Chemical Genetics Unveils Cross-Resistance Patterns: A Systematic Framework for Smarter Drug Development

This article explores how chemical genetics, a high-throughput functional genomics approach, is revolutionizing our understanding of cross-resistance and its counter-phenomenon, collateral sensitivity.

Chemical Genetics Unveils Cross-Resistance Patterns: A Systematic Framework for Smarter Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores how chemical genetics, a high-throughput functional genomics approach, is revolutionizing our understanding of cross-resistance and its counter-phenomenon, collateral sensitivity. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we detail how systematic profiling of genome-wide mutant libraries against compound panels maps the complex networks of drug-pathogen interactions. The content covers foundational principles, key methodological advances like the Outlier Concordance–Discordance Metric (OCDM), and strategies to troubleshoot profiling data. We further validate these approaches with evidence from experimental evolution and discuss their application in designing intelligent drug cycling and combination therapies to outmaneuver resistance and extend the lifespan of existing and future therapeutics.

Decoding Cross-Resistance: Foundational Concepts and the Power of Systematic Mapping

The relentless evolution of antimicrobial resistance represents one of the most pressing challenges in modern medicine. When bacteria develop resistance to a specific antibiotic, this adaptation rarely occurs in isolation. Instead, it triggers a network of susceptibility changes to other antimicrobial agents—a phenomenon with critical implications for therapeutic strategies. Within this network, two contrasting patterns emerge: cross-resistance, where resistance to one drug confers resistance to another, and collateral sensitivity, where resistance to one drug increases susceptibility to another [1]. Understanding the balance between these opposing evolutionary trajectories is paramount for designing next-generation treatment protocols that can circumvent resistance development. Recent advances in chemical genetics have provided unprecedented insights into the systematic mapping of these interactions, revealing both the constraints and opportunities they present for antibiotic therapy [2]. This article delineates the fundamental distinctions between cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity, examines their underlying molecular mechanisms, and explores how these evolutionary trade-offs might be harnessed to combat the escalating antibiotic resistance crisis.

Defining the Concepts: Cross-Resistance vs. Collateral Sensitivity

Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions

- Cross-resistance: This occurs when a single resistance mechanism confers reduced susceptibility to two or more antibiotics, typically from the same class [1]. For example, a mutation in a bacterial topoisomerase gene may confer resistance to multiple fluoroquinolone antibiotics simultaneously [3].

- Collateral sensitivity: In this evolutionary trade-off, the development of resistance to one antibiotic leads to increased susceptibility to a second, unrelated antibiotic [1] [4]. This creates a potential Achilles' heel that can be therapeutically exploited.

While cross-resistance often arises from mechanisms that affect antibiotics with similar structures or targets, collateral sensitivity typically emerges from the fitness costs or physiological compromises associated with the resistance mechanism itself [5]. For instance, a mutation that reduces membrane potential to resist aminoglycosides may simultaneously impair efflux pump activity that depends on that same membrane potential, thereby sensitizing bacteria to other drug classes [4].

The Chemical Genetics Perspective

Chemical genetics provides a powerful framework for systematically mapping these interactions. By analyzing how thousands of individual gene deletions affect sensitivity to various antibiotics, researchers can predict cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity relationships on a genomic scale [2]. This approach has revealed that these interactions are far more extensive than previously recognized, with one study identifying 404 cases of cross-resistance and 267 of collateral sensitivity in Escherichia coli alone—expanding known interactions by more than threefold [2].

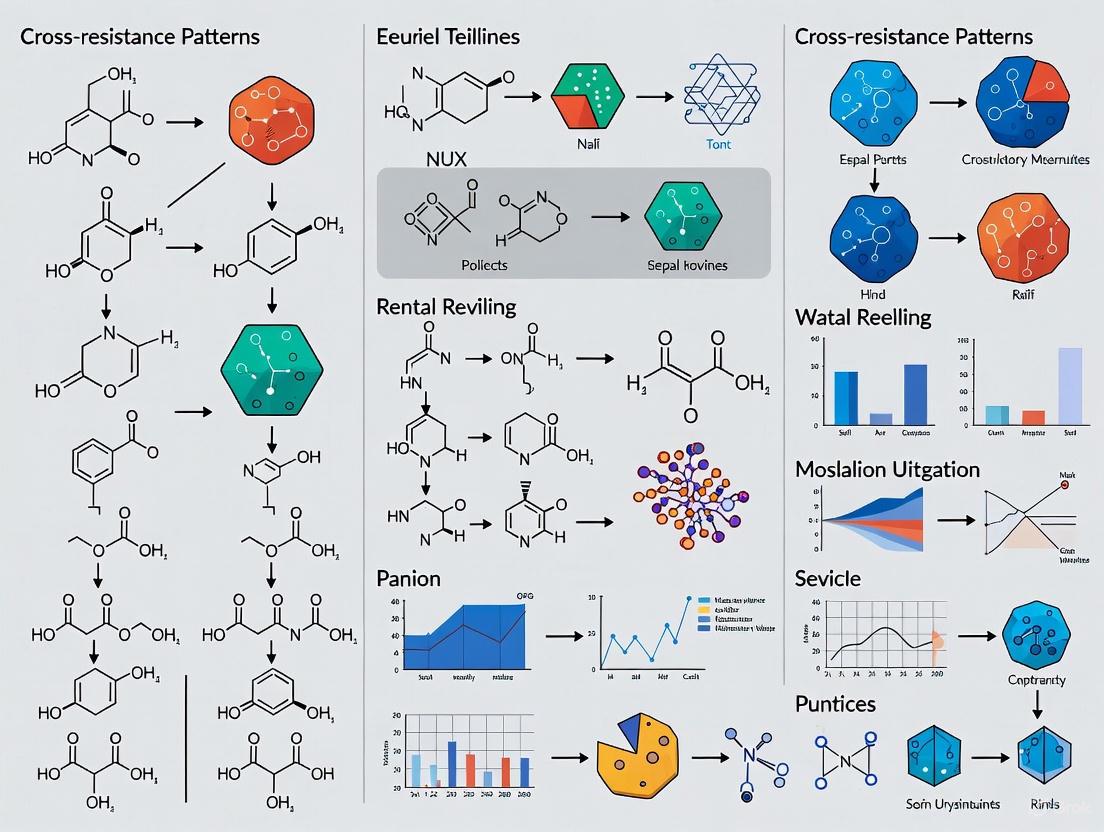

Diagram: Contrasting evolutionary pathways following antibiotic exposure. Cross-resistance limits future treatment options, while collateral sensitivity creates therapeutic opportunities.

Quantitative Landscape of Resistance Interactions

Systematic Mapping of Antibiotic Interactions

Chemical genetics approaches have enabled the comprehensive identification of cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity networks. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent large-scale studies:

Table 1: Documented Cross-Resistance and Collateral Sensitivity Interactions

| Measurement Parameter | Cross-Resistance | Collateral Sensitivity | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Documented Interactions | 404 cases [2] | 267 cases [2] | E. coli chemical genetics screen of 40 antibiotics [2] |

| Validation Rate | 91% (64/70 inferred interactions) [2] | 91% (64/70 inferred interactions) [2] | Experimental evolution validation [2] |

| Multi-Species Observation | Common within same antibiotic classes [6] | Kanamycin CS in 5 species resistant to chloramphenicol/tetracycline [6] | 6 bacterial species with induced resistance [6] |

| Conservation Across Strains | Varies by mechanism | pOXA-48 plasmid: CS to azithromycin conserved in 8/9 clinical E. coli isolates [7] | Clinical E. coli isolates carrying resistance plasmid [7] |

| Temporal Dynamics | More frequent in early adaptation [8] | Increases with further selection [8] | Enterococcus faecalis evolution over 8 days [8] |

The data reveal that collateral sensitivity is not merely a theoretical concept but a widespread phenomenon with significant potential for clinical exploitation. The high validation rate of predicted interactions (91%) underscores the reliability of chemical genetics approaches for mapping these relationships [2].

Key Molecular Mechanisms and Their Prevalence

Different resistance mechanisms produce characteristic patterns of collateral effects. The table below summarizes major mechanistic categories and their observed prevalence:

Table 2: Molecular Mechanisms Driving Collateral Sensitivity

| Mechanism Category | Specific Example | Resulting Collateral Sensitivity | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Potential Alteration | Reduced PMF for aminoglycoside resistance [4] | Increased susceptibility to drugs expelled by PMF-dependent efflux pumps [4] | E. coli laboratory evolution [4] |

| Efflux Pump Modification | AcrAB efflux system impairment [4] | Increased intracellular concentrations of multiple drug classes [4] | Gene expression and susceptibility profiling [4] |

| Target Site Mutation | fusA mutations (EF-G) in kanamycin-resistant strains [6] | Hypersensitivity to β-lactams [6] | 5 bacterial species with convergent evolution [6] |

| Transcriptional Rewiring | Mutations in regulatory genes [4] | Altered expression of stress response pathways [4] | Genomic analysis of evolved strains [4] |

| Plasmid Acquisition | pOXA-48 carbapenemase plasmid [7] | Increased susceptibility to azithromycin and colistin [7] | Clinical E. coli isolates [7] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Chemical Genetics Profiling

Chemical genetics leverages systematic mutant libraries to comprehensively map gene-drug interactions. The foundational protocol involves:

- Library Preparation: Utilizing the E. coli single-gene deletion library (Keio collection), which comprises ~4,000 individual knockout mutants [2].

- Fitness Profiling: Exposing the mutant library to a panel of antibiotics (typically 40+ drugs) and quantifying bacterial fitness using growth measurements [2].

- Score Calculation: Computing s-scores that compare mutant fitness in each antibiotic condition to their fitness across all conditions [2].

- Interaction Inference: Applying the Outlier Concordance-Discordance Metric (OCDM) to identify antibiotic pairs where resistance mutations to one drug consistently increase sensitivity to another [2].

This approach enables the systematic prediction of collateral sensitivity networks without the need for extensive experimental evolution for each drug pair.

Experimental Evolution and Validation

To validate predicted interactions, researchers employ controlled evolution experiments:

- Selection Protocol: Exposing bacterial populations to increasing concentrations of a selecting antibiotic through serial passaging for multiple generations (typically 60+ generations) [8].

- Time-Series Sampling: Isolating clones at regular intervals (e.g., every 2 days) to track evolutionary trajectories [8].

- Susceptibility Testing: Measuring minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) or half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of evolved strains against a panel of antibiotics [6] [8].

- Genomic Analysis: Sequencing resistant clones to identify causal mutations and correlate genotypes with collateral sensitivity profiles [6].

Diagram: Integrated workflow combining chemical genetics prediction with experimental evolution validation to identify and characterize collateral sensitivity interactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Systems

| Reagent/System | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli Keio Collection | Genome-wide single-gene knockout mutant library | Chemical genetics screening to identify gene-antibiotic interactions [2] |

| pOXA-48 Plasmid | Carbapenem-resistance conjugative plasmid | Studying collateral sensitivity associated with plasmid-borne resistance [7] |

| Outlier Concordance-Discordance Metric (OCDM) | Computational metric to identify CS/XR from chemical genetics data | Classifying antibiotic pairs into cross-resistance or collateral sensitivity categories [2] |

| Mutant Prevention Concentration (MPC) | Antibiotic concentration preventing single-step mutations | Evaluating resistance evolution at concentrations beyond MIC [3] |

| Disk Diffusion Assays | High-throughput susceptibility testing | Validating CS across diverse clinical isolates [7] |

Research Implications and Future Directions

The systematic mapping of collateral sensitivity networks opens promising avenues for addressing antibiotic resistance. Mathematical modeling suggests that CS-informed treatment schedules—including alternating therapies that exploit one-directional CS relationships—can suppress resistance evolution [9]. The conservation of CS patterns across diverse clinical isolates [7] and bacterial species [6] strengthens the potential for broad clinical application.

Future research should focus on expanding CS mapping to clinically relevant pathogens, elucidating the temporal dynamics of these relationships [8], and translating these findings into optimized treatment regimens. The integration of chemical genetics with experimental evolution provides a powerful framework for identifying exploitable evolutionary trade-offs, offering hope for extending the useful lifespan of existing antibiotics through smarter deployment strategies based on the fundamental principles of collateral sensitivity.

Chemical genetics is a powerful reverse genetics approach that systematically assesses the impact of genetic variation on the activity of a drug or chemical compound [10]. By measuring the quantitative fitness of a vast collection of genetic mutants when exposed to different chemicals, researchers can delineate a compound's complete cellular function—including its primary targets, its pathway into and out of the cell, and its mechanisms of cytotoxicity [10]. The field is propelled by technological advances that now enable the application of chemical genetics to almost any organism at an unprecedented throughput, making it an indispensable discovery engine in modern drug development [10].

The core principle of chemical genetics lies in its ability to map gene-chemical interactions on a genome-wide scale. This approach differs from broader chemical genomics, which includes large-scale screening of compound libraries for bioactivity against a specific cellular target or phenotype [10]. Chemical genetics specifically investigates how systematic genetic perturbations alter a cell's response to chemical treatment, creating rich datasets that reveal the complex functional relationships between small molecules and the biological systems they affect.

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

The chemical genetics workflow integrates systematic genetic perturbation with high-throughput phenotyping, followed by sophisticated computational analysis to extract biological insights.

Core Principles

Systematic Genetic Variance: Chemical-genetic approaches rely on genome-wide libraries containing mutants for each gene. These libraries can consist of loss-of-function (knockout, knockdown) or gain-of-function (overexpression) mutations and can be arrayed or pooled [10]. The creation of such libraries has been perfected in model organisms like yeast and E. coli and is now possible for a wide range of microbes and human cell lines [10].

Quantitative High-Throughput Phenotyping: Advances in barcoding strategies combined with next-generation sequencing allow for tracking the relative abundance—and thus fitness—of individual mutants in pooled libraries with exceptional throughput and dynamic range [10]. In arrayed formats, automation and advanced image processing enable the assessment of additional phenotypes beyond growth, including developmental processes like biofilm formation, sporulation, and morphological changes [10].

Guilt-by-Association Analysis: Compounds with similar chemical-genetic interaction profiles (or "signatures") are likely to share cellular targets and/or mechanisms of cytotoxicity [10]. This principle enables the classification of novel compounds through comparison to well-characterized reference molecules.

Experimental Workflow

The typical workflow for a chemical-genetics experiment involves the following key stages, as illustrated in the diagram below:

Diagram 1: Chemical genetics screening workflow.

The process begins with the preparation of a genome-wide mutant library, either pooled or arrayed. The library is then exposed to a compound of interest, typically at a sub-inhibitory concentration that induces a mild fitness defect (e.g., increasing the population doubling time by 2-fold) [11]. After a period of competitive growth (approximately 12 generations), the relative abundance of each mutant in the pool is determined, usually via deep sequencing of molecular barcodes [11]. Mutants that become under-represented indicate genes required for surviving the drug's effect (sensitivity-enhancing genes), while over-represented mutants reveal genes that confer resistance when perturbed (resistance-enhancing genes) [10] [11]. The compiled quantitative fitness scores for all mutants constitute the drug's unique signature, which can be compared to other signatures to infer common mechanisms.

Application in Mapping Cross-Resistance Patterns

Chemical-genetic profiling provides a powerful framework for understanding and predicting cross-resistance relationships between antimicrobial agents, a critical concern in combating drug resistance.

Revealing Determinants of Cross-Resistance

A key application of chemical genetics is the systematic assessment of cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity between drugs [10]. Cross-resistance occurs when a genetic mutation leads to reduced sensitivity to multiple drugs, while collateral sensitivity describes mutations that confer resistance to one drug but increase sensitivity to another [10]. Traditional methods of assessing these relationships involve evolving resistance to one drug and testing resistant clones against others, but this approach surveys only a limited number of potential resistance solutions [10].

Chemical genetics overcomes this limitation by simultaneously measuring the contribution of every non-essential gene to resistance across multiple compounds [11]. For example, a comprehensive study in E. coli that profiled 15 different antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) with diverse modes of action revealed that cross-resistance is prevalent only between AMPs with similar mechanisms [11]. This finding underscores that generalizations about AMP resistance are problematic, as resistance determinants vary considerably depending on the physicochemical properties and cellular targets of each peptide [11].

Experimental Data on Antimicrobial Peptide Cross-Resistance

The following table summarizes findings from a systematic chemical-genetic study of 15 AMPs, showing how they cluster based on their resistance determinants and modes of action [11]:

Table 1: Cross-Resistance Patterns and Characteristics of Antimicrobial Peptide Clusters

| Cluster | Primary Mode of Action | Representative AMPs | Key Physicochemical Properties | Cross-Resistance Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Membrane targeting/Pore-forming | Ceratotoxin A, Mastoparan | Lower isoelectric point, high hydrophobicity, propensity for secondary structure | High within-cluster, limited between-cluster |

| C2 | Membrane targeting/Pore-forming | Melittin, Cecropin A | Moderate hydrophobicity, strong helical propensity | High within-cluster, limited between-cluster |

| C3 | Mixed membrane & intracellular | Indolicidin, Protamine, CAP18 | Intermediate properties | Moderate within-cluster |

| C4 | Intracellular targeting | Bactenecin 5, PR-39 | High proline content, intrinsic structural disorder | Limited cross-resistance with membrane-targeting AMPs |

The data demonstrates that AMPs cluster according to their modes of action and physicochemical properties, with distinct genetic determinants underlying resistance to each cluster [11]. This clustering reveals that intracellular-targeting AMPs are less likely to induce cross-resistance to membrane-targeting human host-defense peptides than those that share the same broad mechanisms, providing valuable insights for designing therapeutic AMPs that minimize cross-resistance concerns [11].

Experimental Protocol for Cross-Resistance Assessment

Protocol: Chemical-Genetic Profiling for Cross-Resistance Prediction in E. coli

- Library Preparation: Employ a comprehensive plasmid library overexpressing all ~4,400 E. coli open reading frames (ORFs) [11].

- Chemical Treatment: Grow the pooled plasmid library in the presence of each AMP at a sub-inhibitory concentration that increases the population doubling time by 2-fold [11]. Include an untreated control for each experiment.

- Competitive Growth: Allow the pool to grow for approximately 12 generations under selective pressure to ensure sufficient differential enrichment or depletion of clones [11].

- Sequencing and Fitness Scoring: Isolate the plasmid pool from each selection and determine the relative abundance of each plasmid by deep sequencing. Calculate a chemical-genetic interaction score (fold-change value) for each gene by comparing plasmid abundances in treated versus untreated conditions [11].

- Hit Identification: Identify genes that significantly increase sensitivity (sensitivity-enhancing) or decrease sensitivity (resistance-enhancing) upon overexpression using appropriate statistical thresholds [11].

- Signature Comparison: Compute pairwise similarity scores between the chemical-genetic interaction profiles of all tested AMPs. Use robust clustering methods to group AMPs with similar profiles [11].

- Cross-Resistance Prediction: Interpret clusters as groups of compounds with a high potential for cross-resistance due to shared resistance mechanisms.

This protocol successfully identified that cross-resistance is not universal but specific to AMPs with similar modes of action, enabling more informed selection of combination therapies and drug design strategies [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Conducting chemical-genetic studies requires specialized biological reagents and computational tools. The table below details key resources essential for implementing these approaches.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Chemical-Genetic Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in Chemical Genetics | Example Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knockout Mutant Library | Loss-of-function collection | Identifies genes essential for survival under drug treatment (sensitivity genes) | S. cerevisiae, E. coli, various bacteria & fungi [10] |

| Overexpression Library | Gain-of-function collection | Reveals latent resistome; genes that confer resistance when overexpressed | E. coli (e.g., ASKA library) [11] |

| CRISPRi/a Library | Essential gene knockdown/activation | Identifies drug targets among essential genes; modulates gene dosage precisely | Various bacteria, human cell lines [10] |

| Molecular Barcodes | DNA barcodes | Enables tracking of mutant abundance in pooled screens via high-throughput sequencing | S. cerevisiae, E. coli [10] |

| Hypomorph Library | Essential gene partial depletion | Assesses role of essential genes in drug susceptibility by titrating gene expression | E. coli [11] |

The selection of an appropriate mutant library is foundational to experimental design. Pooled libraries with barcoded mutants offer superior throughput for fitness screens, while arrayed libraries are suitable for capturing more complex phenotypic readouts such as morphological changes [10]. Recent advances have made it feasible to construct such libraries for a wide range of microorganisms, dramatically expanding the scope of chemical-genetic applications [10].

Data Analysis and Visualization

Transforming raw sequencing data from chemical-genetic screens into biological insights requires specialized computational and visualization approaches.

Analytical Approaches

The initial step in data analysis involves calculating robust fitness scores for each mutant under drug treatment compared to control conditions. Following this, researchers employ machine learning algorithms to interpret the resulting interaction networks. For instance, Naïve Bayesian and Random Forest algorithms have been successfully trained with chemical-genetics data to predict drug-drug interactions [10]. These models help distinguish interactions reflective of a drug's primary mechanism of action from those related to general stress responses or pathways controlling intracellular drug concentration.

Visualization of Chemical-Genetic Interaction Networks

A critical step in analysis is visualizing the relationships between compounds based on their chemical-genetic profiles, which often involves clustering techniques. The following diagram represents the process of analyzing and visualizing these relationships to predict cross-resistance:

Diagram 2: Analysis workflow for predicting cross-resistance.

This analytical workflow, as applied in the AMP study, shows how compounds cluster based on the similarity of their chemical-genetic interaction profiles [11]. AMPs within the same cluster (e.g., C1 or C2) show high potential for cross-resistance because they share similar resistance determinants, whereas AMPs from different clusters (e.g., C1 vs. C4) are less likely to exhibit cross-resistance [11]. This visualization helps researchers quickly identify groups of compounds with shared resistance mechanisms, guiding decisions about combination therapies and drug development priorities.

Chemical genetics serves as a powerful discovery engine by providing a systematic framework for elucidating the mechanisms of drug action, resistance, and cross-resistance. The methodology's true strength lies in its ability to survey the entire genetic landscape of an organism in a single experiment, offering a comprehensive view of how small molecules interact with biological systems. The principles and workflows outlined—from library construction and high-throughput phenotyping to advanced computational analysis—provide researchers with a robust toolkit for addressing the pressing challenge of antimicrobial resistance.

The application of chemical genetics to map cross-resistance patterns, as demonstrated with diverse antimicrobial peptides, reveals a critical principle: cross-resistance is not inevitable but is highly specific to shared mechanisms of action. This insight provides a strategic path for designing next-generation therapeutic agents with minimized cross-resistance risks, ultimately extending the utility of our existing antimicrobial arsenal and informing the development of more durable treatment regimens.

The growing crisis of antibiotic resistance has spurred innovative research in chemical genetics, providing unexpected insights for oncology. Studies systematically mapping cross-resistance (XR) and collateral sensitivity (CS)—phenomena where resistance to one drug confers resistance or sensitivity to another—have revealed fundamental principles of drug interactions and resistance evolution [2]. These findings now inform the development of Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) as a novel class of anticancer agents. AMPs, essential components of innate immunity across diverse species, demonstrate selective toxicity toward cancer cells while overcoming traditional chemotherapy resistance mechanisms [12] [13]. This review explores how chemical genetics principles are guiding the translation of AMPs into cancer therapeutics, comparing their performance against conventional treatments through structured experimental data and mechanistic analysis.

Table 1: Fundamental Concepts in Chemical Genetics and AMP Research

| Concept | Definition | Relevance to Cancer Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Resistance (XR) | Resistance to one drug confers resistance to a second, unrelated drug [2]. | Limits efficacy of combination therapies; a challenge for conventional chemotherapy. |

| Collateral Sensitivity (CS) | Resistance to one drug confers heightened sensitivity to a second drug [2]. | Informs strategic drug cycling or combination therapies to suppress resistance. |

| Antimicrobial Peptide (AMP) | Naturally occurring, short-chain peptides with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity [12] [13]. | A promising therapeutic class with selectivity for cancer cells and low resistance development. |

| Anticancer Peptide (ACP) | An AMP with demonstrated cytotoxic activity against cancer cells [12] [14]. | Directly exploits cancer cell membrane properties for selective killing. |

Chemical Genetics: A Framework for Understanding Drug Interactions

Chemical genetics provides a systematic framework for exploring drug interactions by assessing how genome-wide mutations affect susceptibility to pharmaceuticals. A pivotal 2025 study created a predictive model using chemical genetics data from an Escherichia coli single-gene deletion library exposed to 40 antibiotics [2]. By developing the Outlier Concordance–Discordance Metric (OCDM), researchers inferred 404 cases of XR and 267 of CS, expanding known interactions more than threefold and validating 64 of 70 predicted interactions experimentally [2]. This demonstrated that a single drug pair can exhibit XR or CS depending on the specific resistance mechanism, highlighting the complex landscape of resistance networks.

The methodology and application of this approach are summarized below.

Diagram 1: Chemical genetics workflow for mapping cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity.

Experimental Protocol for XR/CS Mapping

- Step 1: Library Preparation. Utilize a genome-wide single-gene deletion mutant library, such as the E. coli Keio collection [2].

- Step 2: Chemical Genetic Screening. Expose the mutant library to a panel of drugs (e.g., 40 antibiotics). Quantify fitness defects using a metric like the s-score, which compares a mutant's fitness in a condition to its fitness across all conditions [2].

- Step 3: Profile Comparison. Calculate similarity metrics between the chemical genetic profiles of all drug pairs. The OCDM metric prioritizes signals from extreme s-scores (both positive and negative) to distinguish XR (high profile concordance) from CS (high profile discordance) [2].

- Step 4: Validation. Experimentally evolve resistance to a first drug in multiple lineages. Then, measure the susceptibility (e.g., Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) of these evolved populations to a second drug to confirm predicted XR or CS interactions [2].

Antimicrobial Peptides as Promising Anticancer Agents

AMPs are short (10-50 amino acids), cationic, and amphipathic peptides that are a cornerstone of innate immunity [13] [15]. Their transition from antimicrobial to anticancer agents stems from their ability to selectively target cancer cells with a low propensity for inducing resistance—addressing two major limitations of conventional chemotherapy [12] [16].

Key Structural Classes and Mechanisms of Action

The anticancer activity of AMPs, often termed ACPs, is heavily influenced by their physicochemical properties and secondary structures [12] [14]. The primary mechanism for their selectivity is the electrostatic interaction between the positively charged ACPs and the negatively charged components abundant on cancer cell membranes, such as phosphatidylserine, O-glycosylated mucins, and sialylated gangliosides [16].

Table 2: Structural Classes and Anticancer Mechanisms of Select AMPs/ACPs

| ACPs Name | Structure | Source | Cancer Type/Cell Line Tested | Proposed Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magainin 2 | α-helical | African clawed frog | Bladder, Breast [12] | Membrane disruption [16] |

| Buforin IIb | α-helical | Asian toad | Leukemia, Breast, Lung [12] | Membrane translocation; targets intracellular components [12] |

| Human neutrophil peptide (HNP-1) | β-pleated sheet | Human | Prostate cancer [12] | Membrane disruption; apoptosis [12] |

| Bovine lactoferricin (LfcinB) | β-pleated sheet | Bovine milk | Stomach cancer [12] | Membrane disruption; induction of apoptosis [14] |

| LL-37 | α-helical | Human (Neutrophils) | Colorectal cancer [12] | Membrane disruption; immunomodulation [15] |

| WK-13-3D | Not specified | Synthetic/Antimicrobial | Triple-negative breast cancer [17] | Binds BiP protein; induces ER stress, apoptosis, and autophagy [17] |

The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms by which cationic AMPs (CAMPs) target and kill cancer cells.

Diagram 2: Mechanisms of anticancer action for cationic antimicrobial peptides.

Comparative Efficacy: ACPs vs. Conventional Chemotherapy

The therapeutic potential of ACPs is most evident when directly compared with conventional cancer treatments. ACPs offer a distinct set of advantages rooted in their unique mechanisms of action.

Table 3: Performance Comparison: ACPs vs. Conventional Chemotherapy

| Feature | Anticancer Peptides (ACPs) | Conventional Chemotherapy |

|---|---|---|

| Selectivity | High. Selective for negatively charged cancer cell membranes [13] [14]. | Low. Targets all rapidly dividing cells, healthy and cancerous [16]. |

| Mechanism of Action | Multiple: Membrane disruption, apoptosis induction, immunomodulation [13] [15]. | Typically single-target (e.g., DNA damage, antimetabolites) [16]. |

| Risk of Resistance | Low. Targets the hard-to-alter membrane structure; short interaction time [14] [15]. | High. Common through drug efflux, target alteration, and DNA repair [16]. |

| Spectrum of Activity | Broad-spectrum activity against various cancer types [12] [13]. | Often specific to cancer types or molecular subtypes. |

| Immunogenicity | Low antigenicity; some are immunomodulatory [13] [16]. | Can be immunogenic or immunosuppressive. |

| Primary Toxicity Concerns | Hemolytic activity at high concentrations; can be engineered for reduced toxicity [14]. | Severe side effects (myelosuppression, mucositis, alopecia) are common [16]. |

Illustrative Experimental Data

Preclinical studies provide quantitative evidence for ACP efficacy. For instance:

- Dermaseptin B2 (from Phyllomedusa frog) showed potent activity against prostate cancer cells (PC3, DU145, LnCap) with dosages ranging from 0.71 to 2.65 μM [12].

- Brevenin-2R (from frog skin) exhibited cytotoxic effects on breast cancer (MCF-7), T-cell leukemia (Jurkat), and B-cell lymphoma (BJAB) cells at concentrations of 10-40 μg/ml [12].

- In a specific study on triple-negative breast cancer, the peptide WK-13-3D was shown to promote apoptosis, autophagy, and ubiquitination by binding to the immunoglobulin protein (BiP), demonstrating a specific intracellular target [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Advancing AMP research from bench to bedside relies on a specific toolkit of reagents, computational resources, and experimental methodologies.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AMP/ACP Investigation

| Tool / Reagent | Function/Description | Example Use in AMP Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cationic, Amphipathic Peptides | The core therapeutic agent; typically +2 to +9 net charge, 50% hydrophobicity [14]. | Serve as lead compounds for testing against cancer cell lines. Can be natural or synthetically modified. |

| Database of Antimicrobial Activity and Structure of Peptides (DBAASP) | Public database cataloging over 15,700 peptides with structural and activity data [18]. | Source for identifying novel ACP candidates and analyzing structure-activity relationships (SAR). |

| Cancer Cell Line Panel | A diverse set of validated cancer cell lines (e.g., from ATCC). | For in vitro screening of ACP cytotoxicity and selectivity (e.g., MCF-7, PC-3, Jurkat) [12]. |

| Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion / Broth Microdilution | Standard phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility tests [19]. | Used in parallel to confirm and quantify the retained antimicrobial activity of ACPs [19]. |

| 3D Tumor Spheroids | Multicellular aggregates that better mimic the in vivo tumor microenvironment than 2D cultures. | For advanced in vitro testing of ACP penetration and efficacy in a more physiologically relevant model. |

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) Models | Computational frameworks (e.g., VAEs, LSTMs, GANs) for de novo AMP design and optimization [18]. | To predict and generate new ACP sequences with desired properties (e.g., high efficacy, low toxicity). |

The principles uncovered by chemical genetics—specifically the networks of cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity—provide a powerful lens through which to develop the next generation of oncology therapeutics. Antimicrobial peptides represent a compelling class of agents operating within this framework. Their selective mechanism of action, broad-spectrum activity, and low propensity for resistance position them as promising candidates to address the limitations of conventional chemotherapy [13] [14]. Future research will focus on optimizing their physicochemical properties (charge, hydrophobicity), developing novel delivery strategies (e.g., nano-carriers) to improve stability and targeting, and exploring synergistic combinations with other therapeutics based on CS principles [2] [15]. As these studies progress, AMPs are poised to move from promising experimental compounds to mainstays in the clinical arsenal against cancer.

Chemical-genetic interaction profiling represents a powerful reverse genetics approach that systematically quantifies how genetic perturbations influence cellular susceptibility to chemical compounds [10]. This methodology involves screening comprehensive mutant libraries—including single-gene deletions, hypomorphs (partially depleted essential genes), or gene overexpression collections—against diverse chemical compounds to generate fitness profiles that reveal functional relationships between genes and small molecules [10] [20]. The resulting interaction profiles capture two fundamental relationships: concordance, where similar fitness responses across mutants indicate shared mechanisms of action or resistance pathways; and discordance, where opposing fitness responses reveal collateral sensitivity or functionally distinct pathways [2] [21].

In the context of antibiotic discovery and resistance research, these profiles provide critical insights into cross-resistance patterns—a phenomenon where resistance to one drug confers resistance to another—and collateral sensitivity, where resistance to one drug increases sensitivity to another [2]. The systematic mapping of these relationships through chemical-genetic approaches has expanded our understanding of antibiotic interactions substantially, revealing 404 cases of cross-resistance and 267 cases of collateral sensitivity in Escherichia coli alone, representing a threefold and sixfold expansion respectively over previously known interactions [2] [21]. This review examines the methodological frameworks, interpretive principles, and practical applications of concordance and discordance analysis in chemical-genetic interaction profiling, with particular emphasis on implications for antimicrobial drug development.

Methodological Frameworks for Profile Generation

Experimental Platforms and Genetic Libraries

Chemical-genetic interaction profiling relies on specialized experimental platforms that enable high-throughput screening of mutant libraries under chemical treatment conditions. The PROSPECT (PRimary screening Of Strains to Prioritize Expanded Chemistry and Targets) platform represents one such system developed specifically for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which utilizes a pooled collection of hypomorphic mutants depleted of different essential proteins [22]. Each mutant strain contains a unique DNA barcode that enables quantification via next-generation sequencing, allowing parallel assessment of mutant abundance changes in response to compound exposure [22]. Similarly, in E. coli studies, genome-wide single-gene deletion libraries or comprehensive gene overexpression collections are employed to systematically map resistance determinants [2] [20].

These platforms share common technical approaches: (1) pooled mutant libraries grown in competitive culture with and without compound treatment; (2) barcode sequencing to quantify relative fitness of each strain; (3) calculation of fitness scores representing chemical-genetic interactions; and (4) comparative analysis to identify patterns of concordance and discordance [22] [20]. For essential genes that cannot be deleted, hypomorphs with titratable depletion or CRISPRi knockdown libraries are utilized to capture their contribution to chemical susceptibility [22] [10]. The resulting data matrices, comprising fitness scores for each mutant under each condition, form the basis for subsequent concordance and discordance analysis.

Quantitative Metrics and Scoring Systems

The quantitative analysis of chemical-genetic interactions employs specialized scoring systems to represent mutant fitness under chemical treatment. In the PROSPECT platform, chemical-genetic interaction (CGI) profiles are represented as vectors of hypomorph responses, with significant negative scores indicating hypersensitivity and positive scores indicating resistance [22]. In E. coli studies, s-scores typically represent standardized fitness measurements comparing growth in treated versus untreated conditions, with extreme scores (both positive and negative) indicating significant interactions [2].

For cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity mapping, the Outlier Concordance-Discordance Metric (OCDM) has been developed specifically to distinguish between these interaction types [2] [21]. This metric utilizes six features derived from extreme s-scores: the sum and count of positive concordant s-scores, negative concordant s-scores, and total discordant s-scores [2]. The OCDM prioritizes concordance signals when defining cross-resistance relationships, while requiring both high discordance and minimal concordance for collateral sensitivity assignments [2]. This approach achieved 91% validation accuracy when tested against experimentally evolved resistant strains [2].

Table 1: Key Chemical-Genetic Screening Platforms and Their Applications

| Platform/Organism | Library Type | Primary Readout | Key Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROSPECT (M. tuberculosis) | 600 hypomorphic essential gene mutants | DNA barcode sequencing | MOA prediction, hit prioritization | [22] |

| E. coli chemical genetics | Single-gene deletion library | S-scores from pooled growth | Cross-resistance mapping, collateral sensitivity | [2] [21] |

| E. coli overexpression | Genome-wide ORF overexpression | Fold-change in plasmid abundance | Resistance gene identification, latent resistome | [20] [11] |

| Yeast chemical genetics | Heterozygous deletion library | HIP/HOP profiling | Target identification, mechanism of action | [10] |

Analytical Approaches for Concordance/Discordance Assessment

Reference-Based Profiling and Machine Learning Classification

Reference-based profiling approaches enable mechanism of action prediction by comparing unknown compounds to curated sets with annotated targets. The Perturbagen Class (PCL) analysis method exemplifies this strategy, utilizing a reference set of 437 compounds with known mechanisms of action to infer MOA for novel compounds based on profile similarity [22]. In leave-one-out cross-validation, this approach achieved 70% sensitivity and 75% precision in MOA prediction, with comparable performance (69% sensitivity, 87% precision) when applied to a test set of 75 antitubercular compounds from GlaxoSmithKline [22].

Machine learning classifiers significantly enhance the discrimination between cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity interactions. Decision tree models trained on extreme s-score features (sum and count of positive concordant, negative concordant, and discordant s-scores) achieve F1 scores, recall, precision, and ROC AUC values exceeding 0.7 [2]. These models identify the sum and count of concordant negative s-scores as the most informative features, followed by the sum of discordant s-scores [2]. The performance of these classifiers demonstrates the predictive power of chemical-genetic profiles for anticipating resistance outcomes before extensive experimental evolution is required.

Profile Similarity Metrics and Clustering Algorithms

Similarity assessment between chemical-genetic profiles employs correlation-based metrics and clustering algorithms to group compounds with shared mechanisms. Correlation coefficients between replicate measurements typically exceed r = 0.63, indicating sufficient reproducibility for comparative analysis [20]. For antimicrobial peptides, clustering based on chemical-genetic interaction profiles reveals four distinct groups (C1-C4) that correspond with membrane-targeting versus intracellular-targeting mechanisms and reflect underlying physicochemical properties [20] [11].

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual relationship between profile similarity and drug interaction outcomes:

Diagram 1: Interpretation of profile similarity. High concordance indicates cross-resistance, while high discordance indicates collateral sensitivity. Neutral profiles show neither pattern.

Unsupervised clustering of chemical-genetic profiles enables mechanism of action prediction without pre-defined reference sets. In one comprehensive study of 15 antimicrobial peptides, clustering based on overexpression profiles grouped AMPs according to their membrane-targeting versus intracellular-targeting mechanisms, with distinct physicochemical properties characterizing each cluster [20]. Membrane-targeting AMPs exhibited lower isoelectric points, reduced proline content, and increased hydrophobicity, while intracellular-targeting AMPs showed higher structural disorder propensity [20]. These clustering approaches provide orthogonal validation of mechanism-based groupings and can reveal unexpected relationships between compounds.

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Chemical-Genetic Prediction Methods

| Prediction Method | Application Context | Sensitivity | Precision | Validation Approach | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL Analysis | MOA prediction in M. tuberculosis | 70% | 75% | Leave-one-out cross-validation | [22] |

| PCL Analysis | GSK compound set MOA prediction | 69% | 87% | Test set with known MOA | [22] |

| OCDM Metric | Cross-resistance prediction in E. coli | 73% (AUC) | N/A | Experimental evolution (91% validation) | [2] [21] |

| OCDM Metric | Collateral sensitivity prediction | 76% (AUC) | N/A | Experimental evolution (91% validation) | [2] [21] |

Experimental Validation of Profile-Based Predictions

Genetic and Phenotypic Validation Approaches

Experimental validation of predictions derived from chemical-genetic profiles employs both genetic and phenotypic approaches. For compounds predicted to target specific pathways, resistance mutation induction provides compelling validation; for instance, compounds predicted to target QcrB (a subunit of the cytochrome bcc-aa3 complex) in M. tuberculosis were validated by demonstrating reduced activity against strains carrying known qcrB resistance alleles [22]. Similarly, hypersensitization tests using mutants lacking alternative pathways (such as cytochrome bd deletion mutants in the case of QcrB inhibitors) provide orthogonal confirmation [22].

Phenotypic validation includes minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination against engineered strains and wild-type controls. For AMP resistance predictions, MIC comparisons between wild-type and resistant strains evolved in the laboratory confirmed that cross-resistance occurs primarily between AMPs with similar modes of action [20] [11]. In this validation, 83% of tested chemical-genetic interactions showed MIC changes in the expected direction, with resistance-enhancing gene overexpression increasing MIC ~1.6-fold and sensitivity-enhancing overexpression decreasing MIC ~0.7-fold on average [20].

Application in Combination Therapy Design

Chemical-genetic interaction profiling directly informs combination therapy design by identifying drug pairs with collateral sensitivity relationships that can suppress resistance emergence. When collateral-sensitive drug pairs are applied in combination, they significantly reduce resistance development compared to single-drug treatments [2]. This approach leverages the fundamental principle that resistance mechanisms conferring protection against one drug create vulnerabilities to another, creating evolutionary constraints that limit adaptation.

The experimental workflow below illustrates how chemical-genetic data informs combination therapy design:

Diagram 2: From chemical-genetic profiling to combination therapy. Profile similarity analysis identifies collateral sensitivity and cross-resistance patterns, informing combination therapy design that limits resistance emergence.

Systematic mapping of collateral sensitivity networks has revealed that certain antibiotic classes exhibit particularly extensive collateral sensitivity interactions, making them promising candidates for combination regimens [2]. Conversely, antibiotics with extensive cross-resistance networks can be identified for segregated use to prevent multi-drug resistance emergence. This empirical approach to combination design complements traditional synergy screening by incorporating evolutionary trajectories into therapeutic planning.

Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical-Genetic Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling

| Reagent/Library Type | Key Examples | Primary Applications | Technical Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypomorphic mutant libraries | M. tuberculosis PROSPECT library (600 essential gene hypomorphs) | MOA identification, compound sensitization | Titratable protein depletion; barcoded for pooled screening | [22] |

| Single-gene deletion libraries | E. coli Keio collection | Resistance gene identification, fitness defect profiling | Covers non-essential genes; arrayed or pooled formats | [2] [10] |

| Gene overexpression libraries | E. coli ASKA collection | Resistance gene discovery, target identification | Genome-wide ORF overexpression; latent resistome mapping | [20] [11] |

| CRISPRi essential gene libraries | M. tuberculosis CRISPRIi library | Essential gene knockdown, target validation | Tunable gene suppression; complex maintenance | [10] |

| Barcoded mutant pools | Pooled yeast deletion collection | Fitness profiling, chemical-genetic interactions | Deep sequencing readout; high parallelism | [10] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

Chemical-genetic interaction profiling has established itself as an indispensable methodology for elucidating compound mechanism of action, predicting resistance relationships, and guiding therapeutic combinations. The systematic interpretation of concordance and discordance patterns within these profiles provides a powerful framework for anticipating cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity before they emerge in clinical settings. As chemical-genetic data sets expand across diverse pathogens and compound libraries, their predictive power will continue to increase.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on integrating chemical-genetic data with other functional genomics approaches, including metabolomic and transcriptomic profiling, to create multi-dimensional views of compound mechanism. Additionally, machine learning approaches trained on these integrated data sets may further enhance prediction accuracy for both mechanism of action and resistance outcomes. The application of these methods to complex clinical isolates, rather than laboratory reference strains, represents another critical frontier for translating these approaches to therapeutic development.

As antibiotic resistance continues to threaten global health, chemical-genetic interaction profiling offers a rational path forward for designing combination therapies that proactively manage resistance evolution. By leveraging the fundamental principles of concordance and discordance, researchers can strategically deploy antimicrobial agents to create evolutionary traps that suppress resistance development, extending the clinical lifespan of existing antibiotics and guiding the development of new agents with optimal resistance properties.

From Data to Insights: Methodological Advances and Predictive Modeling in Chemical Genetics

High-throughput profiling of genome-wide mutant libraries is a cornerstone of modern functional genomics, enabling the systematic identification of genes essential for specific biological functions or phenotypes. Within chemical genetics research, these screens are indispensable for deciphering complex cross-resistance patterns—the phenomenon where resistance to one compound confers resistance or hypersensitivity to another. Understanding these patterns is crucial for drug development, as it reveals potential therapeutic synergies, anticipates resistance mechanisms, and uncovers the underlying functional networks within cells.

The field is primarily driven by three powerful technological approaches: chemical mutagenesis, CRISPR-based libraries, and chemical-genetic interaction profiling. Each method offers distinct advantages, limitations, and insights into how genetic perturbations influence phenotypic outcomes and compound resistance. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these platforms, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers in selecting the optimal strategy for their specific screening objectives.

Platform Comparison: Methodologies and Performance Metrics

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and performance data of the three main high-throughput profiling platforms.

Table 1: Comparative overview of high-throughput profiling platforms for genome-wide mutant libraries

| Screening Platform | Mutagenesis Mechanism | Key Readout | Typical Library Size | Mutant Type | Key Advantages | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Mutagenesis [23] | Ethylmethanesulfonate (EMS)-induced single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) | Whole-exome sequencing of resistant clones | ~370 SNVs per clone [23] | Primarily recessive point mutations | Identifies gain-of-function and separation-of-function alleles; defines critical protein domains | Comprehensive identification of suppressor/resistance loci; functional domain mapping |

| CRISPR Libraries [24] | CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout, activation, or repression | Next-generation sequencing of guide RNA (gRNA) abundance | Tens of thousands of single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) [24] | Primarily loss-of-function (gene knockout) | High efficiency, multifunctionality, low background noise, precise targeting | Deciphering key regulators in tumorigenesis, drug resistance mechanisms, immunotherapy optimization |

| Chemical-Genetic Profiling [20] | Overexpression or depletion of ~4,400 E. coli genes | Growth kinetics monitored by deep sequencing of plasmid abundance | ~4,400 gene overexpressions [20] | Altered gene dosage (overexpression/hypomorph) | Maps "latent resistome"; clusters compounds by mode of action; reveals antagonistic interactions | Profiling cross-resistance patterns; mapping antibiotic modes of action; identifying cellular targets |

Performance metrics vary significantly between these platforms. In chemical mutagenesis screens, a proof-of-concept study for 6-thioguanine (6-TG) resistance in haploid mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) successfully identified point mutations in all known suppressor genes, with approximately 11.3% of induced mutations affecting coding sequences in a non-synonymous way [23]. CRISPR screens are characterized by their high efficiency and specificity, though they can be confounded by off-target effects [24]. Chemical-genetic interaction profiling, which measures how gene overexpression influences drug susceptibility, has demonstrated high reproducibility (Pearson correlation r = 0.63 between replicates) and validation rates, with 83% of tested interactions confirming changes in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) as expected [20].

Experimental Protocols for Key Screening Methodologies

Protocol A: Chemical Mutagenesis Screening in Haploid Cells

This protocol, adapted from a study screening for 6-TG resistance, leverages haploid cells to efficiently identify recessive mutations [23].

- Step 1: Library Generation. Treat haploid mammalian cells (e.g., H129-3 mESCs) with a chemical mutagen such as EMS. Titrate the EMS dose to achieve a balance between mutation density and cell viability.

- Step 2: Phenotypic Selection. Subject the mutagenized cell population to selective pressure, such as a cytotoxic drug like 6-TG, over multiple cell doublings to enrich for resistant clones.

- Step 3: Clone Isolation and Sequencing. Isclude individual resistant clones and extract genomic DNA. Perform whole-exome sequencing to identify homozygous single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions/deletions (INDELs).

- Step 4: Candidate Gene Identification. Bioinformatically filter sequencing data to focus on non-synonymous coding mutations. Prioritize genes that are mutated in multiple independent clones and/or carry mutations predicted to be deleterious.

Protocol B: Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling

This protocol maps genes that influence susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) or other compounds through overexpression [20].

- Step 1: Library Preparation. Create a pooled plasmid library designed to overexpress nearly every open reading frame (ORF) in the genome (e.g., ~4,400 for E. coli).

- Step 2: Competitive Growth Assay. Grow the pooled library in the presence of a sub-inhibitory concentration of the AMP (concentration that increases population doubling time by 2-fold) and in an untreated control for approximately 12 generations.

- Step 3: Sequencing and Abundance Quantification. Isolate plasmids from both conditions and use deep sequencing to determine the relative abundance of each overexpression plasmid.

- Step 4: Interaction Score Calculation. For each gene, compute a chemical-genetic interaction score by comparing plasmid abundance in the treated versus untreated pools. Identify "resistance-enhancing" genes (overexpression increases survival) and "sensitivity-enhancing" genes (overexpression decreases survival).

Analysis of Cross-Resistance Patterns in Chemical Genetics

Chemical-genetic interaction profiling is particularly powerful for elucidating cross-resistance patterns. A systematic study of 15 different AMPs in E. coli revealed that cross-resistance is not universal but is highly dependent on the compound's mode of action [20].

The analysis of chemical-genetic interaction profiles led to the clustering of AMPs into distinct groups (C1-C4) based on the similarity of genes that, when overexpressed, altered susceptibility. AMPs within the same cluster, and thus with similar interaction profiles, showed a high degree of cross-resistance. Conversely, AMPs from different clusters, particularly those with membrane-targeting (C1, C2) versus intracellular-targeting (C3, C4) modes of action, showed minimal cross-resistance [20]. This indicates that resistance mechanisms are highly specific to the compound's primary cellular target.

Table 2: Cross-resistance insights from chemical-genetic profiling of 15 antimicrobial peptides (AMPs)

| AMP Cluster | Primary Mode of Action | Key Physicochemical Properties | Cross-Resistance Observation | Implication for Drug Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 & C2 [20] | Membrane disruption/pore-formation | Higher hydrophobicity, lower isoelectric point, high propensity for secondary structure | Prevalent between AMPs within the same cluster | Combining membrane-targeting AMPs may lead to shared resistance |

| C3 & C4 [20] | Intracellular targets (e.g., protein/DNA synthesis) | Lower hydrophobicity, higher proline content | Minimal cross-resistance to membrane-targeting human host-defense peptides | Intracellular-targeting therapeutic AMPs may avoid cross-resistance with innate immunity |

This data provides a strategic framework for selecting combination therapies and designing novel therapeutic AMPs that minimize the risk of cross-resistance to human host-defense peptides, a key consideration for long-term efficacy [20].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful execution of high-throughput profiling screens relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for high-throughput profiling

| Reagent / Tool Name | Provider Examples | Function in Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Exome Capture Panels [25] | BOKE, IDT, Nanodigmbio, Twist Bioscience | Hybridization-based enrichment of genomic exon regions for efficient variant discovery via sequencing. |

| Haploid Mammalian Cells [23] | Various cell repositories | Enable identification of recessive mutations in a single genetic screen, simplifying analysis. |

| CRISPR Library sgRNAs [24] | Commercially available or custom-designed | Target specific genomic loci for knockout, activation, or repression in pooled screens. |

| Pooled ORF Overexpression Libraries [20] | Academic and commercial sources | Systematically modulate gene dosage to identify resistance and sensitivity-enhancing genes. |

| MGIEasy UDB Library Prep Set [25] | MGI | Facilitates high-throughput, automated library construction with unique dual indexing for sample multiplexing. |

| DNBSEQ-T7 Sequencer [25] | MGI | High-throughput sequencing platform providing the read depth required for complex pooled library screens. |

The choice of a high-throughput profiling platform is dictated by the specific biological question. Chemical mutagenesis remains unparalleled for discovering novel resistance loci and generating a spectrum of point mutations that reveal critical functional residues and domains [23]. CRISPR libraries offer a direct, programmable, and highly specific approach for genome-wide loss-of-function studies, making them ideal for systematically probing gene function in disease contexts like cancer [24]. Finally, chemical-genetic interaction profiling provides a unique map of the "latent resistome," powerfully clustering compounds by their mode of action and predicting cross-resistance patterns, which is invaluable for antibiotic development and understanding drug interactions [20].

Integrating data from these complementary approaches provides a more comprehensive understanding of the genetic wiring underlying drug response and resistance, ultimately accelerating the development of robust therapeutic strategies.

The Outlier Concordance–Discordance Metric (OCDM) represents a significant methodological advancement in the analysis of chemical-genetic interactions for predicting antibiotic cross-resistance (XR) and collateral sensitivity (CS). Developed to overcome the limitations of traditional experimental evolution approaches, OCDM provides a computational framework that systematically quantifies how resistance to one antibiotic affects susceptibility to others by leveraging genome-wide mutant fitness data [21].

In the critical challenge of antimicrobial resistance, understanding these relationships is paramount. Cross-resistance occurs when resistance to one drug confers resistance to another, further limiting treatment options. Conversely, collateral sensitivity describes the scenario where resistance to one drug increases sensitivity to another, revealing potential strategies for combination or cycling therapies [21]. Traditional methods for mapping these interactions rely on experimental evolution followed by susceptibility testing, which probes only a limited genetic space and requires extensive resources [21]. OCDM overcomes these limitations by using chemical-genetic profiles to predict interactions computationally before experimental validation.

How OCDM Works: Mechanism and Workflow

Theoretical Foundation

OCDM operates on a fundamental premise derived from chemical genetics: antibiotics with concordant fitness profiles across a genome-wide mutant library likely share resistance mechanisms, predicting cross-resistance. Conversely, antibiotics with discordant fitness profiles suggest that mutations conferring resistance to one drug increase sensitivity to the other, indicating collateral sensitivity [21].

The metric was developed using chemical-genetic interaction data from an Escherichia coli single-gene deletion library screened against 40 different antibiotics. In this data, drug effects on each mutant are represented by s-scores, which quantify a mutant's fitness in a specific condition relative to its fitness across all tested conditions [21]. Rather than using all s-score data, which contains considerable neutral noise, OCDM focuses specifically on extreme s-scores (outliers) that represent the most significant fitness effects [21].

Algorithm and Calculation

The OCDM algorithm utilizes six key features derived from the extreme s-scores in chemical-genetic profiles [21]:

- Sum of positive concordant s-scores

- Count of positive concordant s-scores

- Sum of negative concordant s-scores

- Count of negative concordant s-scores

- Sum of discordant s-scores

- Count of discordant s-scores

Through training decision tree models, researchers identified that the sum and count of concordant negative s-scores were the most informative features for classification, followed by the sum of discordant s-scores [21]. The resulting OCDM metric prioritizes concordance signals when defining interactions, reflecting that cross-resistance-conferring mutations typically dominate over collateral sensitivity effects in heterogeneous populations [21].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between chemical-genetic profiles and the predicted antibiotic interactions:

Experimental Workflow for OCDM Application

The complete workflow for applying OCDM spans from data generation to experimental validation, as shown below:

Performance Comparison with Alternative Methods

OCDM demonstrates distinct advantages over other approaches for identifying cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity patterns. The table below summarizes its performance against alternative methodologies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Antibiotic Interaction Detection Methods

| Method | Primary Approach | Throughput | Genetic Coverage | Mechanistic Insight | Validation Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCDM | Computational analysis of chemical-genetic profiles | High (840 pairs simultaneously) | Comprehensive (whole genome) | Direct from mutant fitness effects | 91% (64/70 validated) [21] |

| Experimental Evolution | Laboratory evolution + susceptibility testing | Low (limited lineages) | Limited (depends on selection pressure) | Indirect (requires sequencing) | Highly variable between studies [21] |

| Correlation-Based Metrics | Correlation of entire chemical-genetic profiles | High | Comprehensive | Limited by noise in neutral phenotypes | Poor (AUC 0.52-0.67) [21] |

| Chemical-Genetic Similarity | Profile similarity to infer mode of action | High | Comprehensive | Indirect inference | Moderate for XR only [11] |

Key Performance Metrics

In direct validation experiments, OCDM demonstrated 91.4% precision (64 out of 70 predicted interactions validated experimentally) [21]. The method significantly expanded the known interaction landscape, increasing known XR interactions by three-fold and CS interactions by six-fold compared to previous literature [21]. This included the reclassification of 116 previously tested drug-pair relationships with higher accuracy than individual experimental evolution studies, which showed considerable inconsistency—from 91 antibiotic pairs tested in at least two studies, only 30% were called uniformly across studies [21].

OCDM outperformed correlation-based metrics, which showed poor discrimination capability with area under the curve (AUC) values of just 0.52-0.67 for receiver operating characteristic curves [21]. The final OCDM model achieved AUC values of 0.76 and 0.73 for discriminating CS and XR from neutral interactions, respectively [21].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

OCDM Generation Protocol

Data Source Preparation:

- Obtain chemical-genetic interaction data from the E. coli single-gene deletion library fitness assays in 40 antibiotics [21].

- Calculate s-scores for each mutant-drug combination, representing standardized fitness effects relative to control conditions [21].

OCDM Calculation:

- Identify extreme s-scores exceeding optimal thresholds determined by performance validation (Extended Data Fig. 1d in source) [21].

- Calculate the six OCDM features from extreme s-score outliers only.

- Apply the OCDM classification thresholds to determine interaction types:

- XR: High concordance despite discordance signal

- CS: High discordance with no concordance signal

- Neutral: Neither significant concordance nor discordance [21]

Network Analysis:

- Construct antibiotic interaction networks from OCDM classifications.

- Analyze monochromaticity (exclusively XR or CS) and conservation within antibiotic classes [21].

Experimental Validation Protocol

Strain Preparation:

- Use wild-type E. coli strains for experimental evolution matching the genetic background of the chemical-genetic library [21].

Evolution Experiments:

- Evolve independent bacterial lineages in increasing concentrations of a primary antibiotic.

- Propagate cultures for sufficient generations (typically 200-500) to allow fixation of resistance mutations [21].

Susceptibility Testing:

- Measure minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of evolved strains against both primary and secondary antibiotics.

- Calculate fold-change in susceptibility compared to ancestral strain.

- Classify interactions based on statistically significant changes:

- XR: Significant increase in MIC for secondary drug

- CS: Significant decrease in MIC for secondary drug

- Neutral: No significant change in MIC [21]

Mechanism Deconvolution:

- Sequence genomes of evolved strains to identify acquired mutations.

- Cross-reference with chemical-genetic profiles to identify causal mutations driving interactions [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for OCDM and Chemical-Genetic Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function in OCDM Research | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli Single-Gene Deletion Library | Genome-wide mutant collection for chemical-genetic profiling | Keio collection or similar; ~4,000 non-essential gene deletions [21] |

| Chemical-Genetic Screening Platform | High-throughput fitness assessment of mutants under drug treatment | 96-well or 384-well format with automated liquid handling [21] |

| Antibiotic Compound Library | Diverse set of antimicrobial agents for profiling | 40+ antibiotics spanning major classes and mechanisms [21] |

| s-Score Calculation Algorithm | Standardizes mutant fitness across conditions | Normalizes fitness to plate controls and across entire experiment [21] |

| OCDM Classification Script | Implements the OCDM algorithm for interaction prediction | R or Python implementation with optimized thresholds [21] |

| Experimental Evolution Setup | Laboratory evolution of resistance for validation | Serial passage in liquid media with escalating drug concentrations [21] |

Applications in Antimicrobial Drug Development

The OCDM framework enables several innovative applications in antibiotic discovery and development:

Rational Combination Therapy: By identifying collateral sensitivity pairs, OCDM informs antibiotic combinations that can suppress resistance emergence. The original study demonstrated that using CS pairs in combination reduced resistance development compared to single-drug treatments [21].

Drug Cycling Strategies: CS interactions revealed by OCDM can design intelligent antibiotic rotation schedules that exploit fitness costs of resistance, potentially reversing resistance evolution in clinical settings [21].

Mechanism Deconvolution: Beyond predicting interactions, OCDM helps identify specific genetic determinants driving cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity by pinpointing which mutants contribute most to concordance or discordance signals [21]. This provides valuable insights into resistance mechanisms that can inform drug design.

The framework revealed that a single drug pair can exhibit both XR and CS depending on the specific resistance mechanism acquired, demonstrating the nuanced understanding possible with OCDM that would be difficult to ascertain through experimental evolution alone [21].

The Outlier Concordance–Discordance Metric represents a powerful computational framework that transforms our approach to mapping antibiotic interactions. By systematically leveraging chemical-genetic profiles, OCDM enables comprehensive, accurate prediction of cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity patterns with minimal experimental burden. Its high validation rate (91% precision) and ability to expand known interaction networks by several-fold demonstrate significant advantages over traditional methods. For researchers and drug development professionals, OCDM provides both a practical tool for identifying promising combination therapies and a conceptual framework for understanding the complex genetic relationships underlying antibiotic resistance.

In the face of diminishing therapeutic options against antimicrobial resistance, understanding the complex relationships between antibiotics has never been more critical. When bacteria develop resistance to one drug, they may inadvertently become resistant to other compounds (cross-resistance, XR) or conversely, more sensitive to others (collateral sensitivity, CS). These interaction patterns represent a pivotal frontier in optimizing antibiotic cycling and combinatorial treatments. Traditional methods for mapping these relationships through experimental evolution are notoriously resource-intensive, probing only a limited fraction of possible resistance mutations and often yielding inconsistent results across studies due to variations in selection pressure and lineage sampling [21].

The emerging paradigm leverages systematic chemical-genetic interaction profiling to predict these relationships by comparing how genome-wide gene perturbations affect susceptibility to different antibiotics. This approach fundamentally shifts the discovery process from laborious serial experimentation to computational prediction, enabling researchers to rapidly identify interaction networks and their underlying genetic mechanisms. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the leading computational frameworks that translate chemical-genetic similarity into predictive models of drug-pair interactions, with particular emphasis on their methodological foundations, performance characteristics, and applicability domains for researchers navigating this rapidly evolving field.

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Approaches

The table below summarizes the core methodologies, strengths, and limitations of the primary approaches for predicting drug-pair interactions from chemical-genetic and other high-dimensional data sources.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Predictive Modeling Approaches for Drug-Pair Interactions

| Method | Core Methodology | Key Performance | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCDM (Outlier Concordance-Discordance Metric) | Uses extreme s-scores from chemical-genetic profiles; prioritizes concordant negative signals for XR, discordance for CS [21] | 91% validation rate (64/70 interactions); ROC AUC=0.76 (CS), 0.73 (XR); 3× more XR and 4× more CS discovered [21] | Direct biological interpretability; identifies driving mutations; validated for antibiotic XR/CS | Limited to organisms with comprehensive mutant libraries |

| MDG-DDI (Multi-feature Drug Graph) | Integrates FCS-based Transformer (semantic) with Deep Graph Network (structural); uses GCN for final prediction [26] | Outperforms 11 baseline models; strong gains with unseen drugs; robust on unbalanced datasets [26] | Handles both semantic and structural features; excellent generalization to new drugs | Complex architecture requires significant computational resources |

| EviDTI (Evidential Deep Learning) | Incorporates evidential deep learning for uncertainty quantification; uses 2D/3D drug structures and protein sequences [27] | Competitive on DrugBank (82.02% accuracy), Davis, KIBA; well-calibrated uncertainty estimates [27] | Quantifies prediction confidence; reduces false positives in experimental validation | Requires integration of multiple data modalities |

| MDFLDRR (Multi-Drug Features Learning) | Maps pathway, enzyme, target, and substructure features to common interaction space; uses drug relation regularization [28] | Pronounced predictive advantage for cardiovascular-antidepressant DDIs; accurately identifies severity levels [28] | Specifically designed for clinically relevant drug pairs; incorporates interaction severity | Application primarily demonstrated on specific drug classes |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Chemical-Genetic Profiling for Cross-Resistance Prediction

The foundational protocol for generating chemical-genetic interaction data involves systematic screening of genome-wide mutant libraries against compound panels:

Experimental Workflow:

- Library Preparation: Utilize the Escherichia coli single-gene deletion library (Keio collection) or overexpression library for essential genes [21] [11].

- Competitive Growth Assay: Grow pooled mutant libraries in presence of sub-inhibitory antibiotic concentrations (typically concentrations that double doubling time) for approximately 12 generations [11].

- Fitness Quantification: Sequence plasmid pools or mutant barcodes to determine relative abundance changes versus untreated controls.

- Score Calculation: Compute s-scores or fold-change values that represent each mutant's sensitivity/resistance to each compound [21] [11].

Computational Analysis:

- Profile Comparison: Calculate similarity metrics between antibiotic profiles using the OCDM, which emphasizes extreme s-scores (both positive and negative) [21].

- Interaction Classification: Apply thresholds to identify XR (high concordance) versus CS (high discordance with minimal concordance) [21].

- Mechanism Identification: Identify specific gene mutations driving the interactions through enrichment analysis of sensitivity/resistance patterns.

Diagram 1: Chemical-genetic prediction workflow

Deep Learning Framework for DDI Prediction

Modern deep learning approaches employ multi-modal data integration:

Data Preparation:

- Drug Representation:

- Protein Representation:

- Amino acid sequences encoded via pre-trained models (e.g., ProtTrans) [27]

- Interaction Labels:

Model Architecture (MDG-DDI):

- Drug Encoder: Combines Frequent Consecutive Subsequence (FCS)-based Transformer for semantic features with Deep Graph Network for structural features [26].

- Feature Fusion: Concatenates drug and target representations for input to Graph Convolutional Network [26].

- Interaction Prediction: Outputs probability scores for potential interactions, with specialized handling for cold-start scenarios (unseen drugs) [26].

Diagram 2: Deep learning DDI prediction