Beyond the Virtual: A Practical Guide to Ensuring Compound Availability in Chemogenomic Library Design

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate the critical challenge of compound availability in chemogenomic library design.

Beyond the Virtual: A Practical Guide to Ensuring Compound Availability in Chemogenomic Library Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate the critical challenge of compound availability in chemogenomic library design. It explores the foundational principles of balancing target coverage with practical sourcing, details methodological strategies for computational prioritization and physical management, offers solutions for common bottlenecks in quality and logistics, and establishes validation protocols for assessing library utility in phenotypic screening and precision oncology applications. By integrating recent case studies and emerging trends, this guide aims to bridge the gap between in silico design and experimental success.

The Compound Availability Imperative: Foundations for Effective Chemogenomic Screening

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main practical limitation of using a theoretical compound library for screening? The primary limitation is compound availability. A virtual library may contain billions of designed compounds, but only a fraction are readily accessible for synthesis and testing. Relying solely on theoretical sets risks investing significant resources into designs that are impractical to procure or produce in a timely manner for laboratory experiments [1].

How can I improve the hit rate of my screening campaign from the start? Integrate compound availability filtering at the very beginning of your virtual screening workflow. Before detailed computational analysis, filter ultra-large virtual libraries down to compounds that are commercially available or can be synthesized within a reasonable number of steps. This ensures that your final selection of candidates for experimental testing is grounded in practicality [1].

Our team has identified promising hit compounds. What is a common next-step bottleneck? A major bottleneck is the logistical challenge of sample management and experimental follow-up. Moving from in-silico designs to validated experimental results often involves coordinating multiple vendors and continents, which introduces delays and coordination problems. This fragmentation makes it difficult to implement efficient "lab-in-the-loop" workflows where experimental results quickly inform the next cycle of compound design [2].

Are there strategies to make initial screening more efficient and cost-effective? Yes, pooling strategies in High-Throughput Screening (HTS) can improve efficiency. This involves testing mixtures of compounds in each assay well rather than individual compounds. While this requires sophisticated deconvolution methods to identify active hits, it can significantly reduce the number of tests needed, saving both resources and time [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low experimental hit rate after a virtual screen.

- Potential Cause: The virtual screen was performed on a theoretical chemical space without considering the real-world availability or synthesizability of the top-ranked compounds. Consequently, the final selection was based on a compromised list that did not represent the best, accessible candidates.

- Solution:

- Implement a Modern VS Workflow: Adopt a workflow that starts with an ultra-large, but purchasable, compound library, such as the Enamine REAL library [1].

- Use Advanced Filtering: Employ machine learning-enhanced docking and absolute binding free energy calculations (e.g., ABFEP+) to prioritize the most promising and accessible compounds [1].

- Validate Availability Early: Before finalizing a list for experimental testing, confirm compound availability or custom synthesis routes with commercial providers.

Problem: Delays in the iterative "Design-Make-Test-Analyze" (DMTA) cycle.

- Potential Cause: Fragmented logistics and disjointed data management between compound design, synthesis, assay profiling, and data analysis steps.

- Solution:

- Utilize Integrated Platforms: Leverage services that combine predictive AI models, streamlined compound management, and high-throughput experimental profiling into a single, digitally-enabled workstream [2].

- Adopt Automated Analytics: Implement agentic AI systems (e.g., Cycle Time Reduction Agents) to automatically analyze lab operational metrics, identify bottlenecks like prolonged screening processes, and provide data-driven recommendations for optimization [4].

Experimental Protocols for Practical Screening

Protocol 1: Integrating Compound Availability into a Virtual Screening Workflow

This protocol outlines a modern computational approach to ensure that virtual screening campaigns are grounded in practical compound sourcing [1].

- Library Selection: Begin with an ultra-large, purchasable virtual library (e.g., several billion compounds from Enamine REAL).

- Prefiltering: Apply physicochemical property filters to remove compounds with undesirable characteristics.

- Machine Learning-Guided Docking: Use an active learning-based docking tool (e.g., AL-Glide) to efficiently screen the vast library. This step uses a machine learning model as a proxy for docking to evaluate billions of compounds, followed by full docking calculations on the top millions.

- Pose and Affinity Refinement: Rescore the best compounds (e.g., ~10,000-100,000) using more sophisticated docking programs that account for explicit water molecules (e.g., Glide WS).

- Absolute Binding Free Energy Calculation: Perform rigorous ABFEP+ calculations on the top-ranked compounds (e.g., thousands) to accurately predict binding affinities.

- Final Selection and Procurement: Select the top candidates for experimental testing based on predicted affinity and confirm immediate commercial availability.

Protocol 2: Implementing an Integrated "Lab-in-the-Loop" Workflow

This protocol describes a practical framework for tightly coupling computational design with experimental validation to accelerate compound optimization [2].

- AI-Driven Design: Use a platform (e.g., Inductive Bio's Compass) to explore and rank compound design ideas using predictive ADMET models.

- Streamlined Logistics and Synthesis: Send the selected designs to an integrated compound management platform (e.g., Tangible Scientific) for secure storage, handling, or synthesis.

- High-Throughput Experimental Profiling: Submit the compounds for rapid, automated ADME/Tox profiling (e.g., Ginkgo Datapoints' services for microsomal stability, solubility, permeability).

- Data Integration and Model Retraining: The structured, metadata-rich experimental results are fed back into the predictive AI models in near real-time, creating a closed feedback loop that continuously improves the accuracy of subsequent design cycles.

Quantitative Data on Screening Efficiency

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional vs. Modern Virtual Screening Approaches

| Screening Aspect | Traditional Virtual Screening | Modern Virtual Screening Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Library Size | Hundreds of thousands to a few million compounds [1] | Several billion purchasable compounds [1] |

| Typical Hit Rate | 1-2% [1] | Double-digit percentages (e.g., >10%) [1] |

| Key Scoring Method | Empirical scoring functions (e.g., GlideScore) [1] | Machine learning-guided docking and Absolute Binding FEP+ (ABFEP+) [1] |

| Compound Availability | Often considered late in the process or not at all [1] | Integrated from the start via purchasable library design [1] |

Table 2: Examples of Curated Physical Compound Libraries for Practical Screening

| Library Name | Size | Key Features and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| BioAscent Chemogenomic Library [5] | ~1,600 compounds | Diverse, selective, and well-annotated pharmacologically active probes; ideal for phenotypic screening and mechanism of action studies. |

| BioAscent Diversity Library [5] | ~100,000 compounds | Rigorously analyzed for full-scale HTS or pilot screening; proven hit-finding against challenging targets. |

| BioAscent Fragment Library [5] | ~1,300 fragments | Includes bespoke, structurally unique fragments; used for identifying initial hit compounds. |

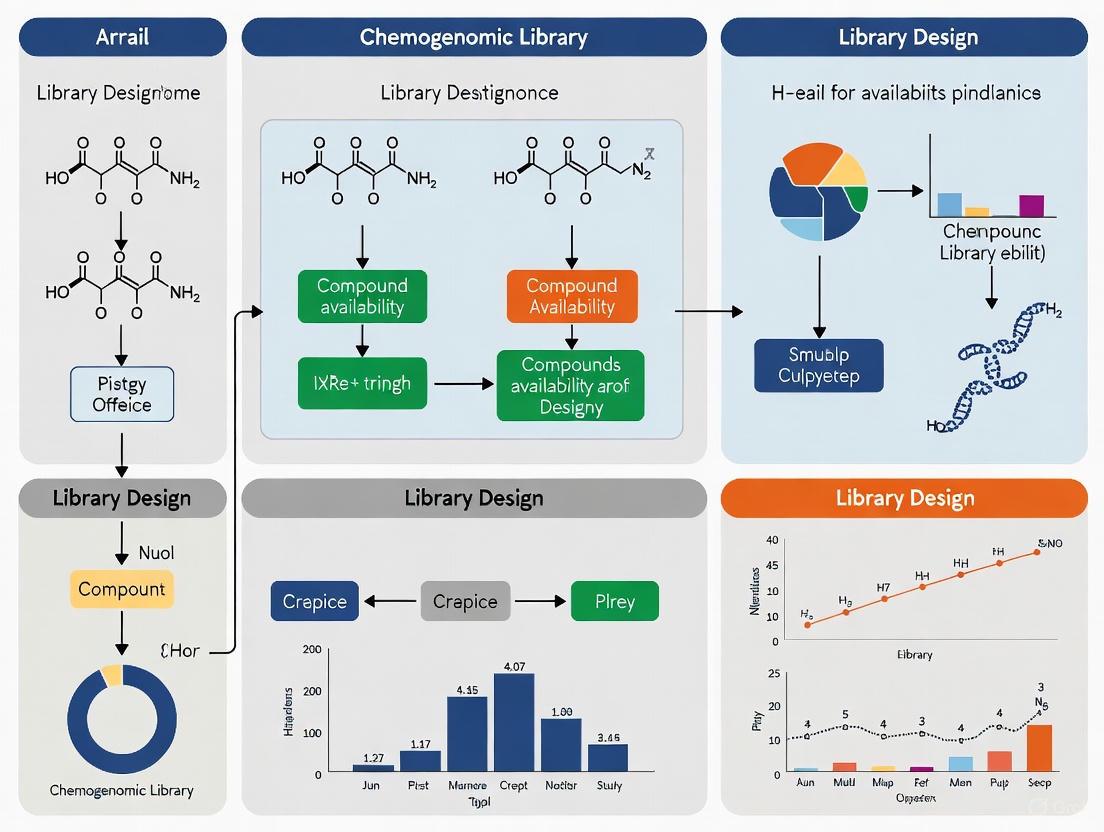

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the critical logistical and data integration challenges that arise when theoretical compound sets are used in practical screening, leading to a broken and inefficient cycle.

In contrast, an integrated "lab-in-the-loop" workflow directly addresses these bottlenecks by unifying data and logistics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Enhancing Practical Screening Efforts

| Item / Solution | Function |

|---|---|

| Purchasable Ultra-Large Libraries (e.g., Enamine REAL) [1] | Provides a foundation for virtual screening that is grounded in chemical reality, ensuring selected compounds can be acquired for testing. |

| Predictive Chemistry AI Platforms (e.g., Inductive Bio's Compass) [2] | Accelerates compound optimization by using ML models trained on broad datasets to predict key ADMET properties before synthesis. |

| Integrated Compound Management (e.g., Tangible Scientific's platform) [2] | Orchestrates the secure storage, handling, and rapid movement of compounds between partners, reducing logistical friction. |

| Rapid ADME/Tox Profiling Services (e.g., Ginkgo Datapoints) [2] | Delivers high-quality, automated experimental readouts (e.g., microsomal stability, solubility) to quickly validate computational predictions. |

| Curated Chemogenomic & Fragment Libraries (e.g., BioAscent libraries) [5] | Offers physically available, well-annotated sets of compounds for specific screening applications like phenotypic profiling or target discovery. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Chemogenomic Library Design

FAQ 1: What is the primary goal when designing a focused chemogenomic library? The primary goal is to achieve multi-objective optimization (MOP), aiming to maximize the coverage of biologically relevant targets, ensure compounds have cellular potency and selectivity, and minimize the final physical library size to suit practical screening capabilities [6]. This involves balancing often competing factors to create a library that is both comprehensive and feasible to use.

FAQ 2: Why is compound sourcing a critical factor in library design? Compound sourcing transitions a theoretical library into a practical one. Even with perfect in-silico design, a library is useless if the compounds cannot be acquired. One study noted that filtering for commercial availability reduced a theoretical library of 2,331 compounds by 52%, yet target coverage remained high at 86% [6]. Sourcing impacts cost, timelines, and the final scope of a screening campaign.

FAQ 3: How can I increase the likelihood that hits from my screen will be biologically active? Incorporate cellular activity filtering early in the design process. This means prioritizing compounds with documented cellular potency (e.g., low IC50 or EC50 values in cellular assays) over those that may only show activity in purified biochemical assays. This ensures the compounds in your library can engage with their target in a complex cellular environment [6].

FAQ 4: What is the benefit of including compounds with known clinical or preclinical status? Including a mix of Approved and Investigational Compounds (AICs) and Experimental Probe Compounds (EPCs) enriches the library's utility. AICs offer known safety profiles and potential for drug repurposing, while EPCs often represent novel chemical matter and can be tools for pioneering target discovery [6].

Troubleshooting Common Library Design and Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: Inadequate Target Coverage Despite a Large Library Size

- Symptoms: Your screening results point to interesting phenotypes, but you cannot identify the molecular target or pathway responsible.

- Root Cause: The library, while large, may lack diversity or be biased towards certain well-studied target families, leaving gaps in the "druggable genome."

- Solution:

- Systematically Define Your Target Space: Start by compiling a comprehensive list of proteins associated with your disease biology from resources like The Human Protein Atlas and PharmacoDB [6].

- Implement Target-Based Design: Search public databases (e.g., ChEMBL) for compound-target interactions that cover your defined target space [6] [7].

- Expand with Chemistry: For high-priority targets with few known ligands, perform a similarity search around existing active compounds to identify structurally related probes that may be commercially available [6].

Problem 2: Poor Screening Results Due to Inactive or Low-Potency Compounds

- Symptoms: High number of false negatives in screening; compounds show no effect even at high concentrations.

- Root Cause: The library contains compounds that are not bioavailable, are unstable, or lack sufficient potency in a cellular context.

- Solution:

- Apply Cellular Potency Filters: During library curation, set and apply minimum thresholds for cellular activity (e.g., IC50 < 1 µM) to filter out weak or inactive molecules [6].

- Prioritize Selective Compounds: When multiple options exist for a target, choose the compound with the best-documented selectivity profile to minimize off-target effects that can confound phenotypic data [8].

- Validate with Orthogonal Assays: Use secondary assays to confirm the on-target engagement and cellular activity of key library compounds before large-scale screening [8].

Problem 3: Physical Library Assembly Halted by Sourcing Issues

- Symptoms: The final, curated list of ideal compounds cannot be procured from vendors due to discontinuation, limited stock, or prohibitive cost.

- Root Cause: A purely in-silico design process did not incorporate real-time availability checks.

- Solution:

- Integrate Vendor Catalogs: Use automated scripts to cross-reference your candidate compound list with multiple vendor catalogs (e.g., Enamine, Sigma-Aldrich, Tocris) early and throughout the design process.

- Implement a Tiered Sourcing Strategy:

- Tier 1 (Ideal): Commercially available, in-stock compounds.

- Tier 2 (Backup): Structurally similar analogues with similar potency and selectivity that are in stock.

- Tier 3 (Custom): Compounds available for custom synthesis, considering the higher cost and longer lead time [6].

- Plan for Redundancy: For the most critical targets, include multiple, structurally distinct compounds to ensure at least one active probe is available for screening.

Experimental Protocols & Data Summaries

Protocol 1: Design and Construction of a Focused Anticancer Chemogenomic Library

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to create the Comprehensive anti-Cancer small-Compound Library (C3L) [6].

1. Define the Biological Target Space: * Inputs: Data from The Human Protein Atlas (cancer-associated proteins) and PharmacoDB (pan-cancer studies). * Output: A list of ~1,655 protein targets implicated in cancer, spanning multiple hallmark pathways [6].

2. Identify and Curate Compound-Target Interactions: * Inputs: Public databases (e.g., ChEMBL) and commercial compound collections. * Method: Manually extract and curate known compound-target pairs to create a "Theoretical Set." This initial set can be very large (>300,000 compounds) [6].

3. Apply Multi-Step Filtering: * Step 1 - Activity Filter: Remove compounds lacking documented cellular activity. * Step 2 - Potency Filter: For each target, select the most potent compound(s) to reduce redundancy. * Step 3 - Availability Filter: Filter the list against vendor catalogs to identify purchasable compounds. * Result: A final "Screening Set" of 1,211 compounds covering 1,386 (84%) of the original anticancer targets [6].

Protocol 2: A Multivariate Phenotypic Screening Workflow for Lead Identification

This protocol is based on a study that identified macrofilaricidal compounds [9].

1. Primary Bivariate Screen: * System: Use an abundantly available, relevant biological system (e.g., microfilariae). * Assay: A bivariate assay measuring two phenotypic endpoints (e.g., motility at 12 hours and viability at 36 hours). * Library: A diverse, target-annotated chemogenomic library (e.g., Tocriscreen 2.0 library of 1,280 compounds). * Analysis: Identify hits based on Z-score (>1) in either phenotype [9].

2. Secondary Multivariate Screen: * System: Use a more disease-relevant but less abundant system (e.g., adult parasites). * Assay: A multiplexed assay characterizing multiple fitness traits (e.g., neuromuscular control, fecundity, metabolism, and viability). * Compounds: All hits from the primary screen. * Analysis: Determine dose-response curves (EC50) for each phenotype. Prioritize compounds with high potency against the adult stage [9].

3. Target Deconvolution & Validation: * Leverage Annotation: Use the known human targets of hit compounds to investigate homologous parasite proteins. * Functional Studies: Use genetic tools (e.g., CRISPR) or omics approaches to validate the predicted target in the parasite [9].

Quantitative Data on Library Design Trade-Offs

Table 1: Impact of Sequential Filtering on a Virtual Anticancer Compound Library [6]

| Library Design Stage | Number of Compounds | Number of Targets Covered | Key Filtering Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Set | 336,758 | ~1,655 | Compound-target pairs from databases |

| After Activity & Potency Filtering | 2,331 | ~1,655 | Cellular activity; most potent per target |

| Final Screening Set (After Availability Filter) | 1,211 | 1,386 (84%) | Commercial availability |

Table 2: Performance of a Phenotypic Screening Strategy Using a Chemogenomic Library [9]

| Screening Metric | Result | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Screen Hit Rate | 2.7% (35 compounds) | Z-score >1 in microfilariae motility/viability |

| Sub-micromolar Potency | 13 compounds | EC50 <1 µM against microfilariae |

| Differential Stage Activity | 5 compounds | High potency against adults, low/slow on microfilariae |

Table 3: Key Resources for Chemogenomic Library Design and Screening

| Resource | Function in Library Design | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. Used to find compound-target interactions and activity data [7]. | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/ |

| Cell Painting Assay | A high-content, image-based assay that profiles compound-induced morphological changes. Used for phenotypic screening and target deconvolution [7]. | Protocol in [7] |

| Scaffold Analysis Software | Tools to classify compounds by their core chemical structure (scaffolds). Used to ensure chemical diversity and avoid redundancy [7]. | ScaffoldHunter [7] |

| Vendor Compound Libraries | Pre-designed libraries focused on specific target classes (kinases, GPCRs) or biological activity. A starting point for building a custom collection. | Tocriscreen [9], Sigma LOPAC |

| Graph Database (Neo4j) | A platform to integrate heterogeneous data (compounds, targets, pathways, phenotypes) into a unified network for analysis and visualization [7]. | https://neo4j.com/ |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Chemogenomic library design and application workflow.

Diagram 2: Core trade-offs in chemogenomic library design.

In precision oncology, the transition from vast, indiscriminate compound screening to focused, intelligent library design marks a critical evolution in drug discovery. This case study examines the strategic refinement of a chemogenomic library from a theoretical 300,000 compounds to a targeted physical collection of 1,211 compounds, specifically designed for phenotypic profiling of glioblastoma patient cells [10]. The process highlights a fundamental challenge in modern chemogenomics: balancing comprehensive target coverage with practical experimental constraints such as compound availability, cellular activity, and selectivity.

This refinement is not merely a numerical reduction but a sophisticated filtering process grounded in the similarity principle of chemogenomics—that similar ligands bind similar targets [11]. However, this principle relies on the quality and accuracy of the underlying data, which often presents significant challenges. Researchers must navigate quality issues in public domain chemogenomics data, which can stem from experimental variability, data interpretation errors, or data extraction and annotation problems [11]. Within this context, compound availability emerges as a critical determinant of library design, bridging the gap between theoretical computational models and practical experimental execution.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Chemogenomic Library Experiments

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key criteria for selecting compounds in a targeted chemogenomic library? A high-quality, targeted chemogenomic library should be designed based on multiple analytic procedures including cellular activity, chemical diversity, availability, and target selectivity [10]. The library must cover a wide range of protein targets and biological pathways implicated in the disease area of interest, with compounds serving as well-annotated, selective pharmacological probes [10] [5].

FAQ 2: What are common data quality issues in public domain chemogenomics data? Common issues include:

- Experimental uncertainty from different assay types and conditions

- Data extraction and annotation errors when compiling from multiple sources

- Inconsistent potency measurements across different laboratories

- Insufficient metadata for proper assay interpretation [11]

FAQ 3: How can I verify the quality and selectivity of compounds in a purchased library? When acquiring libraries from commercial providers, ensure they provide:

- Comprehensive pharmacological annotations for each compound

- Evidence of selectivity profiling across target families

- Batch-specific quality control data

- Storage conditions and compound integrity verification [5]

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions in Chemogenomic Screening

| Problem Symptom | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| High hit rate with promiscuous activity | Poor compound selectivity; assay interference compounds; library quality issues | Check library composition for pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS); review selectivity data of hit compounds; confirm activity with orthogonal assays | Implement stricter compound filtering during library design; include counter-screens; use structure-activity relationship analysis to identify true hits |

| Low reproducibility between screens | Compound degradation; inconsistent assay conditions; data normalization problems | Verify compound storage conditions (-20°C, DMSO desiccant); review batch-to-batch variability; confirm consistent cell passage numbers | Implement quality control steps; use standardized protocols; include reference compounds in each plate; maintain compound management standards [5] |

| Poor correlation between computational prediction and experimental results | Data quality issues in training set; inappropriate similarity metrics; target fishing failures | Audit source data quality; verify applicability domain of models; check for activity cliffs | Use consensus models; incorporate multiple data sources; apply strict quality filters to public domain data [11] |

| Patient-derived cells show highly variable responses | Biological heterogeneity; subtype-specific vulnerabilities; compound availability limitations | Analyze responses by molecular subtype; include positive controls for each subtype; verify target expression in cell models | Design patient-stratified libraries; include subtype-specific probes; implement phenotypic screening approaches [10] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Core Protocol: Design of a Targeted Chemogenomic Library

Purpose: To systematically refine a large virtual compound collection into a targeted, physically available library for phenotypic screening.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Initial Compound Collection Curation

- Compile compounds from public domain databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) and commercial sources

- Apply strict chemical structure standardization: normalize structures, remove duplicates, salt-disconnect

- Filter by drug-likeness criteria (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five, molecular weight <500 Da)

Bioactivity Filtering

- Retain compounds with demonstrated cellular activity (IC50/EC50 <10 μM)

- Prioritize compounds with dose-response data across multiple assays

- Exclude pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) using structural filters

Target and Pathway Coverage Optimization

- Map compounds to protein targets using curated bioactivity data

- Ensure coverage of key cancer pathways: kinase signaling, apoptosis, epigenetic regulation, GPCR signaling

- Balance target family representation: include kinase inhibitors, GPCR ligands, epigenetic modifiers, ion channel modulators [5]

Chemical Diversity Analysis

- Calculate molecular similarity using fingerprint-based methods (ECFP6)

- Apply maximum dissimilarity selection to ensure structural diversity

- Cluster compounds by scaffold and select representatives from each cluster

Availability and Practicality Assessment

- Verify physical availability from commercial suppliers

- Confirm compound solubility and stability in DMSO

- Assess synthesis feasibility for unavailable compounds

Selectivity and Annotation

Validation Protocol: Phenotypic Screening in Patient-Derived Cells

Purpose: To validate library performance in disease-relevant models using glioblastoma patient-derived cells.

Workflow Overview:

Methodological Details:

- Cell Models: Use glioma stem cells (GSCs) isolated from multiple glioblastoma patients representing different molecular subtypes (proneural, mesenchymal, classical) [10]

- Screening Format: 384-well plates, 1 μM compound concentration, 72-hour treatment

- Endpoint Measurement: High-content imaging assessing cell viability, morphology, and apoptosis

- Data Analysis: Calculate normalized cell survival relative to DMSO controls; identify patient-specific vulnerabilities through differential response patterns

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomic Library Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Specifications & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Chemogenomic Library | Targeted screening collection for phenotypic profiling | 1,211 compounds covering 1,320 anticancer targets; includes kinase inhibitors, GPCR ligands, epigenetic modifiers [10] |

| Patient-Derived Cell Models | Biologically relevant screening system | Glioma stem cells from glioblastoma patients; multiple molecular subtypes; maintain stem cell properties in culture [10] |

| High-Content Imaging System | Multiparametric phenotypic assessment | Automated microscopy with cell segmentation and analysis software; measures viability, morphology, and subcellular features |

| Compound Management System | Integrity and reproducibility assurance | -20°C storage with DMSO desiccation; liquid handling for library reformatting; track compound storage time and freeze-thaw cycles [5] |

| Bioactivity Databases | Compound annotation and target identification | Curated sources (ChEMBL, PubChem); include potency, selectivity, and mechanism of action data [11] |

| Quality Control Reference Compounds | Assay performance validation | Include known inhibitors for key targets; positive and negative controls for each assay plate |

Signaling Pathways in Glioblastoma Treatment Response

Pathway Interpretation: The targeted chemogenomic library impacts multiple signaling networks relevant to glioblastoma treatment response. Kinase inhibitors target receptor tyrosine kinase signaling (EGFR, PDGFR, MET), which drives proliferation and survival in glioma stem cells [10]. GPCR ligands modulate diverse cellular processes including migration, metabolism, and second messenger signaling. Epigenetic modifiers alter chromatin structure and gene expression patterns, potentially reversing therapy-resistant states. The integration of these targeted perturbations produces distinct phenotypic responses that reveal patient-specific vulnerabilities, demonstrating the utility of carefully designed compound libraries for identifying personalized treatment strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How do I balance the need for wide target coverage with the practical constraints of a limited library size? Researchers can design minimal screening libraries that strategically cover a wide range of anticancer protein targets. For instance, one published design achieved coverage of 1,386 anticancer proteins using a library of only 1,211 compounds. This approach relies on selecting compounds based on their cellular activity, chemical diversity, and target selectivity to ensure each molecule contributes meaningfully to the overall target space, thus minimizing redundancy [12].

2. Our phenotypic screening identified a hit compound, but we are struggling with target identification. What tools can help? Integrating a system pharmacology network that links drugs, targets, pathways, and diseases can significantly aid in target deconvolution. Furthermore, employing a curated chemogenomic library of around 5,000 small molecules, which represents a diverse panel of drug targets, can help. By profiling your hit compound against this library and comparing the resulting morphological or phenotypic profiles, you can identify compounds with similar effects and thus propose potential mechanisms of action [7].

3. We've encountered inconsistencies in bioactivity data from different public databases. How can we improve confidence in our data? This is a common challenge. A recommended strategy is to create a consensus dataset by combining information from multiple sources like ChEMBL, PubChem, and IUPHAR/BPS. An analysis showed that only about 40% of molecules appear in more than one source database. By cross-referencing data, you can automatically flag and curate potentially erroneous entries, significantly increasing confidence in the structural and bioactivity data used for library design [13].

4. What is a key metric for assessing the functional quality of a chemogenomic library beyond simple target count? A crucial metric is the library's performance in identifying patient-specific vulnerabilities in complex disease models. For example, a physical library of 789 compounds covering 1,320 anticancer targets was successfully used to reveal highly heterogeneous phenotypic responses in patient-derived glioblastoma cells. The ability of a library to detect such biologically and clinically relevant heterogeneity is a strong indicator of its functional quality and lack of redundant mechanisms [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key research reagents for chemogenomic library design and validation.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Consensus Bioactivity Dataset | A combined dataset from multiple public databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) used to validate compound bioactivity, improve target coverage, and identify erroneous entries through cross-referencing [13]. |

| System Pharmacology Network | A computational platform (e.g., built using Neo4j) that integrates drug-target-pathway-disease relationships. It assists in target identification and mechanism deconvolution for hits from phenotypic screens [7]. |

| Cell Painting Assay | A high-content, image-based morphological profiling assay. It generates a rich phenotypic profile for compounds, which can be used to group drugs by functional pathways and infer mechanisms of action [7]. |

| Minimal Screening Library | A carefully curated physical compound collection (e.g., ~1,200 compounds) designed to maximally cover a specific target space (e.g., the druggable genome) with minimal redundancy for efficient screening [12]. |

| Scaffold Analysis Software | Tools like ScaffoldHunter used to classify compounds by their core molecular frameworks. This helps ensure chemical diversity in the library and avoid over-representation of similar scaffolds [7]. |

Key Performance Metrics for Library Design

Table: Quantitative metrics for evaluating chemogenomic library performance.

| Metric | Definition / Calculation Method | Target Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Target Coverage Efficiency | Number of unique protein targets covered / Number of compounds in the library [12]. | A minimal library of 1,211 compounds achieved coverage of 1,386 targets, an efficiency of ~1.14 targets/compound [12]. |

| Phenotypic Hit Rate | Percentage of compounds in the library that produce a significant and reproducible phenotypic change in a relevant disease model [12]. | A pilot study on glioblastoma patient cells revealed a high degree of patient-specific vulnerabilities, indicating a functionally effective library [12]. |

| Data Source Redundancy | Percentage of compounds in your library whose bioactivity data is corroborated by two or more independent public databases [13]. | In a consensus dataset analysis, only 39.8% of molecules were found in more than one database, highlighting the value of multi-source curation [13]. |

| Scaffold Diversity Index | Number of unique Murcko scaffolds / Total number of compounds in the library [13]. | Focused, high-quality databases can have a high percentage of unique scaffolds (e.g., 22-36%), indicating good structural diversity [13]. |

Experimental Protocol: Building and Validating a Phenotypic Screening Library

This protocol outlines the key steps for assembling a chemogenomic library tailored for phenotypic screening and subsequent target deconvolution, based on established methodologies [7].

Objective: To create a library of approximately 5,000 small molecules that provides broad coverage of the druggable genome and is optimized for use in cell-based phenotypic assays.

Materials:

- Public bioactivity databases (ChEMBL, PubChem, IUPHAR/BPS, BindingDB, Probes & Drugs)

- Chemical structure management software (e.g., with SMILES standardization capabilities)

- Scaffold analysis tool (e.g., ScaffoldHunter)

- System pharmacology database (e.g., built in Neo4j) integrating targets, pathways, and diseases

- Cell Painting assay reagents and high-content imaging system

Methodology:

Step 1: Data Assembly and Curation

- Extract compound and bioactivity data from multiple public databases, focusing on human macromolecular targets [13].

- Standardize molecular structures using canonical SMILES to resolve representation differences.

- Create a consensus dataset by cross-referencing compounds and bioactivities across sources. Flag entries with significant discrepancies (e.g., conflicting potency values) for manual curation or exclusion [13].

Step 2: Library Design and Compound Selection

- Filter for drug-like properties: Apply criteria such as molecular weight (e.g., ≤1500 Da) and other desired physicochemical properties [13].

- Prioritize bioactive compounds: Select compounds with confirmed, potent activity (e.g., IC50/Ki < 1 µM) against their primary targets.

- Maximize target coverage: Use a greedy algorithm or similar strategy to select the minimal set of compounds that covers the maximum number of targets from the druggable genome [12].

- Ensure scaffold diversity: Perform Murcko scaffold analysis on the selected compound set. If certain scaffolds are over-represented, select a single, best-in-class compound from that scaffold family to minimize redundancy [7] [13].

Step 3: Functional Validation in Phenotypic Assays

- Screen the physical library in a Cell Painting assay [7]. This assay stains multiple cellular components (nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, etc.) to generate a rich, high-dimensional morphological profile for each compound.

- Extract hundreds of morphological features from the captured images using software like CellProfiler.

- Use dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., UMAP) to visualize the phenotypic landscape of the library. A well-designed library should induce a diverse set of morphological profiles, indicating coverage of distinct biological mechanisms.

Step 4: Data Integration for Target Identification

- Build a system pharmacology network linking compounds, protein targets, biological pathways, and disease ontologies [7].

- For a hit compound from a phenotypic screen, query this network. If the hit's morphological profile from Step 3 is similar to that of a library compound with a known target, this can strongly implicate a shared pathway or specific target [7].

Experimental Workflow: From Library to Mechanism

This diagram visualizes the key stages of the experimental protocol, showing how data flows from raw public sources to a final, testable biological hypothesis.

From Data to Physical Vials: Methodologies for Building Accessible Libraries

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What is computational triage and why is it critical in chemogenomic library design?

Computational triage is the process of classifying or prioritizing hits from screening campaigns using computational and cheminformatic techniques to identify compounds with the highest chance of succeeding as probes or leads [14]. In the context of chemogenomic library design, it is essential for directing finite resources towards the most promising chemical matter by quickly weeding out assay artifacts, false positives, promiscuous bioactive compounds, and intractable screening hits [14]. This process is a combination of science and art, leveraging expertise in medicinal chemistry, cheminformatics, and analytical chemistry to de-risk the early stages of drug discovery [15] [14].

FAQ 2: What are the key chemical property filters used during pre-sourcing filtering?

During pre-sourcing filtering, compounds are evaluated against a series of calculated property filters to prioritize those with desirable "drug-like" or "lead-like" properties. Key constitutive and predicted physicochemical properties are calculated and used as filters [15]. The following table summarizes common filters and their typical thresholds used to identify high-quality chemical matter.

Table: Key Calculated Property Filters for Pre-Sourcing Triage

| Filter Category | Specific Property/Filter | Typical Threshold or Purpose | Primary Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Constituent Properties | Molecular Weight (MW) | Often applied with other rules (e.g., Ro5) | Impacts pharmacokinetics (absorption, distribution) [15] |

| Heavy Atom Count | -- | -- | |

| Lipophilicity & Solubility | Calculated LogP (cLogP) | Often applied with other rules (e.g., Ro5) | Affects membrane permeability and solubility [15] |

| Calculated Solubility (LogS) | -- | -- | |

| Structural Alerts | Rapid Elimination of Swill (REOS) | Filter for undesirable functional groups | Identifies compounds with reactive or toxicophores [14] |

| Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) | Filter for promiscuous chemotypes | Flags compounds likely to act as assay artifacts [14] | |

| Other Properties | Polar Surface Area (PSA) | -- | Estimates cell permeability [15] |

| Number of sp3 Atoms (Fsp3) | -- | Indicator of molecular complexity [14] |

FAQ 3: How can I troubleshoot a high rate of false positives or assay artifacts in my screening hits?

A high rate of false positives often indicates insufficient pre-screening triage. The following troubleshooting guide addresses common causes and solutions.

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for High False Positive Rates

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution / Diagnostic Action |

|---|---|---|

| Promiscuous Inhibitors | The hit set is enriched with Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) and other problematic chemotypes. | Apply rigorous PAINS and REOS filters before sourcing compounds [14]. Use tools like the EPA's Cheminformatics Modules to profile chemicals against structure-based alerts [16]. |

| Intractable Chemical Matter | Hits contain chemically reactive or synthetically challenging structures, making follow-up SAR studies difficult. | Perform scaffold analysis and clustering. Prioritize series with synthetically accessible core structures and available commercial reagents for hit expansion [15] [17]. |

| Poor Physicochemical Properties | Hits exhibit poor "drug-like" qualities (e.g., high molecular weight, excessive lipophilicity). | Apply property calculations (e.g., LogP, MW) and use lead-like filters during the virtual library design and pre-sourcing phase [15] [14]. |

| Lack of Confirmatory Analogs | A "hit" is based on a single active compound, making it difficult to distinguish from random error or artifacts. | During library design, ensure multiple representatives of each scaffold are included. During triage, prioritize hits where several compounds sharing a common scaffold show activity [14]. |

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for ensuring compound availability and synthesizability during virtual library design?

Ensuring that virtually designed compounds are either commercially available or readily synthesizable is a cornerstone of effective pre-sourcing filtering.

- Utilize "Make-on-Demand" Vendors: Leverage virtual libraries from vendors who specialize in synthesizing compounds on demand, such as the "Readily Accessible" (REAL) Database [17].

- Employ Pre-Validated Reactions: Design virtual libraries using known reaction schemas and readily available chemical reagents. This approach, used by pharmaceutical companies (e.g., Pfizer's PGVL, Merck's MASSIV) and in open-source tools, ensures synthetic feasibility [17].

- Check Commercial and In-House Inventories: Use databases of commercially available compounds (e.g., eMolecules, ZINC) to verify the tangible nature of potential hits before physical sourcing [14].

- Consider Synthetic Complexity Early: During the hit-to-lead stage, assess the commercial availability of starting materials and the feasibility of synthetic routes for the core scaffold [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Workflow for Pre-Sourcing Computational Triage of a Virtual Chemogenomic Library

This protocol details a step-by-step methodology for computationally triaging a virtual library to create a high-priority, synthesizable set for physical sourcing or testing.

1. Objective: To filter a large virtual chemogenomic library through a series of computational steps to identify a prioritized subset of compounds that are chemically desirable, non-promiscuous, and synthetically feasible.

2. Materials and Reagents (The Scientist's Toolkit):

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Triage

| Tool / Resource | Type | Brief Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| KNIME / DataWarrior | Open-Source Software | Platforms for workflow automation, including chemical structure enumeration and application of filters [17]. |

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics | A software toolkit for Cheminformatics used within programming environments like Python for property calculation and substructure filtering [17]. |

| ZINC / eMolecules Database | Tangible Compound Database | Curated databases of commercially available compounds used to verify the "real" and "tangible" nature of virtual hits [14]. |

| EPA Cheminformatics Modules (CIM) | Web-Based Tool | Provides access to hazard and safety profiles, as well as structure-based alert profiling (e.g., for PAINS) [16]. |

| SMILES Strings | Chemical Data Format | A line notation for representing molecular structures, which is the standard input for many cheminformatics operations [17]. |

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

Step 1: Library Acquisition and Standardization

- Input your virtual library in a standard format (e.g., SMILES, SDF).

- Use a tool like RDKit or the Ketcher editor (as used in the EPA CIM) to standardize the structures, generate canonical SMILES, and remove duplicates [16].

Step 2: Calculation of Physicochemical Properties

- For all compounds in the standardized library, calculate key physicochemical properties. These typically include:

Step 3: Application of Property and Structural Filters

- Apply defined filters to remove undesirable compounds. This is typically a multi-step process:

- Lead-like/Drug-like Filter: Apply thresholds based on rules like Lipinski's Rule of Five or other lead-like criteria (e.g., MW < 450, cLogP < 3.5) [14].

- Structural Alert Filter: Screen the library against PAINS and REOS filters to remove compounds with known promiscuous or reactive motifs [14].

- Custom Project Filters: Apply any target-family-specific filters (e.g., excluding compounds that conflict with a known binding site).

Step 4: Assessment of Synthetic Feasibility and Commercial Availability

- Option A (Commercial Availability): Cross-reference the filtered compound list with databases of commercially available compounds (e.g., eMolecules). This is the most straightforward path for sourcing [14].

- Option B (Synthetic Feasibility): For novel virtual compounds, use tools like KNIME or RDKit with reaction libraries to assess whether they can be synthesized from available reagents using known reactions. Prioritize compounds that can be made via few steps with high yield [17].

Step 5: Clustering and Final Prioritization

- Cluster the remaining compounds based on chemical similarity or scaffold structure to ensure diversity in the final set [15] [18].

- Select a representative subset from each cluster for sourcing, ensuring broad coverage of the available chemical space related to the target.

4. Workflow Diagram:

Protocol 2: Implementing a Similarity Search for Hit Expansion

1. Objective: To find commercially available compounds that are structurally similar to a confirmed screening hit, enabling rapid Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) exploration and hit validation.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Start with the chemical structure of a validated hit compound (the "query").

- Step 2: Using a cheminformatics tool (e.g., ICM, EPA CIM, KNIME), perform a similarity search against a database of commercially available compounds (e.g., ZINC, eMolecules) [18] [16].

- Step 3: Set a similarity threshold (e.g., Tanimoto coefficient ≥ 0.6) to define the minimum structural similarity for results [16].

- Step 4: Execute the search and retrieve the list of similar compounds.

- Step 5: Apply the same pre-sourcing filters (property calculations, PAINS, etc.) from Protocol 1 to the resulting list to prioritize the most promising analogs for purchase and testing [15] [14].

3. Workflow Diagram:

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Commercial Catalog Integration Errors

Problem: Errors occur when uploading or integrating a commercial compound catalog file into a research data system.

| Error Type | Description | Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Parsing Error [19] | The system cannot parse or read the catalog file's structure. | - Verify the file format (e.g., CSV, TSV) matches specifications.- Check for and correct structural errors like missing column headers or invalid delimiters. |

| Missing Required Field [20] | A mandatory data field (e.g., compound ID, name) is empty. | - Review the error report to identify the missing field(s).- Populate all required fields in the source data file and re-upload. |

| Duplicate ID Error [20] | Two or more entries share the same unique catalog identifier. | - Ensure each compound or item has a unique ID.- Remove or assign new IDs to duplicate entries. |

| Invalid Field Value [20] | A field contains an invalid value (e.g., an incorrectly formatted URL). | - Correct the value format as per specifications (e.g., ensure URLs use http:// or https://).- Validate data types (e.g., text, numbers) for each field. |

| File Not Found [19] | The system cannot access or locate the catalog file at the provided source. | - Confirm the file path or URL is correct and accessible.- Check that the server hosting the file is online and credentials are valid. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Failed Experiments with Sourced Compounds

Problem: An experiment, such as a cell viability assay, fails or yields highly variable results after introducing a new compound from a commercial supplier.

This logical troubleshooting workflow helps systematically diagnose the cause of experimental failure.

Systematic Troubleshooting Steps [21]:

- Identify the Problem: Precisely define what went wrong without assuming the cause. Example: "No inhibition of cell growth was observed," not "The compound is inactive." [21].

- List All Possible Explanations: Consider all potential causes. For a failed assay, this list includes:

- The Compound: Incorrect concentration, degradation due to improper storage, or supplier error.

- Controls: Positive/negative controls failed, indicating an assay protocol issue.

- Protocol: A deviation from the established method or a flawed step.

- Materials/Cells: Contaminated or unhealthy cell cultures.

- Equipment: Miscalibrated or malfunctioning instruments [21].

- Collect the Data: Review all available information.

- Controls: Did the positive and negative controls perform as expected? [21].

- Storage & Conditions: Was the compound reconstituted and stored according to the supplier's datasheet? Check expiration dates [21].

- Procedure: Compare your lab notebook against the published protocol to identify any unintentional modifications [21].

- Eliminate Explanations: Rule out causes that the data disproves. If controls worked, the core assay protocol is likely sound. If the compound was stored correctly, degradation is less likely [21].

- Check with Experimentation: Design a new experiment to test remaining hypotheses. Examples:

- Re-test the compound in a dose-response curve.

- Confirm compound identity and purity using analytical methods.

- Repeat a key step (e.g., cell plating) with meticulous technique [21].

- Identify the Cause: Synthesize results from your experimental checks to pinpoint the root cause. Implement a fix, such as ordering a new batch of compound, and re-run the experiment [21].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is a chemogenomic library and how is it used in precision oncology? A: A chemogenomic library is a collection of well-annotated, bioactive small molecules designed to target a wide range of proteins in a cellular context. Unlike highly selective chemical probes, these compounds may modulate multiple targets, enabling coverage of a large portion of the "druggable" genome. In precision oncology, they are used in phenotypic screens on patient-derived cells (like glioblastoma stem cells) to identify patient-specific vulnerabilities and potential therapeutic targets based on the cells' response to the compound library [12] [22] [10].

Q: What criteria should I use to select a targeted compound library for an anticancer screen? A: The design of a targeted screening library should be adjusted for several factors, including:

- Library Size: Balancing comprehensiveness with practical screening capacity [12].

- Cellular Activity: Prioritizing compounds with known cellular bioactivity [12] [23].

- Target Coverage: Ensuring coverage of key biological pathways and protein families implicated in cancer (e.g., kinases, epigenetic regulators) [12] [22] [23].

- Chemical Diversity & Availability: Selecting structurally diverse compounds that are commercially available [12].

- Selectivity: Considering the selectivity of compounds, while acknowledging that less selective compounds can be useful for covering a broader target space [12] [22].

Q: A make-on-demand supplier failed to deliver a key compound for my library. What are my options? A: First, communicate with the supplier to understand the reason for the delay (e.g., synthetic complexity, quality control). Your contingency options include:

- Source from an Alternative Supplier: Check other commercial vendors for the same compound or a direct analog.

- Modify Your Library Design: Replace the unavailable compound with a tool compound that targets the same protein or pathway. This may require re-annotating your virtual library.

- In-house or CRO Synthesis: If the compound is critical and unavailable elsewhere, consider synthesizing it in-house or outsourcing its synthesis to a contract research organization (CRO).

Q: How can I validate that a compound from a commercial catalog is performing as intended in my assay? A: Implement a rigorous set of control experiments:

- Use a validated positive control to ensure your assay is functioning correctly.

- Use a pharmacological control: If available, test a well-characterized tool compound known to act on your target in the same assay system.

- Dose-Response: Test the compound across a range of concentrations to see if it produces a expected sigmoidal dose-response curve.

- Counter-screen: Test the compound in an unrelated assay to check for off-target or non-specific effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key resources and materials central to building and screening chemogenomic libraries.

| Tool / Resource | Function & Application in Library Research |

|---|---|

| Focused Anticancer Library | A pre-selected collection of compounds targeting pathways and proteins implicated in various cancers. Used for efficient screening to identify patient-specific vulnerabilities [12]. |

| Diversity-Oriented Library | A large collection of structurally diverse, "drug-like" compounds. Used in high-throughput screening (HTS) to find novel starting points for drug discovery programs against new targets [23]. |

| Chemogenomic Library | A collection of ~1,600+ selective, well-annotated pharmacologically active probes. A powerful tool for phenotypic screening and deconvoluting the mechanism of action of a treatment [23]. |

| Fragment Library | A set of low molecular weight compounds designed for fragment-based drug discovery. Used to identify weak but efficient binding motifs that can be developed into high-affinity leads [23]. |

| PAINS (Pan-Assay Interference Compounds) Set | A collection of compounds known to cause false-positive results in assays (e.g., by aggregation, redox cycling). Used to validate assay systems and identify problematic compounds early [23]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: My scanner cannot read the barcodes on compound tubes. What should I check first?

This is often related to label quality or scanner settings. Follow this systematic checklist to resolve the issue [24] [25] [26]:

Step 1: Inspect the Barcode Label

- Damage Check: Look for smudging, scratching, or fading. Reprint and replace any damaged labels [24].

- Contrast Verification: Ensure high contrast between bars and background; low-contrast labels are a common cause of failure [24] [26].

- Quiet Zone Check: Confirm that a clear, blank margin surrounds the barcode as required [24].

Step 2: Check the Scanning Environment

- Glare Reduction: Glossy tube surfaces or plastic wraps can cause glare. Tilt the scanner to a 15-degree angle to avoid direct reflection [24].

- Lighting Adjustment: Improve ambient lighting if too dim, or shade the scanner if excessive direct light causes washout [24] [26].

- Lens Cleanliness: Clean the scanner's lens from dust or debris [26].

Step 3: Verify Scanner Configuration

Step 4: Validate Barcode Data

- Use an online validator tool to check for data formatting errors or incorrect check digits [24].

FAQ: We are experiencing a high rate of data entry errors and misidentified compounds. How can we improve accuracy?

This typically indicates a need for better process controls and technology integration [26] [27].

Solution 1: Implement Automated Validation

- Use smart data capture software that can validate a scanned barcode against an expected product or batch list and instantly alert the user to a mismatch [26].

Solution 2: Establish Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

Solution 3: Introduce Quality Control Loops

FAQ: Our barcode labels are smudging or peeling off in freezer storage. What are our options?

This is a problem of label material compatibility with your storage environment [24].

- Immediate Fix: Use durable, freezer-grade labels with industrial-grade adhesives designed to withstand low temperatures and condensation [24] [28].

- Long-Term Prevention: For critical samples, consider using pre-printed barcodes produced under controlled conditions or labels with protective coatings to resist moisture and abrasion [24] [27].

FAQ: How can we prevent barcode duplication and cross-contamination in our library?

This is a critical issue for data integrity and requires a mix of procedural and technical solutions [26].

- Process: Implement barcode verification processes during the initial labeling and registration of new compounds to detect and prevent duplicates [26].

- Software: Utilize a compound management system that automatically flags duplicate barcode entries.

- Archiving: Archive superseded or retired codes in your database to prevent their accidental re-use [24].

Barcode Performance Data and Solutions

Table 1: Common Barcode Scanning Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Print Quality [24] | Low-resolution, fuzzy printing | Re-calibrate printer density/speed; use higher-resolution printers. |

| Smudging or improper adhesion | Use ribbon and media matches; select appropriate label stock. | |

| Environmental Factors [24] [26] | Glare from reflective surfaces | Tilt scanner 15°; use diffused lighting. |

| Condensation on cold-storage tubes | Use freezer-grade, moisture-resistant labels; wipe tubes before scanning. | |

| Scanner Technique [24] [25] | Wrong scan distance or angle | Train staff on proper techniques; use omnidirectional scanners. |

| Slow scan rates | Update scanner firmware; optimize software settings. | |

| Data Integrity [24] | Check digit errors | Use automated barcode generation tools; validate codes before printing. |

| Unrecognized barcode formats | Update scanner software to support all used symbologies. |

Table 2: Comparison of Barcode Types for Compound Management

| Barcode Type | Data Capacity | Key Advantages | Ideal Use Case in Compound Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Code 39 [27] [28] | Low | Simple, widely accepted. | Basic inventory tracking of larger containers. |

| Code 128 [27] [28] | High | High density, versatile. | Encoding detailed compound data on tubes and plates. |

| Data Matrix (2D) [27] [28] | Very High | Stores large data in small space; can be read even if damaged. | Tracking individual microtubes and vials where space is limited. |

Experimental Protocols for System Validation

Protocol: Quality Control and Verification of Barcode Readability

Objective: To establish a routine procedure for ensuring barcode labels remain scannable throughout their lifecycle in storage.

Materials:

- Barcode scanner(s) in use

- Sample set of barcoded tubes from different batches and storage conditions

- ISO/IEC barcode verification test equipment (optional for advanced QC)

- Lint-free cloth and lens cleaning solution

Methodology:

- Sample Selection: Weekly, randomly select 1-2% of newly printed barcodes and 0.5% of archived samples from various storage conditions (e.g., room temp, -20°C, -80°C) [24].

- Visual Inspection: Check for physical degradation: smudges, voids, fading, peeling, or corrosion [24].

- Scan Test: Use all scanner models in your facility to attempt to read each selected barcode. Record the first-pass scan success rate [24] [28].

- Lens Cleaning: As part of the weekly check, clean scanner lenses with a lint-free cloth and solution to prevent performance issues [25] [28].

- Data Logging: Log the scan success rate and any common failure modes. A success rate below 99% should trigger an investigation into print quality or environmental conditions [24].

Protocol: Implementing a Barcode-Driven Compound Retrieval Workflow

Objective: To provide a reliable, step-by-step methodology for researchers to retrieve compounds from the centralized library using barcodes, minimizing human error.

Materials:

- Centralized Compound Database

- Handheld barcode scanner integrated with the database

- Portable cooler or rack for sample transport

Methodology:

- Request Submission: The researcher identifies compounds of interest via the database interface and submits a retrieval request, generating a digital picklist.

- Retrieval Initiation: A technician loads the digital picklist onto a handheld scanner. The system directs the technician to the correct storage unit and location.

- Location Verification: The technician scans the barcode on the storage unit rack/shelf to confirm they are in the correct location.

- Compound Verification: The technician scans the barcode on the specific compound tube or plate. The software validates in real-time that the scanned compound matches the one on the picklist. A mismatch triggers an immediate audio/visual alert [26].

- Completion and Logging: Once all items are correctly scanned and collected, the system automatically updates the database, logging the retrieval time, user, and new location of the compounds (e.g., "checked out").

System Workflow and Troubleshooting Diagrams

Barcode Troubleshooting Flowchart

Compound Retrieval Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for a Barcoded Compound Management System

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| 2D Barcode Scanners | Reads barcodes and transmits data to the management system. | Imaging-based scanners are preferred for reading 2D codes (e.g., Data Matrix) on curved tube surfaces [26] [27]. |

| Thermal Transfer Printer | Prints durable, high-resolution barcode labels. | Produces labels resistant to smudging; allows for in-house label printing as needed [28]. |

| Freezer-Grade Label Stock | The physical label material attached to compound containers. | Designed to withstand extreme temperatures (-80°C), condensation, and exposure to solvents without peeling or fading [24] [28]. |

| Centralized Database (WMS) | The software core that tracks all compound data, location, and movement. | Must support FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) for scientific data management [29]. |

| Chemogenomic Library | A curated collection of bioactive small molecules with known targets. | Used for phenotypic screening and target identification. For example, a library of 1,600+ probes for mechanism of action studies [23]. |

| Automated Storage System | A robotic system that stores and retrieates compound plates or tubes. | Integrates with barcode scanners for fully automated, trackable compound handling, eliminating manual errors [29]. |

In modern drug discovery, chemogenomic libraries are indispensable for identifying novel therapeutic targets and understanding complex disease mechanisms. However, a significant challenge in this field is compound availability, where the design and physical availability of screening collections can limit the scope and pace of research. This technical support center addresses common experimental hurdles, framing solutions within the critical context of efficient library design and logistics to maximize research throughput and success.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are assay-ready plates and how do they improve screening efficiency? Assay-ready plates are microplates (e.g., 96-, 384-, or 1536-well formats) pre-plated with compounds, allowing them to be used directly in screening campaigns without additional preparation steps. They improve efficiency by standardizing compound delivery, minimizing reagent use, reducing plate-handling errors, and significantly accelerating the start of an assay. This logistics model is crucial for leveraging large chemogenomic libraries, as it provides direct, rapid access to a vast array of chemical matter for screening [30].

2. My screening results show high background. How can I address this? High background is a common issue that can often be traced to insufficient washing or non-specific binding.

- Solution: Ensure you are following an appropriate washing procedure. Increase the number of washes and consider adding a 30-second soak step between washes to ensure complete removal of unbound materials. Also, verify that your blocking buffer is effective and compatible with your detection system [31] [32] [33].

3. I am encountering high variation between duplicate wells. What could be the cause? Poor duplicates often stem from procedural inconsistencies.

- Solution:

- Pipetting: Check your pipette calibration and technique. Ensure all reagents and samples are thoroughly mixed before addition to the plate [31].

- Washing: Inconsistent or inadequate plate washing is a primary culprit. If using an automated washer, check that all ports are clean and unobstructed [32].

- Contamination: Avoid reusing plate sealers, as this can lead to cross-contamination between wells. Use a fresh sealer for each incubation step [31] [33].

4. How can I troubleshoot a situation where I get no signal? A lack of signal can be due to several factors related to reagents or procedure.

- Solution:

- Reagent Check: Confirm that all reagents were added in the correct order and that none are expired. A critical step is ensuring that key components like the detection antibody or substrate were not omitted [31] [33].

- Protocol Adherence: Verify that incubation times were followed and that all reagents were at room temperature before starting the assay [33].

- Component Compatibility: Check that your wash buffer does not contain sodium azide, as it can inhibit the Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) enzyme used in many detection systems [31].

5. My standard curve looks good, but my samples are reading too high. What should I do? This typically indicates that the analyte concentration in your samples is outside the dynamic range of the assay.

- Solution: Dilute your samples and re-run the assay. It is good practice to test samples at multiple dilutions to ensure readings fall within the linear range of the standard curve [32].

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide consolidates common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions to help you quickly resolve experimental issues.

Table 1: ELISA Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background | Insufficient washing [31] [33] | Increase wash number; add soak steps [32] |

| Ineffective blocking [31] | Try a different blocking buffer (e.g., BSA or serum) [31] | |

| Substrate exposed to light [31] | Protect substrate from light; perform incubation in dark [31] [33] | |

| No Signal | Reagents omitted or added out of sequence [32] | Review protocol; ensure all steps followed [33] |

| Wash buffer contains sodium azide [31] | Use fresh wash buffer without sodium azide [31] | |

| Target below detection limit [31] | Concentrate sample or decrease dilution factor [31] | |

| High Signal | Insufficient washing [32] [33] | Follow washing procedure meticulously; tap plate to remove residue [33] |

| Contaminated substrate/TMB [31] | Use fresh, clean substrate; avoid reusing reservoirs [31] | |

| Incubation time too long [31] [33] | Adhere strictly to recommended incubation times [31] | |

| Poor Replicate Data (High Variation) | Pipetting errors [31] | Calibrate pipettes; ensure tips are tightly sealed [31] |

| Inconsistent washing [32] | Check automated washer nozzles; soak and rotate plate [32] | |

| Cross-contamination [31] | Use fresh plate sealers; change tips between samples [31] | |

| Poor Assay-to-Assay Reproducibility | Buffer contamination [31] [32] | Always prepare fresh buffers [31] |

| Variable incubation temperature [32] [33] | Use a stable, controlled environment; avoid plate stacking [31] [33] | |

| Deviations from protocol [32] | Adhere to the same validated protocol for every run [32] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful screening campaigns rely on high-quality materials. The following table details essential reagents and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| ELISA Microplate | A specialized plate with high protein-binding capacity to ensure effective immobilization of the capture antibody. It is critical to not substitute with tissue culture plates [31] [32] [33]. |

| Blocking Buffer | A solution (e.g., BSA or serum) used to cover any remaining protein-binding sites on the plate after coating, preventing non-specific binding of detection antibodies and reducing background [31]. |

| Coated Capture Antibody | The first, plate-immobilized antibody that specifically binds the target analyte. Proper dilution in PBS and binding to the plate is foundational to assay performance [32] [33]. |

| Detection Antibody | A second antibody that binds the captured analyte. It is often conjugated to an enzyme like HRP, which generates the detectable signal. Concentration must be optimized [31] [32]. |

| TMB Substrate | A colorless solution turned blue by the HRP enzyme. The reaction must be stopped with acid and protected from light, as contamination or light exposure can cause high background [31] [33]. |

| Assay-Ready Plates | Pre-plated compound libraries that eliminate the need for researchers to source, dilute, and plate compounds, dramatically accelerating the initiation of screening campaigns [30]. |

Workflow Visualization: From Library Design to Hit Identification

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of smart library design and screening, which directly addresses the challenge of compound availability by focusing resources on the most promising chemical matter.

Integrated Screening Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Key Steps

Protocol 1: Effective Plate Washing for Low Background Inconsistent washing is a primary source of high background and poor reproducibility.

- Aspiration: Completely remove the liquid from all wells after each incubation step.

- Dispensing: Fill each well completely with wash buffer. Using an automated plate washer is recommended for uniformity.

- Soaking: Incorporate a 30-second soak period after the wash buffer is dispensed. This allows unbound reagents to dissociate from the well surface.

- Draining: After the final wash, invert the plate and tap it firmly onto absorbent tissue to remove any residual fluid [32] [33].

- Prevention: Do not allow wells to dry completely between washes, as this can inactivate the assay [31].

Protocol 2: Mining HTS Data for Novel Chemogenomic Compounds This cheminformatic protocol allows for the expansion of chemogenomic libraries beyond well-annotated compounds, directly addressing the issue of limited compound availability for novel targets.

- Data Collection: Obtain a large set of cellular HTS assay datasets from public repositories like PubChem [34].

- Chemical Clustering: Cluster the tested compounds based on structural similarity.

- Assay Profile Generation: For each cluster, generate an activity profile across all the assays.

- Enrichment Scoring: Use a statistical test (e.g., Fisher's exact test) to identify clusters where the hit rate in specific assays is significantly higher than expected by chance. These clusters demonstrate a "dynamic SAR" (Structure-Activity Relationship) [34].

- Compound Selection: From the prioritized clusters, select the compound whose activity profile best represents the overall cluster profile. These selected compounds, termed "Gray Chemical Matter" (GCM), are enriched for novel mechanisms of action and are ideal candidates for inclusion in a physical, assay-ready library [34].

Overcoming Real-World Bottlenecks: Troubleshooting Quality and Logistics

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a centralized digital inventory in a research context? A centralized digital inventory provides a single, real-time view of all chemical compounds, their quantities, and locations across multiple storage sites or collaborating laboratories [35] [36]. It acts as a unified platform, replacing fragmented records like spreadsheets or individual lab books to become the one source of truth for compound availability [36].

What are the most common challenges a centralized inventory solves?

- Lack of Real-Time Data: Using outdated or siloed systems that cannot provide integrated, real-time data on stock levels and locations [35].

- Disconnected Systems: Fragmented inventory management systems prevent a full, accurate picture of available stock, leading to decisions based on inconsistent data [35].

- Inventory Inaccuracy: Manual errors, incorrect labeling, or stock discrepancies can lead to costly stockouts of critical compounds or overstocking [35].

Our research group is small. Do we need such a system? Even small operations can benefit greatly. Centralized control streamlines inventory management, reduces complexity, and improves operational efficiency by making it easier to track and control stock levels accurately from a single location [37]. This prevents stockouts and overstocking, saving time and resources.

How can we ensure the data in the centralized system is accurate? Conduct regular audits and cycle counts of inventory subsets to verify actual stock against system records [35]. Incorporating barcode or RFID scanning to track inventory levels in real-time also dramatically reduces manual entry errors [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Difficulty locating a specific compound for an experiment.

| Step | Action & Purpose | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Spelling & Identifier : Search the centralized system using the compound's exact ID, CAS number, or synonym. | The compound record is retrieved, showing all available locations and quantities. |

| 2 | Check Physical Audit Trail : If the system shows availability but the vial is missing, check the system's log for the last user who accessed it. | The colleague who last used the compound is identified for follow-up. |

| 3 | Initiate Cycle Count : Conduct a spot check of the specific storage location to reconcile physical stock with system records. | The physical inventory is reconciled with the digital record, correcting any discrepancy. |

Prevention Best Practice: Implement a standardized checkout process within the inventory software every time a compound is physically removed from storage [35].

Problem: The system shows a compound is available, but the vial is empty or degraded.

| Step | Action & Purpose | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Flag in System : Immediately update the compound's status in the centralized system to "Depleted" or "Degraded." | Other researchers are prevented from planning experiments with an unavailable resource. |

| 2 | Annotate Record : Add a note to the compound's digital record detailing the issue (e.g., "appears precipitated as of 2025-11-30"). | Creates a historical record for quality control and informs future purchasing decisions. |

| 3 | Trigger Reorder Alert : If a reorder is necessary, use the system to generate a request or notify the lab manager. | The process to replenish the critical compound is initiated. |

Prevention Best Practice: Set up automated inventory alerts for low stock levels and integrate quality control dates into the compound's digital profile [35].

Problem: Inconsistent data between different lab locations or databases.

| Step | Action & Purpose | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify Source : Determine which systems or spreadsheets are holding conflicting information. | The scope of the data synchronization problem is understood. |

| 2 | Define Master Data : Establish a single, authoritative source for each data field (e.g., compound structure from PubChem, location from main inventory). | A clear rule is set for which data takes precedence during integration. |

| 3 | Re-sync and Validate : Manually update the centralized system with the authoritative data and conduct a physical audit to confirm. | Data integrity is restored across the organization. |

Prevention Best Practice: Eliminate disconnected systems and keep all inventory information across locations in one unified system that provides real-time visibility and updates [35] [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions