Chemogenomics Libraries: The Engine for Next-Generation Phenotypic Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemogenomics libraries, cornerstone tools in modern chemical biology and drug discovery.

Chemogenomics Libraries: The Engine for Next-Generation Phenotypic Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemogenomics libraries, cornerstone tools in modern chemical biology and drug discovery. It explores the foundational concepts defining these annotated small-molecule collections and their role in systematic proteome interrogation. We delve into methodological advances in library design, screening, and diverse applications from target deconvolution to drug repurposing. The content also addresses critical limitations and optimization strategies for phenotypic screening, alongside rigorous frameworks for validating chemical probes and comparing library technologies. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how chemogenomics libraries are accelerating the translation of phenotypic observations into targeted therapeutic strategies.

Demystifying Chemogenomics Libraries: From Basic Concepts to Proteome-Wide Exploration

Defining Chemical Libraries, Chemical Probes, and Chemogenomic Sets

In modern drug discovery and chemical biology, the systematic use of well-characterized small molecules is fundamental for interrogating biological systems and validating therapeutic targets. This guide provides a detailed technical overview of three critical resources: chemical libraries, chemical probes, and chemogenomic sets. Framed within the broader context of global initiatives like Target 2035, which aims to find a pharmacological modulator for every human protein by 2035, understanding these tools is essential for researchers and drug development professionals [1] [2]. These compounds enable the functional annotation of the proteome, facilitate the deconvolution of complex phenotypes, and serve as starting points for therapeutic development, thereby accelerating translational research.

Definitions and Core Concepts

Chemical Libraries

A chemical library is a collection of stored chemicals, often comprising small organic molecules, used for high-throughput screening (HTS) to identify compounds that modulate a biological target or pathway. The contents of a library can be highly diverse or focused on particular protein families or structural motifs. The primary purpose of a chemical library is to provide a source of potential "hits" for drug discovery or chemical biology probes. Recent advances have led to the development of increasingly sophisticated libraries, including DNA-encoded libraries (DELs), where each compound is covalently tagged with a unique DNA barcode, enabling the screening of millions of compounds in a single tube [3]. The efficient synthesis of these libraries is a active area of research, with scheduling optimizations being formalized as a Flexible Job-Shop Scheduling Problem (FJSP) to minimize the total duration (makespan) of synthesis campaigns [4].

Chemical Probes

A chemical probe is a highly characterized, potent, and selective, cell-active small molecule that modulates the function of a single protein or a closely related protein family [5] [2] [6]. Unlike reagents for HTS, chemical probes are optimized tools for hypothesis-driven research to investigate the biological function and therapeutic potential of a specific target in cells and in vivo models.

The community, through consortia like the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) and the Chemical Probes Portal, has established strict minimum criteria for a compound to be designated a high-quality chemical probe [5] [1] [6]. These criteria are summarized in Table 1. A critical best practice is the use of a matched, structurally similar negative control compound that lacks activity against the intended target, helping to rule out off-target effects [1] [2]. The field is also continuously evolving to include new modalities, such as covalent probes [7] and degraders (e.g., PROTACs), which introduce additional considerations for their qualification and use [1].

Table 1: Minimum Quality Criteria for a High-Quality Chemical Probe

| Criterion | Requirement | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Potency | IC50/KD < 100 nM | Ensures strong binding to the target of interest. |

| Selectivity | >30-fold selectivity over related proteins (e.g., within the same family). | Confirms that observed phenotypes are due to on-target engagement. |

| Cell-Based Activity | Demonstrated on-target engagement at ≤1 μM (or ≤10 μM for shallow protein-protein interactions). | Verifies utility in a physiologically relevant cellular environment. |

| Cellular Toxicity Window | A reasonable window between the concentration for on-target effect and general cytotoxicity (unless cell death is the target-mediated outcome). | Distinguishes specific target modulation from nonspecific poisoning of the cell. |

Chemogenomic Sets

Chemogenomics is a strategy that utilizes annotated collections of small molecule tool compounds, known as chemogenomic (CG) sets, for the functional annotation of proteins in complex cellular systems and for target discovery and validation [1] [8] [9]. In contrast to the high selectivity required for chemical probes, the small molecule modulators (e.g., agonists, antagonists) in a CG set may not be exclusively selective for a single target. Instead, they are valuable because their target profiles are well-characterized [8]. By using a set of these compounds with overlapping target profiles, researchers can deconvolute the target responsible for a specific phenotype based on selectivity patterns [1]. This approach is a feasible and powerful interim solution for probing the ~3000 targets in the "druggable proteome" for which high-quality chemical probes do not yet exist [1] [8]. A major goal of the EUbOPEN consortium is to create a CG library covering about one-third of the druggable proteome [1] [8].

Table 2: Comparison of Chemical Tools and Their Applications

| Feature | Chemical Probe | Chemogenomic Compound | Chemical Library Compound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Target validation and functional studies; gold standard tool. | Phenotypic screening and target deconvolution. | Initial hit finding in target- or phenotypic-based screens. |

| Selectivity | High (>30-fold over related targets). | Moderate to low, but well-annotated. | Often unknown or unoptimized. |

| Characterization | Extensively profiled in biochemical, biophysical, and cellular assays. | Profiled against a panel of pharmacologically relevant targets. | Typically characterized only by purity/identity. |

| Availability of Controls | Always accompanied by a matched negative control. | Not necessarily. | No. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Developing a Chemical Probe: The Case of BET Bromodomains

The development of BET bromodomain inhibitors provides an excellent case study for the probe-to-drug pipeline [5].

- Target Identification & Validation: BRD4 was identified as a key epigenetic reader protein implicated in cancer [5].

- Hit Identification: The probe (+)-JQ1 was developed following molecular modeling of a triazolothienodiazepine scaffold against the BRD4 bromodomain. It demonstrated high potency (KD ~50-90 nM) [5].

- Hit-to-Probe Optimization: (+)-JQ1 was rigorously characterized and met the criteria for a chemical probe. However, its short half-life made it unsuitable for clinical progression [5].

- Probe-to-Drug Optimization: Inspired by (+)-JQ1, several clinical candidates were developed:

- I-BET762 (GSK525762): Identified via a phenotypic screen for ApoA1 upregulation. Optimization focused on improving potency, metabolic stability (by eliminating a labile amide), and physiochemical properties (lowering log P and MW) [5].

- OTX015: A structural analog of (+)-JQ1 with alterations that improved drug-likeness and oral bioavailability [5].

- CPI-0610: Constellation Pharmaceuticals used an aminoisoxazole fragment that mimicked the N-acetyllysine motif of histones, then constrained it with an azepine ring, a strategy directly inspired by the (+)-JQ1 scaffold [5].

Workflow for a Chemogenomic Phenotypic Screen

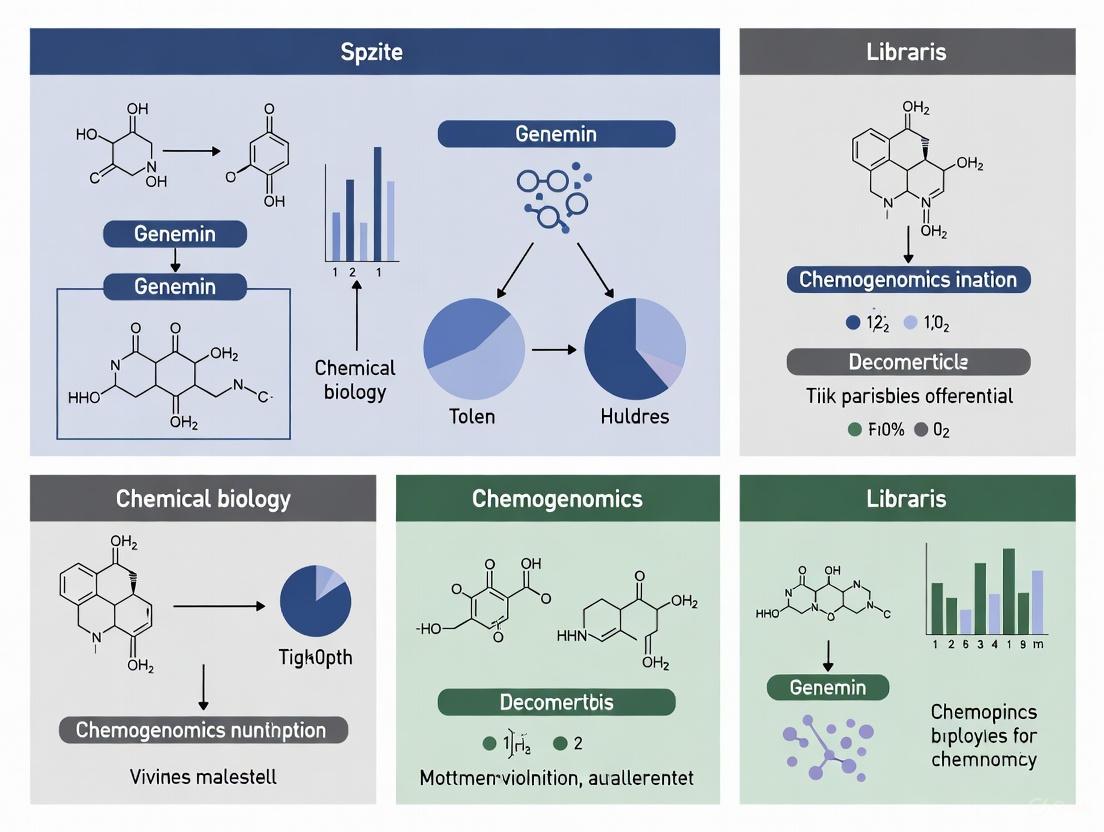

This workflow, illustrated in the diagram below, utilizes a CG set to identify targets involved in a biological process.

Workflow Description:

- Perform Phenotypic Screen: A CG library is screened against a disease-relevant cellular model (e.g., patient-derived cells) with a measurable phenotypic readout (e.g., cell viability, cytokine secretion, imaging) [1] [10].

- Identify Active Compounds: "Hit" compounds that significantly modulate the phenotype are identified.

- Annotate with Target Profiles: The known target annotations of the active hits are analyzed. The underlying hypothesis is that a specific protein target will be enriched in the target profiles of active compounds compared to inactive ones [1] [9].

- Generate Target Hypothesis: The overlapping target(s) of the active compounds form a testable hypothesis for the protein(s) driving the phenotype.

- Independent Validation: The hypothesized target is validated using an orthogonal tool, such as genetic knockdown (siRNA/CRISPR) or a highly selective chemical probe, if available [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms in Chemical Biology

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Example / Provider |

|---|---|---|

| Peer-Reviewed Chemical Probes | High-quality, expert-curated small molecules for target validation. | Chemical Probes Portal (www.chemicalprobes.org) [2] [6] |

| Chemogenomic (CG) Library | Collections of well-annotated compounds with known but not exclusive selectivity profiles. | EUbOPEN Consortium CG Library [1] [8] |

| DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) | Vast libraries (millions to billions) of small molecules tagged with DNA barcodes for ultra-high-throughput in vitro screening. | Commercially available and custom platforms [3] |

| Negative Control Compound | A structurally matched but inactive analog used to confirm on-target effects of a chemical probe. | Supplied with probes from the Chemical Probes Portal and EUbOPEN [1] [2] |

| Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) | A chemical proteomics technique using reactive covalent probes to monitor the functional state of enzymes in complex proteomes. | Used for target and off-target identification [7] |

| Public Data Repositories | Open-access databases for bioactivity data and compound information. | EUbOPEN data resources, PubChem, ChEMBL [1] |

The disciplined application of chemical libraries, chemical probes, and chemogenomic sets forms the bedrock of modern chemical biology and drug discovery. Adherence to community-established quality criteria for chemical probes is essential for generating reproducible and interpretable biological data. Meanwhile, the systematic, large-scale development of chemogenomic sets and chemical probes, as championed by Target 2035 and the EUbOPEN consortium, is strategically expanding the explorable druggable proteome. By understanding the distinct definitions, appropriate applications, and best practices associated with each of these chemical tools, researchers can more effectively decode complex biology and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

In the fields of chemical biology and drug discovery, high-quality chemical probes are indispensable tools for deciphering protein function and validating therapeutic targets. These small molecules allow researchers to modulate biological systems with temporal and dose-dependent control that is often impossible with genetic methods alone. The importance of these reagents has been magnified by initiatives to create comprehensive chemogenomics libraries, which aim to provide coverage across the human proteome. However, not all compounds labeled as "probes" meet the rigorous standards required for reliable research. The use of poor-quality chemical tools has led to erroneous conclusions and wasted resources throughout biomedical science. This guide details the established core criteria that define a high-quality chemical probe, providing researchers with a framework for their selection and use.

Defining a Chemical Probe

A chemical probe is a small molecule designed to selectively bind to and alter the function of a specific protein target [11]. Unlike simple inhibitors or tool compounds, chemical probes must be extensively characterized to demonstrate they modulate their intended target with high confidence. These reagents serve critical roles in basic research to understand protein function and in drug discovery for target validation [11] [12].

The fundamental distinction between a true chemical probe and a simple inhibitor lies in the depth of characterization. As one analysis notes, "Chemical probes are highly characterized small molecules that can be used to investigate the biology of specific proteins in biochemical and cellular assays as well as in more complex in vivo settings" [13]. This characterization encompasses multiple dimensions of compound behavior, from biochemical potency to cellular activity and selectivity.

The Essential Criteria for High-Quality Chemical Probes

Potency: The Foundation of Efficacy

Potency requirements for chemical probes are well-established and target-dependent. For biochemical assays, compounds should demonstrate an IC50 or Kd value of less than 100 nM [11] [13] [12]. In cellular environments, where permeability and efflux can reduce effective concentrations, probes should remain active at concentrations below 1 μM (EC50 < 1 μM) [11] [13] [12]. These potency thresholds help ensure that probes are effective at reasonable concentrations that minimize off-target effects.

Selectivity: Ensuring Specific Interpretation

Selectivity is perhaps the most challenging criterion to achieve. High-quality chemical probes should demonstrate at least 30-fold selectivity against closely related proteins within the same family [11] [13] [12]. For kinases, this means selectivity against other kinases in the kinome; for epigenetic targets, selectivity against related reader or writer domains.

The importance of comprehensive selectivity profiling cannot be overstated. As noted in one assessment, "Even the most selective chemical probe will become non-selective if used at a high concentration" [12]. This underscores the relationship between potency and selectivity—both must be considered together when evaluating probe quality.

Cellular Activity and Target Engagement

Demonstrating that a compound engages its intended target in a cellular context is essential. As Simon et al. noted, "Without methods to confirm that chemical probes directly and selectively engage their protein targets in living systems, however, it is difficult to attribute pharmacological effects to perturbation of the protein (or proteins) of interest versus other mechanisms" [11].

The four-pillar framework for cell-based target validation provides comprehensive guidance:

- Adequate cellular exposure of the probe

- Direct target engagement within the cellular environment

- Functional change in target activity

- Relevant phenotypic changes [11]

Structural Characterization and Availability

The chemical structure of a probe must be disclosed and the physical compound should be readily available to the research community [14]. Furthermore, the mechanism of action should be well-understood, ideally supported by structural data such as co-crystal structures showing the binding mode [11].

Avoiding Problematic Compounds

High-quality chemical probes must not be highly reactive, promiscuous molecules [13]. Compounds should be screened to exclude nuisance behaviors including:

- Non-specific electrophiles

- Redox cyclers

- Chelators

- Colloidal aggregators

- Compounds that interfere with assay readouts [13]

The Quantitative Landscape of Chemical Probe Quality

Table 1: Analysis of Public Database Compounds Against Minimum Probe Criteria

| Assessment Criteria | Number of Compounds | Percentage of Total Compounds | Proteins Covered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total compounds in public databases | >1.8 million | 100% | - |

| With biochemical activity <10 μM | 355,305 | 19.7% | - |

| With potency ≤100 nM | 189,736 | 10.5% | - |

| With selectivity data (tested against ≥2 targets) | 93,930 | 5.2% | - |

| Meeting minimal potency and selectivity criteria | 48,086 | 2.7% | 795 |

| Additionally meeting cellular activity criteria | 2,558 | 0.14% | 250 |

Data adapted from Probe Miner analysis [15].

The analysis in Table 1 reveals a critical challenge: despite millions of compounds in public databases, only a tiny fraction (0.14%) meet the minimum criteria for quality chemical probes. This scarcity is particularly concerning given that these compounds cover just 250 human proteins—approximately 1.2% of the human proteome [15]. This coverage gap represents a significant bottleneck in functional proteomics and target validation research.

Table 2: Recommended Controls for Chemical Probe Experiments

| Control Type | Description | Purpose | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matched Target-Inactive Control | Structurally similar compound lacking target activity | Distinguish target-specific effects from off-target or scaffold-specific effects | Use alongside active probe in parallel experiments |

| Orthogonal Probes | Chemically distinct probes targeting the same protein | Confirm phenotypes are target-specific rather than probe-specific | Employ at least two structurally unrelated probes |

| Concentration Range Testing | Using probes at recommended concentrations | Maintain selectivity while ensuring efficacy | Consult resources for target-specific concentration guidance |

Experimental Validation of Chemical Probes

The Probe Development Workflow

The development of high-quality chemical probes follows a rigorous, multi-stage process. The diagram below illustrates the key stages and decision points in this workflow:

Case Study: JAK3 Kinase Probe Development

The development of FM-381, a JAK3 reversible covalent inhibitor, exemplifies the rigorous application of these criteria [11]. Researchers first confirmed potency and selectivity in biochemical kinase activity assays, then validated the reversible covalent binding mechanism through co-crystal structures of JAK3 with the probe.

Critical to its validation was demonstrating intracellular target engagement using a BRET-based target engagement assay that assessed direct competitive binding in live cells [11]. These assays revealed potent apparent intracellular affinity for JAK3 (approximately 100 nM) and durable but reversible binding. Finally, the functional inhibitory effect was confirmed in cytokine-activated human T cells monitoring phosphorylation of various STAT proteins, establishing the cellular phenotype resulting from target engagement [11].

Implementation and Best Practices

The "Rule of Two" for Experimental Design

A recent systematic review of 662 publications employing chemical probes revealed concerning patterns of misuse [12]. Only 4% of publications used chemical probes within the recommended concentration range while also including both inactive control compounds and orthogonal probes [12].

To address this, researchers propose "the rule of two": every study should employ at least two chemical probes (either orthogonal target-engaging probes and/or a pair of a chemical probe and matched target-inactive compound) at recommended concentrations [12].

The Four-Pillar Framework for Target Validation

The relationship between exposure, engagement, and effect forms the foundation of proper probe use. The diagram below illustrates this critical pathway:

Table 3: Essential Resources for Chemical Probe Selection and Validation

| Resource Name | Type | Key Features | Best Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes Portal [6] | Expert-curated database | Star-rating system, expert comments, usage recommendations | Initial probe selection and best-practice guidance |

| Probe Miner [15] | Data-driven assessment | Statistical ranking of >1.8M compounds, objective metrics | Comparative analysis of multiple probe candidates |

| SGC Chemical Probes [11] | Open-access probe collection | Well-characterized probes, structural data, protocols | Access to high-quality, unencumbered chemical tools |

| Donated Chemical Probes [12] | Pharmaceutical company donations | Industry-developed probes, previously undisclosed compounds | Access to probes with industrial-grade characterization |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The field of chemical probe development continues to evolve with new modalities including PROTACs, molecular glues, and other degradation-based technologies expanding the "druggable" proteome [13]. These novel mechanisms present both opportunities and challenges for establishing quality criteria.

Initiatives like Target 2035, which aims to provide a high-quality chemical probe for every human protein by 2035, underscore the growing recognition of these tools as essential reagents for biological research [6]. Achieving this goal will require coordinated efforts across academic, pharmaceutical, and non-profit sectors, along with continued emphasis on the rigorous standards outlined in this guide.

High-quality chemical probes remain essential tools for advancing chemical biology and drug discovery. By adhering to the established criteria of potency, selectivity, cellular activity, and comprehensive characterization, researchers can ensure their experimental results derive from target-specific modulation rather than artifactual effects. The resources and frameworks presented here provide practical guidance for selecting and implementing these critical research tools with confidence. As the chemical biology community continues to expand the toolbox of high-quality probes, these standards will serve as the foundation for robust, reproducible biomedical research.

Twenty years after the publication of the first draft of the human genome, our knowledge of the human proteome remains profoundly fragmented [16]. While proteins serve as the primary executers of biological function and the main targets for therapeutic intervention, less than 5% of the human proteome has been successfully targeted for drug discovery [16]. This highlights a critical disconnect between our ability to obtain genetic information and our subsequent development of effective medicines. Approximately 35% of proteins in the human proteome remain uncharacterized, creating a significant "dark proteome" that may hold keys to understanding and treating human diseases [16].

To address this fundamental gap, the global biomedical community has launched ambitious open science initiatives. Target 2035 is an international federation of biomedical scientists from public and private sectors with the goal of creating pharmacological modulators for nearly all human proteins by 2035 [1] [16]. The EUbOPEN consortium represents a major implementing force toward this goal, specifically focused on generating openly available chemical tools and data to unlock previously inaccessible biology [1]. These initiatives recognize that high-quality pharmacological tools—including chemical probes and chemogenomic libraries—are essential for translating genomic discoveries into therapeutic advances.

Target 2035 - The Global Framework

Target 2035 is an international open science initiative that aims to generate and make freely available chemical or biological modulators for nearly all human proteins by the year 2035 [1] [17]. Initially conceived by scientists from the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) and pharmaceutical industry colleagues, this global federation now encompasses numerous research organizations worldwide [16]. The initiative's core strategy involves creating the technologies and research tools needed to interrogate the function and therapeutic potential of all human proteins, with particular emphasis on pharmacological modulators known to have transformative effects on studying protein biology [16].

The conceptual framework of Target 2035 is organized in distinct phases. The short-term priorities (Phase I) focus on establishing collaborative networks around four key pillars: (1) collecting and characterizing existing pharmacological modulators; (2) generating novel chemical probes for druggable proteins; (3) developing centralized data infrastructure; and (4) creating facilities for ligand discovery for undruggable targets [16]. Long-term priorities will build on these foundations to accelerate solutions for the dark proteome through more formalized organizational structures and scaled technologies [16].

EUbOPEN - The Implementation Engine

EUbOPEN (Enabling and Unlocking Biology in the OPEN) is a public-private partnership funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative with a total budget of €65.8 million [18] [19]. With 22 partners from academia and industry, EUbOPEN functions as a major implementing force for Target 2035 objectives [1]. The consortium's work is organized around four pillars of activity: chemogenomic library collection, chemical probe discovery and technology development, profiling of bioactive compounds in patient-derived disease assays, and collection/storage/dissemination of project-wide data and reagents [1] [20].

The consortium maintains a specific focus on challenging target classes that have historically been underrepresented in drug discovery efforts, particularly E3 ubiquitin ligases and solute carriers (SLCs) [1]. These protein families represent significant opportunities for therapeutic intervention but have proven difficult to target with conventional small molecules. By developing robust chemical tools for these understudied targets, EUbOPEN aims to illuminate new biological pathways and target validation opportunities [1].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Objectives of Target 2035 and EUbOPEN

| Initiative | Primary Objectives | Timeline | Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target 2035 | Create pharmacological modulators for nearly all human proteins | By 2035 | Entire human proteome (~20,000 proteins) |

| EUbOPEN | Assemble chemogenomic library of ~5,000 compounds | 5-year program (2020-2025) | ~1,000 proteins (1/3 of druggable genome) |

| EUbOPEN | Develop 100 high-quality chemical probes | 5-year program (2020-2025) | Focus on E3 ligases and solute carriers |

| EUbOPEN | Distribute chemical probes without restrictions | Ongoing | >6,000 samples distributed to date |

Core Scientific Methodologies

Chemical Probes: The Gold Standard

Chemical probes represent the highest quality tier of pharmacological tools for target validation and functional studies. The EUbOPEN consortium has established strict, peer-reviewed criteria for these molecules to ensure they generate reliable biological insights [1]. To qualify as a chemical probe, a compound must demonstrate potency measured in in vitro assays of less than 100 nM, selectivity of at least 30-fold over related proteins, and evidence of target engagement in cells at less than 1 μM (or 10 μM for shallow protein-protein interaction targets) [1]. Additionally, compounds must show a reasonable cellular toxicity window unless cell death is target-mediated [1].

EUbOPEN's chemical probe development includes a unique Donated Chemical Probes (DCP) project where probes developed by academics and/or industry undergo peer review by two independent committees before being made available to researchers worldwide without restrictions [1]. This initiative aims to collate 50 high-quality chemical probes from the community, complementing the 50 novel probes being developed within the consortium itself [1]. All probes are distributed with structurally similar inactive negative control compounds—a critical component for proper experimental design that allows researchers to distinguish target-specific effects from off-target activities [1].

Chemogenomic Libraries: Expanding the Targetable Landscape

The development of highly selective chemical probes is both costly and challenging, making it impractical to create such tools for every protein target in the near term [1]. To address this limitation, EUbOPEN has embraced a chemogenomics strategy that utilizes well-annotated compound sets with defined but not exclusively selective target profiles [1] [8].

Chemogenomic compounds contrast with chemical probes in that they may bind to multiple targets but are still valuable due to their well-characterized target profiles [1]. When used as overlapping sets, these tools enable target deconvolution through selectivity patterns—the specific biological target responsible for an observed phenotype can be identified by comparing effects across multiple compounds with shared but varying target affinities [16].

The EUbOPEN consortium is assembling a chemogenomic library comprising approximately 5,000 compounds covering roughly 1,000 different proteins—approximately one-third of the currently recognized druggable proteome [18] [19]. This collection is organized into subsets targeting major protein families including protein kinases, membrane proteins, and epigenetic modulators [8]. The library construction leverages hundreds of thousands of bioactive compounds generated by previous medicinal chemistry efforts in both industrial and academic sectors [1].

Experimental Workflows and Validation Pipelines

The development and qualification of chemical tools follows rigorous experimental workflows that integrate multiple validation steps. The process begins with target selection, focusing on understudied proteins with compelling genetic associations to disease [16]. For chemical probe development, this is followed by compound screening, hit validation, and extensive characterization through biochemical and cellular assays [1].

Diagram 1: Chemical Probe Development Workflow

For chemogenomic libraries, EUbOPEN has established family-specific criteria developed with external expert committees that consider available well-characterized compounds, screening possibilities, ligandability of different targets, and the ability to collate multiple chemotypes per target [1] [8]. The consortium has implemented several selectivity panels for different target families to annotate compounds beyond what is available in existing literature [1].

A critical innovation in EUbOPEN's approach is the extensive use of patient-derived disease assays for tool compound validation [1]. Diseases of particular focus include inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, and neurodegeneration [1]. This strategy ensures that chemical tools are validated in biologically relevant systems that more closely mimic human disease states compared to conventional cell lines.

Technological Innovations and Target Class Expansion

Embracing New Modalities

The EUbOPEN consortium has actively expanded its scope beyond traditional small molecule inhibitors to include emerging therapeutic modalities that significantly increase the druggable proteome. PROTACs (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras) and molecular glues represent particularly promising approaches that enable targeted protein degradation by hijacking the ubiquitin-proteasome system [1]. These proximity-inducing small molecules offer unique properties, including the ability to target proteins that lack conventional binding pockets and the potential for enhanced selectivity through cooperative binding [1].

The development of these new modalities has created demand for ligands targeting E3 ubiquitin ligases, which serve as the recognition component in degradation systems. EUbOPEN has consequently prioritized the discovery of E3 ligase handles—small molecule ligands that provide attachment points for degrader design [1]. The first new E3 ligands developed through this initiative have now been published, demonstrating the consortium's progress in this challenging target space [1].

Focus on Understudied Target Families

EUbOPEN maintains particular emphasis on protein families that have historically received limited attention despite their therapeutic potential. Solute carriers (SLCs) represent the second largest membrane protein family after GPCRs but remain dramatically understudied as drug targets [16]. Similarly, E3 ubiquitin ligases, which number over 600 in the human genome, have been targeted by only a handful of high-quality chemical tools [1].

The consortium's targeted approach to these challenging protein families involves developing robust assay systems alongside chemical tool development. For SLCs, this includes creating thousands of tailored cell lines and establishing protocols for functional characterization [16]. For E3 ligases, the focus includes developing assays that measure not only direct binding but also functional consequences on substrate ubiquitination and degradation [1].

The ultimate impact of Target 2035 and EUbOPEN initiatives depends on widespread accessibility of the research reagents and data generated through these programs. The consortium has established comprehensive distribution systems to ensure broad availability of these resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Type | Description | Key Applications | Access Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | Cell-active, potent (<100 nM), and selective (>30-fold) small molecules | Target validation, mechanism of action studies, phenotypic screening | EUbOPEN website: chemical probes portal |

| Negative Controls | Structurally similar but inactive compounds | Distinguishing target-specific effects from off-target activities | Provided with each chemical probe |

| Chemogenomic Library | ~5,000 compounds with overlapping selectivity profiles covering 1,000 proteins | Target deconvolution, polypharmacology studies, pathway analysis | Available as full sets or target-family subsets |

| Annotated Datasets | Biochemical, cellular, and selectivity profiling data | Cheminformatics, machine learning, structure-activity relationships | Public repositories and EUbOPEN data portal |

| Patient-Derived Assay Protocols | Standardized methods using primary cells from relevant diseases | Biologically relevant compound validation, translational research | EUbOPEN dissemination materials |

Data Management and Open Science Principles

A foundational principle of both Target 2035 and EUbOPEN is commitment to open science through immediate public release of all data, tools, and reagents without intellectual property restrictions [1] [16]. This approach aims to accelerate biomedical research by eliminating traditional barriers to information flow and resource sharing.

EUbOPEN has established robust infrastructure for data collection, storage, and dissemination that includes deposition in existing public repositories alongside a project-specific data resource for exploring consortium outputs [1]. The consortium works closely with cheminformatics and database providers to ensure long-term sustainability and accessibility of the chemical tools and associated data [16].

The open science model extends to collaborative structures as well. Target 2035 hosts monthly webinars that are freely accessible to the global research community, featuring topics ranging from covalent ligand screening to AI methods for ligand discovery [16]. These forums facilitate knowledge exchange and serve as nucleation points for new collaborations that advance the initiative's core mission.

Target 2035 and EUbOPEN represent complementary, large-scale efforts to address critical gaps in our understanding of human biology and expand the universe of druggable targets. Through systematic development and characterization of chemical probes and chemogenomic libraries, these initiatives provide the research community with high-quality tools to explore protein function in health and disease.

The ongoing work faces significant challenges, particularly in expanding the druggable proteome to include protein classes that have historically resisted conventional small-molecule targeting. Success will require continued technological innovation in areas such as covalent ligand discovery, targeted protein degradation, and structure-based drug design. Additionally, maintaining the open science principles that form the foundation of these initiatives will be essential for maximizing their impact across the global research community.

As these efforts progress, they will increasingly rely on contributions from distributed networks of researchers across public and private sectors. The frameworks established by Target 2035 and EUbOPEN provide scalable models for organizing these collaborative efforts while ensuring that resulting tools and knowledge remain freely available to accelerate the development of new medicines for human disease.

In the landscape of modern drug discovery, the strategic selection of compound libraries fundamentally shapes the trajectory and outcome of screening campaigns. While standard compound collections have traditionally been valued for their sheer size and chemical diversity, a specialized class of libraries has emerged to meet the demands of target-aware screening environments: chemogenomic libraries. These are not merely collections of chemicals, but highly annotated knowledge bases where each compound is associated with rich biological information regarding its known or predicted interactions with specific protein targets, pathways, and cellular processes [21] [22] [23].

The core distinction lies in their foundational purpose. Standard libraries aim to broadly sample chemical space to find any active compound against a biological assay. In contrast, chemogenomic libraries are designed for mechanism-driven discovery, where a hit from such a library immediately provides a testable hypothesis about the biological target or pathway involved in the observed phenotype [22] [24]. This transforms the discovery process from a black box into a knowledge-rich endeavor, accelerating the critical step from phenotype to target identification. This whitepaper delineates the conceptual, structural, and practical advantages of chemogenomic libraries, framing them as indispensable tools for contemporary chemical biology research.

Defining the Libraries: Core Concepts and Compositions

Standard Compound Collections

Standard compound collections, often used for High-Throughput Screening (HTS), are typically large libraries—sometimes containing millions of compounds—designed to maximize chemical diversity [25] [26]. Their primary goal is to explore vast chemical space to identify initial "hit" compounds that modulate a biological target or phenotype. The selection criteria for these libraries have evolved from quantity-focused to quality-aware, often incorporating filters for drug-likeness (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five), the removal of compounds with reactive or toxic motifs, and considerations of synthetic tractability [26]. The value of a standard library is measured by its breadth and its ability to surprise, potentially uncovering novel chemistry against unanticipated biology.

Chemogenomic Libraries

Chemogenomic libraries, sometimes termed annotated chemical libraries, are collections of well-defined, often well-characterized pharmacological agents [22] [27]. They are inherently knowledge-based tools. The defining feature is the systematic annotation of each compound with information on its primary molecular target(s), its potency (e.g., IC50, Ki values), its selectivity profile, and its known mechanism of action [21] [23]. These libraries are often focused and target-rich, covering key therapeutically relevant protein families such as kinases, GPCRs, ion channels, and epigenetic regulators [22] [27].

Table 1: Core Differentiators Between Standard and Chemogenomic Libraries

| Feature | Standard Compound Collections | Chemogenomic Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Identify novel hits via broad exploration | Deconvolute mechanism and validate targets |

| Design Principle | Maximize chemical diversity and structural novelty | Maximize target coverage and biological relevance |

| Library Size | Large (hundreds of thousands to millions) | Focused (hundreds to a few thousand) |

| Key Metadata | Chemical structure, physicochemical properties | Annotated targets, potency (IC50/Ki), selectivity, mechanism |

| Ideal Application | Initial hit discovery in target-agnostic screens | Phenotypic screening, target identification, drug repurposing |

The composition of a high-quality chemogenomic library is a deliberate exercise in systems pharmacology. As detailed in one development study, such a library is constructed by integrating drug-target-pathway-disease relationships from databases like ChEMBL, KEGG, and Gene Ontology, and can be further enriched with data from morphological profiling assays like Cell Painting [27]. This creates a powerful network where chemical perturbations can be linked to specific nodes within biological systems.

The Annotated Advantage in Practice: Key Applications

The rich annotation of chemogenomic libraries confers several distinct advantages in real-world research settings.

Accelerated Target Deconvolution in Phenotypic Screening

Phenotypic screening has experienced a resurgence as a strategy for discovering first-in-class therapies. However, a major bottleneck is the subsequent target identification phase, which can be protracted and laborious. Screening a chemogenomic library directly addresses this challenge. A hit from such a screen immediately suggests that the annotated target(s) of the active compound are involved in the phenotypic perturbation, providing a direct and testable hypothesis [22] [24]. This can expedite the conversion of a phenotypic screening project into a target-based drug discovery campaign.

Enabling Selective Polypharmacology

Many complex diseases, such as cancer and neurological disorders, are driven by aberrations in multiple signaling pathways. Targeting a single protein is often insufficient. Chemogenomic libraries, especially when used with rational design, can help identify compounds with a desired polypharmacology profile. For instance, in a study against glioblastoma (GBM), researchers created a focused library by virtually screening compounds against multiple GBM-specific targets identified from genomic data. This led to the discovery of a compound, IPR-2025, that engaged multiple targets and potently inhibited GBM cell viability without affecting healthy cells, demonstrating the power of this approach for incurable diseases [28].

Drug Repurposing and Predictive Toxicology

Because chemogenomic libraries contain many approved drugs and well-characterized tool compounds, they are ideal for drug repurposing efforts. A newly discovered activity in a phenotypic screen can immediately point to a new therapeutic indication for an existing drug [22]. Furthermore, these libraries can be used for predictive toxicology; if a compound with a known toxicity profile shows activity in a screen, it can alert researchers to potential off-target effects early in the development of new chemical series [22].

Experimental Workflow for Chemogenomic Screening

The application of a chemogenomic library follows a structured workflow that integrates computational and experimental biology. The following diagram and protocol outline a typical campaign for phenotypic screening and target identification.

Protocol: Phenotypic Screening and Mechanism Deconvolution

This protocol is adapted from established chemogenomic screening practices [22] [27] [28].

Step 1: Library Curation and Assay Development

- Library Selection: Procure or assemble a chemogenomic library with comprehensive annotations. Commercially available options exist, or custom libraries can be built from databases like ChEMBL [27] [25].

- Assay Design: Develop a robust, disease-relevant phenotypic assay. The trend is moving towards more physiologically complex 3D models (e.g., spheroids, organoids) over traditional 2D monolayers to better capture disease biology [28]. Assays should be scaled for high-throughput or high-content screening.

Step 2: High-Throughput Phenotypic Screening

- Screening Execution: Screen the chemogenomic library against the phenotypic assay. Technologies such as high-content imaging (e.g., Cell Painting) can capture a wealth of multiparametric data on cellular morphology [27].

- Hit Identification: Analyze screening data to identify "hit" compounds that robustly and reproducibly modulate the phenotype. Statistical rigor is essential to minimize false positives [22].

Step 3: Data Integration and Hypothesis Generation

- Annotation Mining: For each confirmed hit, interrogate its pre-existing annotations. This includes its primary molecular target, its potency, its selectivity profile across related targets, and the biological pathway(s) its target is involved in [21] [23].

- Network Analysis: Map the targets of multiple hit compounds onto protein-protein interaction or pathway networks. Overrepresented targets or pathways provide a strong, systems-level mechanistic hypothesis for the observed phenotype [27] [28].

Step 4: Hypothesis Validation

- Target Engagement assays: Use techniques like Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) or thermal proteome profiling (TPP) to confirm direct physical binding between the hit compound and its proposed target(s) in a cellular context [28].

- Genetic Validation: Employ genetic tools such as CRISPR-Cas9 knockout or RNA interference (RNAi) to silence the proposed target gene. Phenocopying of the drug effect by genetic perturbation provides strong evidence for the target's role [22].

- Functional Studies: Conduct downstream functional experiments to delineate the causal chain of events from target engagement to final phenotypic outcome.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successfully implementing a chemogenomic strategy requires a suite of specialized reagents, databases, and computational tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Chemogenomics

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Annotated Chemogenomic Library | Chemical Collection | Core set of pharmacologically active compounds with known target annotations for screening. |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity Database | Public repository of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used for library building and annotation [27]. |

| Cell Painting Assay | Phenotypic Profiling | High-content imaging assay that uses fluorescent dyes to reveal compound-induced morphological changes, creating a rich data source for network integration [27]. |

| CETSA / Thermal Proteome Profiling | Target Engagement Assay | Confirms direct physical binding of a compound to its proposed protein target(s) within a complex cellular lysate or live cells [28]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 / RNAi Tools | Genetic Toolset | Validates the biological relevance of a putative target by genetically perturbing its expression and assessing the impact on the phenotype [22]. |

| Neo4j or similar Graph Database | Data Integration Platform | Enables the construction of a systems pharmacology network linking compounds, targets, pathways, and diseases, facilitating knowledge discovery [27]. |

The ascent of chemogenomic libraries marks a strategic evolution in chemical biology, from a focus on sheer chemical abundance to a premium on curated biological knowledge. The "annotated advantage" is clear: these libraries provide a direct, interpretable link between chemical structure, biological target, and phenotypic outcome. This transforms the discovery process, dramatically accelerating target deconvolution, enabling the rational pursuit of polypharmacology, and opening new avenues for drug repurposing.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic integration of chemogenomic libraries into screening portfolios is no longer a niche option but a critical component of a modern, efficient, and mechanistic discovery engine. By starting with a knowledge-rich library, the path from an initial phenotypic observation to a validated therapeutic hypothesis becomes shorter, more informed, and ultimately, more likely to succeed in delivering new medicines for patients. As these annotated resources continue to grow in scope and quality, they will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of innovative research in chemical biology and drug discovery.

Building and Applying Chemogenomics Libraries: From Design to Deconvolution

Strategies for Assembling a Diverse and Informative Library

In the fields of chemical biology and chemogenomics, the strategic assembly of diverse and informative compound libraries is a critical foundation for driving discovery and innovation. These libraries are not mere collections of molecules; they are sophisticated tools designed to systematically probe biological systems, validate therapeutic targets, and unlock new areas of the druggable genome. The global Target 2035 initiative underscores this mission, aiming to develop pharmacological modulators for most human proteins by the year 2035 [1]. This ambitious goal relies heavily on the creation of high-quality, well-annotated chemical collections, which serve as the essential starting material for both academic research and pharmaceutical development. The evolution of the chemical biology platform has been instrumental in transitioning from traditional, often serendipitous, discovery to a more rational, mechanism-based approach to understanding and influencing living systems [29]. This guide details the core strategies, methodologies, and resources for building libraries that are both comprehensive in scope and rich in biological information, thereby empowering researchers to advance the frontiers of precision medicine.

Foundational Concepts: Chemical Probes and Chemogenomic Libraries

A strategic approach to library assembly requires a clear understanding of the different types of tools and their intended applications. The two primary categories of compounds are chemical probes and chemogenomic sets, each with distinct characteristics and roles in research.

Chemical Probes: The Gold Standard for Target Validation

Chemical probes are small molecules that represent the highest standard for modulating protein function in a biological context. They are characterized by:

- High Potency: Typically demonstrate half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) or effective concentration (EC₅₀) values below 100 nM in in vitro assays [1].

- Exceptional Selectivity: Exhibit a selectivity of at least 30-fold over related proteins to ensure that observed phenotypes can be confidently attributed to the intended target [1].

- Cellular Activity: Provide evidence of target engagement in cells at concentrations of less than 1 µM (or 10 µM for challenging targets like protein-protein interactions) [1].

- Availability of Controls: Are ideally accompanied by structurally similar but inactive control compounds to account for off-target effects in experimental design [30].

Initiatives like EUbOPEN and the Donated Chemical Probes (DCP) project are dedicated to the development, peer-review, and distribution of these high-quality tools, making them freely available to the global research community [1].

Chemogenomic (CG) Libraries: Practical Coverage of the Druggable Proteome

While chemical probes are ideal, their development is resource-intensive. Chemogenomic compounds offer a powerful and practical complementary strategy.

- Defining Characteristics: CG compounds may bind to multiple targets within a protein family but are valuable due to their well-characterized activity profiles [1].

- Utility in Deconvolution: When used as overlapping sets, these compounds allow researchers to identify the target responsible for a phenotype by analyzing selectivity patterns across the library [1].

- Scope of Coverage: Public repositories contain hundreds of thousands of characterized compounds, enabling the assembly of CG libraries that can cover a significant portion of the druggable proteome. For instance, the EUbOPEN project includes a CG library covering approximately one-third of the druggable genome [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Chemical Tools

| Feature | Chemical Probe | Chemogenomic Compound |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Highly specific target modulation and validation | Broad coverage of a target family; target deconvolution |

| Potency | Typically < 100 nM | Variable, but well-characterized |

| Selectivity | ≥ 30-fold over related targets | Binds multiple targets with a known profile |

| Best Use Case | Confidently attributing a cellular phenotype to a single target | Systematically exploring the druggability of a pathway or family |

Strategic Approaches for Library Assembly and Curation

Building a high-quality library requires a multi-faceted strategy that goes beyond simple compound acquisition. It involves careful design, rigorous annotation, and a commitment to accessibility.

Defining Diversity: Coverage and Structural Variety

In chemical biology, a "diverse" library encompasses several dimensions:

- Target Family Coverage: The library should include compounds targeting a wide range of protein families, such as kinases, GPCRs, ion channels, E3 ubiquitin ligases, and solute carriers (SLCs) [1] [29].

- Modality Diversity: Modern libraries are expanding beyond traditional inhibitors to include new modalities such as PROTACs, molecular glues, covalent binders, and agonists/antagonists, thereby increasing the scope of the druggable proteome [1].

- Chemical Space: The library should encompass a broad range of chemotypes and scaffolds to increase the probability of finding hits against novel targets and to provide multiple starting points for lead optimization.

Implementing Rigorous Annotation and Curation

The value of a library is directly proportional to the quality and depth of its annotation. Key steps include:

- Establishing Criteria: Consortia like EUbOPEN define family-specific criteria for compound inclusion, considering ligandability, availability of chemotypes, and screening possibilities [1].

- Comprehensive Profiling: Compounds should be annotated with data from a suite of biochemical and cell-based assays. This includes potency, selectivity, cellular activity, and absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) profiles [1] [29].

- Leveraging Public Data: Assembly efforts can integrate data from major public bioactivity databases such as ChEMBL, Guide to Pharmacology (IUPHAR/BPS), and BindingDB [30].

- Identifying Nuisance Compounds: An essential curation step is the identification and flagging of compounds with pan-assay interference properties (PAINS) and other undesirable behaviors to prevent wasted efforts on false positives. Resources like the Probes & Drugs (P&D) portal provide updated nuisance compound sets [30].

Fostering Open Science and Accessibility

The impact of a library is maximized when it is accessible.

- Open-Access Models: Initiatives like EUbOPEN, the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC), and EU-OPENSCREEN operate on pre-competitive, open-science principles, making compounds, data, and protocols freely available [1] [31].

- Distribution Mechanisms: These consortia provide physical compounds upon request, often with detailed information sheets recommending use, and deposit all data in public repositories to ensure transparency and reproducibility [1].

Experimental Protocols for Library Evaluation and Validation

Before a library can be deployed in a screening campaign, its integrity and the performance of its constituent compounds must be rigorously validated.

Protocol: Interrogation of Bioassay Integrity Using Nuisance Compound Sets

This protocol uses a defined set of nuisance compounds to validate assay systems and identify potential interference patterns early in the screening process [30].

- Source a Nuisance Compound Set: Obtain a carefully compiled set, such as the Collection of Useful Nuisance Compounds (CONS) [30].

- Prepare Assay-Ready Plates: Format the nuisance compounds into microplates, ideally alongside DMSO controls and known positive controls.

- Run the Validation Assay: Test the nuisance compound plate in the specific biochemical or phenotypic assay to be used for the primary screen.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- Identify compounds that show significant activity, which may indicate assay interference rather than true target engagement.

- Categorize the type of interference (e.g., fluorescence quenching, luciferase inhibition, protein aggregation) based on the known properties of the nuisance compounds.

- Use this information to refine the assay protocol or to establish filters for hit selection in the subsequent primary screen.

Protocol: Cellular Target Engagement and Selectivity Profiling

For chemical probes and lead compounds, confirming cellular activity and selectivity is paramount.

- Cellular Potency Assay: Develop a cell-based assay that reports on the functional modulation of the target (e.g., a reporter gene assay, quantification of a downstream phosphoprotein, or a phenotypic readout) to determine the EC₅₀ of the compound in a relevant cellular context [1] [29].

- Broad-Spectrum Selectivity Profiling:

- Chemical Proteomics: Use affinity-based protein profiling (AfBPP) or photoaffinity labeling to pull down protein targets from cell lysates directly. A notable example is the chemical proteomics landscape mapping of 1,000 kinase inhibitors to characterize their full target space [30].

- Panel Screening: Test the compound against a panel of related enzymes or receptors (e.g., a kinase panel) to generate a comprehensive selectivity profile [1].

- Validation with Control Compounds: Always compare the activity profile of the active compound with its matched inactive control (for probes) or a set of compounds with overlapping selectivity (for CG sets) to deconvolute on-target from off-target effects [1] [30].

Diagram 1: Compound Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful library construction and screening depend on access to a suite of essential reagents and platforms. The following table details key resources available to the scientific community.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Resources

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Description | Example / Provider |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Chemical Probes | Potent, selective, cell-active small molecules for definitive target validation. | Chemical Probes.org; SGC Donated Probes; opnMe portal [30]. |

| Chemogenomic (CG) Compound Sets | Well-annotated sets of compounds with overlapping target profiles for deconvolution. | EUbOPEN CG Library [1]. |

| Nuisance Compound Libraries | Sets of known pan-assay interference compounds for assay validation and quality control. | A Collection of Useful Nuisance Compounds (CONS) [30]. |

| Annotated Bioactive Libraries | Pre-assembled libraries of bioactive compounds with associated mechanistic data. | CZ-OPENSCREEN Bioactive Library; Commercial sets (e.g., Cayman, SelleckChem) [30]. |

| Open-Access Research Infrastructure | Provides access to high-throughput screening, chemoproteomics, and medicinal chemistry expertise. | EU-OPENSCREEN ERIC [31]. |

| Public Bioactivity Databases | Repositories of bioactivity data for compound annotation, selection, and prioritization. | ChEMBL; Guide to Pharmacology; BindingDB; Probes & Drugs Portal [30]. |

Tracking the outputs of major library-generation initiatives provides a quantitative measure of progress toward covering the druggable genome.

Table 3: Quantitative Outputs from Major Initiatives (Representative Data)

| Initiative / Resource | Key Metric | Reported Output | Source / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| EUbOPEN Consortium | Chemogenomic Library Coverage | ~1/3 of the druggable proteome | [1] |

| EUbOPEN Consortium | Chemical Probes (Aim) | 100 high-quality chemical probes (by 2025) | [1] |

| Probes & Drugs Portal | High-Quality Chemical Probes (Cataloged) | 875 compounds for 637 primary targets (as of 2025) | [30] |

| Probes & Drugs Portal | Freely Available Probes | 213 compounds available at no cost | [30] |

| Public Repositories (Pre-2020) | Annotated Bioactive Compounds | 566,735 compounds with activity ≤10 µM | [1] |

Diagram 2: Library Strategy for Target 2035

The systematic assembly of diverse and informative libraries is a cornerstone of modern chemical biology and drug discovery. By integrating clear strategies—distinguishing between chemical probes and chemogenomic sets, implementing rigorous annotation and curation protocols, and leveraging open-science resources—researchers can construct powerful toolkits for biological exploration. These strategies, supported by the experimental protocols and reagent solutions outlined herein, directly contribute to the broader thesis that understanding biological function and advancing therapeutic innovation are fundamentally dependent on high-quality chemical starting points. As the field continues to evolve with new modalities and technologies, the principles of diversity, quality, and accessibility will remain paramount in the collective effort to illuminate the druggable genome and achieve the goals of precision medicine.

In modern chemical biology and chemogenomics, the paradigm of drug discovery has shifted from a "one drug–one target" approach to a systems-level understanding of complex interactions between small molecules and biological systems [32]. Researchers now recognize that many complex diseases are associated with multiple targets and pathways, requiring therapeutic strategies that account for this complexity [33]. The integration of diverse data types—including bioactivity signatures, pathway information, and morphological profiles—has emerged as a crucial methodology for elucidating compound mechanisms of action (MOA), predicting polypharmacological effects, and identifying repurposing opportunities [33] [32]. This technical guide provides an in-depth framework for integrating these multidimensional data sources within chemogenomics library research, enabling more effective and predictive drug discovery.

Data Types and Their Significance

Bioactivity Data

Bioactivity signatures encode the physicochemical and structural properties of small molecules into numerical descriptors, forming the basis for chemical comparisons and search algorithms [34]. The Chemical Checker (CC) provides a comprehensive resource of bioactivity signatures for over 1 million small molecules, organized into five levels of biological complexity: from chemical properties to clinical outcomes [34]. These signatures dynamically evolve with new data and processing strategies, moving beyond static chemical descriptors to include biological effects such as induced gene expression changes [34]. Deep neural networks can leverage experimentally determined bioactivity data to infer missing bioactivity signatures for compounds of interest, extending annotations to a larger chemical landscape [34].

Pathway Information

Pathway data bridges the gap between molecular targets and cellular function by linking chemical-protein interactions to biological pathways and Gene Ontology (GO) annotations [33]. Tools like QuartataWeb enable researchers to map interactions between chemicals/drugs and human proteins to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways, completing the bridge from chemicals to function via protein targets and cellular pathways [33]. This approach allows for multi-drug, multi-target, multi-pathway analyses, facilitating the design of polypharmacological treatments for complex diseases [33].

Morphological Profiling

Morphological profiling with assays such as Cell Painting captures phenotypic changes across various cellular compartments, enabling rapid prediction of compound bioactivity and mechanism of action [35]. This method uses high-content imaging to extract quantitative profiles that reflect the morphological state of cells in response to chemical perturbations. Recent resources provide comprehensive morphological profiling data using carefully curated compound libraries, with extensive optimization to achieve high data quality and reproducibility across different imaging sites [35]. These profiles can be correlated with various biological activities, including cellular toxicity and specific mechanisms of action.

Table 1: Key Data Types in Integrated Chemogenomics

| Data Type | Description | Key Resources | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioactivity Signatures | Numerical descriptors encoding physicochemical/biological properties | Chemical Checker [34] | Compound comparison, similarity search, target prediction |

| Pathway Information | Annotated biological pathways and gene ontology terms | QuartataWeb, KEGG [33] | Polypharmacology, drug repurposing, side-effect prediction |

| Morphological Profiles | Quantitative features from cellular imaging | Cell Painting, EU-OPENSCREEN [35] | MOA prediction, phenotypic screening, toxicity assessment |

Computational Frameworks for Data Integration

Chemical Checker Protocol

The Chemical Checker implements a standardized protocol for generating and integrating bioactivity signatures, typically completed in under 9 hours using graphics processing unit (GPU) computing [34]. The protocol involves several key steps: (1) data curation and preprocessing from multiple bioactivity sources, (2) organization of data into five levels of increasing biological complexity, (3) application of deep neural networks to infer missing bioactivity data, and (4) generation of unified bioactivity signatures for compound analysis [34]. This approach enables researchers to leverage diverse bioactivity data with current knowledge, creating customized bioactivity spaces that extend beyond the original Chemical Checker annotations.

Pathopticon Framework

Pathopticon represents a network-based statistical approach that integrates pharmacogenomics and cheminformatics for cell type-guided drug discovery [32]. This framework consists of two main components: the Quantile-based Instance Z-score Consensus (QUIZ-C) method for building cell type-specific gene-drug perturbation networks from LINCS-CMap data, and the Pathophenotypic Congruity Score (PACOS) for measuring agreement between input and perturbagen signatures within a global network of diverse disease phenotypes [32]. The method combines these scores with pharmacological activity data from ChEMBL to prioritize drugs in a cell type-dependent manner, outperforming solely cheminformatic measures and state-of-the-art network and deep learning-based methods [32].

QuartataWeb Server

QuartataWeb is a user-friendly server designed for polypharmacological and chemogenomics analyses, providing both experimentally verified and computationally predicted interactions between chemicals and human proteins [33]. The server uses a probabilistic matrix factorization algorithm with optimized parameters to predict new chemical-target interactions (CTIs) in the extended space of more than 300,000 chemicals and 9,000 human proteins [33]. It supports three types of queries: (I) lists of chemicals or targets for chemogenomics-like screening, (II) pairs of chemicals for combination therapy analysis, and (III) single chemicals or targets for characterization [33]. Outputs are linked to KEGG pathways and GO annotations to predict affected pathways, functions, and processes.

Diagram 1: Data Integration Workflow for Chemical Biology

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Chemical Checker Bioactivity Signature Generation

Objective: Generate novel bioactivity spaces and signatures by leveraging diverse bioactivity data.

Materials:

- Chemical Checker software package (available at https://gitlabsbnb.irbbarcelona.org/packages/chemical_checker)

- Bioactivity data from public repositories or in-house sources

- Computational environment with GPU capability

Procedure:

- Data Curation: Collect and preprocess bioactivity data using the predefined CC data curation pipeline. This includes standardization of compound identifiers, normalization of bioactivity values, and quality control.

- Signature Calculation: For each compound, compute bioactivity signatures across five levels of biological complexity: chemical properties, targets, networks, cells, and clinical outcomes [34].

- Data Integration: Apply deep neural networks to infer missing bioactivity signatures, extending coverage to uncharacterized compounds [34].

- Validation: Compare generated signatures against known bioactivity patterns to ensure biological relevance.

Expected Results: Unified bioactivity signatures that enable comparison of compounds across multiple biological levels.

Cell Type-Specific Gene-Drug Network Construction

Objective: Build cell type-specific gene-drug perturbation networks from LINCS-CMap data using the QUIZ-C method [32].

Materials:

- LINCS-CMap Level 4 plate-normalized expression values (ZSPC values)

- Computational environment with R or Python and necessary packages

- Pathopticon algorithm (available at https://github.com/r-duh/Pathopticon)

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Gather Level 4 expression values for all perturbagen instances for each gene.

- Z-score Calculation: For each gene (g) perturbed by instance (i) in cell line (c), calculate the gene-centric z-score: [ {pZS}{g,i}^{c} = \frac{{ZS}{g,i}^{c} - \langle {ZS}{g}^{c}\rangle}{{\sigma}{{ZS}{g}^{c}}} ] where (\langle {ZS}{g}^{c}\rangle) and ({\sigma}{{ZS}{g}^{c}}) are the mean and standard deviation of ZS scores over all perturbagen instances for the given gene and cell type [32].

- Data Aggregation: Aggregate z-score values at the perturbagen level to obtain sets of gene-centric z-scores for each perturbagen.

- Significance Thresholding: Identify perturbagen-gene pairs with significant and consistent effects using predetermined z-score thresholds and consensus criteria.

Expected Results: Cell type-specific gene-perturbagen networks that reflect the biological uniqueness of different cell lines.

Morphological Profiling with Cell Painting

Objective: Generate reproducible morphological profiles for compound mechanism of action prediction.

Materials:

- Curated compound library (e.g., EU-OPENSCREEN Bioactive compounds)

- Appropriate cell lines (e.g., Hep G2, U2 OS)

- High-throughput confocal microscopes

- Cell Painting assay reagents

Procedure:

- Assay Optimization: Perform extensive optimization across imaging sites to ensure high data quality and reproducibility [35].

- Image Acquisition: Capture images across multiple cellular compartments using standardized protocols.

- Feature Extraction: Extract quantitative morphological features from acquired images.

- Profile Analysis: Correlate morphological profiles with compound bioactivity, toxicity, and known mechanisms of action.

Expected Results: Robust morphological profiles that enable prediction of compound mechanisms of action and biological activities.

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters for Data Generation

| Method | Key Parameters | Output Format | Processing Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Checker | Bioactivity levels, similarity metrics | Numerical descriptors | <9 hours (GPU) [34] |

| QUIZ-C Network Construction | Z-score threshold, consensus criteria | Gene-perturbagen networks | Varies by dataset size [32] |

| Morphological Profiling | Cell type, imaging parameters, feature set | Quantitative morphological features | Dependent on throughput [35] |

Integration Strategies and Analytical Approaches

Network-Based Integration

Network-based methods provide a powerful framework for integrating diverse data types by representing entities as nodes and their relationships as edges [32]. The Pathopticon approach demonstrates how gene-drug perturbation networks can be integrated with cheminformatic data and diverse disease phenotypes to prioritize drugs in a cell type-dependent manner [32]. This integration enables the identification of shared intermediate phenotypes and key pathways targeted by predicted drugs, offering mechanistic insights beyond simple signature matching.

Similarity-Based Integration

Similarity-based approaches measure the concordance between different types of biological profiles. The Chemical Checker enables comparison of compounds based on their bioactivity signatures across multiple levels of biological complexity [34]. Similarly, QuartataWeb computes chemical-chemical similarities based on latent factor models learned from DrugBank or STITCH data, facilitating the identification of compounds with similar biological activities [33].

Statistical Integration Frameworks

Statistical methods such as the Pathophenotypic Congruity Score (PACOS) in Pathopticon measure the agreement between input signatures and perturbagen signatures within a global network of diverse disease phenotypes [32]. By combining these scores with pharmacological activity data, this approach improves drug prioritization compared to using either data type alone.

Diagram 2: Analytical Framework for Integrated Data

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated Chemogenomics

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Checker | Bioactivity Database | Provides standardized bioactivity signatures for >1M compounds [34] | https://chemicalchecker.org |

| QuartataWeb | Pathway Analysis Server | Predicts chemical-target interactions and links to pathways [33] | http://quartata.csb.pitt.edu |

| EU-OPENSCREEN Compound Library | Chemical Library | Carefully curated bioactive compounds for morphological profiling [35] | Available through EU-OPENSCREEN |

| LINCS-CMap Database | Pharmacogenomic Resource | Contains gene expression responses to chemical perturbations [32] | https://clue.io |

| Pathopticon Algorithm | Computational Tool | Integrates pharmacogenomics and cheminformatics for drug prioritization [32] | https://github.com/r-duh/Pathopticon |

| Cell Painting Assay Kit | Experimental Reagent | Enables morphological profiling across cellular compartments [35] | Commercial suppliers |

Applications in Drug Discovery

Polypharmacology and Drug Repurposing

The integration of bioactivity, pathway, and morphological data enables the identification of polypharmacological compounds that interact with multiple targets [33]. QuartataWeb facilitates polypharmacological evaluation by identifying shared targets and pathways for drug combinations, as demonstrated in applications for Huntington's disease models [33]. Similarly, Pathopticon's integration of pharmacogenomic and cheminformatic data helps identify repurposing opportunities by measuring agreement between drug perturbation signatures and diverse disease phenotypes [32].

Mechanism of Action Prediction

Morphological profiling serves as a powerful approach for predicting mechanisms of action for uncharacterized compounds [35]. By correlating morphological features with specific bioactivities and protein targets, researchers can classify compounds based on their functional effects. When combined with bioactivity and pathway information, morphological profiling provides a comprehensive view of compound activity across multiple biological scales.

Toxicity and Side Effect Prediction

Integrated data approaches can predict potential toxicities and side effects by identifying off-target pathways and biological processes affected by compounds. The network-based approaches in QuartataWeb and Pathopticon enable the identification of secondary interactions and pathway perturbations that may underlie adverse effects [33] [32].

The integration of bioactivity data, pathway information, and morphological profiling represents a powerful paradigm for advancing chemical biology and chemogenomics research. Frameworks such as the Chemical Checker, QuartataWeb, and Pathopticon provide robust methodologies for combining these diverse data types, enabling more predictive and mechanism-based drug discovery. As these resources continue to evolve and expand, they offer the potential to transform drug discovery by providing a comprehensive, systems-level understanding of compound activities across multiple biological scales and contexts.

Phenotypic screening is a powerful drug discovery approach that identifies bioactive compounds based on their ability to induce desirable changes in observable characteristics of cells, tissues, or whole organisms, without requiring prior knowledge of a specific molecular target [36]. After decades dominated by target-based screening, phenotypic strategies have undergone a significant resurgence driven by advances in high-content imaging, artificial intelligence (AI)-powered data analysis, and the development of more physiologically relevant biological models such as 3D organoids and patient-derived stem cells [36]. This shift is particularly valuable in the context of chemical biology and chemogenomics libraries research, where understanding the complex interactions between small molecules and biological systems is paramount.