Chemogenomic Signature Similarity Analysis: A Powerful Framework for Accelerating Drug Discovery and Target Identification

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemogenomic signature similarity analysis, a powerful methodology that connects chemical and genomic information to drive drug discovery.

Chemogenomic Signature Similarity Analysis: A Powerful Framework for Accelerating Drug Discovery and Target Identification

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemogenomic signature similarity analysis, a powerful methodology that connects chemical and genomic information to drive drug discovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles that define chemogenomic fitness profiles, such as HIP and HOP assays. The piece details cutting-edge methodological approaches, from competitive fitness profiling to machine learning and AI-driven models for de novo molecular design. It further addresses critical challenges in data reproducibility and standardization, offering practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, the article covers robust validation frameworks, including cross-species prediction and meta-analysis techniques, demonstrating how this integrative approach reliably identifies drug targets, elucidates mechanisms of action, and prioritizes novel therapeutics, thereby accelerating the entire drug development pipeline.

Defining Chemogenomic Signatures: Core Concepts and Biological Foundations

What is Chemogenomics?

Chemogenomics is a systematic strategy in drug discovery that investigates the interactions between small molecule libraries and families of biological targets on a genome-wide scale [1] [2]. Its core principle is the parallel identification of biological targets and biologically active compounds, thereby accelerating the conversion of phenotypic observations into target-based drug discovery approaches [3]. This field operates on the concept that similar receptors often bind similar ligands, allowing for the extrapolation of chemical interactions across entire protein families [4].

Two primary experimental approaches define chemogenomics research:

- Forward chemogenomics: Begins with a phenotypic screen to identify small molecules that induce a desired cellular response, followed by target deconvolution to find the protein responsible for the observed phenotype [1] [2].

- Reverse chemogenomics: Starts with a specific protein target and screens for small molecules that perturb its function in vitro, then analyzes the phenotypic consequences in cellular or whole-organism systems [1] [2].

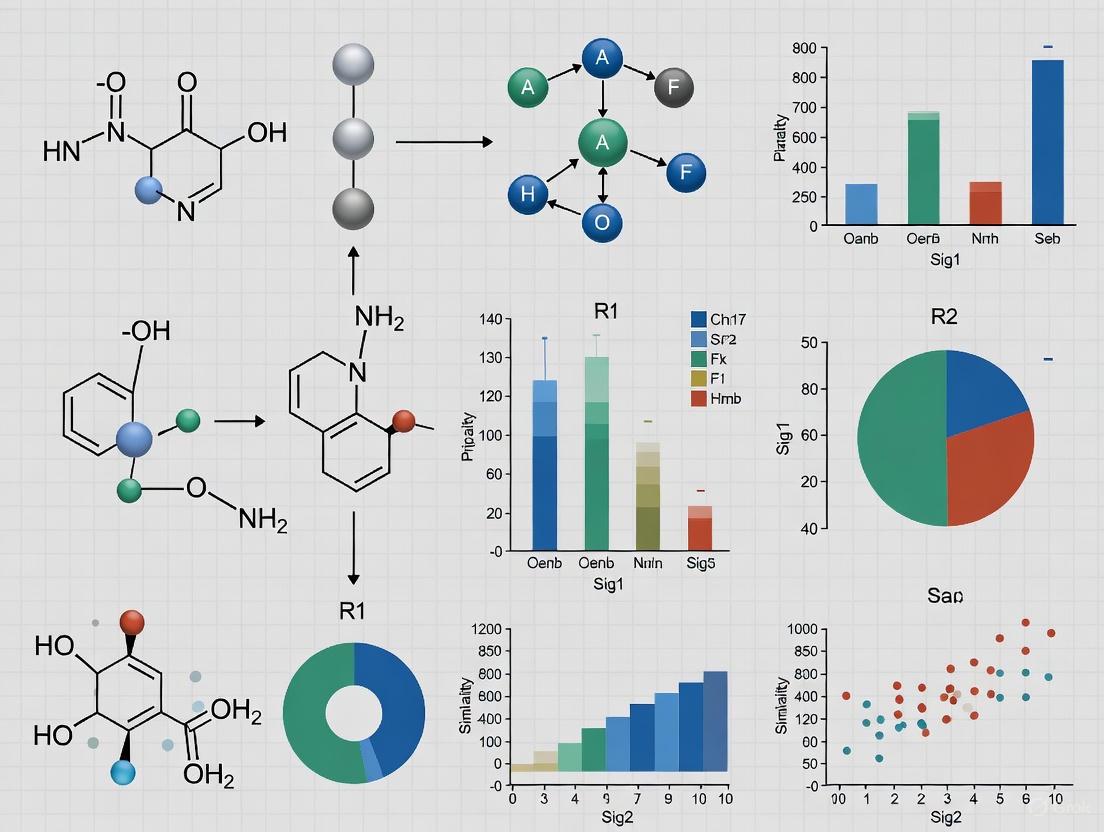

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework and key methodologies in chemogenomics:

Key Experimental Approaches in Chemogenomics

Fitness-Based Profiling in Model Organisms

Yeast chemogenomic profiling represents one of the most well-established platforms for fitness-based screening. The HaploInsufficiency Profiling and HOmozygous Profiling (HIPHOP) platform utilizes barcoded heterozygous and homozygous yeast knockout collections to measure genome-wide chemical-genetic interactions [5]. The HIP assay exploits drug-induced haploinsufficiency, where heterozygous strains deleted for one copy of an essential gene show specific sensitivity when exposed to a drug targeting that gene product. The complementary HOP assay interrogates nonessential homozygous deletion strains to identify genes involved in drug target pathways and those required for drug resistance [5] [6].

The experimental workflow for competitive fitness-based profiling involves several critical steps, visualized below:

Morphological Profiling with Cell Painting

The Cell Painting assay represents a cutting-edge phenotypic screening approach that uses high-content imaging to capture morphological features in response to chemical perturbations [7]. This method involves staining cells with fluorescent dyes targeting multiple cellular components, followed by automated image analysis using software like CellProfiler to extract quantitative morphological features [7]. The resulting morphological profiles enable functional classification of compounds and identification of signatures associated with disease states.

Chemoproteomics for Target Identification

Chemoproteomics has emerged as a powerful complementary approach that considerably expands the target coverage of chemogenomic libraries [8]. Key methods include:

- Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP): Uses reactive chemical probes that target specific amino acids in protein families, often containing reporter functionalities for detection [8].

- Fragment-based screening: Utilizes fragment-like screening sets with diverse protein labeling chemistries to maximize coverage of targetable biological space [8].

- Solvent-based protein profiling: Employs non-directed covalent modification to identify ligandable amino acid residues across the proteome [8].

Comparative Analysis of Chemogenomic Platforms

Reproducibility Across Screening Centers

A 2022 comparison of the two largest yeast chemogenomic datasets—from an academic laboratory (HIPLAB) and the Novartis Institute of Biomedical Research (NIBR)—demonstrated substantial reproducibility despite differences in experimental and analytical pipelines [5]. The combined datasets comprised over 35 million gene-drug interactions and more than 6,000 unique chemogenomic profiles [5].

Table 1: Platform Comparison of Large-Scale Yeast Chemogenomic Screens

| Parameter | HIPLAB Dataset | NIBR Dataset |

|---|---|---|

| Strain Collection | ~1,100 heterozygous essential deletion strains; ~4,800 homozygous nonessential deletion strains | ~300 fewer detectable homozygous strains (slow-growing deletions) |

| Experimental Design | Cells collected based on actual doubling time | Samples collected at fixed time points |

| Data Normalization | Separate normalization for strain-specific uptags/downtags; batch effect correction | Normalization by "study id"; no batch effect correction |

| Fitness Score Calculation | Robust z-score based on median and MAD | Z-score normalized for median and standard deviation using quantile estimates |

| Signature Conservation | 45 major cellular response signatures identified | 66.7% of signatures reproduced |

The comparative analysis revealed that the majority (66.7%) of the 45 major cellular response signatures identified in the HIPLAB dataset were conserved in the NIBR dataset, supporting their biological relevance as conserved systems-level response systems [5].

Chemogenomic Library Composition and Coverage

Chemogenomic libraries consist of selective small-molecule pharmacological agents designed to target specific protein families. The EUbOPEN consortium, for example, aims to cover approximately 30% of the druggable genome, currently estimated at 3,000 targets [9]. These libraries are organized into subsets covering major target families including protein kinases, membrane proteins, and epigenetic modulators [9].

Table 2: Comparison of Chemogenomic Library Types and Applications

| Library Type | Coverage | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target-Focused Libraries | Specific protein families (e.g., kinases, GPCRs) | Contains known ligands for target family members; privileged structures | Reverse chemogenomics, target validation |

| Phenotypic Screening Libraries | Diverse biological pathways | Compounds with known phenotypic effects; traditional medicine compounds | Forward chemogenomics, drug repurposing |

| Chemogenomic Compound Sets | ~30% of druggable genome | Well-annotated tool compounds; less stringent selectivity criteria | Functional annotation, target identification |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful chemogenomics research requires specialized biological and chemical reagents systematically organized for screening applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents in Chemogenomics

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Yeast Libraries | Competitive fitness profiling | YKO collection: homozygous/heterozygous deletion strains [5] [6] |

| Chemical Probe Libraries | Target modulation and validation | Selective small molecules for specific protein families [3] |

| Cell Painting Assay Kits | Morphological profiling | Fluorescent dyes for multiple cellular components [7] |

| Chemoproteomic Probes | Target identification | Activity-based probes with reporter functionalities [8] |

| Reference Databases | Data analysis and interpretation | ChEMBL, KEGG, Gene Ontology, Disease Ontology [7] |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Target Validation

Mechanism of Action (MOA) Elucidation

Chemogenomics has proven particularly valuable for determining the mechanism of action for traditional medicines, including Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and Ayurveda [1]. For example, target prediction programs have identified sodium-glucose transport proteins and PTP1B as targets relevant to the hypoglycemic phenotype of "toning and replenishing medicine" in TCM [1].

Identification of Novel Drug Targets

Chemogenomic profiling has enabled the discovery of novel antibacterial targets through the application of the chemogenomics similarity principle [1]. In one case study, researchers mapped a ligand library for the murD enzyme to other members of the mur ligase family (murC, murE, murF, murA, and murG) to identify new targets for known ligands, resulting in potential broad-spectrum Gram-negative inhibitors [1].

Gene Function Discovery

Chemogenomic approaches have successfully identified genes involved in specific biological pathways. For instance, cofitness data from Saccharomyces cerevisiae deletion strains led to the discovery of the YLR143W gene as the enzyme responsible for the final step in diphthamide biosynthesis, solving a 30-year mystery in posttranslational modification [1].

Contemporary chemogenomics increasingly integrates small-molecule screening with genetic approaches such as RNA interference (RNAi) and CRISPR-Cas9 for enhanced target identification and validation [3]. This synergistic combination accelerates the deconvolution of complex phenotypic screening results while providing orthogonal validation of putative targets. As chemogenomic libraries continue to expand in both size and quality, and as computational methods improve for analyzing high-dimensional chemical-biological interaction data, chemogenomics is poised to remain a cornerstone strategy for bridging chemical and genomic spaces in therapeutic development.

Chemogenomic profiling represents a powerful, unbiased approach for understanding the genome-wide cellular response to small molecules in model organisms like Saccharomyces cerevisiae (budding yeast). These assays provide direct identification of drug target candidates and genes required for drug resistance, filling a critical gap in the drug discovery pipeline between bioactive compound discovery and target validation [5]. Among the most established platforms for systematic chemical-genetic interaction mapping are Haploinsufficiency Profiling (HIP) and Homozygous Profiling (HOP), collectively known as HIPHOP [10]. These assays measure drug-induced growth sensitivities of deletion strains grown in the presence of compounds, generating fitness defect scores that reveal functional interactions between genes and small molecules [10]. The robustness of these approaches has been demonstrated through comparative analysis of large-scale datasets, with studies showing that independent screens capture conserved systems-level response signatures despite differences in experimental and analytical pipelines [5]. Within the context of chemogenomic signature similarity analysis research, HIP and HOP assays provide foundational datasets for comparing chemical-induced phenotypes and inferring mechanisms of action through guilt-by-association principles.

Core Conceptual Frameworks and Mechanisms

Haploinsufficiency Profiling (HIP)

HIP assays utilize a pool of heterozygous diploid yeast strains, each carrying a single deletion of one copy of an essential gene. The core principle exploits drug-induced haploinsufficiency - a phenomenon where reducing the dosage of a drug's target gene from two copies to one copy results in increased cellular sensitivity to that compound [10]. Under normal conditions, one gene copy is sufficient for normal growth in diploid yeast. However, when a drug targets a specific essential protein, strains with only one functional copy of that drug target gene will exhibit a measurable growth defect compared to other strains in the pool [5] [10]. This sensitivity occurs because the reduced expression level of the target protein makes the cell more vulnerable to partial inhibition by the compound. In practice, HIP assays employ a competitive growth setup where approximately 1,100 essential heterozygous deletion strains, each tagged with unique molecular barcodes, are grown together in a single pool under compound treatment [5]. The relative abundance of each strain before and after treatment is quantified by sequencing these barcodes, with strains showing the greatest fitness defects identifying the most likely drug target candidates.

Homozygous Profiling (HOP)

HOP assays complement HIP by interrogating the complete set of non-essential homozygous deletion strains (approximately 4,800 in yeast) in either haploid or diploid backgrounds [5] [10]. Rather than identifying direct drug targets, HOP reveals genes involved in biological pathways buffering the drug target and those required for drug resistance [10]. When a non-essential gene is deleted, the strain may become hypersensitive to compounds affecting pathways that interact with or compensate for the deleted gene's function. This synthetic lethality or chemical-genetic interaction occurs because the complete deletion of a gene creates a dependency on alternative pathways, and when those pathways are simultaneously perturbed by a compound, the combined effect produces a measurable growth defect [10]. HOP profiles thus provide information about pathway context and functional relationships, identifying genes whose products buffer the cell against specific chemical perturbations or participate in the same biological process as the direct drug target.

Table: Core Conceptual Differences Between HIP and HOP Assays

| Feature | HIP Assay | HOP Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Strain Type | Heterozygous diploid deletions of essential genes | Homozygous deletions of non-essential genes |

| Gene Dosage | Reduced from two copies to one copy | Complete deletion (zero functional copies) |

| Primary Application | Direct drug target identification | Pathway context and resistance mechanism identification |

| Biological Principle | Drug-induced haploinsufficiency | Synthetic lethality/buffering relationships |

| Approximate Strain Count | ~1,100 strains | ~4,800 strains |

| Information Provided | Direct target candidates | Genetic interactors and pathway members |

Experimental Workflow and Data Generation

The experimental workflow for both HIP and HOP assays follows a similar structure, beginning with the construction of pooled mutant collections where each strain carries unique molecular barcodes [5]. For large-scale screens, these pools are grown competitively in the presence of compounds at various concentrations, with samples collected at specific time points or doubling times [5]. The fundamental measurement is the fitness defect score (FD-score), calculated as the log-ratio of growth fitness for each deletion strain in compound treatment versus control conditions [10]. A negative FD-score indicates that the strain grows more poorly in the presence of the compound compared to the control, suggesting a functional interaction between the deleted gene and the compound. The final FD-score is typically expressed as a robust z-score, where the median of all log₂ ratios in a screen is subtracted from each strain's log₂ ratio, then divided by the median absolute deviation of all ratios [5]. This normalization facilitates cross-experiment comparison and identifies statistically significant chemical-genetic interactions.

Diagram: Experimental workflow for HIP and HOP profiling. Both assays begin with pooled mutant collections treated with compounds, followed by barcode sequencing and fitness defect calculation, but yield complementary biological insights.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Strain Pool Construction and Validation

The foundation of both HIP and HOP assays lies in the comprehensive deletion collections. The yeast knockout (YKO) collection provides systematic deletion of every verified open reading frame in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome, with each strain containing unique 20-base-pair molecular barcodes (uptags and downtags) that enable pooled growth and parallel fitness measurements [5]. For HIP assays, the diploid heterozygous collection targets approximately 1,100 essential genes, while the HOP assay utilizes the homozygous deletion collection of approximately 4,800 non-essential genes [5]. Critical to pool quality is the validation of strain representation and growth characteristics, as slow-growing deletions may be underrepresented in competitive pools. Protocol differences exist between screening platforms; for instance, some laboratories collect samples based on actual doubling times while others use fixed time points as proxies for cell doublings [5]. These methodological variations can affect which strains remain detectable in the final pool, particularly for slow-growing mutants that may be lost during extended growth periods.

Competitive Growth and Compound Treatment

In a typical HIPHOP screen, the pooled mutant collections are grown competitively in liquid culture containing the test compound at concentrations determined through preliminary dose-response experiments [5]. Multiple replicates and concentration points are typically included to ensure robustness. The cultures are inoculated at low density and allowed to grow for several generations, usually between 5-20 population doublings, during which strains with enhanced sensitivity to the compound become progressively underrepresented in the population [5]. Control cultures without compound treatment are grown in parallel to account for natural fitness differences between strains. Specific protocols vary between research groups - for example, the NIBR (Novartis Institute of Biomedical Research) screens collected samples at fixed time points, while academic (HIPLAB) protocols collected based on actual doubling times [5]. These differences in experimental design can influence the resulting fitness measurements and must be considered when comparing datasets from different sources.

Barcode Sequencing and Fitness Quantification

Following competitive growth, genomic DNA is extracted from both compound-treated and control samples, and the unique molecular barcodes are amplified using PCR with universal primers. The relative abundance of each strain is quantified through next-generation sequencing of these barcode libraries [5]. The raw sequencing counts undergo multiple normalization steps to account for technical variations, including batch effects, background signal thresholds, and tag-specific performance [5]. Different laboratories employ distinct processing pipelines; for instance, some normalize separately for strain-specific uptags and downtags then select the "best tag" for each strain based on the lowest robust coefficient of variation across control arrays [5]. The core output is the fitness defect score, though the exact calculation differs - some implementations use median signals while others use average intensities, with varying approaches to replicate handling and final z-score normalization [5]. These analytical differences highlight the importance of understanding methodology when comparing or integrating chemogenomic profiles.

Table: Key Methodological Variations in HIPHOP Screening Platforms

| Methodological Aspect | HIPLAB Protocol | NIBR Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Based on actual doubling time | Fixed time points |

| Strain Detection | ~4800 homozygous strains detectable | ~300 fewer slow-growing homozygous strains |

| Data Normalization | Separate normalization for uptags/downtags; batch effect correction | Normalization by "study id" without batch correction |

| Control Handling | Median signal of controls | Average intensities of controls |

| FD-score Calculation | log₂(median control / treatment signal) | Inverse log₂ ratio with average signals |

| Final Score | Robust z-score (median/MAD) | Z-score normalized using quantile estimates |

Data Analysis and Target Identification Methods

Traditional Fitness Defect Scoring

The standard approach for identifying putative drug targets from HIPHOP screens ranks genes according to their fitness defect scores, with the most sensitive strains (most negative FD-scores) considered most likely to be related to the drug target [10]. In HIP assays, the top candidates typically represent the direct targets, where heterozygosity creates hypersensitivity. In HOP assays, the most sensitive strains often identify genes that buffer the target pathway or participate in resistance mechanisms. The FD-score is calculated as FDᵢ꜀ = log₂(rᵢ꜀) - log₂(r̄ᵢ), where rᵢ꜀ is the growth rate of strain i under compound c treatment, and r̄ᵢ is its average growth rate under control conditions [10]. While this straightforward approach has identified numerous validated drug targets, it has limitations - primarily, it considers each gene in isolation without accounting for epistatic interactions or functional relationships between genes [10]. This limitation becomes particularly significant given that the phenotype of a specific strain may sometimes be caused by deletion of a genetic modifier of a neighboring gene rather than the direct drug target [10].

Network-Assisted Target Identification

To address limitations of traditional scoring methods, GIT (Genetic Interaction Network-Assisted Target Identification) incorporates the fitness defects of a gene's neighbors in the genetic interaction network [10]. This approach recognizes that if a gene is genuinely targeted by a compound, its genetic interaction partners should also show modulated fitness defects in chemogenomic screens [10]. GIT uses a signed, weighted genetic interaction network constructed from Synthetic Genetic Array (SGA) data, with edge weights representing the strength and direction of genetic interactions [10]. For HIP assays, the GITᴴᴵᴾ-score supplements a gene's FD-score with the FD-scores of its direct neighbors, giving weight to neighbors connected by positive genetic interactions while discounting those with negative interactions [10]. For HOP assays, GITᴴᴼᴺ incorporates FD-scores of longer-range "two-hop" neighbors, reflecting that HOP profiles often identify genes buffering the direct target pathway [10]. This network-based approach substantially outperforms traditional FD-score ranking, improving target identification accuracy in both HIP and HOP assays [10].

Diagram: Network-assisted target identification workflow. GIT incorporates genetic interaction network data with fitness scores to improve target prediction in both HIP and HOP assays.

Integrative Analysis for Mechanism of Action Elucidation

The most powerful applications of HIPHOP data emerge from integrative analysis that combines both assay types with complementary data sources. By simultaneously analyzing HIP and HOP profiles, researchers can distinguish direct targets (prioritized in HIP) from pathway members and resistance mechanisms (enriched in HOP) [10]. This combined approach significantly boosts target identification performance over either assay alone [10]. Further integration with large-scale chemogenomic compendia allows for mechanism of action prediction through signature similarity analysis [5]. Studies comparing over 6,000 chemogenomic profiles revealed that the cellular response to small molecules is limited and can be described by a network of approximately 45 major chemogenomic signatures [5]. The majority of these signatures (66.7%) are conserved across independent datasets, confirming their biological relevance as conserved systems-level response systems [5]. These conserved signatures enable "guilt-by-association" compound classification, where novel compounds with similar HIPHOP profiles to well-characterized compounds are inferred to share mechanisms of action.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Chemical Biology

Target Identification and Validation

HIPHOP profiling has proven particularly valuable for identifying the mechanisms of action of bioactive compounds discovered in phenotypic screens. The approach directly links compounds to their cellular targets by revealing which gene deletions confer hypersensitivity [5]. For example, HIP assays have successfully identified known drug-target pairs such as rapamycin-TOR1 and tunicamycin-ALG7, validating the approach [10]. Beyond confirming expected interactions, the unbiased nature of HIPHOP screens has revealed novel targets for uncharacterized compounds, including natural products with complex cellular effects [5]. The methodology has also identified secondary targets of clinical drugs, explaining side effects and revealing potential repurposing opportunities. The transferability of yeast chemical genomic results to human systems is enabled when target proteins' functions are conserved through evolution, allowing yeast screens to inform mammalian drug discovery [10].

Pathway Mapping and Functional Genomics

Beyond direct target identification, HOP profiling excels at mapping pathway architecture and functional relationships between genes. Genes with similar HOP profiles across many compounds often participate in the same biological pathway or protein complex [5] [10]. This cofitness relationship enables functional annotation of uncharacterized genes based on their similarity to well-studied genes in chemogenomic space [5]. The comprehensive nature of these datasets also reveals genetic interactions and buffering relationships, with simultaneous deletion of one gene and chemical inhibition of its buffer pathway producing synthetic sickness or lethality [10]. These functional maps provide rich resources for systems biology, revealing how cellular pathways are wired to maintain homeostasis under chemical stress. Analysis of large-scale HOP data has shown significant enrichment for Gene Ontology biological processes, with the majority (81%) of chemogenomic signatures associated with specific biological functions [5].

Integration with Mammalian Systems and Translational Applications

While initially developed in yeast, the principles of chemogenomic profiling have been extended to mammalian systems through CRISPR-based screening approaches [5]. International consortia including BioGRID, PRISM, LINCS, and DepMAP are gathering multidimensional chemogenomic data from diverse human cell lines challenged with chemical libraries [5]. The analytical frameworks developed for yeast HIPHOP studies, including signature-based similarity analysis and network-assisted target identification, provide valuable guidelines for these mammalian efforts [5]. The integration of chemogenomic profiles with other data types, such as transcriptomics, has further expanded applications. For instance, generative artificial intelligence models have been developed that bridge systems biology and molecular design by conditioning generative adversarial networks on transcriptomic data [11]. These models can automatically design molecules with a high probability of inducing desired transcriptomic profiles, creating a virtuous cycle between chemogenomic perturbation and compound design [11].

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for HIPHOP Studies

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Materials | Yeast knockout collection (YKO); Diploid heterozygous deletion pool; Homozygous deletion pool | Foundation for competitive growth assays; provides comprehensive genome coverage |

| Molecular Tools | 20bp molecular barcodes (uptags/downtags); Universal PCR primers | Enables parallel strain quantification via sequencing; unique identification of each strain |

| Chemical Libraries | FDA-approved drug collections; Natural product libraries; Diversity-oriented synthesis compounds | Sources of bioactive small molecules for perturbation studies |

| Genetic Interaction Data | Synthetic Genetic Array (SGA) profiles; Costanzo et al. 2016 dataset | Network information for GIT analysis; functional relationships between genes |

| Analytical Tools | GIT algorithm; Rank-based enrichment methods; Signature similarity algorithms | Target identification; mechanism of action prediction; data interpretation |

| Data Repositories | Chemogenomics database at Stanford; Dryad repository; BioGRID ORCS | Public data access; comparative analysis; meta-analysis studies |

| Comparative Resources | HIPLAB dataset; NIBR dataset; Connectivity Map (CMap) | Reference profiles for comparison; cross-validation of results |

Comparative Performance and Limitations

Strengths and Complementary Applications

HIP and HOP assays offer complementary strengths that make their combined application particularly powerful. HIP excels at direct target identification for compounds targeting essential genes, providing straightforward candidate prioritization based on haploinsufficiency [10]. The assay directly reports on drug-target interactions without relying on correlation or reference databases, offering an unbiased approach [5]. HOP profiling provides broader pathway context, identifying genes involved in drug resistance, buffering relationships, and compensatory pathways [10]. This pathway information helps situate direct targets within broader cellular networks and explains resistance mechanisms that may emerge during drug treatment. When combined, the two assays provide a more comprehensive view of drug mechanism than either alone, with integrated analysis significantly boosting target identification performance [10]. The robustness of these approaches has been demonstrated through cross-laboratory comparisons showing that independent screens capture conserved response signatures despite methodological differences [5].

Limitations and Considerations

Several limitations affect both HIP and HOP assays. False positives can arise from general sickness or pleiotropic effects rather than specific target relationships, requiring careful dose-response studies and secondary validation [5]. False negatives occur when deletion strains are underrepresented in pools (particularly slow-growing strains in HOP) or when genetic background effects influence results [5]. Technical variations between platforms, including differences in sample collection timing, normalization strategies, and FD-score calculations, can affect cross-dataset comparisons and reproducibility [5]. Biological limitations include the inability to identify targets when compound activity requires metabolic activation not present in yeast, or when targeting processes not conserved from yeast to humans [10]. For HOP specifically, the complete deletion of non-essential genes may reveal buffering relationships but can miss subtle functional contributions that would be apparent in partial inhibition scenarios. These limitations highlight the importance of orthogonal validation and the value of integrating HIPHOP data with complementary approaches like transcriptomics or structural information.

Emerging Innovations and Future Directions

The field of chemogenomic profiling continues to evolve with several promising directions emerging. Network integration methods like GIT represent a significant advance over traditional scoring approaches, demonstrating how auxiliary information can enhance target identification [10]. Multi-species profiling approaches that compare chemical-genetic interactions across evolutionary distance help distinguish conserved core targets from species-specific effects [5]. The application of artificial intelligence to chemogenomic data enables novel approaches like de novo molecule generation from gene expression signatures [11]. Meta-analysis frameworks that integrate multiple disease signatures address heterogeneity challenges and improve drug repurposing predictions [12]. As chemogenomic datasets continue to expand in both scale and dimensionality, future innovations will likely focus on multi-optic integration, dynamic profiling across time and concentration, and increasingly sophisticated computational models that predict compound mechanisms based on signature similarity to well-characterized reference profiles.

Chemogenomics represents a systematic approach to drug discovery that involves screening targeted chemical libraries of small molecules against specific families of drug targets, with the ultimate goal of identifying novel drugs and drug targets [1]. This field operates on the principle that the completion of the human genome project has provided an abundance of potential targets for therapeutic intervention, and chemogenomics aims to study the intersection of all possible drugs on all these potential targets. The field is broadly divided into two experimental approaches: forward chemogenomics, which attempts to identify drug targets by searching for molecules that produce a specific phenotype in cells or animals, and reverse chemogenomics, which validates phenotypes by searching for molecules that interact specifically with a given protein [1].

The 'guilt-by-association' principle serves as a fundamental concept in chemogenomic analysis, operating on the premise that genes or proteins with similar patterns of response to chemical perturbations likely share functional relationships or participate in common biological pathways [13]. This principle enables researchers to infer mechanisms of action for uncharacterized compounds by comparing their chemogenomic profiles to those with known targets. In practice, this means that when a novel compound produces a fitness profile similar to a well-characterized drug, it suggests shared molecular targets or affected pathways, providing crucial insights for drug discovery and target validation [5] [14].

Experimental Methodologies in Chemogenomic Profiling

Core Profiling Technologies

HIPHOP Chemogenomic Profiling

The HaploInsufficiency Profiling and HOmozygous Profiling (HIPHOP) platform employs barcoded heterozygous and homozygous yeast knockout collections to provide a comprehensive genome-wide view of the cellular response to chemical compounds [5]. The HIP assay exploits drug-induced haploinsufficiency, where strain-specific sensitivity occurs in heterozygous strains deleted for one copy of an essential gene when exposed to a drug targeting that gene's product. In this assay, approximately 1,100 essential heterozygous deletion strains are grown competitively in a single pool, with fitness quantified by barcode sequencing. The resulting fitness defect (FD) scores report the relative abundance and drug sensitivity of each strain, with heterozygous strains showing the greatest FD scores identifying the most likely drug target candidates [5].

The complementary HOP assay interrogates approximately 4,800 nonessential homozygous deletion strains, identifying genes involved in the drug target biological pathway and those required for drug resistance. The combined HIPHOP chemogenomic profile provides a powerful system for identifying drug-target candidates and understanding comprehensive cellular responses to specific compounds [5].

Large-Scale Comparative Studies

Substantial methodological advances have been demonstrated through large-scale comparisons of chemogenomic datasets. A 2022 study analyzing two major yeast chemogenomic datasets—from an academic laboratory (HIPLAB) and the Novartis Institute of Biomedical Research (NIBR)—revealed robust chemogenomic response signatures despite substantial differences in experimental and analytical pipelines [5]. The combined datasets comprised over 35 million gene-drug interactions and more than 6,000 unique chemogenomic profiles, characterized by gene signatures, enrichment for biological processes, and mechanisms of drug action.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Chemogenomic Screening Platforms

| Platform Characteristic | HIPLAB Academic Platform | NIBR Platform |

|---|---|---|

| Strain Collection | ~1,100 heterozygous essential deletion strains; ~4,800 homozygous nonessential deletion strains | ~300 fewer detectable homozygous deletion strains due to overnight growth |

| Data Normalization | Separate normalization for strain-specific uptags/downtags; batch effect correction | Normalization by "study id" without batch effect correction |

| Fitness Quantification | Log2 of median control signal divided by compound treatment signal | Inverse log2 ratio using average intensities |

| Final Scoring | Robust z-score (median subtracted and divided by MAD) | Gene-wise z-score normalized using quantile estimates |

| Reference | [5] | [5] |

Application in Parasitic Diseases

Chemogenomic profiling has demonstrated significant utility in antimalarial drug discovery. Research on Plasmodium falciparum utilized piggyBac single insertion mutants profiled for altered responses to antimalarial drugs and metabolic inhibitors to create chemogenomic profiles [14]. This approach revealed that drugs targeting the same pathway shared similar response profiles, and multiple pairwise correlations of the chemogenomic profiles provided novel insights into drug mechanisms of action. Notably, a mutant of the artemisinin resistance candidate gene "K13-propeller" exhibited increased susceptibility to artemisinin drugs and identified a cluster of seven mutants based on similar enhanced responses to the tested drugs [14].

The application of chemogenomics in this context revealed artemisinin's functional activity, linking unexpected drug-gene relationships to signal transduction and cell cycle regulation pathways. This approach represents a significant advancement over traditional methods for identifying genes associated with active compounds, which are often limited in sensitivity and can yield population-specific conclusions [14].

Analytical Frameworks and Computational Approaches

Signature-Based Analysis

The analysis of large-scale chemogenomic data has revealed that the cellular response to small molecules is surprisingly limited and structured. Research comparing the HIPLAB and NIBR datasets identified that the majority (66.7%) of 45 major cellular response signatures previously reported were conserved across both datasets, providing strong support for their biological relevance as conserved systems-level, small molecule response systems [5]. This discovery suggests that cellular responses to chemical perturbations follow consistent patterns that can be categorized into discrete signatures.

The remarkable consistency of these signatures across independently generated datasets indicates that chemogenomic responses are constrained by cellular architecture and network topology rather than being random or compound-specific. This finding has profound implications for drug discovery, as it suggests that mechanisms of action can be classified into a finite number of categories based on their chemogenomic signatures [5].

Addressing Multifunctionality Bias

A critical consideration in guilt-by-association analysis is the impact of multifunctionality on prediction accuracy. Research has demonstrated that multifunctionality, rather than association, can be a primary driver of gene function prediction [13]. Knowledge of the degree of multifunctionality alone can produce remarkably strong performance when used as a predictor of gene function, and this multifunctionality is encoded in gene interaction data such as protein interactions and coexpression networks.

This bias manifests because highly connected "hub" genes in biological networks tend to be involved in multiple functions, leading to false positive associations in guilt-by-association analyses. Computational controls must be implemented to distinguish true functional associations from those merely reflecting multifunctionality [13]. This source of bias has widespread implications for the interpretation of genomics studies and must be carefully controlled for in chemogenomic signature analyses.

Table 2: Key Computational Considerations in Guilt-by-Association Analysis

| Analytical Factor | Impact on Guilt-by-Association | Recommended Controls |

|---|---|---|

| Multifunctionality Bias | Highly multifunctional genes produce false positives; drives predictions independent of specific associations | Implement degree-aware statistical models; use multifunctionality as covariate |

| Network Quality | False positive interactions in original network propagate to functional predictions | Apply "top overlap" method retaining only edges among highest scoring for both genes |

| Negative Control Selection | Inappropriate controls inflate performance measures | Use carefully matched control groups; avoid random sampling without functional consideration |

| Node Degree Correlation | High-degree nodes connected to many functions regardless of specificity | Normalize for node degree; assess significance against degree-matched null models |

| Reference | [13] | [13] |

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemogenomic Profiling

| Reagent / Material | Function in Chemogenomic Studies | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Yeast Knockout Collections | Enables pooled fitness assays; heterozygous for essential genes (HIP), homozygous for nonessentials (HOP) | HIPHOP profiling; genome-wide fitness quantification [5] |

| piggyBac Mutant Libraries | Insertional mutagenesis for creating mutant profiles in various organisms | Plasmodium falciparum chemogenomic profiling [14] |

| Molecular Barcodes (20bp identifiers) | Enables tracking of individual strain abundance in pooled experiments via sequencing | Multiplexed fitness assays; barcode sequencing [5] |

| Targeted Chemical Libraries | Focused compound sets against specific target families (GPCRs, kinases, etc.) | Reverse chemogenomics; target validation [1] |

| Gene Ontology (GO) Databases | Standardized functional classification system for gene annotation | Functional enrichment analysis; guilt-by-association mapping [13] |

Workflow Visualization of Guilt-by-Association Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for chemogenomic signature analysis using the guilt-by-association principle:

Diagram 1: Chemogenomic Signature Analysis Workflow

Comparative Performance of Methodologies

Cross-Platform Reproducibility

The comparative analysis of the HIPLAB and NIBR datasets provides valuable insights into the reproducibility of chemogenomic approaches. Despite differences in experimental protocols and analytical pipelines, both datasets revealed robust chemogenomic response signatures [5]. This reproducibility underscores the reliability of chemogenomic profiling for identifying genuine biological responses rather than technical artifacts.

Key findings from this comparison included excellent agreement between chemogenomic profiles for established compounds and correlations between entirely novel compounds. The studies characterized global properties common to both datasets, including specific drug targets, correlation between chemical profiles with similar mechanisms, and cofitness between genes with similar biological function [5]. This demonstrates that core biological signals in chemogenomic data persist across methodological variations.

Signature Conservation Analysis

The identification of conserved signatures across independent datasets provides strong evidence for their biological significance. The finding that 66.7% of response signatures were conserved between HIPLAB and NIBR datasets indicates that these signatures represent fundamental cellular response patterns rather than dataset-specific artifacts [5]. This conservation strengthens their utility for mechanism of action prediction through guilt-by-association approaches.

By combining multiple datasets, researchers were able to identify robust chemogenomic responses both common and research site-specific, with the majority (81%) enriched for Gene Ontology biological processes and associated with gene signatures [5]. This integration enhanced the power to infer chemical diversity/structure and gauge screen-to-screen reproducibility within replicates and between compounds with similar mechanisms of action.

The 'guilt-by-association' principle provides a powerful framework for linking chemogenomic signatures to mechanisms of action in drug discovery. Through standardized experimental protocols like HIPHOP profiling and computational approaches that account for multifunctionality biases, researchers can reliably classify compounds based on their chemogenomic signatures. The reproducibility of signature patterns across independent platforms and the conservation of response modules underscore the robustness of this approach. As chemogenomic resources continue to expand through consortia such as BioGRID, PRISM, LINCS, and DepMAP, the application of guilt-by-association principles will become increasingly powerful for accelerating drug discovery and target validation across diverse biological systems.

Introduction: In the field of drug discovery, a significant challenge lies in comprehensively understanding how cells respond to chemical perturbations. A compelling body of evidence, primarily from large-scale chemogenomic fitness screens in model organisms like Saccharomyces cerevisiae, suggests that the cellular response to small molecules is not infinitely complex but is instead funneled through a limited set of biological response signatures. This guide objectively compares the evidence, methodologies, and analytical frameworks that support this thesis, providing drug development professionals with a clear comparison of the key findings and the tools that generated them.

The Core Thesis: Evidence for a Limited Response Network

The concept of a limited cellular response arises from the systematic analysis of chemogenomic profiles—genome-wide measurements of cellular fitness after drug treatment. A landmark comparison of two independent large-scale datasets revealed that despite substantial differences in their experimental and analytical pipelines, they shared robust, conserved response signatures [5].

- Conserved Signatures: Analysis of over 35 million gene-drug interactions and more than 6,000 unique chemogenomic profiles from an academic lab (HIPLAB) and the Novartis Institute of Biomedical Research (NIBR) revealed that the cellular response to diverse small molecules could be described by a network of just 45 core chemogenomic signatures [5].

- Cross-Platform Validation: The majority of these signatures (66%) were identified in both the HIPLAB and NIBR datasets, underscoring their biological relevance as conserved, system-level response mechanisms rather than artifacts of a specific screening platform [5].

- Biological Interpretation: These 45 signatures are characterized by specific gene sets and are significantly enriched for distinct Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes, connecting the chemical perturbations to defined functional pathways within the cell [5].

This foundational work indicates that cells utilize a finite, modular defense and adaptation network, a discovery that simplifies the daunting complexity of drug-cell interactions and provides a structured framework for understanding mechanisms of action.

Comparative Analysis of Key Screening Methodologies

The evidence for a limited cellular response is underpinned by specific high-throughput experimental techniques. The table below compares the two primary screening approaches that have contributed to this field.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Chemogenomic Screening Methods

| Screening Method | Core Principle | Typical Application | Key Advantage for Response Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Chemogenomics (Phenotypic) | Identify compounds that induce a specific phenotype, then determine the molecular target [1]. | Phenotypic drug discovery, identifying novel biologically active compounds [1]. | Unbiased discovery of compounds and mechanisms that produce a observable cellular response. |

| Reverse Chemogenomics (Target-based) | Identify compounds that perturb a specific target, then analyze the induced phenotype in cells or organisms [1]. | Validating phenotypes associated with a given protein, often enhanced by parallel screening [1]. | Directly links a predefined molecular target to a broader cellular response signature. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: HIPHOP Profiling

A quintessential example of a forward chemogenomic approach is the combined HaploInsufficiency Profiling and HOmozygous Profiling (HIPHOP) platform used in the foundational yeast studies [5]. The detailed workflow is as follows:

- Pooled Strain Construction: A barcoded pool of approximately ~1,100 heterozygous deletion strains of essential genes (for HIP) and ~4,800 homozygous deletion strains of non-essential genes (for HOP) is constructed [5].

- Competitive Growth Under Perturbation: The pooled strain collection is grown competitively in culture and exposed to the drug compound of interest.

- Fitness Measurement via Sequencing: Post-growth, the relative abundance of each strain is quantified by sequencing the unique molecular barcodes. A fitness defect (FD) score is calculated for each strain, representing its sensitivity or resistance to the drug [5].

- Data Integration and Signature Generation:

- The HIP assay identifies the most likely drug targets, as heterozygous strains deleted for a drug's protein target show heightened sensitivity (decreased fitness) [5].

- The HOP assay identifies genes involved in the drug's biological pathway and those required for drug resistance [5].

- The combined HIPHOP profile provides a comprehensive, genome-wide view of the cellular response to a specific compound, which can then be clustered with other profiles to identify common signatures [5].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and analysis of the HIPHOP assay leading to the identification of core signatures.

Analytical and Computational Tools for Signature Detection

Translating raw fitness data into the conclusion of a limited response network relies on sophisticated bioinformatics and in silico tools. These tools help standardize and mine complex chemogenomic data.

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Chemogenomic Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Primary Function | Application in Response Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| CACTI | An open-source annotation and target hypothesis prediction tool that mines multiple chemical and biological databases for common names, synonyms, and structurally similar molecules [15]. | Standardizes compound identifiers across studies and identifies close chemical analogs, enabling the grouping of similar response profiles and expanding the evidence base for shared signatures [15]. |

| MAGENTA | A computational framework that uses chemogenomic profiles and metabolic perturbation data to predict synergistic drug interactions across different microenvironments [16]. | Demonstrates that core cellular response mechanisms (predictive genes) can be used to forecast drug interactions in new contexts, reinforcing the concept of a finite, predictable response network [16]. |

| Chemogenomic Databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) | Public repositories of bioactivity data, compound information, and screening results [7] [15]. | Provide the foundational data for large-scale meta-analyses that reveal conserved patterns and limited response signatures across thousands of compounds [5] [7]. |

The analytical process that leverages these tools to move from raw data to a systems-level conclusion is depicted below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution and analysis of large-scale chemogenomic screens depend on a suite of key reagents and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Chemogenomic Screening

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Barcoded Yeast Knockout Collections | The foundational biological resource for HIPHOP assays. Each strain has a unique molecular barcode, enabling pooled fitness screens and direct, unbiased identification of drug-gene interactions [5]. |

| Curated Chemogenomic Libraries | Libraries of small molecules designed to represent a large and diverse panel of drug targets. They are essential for phenotypic screening and probing the breadth of cellular response mechanisms [7]. |

| Cell Painting Assay Kits | A high-content, image-based assay that uses fluorescent dyes to label cellular components. It generates rich morphological profiles that can be linked to chemogenomic data for deep phenotypic analysis [7]. |

| Graph Database Platforms (e.g., Neo4j) | A high-performance NoSQL graph database used to integrate heterogeneous data sources (e.g., drug-target, pathways, diseases) into a unified network pharmacology model for systems-level analysis [7]. |

| Clustering & Enrichment Analysis Software (e.g., R/clusterProfiler) | Bioinformatics tools used to group chemogenomic profiles with similar responses and determine the biological processes (GO, KEGG) that are statistically over-represented in each signature cluster [5] [7]. |

The convergence of evidence from multiple large-scale independent studies strongly supports the thesis that the cellular response to chemical perturbation is limited, organized into a finite set of core chemogenomic signatures. This finding has profound implications for drug discovery, suggesting that mechanism-of-action elucidation and the prediction of drug interactions can be simplified by focusing on a defined set of cellular response modules. Future work will focus on extending these principles to mammalian systems using CRISPR-based screens and on further refining the predictive power of in silico models like MAGENTA to tailor therapies based on the specific cellular microenvironment.

Chemogenomics represents a systematic framework in modern drug discovery that investigates the interaction between chemical compounds and biological target families on a genomic scale. The primary goal is to concurrently identify novel therapeutic targets and bioactive compounds [1]. This field operates on the principle that studying the intersection of all possible drugs against all potential targets can dramatically accelerate the drug discovery process [1]. Within this paradigm, two complementary strategies have emerged: forward chemogenomics and reverse chemogenomics. These approaches differ fundamentally in their starting points and methodological workflows, yet share the common objective of linking chemical compounds to biological outcomes, thereby enabling more efficient therapeutic development.

The strategic implementation of these approaches allows researchers to address different stages of the drug discovery pipeline. Forward chemogenomics begins with phenotypic observation and works toward target identification, making it ideal for discovering novel biological mechanisms. In contrast, reverse chemogenomics starts with a predefined molecular target and seeks compounds that modulate its activity, providing a more directed path for drug optimization [1] [17]. Both methodologies have been enhanced by computational advances, with chemogenomic profiling now enabling the prediction of drug-target interactions and mode of action through sophisticated bioinformatics analyses [18] [6].

Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions

Forward Chemogenomics

Forward chemogenomics, also termed "classical chemogenomics," is fundamentally a phenotype-to-target approach. This strategy begins with screening chemical compounds against a biological system to identify molecules that induce a specific phenotypic change of interest [1] [6]. The molecular basis of this desired phenotype is initially unknown, representing the key discovery challenge. Once active compounds (modulators) are identified through phenotypic screening, they serve as molecular tools to investigate and identify the protein(s) responsible for the observed phenotype [1]. For example, researchers might screen for compounds that arrest tumor growth and then use those hits to identify previously unknown cancer-relevant targets.

The major strength of forward chemogenomics lies in its unbiased nature, allowing for the discovery of novel biological pathways and therapeutic targets without preconceived hypotheses about specific molecular targets [1]. However, this approach faces the significant challenge of designing phenotypic assays that can efficiently transition from screening to target identification [1]. This typically requires sophisticated follow-up techniques, such as chemogenomic profiling in model organisms, to deconvolute the mechanism of action and identify the relevant molecular targets [6].

Reverse Chemogenomics

Reverse chemogenomics operates in the opposite direction as a target-to-phenotype approach. This methodology begins with a specific, well-characterized protein target and screens compound libraries using in vitro biochemical assays to identify modulators of its activity [1] [17]. Once active compounds are identified, their biological effects are analyzed in cellular systems or whole organisms to characterize the resulting phenotype and confirm the target's functional role [1].

This approach essentially mirrors the target-based strategies that have dominated pharmaceutical discovery over recent decades but enhances them through parallel screening capabilities and the ability to perform lead optimization across multiple targets within the same protein family [1]. Reverse chemogenomics benefits from its hypothesis-driven framework, as it begins with known targets of therapeutic interest, potentially yielding more straightforward paths to drug development [17]. The National Cancer Institute's "NCI-60" project, which used profiles of cellular response to drugs across 60 cell lines to classify small molecules by mechanism of action, exemplifies a reverse chemogenomics approach [6].

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between Forward and Reverse Chemogenomics

| Aspect | Forward Chemogenomics | Reverse Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Observable phenotype in biological system | Known protein target or gene sequence |

| Primary Screening Method | Phenotypic assays (cell-based or whole organism) | Target-based biochemical assays |

| Key Objective | Identify molecular target of phenotypic effect | Characterize biological function of known target |

| Hypothesis Framework | Hypothesis-generating | Hypothesis-testing |

| Information Flow | Phenotype → Target | Target → Phenotype |

| Typical Applications | Novel target discovery, drug repositioning | Lead optimization, target validation |

Screening Methodologies and Experimental Designs

Forward Chemogenomics Workflows

Forward chemogenomics employs systematic phenotypic screening to connect chemical compounds to biological functions. The experimental workflow typically begins with establishing a phenotypic assay that robustly captures a biologically or therapeutically relevant outcome. This may include assays measuring cell viability, morphological changes, metabolic activity, or organism-level responses [7]. For example, the "Cell Painting" assay provides a high-content morphological profiling platform that captures subtle phenotypic changes in response to chemical treatments across hundreds of cellular features [7].

Following primary screening, hit compounds that induce the desired phenotype are selected for target identification, which represents the most challenging phase of forward chemogenomics. Several methodologies have been developed for this purpose:

- Fitness-based chemogenomic profiling: In yeast models, this approach uses pooled collections of barcoded deletion strains grown competitively in the presence of a compound. Strains that show altered fitness (sensitivity or resistance) indicate genes involved in the compound's mechanism of action [6].

- Haploinsufficiency profiling (HIP): This method exploits heterozygous deletion strains where reduced gene dosage creates hypersensitivity to compounds targeting the deleted gene product, directly revealing potential drug targets [6].

- Expression-based profiling: Genome-wide RNA expression patterns in response to compound treatment can be compared to reference databases of genetic perturbations to infer mechanism of action [6].

Reverse Chemogenomics Workflows

Reverse chemogenomics employs target-centric screening approaches that begin with protein selection and progress through increasingly complex biological systems. The standard workflow initiates with target selection and validation, focusing on therapeutically relevant proteins, typically within defined families such as GPCRs, kinases, or nuclear receptors [1] [7]. The selected target is then subjected to high-throughput screening against compound libraries using biochemical assays that directly measure binding or functional modulation [17].

Following primary screening, confirmed hits undergo lead optimization through medicinal chemistry efforts to improve potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties. The optimized compounds are then evaluated in cellular assays to assess functional effects and preliminary toxicity. Finally, promising candidates progress to whole-organism studies to characterize phenotypic outcomes and therapeutic potential [1].

Recent advances in reverse chemogenomics have incorporated parallel screening across multiple related targets, enabling the rapid identification of selective versus promiscuous compounds early in the discovery process [1]. Additionally, computational approaches such as virtual high-throughput screening and proteochemometric modeling have enhanced efficiency by prioritizing compounds with higher likelihoods of activity [19].

Applications and Case Studies

Forward Chemogenomics in Action

Forward chemogenomics has demonstrated particular utility in identifying novel biological mechanisms and repurposing existing therapies. A compelling application involves elucidating the mode of action of traditional medicines, including Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ayurveda [1]. Researchers employed chemogenomic approaches to analyze compounds from these traditional systems, which often contain "privileged structures" with favorable bioavailability properties. Through target prediction programs and phenotypic associations, they identified potential mechanisms—for example, connecting sodium-glucose transport proteins and PTP1B to the hypoglycemic effects of "toning and replenishing" medicines [1].

In infectious disease research, forward chemogenomics has identified new antibacterial targets. One study capitalized on an existing ligand library for the bacterial enzyme MurD, involved in peptidoglycan synthesis. By applying the chemogenomic similarity principle, researchers mapped these ligands to other members of the Mur ligase family (MurC, MurE, MurF), identifying new targets for known ligands and proposing broad-spectrum Gram-negative inhibitors [1].

Another notable case employed fitness profiling in yeast to resolve a long-standing biochemical mystery—the identification of the enzyme responsible for the final step in diphthamide biosynthesis, a modified histidine residue on translation elongation factor 2. Using cofitness data from Saccharomyces cerevisiae deletion strains, researchers identified YLR143W as the strain with highest cofitness to known diphthamide biosynthesis genes, subsequently validating it as the missing diphthamide synthetase [1].

Reverse Chemogenomics Applications

Reverse chemogenomics excels in systematic target exploration and lead optimization across protein families. This approach has been extensively applied to kinase inhibitor development, where libraries of known kinase inhibitors are screened against panels of kinase targets to identify selective compounds and potential off-target effects [7]. Similar strategies have been implemented for GPCR-focused libraries and protein-protein interaction inhibitors [7].

In coronavirus drug discovery, reverse chemogenomics played a crucial role in identifying potential COVID-19 therapies. Researchers employed structure-based virtual screening against key viral targets like the main protease (Mpro) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) [19]. This approach facilitated the repurposing of existing antiviral drugs such as remdesivir (originally developed for Ebola) by demonstrating its activity against SARS-CoV-2 RdRp, despite later debates about its clinical efficacy [19].

The development of focused chemogenomic libraries represents another application of reverse chemogenomics. For example, researchers have constructed specialized libraries of approximately 5,000 small molecules representing diverse drug targets involved in various biological processes and diseases [7]. These libraries enable more efficient screening by enriching for compounds with favorable drug-like properties and known bioactivities, accelerating the identification of hits against specific target classes.

Table 2: Experimental Applications and Evidence Base

| Application Area | Forward Chemogenomics Evidence | Reverse Chemogenomics Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Novel Target Identification | Diphthamide synthetase discovery via yeast cofitness [1] | Kinase inhibitor profiling across target families [7] |

| Drug Repositioning | Traditional medicine mechanism elucidation [1] | COVID-19 drug repurposing (remdesivir) [19] |

| Infectious Disease | Mur ligase family target expansion [1] | SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor screening [19] |

| Technology Development | Cell Painting morphological profiling [7] | Targeted chemogenomic library design [7] |

| Chemical Biology | Natural product target deconvolution | Focused library screening against protein families [1] [7] |

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Successful implementation of chemogenomic approaches requires specialized experimental resources. The following table details key research reagents and their applications in forward and reverse chemogenomics studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemogenomics Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Yeast Deletion Collections | Competitive fitness profiling in forward chemogenomics; identification of drug targets through haploinsufficiency | Homozygous and heterozygous deletion collections [6] |

| Focused Chemical Libraries | Targeted screening against specific protein families; enriched hit rates for reverse chemogenomics | Kinase-focused libraries, GPCR-focused libraries [7] |

| Cell Painting Assay Kits | High-content morphological profiling for phenotypic screening in forward chemogenomics | BBBC022 dataset with 1,779 morphological features [7] |

| Chemogenomic Databases | Target prediction and mechanism analysis through bioactivity data mining | ChEMBL database, BindingDB, PDSP Ki database [18] [7] |

| Overexpression Libraries | Identification of resistance mechanisms and bypass pathways; complementary to deletion libraries | MoBY-ORF collection [6] |

Integrated Data Analysis and Interpretation

The power of both forward and reverse chemogenomics approaches is substantially enhanced through computational integration and cross-platform data analysis. Modern chemogenomics employs sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines to extract meaningful patterns from complex screening data, with particular emphasis on chemogenomic signature similarity analysis [6].

The underlying principle of this analysis is "guilt-by-association"—compounds with similar chemical-genetic profiles likely share similar mechanisms of action or target the same biological pathways [6]. This approach was pioneered in yeast systems, where genome-wide RNA expression profiles in response to compound treatment were used to create reference databases for mechanism prediction [6]. Similarly, fitness profiles from chemical-genetic screens of deletion strain collections can be clustered to identify functional relationships between compounds and their cellular targets [6].

In practice, researchers generate a chemogenomic profile for a compound of interest—whether from gene expression changes, fitness defects in deletion strains, or morphological features—and then query this against a reference database of profiles from compounds with known mechanisms [6]. The best matches suggest potential targets or mechanisms for the test compound. However, this approach requires careful interpretation, as reference databases are never fully comprehensive, and secondary evidence from complementary assays is often necessary to confirm predictions [6].

For quantitative binding affinity prediction, methods like random forest (RF) modeling have been employed to differentiate drug-target interactions from non-interactions based on integrated features from both compounds and proteins [18]. These models use chemical descriptors for drugs (e.g., chemical hashed fingerprints) and sequence-based descriptors for proteins (e.g., composition, transition, and distribution descriptors) to create predictive frameworks that can classify novel drug-target pairs with high confidence [18]. Such computational approaches have enabled the construction of drug-target interaction networks that provide system-level insights into drug action and potential therapeutic applications [18].

Forward and reverse chemogenomics represent complementary paradigms in contemporary drug discovery, each with distinct strengths and applications. Forward chemogenomics offers an unbiased, phenotype-driven approach that excels at novel target discovery and elucidating mechanisms of action for phenotypic screening hits. Conversely, reverse chemogenomics provides a targeted, hypothesis-driven framework ideal for lead optimization and systematic exploration of defined target families.

The integration of these approaches creates a powerful synergistic strategy for therapeutic development. Forward chemogenomics can identify novel biological pathways and unexpected drug targets, which can then be systematically exploited through reverse chemogenomics approaches. Furthermore, advances in computational prediction, chemical library design, and high-content screening technologies continue to enhance both methodologies [18] [7].

As chemogenomics continues to evolve, the convergence of these approaches through unified data analysis frameworks—particularly chemogenomic signature similarity analysis—promises to accelerate the identification of therapeutic targets and bioactive compounds. This integration, coupled with ongoing developments in chemical biology and systems pharmacology, positions chemogenomics as a cornerstone methodology for addressing the complexity of human disease and developing next-generation therapeutics.

From Data to Discovery: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

Modern chemogenomics, the systematic study of the interactions between small molecules and biological targets across the genome, relies heavily on advanced experimental platforms to elucidate complex biological relationships [20]. These platforms enable researchers to move beyond single-target studies to a systems-level understanding of how chemical perturbations affect cellular networks. Within this field, three distinct experimental platforms have become cornerstone methodologies: yeast engineering, mammalian CRISPR tool development, and pathogen-based metagenomic profiling. Each platform offers unique capabilities, performance characteristics, and applications that make them suitable for different aspects of chemogenomic signature analysis. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, detailing their performance metrics, experimental protocols, and integration into chemogenomic workflows, thereby offering researchers a foundation for selecting appropriate methodologies for specific investigational needs.

Platform Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize the key performance characteristics and applications of the three experimental platforms, based on current literature and experimental data.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics Across Experimental Platforms

| Platform | Primary Function | Max Efficiency/ Sensitivity Reported | Key Strengths | Throughput Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast CRISPR (LINEAR Platform) | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Genome Editing | 67-100% HDR rate [21] | High-precision editing without disrupting NHEJ; enables stable genomic integration [21] [22] | High (supports multiplexed and iterative editing) [22] |

| Mammalian CRISPR (Novel Repressors) | Transcriptional Repression (CRISPRi) | ~20-30% better knockdown than dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB) [23] | Reduced guide RNA dependency; preserved cell viability; reversible knockdown [23] | High (suited for genome-wide screens) [23] |

| Pathogen Profiling (mNGS) | Metagenomic Pathogen Detection | 71.8-71.9% sensitivity (Illumina vs. Nanopore) [24] | Culture-independent; detects bacteria, fungi, viruses simultaneously; rapid turnaround [24] | Variable (depends on sequencing technology and depth) [24] |

Table 2: Applications in Chemogenomics and Technical Considerations

| Platform | Primary Applications in Chemogenomics | Technical Complexity | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast CRISPR (LINEAR Platform) | Metabolic pathway engineering, functional genomics, heterologous gene expression [21] [22] | Moderate | Genotypic validation (PCR), phenotypic screening (e.g., production yields) [21] |

| Mammalian CRISPR (Novel Repressors) | Target validation, functional genetic screens, studying essential genes, disease modeling [23] | High | Transcriptomic data (RNA-seq), protein expression (flow cytometry, Western), phenotypic assays [23] |

| Pathogen Profiling (mNGS) | Identifying infectious triggers of disease, characterizing microbiome-drug interactions, antimicrobial resistance profiling [24] | High (specialized sequencing and bioinformatics) | Pathogen detection lists, taxonomic profiles, genomic coverage metrics [24] |

Yeast CRISPR Engineering Platform

The yeast CRISPR platform, particularly the repackaged LINEAR (lowered indel nuclease system enabling accurate repair) system, addresses a fundamental challenge in non-conventional yeasts: the competition between non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR) pathways [21]. Unlike conventional CRISPR platforms that disrupt NHEJ to favor HDR, LINEAR enhances HDR rates to 67-100% in various NHEJ-proficient yeasts while preserving the endogenous NHEJ pathway [21]. This is achieved by optimizing the timing and expression levels of Cas9 to align with the cell's natural repair cycle, thereby increasing the probability of successful homologous recombination. The platform's ability to perform precise edits and multiplexed integrations without selectable markers makes it invaluable for metabolic engineering and complex pathway assembly in yeast [22].

Key Experimental Protocol: Markerless Multiplex Integration

A critical application of the yeast CRISPR platform is the markerless integration of multiple genetic cassettes, which eliminates the need for recyclable markers and accelerates complex strain engineering [22]. The following protocol, adapted from the Ellis Lab toolkit, outlines this process:

- sgRNA Vector Construction: Clone target-specific spacer sequences (typically 20 nt) into the sgRNA entry vector (e.g., pWS082) using a Golden Gate assembly reaction. This vector contains a yeast tRNA promoter (e.g., tRNAPhe) for high expression and flanking HDV ribozyme sequences for precise processing [22].

- Linearization: Digest the assembled sgRNA vector with EcoRV to generate a linear expression cassette. This cassette possesses 500 bp homology arms for subsequent gap repair.

- Gap Repair Transformation: Co-transform the following into a yeast strain that has Cas9 stably integrated into its genome [22]:

- The linearized sgRNA cassette from Step 2.

- A linearized, gapped Cas9-sgRNA expression vector (e.g., from the pWS158-pWS182 series).

- One or more donor DNA fragments containing the desired genetic modifications flanked by homology arms (≥ 40 bp) to the genomic target sites.

- Selection and Screening: Plate the transformation mixture on solid medium lacking the appropriate nutrient to select for the marker on the Cas9-sgRNA vector (e.g., -Ura for pWS158). The successful gap repair of the sgRNA cassette and the Cas9 vector in vivo reconstitutes a stable plasmid.

- Validation: Screen individual colonies by colony PCR using primers that flank the genomic integration sites to verify correct insertion of the donor DNA. Sequencing of the modified locus is recommended to confirm precision edits.

This methodology leverages the cell's own high proficiency for homologous recombination in a subpopulation of cells, enabling highly efficient, markerless integration of genetic material [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Yeast CRISPR Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Yeast CRISPR Engineering

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description | Example (from Ellis Lab Toolkit) |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9-sgRNA Gap Repair Vectors | Expresses Cas9 and provides a scaffold for sgRNA integration. Vectors differ in promoters and markers. | pWS158 (pPGK1 promoter, URA3 marker), pWS160 (pRPL18B promoter, URA3 marker) [22] |