Building a Robust Comparative Chemical Genomics Pipeline for Antimicrobial Resistance Profiling

This article provides a comprehensive guide for developing and implementing a comparative chemical genomics pipeline to study antimicrobial resistance mechanisms.

Building a Robust Comparative Chemical Genomics Pipeline for Antimicrobial Resistance Profiling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for developing and implementing a comparative chemical genomics pipeline to study antimicrobial resistance mechanisms. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of using chemical-genetic interactions to probe essential bacterial functions and identify resistance genes. The content details methodological workflows for high-throughput screening, from experimental design and data acquisition to normalization and phenotypic profiling. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance data quality and reproducibility, and concludes with rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analysis of pipeline performance. By integrating these elements, the article serves as a holistic resource for leveraging chemical genomics to uncover novel drug targets and combat the growing threat of antibiotic resistance.

Laying the Groundwork: Principles of Chemical Genomics in Resistance Research

Defining Chemical-Genomic Interactions and Their Role in Probing Essential Functions

Chemical-genomic interactions represent a powerful framework in systems biology that systematically measures the quantitative fitness of genetic mutants when exposed to chemical or environmental perturbations [1]. These interactions are foundational to chemical genomics, which the systematic screening of targeted chemical libraries of small molecules against individual drug target families with the ultimate goal of identifying novel drugs and drug targets [2]. In the specific context of resistance research, profiling these interactions on a genome-wide scale enables researchers to delineate the complete cellular response to antimicrobial compounds, revealing not only the primary drug target but also the complex networks of genes involved in drug uptake, efflux, detoxification, and resistance acquisition [3].

The core principle underlying chemical-genomic interaction screening is that gene-drug pairs exhibit distinct, measurable fitness phenotypes that can be categorized. A negative chemical-genetic interaction (or synergistic interaction) occurs when the combination of a gene deletion and drug treatment results in stronger growth inhibition than expected. Conversely, a positive interaction (or suppressive interaction) appears when the genetic mutation alleviates the drug's inhibitory effect [3]. These interaction profiles form unique functional signatures that can connect unknown genes to biological pathways and characterize the mechanism of action of unclassified compounds, providing a powerful map for navigating biological function and chemical response in resistance research.

Experimental Protocols for Chemical-Genomic Screening

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening with Pooled Mutant Libraries

This protocol details the steps for conducting a chemical-genomic screen using a pooled, barcoded knockout library to identify genes involved in antibiotic resistance.

Pre-screening Preparation

- Library Selection: Utilize a comprehensive mutant library such as the E. coli KEIO collection (for bacteria) or the Yeast Knockout Collection (for fungi) [1].

- Culture Inoculation: Grow the pooled mutant library in appropriate rich medium to mid-exponential phase.

- Critical: Ensure the culture is in the active growth phase for consistent assay performance.

- Compound Preparation: Prepare a dilution series of the antimicrobial compound of interest in the experimental medium. Include a no-drug control.

Screening Execution

- Sample Dilution: Dilute the pooled library culture into fresh medium containing the predetermined sub-inhibitory concentration (e.g., IC10-IC30) of the antibiotic and into a no-drug control medium.

- Incubation: Allow the cultures to grow for a specified number of generations (typically 5-20) to ensure sufficient population dynamics for detection.

- Harvesting: Collect cell pellets by centrifugation for genomic DNA extraction.

Post-screening Analysis

- DNA Extraction and Amplification: Isolate genomic DNA from both the drug-treated and control samples. Amplify the unique molecular barcodes of each mutant via PCR.

- Sequencing: Subject the amplified barcode pools to high-throughput sequencing.

- Fitness Calculation: For each mutant, calculate the fitness score (typically an S-score) by comparing its relative abundance in the drug-treated pool to its abundance in the control pool, using an analysis pipeline such as ChemGAPP [1].

Protocol 2: Mechanism of Action Deconvolution via Haploinsufficiency and Overexpression Profiling

This protocol uses modulated gene dosage of essential genes to pinpoint the direct protein target of a compound, which is crucial for understanding and countering resistance.

Strain Construction

- For essential gene knockdown in bacteria, employ a CRISPRi library targeting essential genes [3].

- For essential gene overexpression, use a regulated ORF overexpression library.

- For haploinsufficiency profiling in diploid organisms, use a heterozygous deletion mutant library.

Screening Process

- Assay Setup: Treat the library with the compound at a concentration near its minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC).

- Phenotyping: Measure the fitness of each strain in the presence of the drug relative to a no-drug control. In HIP assays, reduced fitness (haploinsufficiency) indicates that the gene product is likely the drug target. In overexpression assays, increased fitness suggests the overproduced protein is sequestering the drug [3].

- Data Integration: Combine results from knockdown/overexpression screens with data from non-essential gene deletion screens to build a comprehensive model of the drug's mechanism of action and the cell's resistance network.

Protocol 3: Data Analysis with ChemGAPP

The ChemGAPP (Chemical Genomics Analysis and Phenotypic Profiling) pipeline is a dedicated software for processing and analyzing high-throughput chemical genomic data [1].

Data Input and Curation

- Compile raw colony size data from image analysis software (e.g., Iris) into the required input format.

- Use ChemGAPP's quality control measures, including a Z-score test to identify outlier or missing colonies and a Mann-Whitney test to check for reproducibility between replicate plates [1].

Normalization and Scoring

- Perform plate normalization to correct for systematic noise like the "edge effect" and to make colony sizes comparable across different plates and conditions.

- Calculate robust fitness scores (S-scores) for each gene mutant under each chemical condition.

Profile Generation and Clustering

- Generate phenotypic profiles for each mutant based on its fitness scores across all screened conditions.

- Use hierarchical clustering to group mutants with similar phenotypic profiles, thereby functionally annotating uncharacterized genes and reconstituting biological pathways relevant to resistance [1].

Quantitative Data from Chemical-Genomic Studies

Table 1: Categorization of Chemical-Genetic Interaction Phenotypes

This table defines the standard classes of chemical-genetic interactions observed in high-throughput screens, which are fundamental for data interpretation in resistance research.

| Interaction Type | Genetic Background | Observed Phenotype | Biological Interpretation in Resistance Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synergistic (Negative) | Gene Deletion | Greater than expected growth defect | Gene product mitigates drug toxicity; loss increases susceptibility. |

| Suppressive (Positive) | Gene Deletion | Less than expected growth defect | Gene product promotes drug toxicity; loss confers resistance. |

| Haploinsufficiency | Reduced essential gene dosage (HIP) | Increased drug sensitivity | Gene product is the direct or indirect target of the compound. |

| Overexpression Suppression | Increased gene dosage | Increased drug resistance | Overproduced protein is the drug target or a resistance factor. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical-Genomic Screens

A list of essential materials and tools required for setting up and executing chemical-genomic experiments focused on resistance.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Utility | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic Mutant Library | Provides a collection of defined mutants for genome-wide screening. | KEIO collection (E. coli), Yeast Knockout collection [1]. |

| CRISPRi/CRISPRa Library | Enables knockdown or activation of essential genes for target deconvolution. | dCas9-based essential gene library [3]. |

| Barcoded Strain Collections | Allows for multiplexed fitness assays of pooled mutants via sequencing. | TAGged ORF libraries [3]. |

| Image Analysis Software | Quantifies colony-based phenotypes (size, opacity) from high-resolution plate images. | Iris [1]. |

| Data Analysis Pipeline | Processes raw data, performs QC, normalizes, and calculates fitness scores. | ChemGAPP [1]. |

Workflow Visualization

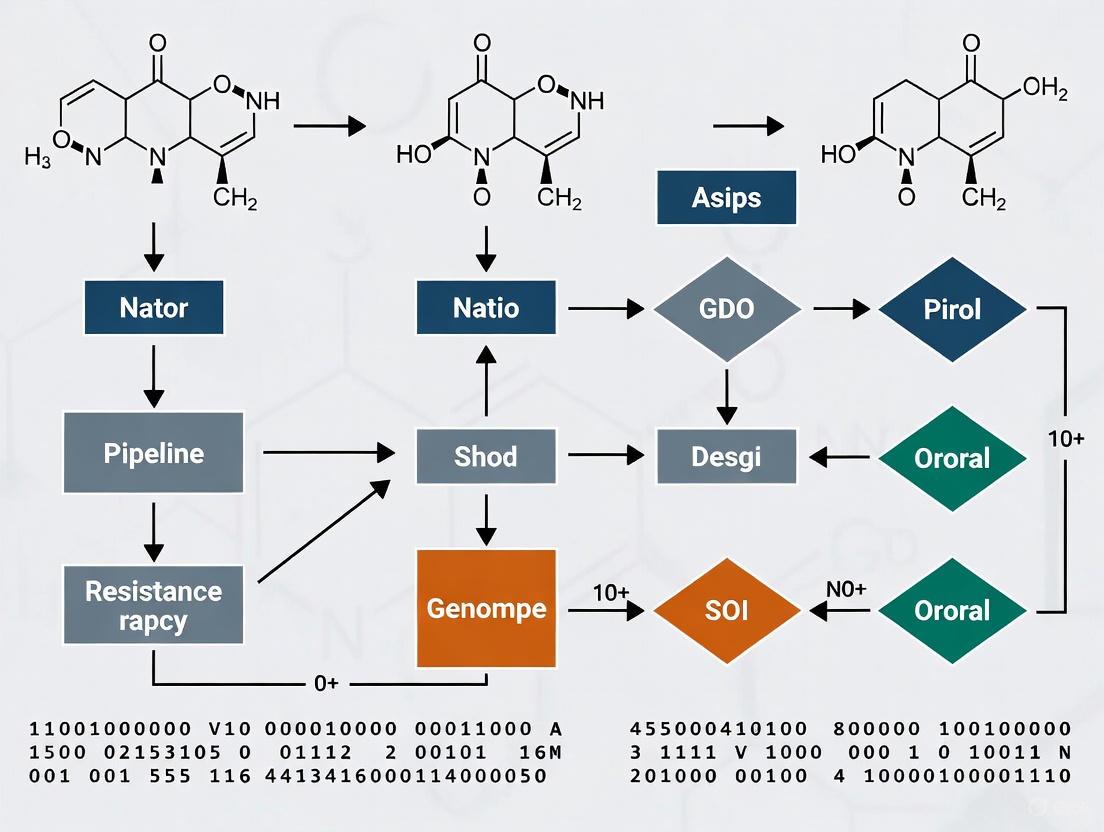

Diagram 1: Chemical-Genomic Screening and Analysis Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the integrated experimental and computational pipeline for a chemical-genomic screen, from library preparation to biological insight.

Diagram 2: Interpreting Chemical-Genetic Interaction Outcomes

This diagram maps the decision process for interpreting different classes of chemical-genetic interactions to infer gene function and drug mechanism.

Application in Resistance Research

In the context of comparative chemical genomics for resistance research, the protocols and data described herein enable the systematic dissection of resistance mechanisms. By performing parallel chemical-genomic screens across different bacterial species or clinical isolates, researchers can identify conserved resistance networks and species-specific vulnerabilities. The fitness profiles, or chemogenomic signatures, of different drugs can be clustered to identify compounds with similar mechanisms of action, even in the face of emerging resistance [3]. Furthermore, this approach can reveal patterns of cross-resistance (where a mutation confers resistance to multiple drugs) and collateral sensitivity (where resistance to one drug increases sensitivity to another), providing a rational basis for designing optimized, resistance-suppressing combination therapies [3]. The application of standardized protocols and analysis tools like ChemGAPP ensures that such comparative studies are robust, reproducible, and directly informative for the ongoing battle against antimicrobial resistance.

The identification of orthologous sequence elements is a foundational task in comparative genomics, forming the basis for phylogenetics, sequence annotation, and a wide array of downstream analyses in computational evolutionary biology [4]. Synteny, in its modern genomic interpretation, defines conserved genomic intervals that harbor multiple homologous features in preserved order and relative orientation [4]. This conservation of gene order provides a strong indication of homology at the level of genome organization, paralleling how sequence similarity infers homology at the gene level.

Anchor markers serve as unambiguous landmarks that identify positions in two or more genomes that are orthologous to each other. The theoretical foundation for anchor-based approaches relies on identifying "sufficiently unique" sequences in each genome that can be reliably mapped across species [4]. These anchors enable researchers to delineate regions of conserved gene order despite sequence divergence, duplication events, and other genome rearrangements that complicate direct sequence comparison alone.

Within chemical genomics and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) research, synteny and anchor markers provide a powerful framework for identifying conserved resistance mechanisms across bacterial species, tracing the evolutionary history of resistance genes, and discovering new potential drug targets by comparing pathogenic and non-pathogenic organisms.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

Formal Definitions and Properties

The theoretical framework for synteny detection begins with formal definitions of uniqueness and anchor matches [4]. A genome G is represented as a string over the DNA alphabet {A,C,G,T} with additional characters marking fragment ends. The set S(G) comprises all contiguous DNA sequences present in G, including reverse complements.

Definition 1: Uniqueness A string (w \in S(G)) is (d0)-unique in G if [ \min{w' \in S(G\setminus {w})} d(w,w') > d_0 ] where (d) is a metric distance function derived from sequence alignments, and (G\setminus {w}) represents the genome with query (w) removed from its location of origin [4].

Definition 2: Anchor Match For two genomes G and H, (w \in S(G)) and (y \in S(H)) are anchor matches if: [ d(w,y) < d(w',y) \quad \forall w' \in S(G\setminus {w}) ] and [ d(w,y) < d(w,y') \quad \forall y' \in S(H\setminus {y}) ] This ensures that w and y define unique genomic locations up to slight shifts within their alignment [4].

Algorithmic Framework for Synteny Detection

Current approaches for genome-wide synteny detection typically involve three computational stages [4]:

- Pre-computation of anchor candidates in each genome through identification of "sufficiently unique" sequences

- Pairwise cross-species comparisons limited to anchor candidates to identify rearrangements

- Assessment of consistent synteny across multiple species and phylogenetic placement of rearrangement events

The critical innovation in modern synteny detection is the annotation-free approach that uses k-mer statistics to identify moderate size regions that serve as initial anchor candidates, followed by verification through sequence comparison to confirm that these candidates have no other similar matches in their own genome [4].

Workflow Integration for Chemical Genomics

Synteny-Driven Chemical Genomics Pipeline

The integration of synteny analysis with chemical genomics creates a powerful pipeline for antimicrobial resistance research. The workflow begins with genomic data from multiple bacterial species and progresses through systematic stages to identify and validate potential drug targets.

Synteny to resistance research workflow illustrating the pipeline from genomic data to target prioritization.

Integration with Resistance Gene Analysis

The gSpreadComp workflow demonstrates how comparative genomics can be integrated with risk classification for antimicrobial resistance research [5]. This approach combines taxonomy assignment, genome quality estimation, antimicrobial resistance gene annotation, plasmid/chromosome classification, virulence factor annotation, and downstream analysis into a unified workflow. The key innovation is calculating gene spread using normalized weighted average prevalence and ranking resistance-virulence risk by integrating microbial resistance, virulence, and plasmid transmissibility data [5].

The relationship between synteny analysis and chemical-genetic screening creates a virtuous cycle for resistance gene identification:

Data integration cycle showing how synteny analysis and chemical-genetics inform each other in resistance research.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Synteny Anchor Detection

Principle: Identification of sufficiently unique genomic sequences that can serve as reliable anchors for cross-species comparisons without relying on gene annotations.

Materials:

- Genomic sequences in FASTA format

- High-performance computing cluster

- AncST software or equivalent synteny detection tool [4]

Procedure:

Pre-computation of anchor candidates (performed independently for each genome):

- Calculate k-mer frequency distributions across the genome

- Identify regions with low similarity to other genomic regions

- Apply uniqueness threshold based on sequence distance metric (d_0)

- Generate initial set of anchor candidates meeting uniqueness criteria

Cross-species anchor verification:

- Perform pairwise comparisons limited to anchor candidates

- Identify reciprocal best matches between genomes

- Verify anchor matches meet Definition 2 criteria

- Filter anchors with ambiguous mapping positions

Synteny block construction:

- Cluster anchors into syntenic blocks based on genomic proximity

- Define block boundaries using statistical approaches

- Calculate conservation scores for each syntenic block

- Output synteny maps for downstream analysis

Technical Notes: For closely related genomes, annotation-free approaches often outperform annotation-based methods. For distantly related genomes, incorporating protein sequence similarity may improve sensitivity [4].

Protocol 2: Chemical-Genetic Screening for Resistance Gene Identification

Principle: Systematic assessment of gene-chemical interactions using CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) to identify genes essential for survival under antibiotic stress.

Materials:

- Pooled CRISPRi library targeting essential genes [6]

- Chemical inhibitors including antibiotics at sublethal concentrations

- Growth media appropriate for bacterial strains

- Sequencing platform for guide RNA abundance quantification

Procedure:

Library preparation and validation:

- Design sgRNAs targeting putative essential genes (4 perfect-match and 10 mismatch spacers per gene)

- Include 1000 non-targeting control sgRNAs

- Clone library into appropriate CRISPRi vector system

- Transform into target bacterial strain (e.g., A. baumannii ATCC19606)

- Validate library representation and diversity

Chemical-genetic screening:

- Induce CRISPRi knockdown with appropriate inducer

- Add chemical stressors at predetermined sublethal concentrations

- Culture libraries for sufficient generations to observe fitness differences (typically 14+ generations)

- Harvest cells for genomic DNA extraction at multiple time points

Fitness calculation and hit identification:

- Amplify and sequence sgRNA spacer regions

- Calculate abundance changes for each guide

- Determine chemical-gene (CG) scores as median log2 fold change (medL2FC) of perfect guides with chemical treatment compared to induction alone

- Apply statistical thresholds (medL2FC ≥ |1|, p <0.05) for significant interactions

Validation: Confirm key interactions using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays with individual knockdown strains outside the pooled context [6].

Protocol 3: Integration of Synteny and Chemical-Genetic Data

Principle: Leverage evolutionarily conserved genomic regions identified through synteny analysis to prioritize targets from chemical-genetic screens.

Procedure:

Orthology mapping across species:

- Use synteny anchors to establish orthology relationships

- Map essential genes from chemical-genetic screens to syntenic blocks

- Identify conserved essential genes across multiple bacterial species

Resistance network construction:

Target prioritization:

- Rank genes based on conservation across species

- Prioritize genes with strong chemical-gene interactions across multiple antibiotics

- Apply machine learning algorithms to identify chemical-genetic interactions reflective of drug mode of action [3]

Data Presentation and Quantitative Standards

Chemical-Gene Interaction Scoring Metrics

Table 1: Quantitative thresholds for chemical-genetic interaction significance

| Metric | Threshold for Significance | Biological Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG score (medL2FC) | ≥ | 1 | Log2 fold change in mutant abundance | |

| p-value | < 0.05 | Statistical significance of interaction | ||

| Negative CG scores | 73% of significant interactions [6] | Reduced fitness (sensitivity) | ||

| Positive CG scores | 27% of significant interactions [6] | Improved fitness (resistance) | ||

| Genes with significant interactions | 93% of essential genes (378/406) [6] | Breadth of chemical responses |

Synteny Detection Performance Standards

Table 2: Performance benchmarks for synteny detection methods

| Parameter | Annotation-Based | Annotation-Free | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic scope | Better for distant relatives [4] | Superior for close relatives [4] | Choose based on divergence |

| Resolution | Limited by gene number [4] | Higher, not limited by annotations [4] | High-resolution needs |

| Computational intensity | Lower | Higher initial computation [4] | Resource considerations |

| Repetitive element handling | Limited | k-mer based approaches [4] | Repeat-rich genomes |

| Detection sensitivity | Amino acid level boosts distance [4] | DNA level, limited by divergence [4] | Divergent sequences |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for synteny and chemical-genomics studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi Libraries | Pooled essential gene library (406 genes + controls) [6] | High-throughput knockdown screening |

| Chemical Stressors | 45 diverse compounds including antibiotics, heavy metals [6] | Profiling gene-chemical interactions |

| Bioinformatics Tools | AncST (anchor synteny tool) [4], gSpreadComp [5] | Annotation-free synteny detection, risk ranking |

| Sequence Analysis | DAGchainer [4], MCScanX [4] | Annotation-based synteny detection |

| Database Resources | STRING database [6] | Functional enrichment analysis |

| Validation Assays | MIC determination with antibiotic strips [6] | Confirmatory testing of interactions |

Visualization and Data Interpretation Guidelines

Visualizing Synteny-Chemical Genomic Integration

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting the complex relationships between synteny conservation and chemical-genetic interactions. Based on established principles for genomic data visualization [7] [8], the following approaches are recommended:

Circular layouts (Circos plots) effectively display synteny conservation across multiple genomes while integrating chemical-genetic interaction data as additional tracks [8]. Hilbert curves provide a space-filling alternative for large datasets, preserving genomic sequence while visualizing multiple data types [8]. For chemical-genetic interaction networks, hive plots offer superior interpretability compared to traditional hairball networks by using a linear layout to identify patterns [8].

Color and Accessibility Standards

All visualizations must adhere to WCAG 2.1 contrast requirements to ensure accessibility [9] [10] [11]. The specified color palette (#4285F4, #EA4335, #FBBC05, #34A853, #FFFFFF, #F1F3F4, #202124, #5F6368) has been tested for sufficient contrast ratios:

Table 4: Color contrast compliance for visualization elements

| Element Type | Minimum Contrast Ratio | Compliant Color Pairings |

|---|---|---|

| Normal text | 4.5:1 [9] [10] | #202124 on #FFFFFF (21:1), #202124 on #F1F3F4 (15:1) |

| Large text (18pt+) | 3:1 [9] [10] | #EA4335 on #F1F3F4 (4.5:1), #4285F4 on #FFFFFF (8.6:1) |

| Graphical objects | 3:1 [10] | #34A853 on #FFFFFF (4.5:1), #FBBC05 on #202124 (5.5:1) |

| UI components | 3:1 [10] | #EA4335 on #F1F3F4 (4.5:1), #4285F4 on #FFFFFF (8.6:1) |

When creating diagrams with Graphviz, explicitly set fontcolor attributes to ensure sufficient contrast against node background colors, particularly when using the specified color palette.

Understanding the precise mechanisms of antibiotic action and the genetic essentiality of bacterial pathogens forms the cornerstone of modern antimicrobial resistance research. This field integrates classical pharmacology with advanced functional genomics to define how drugs kill bacteria and which bacterial genes are indispensable for survival under various conditions. This knowledge is critical for identifying new drug targets, understanding resistance emergence, and designing strategies to counteract it within a comparative chemical genomics pipeline. These approaches enable researchers to systematically identify vulnerable points in bacterial physiology that can be exploited for therapeutic development, ultimately extending the useful lifespan of existing antibiotics and guiding the creation of novel antimicrobial agents [12] [13] [14].

Drug Mechanism of Action Studies

Fundamental Antibiotic Mechanisms

Antibiotics exert their bactericidal or bacteriostatic effects through specific molecular interactions with key cellular processes. The four primary mechanisms of action include: inhibition of cell wall synthesis, inhibition of protein synthesis, inhibition of nucleic acid synthesis, and disruption of metabolic pathways [12]. The specific molecular targets and drug classes associated with each mechanism are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Fundamental Antibiotic Mechanisms of Action

| Mechanism of Action | Molecular Target | Antibiotic Classes | Key Bactericidal Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition of DNA Replication | DNA gyrase (Topoisomerase II) & Topoisomerase IV | Fluoroquinolones | Causes DNA cleavage and prevents separation of daughter molecules [12]. |

| Inhibition of Protein Synthesis | 30S ribosomal subunit | Aminoglycosides, Tetracyclines | Binds to 16s rRNA, inhibiting translation initiation and causing misreading of mRNA [12]. |

| Inhibition of Cell Wall Synthesis | Penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) | β-lactams, Glycopeptides | Disrupts peptidoglycan cross-linking, leading to cell lysis [12]. |

| Inhibition of Metabolic Pathways | Dihydropteroate synthase, Dihydrofolate reductase | Sulfonamides, Trimethoprim | Blocks folic acid synthesis, inhibiting nucleotide production [12]. |

Protocol: Investigating Antibiotic Mechanism of Action

Title: Experimental Workflow for Elucidating Antibiotic Mechanisms

Objective: To systematically determine the primary mechanism of action of an unknown antimicrobial compound using a combination of phenotypic assays and molecular profiling.

Materials & Reagents:

- Bacterial Strains: Reference strains (e.g., Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213)

- Growth Media: Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB), Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA)

- Test Compound: Stock solution of the investigational antibiotic

- Staining Solutions: SYTOX Green stain, BacLight RedoxSensor Green Vitality Kit

- Molecular Biology Kits: RNA extraction kit, cDNA synthesis kit, qPCR reagents

- Equipment: Spectrophotometer, flow cytometer, qPCR instrument, fluorescence microscope

Procedure:

Time-Kill Kinetics Analysis:

- Prepare logarithmic-phase bacterial cultures (∼1 × 10^6 CFU/mL) in MHB.

- Expose cultures to the test compound at 1×, 4×, and 10× the predetermined MIC.

- Remove aliquots at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 hours, perform serial dilutions in saline, and plate on MHA.

- Incubate plates at 35°C for 16-20 hours and enumerate CFUs.

- Interpretation: Bactericidal activity is defined as ≥3-log10 reduction in CFU/mL at 24 hours compared to initial inoculum.

Membrane Permeability Assessment:

- Harvest bacterial cells from mid-logarithmic phase cultures.

- Resuspend in PBS containing 1 µM SYTOX Green stain.

- Add test compound at 4× MIC and incubate in dark for 30 minutes.

- Analyze fluorescence intensity by flow cytometry (excitation/emission: 504/523 nm).

- Interpretation: Increased fluorescence indicates compromised membrane integrity.

Transcriptional Profiling of Resistance Genes:

- Expose bacterial cultures to sub-inhibitory (½× MIC) concentration of test compound for 2 hours.

- Extract total RNA and synthesize cDNA.

- Perform qPCR using primers for key resistance and stress response genes (fabI, recA, acrB, rpoS, ompF).

- Calculate fold-change in expression using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method relative to untreated control.

- Interpretation: Upregulation of specific efflux pumps or stress responses provides indirect evidence of cellular target.

Morphological Analysis via Microscopy:

- Prepare bacterial smears after 2-hour exposure to test compound at 2× MIC.

- Perform Gram staining and examine under 100× oil immersion lens.

- Interpretation: Filamentation suggests DNA synthesis inhibition; spherical cells indicate cell wall synthesis inhibition.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Include appropriate controls (solvent-only, known mechanism comparators).

- Ensure RNA integrity (RIN >8.0) for transcriptional analyses.

- Standardize inoculum density across all assays to minimize variability.

Conditional Essentiality Analysis

Concepts and Methodologies in Essentiality Screening

Conditional essentiality refers to bacterial genes that are indispensable for growth or survival under specific environmental conditions but may be dispensable under others. This concept is particularly relevant for identifying pathogen-specific drug targets that are only essential during infection [15] [14]. Transposon sequencing (TnSeq) has emerged as a powerful genome-wide approach for mapping these genetic dependencies across diverse experimental conditions [15].

Table 2: Key Genomic Methods for Conditional Essentiality Analysis

| Method | Principle | Applications in Resistance Research | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transposon Sequencing (TnSeq) | High-throughput sequencing of transposon insertion sites to determine fitness defects [15]. | Identification of genes essential for survival under antibiotic stress or during infection [15]. | Conditionally essential gene sets, fitness scores [15]. |

| Gene Replacement and Conditional Expression (GRACE) | Tet-repressible promoter controls remaining allele in diploid pathogens [14]. | Direct assessment of gene essentiality in fungal pathogens like C. albicans [14]. | Essentiality scores, growth defects [14]. |

| Machine Learning Prediction | Random forest classifiers trained on genomic features predict essentiality [14]. | Genome-wide essentiality predictions for genes not covered in experimental screens [14]. | Essentiality probability scores, functional annotations [14]. |

Protocol: TnSeq for Conditional Essentiality Profiling Under Antibiotic Stress

Title: TnSeq Workflow for Mapping Genetic Dependencies

Objective: To identify bacterial genes essential for growth and survival under antibiotic pressure using transposon mutagenesis and high-throughput sequencing.

Materials & Reagents:

- Transposon Mutagenesis Kit: (e.g., EZ-Tn5 Transposase)

- Selection Antibiotics: Appropriate for transposon marker and tested antibiotic

- Growth Media: Tryptic soy broth, Brain Heart Infusion, or other appropriate medium

- DNA Extraction Kit: Certified for high-molecular weight DNA

- Library Preparation Kit: Compatible with Illumina platforms

- Software: TRANSIT, Tn-Seq preprocessor (TPP) [15]

Procedure:

Library Generation and Validation:

- Generate a saturated transposon mutant library by electroporating the transposome complex into the target bacterial strain.

- Plate on selective media and incubate until distinct colonies appear.

- Pool ∼100,000 colonies and harvest biomass for genomic DNA extraction.

- Assess insertion density by pilot sequencing; aim for >25% of possible TA sites with insertions [15].

Experimental Conditioning:

- Inoculate the mutant library into fresh medium containing sub-inhibitory concentration (¼× MIC) of the test antibiotic.

- Include a no-antibiotic control cultured in parallel.

- Passage cultures for at least 12 generations to allow depletion of mutants with fitness defects.

- Harvest biomass by centrifugation at appropriate time points.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Extract genomic DNA from experimental and control samples.

- Fragment DNA using Covaris sonication to ∼300 bp fragments.

- Perform adapter ligation, amplify transposon-chromosome junctions using specific primers.

- Purify amplified products and quantify using Qubit fluorometer.

- Sequence on Illumina platform (minimum 2 million reads per sample).

Bioinformatic Analysis using TRANSIT:

- Pre-process raw sequencing reads with Tn-Seq preprocessor (TPP) to map insertions to reference genome [15].

- Input .wig files into TRANSIT and run resampling analysis with 10,000 permutations [15].

- Normalize counts using TTR normalization [15].

- Identify conditionally essential genes using thresholds: adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 and absolute log2FC ≥ 1 [15].

- Perform functional enrichment analysis on significant gene sets.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Optimize transposition efficiency for each bacterial strain.

- Ensure sufficient library complexity (>100,000 unique mutants).

- Include biological replicates to account for stochastic effects.

- Use pseudocounts (PC=1) in TRANSIT to handle genes with zero counts [15].

Integrated Chemical Genomics Workflow

The synergy between mechanism of action studies and conditional essentiality profiling creates a powerful pipeline for identifying and validating novel drug targets. This integrated approach enables researchers to position candidate compounds within known mechanistic frameworks while identifying the genetic vulnerabilities that dictate their pathogen-specific activity.

Diagram Title: Chemical Genomics Pipeline

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Mechanism and Essentiality Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Application | Function in Research Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| TRANSIT Software | TnSeq data analysis | Statistical analysis of transposon insertion data to identify conditionally essential genes [15]. |

| GRACE Collection | Fungal gene essentiality | Conditional expression mutants for direct testing of gene essentiality in C. albicans [14]. |

| CompareM2 Pipeline | Comparative genomics | Integrated analysis of microbial genomes for resistance genes, virulence factors, and phylogenetic relationships [16]. |

| CARD Database | Antibiotic resistance annotation | Curated resource linking resistance genes to antibiotics and mechanisms [17]. |

| MtbTnDB | Conditional essentiality database | Standardized repository of TnSeq screens for M. tuberculosis [15]. |

| Bakta/Prokka | Genome annotation | Rapid and standardized functional annotation of bacterial genomes [16]. |

The integration of drug mechanism of action studies with conditional essentiality analysis creates a powerful framework for antimicrobial discovery and resistance research. The standardized protocols outlined here enable systematic investigation of how antibiotics kill bacterial cells and which bacterial genes become indispensable under therapeutic pressure. As resistance mechanisms continue to evolve, these approaches will be increasingly valuable for identifying new therapeutic vulnerabilities and developing strategies to overcome multidrug-resistant infections. The continuing development of databases like MtbTnDB and analytical tools like TRANSIT will further enhance our ability to map the complex relationships between chemical compounds and genetic essentiality in pathogenic bacteria [15] [14].

The E. coli Keio Knockout Collection is a systematically constructed library of single-gene deletion mutants, designed to provide researchers with in-frame, single-gene deletion mutants for all non-essential genes in E. coli K-12 [18]. Developed through a collaboration between the Institute for Advanced Biosciences at Keio University (Japan), the Nara Institute of Science and Technology (Japan), and Purdue University, this collection represents a foundational resource for bacterial functional genomics and systems biology [18] [19].

The primary design feature of the Keio collection is the replacement of each targeted open-reading frame with a kanamycin resistance cassette flanked by FLP recognition target (FRT) sites [19]. This design enables the subsequent excision of the antibiotic marker using FLP recombinase, leaving behind a precise, in-frame deletion that minimizes polar effects on downstream genes—a critical consideration for accurate functional analysis [19]. The collection is built in the E. coli K-12 BW25113 background, a strain with a well-defined pedigree that has not been subjected to mutagens, ensuring consistency across experiments [19].

As a resource for systematic functional genomics, the Keio collection facilitates reverse genetics approaches where investigators start with a gene deletion and proceed to analyze the resulting phenotypic consequences, in contrast to forward genetics which begins with a mutant phenotype and seeks its genetic cause [18]. This makes it particularly valuable for comprehensive studies of gene function, including the investigation of antibiotic resistance mechanisms through chemical-genomic profiling [20].

Table 1: Key Specifications of the E. coli Keio Knockout Collection

| Feature | Specification |

|---|---|

| Total Genes Targeted | 4,288 genes [19] |

| Successful Mutants Obtained | 3,985 genes [18] [19] |

| Mutant Format | Two independent mutants per gene [18] |

| Total Strains | 7,970 mutant strains [18] |

| Strain Background | E. coli K-12 BW25113 [18] [19] |

| Selection Marker | Kanamycin resistance cassette [18] [19] |

| Cassette Excision | FLP-FRT system for in-frame marker removal [18] [19] |

| Candidate Essential Genes | 303 genes unable to be disrupted [19] |

Accessing and Utilizing the Keio Collection

Distribution and Availability

The Keio collection is commercially available through distributors such as Horizon Discovery, which provides clones in various formats to accommodate different research needs [18]. Individual clones are supplied as live cultures in 2 mL tubes containing LB medium supplemented with 8% glycerol and the appropriate antibiotic, shipped at room temperature via express delivery [18]. For larger-scale studies, bulk orders of 50 clones or greater, including the entire collection, are provided in 96-well microtiter plates shipped on dry ice via overnight delivery [18]. All stocks should be stored at -80°C immediately upon receipt to maintain viability [18].

It is important to note that as these resources originate from academic laboratories, they are typically distributed in the format provided by the contributing institution with no additional product validation or guarantee [18]. Researchers are encouraged to consult the product manual and associated published articles, or contact the source academic institution directly for troubleshooting [18]. The original construction and distribution of the collection were managed through GenoBase (http://ecoli.aist-nara.ac.jp/) [19].

Experimental Design for Chemical Genomic Screens

The Keio collection enables genome-wide chemical genomic screens that systematically quantify how each gene deletion affects susceptibility to chemical compounds, including antibiotics. The typical workflow involves:

- Pooled Competition Assays: Growing the pooled library of deletion mutants in the presence of a chemical stressor at a sub-inhibitory concentration and tracking mutant abundance over time through sequencing [20].

- Control Experiments: Conducting parallel growth experiments without chemical treatment to establish baseline fitness measurements for each mutant.

- Data Analysis: Calculating chemical-genetic interaction scores as log2 fold changes in mutant abundance between treated and untreated conditions to identify genes where deletion confers sensitivity or resistance.

This approach has been successfully applied to map resistance determinants for diverse antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) in E. coli, revealing distinct genetic networks that influence susceptibility to membrane-targeting versus intracellular-targeting AMPs [20].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for chemical-genomic screening using the Keio collection. The pooled mutant library is grown in the presence of a test compound, followed by DNA extraction, sequencing of molecular barcodes, and computational analysis to identify gene deletions that affect chemical susceptibility.

Integration with Comparative Genomics Pipelines

The CompareM2 Pipeline for Genomic Analysis

In the context of modern resistance research, data generated with the Keio collection can be significantly enhanced through integration with comparative genomics pipelines. CompareM2 is a recently developed genomes-to-report pipeline specifically designed for comparative analysis of bacterial and archaeal genomes from both isolates and metagenomic assemblies [16]. This tool addresses critical bottlenecks in bioinformatics by providing an easy-to-install, easy-to-use platform that automates the complex installation procedures and dependency management that often challenge researchers [16].

CompareM2 incorporates a comprehensive suite of analytical tools for prokaryotic genome analysis, including:

- Quality Control: Assembly-stats and SeqKit for basic genome statistics (genome length, contig counts, N50, GC content) and CheckM2 for assessing genome completeness and contamination [16].

- Functional Annotation: Bakta (default) or Prokka for genome annotation, with additional specialized tools for specific analyses [16].

- Specialized Functional Analysis: InterProScan for protein signature databases, dbCAN for carbohydrate-active enzymes, Eggnog-mapper for orthology-based annotations, Gapseq for metabolic modeling, AntiSMASH for biosynthetic gene clusters, and AMRFinder for antimicrobial resistance genes [16].

- Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Analysis: GTDB-Tk for taxonomic assignment, Mashtree and Panaroo for phylogenetic tree construction, and IQ-TREE 2 for maximum-likelihood trees [16].

The pipeline produces a dynamic, portable report document that highlights the most important curated results from each analysis, making data interpretation accessible even for researchers with limited bioinformatics backgrounds [16]. Benchmarking studies have demonstrated that CompareM2 scales efficiently with increasing input size, showing approximately linear running time with a small slope even when processing genome numbers well beyond the available cores on a machine [16].

Application to Resistance Research

For antibiotic resistance studies, CompareM2 offers several specifically relevant features. The integration of AMRFinder enables comprehensive scanning for known antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors, while MLST calling facilitates multi-locus sequence typing relevant for tracking bacterial transmission and spread [16]. The pathway enrichment analysis through ClusterProfiler can identify metabolic pathways associated with resistance mechanisms [16].

When combined with experimental data from Keio collection screens, CompareM2 enables researchers to contextualize their findings within a broader genomic framework. For instance, resistance genes identified through chemical-genetic profiling can be analyzed for their distribution across bacterial lineages, association with specific genomic contexts, and co-occurrence with other resistance determinants.

Table 2: Key Tools in the CompareM2 Pipeline for Resistance Research

| Tool | Function | Relevance to Resistance Research |

|---|---|---|

| CheckM2 | Assesses genome quality, completeness, and contamination | Ensures high-quality input genomes for reliable analysis [16] |

| AMRFinder | Scans for antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors | Identifies known resistance determinants in genomic data [16] |

| MLST | Calls multi-locus sequence types | Enables tracking of resistant clones and epidemiological spread [16] |

| Bakta/Prokka | Performs rapid genome annotation | Provides foundational gene annotations for functional analysis [16] |

| InterProScan | Scans multiple protein signature databases | Identifies functional domains in resistance-associated proteins [16] |

| Panaroo | Determines core and accessory genome | Identifies genes associated with resistance phenotypes [16] |

| IQ-TREE 2 | Constructs maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees | Reconstructs evolutionary relationships among resistant isolates [16] |

Case Study: Chemical-Genetic Profiling of Antimicrobial Peptide Resistance

Experimental Protocol

A representative application of the Keio collection in resistance research is the chemical-genetic profiling of antimicrobial peptide (AMP) resistance in E. coli, as demonstrated by [20]. The following detailed protocol outlines the key methodological steps:

Step 1: Preparation of Pooled Library

- Grow the entire Keio collection as a pooled culture in Lysogeny Broth (LB) supplemented with 25 µg/mL kanamycin to maintain selection for the deletion cassettes.

- Culture the pool to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5) at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm.

Step 2: Chemical Treatment

- Divide the culture into two aliquots: one for chemical treatment and one as an untreated control.

- Add the antimicrobial peptide (or other chemical compound) to the treatment culture at a predetermined sub-inhibitory concentration that increases the population doubling time by approximately 2-fold [20].

- Maintain the untreated control with an equivalent volume of solvent only (e.g., DMSO).

Step 3: Competitive Growth

- Incubate both cultures for approximately 12 generations under standard growth conditions to allow for competitive growth differences between mutants to manifest.

- Maintain selection with kanamycin throughout the growth period.

Step 4: Sample Processing and Sequencing

- Harvest cells from both treated and control cultures by centrifugation.

- Extract genomic DNA using a method suitable for high-throughput processing (e.g., plate-based extraction kits).

- Amplify the unique molecular barcodes associated with each deletion mutant using primers with Illumina adapter sequences.

- Purify the amplification products and quantify using a fluorometric method.

- Sequence the amplified barcode libraries on an Illumina platform to sufficient depth (typically >100x coverage across the mutant library).

Step 5: Data Analysis

- Map sequence reads to the reference barcode library to determine the abundance of each mutant in treated and control conditions.

- Calculate chemical-genetic interaction scores as the log2 fold change in abundance for each mutant between treatment and control.

- Perform statistical analysis to identify significant interactions, typically using a median log2 fold change threshold of ≥ |1| and p-value < 0.05 [20].

- Conduct functional enrichment analysis using databases like STRING to identify biological pathways enriched among significant hits.

Key Findings and Applications

This chemical-genetic approach applied to AMP resistance revealed several critical insights that demonstrate the power of systematic resource collections like Keio:

- Distinct Resistance Determinants: AMPs with different physicochemical properties and cellular targets showed considerably different resistance determinants, with limited cross-resistance observed only between AMPs with similar modes of action [20].

- Functional Diversity: Genes influencing AMP susceptibility spanned diverse biological processes, with cell envelope functions being significantly overrepresented but the majority of hits having no obvious prior connection to known AMP resistance mechanisms [20].

- Cluster Analysis: Chemical-genetic interaction profiles successfully clustered AMPs according to their modes of action, separating membrane-targeting from intracellular-targeting peptides and identifying those with mixed mechanisms [20].

Figure 2: Logical relationship between chemical-genetic screening and key findings in antimicrobial peptide resistance research. Chemical-genetic interaction profiles derived from Keio collection screens enable clustering of antimicrobial peptides by mode of action, revealing distinct resistance determinants and limited cross-resistance between different classes.

Advanced Applications in Bacterial Research

Expanding to Other Bacterial Systems

The success of the Keio collection as a resource for E. coli functional genomics has inspired similar systematic approaches in other bacterial pathogens. For example, in Acinetobacter baumannii, a Gram-negative pathogen categorized as an 'urgent threat' due to multidrug-resistant infections, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) knockdown libraries have been developed to study essential gene function [6]. These libraries enable high-throughput chemical-genomic screens similar to those possible with the Keio collection, but for essential genes that cannot be simply deleted [6].

A recent chemical genomics study in A. baumannii utilizing a CRISPRi library targeting 406 putatively essential genes revealed that the vast majority (93%) showed significant chemical-gene interactions when screened against 45 diverse chemical stressors [6]. This approach identified crucial pathways for chemical resistance, including the unanticipated finding that knockdown of lipooligosaccharide (LOS) transport genes increased sensitivity to a broad range of chemicals through cell envelope hyper-permeability [6]. Such insights demonstrate how systematic genetic resources can reveal unexpected vulnerabilities in bacterial pathogens that could be exploited for therapeutic development.

Integration with Pan-genome Analysis

Comparative genomics tools like CompareM2 enable researchers to extend insights gained from model systems like E. coli K-12 to diverse bacterial species and strains through pan-genome analysis [16] [21]. The pan-genome represents all gene families found in a species, including the core genome (shared by all isolates) and accessory genes that provide additional functions and selective advantages such as ecological adaptation, virulence mechanisms, and antibiotic resistance [21].

The integration of Keio collection data with pan-genome analysis allows for:

- Identification of conserved resistance mechanisms across bacterial lineages by determining whether resistance genes identified in E. coli have orthologs in other species.

- Assessment of gene essentiality conservation by comparing essential genes in E. coli with their conservation and essentiality status in related pathogens.

- Contextualization of resistance genes within the broader genomic landscape, including their association with mobile genetic elements or specific genomic neighborhoods.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Chemical-Genomic Studies

| Resource/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli Keio Knockout Collection | Genome-wide screening of gene deletion effects on chemical susceptibility | 7,970 strains covering 3,985 non-essential genes; kanamycin-resistant; FRT sites for marker excision [18] [19] |

| CRISPRi Knockdown Libraries | Essential gene function analysis in non-model bacteria | Enables partial knockdown of essential genes; used in A. baumannii and other pathogens [6] |

| CompareM2 Bioinformatics Pipeline | Comparative genomic analysis of bacterial isolates | Containerized, easy-to-install platform; integrates multiple annotation and analysis tools; generates dynamic reports [16] |

| FLP Recombinase Plasmid | Excision of antibiotic resistance markers from Keio mutants | Enables creation of markerless deletions for studying multiple genes in same background [18] [19] |

| Specialized Annotation Databases | Functional characterization of resistance genes | AMRFinder (antibiotic resistance), dbCAN (CAZymes), InterProScan (protein domains) [16] |

| High-Throughput Sequencing | Monitoring mutant abundance in pooled screens | Illumina platforms for barcode sequencing; requires sufficient depth for library coverage [20] |

From Data to Discovery: A Step-by-Step Pipeline Workflow

Within the framework of a comparative chemical genomics pipeline for antimicrobial resistance research, the systematic design of biological tools and screening parameters is paramount. This application note details core methodologies for constructing and utilizing bacterial strain libraries, executing high-throughput compound screens, and optimizing treatment concentrations. The integration of these components enables the rapid identification and characterization of novel compounds capable of overcoming resistant pathogens, thereby accelerating the drug discovery process.

Strain Library Construction and Amplification

CRISPR-Based Tunable Strain Engineering

For targeted genetic perturbation, the tunable CRISPR interference (tCRISPRi) system offers a robust, plasmid-free method for chromosomal gene knockdown in Escherichia coli [22]. This system is particularly valuable for constructing libraries that target both essential and non-essential genes, complementing existing knockout collections.

Key Advantages of tCRISPRi [22]:

- Chromosomal Integration: The entire system is integrated into the host chromosome, eliminating issues related to plasmid instability and variable copy number.

- Tunable Repression: Utilizes an arabinose-inducible promoter, allowing for graded control of gene repression with a wide dynamic range.

- Low Leakiness: Exhibits less than 10% leaky repression in the uninduced state.

- Simplified Workflow: Construction of a strain targeting a new gene requires only a single-step oligonucleotide recombineering.

Protocol: Amplification of Pooled Plasmid Libraries

A critical step in functional genomics screens is the amplification of pooled plasmid libraries (e.g., CRISPR guide RNA libraries) in E. coli to generate sufficient material for downstream applications. The following protocol, adapted from Addgene, is designed to minimize bottlenecks and skewing of library representation [23].

Workflow Timeline: The entire process spans two days, with transformation on Day 1 and bacterial harvest/DNA purification on Day 2 [23].

Materials:

- Electrocompetent Cells: 200 µL of ultra-high efficiency cells (e.g., Endura Duos, Stbl4). The use of electrocompetent cells with efficiency ≥1x10¹⁰ cfu/µg is strongly recommended [23].

- Pooled Library DNA: 800 ng of library DNA (100 ng per 25 µL of cells) [23].

- Electroporation Cuvettes: 8x pre-chilled 0.1 cm cuvettes [23].

- Media: 20 mL of SOC recovery media and LB Agar with appropriate antibiotic [23].

- Plates: 8x large (245 mm) LB Agar + Antibiotic bioassay plates and 3x small (65 mm) Petri dishes for dilution plating [23].

- DNA Purification: Reagents for 4x maxipreps (e.g., Qiagen HiSpeed Maxi) [23].

Procedure:

Day 1:

- Transformation: Thaw electrocompetent cells on ice. Add 200 ng of library DNA to each 50 µL aliquot of cells, mixing gently. Aliquot 25 µL of the mixture into a pre-chilled 0.1 cm electroporation cuvette and electroporate (e.g., 1.8 kV using a Bio-Rad Micropulser) [23].

- Recovery: Immediately add 1 mL of SOC media to the cuvette and transfer the solution to a vented Falcon tube containing 3 mL of pre-warmed SOC. Repeat for all aliquots [23].

- Outgrowth: Shake the tubes at 225 rpm for 1 hour at 30-37°C. Pool the cultures after the recovery period [23].

- Plating and Titering: Perform serial 1:100 dilutions of the pooled culture. Plate 100 µL of each dilution onto small, pre-warmed antibiotic plates to determine transformation efficiency. Distribute 2.5 mL of the undiluted culture onto each of the eight large bioassay plates, spreading gently until the liquid is absorbed [23].

- Incubation: Incubate all plates upside down at 30°C for 12-18 hours [23].

Day 2 (Morning):

- Calculate Library Coverage: Count the colonies on the most dilute plate. The total colony yield should be at least 1000-fold greater than the number of unique elements in the library to ensure adequate representation [23].

- Harvest Bacteria: Scrape the bacterial growth from the large bioassay plates using a cell spreader and cold LB media. Pool the scrapings into pre-chilled conical tubes on ice [23].

- Purify DNA: Perform a maxiprep on the harvested bacterial biomass to obtain the amplified plasmid library DNA [23].

Required Quality Control:

- Diagnostic Digest: Use a restriction enzyme that cuts the plasmid backbone once to verify library integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis [23].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Perform high-throughput sequencing to confirm guide RNA representation and identify any skewing that occurred during amplification [23].

Research Reagent Solutions for Strain Libraries

Table 1: Essential reagents for strain library construction and handling.

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| tCRISPRi System | Chromosomal, tunable gene knockdown | Integrated E. coli strain with inducible dCas9 and customized sgRNA [22] |

| Ultra-high Efficiency Electrocompetent Cells | High-efficiency plasmid library transformation | Endura Duos Electrocompetent Cells [23] |

| Pooled Plasmid Library | Delivers multiplexed genetic perturbations (e.g., gRNAs) | CRISPR knockout or activation library [23] |

| Large Bioassay Plates | Amplify library with sufficient colony coverage | 245 mm LB Agar + Antibiotic plates [23] |

High-Throughput Compound Screening

Assay Design and Execution

High-throughput screening (HTS) is a foundational method in drug discovery, enabling the rapid testing of millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological compounds against biological targets [24]. In resistance research, HTS identifies "hits"—compounds that modulate a pathway relevant to antibiotic resistance.

Core Components of an HTS Workflow [24]:

- Assay Plates: Microtiter plates (96, 384, 1536-well) form the base of HTS, where each well constitutes a single experiment.

- Compound Management: Assay plates are created by replicating from stock compound plates using nanoliter-volume liquid handling.

- Automation and Detection: Integrated robotic systems transport assay plates through stations for reagent addition, mixing, incubation, and finally, readout using sensitive detectors (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence).

Experimental Design and Quality Control: A successful HTS campaign requires careful experimental design [24].

- Plate Design: Layout should include effective positive controls (e.g., a known inhibitor) and negative controls (e.g., DMSO-only) to identify and correct for systematic errors.

- QC Metrics: The Z'-factor and Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD) are critical metrics to assess the quality of an HTS assay by measuring the separation between positive and negative controls [24].

Quantitative Data Analysis and Hit Selection

The massive datasets generated by HTS require robust statistical methods for analysis.

Table 2: Key metrics for HTS quality control and hit selection [24].

| Metric | Application | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Z'-factor | Assay Quality Control | Measures the separation band between positive and negative controls. Z' > 0.5 indicates an excellent assay. |

| SSMD | Assay Quality Control & Hit Selection | Measures the size of the effect. A higher SSMD indicates a stronger, more reliable effect. |

| z-score/z*-score | Hit Selection (Primary, no replicates) | Measures how many standard deviations a compound's result is from the plate mean. Robust z*-score is less sensitive to outliers. |

| t-statistic | Hit Selection (Confirmatory, with replicates) | Tests for a significant difference from the control. Used when replicate values are available for each compound. |

For primary screens without replicates, hit selection often relies on the robust z*-score method or SSMD to identify active compounds. In confirmatory screens with replicates, the t-statistic or SSMD that incorporates per-compound variability is more appropriate [24]. The goal is to select compounds with a desired, statistically significant effect size.

Concentration Optimization and Response Surfaces

Principles of Concentration Optimization

Determining the optimal concentration of a hit compound is crucial. The concentration affects both efficacy and toxicity, and the goal is often to find the concentration that maximizes the desired response (e.g., bacterial killing) while minimizing unwanted effects [25].

The relationship between factor levels (e.g., compound concentration) and the system's response (e.g., cell viability) can be visualized as a response surface [25]. For a single factor, this is a 2D curve; for two factors (e.g., two different drugs), it becomes a 3D surface. The optimum is found at the point of this surface that provides the maximum or minimum response.

Quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS)

A powerful advancement in concentration optimization is quantitative HTS (qHTS), where compound libraries are screened at multiple concentrations, generating full concentration-response curves for each compound [24] [26]. This approach provides rich data for hit confirmation and optimization:

- EC₅₀: The half-maximal effective concentration, a measure of compound potency.

- Maximal Response: The highest level of effect achieved by the compound.

- Hill Coefficient (nH): Describes the steepness of the dose-response curve.

qHTS enables the assessment of nascent structure-activity relationships (SAR) early in the screening process, providing immediate pharmacological profiling for the entire library [24].

Integrated Workflow and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated pipeline for resistance research, from library preparation to hit validation.

In the field of comparative chemical genomics, particularly for resistance research, the ability to accurately quantify the phenotypic response of cells or organisms to genetic and chemical perturbations is paramount. High-Throughput Phenotyping (HTP) has emerged as a critical technology to overcome the phenotyping bottleneck, enabling the non-invasive, efficient screening of large populations under various conditions [27]. A central consideration in designing these pipelines is the choice between kinetic and endpoint growth measurements. Kinetic analysis involves continuous monitoring of cell proliferation over time, providing rich data on growth rates and dynamic responses. In contrast, endpoint assays measure the total accumulated growth or product after a fixed period, offering a snapshot of final outcomes [28] [29]. Within resistance research, this choice dictates the depth of mechanistic insight attainable, influencing whether researchers simply identify resistant strains or can also characterize the dynamics and potential stability of the resistance phenotype. This application note details the principles, protocols, and practical applications of both methodologies to guide their implementation in chemical genomics pipelines for resistance research.

Comparative Analysis: Kinetic vs. Endpoint Phenotyping

The decision between kinetic and endpoint methodologies hinges on the specific research questions and experimental constraints. The following table summarizes the core characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of kinetic and endpoint growth measurement methodologies.

| Feature | Kinetic Growth Measurements | Endpoint Growth Measurements |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Continuous monitoring of growth or product formation over time [28]. | Measurement of total growth or product after a fixed reaction period, often terminated with a stop solution [28]. |

| Primary Data Output | Time-series data revealing growth curves and dynamic changes [29]. | A single data point representing total growth efficiency or product yield at the end of the experiment [29]. |

| Information Gained | Maximum specific growth rate, lag time, and other kinetic parameters; reveals dynamic responses and transient states [28] [29]. | Final population density or total biomass; provides a cumulative measure of growth or survival [29]. |

| Throughput Considerations | Lower relative throughput due to data collection over multiple time points and complex handling [29]. | Higher relative throughput, ideal for screening large numbers of samples simultaneously [28]. |

| Ideal Application in Resistance Research | Profiling mechanisms of action, studying resistance stability, and detecting heteroresistance [30]. | Large-scale chemical library screens, binary survival/death assessments, and total growth yield comparisons [29]. |

| Key Instrumentation | Automated plate readers with environmental control, time-lapse imaging systems (e.g., IncuCyte, Cell-IQ) [30]. | Standard plate readers, scanners for agar plate imaging, and automated image analysis pipelines [27] [31]. |

| Data Complexity | High; requires robust modeling and analysis tools for kinetic parameter extraction [29]. | Low; straightforward data analysis, often involving simple normalization and comparison [28]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Kinetic Growth Phenotyping using Agar Culture Arrays

This protocol, adapted for resistance screening in yeast, allows for the kinetic analysis of cell proliferation in a high-throughput format, surpassing the limitations of liquid culture arrays [29].

- Primary Research Application: Quantitative analysis of gene-chemical interactions in resistance research using microbial mutant collections [29].

- Principle: Time-lapse imaging of cell arrays spotted onto agar media, followed by automated image analysis and kinetic modeling to derive growth parameters [29].

Materials & Reagents

- Strains: Library of yeast gene deletion strains (e.g., S. cerevisiae).

- Chemicals: Compound(s) of interest for resistance profiling, dissolved in appropriate solvent.

- Growth Media: Solid agar media in standard SBS microplates or large bioassay dishes.

- Equipment: Optical scanner or automated imaging system, computer with YeastXtract software or equivalent [29].

Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Spot 4 µL of each standardized liquid yeast culture onto the solid agar media containing the desired concentration of the chemical perturbagen [29].

- Image Acquisition:

- Place the agar plate in an automated imaging system or scanner.

- Acquire images of the entire cell array at regular intervals (e.g., every 30-60 minutes) over the desired incubation period (typically 24-48 hours) [29].

- Image Analysis:

- Use software (e.g., YeastXtract) to analyze the time-series images.

- The software aligns images, detects culture spots, performs local background subtraction, and extracts total pixel intensity for each spot at every time point [29].

- Kinetic Modeling:

- Fit the extracted intensity-over-time data to a growth model, such as the logistic function.

- The model yields robust, quantitative phenotypes like maximum specific growth rate and time to maximum rate, which can be compared across strains and conditions [29].

Protocol B: Endpoint Phenotyping for High-Throughput Resistance Screening

This protocol is designed for high-throughput scenarios where the primary question is the final growth outcome after chemical exposure.

- Primary Research Application: High-throughput binary or quantitative screening to identify resistant or susceptible strains from a large library [29].

- Principle: Strains are exposed to a chemical perturbagen for a fixed duration, after which a single measurement of growth is taken, typically via optical density or image-based biomass estimation [28] [29].

Materials & Reagents

- Strains: Library of yeast gene deletion strains.

- Chemicals: Compound library for screening.

- Growth Media: Liquid or solid agar media in 96- or 384-well format.

- Equipment: Microplate reader (for liquid cultures) or high-resolution scanner (for agar plates), automated liquid handler.

Procedure

- Treatment Inoculation: Using an automated liquid handler, inoculate liquid media in a multiwell plate with different strains and add chemical compounds from the library. For solid media, spot cultures onto agar containing the compounds [29].

- Incubation: Incubate the plates under optimal growth conditions for a predetermined, fixed period (e.g., 16-24 hours) to allow for sufficient phenotypic expression [29].

- Endpoint Measurement:

- Data Analysis:

- Liquid Culture Data: Normalize OD readings to a positive control (e.g., no compound) to calculate percentage growth.

- Image Data: Use image analysis software to quantify the area and/or intensity of each culture spot. Normalize to controls to determine relative growth efficiency [29].

- Apply a threshold to classify strains as "resistant" or "susceptible" based on their normalized growth.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process and experimental workflows for selecting and implementing kinetic versus endpoint phenotyping in a resistance research pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of high-throughput phenotyping requires specific reagents and tools to ensure accuracy, reproducibility, and scalability.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for high-throughput growth phenotyping.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Passive Lysis Buffer | Homogenization of tissue or cell samples for consistent analyte measurement in biochemical assays [32]. | A proprietary 5x stock solution is diluted to 1x for use; must be stored at -20°C and made fresh for each assay [32]. |

| ColorChecker Reference | Standardization of image-based datasets to correct for variances in lighting and camera performance [31]. | ColorChecker Passport Photo (X-Rite, Inc.); provides 24 industry-standard color chips for calculating a color transformation matrix [31]. |

| Lead Acetate | Specific detection of hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) gas production capacity in biological samples [32]. | Reacts with H₂S in the headspace to form a brown-black precipitate of lead sulfide; used at 100 mM in agar or on filter paper [32]. |

| Solid Agar Media | Support medium for arrayed microbial cultures in high-throughput, low-evaporation assays [29]. | Profile Field & Fairway calcined clay mixture or standard lab agar; enables easy handling and rapid imaging of thousands of cultures [31] [29]. |

| Automated Imaging System | Non-destructive, high-frequency image capture for kinetic analysis of growth on solid media [29] [30]. | Includes platforms like IncuCyte, Cell-IQ, or conventional optical scanners; must maintain environmental control for live-cell imaging [30]. |

| Fluorescent Probes & Dyes | Live-cell reporting on specific biochemical events (e.g., apoptosis, enzyme activity, calcium flux) [30]. | Examples: FLUO-4 (calcium), Hoechst 33342 (nuclei), activatable probes for proteases; enable multiplexed kinetic analysis in complex co-cultures [30]. |

High-throughput chemical genomic screening is an indispensable tool in modern chemical and systems biology, enabling phenotypic profiling of comprehensive mutant libraries under defined chemical and environmental conditions [33]. These screens generate complex datasets that provide valuable insights into unknown gene function on a genome-wide level, facilitating the mapping of biological pathways and identification of potential drug targets [34]. However, the raw data from these screens contain inherent systematic and random errors that may lead to false-positive or false-negative results without proper processing [35]. The ChemGAPP (Chemical Genomics Analysis and Phenotypic Profiling) package addresses this critical gap by providing a comprehensive analytic solution specifically designed for chemical genomic data [36] [34].

Within the context of antimicrobial resistance research, ChemGAPP offers a streamlined workflow that transforms raw phenotypic measurements into reliable, biologically significant fitness scores. The tool implements rigorous quality control measures to curate screening data, which is particularly valuable for enriching microbial sequence data with functional annotations [33]. By systematically removing technical artifacts such as pinning mistakes and edge effects, ChemGAPP enables researchers to accurately identify genes essential for survival under stress conditions, including antibiotic exposure, thus contributing directly to antimicrobial resistance studies and potential clinical applications [36] [33].

The ChemGAPP package encompasses three specialized modules, each designed to address distinct screening scenarios in chemical genomics research [36] [37]. This modular approach allows researchers to select the most appropriate analysis framework based on their experimental design and scale.

Table 1: The Three Core Modules of the ChemGAPP Package

| Module Name | Screen Type | Primary Function | Key Analyses | Output Visualizations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChemGAPP Big | Large-scale screens with replicates across plates | Quality control, normalization, and fitness scoring | Z-score test, Mann-Whitney test, condition variance analysis, S-score assignment | Normalized fitness scores, quality control reports |

| ChemGAPP Small | Small-scale screens with within-plate replicates | Phenotypic comparison of mutants to wildtype | One-way ANOVA, Tukey-HSD analysis, fitness ratio calculation | Heatmaps, bar plots, swarm plots |

| ChemGAPP GI | Genetic interaction studies | Epistasis analysis for double mutants | Expected vs. observed double mutant fitness calculation | Genetic interaction bar plots |

ChemGAPP Big is specifically engineered for large-scale chemical genomic screens such as those employing the entire Escherichia coli KEIO collection [36] [34]. This module addresses multiple issues that commonly arise during large screens, including pinning mistakes and edge effects, through sophisticated normalization of plate data and a series of statistical analyses for removing detrimental replicates or conditions [37]. Following quality control, the module assigns fitness scores (S-scores) to quantify gene essentiality under specific conditions [36].

For smaller-scale investigations where replicates are contained within the same plate, ChemGAPP Small provides analytical capabilities focused on comparing mutant strains to wildtype controls [36] [37]. This module produces three visualization types: heatmaps for comprehensive overviews, bar plots for grouped comparisons, and swarm plots for distribution analysis [37]. The statistical foundation includes one-way ANOVA and Tukey-HSD analyses to determine significance between mutant fitness ratio distributions and wildtype distributions [37].

ChemGAPP GI addresses the specialized need for analyzing genetic interaction studies, particularly epistasis relationships [34]. This module calculates both observed and expected double knockout fitness ratios in comparison to wildtype and single mutants, enabling researchers to identify synergistic or antagonistic genetic interactions [36] [37]. The package has been successfully benchmarked against genes with known epistasis types, successfully reproducing each interaction category [34].

Plate Normalization Methods in High-Throughput Screening

Normalization of plate data is a critical step in chemical genomic analysis that facilitates accurate data visualization and minimizes systematic biases [35]. Several normalization approaches are implemented within the ChemGAPP framework to address different sources of technical variation.

Interquartile Mean (IQM) Normalization

The Interquartile Mean (IQM) method, also referred to as the 50% trimmed mean, provides an effective and intuitive approach for plate normalization [35]. This technique involves ordering all data points on a plate by ascending values and calculating the mean of the middle 50% of these ordered values, which effectively reduces the influence of extreme outliers that might represent technical artifacts rather than biological effects [35]. The resulting curve shape characteristics provide intuitive visualization of the frequency and strength of inhibitors, activators, and noise on the plate, allowing researchers to quickly identify potentially problematic plates [35].

Positional Effect Normalization

Positional effects represent another significant source of technical variation in high-throughput screening, often manifesting as biases in specific columns, rows, or wells [35]. ChemGAPP addresses these through the interquartile mean of each well position across all plates (IQMW) as a second level of normalization [35]. This approach calculates a normalized value for each well position based on its behavior across the entire screen, effectively correcting for systematic spatial biases that might otherwise be misinterpreted as biological signals.

Edge Effect Normalization