Chemogenomic Compound Libraries: Principles, Applications, and Future Directions in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemogenomic compound libraries, which are collections of well-annotated small molecules designed to systematically probe the functions of a wide range of protein targets.

Chemogenomic Compound Libraries: Principles, Applications, and Future Directions in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemogenomic compound libraries, which are collections of well-annotated small molecules designed to systematically probe the functions of a wide range of protein targets. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of chemogenomics, the design and assembly of these libraries, and their critical application in both target-based and phenotypic screening for hit identification and target deconvolution. The content further addresses common challenges and limitations in screening, outlines strategies for data analysis and experimental optimization, and explores advanced computational and experimental methods for validating library outputs. By synthesizing current methodologies and future trends, this article serves as an essential guide for leveraging chemogenomic libraries to accelerate therapeutic discovery.

The Foundations of Chemogenomics: From Chemical Probes to Systematic Library Design

Defining Chemogenomic Libraries and Their Role in Modern Drug Discovery

Chemogenomics represents a systematic approach in drug discovery that utilizes targeted libraries of small molecules to screen entire families of biologically relevant proteins, with the dual goal of identifying novel therapeutic agents and elucidating the functions of previously uncharacterized targets [1]. This methodology stands in contrast to traditional single-target approaches, instead embracing a holistic perspective that explores the intersection of all possible drug-like molecules across the vast landscape of potential therapeutic targets [1]. The completion of the Human Genome Project provided the essential foundation for chemogenomics by revealing an abundance of potential targets for therapeutic intervention, creating a need for systematic approaches to characterize their functions and therapeutic potential [1] [2]. Within this paradigm, chemogenomic libraries serve as critical research tools—collections of well-annotated, target-focused compounds that enable researchers to efficiently probe biological systems and accelerate the conversion of phenotypic observations into target-based drug discovery approaches [3].

The strategic value of chemogenomic libraries lies in their ability to bridge the gap between phenotypic screening and target-based approaches. While phenotypic screening has experienced a resurgence in drug discovery due to its ability to identify functionally active compounds without requiring prior knowledge of their molecular targets, a significant challenge remains in functionally annotating the identified hits and understanding their mechanisms of action [4] [5]. Chemogenomic libraries, typically composed of selective small-molecule pharmacological agents with known target annotations, substantially diminish this challenge [3] [5]. When a compound from such a library produces a phenotypic effect, it suggests that its annotated target or targets may be involved in mediating the observed phenotype, thereby facilitating target deconvolution and validation [3].

Core Principles and Definitions

Fundamental Concepts

At its core, chemogenomics describes a method that utilizes well-annotated and characterized tool compounds for the functional annotation of proteins in complex cellular systems and the discovery and validation of targets [6]. Unlike chemical probes, which must meet stringent selectivity criteria, the small molecule modulators used in chemogenomic studies may not be exclusively selective for a single target, enabling coverage of a larger target space while maintaining reasonable quality standards [6]. This pragmatic balance between selectivity and coverage is a defining characteristic of chemogenomic approaches, making them particularly valuable for probing the functions of diverse protein families.

The experimental framework of chemogenomics encompasses two complementary approaches: forward chemogenomics and reverse chemogenomics [1]. In forward chemogenomics (also known as classical chemogenomics), researchers begin with a particular phenotype of interest and identify small molecules that induce or modify this phenotype without prior knowledge of the specific molecular targets involved. Once modulators are identified, they are used as tools to identify the proteins responsible for the observed phenotype [1]. Conversely, reverse chemogenomics starts with small compounds that perturb the function of a specific enzyme or protein in vitro, followed by analysis of the phenotypes induced by these molecules in cellular systems or whole organisms [1]. This approach confirms the biological role of the targeted protein and validates its therapeutic relevance.

Key Differentiators from Related Approaches

Chemogenomic libraries occupy a distinct niche among chemical collections used in drug discovery. They differ from traditional combinatorial libraries in their targeted nature and careful annotation, and from chemical probe collections in their less stringent selectivity requirements [6] [2]. While high-quality chemical probes have been developed for only a small fraction of potential targets, the more pragmatic criteria for compounds in chemogenomic libraries enables coverage of a much larger portion of the druggable genome [6]. The EUbOPEN consortium, for instance, aims to cover approximately 30% of the currently estimated 3,000 druggable targets through its chemogenomic library efforts [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Chemical Collection Types in Drug Discovery

| Collection Type | Selectivity Requirements | Coverage | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | Stringent criteria for high selectivity | Small fraction of targets | Specific target validation and pathway elucidation |

| Chemogenomic Libraries | Moderate selectivity, pragmatic criteria | Large target space (30% of druggable genome) | Phenotypic screening, target identification, polypharmacology studies |

| Diverse Compound Libraries | No predefined selectivity | Broad chemical space | Initial hit identification, serendipitous discovery |

| Focused Libraries | Variable, often target-family specific | Specific protein families | Targeted screening for particular target classes |

Design and Assembly of Chemogenomic Libraries

Strategic Considerations and Design Goals

The design of chemogenomic libraries requires careful consideration of the intended research goals, as different objectives necessitate different library configurations and compound selection strategies [7]. A library intended for specific kinase discovery projects would employ different design criteria than one intended for general phenotypic screening across multiple target families [7]. Current design protocols address several specialized scenarios, including: data mining of structure-activity relationship (SAR) databases and kinase-focused vendor catalogues; virtual screening and predictive modeling; structure-based design of combinatorial kinase inhibitors; and the design of specialized inhibitor classes such as covalent kinase inhibitors, macrocyclic kinase inhibitors, and allosteric kinase inhibitors and activators [7].

The assembly of chemogenomic libraries typically follows a target-family organization, with subsets of compounds covering major target families such as protein kinases, membrane proteins, and epigenetic modulators [6]. This organizational principle leverages the structural and functional similarities within protein families to maximize the efficiency of target coverage while facilitating the interpretation of screening results. For example, knowing that a compound library contains multiple inhibitors targeting different members of a protein family allows researchers to draw more meaningful conclusions when several related compounds produce similar phenotypic effects.

Practical Implementation and Characterization

The practical implementation of chemogenomic libraries requires rigorous quality control and comprehensive compound annotation. As highlighted by researchers at the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC), this involves thorough characterization of chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds through cellular target engagement assays, cellular selectivity assessments, and screening for off-target effects using high-content imaging techniques [2]. Essential quality parameters include structural identity, purity, solubility, and comprehensive profiling of effects on basic cellular functions such as cell viability, mitochondrial health, membrane integrity, cell cycle progression, and potential interference with cytoskeletal functions [5].

Advanced technologies have become indispensable for proper library annotation. Automated image analysis systems and machine learning algorithms enable high-content techniques to characterize compound effects comprehensively [5]. For instance, Müller-Knapp's team developed a modular live-cell multiplexed assay that classifies cells based on nuclear morphology—an excellent indicator of cellular responses such as early apoptosis and necrosis [5]. This approach, combined with detection of changes in cytoskeletal morphology, cell cycle, and mitochondrial health, provides time-dependent characterization of compound effects on cellular health in a single experiment [5].

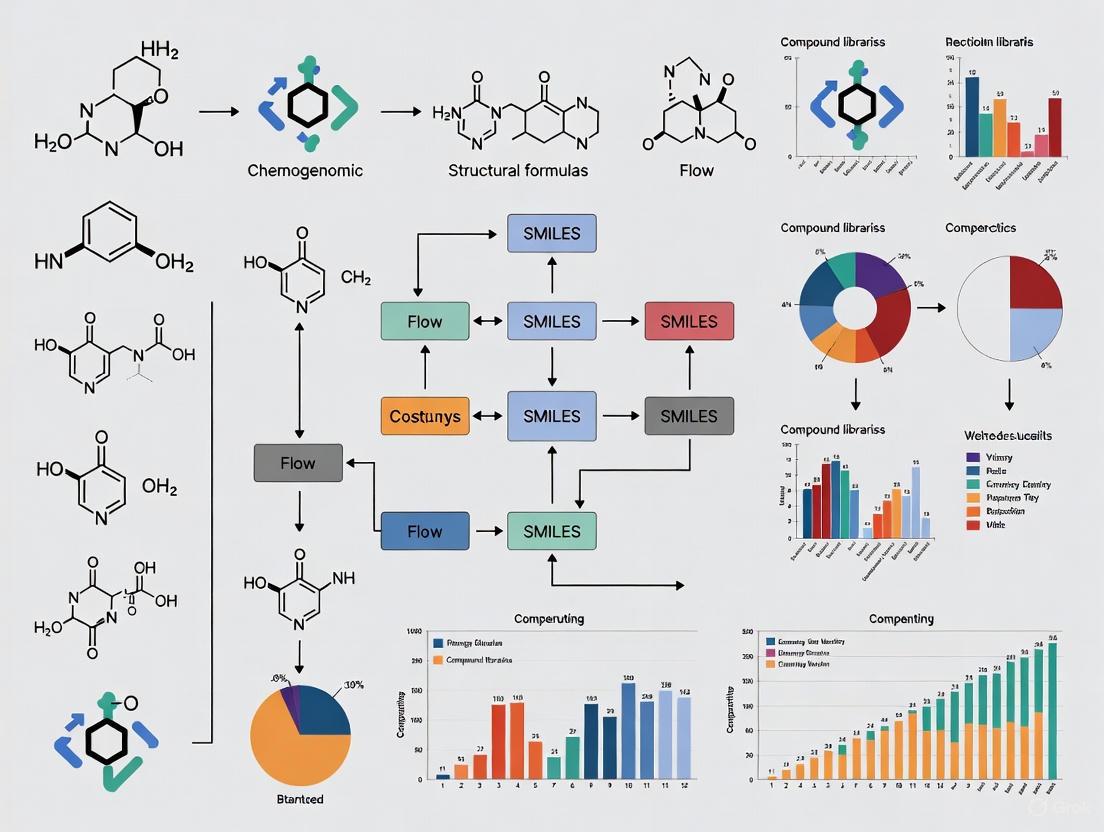

Diagram 1: Chemogenomic Library Development Workflow. This workflow illustrates the multi-stage process of designing, assembling, and validating chemogenomic libraries, from initial purpose definition to final quality-controlled library ready for screening applications.

Key Applications in Drug Discovery

Phenotypic Screening and Target Deconvolution

One of the most significant applications of chemogenomic libraries is in phenotypic screening, where they facilitate the identification of novel therapeutic targets and the deconvolution of complex biological mechanisms [3]. In phenotypic screening approaches, cells or model organisms are treated with library compounds, and observable phenotypes are measured without presupposing specific molecular targets. When a hit is identified from a chemogenomic library, the annotated targets of that pharmacological agent provide immediate hypotheses about the molecular mechanisms responsible for the observed phenotype [3]. This strategy combines the biological relevance of phenotypic screening with the mechanistic insights typically associated with target-based approaches, effectively bridging these two drug discovery paradigms.

The power of this approach is enhanced when multiple compounds with overlapping target profiles are included in the library. Using several chemogenomic compounds directed toward the same target but with diverse additional activities enables researchers to deconvolute phenotypic readouts and identify the specific target causing the cellular effect [5]. Furthermore, compounds from diverse chemical scaffolds may facilitate the identification of off-target effects across different protein families, providing a more comprehensive understanding of compound activities and potential therapeutic applications [5].

Mechanism of Action Elucidation and Drug Repurposing

Chemogenomic approaches have proven valuable for elucidating mechanisms of action (MOA) for both newly discovered compounds and traditional medicines [1]. For example, researchers have applied chemogenomics to understand the MOA of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and Ayurvedic formulations by linking their known therapeutic effects (phenotypes) to potential molecular targets [1]. In one case study involving TCM toning and replenishing medicines, researchers identified sodium-glucose transport proteins and PTP1B (an insulin signaling regulator) as targets linked to the hypoglycemic phenotype, providing mechanistic insights for these traditional remedies [1].

Additionally, chemogenomic profiling enables drug repositioning by revealing novel therapeutic applications for existing compounds based on their target affinities and phenotypic effects [3]. By screening chemogenomic libraries against disease models, researchers can identify compounds with unexpected efficacy, then use their target annotations to generate mechanistic hypotheses for further validation. This approach leverages existing knowledge about compound-target interactions to accelerate the discovery of new therapeutic indications.

Table 2: Primary Applications of Chemogenomic Libraries in Drug Discovery

| Application Area | Specific Use Cases | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Forward chemogenomics, functional annotation of orphan targets | Links phenotypic effects to molecular targets, facilitates understanding of protein function |

| Mechanism of Action Studies | Elucidation of traditional medicine mechanisms, understanding compound efficacy | Provides hypothesis for molecular mechanisms underlying observed phenotypes |

| Drug Repurposing | Identification of new therapeutic indications for existing compounds | Accelerates discovery of new uses, leverages existing safety profiles |

| Predictive Toxicology | Profiling compounds for phospholipidosis induction, cytotoxicity assessment | Early identification of safety concerns, reduces late-stage attrition |

| Polypharmacology | Understanding multi-target activities, designing selective promiscuity | Enables rational design of multi-target therapies for complex diseases |

| Pathway Elucidation | Identifying genes in biological pathways, mapping cellular networks | Reveals functional connections between targets and biological processes |

Practical Implementation: The EUbOPEN Initiative

The EUbOPEN project exemplifies the large-scale implementation of chemogenomics in modern drug discovery. This consortium aims to generate an open-access chemogenomic library covering more than 1,000 proteins through well-annotated chemogenomic compounds and chemical probes [6] [5]. The project represents a crucial step toward the goals of Target 2035, a global initiative initiated by the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) to develop pharmacological modulators for the entire human proteome [2] [5]. The EUbOPEN library is organized into subsets covering major target families, with each compound undergoing rigorous characterization and validation to ensure research quality and reproducibility [6].

The collaborative nature of EUbOPEN highlights the importance of data sharing and open science in advancing chemogenomics. By pooling resources and expertise from multiple academic and industry partners, the project accelerates the development and characterization of chemogenomic tools while making them freely accessible to the research community [2]. This open-access model maximizes the impact of chemogenomic libraries by enabling their widespread use across diverse research applications and therapeutic areas.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Cellular Characterization and Viability Assessment

Proper annotation of chemogenomic libraries requires comprehensive assessment of compound effects on cellular health and function. Researchers have developed optimized live-cell multiplexed assays that classify cells based on nuclear morphology, which serves as a sensitive indicator of cellular responses such as early apoptosis and necrosis [5]. This basic readout, when combined with detection of other general cell-damaging activities—including changes in cytoskeletal morphology, cell cycle progression, and mitochondrial health—provides time-dependent characterization of compound effects in a single experiment [5].

A representative protocol for cellular characterization involves several key steps. First, cells are plated in multiwell plates and treated with test compounds at appropriate concentrations. Live-cell imaging is then performed using fluorescent dyes at optimized concentrations that provide robust detection without interfering with cellular functions [5]. Key dye concentrations typically include: 50 nM Hoechst33342 for nuclear staining, MitotrackerRed for mitochondrial visualization, and BioTracker 488 Green Microtubule Cytoskeleton Dye for tubulin staining [5]. Imaging is conducted over extended time periods (e.g., 24-72 hours) to capture kinetic profiles of compound effects. Automated image analysis identifies individual cells and measures morphological features, with machine learning algorithms classifying cells into different populations (e.g., healthy, early/late apoptotic, necrotic, lysed) based on these features [5].

Diagram 2: Cellular Characterization Workflow for Chemogenomic Library Annotation. This process illustrates the key steps in comprehensively profiling compound effects on cellular health, from initial treatment and staining through automated analysis and final database annotation.

Target Engagement and Selectivity Profiling

Beyond general cellular effects, comprehensive annotation of chemogenomic libraries requires assessment of target engagement and selectivity. Protocols for establishing cellular target engagement include bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)-based technologies, which enable higher-throughput evaluation of compound binding to targets in living cells [2]. These approaches provide direct evidence that compounds reach and engage their intended targets in physiologically relevant environments, a critical consideration for interpreting phenotypic screening results.

Selectivity profiling typically involves panel-based screening against related targets within the same protein family. For example, kinase-focused chemogenomic libraries would be profiled against panels of representative kinases to determine selectivity patterns and identify potential off-target activities [7] [2]. This information is crucial for interpreting phenotypic screening results, as it enables researchers to distinguish between effects mediated by the primary target and those resulting from secondary off-target interactions. The resulting selectivity matrices become valuable components of the library annotation, guiding appropriate use and interpretation of screening results.

Research Reagents and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemogenomic Library Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Live-Cell Fluorescent Dyes | Hoechst33342 (50 nM), MitotrackerRed, BioTracker 488 Green Microtubule Cytoskeleton Dye | Multiplexed staining of cellular compartments for high-content imaging and viability assessment |

| Cell Lines | HEK293T (human embryonic kidney), U2OS (osteosarcoma), MRC9 (non-transformed human fibroblasts) | Representative cellular models for assessing compound effects across different genetic backgrounds |

| Target Engagement Assays | BRET (Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer) systems | Measurement of compound binding to targets in living cells under physiological conditions |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Automated microscope systems with environmental control | Live-cell imaging over extended time periods for kinetic analysis of compound effects |

| Reference Compounds | Camptothecin, JQ1, Torin, Digitonin, Staurosporine | Training set for assay validation and quality control across different mechanisms of action |

| Data Analysis Tools | Machine learning algorithms for cell classification, CellProfiler for image analysis | Automated extraction and interpretation of morphological features from imaging data |

Emerging Trends and Technologies

The field of chemogenomics continues to evolve, driven by advances in screening technologies, data analysis methods, and collaborative research models. Several emerging trends are likely to shape future developments in chemogenomic library design and application. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are playing increasingly important roles in analyzing complex screening data, predicting drug-target interactions, and guiding library optimization [2]. These computational approaches enable more efficient extraction of meaningful patterns from high-dimensional data, enhancing the value of chemogenomic screening results.

There is also growing interest in expanding chemogenomic approaches to cover challenging target classes that have traditionally been considered difficult to drug. Initiatives like EUbOPEN are focusing on new target areas such as the ubiquitin system and solute carriers, which could significantly expand the druggable proteome beyond the current estimate of approximately 3,000 targets [6]. As these efforts progress, chemogenomic libraries will likely incorporate novel compound modalities—such as proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs), molecular glues, and covalent inhibitors—that enable modulation of previously inaccessible targets [2].

Chemogenomic libraries represent a powerful platform for systematic drug discovery, integrating principles of chemical biology, genomics, and systems pharmacology to accelerate the identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets. By providing well-annotated collections of target-focused compounds, these libraries bridge the gap between phenotypic and target-based screening approaches, enabling more efficient deconvolution of complex biological mechanisms. The continued expansion and refinement of chemogenomic resources through initiatives like EUbOPEN and Target 2035 will further enhance their utility as essential tools for modern drug discovery research.

As the field advances, increased emphasis on open science and collaborative research models will be crucial for maximizing the impact of chemogenomic approaches. By sharing high-quality chemical tools and associated data openly with the research community, these initiatives promote rigorous, reproducible science while accelerating the translation of basic research findings into novel therapeutic strategies for addressing unmet medical needs.

Within modern drug discovery and basic research, the precise use of chemical tools is paramount. This technical guide delineates the critical distinctions between chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds, two foundational yet fundamentally different classes of research reagents. While both are small molecules used to modulate protein function, they are defined by divergent quality criteria and are applied to answer distinct biological questions. Chemical probes are characterized by their high potency and selectivity, making them suitable for attributing a specific cellular phenotype to a single target. In contrast, chemogenomic compounds are utilized as collective sets to probe entire gene families or large segments of the proteome, accepting a lower threshold for selectivity to achieve broader target coverage. This paper elaborates on the defining principles, experimental applications, and quality control measures for each class, providing a framework for their rigorous application within chemogenomic compound library research.

The completion of the human genome project revealed a catalog of roughly 20,000 protein-coding genes, yet the function of the vast majority of these proteins remains poorly understood [8]. Chemogenomics, defined as the systematic screening of targeted chemical libraries of small molecules against individual drug target families, aims to bridge this knowledge gap by using small molecules as probes to characterize proteome function [1]. This approach integrates target and drug discovery by using active compounds as ligands to induce and study phenotypes, thereby associating a protein with a molecular event [1].

Within this paradigm, two primary classes of small-molecule reagents have emerged: chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds. The precise definition and application of these tools are critical, as their suboptimal use has been identified as a significant contributor to the robustness crisis in biomedical literature [9]. A systematic review of hundreds of publications revealed that only 4% of studies used chemical probes in line with best-practice recommendations [9]. This guide provides a detailed examination of these two reagent classes to promote their correct and impactful application in research.

Defining the Tools: Chemical Probes vs. Chemogenomic Compounds

Chemical Probes: Stringent Criteria for Target-Specific Research

A chemical probe is a cell-permeable, small-molecule modulator of protein function that meets stringent quality criteria for potency and selectivity [10] [8]. According to consensus criteria established by the chemical biology community, a high-quality chemical probe must exhibit:

- Potency: In vitro potency (IC₅₀ or Kd) of < 100 nM [8] [9].

- Selectivity: A >30-fold selectivity for the intended target over other related targets within the same protein family, supported by extensive profiling against off-targets outside the primary family [8] [9].

- Cellular Activity: Demonstrated on-target engagement and modulation in cellular assays at concentrations ideally below 1 μM [9].

The primary application of chemical probes is to investigate the biological function of a specific protein in biochemical, cellular, and in vivo settings with high confidence that the observed phenotypes are due to modulation of the intended target [8]. The Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) and collaborators have developed almost two hundred such probes for previously under-studied proteins [11].

Chemogenomic Compounds: A Broader Net for Proteome Exploration

In contrast, a chemogenomic compound is a pharmacological modulator that interacts with gene products to alter their biological function but often does not meet the stringent potency and selectivity criteria required of a chemical probe [10]. The related term "chemogenomic library" refers to a collection of such well-defined, but not necessarily highly selective, pharmacological agents [12].

The fundamental distinction lies in the trade-off between selectivity and coverage. While high-quality chemical probes have been developed for only a small fraction of potential targets, the less stringent criteria for chemogenomic compounds enable the creation of libraries that cover a much larger target space [6]. The goal of initiatives like EUbOPEN is to assemble chemogenomic libraries covering approximately 30% of the currently estimated 3,000 druggable targets in the human proteome [6].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Chemical Probes and Chemogenomic Compounds

| Characteristic | Chemical Probes | Chemogenomic Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Specific target validation and functional analysis | Broad phenotypic screening and target discovery |

| Potency | < 100 nM (often < 10 nM) [8] | Variable; often lower potency is accepted [10] |

| Selectivity | >30-fold within target family; extensive off-target profiling [8] | May be selective, but lower selectivity is tolerated for coverage [10] |

| Target Coverage | Deep coverage for a single, specific target | Broad coverage across a target family or multiple families |

| Ideal Application | Mechanistic studies linking a specific protein to a phenotype | Initial screening to implicate a pathway or target family in a phenotype |

Experimental Applications and Workflows

The distinct roles of chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds are best illustrated through their characteristic experimental workflows.

The Forward and Reverse Chemogenomics Paradigm

Chemogenomic screening operates through two complementary approaches: forward and reverse chemogenomics [1]. The diagram below illustrates the logical flow of these two strategies.

Forward Chemogenomics (Phenotype-first) begins with a desired cellular or organismal phenotype, such as the arrest of tumor growth. Researchers screen a chemogenomic compound library to identify molecules that induce this phenotype. The molecular target(s) of the active compound(s) are then identified through target deconvolution methods, which can include affinity-based proteomics, activity-based protein profiling (ABPP), or cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) [13] [1]. This approach is particularly powerful for discovering novel biology without preconceived notions about which targets are involved.

Reverse Chemogenomics (Target-first) starts with a specific, well-defined protein target, such as a kinase or bromodomain. A chemogenomic library is screened against this target in an in vitro assay to identify binding partners or modulators. Once a hit is identified, the compound is then applied in cellular or whole-organism models to analyze the resulting phenotype [1]. This strategy is enhanced by parallel screening across multiple members of a target family.

The Target Validation Workflow with Chemical Probes

Once a potential target has been identified—whether through genetic means or from a chemogenomic screen—the role of chemical probes becomes critical. The following workflow details the best-practice use of chemical probes for rigorous target validation, a process that is often poorly implemented [9].

The principle of 'The Rule of Two' has been proposed to formalize this process. It mandates that every study should employ at least two chemical probes—either a pair of orthogonal target-engaging probes with different chemical structures, and/or a pair of an active chemical probe and its matched target-inactive control—at their recommended concentrations [9]. The use of a target-inactive control is crucial, as even minor structural changes can lead to non-overlapping off-target profiles [8].

Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Successful execution of chemogenomic and chemical probe studies relies on a toolkit of well-characterized reagents and robust experimental methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Chemogenomics and Chemical Probe Research

| Reagent / Resource | Function and Description | Example Providers / Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Kinase Chemogenomic Set (KCGS) | A focused library of inhibitors targeting the catalytic function of a large fraction of the human protein kinome [10]. | SGC UNC [10] |

| EUbOPEN Chemogenomic Library | An open-source collection of compounds aimed at covering major target families (kinases, epigenetic modulators, etc.) for the research community [6]. | EUbOPEN Consortium [6] |

| High-Quality Chemical Probes | Potent, selective, and cell-active small molecules for specific target validation. Must meet stringent criteria for potency (<100 nM) and selectivity (>30-fold) [8]. | SGC, Donated Chemical Probes Portal [10] [11] |

| Matched Inactive Control Compounds | Structurally similar analogues of a chemical probe that lack activity against the primary target. Used to control for off-target effects [8] [9]. | Often developed alongside probes by SGC and others [9] |

| The Chemical Probes Portal | A curated, expert-reviewed online resource that scores and recommends high-quality chemical probes for specific protein targets [8] [9]. | www.chemicalprobes.org [9] |

| Probe Miner | A data-driven platform that statistically ranks small molecules based on bioactivity data mined from literature, complementing expert-curated portals [8]. | https://probeminer.icr.ac.uk [8] |

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

A. Affinity-Based Protein Profiling for Target Deconvolution

This direct chemoproteomic method is used to identify the cellular targets of a bioactive compound, typically from a chemogenomic screen [13].

- Procedure:

- Probe Design: The bioactive small molecule is modified with a linker (e.g., an alkyl chain) and a functional tag (e.g., biotin for enrichment, or a fluorescent dye for visualization).

- Cell Lysis and Incubation: The modified compound is incubated with a whole-cell extract or a cellular fraction under physiological conditions to allow binding to its protein targets.

- Target Capture: For biotinylated probes, streptavidin-coated beads are used to capture the probe-protein complexes from the lysate. Unbound proteins are removed through extensive washing.

- On-bead Digestion: Captured proteins are digested on the beads using a protease like trypsin.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: The resulting peptides are analyzed by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for protein identification.

- Validation: Identified candidate targets must be validated using orthogonal methods, such as cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) or genetic knockdown/knockout [13].

B. Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA)

A label-free method to detect direct ligand-target engagement in a cellular context, useful for validating targets identified from screens or confirming on-target engagement of a chemical probe [13].

- Procedure:

- Compound Treatment: Live cells or cell lysates are treated with the chemical probe of interest or a vehicle control (e.g., DMSO).

- Heat Denaturation: The samples are divided into aliquots and heated to a range of different temperatures (e.g., from 40°C to 65°C).

- Protein Aggregation: The heat causes the denaturation and aggregation of proteins. Ligand-bound proteins are typically stabilized and remain in solution at higher temperatures.

- Soluble Protein Separation: The aggregated proteins are separated from the soluble proteins by high-speed centrifugation or filtration.

- Analysis: The soluble, non-aggregated protein fraction is analyzed. The amount of the target protein remaining soluble at the various temperatures is quantified, typically by immunoblotting or quantitative mass spectrometry. A rightward shift in the protein's melting curve (Tm) in the compound-treated sample indicates stabilization due to direct binding [13].

The distinction between chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds is foundational to rigorous research in chemical biology and drug discovery. Chemical probes are the precision instruments, defined by stringent criteria of potency and selectivity, and are best used for the definitive validation of a specific target's function in a phenotypic context. Chemogenomic compounds, when assembled into libraries, are the broad screening tools that enable the exploration of vast tracts of the proteome, accepting a trade-off in individual compound selectivity to achieve unparalleled target family coverage.

The synergy between these tools is clear: chemogenomic libraries can reveal novel targets and biology through phenotypic screening, while high-quality chemical probes are then required to deconvolute and validate these findings with high confidence. As the field moves forward, adherence to community-established best practices—such as 'The Rule of Two' and the use of curated resources like the Chemical Probes Portal—will be essential to ensure that the data generated with these powerful chemical tools is robust, reproducible, and impactful for our understanding of biology and the development of new medicines.

The systematic exploration of the human proteome represents one of the most significant challenges and opportunities in modern drug discovery. While the human genome comprises approximately 20,000 protein-coding genes, only a fraction of these proteins have been successfully targeted by pharmacological agents [14]. The concept of "druggability" describes the ability of a protein to bind with high affinity to a drug-like molecule, resulting in a functional change that provides therapeutic benefit [15]. Historically, drug discovery has focused on a limited set of protein families, with current FDA-approved drugs targeting only approximately 854 human proteins [14]. This conservative approach has left vast areas of the proteome unexplored, often referred to as the "dark" proteome, despite genetic evidence implicating many understudied proteins in human disease [16].

In response to this challenge, the global scientific community has launched Target 2035, an ambitious international open science initiative that aims to generate chemical or biological modulators for nearly all human proteins by the year 2035 [17] [18]. This initiative, driven by the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) and involving numerous academic and industry partners, seeks to create the tools necessary to translate advances in genomics into a deeper understanding of human biology and disease mechanisms. Target 2035 recognizes that pharmacological modulators—including high-quality chemical probes, chemogenomic compounds, and functional antibodies—represent one of the most powerful approaches to interrogating protein function and validating therapeutic targets [16]. The initiative operates on the principle that making these research tools freely available to the scientific community will catalyze the exploration of understudied proteins and unlock new opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Defining the Druggable Proteome: Current Landscape and Challenges

The Concept of Druggability

Druggability encompasses more than simply the ability of a protein to bind a small molecule; it requires that this binding event produces a functional change with potential therapeutic benefit [15]. Proteins amenable to drug binding typically share specific structural and physicochemical properties, including the presence of well-defined binding pockets with appropriate hydrophobicity and surface characteristics [19]. The "druggable genome" was originally defined as proteins with sequences similar to known drug targets and capable of binding small molecules compliant with Lipinski's Rule of Five [15]. However, this definition has expanded with advances in chemical modalities, including the development of therapeutic antibodies, molecular glues, PROTACs (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras), and other proximity-inducing molecules that have significantly expanded the boundaries of what constitutes a druggable target [17] [18].

Computational assessments of druggability have employed various approaches, including structure-based methods that analyze binding pocket characteristics, precedence-based methods that leverage knowledge of related protein families, and feature-based methods that utilize sequence-derived properties [19] [20] [15]. These methods typically employ machine learning algorithms trained on known drug targets. For instance, the eFindSite tool employs supervised machine learning to predict druggability based on pocket descriptors and binding residue characteristics, achieving an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.88 in benchmarking studies [19]. Similarly, PINNED (Predictive Interpretable Neural Network for Druggability) utilizes a neural network architecture that generates druggability sub-scores based on sequence and structure, localization, biological functions, and network information, achieving an impressive AUC of 0.95 [20].

Currently Drugged Proteins and Protein Families

Analysis of FDA-approved drugs reveals distinct patterns in target distribution across protein families. The following table summarizes the classification of known drug targets according to the Human Protein Atlas:

Table 1: Classification of targets for FDA-approved drugs [14]

| Protein Class | Number of Genes |

|---|---|

| Enzymes | 323 |

| Transporters | 294 |

| Voltage-gated Ion Channels | 61 |

| G-protein Coupled Receptors | 110 |

| Nuclear Receptors | 21 |

| CD Markers | 90 |

The predominance of enzymes, transporters, and GPCRs as drug targets reflects historical trends in drug discovery rather than an inherent limitation of the proteome. These protein families typically possess well-defined binding pockets that facilitate small molecule interactions. Additionally, the majority of drug targets (68%) are membrane-bound or secreted proteins, reflecting the accessibility of these targets to drug molecules and the importance of signal transduction pathways in disease processes [14].

Challenges in Expanding the Druggable Proteome

Several significant challenges hinder the expansion of the druggable proteome. Protein-protein interactions have proven particularly difficult to target, as these often occur across large, relatively flat surfaces with low affinity for small molecules [15]. Additionally, many disease-relevant proteins lack defined binding pockets or belong to protein families with no established chemical starting points. The high cost and extended timelines of drug development further complicate target exploration, with an estimated 60% of drug discovery failures attributed to invalid or inappropriate target identification [19]. This highlights the critical importance of robust target validation early in the discovery process.

The EUbOPEN Consortium: Structure, Goals, and Methodologies

The EUbOPEN (Enabling and Unlocking Biology in the OPEN) consortium represents a major public-private partnership and a cornerstone of the Target 2035 initiative [17] [18] [21]. Launched in May 2020 with a total budget of €65.8 million, EUbOPEN brings together 22 partner organizations from academia, industry, and non-profit research institutions, jointly led by Goethe University Frankfurt and Boehringer Ingelheim [21]. The consortium's primary goal is to create, characterize, and distribute the largest openly available collection of high-quality chemical modulators for human proteins, with initial focus on covering approximately one-third of the druggable proteome [17] [6].

EUbOPEN's activities are organized around four interconnected pillars:

- Chemogenomic library collections - Assembling comprehensively characterized compound sets targeting diverse protein families

- Chemical probe discovery and technology development - Creating high-quality chemical probes for challenging target classes and improving hit-to-lead optimization processes

- Profiling of bioactive compounds in patient-derived disease assays - Evaluating compound activity in physiologically relevant systems, with focus on immunology, oncology, and neuroscience

- Collection, storage, and dissemination of project-wide data and reagents - Ensuring open access to all research outputs without restriction [17] [18]

This integrated approach ensures that the chemical tools generated by the consortium are rigorously validated in disease-relevant contexts and accessible to the broader research community.

Chemical Probes: The Gold Standard for Target Validation

Chemical probes represent the highest standard for pharmacological tools in target validation studies. EUbOPEN has established strict criteria for these molecules, requiring potency in in vitro assays of less than 100 nM, selectivity of at least 30-fold over related proteins, evidence of target engagement in cells at less than 1 μM (or 10 μM for challenging targets like protein-protein interactions), and a reasonable cellular toxicity window [17] [18]. These stringent criteria ensure that chemical probes are fit-for-purpose in delineating the biological functions of their protein targets.

The consortium aims to deliver 50 new collaboratively developed chemical probes, with particular emphasis on challenging target classes such as E3 ubiquitin ligases and solute carriers (SLCs), and to collect an additional 50 high-quality chemical probes from the community through its Donated Chemical Probes (DCP) project [17] [18]. All probes are peer-reviewed by an external committee and distributed with structurally similar inactive control compounds to facilitate interpretation of experimental results. To date, EUbOPEN has distributed more than 6,000 samples of chemical probes and controls to researchers worldwide without restrictions [17].

Table 2: EUbOPEN Chemical Probe Qualification Criteria [17] [18]

| Parameter | Requirement |

|---|---|

| In vitro potency | < 100 nM |

| Selectivity | ≥ 30-fold over related proteins |

| Cellular target engagement | < 1 μM (or < 10 μM for PPIs) |

| Toxicity window | Sufficient to separate target effect from cytotoxicity |

| Controls | Must include structurally similar inactive compound |

Chemogenomic Libraries: Expanding Coverage Through Annotated Selectivity

While chemical probes represent the ideal for target validation, their development is resource-intensive and challenging for many protein targets. Chemogenomic (CG) compounds provide a complementary approach—these are potent inhibitors or activators with narrow but not exclusive target selectivity [17] [6]. When assembled into collections with overlapping selectivity profiles, these compounds enable target deconvolution based on selectivity patterns and provide coverage for a much larger fraction of the proteome.

EUbOPEN is assembling a chemogenomic library covering approximately one-third of the druggable proteome, organized into subsets targeting major protein families including kinases, membrane proteins, and epigenetic modulators [17] [6]. The consortium has established family-specific criteria for compound inclusion, considering factors such as the availability of well-characterized compounds, screening possibilities, ligandability of different targets, and the ability to include multiple chemotypes per target [17]. This approach leverages the hundreds of thousands of bioactive compounds generated by previous medicinal chemistry efforts, with public repositories containing 566,735 compounds with target-associated bioactivity ≤10 μM covering 2,899 human target proteins as candidate compounds [17].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between Target 2035, EUbOPEN, and their core components:

Technological Innovations and Experimental Approaches

Advanced Compound Screening and Profiling Technologies

EUbOPEN employs state-of-the-art technologies for compound screening and profiling to accelerate the identification and characterization of chemical tools. The consortium has established comprehensive selectivity panels for different target families to annotate compound activity profiles thoroughly [17]. This includes the development of new technologies to significantly shorten hit identification and hit-to-lead optimization processes, providing the foundation for future efforts toward Target 2035 goals [18].

A key innovation is the application of patient-derived disease assays for compound profiling, particularly in the areas of inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, and neurodegeneration [17] [18]. These physiologically relevant systems provide more predictive data about compound activity in human disease contexts compared to traditional cell line models. All compounds in the EUbOPEN collections are comprehensively characterized for potency, selectivity, and cellular activity using a suite of biochemical and cell-based assays [18].

Targeting Challenging Protein Classes

EUbOPEN has placed special emphasis on protein classes that have historically been difficult to target but offer significant therapeutic potential. E3 ubiquitin ligases represent a particular focus, given their roles as attractive targets in their own right and as the enzymes co-opted by degrader molecules such as PROTACs and molecular glues [17] [18]. The consortium has developed covalent inhibitors targeting challenging domains, such as the SH2 domain of the Cul5-RING ubiquitin E3 ligase substrate receptor SOCS2, employing structure-based design and prodrug strategies to address cell permeability challenges [17].

Similarly, solute carriers (SLCs) represent a large family of membrane transport proteins with important roles in physiology and disease that have been underexplored as drug targets. EUbOPEN aims to develop chemical tools for these challenging target classes to facilitate their biological and therapeutic exploration [17] [18].

Computational Approaches for Druggability Assessment

Computational methods play an essential role in prioritizing targets and predicting druggability. The eFindSite tool employs meta-threading to detect weakly homologous templates, clustering techniques, and supervised machine learning to predict drug-binding pockets and assess druggability [19]. The software uses features such as the fraction of templates assigned to a pocket, average template modeling score, residue confidence, and pocket confidence to generate druggability predictions with high accuracy (AUC=0.88) [19].

The PINNED approach utilizes a neural network architecture that generates interpretable druggability sub-scores based on four distinct feature categories: sequence and structure properties, localization, biological functions, and network information [20]. This multi-faceted approach achieves excellent performance (AUC=0.95) in separating drugged and undrugged proteins and provides insights into the factors influencing a protein's druggability [20].

The following workflow illustrates the integrated experimental and computational approach for chemical tool development:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Proteome Exploration

The systematic exploration of the druggable proteome requires a diverse toolkit of high-quality research reagents. The following table details key resources generated by initiatives like EUbOPEN and Target 2035:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Druggable Proteome Exploration

| Reagent Type | Description | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | Potent (≤100 nM), selective (≥30-fold), cell-active small molecules with inactive control compounds | Target validation, mechanistic studies, phenotypic screening follow-up |

| Chemogenomic Compound Libraries | Collections of well-annotated compounds with defined but not exclusive selectivity profiles | Target deconvolution, phenotypic screening, polypharmacology studies |

| Patient-Derived Assay Systems | Disease-relevant cellular models from primary human tissues | Compound profiling, mechanism of action studies, translational research |

| Open Access Data Portals | Public repositories containing compound characterization data, assay protocols, and structural information | Data mining, target prioritization, hypothesis generation |

| E3 Ligase Handles | Selective ligands for E3 ubiquitin ligases suitable for PROTAC design | Targeted protein degradation, novel modality development |

These research reagents collectively enable a systematic approach to proteome exploration, from initial target identification and validation to mechanistic studies and therapeutic development.

Impact and Future Perspectives

Current Coverage of the Human Proteome

Assessment of current chemical coverage reveals both progress and opportunities. Analysis indicates that approximately 2,331 human proteins (11.7%) are currently targeted by chemical tools or drugs, with 437 proteins targeted by chemical probes, 353 by chemogenomic compounds, and 2,112 by drugs [22]. There is significant overlap among these categories, with many proteins targeted by multiple modalities. The higher number of drug targets reflects both the larger number of available drugs (1,693) compared to chemical probes (554) or chemogenomic compounds (484) and the fact that drugs often exhibit polypharmacology, affecting multiple targets simultaneously [22].

Pathway coverage analysis reveals that existing chemical tools already impact a substantial portion of human biology. While available chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds target only 3% of the human proteome, they cover 53% of the human Reactome due to the fact that 46% of human proteins are involved in more than one cellular pathway [22]. This demonstrates the efficient coverage achieved by strategic target selection.

Protein Family-Specific Coverage

Certain protein families show particularly extensive chemical coverage. Kinases are among the most thoroughly explored, with approximately 67.7% of the 538 human kinases targeted by at least one small molecule [22]. In contrast, GPCRs show lower coverage, with only 20.3% of the 802 human GPCRs targeted by chemical tools despite their established importance as drug targets [22]. This disparity highlights both the historical focus on kinases in chemical probe development and the ongoing opportunities in other target classes.

Future Directions and Challenges

The Target 2035 initiative faces several significant challenges as it progresses toward its goal. The expansion of chemical modalities beyond traditional small molecules, including PROTACs, molecular glues, and covalent inhibitors, requires continuous adaptation of screening and characterization methods [17] [18]. The development of chemical tools for challenging target classes such as protein-protein interactions and transcription factors remains particularly difficult. Additionally, ensuring the widespread adoption and appropriate use of chemical probes requires ongoing education about best practices and the importance of using appropriate control compounds [17].

Future efforts will likely focus on integrating chemical genomics with functional genomics approaches, leveraging advances in CRISPR screening and multi-omics technologies to build comprehensive maps of protein function. The continued development of open science partnerships between academia and industry will be essential to addressing the scale of the challenge. As these efforts progress, they promise to transform our understanding of human biology and accelerate the development of new therapeutics for diseases with unmet medical needs.

The EUbOPEN consortium and the broader Target 2035 initiative represent a paradigm shift in how the scientific community approaches the exploration of human biology and therapeutic development. By generating high-quality, openly accessible chemical tools for a substantial fraction of the druggable proteome, these efforts are empowering researchers to investigate previously understudied proteins and pathways. The integrated approach—combining chemogenomic libraries for broad coverage with chemical probes for precise target validation—provides a powerful framework for systematic proteome exploration.

As these initiatives progress, they are likely to yield not only new chemical tools but also fundamental insights into human biology and disease mechanisms. The open science model ensures that these resources are available to the entire research community, maximizing their potential impact. While significant challenges remain, the progress to date demonstrates the feasibility of comprehensively mapping the druggable proteome and underscores the transformative potential of global collaboration in biomedical research.

The systematic screening of targeted chemical libraries against families of drug targets, a practice known as chemogenomics, has emerged as a powerful strategy for identifying novel drugs and deconvoluting the functions of orphan targets [1]. The foundational premise of chemogenomics is that ligands designed for one member of a protein family often exhibit activity against other family members, enabling the collective coverage of a target family through a carefully assembled compound set [1]. The success of this approach is critically dependent on access to high-quality, annotated bioactivity data for its foundational principle: that understanding the interaction between small molecules and their protein targets enables the prediction of activity for related compounds and targets. Public chemical and bioactivity databases provide the essential infrastructure for this endeavor, serving as the primary source for populating, annotating, and validating chemogenomic libraries.

This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of three core public databases—ChEMBL, PubChem, and DrugBank—framed within the practical context of assembling a chemogenomic screening library. We will detail their scope, data content, and comparative strengths, present structured protocols for their use in library construction, and visualize the integrated data relationships and workflows that underpin modern, data-driven chemogenomic research.

Database Core Components: A Comparative Analysis

A strategic approach to chemogenomic library assembly requires a clear understanding of the complementary strengths of available databases. The table below provides a quantitative and qualitative summary of the core databases.

Table 1: Core Public Database Comparison for Chemogenomic Library Assembly

| Feature | ChEMBL | PubChem | DrugBank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Bioactivity data from medicinal chemistry literature and confirmatory screens [23] [24] | Repository of chemical substances and their bioactivities from hundreds of data sources [24] | Detailed data on drugs, their mechanisms, targets, and interactions [25] |

| Key Content | Manually curated SAR data from journals; IC50, Ki, Kd, EC50 values [23] | Substance-data from depositors; Bioassay results; Biological test results [24] | FDA-approved/investigational drugs; drug-target mappings; ADMET data [26] [25] |

| Target Annotation | ~9,570 targets (as of 2013) [26] | ~10,000 protein targets (as of 2017) [24] | ~4,233 protein IDs (as of 2013) [26] |

| Compound Volume | ~1.25 million distinct compounds (as of 2013) [26] | ~94 million unique structures (as of 2017) [24] | ~6,715 drug entries (as of 2013) [26] |

| Data Curation | High-quality manual extraction from publications [23] [24] | Automated aggregation and standardization from depositors [24] | Manually curated from primary sources [25] |

| Utility in Library Design | Probe & Lead Identification: Source of SAR for lead optimization and selectivity analysis. | Hit Expansion & Scaffold Hopping: Massive chemical space for finding analogs and novel chemotypes. | Repurposing & Safety Screening: Source of clinically relevant compounds and off-target liability prediction. |

A Practical Workflow for Chemogenomic Library Assembly

The following section outlines a detailed, experimentally-validated methodology for constructing a targeted anticancer compound library, demonstrating how the core databases are leveraged in a real-world research scenario [27]. This process can be adapted for other target families and disease areas.

Phase 1: Defining the Target Space

Objective: Compile a comprehensive list of protein targets implicated in a disease phenotype (e.g., cancer).

- Source Data Integration: Initiate the target list using resources like The Human Protein Atlas and data from pan-cancer studies available in PharmacoDB [27].

- Target Space Expansion: Expand this initial set by incorporating proteins and gene products identified in additional pan-cancer studies and literature mining to ensure broad coverage of disease-relevant pathways [27].

- Functional Categorization: Annotate the final target set using Gene Ontology (GO) terms to ensure diversity in protein families, cellular functions, and coverage of key disease "hallmarks" [27].

Phase 2: Compound Curation and Filtering

Objective: Identify and filter small molecules that interact with the defined target space.

This phase employs two parallel, complementary strategies: a target-based approach for novel probe discovery and a drug-based approach for repurposing.

Table 2: Compound Curation Strategies for Library Assembly

| Strategy | Target-Based (Experimental Probe Compounds - EPCs) | Drug-Based (Approved/Investigational Compounds - AICs) |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Identify potent, selective chemical probes for target validation and discovery. | Identify drugs with known safety profiles for potential repurposing. |

| Source Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem, probe manufacturer catalogs. | DrugBank, clinical trial repositories, FDA approvals. |

| Initial Curation | Compile a "Theoretical Set" of all known compound-target interactions for the defined target space from databases [27]. | Manually curate a collection of approved and clinically investigated compounds from public sources and trials [27]. |

| Key Filters | 1. Activity Filtering: Remove compounds lacking cellular activity data or with low potency. |

2. Potency Selection: For each target, select the most potent compounds to reduce redundancy. 3. Availability Filtering: Retain only compounds that are commercially available for screening [27]. | 1. Duplicate Removal: Eliminate duplicate drug entries. 2. Structural Clustering: Use fingerprinting (e.g., ECFP4, MACCS) with a high similarity cutoff (e.g., Dice/Tanimoto >0.99) to remove highly similar structures, ensuring chemical diversity [27]. | | Output | A focused "Screening Set" of potent, purchasable probes. | A diverse collection of clinically annotated compounds. |

Phase 3: Library Finalization and Validation

Objective: Merge the EPC and AIC collections into a final, optimized physical library.

- Library Merging: Combine the filtered EPC and AIC sets.

- Redundancy Check: Perform a final check for overlapping compounds between the two sets to ensure a non-redundant final library.

- Target Coverage Analysis: Quantify the percentage of the original target space covered by the final compound library. A well-designed library can cover over 80% of a 1,655-protein target space with ~1,200 compounds [27].

- Physical Library Assembly: Procure the compounds and prepare stock solutions for high-throughput or high-content phenotypic screening.

The entire workflow, from target definition to physical screening, is visualized below.

Diagram 1: Chemogenomic Library Assembly Workflow. The process flows from target definition (yellow), through parallel compound curation paths for experimental probes (red) and clinical compounds (green), to final library assembly and validation (blue).

Database Interrelationships and Data Flow

Understanding how core databases interact is crucial for effective data mining and for recognizing potential circularity in data sourcing. The following diagram maps the primary relationships and data flows between these resources.

Diagram 2: Database Interrelationships. Arrows indicate the primary direction of data flow. Note the central aggregating role of PubChem and the close linkage between DrugBank and HMDB. Researchers integrate data from ChEMBL, DrugBank, and PubChem to build chemogenomic libraries.

Successful chemogenomic screening relies on more than just compound databases. The following table details key reagents and computational tools essential for library assembly and screening.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Chemogenomic Screening

| Resource / Reagent | Function in Chemogenomic Screening |

|---|---|

| ChEMBL | Source of structure-activity relationship (SAR) data and bioactive compounds for probe identification and selectivity analysis [23] [24]. |

| DrugBank | Provides detailed drug-target mappings, mechanism-of-action (MOA) data, and ADMET parameters for safety profiling and drug repurposing [25]. |

| PubChem | Large-scale repository for finding chemical analogs, validating compound activity across multiple assays, and accessing vendor information [24]. |

| HMDB & TTD | Complementary databases for metabolite information (HMDB) and focused primary target mappings for marketed and clinical trial drugs (TTD) [26] [28]. |

| IUPHARdb/Guide to PHARMACOLOGY | Provides expert-curated ligand-target activity mappings, serving as a high-quality reference for validation [28]. |

| Kinase/GPCR SARfari | Specialized ChEMBL workbenches providing integrated chemogenomic data (sequence, structure, compounds) for specific target families [23]. |

| CACTVS Cheminformatics Toolkit | Used for chemical structure normalization, canonical tautomer generation, and calculation of unique hash identifiers (e.g., FICTS, FICuS) for precise compound comparison [26]. |

| InChI/InChIKey | Standardized chemical identifier and hashed key for unambiguous compound registration and duplicate removal across different databases [26]. |

| Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP) | Molecular structural fingerprints used for chemical similarity searching, clustering, and diversity analysis during library design [27]. |

Chemogenomics is a drug discovery strategy that involves the systematic screening of targeted chemical libraries against families of related drug targets. The core premise is that similar proteins often bind similar ligands; therefore, libraries built with this principle can efficiently explore a vast target space [1]. A chemogenomic library is a collection of well-defined, annotated pharmacological agents designed to perturb the function of a wide range of proteins in a biological system [12]. The primary goal of such libraries is to enable the parallel identification of biological targets and biologically active compounds, thereby accelerating the conversion of phenotypic screening outcomes into target-based discovery programs [1] [12].

The strategic importance of understanding the coverage of these libraries cannot be overstated. The "druggable proteome" is currently estimated to comprise approximately 3,000 targets, yet the combined efforts of the private sector and academic community have thus far produced high-quality chemical tools for only a fraction of these [18] [6]. This represents a significant coverage gap in our ability to functionally probe the human proteome. Initiatives like Target 2035, a global consortium, have set the ambitious goal of developing a pharmacological modulator for most human proteins by the year 2035 [18]. A critical analysis of which target families are well-represented and which remain neglected is therefore fundamental to guiding future research investments and library development efforts.

Current Landscape of Chemogenomic Library Coverage

Quantitative Analysis of Target Family Representation

Systematic analysis of major chemogenomic initiatives reveals distinct patterns in target family coverage. Well-established protein families constitute the majority of current library contents, while several emerging families remain significantly underrepresented. The following table summarizes the representation status of key target families based on current chemogenomic library development efforts.

Table 1: Representation of Major Target Families in Current Chemogenomic Libraries

| Target Family | Representation Status | Key Coverage Metrics | Examples of Covered Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinases | Well-represented | Extensive coverage with multiple chemogenomic compounds (CGCs) and chemical probes | Various serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases |

| G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) | Well-represented | Multiple focused libraries exist with diverse modulators | Various neurotransmitter and hormone receptors |

| Epigenetic Regulators | Moderately represented | Growing coverage, particularly for bromodomain families | BET bromodomains, histone methyltransferases |

| E3 Ubiquitin Ligases | Emerging coverage | Limited ligands available; key focus area for expansion [18] | Selected E3 ligases with newly discovered ligands [18] |

| Solute Carriers (SLCs) | Emerging coverage | Very limited chemical tools; major focus of new initiatives [18] | Understudied transporters in nutrient and metabolite flux |

| Ion Channels | Moderately represented | Variable coverage across subfamilies | Selected voltage-gated and ligand-gated channels |

| Proteases | Moderately represented | Reasonable coverage for some protease classes | Various serine and cysteine proteases |

The EUbOPEN consortium, a major public-private partnership, aims to address these coverage gaps by creating the largest openly available set of high-quality chemical modulators. One of its primary objectives is to assemble a chemogenomic library covering approximately 30% of the druggable genome [18] [6]. This ambitious effort specifically focuses on creating novel chemical probes for challenging target classes such as E3 ubiquitin ligases and solute carriers (SLCs), which have historically been difficult to target with small molecules [18].

Analysis of Underrepresented Target Families

Several biologically significant target families remain notably underrepresented in current chemogenomic libraries, creating critical gaps in our ability to comprehensively probe human biology for therapeutic discovery.

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: With over 600 members in the human genome, E3 ubiquitin ligases represent a vast and functionally diverse family that controls protein degradation and numerous cellular processes. However, as noted in the EUbOPEN initiative, "only a few of the large family of E3 ligases have been successfully exploited so far" [18]. This severely limits the development of next-generation therapeutic modalities such as PROTACs (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras) and molecular glues, which require E3 ligase ligands for their mechanism of action [18]. The development of new E3 ligase ligands and the identification of linker attachment points ("E3 handles") has therefore become a major focus for library expansion [18].

Solute Carriers (SLCs): The SLC family represents one of the largest gaps in current chemogenomic coverage. With more than 400 membrane transporters, SLCs control the movement of nutrients, metabolites, and ions across cellular membranes and are implicated in a wide range of diseases. Despite their physiological importance, the EUbOPEN consortium explicitly identifies SLCs as a "focus area" for probe development, highlighting the severe shortage of high-quality chemical tools for this target family [18]. The difficulty in developing assays for membrane proteins and their complex transport mechanisms has historically impeded systematic drug discovery efforts for SLCs.

Understudied Target Families: Beyond E3s and SLCs, numerous other protein families remain poorly covered, including many protein-protein interaction modules, RNA-binding proteins, and allosteric regulatory sites. The expansion of the druggable proteome through new modalities continues to reveal additional families that lack adequate chemical tools.

Experimental Methodologies for Library Characterization and Validation

High-Content Phenotypic Profiling for Compound Annotation

Comprehensive characterization of chemogenomic libraries requires sophisticated phenotypic profiling to annotate compounds beyond their primary target interactions. The HighVia Extend protocol represents an advanced methodology for multi-parametric assessment of compound effects on cellular health [5].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Screening

| Research Reagent | Function in Assay | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hoechst33342 | DNA-staining dye for nuclear morphology analysis | Detection of apoptotic cells (nuclear fragmentation) and cell cycle analysis [5] |

| MitoTracker Red/DeepRed | Mitochondrial staining dyes | Assessment of mitochondrial mass and health; indicator of cytotoxic events [5] |

| BioTracker 488 Green Microtubule Dye | Tubulin-specific fluorescent dye | Evaluation of cytoskeletal integrity and detection of tubulin-disrupting compounds [5] |

| AlamarBlue HS Reagent | Cell viability indicator dye | Orthogonal measurement of metabolic activity and cell viability [5] |

| U2OS, HEK293T, MRC9 Cell Lines | Model cellular systems for phenotypic screening | Provide diverse cellular contexts for assessing compound effects [5] |

Protocol Workflow:

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Plate appropriate cell lines (e.g., U2OS, HEK293T, MRC9) in multiwell plates and allow for adherence.

- Compound Application: Treat cells with chemogenomic library compounds across a range of concentrations and time points (e.g., 24-72 hours).

- Multiplexed Staining: Simultaneously stain live cells with optimized concentrations of Hoechst33342 (50 nM), MitoTracker Red/DeepRed, and BioTracker 488 Green Microtubule Dye [5].

- Live-Cell Imaging: Acquire time-lapse images using high-content imaging systems to capture kinetic responses.

- Image Analysis and Machine Learning Classification: Use automated image analysis to identify individual cells and measure morphological features. Apply supervised machine-learning algorithms to gate cells into distinct populations: "healthy," "early apoptotic," "late apoptotic," "necrotic," and "lysed" [5].

- Data Integration: Correlate nuclear phenotype (e.g., "pyknosed" or "fragmented") with overall cellular phenotype to enable simplified scoring based on nuclear morphology alone.

High-Content Phenotypic Profiling Workflow

Network Pharmacology and Morphological Profiling for Target Deconvolution

Network pharmacology approaches provide a powerful computational framework for understanding and expanding chemogenomic library coverage. These methods integrate heterogeneous data sources to build comprehensive drug-target-pathway-disease networks that facilitate target identification and mechanism deconvolution.

Methodology for Network Construction:

- Data Integration: Combine chemical, biological, and phenotypic data from multiple sources including:

- ChEMBL database for bioactivity data (e.g., IC50, Ki values) [4]

- KEGG pathway database for molecular interaction and pathway information [4]

- Gene Ontology (GO) for functional annotation of protein targets [4]

- Disease Ontology (DO) for disease association data [4]

- Cell Painting morphological profiles from resources like the Broad Bioimage Benchmark Collection (BBBC022) [4]

Scaffold Analysis: Use tools like ScaffoldHunter to decompose molecules into representative scaffolds and fragments, creating a hierarchical relationship between chemical structures [4].

Graph Database Implementation: Employ Neo4j or similar graph databases to create nodes for molecules, scaffolds, proteins, pathways, and diseases, with edges representing relationships between these entities (e.g., "molecule targets protein," "protein acts in pathway") [4].

Enrichment Analysis: Perform GO, KEGG, and DO enrichment analyses using computational tools like the R package clusterProfiler to identify statistically overrepresented biological themes associated with compound activities [4].

Network Pharmacology Relationship Mapping

Strategies for Addressing Coverage Gaps and Future Directions

Library Expansion Approaches for Understudied Target Families

Addressing the significant coverage gaps in chemogenomic libraries requires coordinated, large-scale efforts that leverage both experimental and computational approaches. Several strategies have emerged as particularly promising for expanding the targetable proteome:

Public-Private Partnerships: Initiatives like the EUbOPEN consortium demonstrate the power of collaborative frameworks that bring together academic institutions and pharmaceutical companies. By working in a pre-competitive manner, these partnerships can pool resources, expertise, and compound collections to tackle challenging target families that individual organizations might avoid due to high risk or cost [18]. The EUbOPEN project specifically aims to deliver 50 new collaboratively developed chemical probes with a focus on E3 ligases and SLCs, alongside a chemogenomic library covering one-third of the druggable proteome [18].

Advanced Screening Technologies: The development of more physiologically relevant assay systems is crucial for probing difficult target families. Patient-derived primary cell assays for diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, and neurodegeneration provide disease-relevant contexts for evaluating compound efficacy and mechanism [18]. Furthermore, high-content technologies like the optimized HighVia Extend protocol enable comprehensive characterization of compound effects on cellular health, providing critical data for annotating library members [5].

Open Science and Data Sharing: The establishment of open-access resources for data and reagent sharing accelerates progress in library development. EUbOPEN, in alignment with Target 2035 principles, makes all chemical tools, data sets, and protocols freely available to the research community [18]. This open science model ensures broad utilization and validation of developed resources while preventing duplication of effort.

Integration of Genetic and Chemical Approaches: Combining chemogenomic screening with genetic perturbation technologies (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9) creates powerful convergent evidence for target validation [12]. Compounds that produce phenotypic effects consistent with genetic perturbation of their putative targets provide stronger evidence for on-target activity, while discrepancies may reveal important off-target effects or polypharmacology.

Quality Standards and Annotation Frameworks

As chemogenomic libraries expand to cover more target families, maintaining high-quality standards becomes increasingly important. The EUbOPEN consortium has established clear criteria for compounds included in their chemogenomic library [6]:

- Potency: Demonstrated activity in in vitro assays (typically <100 nM)

- Selectivity: At least 30-fold selectivity over related proteins

- Cellular Target Engagement: Evidence of target modulation in cells at <1 μM (or <10 μM for challenging targets like protein-protein interactions)

- Toxicity Window: Reasonable separation between efficacy and toxicity unless cell death is target-mediated [18]

These criteria are intentionally less stringent than those for chemical probes, enabling broader target coverage while still maintaining meaningful pharmacological specificity [6]. Additionally, comprehensive annotation of compound effects on basic cellular functions (cell viability, mitochondrial health, cytoskeletal integrity) provides crucial context for interpreting phenotypic screening results [5].