diagram 2: Bioinformatic workflow for characterizing ATPase families

Case Studies in Eukaryotic ATPases

Plasmodium falciparum ATPases as Antimalarial Targets

PfATP4, a sodium efflux pump in the malaria parasite P. falciparum, represents a promising antimalarial target whose inhibition induces rapid parasite clearance in vivo [16]. Recent structural studies have revealed important insights that guide inhibitor design.

Structural Insights: A 3.7 Å resolution cryoEM structure of PfATP4 purified from CRISPR-engineered P. falciparum parasites revealed all five canonical P-type ATPase domains and, notably, a previously unknown, apicomplexan-specific binding partner, PfABP (PfATP4-Binding Protein) [16] [10]. This discovery presents an unexplored avenue for designing PfATP4 inhibitors that target this protein-protein interaction.

Resistance Mutations: Mutations in PfATP4 are associated with resistance against several chemical classes of antimalarial drug candidates. For example, G358S/A mutations, found in recrudescent parasites during Cipargamin Phase 2b clinical trials, confer high-level resistance [16]. Mapping these mutations onto structural models reveals they cluster around the proposed Na+ binding site within the transmembrane domain, suggesting potential mechanisms for interference with drug binding.

Fungal H+-ATPases as Antifungal Targets

The plasma membrane H+-ATPase (Pma1) of fungi is a established target for antifungal development. Structural studies have facilitated the design of novel inhibitor classes with broad-spectrum antifungal activity.

Tetrahydrocarbazole Inhibitors: A series of tetrahydrocarbazoles has been identified as novel P-type ATPase inhibitors that depolarize the fungal plasma membrane and exhibit broad-spectrum antifungal activity [17]. Crystallographic structure determination of a SERCA-tetrahydrocarbazole complex at 3.0 Å resolution revealed the binding site to be a region above the ion inlet channel of the ATPase [17].

Selectivity Challenges: Comparative inhibition studies indicate that many tetrahydrocarbazoles also inhibit mammalian Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and Na+,K+-ATPase with even higher potency than Pma1, highlighting the importance of leveraging comparative genomics to identify fungal-specific structural features for selective inhibitor design [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for ATPase Characterization Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Example Specific Items | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Expression Systems | Production of recombinant ATPases for structural/ biochemical studies | Pichia pastoris, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Baculovirus-insect cell systems | PfATP4 expression failed in heterologous systems, necessitating endogenous purification [16] |

| Affinity Tags | Protein purification for structural biology | 3×FLAG epitope, His-tag, Strep-tag | C-terminal 3×FLAG tag used for endogenous PfATP4 purification [16] |

| ATPase Activity Assays | Functional characterization of ATP hydrolysis | Colorimetric phosphate detection, Coupled enzyme assays | Na+-dependent ATPase activity inhibited by PfATP4 inhibitors PA21A092 and Cipargamin [16] |

| Structural Biology Platforms | High-resolution structure determination | Cryo-electron microscopy, X-ray crystallography | 3.7 Å cryoEM structure of PfATP4 [16]; 3.0 Å crystal structure of SERCA-tetrahydrocarbazole complex [17] |

| Genome Engineering Tools | Endogenous tagging and functional studies | CRISPR-Cas9, Homologous recombination | CRISPR-Cas9 used for C-terminal tagging of PfATP4 in Dd2 P. falciparum parasites [16] |

| Inhibitor Compounds | Mechanistic studies and validation | Cipargamin, PA21A092, Tetrahydrocarbazoles, Ouabain, Thapsigargin | Used for functional validation and resistance mechanism studies [16] [17] [15] |

Implications for Inhibitor Discovery

The bioinformatic characterization of ATPase families across eukaryotes provides critical insights for rational inhibitor design. Comparative genomics reveals both conserved structural elements that can be targeted with broad-spectrum compounds and lineage-specific adaptations that enable selective targeting of pathogenic organisms.

Leveraging Conservation: The deep evolutionary conservation of catalytic mechanisms and core structural elements means that insights from well-studied model ATPases (e.g., SERCA) can inform drug discovery programs targeting less characterized ATPases in pathogens. The conserved aspartate residue in the DKTGT motif and the overall domain architecture provide frameworks for designing mechanism-based inhibitors [1] [14].

Exploiting Diversity: Variations in transmembrane domains, accessory subunits, and regulatory mechanisms offer opportunities for developing selective inhibitors. The discovery of PfABP as an apicomplexan-specific modulator of PfATP4 exemplifies how organism-specific adaptations can reveal novel therapeutic avenues [16]. Similarly, the structural differences in the ATP-binding site between PfATP4 and SERCA (e.g., M620 sidechain flipping into the ATP-binding pocket) represent potential selectivity determinants [16].

Anticipating Resistance: Bioinformatic analyses that map resistance-conferring mutations onto structural models help predict clinical resistance mechanisms and guide the development of next-generation inhibitors less susceptible to these mutations. The clustering of PfATP4 resistance mutations around the ion-binding site informs the design of compounds that interact with less mutable regions [16].

The bioinformatic characterization of ATPase families across eukaryotes reveals a remarkable balance of evolutionary conservation and functional diversification. The integrated approach combining phylogenetic analysis, structural modeling, and functional validation provides a powerful framework for target selection and inhibitor design in drug discovery programs. As structural information continues to expand through cryoEM and other techniques, and as genomic data from diverse eukaryotic species become available, our ability to design selective and potent P-type ATPase inhibitors will continue to improve. The ongoing challenges of drug resistance in infectious diseases and the need for novel therapeutic targets in non-communicable diseases ensure that ATPases will remain important subjects of research for the foreseeable future.

Calcium (Ca²⁺) is a universal intracellular messenger governing processes from muscle contraction and neurotransmission to gene expression and apoptosis. Maintaining the precise submicromolar cytosolic Ca²⁺ concentration is critical, as dysregulation is cytotoxic and implicated in numerous pathologies, including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [19] [20]. The P-type ATPase superfamily includes primary active transporters that use energy from ATP hydrolysis to move ions across membranes. This whitepaper focuses on three pivotal Ca²⁺ transport systems: the Plasma Membrane Ca²⁺-ATPase (PMCA), the Sarco/Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca²⁺-ATPase (SERCA), and the Secretory Pathway Ca²⁺-ATPase (SPCA) [21] [19].

These pumps constitute the core "Ca²⁺ toolkit" for restoring basal Ca²⁺ levels following signaling events. PMCAs extrude Ca²⁺ to the extracellular space, while SERCAs and SPCAs sequester Ca²⁺ into intracellular stores [21] [19]. Their distinct functions, regulatory mechanisms, and tissue distributions make them compelling model systems for fundamental research on P-type ATPase mechanics and for targeted drug discovery. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these pumps, framed within the context of discovering novel inhibitors through comparative genomics and structural biology.

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of PMCA, SERCA, and SPCA, highlighting their distinct and shared features.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Calcium ATPases

| Feature | PMCA (P2B) | SERCA (P2A) | SPCA (P2A) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Location | Plasma Membrane | Sarcoplasmic/Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane | Golgi Apparatus and Secretory Pathway Membranes |

| Primary Function | Ca²⁺ Extrusion from cytosol to extracellular space | Ca²⁺ Sequestration from cytosol to ER/SR lumen | Ca²⁺ and Mn²⁺ sequestration into Golgi lumen [19] [22] |

| Transport Stoichiometry | 1 Ca²⁺ / 1 ATP (Ca²⁺:H⁺ exchanger) [21] | 2 Ca²⁺ / 1 ATP [23] | 1 Ca²⁺ / 1 ATP [19] |

| Ca²⁺ Affinity | High (Kd < 1 µM after activation) [21] | Low-Moderate | High |

| Transport Capacity | Low | High | Moderate |

| Key Regulators | Calmodulin (CaM), Phosphoinositides (e.g., PtdIns(4,5)P₂), Protein Kinases (PKA, PKC) [24] [21] | Phospholamban, Sarcolipin, Phosphoinositides [23] [19] | Phosphoinositides [19] |

| Physiological Role | Fine-tuning cytosolic Ca²⁺; terminating Ca²⁺ signals [21] | Controlling Ca²⁺ stores for signaling; muscle relaxation | Golgi function, protein processing, and Mn²⁺ homeostasis [19] |

Molecular Architecture and Transport Mechanisms

Conserved Core Structure of P-Type ATPases

PMCAs, SERCAs, and SPCAs share a common structural blueprint characterized by ten transmembrane helices (M1-M10) and three cytosolic domains: the Actuator (A-domain), Phosphorylation (P-domain), and Nucleotide-binding (N-domain) [24] [21]. The catalytic cycle, known as the Post-Albers cycle, involves transient phosphorylation of a conserved aspartate residue in the P-domain (hence "P-type") [24] [23]. This cycle drives conformational transitions between two principal states: E1 (with ion-binding sites facing the cytosol) and E2 (with ion-binding sites facing the membrane's opposite side) [23].

Distinctive Features and Regulatory Mechanisms

Plasma Membrane Ca²⁺-ATPase (PMCA)

PMCAs are distinguished by their ultrafast transport rates (exceeding 5,000 cycles per second), which are essential for terminating rapid Ca²⁺ signals, such as those in neurons [24]. A key regulatory mechanism involves the phospholipid PtdIns(4,5)P₂, which acts as a "latch" to promote fast Ca²⁺ release and enable counter-ion passage, maintaining the kilohertz-cycle rate [24]. PMCAs feature a long C-terminal tail containing an auto-inhibitory domain that binds to receptor sites on the cytosolic loops. The binding of calmodulin (CaM) to this tail relieves the autoinhibition, dramatically increasing the pump's Ca²⁺ affinity [21]. Additionally, PMCAs form heterodimeric complexes with accessory subunits like neuroplastin and basigin, which are crucial for their native function [24].

Sarco/Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca²⁺-ATPase (SERCA)

SERCAs have a higher transport capacity but lower Ca²⁺ affinity compared to PMCAs. Their activity is finely tuned by small transmembrane regulator proteins: phospholamban (in cardiac muscle) and sarcolipin (in skeletal muscle), which inhibit SERCA activity in a dephosphorylated state [23]. The SERCA transport cycle is well-characterized, involving the coordinated binding of two Ca²⁺ ions from the cytosol and their release into the ER lumen. A critical kink in the M1 transmembrane helix, often mediated by a conserved glycine or proline, facilitates gate closure during ion binding [24].

Secretory Pathway Ca²⁺-ATPase (SPCA)

SPCAs are unique in their ability to transport both Ca²⁺ and Mn²⁺ into the Golgi lumen. This dual specificity is vital for the function of Golgi-resident glycosyltransferases and other Mn²⁺-dependent enzymes, linking calcium homeostasis to protein processing and secretion [19].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools for Calcium ATPase Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function/Application | Key Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Affinity Inhibitors | Mechanistic studies, probing physiological roles, starting points for drug discovery. | Thapsigargin (SERCA-specific, arrests in E2 state) [23], Cyclopiazonic Acid (CPA) (SERCA inhibitor) [23], CURCUMIN (SERCA inhibitor, binds E1 state) [23]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM) | High-resolution structure determination of conformational states. | Revealed PMCA2-lipid interactions [24], identified novel binding protein PfABP in malaria PfATP4 [16]. |

| ATPase Activity Assays | Functional characterization of pump activity and inhibitor screening. | Coupled enzyme assays monitoring NADH oxidation; used to characterize curcumin inhibition [23]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Validating roles of specific residues in transport, regulation, and inhibitor binding. | Mapping drug resistance mutations in PfATP4 (e.g., G358S) [16]. |

| Genomic & Pan-Genome Analysis | Identifying genetic diversity, adaptive traits, and potential drug targets. | Uses tools like Roary, EDGAR; applied to Enterobacter [7] and Pantoea [25]. |

Experimental Protocols for Functional and Structural Analysis

Protocol: Cryo-EM Workflow for Determining Calcium ATPase Structures

This protocol, based on recent studies, outlines the process for resolving high-resolution structures of calcium pumps [24] [16].

- Protein Preparation: For eukaryotic pumps, generate a homogeneous sample. This may involve:

- CRISPR-Cas9 Engineering: Endogenously tag the protein (e.g., with a 3×FLAG epitope) in the host cell to facilitate purification [16].

- Expression in Knockout Cells: Use cells lacking accessory subunits (e.g., NPTN/BSG-knockout) to study the pump alone, or co-express with subunits for complex formation [24].

- Affinity Purification: Solubilize the protein from native membranes using detergents and purify via affinity chromatography (e.g., anti-FLAG resin) [16].

- Functional Validation: Confirm the protein is active after purification. Measure Na⁺- or Ca²⁺-dependent ATPase activity and its inhibition by known compounds to ensure functional integrity [16].

- Sample Vitrification: Trap the protein in different conformational states by modulating the buffer composition (e.g., presence/absence of ATP, Ca²⁺, or inhibitors). Apply the sample to cryo-EM grids and plunge-freeze in liquid ethane [24].

- Data Collection and Processing: Collect single-particle cryo-EM micrographs. Use computational software for 2D classification, 3D reconstruction, and model building to generate atomic structures [24].

Protocol: Assessing Inhibitor Potency via Coupled Enzyme Assay

This biochemical assay measures ATPase activity to determine inhibitor efficacy, as used in curcuminoid studies [23].

- Prepare Microsomal Fractions: Isolate membrane fractions containing the calcium ATPase from relevant tissue (e.g., rabbit skeletal muscle for SERCA) or cultured cells.

- Set Up Reaction Mixture: The assay cocktail typically contains:

- Assay buffer (e.g., 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EGTA).

- CaCl₂ to set a desired free Ca²⁺ concentration (e.g., 10 µM) to activate the pump.

- An ATP-regenerating system: Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), pyruvate kinase (PK), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

- The coupling enzyme reporter: NADH, whose oxidation is monitored spectrophotometrically at 340 nm.

- Inhibitor Incubation: Pre-incubate the microsomal membranes with varying concentrations of the test inhibitor (e.g., curcumin analogs dissolved in DMSO) for 15-30 minutes.

- Initiate Reaction and Monitor: Start the reaction by adding ATP. Continuously monitor the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm, which corresponds to ATP consumption.

- Data Analysis: Calculate ATPase activity rates from the linear slope of NADH oxidation. Plot activity versus inhibitor concentration to determine the IC₅₀ value.

Calcium ATPase Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the integrated roles of PMCAs, SERCAs, and SPCAs in cellular calcium signaling and the conceptual workflow for inhibitor discovery.

Diagram Title: Calcium Signaling and Inhibitor Discovery Workflow.

Comparative Genomics in P-Type ATPase Research and Inhibitor Discovery

The search for P-type ATPase inhibitors is powerfully augmented by comparative genomics, which identifies essential and conserved targets while predicting resistance mechanisms. This approach is particularly valuable for targeting pathogens and understanding adaptive evolution.

- Identifying Essential Genes in Pathogens: Genome-wide RNAi screens against Schistosoma mansoni identified 63 essential genes, many encoding enzymes like ATPases, which are high-value targets for anti-parasitic drugs [26]. This method prioritizes targets with homology to known druggable human proteins.

- Pan-genome Analysis for Adaptation: Studies on bacteria like Enterobacter xiangfangensis and Pantoea agglomerans use pan-genome analysis to differentiate core genes (essential functions) from accessory genes (niche-specific adaptations) [7] [25]. This helps identify conserved stress response pathways across taxa, revealing shared strategies that could be targeted by broad-spectrum inhibitors.

- Understanding Resistance: Comparative genomics of clinical and field isolates can map resistance-conferring mutations. For example, the G358S mutation in Plasmodium PfATP4 confers resistance to the antimalarial Cipargamin, and structural models show how this mutation physically blocks the drug-binding pocket [16]. This knowledge is crucial for designing next-generation inhibitors that circumvent existing resistance.

PMCAs, SERCAs, and SPCAs represent exemplary model systems within the P-type ATPase superfamily. Their intricate structures, distinct yet complementary physiological roles, and complex regulation make them fascinating subjects for basic research and attractive targets for therapeutic intervention. The ongoing structural biology revolution, led by cryo-EM, continues to provide unprecedented insights into their transport cycles and regulatory mechanisms. The integration of these structural data with functional genomics, advanced biochemical assays, and computational modeling creates a powerful pipeline for rational drug design. Future efforts will undoubtedly focus on exploiting species-specific differences and allosteric sites, revealed by structures like PfATP4-PfABP, to develop highly selective and effective inhibitors for treating human disease and parasitic infections [16].

Genomic Distribution and Phylogenetic Relationships of Target ATPases

P-type ATPases represent a large superfamily of primary active transporters that are pivotal to cellular homeostasis across all domains of life. These biological pumps, characterized by the formation of a phosphorylated intermediate during their catalytic cycle, drive the active transport of diverse substrates including ions and phospholipids. Within the context of drug discovery, particularly for infectious diseases and cancer, P-type ATPases have emerged as promising therapeutic targets due to their essential roles in pathogen viability and cellular signaling pathways. This technical review examines the genomic distribution, phylogenetic classification, and structural conservation of P-type ATPases through the lens of comparative genomics, providing a framework for the rational design of targeted inhibitors. By integrating recent advances in genomic analysis, structural biology, and bioinformatics, we outline a comprehensive strategy for identifying and validating P-type ATPases as targets for therapeutic intervention.

P-type ATPases constitute a large ancient superfamily of primary active pumps with diverse substrate specificities ranging from H+ to phospholipids [27]. The name "P-type" derives from their characteristic formation of a phosphorylated intermediate during catalysis at a conserved aspartate residue [1] [14]. These molecular pumps are found in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes, highlighting their fundamental role in cellular physiology [1]. The significance of these enzymes in biology cannot be overstated—they establish electrochemical gradients essential for nerve impulse propagation, muscle relaxation, kidney function, nutrient absorption, and numerous other physiological processes [12] [1].

All P-type ATPases share a common catalytic mechanism that alternates between high- and low-affinity conformations induced by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of a conserved aspartate residue [27]. This cycle, known as the Post-Albers mechanism, involves transitions between two major conformational states termed E1 and E2 [1] [14]. In the E1 state, the pump has high affinity for the exported substrate, while in the E2 state, it has high affinity for the imported substrate [1]. This alternating access mechanism enables the vectorial transport of substrates against their concentration gradients at the expense of ATP hydrolysis.

Structurally, P-type ATPases feature a conserved architecture consisting of three cytoplasmic domains (actuator [A], phosphorylation [P], and nucleotide-binding [N] domains) and a transmembrane domain (M) that contains the substrate-binding sites [1] [14]. The catalytic subunit typically ranges from 70-140 kDa, with various subfamilies requiring additional subunits for proper function [1]. The first P-type ATPase structure solved was the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA1a), which has served as a template for understanding the structure-function relationships across the entire superfamily [1].

Phylogenetic Classification and Genomic Distribution

Evolutionary History and Systematics

The phylogenetic analysis of P-type ATPases reveals an ancient origin with diversification occurring prior to the separation of eubacteria, archaea, and eukaryota [1]. Initial classification in 1998 by Axelsen and Palmgren identified five major families (P1-P5) based on conserved sequence motifs excluding the highly variable N and C terminal regions [1] [14]. More recent analyses have confirmed these families and identified one additional family (P6 ATPases), though the evolutionary relationships between families remain uncertain due to lack of statistical support at the central nodes of phylogenetic trees [27] [14].

Table 1: Major Families of P-Type ATPases and Their Characteristics

| Family | Main Substrates | Representative Members | Organismal Distribution | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1A | K+ | KdpB | Prokaryotes only | Heterotetrameric complex (KdpFABC); 7 transmembrane helices |

| P1B | Heavy metals (Cu+, Ag+, Zn2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, Co2+) | HMA transporters | All domains of life | N- and C-terminal metal-binding domains; 8 transmembrane helices |

| P2A | Ca2+ | SERCA-type pumps | Eukaryotes | Endoplasmic reticulum localization; 10 transmembrane helices |

| P2B | Ca2+ | ACA-type pumps | Eukaryotes | Autoinhibited; calmodulin regulated; 10 transmembrane helices |

| P3A | H+ | PMA proteins | Eukaryotes | Plasma membrane localization; targets for antifungal drugs |

| P4 | Phospholipids | Flippases | Eukaryotes | Lipid translocation; 10 transmembrane helices |

| P5 | Unknown | P5 ATPases | Eukaryotes omnipresent | 12 transmembrane helices; function not fully characterized |

Comparative genomic analyses have revealed striking patterns in the distribution and expansion of P-type ATPase families across organisms. Arabidopsis thaliana contains 46 P-type ATPase genes, the largest number identified in any organism at the time of its genome sequencing, while rice (Oryza sativa) has 43 despite having a genome approximately 3.5 times larger [11]. This suggests that both dicots and monocots have evolved with a large preexisting repertoire of P-type ATPases rather than undergoing lineage-specific expansions [11]. In contrast, simpler eukaryotes such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae contain only 16 P-type ATPases [11].

The evolutionary conservation of P-type ATPases is further evidenced by comparisons of intron positions between rice and Arabidopsis orthologs, which show highly similar patterns within clusters despite approximately 200 million years of evolutionary divergence [11]. This phylogenetic analysis suggests that the common angiosperm ancestor had at least 23 P-type ATPases, providing the archetypal representatives for the clusters currently present in both plants [11].

Genomic Distribution Across Pathogens

The genomic distribution of P-type ATPases in pathogenic organisms reveals potential targets for therapeutic intervention. In the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, the sodium efflux pump PfATP4 (a type 2 cation pump) has emerged as a leading antimalarial target [10]. This essential P-type ATPase maintains sodium homeostasis in the parasite by actively extruding Na+ against the high sodium concentration in infected erythrocytes [10]. Similarly, in the wheat stripe rust pathogen Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, six P-type ATPase IIIA (PMA) genes have been identified, which appear crucial for managing temperature stress and pathogen infection [8].

The discovery of a previously unknown binding partner, PfABP (apicomplexan-specific essential binding partner), associated with PfATP4 in Plasmodium falciparum highlights the potential for species-specific targeting [10]. This conserved interaction presents an unexplored avenue for designing PfATP4 inhibitors that may have reduced off-target effects in host organisms [10].

Phylogenetic Classification of P-Type ATPase Families

Methodological Framework for Comparative Genomic Analysis

Genomic Mining and Identification Strategies

The identification of P-type ATPases in genomic sequences relies on characteristic signature motifs and conserved domains. The following methodological approaches represent current best practices:

Hidden Markov Model (HMM) Profiling: Construction of HMM files using resources such as the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/) to obtain comparison files for the P-type ATPase domains (e.g., IPR006534 for the P-type ATPase IIIA subfamily) [8]. These profiles are used to search protein databases using tools such as TBtools or HMMER.

Motif-Based Screening: Identification of conserved signature sequences, particularly the DKTGT motif (where the aspartate residue undergoes phosphorylation) and its variants (DKTGTLT, DKTGTIT, DKTGTVT, DKTGTMT, or DKTGTII) [1] [11]. This can be accomplished through BLAST searches against genomic databases.

Domain Validation: Manual curation of candidate sequences using domain databases such as SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) and NCBI Conserved Domain Database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd/) to verify the presence of characteristic P-type ATPase domains and remove false positives [8].

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for P-Type ATPase Analysis

| Method | Application | Key Tools/Resources | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-wide identification | Cataloging complete repertoires | HMMER, BLAST, Pfam, SMART | Complete set of P-type ATPases in a genome |

| Phylogenetic analysis | Evolutionary relationships | MEGA11, ClustalX, IQ-TREE | Phylogenetic trees revealing family relationships |

| Motif and domain analysis | Functional annotation | CDD, SMART, InterPro | Conserved motifs and functional domains |

| Structural prediction | Structure-function insights | Homology modeling, RoseTTAFold, AlphaFold2 | 3D models of ATPase structures |

| Expression profiling | Regulatory patterns | RNA-seq, qRT-PCR, microarrays | Expression levels across tissues/conditions |

Phylogenetic Reconstruction and Pan-Genome Analysis

Comparative analysis of P-type ATPases across multiple genomes requires robust phylogenetic methods:

Sequence Alignment and Tree Construction: Protein sequences are typically aligned using tools such as ClustalX or MAFFT, with phylogenetic trees constructed using maximum likelihood methods (e.g., IQ-TREE) or neighbor-joining algorithms with appropriate bootstrap testing (e.g., 1000 replicates) [7] [8]. The GTR (General Time Reversible) model with rate heterogeneity among sites is commonly employed [7].

Pan-Genome Analysis: For assessing genetic diversity within species, pan-genome analysis using tools such as Roary can identify core and accessory genes with specified sequence identity thresholds (e.g., 95%) [7]. The resulting gene clusters can be functionally categorized using databases such as COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) [7].

Ortholog Identification: Putative orthologous relationships are determined through reciprocal best BLAST hits, synteny analysis, and conservation of intron positions [11]. In plants, the observation of highly conserved intron positions between rice and Arabidopsis P-type ATPases provides strong evidence for orthology [11].

Experimental Characterization of P-Type ATPase Function

Biochemical Assays for ATPase Activity

The functional characterization of P-type ATPases relies on biochemical assays that measure ATP hydrolysis activity: