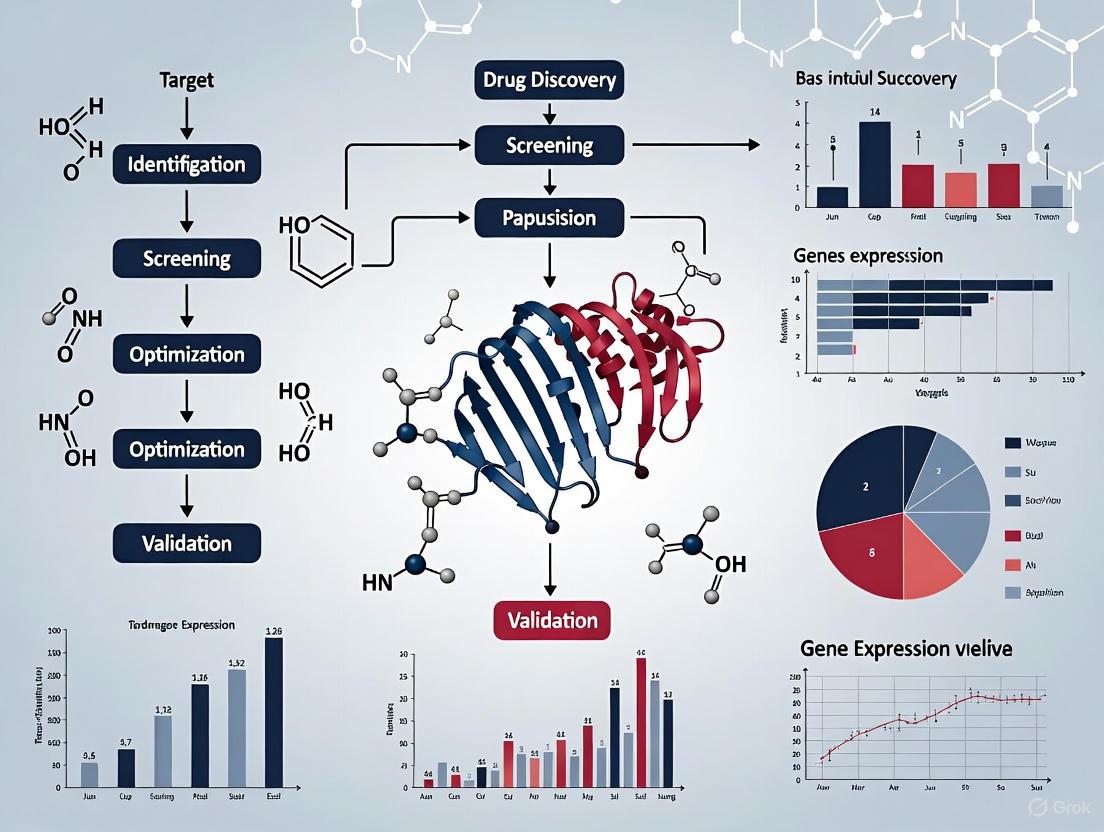

Chemical Genomics in Drug Discovery: A Systematic Guide to Target Identification, Validation, and Therapeutic Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how chemical genomics accelerates modern drug discovery by systematically linking small molecules to biological function.

Chemical Genomics in Drug Discovery: A Systematic Guide to Target Identification, Validation, and Therapeutic Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how chemical genomics accelerates modern drug discovery by systematically linking small molecules to biological function. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of using chemical probes to interrogate gene and protein function on a large scale. The content details key methodological approaches, including high-throughput screening of genetic libraries and AI-powered analysis, for identifying drug targets and mechanisms of action. It further addresses critical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing these complex workflows, and concludes with robust frameworks for target validation and comparative analysis against other discovery paradigms. By synthesizing current trends and recent successes, this guide serves as a strategic resource for leveraging chemical genomics to expand the druggable genome and deliver first-in-class therapeutics.

The Foundation of Chemical Genomics: Systematically Probing Biology with Small Molecules

Defining Chemical Genomics and its Role in Modern Drug Discovery

Chemical genomics is an interdisciplinary field that aims to transform biological chemistry into a high-throughput, industrialized process, analogous to the impact genomics had on molecular biology [1]. It systematically investigates the interactions between small molecules and biological systems, primarily proteins, on a genome-wide scale. This approach provides a powerful framework for understanding biological networks and accelerating the identification of new therapeutic targets.

In modern drug discovery, chemical genomics serves as a critical bridge between genomic information and therapeutic development. By using small molecules as probes to modulate protein function, researchers can systematically dissect complex biological pathways and validate novel drug targets. The field is characterized by its use of high-throughput experimental methods to quantify genome-wide biological features, such as gene expression, protein binding, and epigenetic modifications [2]. This systematic, large-scale interrogation of biological systems positions chemical genomics as a foundational component of contemporary drug development strategies, enabling more efficient target identification and validation while reducing late-stage attrition rates.

Key Technological Drivers and Current Trends

The practice of chemical genomics is being reshaped by several converging technological trends that enhance its scale, precision, and integration with drug discovery pipelines.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Artificial intelligence has evolved from a theoretical promise to a tangible force in drug discovery, with AI-driven platforms now capable of compressing early-stage research timelines from years to months [3]. Machine learning models inform target prediction, compound prioritization, and pharmacokinetic property estimation. For instance, Exscientia reported AI-driven design cycles approximately 70% faster than traditional methods, requiring 10-fold fewer synthesized compounds [3]. The integration of pharmacophoric features with protein-ligand interaction data has demonstrated hit enrichment rates boosted by more than 50-fold compared to traditional methods [4].

High-Throughput Experimental Methods

Modern chemical genomics relies on high-throughput techniques that measure biological phenomena across the entire genome [2]. These methods typically involve three key steps: (1) Extraction of genetic material (RNA/DNA), (2) Enrichment for the biological feature of interest (e.g., protein binding sites), and (3) Quantification through sequencing or microarray analysis [2]. The shift from microarrays to high-throughput sequencing has been particularly transformative, enabling direct sequence-based quantification rather than inference through hybridization.

Emerging Therapeutic Modalities

Several innovative therapeutic approaches emerging from chemical genomics principles are gaining prominence:

- PROTACs (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras): Small molecules that drive protein degradation by bringing target proteins together with E3 ligases. More than 80 PROTAC drugs are currently in development pipelines, with over 100 commercial organizations involved in this research area [5].

- Radiopharmaceutical Conjugates: These innovative molecules combine targeting moieties (antibodies, peptides, or small molecules) with radioactive isotopes, enabling highly localized radiation therapy while reducing off-target effects [5].

- CRISPR and Gene Editing: Personalized CRISPR therapies have advanced to clinical application, with one notable case involving a seven-month-old infant receiving personalized CRISPR base-editing therapy developed in just six months [5].

Table 1: Key Trends Reshaping Chemical Genomics and Drug Discovery

| Trend | Key Advancement | Impact on Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| AI-Driven Platforms | Generative AI for molecular design and optimization | Reduces discovery timelines from years to months; decreases number of compounds needing synthesis [4] [3] |

| Targeted Protein Degradation | PROTAC technology leveraging E3 ligases | Enables targeting of previously "undruggable" proteins; >80 drugs in development [5] |

| Cellular Target Engagement | CETSA for measuring drug-target binding in intact cells | Provides functional validation in physiologically relevant environments; bridges gap between biochemical and cellular efficacy [4] |

| Advanced Screening | High-throughput sequencing and single-cell analysis | Enables genome-wide functional studies; reveals cellular heterogeneity [2] |

Core Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Target Engagement Validation with CETSA

The Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) has emerged as a crucial methodology for validating direct target engagement of small molecules in intact cells and native tissue environments [4]. This protocol enables researchers to confirm that compounds interact with their intended protein targets under physiologically relevant conditions, addressing a major source of attrition in drug development.

Experimental Workflow:

- Compound Treatment: Expose cells or tissue samples to the test compound at various concentrations for a predetermined time period.

- Heat Challenge: Subject the samples to a range of elevated temperatures (e.g., 45-65°C) to denature proteins.

- Protein Extraction and Solubility Assessment: Lyse cells and separate soluble (native) proteins from insoluble (denatured) aggregates.

- Quantification: Analyze target protein levels in the soluble fraction using Western blot, mass spectrometry, or other detection methods.

- Data Analysis: Calculate thermal shift (ΔTm) values to determine compound-induced stabilization of the target protein.

Recent work by Mazur et al. (2024) applied CETSA in combination with high-resolution mass spectrometry to quantify drug-target engagement of DPP9 in rat tissue, confirming dose- and temperature-dependent stabilization both ex vivo and in vivo [4]. This approach provides quantitative, system-level validation that bridges the gap between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy.

High-Throughput Sequencing for Genomic Applications

High-throughput sequencing serves as the quantification backbone for numerous chemical genomics applications, enabling researchers to map compound-induced changes across the entire genome [2]. The general workflow encompasses:

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA or RNA and attach platform-specific adapters. The library preparation protocol varies depending on the biological question (e.g., RNA-seq for gene expression, ChIP-seq for protein-DNA interactions).

- Sequencing: Process libraries through high-throughput sequencers that generate millions of reads in parallel.

- Alignment and Mapping: Computational alignment of sequence reads to a reference genome.

- Quantitative Analysis: Generate count-based data (e.g., reads per gene for RNA-seq) or positional information (e.g., coverage profiles for binding sites).

The evolution of sequencing technologies toward longer reads and single-cell resolution is particularly impactful for chemical genomics, enabling researchers to resolve cellular heterogeneity and detect rare cell populations in response to compound treatment [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Chemical Genomics Applications

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Libraries | Diverse collections of chemical compounds for screening | Target identification, hit discovery [1] |

| Cell Line Panels | Genetically characterized cellular models | Mechanism of action studies, toxicity profiling |

| Antibodies (Selective) | Protein detection and quantification | Western blot, immunoprecipitation, CETSA readouts [4] |

| Sequencing Kits | Library preparation for high-throughput sequencing | RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq [2] |

| PROTAC Molecules | Targeted protein degradation tools | Probing protein function, therapeutic development [5] |

| CRISPR Reagents | Gene editing tools | Target validation, functional genomics [5] |

Integration with Modern Drug Discovery Pipelines

Chemical genomics principles are being integrated throughout the drug discovery pipeline, from target identification to lead optimization. This integration is facilitated by cross-disciplinary teams that combine expertise in computational chemistry, structural biology, pharmacology, and data science [4].

AI-Enhanced Discovery Workflows

Leading AI-driven drug discovery companies have demonstrated the power of integrating chemical genomics with computational approaches. Insilico Medicine advanced an idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis drug from target discovery to Phase I trials in just 18 months using generative AI [3]. Similarly, Exscientia designed a clinical candidate CDK7 inhibitor after synthesizing only 136 compounds, significantly fewer than the thousands typically required in traditional medicinal chemistry programs [3]. These platforms leverage chemical genomics data to train machine learning models that predict compound efficacy and optimize pharmacological properties.

Data Integration and Multi-Omics Approaches

Modern chemical genomics relies on the integration of diverse data types to build comprehensive models of compound action. As illustrated below, this involves combining information from genetic, proteomic, and phenotypic analyses:

Future Perspectives and Strategic Implications

The continued evolution of chemical genomics promises to further transform drug discovery through several key developments. Single-cell sequencing technologies are revealing cellular heterogeneity and enabling the identification of rare cell populations, moving beyond population-averaged measurements [2]. The expansion of E3 ligase tools for targeted protein degradation beyond the four currently predominant ligases (cereblon, VHL, MDM2, and IAP) to include DCAF16, DCAF15, KEAP1, and FEM1B will enable targeting of previously inaccessible proteins [5]. Furthermore, the integration of patient-derived biological systems into chemical genomics workflows, exemplified by Exscientia's acquisition of Allcyte to enable screening on patient tumor samples, enhances the translational relevance of discovery efforts [3].

For research and development organizations, alignment with chemical genomics principles enables more informed go/no-go decisions, reduces late-stage attrition, and compresses development timelines. The convergence of computational prediction with high-throughput experimental validation represents a paradigm shift from traditional, linear drug discovery to an integrated, data-driven approach. As these trends continue to mature, chemical genomics will increasingly serve as the foundation for a more efficient and successful therapeutic development ecosystem.

Chemical genomics (or chemical genetics) is a research approach that uses small molecules as perturbagens to probe biological systems and elucidate gene function. It provides a powerful complementary strategy to traditional genetic perturbations. By investigating the interactions between chemical compounds and genomes, researchers can rapidly and reversibly modulate protein function, offering unique insights into biological networks and accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic targets [6]. This systematic assessment of gene-chemical interactions is fundamental to modern phenotypic drug discovery, shifting the paradigm from targeting single proteins to understanding complex cellular responses [7].

The core value of chemical genomics lies in its distinct advantages over genetic methods. Small molecules can (i) target specific domains of multidomain proteins, (ii) allow precise temporal control over protein function, (iii) facilitate comparisons between species by targeting orthologous proteins, and (iv) avoid indirect effects on multiprotein complexes by not altering the targeted protein's concentration [6]. When applied systematically, these perturbations generate rich datasets that illuminate functional relationships within biological systems, providing a critical foundation for therapeutic discovery.

Foundational Frameworks and Analytical Approaches

The Paradigm of Combination Chemical Genetics

While single perturbations identify components essential for a phenotype, functional connections between components are best identified through combination effects. Combination Chemical Genetics (CCG) is defined as the systematic application of multiple chemical or mixed chemical and genetic perturbations to gain insight into biological systems and facilitate medical discoveries [6]. This approach allows researchers to distinguish whether two non-essential genes have serial or parallel functionalities and to resolve complex systems into functional modules and pathways.

CCG experiments are broadly classified into two complementary approaches, mirroring classical genetics:

- Forward Chemical Genetics: Screens numerous uncharacterized chemical probes against one or a few phenotypes to identify active agents and associate them with biological pathways.

- Reverse Chemical Genetics: Characterizes the function of specific genes or proteins by monitoring multiple phenotypic outputs after targeted chemical modulation.

The power of CCG is greatly enhanced by its use of diverse chemical libraries and the integration of high-dimensional phenotypic readouts, such as whole-genome transcriptional profiling [6].

Computational Prediction of Perturbation Responses

A significant challenge in functional genomics is predicting transcriptional responses to unseen genetic perturbations. Modern computational methods, including deep learning architectures like compositional perturbation autoencoder (CPA), GEARS, and scGPT, aim to infer these responses by leveraging biological networks and large-scale single-cell atlases [8]. However, a critical framework called Systema highlights a major confounder: systematic variation.

Systematic variation refers to consistent transcriptional differences between perturbed and control cells arising from selection biases or biological confounders (e.g., cell-cycle phase differences, stress responses). This variation can lead to overestimated performance of prediction models if they merely capture these broad biases instead of specific perturbation effects [8]. The Systema framework emphasizes the importance of:

- Focusing on perturbation-specific effects rather than average treatment effects.

- Using heterogeneous gene panels for evaluation.

- Ensuring models can reconstruct the true biological perturbation landscape.

This rigorous evaluation is essential for developing predictive models that offer genuine biological insight rather than replicating experimental artifacts [8].

Table 1: Key Analytical Frameworks in Chemical Genomics

| Framework Name | Primary Function | Key Insight/Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Combination Chemical Genetics (CCG) [6] | Systematically applies multiple perturbations to map functional relationships. | Identifies interactions between pathways; distinguishes serial vs. parallel gene functions. |

| Systema [8] | Evaluation framework for perturbation response prediction methods. | Quantifies and controls for systematic variation (biases) that inflate performance metrics. |

| GGIFragGPT [7] | Generative AI model for transcriptome-conditioned molecule design. | Integrates gene interaction networks with fragment-based chemistry for biologically relevant drug candidates. |

AI-Driven Molecule Generation Conditioned on Transcriptomic Profiles

The ultimate application of systematic gene-chemical assessment is the direct generation of novel therapeutic compounds. GGIFragGPT represents a state-of-the-art approach that uses a GPT-based architecture to generate molecules conditioned on transcriptomic perturbation profiles [7]. This model integrates biological context by using pre-trained gene embeddings (from Geneformer) that capture gene-gene interaction information.

Key features of this approach include:

- Fragment-Based Assembly: Constructs molecules from chemically valid building blocks, ensuring high validity and synthesizability.

- Cross-Attention Mechanisms: Allows the model to focus on biologically relevant genes during the generation process, enhancing interpretability.

- Transcriptomic Conditioning: Generates molecules predicted to induce or reverse specific cellular phenotypes based on gene expression signatures.

In performance evaluations, GGIFragGPT achieved near-perfect validity (99.8%) and novelty (99.5%), with superior uniqueness (86.4%) compared to other models, successfully generating chemically feasible and diverse compounds aligned with a given biological context [7].

Essential Methodologies and Protocols

This section details the practical workflows for conducting systematic gene-chemical interaction studies, from high-throughput screening to computational analysis and validation.

High-Throughput Combination Screening Protocol

Objective: To identify synergistic or antagonistic interactions between genetic perturbations and chemical compounds. Applications: Target identification, mechanism of action studies, and combination therapy discovery.

Procedure:

- Perturbation Setup:

- Seed cells in 384-well plates using automated liquid handling.

- Genetically perturb cells using siRNA, shRNA, or CRISPR libraries targeting a defined gene set (e.g., kinases, cancer-associated genes).

- After 24-48 hours, add chemical compounds from a bioactive library (e.g., known drugs, mechanistic probes) using a concentration matrix (e.g., single dose or serial dilution).

Phenotypic Assaying:

- Incubate for a predetermined period (e.g., 72 hours).

- Measure phenotypic endpoints using high-content imaging, cell viability assays (e.g., CellTiter-Glo), or transcriptomic profiling (e.g., L1000 assay).

Data Acquisition:

- Collect raw data (luminescence, fluorescence, image files, gene expression counts).

- Normalize data to plate-based positive (e.g., cytotoxic compound) and negative (non-targeting siRNA + DMSO) controls.

Interaction Analysis:

- Calculate combination indices (e.g., Bliss Independence, Loewe Additivity) to quantify synergy.

- Use statistical models (e.g., linear mixed-effects models) to identify significant gene-chemical interactions beyond single-agent effects.

Computational Workflow for Predicting Genetic Perturbation Responses

Objective: To train and evaluate a model that predicts single-cell transcriptomic responses to unseen genetic perturbations.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Obtain single-cell RNA-seq data from a perturbation screen (e.g., Adamson, Norman, or Replogle datasets) [8].

- Perform standard normalization (e.g., SCTransform) and batch correction.

- Split perturbations into training and test sets, ensuring some perturbations are unseen during training.

Model Training:

- Input the gene expression matrix and perturbation annotations for training cells.

- Train a model (e.g., CPA, GEARS, or a simpler baseline like the "perturbed mean") to predict the expression profile of a perturbed cell.

- The model learns to minimize the difference between predicted and actual expression.

Evaluation with Systema Framework:

- Predict expression profiles for cells with unseen perturbations from the test set.

- Calculate the average treatment effect for each perturbation (mean difference between perturbed and control cells).

- Compare the predicted treatment effect to the ground truth using metrics like Pearson correlation (PearsonΔ).

- Apply the Systema framework to ensure the model captures perturbation-specific effects and not just systematic variation between control and perturbed populations [8].

CETSA for Target Engagement Validation in Cells and Tissues

Objective: To confirm direct binding of a drug molecule to its intended protein target in a physiologically relevant context.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Treat intact cells or tissue samples with the compound of interest across a range of concentrations and time points.

- Include a DMSO-only treatment as a negative control.

Thermal Denaturation:

- Heat-alignot samples to different temperatures (e.g., from 45°C to 65°C).

- Rapidly cool samples on ice to denature and precipitate proteins that have become unstable due to heating.

Solubilization and Analysis:

- Lyse cells and separate soluble (stable) protein from precipitated protein by centrifugation.

- Quantify the amount of soluble target protein in each sample using a specific detection method, such as immunoblotting or high-resolution mass spectrometry [4].

Data Interpretation:

- Plot the fraction of soluble protein remaining against temperature.

- A compound that binds and stabilizes the target protein will shift the denaturation curve to higher temperatures, indicating positive target engagement.

- As demonstrated by Mazur et al. (2024), this method can confirm dose-dependent stabilization of a target (e.g., DPP9) even in complex environments like animal tissues [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful systematic assessment requires a suite of well-characterized reagents and tools. The table below catalogs essential resources for constructing and analyzing gene-chemical interaction networks.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Chemical Genomics

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Sources / Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Perturbation Libraries | Knockout (KO), RNAi, or CRISPR tools to modulate gene expression. | Genome-wide KO libraries in yeast & E. coli; RNAi libraries for C. elegans, Drosophila, human cells [6]. |

| Bioactive Chemical Libraries | Diverse sets of small molecules to perturb protein function. | Approved drugs (e.g., DrugBank), known bioactives (e.g., PubChem), commercial diversity libraries [6]. |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq Datasets | Profiles transcriptional outcomes of perturbations at single-cell resolution. | Datasets from Adamson, Norman, Replogle, Frangieh, etc., spanning multiple technologies and cell lines [8]. |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | Validates direct drug-target engagement in intact cells and tissues. | Used to quantify dose- and temperature-dependent stabilization of targets like DPP9 in complex biological systems [4]. |

| AI-Driven Discovery Platforms | Integrates AI for target ID, molecule generation, and lead optimization. | Exscientia, Insilico Medicine, Recursion, BenevolentAI, Schrödinger [3]. |

| Gene Interaction Networks | Prior biological knowledge of gene-gene relationships for contextualizing data. | Pre-trained models like Geneformer; embeddings used in models like GGIFragGPT [7]. |

Visualizing Workflows and Interactions

The following diagrams, defined using the DOT language and adhering to the specified color and contrast guidelines, illustrate core workflows and logical relationships in chemical genomics.

Diagram 1: Chemical Genomics Screening & Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: AI-Driven Molecule Generation from Transcriptomic Data

Diagram 3: Systematic Variation in Perturbation Studies

Chemical genomics leverages small molecules to elucidate biological function and identify therapeutic candidates, positioning it as a cornerstone of modern drug discovery. This field relies on enabling technologies that allow researchers to efficiently screen vast molecular spaces against biological targets. The journey from early encoded libraries to contemporary high-throughput sequencing platforms represents a paradigm shift in how scientists approach the identification of bioactive compounds. DNA-encoded libraries (DELs) have established a powerful framework by combining combinatorial chemistry with DNA barcoding, enabling the screening of billions of compounds in a single tube [9] [10]. However, the inherent limitations of DNA tags—particularly their incompatibility with nucleic acid-binding targets and constraints on synthetic chemistry—have driven innovation toward barcode-free alternatives [11].

The integration of high-throughput sequencing and advanced mass spectrometry has further accelerated this evolution, creating a robust technological ecosystem for chemical genomics. These developments are not merely incremental improvements but transformative advances that expand the accessible target space and enhance the drug discovery pipeline. This technical guide examines the core methodologies, experimental protocols, and key reagents that underpin these enabling technologies, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for their implementation in drug discovery research.

Core Technology Platforms: Principles and Architectures

DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs): Barcoded Molecular Repositories

DNA-Encoded Libraries represent a convergence of combinatorial chemistry and molecular biology, where each small molecule in a vast collection is tagged with a unique DNA sequence that serves as an amplifiable identification barcode [9] [10]. This architecture enables the entire library—often containing billions to trillions of distinct compounds—to be screened simultaneously in a single vessel against a protein target of interest [10].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of DNA-Encoded Library Platforms

| Characteristic | Description | Impact on Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Library Size | Billions to trillions of compounds [10] | Vastly expanded chemical space exploration |

| Encoding Method | DNA barcodes attached via ligation or enzymatic methods [9] | Amplifiable identification system |

| Screening Format | Single-vessel affinity selection with immobilized targets [9] [10] | Dramatically reduced resource requirements |

| Hit Identification | PCR amplification + next-generation sequencing [9] | High-sensitivity detection of binders |

| Chemical Compatibility | DNA-compatible reaction conditions required [9] | Constrained synthetic methodology |

DELs are primarily constructed using two encoding paradigms: single-pharmacophore libraries and dual-pharmacophore libraries. In single-pharmacophore libraries, individual chemical moieties are coupled to distinctive DNA fragments, while in dual-pharmacophore libraries, two different chemical entities are attached to complementary DNA strands that can synergistically interact with protein targets [9]. The construction typically employs split-and-pool synthesis methodologies, where each chemical building block addition is followed by DNA barcode ligation, creating massive diversity through combinatorial explosion [9].

Self-Encoded Libraries (SELs): Barcode-Free Annotation

A recent innovation addressing DEL limitations is the Self-Encoded Library (SEL) platform, which eliminates physical DNA barcodes in favor of tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) with automated structure annotation [11]. This approach screens barcode-free small molecule libraries containing 10^4 to 10^6 members in a single run through direct structural analysis, circumventing the fundamental constraints of DNA-encoded systems [11].

SEL technology leverages solid-phase combinatorial synthesis to create drug-like compounds, employing a broad range of chemical transformations without DNA compatibility restrictions [11]. The critical innovation lies in using high-resolution mass spectrometry and custom computational annotation to identify screening hits based on their fragmentation spectra rather than external barcodes [11]. This approach is particularly valuable for targets involving nucleic acid-binding proteins, which are inaccessible to DEL technologies due to false positives from DNA-protein interactions [11].

Table 2: Comparison of DEL vs. SEL Technology Platforms

| Parameter | DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) | Self-Encoded Libraries (SELs) |

|---|---|---|

| Encoding Principle | DNA barcodes as amplifiable identifiers [9] [10] | Tandem MS fragmentation spectra [11] |

| Maximum Library Size | Trillions of compounds [10] | Millions of compounds [11] |

| Synthetic Constraints | DNA-compatible chemistry required [9] | Standard solid-phase synthesis applicable [11] |

| Target Limitations | Problematic for nucleic acid-binding proteins [11] | Compatible with all target classes [11] |

| Hit Identification Method | PCR + next-generation sequencing [9] | NanoLC-MS/MS + computational annotation [11] |

| Isobaric Compound Resolution | Limited by barcode diversity | High (distinguishes hundreds of isobaric compounds) [11] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

DNA-Encoded Library Screening Protocol

The standard DEL screening workflow consists of four key stages that transform a complex molecular mixture into identified hit compounds.

Detailed Methodology:

Screen: The DEL containing billions of compounds is incubated with the immobilized protein target (typically tagged with biotin for capture on streptavidin-coated beads) in an appropriate binding buffer. Incubation periods typically range from 1-24 hours at controlled temperatures to reach binding equilibrium [9] [10].

Isolate: Non-binding library members are removed through multiple washing steps with buffer containing mild detergents to minimize non-specific interactions. Bound compounds are subsequently eluted using denaturing conditions such as high temperature (95°C) or extreme pH, which disrupt protein-ligand interactions without damaging the DNA barcodes [9].

Amplify & Sequence: The eluted DNA barcodes are purified and amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers compatible with next-generation sequencing platforms. The amplified DNA is then sequenced, generating millions of reads that represent the enriched library members [9] [10].

Identify: Bioinformatics analysis processes the sequencing data, counting barcode frequencies to identify significantly enriched sequences. These barcode sequences are then decoded to reveal the chemical structures of the binding compounds, which are prioritized for downstream validation [9].

Self-Encoded Library Screening Protocol

The SEL workflow replaces DNA-based encoding with direct structural analysis through mass spectrometry, creating a barcode-free alternative for hit identification.

Detailed Methodology:

Library Design & Synthesis: SELs are constructed using solid-phase split-and-pool synthesis with scaffolds designed for drug-like properties. For example, SEL-1 employs sequential attachment of two amino acid building blocks followed by a carboxylic acid decorator using Fmoc-based solid-phase peptide synthesis protocols. Building blocks are selected using virtual library scoring based on Lipinski parameters (molecular weight, logP, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, topological polar surface area) to optimize drug-like properties [11].

Affinity Selection: The library is panned against the immobilized target protein using similar principles to DEL selections. Critical washing steps remove non-binders, and specific binders are eluted under denaturing conditions. This process has been successfully applied to challenging targets like flap endonuclease 1 (FEN1), a DNA-processing enzyme inaccessible to DEL technology [11].

MS Analysis: The eluted sample containing potential binders is analyzed via nanoLC-MS/MS, which generates both MS1 (precursor) and MS2 (fragmentation) spectra. Each run typically produces approximately 80,000 MS1 and MS2 scans, requiring sophisticated data processing pipelines to distinguish signal from noise [11].

Computational Annotation: Unlike traditional metabolomics, SEL annotation uses the computationally enumerated library as a custom database. Tools like SIRIUS and CSI:FingerID annotate compounds by matching experimental fragmentation patterns against predicted spectra of library members, enabling identification without reference spectra [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of barcoded library technologies requires specific reagents and materials optimized for these specialized applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Library Technologies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-Compatible Building Blocks | Chemical substrates for library synthesis | Must withstand aqueous conditions and not degrade DNA; specialized collections available [9] |

| Encoding DNA Fragments | Unique barcodes for compound identification | Typically 6-7 base pair sequences for each building block; double-stranded with overhangs for ligation [9] |

| Immobilized Target Proteins | Affinity selection bait | Often biotinylated for capture on streptavidin-coated beads; requires maintained structural integrity [9] [10] |

| Solid-Phase Synthesis Resins | Platform for combinatorial library construction | Functionalized with linkers compatible with diverse chemical transformations [11] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kits | Barcode amplification and sequencing | Platform-specific kits (Illumina, Ion Torrent) for high-throughput barcode sequencing [9] |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Instrument calibration and data quality control | Essential for reproducible SEL analysis; isotope-labeled internal standards recommended [11] |

The evolution from barcoded libraries to barcode-free screening platforms represents a significant maturation in chemical genomics capabilities. DNA-encoded libraries continue to offer unparalleled library size and sensitivity, while self-encoded libraries address critical target class limitations and expand synthetic possibilities. These technologies do not operate in isolation but form complementary components in the drug discovery arsenal.

The integration of these experimental platforms with advanced computational methods, including large language models and machine learning, further enhances their potential [12]. As these technologies continue to evolve, they promise to accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic agents against an expanding range of biological targets, ultimately strengthening the bridge between chemical genomics and clinical application in the drug discovery pipeline.

Distinguishing Chemical Genetics from the Broader Chemical Genomics Field

The completion of the human genome project created an urgent need for systematic methods to characterize the function of novel genes and proteins, propelling the development of integrated chemical and genomic approaches. [13] Within this landscape, chemical genomics and chemical genetics are related but distinct disciplines often used interchangeably, yet they represent different methodological frameworks and objectives in biological research and drug discovery. [14]

Chemical genomics serves as a broader umbrella term encompassing various large-scale in vivo approaches used in drug discovery, including the systematic screening of compound libraries for bioactivity against specific cellular targets or phenotypes. [14] In contrast, chemical genetics refers specifically to the systematic assessment of how genetic variance impacts drug activity, measuring the cellular outcome of combining genetic and chemical perturbations in tandem. [14] This review delineates the technical distinctions between these fields, their methodological frameworks, and their unique contributions to modern drug discovery.

Core Conceptual Frameworks

Foundational Principles and Distinctions

At its core, chemical genetics employs small molecules as probes to perturb protein function, allowing researchers to study the resulting phenotypic effects on biological systems. [15] [16] These small molecules, whether man-made or derived from natural sources, bind to proteins and modify their function, enabling investigation at molecular, cellular, or organismal levels. [16] The field parallels classical genetics but fundamentally differs in its focus: while classical genetics manipulates genes to study resulting phenotypes, chemical genetics directly targets proteins using chemical tools. [16]

The key advantage of chemical genetics lies in its temporal control and reversibility. Chemical perturbations can be applied with precise timing and often reversed by removing the compound, enabling the study of dynamic biological processes and essential gene functions that would be lethal if permanently disrupted through genetic knockout. [6] This temporal resolution is particularly valuable for studying processes like signal transduction, cell cycle regulation, and developmental biology. [6]

Table 1: Key Distinctions Between Chemical Genomics and Chemical Genetics

| Feature | Chemical Genomics | Chemical Genetics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Systematic screening of chemical libraries against target families [13] | Systematic assessment of genetic variance on drug activity [14] |

| Scope | Broad umbrella term for multiple approaches [14] | Specific vignette of chemical-genomic interactions [14] |

| Screening Approach | Target family-focused (kinases, GPCRs, etc.) [13] | Gene-drug interaction focused [14] |

| Perturbation Type | Primarily chemical [13] | Combined chemical and genetic [14] |

| Typical Libraries | Targeted chemical libraries [13] | Genome-wide mutant libraries + compounds [14] |

Forward vs. Reverse Approaches

Chemical genetics employs two principal research strategies, mirroring classical genetics but with distinct methodological implementations:

Forward chemical genetics begins with phenotypic observation after small molecule application. Researchers expose cells or model organisms to diverse compound libraries and observe for desired phenotypic effects without presupposing molecular targets. [13] [16] Once a phenotypic effect is identified, the challenge becomes identifying the specific protein target responsible, a process known as target deconvolution. [13] This approach is particularly powerful for discovering novel biological mechanisms without prior knowledge of the proteins involved.

Reverse chemical genetics starts with a protein of interest and seeks small molecules that specifically modulate its function. [13] [16] Researchers screen compound libraries against purified proteins or in cellular contexts where the target protein is overexpressed or specifically tracked. Validated hits are then tested in cells or whole organisms to determine the biological phenotypes resulting from target modulation. [13] This approach is particularly valuable for validating potential drug targets and understanding the functional consequences of modulating specific proteins.

Figure 1: Forward vs. Reverse Chemical Genetics Workflows

Methodological Implementations and Workflows

Experimental Designs in Chemical Genetics

Chemical genetic approaches rely on systematically measuring how the fitness of an organism changes when genetic perturbations are combined with chemical treatments. [14] The foundational methodology involves creating comprehensive genetic perturbation libraries and quantitatively phenotyping them under chemical exposure.

Genetic variation for these screens comes in multiple forms, ranging from controlled to natural variation. The most powerful implementations use genome-wide libraries containing mutants for each gene, which can consist of loss-of-function (knockout, knockdown) or gain-of-function (overexpression) mutations in either arrayed or pooled formats. [14] In the past decade, such mutant libraries have been constructed for a plethora of bacteria and fungi, with recent advances enabling creation for almost any microorganism. [14]

Barcoding approaches, pioneered in bacteria and perfected in yeast, combined with advances in sequencing technologies, now enable tracking of relative abundance and fitness of individual mutants in pooled libraries with unprecedented throughput. [14] Differences in mutant abundance in the presence versus absence of a drug reveal genes required for, or detrimental to, withstanding the drug's cytotoxic effects. [14] For arrayed formats, experimental automation and advanced image processing software allow high-throughput phenotypic profiling of hundreds to thousands of mutants on the same plate. [14]

Table 2: Genetic Perturbation Libraries for Chemical Genetics

| Organism Type | Example Species | Library Size | Genome Coverage | Perturbation Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Escherichia coli | ~3,900 mutants | 93% | Knockout [6] |

| Bacteria | Staphylococcus aureus | ~2,600 mutants | 95% | ORF [6] |

| Fungi | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | ~6,100 mutants | 98% | Knockout/Overexpression [6] |

| Fungi | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | ~5,000 mutants | 95% | Knockout [6] |

| Worm | Caenorhabditis elegans | ~11,000 strains | 50% | RNAi [6] |

| Fly | Drosophila | ~13,000 strains | 95% | RNAi/ORF [6] |

| Vertebrate | Homo sapiens | ~22,000 strains | 90% | RNAi/ORF [6] |

Advanced Screening Technologies

Recent technological advances have dramatically enhanced the resolution and scale of chemical genetic screens. While traditional approaches focused on bulk growth phenotypes, current methods enable single-cell readouts and multi-parametric phenotyping through high-throughput microscopy and image analysis. [14] These approaches can utilize cell markers and classifiers of drug responses to provide deeper insights into biological activity. [14]

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) has emerged as a particularly powerful tool for chemical genetics, enabling titratable knockdown of both essential and non-essential genes. [17] This technology was effectively deployed in Mycobacterium tuberculosis to create a genome-scale CRISPRi library allowing hypomorphic silencing of in vitro essential genes, thus enabling quantification of chemical-genetic interactions for both essential and non-essential genes. [17] This approach identified 1,373 genes whose knockdown sensitized Mtb to drugs and 775 genes whose knockdown conferred resistance. [17]

High-content phenotypic screening platforms now integrate cell morphology data, omics layers, and contextual metadata through AI-powered analysis. [18] For example, Cell Painting assays visualize multiple cellular components, with image analysis pipelines detecting subtle morphological changes to generate profiles that identify biologically active compounds. [18] These integrated approaches can elucidate mechanisms of action (MoA) without presupposing molecular targets.

Figure 2: CRISPRi Chemical Genetics Screening Workflow

Applications in Drug Discovery and Target Identification

Mechanism of Action (MoA) Identification

Chemical genetics provides two primary pathways for elucidating the mechanisms of drug action. First, libraries in which essential gene levels can be modulated enable target identification through either hypersensitivity upon knockdown or resistance upon overexpression. [14] For example, HaploInsufficiency Profiling (HIP) in diploid organisms uses heterozygous deletion mutant libraries to reduce gene dosage, making cells more sensitive to drugs targeting the haploinsufficient gene. [14] In bacterial systems, which are haploid, target overexpression often confers resistance and has been repeatedly used to identify targets of new compounds. [14]

The second approach compares drug signatures - the compiled quantitative fitness scores for each mutant in a genome-wide deletion library when treated with a drug. [14] Drugs with similar signatures likely share cellular targets and/or cytotoxicity mechanisms in a "guilt-by-association" framework. [14] This approach becomes increasingly powerful as more drugs are profiled, enabling identification of repetitive "chemogenomic signatures" reflective of general drug mechanisms. [14] Machine-learning algorithms like Naïve Bayesian and Random Forest classifiers can recognize the chemical-genetic interactions most reflective of a drug's MoA and have been trained to predict drug-drug interactions. [14]

Dissecting Drug Resistance and Synergy

Chemical genetics excels at identifying intrinsic and acquired drug resistance mechanisms by revealing genes and pathways that control intracellular drug concentrations. [14] Studies in yeast revealed that up to 12% of the genome confers multi-drug resistance, while fewer genes serve similar pleiotropic roles in Escherichia coli, suggesting prokaryotes have more diverse drug resistance mechanisms. [14] Comparing deletion and overexpression libraries reveals that many drug transporters in bacteria are "cryptic" - having the capacity to confer resistance but remaining silent due to non-optimal expression patterns. [14]

Furthermore, chemical genetics can assess cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity networks between drugs by measuring how mutations affect sensitivity to multiple compounds. [14] This approach can identify opportunities to mitigate or even reverse drug resistance through strategic drug combinations. [14] For example, a CRISPRi chemical genetics platform in Mtb identified hundreds of genes influencing drug potency, revealing potential targets for synergistic combinations. [17] Combining these data with comparative genomics of clinical isolates uncovered previously unknown mechanisms of acquired resistance, including one associated with a multidrug-resistant tuberculosis outbreak in South America. [17]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Genetics

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Libraries | Known bioactives, FDA-approved drugs, diversity-oriented synthesis compounds [6] | Provide chemical perturbations for screening | Include both characterized and novel compounds for balanced screening [6] |

| Genetic Perturbation Libraries | E. coli KO collection (~3,900 mutants), Yeast KO collection (~6,100 mutants) [6] | Provide genetic perturbations for combination screening | Coverage essential and non-essential genes; arrayed vs pooled formats [14] |

| CRISPRi Libraries | Genome-scale Mtb CRISPRi library [17] | Titratable knockdown of essential and non-essential genes | Enables hypomorphic silencing for essential gene study [17] |

| Barcoded Mutant Libraries | Barcoded yeast deletion collection [14] | Tracking mutant fitness via sequencing | Enables highly parallel fitness assays [14] |

| Model Organisms | Xenopus embryos, Zebrafish embryos [15] | Whole-organism phenotypic screening | Transparent, fast development, easy visual scoring [15] |

| Target Engagement Assays | CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) [4] | Validate direct binding in intact cells | Confirms physicochemical drug-target interactions [4] |

Integrated Experimental Protocol: CRISPRi Chemical Genetics

The following detailed protocol outlines a comprehensive chemical genetics screen based on the Mtb CRISPRi platform published in Nature Microbiology [17], which can be adapted for other microbial systems:

Library Construction and Validation

- Step 1: Clone a genome-scale CRISPRi library containing approximately 10 sgRNAs per gene targeting both essential and non-essential genes, plus non-targeting control sgRNAs. Use a inducible dCas9 system for titratable knockdown. [17]

- Step 2: Sequence the library to confirm sgRNA representation and even distribution. The published library targeted nearly all Mtb genes, including protein-coding genes and non-coding RNAs. [17]

- Step 3: Transform the library into the target organism (e.g., Mtb H37Rv) and ensure adequate coverage (typically >500x per sgRNA). [17]

Screening Conditions and Drug Treatments

- Step 4: Grow the library to mid-log phase and split into multiple treatment conditions. Include vehicle-only controls for baseline fitness measurements.

- Step 5: Treat with selected drugs at concentrations spanning the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The published screen used 90 conditions across nine drugs at three partially inhibitory concentrations each. [17]

- Step 6: Culture for sufficient generations to allow fitness differences to emerge (typically 5-10 population doublings). [17]

Sample Processing and Sequencing

- Step 7: Harvest genomic DNA from all conditions at appropriate time points. The published study collected samples after library outgrowth under drug pressure. [17]

- Step 8: Amplify sgRNA regions with barcoded primers for multiplexed sequencing. Use sufficient sequencing depth to maintain representation of all library elements. [17]

Data Analysis and Hit Calling

- Step 9: Quantify sgRNA abundance by deep sequencing and analyze using specialized algorithms (e.g., MAGeCK). [17] Normalize counts to input library or vehicle control.

- Step 10: Identify hit genes whose knockdown significantly alters fitness during drug treatment (sensitizing or resistance-conferring). Apply appropriate statistical thresholds (e.g., FDR < 0.05). The Mtb study identified 1,373 sensitizing and 775 resistance genes. [17]

- Step 11: Validate top hits with individual hypomorphic strains in dose-response assays (IC50 determination). [17]

Chemical genetics represents a distinct and powerful approach within the broader chemical genomics landscape, characterized by its systematic measurement of gene-drug interactions. While chemical genomics encompasses diverse large-scale screening approaches, chemical genetics specifically focuses on how genetic variation modulates chemical sensitivity, providing unique insights into drug mechanisms, resistance pathways, and potential synergistic combinations. As technological advances in CRISPRi, barcoding, sequencing, and AI-driven analysis continue to enhance the resolution and scale of these approaches, chemical genetics is poised to remain an indispensable tool for functional genomics and targeted therapeutic development.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications: From Screening to Therapies

Chemical genomics, or chemogenomics, represents a powerful paradigm in modern drug discovery, focusing on the systematic screening of targeted chemical libraries or genetic modulators against families of drug targets to identify novel therapeutics and elucidate target functions [13]. This approach leverages the intersection of all possible bioactive compounds with all potential therapeutic targets, integrating target and drug discovery into a unified framework. High-throughput screening (HTS) platforms serve as the technological backbone of chemical genomics, enabling the rapid assessment of thousands of genetic perturbations or compound treatments. Within this context, the strategic selection between pooled and arrayed library formats becomes paramount, as each offers distinct advantages for specific phases of the target identification and validation pipeline [19] [13]. These screening methodologies empower researchers to bridge the gap between genomic information and functional understanding, ultimately accelerating the development of targeted therapeutics for various disease contexts.

Core Concepts: Pooled and Arrayed Screening Formats

Pooled Screening

Pooled screens involve introducing a mixture of guide RNAs (for CRISPR-based screens) or compounds into a single population of cells [19]. In this format, all perturbations occur within a single vessel, making it difficult to directly link individual cellular phenotypes to specific genetic perturbations without additional deconvolution steps. Pooled screens are therefore predominantly compatible with binary assays that enable physical separation of cells exhibiting a phenotype of interest from those that do not, such as viability selection or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [19] [20].

The typical workflow for a pooled CRISPR screen involves several key stages [19]:

- Library Construction: sgRNA-containing plasmids are packaged into lentiviral particles (one guide per vector) and combined to create a pooled library.

- Library Delivery: The pooled lentiviral library is transduced into host cells at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) to ensure single-guid integration.

- Selection: Selective pressure (e.g., drug treatment) is applied to enrich or deplete cells with specific phenotypes.

- Analysis: Next-generation sequencing (NGS) quantifies sgRNA abundance before and after selection to identify enriched or depleted guides, indicating genes involved in the phenotype [19].

Arrayed Screening

Arrayed screens involve testing one genetic perturbation or compound per well across multiwell plates [19] [21]. This physical separation of targets eliminates the need for complex deconvolution, as each well contains cells with a known, single perturbation. This format enables direct and immediate linkage between genotypes and phenotypes, making it suitable for complex, multiparametric assays [19] [20].

The arrayed screening workflow differs significantly from pooled approaches [19]:

- Library Construction: Arrayed libraries are prepared as individual reagents (e.g., plasmids, viruses, or synthetic sgRNAs) in multiwell plates.

- Library Delivery: Each well receives a single perturbation delivered via transfection, transduction, or as pre-complexed ribonucleoproteins (RNPs).

- Assaying: A selective pressure may be applied, but is optional. Phenotypes are directly measured using various assays.

- Analysis: Because each target is physically separated, phenotypic data can be directly correlated to specific genetic perturbations without sequencing [19] [21].

Comparative Analysis: Key Technical Considerations

The decision between pooled and arrayed screening formats involves multiple experimental considerations that significantly impact screening outcomes and resource allocation.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Pooled vs. Arrayed Screening Platforms

| Factor | Pooled Screening | Arrayed Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Assay Compatibility | Binary assays only (viability, FACS) [19] | Binary and multiparametric assays (morphology, high-content imaging) [19] [20] |

| Phenotype Complexity | Simple, selectable phenotypes [20] | Complex, multivariate phenotypes [22] [20] |

| Cell Model Requirements | Actively dividing cells; limited suitability for primary/non-dividing cells [19] [20] | Broad compatibility; suitable for primary, non-dividing, and delicate cells [19] [23] |

| Throughput & Scale | Ideal for genome-wide screens [21] [22] | Better for focused, targeted screens [21] [22] |

| Data Deconvolution | Requires NGS and bioinformatics [19] [20] | Direct genotype-phenotype linkage; no deconvolution needed [19] [21] |

| Equipment Needs | Standard lab equipment [19] | Automation, liquid handlers, high-content imaging systems [19] [20] |

| Experimental Timeline | Longer due to library prep and sequencing [19] | Potentially faster for focused screens; minimal post-assay analysis [21] |

| Cost Structure | Lower upfront cost [19] | Higher upfront cost [19] |

| Safety Considerations | Requires viral handling [20] | Can use synthetic guides (RNPs); avoids viral vectors [21] |

Advantages and Limitations in Practice

Pooled screens excel in scenarios requiring broad, exploratory investigation across thousands of targets, particularly when the desired phenotype can be linked to survival or easily measured via fluorescence [22]. Their cost-effectiveness for genome-scale interrogation makes them ideal for initial discovery phases in chemical genomics workflows [19] [21]. However, they face limitations with complex phenotypes, such as subtle morphological changes or extracellular secretion, which are difficult to deconvolve from a mixed population [21]. Additionally, the requirement for genomic integration of sgRNAs and extended cell expansion limits their use with non-dividing or primary cells [19] [20].

Arrayed screens offer superior versatility in assay design, enabling researchers to capture complex phenotypes through high-content imaging, multiparametric biochemical assays, and real-time kinetic measurements [22] [20]. The physical separation of perturbations eliminates confounding interactions between different cells in a population, which is particularly valuable when studying phenomena like inflammatory responses or senescence that can affect neighboring cells [21]. The primary constraint of arrayed screening remains scalability, as reagent and consumable costs increase substantially with library size, making them most suitable for targeted investigations or secondary validation [21] [22].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Detailed Protocol: Pooled CRISPR Screening

Stage 1: Library Construction and Validation

- Source Library: Obtain pooled sgRNA plasmid library as bacterial glycerol stock [19].

- Plasmid Amplification: Amplify library via PCR and validate guide representation through NGS to ensure equal distribution [19].

- Viral Production: Package sgRNA plasmids into lentiviral particles. Quality control includes titer determination via p24 assay, GFP expression, or antibiotic resistance [19] [23].

- Library Validation: Sequence final viral library to confirm guide integrity and representation before screening [19].

Stage 2: Library Delivery and Transduction

- Cell Preparation: Culture Cas9-expressing cells or co-transduce with Cas9-expressing virus [19].

- Transduction Optimization: Determine optimal MOI through pilot studies aiming for low MOI (typically ~0.3-0.5) to ensure most infected cells receive single integration events [19].

- Library Transduction: Transduce cell population with pooled viral library at predetermined MOI.

- Selection: Apply antibiotic selection (e.g., puromycin) 24-48 hours post-transduction to eliminate non-transduced cells. Maintain library coverage of 200-1000 cells per sgRNA throughout screening [19].

Stage 3: Phenotypic Selection

- Application of Selective Pressure: Apply relevant selective agent (e.g., drug for resistance/sensitivity screens) or sort cells based on fluorescence markers for complex phenotypes [19].

- Population Maintenance: Culture cells under selection for 10-21 population doublings to allow meaningful enrichment/depletion of guides [19].

- Sample Collection: Harvest genomic DNA from pre-selection and post-selection cell populations for sgRNA abundance quantification [19].

Stage 4: Analysis and Hit Identification

- Sequencing Library Prep: Amplify integrated sgRNA sequences from genomic DNA using PCR with barcoded primers for multiplexed sequencing [19].

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Sequence amplified libraries to determine sgRNA abundance in pre- and post-selection populations.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Align sequences to reference library, normalize counts, and employ statistical frameworks (e.g., MAGeCK, DESeq2) to identify significantly enriched or depleted sgRNAs [19].

- Hit Validation: Select candidate genes for confirmation in secondary screens using orthogonal approaches [21].

Detailed Protocol: Arrayed CRISPR Screening

Stage 1: Library Format Selection and Plate Preparation

- Reagent Selection: Choose between lentiviral, plasmid, or synthetic guide RNA formats based on cell type and transduction/transfection efficiency [23] [21].

- Plate Layout: Distribute individual sgRNAs or sgRNA pools (multiple guides per target gene) across 96- or 384-well plates, typically with 4 guides per gene to mitigate off-target effects [23] [21].

- Control Placement: Include appropriate controls (non-targeting guides, essential gene targeting, empty vector) distributed across plates to monitor assay performance and edge effects [23].

Stage 2: Cell Seeding and Reverse Transfection

- Cell Preparation: Harvest and count cells, ensuring high viability (>90%) for consistent plating.

- Reverse Transfection: For synthetic guides, complex sgRNA with Cas9 protein to form ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) directly in assay plates prior to cell addition [21].

- Cell Seeding: Dispense optimized cell number into each well containing pre-aliquoted guides or RNPs. For lentiviral delivery, add viral particles directly to cells [23].

- Incubation: Culture cells for sufficient duration to allow gene editing and phenotypic manifestation (typically 3-7 days) [20].

Stage 3: Assay Implementation and Phenotypic Readout

- Treatment Application: Add compounds, stimuli, or selective agents as required by experimental design [19].

- Multiparametric Detection: Implement assay endpoints compatible with high-content analysis:

- Data Acquisition: Utilize plate readers, high-content imagers, or automated microscopes configured for multiwell formats [20].

Stage 4: Data Analysis and Hit Confirmation

- Quality Control: Assess Z'-factor and other QC metrics using control wells to validate screen performance.

- Plate Normalization: Apply normalization algorithms to correct for positional and inter-plate variability.

- Hit Calling: Identify significant phenotypes using statistical thresholds (e.g., Z-score > 2 or <-2) relative to non-targeting controls.

- Hit Selection: Prioritize candidates based on effect size, consistency across replicates, and biological relevance for follow-up studies [21].

Strategic Implementation in Drug Discovery

Application in Chemical Genomics Workflows

Chemical genomics leverages both forward and reverse approaches to elucidate connections between small molecules, their protein targets, and phenotypic outcomes [13]. Within this framework, pooled and arrayed screening formats play complementary roles:

Forward chemogenomics begins with phenotype observation and aims to identify modulators and their molecular targets [13]. Arrayed screening is particularly valuable here, as it enables detection of complex phenotypic changes while immediately identifying the causal perturbation. For instance, discovering compounds that arrest tumor growth followed by target identification exemplifies this approach [13].

Reverse chemogenomics starts with specific protein targets and seeks to understand their biological function through targeted perturbation [13]. Pooled screening efficiently connects known targets to phenotypes under selective pressure, while arrayed formats allow detailed mechanistic follow-up on how target perturbation affects cellular pathways and processes [13].

Integrated Screening Strategies for Target Identification

Leading drug discovery programs often employ sequential screening strategies that leverage the complementary strengths of both formats [19] [21]:

- Primary Discovery Phase: Pooled CRISPR or compound screens interrogate thousands of targets under strong selective pressures (e.g., drug treatment) to generate candidate hit lists [19] [21].

- Secondary Validation Phase: Arrayed screens reconfirm primary hits using orthogonal assays and more complex phenotypic readouts in physiologically relevant models, including primary cells [19] [21].

- Mechanistic Elucidation: Focused arrayed screens with high-content endpoints delineate mechanisms of action and pathway relationships for validated hits [21] [20].

This tiered approach balances the comprehensive coverage of pooled screening with the precision and depth of arrayed validation, creating an efficient pipeline from initial discovery to mechanistic understanding.

Table 2: Decision Framework for Screening Format Selection

| Consideration | Guidance | Recommended Format |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Question | Genome-wide discovery vs. focused mechanistic study | Pooled for discovery; Arrayed for mechanistic [21] [20] |

| Phenotype Complexity | Simple survival vs. multiparametric morphology | Pooled for simple; Arrayed for complex [19] [22] |

| Cell Model | Immortalized vs. primary/non-dividing cells | Pooled for robust lines; Arrayed for delicate cells [19] [20] |

| Assay Duration | Short-term (days) vs. long-term (weeks) | Arrayed for short; Pooled for long [20] |

| Resource Availability | Limited vs. automated infrastructure | Pooled for minimal equipment; Arrayed for automated [19] [20] |

| Budget Constraints | Lower upfront vs. higher upfront costs | Pooled for budget-conscious; Arrayed for well-resourced [19] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of high-throughput screening platforms requires carefully selected reagents and tools optimized for each format.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for High-Throughput Screening

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Format Application |

|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral Vectors | Delivery of genetic perturbations through genomic integration | Primarily Pooled [19] [23] |

| Synthetic Guide RNAs | Chemically synthesized crRNAs or sgRNAs for transient expression | Primarily Arrayed (as RNPs) [21] |

| Cas9 Protein | RNA-guided endonuclease for CRISPR-mediated gene editing | Both (stable expression or protein) [23] [21] |

| Selection Antibiotics | Enrichment for successfully transduced cells (e.g., puromycin) | Both [19] [23] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Deconvolution of pooled screen results through sgRNA quantification | Primarily Pooled [19] |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Multiparametric analysis of complex phenotypes in situ | Primarily Arrayed [20] |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Precfficient reagent distribution across multiwell plates | Primarily Arrayed [20] |

| Viability Assay Reagents | Measure cell health and proliferation (ATP content, resazurin) | Both [23] |

| Barcoded sgRNA Libraries | Track individual perturbations in mixed populations | Primarily Pooled [19] |

| Ribonucleoprotein Complexes | Pre-formed Cas9-gRNA complexes for immediate activity | Primarily Arrayed [21] |

Pooled and arrayed screening formats represent complementary pillars of modern chemical genomics strategies, each offering distinct advantages for specific phases of drug discovery. Pooled screens provide cost-effective, genome-scale coverage for initial target identification under selective pressures, while arrayed screens enable deep mechanistic investigation of complex phenotypes through direct genotype-phenotype linkage. The most successful drug discovery pipelines strategically integrate both approaches, leveraging pooled screens for broad discovery and arrayed formats for validation and mechanistic elucidation. As chemical genomics continues to evolve with advances in single-cell technologies, CRISPR enhancements, and artificial intelligence, the synergistic application of both screening paradigms will remain essential for accelerating the identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets across diverse disease areas.

Elucidating Mechanism of Action (MoA) via Haploinsufficiency and Overexpression Profiling

Chemical genomic approaches, which systematically measure the cellular outcome of combining genetic and chemical perturbations, have emerged as a powerful toolkit for drug discovery [14]. These approaches can delineate the cellular function of a drug, revealing its targets and its path in and out of the cell [14]. By assessing the contribution of every gene to an organism's fitness upon drug exposure, chemical genetics provides insights into drug mechanisms of action (MoA), resistance pathways, and drug-drug interactions [14]. Two primary vignettes of this approach are Haploinsufficiency Profiling (HIP) and Homozygous Profiling (HOP), which, along with overexpression screens, are foundational for identifying drug targets and understanding compound MoA [24] [14]. This technical guide details the methodologies, data analysis, and practical implementation of these profiles, framing them within the broader context of accelerating therapeutic development.

Core Concepts: HIP, HOP, and Overexpression Profiling

Haploinsufficiency Profiling (HIP)

HIP assays utilize a set of heterozygous deletion diploid strains grown in the presence of a compound [24]. Reducing the gene dosage of a drug target from two copies to one can result in increased drug sensitivity, a phenomenon known as drug-induced haploinsufficiency [24]. Under normal conditions, one gene copy is typically sufficient for normal growth in diploid yeast. However, when a drug targets the protein product of a specific gene, reducing that protein's cellular concentration by half can render the cell more susceptible to the drug's effects [24]. Consequently, HIP experiments are designed to identify direct relationships between gene haploinsufficiency and compounds, often pointing to the direct cellular target of the compound [14].

Homozygous Profiling (HOP) and Overexpression Profiling

In contrast to HIP, HOP assays measure drug sensitivities of strains with complete deletion of non-essential genes in either haploid or diploid strains [24]. Because of the complete gene deletion, HOP assays are more likely to identify genes that buffer the drug target pathway or are part of parallel, compensatory pathways, rather than the direct target itself [24].

A complementary approach to HIP is overexpression profiling. This method involves systematically increasing gene levels, often through engineered gain-of-function mutations or plasmid-based overexpression [14]. If a gene is the direct target of a compound, its overexpression can make the cell more resistant to the drug, as a higher concentration of the compound is required to inhibit the increased number of target proteins [14]. Overexpression is particularly technically straightforward in haploid organisms like bacteria [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Chemical Genomic Profiling Approaches

| Profile Type | Genetic Perturbation | Primary Application | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIP (Haploinsufficiency) | Heterozygous deletion (50% gene dosage) | Identify direct drug targets | Increased sensitivity indicates potential direct target |

| HOP (Homozygous) | Complete deletion of non-essential genes | Identify pathway buffers & compensatory genes | Increased sensitivity indicates genes buffering the target pathway |

| Overexpression | Increased gene dosage (GOF/overexpression) | Confirm direct drug targets & resistance mechanisms | Increased resistance indicates potential direct target |

Quantitative Foundations and Data Analysis

The Fitness Defect Score (FD-score)

The fitness defect score (FD-score) is a fundamental metric used to predict drug targets by comparing perturbed growth rates to control strains [24]. For a gene deletion strain i and compound c, the FD-score is defined as: [ \text{FD}{ic} = \log \frac{r{ic}}{\bar{ri}} ] where ( r{ic} ) is the growth defect of deletion strain i in the presence of compound c, and ( \bar{r_i} ) is the average growth defect of deletion strain i measured under multiple control conditions without any compound treatment [24]. A low, negative FD-score indicates a putative interaction between the deleted gene and the compound, signifying that the strain is more sensitive to the drug [24].

Advanced Network-Assisted Scoring: The GIT Method

The GIT (Genetic Interaction Network-Assisted Target Identification) method represents a significant advancement over simple FD-score ranking by incorporating the fitness defects of a gene's neighbors in the genetic interaction network [24]. This network is constructed from Synthetic Genetic Array (SGA) data, with edge weights representing the strength and sign (positive or negative) of genetic interactions [24].

For HIP assays, the GITHIP-score is calculated as: [ \text{GIT}{ic}^{HIP} = \text{FD}{ic} - \sumj \text{FD}{jc} \cdot g{ij} ] where ( g{ij} ) is the genetic interaction edge weight between gene i and its neighbor gene j [24]. This scoring system leverages the intuition that if a gene is a drug target, its negative genetic interaction neighbors (which often have similar functions) will also show sensitivity (negative FD-scores), while its positive genetic interaction neighbors may show resistance (positive FD-scores) [24]. This integration of network information substantially improves the signal-to-noise ratio for target identification [24].

For HOP assays, GIT incorporates the FD-scores of long-range "two-hop" neighbors to better identify genes that buffer the drug target pathway, acknowledging the inherent biological differences between HIP and HOP assays [24].

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for MoA Elucidation

| Metric | Formula | Application | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FD-score | ( \text{FD}{ic} = \log \frac{r{ic}}{\bar{r_i}} ) [24] | HIP, HOP, & Overexpression | Negative value indicates increased drug sensitivity |

| GITHIP-score | ( \text{GIT}{ic}^{HIP} = \text{FD}{ic} - \sumj \text{FD}{jc} \cdot g_{ij} ) [24] | HIP-specific target ID | Low score indicates potential compound-target interaction |

| Genetic Interaction (gij) | ( g{ij} = f{ij} - fi fj ) [24] | Network construction | Negative: synthetic sickness/lethality; Positive: alleviating interaction |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Workflow for HIP-HOP Profiling in Yeast

Detailed Methodological Steps

Library Construction and Cultivation: Utilize a genome-wide mutant library. For HIP assays in yeast, this is an arrayed or pooled collection of heterozygous diploid strains. For HOP assays, use a library of homozygous deletant strains for non-essential genes [14]. Culture the library in appropriate media to mid-log phase.

Compound Treatment and Control: Split the culture and expose it to the compound of interest at a predetermined concentration (often sub-lethal) and to a no-drug control condition. For arrayed formats, this is typically performed in multi-well plates; for pooled formats, the entire library is grown competitively in a single flask [14].

Growth Fitness Measurement:

- Arrayed Libraries: Use high-throughput automated microscopy or plate readers to quantify growth (e.g., optical density, colony size) over time [14].

- Pooled Libraries: Employ barcode sequencing (Bar-seq) [14]. Extract genomic DNA from the population before and after treatment. Amplify the unique molecular barcodes for each strain and sequence them using high-throughput platforms. The relative abundance of each barcode is a proxy for strain fitness [14].

Data Processing and Analysis: Calculate the FD-score for each strain as defined in Section 3.1. For improved target identification, apply the GIT scoring method, which requires a pre-computed genetic interaction network [24].

Signature Comparison for MoA: Compare the resulting fitness profile (the "signature") of the compound to a database of profiles from compounds with known MoA. Drugs with similar signatures are likely to share cellular targets and/or cytotoxicity mechanisms, a "guilt-by-association" approach [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HIP/HOP Profiling

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Wide Deletion Library | Arrayed or pooled collection of gene deletion mutants. | Foundation for all profiling screens; available for yeast, bacteria, and human cell lines [14]. |

| CRISPRi/a Libraries | Pooled libraries for knockdown (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) of essential genes. | Enables HIP-like screens in haploid organisms and human cells [14]. |

| Barcoded Mutant Libraries | Libraries where each strain has a unique DNA barcode. | Enables highly parallel fitness quantification via sequencing in pooled competitive growth assays [14]. |

| Genetic Interaction Network | A signed, weighted network of genetic interactions (e.g., from SGA). | Crucial for advanced network-assisted scoring methods like GIT [24]. |

| AntagoNATs | Oligonucleotide-based compounds targeting natural antisense transcripts (NATs). | Can be used to upregulate haploinsufficient genes for functional validation and therapeutic exploration [25]. |

Signaling Pathways Elucidated by Profiling

Chemical-genetic profiling often reveals involvement of core cellular signaling pathways. A prominent example is the mTOR pathway, which has been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders through haploinsufficiency of genes like PLPPR4.