Comparative Chemical Genomics: A Systematic Framework for Mechanism of Action Discovery in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of comparative chemical genomics, an integrative approach that combines large-scale genetic perturbations with chemical screening to elucidate drug mechanisms of action (MoA).

Comparative Chemical Genomics: A Systematic Framework for Mechanism of Action Discovery in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of comparative chemical genomics, an integrative approach that combines large-scale genetic perturbations with chemical screening to elucidate drug mechanisms of action (MoA). Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of systematically assessing gene-drug interactions. The content covers key methodological approaches, including forward and reverse chemogenomics, CRISPRi-based screens, and computational analyses. It also addresses common challenges in target identification and validation, offering troubleshooting strategies and optimization techniques. By synthesizing foundational concepts with practical applications and validation frameworks, this resource serves as a guide for leveraging comparative chemical genomics to accelerate therapeutic discovery, understand drug resistance, and identify novel therapeutic targets.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Concepts and Evolutionary Context of Chemical Genomics

Chemical genomics and chemical genetics represent complementary research paradigms that use small molecules as probes to modulate and understand biological systems. Framed within comparative chemical genomics for mechanism of action (MoA) discovery, these approaches provide a powerful framework for elucidating gene function and identifying therapeutic targets. Chemical genetics specifically refers to the use of biologically active small molecules (chemical probes) to investigate the functions of gene products through modulation of protein activity [1]. This approach mirrors classical genetics but uses small molecules instead of mutations to perturb protein function, allowing for rapid, conditional, and reversible alteration of biological processes [1] [2].

Chemical genomics encompasses a broader scope, describing large-scale in vivo approaches used in drug discovery, including chemical genetics but also extending to comprehensive screening of compound libraries for bioactivity against specific cellular targets or phenotypes [3]. The fundamental premise underlying both fields is the systematic exploration of the intersection between small molecules and biological systems, with the ultimate goal of identifying novel drugs and drug targets [4].

Terminological Distinctions and Operational Definitions

Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions

Although often used interchangeably in literature, chemical genetics and chemical genomics operate at different scales with distinct primary objectives:

Chemical Genetics: An approach that uses small molecules as molecular probes to study protein functions in cells or whole organisms [1]. It focuses on measuring the cellular outcome of combining genetic and chemical perturbations, systematically assessing how genetic variation influences drug activity [3]. The approach can be further divided into forward chemical genetics (phenotype-based screening) and reverse chemical genetics (target-based screening) [4].

Chemical Genomics: A broader umbrella term describing large-scale in vivo approaches in drug discovery, including not only chemical genetics but also comprehensive screening of compound libraries for bioactivity against specific cellular targets or phenotypes [3]. It aims to identify one or more specific ligands for every protein in a cell, tissue, or organism [2].

Table 1: Key Distinctions Between Chemical Genetics and Chemical Genomics

| Aspect | Chemical Genetics | Chemical Genomics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Studying protein function using small molecules [1] | Systematic screening of chemical libraries against target families [4] |

| Scale | Individual gene-protein systems | Genome-wide/proteome-wide scope |

| Screening Approach | Phenotypic or target-based | High-throughput parallel screening |

| Outcome | Biological insight into specific processes | Identification of novel drugs and drug targets |

| Genetic Integration | Measures drug effects across genetic variants [3] | Maps compound-target interactions systematically |

Experimental Paradigms: Forward and Reverse Approaches

Both chemical genetics and chemical genomics employ two principal experimental strategies:

Forward Chemical Genetics: Begins with screening small molecule libraries against cells or whole organisms to identify compounds that induce a specific phenotype of interest, followed by identification of the cellular targets responsible for the observed phenotype [4]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying novel signaling nodes and unraveling redundant networks that might be difficult to dissect using traditional genetic approaches [1].

Reverse Chemical Genetics: Starts with a specific protein target of interest, screening for small molecules that modulate its activity in in vitro assays, followed by testing these compounds in cellular or organismal systems to characterize the resulting phenotype [4]. This approach has been enhanced by parallel screening capabilities and the ability to perform lead optimization across multiple targets within a protein family.

Core Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Genetic Perturbation Libraries and Screening Platforms

Modern chemical genetics relies on systematically engineered genetic perturbation libraries that enable genome-wide functional screening:

Table 2: Genetic Library Platforms for Chemical Genetic Screens

| Library Type | Organism | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi knockdown | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Titratable knockdown of essential and non-essential genes [5] | Enables hypomorphic silencing; surveys essential genes |

| Heterozygous deletion (HIP) | Yeast | Haploinsufficiency profiling [3] | Identifies drug targets by reduced gene dosage |

| Overexpression libraries | Bacteria, human cells | Target identification [3] | Increased gene dosage confers resistance |

| Pooled mutant libraries | Various microbes | Fitness profiling under drug treatment [3] | Barcoded mutants enable parallel fitness assessment |

| Arrayed libraries | Various organisms | Macroscopic phenotypic screening [3] | Enables assessment of developmental phenotypes |

Protocol: Genome-Wide CRISPRi Chemical Genetic Screen

The following detailed protocol outlines a comprehensive chemical genetic screening approach for identifying genetic determinants of drug potency:

Library Construction: Develop a genome-scale CRISPRi library enabling titratable knockdown for nearly all genes, including protein-coding genes and non-coding RNAs. For Mycobacterium tuberculosis, this includes approximately 90,000 sgRNAs targeting both essential and non-essential genes [5].

Library Transformation: Transform the CRISPRi library into the target organism via electroporation, ensuring adequate coverage (typically >500x representation for each sgRNA) to maintain library diversity throughout the screening process.

Drug Treatment Conditions: Culture the library in biological triplicate under three descending doses of partially inhibitory drug concentrations (typically 0.25x, 0.5x, and 1x MIC) alongside an untreated control [5]. Use a minimum of 50 million cells per condition to maintain library complexity.

Outgrowth and Harvest: Grow cultures for multiple generations (typically 5-10 population doublings) to allow fitness differences to manifest. Harvest genomic DNA from both treated and untreated cultures at mid-log phase.

Sequencing Library Preparation: Amplify integrated sgRNA sequences using PCR with barcoded primers to enable multiplexed sequencing. Use a minimum of 5 million reads per sample to ensure quantitative detection of sgRNA abundance.

Fitness Quantification: Sequence amplified sgRNA pools on a high-throughput platform (Illumina). Calculate normalized read counts for each sgRNA across conditions and use statistical algorithms (MAGeCK) to identify genes whose knockdown significantly alters fitness during drug treatment [5].

Hit Validation: Confirm screening hits by constructing individual hypomorphic strains for top candidate genes and quantitatively measuring drug susceptibility changes through IC50 determination assays.

Data Analysis and Hit Identification

Chemical genetic screening data analysis involves several computational steps:

Read Alignment and Counting: Map sequencing reads to the reference sgRNA library using alignment tools such as Bowtie or BWA.

Fitness Score Calculation: Calculate normalized fitness scores for each gene under drug treatment compared to untreated controls using robust statistical methods that account for variations in sgRNA efficacy.

Gene-Drug Interaction Identification: Apply specialized algorithms (MAGeCK, PinAPL-Py) to identify significant chemical-genetic interactions, distinguishing between sensitizing interactions (where gene knockdown increases drug efficacy) and suppressing interactions (where knockdown decreases drug efficacy) [5].

Signature-Based MoA Prediction: Compare drug sensitivity profiles across the entire genome-wide dataset to identify compounds with similar chemical-genetic signatures, suggesting shared mechanisms of action or resistance [3].

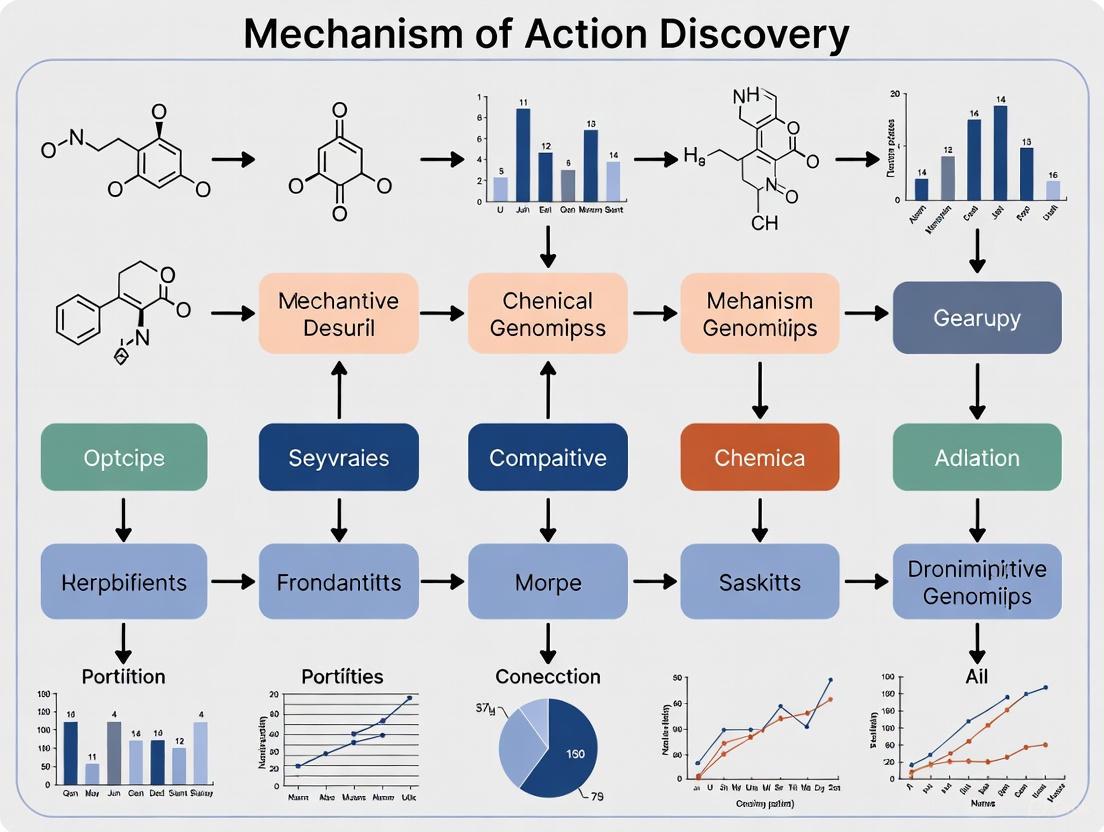

Diagram 1: Chemical genetics screening workflow.

Applications in Mechanism of Action Discovery

Target Identification and Validation

Chemical genetics provides powerful approaches for mapping drug targets through two principal strategies:

Modulation of Essential Gene Dosage: Utilizing libraries in which levels of essential genes can be modulated through knockdown (CRISPRi) or overexpression. When a drug target gene is knocked down, cells typically show increased sensitivity to the drug, as less drug is required to titrate the remaining cellular target. Conversely, overexpression of the target gene often confers resistance [3]. For example, CRISPRi knockdown libraries of essential genes in bacteria have successfully identified drug targets by demonstrating hypersensitization when target genes are silenced [3].

Signature-Based Target Prediction: Comparing comprehensive drug sensitivity signatures across genome-wide deletion libraries. Drugs with similar chemical-genetic interaction profiles likely share cellular targets and/or cytotoxicity mechanisms [3]. This "guilt-by-association" approach becomes increasingly powerful as more compounds are profiled, enabling the identification of repetitive chemogenomic signatures reflective of general drug mechanisms of action.

Dissecting Drug Resistance Mechanisms

Chemical genetic approaches reveal comprehensive insights into intrinsic drug resistance mechanisms:

Mapping Resistance Pathways: Chemical genetic profiling can identify up to 12% of the genome as conferring multi-drug resistance in yeast, while dozens of genes show similar pleiotropic roles in Escherichia coli [3]. These findings suggest fundamental differences in drug resistance architecture between prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Identifying Cryptic Resistance Elements: Comparative analysis of deletion and overexpression libraries reveals that many drug transporters and efflux pumps are cryptically encoded in bacterial genomes—they possess the capacity to confer resistance but are not optimally expressed under standard laboratory conditions [3]. This finding highlights the extensive potential for intrinsic antibiotic resistance in microbial populations.

Predicting Cross-Resistance Patterns: By measuring the contribution of every non-essential gene to resistance across multiple drugs, chemical genetics can comprehensively map cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity relationships, providing strategies to mitigate or even revert drug resistance [3].

Diagram 2: Drug resistance mechanism analysis.

Case Study: Mycobacterium tuberculosis Antibiotic Potency

A comprehensive CRISPRi chemical genetics study in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) exemplifies the power of this approach for mechanism of action discovery:

Platform Development: Researchers developed a CRISPRi platform enabling titratable knockdown of nearly all Mtb genes (essential and non-essential), performing 90 separate screens across nine drugs with concentrations spanning the predicted MIC [5].

Target Identification: Screens successfully recovered expected drug targets including direct targets (e.g., RNA polymerase for rifampicin) and genes encoding targets of known synergistic drug combinations [5].

Pathway Discovery: Analysis revealed correlated chemical-genetic signatures for rifampicin, vancomycin, and bedaquiline, with the essential mycolic acid-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan (mAGP) complex identified as a common sensitizing hit [5]. This finding validated the mAGP complex as a selective permeability barrier mediating intrinsic resistance specifically for these compounds.

Novel Resistance Mechanisms: The study identified the mtrAB two-component system as a previously underappreciated mediator of intrinsic drug resistance, with knockdown dramatically increasing envelope permeability and drug susceptibility [5].

Therapeutic Repurposing Opportunity: Analysis revealed that the intrinsic resistance factor whiB7 was inactivated in an entire Mtb sublineage endemic to Southeast Asia, suggesting the potential to repurpose the macrolide antibiotic clarithromycin for treating tuberculosis in this specific population [5].

Advanced Chemical Genetic Technologies

The Bump-and-Hole Approach for Enhanced Specificity

A significant challenge in chemical genetics is achieving sufficient specificity when targeting individual members of protein families with high sequence and structural conservation. The "bump-and-hole" approach addresses this limitation by engineering orthogonal enzyme-ligand pairs through complementary manipulation of the steric component of protein-ligand interactions:

Protein Engineering: A single point mutation is introduced into the target protein's active site to create a small cavity ("hole") without disrupting normal catalytic function.

Ligand Engineering: Existing broad-specificity inhibitors are chemically modified with a steric "bump" that prevents binding to wild-type enzymes but enables specific interaction with the engineered "hole"-containing protein.

Application: This approach has been successfully applied to protein kinases, enabling specific inhibition of individual kinase family members without affecting related enzymes [6]. The methodology is now being expanded to diverse protein classes including epigenetic readers, writers, and erasers [1].

Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs)

PROTAC compounds represent an advanced chemical genetic strategy that uses heterobifunctional molecules to recruit target proteins to E3 ubiquitin ligases, leading to their ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome. Compared to standard domain inhibitors, PROTACs demonstrate significantly enhanced efficacy and potential for improved target selectivity [1].

Integrative Approaches with Machine Learning

Recent advances integrate chemical genetics with machine learning algorithms to enhance MoA prediction:

Feature Representation: Drugs are represented as molecular graphs that preserve structural information, with node features computed using circular algorithms adapted from Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) [7].

Model Training: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) learn latent features of molecular structures, while Convolutional Neural Networks process gene expression data from cell lines [7].

Prediction and Interpretation: Trained models predict drug response levels and leverage deep learning attribution approaches (GNNExplainer, Integrated Gradients) to identify active substructures and significant genes, revealing potential mechanisms of action [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Genetics

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Wide CRISPRi Library | Enables titratable gene knockdown for essential and non-essential genes | M. tuberculosis library: ~90,000 sgRNAs [5] |

| Barcoded Mutant Libraries | Tracking mutant fitness in pooled screens | Yeast knockout collection, E. coli Keio collection |

| Targeted Chemical Libraries | Screening against specific protein families | Kinase-focused libraries, GPCR-directed collections [4] |

| Natural Product Libraries | Source of bioactive compounds with privileged structures | Traditional medicine compounds, microbial extracts [4] |

| Analog-Sensitive Kinase Alleles | Engineering selective inhibition | Bump-and-hole kinase variants [6] [2] |

| PROTAC Molecules | Targeted protein degradation | Heterobifunctional E3 ligase recruiters [1] |

| Fragment Libraries | Identifying weak binders for optimization | Low molecular weight (<300 Da) compound collections |

| Phenotypic Reporter Cell Lines | Monitoring specific pathway activation | GFP-labeled pathway reporters, biosensor cell lines |

Chemical genomics and chemical genetics provide powerful, complementary frameworks for mechanism of action discovery in the context of comparative chemical genomics research. The continuing evolution of genetic perturbation technologies (particularly CRISPR-based systems), combined with advanced computational approaches for data integration and analysis, promises to further enhance the resolution and throughput of these approaches. As chemical libraries expand in diversity and specificity, and as screening methodologies become increasingly sophisticated, these approaches will continue to transform our understanding of biological systems and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

The systematic assessment of gene-drug interactions represents a foundational paradigm in modern drug discovery and development. Chemical genetics, the core methodology underlying this principle, is defined as the systematic measurement of cellular outcomes resulting from the combined perturbation of genetic and chemical factors on a large scale [3]. This approach operates on the premise that by measuring how the perturbation of every gene affects cellular fitness upon exposure to different chemicals, researchers can comprehensively delineate drug function, reveal cellular targets, and identify mechanisms of drug resistance [3]. Within the broader context of comparative chemical genomics, these systematic interactions provide the critical data necessary for mechanism of action (MoA) discovery, bridging the gap between genetic variation and chemical sensitivity across biological systems.

The completion of the human genome project has provided an abundance of potential targets for therapeutic intervention, and chemogenomics strives to study the intersection of all possible drugs on all of these potential targets [4]. This systematic framework integrates target and drug discovery by using active compounds as molecular probes to characterize proteome-wide functions, enabling the parallel identification of biological targets and biologically active compounds [4].

Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

Core Approaches in Chemical Genetics

Systematic assessment of gene-drug interactions employs two complementary experimental strategies, each with distinct applications in MoA discovery:

Forward (classical) chemogenomics begins with the observation of a particular phenotype, followed by identification of small molecules that interact with this function. The molecular basis of the desired phenotype is initially unknown. Once modulators are identified, they serve as tools to identify the proteins responsible for the phenotype. For example, a loss-of-function phenotype might manifest as arrested tumor growth, with subsequent target identification revealing the specific protein responsible for this effect [4].

Reverse chemogenomics starts with identifying small compounds that perturb the function of a specific enzyme or protein in an in vitro system. After modulators are identified, the phenotype induced by the molecule is analyzed in cellular systems or whole organisms. This method validates or identifies the biological role of the protein in a physiological context, effectively confirming the protein's function in a biological response [4].

Genetic Perturbation Libraries

The power of chemical genetic approaches relies on comprehensive genetic perturbation libraries. These resources enable systematic assessment of gene function and its relationship to chemical sensitivity:

Table 1: Genetic Perturbation Libraries for Chemical Genetics

| Library Type | Perturbation Mechanism | Organisms | Applications in MoA Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss-of-function (LOF) | Gene knockouts, knockdowns (CRISPRi) | Bacteria, fungi, human cell lines | Identify genes essential for drug sensitivity/resistance |

| Gain-of-function (GOF) | Gene overexpression | Bacteria, fungi, human cell lines | Detect drug target overexpression effects |

| Heterozygous deletion | Reduced gene dosage (HIP) | Yeast, diploid organisms | Map drug targets for essential genes |

| Natural variation | Natural genetic diversity | Human cell lines, bacterial populations | Delineate drug function across populations |

The construction of genome-wide pooled mutant libraries and advances in multiplex sequencing approaches have reached a stage where such libraries can be created for almost any microorganism [3]. In microbial systems, barcoding approaches coupled with advanced sequencing technologies enable unprecedented throughput in tracking relative abundance and fitness of individual mutants in pooled libraries [3].

Workflow Visualization: Chemical Genetics Screening

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for systematic gene-drug interaction assessment:

Analytical Frameworks and Data Integration

Signature-Based MoA Identification

A powerful application of chemical genetics data involves drug signature comparison for mechanism of action identification. A drug signature comprises the compiled quantitative fitness scores for each mutant within a genome-wide deletion library following drug treatment. Drugs with similar signatures are likely to share cellular targets and/or cytotoxicity mechanisms, enabling a "guilt-by-association" approach that becomes more powerful as more drugs are profiled [3].

Machine learning algorithms including Naïve Bayesian and Random Forest classifiers have been successfully trained with chemical genetics data to predict drug-drug interactions and elucidate MoA [3]. These computational approaches can recognize the chemical-genetic interactions most reflective of a drug's mechanism of action from the complex dataset that includes pathways controlling intracellular drug concentration.

Cross-Resistance and Collateral Sensitivity Mapping

Chemical genetics enables systematic assessment of cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity patterns between drugs by measuring the contribution of every non-essential gene to resistance across multiple compounds:

This approach reveals whether mutations lead to resistance in both drugs (cross-resistance) or make cells more resistant to one drug but more sensitive to another (collateral sensitivity), providing insights for combination therapy strategies to mitigate drug resistance [3].

Database Integration and Normalization

The systematic nature of gene-drug interaction data requires sophisticated database infrastructure for normalization and integration. Resources like the Drug-Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb 4.0) aggregate information on drug-gene interactions and druggable genes from multiple diverse sources, incorporating 41 sources totaling over 100,000 interaction claims [8].

Recent advances include integration with crowdsourced efforts such as:

- Drug Target Commons: Providing 23,879 community-contributed drug-gene interaction claims

- Wikidata normalization: Enabling improved drug concept normalization

- NDEx integration: Facilitating network-based visualization of drug-gene relationships [8]

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Target Identification and Validation

Systematic assessment of gene-drug interactions provides two primary approaches for mapping drug targets:

1. Essential Gene Modulation For essential genes that serve as common drug targets, modulation of gene dosage provides powerful evidence for target identification. When a target gene is down-regulated, cells typically become more sensitive to the drug targeting that product, as less drug is required to titrate the remaining cellular target. Conversely, overexpression of the target gene often confers resistance to the drug [3]. In diploid organisms, heterozygous deletion mutant libraries (HaploInsufficiency Profiling or HIP) successfully map drug cellular targets by creating precisely this gene dosage effect.

2. Signature-Based Target Prediction Comparing chemical-genetic profiles across compound libraries can identify drugs with similar mechanisms of action through signature similarity. This approach has been particularly powerful in yeast and bacterial systems, where reference profiles for well-characterized compounds provide a basis for classifying novel compounds [3].

Clinical Translation and Personalized Medicine

The systematic assessment of gene-drug interactions provides the foundation for pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine approaches. The FDA has recognized the importance of specific pharmacogenetic associations, identifying subgroups of patients with certain genetic variants who are likely to have altered drug metabolism, differential therapeutic effects, or different risks of adverse events [9].

Table 2: Clinically Relevant Pharmacogenetic Associations

| Drug | Gene | Affected Subgroups | Clinical Consequence | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abacavir | HLA-B | *57:01 allele positive | Higher risk of hypersensitivity reactions | Contraindicated |

| Clopidogrel | CYP2C19 | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Reduced effectiveness, higher cardiovascular risk | Alternative therapy recommended |

| Codeine | CYP2D6 | Ultrarapid metabolizers | Life-threatening respiratory depression | Contraindicated in children |

| Azathioprine | TPMT/NUDT15 | Intermediate or poor metabolizers | Myelosuppression risk | Dosage reduction or alternative therapy |

| Carbamazepine | HLA-B | *15:02 allele positive | Severe skin reactions | Avoid unless benefits outweigh risks |

Recent epidemiological studies demonstrate that between 17.4% to 24.8% of individuals are exposed to potentially interacting drug pairs involving pharmacogenetic drugs, highlighting the clinical significance of these interactions [10]. The majority of these potential interactions involve CYP2D6 or CYP2C19 enzymes, emphasizing their central role in drug metabolism and interaction potential [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Gene-Drug Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-wide mutant libraries | Systematic gene perturbation | Yeast knockout collection, CRISPRi libraries for essential genes |

| Barcoded mutant pools | Tracking mutant fitness in competition assays | Pooled libraries with unique molecular barcodes |

| Targeted chemical libraries | Screening against specific target families | GPCR-focused, kinase-focused, nuclear receptor-focused libraries |

| Phenotypic assay systems | Multi-parametric readouts of drug response | High-content imaging, morphological profiling, growth rate assays |

| Normalization databases | Drug and gene concept standardization | DGIdb, ChEMBL, Wikidata, DrugBank |

| Machine learning algorithms | Pattern recognition in chemical-genetic data | Naïve Bayesian classifiers, Random Forest, neural networks |

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

The integration of artificial intelligence and multi-omics data represents the next frontier in systematic gene-drug interaction assessment. Recent advances demonstrate how AI-driven approaches, including graph neural networks (GNNs), natural language processing, and knowledge graph modeling, are being increasingly utilized to improve the detection, interpretation, and prevention of drug interactions [11].

Emerging applications include:

- Drug-drug-gene interactions: Assessing how concomitant medications alter pharmacogenetic relationships through phenoconversion [10]

- Multi-omics integration: Combining chemical genetics with transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data

- Cross-species comparative mapping: Leveraging synteny and collinearity between genomes to translate findings [12]

- Network-based pharmacology: Moving beyond single gene-drug pairs to complex interaction networks [8]

The convergence of systematic gene-drug interaction assessment with these emerging technologies holds profound promise for advancing drug discovery, target validation, and personalized therapeutic strategies across diverse disease contexts.

The field of biological target discovery has undergone a fundamental transformation, shifting from a reductionist approach rooted in classical genetics to a holistic systems-level understanding enabled by large-scale chemical perturbation screening. This paradigm shift represents the core of comparative chemical genomics, which systematically maps the relationships between genetic variants and chemical compound effects to elucidate mechanisms of action (MoA) [3] [4]. Where classical genetics often studied single genes in isolation, chemical genomics employs systematic screening of targeted chemical libraries against entire drug target families—GPCRs, kinases, proteases, and more—with the dual goal of identifying both novel drugs and novel drug targets [4]. This approach has been revolutionized by advanced computational models capable of integrating heterogeneous data types, enabling researchers to navigate the complex biological networks that underlie disease processes and therapeutic interventions.

The completion of the human genome project provided an abundance of potential targets for therapeutic intervention, and chemogenomics strives to study the intersection of all possible drugs on all of these potential targets [4]. Modern artificial intelligence platforms now integrate multi-modal data—including transcriptomics, proteomics, phenotypic screens, and clinical data—to construct comprehensive biological representations that move beyond single-target approaches to a more holistic, systems-level understanding of biology [13]. This whitepaper examines the methodologies, computational frameworks, and experimental protocols that define this paradigm shift, providing researchers with practical guidance for implementing these approaches in their discovery pipelines.

Methodological Foundations: Experimental Approaches in Chemical Genomics

Core Strategic Frameworks

Chemical genomics employs two primary experimental strategies, each with distinct applications and workflows for mechanism of action discovery:

Forward Chemogenomics (Phenotype-based): This approach begins with a desired phenotype and works to identify small molecules that induce it, then uses these molecules as tools to identify the responsible protein targets [4]. For example, researchers might screen for compounds that arrest tumor growth without prior knowledge of the molecular target, then use hit compounds to identify the relevant biological pathway. The main challenge lies in designing phenotypic assays that efficiently lead from screening to target identification [4].

Reverse Chemogenomics (Target-based): This strategy starts with a specific protein target of interest and identifies small molecules that perturb its function in vitro, then analyzes the phenotypic consequences of this modulation in cellular or whole-organism contexts [4]. This approach has been enhanced by parallel screening capabilities and the ability to perform lead optimization across multiple targets within the same family simultaneously [4].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of chemical genomics approaches requires carefully selected research reagents and libraries. The table below details essential materials and their applications in perturbation studies:

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Chemical Genomics Studies

| Reagent/Library Type | Function & Application in MoA Discovery |

|---|---|

| Genome-wide mutant libraries (Loss-of-function/ Gain-of-function) [3] | Systematic assessment of gene contributions to fitness under chemical treatment; available as arrayed or pooled formats for high-throughput screening. |

| Targeted chemical libraries [4] | Compound collections focused on specific target families; include known ligands to leverage binding promiscuity for identifying novel targets within protein families. |

| CRISPRi libraries for essential genes [3] | Enable knockdown studies of essential genes not accessible via knockout; particularly valuable for identifying drug targets when the target is part of a protein complex. |

| Barcoded mutant pools [3] | Facilitate tracking of relative mutant abundance via sequencing; enable fitness profiling with unprecedented throughput and dynamic range in pooled screens. |

Workflow Integration

The experimental workflow typically begins with the construction or acquisition of appropriate genetic and chemical libraries, followed by parallel screening under controlled conditions. Advanced phenotyping approaches—including high-throughput microscopy and image analysis—generate multidimensional data sets that reveal the functional consequences of perturbations [3]. The integration of these complementary approaches creates a powerful framework for elucidating complex biological relationships, with forward chemogenomics identifying phenotypic modulators and reverse chemogenomics validating their mechanistic basis.

Computational Advances: Large Perturbation Models and AI Platforms

The Emergence of Large Perturbation Models

A significant breakthrough in chemical genomics has been the development of Large Perturbation Models (LPMs), deep learning architectures specifically designed to integrate heterogeneous perturbation data [14]. The LPM framework represents perturbation experiments through three disentangled dimensions: the perturbation itself (P), the experimental readout (R), and the biological context (C) [14]. This PRC-conditioned architecture enables learning from diverse experiments that may not overlap in all dimensions, allowing the model to predict outcomes for unseen perturbation combinations.

LPMs adopt a decoder-only architecture that explicitly conditions on symbolic representations of experimental context, enabling them to learn perturbation-response rules disentangled from the specific context in which readouts were observed [14]. This approach has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in predicting post-perturbation transcriptomes and has proven effective even in low-dimensional settings with non-transcriptomic readouts such as viability measurements [14]. When trained on pooled data from diverse sources, LPMs outperform existing methods including Compositional Perturbation Autoencoder (CPA) and GEARS across multiple biological discovery tasks [14].

AI Platforms for Holistic Biology

Beyond LPMs, specialized AI platforms have emerged that embrace a holistic approach to biology, moving beyond reductionist models:

Pharma.AI (Insilico Medicine): Integrates policy-gradient-based reinforcement learning with generative models, leveraging approximately 1.9 trillion data points from over 10 million biological samples and 40 million documents [13]. The platform employs knowledge graph embeddings to encode biological relationships into vector spaces, using attention-based neural architectures to focus on biologically relevant subgraphs [13].

Recursion OS: A vertically integrated platform that maps trillions of biological, chemical, and patient-centric relationships using approximately 65 petabytes of proprietary data [13]. Key components include Phenom-2 (a vision transformer trained on 8 billion microscopy images) and specialized models for molecular property prediction that integrate proprietary phenomics data [13].

Iambic Therapeutics: Features an integrated pipeline of three specialized AI systems—Magnet for molecular generation, NeuralPLexer for predicting protein-ligand complexes, and Enchant for predicting human pharmacokinetics—creating an iterative, model-driven workflow [13].

These platforms exemplify the shift toward systems biology representation, using multi-modal data integration to capture the complexity of biological networks rather than focusing on isolated components.

Mapping Unified Perturbation Spaces

A powerful application of these computational approaches is the creation of unified embedding spaces that encompass both genetic and chemical perturbations [14]. When LPMs are trained on diverse perturbation data, they naturally cluster pharmacological inhibitors near genetic interventions targeting the same genes, enabling the study of drug-target interactions in a unified latent space [14]. For example, mTOR inhibitors cluster closely with CRISPR interventions targeting the MTOR gene, while compounds with reported off-target activity, such as benfluorex and pravastatin, appear anomalously positioned relative to their putative targets, potentially revealing secondary mechanisms [14]. This integrated representation facilitates the identification of shared molecular mechanisms across perturbation types.

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

Protocol: Chemical-Genetic Interaction Screening

The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for conducting chemical-genetic interaction screens to identify mechanisms of action:

Library Preparation:

- Utilize a pooled genome-wide deletion library (for non-essential genes) or CRISPRi library (for essential genes) [3].

- Prepare the chemical compound of interest at multiple concentrations, including sublethal doses.

Screen Execution:

- Inoculate the mutant library in appropriate media and divide into treatment (compound) and control (DMSO/vehicle) groups.

- Culture for multiple generations to allow fitness differences to manifest (typically 5-10 population doublings).

Sample Processing and Sequencing:

- Extract genomic DNA from all samples at endpoint.

- Amplify barcode regions with PCR using indexed primers for multiplexing.

- Sequence barcode amplicons using high-throughput sequencing platforms.

Fitness Profile Calculation:

- Count barcode reads for each strain in treatment and control conditions.

- Calculate normalized fitness scores for each mutant: Fitness = log~2~(treatment counts/control counts).

- Compile fitness scores across all mutants to generate the compound's "chemical-genetic interaction profile" [3].

Protocol: MoA Identification Through Signature Comparison

This protocol describes how to use chemical-genetic profiles for mechanism of action identification:

Reference Database Construction:

- Generate chemical-genetic interaction profiles for multiple compounds with known mechanisms of action.

- Curate a reference database of profiles, ensuring consistent normalization across all experiments.

Similarity Analysis:

- Calculate similarity metrics (e.g., Pearson correlation) between the query compound's profile and all reference profiles.

- Apply machine learning algorithms (Random Forest or Naïve Bayesian) trained on chemical-genetic data to recognize patterns reflective of specific MoAs [3].

Target Hypothesis Generation:

Experimental Validation:

- Test compound against overexpression strains of putative targets; hypersensitivity suggests direct target engagement [3].

- Utilize secondary assays (biochemical, transcriptional) to confirm hypothesized mechanism.

Quantitative Profiling and Cross-Resistance Assessment

Chemical-genetic approaches enable quantitative assessment of resistance relationships between compounds, providing insights into their mechanisms of action:

Table 2: Chemical-Genetic Profiling for MoA Identification

| Method Category | Key Measurable Outputs | Interpretation in MoA Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Haploinsufficiency/CRISPRi Profiling [3] | - Hypersensitivity scores for essential gene knockdowns- Gene ontology enrichment of sensitive mutants | Identifies direct cellular targets; hypersensitivity for target gene suggests direct engagement. |

| Homozygous Deletion Profiling [3] | - Fitness defect scores for non-essential gene knockouts- Pathway enrichment of sensitive/resistant mutants | Reveals pathways controlling drug sensitivity/resistance and compensatory mechanisms. |

| Signature-Based Comparison [3] [4] | - Pearson correlation to reference compounds- Machine learning classification probabilities | "Guilt-by-association" approach identifies compounds with shared targets or mechanisms. |

| Cross-Resistance Mapping [3] | - Correlation of mutant fitness profiles across drug pairs- Identification of collateral sensitivity relationships | Informs on shared resistance mechanisms and potential combination therapies. |

Visualization of Workflows and Biological Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate key workflows and relationships in chemical genomics, created using DOT language with the specified color palette and contrast requirements.

Diagram 1: Paradigm Shift from Classical Genetics to Chemical Perturbations

Diagram 2: LPM Framework for Chemical Genomics

The paradigm shift from classical genetics to chemical perturbations represents a fundamental transformation in target discovery methodology. By integrating diverse perturbation data through advanced computational models like LPMs, researchers can now navigate biological complexity with unprecedented resolution, mapping unified perturbation spaces that reveal shared mechanisms across genetic and chemical interventions [14]. This holistic, systems-level approach, powered by AI platforms capable of multi-modal data integration, enables more efficient and comprehensive mechanism of action discovery, accelerating the development of novel therapeutics for complex diseases [13]. As these technologies continue to evolve, they promise to further bridge the gap between initial compound screening and validated target identification, reshaping the future of drug discovery.

The systematic identification of a compound's Mechanism of Action (MoA), its associated resistance pathways, and its potential for interactions with other drugs constitutes a critical frontier in modern pharmacotherapy. Traditional, siloed approaches are increasingly being supplanted by integrated, comparative frameworks that leverage genomic, chemical, and phenotypic data on a large scale [3] [15]. Chemical genomics, which involves the systematic assessment of how genetic variation affects a drug's activity, provides a powerful foundation for these approaches [16] [3]. By quantitatively measuring the fitness of thousands of genetic mutants under drug treatment, researchers can delineate the cellular function of a drug, revealing its targets, its path into and out of the cell, and its detoxification mechanisms [3]. This review provides an in-depth technical guide to the core biological insights and methodologies driving this field, with a focus on scalable experimental and computational protocols designed for researchers and drug development professionals.

Mechanism of Action (MoA) Identification

Computational and Multi-Omics Approaches

A drug's MoA is a complex phenomenon involving direct target interactions and the subsequent modulation of biochemical pathways [15]. Contemporary bioinformatic methods for MoA investigation are increasingly reliant on the integration of multi-omics data and Machine Learning (ML). These approaches are essential for managing the vast, complex datasets generated by modern high-throughput technologies and for moving from a molecular to a systemic understanding of drug activity [15].

Powerful methods include the construction of specific drug-response networks and the use of multi-layer graph neural networks that integrate diverse data types, such as gene expression profiles, protein-protein interactions, and chemical structures [15]. For instance, the DTIAM framework exemplifies a unified approach that uses self-supervised pre-training on molecular graphs of drugs and primary sequences of proteins to learn meaningful representations, which subsequently enhance the prediction of drug-target interactions, binding affinities, and activation/inhibition MoAs [17]. A key advantage of these computational methods is their application in drug repurposing, where they can reveal new therapeutic applications for existing drugs by elucidating effects on previously unrecognized pathways [15].

Experimental Chemical Genetics

Experimental chemical genetics provides a direct, systematic method for MoA identification. This approach utilizes genome-wide libraries of mutants—including loss-of-function (e.g., knockout, knockdown) or gain-of-function (e.g., overexpression) mutants—which are then profiled for fitness changes in the presence of a drug [3].

There are two primary strategies for identifying drug targets using these libraries:

- Modulating Essential Gene Dosage: For essential genes, which are frequent drug targets, haploinsufficiency profiling (HIP) in diploid organisms or CRISPR-interference (CRISPRi) knockdown libraries in haploid organisms can be used. If reducing the dose of a gene product increases sensitivity to a drug, it suggests that gene is the target [3]. Conversely, overexpressing the target gene often confers resistance to the drug, as the cell now has more of the protein that the drug must inhibit [3].

- Drug Signature Comparison: This "guilt-by-association" approach involves compiling quantitative fitness scores for every non-essential gene mutant in the presence of a drug. Drugs with highly similar fitness signatures are inferred to share cellular targets and/or mechanisms of cytotoxicity [3]. The power of this method grows with the number of drugs profiled, enabling the identification of repetitive "chemogenomic" signatures.

Table 1: Key Methodologies for MoA Identification

| Methodology | Core Principle | Key Outputs | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Supervised Pre-training (e.g., DTIAM) [17] | Learns representations of drugs and targets from large unlabeled datasets (molecular graphs, protein sequences). | Unified prediction of interactions, binding affinities, and activation/inhibition. | Reduces reliance on large-scale labeled data; improves performance in cold-start scenarios. |

| Chemical Genetic Profiling [3] | Measures fitness of genome-wide mutant libraries under drug treatment. | Drug-target hypotheses; drug fitness signatures. | Requires construction and maintenance of mutant libraries; hits may include resistance/efflux pathways. |

| Multi-Omics Data Integration & ML [15] | Integrates diverse data layers (e.g., transcriptomic, proteomic) using network models and machine learning. | System-level view of drug activity; novel repurposing hypotheses. | Dependent on data quality and quantity; requires sophisticated computational infrastructure. |

Experimental Protocol: Genome-Wide Chemical Genetics Screen

Objective: To identify genes involved in the susceptibility or resistance to a drug of unknown MoA using a pooled knockout library. Materials:

- Genome-wide pooled knockout mutant library (e.g., for yeast or E. coli).

- Drug of interest dissolved in appropriate solvent.

- Culture medium and reagents for genomic DNA extraction.

- PCR primers for amplifying unique molecular barcodes.

- Next-generation sequencing platform.

Procedure:

- Culture Expansion: Grow the pooled mutant library in permissive medium to mid-log phase.

- Drug Treatment: Split the culture into two aliquots. Treat one aliquot with the drug at a predetermined sub-lethal concentration (e.g., IC50). The other aliquot serves as an untreated control.

- Harvesting and Sampling: Incubate both cultures for several generations to allow for fitness differences to manifest. Harvest cells by centrifugation at multiple time points if conducting a time-course experiment.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from both treated and untreated cell pellets.

- Barcode Amplification & Sequencing: Amplify the unique molecular barcodes from each sample via PCR. Pool the PCR products and subject them to high-throughput sequencing.

- Data Analysis: Map the sequenced barcodes to their corresponding gene mutants. Calculate the relative abundance (fitness) of each mutant in the treated sample compared to the control. Genes whose mutants show significant fitness defects are implicated in buffering the cell against the drug, while those that become enriched may indicate resistance mechanisms.

Diagram 1: Chemical genetics screen workflow.

Drug Resistance Mechanisms

Insights from Chemical Genetics

Chemical-genetic screens are exceptionally rich sources of information for dissecting drug resistance. They can comprehensively map the network of genes that, when mutated, confer resistance or sensitivity to a drug. This network includes not only the direct drug target but also genes involved in:

- Drug Uptake and Efflux: Transporters and pumps that control the intracellular concentration of the drug [3].

- Drug Detoxification: Enzymes that modify or degrade the drug, rendering it inactive [3].

- Pathway Compensation: Components of redundant or parallel biochemical pathways that can bypass the inhibition caused by the drug.

A key insight from these studies is that microbes possess a vast, often cryptic, capacity for intrinsic antibiotic resistance. Many drug transporters are not optimally expressed under standard laboratory conditions but can be activated by evolutionary pressure, leading to acquired resistance [3].

Predicting Cross-Resistance and Collateral Sensitivity

Chemical-genetic profiles enable the systematic assessment of cross-resistance (where a mutation confers resistance to multiple drugs) and collateral sensitivity (where resistance to one drug causes hypersensitivity to another) [3]. By comparing the fitness signatures of two drugs, one can predict if resistance mechanisms will overlap. This is superior to traditional methods that evolve resistance to one drug and test a limited number of clones against others, as it surveys the contribution of every non-essential gene simultaneously. Understanding these relationships is crucial for designing intelligent drug cycling or combination therapies that can mitigate or even reverse the evolution of resistance [3].

Table 2: Resistance Mechanisms Revealed by Genomic Approaches

| Mechanism Category | Description | Example Insights from Chemical Genetics |

|---|---|---|

| Target Alteration | Mutations in the drug's target protein that reduce drug binding. | Overexpression of the target gene can confer resistance; identified via GOF libraries. |

| Drug Uptake/Efflux | Reduced import or increased export of the drug from the cell. | Identification of cryptic transporters not wired to sense the drug under standard conditions [3]. |

| Drug Inactivation | Enzymatic modification or degradation of the drug. | Mutants in detoxification enzymes may show increased sensitivity. |

| Pathway Bypass | Activation of alternative pathways to compensate for the inhibited function. | Genes in compensatory pathways show synthetic lethal interactions with the drug. |

Drug-Drug Interactions (DDIs)

The Clinical and Computational Challenge

Drug-drug interactions pose a significant clinical challenge, particularly in aging populations with polypharmacy, where they can lead to reduced therapeutic efficacy or adverse drug reactions (ADRs) [18] [19]. Traditional DDI detection methods, such as clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance, are often retrospective and slow to identify rare or complex interactions [19]. Computational methods, particularly those powered by artificial intelligence (AI), are enabling a shift towards proactive and integrated strategies [19].

AI and Multi-Dimensional Feature Fusion

Advanced deep learning models are demonstrating state-of-the-art performance in predicting DDIs. For example, the Multi-Dimensional Feature Fusion (MDFF) model integrates one-dimensional (e.g., SMILES sequences), two-dimensional (molecular graph), and three-dimensional (geometric) features of drugs to create comprehensive representations for DDI prediction [20]. This multi-dimensional approach captures different facets of chemical structure and function, leading to more accurate predictions. Crucially, such models are beginning to see validation with real-world data, such as hospital adverse drug reaction reports, bridging the gap between computational power and clinical application [20].

Furthermore, AI methodologies like graph neural networks (GNNs) and natural language processing (NLP) are being integrated into clinical decision support systems (CDSS). These tools can mine complex datasets, including electronic health records (EHRs) and biomedical literature, to improve the detection and interpretation of DDIs across diverse patient demographics [19].

Predicting Interactions from Chemical Genetics

Chemical genetics also offers a path to predict DDIs. Machine-learning algorithms, such as Naïve Bayesian and Random Forest classifiers, can be trained on chemical-genetic interaction data to forecast how two drugs will behave in combination [3]. The underlying principle is that drugs with similar chemical-genetic interaction profiles are more likely to interact when combined. This allows for the in-silico exploration of the enormous combinatorial drug space, helping to prioritize combinations for empirical testing [3].

Table 3: Methodologies for Predicting Drug-Drug Interactions

| Methodology | Underlying Principle | Key Advantage | Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Dimensional Feature Fusion (MDFF) [20] | Integrates 1D, 2D, and 3D structural features of drugs via deep learning. | Creates a comprehensive drug representation; high predictive accuracy. | Validated with real-world hospital adverse event reports. |

| AI & Knowledge Graphs [19] | Uses graph neural networks on heterogeneous data (EHRs, biomedical networks). | Can uncover complex, population-specific DDI risks. | Powers clinical decision support systems (CDSS). |

| Chemical Genetics & ML [3] | Applies ML to drug-mutant fitness profiles to predict drug-pair behavior. | Based on functional biological data rather than purely structural similarity. | Informs intelligent design of combination therapies and adjuvant strategies. |

Diagram 2: Multi-dimensional feature fusion for DDI prediction.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Genomic Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Application in MoA/DDI Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Wide Mutant Library (e.g., knockout, CRISPRi) [3] | Provides a collection of strains, each with a specific gene perturbation. | Core reagent for chemical genetic screens to identify genes affecting drug sensitivity. |

| Unique Molecular Barcodes [3] | DNA sequences that uniquely tag each mutant in a pooled library. | Enables tracking of mutant fitness in pooled screens via high-throughput sequencing. |

| Bioinformatic Databases (e.g., DrugBank, ChEMBL, STITCH) [21] [15] | Repositories of drug, target, and interaction data. | Provide curated data for training and validating computational models (e.g., DTIAM, MDFF). |

| AI/ML Platforms & Tools (e.g., Graph Neural Networks) [19] [15] | Software and algorithms for analyzing complex, high-dimensional data. | Used for predicting DDIs, analyzing drug-response networks, and classifying MoA. |

| Real-World Data Sources (e.g., EHRs, Adverse Event Reports) [20] [19] | Collections of clinical data from patient populations. | Critical for validating computational DDI predictions and understanding clinical relevance. |

In the field of comparative chemical genomics, elucidating the mechanism of action (MoA) for novel compounds represents a fundamental challenge. Two technologies form the essential backbone for modern MoA discovery research: genome-wide mutant libraries and high-throughput phenotyping (HTP). Genome-wide mutant libraries provide a systematic, unbiased platform for probing gene function by enabling researchers to screen every gene in an organism simultaneously. The most renowned example is the Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) deletion collection, a set of over 20,000 knockout strains that includes homozygous and heterozygous diploid strains for 5,916 genes and haploid strains for every non-essential gene [22]. Complementary to this, high-throughput phenotyping employs automated, non-invasive sensing technologies and data analysis to quantitatively assess complex traits across vast populations [23] [24]. When integrated, these toolkits create a powerful discovery engine; the mutant libraries reveal genetic vulnerabilities and drug-target interactions, while HTP platforms precisely quantify the resulting phenotypic changes, from cellular morphology to growth dynamics. This synergistic approach allows researchers to move seamlessly from a chemical compound to its cellular target and the broader functional context, thereby deconvoluting complex pharmacological actions in an efficient and comprehensive manner.

Genome-Wide Mutant Libraries: Construction and Applications

The Yeast Deletion Collection as a Model System

The construction of the S. cerevisiae deletion collection stands as a landmark achievement in functional genomics. This library was created by a consortium of laboratories using a precise gene replacement strategy. Each of the 5,916 yeast genes was systematically deleted and replaced with a kanamycin-resistance cassette flanked by two unique 20-nucleotide "molecular barcodes" (uptag and downtag) [22]. This barcoding system is the key technological innovation that enables high-throughput analysis. It allows for the pooled growth of thousands of mutant strains under a single experimental condition, followed by the quantitative identification of each strain's abundance via DNA microarray hybridization that targets these barcode sequences [22]. The collection is comprehensively archived and accessible to the global research community from repositories such as Euroscarf, ATCC, and Invitrogen [22].

Key Experimental Protocols for MoA Discovery

The power of genome-wide libraries in MoA research is realized through specific, barcode-enabled experimental protocols.

- Chemical Genomic Screens: This primary method for MoA discovery involves growing the pooled haploid deletion mutants in the presence of a bioactive compound. Genomic DNA is extracted from the pool before and after exposure, and the barcodes are amplified and hybridized to a microarray. Mutants that are hypersensitive (showing reduced abundance) or resistant (showing increased abundance) to the compound are identified. A hypersensitive response often indicates that the deleted gene product functions in a pathway or process that becomes essential for survival in the presence of the drug, thereby pinpointing the drug's cellular target or buffering pathways [22].

- Synthetic Genetic Array (SGA) Analysis: SGA is a method for systematically constructing and analyzing double mutants. A haploid "query" strain with a mutation in a gene of interest is crossed mechanically with the arrayed haploid deletion mutant collection. Through a series of robotic replica plating and selection steps, haploid double mutants are generated. Synthetic sick or synthetic lethal interactions—where the double mutant is non-viable but each single mutant is viable—reveal functional interactions and redundancy between genes, mapping out genetic networks [22].

- Synthetic Lethality Analysis by Microarray (SLAM): A related method, SLAM, also uses pooled pools but involves transforming the deletion pool with a cassette that replaces a gene of interest. The transformed and control pools are processed similarly to chemical genomic screens, with barcode hybridization revealing synthetic lethal partners by their absence in the experimental pool [22].

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genome-Wide Screening

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function and Application in MoA Discovery |

|---|---|

| Yeast Deletion Collection (Homozygous/Heterozygous Diploid, Haploid) | Comprehensive set of knockout strains for fitness profiling under chemical stress [22]. |

| Unique Molecular Barcodes (UPTAG, DOWNTAG) | Enables pooled growth and quantitative tracking of mutant abundance via microarray hybridization [22]. |

| SGA-Compatible Query Strains | Genetically engineered strains used to interrogate genetic interaction networks for a gene of interest [22]. |

| Euroscarf/ATCC/Invitrogen Repositories | Sources for obtaining the complete, quality-controlled mutant collections [22]. |

High-Throughput Phenotyping: Platforms and Data Analysis

Principles and Imaging Platforms

High-throughput phenotyping (HTP) is defined as the application of automated, non-invasive sensing technologies to assess complex plant or microbial traits on a large scale [23] [24]. It addresses the major bottleneck of traditional, manual phenotyping, which is laborious, subjective, and low-throughput. The core principle of HTP is to capture phenotypic data using various sensors, transforming analog traits into quantitative, digital data that can be statistically analyzed and linked to genomic information. A key advantage is the ability to capture temporal and spatial data throughout a developmental cycle or in response to a stimulus like a drug, providing a dynamic view of phenotypic responses [23].

HTP platforms are diverse and can be categorized as follows:

- Ground-Based Imaging Platforms: These include conveyor-based systems (e.g., LemnaTec Scanalyzers) where plants or plates are moved automatically past imaging stations. These systems often integrate multiple sensors, including Red-Green-Blue (RGB), hyperspectral, thermal, and fluorescence imaging [23].

- Aerial Platforms: Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs or drones) equipped with similar sensors are used for field-based phenotyping, allowing for the assessment of large populations in agricultural settings [23].

- Automated Cellular Phenotyping Platforms: For microbial systems like yeast, automated microscopes and flow cytometers can perform high-content screening, capturing data on cell morphology, size, fluorescence, and other cellular features in response to genetic or chemical perturbations [22] [24].

Table 2: Exemplary HTP Platforms and Their Applications

| Platform Name | Traits Recorded | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PHENOPSIS | Plant responses to soil water stress [23] | Abiotic stress phenotyping in Arabidopsis |

| LemnaTec 3D Scanalyzer | Salinity tolerance traits [23] | Abiotic stress phenotyping in rice |

| HyperART | Leaf chlorophyll content, disease severity [23] | Biotic and abiotic stress in barley, maize, tomato |

| PlantScreen | Drought tolerance traits [23] | Abiotic stress phenotyping in rice |

| Automated Microscopy | Cell morphology, size, organelle structure [22] | Morphological profiling of yeast mutant libraries |

Machine Learning and Deep Learning for Phenotypic Data Analysis

The application of HTP generates massive, complex datasets, which necessitates advanced computational tools for analysis. Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) have become indispensable for extracting meaningful biological information from HTP data [23].

- Machine Learning (ML): ML is a multidisciplinary approach that uses probability, statistics, and decision theory to find patterns in large datasets. In HTP, traditional ML approaches like support vector machines or random forests have been used for tasks such as classifying diseased versus healthy plants based on image features [23]. A significant limitation of traditional ML is the need for manual "feature engineering," where experts must define and extract relevant traits from the raw data (e.g., leaf area, color histogram) [23].

- Deep Learning (DL): DL, a subset of ML, has emerged as a more powerful solution. DL models, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), can automatically learn a hierarchy of relevant features directly from raw images, bypassing the need for manual feature engineering [23]. These models have achieved state-of-the-art performance in image classification, object recognition, and image segmentation, making them ideal for tasks like counting cells, identifying mutant colonies, or segmenting leaves from a complex background [23].

Diagram 1: HTP data analysis workflow, showing parallel ML and DL paths.

Integrated Workflows for Mechanism of Action Discovery

The true power for MoA discovery is realized when genome-wide mutant libraries are interrogated using high-throughput phenotyping and computational analysis. This integrated approach provides a multi-faceted view of a compound's effect on a biological system.

A typical integrated workflow begins with a chemical genomic screen of the pooled yeast deletion library against a compound of unknown MoA. The barcode-based readout identifies a set of hypersensitive and resistant mutants. This genetic information provides the first clues about the affected pathways. In parallel, the same compound can be applied to a wild-type strain, which is then subjected to high-throughput, high-content imaging to quantify a multitude of cellular features—such as cell size, shape, nuclear intensity, and cytoskeletal structure—generating a detailed "phenotypic fingerprint" [22] [24].

This fingerprint can be compared to a reference database of profiles from compounds with known MoAs, a approach known as phenotypic profiling. If the profile of the unknown compound closely matches that of a known drug, it strongly suggests a similar MoA. The genetic data from the chemical genomic screen serves to validate and refine this hypothesis. For instance, if a compound produces a phenotypic profile similar to a DNA-damaging agent and the chemical genomic screen shows hypersensitivity in mutants of DNA repair pathways, the evidence for a related MoA becomes compelling [22] [25].

Diagram 2: Integrated MoA discovery workflow combining genetic and phenotypic data.

Table 3: Quantitative Discoveries from the Yeast Deletion Collection (Selected Examples)

| Condition, Treatment, or Phenotype Screened | Number of Genes Identified | Key Insights for MoA |

|---|---|---|

| Response to DNA-damaging agents, radiation [22] | >170 | Expanded network of DNA damage response genes. |

| Unfolded protein response (Huntingtin, α-synuclein) [22] | 52 / 86 | Identified modifiers of toxic protein aggregation. |

| Sensitivity to anticancer agent Bleomycin [22] | 231 (hypersensitive) | Revealed Agp2p as a novel transporter. |

| Altered cell morphology [22] | Not quantified | Identified novel genes governing cell shape. |

| Glycogen storage [22] | 324 (low), 242 (high) | Defined genetic regulators of carbon metabolism. |

| Saline response [22] | ~500 | Uncovered systems-level response to osmotic stress. |

Genome-wide mutant libraries and high-throughput phenotyping have irrevocably transformed the landscape of basic and translational research, providing an essential toolkit for the systematic deconvolution of gene function and drug mechanism. The integration of these tools allows for a powerful, multi-parametric approach to comparative chemical genomics, generating both genetic interaction data and deep phenotypic profiles that together constrain and illuminate the possible mechanisms of action for novel bioactive compounds.

The future of this field lies in the continued refinement of both tools and their synergistic application. For mutant libraries, this includes the development of more complex human cell-based CRISPR knockout and activation libraries. For HTP, advancements in sensor technology, automated sample handling, and especially in artificial intelligence, will further increase throughput, resolution, and analytical depth. The application of more sophisticated DL models will enable the discovery of subtle, previously indiscernible phenotypic patterns directly from raw image data. As these technologies mature and become more accessible, their adoption will be crucial for accelerating the drug discovery pipeline, from initial target identification to understanding compound efficacy and resistance mechanisms, ultimately leading to more effective and targeted therapies.

Methodologies in Action: High-Throughput Screening and Target Deconvolution Strategies

Chemogenomics represents a systematic approach in modern drug discovery that investigates the interaction between small molecules and biological target families on a genomic-wide scale [4]. The core premise of chemogenomics is the parallel screening of targeted chemical libraries against families of related drug targets—such as G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), kinases, nuclear receptors, and proteases—with the ultimate goal of identifying novel drugs and drug targets [4] [26]. This field has evolved as an essential strategy for bridging the gap between genomic information and functional pharmacology, particularly after the completion of the human genome project revealed thousands of potential targets for therapeutic intervention [4].

The fundamental principle governing chemogenomics is that ligands designed for one member of a target family will often bind to other family members, enabling the construction of targeted chemical libraries that collectively interact with a high percentage of proteins within that family [4]. This approach integrates target and drug discovery by using small molecule compounds as chemical probes to characterize proteome functions [4]. Unlike genetic approaches that modify gene sequences, chemogenomics enables researchers to modify protein function in real-time, observing phenotypic changes after compound addition and their reversibility upon withdrawal [4].

Two complementary paradigms have emerged as the foundational frameworks for chemogenomics investigation: forward chemogenomics (classical approach) and reverse chemogenomics [4]. These approaches mirror established concepts in genetics, applying similar logical frameworks to chemical perturbation rather than genetic modification [27]. The strategic implementation of both forward and reverse chemogenomics has transformed early drug discovery by enabling the parallel identification of biological targets and biologically active compounds [4].

Conceptual Frameworks: Forward and Reverse Chemogenomics

Forward Chemogenomics: From Phenotype to Target

Forward chemogenomics, also referred to as classical chemogenomics or forward chemical genetics, begins with the observation of a particular phenotype and works backward to identify the small molecules and their protein targets responsible for this phenotypic effect [4] [28] [27]. In this approach, the molecular basis of the desired phenotype is initially unknown [4]. Researchers first identify small molecules that induce a specific phenotypic response in cells or whole organisms, then use these active compounds as tools to isolate and characterize the protein targets responsible for the observed effect [4].

The forward approach is particularly valuable for discovering novel biology and unexpected therapeutic targets, as it does not rely on preconceived hypotheses about which targets are important [27]. For example, a loss-of-function phenotype such as arrest of tumor growth would be studied by identifying compounds that produce this effect, followed by target identification [4]. The primary challenge in forward chemogenomics lies in designing phenotypic assays that enable direct progression from screening to target identification [4].

Reverse Chemogenomics: From Target to Phenotype

Reverse chemogenomics operates in the opposite direction, beginning with a known or hypothesized protein target and seeking small molecules that modulate its activity, then characterizing the resulting phenotypes [4] [28]. This approach typically starts with in vitro enzymatic assays to identify compounds that perturb the function of a specific enzyme or receptor [4]. Once modulators are identified, researchers analyze the phenotypes induced by these molecules in cellular systems or whole organisms [4].

This strategy closely resembles target-based approaches traditionally used in drug discovery and molecular pharmacology but enhanced by parallel screening capabilities and the ability to perform lead optimization across multiple targets belonging to the same family [4]. Reverse chemogenomics is particularly useful for validating the therapeutic potential of targets that have been identified through genomic or other omics studies [28]. The approach aims to confirm the biological role of specific proteins by observing phenotypic changes resulting from their chemical modulation [4].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Forward and Reverse Chemogenomics

| Characteristic | Forward Chemogenomics | Reverse Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Phenotype of interest | Known protein target |

| Screening Approach | Phenotypic screening in cells or organisms | Target-based screening (in vitro assays) |

| Primary Goal | Identify compounds causing phenotype, then find targets | Identify compounds modulating target, then characterize phenotypes |

| Hypothesis | Minimal assumptions about relevant targets | Target is validated and linked to disease |

| Key Challenge | Target deconvolution | Phenotypic characterization |

| Historical Analogy | Forward genetics | Reverse genetics |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Forward Chemogenomics Workflow and Protocols

The forward chemogenomics workflow begins with establishing a robust phenotypic assay that recapitulates a disease-relevant process [27] [29]. This involves several methodical steps:

Step 1: Phenotypic Assay Development Researchers design cell-based or organism-based assays that measure functionally relevant endpoints such as cell viability, morphological changes, migration, differentiation, or reporter gene expression [27]. A critical consideration is ensuring the assay has sufficient throughput to screen compound libraries while maintaining biological relevance. For example, in cancer research, assays may measure inhibition of tumor cell growth or induction of apoptosis [28].

Step 2: Compound Library Screening Chemical libraries are screened against the phenotypic assay to identify "hits" that produce the desired effect [28]. These libraries may consist of natural products, synthetic compounds, or specialized collections such as the Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds (LOPAC) or the NCATS Mechanism Interrogation PlatE [26]. Recent advances have emphasized the importance of using compounds with known safety profiles or "privileged structures" to improve success rates [4].

Step 3: Target Deconvolution This critical step identifies the protein target(s) responsible for the observed phenotype. Multiple approaches are employed:

- Affinity Purification: Small molecules are immobilized on solid supports and used as bait to capture binding proteins from cell lysates [27]. Control experiments with inactive analogs help distinguish specific binding partners. Proteins are identified through mass spectrometry.

- Photoaffinity Labeling: Compounds are modified with photoactivatable groups that form covalent bonds with target proteins upon UV irradiation, facilitating isolation and identification [27].

- Resistance Mutagenesis: Cells are selected for resistance to the compound, and sequencing identifies mutations that confer resistance, potentially in the direct target or related pathways.

- Genetic Interaction Profiling: In model organisms like yeast, systematic analysis of gene deletion collections identifies genetic interactions that suggest target pathways [30].

Step 4: Target Validation Candidate targets are validated using orthogonal approaches such as CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing, RNA interference, or dominant-negative constructs to confirm that target modulation reproduces the original phenotype [27].

Reverse Chemogenomics Workflow and Protocols

The reverse chemogenomics approach follows a contrasting pathway that begins with target selection:

Step 1: Target Selection and Validation Proteins are selected based on genomic data, disease association studies, or pathway analysis [28]. Targets are typically members of well-characterized families such as kinases, GPCRs, or nuclear receptors [4]. Credentialing establishes the relevance of the target to a biological pathway or disease process [27].

Step 2: Biochemical Assay Development In vitro assays are developed to measure compound effects on target activity. For enzymes, this may involve direct measurement of substrate conversion. For receptors, binding assays or functional assays using secondary messengers are employed [27]. High-throughput formats enable screening of large compound collections.