Chemical Genetics: Basic Concepts, Methodologies, and Applications in Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemical genetics, a research approach that uses small molecules as probes to study gene and protein functions in biological systems.

Chemical Genetics: Basic Concepts, Methodologies, and Applications in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemical genetics, a research approach that uses small molecules as probes to study gene and protein functions in biological systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of forward and reverse chemical genetics, detailing modern methodological applications such as high-throughput screening and target identification. The content further addresses key challenges in the field, including specificity and efficacy optimization, and validates the approach through comparative analysis with classical genetics. By synthesizing current research and real-world case studies, this article serves as a vital resource for understanding how chemical genetics is propelling therapeutic discovery and shaping the future of biomedical research.

What is Chemical Genetics? Defining the Core Principles and Evolutionary Journey

Chemical genetics is an investigative approach that uses small molecules as probes to disrupt or modulate protein function and signal transduction pathways within cells, enabling the systematic study of biological systems [1]. Analogous to classical genetic screens, which introduce random mutations to observe phenotypic consequences, chemical genetics employs libraries of small molecules to perturb cellular phenotypes. The subsequent observation of these phenotypes allows researchers to deduce the function of the targeted proteins or pathways [1]. This methodology serves as a powerful, unifying bridge between the disciplines of chemistry and biology, facilitating the discovery of novel drug targets and the validation of these targets in experimental models of human disease [1].

The field is broadly categorized into two complementary approaches, forward and reverse chemical genetics, which differ in their starting points and objectives. In forward chemical genetics (also known as phenotypic screening), researchers screen diverse small molecule libraries against cells or whole organisms to identify compounds that induce a specific phenotype of interest. The subsequent challenge is to identify the compound's macromolecular target, a process often referred to as target deconvolution [1] [2]. Conversely, reverse chemical genetics begins with a known, purified protein target of interest. Small molecules are screened for their ability to interact with and modulate the activity of this target. The active compounds are then used as probes to investigate the target's biological function within a cellular or organismal context [1].

A principal advantage of chemical genetics over traditional genetic methods is the temporal control it offers. Small molecule probes can be added or removed at specific times, allowing for reversible, acute perturbations of protein function. This is in contrast to genetic mutations, which are typically permanent and can trigger complex compensatory mechanisms within the cellular network [2]. This temporal precision is particularly valuable in neuroscience, for example, where it can be used to study developmental processes or the acute effects of modulating neuronal signaling [2].

Table 1: Core Concepts in Chemical Genetics

| Concept | Description | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Probe | A synthetic or natural compound that binds to and modulates the function of a specific protein or pathway. [2] | Used to investigate the biological role of its target in cells or organisms. |

| Chemical-Genetic Interaction | A quantitative measure of how a genetic mutation alters a cell's sensitivity to a small molecule. [3] | Reveals functional relationships between genes and compounds, and a drug's Mode of Action (MoA). |

| Haploinsufficiency Profiling (HIP) | A screen using heterozygous deletion mutants to identify drug targets; reduced gene dosage increases sensitivity. [3] | Identifying cellular targets of small molecules in diploid organisms like yeast. |

| Guilt-by-Association | Comparing the fitness profiles (signatures) of different drugs to identify those with similar MoA. [3] | Classifying novel compounds based on their similarity to drugs with known mechanisms. |

Key Methodologies and Workflows

The execution of a successful chemical genetics screen relies on a structured workflow encompassing library design, assay development, and hit validation. The initial step involves the selection or synthesis of a appropriate small molecule library. Two primary strategies exist for library construction: focused library synthesis and diversity-oriented synthesis [2]. Focused libraries are designed around known molecular scaffolds, often targeting specific protein families (e.g., kinases), and represent a lower-risk strategy for finding active compounds. In contrast, diversity-oriented synthesis aims to generate maximal structural variety using novel scaffolds, thereby increasing the potential to modulate a wider array of biological targets in phenotypic screens [2].

A critical component of modern, high-throughput chemical genetics is the use of systematic mutant libraries. These are genome-wide collections of microbial or mammalian cell mutants, which can be arrayed (each mutant in a separate well) or pooled (all mutants grown together) [3]. Pooled libraries, in particular, have been revolutionized by barcoding strategies. Each mutant strain is tagged with a unique DNA barcode, allowing its relative abundance in a pooled culture to be quantified via high-throughput sequencing. This enables the parallel measurement of fitness for thousands of mutants in a single experiment under different compound treatment conditions [3] [4].

The development of a robust, high-throughput biological assay is paramount. These assays must be optimized for a microplate format (96-well or 384-well) and provide a strong signal-to-noise ratio. A common metric for assessing assay quality is the Z-factor, a statistical parameter that quantifies the separation between positive and negative controls [2]. Assays can range from in vitro enzymatic activity measurements to complex cell-based phenotyping. In neurobiology, for instance, high-content screening using automated microscopy is employed to quantify morphological changes such as neurite outgrowth or synapse formation [2]. For even greater biological relevance, small molecules can be screened in more complex models, including tissue explants, zebrafish, or Xenopus embryos, which provide a holistic context for studying developmental processes and disease mechanisms [1] [2].

Following the primary screen, identified "hit" compounds must undergo rigorous validation. Target identification is a crucial and often challenging step in forward chemical genetics. A widely used method is affinity chromatography, where a derivative of the small molecule hit is tethered to a solid-phase resin and used to "pull down" its binding partners from a cellular lysate [2]. Modern approaches also leverage genetic tools, such as CRISPR-based knockdown libraries for essential genes, to identify drug targets by observing which genetic sensitizations mimic or enhance the compound's effect [3]. Furthermore, the mechanism of action for a novel compound can be inferred by comparing its chemical-genetic interaction profile—the full set of genetic sensitivities and resistances it causes—to those of compounds with known targets, a powerful "guilt-by-association" approach [3].

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

Protocol for Pooled Chemical-Genetic Interaction Screening

This protocol outlines the key steps for performing a high-throughput chemical-genetic interaction screen using a pooled, barcoded yeast deletion library, a foundational method in the field [4].

- Library Preparation and Inoculation: Begin with a frozen stock of the pooled Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene deletion library, where each non-essential gene knockout strain carries unique molecular barcodes (UPTAG and DOWNTAG). Inoculate the entire library into a suitable liquid growth medium and culture under standard conditions to mid-log phase.

- Compound Treatment and Control Setup: Divide the culture into two fractions. One fraction is treated with the sub-lethal concentration of the small molecule compound of interest (the "test condition"), while the other is grown in an equivalent amount of solvent vehicle (e.g., DMSO) as the "control condition." The concentration used should be sufficient to induce a mild fitness defect, typically determined by a prior dose-response curve.

- Growth and Harvesting: Allow both the test and control cultures to grow for a predetermined number of generations (typically 5-20). It is critical to maintain the cultures in mid-log phase by diluting them periodically to prevent nutrient depletion and stationary phase entry. Harvest cell pellets from both conditions by centrifugation.

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Barcode Amplification: Isolate genomic DNA from the cell pellets. Use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with a set of common primers to specifically amplify the pooled barcode sequences from the genomic DNA of both the test and control samples.

- Sequencing Library Preparation and Sequencing: Incorporate next-generation sequencing adapters and sample indices (multiplexing barcodes) into the amplified barcode pools. This allows multiple samples to be pooled and sequenced in a single run. The final sequencing libraries are quantified, normalized, and loaded onto a high-throughput sequencer.

- Computational Analysis with BEAN-counter: Process the raw sequencing data using the BEAN-counter (Barcoded Experiment Analysis for Next-generation sequencing) software pipeline [4]. The pipeline performs the following:

- Barcode Demultiplexing: Assigns sequences to the correct sample based on their multiplexing barcodes.

- Barcode Clustering and Counting: Maps the sequenced barcodes to the reference library to identify each strain and count its frequency in the test and control samples.

- Fitness Calculation: Calculates a normalized fitness score for each mutant strain in the presence of the compound relative to the control condition.

- Interaction Scoring: Identifies chemical-genetic interactions by evaluating the statistical significance of the fitness defects (sensitivities) or fitness advantages (resistances) observed in the test condition.

Quantitative Analysis of Genetic Interactions

The quantitative data generated from these screens are analyzed to generate chemical-genetic interaction scores. These scores represent the deviation of the observed mutant fitness in the drug from the expected fitness, often based on a multiplicative model [4]. A negative score indicates a synergistic interaction (the mutation makes the cell more sensitive to the drug), while a positive score indicates an antagonistic interaction (the mutation confers resistance). The resulting dataset is a matrix of interaction scores for every gene-compound pair tested.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools in Chemical Genetics

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Barcoded Deletion Library | A pooled collection of mutants, each with a unique DNA barcode, enabling fitness profiling via sequencing. [3] [4] |

| CRISPRi/a Libraries | Pooled libraries for knockdown (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) of genes, especially useful for essential genes in haploid cells. [3] |

| BEAN-counter Pipeline | A specialized bioinformatics software for analyzing barcode sequencing data to calculate fitness and interaction scores. [4] |

| Affinity Chromatography Resin | A solid-phase matrix with an immobilized small molecule used to isolate and identify protein targets from cell lysates. [2] |

| Focused Compound Library | A collection of small molecules designed around specific chemical scaffolds, often targeting related proteins. [2] |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Basic Research

Chemical-genetic approaches have become indispensable in both basic research and the drug discovery pipeline, providing unprecedented insights into the inner workings of cells and the action of pharmacologic agents.

A primary application is the identification of a drug's Mode of Action (MoA). By screening a compound of unknown function against a genome-wide mutant library, researchers can observe which genetic perturbations enhance or suppress the drug's effect. If hypersensitivity is observed when a specific pathway is compromised, it often indicates that the drug target is part of that pathway or a parallel one that becomes essential when the first is damaged [3]. For essential genes, which are common drug targets, hypomorphic alleles (e.g., CRISPRi knockdowns) or heterozygous deletion libraries (in diploids) are used. Increased sensitivity upon reduced expression of the target gene (haploinsufficiency) is a strong indicator of direct target engagement [3].

Furthermore, chemical genetics excels at dissecting drug resistance, uptake, and efflux mechanisms. Genes whose loss makes the cell resistant to a drug often encode the drug's direct target or components of a pathway required for its cytotoxic activity. Conversely, genes whose loss causes hypersensitivity may encode efflux pumps that expel the drug or enzymes involved in detoxification pathways [3]. This systematic profiling reveals the full landscape of intrinsic cellular resistance.

Another powerful application is the prediction of drug-drug interactions. By comparing the chemical-genetic interaction profiles of two drugs, one can predict their combined effect. Drugs with highly similar profiles are likely to act on the same pathway and may display antagonism, while drugs with distinct but functionally related profiles may exhibit synergy [3]. Machine learning algorithms, such as Naïve Bayesian and Random Forest classifiers, are now being trained on these large-scale chemical-genetic datasets to computationally predict the outcome of drug combinations, guiding effective combination therapies [3].

The conceptual framework of chemical genetics, which uses small molecules to interrogate biological systems, is deeply rooted in the receptor theory pioneered by Paul Ehrlich in the late 19th century. Ehrlich's foundational work on immunity and chemotherapy led him to postulate that interactions between drugs, toxins, and cells were not vague phenomena but were governed by specific chemical structures. His side-chain theory (Seitenkettentheorie), first fully articulated in 1900, proposed that cells possess specific "side chains" (or receptors) on their surfaces that could bind to toxins with precise molecular complementarity, much like a "lock and key" [5]. He further theorized that binding could stimulate the cell to overproduce and shed these receptors into the bloodstream, which we now recognize as antibodies [5]. This revolutionary idea—that biological specificity arises from structured molecular interactions—established the fundamental premise that a small molecule can be used as a "magic bullet" to selectively target a single biological component within a complex living system [5].

This principle directly informs the core of modern chemical genetics. Today, the field is defined as "the use of small molecule compounds to perturb a biological system to explore the outcome" [6] and "the use of biologically active small molecules (chemical probes) to investigate the functions of gene products, through the modulation of protein activity" [7]. It is divided into two complementary approaches: forward chemical genetics, which starts with a phenotypic screen of a small molecule library to identify a biological effect and then works to identify the molecular target (the "deconvolution" problem Ehrlich would have recognized), and reverse chemical genetics, which begins with a specific protein or gene of interest and seeks a small molecule to modulate its function [8] [7]. This guide will explore how Ehrlich's core premise has evolved into a sophisticated toolkit for basic research and drug discovery.

The Evolution from Theoretical Concept to Research Discipline

Core Principles and Definitions

The journey from Ehrlich's postulates to a defined research discipline took nearly a century, maturing with the advances in genomics and proteomics. The key principles that define chemical genetics as a distinct field include:

- Use of Small Molecules as Probes: Small molecules are used to alter protein function transiently and reversibly, allowing for the exploration of biological roles in a manner that can overcome limitations of genetic approaches like lethality or redundancy [7].

- Forward and Reverse Approaches: As outlined above, this dichotomy mirrors classical genetic screening, but uses chemical libraries instead of mutations [8].

- Bridging Phenotype and Target: Chemical genetics serves as a "tight linker between library screening and genomic manipulations," providing powerful strategies to unravel biological pathways and identify drug targets [8].

The Differentiating Power of Small Molecules

While genetic manipulations (e.g., CRISPR, RNAi) are powerful, chemical genetics offers unique advantages rooted in Ehrlich's initial insights into specificity and temporal control. Table 1 below contrasts these approaches.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Chemical Genetics over Pure Genetic Approaches

| Feature | Chemical Genetics (Small Molecules) | Classical Genetic Manipulation |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Control | Rapid, transient, and reversible modulation of protein activity [8] | Permanent or long-lasting; protein recovery depends on new synthesis |

| Dose Dependency | Enables titratable control over protein function | Typically an all-or-nothing effect (knockout/knockdown) |

| Functional Targeting | Can inhibit one specific function of a multi-functional protein (e.g., scaffold vs. enzymatic) [8] | Removes the entire protein and all its functions |

| Systemic Compensation | Minimal activation of compensatory mechanisms due to acute intervention | Chronic loss can trigger adaptive pathways and redundant mechanisms [8] |

| Applicability | Can be applied to primary cells and complex systems where genetic editing is difficult [8] | Editing efficiency can be highly variable, especially in primary cells [8] |

The Modern Toolkit: Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The realization of Ehrlich's premise relies on a modern toolkit of experimental methodologies. The following workflow diagram outlines the two main branches of chemical genetics research.

The Central Challenge: Target Deconvolution

In forward chemical genetics, the central challenge—identifying the molecular target of a bioactive compound—is a process known as target deconvolution. This is the modern embodiment of finding Ehrlich's "lock" for a given chemical "key." As described in the search results, this process can be likened to "finding a needle in a haystack" [8]. The primary modern method for this is chemoproteomics, which can be broadly divided into two strategies: probe-based and probe-free methods [8].

Probe-based chemoproteomics relies on modifying the hit compound to create a chemical probe. This probe typically contains three elements:

- The bioactive parent compound: Responsible for target engagement.

- A reporter tag (e.g., biotin): Allows for affinity purification of the bound protein complexes.

- A linker/spacer group: Connects the compound to the tag, often incorporating a photoaffinity group for UV-induced crosslinking to "trap" transient interactions, and a click chemistry handle (e.g., an alkyne) for bioorthogonal conjugation to the reporter tag after cellular treatment [8].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Probe-Based Chemoproteomics

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Chemical Probe | Engineered version of the hit compound used to "fish out" molecular targets from a complex biological lysate [8]. |

| Photoaffinity Label (e.g., diazirine) | Incorporated into the probe linker; upon UV irradiation, it forms a highly reactive carbene that covalently crosslinks the probe to its protein target, preserving transient interactions [8]. |

| Click Chemistry Handle (e.g., alkyne) | A small, inert chemical group (e.g., an alkyne) on the probe that allows for a specific, late-stage conjugation reaction with an azide-bearing reporter tag (e.g., biotin-azide) after the probe has engaged its target in cells. This minimizes the probe's size and avoids altering its bioavailability [8]. |

| Streptavidin Beads | The solid-phase affinity resin used to capture and enrich the biotin-tagged protein-probe complexes from the cell lysate, drastically reducing sample complexity prior to mass spectrometry analysis [8]. |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry | The analytical engine for identifying the enriched proteins. It quantifies the proteins purified by the probe compared to a control sample, revealing the specific bound targets [8]. |

Probe-free chemoproteomic methods have been developed more recently. These methods detect protein-ligand interactions directly from a complex mixture without the need to chemically modify the original hit compound, thus avoiding potential alterations to its bioactivity and selectivity [8].

Expanding the Arsenal: Advanced Genetic and Computational Tools

Beyond chemoproteomics, other methods are critical for comprehensive target identification and validation. Chemical-genetic interaction profiling is a powerful approach that involves systematically assessing how genetic variation affects a drug's activity [9] [7]. A typical protocol involves:

- Screening a library of yeast gene deletion strains (or CRISPR-based knockouts in mammalian cells) against a library of compounds.

- Generating a Chemical-Genetic Interaction Matrix, where each data point represents the sensitivity of a particular mutant strain to a specific compound [9].

- Identifying "cryptagens" (or dark chemical matter)—compounds with no effect on wild-type cells but that inhibit growth in specific genetic backgrounds, revealing latent biological activity [9].

- Benchmarking synergistic combinations by testing all pairwise combinations of selected cryptagens to generate a dataset for predicting compound synergism [9].

Furthermore, knowledge-based computational methods leverage existing databases of chemical and biological information to predict the targets of a novel compound based on structural similarity or shared phenotypic profiles [8].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Insights from Chemical Genetics Studies

The following tables summarize quantitative data and key characteristics from the search results, illustrating the scope and standards of the field.

Table 3: Quantitative Datasets for Synergy Prediction from Chemical-Genetic Screens [9]

| Dataset Name | Scale of Measurement | Key Findings and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical-Genetic Matrix (CGM) | 492,126 chemical-gene interaction tests (5,518 compounds vs. 242 yeast deletion strains) | Identified 1,434 cryptagens. Serves as a resource for discovering and predicting synergistic compound interactions. |

| Cryptagen Matrix (CM) | 8,128 pairwise chemical-chemical interaction tests (128 cryptagens) | A benchmark dataset for developing and refining computational algorithms for predicting compound synergism. |

Table 4: Characteristics of a High-Quality Chemical Probe [8]

| Characteristic | Definition and Importance | Pitfalls to Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Potency | High biological activity, typically with an IC50 or EC50 in the nanomolar range. | Weak compounds may require high concentrations that lead to off-target effects. |

| Selectivity | Binds to and modulates the intended target with minimal activity against related targets (e.g., within a protein family). | Lack of selectivity can lead to ambiguous or misleading biological data. |

| Well-Understood Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) | Data exists on how chemical modifications affect potency and selectivity, confirming the pharmacophore. | Compounds classified as PAINS (pan-assay interference compounds) should be avoided due to non-specific reactivity [8]. |

From Paul Ehrlich's theoretical "side-chains" and "magic bullets" to the sophisticated chemical probes and 'omics-level datasets of today, the fundamental premise remains unchanged: specific small molecules can be used to reveal the inner workings of biology with precision. The field of chemical genetics has formalized this premise into a disciplined, powerful, and multifaceted research paradigm. It provides an indispensable toolkit for deconvoluting complex biological pathways, identifying novel druggable targets, and ultimately advancing the discovery of new therapeutics. As Ehrlich himself stated, "We must learn to shoot microbes with magic bullets." The discipline of chemical genetics represents the direct and thriving legacy of that vision.

Chemical genetics has emerged as a powerful disciplinary approach that complements classical genetics by using small molecules to perturb biological systems. Whereas classical genetics manipulates genes directly to study resulting phenotypes, chemical genetics employs small molecules to modulate protein function, offering distinct advantages in temporal control, reversibility, and applicability across biological systems. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodological frameworks, and experimental applications of chemical genetics, highlighting how it extends the capabilities of classical genetic approaches while operating within a complementary scientific paradigm. Through comparison of foundational concepts, experimental workflows, and research applications, we demonstrate how chemical genetics provides unique insights into gene function, protein networks, and therapeutic development.

Defining the Disciplines

Classical genetics is the foundational discipline focused on studying heredity and gene function through the observation of phenotypic outcomes resulting from genetic manipulation or natural genetic variation. This approach primarily investigates how specific genetic alterations—whether naturally occurring or experimentally induced—affect the phenotype of an organism, tracing the line of inheritance and mapping traits to specific genomic locations [10].

Chemical genetics represents a more recent disciplinary framework that employs small molecules to modulate protein function as a means to manipulate biological systems. These small molecules, which can be either naturally derived or synthetically produced, bind to proteins and modify gene expression patterns or protein activity. The field systematically investigates the relationship between small molecule perturbations and resulting phenotypic changes, establishing connections between chemical structures and biological responses [11].

Core Principles and Philosophical Frameworks

The philosophical distinction between these approaches centers on their respective intervention strategies. Classical genetics operates through direct genetic manipulation—creating mutations, deletions, or overexpression of genes—and observing the consequent phenotypic effects. This follows a "from genotype to phenotype" investigative pathway [10].

In contrast, chemical genetics intervenes at the protein level, using small molecules as reversible modulators of protein function. This introduces several distinctive characteristics: the ability to achieve temporal control over protein activity (often within minutes or hours), dose-dependent effects that can be titrated, and generally reversible effects upon compound removal. This approach is particularly valuable for studying essential genes where traditional genetic knockout would be lethal, and for investigating dynamic biological processes that operate across specific timeframes [11].

Methodological Approaches: Forward and Reverse Paradigms

Both chemical genetics and classical genetics employ forward and reverse approaches, though they differ fundamentally in their implementation and specific applications. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these methodological paradigms.

Table 1: Comparison of Forward and Reverse Approaches in Chemical Genetics and Classical Genetics

| Aspect | Forward Chemical Genetics | Reverse Chemical Genetics | Forward Classical Genetics | Reverse Classical Genetics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Phenotypic observation after small molecule application | Known protein of interest | Phenotypic observation in mutant organisms | Known gene sequence |

| Experimental Process | Screen compound libraries for desired phenotype; identify protein target | Screen compounds against specific protein; test phenotypic effects | Generate random mutations; map responsible genes | Create targeted genetic mutation; observe phenotype |

| Primary Output | Identification of protein targets for bioactive compounds | Small molecules that modulate specific protein function | Genes linked to specific traits or phenotypes | Phenotypic consequences of specific genetic alterations |

| Key Applications | Drug discovery, pathway analysis | Targeted therapeutics, protein function studies | Gene discovery, genetic mapping | Functional validation of genes |

Forward Approaches

In forward chemical genetics, researchers begin with phenotypic observation by applying diverse small molecule libraries to cells or model organisms and screening for compounds that induce a specific phenotype of interest. Once a bioactive compound is identified, the subsequent target identification phase seeks to determine the specific protein to which the compound binds, thus connecting chemical perturbation to biological function through protein intermediation [11].

Forward classical genetics follows a conceptually similar phenotype-to-genotype pathway but employs different methods. Researchers begin with observable phenotypic variations—either naturally occurring or induced through mutagenesis—and then employ genetic mapping techniques to identify the responsible genes and their locations within the genome [10].

Reverse Approaches

Reverse chemical genetics initiates investigation at the protein level, beginning with a protein of known function or interest. Researchers screen compound libraries to identify small molecules that interact with and modulate the target protein's activity. These candidate compounds are then introduced into cellular or organismal systems to observe resulting phenotypic effects, thereby establishing functional connections between specific protein modulation and system-level phenotypes [11].

Reverse classical genetics operates from a known gene sequence toward phenotypic characterization. Researchers create specific, targeted alterations in gene sequences (through knockout, knockdown, or transgenic approaches) and then systematically analyze the resulting phenotypic consequences to determine gene function [10].

Experimental Design and Workflows

Chemical Genetics Experimental Framework

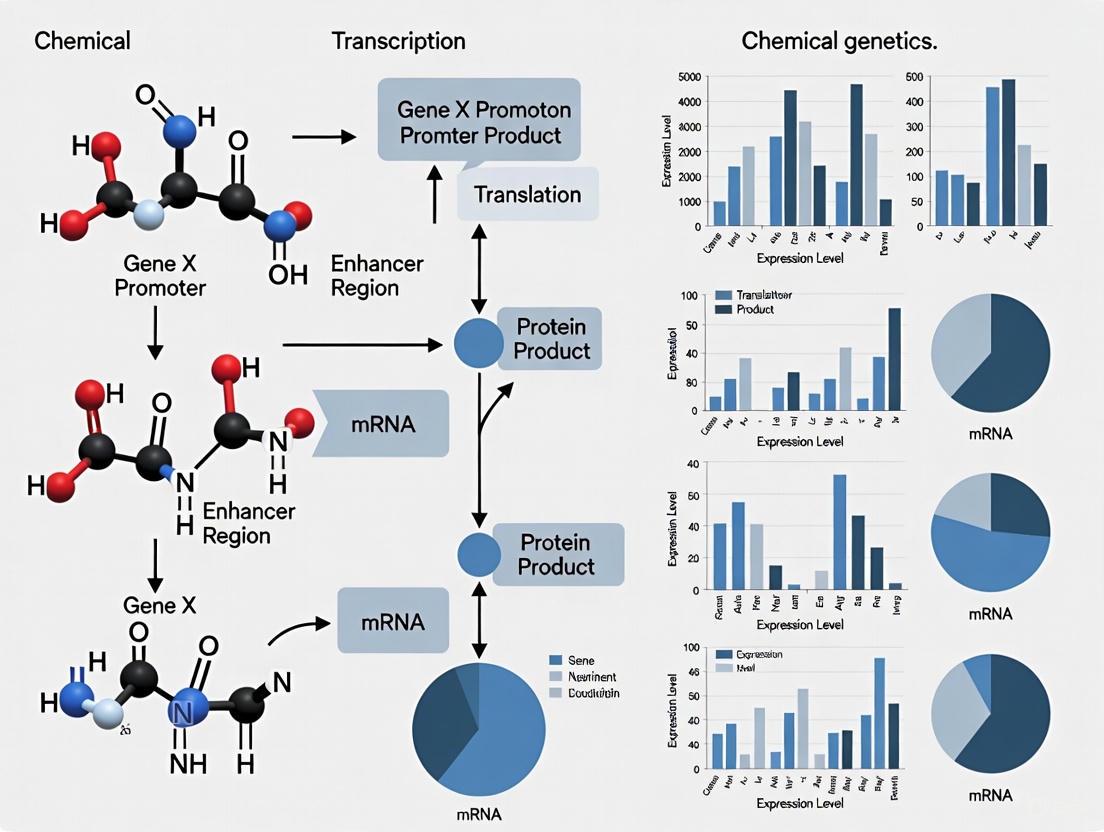

Chemical genetics employs sophisticated experimental frameworks that integrate molecular biology, high-throughput screening, and bioinformatics. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for a chemical genetics screening experiment:

Figure 1: Generalized workflow for chemical genetics screening approaches, showing both forward and reverse methodologies.

Key Research Reagents and Experimental Components

Successful chemical genetics research requires specialized reagents and tools. The table below details essential components of the chemical genetics experimental toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Genetics

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Collections of diverse small molecules for screening | NIH library of ~500,000 compounds; natural product collections |

| Hypomorph Libraries | Bacterial strains with essential gene knock-downs | M. tuberculosis hypomorph libraries with barcoded mutants [12] |

| Barcoded Cell Pools | Genetically distinct, trackable cell populations | QMAP-Seq barcoded breast cancer cell lines with inducible knockouts [13] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Precision gene editing tools | Doxycycline-inducible Cas9 for temporal control of gene knockout [13] |

| Spike-in Standards | Reference cells for quantitative normalization | 293T cell spike-in standards with unique sgRNA barcodes in QMAP-Seq [13] |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Computational tools for data analysis | CGA-LMM for analyzing chemical-genetic interaction data [12] |

Technical Applications and Research Applications

Methodological Innovations in Chemical Genetics

Recent advances in chemical genetics have introduced sophisticated methodological innovations that enhance the precision and scope of investigation. The CGA-LMM (Chemical-Genetic Analysis with Linear Mixed Models) statistical approach represents a significant innovation that improves the identification of genuine chemical-genetic interactions by modeling the concentration-dependent effects of compounds on hypomorph libraries. This method treats drug concentration as a quantitative variable, capturing the relationship between gene abundance and drug concentration through slope coefficients derived from linear mixed models [12] [14].

The QMAP-Seq (Quantitative and Multiplexed Analysis of Phenotype by Sequencing) platform enables high-throughput chemical-genetic profiling in mammalian systems by leveraging next-generation sequencing and cell line barcoding. This approach allows parallel screening of thousands of chemical-genetic interactions through short-term compound treatment of pooled cell populations, followed by sequencing-based quantification of cell abundance changes [13].

Applications in Pathogen Research

Chemical genetics has proven particularly valuable in studying microbial pathogens and identifying potential drug targets. Research on pathogens like Cryptosporidium parvum has employed chemical-genetic approaches to validate drug targets, combining chemoproteomics with knockdown, overexpression, and site-directed mutagenesis to demonstrate specific targeting of essential parasite enzymes [15].

In mycobacterial research, chemical-genetic interaction profiling using hypomorph libraries of M. tuberculosis has successfully identified known target genes or expected pathways for multiple anti-tubercular antibiotics. These approaches exploit the synergistic fitness defects that occur when protein depletion combines with antibiotic exposure, particularly for genes involved in the drug's mechanism of action [12] [14].

Applications in Cancer and Mammalian Systems

In cancer research, chemical genetics enables systematic identification of synthetic lethal interactions—where combination of a genetic variant and chemical perturbation proves lethal while individual perturbations are viable. QMAP-Seq has been applied to profile interactions within the proteostasis network, identifying clinically actionable drug vulnerabilities based on the activation status of stress response factors in cancer cells [13].

The following diagram illustrates a specific chemical-genetics screening workflow as implemented in the QMAP-Seq protocol:

Figure 2: QMAP-Seq experimental workflow for quantitative chemical-genetic profiling in mammalian cells, incorporating spike-in standards for normalization.

Comparative Analysis: Complementary Strengths and Limitations

Advantages of Chemical Genetics

Chemical genetics offers several distinctive advantages that complement classical genetic approaches:

Temporal Control and Reversibility: Small molecule effects can be precisely timed and are often reversible upon compound removal, enabling study of essential biological processes at specific developmental stages or timepoints [11].

Dose-Dependency: Compound concentration can be titrated to achieve graded phenotypic effects, allowing for fine-tuning of protein inhibition or activation levels and modeling of threshold effects [12].

Applicability Across Biological Systems: Chemical genetics can be applied to systems where genetic manipulation is challenging or impossible, including primary human cells and clinical samples [13].

Functional Insight at Protein Level: By targeting proteins directly, chemical genetics provides information about protein function and regulation in native cellular contexts, complementing genetic information about gene necessity [11].

Limitations and Challenges

Despite its strengths, chemical genetics faces several distinct challenges:

Target Identification Complexity: Deconvoluting the specific protein target of a bioactive compound remains technically challenging and may require multiple orthogonal approaches [11].

Off-Target Effects: Small molecules may interact with multiple protein targets, potentially confounding phenotypic interpretation and requiring careful control experiments [11].

Chemical Tool Quality: The utility of chemical genetics depends heavily on the quality, specificity, and potency of available chemical probes, which may be limited for many targets [13].

Integration with Classical Genetics

The most powerful insights often emerge from integrating chemical and classical genetic approaches. For example, combining hypomorph libraries (classical genetics) with compound screening (chemical genetics) enables systematic mapping of chemical-genetic interactions [12]. Similarly, using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing (classical genetics) to create isogenic cell lines followed by compound treatment (chemical genetics) allows precise determination of gene-compound interactions [13].

The table below summarizes key distinctions and complementary features of these approaches:

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Chemical Genetics and Classical Genetics

| Characteristic | Chemical Genetics | Classical Genetics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Intervention | Small molecule compounds | Genetic alterations |

| Molecular Target | Proteins | Genes/DNA |

| Temporal Control | High (minutes to hours) | Limited (developmental timescales) |

| Reversibility | Generally reversible | Often irreversible |

| Dose-Response | Graded, tunable effects | Typically binary effects |

| Perturbation Scope | Protein function and interaction networks | Gene presence/expression |

| Throughput Potential | High-throughput screening feasible | Lower throughput for organismal studies |

| Target Identification | Challenging, requires deconvolution | Straightforward through genetic mapping |

| Applicability | Broad across cell types and organisms | Limited to genetically tractable systems |

Chemical genetics represents both a complement and alternative to classical genetics, offering distinct methodological advantages for probing biological function and identifying therapeutic opportunities. While classical genetics remains foundational for establishing gene-phenotype relationships, chemical genetics extends this paradigm by enabling temporal control, dose-dependent effects, and intervention at the protein level. The integration of both approaches—through chemical-genetic interaction screening in genetically defined systems or target validation using genetic tools—provides a powerful synthetic framework for biological discovery and therapeutic development. As chemical library diversity expands and genetic manipulation techniques advance, the continued convergence of these disciplines promises to accelerate our understanding of complex biological systems and enhance our ability to develop targeted therapeutic interventions.

Chemical genetics is a research approach that uses small molecules as probes to study protein functions in cells or whole organisms, serving as a powerful tool for understanding gene-product function [7]. The field is predicated on the principle that small molecules, typically man-made or derived from natural sources, can bind to proteins and modify their function, thereby allowing researchers to investigate biological processes at molecular, cellular, or organismal levels [11]. This approach parallels classical genetics but uses exogenous ligands as "mutation equivalents" that can alter protein function conditionally and reversibly, enabling kinetic analysis of in vivo consequences [16]. The core premise, with origins tracing back to Paul Ehrlich's receptor concept, is that low-molecular-weight compounds act by binding to specific protein receptors within biological systems [16].

Chemical genetics has emerged as a distinct discipline since the 1990s, differing from classical genetics as it targets proteins rather than genes directly [11]. This protein-centric approach provides several advantages, including the ability to conditionally modulate biological systems with temporal control, overcome limitations of genetic approaches such as lethality and redundancy, and study biological processes in more disease-relevant settings [7] [16]. The field encompasses two fundamental research strategies—forward and reverse chemical genetics—that mirror the approaches established in classical genetics but employ small molecules as the key investigative tools [17] [18].

Fundamental Principles: Forward vs. Reverse Chemical Genetics

Conceptual Framework and Definitions

The two primary approaches in chemical genetics are defined by their starting points and direction of investigation. Forward chemical genetics begins with a phenotypic observation and works backward to identify the protein target responsible, following a "phenotype-to-genotype" trajectory [17] [11]. In this approach, researchers first apply small molecules to cells or organisms and screen for compounds that induce a phenotype of interest, then work to identify the specific protein targets to which these active compounds bind [18] [16]. This strategy is inherently unbiased and hypothesis-generating, allowing for the discovery of novel biological pathways without preconceived notions about the underlying mechanisms [17].

Conversely, reverse chemical genetics starts with a known protein of interest and investigates what phenotypic effects result from its modulation, following a "genotype-to-phenotype" path [17]. Researchers begin with a purified protein and screen for small molecules that bind to it, then introduce these compound-protein complexes into cells or organisms to observe the resulting phenotypes [11]. This approach is hypothesis-driven and targeted, as it tests specific assumptions about protein function based on existing knowledge [17].

The relationship between these approaches mirrors that of forward and reverse genetics, with the key distinction being the use of small molecules rather than genetic modifications to probe biological function [18]. In classical forward genetics, random mutagenesis is followed by phenotypic screening and identification of causative genes [19] [20], whereas in forward chemical genetics, libraries of small molecules serve as the source of phenotypic variation [16].

Comparative Analysis: Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Comparison of Forward and Reverse Chemical Genetics Approaches

| Aspect | Forward Chemical Genetics | Reverse Chemical Genetics |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Phenotype of interest [17] | Known gene or protein [17] |

| Approach | Phenotype-to-genotype [17] | Genotype-to-phenotype [17] |

| Hypothesis Relationship | Hypothesis-generating [17] | Hypothesis-driven [17] |

| Nature of Inquiry | Unbiased discovery [17] [20] | Targeted investigation [17] |

| Primary Screening Context | Cells or whole organisms [18] | Purified protein systems [11] |

| Key Strength | Discovers novel biology and unexpected gene functions [17] | Efficiently tests specific protein functions [17] |

| Main Challenge | Target identification can be complex and time-consuming [18] | Relies on prior knowledge and may miss novel interactions [17] |

| Typical Applications | Pathway discovery, novel target identification [18] | Protein function validation, drug optimization [11] |

Forward chemical genetics excels in its unbiased nature, allowing researchers to discover novel genes and pathways without prior assumptions about biological mechanisms [17]. This approach has led to significant biological insights, such as the discovery of FKBP12, calcineurin, and mTOR through the effects of cyclosporine A and FK506 on T-cell receptor signaling [18]. However, a significant challenge is the subsequent need to identify the molecular targets of bioactive small molecules, which can be complex and time-consuming [18].

Reverse chemical genetics offers a more direct path from protein to function and is more efficient for testing specific hypotheses about known genes [17]. This approach benefits from knowing the protein target from the outset, which facilitates mechanistic studies and medicinal chemistry optimization [18]. The limitation is its dependence on existing knowledge, potentially missing important novel genes or interactions outside current understanding [17].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Forward Chemical Genetics Workflow

The forward chemical genetics approach follows a systematic three-step procedure that mirrors classical forward genetics but uses small molecules instead of mutagens [16]. The typical workflow encompasses the following stages:

Step 1: Library Assembly and Compound Selection Researchers first assemble a diverse collection of chemical ligands capable of altering protein function. These libraries can consist of small organic molecules or peptide aptamers, with modern collections often containing hundreds of thousands of compounds [11] [16]. The National Human Genome Research Institute, for instance, has developed a library of five hundred thousand small molecules for research use [11]. Ideal compounds should possess structural diversity, adequate membrane permeability for cellular assays, and minimal nonspecific binding properties [16].

Step 2: Phenotypic Screening The compound library is screened using robust phenotypic assays that monitor biological processes of interest. In a typical high-throughput setup, compounds are arrayed in multi-well plates containing cellular systems or model organisms, with each well receiving a different small molecule [11] [16]. The assays are designed to detect specific phenotypic changes relevant to the biological question, such as alterations in cell morphology, proliferation, differentiation, or organismal development [18]. For example, in a screen for compounds affecting the immune system, researchers might measure cytokine production or cell surface marker expression [18].

Step 3: Target Identification and Validation Once bioactive compounds are identified, the most challenging phase begins: determining the specific protein targets responsible for the observed phenotypes. Multiple complementary approaches are typically employed:

Biochemical Affinity Purification: Small molecules are immobilized on solid supports and used as bait to capture binding proteins from cell lysates. Control experiments using inactive analogs or capped beads without compound help distinguish specific binding from background interactions [18]. Recent advancements include photoaffinity labeling for covalent crosslinking and tandem affinity purification to reduce false positives [18].

Genetic Interaction Methods: Genetic manipulation is used to modulate presumed targets in cells, observing changes in small-molecule sensitivity. This can include overexpression studies, RNA interference, or CRISPR-based approaches [18].

Computational Inference: Pattern recognition algorithms compare small-molecule effects to those of known reference compounds or genetic perturbations, generating target hypotheses based on similarity metrics [18].

Functional Validation: Candidate targets are validated using complementary approaches such as genetic rescue experiments, where restoring target function reverses the compound-induced phenotype, or orthogonal binding assays that confirm direct molecular interactions [18].

Reverse Chemical Genetics Workflow

The reverse chemical genetics approach follows a complementary pathway that begins with a defined protein target [11]. The standardized protocol includes these critical steps:

Step 1: Target Selection and Protein Production The process initiates with the selection of a specific protein target based on existing biological knowledge, such as genomic data, expression patterns, or pathway analysis [18]. The target protein is then produced in purified form, typically through recombinant expression systems that yield sufficient quantities for high-throughput screening. For membrane proteins such as G-protein-coupled receptors, this may require specialized expression systems that maintain protein stability and function [16].

Step 2: In Vitro Screening Against Purified Target Purified proteins are exposed to compound libraries in controlled in vitro assays designed to detect binding or functional modulation. Common assay formats include:

- Enzyme activity assays measuring substrate conversion

- Binding assays using fluorescence polarization or surface plasmon resonance

- Structural studies examining protein-ligand co-crystals These targeted screens efficiently identify compounds with desired effects on the specific protein [11] [18].

Step 3: Cellular and Organismal Phenotypic Analysis Active compounds identified in vitro are then introduced into cellular systems or whole organisms to characterize resulting phenotypes. This stage determines whether modulating the target protein produces the expected biological effects in more complex, physiologically relevant environments [11]. Researchers typically examine multiple phenotypic parameters to understand the broader consequences of target modulation and identify potential off-target effects [18].

Step 4: Mechanism of Action Studies Following confirmation of phenotypic effects, detailed mechanistic studies investigate how compound binding translates to functional changes. Approaches include:

- Examining downstream pathway activation or inhibition

- Determining structural changes through crystallography or NMR

- Analyzing effects on protein-protein interactions

- Studying consequences in genetically modified systems [18]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Chemical Genetics

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Libraries | Natural product collections, combinatorial chemistry libraries, peptide aptamer libraries [16] | Source of diverse small molecules for screening; provides "mutation equivalents" for protein function alteration [16] |

| Mutagenic Agents | N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU), ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS), radiation, transposons [19] [17] | Generate random mutations in model organisms for forward genetics; ENU creates ~60 coding changes per sperm in mice [20] |

| Affinity Purification Reagents | Immobilized compound beads, photoaffinity probes, crosslinking agents [18] | Enable capture and identification of protein targets; photoaffinity labeling allows covalent modification for low-abundance targets [18] |

| Model Organisms | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Drosophila melanogaster, Danio rerio, Mus musculus [19] [17] [20] | Provide biological context for phenotypic screening; mice share 99% gene homology with humans [20] |

| Genome Engineering Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, ZFNs, TALENs [21] | Enable targeted genetic modifications for validation; CRISPR creates genome-wide mutation libraries for forward genetics [21] |

Applications in Biological Research and Drug Discovery

Historical Success Stories and Case Studies

Chemical genetics approaches have yielded significant insights across diverse biological domains, often providing unexpected discoveries that reshaped entire fields of research. Notable examples include:

Immunosuppressants and T-cell Signaling: The discoveries of cyclosporine A and FK506 as immunosuppressants through phenotypic screening exemplify the power of forward chemical genetics [11] [18]. Although these compounds were initially identified for their effects on T-cell function, their molecular targets—FKBP12, calcineurin, and mTOR—were only elucidated through subsequent target identification efforts [18]. These findings not only revealed key components of immune signaling pathways but also demonstrated how small molecules can serve as powerful tools for dissecting complex biological processes.

Pain Management and COX Pathways: Aspirin's mechanism of action remained unknown for decades after its clinical adoption [11]. Through chemical genetics approaches, researchers eventually identified cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) as its primary target, explaining both its anti-inflammatory effects and gastrointestinal side effects [11]. This discovery subsequently led to the identification of COX-2 and the development of COX-2 inhibitors, illustrating how understanding small molecule targets can drive therapeutic innovation [11].

Epigenetics and Bromodomain Biology: Recent applications of chemical genetics have advanced epigenetic research through the development of bromodomain inhibitors [7]. The challenge of achieving single-target selectivity has been addressed through advanced approaches like the "bump-and-hole" strategy, which enables probing of the BET bromodomain subfamily with unprecedented specificity [7]. Additionally, PROTAC (proteolysis-targeting chimera) compounds have demonstrated significantly greater efficacy than standard domain inhibitors, highlighting how chemical tools can enhance both biological understanding and therapeutic potential [7].

Technological Advances and Future Directions

The field of chemical genetics continues to evolve rapidly, driven by technological innovations that enhance both forward and reverse approaches:

Advanced Screening Platforms: The development of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), 3D culture systems, and organ-on-a-chip technologies has created more physiologically relevant screening environments [22]. These platforms enable forward chemical genetics screens in contexts that better recapitulate human disease biology, potentially increasing the translational value of discoveries [22].

CRISPR-Cas Integration: The CRISPR-Cas system has emerged as a revolutionary tool that bridges forward and reverse chemical genetics [21]. For forward genetics, CRISPR enables the creation of genome-wide mutation libraries with known target sites, overcoming the limitations of random mutagenesis approaches [21]. In reverse genetics, it facilitates rapid generation of precise genetic models to validate compound targets and mechanisms [21]. The convergence of genetic and chemical approaches through CRISPR technology represents a powerful synthesis for future investigations.

Accelerated Target Identification: Advances in "instant positional cloning" and mapping-by-sequencing have dramatically reduced the time required for target identification in forward chemical genetics [22]. Where previously identifying causative mutations required extensive mapping efforts over many months, whole-genome sequencing now enables rapid mutation discovery within weeks [20] [22]. These improvements have removed a major bottleneck in the forward chemical genetics pipeline.

Computational and Chemoproteomic Advances: New computational methods for target inference based on chemical similarity or gene expression signatures increasingly complement experimental approaches [18]. Simultaneously, advanced chemoproteomic techniques such as activity-based protein profiling and thermal proteome profiling provide more comprehensive views of small molecule interactions within complex proteomes [18]. These integrated approaches enhance the efficiency and accuracy of target identification while providing insights into polypharmacology.

Forward and reverse chemical genetics represent complementary pillars in modern biological research, each with distinct strengths and applications. Forward chemical genetics, with its unbiased, phenotype-first approach, excels at discovering novel biology and unexpected gene functions, making it ideal for exploratory research and pathway discovery. Reverse chemical genetics, with its targeted, hypothesis-driven methodology, efficiently elucidates specific protein functions and facilitates therapeutic development.

The ongoing integration of these approaches with technological advances in screening, genomics, and bioinformatics continues to expand their power and applicability. As chemical genetics evolves, the convergence of forward and reverse paradigms through tools like CRISPR and advanced chemoproteomics promises to accelerate both basic biological discovery and therapeutic development, solidifying the role of small molecules as indispensable probes for understanding and manipulating biological systems.

The field of drug discovery has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from the serendipitous discovery of natural products to the rational design of systematic chemical libraries. This evolution represents a fundamental change in strategy—from exploring nature's random bounty to employing predictive metrics and structured design principles to maximize chemical diversity and screening efficiency. The journey began with natural product libraries derived from microorganisms, plants, and other biological sources, which offered immense chemical diversity but posed challenges in standardization, reproducibility, and scalability [23]. This historical progression has been accelerated by the integration of chemical genetics approaches, which systematically explore gene-compound interactions to elucidate mechanisms of action, resistance pathways, and cellular targets [3].

The driving force behind this transition is the continuous reinvention of drug discovery methodologies to avail itself of new scientific tools and trends [23]. While natural products have served as the cornerstone of traditional drug discovery, modern approaches now combine genetic barcoding with metabolomics to help investigators build libraries aimed at achieving predetermined levels of chemical coverage [23]. This whitepaper examines the historical context of this evolution, detailing the quantitative tools, experimental protocols, and strategic frameworks that have shaped contemporary library design, with particular emphasis on their application within chemical genetics research.

Historical Foundations: Natural Product Libraries

Traditional Natural Product Sourcing

Natural product drug discovery efforts have historically relied on libraries of organisms to provide access to diverse pools of compounds, with fungal and bacterial isolates representing particularly rich sources of chemical diversity [23]. These libraries faced fundamental challenges in design and development, with questions about optimal collection sizes "largely driven by adherence to dogma or convenience rather than evidence-based reasoning" [23]. The degree of chemical diversity in a screening collection has consistently been identified as a key contributor to the success or failure of bioassay screening endeavors [23].

Traditional natural product libraries were primarily built from environmental isolates, with early efforts focusing on extensive sampling to capture metabolic diversity. For example, the University of Oklahoma's Citizen Science Soil Collection Program obtained 9,670 soil samples yielding 78,581 fungal isolates, from which 219 candidate Alternaria isolates were identified for chemical diversity studies [23]. These efforts recognized that even within low-ranking monophyletic clades (e.g., a species or genera), metabolomes can exhibit divergent chemical profiles due to the swapping, recombination, and alteration of natural product biosynthetic gene clusters and their molecular controlling factors [23].

Quantitative Assessment of Natural Product Diversity

A breakthrough in natural product library development came with the implementation of quantitative metrics to assess chemical coverage. Research demonstrated that combining modest investments in ITS-based sequence information with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) data offered actionable insights into chemical diversity trends [23]. This bifunctional approach enabled:

- Assessment of natural product chemical diversity within species complexes

- Identification of prospective pools of under- and oversampled secondary-metabolite scaffolds

- Application of quantitative metrics to establish and track chemical diversity goals [23]

In a landmark study focusing on Alternaria fungi, researchers determined that a surprisingly modest number of isolates (195) was sufficient to capture nearly 99% of chemical features in the data set, yet 17.9% of chemical features appeared in single isolates, suggesting ongoing exploration of nature's metabolic landscape [23]. This highlighted both the potential efficiency of well-designed libraries and the challenges of capturing rare metabolites.

Table 1: Key Findings from Alternaria Chemical Diversity Study

| Parameter | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal isolate number | 195 isolates | Nearly 99% chemical feature coverage achievable with modest sampling |

| Rare chemical features | 17.9% appeared in single isolates | Substantial unique chemistry exists in rare isolates |

| Clade diversity | Non-equivalent levels across subclades | Phylogenetic guidance improves collection efficiency |

| Assessment method | ITS sequencing + LC-MS metabolomics | Bifunctional approach enables real-time library adjustment |

The Rise of Systematic Chemical Libraries

Theoretical Foundations and Design Principles

The transition to systematic chemical libraries was fueled by recognition that "despite the vast amounts of time, money, and energy poured into building small-molecule screening collections, the answers to many basic questions about their design and development... are largely driven by adherence to dogma or convenience rather than evidence-based reasoning" [23]. This realization sparked the development of principles for rational library design that could be adjusted in real-time based on quantitative diversity assessments.

Opinions influencing library design have shifted tremendously over decades, with the large collections of the 1980s and 1990s (e.g., combinatorial chemistry) being replaced by smaller tailored collections in the early 2000s (e.g., "focused" collections), and moving toward megascale libraries in recent years (e.g., DNA-encoded libraries) [23]. This evolution reflects an ongoing search for optimal strategies to balance size, diversity, and screening efficiency.

DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs)

DNA-encoded libraries represent a revolutionary approach that combines principles of molecular biology with synthetic chemistry. DELs are "collections of molecules, individually coupled to distinctive DNA tags serving as amplifiable identification barcodes" [24]. This technology enables the construction and screening of libraries of unprecedented size, leading to the discovery of highly potent ligands that have progressed to clinical trials [24].

DEL Construction Methodologies

Several encoding strategies have been developed for DEL construction:

- Single-pharmacophore libraries: Constructed using DNA-recorded synthesis, which relies on split-and-pool procedures where libraries are built through series of chemical transformations, each encoded by addition of DNA fragments that uniquely identify them [24]

- Dual-pharmacophore libraries: Feature two different chemical moieties attached to extremities of complementary DNA strands, acting synergistically for specific protein recognition [24]

- DNA-templated synthesis: Uses pools of pre-encoded DNA templates to direct chemical reactions, leveraging hydrogen bonding between nucleobases to accelerate bimolecular reactions [24]

The construction of DELs typically involves multiple cycles of split-and-pool synthesis, where each chemical building block is coupled with a unique DNA barcode. After each synthesis step, all compounds are pooled together before being redistributed for the subsequent synthetic step, enabling exponential growth in library size [24].

Table 2: Comparison of Library Technologies

| Library Type | Typical Size | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Product | Hundreds to thousands of extracts | High scaffold diversity, biologically relevant | Standardization challenges, limited scalability |

| Traditional HTS | Up to 1-2 million compounds | Well-established infrastructure, individual compound testing | High cost, complex logistics |

| DNA-Encoded | Billions to trillions | Massive size, efficient selection process | Specialized expertise required, DNA-compatible chemistry needed |

Chemical Genetics: Bridging Natural Products and Systematic Libraries

Conceptual Framework

Chemical genetics serves as a bridge between natural product discovery and systematic library approaches, creating a powerful framework for understanding compound interactions with biological systems. Chemical genetics specifically refers to "the systematic assessment of the impact of genetic variance on the activity of a drug" [3]. This approach measures how each gene contributes to cellular fitness upon exposure to different chemicals, providing insights into mechanisms of action, resistance pathways, and potential therapeutic applications [3].

The foundation of modern chemical genetics rests on reverse genetics approaches, propelled by "the revolution in our ability to generate and track genetic variation for large population numbers" [3]. Genome-wide libraries containing mutants of each gene are profiled for changes in drug effects, comprising either loss-of-function (knockout, knockdown) or gain-of-function (overexpression) mutations in either arrayed or pooled formats [3].

Experimental Approaches in Chemical Genetics

Library Construction and Phenotyping

Chemical genetic approaches rely on systematically perturbing gene function and measuring resulting phenotypes after drug exposure:

- Mutant Libraries: Genome-wide collections have been constructed in numerous bacteria and fungi, with recent advances enabling creation for "almost any microorganism" [3]

- Barcoding Approaches: Pioneered in bacteria and perfected in yeast, these allow tracking relative abundance and fitness of individual mutants in pooled libraries with high throughput and dynamic ranges [3]

- High-Throughput Phenotyping: Experimental automation and image processing software enable arrayed library screening, while advances in high-throughput microscopy facilitate single-cell phenotyping and multi-parametric analysis [3]

Mechanism of Action (MoA) Identification

Chemical genetics enables MoA identification through two primary strategies:

- Target Identification Using Essential Gene Modulation: Libraries in which essential gene levels can be modulated reveal drug targets through either increased sensitivity when the target gene is down-regulated (haploinsufficiency profiling) or resistance when the target is overexpressed [3]

- Signature-Based Approach (Guilt-by-Association): Comparing "drug signatures" - compiled quantitative fitness scores for each mutant in a genome-wide deletion library - identifies compounds with similar mechanisms based on profile similarity [3]

Advanced Applications: Mapping Antibiotic Interactions

Chemical genetics has enabled systematic mapping of complex drug interactions, particularly relevant for addressing antibiotic resistance. Researchers have used E. coli single-gene deletion library chemical genetics data to devise metrics that discriminate between cross-resistance (XR - resistance to one drug confers resistance to another) and collateral sensitivity (CS - resistance to one drug increases sensitivity to another) [25].

This approach employed an outlier concordance-discordance metric (OCDM) based on extreme s-scores from chemical genetics profiles. The method successfully identified 404 cases of cross-resistance and 267 of collateral sensitivity, expanding known interactions by over threefold, with experimental validation confirming 64 out of 70 inferred interactions [25]. This demonstrates how systematic chemical genetics approaches can predict complex phenotypic outcomes from large-scale genetic interaction data.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Building Natural Product Libraries with Chemical Coverage Assessment

Principle: Combine genetic barcoding with metabolomic profiling to build natural product libraries with predetermined chemical coverage [23].

Steps:

- Sample Collection and Isolation: Collect environmental samples (e.g., soils) and isolate fungal or bacterial strains

- Genetic Barcoding: Sequence ITS regions for fungal isolates (or 16S for bacteria) to establish phylogenetic relationships

- Metabolite Profiling: Culture isolates under standardized conditions and analyze extracts using LC-MS to detect chemical features

- Chemical Feature Analysis: Process LC-MS data to identify unique chemical features based on retention time and mass-to-charge ratio

- Diversity Assessment: Generate feature accumulation curves to determine relationship between isolate number and chemical diversity coverage

- Library Optimization: Identify oversampled and undersampled clades to refine collection strategy

Key Reagents:

- Growth Media: Appropriate for target microorganisms (e.g., potato dextrose agar for fungi)

- DNA Extraction Kits: For high-throughput genomic DNA isolation

- PCR Reagents: For ITS amplification and sequencing

- LC-MS Grade Solvents: For metabolite extraction and separation

- LC-MS System: High-resolution mass spectrometry capable of untargeted metabolomics

Protocol 2: Chemical Genetics Screening with Pooled Mutant Libraries

Principle: Identify gene-drug interactions by measuring fitness changes in a pooled genome-wide mutant library after drug exposure [3].

Steps:

- Library Preparation: Grow pooled mutant library to mid-log phase

- Drug Exposure: Split culture and treat with drug of interest vs. vehicle control (multiple concentrations recommended)

- Outgrowth: Culture for multiple generations to allow fitness differences to manifest

- Sample Collection: Harvest genomic DNA from pre-exposure, drug-treated, and control populations

- Barcode Amplification: PCR amplify unique molecular barcodes from each sample

- Sequencing Library Preparation: Prepare samples for high-throughput sequencing

- Sequencing and Data Analysis: Sequence barcode regions and calculate enrichment/depletion of each mutant

Data Analysis:

- Fitness Score Calculation: Compute s-scores or similar metrics comparing barcode abundance in treated vs. control samples

- Hit Identification: Identify mutants with statistically significant fitness defects or advantages

- Pathway Enrichment: Group hits into functional pathways to identify biological processes affected

Protocol 3: DNA-Encoded Library Affinity Selection

Principle: Identify protein binders from DNA-encoded libraries using affinity selection and NGS decoding [24].

Steps:

- Target Immobilization: Immobilize purified protein target on solid support (e.g., streptavidin beads)

- Library Incubation: Incubate DEL with immobilized target (typically 1-4 hours)

- Washing: Remove non-specific binders with multiple wash steps

- Elution: Recover bound ligands (e.g., by pH change, temperature denaturation, or competition)

- PCR Amplification: Amplify DNA tags of enriched binders

- Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence amplified tags and identify enriched compounds

Key Considerations:

- Library Size: DELs can range from millions to trillions of compounds

- Counter-Selections: Include non-target proteins to identify non-specific binders

- Validation: Confirm binding of enriched hits using orthogonal methods

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Genetics and Library Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-wide mutant libraries | Systematic loss/gain-of-function screening | E. coli Keio collection, yeast knockout collection, CRISPRi libraries |

| DNA barcodes | Track mutant abundance in pooled screens | Unique molecular identifiers for high-throughput sequencing |

| LC-MS systems | Metabolite separation, detection, and quantification | Untargeted metabolomics, chemical feature identification |

| DNA-encoded libraries | Ultra-high-throughput compound screening | Billions-member libraries for affinity selection |

| Next-generation sequencers | Barcode quantification and decoding | Illumina platforms for mutant fitness and DEL analysis |

| Bioinformatics pipelines | Process sequencing and metabolomics data | Calculate fitness scores, identify enriched compounds |

The evolution from natural products to systematic libraries represents a paradigm shift in chemical genetics and drug discovery. This journey has transformed the field from one reliant on serendipity to one guided by quantitative principles, predictive metrics, and rational design. The integration of genetic barcoding with metabolomic profiling has enabled natural product libraries with predetermined chemical coverage, while DNA-encoded library technology has unlocked access to chemical spaces of unprecedented size. Most significantly, chemical genetics approaches have provided the conceptual framework bridging these methodologies, enabling systematic understanding of gene-compound interactions at genome-wide scale.

This historical progression continues to accelerate, with recent advances in CRISPR-based functional genomics, artificial intelligence-assisted library design, and multi-parametric phenotyping pushing the boundaries of what can be achieved with systematic approaches. What remains constant is the fundamental goal: to efficiently explore chemical space for compounds that modulate biological systems, delivering new therapeutic agents and research tools. The integration of historical wisdom with cutting-edge systematic approaches promises to continue driving innovation in chemical genetics and drug discovery for the foreseeable future.

How Chemical Genetics Works: Screening Strategies and Real-World Applications in Biomedicine

Chemical genetics research utilizes small molecules as probes to modulate and elucidate biological systems, drawing a direct analogy to classical genetics. In forward chemical genetics, libraries of diverse compounds are screened in living systems to discover molecules that induce a phenotypic effect, after which the protein target is identified. In reverse chemical genetics, proteins of known function are used to screen compound collections, and the resulting binding molecules are then applied to living systems to observe their biological effects [26]. The success of both approaches is fundamentally predicated on the quality and design of the underlying chemical libraries [3]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to building these essential resources, focusing on two primary sources: the strategic exploitation of natural product diversity and the systematic construction of combinatorial libraries.

Building Libraries from Natural Products

Natural products (NPs) and their derivatives constitute a significant proportion of approved drugs, accounting for approximately 56.1% of all new drugs approved by the FDA between 1981 and 2019 [27]. They are invaluable for drug discovery because they access chemical spaces and scaffold diversities that are often underrepresented in synthetic compound libraries [27]. Constructing a NP-based library requires a methodical approach to maximize chemical diversity while navigating specific technical and regulatory challenges.

Strategic Design and Diversity Assessment

The goal of library design is to achieve predetermined levels of chemical coverage efficiently. A powerful, bifunctional approach combines genetic barcoding with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) metabolome profiling to guide the library construction process [23].

- Genetic Barcoding: For fungi, the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence serves as a low-cost tool to establish phylogenetic relationships among environmental isolates. This allows for the organization of specimens into sequence-based clades, providing a biological framework for diversity sampling [23].

- Metabolome Profiling: LC-MS is used to profile the metabolome of each isolate, with each detected component treated as a chemical feature based on its LC retention time and mass-to-charge ratio. Principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) can then be applied to group isolates based on their metabolic profiles into distinct chemical clusters [23].

By integrating these two data types, researchers can identify overlooked pockets of chemical diversity, monitor coverage trends in real-time, and make actionable decisions to refocus collection strategies. A study on Alternaria fungi demonstrated that a surprisingly modest number of isolates (195) was sufficient to capture nearly 99% of the detected chemical features, yet 17.9% of features were unique to single isolates, underscoring the value of deep sampling to access rare metabolites [23].

A Practical Workflow for a Natural Product Library

The following workflow outlines the key steps in building a physical natural product library of plant origin.

Workflow for Building a Natural Product Library