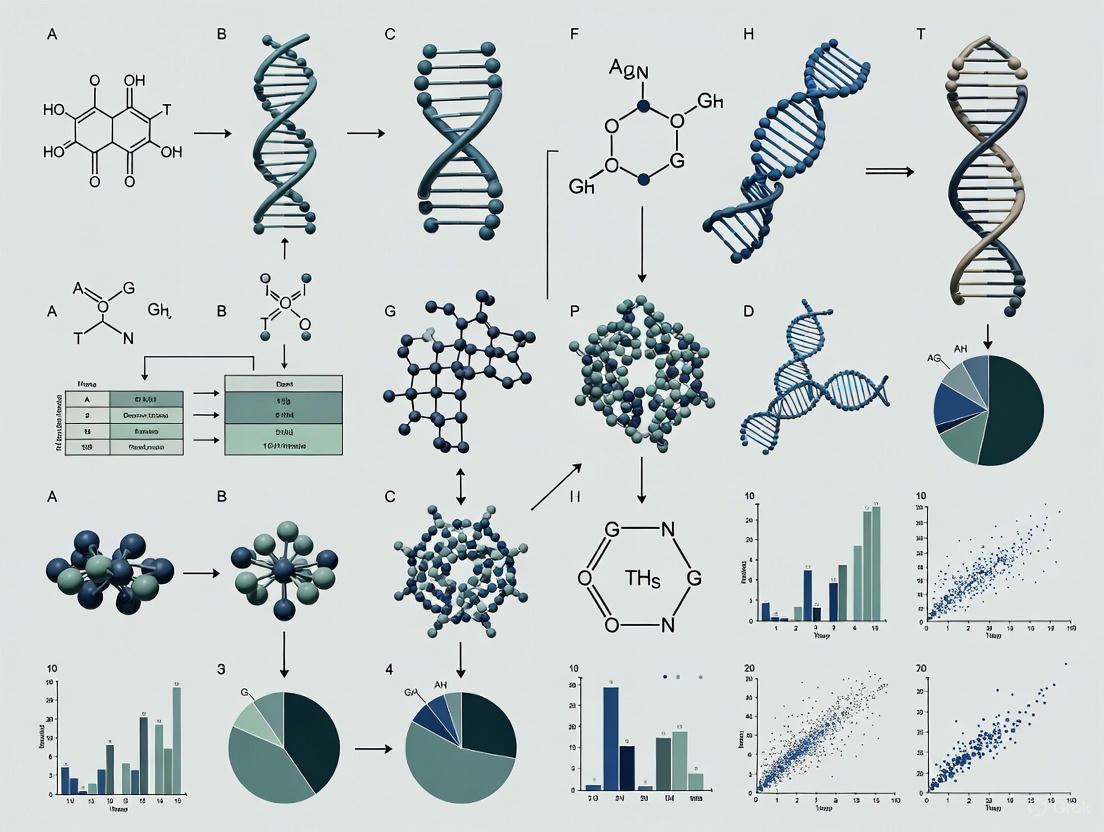

Comparative Chemical Genomics Across Species: Unlocking Evolutionary Secrets for Drug Discovery

Comparative chemical genomics is a powerful paradigm that systematically investigates the interactions of small molecules with biological systems across diverse species.

Comparative Chemical Genomics Across Species: Unlocking Evolutionary Secrets for Drug Discovery

Abstract

Comparative chemical genomics is a powerful paradigm that systematically investigates the interactions of small molecules with biological systems across diverse species. This approach is revolutionizing drug discovery by enabling rapid target identification and validation, while also providing fundamental insights into gene function and evolutionary biology. This article explores the foundational principles of chemical genomics, detailing advanced methodologies from high-throughput screening to machine learning. It addresses key challenges such as batch effects and data integration, while highlighting validation strategies that leverage cross-species comparisons. By synthesizing knowledge from model organisms to human biology, comparative chemical genomics offers a unique framework for developing targeted therapeutics and understanding the functional conservation of biological pathways.

Chemical Genomics Foundations: From Basic Concepts to Cross-Species Applications

Chemical genomics (also termed chemogenomics) is a systematic approach in drug discovery that screens targeted chemical libraries of small molecules against families of biological targets, with the parallel goals of identifying novel therapeutic compounds and their protein targets [1]. This field represents a fundamental shift from traditional single-target drug discovery by enabling the exploration of all possible drug-like molecules against all potential targets derived from genomic information [1]. The completion of the human genome project provided an abundance of potential therapeutic targets, making chemogenomics an increasingly powerful strategy for understanding biological systems and accelerating drug development [1].

Two complementary experimental approaches define the field: forward chemogenomics, which begins with a phenotypic screen to identify bioactive compounds whose molecular targets are subsequently identified, and reverse chemogenomics, which starts with a specific protein target and screens for compounds that modulate its activity [1]. Both strategies ultimately aim to connect small molecule perturbations to biological outcomes, creating "targeted therapeutics" that precisely modulate specific molecular pathways [1].

Table 1: Core Approaches in Chemical Genomics

| Approach | Starting Point | Screening Method | Primary Goal | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Chemogenomics | Phenotype of interest | Cell-based or organism-based phenotypic assays | Identify compounds inducing desired phenotype, then determine targets [1] | Discovery of novel drug targets and mechanisms [1] |

| Reverse Chemogenomics | Specific protein target | In vitro protein-binding or functional assays | Find compounds modulating specific target, then characterize phenotypic effects [1] | Target validation and drug optimization [1] |

Experimental Methodologies in Chemical Genomics

Forward Chemogenomics Workflow

Forward chemogenomics begins with the observation of a biological phenotype and works backward to identify the molecular targets responsible. The methodology typically involves several key stages:

Phenotypic Screening: Researchers first develop robust assays that measure biologically relevant phenotypes such as cell viability, morphological changes, or reporter gene expression in response to compound treatment [2]. These assays are typically conducted in disease-relevant cellular systems to maximize translational potential.

Hit Identification: Compound libraries are screened against the phenotypic assay to identify "hits" that produce the desired biological effect. These libraries may contain known bioactive compounds or diverse chemical structures.

Target Deconvolution: Once bioactive compounds are identified, the challenging process of target identification begins. Multiple experimental approaches are employed for this critical step:

Affinity-based pull-down methods: These techniques use small molecules conjugated with tags (such as biotin or fluorescent tags) to selectively isolate target proteins from complex biological mixtures like cell lysates [3]. The tagged small molecule serves as bait to capture binding partners, which are then identified through mass spectrometry [3].

Label-free methods: These approaches identify small molecule targets without chemical modification of the compound. Techniques include Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS), which exploits the protection against proteolysis that occurs when a small molecule binds to its target protein [3].

- Target Validation: Candidate targets are validated through genetic and biochemical approaches, including CRISPR-based gene editing, RNA interference, and biochemical confirmation of direct binding [4].

Reverse Chemogenomics Workflow

Reverse chemogenomics takes the opposite approach, beginning with a defined molecular target and progressing to phenotypic analysis:

Target Selection: Researchers select a specific protein target based on its suspected role in a biological pathway or disease process. This target is often a member of a well-characterized protein family such as kinases, GPCRs, or nuclear receptors [1].

In Vitro Screening: Compound libraries are screened against the purified target protein using biochemical assays that measure binding or functional modulation. High-throughput screening technologies enable testing of hundreds of thousands of compounds.

Hit Validation and Optimization: Primary screening hits are validated through dose-response experiments and counter-screens to eliminate false positives. Medicinal chemistry approaches then optimize validated hits to improve potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties.

Phenotypic Characterization: Optimized compounds are tested in cellular and organismal models to determine their biological effects and potential therapeutic utility [1].

Key Target Identification Technologies

Comparative Analysis of Target Identification Methods

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Small Molecule Target Identification

| Method | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity-Based Pull-Down | Uses tagged small molecules to isolate binding partners from biological samples [3] | Direct physical evidence of binding; works with complex protein mixtures [3] | Chemical modification may alter bioactivity; false positives from non-specific binding [3] | Identification of vimentin as target of withaferin A [3] |

| On-Bead Affinity Matrix | Immobilizes small molecules on solid support to capture interacting proteins [3] | High sensitivity; compatible with diverse detection methods [3] | Potential steric hindrance from solid support; requires sufficient binding affinity [3] | Identification of USP9X as target of BRD0476 [3] |

| Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS) | Explores proteolysis protection upon ligand binding without chemical modification [3] | No chemical modification required; uses native compound [3] | May miss low-affinity interactions; requires optimized proteolysis conditions [3] | Identification of eIF4A as target of resveratrol [3] |

| CRISPRres | Uses CRISPR-Cas-induced mutagenesis to generate drug-resistant protein variants [4] | Direct functional evidence; identifies resistance mutations in essential genes [4] | Limited to cellular contexts; technically challenging [4] | Identification of NAMPT as target of KPT-9274 [4] |

CRISPR-Based Approaches for Target Identification

The CRISPRres method represents a powerful genetic approach for target identification that exploits CRISPR-Cas-induced non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair to generate diverse protein variants [4]. This methodology involves:

Library Design: Designing sgRNA tiling libraries that target known or suspected drug resistance hotspots in essential genes.

Mutagenesis: Introducing CRISPR-Cas-induced double-strand breaks in the target loci, followed by error-prone NHEJ repair that generates a wide variety of in-frame mutations.

Selection: Applying drug selection pressure to enrich for resistant cell populations containing functional mutations that confer drug resistance.

Variant Identification: Sequencing the targeted loci in resistant populations to identify specific mutations that confer resistance, thereby nominating the drug target [4].

This approach was successfully applied to identify nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) as the cellular target of the anticancer agent KPT-9274, demonstrating its utility for deconvolution of small molecule mechanisms of action [4].

Chemical Genomics in Cross-Species Research

Comparative genomics provides a foundational framework for chemical genomics by enabling researchers to identify conserved biological pathways and species-specific differences that influence drug response [5]. The integration of these fields creates powerful opportunities for understanding drug action and improving therapeutic development.

Principles of Cross-Species Extrapolation

Cross-species extrapolation in chemical genomics relies on several key principles:

Genetic Conservation: Many genes and biological pathways are conserved across species, enabling researchers to use model organisms to study human biology and disease. For example, approximately 60% of genes are conserved between fruit flies and humans, and two-thirds of human cancer genes have counterparts in the fruit fly [5].

Functional Equivalence: Orthologous proteins often perform similar functions in different species, allowing compounds that modulate these targets in model systems to have translational potential for human therapeutics.

Adaptive Evolution: Different selective pressures across species can lead to functional divergence in drug targets, which must be considered when extrapolating results from model organisms to humans [6].

Table 3: Cross-Species Genomic Comparisons in Drug Discovery

| Comparison | Genomic Insights | Chemical Genomics Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human-Fly Comparison | ~60% gene conservation; 2/3 cancer genes have fly counterparts [5] | Use Drosophila models for initial compound screening and target validation [5] | [5] |

| Yeast-Human Comparison | Conserved cellular pathways; revised initial yeast gene catalogs [5] | Study fundamental cellular processes and identify conserved drug targets [5] | [5] |

| Mouse-Human Comparison | Similar gene regulatory systems demonstrated by ENCODE projects [5] | Preclinical validation of drug efficacy and safety [5] | [5] |

| Bird-Human Comparison | Gene networks for singing may relate to human speech and language [5] | Identify novel targets for neurological disorders [5] | [5] |

Applications in Invasion Genomics

Chemical genomics approaches are increasingly applied in invasion genomics to understand how invasive species adapt to new environments and to develop strategies for their control [6]. Key applications include:

Identification of Invasion-Related Genes: Genomic analyses can reveal genes under selection during invasion events, which may represent potential targets for species-specific control agents [6].

Understanding Adaptive Mechanisms: Studies of invasive species have identified several genomic mechanisms that facilitate adaptation to novel environments, including:

- Standing genetic variation: Pre-existing genetic diversity in native populations that provides substrate for rapid adaptation [6]

- Hybridization and introgression: Mixing of genetically distinct populations that increases adaptive potential [6]

- Gene flow: Maintenance of genetic connectivity that spreads beneficial alleles across populations [6]

- Development of Selective Control Agents: Chemical genomics approaches can identify compounds that specifically target invasive species while minimizing effects on non-target organisms, leveraging genomic differences between native and invasive species [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Chemical Genomics Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Tags | Enable purification and identification of small molecule-binding proteins [3] | Biotin tags for streptavidin pull-down; fluorescent tags for visualization [3] |

| Solid Supports | Provide matrix for immobilizing small molecules in affinity purification [3] | Agarose beads for on-bead affinity approaches [3] |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Generate targeted genetic variation for resistance screening [4] | SpCas9 and AsCpf1 for creating functional mutations in essential genes [4] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Identify proteins isolated through affinity-based methods [3] | LC-HRMS for protein identification and quantification [3] |

| Chemical Libraries | Provide diverse small molecules for screening against targets or phenotypes [1] | Targeted libraries for specific protein families; diverse libraries for phenotypic screening [1] |

| Model Organism Genomes | Enable comparative genomics and cross-species extrapolation [5] | Fruit fly, yeast, mouse genomes for evolutionary comparisons and target validation [5] |

Chemical genomics represents a powerful integrative approach that bridges small molecule chemistry and genomic science to accelerate therapeutic discovery. By systematically exploring the interactions between chemical compounds and biological targets, this field enables both the identification of novel drug targets and the development of targeted therapeutics. The continuing advancement of technologies such as CRISPR-based screening methods, improved affinity purification techniques, and sophisticated computational tools will further enhance our ability to connect small molecules to their genomic targets. As comparative genomics provides increasingly detailed insights into functional conservation and divergence across species, chemical genomics approaches will become even more precise and predictive, ultimately improving the success rate of therapeutic development and enabling more personalized treatment strategies.

Chemical genomics (or chemogenomics) is a systematic approach that screens libraries of small molecules against families of drug targets to identify novel drugs and drug targets [1]. It integrates target and drug discovery by using active compounds as probes to characterize proteome functions, with the interaction between a small compound and a protein inducing a phenotype that can be characterized and linked to molecular events [1]. This field is particularly powerful because it can modify protein function in real-time, allowing observation of phenotypic changes upon compound addition and interruption after its withdrawal [1]. Within this discipline, two complementary experimental approaches have emerged: forward (classical) chemogenomics and reverse chemogenomics, which differ in their starting points and methodologies but share the common goal of linking chemical compounds to biological functions [1].

Defining the Approaches

Forward Chemical Genomics

Forward chemical genomics begins with a phenotypic observation and works to identify the small molecules and their protein targets responsible for that phenotype [1]. This approach investigates a particular biological function where the molecular basis is unknown, identifies compounds that modulate this function, and then uses these modulators as tools to discover the responsible proteins [1]. For example, in a scenario where researchers observe a desired loss-of-function phenotype like arrest of tumor growth, they would first identify compounds that induce this phenotype, then work to identify the gene and protein targets involved [1]. The main challenge of this strategy lies in designing phenotypic assays that enable direct progression from screening to target identification [1].

Reverse Chemical Genomics

Reverse chemical genomics starts with a known protein target and searches for small molecules that specifically interact with it, then analyzes the phenotypic effects induced by these molecules [1]. Researchers first identify compounds that perturb the function of a specific enzyme in controlled in vitro assays, then analyze the biological response these molecules elicit in cellular systems or whole organisms [1]. This approach, which resembles traditional target-based drug discovery strategies, is enhanced by parallel screening capabilities and the ability to perform lead optimization across multiple targets belonging to the same protein family [1]. It is particularly valuable for confirming the biological role of specific enzymes and validating targets [1].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Forward and Reverse Chemical Genomics

| Characteristic | Forward Chemical Genomics | Reverse Chemical Genomics |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Observable phenotype | Known gene/protein target |

| Primary Goal | Identify modulating compounds and their molecular targets | Determine biological function of a specific target |

| Approach Nature | Hypothesis-generating, discovery-oriented | Hypothesis-driven, validation-focused |

| Typical Workflow | Phenotype → Compound screening → Target identification | Known target → Compound screening → Phenotypic analysis |

| Key Challenge | Designing assays that enable direct target identification | Connecting target modulation to relevant biological phenotypes |

Methodologies and Workflows

Experimental Design and Screening Strategies

Both forward and reverse chemical genomics approaches employ systematic screening strategies but differ fundamentally in their experimental design. Forward chemical genomics typically employs phenotypic screens on cells or whole organisms, where the readout is a measurable biological effect such as changes in cell morphology, proliferation, or reporter gene expression [1] [7]. These assays are designed to capture complex biological responses without requiring prior knowledge of specific molecular targets. In contrast, reverse chemical genomics often begins with target-based screens using purified proteins or defined cellular pathways, employing techniques such as enzymatic activity assays, binding studies, or protein-protein interaction assays to identify modulators of known targets [1].

The screening compounds themselves differ in these approaches. Forward chemical genomics often utilizes diverse, structurally complex compound libraries, including natural products from traditional medicines which have "privileged structures" that frequently interact with biological systems [1]. Reverse chemical genomics frequently employs more targeted libraries focused on specific protein families, containing known ligands for at least some family members under the principle that compounds designed for one family member may bind to others [1].

Workflow Comparison: Forward vs. Reverse Chemical Genomics

Target Identification and Validation Techniques

Target identification in forward chemical genomics represents one of the most challenging aspects of the approach. Once phenotype-modulating compounds are identified, several techniques can be employed to find their molecular targets, including affinity chromatography, protein microarrays, and chemical proteomics [1]. More recently, chemogenomic profiling has emerged as a powerful method that compares the fitness of thousands of mutants under chemical treatment to identify target pathways [8]. For instance, a study on Acinetobacter baumannii used CRISPR interference knockdown libraries screened against chemical inhibitors to elucidate essential gene function and antibiotic mechanisms [8].

In reverse chemical genomics, target validation typically involves demonstrating that the phenotypic effects of a compound are specifically mediated through its interaction with the intended target. This often employs genetic approaches such as RNA interference, CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, or the use of resistant target variants [9] [8]. The recent integration of CRISPR technologies with chemical screening has significantly enhanced both approaches, enabling more precise target validation and functional assessment [10] [8].

Table 2: Key Techniques in Forward and Reverse Chemical Genomics

| Application | Forward Chemical Genomics Techniques | Reverse Chemical Genomics Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Screening | Phenotypic assays on cells/organisms, high-content imaging | Target-based assays (binding, enzymatic activity) |

| Hit Identification | Compound library screening, structure-activity relationships | High-throughput screening, virtual screening |

| Target Identification | Affinity purification, chemical proteomics, chemogenomic profiling | Genetic manipulation (CRISPR, RNAi), resistant variants |

| Validation Methods | Genetic complementation, target engagement assays | Phenotypic rescue, pathway analysis, animal models |

Applications in Research and Drug Discovery

Determining Mechanisms of Action

Chemical genomics approaches have proven particularly valuable for determining the mechanism of action (MOA) of therapeutic compounds, especially those derived from traditional medicine systems [1]. Traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurvedic formulations contain compounds that are typically more soluble than synthetic compounds and possess "privileged structures" that frequently interact with biological targets [1]. Forward chemical genomics has been used to identify the molecular targets underlying the phenotypic effects of these traditional medicines. For example, studies on the therapeutic class of "toning and replenishing medicine" in TCM identified sodium-glucose transport proteins and PTP1B (an insulin signaling regulator) as targets linked to hypoglycemic activity [1]. Similarly, analysis of Ayurvedic anti-cancer formulations revealed enrichment for targets directly connected to cancer progression such as steroid-5-alpha-reductase and synergistic targets like the efflux pump P-gp [1].

Identifying Novel Drug Targets

Both approaches have demonstrated significant utility in identifying novel therapeutic targets, particularly for challenging areas like antibiotic development [1] [8]. Reverse chemical genomics profiling has been used to map existing ligand libraries to unexplored members of target families, as demonstrated in a study that mapped a murD ligase ligand library to other members of the mur ligase family (murC, murE, murF, murA, and murG) to identify new targets for known ligands [1]. This approach successfully identified potential broad-spectrum Gram-negative inhibitors since the peptidoglycan synthesis pathway is exclusive to bacteria [1]. Similarly, forward chemical genomics screens have identified essential gene vulnerabilities in pathogens like Acinetobacter baumannii, revealing potential new antibiotic targets by examining chemical-gene interactions across essential gene knockdowns [8].

Elucidating Biological Pathways

Chemical genomics has proven instrumental in elucidating complex biological pathways, sometimes resolving long-standing mysteries in biochemistry [1]. In one notable example, researchers used chemogenomics approaches to identify the enzyme responsible for the final step in the synthesis of diphthamide, a posttranslationally modified histidine derivative found on translation elongation factor 2 (eEF-2) [1]. Despite thirty years of study, the enzyme catalyzing the amidation of dipthine to diphthamide remained unknown. By leveraging Saccharomyces cerevisiae cofitness data - which measures similarity of growth fitness under various conditions between different deletion strains - researchers identified YLR143W as the strain with highest cofitness to strains lacking known diphthamide biosynthesis genes, subsequently confirming it as the missing diphthamide synthetase through experimental validation [1].

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Compound Libraries and Screening Platforms

The foundation of any chemical genomics approach is a well-characterized compound library. Targeted chemical libraries for reverse approaches often include known ligands for specific protein families, leveraging the principle that compounds designed for one family member may bind to others [1]. More diverse libraries for forward approaches may include natural products, such as those derived from sponges, which have been described as "the richest source of new potential pharmaceutical compounds in the world's oceans" [11]. High-throughput screening platforms enable the testing of these compound libraries against biological systems, ranging from in vitro enzymatic assays to whole-organism phenotypic screens [1] [7].

Genetic Tools and Model Systems

Modern chemical genomics heavily relies on genetic tools for target identification and validation. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) has emerged as a particularly powerful technology, using a deactivated Cas9 protein (dCas9) directed by single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) to specifically knockdown gene expression without eliminating gene function [8]. This approach enables the study of essential genes in bacteria and other organisms [8]. Model organisms ranging from yeast to zebrafish and mice continue to play crucial roles in chemical genomics, with each offering specific advantages for different biological questions [10] [9].

Omics Technologies and Bioinformatics

Advanced omics technologies and bioinformatic analysis form the analytical backbone of modern chemical genomics. Chemogenomic profiling generates massive datasets that require sophisticated computational tools for interpretation [12] [8]. For example, a 2025 study on Acinetobacter baumannii employed chemical-genetic interaction profiling to measure phenotypic responses of CRISPRi knockdown strains to 45 different chemical stressors, generating complex datasets that revealed essential gene networks and informed antibiotic function [8]. Integration of phenotypic and chemoinformatic data allows researchers to identify potential target pathways for inhibitors and distinguish physiological impacts of structurally related compounds [8].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Targeted chemical libraries, natural product collections, FDA-approved drug libraries | Source of small molecule modulators for screening |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPRi knockdown libraries, RNAi collections, transposon mutant libraries | Target identification and validation |

| Screening Platforms | High-throughput phenotypic assays, high-content imaging systems, automated liquid handling | Enable large-scale compound screening |

| Detection Methods | Reporter assays, binding assays, enzymatic activity measurements, fitness readouts | Measure compound-target interactions and phenotypic effects |

| Analytical Tools | Chemoinformatic software, network analysis algorithms, data integration platforms | Interpret complex chemical-genetic interaction datasets |

Research Resources and Applications in Chemical Genomics

Comparative Analysis Across Species

The integration of chemical genomics approaches across multiple species represents a powerful strategy for understanding fundamental biological processes and enhancing drug discovery. Cross-species comparisons leverage evolutionary diversity to distinguish conserved core processes from species-specific adaptations, providing valuable insights for antibiotic development where selective toxicity is paramount [8]. For example, essential genes identified through chemical-genetic interaction profiling in pathogenic bacteria like Acinetobacter baumannii can be compared with orthologs in model organisms or commensal bacteria to identify targets with the greatest therapeutic potential [8].

The application of chemical genomics in diverse organisms has revealed both conserved and specialized biological mechanisms. Sponges, which represent some of the earliest metazoans, have been found to possess sophisticated chemical defense systems and symbiotic relationships with diverse microorganisms [11]. Genomic studies of sponges through initiatives like the Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics Project have revealed that they are "the richest source of new potential pharmaceutical compounds in the world's oceans," with thousands of chemical compounds recovered from this animal phylum alone [11]. These natural products provide valuable chemical starting points for both forward and reverse chemical genomics approaches across multiple species.

Modern genomics services and technologies are increasingly facilitating cross-species chemical genomics. Next-generation sequencing platforms have dramatically reduced the cost and time required for genome sequencing, making comparative genomics more accessible [12] [11]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with multi-omics data enables prediction of gene function and chemical-target interactions across species boundaries [12]. Cloud computing platforms provide the scalable infrastructure needed to manage and analyze the massive datasets generated by cross-species chemical genomics studies [12].

Forward and reverse chemical genomics represent complementary paradigms in functional genomics and drug discovery, each with distinct strengths and applications. Forward chemical genomics excels at discovering novel biological mechanisms and identifying unexpected drug targets by starting with phenotypic observations, while reverse chemical genomics provides a more targeted approach for validating specific targets and understanding their biological functions [1]. The integration of both approaches, facilitated by advanced technologies such as CRISPR screening, high-throughput sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis, provides a powerful framework for elucidating gene function and identifying therapeutic opportunities across diverse species [10] [12] [8]. As chemical genomics continues to evolve, the complementary application of forward and reverse approaches will remain essential for advancing our understanding of biological systems and accelerating drug discovery.

Comparative genomics provides a powerful lens through which scientists can decipher the evolutionary history of life and uncover the genetic underpinnings of biological form and function. By comparing the complete genome sequences of different species, researchers can pinpoint regions of similarity and difference, identifying genes that are essential to life and those that grant each organism its unique characteristics [5] [13]. This approach has moved from a specialized field to a cornerstone of modern biological research, with profound implications for understanding human health and disease [14].

Foundations in Evolutionary Biology

At its core, comparative genomics is a direct test of evolutionary theory. The affinities between all living beings, famously represented by Darwin's "great tree," can now be examined at the most fundamental level—the DNA sequence [15].

The classic view of relatively stable genomes evolving through gradual, vertical inheritance has been supplemented by the more dynamic concept of "genomes in flux," where horizontal gene transfer and lineage-specific gene loss act as major evolutionary forces [15]. Genomic analyses consistently reveal that all eukaryotes share a common ancestor, and each surviving species possesses unique adaptations that have contributed to its evolutionary success [14]. By studying these adaptations, from disease resistance in bats to limb regeneration in salamanders, scientists can extrapolate findings to impact human health [14].

The phylogenetic distance between species determines the specific insights gained from comparison. Distantly related species help identify a core set of highly conserved genes vital to life, while closely related species, like humans and chimpanzees, help pinpoint the genetic differences that account for subtle variations in biology [13].

Key Applications in Biomedical Research

Comparative genomics has yielded dramatic results by exploring areas from human development and behavior to metabolism and disease susceptibility [5]. The table below summarizes several key applications impacting human health.

Table 1: Biomedical Applications of Comparative Genomics

| Application Area | Key Findings and Impacts | Example Organisms Studied |

|---|---|---|

| Zoonotic Disease & Pandemic Preparedness | Studies how pathogens adapt to new hosts; identifies key receptors (e.g., ACE2 for SARS-CoV-2) and reservoir species; aids in developing models for therapeutics and vaccines. [14] | Bats, mink, Syrian Golden Hamsters, birds [14] |

| Antimicrobial Therapeutics | Discovers novel Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) with unique mechanisms of action, helping combat antibiotic resistance. [14] | Frogs, scorpions [14] |

| Cancer Research | Identifies conserved genes involved in cancer; two-thirds of human cancer genes have counterparts in the fruit fly. [5] [13] | Fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) [5] [13] |

| Neurobiology & Speech | Reveals gene networks underlying complex traits like bird song, providing insights into human speech and language. [5] | Songbirds (across 50 species) [5] |

| Physiological Adaptations | Uncovers genetic bases of traits like hibernation, longevity, and cancer survival, offering new research avenues. [14] | Diverse eukaryotes [14] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A typical comparative genomics study involves a multi-stage process, from sample collection to biological interpretation. The workflow integrates laboratory techniques and computational analyses to translate raw genetic material into evolutionary and biomedical insights.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

1. Genomic Sequencing and Assembly The foundation of any comparative study is high-quality genome sequences. The Earth BioGenome Project (EBP), for example, aims to generate reference genomes for all eukaryotic life, with quality standards including contig N50 of 1 Mb and base-pair accuracy of 10⁻⁴ [16]. For a typical organism, high-molecular-weight DNA is extracted and sequenced using a combination of technologies:

- Long-Read Sequencing (PacBio or Oxford Nanopore): Generates reads thousands of base pairs long, crucial for resolving repetitive regions and producing contiguous assemblies.

- Short-Read Sequencing (Illumina): Provides highly accurate reads used for polishing and error-correcting the long-read assembly. The resulting sequences are assembled into chromosomes or scaffolds, and genes are annotated using a combination of ab initio prediction and homology-based methods [16].

2. Identifying Orthologs and Syntenic Regions To make valid comparisons, researchers must distinguish between orthologs (genes in different species that evolved from a common ancestral gene) and paralogs (genes related by duplication within a genome). A standard protocol involves:

- All-vs-All BLAST: Performing a sequence similarity search of all proteins from all species against each other.

- Clustering with Algorithms: Using tools like OrthoMCL or OrthoFinder to cluster sequences into orthologous groups based on sequence similarity scores.

- Synteny Analysis: Using tools like SynMap on the CoGe platform to generate syntenic dot-plots and identify conserved genomic blocks between species, which provides stronger evidence for orthology than sequence similarity alone [17] [13].

3. Analyzing Genetic Variants For population-level studies, the focus shifts to short genetic variants (<50 bp) like single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The workflow includes:

- Alignment: Mapping short sequencing reads from multiple individuals of a species to a reference genome using aligners like BWA.

- Variant Calling: Using tools such as GATK or SAMtools to identify positions where the sequenced individuals differ from the reference.

- Database Integration: Curating variants into databases like dbSNP and comparing their frequencies and predicted functional impacts across populations and species [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful comparative genomics research relies on a suite of reagents, databases, and computational tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Tool or Resource | Type | Primary Function | URL/Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCSC Genome Browser [17] | Web-based Tool | Interactive visualization and exploration of genome sequences and conservation tracks. | https://genome.ucsc.edu |

| VISTA [17] [13] | Web-based Suite | Comprehensive platform for comparative analysis of genomic sequences, including alignment and conservation plotting. | http://pipeline.lbl.gov |

| Circos [17] [19] | Standalone Software | Creates circular layouts to visualize genomic data and comparisons between multiple genomes. | http://circos.ca/ |

| cBio [17] | Web-based Portal | An open-access resource for interactive exploration of multidimensional cancer genomics datasets. | https://www.cbioportal.org/ |

| SynMap [17] | Web-based Tool | Generates syntenic dot-plot between two organisms and identifies syntenic regions. | Part of the CoGe platform |

| dbSNP [18] | Database | NCBI database of genetic variation, including single nucleotide polymorphisms. | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/ |

| Antimicrobial Peptide Database (APD) [14] | Database | Catalog of known antimicrobial peptides, many derived from eukaryotic organisms. | http://aps.unmc.edu/AP/ |

The relationships between these key resources and their role in the research workflow can be visualized as an integrated ecosystem.

The field is poised for transformative growth. Large-scale initiatives like the Earth BioGenome Project are transitioning from generating single reference genomes to building pangenomes—collections of all genome sequences within a species—to capture its full genetic diversity [16]. The integration of genomic data with detailed phenotypic information, powered by artificial intelligence (AI), promises to unlock deeper insights into the genetic basis of complex traits and diseases [16]. Projects like the NIH Comparative Genomics Resource (CGR) are addressing ongoing challenges in data quality, annotation, and interoperability to maximize the biomedical impact of eukaryotic research organisms [14].

In conclusion, comparing genomes across species is not merely a technical exercise; it is a fundamental approach to biological discovery. It allows researchers to read the evolutionary history written in DNA and apply those lessons to some of the most pressing challenges in human health, from infectious diseases and antibiotic resistance to cancer and genetic disorders. As the tools and datasets continue to expand, the evolutionary perspective offered by comparative genomics will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone of biomedical research.

This guide provides an objective comparison of the most prominent model organisms used in modern biological research, with a specific focus on applications in comparative chemical genomics. The following data and analysis assist researchers in selecting the appropriate model system for drug discovery and functional genomics studies, based on experimental needs, genomic conservation, and practical considerations.

Table 1: Genomic and Experimental Characteristics of Key Model Organisms

| Organism | Type | Genome Size (Haploid) | Generation Time | Genetic Tractability | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae (Budding Yeast) | Single-cell Eukaryote (Fungus) | ~12 Mbp (6,000 genes) [20] | ~90 minutes [20] | High (efficient homologous recombination, plasmid transformation) [20] | Ideal for fundamental cellular process studies (e.g., cell cycle, DNA damage response); cost-effective [20] [21] | Lacks complex organ systems; significant differences in signal transduction vs. mammals [21] |

| S. pombe (Fission Yeast) | Single-cell Eukaryote (Fungus) | Information from search results is insufficient | Information from search results is insufficient | Information from search results is insufficient | Key discoveries in cell cycle control [20] | Information from search results is insufficient |

| D. melanogaster (Fruit Fly) | Complex Multicellular Eukaryote | Information from search results is insufficient | Information from search results is insufficient | Information from search results is insufficient | Information from search results is insufficient | Phenotype data did not significantly improve disease gene identification over mouse data alone [22] |

| D. rerio (Zebrafish) | Complex Multicellular Vertebrate | Information from search results is insufficient | Information from search results is insufficient | Information from search results is insufficient | Information from search results is insufficient | Phenotype data did not significantly improve disease gene identification over mouse data alone [22] |

| M. musculus (Mouse) | Complex Mammalian Vertebrate | Information from search results is insufficient | Information from search results is insufficient | High (e.g., CRISPR, homologous recombination) | Highest predictive value for human disease genes; complex physiology and immunology [22] | Expensive and ethically stringent; longer generation times [22] |

Functional and Genomic Conservation

A core principle in comparative genomics is that fundamental biological processes are conserved across evolution. Research has demonstrated that approximately one-third of the yeast genome has a homologous counterpart in humans, and about 50% of genes essential in yeast can be functionally replaced by their human orthologs [20]. This conservation enables the use of simpler organisms to decipher gene function and disease mechanisms relevant to human health.

Table 2: Contribution to Human Disease Gene Discovery via Phenotypic Similarity

| Model Organism | Contribution to Disease Gene Identification | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse (M. musculus) | Primary Contributor | Mouse genotype-phenotype data provided the most important dataset for identifying human disease genes by semantic similarity and machine learning [22]. |

| Zebrafish (D. rerio) | Non-Significant Contributor | Data from zebrafish, fruit fly, and fission yeast did not improve the identification of human disease genes over that achieved using mouse data alone [22]. |

| Fruit Fly (D. melanogaster) | Non-Significant Contributor | Same as above [22]. |

| Fission Yeast (S. pombe) | Non-Significant Contributor | Same as above [22]. |

Experimental Protocols in Comparative Chemical Genomics

High-Throughput Drug Screening in Yeast

The yeast deletion collection, a set of approximately 4,800 viable haploid deletion mutants, each tagged with a unique DNA barcode, is a powerful tool for chemical genomics [20].

Protocol:

- Pooled Screening: Grow a pooled population of all deletion mutants in the presence of the bioactive compound of interest and in a control (DMSO) condition [20].

- DNA Extraction and Amplification: After several generations, extract genomic DNA from both cultures. Amplify the unique barcode sequences (UPTAG and DOWNTAG) via PCR using universal primers [20].

- Sequencing and Analysis: Deep-sequence the amplified barcodes. The relative abundance of each barcode in the drug condition compared to the control identifies genes whose deletion causes hypersensitivity or resistance, pointing to the drug's mechanism of action or cellular pathways it affects [20].

Comparative Genomics for Antibiotic Resistance Gene Identification

This protocol, applicable to bacterial models and relevant for antimicrobial research, identifies resistance genes in sequenced isolates [23].

Protocol:

- Sequence and Assemble: Perform Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) on bacterial isolates and assemble the reads into contigs using de novo assembly algorithms [23].

- Annotate Genes: Annotate the assembled genome to identify all coding sequences [23].

- Database Alignment: Align the contigs or annotated gene sequences against reference sequences in specialized antimicrobial resistance databases (e.g., CARD, ARG-ANNOT) [23].

- Identify Determinants: Identify and annotate resistance genes based on sequence homology and alignment quality (depth and coverage) [23].

Key Signaling Pathways and Workflows

DNA Damage Response in Yeast

The DNA damage response (DDR) pathway, highly conserved from yeast to humans, is a prime example of how model organisms elucidate fundamental biology. This pathway coordinates cell cycle arrest with DNA repair to maintain genomic integrity [20].

Phenotype-Based Disease Gene Discovery Workflow

This workflow illustrates the computational process of using model organism phenotypes to identify candidate human disease genes, a method where mouse data has proven most effective [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Deletion Collection | A genome-wide set of barcoded knockout mutants for high-throughput functional genomics and drug screening [20]. | ~4,800 haploid deletion strains in S288c background [20]. |

| Yeast Artificial Chromosomes (YACs) | Cloning vectors that allow for the insertion and stable propagation of very large DNA fragments (100 kb - 3000 kb) in yeast cells [21]. | Used for genome mapping and sequencing projects [21]. |

| Plasmids and Expression Vectors | For gene overexpression, heterologous protein expression, and targeted gene manipulation in various model systems [20] [21]. | Yeast episomal plasmids (YEps); CRISPR/Cas9 vectors [20] [24]. |

| Clustered Orthologous Groups (COG) Database | A database of ortholog groups from multiple prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes, used for functional annotation and evolutionary analysis [25]. | The 2024 update includes 2,296 representative prokaryotic species [25]. |

| Phenotype Ontologies | Standardized vocabularies (e.g., HPO, MPO) to describe phenotypes, enabling computational cross-species phenotype comparison [22]. | The uPheno ontology integrates phenotypes from human, mouse, zebrafish, fly, and yeast [22]. |

| Antimicrobial Resistance Databases | Curated collections of reference sequences for identifying antibiotic resistance genes from genomic data [23]. | Specialized databases (e.g., CARD) for detecting known and novel resistance variants [23]. |

The post-genomic era describes the period following the completion of the Human Genome Project (HGP) around 2000, characterized by a fundamental shift from gene-centered research to a more holistic understanding of genome function and biological complexity [26]. This transition has moved beyond simply cataloging genes to exploring how they interact with environmental factors and how their functions are regulated across different species [27]. The completion of the HGP provided the essential reference map—the "language" of life—while the post-genomic era focuses on interpreting this language to understand biological systems [28].

This era is marked by the recognition that genetic information alone is insufficient to explain biological complexity, driving the emergence of fields like functional genomics, proteomics, and chemogenomics [26] [29]. Where the genomic era focused on sequencing and mapping, the post-genomic era investigates the dynamic interactions between genes, proteins, and environmental factors across diverse organisms [27]. The dramatic reduction in sequencing costs—from $2.7 billion for the first genome to just a few hundred dollars today—has democratized genomic technologies, making them accessible tools for broader biological research rather than ends in themselves [30] [27].

Major Technological and Conceptual Shifts

From Sequencing to Functional Analysis

The post-genomic era has witnessed a fundamental transformation in research priorities and capabilities, characterized by several key developments:

- Shift from Structure to Function: Research focus has transitioned from determining gene sequences to understanding gene function, regulation, and interaction networks [27]

- Rise of Multi-Omics Integration: Approaches now combine genomics with proteomics, transcriptomics, and epigenomics to obtain a systems-level view of biology [31]

- Computational and AI Revolution: Advanced computational tools and artificial intelligence are required to analyze complex datasets and identify patterns beyond human analytical capacity [31]

The Conceptual Evolution: Challenging Genetic Determinism

Post-genomic research has fundamentally challenged the simplified "gene-centric" view of biology [28]. Several key discoveries have driven this conceptual transformation:

- Non-Coding DNA Revolution: Only 1-2% of the human genome actually codes for proteins, with the majority consisting of regulatory regions and non-coding RNA genes that exceed protein-coding genes in number [28]

- Regulatory Complexity: Gene regulation in humans involves multilayer processes far more complex than simple switches, depending on cellular context and higher-level organizational structures [28]

- Omnigenic Model: This emerging framework suggests that many traits are influenced by countless variants scattered across the genome rather than clustered within specific genes of large effect [27]

Table 1: Key Transitions from Genomic to Post-Genomic Science

| Dimension | Genomic Era | Post-Genomic Era |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Gene sequencing and mapping | Gene function and regulation |

| Central Dogma | "Gene blueprint" determinism | Complex gene-environment interactions |

| Key Molecules | DNA and protein-coding genes | Non-coding RNAs, proteins, metabolites |

| Technology Emphasis | Sequencing platforms | Multi-omics integration, computational analysis |

| Research Approach | Single-gene focus | Systems biology, network analysis |

Comparative Chemical Genomics: Principles and Applications

Defining Chemical Genomics

Chemical genomics (also called chemogenomics) represents a powerful post-genomic approach that systematically screens targeted chemical libraries of small molecules against families of drug targets to identify novel drugs and drug targets [1]. This methodology bridges target and drug discovery by using active compounds as probes to characterize proteome functions [1]. The interaction between a small compound and a protein induces a phenotype, allowing researchers to associate proteins with molecular events [1].

Two complementary experimental approaches define chemical genomics research:

- Forward Chemogenomics: Begins with a particular phenotype and identifies small compounds that interact with this function, then determines the protein responsible [1]

- Reverse Chemogenomics: Identifies compounds that perturb specific enzyme functions in vitro, then analyzes induced phenotypes in cells or whole organisms [1]

Applications in Drug Discovery and Target Identification

Chemical genomics has enabled several significant applications in biomedical research:

- Mode of Action Determination: Successfully identified mechanisms of action for traditional medicines by predicting ligand targets relevant to known phenotypes [1]

- Novel Antibacterial Targets: Mapped existing ligand libraries to entire enzyme families (e.g., mur ligases) to identify new targets for known ligands [1]

- Pathway Elucidation: Discovered previously unknown enzymes in biosynthetic pathways (e.g., diphthamide synthesis) using cofitness data from deletion strains [1]

Cross-Species Comparative Genomics: Methods and Impact

Principles of Comparative Genomics

Comparative genomics involves comparing genetic information within and across organisms to understand gene evolution, structure, and function [14]. This approach has been revolutionized by advances in sequencing technology and assembly algorithms that enable large-scale genome comparisons [14]. The fundamental principle is that evolutionary relationships allow discoveries in model organisms to illuminate biological processes in humans, taking advantage of natural evolutionary experiments [32].

Comparative genomics leverages the fact that all eukaryotes share a common ancestor, with each species representing survivors adapted to specific niches through unique adaptations—hibernation, disease tolerance, immune response, cancer survival, longevity, regeneration, and specialized sensory systems [14]. By comparing genomes, researchers can understand these adaptations and extrapolate findings to impact human health [14].

Key Applications in Human Health

Table 2: Applications of Comparative Genomics in Biomedical Research

| Application Area | Research Approach | Health Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Zoonotic Disease Research | Study pathogen adaptation across species and spillover events [14] | Pandemic preparedness and intervention strategies |

| Antimicrobial Therapeutics | Discover novel antimicrobial peptides in diverse eukaryotes [14] | Addressing antibiotic resistance crisis |

| Drug Target Identification | Leverage evolutionary relationships to validate targets [32] [1] | More efficient drug development pipelines |

| Toxicology & Risk Assessment | Characterize interspecies differences in chemical response [32] | Improved safety evaluation of environmental chemicals |

Experimental Framework for Cross-Species Comparative Studies

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for comparative genomics studies that investigate biological mechanisms across multiple species:

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

The post-genomic research landscape requires specialized reagents, databases, and computational tools to enable comparative studies across species. The following table summarizes key resources mentioned across the search results:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | NIH Comparative Genomics Resource (CGR) [14] | Access to curated eukaryotic genomic data |

| Chemical Libraries | Targeted chemical libraries [1] | Screening against drug target families |

| Antimicrobial Peptide Databases | APD, CAMPR4, ADAM, DBAASP, DRAMP, LAMP2 [14] | Discovery of novel therapeutic peptides |

| Model Organisms | Syrian Golden Hamsters, Bats, Frogs [14] | Studying disease resistance mechanisms |

| Bioinformatics Tools | NCBI genomics toolkit [14] | Data analysis and cross-species comparisons |

Detailed Experimental Approaches

Forward Chemical Genomics Protocol

Forward chemical genomics aims to identify compounds that induce a specific phenotype, then determine their protein targets [1]. The following workflow outlines a standardized approach for forward chemical genomics screening:

Detailed Methodology:

- Phenotypic Assay Development: Design cell-based or whole-organism assays that measure a biologically relevant phenotype (e.g., cancer cell growth arrest, pathogen killing) [1]

- Screening Collection Curation: Assay diverse compound libraries, prioritizing structures with known activity against target families and favorable physicochemical properties [1]

- High-Throughput Screening: Implement automated screening platforms with appropriate controls and quality metrics [1]

- Target Identification: Employ one or more deconvolution strategies:

- Affinity purification using compound-conjugated resins

- Genetic approaches including resistance generation and genome-wide sequencing

- Proteomic methods such as thermal stability profiling [1]

- Mechanistic Validation: Confirm biological relevance through genetic manipulation (CRISPR, RNAi) and functional studies [1]

Cross-Species Genomic Comparison Protocol

Comparative genomics approaches systematically explore evolutionary relationships to understand gene function and disease mechanisms [14]. The following protocol outlines a standardized methodology:

Experimental Workflow:

- Species Selection: Choose evolutionarily diverse species based on research question—closely related species for precise mechanistic insights, distantly related for fundamental adaptations [14]

- Data Acquisition and Quality Control:

- Obtain high-quality genome assemblies from repositories (NCBI, Ensembl)

- Apply uniform annotation pipelines across all species

- Verify assembly metrics (N50, completeness) [14]

- Comparative Analysis:

- Identify orthologous genes using sequence similarity and synteny

- Calculate evolutionary rates (dN/dS ratios)

- Detect conserved non-coding elements [14]

- Functional Validation:

Impact on Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

Transforming Drug Discovery Paradigms

The post-genomic era has fundamentally reshaped drug discovery through several key developments:

- Target Identification: Comparative genomics enables systematic identification of emerging drug targets by studying biological adaptations across species [14]

- Mechanism of Action Elucidation: Chemical genomics approaches rapidly determine how compounds achieve their therapeutic effects, accelerating optimization [1]

- Safety Profiling: Cross-species comparisons help identify potential toxicities by understanding interspecies differences in drug metabolism and target conservation [32]

Quantitative Advances in Therapeutic Discovery

The impact of post-genomic approaches is reflected in quantitative improvements in drug discovery efficiency:

- Antimicrobial Peptide Discovery: More than 3,000 AMPs have been identified, with approximately 30% first discovered in frogs, each species possessing a unique repertoire of 10-20 peptides [14]

- Target Validation Success: Comparative approaches improve target validation by leveraging evolutionary conservation and natural variation [14]

- Chemical Probe Development: Targeted chemical libraries systematically cover drug target families, increasing screening efficiency [1]

Emerging Trends and Technologies

The post-genomic era continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping future research:

- Integrated Multi-Omics: Combining genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data from the same samples provides comprehensive biological insights [31]

- Spatial Biology: Advanced sequencing technologies enable direct analysis of cells within their native tissue context, preserving spatial relationships [31]

- AI-Driven Discovery: Machine learning algorithms analyze complex datasets to identify patterns and relationships beyond conventional analysis [31]

- Single-Cell Technologies: Resolving biological complexity at individual cell level reveals previously masked heterogeneity [31]

The post-genomic era represents a fundamental transformation in biological research, moving beyond the static DNA sequence to explore dynamic interactions between genes, proteins, and environment across diverse species [26] [27]. The integration of comparative genomics with chemical genomics creates powerful frameworks for understanding biological complexity and developing novel therapeutics [1] [14].

While the promise of immediate clinical applications from the Human Genome Project may have been overstated, the post-genomic era has delivered something potentially more valuable: a more nuanced and accurate understanding of biological complexity that is gradually transforming medicine [28]. The continued development of tools, databases, and experimental approaches ensures that comparative studies across species will remain essential for translating genomic information into improved human health [14].

Advanced Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Cross-Species Screening

High-Throughput Screening Platforms and Automation Technologies

High-throughput screening (HTS) platforms represent a foundational technology in modern drug discovery and comparative chemical genomics. These automated systems enable researchers to rapidly test thousands to millions of chemical or genetic perturbations against biological targets, dramatically accelerating the pace of scientific discovery. Within comparative genomics research—which examines genetic information across species to understand evolution, gene function, and disease mechanisms—HTS platforms provide the experimental throughput necessary to systematically explore biological relationships and evaluate emerging model organisms across the tree of life [33].

The global HTS market reflects this critical importance, estimated at USD 26.12 billion in 2025 and projected to reach USD 53.21 billion by 2032, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.7% [34]. This growth is propelled by increasing adoption across pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and chemical industries, driven by the persistent need for faster drug discovery and development processes. Current market trends indicate a strong push toward full automation and the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) with HTS platforms, improving both efficiency and accuracy while reducing costs and time-to-market for new therapeutics [34].

Comparative Analysis of HTS Platform Technologies

High-throughput screening technologies can be broadly categorized by their technological approach, detection method, and degree of automation. The following analysis compares the performance characteristics of major HTS platform types relevant to comparative genomics research, which requires robust, reproducible, and information-rich data across diverse biological systems.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major HTS Technology Platforms

| Technology Type | Maximum Throughput | Key Strengths | Primary Applications in Comparative Genomics | Data Quality Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assays | ~100,000 compounds/day | Physiological relevance, functional readouts, pathway analysis | Toxicity screening, functional genomics, receptor activation studies | Higher biological variability, requires cell culture expertise [34] |

| Biochemical Assays | ~1,000,000 compounds/day | High sensitivity, minimal variability, target-specific | Enzyme inhibition, protein-protein interaction studies | May lack cellular context, potential for false positives [34] |

| CRISPR-Based Screening | Genome-wide (varies) | Precise genetic manipulation, identifies gene function | Functional genomics, gene-disease association mapping | Off-target effects, complex data interpretation [34] |

| Label-Free Technologies | ~50,000 compounds/day | Non-invasive, real-time kinetics, no artificial labels | Cell adhesion, morphology studies, toxicology | Lower throughput, specialized equipment required [35] |

| Quantitative HTS (qHTS) | 700,000+ data points | Multi-concentration testing, reduced false positives | Large-scale chemical profiling, Tox21 program | Complex data analysis, requires robust statistical approaches [36] |

Cell-based assays currently dominate the HTS technology landscape, projected to capture 33.4% of the market share in 2025 [34]. Their prominence in comparative genomics stems from their ability to more accurately replicate complex biological systems compared to traditional biochemical methods, making them indispensable for both drug discovery and disease research. These assays provide invaluable insights into cellular processes, drug actions, and toxicity profiles, offering higher predictive value for clinical outcomes. The growing emphasis on functional genomics and phenotypic screening propels the use of cell-based methodologies that reflect complex cellular responses, such as proliferation, apoptosis, and signaling pathways [34].

Emerging Platform Capabilities

Recent technological advances have significantly enhanced HTS platform capabilities. For instance, in December 2024, Beckman Coulter Life Sciences launched the Cydem VT Automated Clone Screening System, a high-throughput microbioreactor platform that reduces manual steps in cell line development by up to 90% and accelerates monoclonal antibody screening [34]. Similarly, the September 2025 introduction of INDIGO Biosciences' full Melanocortin Receptor Reporter Assay family provides researchers with a comprehensive toolkit to study receptor biology and advance drug discovery for metabolic, inflammatory, adrenal, and pigmentation-related conditions [34].

The integration of artificial intelligence is rapidly reshaping the global HTS landscape by enhancing efficiency, lowering costs, and driving automation in drug discovery and molecular research. AI enables predictive analytics and advanced pattern recognition, allowing researchers to analyze massive datasets generated from HTS platforms with unprecedented speed and accuracy, reducing the time needed to identify potential drug candidates [34]. Companies like Schrödinger, Insilico Medicine, and Thermo Fisher Scientific are actively leveraging AI-driven screening to optimize compound libraries, predict molecular interactions, and streamline assay design [34].

Experimental Protocols for HTS in Cross-Species Studies

Implementing robust experimental protocols is essential for generating reliable, reproducible data in comparative genomics applications of HTS. The following section details standardized methodologies for key experiment types, with particular attention to cross-species considerations.

Quantitative HTS (qHTS) Protocol for Multi-Species Profiling

Quantitative HTS represents a significant advancement over traditional single-concentration screening by testing compounds across multiple concentrations, generating concentration-response data simultaneously for thousands of different compounds and mixtures [36]. This approach is particularly valuable in comparative genomics for identifying species-specific compound sensitivities.

Protocol Details:

- Plate Format: 1536-well plates (≤10 μl working volume per well)

- Concentration Range: Typically 0.5 nM to 50 μM (15 concentrations, serial dilutions)

- Controls: Vehicle controls (0.5% DMSO), positive/negative controls on every plate

- Incubation: 24-72 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂ (species-dependent)

- Detection: High-sensitivity detectors (luminescence, fluorescence, or absorbance)

- Replicates: Minimum n=3 for each concentration (technical replicates)

Species-Specific Considerations: Cell lines from multiple species require careful normalization to account for differences in basal metabolic activity, growth rates, and protein expression levels. For cross-species receptor studies (e.g., melanocortin receptors), implement species-specific positive controls to establish appropriate dynamic ranges for each assay system [34].

Data Analysis Method: Concentration-response curves are typically fitted using the four-parameter Hill equation model:

[Ri = E0 + \frac{(E∞ - E0)}{1 + \exp{-h[\log Ci - \log AC{50}]}}]

Where (Ri) is the measured response at concentration (Ci), (E0) is the baseline response, (E∞) is the maximal response, (AC_{50}) is the concentration for half-maximal response, and (h) is the Hill slope parameter [36].

Critical Implementation Note: Parameter estimates from the Hill equation can be highly variable when the tested concentration range fails to include at least one of the two asymptotes, particularly for partial agonists or compounds with low efficacy [36]. Optimal study designs should ensure concentration ranges adequately capture both baseline and maximal response levels across all species tested.

CRISPR-Based Screening Protocol for Functional Genomics

CRISPR-based high-throughput screening enables genome-wide studies of gene function across model organisms, facilitating comparative analysis of conserved pathways and species-specific genetic dependencies.

Protocol Details:

- Library Design: Genome-wide sgRNA libraries (3-10 sgRNAs per gene)

- Delivery Method: Lentiviral transduction at low MOI (0.3-0.5) to ensure single integration

- Selection: Puromycin selection (2-5 μg/ml, 48-72 hours)

- Screening Timeline: 14-21 days population doubling with sampling at multiple timepoints

- Analysis: Next-generation sequencing of sgRNA representation

Recent Innovation: The CIBER platform, developed at the University of Tokyo in November 2024, is a CRISPR-based high-throughput screening system that labels small extracellular vesicles with RNA barcodes. This platform enables genome-wide studies of vesicle release regulators in just weeks, offering an efficient way to analyze cell-to-cell communication and advancing research into diseases such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and other conditions linked to extracellular vesicle biology [34].

Automated Toxicity Screening Protocol for Comparative Toxicology

The U.S. FDA's April 2025 roadmap to reduce animal testing in preclinical safety studies has accelerated the adoption of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), including advanced in-vitro assays using HTS platforms [34]. This protocol aligns with those initiatives for cross-species toxicity assessment.

Protocol Details:

- Cell Models: Primary cells or iPSC-derived hepatocytes/cardiomyocytes from multiple species

- Endpoint Multiplexing: Viability (ATP content), apoptosis (caspase activation), oxidative stress (GSH depletion)

- Exposure Time: 24-72 hours with intermediate timepoint measurements

- Compound Logistics: Automated liquid handling with integrated compound management

- QC Criteria: Z'-factor >0.5, coefficient of variation <20% for controls

Data Integration for Comparative Genomics: Results from multi-species toxicity screening can be integrated with genomic data to identify conserved toxicity pathways versus species-specific metabolic activation/detoxification systems, providing critical insights for extrapolating toxicological findings across species.

Visualization of HTS Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The integration of HTS within comparative genomics research involves complex experimental workflows and data analysis pipelines. The following diagrams visualize these processes to enhance understanding of the logical relationships and experimental sequences.

Quantitative HTS Experimental Workflow

Diagram Title: Quantitative HTS Experimental Workflow

Cross-Species Data Integration Pathway

Diagram Title: Cross-Species Data Integration Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions for HTS in Comparative Genomics

Successful implementation of HTS platforms in comparative genomics requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for automated systems and cross-species applications. The following table details essential research reagent solutions and their specific functions in HTS workflows.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTS in Comparative Genomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in HTS Workflow | Cross-Species Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Reagents | Species-adapted media, reduced-serum formulations, primary cell systems | Maintain physiological relevance during automated liquid handling | Optimize for species-specific requirements (temperature, CO₂, nutrients) |

| Detection Reagents | Luminescent ATP assays, fluorescent viability dyes, FRET-based protease substrates | Enable high-sensitivity readouts in miniaturized formats | Validate across species for conserved enzyme activities (e.g., luciferase) |

| CRISPR Components | sgRNA libraries, Cas9 variants, barcoded viral vectors | Enable genome-wide functional screening | Design species-specific sgRNAs accounting for genomic sequence differences |

| Specialized Assay Kits | Melanocortin receptor reporter assays, GPCR activation panels, cytochrome P450 inhibition kits | Provide standardized protocols for specific target classes | Verify receptor homology and functional conservation across species |

| Automation-Consumables | Low-evaporation microplates, non-stick reagent reservoirs, conductive tips | Ensure reproducibility and minimize waste in automated systems | Standardize across all species tested to eliminate platform-based variability |

Recent innovations in research reagents include the September 2025 introduction by INDIGO Biosciences of its full Melanocortin Receptor Reporter Assay family covering MC1R, MC2R, MC3R, MC4R, and MC5R [34]. This suite provides researchers with a comprehensive toolkit to study receptor biology and advance drug discovery for metabolic, inflammatory, adrenal, and pigmentation-related conditions across multiple species.

High-throughput screening platforms continue to evolve toward greater automation, miniaturization, and biological relevance, making them increasingly valuable for comparative genomics research. The integration of AI and machine learning with HTS data analysis is particularly promising for identifying complex patterns across species and predicting cross-species compound activities [34]. These advancements are crucial for addressing fundamental questions in comparative genomics, including the identification of conserved therapeutic targets and understanding species-specific responses to chemical perturbations.

The growing emphasis on human-relevant models, accelerated by regulatory shifts like the FDA's 2025 roadmap for reducing animal testing, is driving innovation in cell-based HTS technologies [34]. Combined with emerging capabilities in CRISPR-based screening and quantitative HTS approaches, these platforms will continue to transform our ability to extract meaningful biological insights from cross-species comparisons, ultimately accelerating the development of new therapeutics and enhancing our understanding of evolutionary biology.

Diversity-Based vs. Design-Based Compound Library Strategies

In the field of comparative chemical genomics, the strategic selection and design of compound libraries directly determines the efficiency and success of research. The fundamental challenge lies in effectively navigating the vast theoretical chemical space, estimated to exceed 10^60 drug-like molecules, to identify compounds that modulate biological targets across species [37]. Two dominant paradigms have emerged for this task: diversity-based approaches, which aim for broad coverage of chemical space, and design-based approaches, which focus on specific regions with higher probability of bioactivity. The choice between these strategies impacts not only screening outcomes but also resource allocation, with DNA-encoded library technology now enabling screens of billions of compounds in days instead of decades [38]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies to inform selection for chemical genomics projects.

Core Strategic Differences

Diversity-Based Strategies operate on the similar property principle, which states that structurally similar compounds are likely to have similar properties [39]. The primary goal is to maximize coverage of structural space while minimizing redundancy. This approach is particularly valuable when little is known about the target, such as with novel or poorly characterized genomic targets across species. Diversity analysis often emphasizes scaffold diversity, focusing on common core structures that characterize groups of molecules, as increasing scaffold coverage may identify novel chemotypes with unique bioactivity profiles [39].

Design-Based Strategies encompass more targeted approaches, including focused screening and combinatorial library design. Focused screening involves selecting compound subsets based on existing structure-activity relationships derived from known active compounds or protein target sites [39]. Modern design-based strategies have evolved to create libraries optimized for multiple properties simultaneously, including drug-likeness, ADMET properties, and targeted diversity to avoid multiple hits from the same chemotype [39]. These approaches require prior structural or functional knowledge of the target.

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of Library Design Approaches

| Feature | Diversity-Based Approach | Design-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Maximize chemical space coverage | Optimize for specific target or properties |

| Knowledge Requirement | Minimal target knowledge needed | Requires existing structure-activity data |

| Typical Context | Novel target exploration | Target-directed optimization |

| Screening Methodology | Sequential screening strategies | Focused screening campaigns |

| Chemical Space Coverage | Broad but shallow | Narrow but deep |

| Scaffold Emphasis | Scaffold hopping for novelty | Scaffold optimization for potency |

Quantitative Comparison of Performance Metrics

Hit Rate Efficiency

Studies have demonstrated conflicting outcomes when comparing diversity-based selection with random sampling. A simulation at Pfizer found that rationally designed subsets (including diversity-based selections) provided higher hit rates than random subsets in high-throughput screening [39]. However, contrasting results were found by other researchers, highlighting that outcomes are context-dependent. The efficiency of library size also demonstrates nonlinear relationships, with one study showing that approximately 2,000 fragments (less than 1% of available compounds) can attain the same level of true diversity as all 227,787 commercially available fragments [40].

Scaffold Diversity Analysis