Chemogenomic Libraries vs. Diverse Compound Sets: A Strategic Analysis of Hit Rates in Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic choice between chemogenomic libraries and diverse compound sets for screening campaigns.

Chemogenomic Libraries vs. Diverse Compound Sets: A Strategic Analysis of Hit Rates in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic choice between chemogenomic libraries and diverse compound sets for screening campaigns. It explores the foundational principles of both approaches, detailing the design and application of target-focused libraries in complex phenotypic assays. The content delves into methodological considerations for library design, troubleshooting common challenges like target deconvolution and assay artifacts, and presents a comparative validation of hit rates and lead quality. Synthesizing current literature and case studies, this review serves as a guide for optimizing screening strategies to accelerate the identification of high-quality chemical starting points and first-in-class medicines.

The Resurgence of Phenotypic Screening and the Role of Focused Libraries

In the pursuit of new therapeutics, drug discovery scientists primarily employ two distinct strategies: target-based drug discovery (TDD) and phenotypic drug discovery (PDD). The fundamental distinction lies in the starting point and the level of biological understanding required. TDD begins with a hypothesis about a specific molecular target—typically a protein understood to play a key role in a disease mechanism. In contrast, PDD starts with a observation of a disease-relevant phenotype in a cell-based or whole-organism system, without requiring prior knowledge of the specific drug target [1] [2] [3].

The evolution of these strategies has been cyclical. Many early medicines were discovered serendipitously through their effects on physiology, a form of phenotypic observation. The molecular biology revolution then shifted focus to target-based approaches, but a resurgence in PDD occurred after an analysis revealed that a majority of first-in-class drugs approved between 1999 and 2008 were discovered without a predefined target hypothesis [1]. Today, both paradigms are recognized as complementary pillars of modern drug discovery, each with distinct strengths, weaknesses, and optimal applications.

Conceptual Frameworks and Strategic Differences

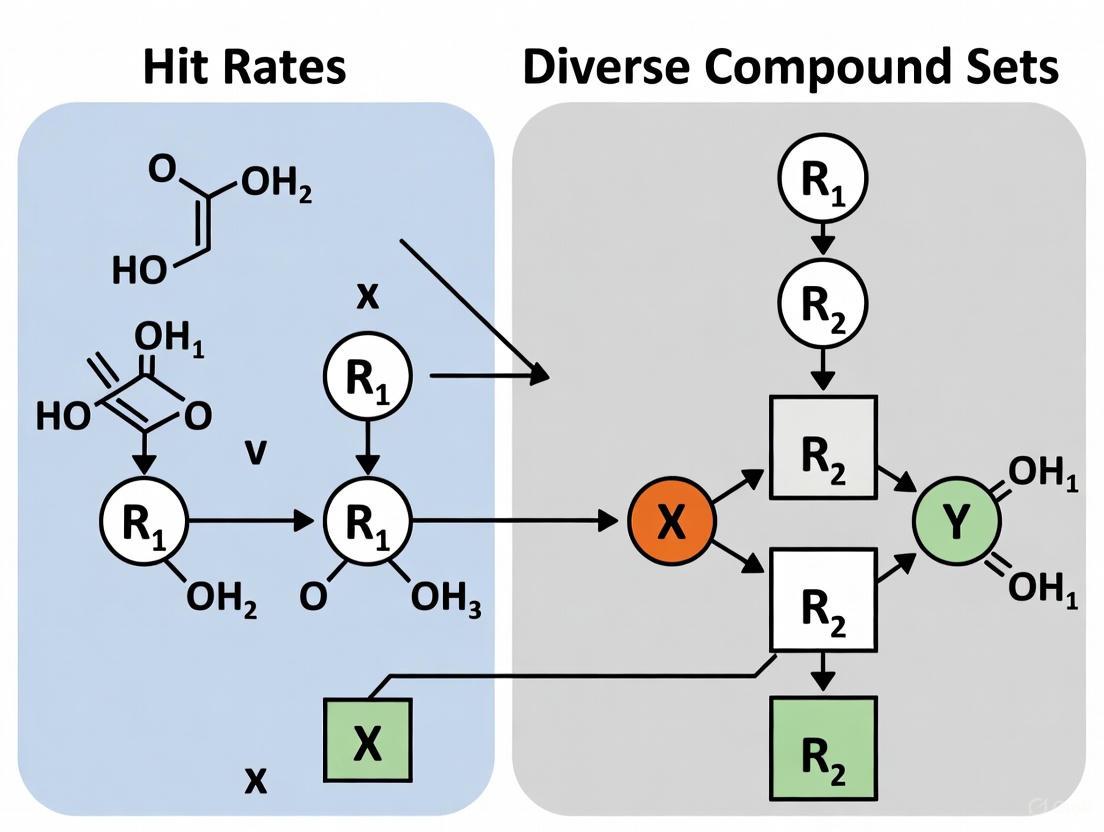

The core difference between these paradigms dictates every subsequent step in the early discovery workflow. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental processes for each approach.

Key Strategic and Philosophical Distinctions

Knowledge Dependency: TDD is a knowledge-driven approach. It requires validated hypotheses about a protein's causal role in a disease, making it suitable for well-characterized biological pathways. PDD is a biology-first, empirical approach. It is agnostic to the specific molecular target, making it powerful for exploring diseases with complex or poorly understood etiologies [1] [3].

Druggable Space: TDD is largely confined to the known "druggable genome"—proteins with binding pockets or active sites that small molecules can readily engage. PDD has consistently expanded the druggable target space by identifying drugs with unprecedented mechanisms of action (MoA), such as modulating protein folding, trafficking, or pre-mRNA splicing [1]. Examples include ivacaftor (CFTR potentiator) and risdiplam (SMN2 splicing modifier), whose MoAs were not preconceived [1].

Polypharmacology: TDD traditionally aims for high selectivity for a single target, though unintended polypharmacology (action on multiple targets) is common. PDD can intentionally discover compounds with a multi-target signature from the outset, which can be advantageous for treating complex, polygenic diseases like those of the central nervous system [1] [3].

Quantitative Comparison of Performance and Output

The strategic differences between TDD and PDD lead to distinct performance characteristics, success rates, and operational demands. The table below summarizes a direct comparison based on available data and historical analysis.

| Characteristic | Target-Based Discovery (TDD) | Phenotypic Discovery (PDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Defining Principle | Modulation of a predefined molecular target [3] | Observation of a therapeutic effect on a disease phenotype [1] |

| Knowledge Prerequisite | High: Requires a validated molecular hypothesis [3] | Low: Can proceed without a known target [3] |

| Typical Screening Assay | Biochemical binding or enzymatic activity assays [3] | Cell-based or whole-organism models of disease [1] [2] |

| Throughput & Cost | Generally high-throughput and cost-effective [3] | Often lower throughput and more resource-intensive [3] |

| Hit Optimization | Straightforward; guided by target structure and activity [3] | Challenging; requires iterative phenotypic testing [2] |

| Target Deconvolution | Not required (target is known) | Major challenge; requires significant investment [2] [4] |

| Strength in Producing | Best-in-class drugs for validated targets [3] | First-in-class drugs with novel mechanisms [1] [3] |

| Impact on Druggable Space | Exploits known target families | Expands druggable space to novel targets and mechanisms [1] |

Analysis of Strategic Value

The data indicates that the choice between TDD and PDD should be guided by the project's strategic goal. PDD has been a disproportional source of first-in-class medicines, as it is not constrained by prior target hypotheses and can reveal entirely new biology [1] [3]. Conversely, TDD is highly efficient for producing best-in-class drugs that improve upon a pioneering mechanism, allowing for precise optimization of potency and selectivity [3].

The most significant operational challenge in PDD is target deconvolution—identifying the specific molecular mechanism responsible for the observed phenotypic effect. This process can be technically demanding and time-consuming, though modern tools like chemogenomic libraries and computational profiling are improving success rates [4] [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for a Phenotypic Screening Campaign

A robust phenotypic screening campaign involves multiple, carefully designed stages to ensure the discovery of physiologically relevant hits.

Disease Model Selection and Validation: The foundation of a successful PDD campaign is a physiologically relevant and robust disease model.

- Model Types: These can range from primary cell cultures and co-culture systems to patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and more complex 3D organoids or microphysiological systems ("organs-on-chips") [2] [4].

- Key Consideration: The model must faithfully capture key aspects of the human disease pathology. The concept of a "chain of translatability"—ensuring a logical and predictive connection from the assay system to human disease—is critical for derisking later-stage development [2].

Phenotypic Assay Development and Readout: An assay is designed to quantitatively measure a disease-relevant phenotype.

- Readout Technologies: Common methods include high-content imaging (e.g., the Cell Painting assay), transcriptomic profiling, and measurements of secreted biomarkers [5]. High-content imaging extracts hundreds of morphological features from stained cells, creating a rich profile for each compound [5].

Compound Library Selection and Screening: The choice of library is a key strategic decision.

- Diverse Compound Sets: Large libraries (>100,000 compounds) designed for maximum chemical diversity are used for de novo lead discovery [6].

- Chemogenomic Libraries: Smaller, focused collections (~1,600-5,000 compounds) of well-annotated, target-specific probes are powerful for mechanistic studies and target identification [6] [7] [5]. These libraries cover a significant portion of the druggable proteome and provide immediate clues to potential mechanisms if a probe compound yields a hit.

Hit Triage and Validation: This critical step prioritizes hits for further investment.

- The "Rule of 3": A practical framework suggests using at least three orthogonal assays to validate phenotypic hits, ensuring the effect is robust and not an artifact of the primary screen [2].

- Counterscreening: Hits are tested in assays designed to identify undesirable mechanisms, such as general cytotoxicity or non-specific assay interference.

Target Deconvolution and MoA Elucidation: This is the process of identifying the molecular target(s) responsible for the phenotypic effect.

- Methods: Techniques include affinity purification using chemical probes, genetic approaches like CRISPR-based screening, and computational methods that compare the compound's phenotypic or transcriptomic signature to databases of known profiles (e.g., Connectivity Map) [1] [8] [9]. Newer computational approaches, such as the DrugReflector model, use active learning to iteratively improve the prediction of compounds that induce desired phenotypic changes from transcriptomic data [9].

Protocol for a Target-Based Screening Campaign

The workflow for TDD is more linear, as the target is known from the outset.

- Target Selection and Validation: A protein is chosen based on strong genetic or pharmacological evidence of its causal role in the disease.

- Assay Development: A biochemical assay is developed that measures the compound's ability to bind to or modulate the activity of the purified target protein (e.g., an enzyme inhibition assay).

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): A large, diverse compound library is screened against the target assay. This step is typically highly automated.

- Hit-to-Lead Optimization: Confirmed hits are optimized by medicinal chemists. Structure-activity relationship (SAR) cycles are guided by the biochemical assay and often by high-resolution structural data (e.g., X-ray crystallography) of the target.

- Cellular and In Vivo Testing: Optimized lead compounds are then tested in cellular models to confirm target engagement and functional activity, followed by evaluation in animal models of disease.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of both discovery paradigms relies on access to high-quality, well-characterized research tools. The following table details key reagents, with a particular focus on resources for phenotypic screening and chemogenomics.

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Drug Discovery | Key Features & Context of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Chemogenomic Library | A collection of well-annotated, selective compounds used for phenotypic screening and target deconvolution [6] [7] [5]. | Covers 1,000-2,000 known drug targets [8]. Enables hypothesis-driven MoA investigation. Examples: EUbOPEN library, BioAscent's probe library [6] [7]. |

| Diversity Compound Library | A large collection of chemically diverse compounds used for de novo lead discovery in both TDD and PDD [6]. | Typically 100,000+ compounds. Used for unbiased screening when no prior chemical starting point exists. |

| Cell Painting Assay | A high-content, image-based morphological profiling assay used for phenotypic screening and MoA characterization [5]. | Stains 8 cellular components, yielding ~1,700 morphological features. Used to create a "fingerprint" for compound MoA. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Tools | Functional genomics platform for gene knockout, activation, or inhibition in genetic screens [8]. | Used for target validation and identification of synthetic lethal interactions (e.g., PARP inhibitors in BRCA-mutant cancers [8]). |

| iPSC-Derived Cells | Patient-specific disease modeling for physiologically relevant phenotypic screening [2] [4]. | Provides a human, disease-in-a-dish model for complex disorders. |

The debate between target-based and phenotypic drug discovery is not a binary choice but a question of strategic alignment. PDD offers a powerful, unbiased path to novel biology and first-in-class therapies, particularly for diseases with complex or unknown etiologies, as evidenced by its track record [1] [3]. Its primary challenges are operational: more complex assays and the difficult task of target deconvolution. TDD offers a rational, efficient, and optimized path for pursuing validated targets, leading to best-in-class drugs, but is constrained by the current limits of biological knowledge [3].

The future of drug discovery lies in the flexible and integrated application of both paradigms. The resurgence of PDD, powered by advances in disease modeling (e.g., iPSCs, microphysiological systems), chemogenomic libraries, and sophisticated computational tools for MoA prediction, is expanding the druggable universe [9] [4]. Initiatives like the EUbOPEN consortium and Target 2035, which aim to provide high-quality chemical probes for the human genome, are systematically building the foundational tools that will empower both TDD and PDD campaigns [7]. By understanding the strengths, limitations, and optimal applications of each approach, drug discovery professionals can more strategically assemble project portfolios, leveraging the best tools from both paradigms to accelerate the delivery of new medicines to patients.

What is a Chemogenomic Library? Annotated Compounds for Mechanism-Based Screening

In the evolving landscape of drug discovery, the tension between phenotypic screening's disease relevance and target-based screening's mechanistic clarity presents a significant challenge. Chemogenomic libraries have emerged as a powerful solution to this dilemma, serving as a strategic bridge between these two approaches. A chemogenomic library is a systematically curated collection of small molecules characterized by well-annotated targets and mechanisms of action [10] [11]. Unlike diverse compound sets selected primarily for structural variety, chemogenomic libraries consist of selective pharmacological agents designed to modulate specific protein families or biological pathways [12].

The fundamental premise of chemogenomics is the systematic screening of targeted chemical libraries against distinct drug target families—such as GPCRs, kinases, nuclear receptors, and proteases—with the dual objective of identifying novel therapeutic compounds and elucidating the functions of previously uncharacterized targets [10]. This approach leverages the principle that ligands designed for one family member often exhibit activity against related proteins, enabling comprehensive coverage of target families with minimized screening efforts [10]. The strategic application of these libraries is particularly valuable in phenotypic drug discovery (PDD), where observable phenotypic changes can be rapidly connected to potential molecular targets through the library's annotation database [5] [13].

Library Composition and Design Strategies

Core Characteristics and Annotation Standards

The construction of a high-quality chemogenomic library requires rigorous curation and annotation standards. These libraries typically contain compounds with defined potency and selectivity profiles against specific target classes [11]. According to EUbOPEN initiatives, while ideal chemical probes demonstrate exquisite selectivity, chemogenomic compounds may exhibit broader polypharmacology, which paradoxically enhances their utility for covering larger target spaces when highly selective probes are unavailable [11].

Commercial and academic chemogenomic libraries vary in size and focus. For instance, BioAscent offers a library of over 1,600 diverse, well-annotated pharmacologically active probe molecules [14], while ChemDiv provides a curated ChemoGenomic Annotated Library specifically for phenotypic screening applications [12]. These libraries are organized into subsets covering major target families such as protein kinases, membrane proteins, and epigenetic regulators [11].

Table 1: Typical Composition of Commercial Chemogenomic Libraries

| Library Characteristic | BioAscent Chemogenomic Library | ChemDiv Annotated Library | Typical Academic Collections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Compounds | 1,600+ selective probes | Not specified | 1,200-5,000 compounds |

| Target Coverage | Diverse pharmacological agents | Annotated targets for phenotype interpretation | 1,300+ anticancer proteins |

| Primary Application | Phenotypic screening & mechanism of action studies | Phenotypic screening with target identification | Precision oncology, patient-specific vulnerabilities |

| Key Features | Highly selective, well-annotated | Target involvement suggested by hits | Focused on specific disease areas |

Design Strategies for Targeted Coverage

Effective chemogenomic library design employs sophisticated strategies to maximize target coverage while maintaining practical screening sizes. For precision oncology applications, researchers have developed systematic approaches that consider library size, cellular activity, chemical diversity, availability, and target selectivity [15]. These strategies have yielded minimal screening libraries of approximately 1,200 compounds capable of targeting over 1,300 anticancer proteins [15].

The analytical procedures for library design prioritize compounds with demonstrated cellular activity and defined mechanism of action, ensuring biological relevance [15]. Additionally, scaffold-based diversity is a critical consideration, with some libraries containing thousands of distinct Murcko scaffolds and frameworks to ensure structural variety while maintaining target focus [14]. This balanced approach enables researchers to cover extensive biological space with limited compound numbers, making these libraries particularly suitable for complex phenotypic assays with limited throughput capacity [16].

Experimental Applications and Workflows

Screening Protocols and Methodologies

The application of chemogenomic libraries follows two principal screening paradigms: forward chemogenomics (phenotype-first) and reverse chemogenomics (target-first) [10]. In forward chemogenomics, researchers screen for compounds that induce a specific phenotypic change in cells or organisms without preconceived notions of the molecular targets involved [10]. Once active compounds are identified, their annotated targets provide immediate hypotheses about the molecular mechanisms responsible for the observed phenotype.

Conversely, reverse chemogenomics begins with compounds known to modulate specific targets in biochemical assays, then evaluates their effects in cellular or organismal contexts to validate the target's role in biological responses [10]. This approach has been enhanced through parallel screening capabilities and lead optimization across multiple targets within the same family [10].

The experimental workflow typically involves several critical stages, as illustrated below:

Advanced Profiling Technologies

Contemporary chemogenomic screening increasingly incorporates advanced profiling technologies that provide multidimensional data for enhanced mechanism elucidation. High-content imaging approaches, particularly the Cell Painting assay, have emerged as powerful tools for characterizing compound-induced morphological profiles [5]. This technique uses automated microscopy and image analysis to quantify hundreds of morphological features across multiple cellular compartments, generating distinctive "morphological fingerprints" for different mechanism-of-action classes [5].

Complementary technologies such as DRUG-seq and Promotor Signature Profiling provide transcriptomic insights that reinforce and expand on morphological findings [16]. The integration of these profiling data with target annotation databases in network pharmacology platforms creates system-level understanding of compound activities [5]. For example, researchers have developed Neo4j-based graph databases that integrate drug-target-pathway-disease relationships with morphological profiling data, enabling sophisticated querying and hypothesis generation [5].

Performance Comparison: Chemogenomic vs. Diverse Compound Libraries

Hit Rate and Quality Metrics

When compared to diverse screening collections, chemogenomic libraries demonstrate distinct performance characteristics that make them particularly valuable for specific discovery scenarios. While diversity libraries excel at identifying novel chemotypes through broad screening, chemogenomic libraries typically yield higher-quality hits with more straightforward mechanistic interpretation [14] [13].

Evidence from screening campaigns demonstrates this performance differential. In one assessment, a 5,000-compound diversity subset screened against 35 diverse biological targets—including enzymes, GPCRs, and phenotypic cell assays—produced high-quality hits across these varied target classes [14]. However, the hit confirmation and target identification phases typically required significantly more resources compared to chemogenomic library hits, where target annotations are immediately available for mechanistic hypothesis generation [13].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Library Types in Phenotypic Screening

| Performance Metric | Chemogenomic Libraries | Diverse Compound Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Hit Rate | Variable, but hits are typically higher quality and more interpretable | Dependent on library diversity and assay design |

| Target Identification | Immediate hypotheses via annotation database | Requires extensive deconvolution efforts |

| Mechanistic Insight | Direct from annotated targets | Must be established through follow-up studies |

| Project Transition | Rapid progression from phenotype to target-based optimization | Longer path to mechanistic understanding |

| Coverage | Limited to annotated target space but expanding | Broad but includes unknown targets |

Applications in Complex Disease Models

The value proposition of chemogenomic libraries becomes particularly compelling in complex disease contexts with limited screening capacity. In central nervous system (CNS) drug discovery, for example, researchers must balance clinical relevance with practical screening constraints [17]. Phenotypic assays modeling neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and other CNS pathologies have successfully employed chemogenomic libraries to identify clinically translatable compounds while maintaining manageable screen sizes [17].

In precision oncology applications, researchers have designed targeted libraries specifically for profiling patient-derived glioblastoma stem cells [15]. These focused collections of 789-1,211 compounds covering thousands of anticancer targets successfully identified patient-specific vulnerabilities and revealed highly heterogeneous phenotypic responses across patients and cancer subtypes [15]. This approach demonstrates how strategically designed chemogenomic libraries can extract maximal biological insight from precious patient-derived materials with limited scalability.

Implementation and Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Successful implementation of chemogenomic screening requires specific research reagents and platforms. The following table outlines key components of a typical chemogenomic screening workflow:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomic Screening

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Example Sources/Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Annotated Compound Libraries | Collection of pharmacologically active compounds with known targets | BioAscent (1,600+ compounds), ChemDiv Annotated Library, EUbOPEN collections |

| Cell Painting Assay | High-content morphological profiling using multiplexed fluorescence | Broad Institute BBBC022 dataset protocol |

| Graph Databases | Integration of drug-target-pathway-disease relationships | Neo4j with ChEMBL, KEGG, GO annotations |

| Gene Expression Profiling | Transcriptomic analysis of compound effects | DRUG-seq, Promotor Signature Profiling |

| Target Prediction Tools | In silico analysis of potential targets | ClusterProfiler, DOSE for enrichment analysis |

Emerging Innovations and Future Directions

The field of chemogenomics continues to evolve with several emerging trends expanding its capabilities. Gray Chemical Matter (GCM) represents a novel approach to identifying compounds with likely novel mechanisms of action by mining existing high-throughput screening data [16]. This methodology focuses on chemical clusters exhibiting "dynamic SAR" (structure-activity relationship) across multiple assays, enabling the identification of bioactive compounds with potential novel targets not currently represented in standard chemogenomic libraries [16].

Additionally, fragment-based approaches are emerging as alternatives to conventional chemogenomic libraries, particularly for CNS drug discovery where blood-brain barrier penetration is critical [17]. These fragment libraries, combined with structural biology and biophysical screening techniques like surface plasmon resonance (SPR), offer alternative paths to identifying novel chemical starting points with more straightforward target deconvolution pathways [17].

The integration of chemical proteomics and artificial intelligence with chemogenomic screening represents another frontier, enhancing target identification capabilities for phenotypic hits [17]. These technologies promise to accelerate the often challenging process of connecting compound-induced phenotypes to molecular targets, particularly for complex biological systems and disease models.

Chemogenomic libraries represent a sophisticated toolset that strategically bridges phenotypic and target-based drug discovery paradigms. Through their carefully curated composition and detailed annotation, these libraries offer researchers the unique ability to extract mechanistic insights from phenotypic observations while maintaining practical screening scales. As drug discovery increasingly focuses on complex diseases and personalized therapeutic approaches, the targeted nature of chemogenomic libraries provides an efficient path to identifying and validating novel therapeutic hypotheses. The continued expansion of target coverage, integration with advanced profiling technologies, and development of innovative library design strategies will further enhance the value of these resources in addressing the most challenging problems in biomedical research.

In the pursuit of new therapeutics, drug discovery teams face a critical decision at the project's outset: what type of compound library to screen. The choice between diverse libraries, designed to cover a broad swath of chemical space, and focused libraries, designed around specific protein targets or families, has profound implications for efficiency, cost, and success. A growing body of evidence, particularly within chemogenomic library research, demonstrates that target-focused screening strategies offer a superior value proposition by delivering significantly higher hit rates and more chemically tractable starting points compared to diversity-based screening.

Defining the Libraries: A Head-to-Head Comparison

A target-focused library is a collection of compounds designed or assembled with a specific protein target or protein family in mind, utilizing structural, chemogenomic, or known ligand data [18]. In contrast, diversity-based libraries are assembled to maximize structural variety and coverage of chemical space, operating on the principle that structurally similar compounds have similar properties [19] [20].

The table below summarizes the core distinctions between these two approaches.

| Feature | Focused Libraries | Diverse Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Design Principle | Knowledge-based (structure, sequence, ligands) [18] | Similar property principle; maximize coverage of chemical space [19] [20] |

| Primary Application | Targets with existing structural or ligand data (e.g., kinases, GPCRs) [18] [20] | Novel targets with limited prior knowledge or phenotypic screening [19] [20] |

| Typical Hit Rate | Higher | Lower |

| Key Advantage | Efficient resource use, richer initial SAR [18] | Broad exploration, potential for novel mechanisms [20] |

Quantitative Evidence: Focused Libraries Outperform

The theoretical advantages of focused libraries are borne out by empirical data. A landmark case study from BioFocus, a pioneer in commercial focused libraries, reported that its SoftFocus libraries led to over 100 client patent filings and contributed directly to several clinical candidates [18]. These libraries consistently yielded higher hit rates than diverse collections, providing potent and selective starting points that reduce subsequent hit-to-lead timelines [18].

More recently, a sophisticated multivariate chemogenomic screen for antifilarial drugs provides compelling comparative data. Researchers screened a library of 1,280 bioactive compounds against B. malayi microfilariae. This target-focused chemogenomic library, where each compound was linked to a validated human target, achieved a >50% hit rate after thorough dose-response characterization [21]. This exceptionally high success rate showcases the power of leveraging existing bioactivity knowledge to enrich a screening library, dramatically increasing the probability of identifying potent, tool-like compounds.

Experimental Workflow: Implementing a Focused Screen

The practical application of a focused screening approach, as exemplified by the antifilarial drug discovery campaign, involves a tiered, multi-phenotype strategy [21]. The workflow below visualizes this process.

Diagram of the tiered screening workflow using a focused chemogenomic library that led to a high confirmed hit rate [21].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The high-value screening workflow above was executed through the following detailed methodologies [21]:

Primary Bivariate Screen: The initial screen against microfilariae was performed at a 1 µM compound concentration. It simultaneously measured two phenotypic endpoints: motility at 12 hours post-treatment (using video recording and analysis) and viability at 36 hours post-treatment (using an optimized ATP-based luminescence assay). A Z-score >1 for either phenotype identified a hit.

Hit Validation: Initial hits were progressed to an 8-point dose-response curve, again measuring motility and viability. Compounds were required to show a >25% reduction in viability or motility compared to controls at 36 hours to be considered confirmed hits.

Secondary Multiplexed Adult Assay: Confirmed hits were advanced to a lower-throughput, high-content screen against adult parasites. This assay was multiplexed to characterize compound activity across multiple fitness traits, including neuromuscular control, fecundity, metabolism, and viability, providing a rich dataset for lead prioritization.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and resources essential for conducting high-quality focused library screens, as drawn from the cited research.

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Screening | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Target-Focused Libraries | Pre-designed compound sets enriched for specific target families (e.g., kinases, GPCRs) [18]. | SoftFocus Libraries [18]; EUbOPEN Chemogenomic Library [7]. |

| Chemogenomic Libraries | Collections of bioactive compounds linked to known targets; enable target discovery and validation [21]. | Tocriscreen 2.0 library [21]. |

| Validated Chemical Probes | High-quality, potent, and selective small molecule modulators; the gold standard for tool compounds [7]. | EUbOPEN peer-reviewed probes (e.g., for E3 ligases, SLCs) with negative controls [7]. |

| Phenotypic Assay Systems | Biologically relevant systems for evaluating compound effects in a non-target-based manner. | Patient-derived cells [7]; B. malayi microfilariae and adult parasites [21]. |

The evidence from both historical success stories and cutting-edge research makes a compelling case for the value proposition of focused libraries. When knowledge of a target or target family exists, screening a focused or chemogenomic library is a superior strategy. It consistently delivers higher hit rates, more rapidly exploitable structure-activity relationships, and a faster, more efficient path to qualified leads and clinical candidates [18] [21]. For drug discovery projects aiming to optimize resources and accelerate timelines, a focused screening approach represents a rational and high-value choice.

A fundamental challenge in modern drug discovery is the stark disparity between the vastness of the human proteome and the fraction of it that can be targeted with small-molecule therapeutics. This shortfall, termed the 'ligandable proteome gap', represents a significant bottleneck in the development of chemical probes and drugs for many disease-relevant proteins. While genomic and genetic technologies have successfully identified a diverse array of proteins with compelling disease associations, a large number of these proteins reside in structural or functional classes that have historically resisted small-molecule development [22]. The core of this challenge lies in ligandability—the ability of a protein to bind small molecules with high affinity—which is not a universal property. Proteins lacking well-defined, druggable pockets are often deemed "undruggable," creating a critical gap between biological understanding and therapeutic intervention [22]. This guide objectively compares the performance of two primary strategies employed to bridge this gap: screening diverse compound sets versus using focused chemogenomic libraries, providing experimental data and methodologies to inform research planning.

Comparing Strategic Approaches to Expand Ligandability

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, performance data, and ideal use cases for the two main approaches to ligand discovery.

| Approach | Library Design & Description | Key Performance Data | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diverse Compound Sets & ABPP | Library: Diverse fragments or electrophilic scouts. Method: Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) in native biological systems [22]. | Coverage: Maps interactions across thousands of proteins [22]. Ligandability: Identified >170 stereoselective protein-fragment interactions in cells [23]. | Target-agnostic: Discovers ligands for uncharacterized proteins [22]. Native Environment: Accounts for cellular regulation and complex formation [22]. | Lower Throughput: High-content but not high-throughput; screens 100s-1000s of compounds [22]. Complex SAR: Requires careful structure-activity relationship (SAR) excavation [23]. |

| Focused Chemogenomic Libraries | Library: Compounds focused on a specific target class (e.g., kinases). Method: Target-based High-Throughput Screening (HTS) [24]. | Hit Rate: Consistently higher hit rates for well-studied target classes; kinase-focused libraries improved hit rates in 89% of cases [24]. Efficiency: More cost-effective per campaign for established protein families [24]. | Efficiency: Streamlined for target classes with known pharmacophores [24]. Rich SAR: Exploits known structure-ligand interactions for optimization [24]. | Limited Scope: Poor for novel or less-studied target classes [24]. Assay Dependency: Requires purified, formatted proteins, which can be problematic for some targets [23]. |

Experimental Protocols for Ligandability Assessment

Enantioprobe-Based Chemoproteomic Mapping

This protocol, derived from the "enantioprobe" strategy, is designed to identify stereoselective small molecule-protein interactions in native cellular environments, providing a robust method for validating genuine ligandability [23].

- Cell Treatment: Treat human cells (e.g., HEK293T or primary PBMCs) with a pair of enantiomeric, fully functionalized fragment (FFF) probes—the (R)- and (S)-enantiomers—that differ only in absolute stereochemistry. A typical concentration is 20-200 μM for 30 minutes [23].

- Photo-Crosslinking: Expose the treated cells to UV light (365 nm, 10 minutes) to activate the diazirine group on the bound probes, covalently capturing the reversible protein-fragment interactions [23].

- Cell Lysis and Click Chemistry: Harvest and lyse the cells. Conjugate an azide-biotin tag to the alkyne-handle of the probe-modified proteins using copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) chemistry [23].

- Streptavidin Enrichment: Isulate the biotinylated, probe-labeled proteins using streptavidin beads [23].

- Quantitative Proteomic Analysis: Process the enriched proteins and analyze them by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Use isotopic labeling (e.g., SILAC or reductive dimethylation) to quantitatively compare protein enrichment between the (R)- and (S)-enantiomer treatments. A protein is considered a stereoselective hit if it shows a >2.5-fold preferential enrichment by one enantiomer [23].

Competitive ABPP with Covalent Libraries

This method uses competitive Activity-Based Protein Profiling to map the interactions of covalent drugs or fragments across the proteome, identifying ligandable sites on diverse protein classes [22] [25].

- Sample Preparation: Use native cell or tissue lysates to preserve the proteome in its native state. Pre-treat the lysate with either a dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle (control) or the covalent drug/fragment of interest (typically 5 μM, 2 hours) [25].

- Probe Labeling: Treat the pre-incubated lysates with a broad-spectrum, cysteine-reactive activity-based probe (e.g., IPM probe: 2-iodo-N-(prop-2-yn-1-yl) acetamide). This probe will label reactive, ligandable cysteine residues that were not engaged by the test compound [25].

- Protein Digestion and Enrichment: Digest the probe-labeled proteins into tryptic peptides. Conjugate the alkyne-bearing peptides to an isotopically labeled biotin tag via CuAAC "click chemistry" and enrich them using streptavidin beads [25].

- LC-MS/MS and Data Analysis: Identify and quantify the enriched peptides using LC-MS/MS. The level of target engagement by the test compound is measured by the reduction in probe labeling (MS1 chromatographic peak ratio: RH/L = RDMSO:drug) for each cysteine-containing peptide. Cysteines with an RH/L ≥ 4 (indicating ≥75% reduction in probe labeling) are considered engaged [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Successful ligandability mapping requires specialized chemical tools and reagents. The table below details essential components for these experiments.

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Fully Functionalized Fragments (FFFs) | Serve as the variable recognition element to probe protein interactions; contain a photoreactive group and alkyne handle [23]. | Minimized constant region; variable fragment scaffolds; diazirine photo-crosslinker; alkyne for bioorthogonal tagging [23]. |

| Enantioprobe Pairs | Paired FFFs differing only in stereochemistry; control for physicochemical properties to identify stereoselective, authentic binding events [23]. | (R)- and (S)-enantiomers; identical overall protein labeling profile except at specific binding pockets [23]. |

| Broad-Spectrum Cysteine Probe (e.g., IPM) | Reacts with ligandable cysteine residues across the proteome in competitive ABPP; reports on compound engagement by displacement [25]. | Iodoacetamide warhead for cysteine reactivity; alkyne handle for downstream conjugation and enrichment [25]. |

| Click Chemistry Tags | Enable detection and enrichment of probe-labeled proteins post-experiment; link the probe to a reporter (e.g., biotin for MS, rhodamine for gel) [23] [25]. | Azide-functionalized rhodamine (for fluorescence) or isotopically labeled biotin (for proteomics) [23] [25]. |

| Quantitative MS Platforms | Identify and quantify enriched proteins or peptides; enable comparison between compound-treated and control samples [23] [25]. | Compatible with isotopic labeling techniques (SILAC, reductive dimethylation) for accurate quantification [23]. |

Performance Data from Key Studies

Quantitative Outcomes of Enantioprobe Screening

A landmark study using eight enantioprobe pairs in human cells provided concrete data on the scope of discoverable ligandable sites [23].

- Total Stereoselective Interactions Identified: 176 proteins [23].

- Cell Type Consistency: Proteins identified in both primary PBMCs and HEK293T cells generally showed consistent stereoselective profiles across cell types [23].

- Target Specificity: >80% of the proteins showing stereoselective interactions did so with only a single enantioprobe pair, demonstrating high specificity [23].

- Diversity of Targets: The engaged proteins spanned a wide range of structural and functional classes, including those that currently lack chemical probes [23].

Proteome-Wide Cysteine Ligandability Maps

A large-scale chemoproteomic analysis of 70 cysteine-reactive drugs quantified their engagement across the human cysteinome [25].

- Proteomic Coverage: The study quantified 18,918 cysteines from 7,170 proteins, representing extensive coverage of the human cysteinome [25].

- Overall Reactivity: The tested drugs engaged, on average, 4.8% of the quantified cysteines in cell lysates, indicating modest but widespread reactivity [25].

- Site Specificity: ~63% of the engaged proteins contained only a single engaged cysteine, and 55% of the engaged cysteines were associated with only one drug, highlighting site-specific recognition [25].

- Kinase Targeting: The mapping of engagement profiles onto the kinome tree revealed that a large number of kinases were engaged by at least one drug, showcasing the potential for target expansion within a druggable family [25].

Integrated Workflows and Future Outlook

The most powerful strategies for closing the ligandability gap may emerge from integrated workflows that leverage the strengths of both diverse and focused approaches. An initial, broad-scale ABPP screen with a diverse fragment or covalent library can identify promising ligandable sites on uncharacterized proteins. These hits can then be used as starting points to design focused, chemogenomic libraries for selective optimization, transforming a target-agnostic discovery into a targeted development campaign [22]. This synergy between expansive discovery and focused optimization represents a promising path forward. Furthermore, the continued development of novel covalent chemistries and ABPP reagents that target diverse amino acids beyond cysteine—such as lysine, tyrosine, and methionine—is systematically expanding the map of the ligandable proteome, offering new hope for targeting proteins once considered firmly "undruggable" [22].

Designing and Applying Target-Focused Libraries for Complex Assays

The strategic composition of small-molecule libraries is a critical determinant of success in early drug discovery. Within chemogenomic research, a fundamental tension exists between the use of large, structurally diverse compound sets to explore chemical space and the application of focused, target-oriented libraries to maximize hit rates against specific biological target classes. While large diverse libraries increase the probability of identifying novel chemotypes, their size often necessitates simplified biological assays, potentially missing complex phenotypic effects. Conversely, focused libraries enable sophisticated biological screening but risk constraining chemical diversity and target coverage. This guide objectively compares the performance of these divergent strategies, providing experimental data to inform library selection and design for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Data-driven analyses reveal that existing commercial and academic libraries vary dramatically in their performance on key metrics including target coverage, compound selectivity, and structural diversity [26]. The emergence of sophisticated cheminformatics tools now enables the systematic design of optimized libraries that balance these competing objectives. We present a comparative analysis of library design strategies, experimental validation data, and practical protocols to guide the construction of screening collections that maximize both target space coverage and chemical diversity.

Comparative Analysis of Library Design Strategies

Performance Metrics for Library Evaluation

Strategic library design requires careful evaluation across multiple performance dimensions. The table below summarizes key metrics for assessing library quality, their methodological basis, and optimal performance targets.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Compound Library Assessment

| Metric | Methodology | Optimal Target | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Coverage | Number of unique proteins inhibited with Ki/IC50 < 10 µM | Maximize coverage of target class or liganded genome | ChEMBL, proprietary profiling [26] |

| Compound Selectivity | Selectivity score based on off-target binding profiles | Minimal off-target overlap between library compounds | Kinome-wide screens (DiscoverX KINOMEscan, Kinativ) [26] |

| Structural Diversity | Tanimoto similarity of Morgan2 fingerprints (Tc) | Minimize frequency of structural clusters with Tc ≥ 0.7 | Chemical structure databases [26] |

| Polypharmacology | Assessment of binding to multiple protein targets | Controlled and well-annotated polypharmacology | Biochemical and cellular profiling data [26] |

| Clinical Relevance | Stage of clinical development of compounds | Inclusion of approved and investigational drugs | FDA approval packages, clinical trial databases [26] |

Experimental Comparison of Kinase Inhibitor Libraries

A systematic analysis of six widely available kinase inhibitor libraries reveals dramatic performance differences among existing collections [26]. The experimental data, derived from ChEMBLV22_1, international kinase profiling centers, and LINCS data, demonstrates how library design principles directly impact performance outcomes.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Kinase-Focused Libraries

| Library Name | Compound Count | Unique Compounds | Structural Diversity (Tc clusters ≥0.7) | Target Coverage Efficiency | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SelleckChem Kinase (SK) | 429 | ~50% | Intermediate | Moderate | Shared significant overlap with LINCS collection |

| Published Kinase Inhibitor Set (PKIS) | 362 | 350 (97%) | Low (extensive analog clusters) | Not reported | Designed with structural clusters for SAR studies |

| Dundee Collection | 209 | Not reported | High | Moderate | High structural diversity |

| EMD Kinase Inhibitor | 266 | Not reported | Intermediate | Moderate | Commercial library from Tocris Bioscience |

| HMS-LINCS (LINCS) | 495 | ~50% | High | High | Includes clinical-stage compounds |

| SelleckChem Pfizer (SP) | 94 | Not reported | Intermediate | Not reported | Licensed pharmaceutical compounds |

| LSP-OptimalKinase (Designed) | Not specified | Not applicable | Optimized | Highest | Outperforms existing collections in target coverage and compact size |

Experimental findings indicate that the HMS-LINCS and Dundee collections demonstrate the highest structural diversity, while the PKIS library was specifically designed with analog clusters to facilitate structure-activity relationship studies [26]. Perhaps most significantly, the analysis led to the creation of a newly designed LSP-OptimalKinase library that demonstrates superior performance in target coverage efficiency compared to any existing collection, highlighting the power of data-driven library design.

Data-Driven Library Design Methodologies

Cheminformatics Framework for Library Optimization

The data-driven approach to library design employs algorithms that optimize library composition based on binding selectivity, target coverage, induced cellular phenotypes, chemical structure, and clinical development stage [26] [27]. This methodology, available via the online tool http://www.smallmoleculesuite.org, assembles compound sets with minimal off-target overlap while maximizing target coverage.

The framework integrates four critical data types from ChEMBL and other sources: (1) chemical structure represented using Morgan2 fingerprints for similarity assessment; (2) target dose-response data from enzymatic assays with Ki or IC50 values; (3) target profiling data from large protein panels; and (4) phenotypic data from cell-based assays measuring morphological, biochemical, or functional responses [26]. Chemical structure matching using Tanimoto similarity of Morgan2 fingerprints ensures accurate compound annotation across different naming conventions (e.g., OSI-774, Erlotinib, and Tarceva) [26].

Experimental Protocol: Library Design and Validation

Objective: To design and validate an optimized kinase inhibitor library with enhanced target coverage and selectivity.

Methodology:

Data Compilation: Aggregate compound annotation data from ChEMBLV22_1, kinome-wide screens from the International Centre for Kinase Profiling, LINCS data, and in-house nominal target curation [26].

Structural Analysis: Calculate pairwise structural similarities using Tanimoto coefficients of Morgan2 fingerprints. Identify structural clusters with Tc ≥ 0.7 to quantify diversity [26].

Target Coverage Assessment: Map compounds to their protein targets using biochemical activity data (Ki/IC50 < 10 µM). Identify gaps in coverage across the kinome [26].

Selectivity Optimization: Apply algorithms to minimize off-target binding overlap between library compounds while maintaining coverage of primary targets [26].

Library Assembly: Select compounds that collectively maximize target coverage, maintain structural diversity, and include compounds at various clinical stages (preclinical to approved) [26].

Performance Validation: Compare the designed library against existing libraries using the metrics in Table 2, focusing on target coverage efficiency and selectivity profiles.

This protocol resulted in the creation of the LSP-OptimalKinase library, which demonstrated superior performance in target coverage compared to six widely used kinase inhibitor libraries [26]. Additionally, researchers applied this approach to develop an LSP-Mechanism of Action (MoA) library that optimally covers 1,852 targets in the liganded genome, defined as the subset of proteins in the druggable genome currently bound by at least three compounds with Ki < 10 µM [26] [27].

Phenotypic Profiling for Bioactivity Prediction

Cell Painting-Based Bioactivity Prediction

An alternative approach to library design and screening enrichment utilizes Cell Painting morphological profiles to predict bioactivity across diverse targets. This method employs deep learning models trained on Cell Painting images combined with single-concentration bioactivity data to predict compound activity across multiple assays [28].

Experimental Protocol:

Cell Painting Assay: Treat cells with compounds from a diverse library using an optimized high-content microscopy assay with six fluorescent dyes labeling nucleus, nucleoli, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, cytoskeleton, Golgi apparatus, plasma membrane, and RNA [28].

Bioactivity Data Collection: Extract single-point bioactivity data from HTS databases for each compound across multiple assays [28].

Model Training: Train a ResNet50 model (pretrained on ImageNet) in a supervised multi-task learning setup to predict bioactivity readouts for multiple assays using Cell Painting images as input [28].

Validation: Evaluate model performance using cross-validation, measuring ROC-AUC across diverse assays [28].

Experimental results demonstrate that this approach achieves an average ROC-AUC of 0.744 ± 0.108 across 140 diverse assays, with 62% of assays achieving ≥0.7 ROC-AUC, 30% ≥0.8, and 7% ≥0.9 [28]. The method is particularly effective for cell-based assays and kinase targets, and can maintain performance using only brightfield images instead of multichannel fluorescence [28]. This phenotypic profiling approach enables the creation of focused screening sets with maintained scaffold diversity while reducing screening campaign sizes by 70-80% without significant loss of active compounds [28].

Visualization of Library Design Strategies

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points and methodologies in strategic library design, highlighting the comparative advantages of different approaches.

Diagram 1: Strategic Library Design Workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The following table details key research reagents and computational tools essential for implementing the described library design and analysis methodologies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Library Design and Screening

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Data Resource | Curated bioactive molecules with drug-like properties | Source of compound-target annotations and activity data [26] |

| Cell Painting Assay | Experimental Assay | High-content morphological profiling using fluorescent dyes | Generation of phenotypic profiles for bioactivity prediction [28] |

| smallmoleculesuite.org | Software Tool | Data-driven library design and analysis | Creation of optimized libraries with minimal off-target overlap [26] [27] |

| DiscoverX KINOMEscan | Profiling Service | Kinase selectivity profiling | Assessment of compound selectivity and off-target effects [26] |

| Tanimoto Similarity (Morgan2) | Computational Algorithm | Structural similarity calculation | Quantification of chemical diversity within libraries [26] |

| REOS Filters | Computational Tool | Rapid Elimination Of Swill - removes compounds with undesirable properties | Library curation by eliminating reactive compounds [29] |

| Lipinski Rule of Five | Filter Criteria | Prediction of drug-likeness | Pre-selection of compounds with favorable physicochemical properties [29] |

Strategic library design represents a critical inflection point in modern drug discovery, directly impacting screening efficiency, resource allocation, and ultimate success rates. The experimental data presented demonstrates that data-driven library design approaches significantly outperform conventional collections in target coverage efficiency and selectivity. The LSP-OptimalKinase library achieves superior kinome coverage with fewer compounds than existing collections, while Cell Painting-based bioactivity prediction enables substantial screening enrichment while maintaining structural diversity.

For researchers operating under resource constraints, targeted libraries optimized for specific target classes provide the most efficient path to hit identification. Conversely, institutions with capacity for larger screening campaigns may benefit from diverse libraries that explore broader chemical space, particularly when augmented with phenotypic profiling approaches. Critically, the methodologies presented enable continuous library optimization as new compound and target data emerge, creating dynamic screening resources that evolve with scientific understanding. By adopting these strategic design principles, research organizations can significantly enhance their drug discovery efficiency and success rates.

Protein kinases represent one of the most important families of therapeutic targets in modern drug discovery, with particular significance in oncology, inflammation, and metabolic diseases [18] [30]. The development of kinase-focused compound libraries has emerged as a strategic response to the challenges of traditional high-throughput screening (HTS), offering the potential for higher hit rates, more relevant chemical starting points, and reduced resource expenditure [18]. This case study examines the structural data-driven approach to kinase-focused library design, with particular focus on the KinFragLib library, and objectively compares its performance, methodology, and applications against alternative strategies within the broader context of chemogenomic library hit rates versus diverse compound sets research.

The fundamental premise of target-focused libraries is that screening collections designed with specific protein families in mind yield superior results compared to diverse compound sets. As noted in foundational research on target-focused libraries, "the premise of screening such a library is that fewer compounds need to be screened in order to obtain hit compounds" and "it is generally the case that higher hit rates are observed when compared with the screening of diverse sets" [18]. This approach has led to numerous success stories, including more than 100 patent filings and several clinical candidates derived from focused library screening campaigns [18].

Library Design Methodologies: Structural Data versus Alternative Approaches

Structural Data-Driven Design: The KinFragLib Approach

KinFragLib represents a sophisticated, data-driven approach to kinase-focused library design that leverages the extensive structural information available for kinase-inhibitor complexes in the KLIFS database [31]. The methodology employs a systematic fragmentation strategy that deconstructs known kinase inhibitors into chemically meaningful fragments assigned to specific binding subpockets.

Core Experimental Protocol: The KinFragLib design workflow involves several meticulously executed steps:

Data Collection: The process begins with harvesting structural data from the KLIFS database (Kinase-Ligand Interaction Fingerprints and Structures), which contains curated information on kinase-ligand complexes from the Protein Data Bank [31]. The current implementation uses KLIFS data downloaded on December 6, 2023.

Structure Selection: The library focuses on DFG-in structures with non-covalent ligands, ensuring consistency in binding mode analysis [31].

Subpocket Definition: Each kinase binding pocket is algorithmically divided into six distinct subpockets based on defined pocket-spanning residues:

- Adenine pocket (AP)

- Front pocket (FP)

- Solvent-exposed pocket (SE)

- Gate area (GA)

- Back pocket 1 (B1)

- Back pocket 2 (B2) [31]

Ligand Fragmentation: Co-crystallized ligands are fragmented using the BRICS (Breaking of Retrosynthetically Interesting Chemical Substructures) algorithm, which identifies chemically meaningful cleavage points based on potential synthetic accessibility [31].

Fragment Assignment: The resulting fragments are assigned to the specific subpockets they occupy in the parent ligand structure, creating a mapped collection of fragments with known binding preferences [31].

Library Extension: The platform includes CustomKinFragLib, which provides a pipeline for filtering fragments based on unwanted substructures (PAINS and Brenk et al.), drug-likeness (Rule of Three and QED), synthesizability, and pairwise retrosynthesizability [31].

The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive workflow:

Alternative Design Strategies

Kinase-focused library design encompasses multiple methodologies beyond structural data-driven fragmentation:

Ligand-Based Design: This approach utilizes known kinase inhibitors to build pharmacophore models or perform similarity searches. Life Chemicals' Kinase Focused Library exemplifies this method, employing "2D fingerprint similarity search (Tanimoto coefficient > 0.85)" against a reference set of protein kinase modulators from the ChEMBL database [30].

Docking-Based Design: This method involves computationally docking potential scaffolds into representative kinase structures. As described in earlier kinase library design work, this strategy evaluates scaffolds by "docking them into a representative subset of kinases" chosen to represent different protein conformations and ligand binding modes [18].

Binding Mode-Specific Design: Some libraries specifically target distinct kinase binding modes, such as hinge binding, DFG-out binding, and invariant lysine binding, acknowledging the diverse conformational states accessible to kinase domains [18].

Performance Comparison: Hit Rates and Chemical Space Coverage

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The table below summarizes key performance indicators for structural data-driven kinase libraries compared to alternative approaches:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Kinase-Focused Library Design Strategies

| Library Characteristic | Structural Data-Driven (KinFragLib) | Ligand-Based Similarity | Docking-Based Design | Diverse Compound Sets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Hit Rate | Not explicitly quantified but designed for "higher hit rates" [18] | Not explicitly quantified | Not explicitly quantified | Baseline for comparison |

| Library Size | Derived from 1,000+ structures | 67,000+ compounds [30] | Typically 100-500 compounds [18] | 10,000+ compounds |

| Structural Coverage | 6 defined subpockets | Target-based clustering | Binding mode representation | Not target-organized |

| Chemical Space | Fragment-based (subpocket-annotated) | Lead-like or drug-like | Scaffold-focused with R-groups | Maximally diverse |

| Target Specificity | Kinome-wide with subpocket resolution | Kinase-focused | Kinase family-specific | Pan-target |

| Specialized Applications | Subpocket recombination, scaffold hopping | Tyrosine kinase, dark kinome coverage [30] | Type I/II inhibitors, covalent binding | Phenotypic screening |

Case Study: IP6K2 Inhibitor Discovery

A compelling case study demonstrating the effectiveness of kinase-focused libraries comes from screening for inositol hexakisphosphate kinase (IP6K2) inhibitors. Researchers recognized that "the high degree of structural conservation of the nucleotide binding sites of IP6Ks and protein kinases" enabled them to successfully identify novel IP6K2 inhibitors using a kinase-focused compound library [32].

Experimental Protocol: The screening approach involved:

Assay Development: A time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) assay detecting ADP formation from ATP was developed for high-throughput screening [32].

Library Selection: Two focused compound sets were screened:

- A 5K kinase library from UNC CICBDD (4,727 molecules)

- The GSK Published Kinase Inhibitor Set (PKIS) of 843 molecules [32]

Screening Conditions: Compounds were screened at 10 µM (5K library) and 1 µM (PKIS) concentrations in 384-well format [32].

Hit Validation: Identified hits were validated with dose-response curves (IC50 determination) and an orthogonal HPLC-based assay [32].

Results: The focused screening approach successfully identified novel IP6K2 inhibitors that showed specificity over related kinases. This demonstrates how "a focused screen using molecules known to have features of protein kinase inhibitors would be a potentially successful approach" for targets beyond traditional protein kinases [32].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Kinase-Focused Library Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Databases | KLIFS database, Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of kinase-ligand complex structures for subpocket analysis and fragment assignment [31] |

| Compound Libraries | KinFragLib, GSK PKIS, UNC 5K Library, Life Chemicals Kinase Libraries | Curated compound sets for screening, available as assay-ready plates [31] [32] [30] |

| Computational Tools | BRICS algorithm, CustomKinFragLib filters, Docking software | Fragment generation, unwanted substructure filtering, synthetic accessibility assessment, and virtual screening [31] |

| Screening Assays | TR-FRET ADP detection, ADP-Glo, Cell Painting morphological profiling | Functional activity assessment, high-content phenotypic screening [32] [33] |

| Kinase Activity Assays | Phosphoproteomic analysis, KSEA, PTM-SEA | Kinase activity inference from phosphoproteomics data [34] |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, Gene Ontology, Disease Ontology | Target and pathway annotation for mechanism deconvolution [33] |

Discussion: Advantages and Implementation Considerations

Integration with Chemogenomic Library Research

The structural data-driven approach to kinase library design represents a sophisticated evolution within the broader context of chemogenomics. This methodology aligns with the finding that "focused libraries may be selected from larger, more diverse collections using computational techniques such as in silico docking to the target or ligand similarity calculations" [18]. The subpocket-focused fragmentation strategy particularly enables efficient exploration of kinase chemical space while maintaining relevance to known binding principles.

Research comparing compound sets from different sources has revealed that "compound sets from different sources (commercial; academic; natural) have different protein-binding behaviors" [35]. This underscores the importance of library provenance and design strategy in determining screening outcomes. KinFragLib's foundation in structural data positions it uniquely to access productive regions of chemical space with enhanced probability of identifying quality hits.

Practical Implementation and Customization

For research teams considering implementation of structural data-driven kinase libraries, several practical aspects deserve attention:

Library Size Considerations: While large diverse collections typically contain 10,000+ compounds, focused kinase libraries are generally more compact. BioFocus design guidelines note that kinase-focused libraries typically comprise "around 100-500 compounds, selected to fully explore the design hypothesis efficiently and to adhere to drug-like properties" [18]. This size optimization reflects the balance between comprehensive coverage and practical screening constraints.

Customization Potential: KinFragLib's structure enables targeted customization for specific research needs. The subpocket organization allows researchers to "enumerate recombined fragments in order to generate novel potential inhibitors" [31], facilitating scaffold hopping and lead optimization. The accompanying CustomKinFragLib framework provides adjustable filtering parameters for unwanted substructures, drug-likeness, and synthesizability [31].

Specialized Applications: Beyond general kinase screening, structural data-driven libraries support specialized applications including:

- Covalent kinase inhibitor design [36] [30]

- Allosteric kinase inhibitor development [36]

- Macrocyclic kinase inhibitors [36]

- "Dark kinome" targeting of understudied kinases [30]

Structural data-driven kinase library design, exemplified by the KinFragLib approach, represents a powerful strategy for efficient kinase inhibitor discovery. By leveraging the rich structural information available for kinase-ligand complexes and implementing systematic fragmentation and subpocket assignment, this methodology offers researchers a targeted path to identifying quality hits with reduced screening burden compared to diverse compound sets. The direct integration of structural insights with fragment-based recombination creates a versatile platform for both exploratory kinase research and targeted inhibitor development.

As the field advances, the integration of structural data with emerging computational approaches—including deep learning and generative AI—promises to further enhance the design and application of kinase-focused libraries [37]. These developments will continue to shape the landscape of kinase drug discovery, offering increasingly sophisticated tools for addressing this therapeutically vital protein family.

The drug discovery paradigm has significantly shifted from a reductionist, single-target vision to a more complex systems pharmacology perspective that acknowledges that a single drug often interacts with several targets [33]. This shift is largely driven by the high number of late-stage clinical trial failures attributed to lack of efficacy and safety, particularly for complex diseases like cancer, neurological disorders, and fibrotic diseases, which often stem from multiple molecular abnormalities rather than a single defect [38] [33]. In this context, phenotypic screening has re-emerged as a powerful strategy for identifying first-in-class therapies. This approach identifies active compounds based on measurable biological responses in a disease-relevant system, without requiring prior knowledge of the specific molecular target [39]. A key enabler of modern phenotypic drug discovery is the use of chemogenomic libraries—collections of well-annotated, pharmacologically active compounds designed to modulate a wide range of known drug targets [33] [40]. These libraries provide a strategic advantage by narrowing the vast chemical space and providing starting points for understanding a compound's mechanism of action. This guide objectively compares the performance of chemogenomic libraries against diverse compound sets, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform their screening strategies.

Performance Comparison: Chemogenomic vs. Diverse Compound Libraries

The choice of screening library is a critical factor that influences the hit rate, quality, and subsequent development trajectory of a phenotypic campaign. The table below summarizes a comparative analysis of chemogenomic and diverse compound libraries based on key performance metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Chemogenomic and Diverse Compound Libraries in Phenotypic Screening

| Performance Metric | Chemogenomic Libraries | Diverse Compound Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Library Composition | ~1,600–5,000 selective, target-annotated probes (e.g., kinase inhibitors, GPCR ligands) [6] [33] | ~100,000+ compounds selected for maximal structural diversity [6] |

| Typical Hit Rate | Higher, due to enrichment for biologically active compounds [17] | Lower, as many compounds are pharmacologically inert [17] |

| Target Annotation | Excellent; compounds have known primary targets and extensive pharmacological annotations [6] [40] | Minimal to none; targets are initially unknown [33] |

| Target Deconvolution | Simplified; hypothesis-driven based on known targets of hit compounds [40] [17] | Complex and time-consuming; requires extensive follow-up studies (e.g., proteomics, AI) [39] [17] |

| Risk of Off-Target Effects | Can be assessed early using compounds with diverse scaffolds for the same target [40] | Difficult to predict until late in optimization [41] |

| Primary Utility | Mechanism-of-action studies, target identification, pathway deconvolution [6] [33] | Identifying novel chemical matter and entirely novel biology [41] |

The data indicates that chemogenomic libraries offer a higher probability of success in phenotypic screens aimed at understanding disease mechanisms, as they are pre-enriched for compounds that interact with biologically relevant targets. For instance, one study reported successfully screening a rational library of only 47 candidates, leading to the identification of several active compounds [41]. In contrast, diverse libraries, while larger and capable of uncovering completely novel mechanisms, present greater challenges in downstream target deconvolution and validation [33].

Experimental Protocols for Phenotypic Screening

To ensure reproducible and clinically relevant results, the design of phenotypic screens must incorporate disease-relevant models and robust assay protocols.

Advanced Cellular Models and Screening Cascades

The transition from traditional two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures to more physiologically relevant three-dimensional (3D) models is a critical advancement. For example, in glioblastoma (GBM) research, patient-derived GBM spheroids are used to more accurately capture the tumor microenvironment and its response to therapeutic compounds [41]. A well-designed screening cascade is essential for success, particularly in complex areas like central nervous system (CNS) drug discovery. This involves establishing high-throughput screening formats for key phenotypes such as neuroinflammation or pathological protein aggregation, often using a combination of patient-derived cells and immortalized cell lines to balance clinical relevance and scalability [17].

High-Content Phenotypic Profiling Assays

Image-based high-content screening (HCS) is a cornerstone of modern phenotypic discovery. The "Cell Painting" assay is a widely used morphological profiling method that uses fluorescent dyes to label multiple cellular components (e.g., nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, cytoskeleton). Automated imaging and analysis extract hundreds of morphological features from treated cells, generating a unique "fingerprint" for each compound [33]. This allows for the functional annotation of compounds based on their phenotypic impact.

An alternative live-cell multiplexed assay, termed "HighVia Extend," has been developed to specifically annotate chemogenomic libraries. This protocol classifies cells based on nuclear morphology and other health indicators over time [40].

Table 2: Key Reagents for the HighVia Extend Live-Cell Profiling Assay [40]

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Assay |

|---|---|

| Hoechst 33342 (50 nM) | DNA-staining dye for identifying nuclei and assessing nuclear morphology (pyknosis, fragmentation). |

| BioTracker 488 Green Microtubule Dye | Labels the microtubule network to visualize cytoskeletal integrity and identify tubulin disruption. |

| MitoTracker Red/DeepRed | Stains mitochondria to assess mitochondrial mass and health, indicative of cytotoxic events like apoptosis. |

| Reference Compounds (e.g., Camptothecin, JQ1) | Training set with known mechanisms of action (e.g., apoptosis inducer, BET inhibitor) to validate assay performance. |

| Supervised Machine-Learning Algorithm | Software tool to gate cells into distinct populations (healthy, early/late apoptotic, necrotic, lysed) based on multi-parametric data. |

Protocol Workflow for HighVia Extend [40]:

- Cell Seeding & Compound Treatment: Plate cells (e.g., U2OS, HEK293T, MRC9) in multiwell plates and treat with chemogenomic library compounds.

- Staining: Simultaneously add the optimized, low-concentration cocktail of live-cell dyes (Hoechst 33342, BioTracker 488, MitoTracker) to the culture medium. This minimizes phototoxicity and allows for long-term imaging.

- Live-Cell Imaging: Place the plate in an automated microscope equipped with an environmental chamber (maintaining 37°C and 5% CO₂). Acquire images from multiple sites per well at regular intervals (e.g., every 4-24 hours) over 72 hours.

- Image Analysis & Population Gating: Use image analysis software (e.g., CellProfiler) to identify individual cells and measure features. A pre-trained machine-learning algorithm then classifies each cell into a health status category based on the combined readouts.

- Data Analysis: Generate time-dependent IC50 values and kinetic profiles of cytotoxicity for each compound, providing a comprehensive annotation of its effects on cellular health.

Diagram 1: HighVia Extend assay workflow for phenotypic screening.

From Phenotype to Target: Deconvolution Strategies

Once a hit compound is identified, the next critical challenge is target deconvolution—identifying the molecular target(s) responsible for the observed phenotype.

Integrated Knowledge Graph and Molecular Docking

A novel approach for target deconvolution involves integrating protein-protein interaction knowledge graphs (PPIKG) with molecular docking. This method was successfully used to identify USP7 as the direct target of a p53 pathway activator, UNBS5162 [42]. The knowledge graph analysis narrowed candidate proteins from 1,088 to 35, significantly saving time and cost before molecular docking was performed [42].

Diagram 2: Target deconvolution via knowledge graph and docking.

Proteomic and Genomic Profiling

Direct experimental methods are also widely used for target deconvolution. Thermal proteome profiling (TPP) is a powerful mass spectrometry-based technique that identifies protein targets by detecting which proteins in a cellular lysate show altered thermal stability upon compound binding [41]. This method was used to confirm that a hit compound from a GBM screen engaged multiple targets, aligning with a polypharmacology mechanism [41]. Additionally, RNA sequencing of compound-treated versus untreated cells can reveal the potential mechanism of action by showing which signaling pathways are up- or down-regulated [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and tools that form the foundation of a successful phenotypic screening campaign using chemogenomic libraries.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Screening

| Tool / Reagent | Function & Utility in Screening |

|---|---|

| Curated Chemogenomic Library | Pre-annotated collection of compounds (e.g., kinase inhibitors, GPCR ligands) for screening; enables easier target hypothesis generation [6] [33]. |

| Patient-Derived Cells & 3D Spheroid Cultures | Disease-relevant cellular models that better recapitulate the in vivo microenvironment for improved clinical translation [41] [17]. |

| Live-Cell Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., Hoechst, MitoTracker) | Enable real-time, multiplexed monitoring of cell health parameters (viability, cytotoxicity, mitochondrial health) in high-content assays [40]. |

| High-Content Imaging System | Automated microscope for capturing high-resolution cellular images from multiwell plates, essential for complex phenotypic readouts [33] [40]. |