Chemical Genetic Interactions: Leveraging Yeast and Parasite Models for Antiparasitic Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of chemical genetic interactions in accelerating drug discovery, with a focus on yeast and parasite models.

Chemical Genetic Interactions: Leveraging Yeast and Parasite Models for Antiparasitic Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of chemical genetic interactions in accelerating drug discovery, with a focus on yeast and parasite models. It covers foundational concepts where small molecules probe gene function, methodological advances in high-throughput screening and computational prediction, strategies for optimizing assays and interpreting complex data, and the critical validation of targets and interactions across biological contexts. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes how integrated chemical-genetic datasets are enabling the identification of novel anthelmintic candidates, prediction of compound synergism, and rational design of multi-target therapeutics against resistant parasitic infections.

Principles and Power of Chemical Genetics in Model Organisms

Chemical genomics and chemical genetics represent a powerful, interdisciplinary approach to biological investigation that uses small molecules as targeted tools to perturb and understand protein function. These fields sit at the intersection of chemistry and biology, employing exogenous chemical ligands to systematically study gene-product function within cellular or organismal contexts [1]. Whereas chemical genetics focuses on using small molecules to discover gene function and dissect biological pathways, chemical genomics expands this approach to systematically screen targeted chemical libraries across entire families of drug targets, with the ultimate goal of identifying novel drugs and drug targets [2]. The fundamental premise underlying both disciplines is that small molecules capable of binding directly to proteins can alter protein function, thereby enabling a kinetic analysis of the immediate consequences of these changes within complex biological systems [1]. This approach provides significant advantages over traditional genetic methods, including temporal control (compounds can be added or removed at will), applicability to essential genes, and direct relevance to therapeutic development [1] [3].

The context of a broader thesis on chemical-genetic interactions finds particularly fertile ground in yeast and parasite models. In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the availability of a complete collection of approximately 6,000 gene deletion mutants has enabled systematic detection of chemical-gene interactions, where specific genes are identified as necessary for tolerating chemical stress [4]. Meanwhile, in parasitic nematodes like Heligmosomoides bakeri, chemical-genomic approaches are revealing how host-parasite interactions exert strong selection pressures on parasite genomes, maintaining ancient genetic diversity through balancing selection [5]. These model systems provide complementary platforms for understanding fundamental biological processes and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions

Foundational Principles and Historical Context

The theoretical foundations of chemical genetics rest on two pivotal concepts developed over centuries: first, that pure biologically active substances can be obtained from natural sources, and second, that these substances act by binding to specific molecular targets within an organism [1]. The isolation of morphine from opium in the early 19th century established the principle that biological activity resides within pure substances, while Paul Ehrlich's development of the 'receptor' concept at the beginning of the 20th century established that small molecules interact with specific protein targets [1]. These foundational ideas have evolved into systematic approaches for determining protein function, with small molecules now recognized as generally useful tools for probing biological systems due to their ability to interact selectively with different cells, tissues, and organisms [1].

Chemical genomics extends these principles to a systematic, large-scale approach. As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health [6] [1] [4]. It aims to study the intersection of all possible drugs on all potential targets identified through genomic sequencing, particularly following the completion of the human genome project [2]. This approach integrates target and drug discovery by using active compounds as probes to characterize proteome functions, where the interaction between a small compound and a protein induces a phenotype that can be characterized and associated with molecular events [2].

Comparative Approaches: Forward versus Reverse Paradigms

The experimental framework of chemical genomics encompasses two complementary approaches: forward (classical) chemogenomics and reverse chemogenomics [2]. These paradigms differ in their starting points and experimental trajectories, yet both aim to connect chemical compounds with biological functions and phenotypes.

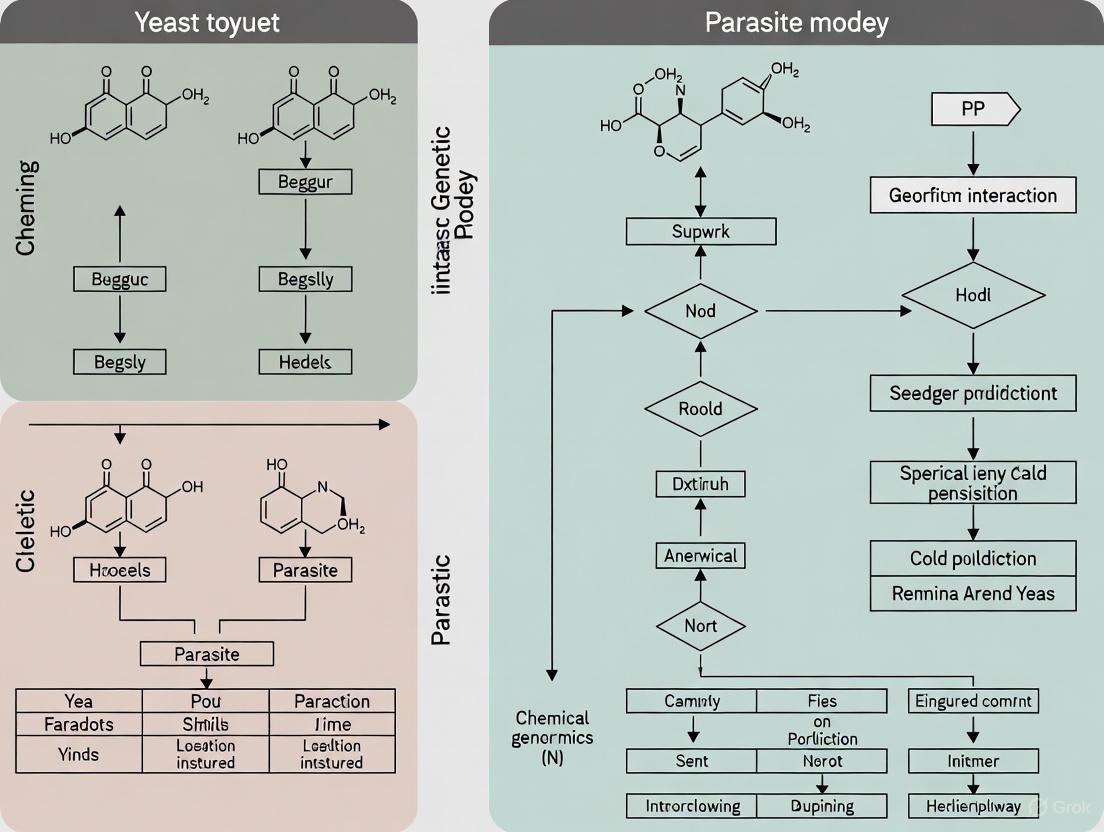

Figure 1: Parallel approaches in chemical genomics research

Forward chemogenomics begins with a phenotypic screen where the molecular mechanism is unknown [2]. Researchers identify small molecules that produce a desired phenotype in cells or whole organisms, then use these active compounds as tools to identify the protein targets responsible for the observed phenotype [2]. For example, a forward screen might seek compounds that arrest tumor growth, then work backward to identify the specific proteins these compounds bind to achieve this effect. The main challenge in forward chemogenomics lies in designing phenotypic assays that efficiently lead from screening to target identification [2].

Reverse chemogenomics starts with a known protein target and aims to identify small molecules that perturb its function in vitro [2]. Once modulators are identified, researchers analyze the phenotypes induced by these molecules in cellular or whole-organism contexts to confirm the biological role of the targeted protein [2]. This approach essentially enhances traditional target-based drug discovery through parallel screening and the ability to perform lead optimization across multiple targets within the same protein family [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Forward and Reverse Chemogenomics Approaches

| Aspect | Forward Chemogenomics | Reverse Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Phenotype of interest | Known protein target |

| Screening Approach | Phenotypic assays in cells or organisms | Target-based in vitro assays |

| Primary Challenge | Target identification after compound discovery | Phenotypic validation after target engagement |

| Typical Applications | Pathway discovery, novel target identification | Target validation, lead optimization |

| Throughput Potential | Lower (complex phenotypic readouts) | Higher (standardized binding/activity assays) |

Key Methodologies and Experimental Platforms

High-Throughput Screening and Chemical Libraries

The foundation of chemical genomics research rests on access to diverse collections of chemical compounds and robust screening methodologies. Modern pharmaceutical companies maintain chemical libraries numbering in the millions of compounds, assembled through decades of drug discovery efforts and supplemented with natural products from diverse sources [1]. The U.S. National Institutes of Health's Molecular Libraries Program (MLP) significantly advanced this field by establishing screening centers that brought systematic small-molecule screening into academic settings, ultimately building a library of approximately 390,000 compounds [6]. These collections include both synthetic compounds and novel structures derived from diversity-oriented synthesis (DOS), which have yielded small-molecule probes that would not have been discovered otherwise [6].

High-throughput screening (HTS) technologies form the operational backbone of chemical genomics. The MLP developed innovative screening approaches such as fluorescence polarization for activity-based protein profiling (fluopol-ABPP), which enables substrate-free screening of enzymes even when their natural substrates are unknown [6]. This technology uses broadly reactive ABPP probes in competition experiments to identify small molecules that selectively reduce labeling of desired enzyme targets, overcoming previous throughput limitations that restricted this approach to evaluating only a few hundred compounds [6].

Yeast Deletion Mutant Array Screening

The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae provides an exceptionally powerful platform for chemical-genetic interaction mapping due to the availability of a complete collection of approximately 6,000 gene deletion mutants [4]. This collection enables systematic detection of chemical-gene interactions, revealing genes necessary for tolerating chemical stress. The protocol for identifying these interactions involves a multi-step process centered on the deletion mutant array (DMA).

Figure 2: Workflow for yeast chemical-genetic interaction screening

The yeast screening protocol begins with determining an appropriate growth-inhibitory dose of the compound being tested [4]. Researchers prepare solid agar media containing varying concentrations of the chemical, then plate wild-type yeast cells to identify a sub-lethal concentration that inhibits growth by approximately 10-15% [4]. This optimal concentration is then used for the full-scale screen to ensure detectable synthetic sick or synthetic lethal interactions without completely suppressing growth.

For the primary screen, the deletion mutant array is condensed from a standard density of 384 colonies per plate to a high-density 1,536-colony format, enabling efficient screening of the entire collection [4]. The condensed array is replica-plated onto media containing the test compound at the predetermined concentration, with control plates containing only vehicle [4]. Following incubation, plates are imaged at high resolution, and colony sizes are quantified using specialized software such as Balony, SGAtools, or ScreenMill [4]. Strains showing significantly reduced growth in the presence of the compound compared to controls represent potential chemical-genetic interactions, which must then be validated through independent assays such as spotting assays and PCR confirmation of strain identity [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Chemical Genomics Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function and Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Libraries | Diverse collections of small molecules for screening | MLP library (~390,000 compounds) [6]; DOS-derived compounds [6] |

| Yeast Deletion Collection | Comprehensive set of gene deletion mutants for systematic screening | ~6,000 gene deletion mutants [4]; available as haploids and diploids from commercial sources [4] |

| Activity-Based Probes | Chemical tools for profiling enzyme activity in complex proteomes | Fluopol-ABPP probes for serine hydrolases [6] |

| Target Engagement Assays | Methods to confirm direct binding of compounds to cellular targets | CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) [7] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Software for data analysis and pattern recognition | Balony, SGAtools, ScreenMill for colony quantification [4] |

Applications in Model Systems: Yeast and Parasites

Elucidating Gene Function and Pathways in Yeast

Chemical-genetic interaction screening in yeast has proven particularly valuable for understanding essential biological processes, with the cell division cycle representing a paradigmatic example. Researchers have employed quantitative high-throughput phenotyping of cell cycle mutants to generate reliable genetic interaction maps [8]. One study quantitatively estimated 630 genetic interactions between 36 cell-cycle genes through extensive replication, identifying 29 high-confidence synthetic lethal interactions [8]. This dataset enabled refinement of mathematical models of cell cycle regulation, demonstrating how chemical-genetic approaches can constrain and inform computational models of complex biological networks.

The power of yeast chemical genetics lies in its ability to reveal functional relationships between genes and pathways. Chemical perturbations of genetic networks mimic gene deletions, and querying growth-inhibitory compounds against a high-density array of deletion strains for hypersensitivity identifies chemical-genetic interaction profiles [4]. Because compounds with similar mechanisms of action produce similar chemical-genetic interaction profiles, comparing these profiles against large-scale synthetic genetic interaction datasets enables inference of mechanism of action for uncharacterized compounds [4]. This approach has illuminated diverse cellular processes, from nuclear RNA processing and DNA repair in response to 5-fluorouracil [4] to diphthamide biosynthesis, where chemogenomics based on cofitness data identified the missing enzyme responsible for the final step in this pathway [2].

Chemical Genomic Approaches in Parasite Research

Parasitic organisms present unique challenges for genetic studies due to difficulties in genetic manipulation, absence of RNAi machinery in some species, and the essential nature of many virulence genes [3]. Chemical genomics offers powerful alternative strategies for studying gene function and identifying therapeutic targets in these systems. In the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, combining chemical treatment with genome-wide expression analysis has enabled construction of gene interaction networks and functional prediction of previously uncharacterized genes [3]. For example, treatment with sphingolipid analogue PPMP followed by microarray transcriptional analysis identified a protein necessary for tubovesicular network assembly [3].

Genomic studies of parasitic nematodes like Heligmosomoides bakeri have revealed how host-parasite interactions shape parasite genomes [5]. These parasites contain hyper-divergent haplotypes enriched for proteins that interact with the host immune response, with many haplotypes originating prior to the divergence between H. bakeri and H. polygyrus (at least one million years ago) [5]. The maintenance of these haplotypes over evolutionary timescales suggests they have been preserved by long-term balancing selection, likely driven by host immune pressure [5]. This discovery highlights the value of chemical genomic approaches for understanding host-parasite coevolution and identifying parasite vulnerabilities that could be exploited therapeutically.

Integration with Modern Drug Discovery

Chemical genomics has transitioned from a basic research tool to an integral component of modern drug discovery pipelines. The Molecular Libraries Program produced 375 small-molecule probes covering diverse target classes, including kinases, GPCRs, GTPases, proteases, and RNA-binding proteins [6]. These probes have directly catalyzed therapeutic development efforts across multiple disease areas, with several examples advancing to clinical development [6].

Table 3: Translation of Chemical Genomics Probes to Therapeutic Development

| Target/Pathway | MLP Probe | Therapeutic Development Trajectory |

|---|---|---|

| Serine Hydrolases | ML081, ML174, ML211, ML225, ML226, ML256, ML257, ML294, ML295, ML296 | Screening platforms and inhibitors licensed to Abide Therapeutics for neurological, immunological, and metabolic diseases [6] |

| S1P1 Receptor | ML007 | Licensed to Receptos; clinical candidate RPC1063 in Phase III studies for multiple sclerosis and ulcerative colitis [6] |

| M4 Muscarinic Receptor | ML108, ML253 | Licensed to AstraZeneca for preclinical development for neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's and schizophrenia [6] |

| p97 AAA ATPase | ML240 | Licensed to Cleave BioSciences; derivative CB-5083 in Phase I studies for multiple myeloma and solid tumors [6] |

Contemporary drug discovery increasingly integrates chemical genomic approaches with advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, in silico screening, and target engagement assays [7]. AI-guided retrosynthesis and scaffold enumeration accelerate hit-to-lead optimization, reducing discovery timelines from months to weeks [7]. Meanwhile, techniques like CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) provide quantitative validation of target engagement in physiologically relevant environments, helping bridge the gap between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy [7]. These technological advances enhance the predictive power of chemical genomic approaches and strengthen their impact on therapeutic development.

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The evolving landscape of chemical genomics and genetics continues to expand with emerging technologies and datasets. Forward-looking approaches include the integration of multi-omics data, three-dimensional structural information, and artificial intelligence to predict chemical-gene interactions with increasing accuracy [7]. The growing availability of chemogenomic reference databases, such as the expression profiles for 300 diverse mutations and chemical treatments in budding yeast, enables pattern matching to identify pathways perturbed by novel compounds [3]. As these resources expand, they will enhance the predictive power of chemical genomic approaches.

The application of chemical genomics to parasite research holds particular promise for addressing global health challenges. The ability to use small molecules to conditionally perturb essential genes in parasites lacking RNAi machinery provides a powerful alternative to traditional genetic methods [3]. Combining high-throughput chemical screening with genome-wide association studies and genomic editing techniques in parasites like Plasmodium falciparum can accelerate the identification of novel drug targets and resistance mechanisms [3]. Furthermore, the discovery of ancient, balanced polymorphisms in parasite genes interacting with host immunity [5] suggests new strategies for therapeutic intervention that account for evolutionary constraints on parasite genomes.

In conclusion, chemical genomics and genetics represent a unifying framework that bridges chemistry and biology through the systematic use of small molecules as probes of biological function. The application of these approaches in yeast and parasite models has yielded fundamental insights into gene function, pathway organization, and host-parasite interactions while simultaneously accelerating the development of novel therapeutic strategies. As chemical genomic methodologies continue to evolve and integrate with emerging technologies, they will undoubtedly remain essential tools for deciphering biological complexity and addressing human disease.

Why Yeast? Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a Pioneering Model System

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, commonly known as baker's or brewer's yeast, has been a cornerstone of biological research for decades. Its transition from a domestic staple to a powerful model organism has catalyzed breakthroughs in genetics, molecular biology, and functional genomics [9]. For researchers investigating chemical-genetic interactions and developing therapies against parasitic diseases, S. cerevisiae offers an unparalleled combination of experimental tractability, functional conservation, and systems-level resources.

The Fundamental Advantages of Yeast as a Model Organism

The utility of S. cerevisiae in modern research is built upon a foundation of key biological and experimental characteristics.

Table 1: Core Advantages of S. cerevisiae as a Model System

| Feature | Description | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid Growth | Short generation time (~90 minutes) in defined media. | Enables high-throughput genetics and rapid experimental turnaround. |

| Genetic Tractability | Well-established methods for gene deletion, tagging, and manipulation. | Simplifies reverse genetics (from gene to phenotype). |

| Conservation | 20-30% of yeast genes have human homologs; 45% of its genome is replaceable with a human gene [10]. | Findings are often translatable to human cellular processes and disease. |

| Haploid Life Cycle | Existence as stable haploid or diploid cells. | Recessive mutations are readily expressed in haploids, simplifying genetic analysis. |

| Ease of Cultivation | Low-cost, non-fastidious growth requirements. | Reduces operational costs and allows for scalable screening platforms. |

Furthermore, S. cerevisiae was the first eukaryotic organism to have its genome completely sequenced, a milestone achieved in 1996 [9]. This provided an essential reference for comparing genes across higher eukaryotes and cemented its role in functional genomics.

The Yeast Toolkit for Chemical-Genetic Interaction Studies

A primary reason for yeast's pioneering status is the development of comprehensive, community-accessible genomic tools. The yeast deletion project created a seminal resource: a systematic collection of ~6,000 strains, each with a single gene deleted from the start to stop codon and replaced with a KanMX cassette [9]. This collection allows for the systematic screening of non-essential genes.

The power of this toolkit is exemplified in chemical-genetic interaction screens. In these assays, a library of compounds is screened against a diverse set of yeast deletion strains (sentinels). A chemical-genetic interaction occurs when a specific gene deletion strain shows enhanced sensitivity or resistance to a compound compared to the wild type [11] [12]. This pinpoints cellular pathways affected by the compound and can reveal a compound's mechanism of action.

Table 2: Key Community Resources for Yeast Research

| Resource Name | Description | Key Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Deletion Collection | A complete set of ~6,000 strains, each with a single gene deletion. | Genome-wide fitness profiling, synthetic genetic array (SGA) analysis. |

| SGD (Saccharomyces Genome Database) | Central repository of curated genetic and molecular biological information [13]. | Gene annotation, literature mining, data integration. |

| Yeast GFP Fusion Localization Database | Repository for the subcellular localization of GFP-tagged proteins [13]. | Determining protein localization and trafficking. |

| Euroscarf | Central archive for the distribution of yeast deletion strains and plasmids [13]. | Sourcing key reagents for genetic studies. |

| ChemGRID | A web portal for analyzing chemical-genetic and chemical-chemical interaction data [11]. | Identifying synergistic drug combinations and cryptagens. |

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Chemical-Genetic Screening

The methodology for generating a chemical-genetic interaction matrix is a key protocol in the field [11]:

- Strain Array Preparation: A collection of "sentinel" yeast deletion strains (e.g., 242 strains representing diverse biological processes) is arrayed in 96- or 384-well microplates.

- Compound Library Handling: Libraries of chemical compounds (e.g., 5,000+ unique structures) are prepared as 1-10 mM stocks in DMSO.

- Robotic Screening: A liquid handling workstation transfers compounds into the assay plates containing yeast cultures. Final compound concentrations typically range from 10-20 µM. Controls include a solvent-only (DMSO) well and a positive inhibition control (e.g., cycloheximide).

- Growth Phenotyping: Plates are incubated at 30°C until control cultures reach saturation (~18 hours). Cell density is quantified by measuring optical density at 600 nm (OD600).

- Data Analysis: Raw OD data is normalized to plate medians and DMSO controls. Z-scores for growth inhibition are calculated based on the median and interquartile range (IQR). Compounds that inhibit the growth of a specific subset of deletion strains are classified as cryptagens (or "dark chemical matter") [11] [12].

Diagram 1: Workflow for chemical-genetic interaction screening.

Yeast as a Surrogate System for Parasite Research

The conservation of core eukaryotic pathways makes yeast an excellent surrogate for studying pathogens that are difficult or dangerous to culture. This is particularly valuable in parasitology. The experimental strategy involves "humanizing" or "parasitizing" yeast by replacing an essential yeast gene with its human or parasite ortholog. The viability of these engineered strains then depends on the function of the foreign gene, creating a platform for drug screening and functional analysis.

Case Study: Screening for Antimalarial Compounds

Plasmodium vivax, a major malaria parasite, requires new therapeutic targets. The enzyme deoxyhypusine synthase (DHS), which is essential in eukaryotes, has been explored in yeast.

Experimental Protocol: Target-Based Screening for P. vivax DHS Inhibitors [14]

- Strain Engineering: Generate two engineered S. cerevisiae strains:

- A control strain where the native yeast DHS gene is replaced with the human DHS ortholog (HsDHS).

- A screening strain where the native yeast DHS gene is replaced with the P. vivax DHS ortholog (PvDHS).

- Validation: Confirm that the heterologous DHS genes rescue the lethality of the yeast dhsΔ mutation.

- Screening: Screen chemical libraries (e.g., via virtual screening of databases like ChEMBL-NTD or robotized screening of the Pathogen Box library) against both strains.

- Hit Identification: Identify "hit" compounds that preferentially inhibit the growth of the PvDHS strain while having little effect on the HsDHS strain.

- Mechanistic Confirmation: Use Western blot analysis to confirm that the hit compounds reduce eIF5A hypusination (the downstream modification catalyzed by DHS) in the PvDHS strain.

- Validation: Test the efficacy and cytotoxicity of hits against cultured Plasmodium parasites and mammalian cells.

This platform successfully identified compounds that selectively targeted PvDHS, showed antiplasmodial activity in the nanomolar to micromolar range, and exhibited low cytotoxicity [14].

Diagram 2: Yeast surrogate platform for antimalarial discovery.

Case Study: Modeling Mitochondrial Function in Plasmodium

The mitochondrion of Plasmodium falciparum is a major drug target due to its structural and functional differences from the human organelle. S. cerevisiae serves as a powerful model for studying mitochondrial function and for screening mitochondrial-targeting compounds [15].

- Metabolic Versatility: Yeast metabolism can be shifted between glycolytic and respiratory states by modulating growth conditions (e.g., carbon source, oxygen levels). This allows researchers to simulate the distinct metabolic states of different Plasmodium life cycle stages [15].

- Genetic Accessibility: Yeast enables functional characterization of Plasmodium mitochondrial proteins through heterologous expression. This helps in validating drug targets and elucidating mechanisms of action for known antimalarials like atovaquone [15].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents that are fundamental to conducting advanced yeast-based research, particularly in chemical-genetic and parasitology studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Yeast Chemical Genetics

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Research | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Deletion Strain Collections | Provides a genome-wide set of mutants for phenotypic screening. | Euroscarf deletion collection (BY4741 background) [13]. |

| Gateway-Compatible Plasmids | Facilitates rapid cloning and heterologous expression of genes. | Plasmids for GAL1/10-inducible expression of bacterial effectors [13]. |

| Yeast Bioactive Compound Libraries | Curated collections of chemicals with known or predicted bioactivity in yeast. | Bioactive 1 & 2 libraries used for chemical-genetic screens [11]. |

| Heterologous Expression Cassettes | Allows for the replacement of yeast genes with human or pathogen orthologs. | Cassettes for expressing HsDHS or PvDHS in place of yeast DYS1 [14]. |

| Reporter Tags | Enables protein localization and quantification. | GFP fusions for localization; mCherry/Sapphire for fluorescent growth assays [13] [14]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Enables precise genome editing for strain engineering. | Used to create point mutations, gene knockouts, and chromosome rearrangements [16]. |

Saccharomyces cerevisiae remains a pioneering model system due to its unique synergy of genetic tractability, functional genomic resources, and profound conservation of eukaryotic core processes. The development of high-throughput chemical-genetic interaction screens has transformed it into a predictive platform for understanding drug mechanism of action and discovering synergistic combinations. Furthermore, by serving as a testbed for human and pathogen genes, yeast provides a cost-effective, scalable, and powerful surrogate system for functional variant characterization and antiparasitic drug discovery, directly accelerating the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Chemical genetics, the use of small molecules to perturb and study protein function in living systems, has emerged as a powerful platform for bridging fundamental biological discovery with therapeutic development [17]. This approach operates on two complementary fronts: forward chemical genetics, which involves screening small molecule libraries for a desired phenotypic effect and subsequently identifying the cellular target, and reverse chemical genetics, which begins with a specific protein target and seeks compounds that modulate its activity [1] [17]. For the study of parasitic diseases, chemical genetics provides uniquely powerful tools to dissect infection mechanisms and identify new drug targets in pathogens that are often genetically intractable or require complex host interactions [18] [3].

The core strength of this methodology lies in its conditional and reversible nature. Small molecules can be added or removed at will, enabling kinetic analysis of protein function disruption that is often impossible with conventional genetic knockouts, especially for essential genes [1]. This is particularly valuable for studying parasitic organisms, where experimental methods typically lag behind model systems and there are few "off-the-shelf" approaches for direct study [18]. By utilizing model organisms like yeast as intermediate testing grounds, researchers can gain crucial insights into drug mechanisms and resistance pathways that are directly relevant to human parasitic infections [19].

Foundational Principles of Chemical Genetics

The theoretical underpinnings of chemical genetics rest on two fundamental principles established over centuries of research: first, that pure biologically active substances can be obtained from natural sources or synthetic libraries, and second, that these substances exert their effects by binding to specific molecular targets within an organism [1]. Paul Ehrlich's concept of a "receptor" as the specific protein target of a small molecule was a crucial breakthrough that laid the groundwork for modern chemical genetics [1].

Parallels Between Classical and Chemical Genetics

Chemical genetics mirrors the approach of classical forward genetic screens but uses small molecules as perturbation tools rather than mutations. The typical workflow involves three key steps [1]:

- Assembling diverse ligands capable of altering protein function (equivalent to random mutagenesis)

- Screening for ligands that affect a biological process of interest (equivalent to mutant identification)

- Identifying protein targets of active ligands (equivalent to gene identification)

Unlike genetic mutations, small molecules offer temporal control, reversibility, and the ability to titrate effect strength simply by varying concentration [3] [1]. This allows researchers to study essential genes whose complete disruption would be lethal and to analyze the immediate consequences of protein function alteration in a complex cellular environment [1].

The Yeast-Parasite Bridge in Chemical Genetics

The yeast model system Saccharomyces cerevisiae has proven exceptionally valuable as an intermediate bridge in chemical genetics studies of parasitic diseases [10] [19]. Despite phylogenetic distance from humans, yeast shares more than 2,000 genes (approximately 30% of its genome) with humans, and 45% of its genome is replaceable with human genes [10]. This conservation enables researchers to use yeast as a genetically tractable surrogate for studying targets of anti-parasitic compounds.

A prime example is the study of the spiroindolone antimalarial KAE609 (cipargamin). When resistance to this compound was studied in yeast, mutations were found in ScPMA1, a P-type ATPase and homolog of the Plasmodium falciparum protein PfATP4, which had previously been identified as a KAE609 resistance factor in malaria parasites [19]. This cross-organism validation provided strong evidence that PfATP4 is the direct target of KAE609 rather than merely a multidrug resistance gene. Subsequent experiments demonstrated that KAE609 directly inhibits ScPma1p ATPase activity in a cell-free assay and increases cytoplasmic hydrogen ion concentrations in yeast cells, mirroring its effects on sodium homeostasis in parasites [19].

Diagram 1: The Yeast-Parasite Bridge Workflow. This pathway illustrates how yeast models enable target identification for anti-parasitic compounds.

Technical Approaches and Methodologies

Modern chemical genetics leverages an integrated toolkit of high-throughput technologies, genomic methods, and computational analyses to systematically probe gene function and compound mechanism of action.

High-Throughput Screening Platforms

High-throughput screening (HTS) of chemical libraries forms the foundation of forward chemical genetics. Recent advances have dramatically increased the scale and precision of these approaches. Quantitative and Multiplexed Analysis of Phenotype by Sequencing (QMAP-Seq) represents a particularly powerful development that enables pooled high-throughput chemical-genetic profiling in mammalian cells [20]. This method combines CRISPR-Cas9 genetic perturbations with barcoding strategies to quantitatively measure how dozens of genetic variants affect cellular response to hundreds of compound-dose combinations in parallel [20].

The QMAP-Seq workflow involves [20]:

- Engineering barcoded cell lines with inducible genetic perturbations

- Pooled treatment with compound-dose combinations

- Introduction of spike-in cell standards for quantification

- Multiplexed sequencing and computational analysis to determine relative cell abundance

This approach has been used to generate 86,400 chemical-genetic measurements in a single experiment, identifying both sensitivity interactions (synthetic lethality) and resistance interactions (synthetic rescue) between genetic variants and compound treatments [20].

Target Identification Methods

Once bioactive compounds are identified through phenotypic screens, the critical challenge becomes target identification. Multiple genome-wide approaches have been developed for this purpose:

- Chemical transcriptomics: Using microarrays or RNA-seq to detect transcriptional changes after compound treatment, then comparing expression profiles to databases of known perturbations to infer affected pathways [3]

- Haploinsufficiency profiling: Screening heterozygous deletion strains in yeast; reduced expression of a drug target often increases susceptibility to compounds targeting that protein [18]

- Resistance mutation analysis: Selecting for compound-resistant mutants and identifying mutated genes through whole-genome sequencing [19]

- Affinity purification: Using modified versions of active compounds to pull down direct binding partners from cell lysates [3]

- Chemoproteomics: Using compound analogs with affinity handles to capture and identify protein targets through mass spectrometry [18]

Each method has strengths and limitations, so orthogonal approaches are often combined to build confidence in target identification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Chemical-Genetic Studies of Parasitic Diseases

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Libraries | Diverse collections of small molecules for phenotypic screening; source of "mutation equivalents" | Combinatorial chemistry libraries; natural product collections [1] |

| Genetically Tractable Model Systems | Surrogate organisms for target identification and mechanism studies | S. cerevisiae ABC16-Monster strain (lacking 16 ABC transporters) [19] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Tools | Precise genetic perturbation in mammalian and parasite systems | Inducible Cas9 systems for temporal control of gene knockout [20] |

| Barcoded Vector Systems | Enables pooling and tracking of multiple genetic variants in parallel screens | lentiGuide-Puro with unique 8bp cell line barcodes [20] |

| Cell Viability Reporters | Quantitative measurement of compound efficacy and genetic interactions | pH-sensitive fluorescent proteins (pHluorin), ATP-based assays [19] [20] |

| Spike-In Standards | Internal controls for quantitative sequencing approaches | 293T cells with unique sgRNA barcodes for QMAP-Seq [20] |

Application to Parasitic Disease Research

Chemical genetics approaches have yielded significant insights into diverse parasitic pathogens, from Apicomplexan parasites to parasitic worms and fungi.

Case Studies in Major Parasitic Pathogens

Table 2: Chemical-Genetic Insights into Parasitic Diseases

| Pathogen/Disease | Chemical-Genetic Approach | Key Finding | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptosporidium parvum (Cryptosporidiosis) | Chemoproteomics followed by knockdown, overexpression, and site-directed mutagenesis [18] | Identified tRNA-synthetase as target of potent antiparasitic inhibitor [18] | Expanded set of selectable markers and drug targets in C. parvum [18] |

| Plasmodium & Babesia (Malaria & Babesiosis) | Screen of host-targeted inhibitors against parasites [18] | Identified micromolar-potency inhibitors among host red blood cell-targeting compounds [18] | Potential for repurposing host-targeted drugs for antiparasitic therapy [18] |

| Candida auris (Fungal Infection) | Haploinsufficiency profiling in C. albicans followed by fatty acid supplementation [18] | Fatty acid desaturase Ole1 identified as target of aryl-carbohydrazide inhibitor [18] | Compound improved survival in moth larva model of systemic candidiasis [18] |

| Fasciola spp. (Fascioliasis) | Comparative biochemistry and chemical inhibition [18] | Juvenile and adult worms utilize different mitochondrial respiration modes [18] | Developmental stage-specific targeting opportunities [18] |

Integrated Workflow for Parasite Chemical Genetics

Diagram 2: Integrated Parasite Drug Discovery Pipeline. This workflow combines phenotypic screening in parasites with target identification in yeast models.

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol: Target Identification Using Yeast as a Surrogate Model

This protocol adapts the approach used to identify PfATP4 as the target of the antimalarial KAE609 [19]:

- Strain Selection: Use engineered yeast strains deficient in drug efflux pumps (e.g., ABC16-Monster strain lacking 16 ABC transporters) to increase compound sensitivity [19].

- Resistance Selection: Culture cells in increasing concentrations of the anti-parasitic compound. Typically, 2-5 rounds of selection with step-wise concentration increases are required for resistance to emerge [19].

- Whole-Genome Sequencing: Prepare genomic DNA from resistant clones and parent strain. Sequence with >40-fold coverage using Illumina or similar platform. Identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and copy number variants (CNVs) by comparison to parent [19].

- Genetic Validation: Use CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce identified mutations into naive strain. Confirm that introduced mutations confer resistance phenotype [19].

- Functional Validation:

- Test specificity by profiling resistance against unrelated compounds

- Assess fitness cost by measuring growth under various conditions

- For membrane targets, measure ion homeostasis or similar physiological parameters [19]

- Cross-Species Validation: Confirm homologous target role in parasite using genetic approaches specific to the pathogen (e.g., directed evolution in Plasmodium) [19].

Protocol: High-Throughput Chemical-Genetic Interaction Mapping in Mammalian Cells

This protocol is based on the QMAP-Seq method for quantitative chemical-genetic profiling [20]:

Cell Line Engineering:

- Design sgRNA library targeting genes of interest (e.g., proteostasis network factors)

- Clone sgRNAs into barcoded lentiviral vectors with unique 8bp cell line barcodes

- Engineer doxycycline-inducible Cas9 system for temporal control of knockout

Pooled Screen Setup:

- Induce Cas9 expression with doxycycline 96 hours before compound treatment

- Pool all genetically variant cell lines in predetermined ratios

- Treat pooled cells with compound-dose combinations in duplicate (include DMSO controls)

- Incubate for 72 hours

Sample Processing and Sequencing:

- Prepare crude cell lysates

- Add spike-in standards (293T cells with unique sgRNA barcodes) in numbers covering expected cell number range

- Amplify samples using unique i5 and i7 indexed primers

- Pool PCR products and sequence with single-read run to sequence sgRNA and cell line barcodes

Computational Analysis:

- Demultiplex sequences according to index combinations

- Extract and count cell line and sgRNA barcodes

- Use spike-in standards to generate sample-specific standard curves

- Calculate relative cell numbers for each genotype in compound vs. DMSO control

- Identify chemical-genetic interactions as significant deviations from expected fitness

The integration of chemical genetics with model systems like yeast provides a powerful framework for understanding parasitic diseases and developing new therapeutics. As these approaches continue to evolve, several promising directions are emerging. The application of multiplexed technologies like QMAP-Seq to parasite systems themselves, rather than just model organisms, could dramatically accelerate target discovery [20]. Additionally, the systematic mapping of genetic interaction networks in parasites would provide a rich resource for understanding gene function and identifying synthetic lethal interactions that could be exploited therapeutically [21].

Chemical genetics has already demonstrated its value in bridging basic science and therapeutic development for parasitic diseases. The identification of PfATP4 as the target of spiroindolones [19], tRNA-synthetases as targets in Cryptosporidium [18], and Ole1 as a target in Candida auris [18] all exemplify how this approach can reveal both new biology and new therapeutic opportunities. As the tools for genetic manipulation in parasites continue to improve and chemical screening methodologies become more sophisticated, chemical genetics is poised to play an increasingly central role in the fight against parasitic diseases.

Genetic Interactions, Synthetic Lethality, and Suppression

Genetic interactions occur when combinations of genetic perturbations result in unexpected phenotypes that deviate from the null expectation of independent gene function. These interactions reveal the functional organization and robustness of cellular networks and provide powerful tools for functional genomics and therapeutic discovery [22] [23]. In quantitative terms, a genetic interaction is typically measured by comparing the observed fitness of a double mutant (f~12~) to the product of the corresponding single-mutant fitness values (f~1~·f~2~). The interaction score (ε) is calculated as ε = f~12~ - f~1~·f~2~, where significant negative deviations indicate aggravating (synthetic sick/lethal) interactions and positive deviations indicate alleviating (suppressive) interactions [24].

The systematic mapping of genetic interactions has been particularly powerful in model organisms like Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where approximately 80% of genes are non-essential for viability in rich media, yet most single mutants show sensitivity to additional perturbations [22]. This genetic robustness stems from various buffering mechanisms, including functional redundancy, backup pathways, and capacitor proteins that conceal the effects of mutations [22] [23]. Genetic interactions are generally categorized as either negative (synthetic sick/lethal), where the double mutant shows reduced fitness, or positive (including suppression), where the double mutant shows improved fitness relative to expectations [23].

Classification and Mechanisms of Synthetic Lethality and Suppression

Synthetic Lethality: Principles and Definitions

Synthetic lethality (SL) represents the most extreme class of negative genetic interaction, occurring when simultaneous perturbation of two genes results in cell death, while perturbation of either gene alone remains viable [22] [25]. First described in Drosophila melanogaster by Calvin Bridges in 1922 and later termed by Theodore Dobzhansky in 1946, synthetic lethality has since become a fundamental concept in functional genetics and therapeutic development [22] [25]. When the combination results in reduced but not lethal fitness, the interaction is termed "synthetic sick" [22].

Synthetic lethality arises from the inherent robustness of biological systems, where essential processes are buffered against single points of failure through parallel pathways and functional backups [22]. This buffering capacity means that while ∼80% of budding yeast genes are individually dispensable for proliferation in rich medium, most single mutants are sensitive to additional perturbations [22].

Table 1: Synthetic Lethality Classification in Cancer Therapeutics

| Category | Definition | Examples | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene-Level | Direct interaction between specific gene pairs | BRCA-PARP, TP53-ATM, KRAS-GATA2 | Direct targeting of specific mutant genes |

| Pathway-Level | Interactions between parallel or compensating pathways | Homologous recombination - base excision repair | Targeting backup pathways essential in mutant backgrounds |

| Organelle-Level | Interactions affecting cellular compartment function | Mitochondrial dysfunction with proteasome inhibition | Targeting organelle-specific vulnerabilities |

| Conditional SL | Context-dependent interactions influenced by environment | Nutrient-specific sensitivities, tissue-specific dependencies | Personalized approaches considering tumor microenvironment |

Suppression: Mechanisms of Genetic Resilience

Suppression interactions represent the most extreme form of positive genetic interaction, where a secondary mutation (the "suppressor") rescues the deleterious effects of a primary "query" mutation [23] [26]. These interactions are categorized based on the nature of the suppressor mutation and its mechanistic relationship to the query mutation.

Extragenic suppression occurs between different genes and can be further classified based on the functional relationship between query and suppressor [23]:

Within-complex suppression: Suppressor and query genes encode members of the same protein complex (~5-10% of suppression interactions) [23]. For example, partial loss-of-function mutations in DNA polymerase δ subunit Pol31 can be suppressed by gain-of-function mutations in the catalytic subunit POL3 [23].

Same-pathway suppression: Suppressor and query operate within the same biological pathway, potentially compensating for specific functional defects [23].

Alternative pathway suppression: The suppressor activates an alternative pathway that bypasses the functional defect caused by the query mutation [23].

General mechanisms: Include informational suppression (affecting transcription or translation), altered protein expression, or improved stability of mutant proteins [23].

Dosage suppression occurs when overexpression of a suppressor gene rescues a mutant phenotype, typically indicating that the suppressor protein can compensate for the functional defect when present at elevated levels [23].

Table 2: Frequency of Suppression Mechanisms in Yeast

| Mechanistic Class | Genomic Suppression (%) | Dosage Suppression (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Mechanisms | 52.7 | 65.0 |

| Same complex | 6.9 | 19.3 |

| Same pathway | 10.5 | 7.7 |

| Alternative pathway | 7.8 | 5.4 |

| Unknown functional connection | 27.5 | 32.6 |

| General Mechanisms | 11.0 | 9.5 |

| Protein expression | 7.0 | 6.3 |

| Protein stability | 4.0 | 3.2 |

| Unknown Mechanism | 36.3 | 25.5 |

Experimental Approaches in Model Systems

High-Throughput Mapping in Yeast

The synthetic genetic array (SGA) methodology enables systematic construction of double mutants for high-throughput genetic interaction mapping [24] [8]. In a typical SGA screen, an array of ~470 null mutants is crossed against ~613 query mutants, generating double mutants for ~184,000 unique gene pairs [24]. Fitness is quantitatively assessed by measuring colony size, and interaction scores are calculated based on deviation from expected double-mutant fitness [24].

For essential genes, hypomorphic alleles (partial loss-of-function) are used to enable genetic interaction mapping. The resulting interaction networks provide quantitative insights into functional relationships between genes, with negative interactions often indicating compensatory pathways and positive interactions suggesting functional concordance [24].

Recent advancements have improved the reproducibility of synthetic lethal screens through extensive biological replication. One study quantitatively estimated 630 genetic interactions between 36 cell-cycle genes through high-throughput phenotyping with unprecedented replication, identifying 29 high-confidence synthetic lethal interactions [8]. This approach highlighted the substantial variability in synthetic lethal identification, with no gene combination producing identical results across all replicates, emphasizing the need for rigorous statistical thresholds in defining genuine interactions [8].

Chemical-Genetic Profiling in Mammalian Systems

Quantitative and Multiplexed Analysis of Phenotype by Sequencing (QMAP-Seq) represents a recent innovation for chemical-genetic interaction profiling in mammalian cells [20]. This approach leverages next-generation sequencing for pooled high-throughput chemical-genetic profiling, enabling systematic measurement of how cellular stress response factors affect therapeutic response in cancer.

In a proof-of-concept application, QMAP-Seq was used to treat pools of 60 cell types—comprising 12 genetic perturbations in five cell lines—with 1,440 compound-dose combinations, generating 86,400 chemical-genetic measurements [20]. The method produced precise quantitative measures of acute drug response comparable to gold standard assays while offering increased throughput at lower cost [20].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Genetic Array (SGA) | Automated construction of double mutants | Genome-wide genetic interaction mapping in yeast [24] |

| LentiGuide-Puro Plasmid | Delivery of sgRNA and selection marker | CRISPR-based gene knockout in mammalian cells [20] |

| Doxycycline-inducible Cas9 | Temporal control of gene knockout | Essential gene knockout without constitutive toxicity [20] |

| Cell Line Barcodes | Unique identification of cell populations | Multiplexed screening of multiple genetic backgrounds [20] |

| Spike-in Standards | Normalization for quantitative sequencing | Accurate cell number estimation in pooled screens [20] |

| haploid yeast deletion collection | Comprehensive set of null mutants | Systematic genetic interaction studies [8] |

Applications in Disease Research and Therapeutic Development

Cancer Therapeutics and Synthetic Lethality

The most prominent clinical application of synthetic lethality is in cancer treatment, particularly through PARP inhibitors for BRCA1/2-mutant tumors [22] [25] [27]. BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins are essential for homologous recombination DNA repair, while PARP enzymes are crucial for base excision repair. Inhibiting PARP in BRCA-deficient cells leads to accumulation of unrepaired DNA damage and selective cancer cell death [22] [27].

This approach has led to FDA approval of PARP inhibitors for breast, ovarian, and prostate cancers with BRCA mutations, demonstrating the clinical viability of synthetic lethality [25] [27]. The success of PARP inhibitors has stimulated research to identify synthetic lethal partners for other cancer-relevant genes, including TP53, KRAS, and MYC, which have proven challenging to target directly [27].

Beyond DNA repair, synthetic lethal approaches are being explored for other cancer vulnerabilities. For example, tumors with defective protein folding capacity may be sensitive to proteasome inhibitors, while those with altered metabolism may show selective sensitivity to metabolic inhibitors [22] [20]. The expanding classification of synthetic lethality includes gene-level, pathway-level, organelle-level, and conditional synthetic lethality, reflecting the diverse mechanisms that can be therapeutically exploited [27].

Suppression Networks in Disease Resilience

Systematic analysis of suppression interactions in human genetics has revealed a network of 476 unique suppression interactions covering a wide spectrum of diseases and biological functions [26]. These interactions frequently link genes operating in the same biological process, with suppressors strongly enriched for genes involved in stress response or signaling [26].

This suggests that deleterious mutations can often be buffered by modulating signaling cascades or immune responses. Analysis of these networks has demonstrated that suppressor mutations tend to be deleterious when they occur in absence of the query mutation, contrasting with their protective role in its presence [26]. Mechanistic explanations can be formulated for 71% of documented suppression interactions, providing insight into disease pathology and potential therapeutic strategies [26].

One clinically significant example is the suppression of β-thalassemia by loss-of-function mutations in BCL11A, a transcriptional repressor of fetal hemoglobin [26]. Expression of fetal γ-globin in adults can compensate for defective β-globin, a finding that has led to the development of gene therapies targeting BCL11A [26]. This illustrates how understanding natural suppression mechanisms can inform therapeutic development.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Machine Learning and Predictive Algorithms

Machine learning approaches are being increasingly applied to predict genetic and chemical-genetic interactions based on structural features and interaction patterns [12]. In one study, a combined random forest and Naive Bayesian learner that associated chemical structural features with genotype-specific growth inhibition demonstrated strong predictive power for identifying synergistic drug combinations [12].

This approach identified previously unknown compound combinations that exhibited species-selective toxicity toward human fungal pathogens, demonstrating the utility of computational methods for discovering synergistic combinations across species [12]. However, models based solely on chemical-genetic matrices or genetic interaction networks have shown limited predictive accuracy, highlighting the importance of incorporating multiple data types and structural information [12].

Integration with Metabolic Models

Constraint-based metabolic models, such as those using flux balance analysis (FBA), can predict genetic interactions from metabolic network structure [24]. By imposing mass balance and capacity constraints to define feasible steady-state flux distributions, these models can identify optimal network states that maximize biomass yield, serving as a proxy for growth [24].

Superposing empirical genetic interaction data on detailed metabolic network reconstructions enables mechanistic interpretation of interaction patterns and model refinement [24]. For example, this integrated approach has provided mechanistic explanations for the correlation between genetic interaction degree, pleiotropy, and gene dispensability, showing that single mutants with severe fitness defects tend to engage in more genetic interactions [24].

Discrepancies between model predictions and experimental data can drive biological discovery, as demonstrated by the automated correction of misannotations in NAD biosynthesis that were subsequently validated by in vivo experiments [24]. This iterative process of model refinement and experimental validation represents a powerful approach for mapping genotype-phenotype relationships in metabolic networks.

Genetic interactions, particularly synthetic lethality and suppression, provide fundamental insights into the functional architecture of biological systems and represent promising avenues for therapeutic development. The systematic mapping of these interactions in model organisms like yeast has revealed general principles of genetic robustness and network organization, while technological advances enable increasingly sophisticated profiling in mammalian systems. As methods for detecting, interpreting, and predicting these interactions continue to evolve, they offer the potential to identify novel therapeutic strategies that exploit the genetic vulnerabilities of diseased cells while sparing normal tissues.

Phenotypic screening using small molecules (SMs) represents a powerful approach in chemical genetics for probing gene function and identifying conditional mutant phenotypes. This methodology is particularly valuable in model organisms such as yeast and parasites, where it enables the systematic investigation of gene-protein-compound interactions in a controlled manner. Chemical genetics operates on the principle that small molecules can mimic genetic mutations by disrupting specific protein functions, thereby creating conditional phenotypes that can be studied to elucidate gene function and biological pathways [28] [29]. This approach is especially useful for studying essential genes in yeast and identifying new therapeutic targets in parasite research, bridging the gap between traditional genetics and drug discovery [30].

The fundamental premise of using phenotypic screening in chemical genetics is that by exposing different mutant strains to libraries of small molecules, researchers can identify compounds that produce strain-specific phenotypic effects. These chemical-genetic interactions reveal functional information about the targeted genes and pathways, while simultaneously identifying potential therapeutic compounds [28]. In parasite models, this approach has been instrumental in antiparasitic drug discovery, where phenotypic screening remains the predominant strategy for identifying novel active compounds [30].

Core Principles and Significance

Theoretical Foundations of Chemical Genetics

Chemical genetics leverages small molecules as precise tools to modulate protein function reversibly and conditionally, analogous to traditional genetic approaches but with temporal control. This methodology operates through two complementary frameworks:

- Forward chemical genetics: Begins with screening small molecule libraries for a specific phenotype, followed by target identification

- Reverse chemical genetics: Starts with a specific protein target and identifies small molecules that modulate its function

In both frameworks, the application of small molecules to various mutant backgrounds allows for the revelation of conditional phenotypes that provide insight into gene function, compensatory pathways, and network interactions [28] [29]. The power of this approach lies in its ability to create conditional phenotypes on demand, overcoming the limitations of traditional genetic knockouts, especially for essential genes.

Advantages in Model Organism Research

The application of phenotypic screening with SMs in yeast and parasite models offers several distinct advantages for basic research and drug discovery:

Temporal Control: Small molecules enable precise temporal manipulation of protein function, allowing researchers to study stage-specific processes in parasite life cycles or time-sensitive pathways in yeast [30] [29].

Dose Dependency: Graded responses to compound concentration can reveal threshold effects and pathway vulnerabilities not apparent in binary genetic knockouts [31].

Functional Redundancy Mapping: Compound sensitivity in specific mutant backgrounds can uncover buffering relationships and redundant pathways [28].

Polypharmacology Profiling: Small molecules often interact with multiple targets, potentially revealing unexpected functional connections between pathways [32].

For parasite research specifically, phenotypic screening has been the predominant approach for antiparasitic discovery due to the frequent lack of well-validated molecular targets [30]. The unbiased nature of phenotypic screening allows for the identification of novel mechanisms of action without preconceived hypotheses about target essentiality.

Experimental Design and Workflow

Strategic Planning and Model Selection

Successful phenotypic screening requires careful consideration of biological models and screening configurations:

Table 1: Model Organisms for Chemical Genetic Screening

| Organism | Advantages | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae | Well-annotated genome; deletion mutant collections available; rapid growth [29] | Pathway analysis; target identification; mechanism of action studies [28] | Limited relevance for parasitic diseases |

| C. elegans | Multicellular complexity; surrogate for parasitic nematodes [30] | Antiparasitic screening; neurogenetics; toxicology | Lower throughput than yeast; more complex culture |

| Parasite models | Clinical relevance; direct translational potential [30] | Antiparasitic drug discovery; mode of action studies | Often difficult to culture; limited genetic tools |

The choice of model organism should align with research objectives, with yeast providing a powerful system for fundamental chemical biology and parasite models offering direct translational relevance for therapeutic development [30] [29].

Library Design and Compound Selection

The composition of the small molecule library critically influences screening outcomes. Several library design strategies have emerged:

- Diversity-oriented synthesis libraries: Maximize structural variety to increase probability of identifying novel bioactivities [28]

- Bio-focused libraries: Enriched with compounds known to modulate specific target classes or pathways [33]

- Phenotypic Screening Libraries: Specifically designed collections like the Enamine PSL with 5,760 compounds selected for optimal performance in phenotypic assays [33]

Specialized phenotypic screening libraries, such as the commercially available Enamine PSL, incorporate approved drugs, potent inhibitors, and their structural analogs with documented bioactivity, providing a valuable resource for initial screening campaigns [33]. These libraries are designed with chemical diversity and drug-like properties in mind, increasing the probability of identifying compounds with meaningful biological activity.

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Yeast Chemical Genetic Screening Protocol

The following detailed protocol adapts established methods for chemical genetic screening in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [28] [29]:

Day 1: Strain Preparation

- Inoculate yeast deletion mutant strains (e.g., from EUROSCARF collection) in 2 mL YPD medium

- Grow overnight at 30°C with shaking at 220 rpm

- Monitor culture density until OD600 reaches 0.6-0.8 (mid-log phase)

Day 2: Compound Exposure and Phenotypic Assessment

- Dilute cultures to OD600 = 0.1 in fresh YPD

- Aliquot 100 μL per well in 96-well plates

- Add small molecules from library using pin tool or liquid handler (final DMSO concentration ≤0.1%)

- Include controls: DMSO only (negative), known inhibitor (positive)

- Incubate 48 hours at 30°C without shaking

- Measure phenotypic endpoints:

- Cell viability: Resazurin reduction assay (fluorescence: λex 560/λem 590)

- Growth kinetics: OD600 measurements every 2 hours if using plate reader

- Morphological analysis: Microscopic examination at 40× magnification

Data Analysis

- Normalize data to DMSO control (100% growth) and positive control (0% growth)

- Calculate Z-factor for quality control: Z = 1 - (3σc+ + 3σc-)/|μc+ - μc-| where σ = standard deviation, μ = mean, c+ = positive control, c- = negative control

- Apply threshold for hit identification: typically >70% inhibition or <30% viability compared to control

This protocol enables the identification of strain-specific sensitivity, where certain mutants show enhanced susceptibility to specific compounds, revealing functional relationships between the targeted gene and the compound's mechanism of action [28].

Quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS)

For larger scale screening, quantitative high-throughput screening (qHTS) provides robust concentration-response data directly from primary screens [31]:

Protocol:

- Format compounds in 1536-well plates using acoustic dispensing (e.g., Echo LDV systems)

- Implement 8-point 1:3 serial dilutions directly in assay plates (typical range: 10 nM - 100 μM)

- Dispense cell suspension using multidrop dispenser (1,000 cells/well in 5 μL)

- Incubate 48-72 hours under appropriate culture conditions

- Measure viability using CellTiter-Glo luminescent assay

- Generate concentration-response curves (CRCs) for all compounds

Hit Criteria:

- Potency: IC50 ≤ 10 μM

- Efficacy: Maximal response ≥ 65% inhibition

- Data Quality: Curve fit (R² > 0.9) and presence of clear saturation

This qHTS approach was successfully applied in pediatric cancer cell lines, identifying 1,120 active compounds from 3,886 tested, demonstrating the power of phenotypic screening for drug repurposing [31].

Table 2: Quantitative High-Throughput Screening Outcomes in Pediatric Cancer Models

| Screening Parameter | Result | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Total compounds screened | 3,886 | Approved drugs + investigational agents |

| Active compounds | 1,120 (28.8%) | IC50 ≤ 10 μM & efficacy ≥ 65% |

| Pan-active compounds | 62 | Active in ≥17/19 cell lines |

| Selective compounds | 26 tumor-specific | Active in 2+ cell lines of same tumor type |

| Assay quality (Z-factor) | >0.6 | Excellent for HTS |

Computational Enhancement of Phenotypic Screening

Recent advances in computational methods have significantly enhanced phenotypic screening approaches:

DrugReflector Framework:

- Utilizes active reinforcement learning to predict compounds that induce desired phenotypic changes

- Trained on compound-induced transcriptomic signatures from Connectivity Map data

- Demonstrates an order of magnitude improvement in hit rates compared to random library screening [34]

AI-Enhanced Image Analysis:

- Machine learning algorithms extract morphological features from high-content screening images

- Enable clustering of cellular phenotypes and prediction of mechanism of action

- Platforms like Ardigen's phenAID reduce analysis time and enhance prediction quality [35]

Pathway Analysis and Mechanism Deconvolution

Metabolic Pathway Mapping in Yeast

Chemical genetic screening in yeast has proven particularly valuable for elucidating metabolic pathways and stress response mechanisms [29]. The protocol involves:

- Screening the complete yeast deletion mutant collection against compound libraries

- Identifying hypersensitive mutants through statistical analysis of growth phenotypes

- Mapping these genetic interactions to metabolic pathways using KEGG and GO enrichment

- Validating pathway involvement through secondary assays (ATP measurement, metabolite profiling)

For example, screening with the anticancer agent 3-bromopyruvate revealed its involvement in energy metabolism pathways, particularly glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, demonstrating how phenotypic screening can elucidate mechanisms of action for compounds with unknown targets [29].

Target Deconvolution Methods

Following primary phenotypic screening, identifying the molecular targets of hit compounds represents a critical challenge:

Genetic Approaches:

- Haploinsufficiency profiling: Screening heterozygous deletion strains for enhanced sensitivity

- Multicopy suppression: Identifying genes that confer resistance when overexpressed

- Resistance mutation sequencing: Isolating and sequencing spontaneous resistant mutants

Biochemical Approaches:

- Affinity purification: Using compound derivatives with affinity handles for pull-down assays

- Protein microarrays: Screening for direct binding to immobilized proteins

- Stability-based profiling: Monitoring thermal stability changes across the proteome (CETSA)

Bioinformatics Integration:

- Connectivity Map analysis: Comparing gene expression signatures to reference databases

- Chemical similarity searching: Identifying compounds with structural similarity to those with known targets

The integration of these approaches has proven successful for target deconvolution, as demonstrated with compounds like thalidomide, where cereblon was identified as the primary target through a combination of affinity purification and genetic approaches [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Deletion Collections | Comprehensive mutant libraries for chemical genetic screening | EUROSCARF collection; S. cerevisiae deletion library [29] |

| Phenotypic Screening Libraries | Curated small molecule collections optimized for phenotypic assays | Enamine PSL (5,760 compounds); NCGC Pharmaceutical Collection [33] [31] |

| High-Content Screening Systems | Automated imaging and analysis of morphological phenotypes | CellInsight; ImageXpress; InCell analyzers [35] |

| Viability Assay Reagents | Measure cell proliferation and cytotoxicity | CellTiter-Glo; Resazurin; MTT [31] |

| 3D Culture Matrices | More physiologically relevant culture conditions for validation | Matrigel; spheroid culture plates [31] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Chemical-Genetic Interaction Scoring

The interpretation of chemical-genetic screening data requires specialized analytical approaches:

Interaction Scoring:

- Calculate differential sensitivity between mutant and wild-type strains

- Normalize for general growth defects using standardized scores (S-scores)

- Apply statistical thresholds (typically Z-score > 2 or p < 0.05) for significance

Network Analysis:

- Map chemical-genetic interactions onto protein-protein interaction networks

- Identify enriched functional modules using tools like Cytoscape with enrichment plugins

- Compare interaction profiles to reference compounds with known mechanisms

Cluster Analysis:

- Group compounds with similar chemical-genetic interaction profiles

- Identify functional relationships between genes based on shared sensitivity profiles

- Generate hypotheses about compound mechanism and gene function

Hit Validation and Prioritization

Following primary screening, a multi-tiered validation approach ensures resource allocation to the most promising hits:

Secondary Assays:

- Dose-response confirmation: 8-point dilution series in biological replicates

- Orthogonal assays: Different phenotypic readouts (morphology, cell cycle, apoptosis)

- Selectivity assessment: Counter-screening against unrelated strains/cell types

- 3D culture models: Enhanced physiological relevance using spheroid cultures [31]

Tertiary Validation:

- Mechanism of action studies: Target identification and pathway analysis

- Resistance generation: Spontaneous mutant isolation and characterization

- Structural optimization: Initial medicinal chemistry for hit-to-lead progression

The integration of computational methods, particularly machine learning approaches like DrugReflector, has dramatically improved the efficiency of this process, enabling more focused and productive screening campaigns [34].

Phenotypic screening using small molecules to reveal conditional mutant phenotypes represents a powerful methodology at the intersection of chemical biology and genetics. The approach has proven particularly valuable in model organisms like yeast and parasites, where it enables systematic exploration of gene function and identification of novel therapeutic targets.

Future developments in the field are likely to focus on several key areas:

- Integration of multi-omics data to connect phenotypic outcomes with molecular mechanisms

- Advanced machine learning methods for predicting chemical-genetic interactions

- Microphysiological systems that better recapitulate tissue and organismal complexity

- High-content morphological profiling with single-cell resolution

As these technological advances mature, phenotypic screening will continue to evolve as a critical tool for both basic research and therapeutic development, particularly for identifying first-in-class compounds with novel mechanisms of action [32] [35]. The ongoing integration of phenotypic and target-based approaches represents a powerful hybrid strategy that leverages the strengths of both paradigms for more effective drug discovery.

High-Throughput Screening and Computational Prediction Workflows

The model organism Saccharomyces cerevisiae has become an indispensable platform for systematic drug discovery and functional genomics, primarily due to its well-annotated genome, rapid generation time, and the extensive conservation of fundamental eukaryotic biology with human cells [9] [36]. Over the past two decades, yeast has catalyzed innovations across functional genomics, genome editing, and proteomics, providing a powerful model for understanding conserved eukaryotic cellular biochemistry [9]. A cornerstone of this utility is the development of high-throughput chemical genomic assays that enable the unbiased identification of drug targets and the elucidation of mechanisms of action (MoA) for novel compounds [36]. These assays are predicated on a simple yet powerful principle: observing the phenotypic response of a comprehensive collection of yeast deletion strains when exposed to a chemical perturbant [37].

The primary experimental paradigms in this field are Haploinsufficiency Profiling (HIP), Homozygous Profiling (HOP), and Haploid Profiling. These methods leverage the yeast deletion collections, wherein each strain carries a precise, start-to-stop deletion of a single gene, replaced with a unique molecular barcode that enables pooled growth assays [9] [36]. When a pool of these deletion strains is grown competitively in the presence of a sub-lethal dose of a compound, the relative depletion or enrichment of specific strains, quantified via their barcode abundance, reveals functional interactions between the deleted genes and the compound [37] [38]. This in vivo profiling offers a comprehensive snapshot of the cellular response to small molecules, capturing not only direct target inhibition but also downstream pathway effects and off-target activities [38]. The integration of these chemical-genetic interactions with large-scale genetic interaction networks has further accelerated drug-target identification, providing a systems-level view of compound mechanism [39] [40]. This whitepaper details the core principles, methodologies, and applications of HIP, HOP, and haploid profiling, framing them within the broader context of antimicrobial and anti-parasitic drug discovery.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

The three primary yeast chemical-genetic assays exploit distinct genetic principles to uncover different aspects of a compound's mechanism of action.

Haploinsufficiency Profiling (HIP) utilizes a pool of heterozygous diploid yeast deletion strains, where one copy of an essential or non-essential gene has been deleted [38] [36]. This assay is designed to identify a compound's direct protein targets. The underlying principle is drug-induced haploinsufficiency: if a compound inhibits the protein product of a specific gene, a strain with only one functional copy of that gene will be hypersensitive to the compound [38] [39]. The heterozygous deletion results in a 50% reduction in the target protein's abundance, and the additional chemical inhibition synergizes to create a disproportionate fitness defect, making the strain drop out of the competitive pool more rapidly than others [37] [38].