Chemical Biology Platforms: The Engine of Modern Drug Discovery and Translational Physiology

This article explores the integral role of chemical biology platforms in bridging the gap between basic research and clinical application in drug discovery.

Chemical Biology Platforms: The Engine of Modern Drug Discovery and Translational Physiology

Abstract

This article explores the integral role of chemical biology platforms in bridging the gap between basic research and clinical application in drug discovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive examination of the field—from its foundational principles and key historical shifts to the latest methodological tools like chemoproteomics and AI. The scope extends to practical strategies for troubleshooting optimization challenges, contemporary validation techniques for assessing clinical potential, and a comparative analysis of platform efficiencies. By synthesizing insights across the translational continuum, this article serves as a strategic guide for leveraging chemical biology to enhance the efficacy and speed of therapeutic development.

From Potent Compounds to Clinical Benefit: The Evolution of a Discipline

The chemical biology platform represents an organizational and strategic framework within pharmaceutical research and development that is fundamentally rooted in a multidisciplinary, mechanism-based approach. Its evolution marks a significant departure from traditional, empirical drug discovery methods, driven by the critical need to demonstrate clear clinical benefit for highly potent, target-specific compounds [1]. This platform is defined by its systematic integration of knowledge across chemistry, biology, and physiology to optimize drug target identification and validation, thereby improving the safety and efficacy profiles of biopharmaceuticals [1].

The core philosophy of the chemical biology platform is its emphasis on understanding underlying biological processes and leveraging knowledge gained from the action of similar molecules on these processes [1]. It connects a series of strategic steps to determine whether a newly developed compound could translate into clinical benefit through the lens of translational physiology, which examines biological functions across multiple levels—from molecular interactions to population-wide effects [1]. This approach has become a critical component in modern drug development, fostering a mechanism-based pathway to clinical advancement that persists in both academic and industry-focused research environments [1].

Core Principles and Strategic Framework

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

At its essence, chemical biology involves the study and modulation of biological systems and the creation of biological response profiles through the use of small molecules that are selected or designed based on current knowledge of the structure, function, or physiology of biological targets [1]. Unlike traditional approaches that relied primarily on trial-and-error methods, even when using high-throughput technologies, chemical biology focuses on selecting target families and incorporates systems biology approaches to understand how protein networks integrate [1].

The chemical biology platform achieves its objectives through several defining characteristics:

- Multidisciplinary Teamwork: It relies on collaborative teams that accumulate knowledge and solve problems, often using parallel processes to accelerate timelines and reduce costs associated with bringing new drugs to patients [1].

- Targeted Selection: It emphasizes rational target selection over random screening approaches [1].

- Integration of Omics Technologies: It leverages systems biology techniques, including transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and network analyses, to comprehensively understand protein network interactions [1].

- Physiological Context: Physiology forms the core of the platform by providing essential biological context in which chemical tools and principles are applied to understand and influence living systems [1].

The Four-Step Translational Framework

A critical historical development in the chemical biology platform was the establishment of a systematic four-step framework, based on Koch's postulates, to indicate potential clinical benefits of new therapeutic agents [1]:

- Identify a disease parameter (biomarker)

- Show that the drug modifies that parameter in an animal model

- Show that the drug modifies the parameter in a human disease model

- Demonstrate a dose-dependent clinical benefit that correlates with similar change in direction of the biomarker

This framework was first operationalized through the creation of Clinical Biology departments in pharmaceutical companies, which were tasked with bridging the gap between preclinical findings and clinical outcomes [1]. This approach represented the first organized effort in the industry to focus on translational physiology, examining biological functions across levels spanning from molecules to cells to organs to populations [1].

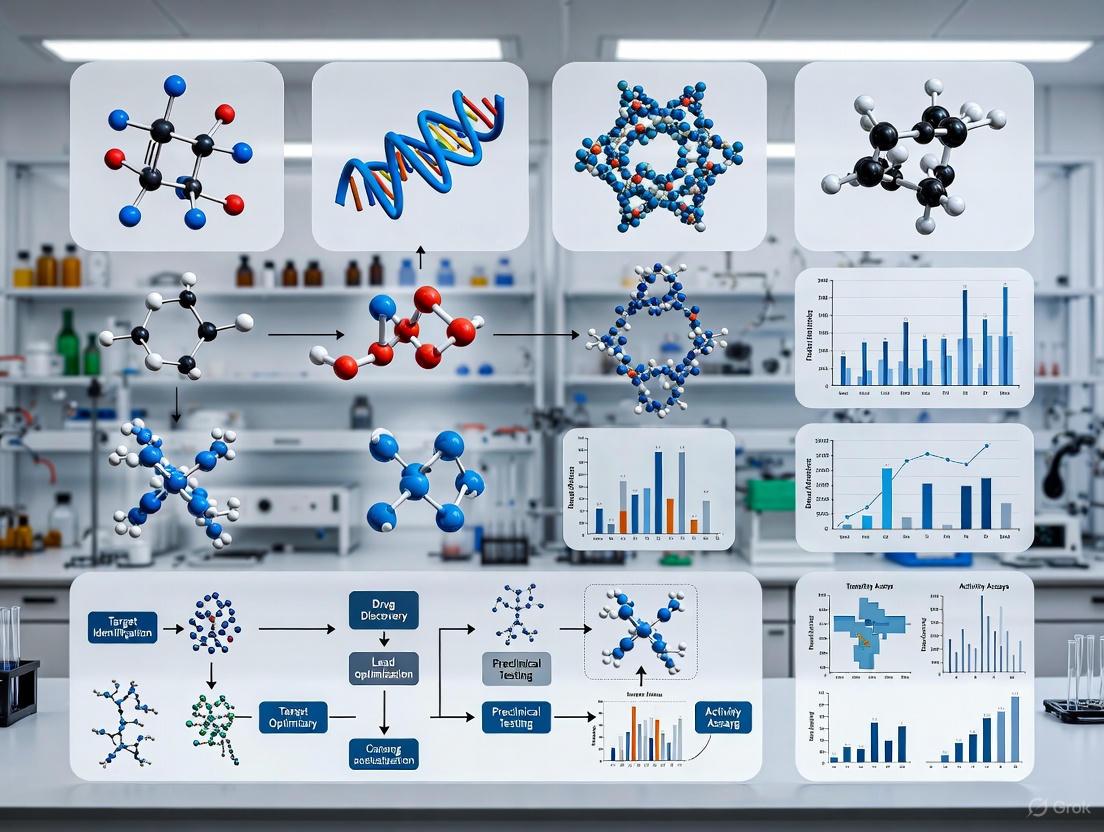

Figure 1: The Four-Step Translational Framework for validating clinical benefit of new therapeutic agents, adapted from the approach developed in Clinical Biology departments [1].

Key Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Integrative Workflow for Target Validation

The chemical biology platform employs a sophisticated, integrated workflow that connects various technological and methodological approaches to validate therapeutic targets. This workflow synthesizes knowledge from diverse disciplines and technologies to establish a robust, mechanism-based understanding of drug-target interactions and their physiological consequences.

Figure 2: Integrated workflow of the chemical biology platform, synthesizing multiple technological approaches for target validation and lead optimization [1].

Advanced Cellular Assay Technologies

The platform incorporates sophisticated cellular assay technologies that enable multiparametric analysis of cellular events. These include:

- High-content multiparametric analysis using automated microscopy and image analysis to quantify cell viability, apoptosis, cell cycle analysis, protein translocation, and phenotypic profiling [1].

- Reporter gene assays to assess signal activation in response to ligand-receptor engagement [1].

- Ion channel activity assessment using voltage-sensitive dyes or patch-clamp techniques to screen neurological and cardiovascular drug targets [1].

These advanced cellular assays, often coupled with genetic manipulation capabilities, provide the functional data necessary to validate targets and optimize lead compounds within a physiological context [1].

Objective Assessment of Chemical Probes

A critical methodological advancement within the chemical biology platform is the development of objective, quantitative, data-driven assessment of chemical probes. Tools such as Probe Miner capitalize on public medicinal chemistry data to empower systematic evaluation of chemical probes across multiple parameters [2]. This approach involves:

- Systematic analysis of chemical probes to uncover new insights and limitations

- Novel data-driven scoring methodologies that enable objective assessment

- Public, regularly updated resources that equip researchers to evaluate probes

- Integration with expert curation to provide a powerful resource for probe selection

This quantitative framework addresses the critical need for high-quality chemical tools in biomedical research, particularly for target validation and understanding biological systems [2].

Quantitative Data in Chemical Biology Research

Key Performance Metrics and Standards

Quantitative assessment is fundamental to the chemical biology platform, with rigorous standards applied to evaluate compound suitability, assay performance, and experimental accuracy. The platform employs various statistical measures to ensure data quality and reproducibility.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Experimental Assessment in Chemical Biology

| Metric | Calculation Formula | Application in Chemical Biology | Acceptance Criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Error | `% error = | (measured value - expected value) / expected value | × 100` | Assessment of equipment accuracy (balances, pipettes) and experimental precision [3]. | Varies by application; lower values indicate greater accuracy. |

| Average Measured Mass | Average = (Mass1 + Mass2 + Mass3) / 3 |

Determination of mean values from replicate measurements to establish reliable baseline data [3]. | Replicates should show low variability. | ||

| Z-factor | `Z-factor = 1 - (3×(σsample + σcontrol) / | μsample - μcontrol | )` | Quality metric for high-throughput screening assays; measures assay signal dynamic range and data variation [1]. | Z' > 0.5 indicates excellent assay; Z' > 0.4 acceptable. |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | CV = (Standard Deviation / Mean) × 100% |

Measurement of precision and reproducibility in biochemical and cellular assays [1]. | Typically <20% for biological assays; <10% for analytical methods. |

Historical Distribution of Drug Targets

The implementation of the chemical biology platform in the pharmaceutical industry circa 2000 focused on approximately 500 targets across specific protein families, with the following distribution [1]:

Table 2: Historical Distribution of Drug Targets in Pharmaceutical Research (c. 2000)

| Target Class | Percentage of Industry Focus | Representative Therapeutic Areas |

|---|---|---|

| G-protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) | 45% | Cardiovascular, neurological, metabolic diseases |

| Enzymes | 25% | Oncology, inflammatory diseases, infectious diseases |

| Ion Channels | 15% | Neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases |

| Nuclear Receptors | ~2% | Metabolic diseases, endocrine disorders |

| Other Targets | ~13% | Various therapeutic areas |

This targeted distribution reflects the mechanism-based approach of chemical biology, focusing on target families with well-characterized physiological functions and therapeutic potential [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental implementation of the chemical biology platform relies on a carefully selected set of research reagents and tools that enable the precise manipulation and analysis of biological systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Biology Investigations

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Chemical Biology Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | Selective kinase inhibitors, GPCR modulators, epigenetic probes | Tool compounds for perturbing and understanding specific biological targets and pathways; essential for target validation [2]. |

| Cellular Assay Systems | Reporter gene assays, voltage-sensitive dyes, high-content screening assays | Functional assessment of compound effects in cellular contexts; provides physiological relevance to molecular interactions [1]. |

| Biomarker Detection Reagents | Selective antibodies, molecular probes, binding agents | Identification and quantification of disease parameters and target engagement in both animal models and human disease models [1]. |

| Characterized Biological Models | Genetically engineered cell lines, animal models of disease, human disease models | Systems for evaluating compound effects across translational continuum from in vitro to in vivo contexts [1]. |

| Analytical Standards | Internal standards, reference compounds, quality control materials | Ensuring accuracy, precision, and reproducibility of quantitative measurements across experimental systems [3]. |

Implementation in Drug Discovery and Development

Integrated Discovery Workflow

The chemical biology platform operates through an integrated workflow that spans from initial target identification to clinical proof-of-concept, with decision points that determine progression of compounds through the development pipeline.

Figure 3: Implementation workflow of the chemical biology platform in pharmaceutical R&D, showing the critical role of Clinical Biology in bridging preclinical and clinical development [1].

Impact on Translational Physiology

The chemical biology platform has profoundly influenced translational physiology by providing a systematic framework for examining biological functions across multiple levels of organization. This integration has enabled researchers to:

- Bridge molecular and systems biology by connecting precise molecular interventions with organism-level physiological responses [1].

- Identify and validate targets within their physiological context, ensuring therapeutic relevance [1].

- Develop tools for directed application that are biologically meaningful, relevant, and translatable to real-world health and disease contexts [1].

- Discover drugs for therapeutic use through mechanism-based approaches that prioritize understanding of physiological systems [1].

The platform's emphasis on physiology as its core ensures that chemical tools and insights maintain biological relevance throughout the drug discovery and development process [1].

The chemical biology platform continues to evolve, incorporating new technologies and methodologies that enhance its mechanism-based, multidisciplinary approach. The integration of objective, quantitative assessment tools for chemical probes represents a significant advancement in ensuring the quality and reliability of research tools used in the platform [2]. Furthermore, the growing emphasis on precision medicine aligns perfectly with the platform's foundational principles of targeted, mechanism-based therapeutic development [1].

The continued influence of the chemical biology platform in both academic research and pharmaceutical innovation underscores its value as a framework for advancing clinical medicine through rigorous, physiology-informed science. As the platform incorporates emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and advanced data analytics, its capacity to bridge the gap between basic chemical biology and clinical application will only strengthen, further solidifying its role as a critical component in modern drug development and translational research.

For researchers implementing this platform, understanding its historical development, integrative nature, and foundation in translational physiology is essential for designing experimental studies that effectively connect molecular interventions with physiological outcomes and, ultimately, clinical benefit [1].

The pharmaceutical research landscape of the late 20th century faced a fundamental crisis: the inability to translate potent, mechanism-specific compounds into demonstrated clinical benefit. This efficacy challenge catalyzed a paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches to integrated research models centered on chemical biology and translational physiology. This whitepaper examines the historical evolution of this pivot, detailing how the strategic integration of multidisciplinary teams, biomarker validation, and systems biology technologies addressed critical translational gaps. For today's researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this historical transition provides foundational insights for designing modern experimental studies that effectively bridge laboratory discovery and clinical application.

The final decades of the 20th century marked a pivotal period in pharmaceutical research. While advances in chemistry and molecular biology enabled the production of highly potent compounds targeting specific biological mechanisms, the industry confronted a formidable obstacle: demonstrating meaningful clinical benefit in patients [1]. This efficacy challenge emerged as the primary bottleneck in the drug development pipeline, where promising laboratory results consistently failed to translate into successful human therapeutics.

The traditional drug development approach relied heavily on trial-and-error methodologies, including high-throughput screening campaigns that often prioritized quantity over biological relevance [1]. This model generated numerous potent compounds but provided insufficient understanding of their interaction with complex physiological systems. The fundamental gap between mechanistic potency and clinical efficacy exposed systemic limitations in the prevailing research paradigm, necessitating a fundamental restructuring of pharmaceutical R&D strategy.

Regulatory changes further intensified this crisis. The 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendment, enacted in response to the thalidomide tragedy, mandated proof of efficacy from "adequate and well-controlled clinical trials" [1]. This requirement bifurcated Phase II clinical evaluation into distinct components: Phase IIa for identifying potential disease targets and Phase IIb/III for demonstrating statistical proof of efficacy and safety. This regulatory landscape demanded more sophisticated approaches to establishing drug efficacy earlier in the development process.

The Rise of Translational Physiology and Clinical Biology

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

The response to the efficacy challenge emerged through the formalization of translational physiology, defined as "the examination of biological functions across levels spanning from molecules to cells to organs to populations" [1]. This discipline provided the conceptual framework for integrating knowledge across biological scales, fundamentally shifting how researchers approached the efficacy gap.

A critical institutional development in this transition was the establishment of the Translational Physiology Interest Group within the American Physiological Society in 2010, signaling formal recognition of this emerging discipline [1]. This organizational endorsement reflected a growing consensus that understanding physiological integration across multiple levels was essential for predicting clinical efficacy.

The Clinical Biology Department: An Organizational Innovation

The strategic organizational response to the efficacy challenge materialized in 1984 with the creation of the Clinical Biology department at Ciba (now Novartis) [1]. This innovative structure was specifically designed to bridge the critical gap between preclinical findings and clinical outcomes by fostering direct collaboration between preclinical physiologists, pharmacologists, and clinical pharmacologists.

The Clinical Biology team was tasked with identifying human disease models and biomarkers that could demonstrate drug effects before progressing to costly Phase IIb and III trials [1]. This approach encompassed Phases I and IIa of clinical development, focusing on establishing proof-of-concept in select disease subsets through:

- Identification of appropriate biomarkers of target engagement

- Development of human disease models with clinically monitorable symptoms

- Demonstration of relationship between biomarker modulation and clinical symptoms

The Four-Step Framework for Clinical Benefit Assessment

The Clinical Biology department implemented a systematic four-step framework, adapted from Koch's postulates, to evaluate potential clinical benefit of new therapeutic agents [1]:

- Identification of a specific disease parameter (biomarker)

- Demonstration that the drug modifies this parameter in animal models

- Verification that the drug modifies the parameter in human disease models

- Correlation of dose-dependent clinical benefit with biomarker changes

This framework's utility was demonstrated through its application to CGS 13080, a thromboxane synthase inhibitor. The approach revealed critical limitations in the compound's pharmacokinetic profile—specifically a short 73-minute half-life and lack of feasible oral formulation—leading to early termination of development before substantial resources were expended on later-phase trials [1]. This case exemplified how the Clinical Biology model could efficiently identify fundamental efficacy barriers.

Table 1: Evolution of Key Organizational Structures in Pharmaceutical R&D

| Time Period | Dominant Model | Primary Focus | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1980s | Separate Chemistry & Pharmacology | Compound screening; Animal models | Limited clinical translation; Trial-and-error approach |

| 1984 onward | Clinical Biology Department | Biomarker identification; Human disease models | Early-phase focus; Limited impact on late-stage development |

| 2000 onward | Chemical Biology Platform | Target validation; Systems biology | Integration complexity; Data interpretation challenges |

The Chemical Biology Platform: An Integrative Framework

Conceptual Foundation and Definition

The formalization of the chemical biology platform around the year 2000 represented the maturation of translational approaches into a comprehensive organizational framework [1]. Chemical biology is defined as "the study and modulation of biological systems, and the creation of biological response profiles through the use of small molecules" selected or designed based on knowledge of biological target structure, function, or physiology [1].

This platform emerged synergistically with several technological advancements, including:

- Completion of the Human Genome Project and expansion of genomic information

- Advances in combinatorial chemistry for compound library generation

- Improvements in structural biology methods, particularly for membrane-bound receptors

- Sophisticated cellular assays with genetic manipulation capabilities

Strategic Implementation and Target Focus

The chemical biology platform fundamentally shifted screening strategies from indiscriminate testing to targeted selection based on biological understanding. By 2000, the pharmaceutical industry was focusing on approximately 500 targets across key protein families [1]:

- G-protein coupled receptors (45%)

- Enzymes (25%)

- Ion channels (15%)

- Nuclear receptors (~2%)

This target distribution reflected a prioritization of target classes with established druggability and physiological significance, enabling more efficient resource allocation.

Enabling Technologies and Methodologies

The chemical biology platform incorporated advanced experimental systems that provided multidimensional data on compound activity [1]:

- High-content multiparametric analysis using automated microscopy and image analysis to quantify cell viability, apoptosis, cell cycle analysis, protein translocation, and phenotypic profiling

- Reporter gene assays for assessing signal activation in response to ligand-receptor engagement

- Ion channel activity assessment using voltage-sensitive dyes or patch-clamp techniques for neurological and cardiovascular targets

These technologies enabled the generation of biological response profiles that contextualized compound activity within broader physiological systems rather than isolated molecular targets.

Modern Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Biomarker Validation Framework

The historical emphasis on biomarker development established through the Clinical Biology model has evolved into sophisticated validation protocols. The contemporary biomarker validation workflow integrates computational and experimental approaches:

Diagram 1: Biomarker validation workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Modern chemical biology research relies on integrated technology platforms and reagent systems that enable comprehensive compound profiling:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Biology

| Reagent/Platform Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-omics Analysis Platforms | Proteomics, Metabolomics, Transcriptomics | Understanding protein network interactions and systems biology [1] |

| Advanced Cellular Assay Systems | High-content multiparametric analysis, Reporter gene assays, Patch-clamp techniques | Quantifying cell viability, apoptosis, protein translocation, signal activation [1] |

| Specialized Compound Libraries | DNA-encoded libraries, Diversity-oriented synthesis | Expanding chemical space exploration for bioactive compounds [4] [5] |

| Bioorthogonal Chemistry Reagents | Tetrazine ligations, Strained alkynes, Light-activated systems | Selective molecular tagging in biological systems for imaging and drug delivery [4] |

| Computational Chemistry Databases | QDπ dataset, Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) | Training universal MLP models for molecular simulations in drug discovery [6] |

AI-Enhanced Methodologies for Predictive Compound Profiling

Contemporary chemical biology increasingly incorporates artificial intelligence and machine learning to accelerate compound optimization:

Diagram 2: AI-enhanced compound profiling

The QDπ dataset exemplifies modern data resources, incorporating 1.6 million molecular structures with energies and forces calculated at the ωB97M-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVPPD theory level to enable accurate machine learning potential development [6]. This dataset employs active learning strategies to maximize chemical diversity while minimizing computational expense through query-by-committee approaches that identify structures introducing significant new information [6].

Quantitative Impact Assessment

Historical Efficiency Metrics

The transition to chemical biology platforms has generated measurable impacts on pharmaceutical R&D efficiency. Analysis of development timelines reveals significant acceleration in specific therapeutic areas:

Table 3: Drug Development Timeline Acceleration Across Therapeutic Areas

| Therapeutic Area | Traditional Timeline (Years) | Accelerated Timeline (Years) | Key Accelerating Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oncology | 7-10 | 2-3 | AI-powered modeling, Adaptive trial designs, Platform-based clinical operations [7] |

| Infectious Disease | 7-10 | <1 (COVID-19 vaccines) | Real-time data sharing, Rolling regulatory reviews [7] |

| Rare Diseases | 7-10 | 3-5 | High-throughput omics strategies, Patient-derived organoids [8] [7] |

The economic implications of these accelerated timelines are substantial, with median R&D costs for novel drugs approximating $150 million, though complex therapeutics can exceed $1.3 billion [7]. The orphan drug market, a key focus of targeted therapeutic development, is projected to surpass $394.7 billion by 2030, reflecting the economic viability of the precision medicine model [7].

Success Metrics in Contemporary Drug Discovery

Analysis of screening efficiency demonstrates the impact of integrated chemical biology approaches. Research comparing virtual screening libraries of 99 million versus 1.7 billion molecules revealed that the larger library produced improved hit rates, enhanced compound potency, and an increased number of scaffolds [5]. This scaling effect underscores the value of comprehensive chemical space exploration enabled by modern computational infrastructure.

The integration of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) further enhances predictive capability. These include:

- Organ-on-a-chip systems that provide human-specific biology inaccessible through animal models

- AI and machine learning models that predict safety, immunogenicity, and pharmacokinetics

- 3D organoid models for oncology preclinical screening [8]

These platforms address fundamental limitations of traditional animal models, particularly concerning the genetic homogeneity of laboratory animals versus human population diversity [8].

Future Directions and Emerging Opportunities

Technology Convergence Trends

The continued evolution of chemical biology platforms reflects increasing integration of complementary technologies:

- Bioorthogonal chemistry advances enabling selective reactions in living systems for in vivo imaging and drug delivery [4]

- Chemoenzymatic strategies combining enzymatic and chemical steps for complex molecule synthesis [4]

- Foundation models trained on massive biological datasets to uncover fundamental biological principles [9]

- AI agents that automate bioinformatics tasks and lower barriers to advanced data analysis [9]

Addressing Persistent Challenges

Despite significant advances, chemical biology continues to confront methodological challenges:

- Limited enzyme catalysis scope for novel non-natural transformations [4]

- Bioorthogonal translation hurdles from model systems to human clinical applications [4]

- NAM validation requirements for regulatory acceptance [8]

- Systemic complexity in replicating multi-organ interactions [8]

The historical pivot from efficacy challenge to integrated R&D model established a foundation for addressing these challenges through multidisciplinary collaboration and technological innovation. As the field progresses, the continued refinement of this framework promises to further enhance the efficiency and success of therapeutic development.

The historical pivot from traditional drug development to integrated chemical biology platforms represents a foundational transformation in pharmaceutical R&D. Triggered by the critical challenge of demonstrating clinical efficacy for mechanism-based compounds, this shift established translational physiology as the conceptual core bridging basic research and clinical application. The organizational innovation of Clinical Biology departments in the 1980s provided the initial structural framework, which evolved into comprehensive chemical biology platforms incorporating systems biology, biomarker validation, and multidisciplinary team science.

For contemporary researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this historical transition provides critical insights for designing experimental studies that effectively navigate the complex pathway from molecular discovery to clinical implementation. The continued integration of emerging technologies—including AI-driven discovery, organ-on-a-chip systems, and bioorthogonal chemistry—within this established conceptual framework promises to further enhance the efficiency and success of therapeutic development in the precision medicine era.

The convergence of translational physiology and systems biology represents a paradigm shift in modern drug discovery and development. This integration, often orchestrated within a chemical biology platform, provides a powerful, holistic framework for understanding disease mechanisms and predicting clinical outcomes. By bridging the gap between molecular insights and whole-organism physiology, this synergy enables a more mechanistic approach to therapeutic development. This whitepaper explores the core conceptual, methodological, and computational pillars of this integration, providing technical guidance and protocols for its implementation. The discussion is framed within the context of advancing precision medicine, highlighting how these disciplines collectively enhance target validation, candidate selection, and the overall efficacy and safety of biopharmaceuticals.

The contemporary pharmaceutical research landscape has evolved from traditional, empirical methods to a more predictive, mechanism-based approach. Central to this evolution is the chemical biology platform, an organizational strategy that optimizes drug target identification and validation by emphasizing a deep understanding of underlying biological processes [1]. This platform achieves its goals through the strategic integration of two powerful disciplines:

- Translational Physiology: Defined as the examination of biological functions across multiple levels of organization, from molecules and cells to organs and populations [1]. It provides the essential biological context for understanding function in a living system.

- Systems Biology: A holistic, interdisciplinary approach that combines experimental and computational strategies to integrate information from different biological scales to unravel pathophysiological mechanisms [10]. It leverages high-throughput technologies to generate massive multi-omics datasets (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics).

Individually, each field offers valuable insights; however, their integration creates a synergistic effect that is transformative. Translational physiology ensures that molecular discoveries are grounded in biological reality and clinical relevance, while systems biology provides the comprehensive, data-rich maps of biological networks and interactions. Together, they form the core of a robust framework for identifying and validating therapeutic targets, understanding drug actions and toxicities, and ultimately, delivering more effective and precise medicines to patients [1] [11].

Pillar 1: Foundational Concepts and Workflow Integration

The first pillar involves the strategic merging of the fundamental principles and workflows of translational physiology and systems biology into a cohesive, iterative process for drug discovery.

The Role of the Chemical Biology Platform

The chemical biology platform acts as the organizing principle that connects a series of strategic steps to determine whether a newly developed compound will translate into clinical benefit [1]. Unlike traditional trial-and-error methods, it leverages systems biology techniques—such as proteomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics—to prioritize targeted selection [1] [12]. This platform is inherently multidisciplinary, relying on parallel processes to accelerate timelines and reduce the costs of bringing new drugs to patients [1].

A historical precedent for this integration was the establishment of Clinical Biology departments in the 1980s, which were early organized efforts to bridge preclinical and clinical research [1]. This approach was formalized using a four-step process, analogous to Koch's postulates, to gauge clinical benefit:

- Identify a disease parameter (biomarker).

- Show that the drug modifies that parameter in an animal model.

- Show that the drug modifies the parameter in a human disease model.

- Demonstrate a dose-dependent clinical benefit that correlates with a similar change in the direction of the biomarker [1].

This logical, step-wise approach, which seamlessly connects molecular data (biomarkers) with physiological and clinical outcomes, is the direct precursor to modern integrated workflows.

The Integrated Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the modern, iterative workflow for drug discovery that integrates systems biology and translational physiology, guided by the chemical biology platform.

Pillar 2: Methodological and Technical Approaches

The second pillar encompasses the specific experimental and analytical methodologies that enable the practical integration of systems biology and translational physiology.

Multi-omics Integration Strategies

Systems biology provides a suite of high-throughput technologies for generating multi-omics data. The integration of these datasets is crucial for gaining a holistic view of biological systems and disease pathologies [10]. The predominant data-driven integration strategies can be categorized as follows:

Table 1: Data-Driven Multi-Omics Integration Approaches

| Category | Description | Common Tools & Methods | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical & Correlation-Based | Quantifies the degree and significance of relationships between variables across omics datasets. | Pearson’s/Spearman’s correlation, RV coefficient, Procrustes analysis [10]. | Identifying coordinated changes (e.g., transcript-to-protein correlations), assessing dataset similarity. |

| Multivariate Methods | Reduces data dimensionality and identifies latent structures that explain variance across multiple omics datasets. | Partial Least Squares (PLS), Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [10]. | Identifying combined molecular patterns that differentiate patient groups or phenotypes. |

| Network Analysis | Transforms pairwise associations into graphical models to identify highly interconnected functional modules. | Weighted Gene Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA), xMWAS [10]. | Discovering clusters of co-expressed genes/proteins/metabolites and linking modules to clinical traits. |

| Machine Learning (ML) & Artificial Intelligence (AI) | Uses algorithms to learn complex, non-linear patterns from integrated omics data for prediction and classification. | Classification models, regression models, feature selection algorithms [10]. | Identifying complex biomarker signatures, predicting patient response, classifying disease subtypes. |

A 2025 review of 64 research papers indicated that statistical and correlation-based approaches were the most prevalent, followed by multivariate methods and ML/AI techniques [10]. The choice of method depends on the specific biological question, data quality, and the desired outcome (e.g., biomarker discovery vs. pathway elucidation).

Experimental Protocols for Integrated Workflows

The following is a generalized protocol for a typical integrated study, such as investigating a disease mechanism or drug response.

Protocol: An Integrated Multi-Omics and Physiological Workflow

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Collect relevant biological samples (e.g., tissue, blood, primary cells) from well-characterized in vivo models (e.g., spontaneously hypertensive rat [1]) or human cohorts. Patient samples should be stratified and well-annotated [13].

- Divide samples for subsequent multi-omics analyses and functional/physiological assays.

Multi-Omics Profiling:

- Perform genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiling on the same sample set using appropriate high-throughput platforms (e.g., NGS for genomics/transcriptomics, LC-MS for proteomics/metabolomics).

- Key Consideration: Ensure data quality control, including handling missing values, normalization, and batch effect correction [10].

Functional Phenotypic Assessment:

- In parallel, conduct physiological or phenotypic assays relevant to the disease or drug target. This leverages translational physiology tools.

- Examples include high-content multiparametric analysis of cellular events (cell viability, apoptosis, protein translocation [1]), reporter gene assays, ion channel activity measurements using patch-clamp techniques [1], and using automated platforms for standardized 3D cell culture to improve reproducibility [14].

Data Integration and Analysis:

- Apply one or more integration strategies from Table 1 (e.g., WGCNA, xMWAS, ML) to the multi-omics data.

- The goal is to identify molecular networks, key drivers, and biomarker candidates associated with the physiological or phenotypic changes observed in Step 3.

Model Validation and Iteration:

- Validate key findings using orthogonal methods (e.g., qPCR, immunoblotting) in an independent sample set.

- Use genetic (e.g., CRISPR) or pharmacological interventions in relevant in vitro or in vivo models to perturb identified targets and confirm their functional role in the phenotype. This closes the loop between systems-level observation and physiological causation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Integrated Studies

| Item | Function in Integrated Workflows |

|---|---|

| Well-Annotated Patient Biospecimens | Provides clinically relevant biological material for omics profiling and model development. Essential for ensuring translational relevance [13]. |

| Human-Relevant Cell Models (e.g., 3D Organoids) | Offers a more physiologically accurate in vitro system for high-content screening and toxicity assessment, reducing reliance on animal models [14]. |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) | Large collections of small molecules used for high-throughput screening against protein targets to identify potential drug leads [15]. |

| Antibodies for Immunoblotting | Enables relative quantitation of protein abundance for target validation and confirmation of omics findings [1]. |

| Reporter Gene Assay Kits | Used to assess signal activation in response to ligand-receptor engagement, linking molecular events to cellular responses [1]. |

| Voltage-Sensitive Dyes / Patch-Clamp Equipment | Critical for functional screening of neurological and cardiovascular drug targets, connecting molecular target engagement to cellular physiology [1]. |

| Automated Liquid Handlers (e.g., Tecan Veya) | Ensures consistency, reproducibility, and throughput in sample preparation and assay execution, reducing human variation [14]. |

Pillar 3: Computational Modeling and Data Analysis

The third pillar involves the computational infrastructure and modeling approaches required to synthesize data from systems biology and translational physiology into actionable, predictive insights.

The Role of AI, Machine Learning, and Data Management

The volume and complexity of data generated by integrated workflows necessitate robust computational strategies.

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI/ML is increasingly used to uncover complex, non-linear patterns from integrated omics and physiological data. Applications include de novo design of novel chemical compounds [15], identification of biomarker signatures from imaging and multi-omics data [14], and prediction of patient responses. A critical success factor is grounding AI in biological reality through close collaboration with experimentalists to prevent model "hallucination" [15].

- Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP): QSP is a modeling discipline that leverages systems biology to simulate drug behaviors, predict patient responses, and optimize drug development strategies [11]. QSP models integrate knowledge of biological pathways, drug properties, and disease mechanisms to create virtual patient populations, enabling more informed decisions in clinical trial design.

- Data Traceability and Management: The effectiveness of AI and QSP is contingent on data quality and metadata completeness. There is a growing industry focus on capturing every condition and state of an experiment to provide quality data for models to learn from [14]. This requires software platforms that connect data, instruments, and processes to break down data silos [14].

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

The following diagram maps the logical flow of data and knowledge from initial multi-omics data generation to final clinical application, highlighting the computational integration points.

Current Applications and Future Outlook

The integration of translational physiology and systems biology is already driving innovation across the drug development spectrum.

- Precision Medicine: The integrated approach is fundamental to precision medicine. By understanding disease subtypes through multi-omics and linking them to clinical outcomes via translational physiology, therapies can be targeted to specific patient populations [1] [11].

- Biomarker Discovery: The combined power of multi-omics integration and physiological validation accelerates the identification of robust diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers [10]. For example, foundation models applied to histopathology and multiplex imaging data are being used to identify new biomarkers and link them to clinical outcomes [14].

- Educational Evolution: To sustain this progress, cultivating a skilled workforce is essential. Successful industry-academia partnerships are crucial for developing MSc and PhD programs that equip the next generation of scientists with the necessary blend of biological, computational, and mathematical skills [11]. Examples include specialized programs at the University of Manchester, Imperial College, and the University of Delaware [11].

The future of this integrated field will be characterized by a tighter feedback loop between computational prediction and experimental validation, increased use of human-relevant models like automated 3D organoids [14], and the continued maturation of AI as a grounded, practical tool for accelerating the journey from bench to bedside.

The evolution of drug discovery from a discipline rooted in clinical biology to one powered by the genomic revolution represents a fundamental paradigm shift in biomedical science. This transition has been orchestrated within the context of the chemical biology platform, an organizational approach designed to optimize drug target identification and validation while improving the safety and efficacy of biopharmaceuticals [1]. This platform achieves its goals through a multidisciplinary emphasis on understanding underlying biological processes and leveraging knowledge gained from the action of similar molecules on these systems [1]. The integration of translational physiology—which examines biological functions across multiple levels from molecules to populations—has been deeply influenced by this evolution, creating a robust framework for modern therapeutic development [1]. This whitepaper traces the critical milestones in this journey, providing technical guidance for researchers navigating the contemporary drug discovery landscape.

The Foundation: Clinical Biology and Early Translational Models

The Emergence of Clinical Biology

The period from the 1950s to the 1980s witnessed the emergence of clinical biology as a response to regulatory changes and the limitations of traditional drug development approaches. The Kefauver-Harris Amendment of 1962 mandated proof of efficacy from well-controlled clinical trials, fundamentally changing pharmaceutical development strategies [1]. This regulatory shift necessitated more sophisticated approaches to bridge preclinical findings and clinical outcomes, leading to the establishment of Clinical Biology departments within pharmaceutical companies by the mid-1980s [1].

The clinical biology approach introduced a systematic framework for evaluating potential therapeutic agents, embodied in a four-step process adapted from Koch's postulates:

- Identification of a disease parameter (biomarker)

- Demonstration that the drug modifies that parameter in an animal model

- Verification that the drug modifies the parameter in a human disease model

- Confirmation of a dose-dependent clinical benefit that correlates with similar changes in the biomarker direction [1]

This methodology represented an early form of translational physiology, focusing on identifying human disease models and biomarkers that could more easily demonstrate drug effects before progressing to costly Phase IIb and III trials [1].

Pioneering Animal Models in Drug Development

The development of standardized animal models provided critical tools for evaluating therapeutic efficacy and safety. Key milestones in model development include:

Table: Historic Breakthroughs in Research Animal Models

| Year | Model | Significance | Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1906 | Wistar Rat [16] | First pure strain animal model for medical research | Standardized therapeutic testing |

| 1962 | Nude Mouse [16] | Major model for cancer progression and therapeutic intervention | Oncology drug development |

| 1974 | First transgenic mouse (SV40 DNA) [16] | First successful transfer of foreign DNA into a drug discovery animal model | Proof of concept for genetic manipulation |

| 1989 | First knockout mouse [16] | Technology for suppressing normal gene function to study gene function and disease | Functional genomics and target validation |

These models enabled researchers to replicate human diseases in systems that possessed biomarkers of interest, exhibited clinically monitorable symptoms, and demonstrated relationships between biomarker concentration and clinical conditions [1]. The spontaneously hypertensive rat for evaluating blood pressure control compounds and the rat tail-flick test for assessing pain reduction compounds represent classic examples of physiological screening systems that synergized with emerging mechanism-based approaches [1].

The Molecular Biology Revolution: Tools for Targeted Discovery

Key Technological Developments

The 1970s-1990s witnessed transformative advances in molecular biology that enabled precise targeting of DNA, RNA, and proteins involved in disease processes. Critical methodologies emerged during this period that became fundamental to modern drug discovery:

- Immunoblotting (late 1970s-early 1980s): Enabled relative quantitation of protein abundance, facilitating target validation [1]

- Monoclonal Antibody Technology (1975): Developed by Köhler and Milstein, enabling production of identical antibodies recognizing a single antigen, revolutionizing diagnostics and targeted therapies [17]

- Recombinant DNA Technology (1973): Pioneered by Cohen and Boyer, allowing DNA from different species to be combined and replicated in bacteria, launching the biotechnology industry [17]

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (1983): Developed by Kary Mullis, enabling exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences, transforming molecular analysis [16]

- DNA Sequencing (1977): Sanger's chain termination method enabled deciphering of genetic sequences, beginning with the bacteriophage Phi X 174 genome [17]

The Rise of High-Throughput Screening

By the 1990s, pharmaceutical research had shifted from traditional trial-and-error approaches to targeted selection strategies. The industry began focusing on specific target classes, with G-protein coupled receptors (45%), enzymes (25%), ion channels (15%), and nuclear receptors (~2%) comprising the majority of drug targets in the year 2000 [1]. This target-focused approach synergized with gains in high-throughput screening and combinatorial chemistry, enabled by several critical cellular assays:

- High-content multiparametric analysis using automated microscopy and image analysis to quantify cell viability, apoptosis, cell cycle analysis, protein translocation, and phenotypic profiling [1]

- Reporter gene assays to assess signal activation in response to ligand-receptor engagement [1]

- Ion channel activity screening using voltage-sensitive dyes or patch-clamp techniques for neurological and cardiovascular drug targets [1]

The Genomic Revolution: Decoding the Blueprint of Life

Foundational Milestones in Genomics

The genomic revolution represents one of the most significant transformations in biomedical science, originating from foundational discoveries and culminating in comprehensive mapping of human genetics.

Table: Key Milestones Powering the Genome Sequencing Revolution

| Era | Breakthrough | Key Scientists/Projects | Impact on Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Discovery of DNA double helix structure [18] | Watson, Crick, Franklin, Wilkins | Revealed molecular basis of heredity |

| 1977 | First genome sequenced (bacteriophage ΦX174) [18] | Frederick Sanger | Established methodology for genome sequencing |

| 1980s-1990s | Next-generation sequencing [18] | Various institutions | Enabled faster, cheaper genome data production |

| 2003 | Human Genome Project completion [19] | International consortium | Mapped entire human genetic code for target identification |

Technological Advances in Sequencing

The evolution of sequencing technologies dramatically reduced the cost and time required for genomic analysis, making large-scale projects feasible:

- Sanger Sequencing (1977): The first generation of DNA sequencing technology, requiring significant time and resources [18]

- Next-Generation Sequencing (2000s): Automated sequencing performing many reactions simultaneously, offering "ultra-high throughput, scalability and speed" [18]

- Nanopore Sequencing (2010s): Enabled real-time analysis of long DNA or RNA fragments by monitoring electrical current changes as molecules pass through protein pores [18]

- Portable Sequencing (2010s): Miniaturized devices like the MinION sequencer allowed "point-of-care testing" at patient bedsides rather than central laboratories [18]

These technological advances facilitated the transition from reading genomes to writing and editing them, with CRISPR and synthetic biology enabling precise genetic modifications that were previously unimaginable [17].

The Chemical Biology Platform: Integrating Disciplines for Translational Success

Conceptual Framework and Implementation

The chemical biology platform emerged in approximately 2000 as an organizational response to leverage genomic information, combinatorial chemistry, improvements in structural biology, high-throughput screening, and genetically manipulable cellular assays [1]. This platform connects a series of strategic steps to determine whether newly developed compounds could translate into clinical benefit using translational physiology [1].

Chemical biology is defined as "the study and modulation of biological systems, and the creation of biological response profiles through the use of small molecules that are often selected or designed based on current knowledge of the structure, function, or physiology of biological targets" [1]. Unlike traditional approaches that relied on trial-and-error, even when using high-throughput technologies, chemical biology focuses on selecting target families and incorporates systems biology approaches—including transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and network analyses—to understand how protein networks integrate [1].

The platform's main advantage lies in its use of multidisciplinary teams to accumulate knowledge and solve problems, often relying on parallel processes to accelerate timelines and reduce costs for bringing new drugs to patients [1]. This approach represents a mechanism-based means to advance clinical medicine that persists in both academic and industry-focused research [1].

The Chemical Biology-Medicinal Chemistry Continuum

The integration of chemical biology with medicinal chemistry has created a powerful continuum for drug discovery [20]. Chemical biology, "sitting at the interface of many disciplines," has emerged as a major contributor to understanding biological systems and has become an integral part of drug discovery [20]. The blurring of boundaries between disciplines has created new opportunities to probe and understand biology, with both fields playing key roles in driving innovation toward transformative medicines [20].

This continuum leverages the design and synthesis of novel compounds from medicinal chemistry with the biological systems expertise of chemical biology, creating a synergistic relationship that enhances target identification, validation, and therapeutic development.

Modern Experimental Approaches and Protocols

Contemporary Translational Research Workflows

Modern translational research integrates multiple approaches to bridge basic discoveries with clinical applications, exemplified by several contemporary research programs:

Digestive Physiology Research Protocol

Mark Donowitz's research on diarrheal diseases demonstrates a progressive translational workflow:

- Initial Clinical Observation: Sodium absorption identified as critical in gut function [21]

- Animal Model Studies: Investigation using mouse and rabbit models [21]

- Cellular Studies: Transition to cell-based systems [21]

- Human Organoid Systems: Application of human intestinal cell culture models to understand pathophysiology and potential treatments [21]

- Therapeutic Development: Generation of two promising therapies—a drug entering human trials and a peptide to enhance sodium absorption [21]

Comparative Physiology Research Protocol

Lara do Amaral-Silva's approach to studying stress tolerance adaptations:

- Identification of Animal Adaptations: Focus on species with unique abilities to overcome stressors that cause human health issues (e.g., bullfrogs, birds, Tegu lizards tolerating prolonged hypoxia) [21]

- Mechanistic Studies: Investigation of physiological mechanisms (e.g., NMDA receptors in maintaining brain health during hypoxia) [21]

- Comparative Analysis: Examination of physiologically comparable traits (e.g., birds with high glucose and insulin resistance resembling human type 2 diabetes) [21]

- Therapeutic Insight Translation: Application of mechanistic understanding to human treatment approaches [21]

Advanced Methodologies in Modern Drug Discovery

Artificial Intelligence-Accelerated Virtual Screening

Recent advances in computational approaches have revolutionized early drug discovery:

- Platform Architecture: Development of open-source artificial intelligence-accelerated virtual screening platforms integrating active learning techniques for efficient compound triage [22]

- Screening Scale: Capability to screen multi-billion compound libraries against unrelated targets (e.g., ubiquitin ligase KLHDC2 and human voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.7) [22]

- Performance Metrics: High hit rates (14% for KLHDC2, 44% for NaV1.7) with single-digit micromolar binding affinities [22]

- Time Efficiency: Screening completion in less than seven days using high-performance computing clusters [22]

- Validation: Experimental confirmation via high-resolution X-ray crystallography validating predicted docking poses [22]

Functional Genomics and Spatial Transcriptomics

Contemporary approaches leverage genomic technologies for enhanced target identification:

- Functional Genomics: Examination of how differences in genomes influence disease, providing crucial information for developing new diagnosis methods and therapies [18]

- Spatial Transcriptomics: Development of high-resolution ex vivo drug discovery platforms using precision-cut tissue samples (e.g., lung samples from healthy and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients) to build reliable, predictive models for drug development [23]

- Remote Sampling Protocols: Creation of home-based collection methods with RNA preservation reagents (e.g., for human milk) to enable large-scale transcriptome studies without immediate ultra-cold storage requirements [23]

Research Reagent Solutions for Translational Studies

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Their Applications

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Human Organoids [21] | Cell culture models from normal human tissues | Study digestive physiology and pathophysiology |

| Reporter Gene Assays [1] | Assess signal activation from ligand-receptor engagement | Screen potential therapeutic compounds |

| Voltage-Sensitive Dyes [1] | Measure ion channel activity | Neurological and cardiovascular drug target screening |

| Monoclonal Antibodies [16] | Recognize single antigens with high specificity | Diagnostics, research, and targeted cancer therapies |

| RNA Preservation Reagents [23] | Stabilize RNA in remote collection protocols | Large-scale transcriptome sequencing studies |

| Precision-Cut Tissue Slices [23] | Ex vivo modeling of disease states | Drug testing in living human tissue samples (e.g., IPF) |

| Knockout Mouse Models [16] | Study gene function and disease progression | Target validation and disease mechanism studies |

The journey from clinical biology to the genomic revolution represents a fundamental transformation in how researchers approach therapeutic development. The integration of chemical biology platforms with translational physiology has created a robust framework for modern drug discovery, enabling more efficient target identification, validation, and clinical translation [1]. This convergence of disciplines—spanning molecular biology, genomics, computational science, and systems biology—has accelerated the pace of therapeutic innovation while addressing the challenges of demonstrating clinical benefit [1].

The continued evolution of these approaches, particularly through artificial intelligence-accelerated screening [22], functional genomics [18], and sophisticated model systems [21] [23], promises to further enhance our ability to translate basic biological insights into transformative medicines. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this historical trajectory and the current technological landscape is essential for navigating the future of therapeutic innovation and addressing the complex health challenges of tomorrow.

The central dogma of molecular biology, first articulated by Francis Crick in 1958, establishes the fundamental framework for information flow in biological systems. In its original form, it posits that sequential information can be transferred from nucleic acid to nucleic acid, or from nucleic acid to protein, but once information has passed into protein, it cannot flow back to nucleic acid [24]. This principle governs the core operations of molecular biology: DNA replication, transcription of DNA to RNA, and translation of RNA into protein. While often simplified to "DNA makes RNA, and RNA makes protein," Crick's original formulation specifically emphasized the unidirectional nature of information transfer from nucleic acids to proteins [24].

For chemical biologists and drug discovery scientists, this framework provides the essential molecular context for understanding how genetic information manifests as physiological function and dysfunction. The field of chemical biology operates precisely at this interface, using small molecules and chemical tools to study and modulate biological systems [1]. By understanding the detailed mechanisms governing information flow, researchers can design targeted interventions that correct pathological information transfer errors responsible for disease states. This mechanistic understanding forms the foundation of modern drug development, particularly in the era of precision medicine, where therapies are designed to target specific molecular pathways in defined patient populations [1].

Recent research has continued to refine our understanding of the central dogma, revealing unexpected complexities in how genetic information flows through biological systems. For instance, the discovery of DNA polymerase θ (Polθ) in human cells, which possesses robust reverse transcriptase activity, demonstrates that RNA-templated DNA repair occurs in mammalian systems, expanding the traditional boundaries of information flow [25]. Similarly, work on group II self-splicing introns by Dr. Anna Pyle's laboratory has illuminated the three-dimensional molecular architecture and catalytic mechanisms that enable these "genetic parasites" to excise themselves from RNA transcripts without protein assistance [26]. These advances not only deepen our fundamental knowledge but also create new opportunities for therapeutic intervention through chemical biology approaches.

The Molecular Machinery of Information Flow: Key Processes and Experimental Methodologies

DNA Replication and Transcription

DNA replication represents the fundamental process of duplicating genetic information to provide for the progeny of any cell. This process is executed by a complex group of proteins called the replisome, which performs the replication of information from the parent strand to the complementary daughter strand [24]. The fidelity of this process is essential for maintaining genetic integrity across cell generations.

Transcription entails the transfer of information from DNA to RNA, wherein a section of DNA serves as a template for assembling a new piece of messenger RNA (mRNA). This process requires sophisticated molecular machinery, including RNA polymerase and transcription factors [24]. In eukaryotic cells, the initial product is pre-mRNA, which must undergo processing—including addition of a 5' cap, poly-A tail, and splicing—to become mature mRNA. Alternative splicing mechanisms significantly expand the diversity of proteins that can be produced from a single mRNA molecule, adding a layer of complexity to information flow [24].

Table 1: Key Experimental Techniques for Studying DNA Replication and Transcription

| Technique | Application | Key Insights Provided |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Determining 3D structure of replication/transcription complexes | Reveals atomic-level architecture of polymerases, transcription factors, and nucleic acid complexes [26] |

| Photo-cross-linking | Mapping molecular interactions in transcription complexes | Identifies interaction networks between distant domains in RNA structures [26] |

| Nucleotide Analog Interference Mapping/Suppression (NAIM/NAIS) | Identifying functionally critical atoms in RNA | Maps atoms essential for splicing and catalytic activity in self-splicing introns [26] |

| Reporter Gene Assays | Assessing signal activation in response to ligand-receptor engagement | Measures transcriptional activity and signal transduction pathways in live cells [1] |

Translation and Protein Synthesis

Translation represents the final step of information transfer from nucleic acid to protein, wherein the genetic code is converted into functional polypeptides. The ribosome reads mRNA triplet codons, typically beginning with an AUG initiator methionine codon. Initiation and elongation factors facilitate the bringing of aminoacylated transfer RNAs (tRNAs) into the ribosome-mRNA complex, matching the codon in the mRNA to the anti-codon on the tRNA [24]. Each tRNA carries the appropriate amino acid residue to add to the growing polypeptide chain.

The complexity of protein formation extends far beyond the simple translation of nucleotide sequences. As amino acids incorporate into the growing peptide chain, the chain begins folding into its correct three-dimensional conformation—a process critical for biological function. Translation terminates at stop codons (UAA, UGA, or UAG), after which the nascent polypeptide chain typically requires additional processing to achieve functional maturity [24]. This includes chaperone-assisted folding, excision of internal segments (inteins), cleavage into multiple sections, cross-linking, and attachment of cofactors such as haem (heme) [24].

Table 2: Advanced Methodologies for Studying and Engineering Translation

| Methodology | Principle | Research/Drug Discovery Application |

|---|---|---|

| Flexizyme System | Artificial ribozyme that charges tRNA with diverse amino/hydroxy acids | Genetic code reprogramming for incorporation of non-natural amino acids [26] |

| Backbone-Cyclized Peptide Synthesis | In vitro translation of linear precursors that self-arrange into cyclic structures | Production of peptides with enhanced rigidity, proteolytic stability, and membrane permeability [26] |

| High-Content Multiparametric Cellular Analysis | Automated microscopy and image analysis to quantify multiple cellular events | Assessment of cell viability, apoptosis, cell cycle, protein translocation, and phenotypic profiling [1] |

| Patch-Clamp Techniques & Voltage-Sensitive Dyes | Direct measurement of ion channel activity | Screening neurological and cardiovascular drug targets [1] |

Chemical Biology Approaches to Manipulate Information Flow

Expanding the Genetic Code

Chemical biology has developed sophisticated approaches to reprogram the central dogma for both basic research and therapeutic applications. Dr. Hiroaki Suga's work on genetic code reprogramming demonstrates how the standard translational machinery can be engineered to incorporate non-natural amino acids—structurally modified amino acids with novel physicochemical and biological properties [26]. This approach reassigns codons for natural amino acids to non-natural amino acids using a flexizyme-based in vitro translation system.

The experimental workflow for genetic code reprogramming involves several key steps. First, natural aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARSs) are removed from a reconstituted, cell-free translation system derived from Escherichia coli, leaving their cognate tRNAs uncharged. These uncharged tRNAs, called vacant codons, are then reassigned to desired non-natural amino acids using the flexizyme ribozyme, which charges tRNA with amino or hydroxy acids esterified with a 3,5-dinitrobenzyle (DBE) group [26]. A notable advantage of this system is that the aminoacylation reaction is virtually independent of the amino acid side chain, allowing virtually any amino acid to be charged onto any desired tRNA.

To maximize the variety of incorporatable amino acids, researchers artificially divide the codon box by exploiting redundancy in the genetic code. For example, while the codons GUU, GUC, GUA, and GUG all normally encode valine, GUU and GUC can be reprogrammed for p-methoxyphenyllactic acid (mFlac), while GUA and GUG triplets remain assigned to valine [26]. This approach enables the ribosomal synthesis of diverse non-natural peptides and even polyesters, expanding the chemical space available for drug discovery and biomaterial development.

Diagram 1: Genetic code reprogramming workflow

Engineering Novel Protein Architectures

The ability to reprogram the genetic code enables the synthesis of proteins with novel architectures and enhanced therapeutic properties. One notable application is the synthesis of backbone-cyclized peptides, which demonstrate enhanced structural rigidity, proteolytic stability, and membrane permeability compared to their linear counterparts [26]. The experimental protocol involves designing a DNA template that encodes a linear precursor peptide composed of a cysteine-protein dipeptide sequence followed by a glycolic acid sequence (C-P-HOG). When this template is transcribed and translated in vitro, expression of the linear peptide bearing the C-P-HOG sequence results in spontaneous self-rearrangement into a C-terminal diketopiperadine-thioester, generating a cyclized peptide non-enzymatically.

Remarkably, this entire process—including transcription of the DNA template, translation of the peptide, and peptide cyclization—occurs in a single reaction tube, streamlining production [26]. This methodology has enabled the construction of comprehensive libraries of backbone-cyclized peptides for rapid screening of inhibitors against functionally important enzymes. Such approaches exemplify how chemical biology leverages understanding of the central dogma to create powerful platforms for drug discovery, particularly for targets that have proven difficult to address with conventional small molecules or biologics.

Physiological Context: Integrating Molecular Information into Biological Systems

From Molecular Information to Physiological Function

Physiology provides the essential biological context in which chemical tools and principles are applied to understand and influence living systems. The chemical biology platform recognizes that molecular-level information gains functional meaning only when integrated across multiple biological levels—from molecules to cells to organs to populations [1]. This integrative perspective forms the core of translational physiology, which examines biological functions across these multiple levels to bridge laboratory discoveries with clinical applications.

The critical importance of physiological context becomes evident when considering drug development failures. Many compounds that show potent activity against isolated molecular targets fail to demonstrate clinical benefit in patients because of the complex physiological environments in which they must operate [1]. The chemical biology platform addresses this challenge through a multidisciplinary approach that accumulates knowledge and solves problems using parallel processes to accelerate the translation of basic discoveries into clinical applications. This approach has evolved significantly since the 1960s, when the Kefauver-Harris Amendment mandated proof of efficacy from adequate and well-controlled clinical trials, fundamentally changing drug development paradigms [1].

Physiological Validation in Drug Discovery

The chemical biology platform incorporates physiological validation at multiple stages of drug development. Douglas's adaptation of Koch's postulates for drug development outlines a four-step framework for establishing clinical relevance: (1) identify a disease parameter (biomarker); (2) demonstrate that the drug modifies that parameter in an animal model; (3) show that the drug modifies the parameter in a human disease model; and (4) demonstrate dose-dependent clinical benefit that correlates with similar changes in the biomarker [1]. This systematic approach bridges the gap between preclinical findings and clinical outcomes, increasing the efficiency of decision-making before progressing to costly Phase IIb and III trials.

The emergence of Clinical Biology departments in pharmaceutical companies during the 1980s represented an early organized effort to focus on translational physiology [1]. These interdisciplinary teams brought together preclinical physiologists, pharmacologists, and clinical pharmacologists to identify human disease models and biomarkers that could more easily demonstrate drug effects before advancing to large-scale trials. Effective disease models must possess the biomarker of interest, have clinically monitorable symptoms, and demonstrate a relationship between biomarker concentration and clinical manifestations of the condition [1].

Diagram 2: Physiological validation framework in drug discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

The experimental approaches discussed require specialized research reagents and platform technologies. The following table details key solutions essential for investigating and manipulating the central dogma.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Central Dogma Investigation

| Research Reagent | Composition/Principle | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Reconstituted Cell-Free Translation System | E. coli extract with removed aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases | Enables genetic code reprogramming by providing translational machinery without native charging activity [26] |

| Flexizyme Ribozyme | Artificial ribozyme that charges tRNA with diverse amino/hydroxy acids esterified with DBE group | Facilitates charging of tRNAs with non-natural amino acids independent of side chain type [26] |

| High-Throughput Screening Assays | Combinatorial chemistry libraries combined with automated cellular or biochemical assays | Enables rapid screening of compound libraries against therapeutic targets [1] |

| Multiparametric Cellular Analysis Systems | Automated microscopy combined with image analysis algorithms | Quantifies multiple cellular events (viability, apoptosis, protein translocation) in response to perturbations [1] |

| Group II Intron Ribozymes | Self-splicing ribozymes purified from organisms like Oceanobacillus iheyensis | Provides model system for studying RNA structure, catalysis, and potential gene therapy vectors [26] |

| Backbone-Cyclized Peptide Libraries | DNA templates encoding C-P-HOG sequences that cyclize post-translationally | Generates diverse peptide libraries with enhanced stability for inhibitor screening [26] |

The central dogma of molecular biology continues to provide an essential framework for understanding information flow in biological systems, while chemical biology approaches offer powerful methods to manipulate this flow for therapeutic purposes. Recent discoveries, such as the reverse transcriptase activity of human Polθ and the development of flexizyme systems for genetic code reprogramming, have expanded our understanding of how genetic information can be stored, transferred, and manipulated [26] [25]. These advances create new opportunities for therapeutic intervention through chemical biology approaches that target specific steps in information flow.

The integration of physiological context remains paramount for successful translation of these discoveries into clinical benefits. The chemical biology platform, with its emphasis on multidisciplinary teamwork and systematic validation across biological scales, provides an organizational framework for bridging the gap between molecular insights and patient care [1]. As our understanding of the central dogma continues to evolve, so too will our ability to design precisely targeted interventions that correct pathological information flow in disease states, ultimately advancing the goals of precision medicine and improving therapeutic outcomes for patients.

The Modern Toolset: From Chemical Probes to AI-Driven Discovery

Targeted protein degradation (TPD) represents a paradigm shift in chemical biology and drug discovery, moving beyond traditional binding-based inhibition toward active removal of disease-driving proteins [27]. This approach has unlocked therapeutic possibilities for previously “undruggable” targets, including transcription factors like MYC and STAT3, mutant oncoproteins such as KRAS G12C, and scaffolding molecules lacking conventional binding pockets [27]. Among TPD strategies, proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) have emerged as a leading platform, with the first molecule entering clinical trials in 2019 and progression to Phase III completion by 2024 [27].

The significance of PROTAC technology lies in its fundamental reimagining of pharmacological intervention. Traditional small-molecule inhibitors operate through occupancy-driven pharmacology, requiring sustained high drug concentrations to maintain target inhibition [28]. By contrast, PROTACs function through event-driven pharmacology, catalytically inducing protein degradation and allowing for sub-stoichiometric activity [28]. This mechanistic difference provides unique advantages in overcoming drug resistance, targeting proteins lacking functional pockets, and achieving prolonged pharmacological effects despite shorter exposure times [29] [28].