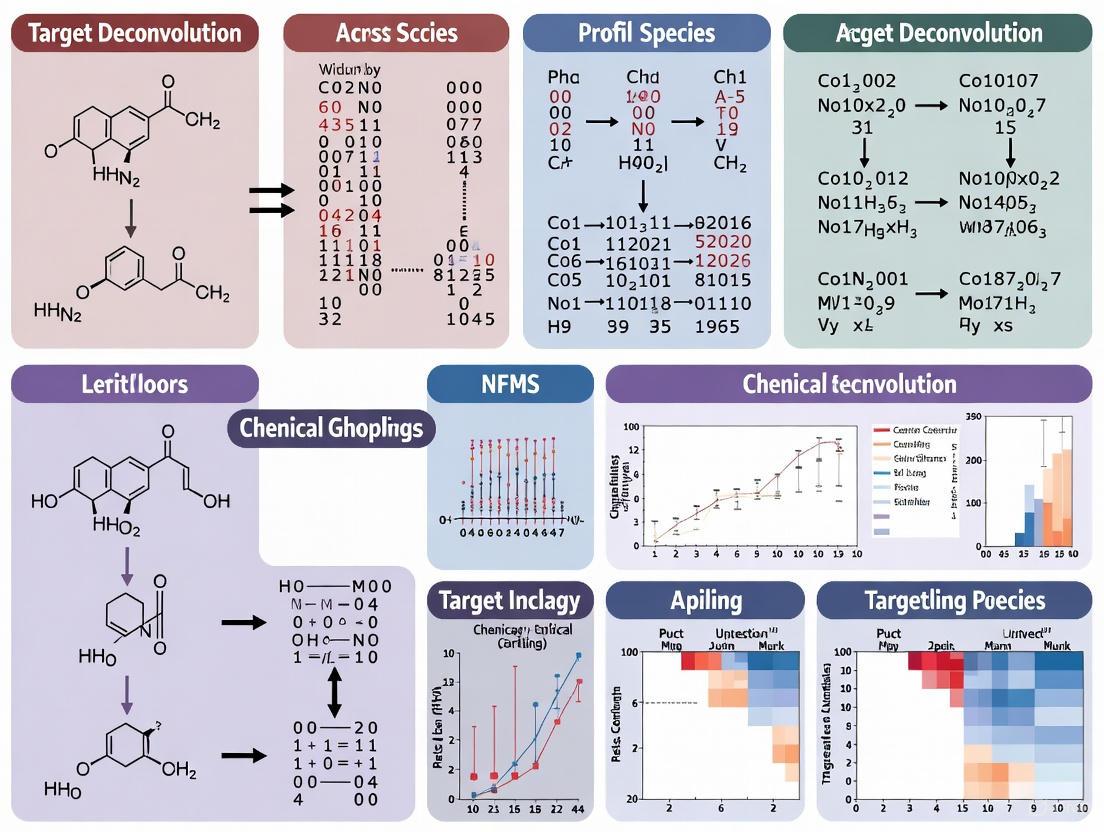

Chemical Genomic Profiling for Target Deconvolution: Cross-Species Strategies and Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemical genomic profiling as a powerful, unbiased approach for target deconvolution in phenotypic drug discovery.

Chemical Genomic Profiling for Target Deconvolution: Cross-Species Strategies and Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemical genomic profiling as a powerful, unbiased approach for target deconvolution in phenotypic drug discovery. It explores foundational principles, diverse methodological platforms from yeast to mycobacteria, and computational tools for data analysis. The content addresses critical troubleshooting for batch effects and quality control, alongside validation strategies through case studies in tuberculosis and cancer research. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes how integrating cross-species chemical-genetic interaction data accelerates mechanism of action elucidation and hit prioritization, ultimately streamlining the therapeutic development pipeline.

Principles and Power of Phenotypic Screening and Target Deconvolution

The Renaissance of Phenotypic Screening in Modern Drug Discovery

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) has experienced a major resurgence over the past decade, re-establishing itself as a powerful modality for identifying first-in-class medicines after a period dominated by target-based approaches [1] [2]. This renaissance follows the surprising observation that between 1999 and 2008, a majority of first-in-class drugs were discovered empirically without a predefined target hypothesis [1]. Modern PDD combines the original concept of observing therapeutic effects in whole biological systems with contemporary tools and strategies, including high-content imaging, functional genomics, and artificial intelligence [2]. This whitepaper examines the principles, successes, methodologies, and future directions of phenotypic screening within the context of chemical genomic profiling for target deconvolution research.

The Resurgence and Impact of Phenotypic Screening

Historical Context and Modern Revival

The shift from traditional phenotype-based discovery to target-based drug discovery (TDD) was driven by the molecular biology revolution and human genome sequencing [1]. However, an analysis of drug discovery outcomes revealed that phenotypic strategies were disproportionately successful in generating first-in-class medicines [2]. Between 2000 and 2008, of the 50 first-in-class small molecule drugs discovered, 28 originated from phenotypic strategies compared to 17 from target-based approaches [2]. This evidence triggered a renewed investment in PDD, though with modern enhancements that distinguish it from historical approaches [2].

Key Advantages and Strategic Applications

Modern PDD offers several distinct advantages. By testing compounds in disease-relevant biological systems rather than on isolated molecular targets, PDD more accurately models complex disease physiology and potentially offers better translation to clinical outcomes [2]. This approach is particularly valuable when:

- No attractive molecular target is known to modulate the pathway or disease phenotype of interest

- The project goal is to obtain a first-in-class drug with a differentiated mechanism of action

- Investigating complex, polygenic diseases with multiple underlying mechanisms [1]

Phenotypic screening also serves as a valuable complement to TDD by feeding novel targets and mechanisms into the pipeline [2].

Notable Successes from Phenotypic Approaches

Recent Drug Discoveries

Phenotypic screening has generated several notable therapeutics in the past decade, often revealing novel mechanisms of action and expanding druggable target space [1]. The table below summarizes key successes:

Table 1: Notable Drugs Discovered Through Phenotypic Screening

| Drug/Compound | Disease Area | Key Target/Mechanism | Discovery Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ivacaftor, Lumicaftor, Tezacaftor, Elexacaftor | Cystic Fibrosis | CFTR channel gating and folding correction | Cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants [1] |

| Risdiplam, Branaplam | Spinal Muscular Atrophy | SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing modulation | Phenotypic screens identifying small molecules that modulate SMN2 splicing [1] |

| SEP-363856 | Schizophrenia | Unknown novel target (serendipitous discovery) | In vivo disease models [1] |

| Lenalidomide | Multiple Myeloma | Cereblon E3 ligase modulation (degrading IKZF1/IKZF3) | Observations of thalidomide efficacy in multiple diseases [1] |

| Daclatasvir | Hepatitis C | NS5A protein inhibition | HCV replicon phenotypic screen [1] |

Expansion of Druggable Target Space

PDD has significantly expanded what is considered "druggable" by revealing unexpected cellular processes and novel target classes [1]. These include:

- Novel Mechanisms: Pre-mRNA splicing, target protein folding, trafficking, and degradation

- New Target Classes: Bromodomains, pseudo-kinase domains, and multi-component "cellular machines"

- Unconventional Target Classes: NS5A (HCV protein without known enzymatic activity) and molecular glues like lenalidomide [1]

This expansion demonstrates how phenotypic strategies can reveal biology that would be difficult to predict through hypothesis-driven target-based approaches.

Methodological Framework for Phenotypic Screening

Experimental Design and Workflow

Modern phenotypic screening employs sophisticated workflows that integrate biology, technology, and informatics. The diagram below illustrates a comprehensive phenotypic screening and target deconvolution workflow:

Critical Success Factors in Assay Design

Robust assay development forms the foundation of reliable phenotypic screening [3]. Key considerations include:

- Biologically Relevant Cell Models: Use disease-relevant cells, preferably primary cells or patient-derived samples, compatible with high-throughput formats [3] [2]

- Assay Optimization: Adjust seeding density for accurate single-cell segmentation and optimize incubation conditions to reduce plate effects [3]

- Image Acquisition Parameters: Set appropriate exposure time, correct autofocus offset, and capture sufficient images per well to adequately represent the cell population [3]

Pfizer's cystic fibrosis program exemplifies successful implementation, where using bronchial epithelial cells from CF patients enabled identification of compounds that re-established the thin film of liquid crucial for proper lung function [2].

Best Practices During Screening Execution

Careful execution is essential to generate high-quality phenotypic data [3]:

- Automation: Automate dispensing and imaging steps to reduce human error while maintaining expert oversight

- Consistency: Keep plates, reagents, and cell batches consistent to minimize batch effects

- Controls: Include positive and negative controls on every plate to monitor assay performance

- Replication: Include sufficient replicates across conditions to support robust downstream modeling

- Anchor Compounds: Include shared "anchor" samples across batches to enable robust batch correction

Advanced Technologies Enhancing Phenotypic Screening

High-Content Profiling Methodologies

Modern phenotypic screening leverages several high-content profiling technologies that provide complementary information:

Table 2: High-Content Profiling Technologies for Phenotypic Screening

| Technology | Key Features | Applications | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting | Multiplexed imaging of 6-8 cellular components | Morphological profiling, MoA classification, hit identification | High (can profile >100,000 compounds) [4] |

| L1000 Assay | Gene expression profiling of ~1,000 landmark genes | Transcriptional profiling, MoA prediction | High (can profile >100,000 compounds) [4] |

| High-Content Imaging | Automated microscopy with multiple channels | Multiparametric analysis of cellular phenotypes | Medium to High [3] |

AI and Machine Learning Integration

Artificial intelligence dramatically enhances phenotypic screening by extracting biologically meaningful patterns from high-dimensional data [3] [4]. Key applications include:

- Morphological Profiling: Platforms like Ardigen's phenAID leverage computer vision and deep learning to extract high-dimensional features from high-content screening images [3]

- Assay Prediction: Integrating chemical structures with phenotypic profiles (morphological and gene expression) can predict compound bioactivity for 64% of assays, compared to 37% using chemical structures alone [4]

- Hit Identification: AI models can identify high-quality hits and perform image-based virtual screening [3]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | Patient-derived primary cells, iPSCs, Biologically relevant cell lines | Recreating disease physiology in microplates [3] [2] |

| Detection Reagents | Cell Painting dyes (MitoTracker, Concanavalin A, Phalloidin, etc.) | Multiplexed staining of cellular components [3] |

| Compound Libraries | Annotated compounds with known mechanisms | Training AI models for MoA prediction [3] |

| Photo-affinity Probes | Benzophenones, aryl azides, diazirines | Covalent cross-linking for target identification [5] |

| L1000 Profiling Reagents | L1000 landmark gene set | Gene expression profiling at scale [4] |

Target Deconvolution Strategies

Methodological Approaches

Target deconvolution remains a critical challenge in PDD, but several powerful approaches have emerged:

Photo-affinity Labeling (PAL) for Target Identification

Photo-affinity labeling enables direct identification of molecular targets by incorporating photoreactive groups into small molecule probes [5]. Under specific wavelengths of light, these probes form irreversible covalent linkages with neighboring target proteins, capturing transient molecular interactions [5]. Key components of PAL probes include:

- Photo-reactive Groups: Benzophenones, aryl azides, and diazirines that generate reactive intermediates upon photoactivation

- Click Chemistry Handles: Alkyne or azide groups enabling biotin/fluorescein conjugation for target enrichment

- Spacer/Linker Groups: Optimized length and composition to minimize steric hindrance [5]

Compared to methods like CETSA and DARTS, PAL provides direct evidence of physical binding between small molecules and targets, making it highly suitable for unbiased target discovery [5].

Knowledge Graph Approaches

Knowledge graphs have emerged as powerful tools for target deconvolution, particularly for complex pathways like p53 signaling [6]. The workflow involves:

- Graph Construction: Building a protein-protein interaction knowledge graph (PPIKG) incorporating known biological relationships

- Candidate Prioritization: Using the knowledge graph to narrow candidate targets from thousands to dozens

- Molecular Docking: Virtual screening of compounds against prioritized targets

- Experimental Validation: Biological confirmation of predicted targets [6]

In one application, this approach narrowed candidate proteins from 1,088 to 35 and identified USP7 as a direct target for the p53 pathway activator UNBS5162 [6].

Emerging Trends

The future of phenotypic screening will be shaped by several converging technologies:

- AI Integration: Deeper integration of machine learning across the entire workflow, from assay design to target deconvolution [7] [3] [4]

- Multi-modal Data Fusion: Combining chemical structures with morphological and gene expression profiles to enhance prediction accuracy [4]

- Improved Disease Models: Development of more physiologically relevant models, including patient-derived organoids and complex co-culture systems [2]

- Functional Genomics: CRISPR screening combined with phenotypic readouts to identify novel targets and mechanisms [1]

Phenotypic drug discovery has firmly re-established itself as a powerful approach for identifying first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms of action. By combining biologically relevant systems with modern technologies—including high-content imaging, chemical genomics, artificial intelligence, and advanced target deconvolution methods—PDD continues to expand the druggable genome and deliver transformative therapies. For researchers pursuing innovative therapeutics, particularly for complex diseases with poorly understood pathophysiology, phenotypic screening offers a compelling path forward that complements target-based approaches and enhances the overall drug discovery portfolio.

Target deconvolution represents a critical, interdisciplinary frontier in modern phenotypic drug discovery and chemical genomics. This process systematically identifies the molecular targets of bioactive small molecules discovered through phenotypic screening, thereby bridging the gap between observed biological effects and their underlying mechanistic causes. As drug discovery witnesses a renaissance in phenotype-based approaches, advanced chemoproteomic strategies have emerged to address the central challenge of target identification. This technical guide comprehensively outlines the core principles, methodological frameworks, and experimental applications of target deconvolution, with particular emphasis on its role in elucidating conserved biological pathways across species through chemical genomic profiling.

Phenotypic screening provides an unbiased approach to discovering biologically active compounds within complex biological systems, offering significant advantages in identifying novel therapeutic mechanisms. According to recent analyses of new molecular entities, target-based approaches prove less efficient than phenotypic methods for generating first-in-class small-molecule drugs [8]. Phenotypic screening operates within a physiologically relevant environment of cells or whole organisms, delivering a more direct view of desired responses while simultaneously highlighting potential side effects [8]. This approach can identify multiple proteins or pathways not previously linked to a specific biological output, making the subsequent process of identifying molecular targets of active hits—target deconvolution—essential for understanding compound mechanism of action (MoA) [8] [9].

The fundamental challenge of target deconvolution lies in its "needle in a haystack" nature—identifying specific protein interactions among thousands of potential candidates within complex proteomes [10]. This process forms the critical link between phenotypic chemical screening and comprehensive exploration of underlying mechanisms, enabling researchers to confirm a compound's MoA, minimize off-target effects, and ensure therapeutic relevance [11]. Within chemical genomic profiling across species, target deconvolution takes on additional significance, allowing researchers to trace conserved biological pathways and identify functionally homologous targets through cross-species comparative analysis.

Core Principles and Methodological Frameworks

Defining Target Deconvolution in Chemical Genomics

Target deconvolution refers to the process of identifying the molecular target or targets of a particular chemical compound in a biological context [9]. As a vital project of forward chemical genetic research, it aims to identify the molecular targets of an active hit compound, serving as the essential connection between phenotypic screening and subsequent compound optimization and mechanistic interrogation [10] [9]. The term "deconvolution" accurately reflects the process of unraveling complex phenotypic responses to identify the spectrum of potential molecular targets responsible for observed effects [8].

In the broader context of chemical genetics, target deconvolution plays a fundamentally different role in forward versus reverse approaches. Forward chemical genetics initiates with chemical screening in living biological systems to observe phenotypic responses, then employs target deconvolution to identify molecular targets and MoA [10]. Conversely, reverse chemical genetics begins with specific genes or proteins of interest and seeks functional modulators [10]. This distinction positions target deconvolution as a crucial enabling technology for phenotypic discovery programs, particularly in cross-species chemical genomic studies where conserved target relationships can reveal fundamental biological mechanisms.

Key Technical Approaches and Their Applications

Modern target deconvolution employs diverse methodological approaches, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and optimal application contexts. The table below summarizes the major technical categories and their characteristics:

Table 1: Major Target Deconvolution Approaches and Their Characteristics

| Method Category | Key Examples | Principles | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity-Based Chemoproteomics | Affinity chromatography, Immobilized compound beads | Compound immobilization on solid support to isolate bound targets from complex proteomes [8] [9] | Works for wide target classes; provides dose-response information [9] | Requires high-affinity probes; immobilization may affect activity [8] |

| Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) | Activity-based probes with reactive groups | Covalent modification of enzyme active sites using probes with reactive electrophiles [8] | Targets specific enzyme classes; powerful for mechanism study [8] | Requires active site nucleophile; limited to enzyme families [8] |

| Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) | Photoaffinity probes with photoreactive groups | Photoreactive groups generate reactive intermediates under light to form covalent bonds with targets [5] | Captures transient interactions; suitable for membrane proteins [5] [9] | Requires substantial SAR knowledge; potential activity loss [5] |

| Label-Free Methods | CETSA, DARTS, PISA | Detects ligand-induced changes in protein stability or protease susceptibility [11] [12] | No compound modification needed; native conditions [9] | Challenging for low-abundance proteins [9] |

| Computational & Knowledge-Based | PPIKG, Molecular docking | Integrates biological networks and structural prediction [6] | Rapid screening; cost-effective; hypothesis generation [6] | May miss novel targets; limited by database completeness [6] |

Diagram 1: Target Deconvolution Workflow and Method Selection. This diagram illustrates the sequential process from phenotypic screening to mechanism elucidation, highlighting the major methodological approaches and their primary applications in target deconvolution.

Experimental Platforms and Research Reagents

The successful implementation of target deconvolution strategies relies on specialized experimental platforms and research reagents designed to capture and identify compound-protein interactions. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for implementing target deconvolution protocols:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Target Deconvolution

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | Affinity beads, ABPs, PAL probes | Enable target engagement and enrichment for MS identification [8] [10] | Require structure-activity relationship knowledge; potential activity loss [8] |

| Photo-reactive Groups | Benzophenones, aryl azides, diazirines | Generate reactive intermediates under UV light for covalent cross-linking [5] | Vary in reactivity, selectivity, and biocompatibility [5] |

| Click Chemistry Handles | Alkyne, azide tags | Enable bioorthogonal conjugation for reporter attachment after target binding [8] | Minimize structural perturbation; copper-free variants available [8] |

| Affinity Matrices | Magnetic beads, solid supports | Immobilize bait compounds for pull-down assays [8] [9] | Bead composition affects non-specific binding and efficiency [8] |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | LC-MS/MS systems | Identify and sequence enriched proteins with high sensitivity [8] [10] | Critical for low-abundance target detection; requires proteomic expertise [10] |

| Stability Assay Reagents | CETSA, DARTS components | Detect ligand-induced protein stabilization [11] [12] | Enable label-free detection in native conditions [9] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Affinity Chromatography and Pull-Down Assays

Affinity purification represents the most widely used technique to isolate specific target proteins from complex proteomes [8]. The standard protocol involves multiple critical stages:

Probe Design and Immobilization: Modify the active compound with appropriate linkers (e.g., azide or alkyne tags) to minimize structural perturbation [8]. Conjugate to solid support (e.g., magnetic beads) via click chemistry or direct coupling [8]. Critical consideration: Any modification of active molecules may affect binding affinity, requiring substantial structure-activity relationship knowledge [8].

Incubation and Binding: Expose immobilized bait to cell lysate or living systems under physiologically relevant conditions. Extensive washing removes non-specific binders while retaining true interactors [8].

Target Elution and Identification: Specifically elute bound proteins using competitive ligands, pH shift, or denaturing conditions. Separate eluted proteins via gel electrophoresis or direct "shotgun" sequencing with multidimensional liquid chromatography [8].

Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Digest proteins with trypsin, analyze peptide fragments via LC-MS/MS, and identify sequences through database searching [8].

Diagram 2: Affinity Chromatography Workflow. This diagram outlines the sequential steps in affinity-based target deconvolution, from compound modification through target validation.

Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) Methodology

Photoaffinity labeling enables the incorporation of photoreactive groups into small molecule probes that form irreversible covalent linkages with neighboring target proteins upon specific wavelength light exposure [5]. The standardized PAL protocol includes:

Probe Design and Synthesis: Construct trifunctional probes containing: (a) the small molecule compound of interest, (b) a photoreactive moiety (benzophenone, diazirine, or aryl azide), and (c) an enrichment handle (biotin, alkyne) [5] [9]. Strategic placement of photoreactive groups minimizes interference with target binding.

Cellular Treatment and Photo-Crosslinking: Incubate probes with living cells or cell lysates to allow target engagement. Apply UV irradiation (specific wavelength depends on photoreactive group) to initiate covalent bond formation between probe and target proteins [5].

Target Capture and Enrichment: Utilize click chemistry to conjugate biotin or other affinity tags if not pre-incorporated. Capture labeled proteins using streptavidin beads or appropriate affinity matrices [5].

Protein Identification and Validation: Process enriched proteins for LC-MS/MS analysis. Validate identified targets through orthogonal approaches such as CETSA, genetic knockdown, or functional assays [5].

This approach provides irrefutable evidence of direct physical binding between small molecules and targets, making it highly suitable for unbiased, high-throughput target discovery [5]. Unlike ABPP, which primarily targets enzymes with covalent modification sites, PAL applies to almost all protein types [5].

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) Procedures

Activity-based protein profiling uses specialized chemical probes to monitor the activity of specific enzyme classes in complex proteomes [8]. The ABPP workflow consists of:

Probe Design: Construct activity-based probes containing three components: (a) a reactive electrophile for covalent modification of enzyme active sites, (b) a linker or specificity group directing probes to specific enzymes, and (c) a reporter or tag for separating labeled enzymes [8].

Labeling Reaction: Incubate ABPs with cells or protein lysates to allow specific covalent modification of active enzymes. Include control samples without probe for background subtraction [8].

Conjugation and Enrichment: Employ copper-catalyzed or copper-free click chemistry to attach affinity tags if not pre-incorporated. Enrich labeled proteins using appropriate affinity purification [8].

Identification and Analysis: Identify enriched proteins via LC-MS/MS. Compare labeling patterns between treatment conditions to identify specific targets [8].

ABPP is particularly powerful for phenotypic screening and lead optimization when specific enzyme families are implicated in disease states or pathways [8]. Recent advances incorporate photo-reactive groups to extend ABPP to enzyme classes lacking nucleophilic active sites [8].

Applications in Chemical Genomic Profiling Across Species

Target deconvolution plays a particularly valuable role in cross-species chemical genomic studies, where it enables the identification of evolutionarily conserved targets and pathways. The application of knowledge graphs and computational integration has demonstrated particular promise in this domain. For example, researchers constructed a protein-protein interaction knowledge graph (PPIKG) to narrow candidate proteins from 1088 to 35 for a p53 pathway activator, significantly saving time and cost while enabling target identification through subsequent molecular docking [6].

In cross-species contexts, phenotypic screening in model organisms followed by target deconvolution can reveal conserved biological mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets relevant to human disease. The identification of cereblon as the molecular target of thalidomide exemplifies how target deconvolution explains species-specific effects and reveals conserved biological pathways [8]. Such approaches are particularly powerful when combined with chemoproteomic methods that function across diverse organisms, enabling researchers to trace the evolutionary conservation of drug targets and mechanisms.

Target deconvolution stands as an essential discipline bridging phenotypic observations with molecular mechanisms in modern drug discovery and chemical biology. As technological advances continue to enhance the sensitivity, throughput, and accessibility of chemoproteomic methods, target deconvolution will play an increasingly central role in elucidating the mechanisms of bioactive compounds, particularly in cross-species chemical genomic profiling. The integration of multiple complementary approaches—affinity-based methods, activity-based profiling, photoaffinity labeling, and computational prediction—provides a powerful toolkit for researchers seeking to understand the precise molecular interactions underlying phenotypic changes. This multidisciplinary framework will continue to drive innovation in both basic research and therapeutic development, ultimately enhancing our ability to translate chemical perturbations into mechanistic understanding across biological systems.

Chemical-Genetic Interactions and Fitness Profiling

Core Concepts and Definitions

Chemical-genetic interactions (CGIs) represent a powerful functional genomics approach that quantitatively measures how genetic perturbations alter a cell's response to chemical compounds. When a specific gene mutation confers unexpected sensitivity or resistance to a compound, it reveals a functional relationship between the chemical and the deleted gene product. This interaction provides direct insight into the compound's mechanism of action within the cell [13].

A chemical-genetic interaction profile is generated by systematically challenging an array of mutant strains with a compound and monitoring for fitness defects. This profile offers an unbiased, quantitative description of the cellular functions perturbed by the compound. Negative chemical-genetic interactions occur when a gene deletion increases a cell's sensitivity to a compound, while positive interactions occur when a deletion confers resistance [13]. These profiles contain rich functional information linking compounds to their cellular modes of action.

Fitness profiling refers to the comprehensive assessment of how genetic variations affect cellular growth and survival under different conditions, including chemical treatment. The integration of chemical-genetic interaction data with genetic interaction networks—obtained from genome-wide double-mutant screens—provides a key framework for interpreting this functional information [13]. This integration enables researchers to predict the biological processes perturbed by compounds, bridging the gap between chemical treatment and cellular response.

Experimental Methodologies

Core Screening Protocol

The standard methodology for chemical-genetic interaction screening involves systematic testing of compound libraries against comprehensive mutant collections. The following protocol outlines the essential steps for conducting such screens in model organisms like Saccharomyces cerevisiae:

Strain Preparation: Utilize a complete deletion mutant collection where each non-essential gene is replaced with a molecular barcode. Grow cultures to mid-log phase in appropriate medium [13] [14].

Compound Treatment: Prepare compound plates using serial dilution to achieve desired concentration range. Include negative controls (DMSO only) on each plate [14].

Pooled Screening: Combine all mutant strains in a single pool. Expose the pooled mutants to each test compound across multiple concentrations. Typically, use 2-3 biological replicates per condition [13].

Growth Measurement: Incubate cultures for approximately 15-20 generations to allow fitness differences to manifest. Monitor growth kinetically or measure final cell density [13].

Barcode Amplification and Sequencing: Harvest cells after competitive growth. Extract genomic DNA and amplify unique molecular barcodes using PCR. Sequence amplified barcodes to quantify strain abundance [14].

Fitness Calculation: Compare barcode abundance between treatment and control conditions to calculate relative fitness scores for each mutant. Normalize data to account for technical variations [13].

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters for Chemical-Genetic Screening

| Parameter | Typical Range | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Concentration | 0.5-50 µM | Include sub-inhibitory concentrations to detect subtle interactions [15] |

| Screening Replicates | 2-4 biological replicates | Essential for statistical power and reproducibility |

| Culture Duration | 15-20 generations | Sufficient for fitness differences to emerge |

| Mutant Library Size | ~5,000 non-essential genes | Comprehensive coverage of deletable genome |

| Control Inclusion | DMSO vehicle, untreated | Normalization and quality control |

Data Processing and Quality Control

Raw sequencing data requires substantial processing to generate reliable fitness profiles. The quality control pipeline includes:

- Sequence Alignment: Map barcode sequences to reference strain library using exact matching.

- Abundance Normalization: Apply quantile normalization across samples to minimize technical bias.

- Fitness Calculation: Compute relative fitness as log₂ ratio of normalized barcode counts between treatment and control.

- Significance Thresholding: Establish significance thresholds using negative control distributions (typically |score| > 2 and p < 0.05) [13].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The CG-TARGET Analytical Framework

The CG-TARGET (Chemical Genetic Translation via A Reference Genetic nETwork) method provides a robust computational framework for interpreting chemical-genetic interaction profiles. This approach integrates large-scale chemical-genetic interaction data with a reference genetic interaction network to predict the biological processes perturbed by compounds [13].

The methodology operates through several key steps:

Profile Comparison: Each compound's chemical-genetic interaction profile is systematically compared to reference genetic interaction profiles using statistical similarity measures.

Similarity Scoring: Compute similarity scores between chemical-genetic profiles and reference genetic interaction profiles using Pearson correlation or rank-based methods.

False Discovery Control: Implement rigorous false discovery rate (FDR) control to generate high-confidence biological process predictions, a key advantage over simpler enrichment-based approaches [13].

Process Annotation: Assign biological process predictions based on the highest similarity scores that pass FDR thresholds.

CG-TARGET has been successfully applied to large-scale screens of nearly 14,000 chemical compounds in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, enabling high-confidence biological process predictions for over 1,500 compounds [13].

Machine Learning Approaches

Beyond similarity-based methods, machine learning algorithms have demonstrated significant utility in predicting compound synergism from chemical-genetic interaction data. Random Forest and Naive Bayesian learners can associate chemical structural features with genotype-specific growth inhibition patterns to predict synergistic combinations [14].

Key developments in this area include:

- Feature Engineering: Molecular descriptors and chemical-genetic interaction profiles serve as input features.

- Model Training: Using experimentally determined synergistic pairs as training data.

- Species-Selective Prediction: Models can identify combinations with selective toxicity against pathogenic fungi while sparing host cells [14].

Table 2: Genetic Interaction Types and Their Interpretations

| Interaction Type | Definition | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Chemical-Genetic | Mutation increases sensitivity to compound | Gene product may be target of compound or in compensatory pathway |

| Positive Chemical-Genetic | Mutation confers resistance to compound | Gene product may negatively regulate target or be in detoxification pathway |

| Synthetic Sick/Lethal (SSL) | Two gene deletions are detrimental in combination but viable individually | Gene products may function in parallel pathways or same complex |

| Cryptagen | Compound shows genotype-specific inhibition | Reveals latent activities against specific genetic backgrounds |

Cross-Species Applications

Bacterial Outer Membrane Studies

Chemical-genetic interaction mapping has been successfully applied to study outer membrane biogenesis and permeability in Escherichia coli. The Outer Membrane Interaction (OMI) Explorer database compiles genetic interactions involving outer membrane-related gene deletions crossed with 3,985 nonessential gene and sRNA deletions [15].

Key findings from bacterial applications include:

- Permeability Assessment: Screening with antibiotics excluded by the outer membrane (vancomycin, rifampin) reveals genetic determinants of membrane integrity [15].

- Pathway Connectivity: SSL interactions connect biosynthetic pathways for enterobacterial common antigen (ECA) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), revealing functional relationships in membrane assembly [15].

- Antibiotic Enhancement: Identification of genetic perturbations that increase membrane permeability to existing antibiotics, offering potential combination therapy strategies [15].

Pathway Analysis and Visualization Tools

Advanced visualization tools enable researchers to interpret chemical-genetic interactions in the context of known biological pathways:

- ChiBE (Chisio BioPAX Editor): Open-source tool for visualizing and analyzing pathway models in BioPAX format, with integrated access to Pathway Commons database [16].

- Pathway Commons: Centralized resource that aggregates biological pathway and interaction data from multiple databases, representing information in standardized BioPAX format [17].

- Cytoscape: Network visualization platform with plugins for analyzing chemical-genetic interaction networks and integrating with other functional genomics data [16].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource | Type | Function/Application | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deletion Mutant Collections | Biological | Comprehensive sets of gene deletion strains for fitness profiling | S. cerevisiae KO collection, E. coli Keio collection |

| Chemical Libraries | Compound | Diverse small molecules for screening against mutant collections | FDA-approved drugs, natural products, synthetic compounds |

| Pathway Databases | Computational | Reference pathways for functional annotation | Pathway Commons [17], KEGG, Reactome |

| BioPAX Tools | Software | Visualization and analysis of pathway data | ChiBE [16], Paxtools |

| Genetic Interaction Networks | Data | Reference networks for interpreting chemical-genetic profiles | BioGRID, E-MAP databases |

Chemical-genetic interaction profiling and fitness profiling represent powerful, unbiased approaches for elucidating compound mode-of-action and gene function. The integration of these data with genetic interaction networks through methods like CG-TARGET enables accurate prediction of biological processes affected by chemical compounds. As these approaches expand to additional model systems and pathogenic species, they offer increasing potential for drug discovery and functional genomics. The continuing development of computational methods, particularly machine learning approaches for predicting compound synergism, further enhances the utility of chemical-genetic interaction data across diverse biological applications.

Chemical-genomic profiling represents a powerful systems-level approach in biological research and drug discovery, enabling the comprehensive characterization of how genetic background influences cellular response to chemical compounds. This whitepaper examines established and emerging comparative frameworks for chemical-genomic profiling across species, with particular emphasis on bridging fundamental research in model organisms like yeast with applied studies in pathogenic systems such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). These cross-species approaches are revolutionizing target deconvolution research—the process of identifying the molecular targets of bioactive compounds—by leveraging conserved biological pathways and enabling the transfer of mechanistic insights from tractable model systems to clinically relevant pathogens.

The integration of chemical-genomic approaches across species boundaries creates a powerful paradigm for understanding compound mechanism of action (MOA). By comparing chemical-genetic interaction profiles between evolutionarily distant organisms, researchers can distinguish conserved, core biological targets from species-specific effects, accelerating the development of novel antimicrobials with defined molecular mechanisms. This technical guide outlines the core methodologies, computational frameworks, and experimental protocols that enable effective cross-species chemical genomic investigations for target deconvolution research.

Core Profiling Platforms and Their Applications

High-Throughput Cytological Profiling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Recent advances in high-content imaging have enabled the development of a high-throughput cytological profiling pipeline specifically optimized for Mtb clinical strains. This system quantifies single-bacterium morphological and physiological traits related to DNA replication, redox state, carbon metabolism, and cell envelope dynamics through OD-calibrated feature analysis and high-content microscopy [18]. The platform addresses several technical challenges specific to mycobacteria, including their propensity to form aggregates and their lipid-rich cell envelopes that complicate adhesion to imaging surfaces.

The methodology employs a customized 96-well molding toolset that can be fabricated using commercial-grade 3D printers or repurposed from pipette tip box accessories. Key innovations include a xylene-Triton X-100 emulsion that effectively disperses Mtb clumps while preserving morphological and chemical fluorescence staining properties, and a two-stage staining protocol consisting of pre-fixation cell wall labeling using fluorescent D-amino acids (FDAAs) followed by post-fixation on-gel staining with target-specific probes such as DAPI and Nile Red [18]. The image analysis pipeline utilizes MOMIA2 (Mycobacteria Optimized Microscopy Image Analysis), a Python package that implements trainable classifiers for automated anomaly detection and removal, enabling accurate segmentation and quantification of diverse cellular features including cell size, length, width, lipid droplet content, DNA content, and subcellular distribution patterns.

When applied to 64 Mtb clinical isolates from lineages 1, 2, and 4, this approach demonstrated that cytological phenotypes recapitulate genetic relationships and exhibit both lineage- and density-dependent dynamics. Notably, researchers identified a link between a convergent "small cell" phenotype and a convergent ino1 mutation associated with an antisense transcript, suggesting a potential non-canonical regulatory mechanism under selection [18]. This platform provides a resource-efficient approach for mapping Mtb's phenotypic landscape and uncovering cellular traits that underlie its evolution.

Reference-Based Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling

The PROSPECT (PRimary screening Of Strains to Prioritize Expanded Chemistry and Targets) platform represents a sophisticated approach for antibiotic discovery in Mtb that simultaneously identifies whole-cell active compounds while providing mechanistic insights necessary for hit prioritization [19] [20]. This system measures chemical-genetic interactions between small molecules and pooled Mtb mutants, each depleted of a different essential protein, through next-generation sequencing of hypomorph-specific DNA barcodes.

The Perturbagen CLass (PCL) analysis method infers a compound's mechanism of action by comparing its chemical-genetic interaction profile to those of a curated reference set of known molecules. In leave-one-out cross-validation, this approach correctly predicts MOA with 70% sensitivity and 75% precision, with comparable results (69% sensitivity, 87% precision) achieved on a test set of 75 antitubercular compounds with known MOA [19]. The platform has successfully identified novel chemical scaffolds targeting QcrB, a subunit of the cytochrome bcc-aa3 complex involved in respiration, including compounds that initially lacked wild-type activity but were subsequently optimized through chemical synthesis to achieve potency.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Reference-Based MOA Prediction Platforms

| Platform | Reference Set Size | Sensitivity | Precision | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROSPECT/PCL | 437 compounds | 70% | 75% | Mtb antibiotic discovery |

| PPIKG System | 1088 to 35 candidate proteins | N/A | N/A | p53 pathway activator screening |

Knowledge Graph-Based Target Deconvolution

A novel integrated approach combining protein-protein interaction knowledge graphs (PPIKG) with molecular docking techniques has shown promise for streamlining target deconvolution from phenotypic screens [6]. This method addresses the fundamental challenge of linking observed phenotypes to molecular targets by leveraging structured biological knowledge to prioritize candidate targets for experimental validation.

In a case study focused on p53 pathway activators, researchers constructed a PPIKG encompassing proteins and interactions relevant to p53 signaling. This approach narrowed candidate proteins from 1088 to 35, significantly reducing the time and cost associated with conventional target identification [6]. Subsequent molecular docking and experimental validation identified USP7 as a direct target of the p53 pathway activator UNBS5162, demonstrating the power of this integrated computational-experimental framework.

The PPIKG methodology is particularly valuable for understanding compound effects in evolutionarily conserved pathways like p53 signaling, where cross-species comparisons can reveal core mechanisms while highlighting species-specific adaptations. This approach can be extended to microbial systems, including mycobacterial pathogenesis pathways, to accelerate target deconvolution for compounds identified in phenotypic screens.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

High-Content Cytological Profiling Protocol for Mtb

Sample Preparation:

- Culture Mtb strains to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.4-0.6) in appropriate medium.

- Fix bacterial cells with 4% formaldehyde for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Treat fixed samples with xylene-Triton X-100 emulsion (2:1 ratio) for 20 minutes with gentle agitation to disperse aggregates.

- Pellet cells by centrifugation at 3,500 × g for 10 minutes and resuspend in phosphate-buffered saline.

Immobilization and Staining:

- Load samples onto custom-fabricated 96-well pedestal plates and centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 15 minutes to immobilize cells.

- Perform pre-fixation cell wall labeling with fluorescent D-amino acids (FDAAs) for 30 minutes.

- Implement post-fixation on-gel staining with DAPI (1 µg/mL) for DNA content and Nile Red (5 µg/mL) for lipid droplets for 45 minutes in the dark.

Image Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire images using a motorized inverted microscope with a 100× oil immersion objective across five fluorescence channels.

- Capture 24 fields of view per sample, requiring approximately 3-3.5 minutes per sample.

- Process images using MOMIA2, which includes:

- Automated segmentation of individual bacterial cells

- Anomaly detection and removal via trainable classifiers

- Extraction of morphological, intensity, and subcellular distribution features

- Normalize features using LOWESS-trendline-based interpolation to account for culture density effects.

PROSPECT Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling

Strain Pool Preparation:

- Generate a pool of hypomorphic Mtb strains, each engineered with doxycycline-inducible degradation tags on essential genes.

- Each strain contains a unique DNA barcode for tracking population dynamics.

- Maintain strains in liquid culture with appropriate antibiotics and induce protein depletion with 100 ng/mL doxycycline for 24 hours prior to screening.

Compound Screening:

- Array compounds in 384-well plates using acoustic dispensing technology.

- Add hypomorph pool to each well at approximately 10^6 CFU/mL.

- Incubate plates for 7-10 days at 37°C across a range of compound concentrations (typically 0.1-50 µM).

Barcode Sequencing and Analysis:

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and extract genomic DNA.

- Amplify barcode regions with indexed primers for multiplexed sequencing.

- Sequence on Illumina platform to achieve >1000x coverage per barcode.

- Quantify barcode abundances by mapping sequences to a barcode reference file.

- Calculate chemical-genetic interaction scores as log2(fold-change) relative to DMSO control.

PCL Analysis for MOA Prediction:

- Compile a reference set of compounds with known MOAs (e.g., 437 compounds).

- Generate CGI profiles for reference compounds across multiple concentrations.

- For each test compound, compute similarity scores to all reference profiles using Pearson correlation.

- Assign MOA predictions based on the highest similarity scores exceeding a predetermined threshold.

- Validate predictions through follow-up experiments, including resistance mutation mapping and biochemical assays.

Visualization of Cross-Species Comparative Frameworks

Workflow for Cross-Species Chemical Genomic Profiling

Knowledge Graph-Enhanced Target Deconvolution

Integrated Phenotypic and Genomic Screening Platform

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Species Chemical Genomic Profiling

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in Target Deconvolution |

|---|---|---|

| Custom 96-well pedestal plates | Immobilize bacterial cells for high-content imaging | Enables single-cell resolution phenotypic profiling in Mtb [18] |

| Xylene-Triton X-100 emulsion | Disperses bacterial aggregates while preserving morphology | Critical for accurate image segmentation of mycobacterial samples [18] |

| Fluorescent D-amino acids (FDAAs) | Label peptidoglycan in bacterial cell walls | Visualizes cell wall biosynthesis and morphology in live cells [18] |

| Hypomorphic Mtb strain pool | Collection of 400+ strains with depleted essential genes | Enables chemical-genetic interaction profiling via PROSPECT [19] |

| DNA barcode system | Unique sequences for tracking strain abundance | Allows multiplexed fitness measurements via NGS [19] |

| Protein-protein interaction knowledge graphs (PPIKG) | Computational framework for biological knowledge representation | Prioritizes candidate targets from phenotypic screens [6] |

| MOMIA2 image analysis | Mycobacteria-optimized microscopy image analysis | Extracts quantitative features from cytological profiles [18] |

| Reference compound sets | Curated collections with known mechanisms of action | Enables MOA prediction via similarity scoring in PCL analysis [19] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

Cross-species comparative frameworks for chemical genomic profiling represent a transformative approach in modern drug discovery, particularly for challenging pathogens like Mtb. The integration of high-content cytological profiling with chemical-genetic interaction mapping and computational knowledge graphs creates a powerful ecosystem for accelerating target deconvolution and mechanism of action determination. These approaches leverage evolutionary conservation while accounting for species-specific biology, enabling more efficient translation of findings from model systems to pathogenic contexts.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas. First, the expansion of reference compound sets with well-annotated mechanisms of action will enhance the predictive power of similarity-based approaches like PCL analysis. Second, improvements in knowledge graph construction and integration of multi-omics data will refine computational target prioritization. Third, advances in single-cell profiling technologies will enable even more detailed characterization of heterogeneous responses to chemical perturbations. Finally, the development of standardized cross-species comparison metrics will facilitate more systematic translation of findings from model organisms to pathogens.

As these technologies mature, cross-species chemical genomic profiling is poised to become a cornerstone of antibiotic discovery and development, addressing the critical need for novel therapeutic strategies against drug-resistant pathogens like Mtb. By providing a comprehensive framework for linking chemical perturbations to molecular targets across evolutionary distance, these approaches will significantly accelerate the identification and validation of new antibiotic targets and lead compounds.

Methodological Platforms and Cross-Species Applications

Barcode-based profiling represents a transformative approach in functional genomics, enabling the systematic and parallel analysis of complex genetic populations. This technology utilizes short, unique DNA or RNA sequences as molecular identifiers ("barcodes") to track the identity, abundance, and functional behavior of thousands of biological specimens simultaneously within pooled formats [21] [22]. In the context of chemical genomic profiling for target deconvolution, barcoding allows researchers to identify the cellular targets and mechanisms of action of bioactive compounds by observing how systematic genetic perturbations affect compound sensitivity [22]. The power of this methodology lies in its scalability; by leveraging next-generation sequencing (NGS) to quantitatively monitor barcode abundances, researchers can conduct highly replicated experiments across vast numbers of genotypes with minimal resources compared to traditional arrayed formats [21] [23].

The application of barcode-based profiling in model organisms such as yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and Escherichia coli has been particularly impactful, leveraging their well-characterized genetics, rapid growth, and the availability of comprehensive mutant collections [22] [24]. For target deconvolution research, which aims to identify the protein targets and molecular pathways through which small molecule compounds exert their effects, these organisms serve as powerful, genetically tractable systems. Chemical genomic profiles generated in these models provide an unbiased, whole-cell view of the cellular response to compounds, revealing functional insights that guide therapeutic development [22]. This technical guide details the core methodologies, experimental protocols, and applications of barcode-based profiling in yeast and E. coli, providing a framework for implementing these approaches in chemical biology and drug discovery pipelines.

Core Barcoding Methodologies and Their Applications

Barcode-based profiling encompasses a diverse toolkit of methods tailored to address specific biological questions. The table below summarizes the principal barcoding approaches applicable to yeast and E. coli, their core mechanisms, and primary applications in research.

Table 1: Core Barcoding Methods in Yeast and E. coli

| Method Name | Organism | Core Principle | Primary Application in Research | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Genomics [22] | Yeast | Pooled fitness screening of barcoded gene deletion mutants exposed to compounds. | Target deconvolution and mode-of-action studies for bioactive compounds. | Unbiased, whole-cell assay; predicts cellular targets. |

| NICR Barcoding [21] | Yeast | Nested serial cloning to combine gene variants with associated barcodes for tracking replicates. | Studying phenotypic effects of combinatorial genotypes (e.g., multi-gene complexes). | Enables high replication for complex genotypes in pooled format. |

| Transcript Barcoding [25] | E. coli | Engineering unique DNA barcodes into transcripts to measure gene expression. | Parallel measurement of promoter activity/construct expression in different environments. | High-throughput expression profiling in complex conditions (e.g., gut). |

| Chromosomal Barcoding [24] | E. coli | Markerless insertion of unique barcodes into the chromosome. | Multiplexed phenotyping and tracking of evolved lineages in competition experiments. | Allows tracking without antibiotic resistance markers. |

| CloneSelect [26] | Yeast, E. coli | Barcode-specific CRISPR base editing to trigger reporter expression in target clones. | Retrospective isolation of specific clones from a heterogeneous population. | Enables isolation of live clones based on phenotype from stored pools. |

The workflow for a typical barcode-based profiling experiment follows a logical progression from library preparation to sequencing and data analysis, as visualized below.

Figure 1: Generalized workflow for barcode-based profiling experiments, illustrating the key stages from library construction to data analysis.

Barcode-Based Profiling in Yeast

Yeast Chemical Genomic Profiling for Target Deconvolution

Chemical genomic profiling in yeast is a powerful, unbiased method for determining the mode of action of bioactive compounds. The core of this approach is the pooled yeast deletion collection, comprising thousands of non-essential gene deletion mutants, each tagged with a unique 20-mer DNA barcode [22]. When this pool is exposed to a compound of interest, mutants that are hypersensitive or resistant to the compound will decrease or increase in abundance, respectively, relative to the control population. The resulting chemical genomic profile—the pattern of fitness defects across all mutants—provides a functional signature that can be compared to profiles of compounds with known targets to generate hypotheses about the test compound's mechanism [22].

A key strength of this method is its compatibility with high-throughput sequencing, allowing for extreme multiplexing. Dozens of compound conditions can be processed and sequenced simultaneously by incorporating sample-specific index tags into the PCR primers, dramatically reducing the cost and time per screen [22]. This scalability makes it ideal for profiling novel compounds, especially when they are scarce.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Yeast Chemical Genomic Profiling

| Reagent / Tool | Description | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Yeast Deletion Collection | A pool of ~5,000 non-essential haploid knock-out strains, each with a unique DNA barcode [22]. | Provides the genotypically diverse population for the pooled fitness screen. |

| YPD + G418 Agar/Medium | Standard yeast growth medium supplemented with the antibiotic G418 (Geneticin) [22]. | Used for arraying and growing the deletion collection; G418 maintains selection for the knockout cassette. |

| Molecular Biology Kits | Genomic DNA extraction kits and high-fidelity PCR kits (e.g., Q5, KAPA HiFi) [22] [23]. | Essential for isolating barcodes from yeast pools and preparing them for sequencing with minimal errors. |

| Indexed PCR Primers | Primers that amplify the barcodes and add Illumina adapters and sample-specific indices [22]. | Enables multiplexing of many samples in a single sequencing run by tagging each sample's reads. |

Experimental Protocol: Chemical Genomic Screen in Yeast

1. Pool Preparation and Compound Exposure:

- The starting pool is created by mixing the individual mutant strains from the deletion collection. It is crucial to create a large, homogeneous master pool to avoid batch effects in multiple screens [22].

- For a screen, the pooled yeast is inoculated into fresh medium containing a sub-inhibitory concentration of the compound of interest. A vehicle control is run in parallel. Cultures are typically grown for 6-20 generations to allow fitness differences to manifest [22] [23].

2. Genomic DNA Extraction and Barcode Amplification:

- Cells are harvested from the endpoint cultures, and genomic DNA is extracted. The barcodes are then amplified from the genomic DNA in a two-step PCR process [23].

- First PCR: Uses primers that bind the common sequences flanking the barcode and incorporate unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and a partial Illumina adapter sequence. UMIs are critical for correcting for PCR amplification bias and reducing technical noise [23].

- Second PCR: Adds the full Illumina adapters and sample-specific index sequences, enabling multiplexed sequencing. The final PCR product is purified, quantified, and pooled with other samples for sequencing [22] [23].

3. Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- The pooled libraries are sequenced on an Illumina platform (e.g., MiSeq, HiSeq). The resulting reads are demultiplexed based on their sample index.

- Bioinformatic processing involves counting the abundance of each barcode (correcting for UMIs) in the treated and control samples. A fitness score for each mutant is calculated, often as the log₂ ratio of its relative abundance in the final versus initial population [22] [23].

- Mutants with statistically significant negative fitness scores are classified as hypersensitive, suggesting the deleted gene is related to the compound's mechanism of action. The full profile is compared to databases of known profiles to predict the compound's target [22].

Barcode-Based Profiling in E. coli

Chromosomal Barcoding for Multiplexed Phenotyping

In E. coli, a common barcoding strategy involves the markerless integration of unique barcodes directly into the chromosome. This allows for the creation of a defined library of strains that can be tracked in complex, pooled populations without the use of antibiotic resistance markers, which could interfere with studies on antibiotic resistance [24]. One effective method uses a dual-auxotrophic selection system to insert a random 12-nucleotide barcode at a specific genomic locus, such as within the leucine operon. This process creates a library of hundreds to thousands of uniquely barcoded, isogenic clones [24].

This library is exceptionally useful for adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) experiments. By initiating parallel evolution experiments with different barcoded clones, researchers can track the dynamics of multiple evolving lineages simultaneously in a single flask. This multiplexed approach allows for the efficient characterization of phenotypic outcomes, such as antibiotic resistance levels, and reveals population dynamics that would be laborious to detect by analyzing clones individually [24].

Experimental Protocol: Tracking Evolved Lineages in E. coli

1. Library Construction and Evolution Experiment:

- The barcoded library is constructed via a two-step homologous recombination process. First, a target gene (e.g., leuD) is knocked out with a selectable marker. Second, the gene is restored using a repair fragment that contains a random 12-nucleotide barcode, resulting in a markerless, barcoded strain [24].

- For an ALE experiment, multiple uniquely barcoded clones are inoculated into a culture medium containing a selective pressure (e.g., an antibiotic). The culture is passaged serially, typically with increasing concentrations of the selective agent over many generations [24].

2. Phenotyping via Barcode Sequencing (Bar-Seq):

- Population samples are collected throughout the evolution experiment. Genomic DNA is extracted from these samples.

- The region containing the barcode is amplified via PCR using primers with Illumina adapter tails. The resulting amplicons are sequenced to high depth [24].

- The relative abundance of each barcode is tracked over time. An increase in a barcode's frequency indicates the expansion of a fitter lineage. The fitness of a lineage can be calculated from its change in frequency between time points [23] [24].

3. Correlation with Traditional Phenotyping:

- The fitness data derived from barcode sequencing can be validated against traditional methods. Studies have shown a strong positive correlation between the relative fitness measured by barcode abundance in a pool and the growth rate of isolated clones measured in individual cultures [24].

- This multiplexed approach drastically reduces the workload, as it replaces thousands of individual growth assays with a single, pooled sequencing assay, enabling high-throughput phenotypic characterization of evolved populations.

Successful implementation of barcode-based profiling relies on a core set of reagents and computational tools. The following table catalogs the essential components for establishing this technology in a research setting.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Barcode-Based Profiling

| Category | Item | Specific Examples / Characteristics | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Collections | Yeast Deletion Collection | ~5,000 non-essential gene knockouts with unique barcodes [22]. | Foundational resource for chemical genomic screens. |

| Barcoded E. coli Library | Library of clones with markerless, chromosomal 12-nt barcodes [24]. | Enables multiplexed tracking and phenotyping in bacterial evolution. | |

| Molecular Biology Kits & Enzymes | High-Fidelity Polymerase | Q5 Hot Start, KAPA HiFi [25] [23]. | Accurate amplification of barcode libraries with minimal errors. |

| DNA Purification Beads | SPRI/AMPure XP beads [23] [27]. | Size-selective purification of PCR amplicons and libraries. | |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | NEB Gibson Assembly [21] [28]. | Seamless cloning for constructing combinatorial barcode plasmids. | |

| Specialized Reagents | Yeast Lysis Buffer | Contains Zymolyase, DTT, and detergent [23]. | Efficient breakdown of yeast cell wall for genomic DNA release. |

| Binding Buffer | High-salt, chaotropic buffer (e.g., with guanidine thiocyanate) [23]. | Binds nucleic acids to silica membranes/beads in DNA cleanup. | |

| Primers & Oligos | Indexed PCR Primers | Contain Illumina P5/P7, i5/i7 indices, and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) [22] [23]. | Amplification and multiplexing of barcodes for NGS. |

| Barcoding Oligonucleotides | Semi-randomized sequences for in-vitro barcode generation [27]. | Source of high-complexity barcodes for library construction. |

Barcode-based profiling in yeast and E. coli has established itself as a cornerstone technique for modern functional genomics and chemical biology. By transforming complex biological questions into a format decipherable by high-throughput sequencing, these methods provide an unparalleled ability to conduct highly replicated, quantitative experiments at scale. Within the framework of target deconvolution, chemical genomic profiling in yeast offers an unbiased, whole-cell approach to illuminate the mechanism of action of novel therapeutic compounds, guiding downstream research in more complex systems. In E. coli, chromosomal barcoding enables the efficient, multiplexed analysis of population dynamics during adaptive evolution, revealing evolutionary trajectories and collateral effects of resistance development.

The continued refinement of these methods—through the incorporation of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to reduce PCR noise [23], the development of new systems for retrospective clone isolation like CloneSelect [26], and the creation of more complex combinatorial libraries [21]—promises to further enhance their precision, scale, and applicability. As the fields of drug discovery and functional genomics continue to prioritize high-throughput and systematic approaches, barcode-based profiling in these foundational model organisms will remain an essential strategy for linking genetic information to phenotypic outcomes.

PRimary screening Of Strains to Prioritize Expanded Chemistry and Targets (PROSPECT) is a sophisticated antimicrobial discovery platform that represents a significant advancement in the field of antibiotic development, particularly for challenging pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). PROSPECT fundamentally transforms conventional screening approaches by simultaneously identifying whole-cell active compounds while providing immediate mechanistic insights into their mode of action [19]. This dual-capability addresses a critical bottleneck in antibiotic discovery, where traditional whole-cell screens often yield hits devoid of target information, and target-based biochemical screens frequently produce inhibitors that lack cellular activity [29] [19].

The platform operates on the principle of chemical-genetic interaction profiling, measuring the fitness changes of pooled bacterial mutants—each depleted of a different essential protein target—in response to small molecule treatment [29] [19]. In the context of Mtb, which contains approximately 600 essential genes representing diverse biological processes, PROSPECT offers unprecedented access to this potential target space [19]. By screening compounds against hypomorphic strains (mutants with reduced gene function), PROSPECT achieves significantly higher sensitivity compared to conventional wild-type screening, identifying compounds that would typically elude discovery due to their initially modest potency [19] [30]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for Mtb drug discovery, where the chemical-genetic interaction profiles not only facilitate hit identification but also enable immediate target hypothesis generation and hit prioritization before embarking on costly chemistry optimization campaigns [19] [31].

Core Methodology and Experimental Workflow

Strain Engineering and Essential Gene Depletion

The PROSPECT platform relies on the creation of a comprehensive library of hypomorphic Mtb strains, each engineered to be deficient in a different essential gene product. Early implementations utilized target proteolysis or promoter replacement strategies requiring laborious homologous recombination [29]. More recent advancements have incorporated CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) technology to more efficiently generate targeted gene knockdowns [29]. In this approach, a dead Cas9 (dCas9) system derived from Streptococcus thermophilus CRISPR1 locus is programmed with specific sgRNAs to achieve transcriptional interference of essential genes in mycobacteria [29]. The CRISPR guides themselves serve dual purposes—mediating gene knockdown and functioning as mutant barcodes to enable multiplexed screening [29].

Table: Strain Engineering Methods for PROSPECT Implementation

| Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Proteolysis | Inducible degradation of essential proteins | Precise temporal control | Requires laborious homologous recombination |

| Promoter Replacement | Transcriptional control via inducible promoters | Tunable expression levels | Extensive genetic manipulation needed |

| CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) | Transcriptional repression using dCas9-sgRNA complexes | Rapid strain generation; easily programmable | Potential for variable knockdown efficiency |

For genome-wide PROSPECT applications, researchers have engineered hypomorphic strains targeting 474 essential Mtb genes, enabling comprehensive coverage of the vulnerable target space [31]. In mini-PROSPECT configurations, focused subsets of strains targeting specific pathways—such as cell wall synthesis or surface-localized targets—can be utilized for more targeted screening campaigns [29].

Pooled Screening and Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling

The core PROSPECT screening protocol involves exposing pooled hypomorphic strains to compound libraries under controlled conditions. The workflow can be broken down into several key stages:

Pool Preparation and Compound Exposure: A pool of barcoded hypomorphic strains is cultured together and exposed to compounds at various concentrations, typically in dose-response format [19]. This multiplexed approach allows for high-throughput screening, with previously reported screens probing more than 8.5 million chemical-genetic interactions [31].

Fitness Measurement via Barcode Sequencing: Following compound exposure, the relative abundance of each hypomorphic strain in the pool is quantified using next-generation sequencing of the strain-specific barcodes [29]. The fitness change for each strain is calculated as the log(fold-change) in barcode abundance after treatment compared to vehicle control [30].

Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profile Generation: For each compound-concentration combination, a vector of fitness changes across all hypomorphic strains is compiled, creating a unique chemical-genetic interaction profile (CGIP) that serves as a functional fingerprint of the compound's activity [19] [30].

The entire screening process is summarized in the following workflow:

Data Analysis and Mechanism of Action Prediction

The interpretation of PROSPECT data has been significantly enhanced through the development of Perturbagen CLass (PCL) analysis, a computational method that infers a compound's mechanism of action by comparing its chemical-genetic interaction profile to those of a curated reference set of compounds with known mechanisms [19] [20]. This reference-based approach involves:

Reference Set Curation: Compiling a comprehensive set of compounds with annotated mechanisms of action and known or predicted anti-tubercular activity. Recent implementations have utilized reference sets of 437 compounds with published mechanisms [19].

Profile Similarity Assessment: Comparing the CGI profile of test compounds against all reference profiles using similarity metrics to identify the closest matches.

MOA Assignment: Predicting mechanism of action based on the highest similarity matches from the reference set, with cross-validation studies demonstrating 70% sensitivity and 75% precision in leave-one-out validation [19] [20].

Table: Performance Metrics of PCL Analysis in MOA Prediction

| Validation Set | Sensitivity | Precision | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation | 70% | 75% | 437-compound reference set with published MOA |

| GSK Test Set | 69% | 87% | 75 antitubercular compounds with known MOA |

| Unannotated GSK Compounds | N/A | N/A | 60 compounds assigned putative MOA from 10 classes |

The PCL analysis workflow operates as follows:

Key Applications and Case Studies

Discovery of Novel Inhibitor Classes

PROSPECT has demonstrated remarkable success in identifying new anti-tubercular compounds against diverse targets that have traditionally been challenging to address through conventional screening approaches. In a landmark screen of more than 8.5 million chemical-genetic interactions, PROSPECT identified over 40 compounds targeting various essential pathways including DNA gyrase, cell wall biosynthesis, tryptophan metabolism, folate biosynthesis, and RNA polymerase [31]. Importantly, PROSPECT primary screens identified over tenfold more hits compared to conventional wild-type Mtb screening alone, highlighting the enhanced sensitivity of the approach [31].

EfpA Inhibitor Discovery and Validation

A notable success story from PROSPECT screening is the identification and validation of EfpA inhibitors. PROSPECT enabled the discovery of BRD-8000, an uncompetitive inhibitor of EfpA—an essential efflux pump in Mtb [30]. Although BRD-8000 itself lacked potent activity against wild-type Mtb (MIC ≥ 50 μM), its chemical-genetic interaction profile provided clear target engagement evidence, enabling chemical optimization to yield BRD-8000.3, a narrow-spectrum, bactericidal antimycobacterial agent with good wild-type activity (Mtb MIC = 800 nM) [30].

Leveraging the chemical-genetic interaction profile of BRD-8000, researchers retrospectively mined PROSPECT screening data to identify BRD-9327, a structurally distinct small molecule EfpA inhibitor [30]. This demonstrates the power of PROSPECT's extensive chemical-genetic interaction dataset (7.5 million interactions in the reported screen) as a reusable resource for ongoing discovery efforts [30]. Importantly, these two EfpA inhibitors displayed synergistic activity and mutual collateral sensitivity—where resistance to one compound increased sensitivity to the other—providing a novel strategy for suppressing resistance emergence [30].

Respiration Inhibitor Identification

PROSPECT has proven particularly effective in identifying compounds targeting Mtb respiration pathways. Application of PCL analysis to a collection of 173 compounds previously reported by GlaxoSmithKline revealed that a remarkable 38% (65 compounds) were high-confidence matches to known inhibitors of QcrB, a subunit of the cytochrome bcc-aa3 complex involved in respiration [19]. Researchers validated the predicted QcrB mechanism for the majority of these compounds by confirming their loss of activity against mutants carrying a qcrB allele known to confer resistance to known QcrB inhibitors, and their increased activity against a mutant lacking cytochrome bd—established hallmarks of QcrB inhibitors [19].

Furthermore, PROSPECT screening of ~5,000 compounds from unbiased chemical libraries identified a novel pyrazolopyrimidine scaffold that initially lacked wild-type activity but showed a high-confidence PCL-based prediction for targeting the cytochrome bcc-aa3 complex [19]. Subsequent target validation confirmed QcrB as the target, and chemical optimization efforts successfully achieved potent wild-type activity [19].

Technical Implementation and Research Reagents

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PROSPECT Implementation

| Reagent/Resource | Function in PROSPECT | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|

| Hypomorphic Strain Library | Essential gene depletion for sensitivity enhancement | 474 engineered Mtb strains covering essential genes [31] |

| CRISPRi Plasmid System | Efficient gene knockdown for strain generation | pJR965 with Sth1 dCas9 for mycobacterial CRISPRi [29] |

| Strain Barcodes | Multiplexed screening and sequencing quantification | Unique DNA barcodes for each hypomorph strain [29] |

| Reference Compound Set | MOA prediction via PCL analysis | 437 compounds with annotated mechanisms [19] |

| Sequencing Platform | Barcode abundance quantification | Next-generation sequencing for fitness measurement [29] |

| Data Analysis Pipeline | CGI profile generation and similarity assessment | Custom algorithms for PCL analysis [19] |

Protocol Optimization and Technical Considerations

Successful implementation of PROSPECT requires careful optimization of several technical parameters. For strain engineering, the two-step method utilizing fluorescent reporters (mCherry) and anhydrotetracycline-inducible systems has proven effective for distinguishing correct transformants from background mutants in CRISPRi strain construction [29]. In pooled screening, maintaining balanced representation of all hypomorphic strains is critical, requiring preliminary validation of pool composition and growth characteristics [29].