Beyond the Pixel: Advanced Morphological Feature Extraction for Next-Generation Phenotypic Profiling in Drug Discovery

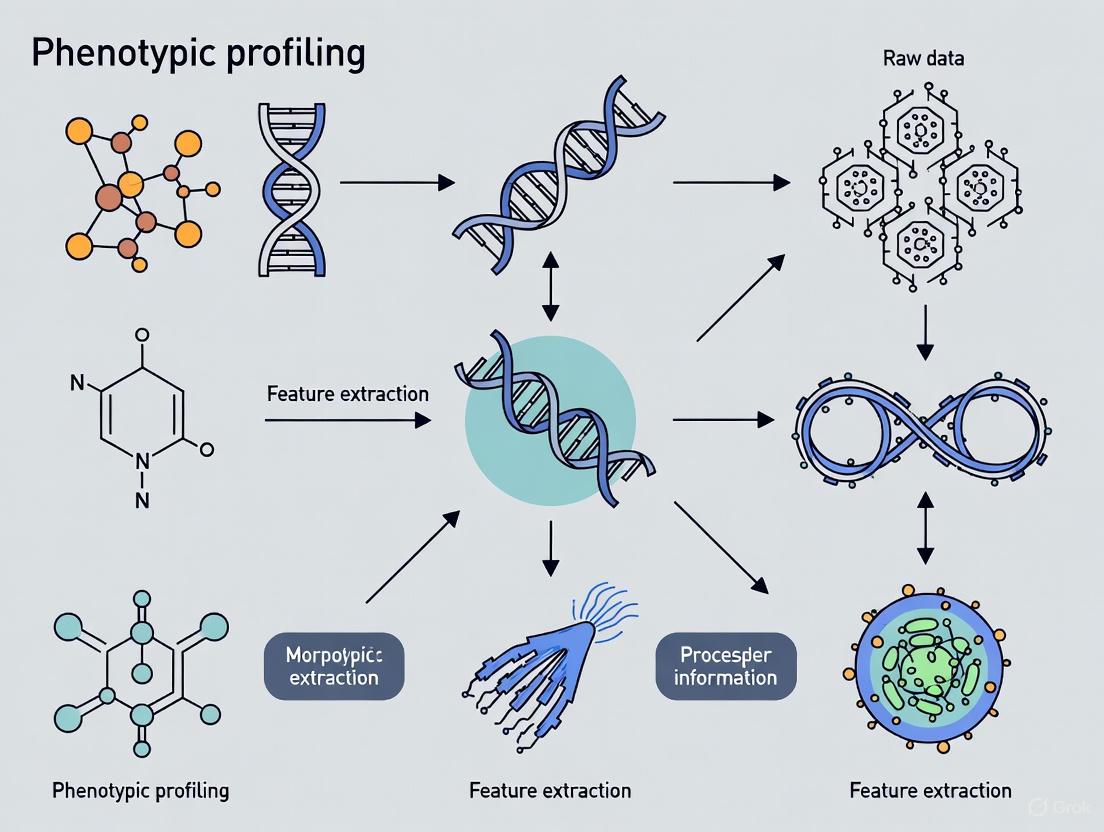

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern morphological feature extraction techniques and their transformative impact on phenotypic profiling, particularly in biomedical research and drug development.

Beyond the Pixel: Advanced Morphological Feature Extraction for Next-Generation Phenotypic Profiling in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern morphological feature extraction techniques and their transformative impact on phenotypic profiling, particularly in biomedical research and drug development. We explore the foundational shift from traditional, manual analysis to automated, high-content methods like the Cell Painting assay, which uses multiplexed fluorescent dyes to capture intricate cellular details. The piece delves into advanced deep learning methodologies, including variational autoencoders (VAEs) and latent diffusion models, that enable landmark-free, high-dimensional analysis of complex biological shapes. We further address key challenges in model optimization and data reproducibility, offering troubleshooting strategies for real-world applications. Finally, the article presents a rigorous validation and comparative analysis framework, demonstrating how morphological profiling enhances the prediction of mechanisms of action (MOAs) and accelerates phenotypic drug discovery by bridging the gap between cellular appearance and biological function.

What is Phenotypic Profiling? Unlocking Cellular Secrets Through Morphology

Morphological analysis has undergone a revolutionary transformation, evolving from qualitative microscopic observations to quantitative, high-dimensional machine-driven profiling. This evolution is particularly impactful in phenotypic profiling research, where extracting meaningful morphological features enables researchers to decipher complex biological states and responses to perturbations [1]. The emergence of high-content imaging and artificial intelligence has propelled this field into the phenomics era, allowing for the systematic correlation of cellular and organismal form with function at unprecedented scale and resolution [1] [2]. This Application Note details the protocols and analytical frameworks essential for modern morphological feature extraction, providing researchers with practical methodologies to advance phenotypic drug discovery and functional genomics.

Traditional Morphological Analysis: Qualitative Microscopy

Traditional morphological analysis relied heavily on direct microscopic observation and manual characterization of physical structures. While now supplemented by advanced techniques, these methods remain fundamental for initial specimen characterization and provide the conceptual foundation for quantitative approaches.

Protocol: Light and Electron Microscopy for Preliminary Analysis

Purpose: To conduct initial morphological assessment of biological samples using microscopy techniques. Scope: Applicable to cellular and sub-cellular samples, as well as tissue sections and small organisms.

Materials:

- Biological sample (e.g., cell culture, tissue section, pollen grain [3])

- Microscope slides and coverslips

- Appropriate fixatives (e.g., glutaraldehyde, formaldehyde)

- Staining solutions (e.g., hematoxylin and eosin, DAPI, phalloidin)

- Light Microscope (LM) and/or Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Fix samples in appropriate fixative for 24 hours at 4°C. Dehydrate through a graded ethanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 100%).

- Staining: Apply stains to highlight specific cellular or structural components.

- Microscopy:

- For LM: Mount samples on slides and observe under appropriate magnification. Capture images using attached digital camera.

- For SEM: Critical-point dry samples, sputter-coat with gold-palladium, and examine under SEM at accelerating voltages of 5-20 kV [3].

- Qualitative Analysis: Document morphological descriptors (e.g., shape, surface patterning, aperture type [3]).

Table 1: Qualitative Morphological Descriptors in Traditional Analysis

| Descriptor Category | Example Features | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Shape | Oblate-spheroidal, prolate, fibrous | Pollen grain identification [3] |

| Surface Pattern | Reticulate, rugulate, fossulate, scabrate | Halophyte plant systematics [3] |

| Aperture Type | Tricolporate, tricolpate, trizonocolporate | Taxonomic delineation in legumes [3] |

| Color/Staining | Eosinophilia, basophilia | Tissue pathology assessment |

| Spatial Arrangement | Clustered, solitary, linear | Cellular organization analysis |

The Shift to Quantitative Morphometrics

The transition to quantitative morphometrics marked a pivotal advancement, replacing subjective descriptions with objective, continuous data. This shift enables robust statistical analysis and phylogenetic comparison [4].

Protocol: Geometric Morphometric Analysis using Landmarks

Purpose: To quantify shape variation using landmark-based data for phylogenetic inference or taxonomic classification. Scope: Suitable for structures with definable homologous points (e.g., skulls, organelles, pollen grains).

Materials:

- Specimen images (2D or 3D)

- Software for landmark digitization (e.g., MorphoJ, tpsDig2)

- Statistical software (e.g., R)

Procedure:

- Landmark Definition: Define Type I (discrete juxtapositions), Type II (maxima of curvature), and Type III (extremal points) landmarks on all specimen images.

- Digitization: Manually place landmarks at corresponding positions across all samples in the dataset.

- Procrustes Superimposition: Scale, translate, and rotate landmark configurations to remove non-shape variation using Generalized Procrustes Analysis (GPA).

- Statistical Analysis: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on Procrustes coordinates to identify major axes of shape variation.

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Use resulting shape variables (e.g., PC scores) in phylogenetic reconstruction algorithms [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Discrete vs. Continuous Morphological Data in Phylogenetics

| Parameter | Discrete Morphological Data | Continuous Morphometric Data |

|---|---|---|

| Data Type | Categorical character states | Continuous measurements or landmark coordinates |

| Subjectivity | High potential for bias in character coding | More objective, but landmark placement can introduce error [4] |

| Information Content | Can lose continuous variation through arbitrary discretization [4] | Retains full shape information |

| Phylogenetic Signal | Variable; can be misleading due to homoplasy | Can be strong, but often confounded with allometric variation [4] |

| Analytical Methods | Parsimony, Bayesian Mk model | Squared-change parsimony, Bayesian Brownian motion models [4] |

| Performance | Traditional standard for fossil integration | Does not consistently improve resolution; requires specialized models [4] |

Modern High-Content Morphological Profiling

Contemporary phenotypic profiling leverages high-content screening and automated image analysis to extract thousands of quantitative features, creating a high-dimensional morphological profile for each sample.

Protocol: Cell Painting Assay for Morphological Profiling

Purpose: To generate comprehensive morphological profiles of cells under different genetic or chemical perturbations using the Cell Painting assay. Scope: Applicable to in vitro cell cultures for drug discovery and functional genomics.

Materials:

- Cell line (e.g., U2OS, A549, Hep G2 [2] [5])

- Cell Painting staining kit: dyes for DNA, ER, RNA, AGP, and Mito [2]

- High-throughput confocal microscope

- ǂ-well microplates

- Automated liquid handling system

- Image analysis software (CellProfiler [2] [5] or DeepProfiler [2])

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Plating: Seed cells into ǂ-well plates and incubate for 24 hours.

- Perturbation: Treat cells with chemical compounds or genetic perturbations at optimized concentrations/durations.

- Staining: Follow standardized Cell Painting protocol:

- Fix cells with formaldehyde.

- Permeabilize with Triton X-100.

- Stain with Hoechst (DNA), Concanavalin A (ER), Syto14 (RNA), Phalloidin (AGP), and MitoTracker (Mito) [2].

- Image Acquisition: Image five channels per well using a high-throughput confocal microscope with a 20x objective.

- Feature Extraction:

- Use CellProfiler to identify individual cells and segment subcellular compartments.

- Extract ~1,500 morphological features per cell (e.g., area, shape, intensity, texture) for each channel [5].

- Data Analysis: Normalize features, aggregate per well, and use multivariate statistics (e.g., PCA) to analyze morphological profiles.

The Machine Learning Frontier: Predictive Morphology

The latest evolution involves using deep learning to not only describe but also predict morphological outcomes from molecular data, dramatically accelerating phenotypic screening.

Protocol: Predicting Morphology with Transcriptome-Guided Diffusion Models

Purpose: To predict cell morphological changes under unseen genetic or chemical perturbations using a transcriptome-guided latent diffusion model (MorphDiff) [2]. Scope: For in-silico phenotypic screening and MOA identification when morphological data is unavailable.

Materials:

- L1000 gene expression profiles for perturbations [2]

- Pre-trained MorphDiff model (available from original publication)

- Cell morphology image dataset for training (e.g., JUMP, CDRP, LINCS [2])

- High-performance computing cluster with GPUs

Procedure:

- Data Curation: Collate paired L1000 transcriptomic profiles and Cell Painting morphology images for a set of training perturbations.

- Model Training:

- Train MVAE: Compress high-dimensional morphology images into low-dimensional latent representations using a Morphology Variational Autoencoder (MVAE).

- Train LDM: Train a Latent Diffusion Model (LDM) to generate morphological latent representations conditioned on perturbed gene expression profiles.

- Prediction:

- Mode 1 (G2I): For a novel perturbation with L1000 data, use MorphDiff to generate predicted morphology from random noise.

- Mode 2 (I2I): Transform an unperturbed cell morphology image to the predicted perturbed state using the novel perturbation's L1000 profile as condition [2].

- Validation: Extract features from generated images using CellProfiler and compare to ground-truth morphological profiles.

Table 3: Performance of MorphDiff in Predicting Mechanisms of Action (MOA)

| Evaluation Metric | MorphDiff (G2I) | MorphDiff (I2I) | Ground-Truth Morphology | Gene Expression Only |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOA Retrieval Accuracy | Comparable to ground-truth | High | Benchmark | Not Specified |

| Improvement over Baselines | +16.9% | +8.0% | N/A | Baseline |

| Performance on Unseen Perturbations | Accurate prediction | Accurate transformation | N/A | N/A |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Morphological Profiling

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Dye Set | Multiplexed staining of major organelles | High-content morphological profiling [2] [5] |

| L1000 Assay Kit | High-throughput gene expression profiling | Generate transcriptomic conditions for MorphDiff [2] |

| Hoechst 33342 | DNA stain; marks nucleus | Cell segmentation and nuclear morphology analysis |

| Phalloidin (Conjugated) | F-actin stain; marks cytoskeleton | Cytoskeletal organization and cell shape analysis |

| MitoTracker | Mitochondrial stain | Mitochondrial morphology and network analysis |

| Concanavalin A (ConA) | Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) stain | ER structure and distribution analysis |

| SYTO 14 | RNA stain; marks nucleoli and cytoplasm | Nucleolar morphology and granularity assessment |

| Pro-Crush Anti-Fade Mountant | Preserves fluorescence for imaging | Long-term storage of stained samples for microscopy |

Cell Painting is a high-content, image-based assay used for cytological profiling that employs a suite of fluorescent dyes to "paint" and visualize multiple cellular components simultaneously [6]. This multiplexed approach allows researchers to capture a comprehensive image of cellular state and organization by highlighting key organelles and structures. The core principle is that changes in cellular morphology reflect the biological state of a cell and its response to genetic, chemical, or environmental perturbations [7] [8].

Originally developed in 2013 by Gustafsdottir et al., the assay was designed to be a low-cost, single assay capable of capturing numerous biologically relevant phenotypes with high throughput [7] [8]. Over the past decade, the protocol has been optimized and standardized, with recent consortium-led efforts (JUMP-Cell Painting) further refining staining reagents, experimental conditions, and imaging parameters to enhance reproducibility and quantitative performance [7]. The assay's ability to generate rich, high-dimensional morphological profiles has made it particularly valuable in phenotypic drug discovery, toxicology, and functional genomics [7] [9].

The Scientific Principle of Morphological Profiling

Conceptual Framework

At its core, Cell Painting operates on the fundamental premise that cellular morphology is intricately linked to cell physiology, health, and function [7]. When cells undergo genetic or chemical perturbations, these changes manifest as alterations in the size, shape, texture, and spatial organization of cellular components [6]. Unlike targeted assays that measure specific, expected phenotypic responses, Cell Painting takes an untargeted approach to capture a broad spectrum of morphological features in an unbiased manner [10]. This makes it particularly valuable for identifying unexpected effects of perturbations and discovering novel biological connections.

The profiling strategy leverages the concept that compounds or genetic perturbations with similar mechanisms of action (MoA) often produce similar morphological profiles, allowing for functional classification based on phenotypic similarity [10] [7]. This approach has proven powerful for MoA identification of uncharacterized compounds, functional annotation of genes, and discovery of novel biological relationships that might be missed by hypothesis-driven assays [9].

Information Content and Profiling Power

The analytical power of Cell Painting stems from its high information density. From each individually segmented cell, automated image analysis software extracts approximately 1,500 morphological measurements across various categories including size, shape, texture, intensity, and spatial relationships between organelles [11] [9]. This multi-parametric profiling at single-cell resolution enables detection of subtle phenotypes that might be invisible to the human eye and allows resolution of cellular subpopulations within heterogeneous samples [6] [9].

When compared to other profiling technologies, Cell Painting offers complementary advantages. While high-throughput transcriptomic profiling methods like L1000 provide population-level gene expression signatures, Cell Painting delivers single-cell resolution of morphological features at a lower cost per sample [9]. Studies have shown that morphological and gene expression profiling capture partially overlapping but distinct information about cell state, suggesting they are orthogonal and powerful when combined [9].

Core Components of the Cell Painting Assay

Standard Dye Panel and Cellular Targets

The foundational Cell Painting assay uses a carefully selected set of six fluorescent dyes to label eight cellular compartments, imaged across five fluorescence channels [11] [9]. This panel was designed to provide comprehensive coverage of major organelles and structures while maintaining compatibility with standard high-throughput microscopes and minimizing cost by using dyes rather than antibodies [9].

Table 1: Standard Dye Panel for Cell Painting Assay

| Cellular Component | Fluorescent Dye | Staining Target | Imaging Channel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleus | Hoechst 33342 | DNA | Blue/DAPI |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum | Concanavalin A, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate | Glycoproteins | FITC/Green |

| Nucleoli & Cytoplasmic RNA | SYTO 14 | RNA | FITC/Green (with ER) |

| Actin Cytoskeleton | Phalloidin, Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate | F-actin | TRITC/Red |

| Golgi Apparatus & Plasma Membrane | Wheat Germ Agglutinin, Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate | Glycoproteins | TRITC/Red (with Actin) |

| Mitochondria | MitoTracker Deep Red | Mitochondrial membrane | Cy5/Far Red |

This standardized set of dyes visualizes a diverse array of cellular structures, enabling the detection of a wide spectrum of morphological changes induced by experimental perturbations [11] [9]. In practice, some dyes with non-overlapping emission spectra are often imaged in the same channel (e.g., RNA and ER; Actin and Golgi) to maximize throughput while maintaining coverage of multiple organelles [10] [8].

Experimental Workflow

The Cell Painting assay follows a standardized workflow that can be completed in approximately two weeks for cell culture and image acquisition, with an additional 1-2 weeks for feature extraction and data analysis [9]. The process involves multiple coordinated stages from sample preparation to computational analysis.

Diagram 1: Cell Painting Workflow. The process begins with cell plating and proceeds through treatment, staining, imaging, and analysis stages to generate morphological profiles.

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementation of the Cell Painting assay requires specific reagents and tools designed for high-content screening applications. Commercial kits and individual components are available to support standardized implementation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Cell Painting

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Image-iT Cell Painting Kit | Pre-optimized dye combination | Simplifies staining with precisely measured reagents for 2 or 10 full multi-well plates [11] |

| Hoechst 33342 | Nuclear DNA stain | Labels nucleus, enables segmentation and nuclear feature extraction [6] [9] |

| MitoTracker Deep Red | Mitochondrial stain | Labels mitochondria, reveals metabolic state and organization [6] [9] |

| Concanavalin A, Alexa Fluor 488 | ER membrane stain | Visualizes endoplasmic reticulum structure and distribution [9] |

| Phalloidin, Alexa Fluor conjugates | F-actin stain | Labels actin cytoskeleton, reveals cell shape and structural changes [9] |

| Wheat Germ Agglutinin, Alexa Fluor conjugates | Golgi and plasma membrane stain | Highlights Golgi apparatus and plasma membrane glycoproteins [9] |

| SYTO 14 green fluorescent nucleic acid stain | RNA stain | Labels nucleoli and cytoplasmic RNA [6] [9] |

| High-content imaging system (e.g., CellInsight CX7) | Automated image acquisition | Designed for multi-well plate imaging at high speed and resolution [11] |

| Image analysis software (e.g., CellProfiler, IN Carta) | Feature extraction | Identifies cells and measures morphological features [6] [8] |

Advanced Methodological Developments

Cell Painting PLUS (CPP): Expanding Multiplexing Capacity

A significant recent advancement is the development of Cell Painting PLUS (CPP), which expands the multiplexing capacity of traditional Cell Painting through iterative staining-elution cycles [10]. This approach enables multiplexing of at least seven fluorescent dyes that label nine different subcellular compartments, including the addition of lysosomes, which are not typically included in the standard assay [10].

The key innovation in CPP is the use of an optimized dye elution buffer (0.5 M L-Glycine, 1% SDS, pH 2.5) that efficiently removes staining signals while preserving subcellular morphologies, allowing for sequential staining and imaging of dyes in separate channels [10]. This eliminates the need to merge signals from multiple organelles in the same imaging channel, thereby improving organelle-specificity and diversity of the phenotypic profiles [10]. The method provides researchers with enhanced flexibility to customize dye panels according to specific research questions while maintaining the untargeted profiling advantages of the original assay.

Alternative Dye Panels and Live-Cell Adaptations

Researchers have explored alternative dye configurations to address specific experimental needs. Recent studies have validated substitutes for standard dyes, including MitoBrilliant as a replacement for MitoTracker and Phenovue phalloidin 400LS for standard phalloidin stains [12]. These substitutions minimally impact assay performance while offering potential advantages such as isolating actin features from Golgi or plasma membrane signals [12].

The development of live-cell compatible dyes such as ChromaLive enables real-time assessment of compound-induced morphological changes, moving the assay from fixed endpoint measurements to dynamic kinetic profiling [12]. This live-cell adaptation provides temporal resolution of phenotypic responses and can be combined with standard Cell Painting to significantly expand the feature space for enhanced cellular profiling [12].

Cell Line Selection and Optimization

While the original Cell Painting protocol was developed using U-2 OS osteosarcoma cells, the assay has been successfully adapted to dozens of biologically diverse cell lines without adjustment to the staining protocol [7] [13]. Studies have systematically evaluated phenotypic profiling across multiple cell types including A549, MCF7, HepG2, and primary cell models [7] [13].

Research has shown that different cell lines vary in their sensitivity to specific mechanisms of action, with some lines better for detecting phenotypic activity (strength of morphological phenotypes) while others excel at predicting mechanism of action (phenotypic consistency with annotated MoAs) [7]. This indicates that cell line selection should be guided by specific screening goals, with some applications benefiting from profiling across multiple cell types to capture complementary biological perspectives [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Sample Preparation and Staining

The Cell Painting protocol begins with plating cells in 96- or 384-well imaging plates at appropriate density to achieve sub-confluent monolayers, typically ranging from 1,000 to 5,000 cells per well depending on cell type [11] [9]. After allowing cells to adhere, they are treated with chemical compounds or genetic perturbations at desired concentrations, followed by incubation for a specified period (typically 24-48 hours) to allow phenotypic manifestation [11].

Staining Procedure:

- Fixation: Aspirate media and fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20-30 minutes at room temperature [9]

- Permeabilization: Incubate with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15-30 minutes [9]

- Staining: Apply dye cocktail containing all six fluorescent dyes simultaneously or in sequence according to manufacturer's recommendations [9]

- Washing: Perform multiple washes with PBS or buffer to remove unbound dye [11]

- Storage: Store plates in sealing foil with desiccant at 4°C if not imaging immediately [11]

Critical considerations during staining include maintaining consistent incubation times across plates, protecting light-sensitive dyes from photobleaching, and confirming dye compatibility to avoid precipitation or interactions [9].

Image Acquisition Parameters

Image acquisition is performed using high-content screening (HCS) systems capable of automated multi-well plate imaging [11]. These systems employ fluorescent imaging specifically designed for maximum speed and data throughput, with combinations of widefield and confocal fluorescence capabilities [11].

Table 3: Image Acquisition Specifications

| Parameter | Specification | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Plate Format | 96- or 384-well | Higher density plates increase throughput |

| Imaging Sites | Multiple positions per well | Ensures adequate cell sampling |

| Magnification | 20x or 40x objective | Balances resolution and field of view |

| Z-dimension | Multiple focal planes | Optional, based on cell thickness |

| Channels | 5 fluorescence channels | Matches dye emission spectra |

| Resolution | ≥ 0.65 μm/pixel (20x) | Sufficient for subcellular features |

| Bit Depth | 12- or 16-bit | Enables quantitative intensity measurements |

Image acquisition time varies based on the number of images per well sampled, sample brightness, and the extent of sampling in the z-dimension [11]. For large-scale screens, acquisition parameters are often optimized to balance data quality with throughput requirements [11].

Image Analysis and Feature Extraction

Image analysis transforms raw microscopy images into quantitative morphological profiles using automated software pipelines. The open-source CellProfiler software is commonly used, though commercial alternatives are also available [8] [9].

Analysis Pipeline:

- Cell Segmentation: Identify individual cells using nuclear stain as primary object followed by cytoplasmic expansion [9]

- Organelle Identification: Detect subcellular compartments within each segmented cell [9]

- Feature Measurement: Extract ~1,500 morphological features per cell across categories [9]

- Data Quality Control: Identify and exclude poor-quality images or segmentation failures [7]

- Data Aggregation: Compile single-cell measurements into population-level profiles [9]

The extracted features encompass multiple measurement categories including intensity (mean, median, standard deviation), texture (Haralick, Zernike features), shape (eccentricity, form factor), size (area, perimeter), and spatial relationships (adjacency, correlation between channels) [9].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Toxicology

Cell Painting has become an invaluable tool in phenotypic drug discovery, where it enables target-agnostic compound evaluation and mechanism of action identification [7]. By clustering compounds based on morphological similarity, researchers can identify novel compounds with desired phenotypic effects, characterize polypharmacology, and detect off-target effects early in the discovery process [7] [9].

In toxicology, Cell Painting has been applied to generate bioactivity profiles for industrial chemicals, with data from over 1,000 chemicals incorporated into the U.S. EPA CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [10] [7]. The assay's sensitivity to diverse cellular stressors makes it particularly valuable for predicting potential hazardous effects of environmental chemicals and understanding their subcellular targets [7].

The integration of Cell Painting with machine learning approaches has further expanded its applications, enabling prediction of compound activities, identification of disease signatures, and discovery of functional gene relationships [7] [8]. Large-scale consortia efforts like JUMP-Cell Painting have generated public datasets of morphological profiles for over 135,000 genetic and chemical perturbations, creating valuable community resources for method development and biological discovery [10] [7].

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Methodological Constraints

Despite its powerful applications, Cell Painting has several technical limitations that researchers must consider. Spectral overlap between fluorescent dyes can constrain multiplexing capacity and necessitate channel sharing, potentially reducing profiling specificity [10] [14]. The requirement for adherent, non-overlapping cells limits application to certain cell types, with non-adherent or compactly growing cells presenting challenges for imaging and analysis [8].

Some biological pathways or targets may not generate detectable morphological changes within the resolution of standard Cell Painting, creating potential biological blind spots in profiling experiments [14]. Additionally, the assay's sensitivity to batch effects from variations in cell culture conditions, staining protocols, or imaging parameters requires careful experimental design and normalization strategies to ensure robust, reproducible results [7] [14].

Computational Challenges

The high-dimensional nature of Cell Painting data presents significant computational challenges. The substantial data storage and processing requirements - with single experiments generating terabytes of images and millions of single-cell measurements - demand robust computational infrastructure [11] [8]. Analysis of high-dimensional feature spaces introduces statistical difficulties including spurious correlations and multiple testing challenges that require appropriate correction methods [8].

Currently, no established routine analytical protocol exists for all applications, requiring researchers to adapt and validate analysis pipelines for specific experimental contexts [8]. The interpretation of morphological profiles in terms of underlying biology can also be non-trivial, as morphological changes may represent integrated responses to multiple underlying molecular events [8].

The future of Cell Painting will likely involve continued integration with emerging computational and experimental techniques [7]. Advances in deep learning for image analysis may enable direct extraction of biologically relevant features from raw images without predefined measurement sets, potentially capturing more subtle and complex phenotypes [7] [8]. The generation of larger public datasets will support training of more powerful models and enable broader biological discoveries [7].

Methodologically, approaches like Cell Painting PLUS that expand multiplexing capacity and improve organelle-specificity represent an important direction for enhancing the resolution and biological interpretability of morphological profiling [10]. Similarly, live-cell adaptations and integration with other omics technologies (transcriptomics, proteomics) will provide more comprehensive views of cellular responses to perturbations [7] [12].

In conclusion, Cell Painting has established itself as a powerful, versatile tool for morphological profiling that continues to evolve through methodological refinements and expanding applications. Its ability to capture rich, high-dimensional information about cellular state in an untargeted manner makes it particularly valuable for phenotypic drug discovery, toxicology, and functional genomics. As the assay becomes more widely adopted and integrated with complementary technologies, it promises to yield further insights into cellular biology and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

In phenotypic profiling research, the quantitative analysis of cellular morphology provides a powerful window into cellular state and function. Image-based cell profiling enables the quantification of hundreds of morphological features from populations of cells subjected to chemical or genetic perturbations, creating distinctive "morphological profiles" that can reveal biologically relevant similarities and differences [15]. This approach critically depends on precise and specific labeling of key cellular components—nuclei, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and the cytoskeleton—to extract meaningful data about cell health, organization, and response to stimuli. These application notes provide detailed protocols and reagent solutions for comprehensive cellular labeling, framed within the context of morphological feature extraction for drug discovery and basic research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents for labeling key cellular components

| Cellular Component | Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Example Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclei | Cell-permeant nucleic acid stains | Label DNA in live or fixed cells; viability assessment | Hoechst stains, DAPI [16] [17] |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum | ER-Tracker dyes | Live-cell staining selective for ER; bind to sulfonylurea receptors | ER-Tracker Blue-White DPX, ER-Tracker Green/Red [17] |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum | CellLight reagents | BacMam vectors encoding fluorescent protein fusions | CellLight ER-GFP/RFP (calreticulin-KDEL fusion) [17] |

| Mitochondria | TMRM (Tetramethylrhodamine, methyl ester) | Cell-permeant dye that accumulates in active mitochondria with intact membrane potential | TMRM [18] |

| Mitochondria | abberior LIVE mito probes | Cristae-specific labeling for super-resolution STED microscopy | abberior LIVE RED/ORANGE mito [19] |

| Golgi Apparatus | Fluorescent ceramide analogs | Selective stains for Golgi apparatus; metabolized to fluorescent sphingolipids | BODIPY FL C5-ceramide, NBD C6-ceramide [17] |

| Cytoskeleton (Actin) | Fluorescent phalloidin conjugates | High-affinity F-actin binding for fixed cells | Not specified in search results |

| Cytoskeleton (Microtubules) | Immunofluorescence reagents | Antibody-based labeling of tubulin in fixed cells | Not specified in search results |

Experimental Protocols for Key Cellular Labeling

Nuclear Staining Protocol

This protocol provides general instructions for labeling cell nuclei using nucleic acid stains, which exhibit minimal fluorescence before binding nucleic acids and significant intensity increases after binding [16].

Materials Required:

- Cells (adherent or suspension)

- Staining medium (complete cell culture medium or saline-based buffer like PBS/HBSS)

- Nuclear stain (e.g., Hoechst stains)

- Fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter set

Procedure:

- Prepare staining solution: Create 1 mL of nuclear dye staining solution at desired concentration. For most nuclear dyes, a 1 μM staining solution diluted from a 1 mM working solution is appropriate. Prepare multiple concentrations if optimizing [16].

- Remove medium: Aspirate existing medium from cells.

- Apply staining solution: Add sufficient staining solution to completely cover the sample.

- Incubate: Incubate for 5-15 minutes at room temperature or 37°C for most nuclear dyes. Some live-cell dyes may require longer incubation [16].

- Optional wash: For live-cell imaging with high-affinity stains, remove staining solution and wash to improve signal-to-background ratio.

- Image cells: Visualize using a fluorescence microscope with filter sets matched to your fluorophore.

Notes: The choice between complete medium and saline-based buffer depends on experimental design. Use complete medium for viability assays in live cell populations, and saline-based buffers for counterstaining during immunolabeling [16].

Endoplasmic Reticulum Staining Protocol

Option A: Using ER-Tracker Dyes for Live-Cell Imaging

ER-Tracker dyes are cell-permeant, live-cell stains highly selective for the endoplasmic reticulum with minimal mitochondrial staining [17].

Materials Required:

- Live cells

- ER-Tracker dye (Blue-White DPX, Green, or Red)

- Pre-warmed live-cell imaging medium

- DMSO for stock solutions

- Fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets

Procedure:

- Prepare stock solution: Dissolve ER-Tracker dye in DMSO according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Prepare working solution: Dilute stock solution in pre-warmed imaging medium to recommended working concentration.

- Replace medium: Remove existing cell culture medium and rinse cells with pre-warmed imaging medium.

- Apply staining solution: Add sufficient ER-Tracker working solution to cover cells.

- Incubate: Incubate for 15-30 minutes at 37°C under appropriate CO₂ conditions.

- Wash: Remove staining solution and rinse cells 2-3 times with fresh imaging medium.

- Image: Immediately image live cells using appropriate fluorescence filter sets.

Option B: Using CellLight BacMam Reagents

CellLight reagents provide highly specific ER labeling through BacMam expression of fluorescent protein fusions with ER targeting sequences [17].

Procedure:

- Plate cells: Seed cells in appropriate imaging chamber at least 16 hours before transduction.

- Add reagent: Simply add CellLight ER-GFP or ER-RFP reagent directly to cells.

- Incubate: Incubate for 16-24 hours to allow for gene expression and protein localization.

- Image: Visualize using standard GFP or RFP filter sets.

Validation Considerations: When expressing ER fluorescent reporters, confirm that overexpression does not significantly impact ER morphology by comparing to untransfected cells stained with ER antibodies (e.g., anti-PDI) [20].

Functional Mitochondrial Staining Protocol

This protocol uses TMRM (Tetramethylrhodamine, methyl ester) to detect mitochondria with intact membrane potentials, where signal intensity correlates with mitochondrial activity [18].

Materials Required:

- Live cells

- Complete cell culture medium

- TMRM (Tetramethylrhodamine, methyl ester)

- DMSO for stock solution

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Fluorescence microscope with TRITC filter set

Procedure:

- Prepare stock solution: Make a 10 mM TMRM stock solution in DMSO and store at -20°C [18].

- Prepare intermediate dilution: Create 50 μM intermediate dilution by adding 1 μL of 10 mM TMRM to 200 μL complete medium.

- Prepare staining solution: Make 250 nM staining solution by adding 5 μL of 50 μM TMRM to 1 mL complete medium.

- Remove media: Aspirate medium from live cells.

- Apply staining solution: Add TMRM staining solution to cells.

- Incubate: Incubate for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Wash: Wash cells 3 times with PBS or other clear buffer.

- Image: Visualize using TRITC filter sets.

Alternative Advanced Protocol: abberior LIVE Mito Probes

For super-resolution imaging of mitochondrial cristae [19]:

- Prepare stock: Dissolve abberior LIVE mito probe in DMF or DMSO to make 1 mM stock.

- Prepare staining solution: Dilute stock in pre-warmed live-cell imaging medium to 250-500 nM final concentration.

- Replace medium: Remove culture medium and rinse with pre-warmed imaging medium.

- Stain cells: Add staining solution and incubate for 45-60 minutes at optimal growth conditions.

- Wash: Rinse 3 times with fresh imaging medium, followed by additional 15-20 minute wash.

- Image: Mount samples and immediately image with appropriate microscope systems.

Cytoskeleton Imaging Approaches

While specific staining protocols for cytoskeletal elements are not detailed in the search results, several imaging modalities and considerations are documented for cytoskeleton visualization.

Actin Cytoskeleton Imaging: The actin cytoskeleton can be visualized in various assembly formations that provide framework for cell shape, motility, and intracellular organization [21]. Imaging approaches include:

- Fixed cells: Fluorescent phalloidin conjugates for F-actin staining

- Live cells: GFP-actin fusion proteins or actin-binding domain probes

Microtubule Imaging: Microtubules are highly dynamic structures composed of α- and β-tubulin heterodimers that radiate from the centrosome [21]. They can be visualized using:

- Immunofluorescence: Antibodies against α- or β-tubulin in fixed cells

- Live-cell imaging: GFP-tubulin fusions or chemical probes

Recommended Microscopy Techniques:

- Spinning disk confocal microscopy (SDCM): Ideal for rapid dynamics of actin filaments and focal adhesion complexes [21]

- Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM): Provides optical sectioning for 3D reconstruction of cytoskeletal architecture [21]

Workflow Integration for Morphological Profiling

The integration of multiple cellular labeling strategies enables comprehensive morphological profiling for phenotypic screening. The diagram below illustrates the complete workflow from sample preparation to data analysis.

Image Analysis and Quality Control for Profiling

High-quality morphological profiling requires rigorous image analysis and quality control to ensure data integrity [15].

Illumination Correction: Correct for inhomogeneous illumination using:

- Retrospective multi-image methods: Build correction functions using all images in experiment for most robust results [15]

- Prospective methods: Use reference images taken at time of acquisition (less recommended)

- Retrospective single-image methods: Calculate correction for each image individually (can alter relative intensity)

Segmentation Approaches:

- Model-based segmentation: Use a priori knowledge of expected object size and shape with algorithms like thresholding and watershed transformation [15]

- Machine learning-based segmentation: Train classifiers on manually labeled ground-truth data for difficult segmentation tasks [15]

Feature Extraction for Profiling:

- Shape features: Perimeter, area, roundness of nuclei, cells, or organelles [15]

- Intensity-based features: Mean intensity, maximum intensity within cellular compartments [15]

- Texture features: Mathematical functions to quantify intensity regularity and patterns [15]

- Microenvironment features: Spatial relationships between cells and organelles [15]

Table 2: Quantitative parameters for mitochondrial membrane potential assessment

| Parameter | Normal Range | Interpretation | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMRM Intensity | Cell-type dependent | Bright signal indicates intact ΔΨm; dim signal indicates depolarization | Mean fluorescence intensity per cell [18] |

| Incubation Time | 30 minutes at 37°C | Optimal for dye accumulation | Time at 37°C [18] |

| Working Concentration | 250 nM | Balance between signal intensity and potential toxicity | Dilution from stock [18] |

| Incubation Temperature | 37°C | Critical for proper dye uptake and mitochondrial function | Environmental control [20] |

Critical Considerations for Experimental Design

Live Cell Imaging Requirements

For dynamic imaging of organelle interactions and processes, maintain cells under physiological conditions:

- Temperature control: Pre-warm stage warmer or environmental housing for at least 20 minutes before experiments [20]

- Environmental control: Maintain appropriate CO₂, humidity, and pH conditions throughout imaging [19]

- Minimal phototoxicity: Use low dye concentrations and optimize exposure times to reduce cellular stress [19]

Multiplexing and Experimental Validation

- Dye compatibility: Ensure spectral separation between fluorophores for multi-component labeling

- Expression validation: Confirm that fluorescent reporter expression doesn't alter native organelle morphology [20]

- Controls included: Always include appropriate controls (untreated, vehicle-only, and positive controls)

- Morphological assessment: Quantitate fluorescence intensities and correlate with potential structural alterations [20]

Comprehensive labeling of nuclei, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and cytoskeletal elements provides the foundation for quantitative morphological profiling in phenotypic research. The protocols and reagents detailed in these application notes enable researchers to capture the complex interplay between cellular compartments and extract meaningful data about cellular state in response to genetic, chemical, or environmental perturbations. When properly implemented within a rigorous analytical workflow, these labeling strategies support the generation of high-quality morphological profiles that can reveal novel biological insights and accelerate drug discovery efforts.

Morphological profiling via feature extraction represents a transformative approach in phenotypic screening, enabling the quantification of cellular states induced by genetic or chemical perturbations [22]. This process transforms raw, high-dimensional image data into informative, numerical descriptors that capture essential biological information. By systematically analyzing intensity, texture, shape, and spatial features, researchers can obtain unbiased bioactivity profiles that predict the mode of action (MoA) for unexplored compounds and uncover unanticipated activities for characterized small molecules [22]. These profiles have become indispensable tools in early-stage drug discovery, allowing for the detection of bioactivity in a broader biological context [22]. This protocol details the comprehensive methodology for extracting multifaceted features critical for robust morphological profiling and phenotypic analysis.

Morphological profiling leverages automated imaging and advanced image analysis to record alterations in cellular architecture by detecting hundreds of quantitative features in high-throughput experiments [22]. Feature extraction serves the critical function of transforming raw image data into compact, informative representations, enabling efficient analysis, recognition, and classification in modern image processing and computer vision applications [23]. This process is fundamental for dimensionality reduction, separating crucial features to improve accuracy in classification tasks, and enhancing system performance for real-time applications while effectively reducing noise [24].

In phenotypic profiling, the morphological profile induced by a small molecule provides a rich, rather unbiased description of the perturbed cellular state, creating a distinctive signature that can be compared to profiles of compounds with known mechanisms [22]. The systematic categorization of features includes:

- Geometric Features: Capturing structural relationships and object shapes.

- Statistical Features: Providing quantitative descriptors of intensity distributions.

- Texture-Based Techniques: Highlighting surface characteristics and spatial patterns using methods like Local Binary Patterns (LBP) and Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) [23].

- Spatial Features: Describing object prominence and organizational context within an image [25].

Comprehensive Feature Taxonomy and Quantitative Comparison

The following tables summarize the core feature categories extracted in morphological profiling, their specific metrics, and their primary biological applications.

Table 1: Core Feature Categories in Morphological Profiling

| Feature Category | Sub-category | Key Metrics | Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | Statistical | Mean, Median, Standard Deviation, Minimum/Maximum Pixel Values | Protein expression levels, drug accumulation, cellular health |

| Histogram-based | Mode, Entropy, Kurtosis, Skewness | Content distribution analysis, phenotype classification | |

| Texture | Statistical | Contrast, Correlation, Energy, Homogeneity (from GLCM) [24] | Cytoskeletal organization, chromatin patterning, organelle distribution |

| Structural | Local Binary Patterns (LBP) [23] | Surface characterization, repetitive pattern identification | |

| Spectral | Gabor Filter responses [24] | Pattern analysis at multiple scales and orientations | |

| Shape | Contour-based | Area, Perimeter, Eccentricity, Major/Minor Axis Length | Nuclear morphology, cell shape analysis, morphological changes |

| Moment-based | Hu Moments, Zernike Moments | Object recognition and orientation | |

| Spatial | Object Prominence | Size, Centeredness, Image Depth [25] | Analyzing cellular organization and relational context |

| Topological | Nearest Neighbor Distance, Voronoi Tessellation, Delaunay Triangulation | Spatial organization analysis, tissue architecture |

Table 2: Computational Characteristics of Feature Extraction Methods

| Extraction Method | Computational Complexity | Noise Sensitivity | Dimensionality of Output | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edge Detection (Canny) [24] | Medium | Low-Medium | Variable (edge pixels) | Cell boundary detection, segmentation |

| Corner Detection (Harris) [24] | Low | Medium | Variable (corner points) | Feature point matching, tracking |

| Blob Detection (LoG/DoG) [24] | High | Low | Variable (blob regions) | Spot detection (vesicles, nuclei), counting |

| GLCM Texture [24] | Medium-High | Medium | Fixed (multiple features) | Texture classification, pattern analysis |

| LBP [23] [24] | Low | Low | Fixed (histogram) | Real-time texture classification, face recognition |

| Gabor Filters [24] | High | Low | Fixed (multiple features) | Multi-scale texture analysis, frequency analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Feature Extraction

Protocol 1: Intensity and Texture Feature Extraction

Purpose: To quantify pixel value distributions and textural patterns in cellular images.

Materials:

- Fluorescent or brightfield cellular images

- Image processing software (e.g., Python with OpenCV, ImageJ)

- Segmentation masks identifying cellular regions of interest

Procedure:

- Image Preprocessing:

- Apply Gaussian smoothing with a 3×3 kernel to reduce noise [24].

- Normalize intensity across image sets using histogram equalization.

- Convert to grayscale if working with color images.

Intensity Feature Extraction:

- For each segmented cellular region, calculate:

- Mean, median, and standard deviation of pixel intensities.

- Intensity histogram skewness and kurtosis.

- Minimum and maximum pixel values within the region.

- Record values for statistical analysis.

- For each segmented cellular region, calculate:

Texture Feature Extraction using GLCM:

- Calculate Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix for distances [1, 2] and angles [0°, 45°, 90°, 135°].

- Compute Haralick features from GLCM:

- Contrast:

∑(i,j)‖i-j‖²·p(i,j) - Correlation:

∑(i,j)((i-μi)(j-μj)p(i,j))/(σiσj) - Energy:

∑(i,j)p(i,j)² - Homogeneity:

∑(i,j)p(i,j)/(1+‖i-j‖)[24]

- Contrast:

Texture Feature Extraction using LBP:

- For each pixel, compare with its 8 surrounding neighbors.

- Generate binary pattern: 1 if neighbor ≥ center, else 0.

- Convert binary pattern to decimal value.

- Create LBP histogram for the region [24].

Troubleshooting:

- High background intensity: Adjust segmentation thresholds or apply background subtraction.

- Inconsistent staining: Normalize intensities across batches using control samples.

Protocol 2: Shape and Spatial Feature Extraction

Purpose: To quantify morphological characteristics and spatial relationships of cellular structures.

Materials:

- Segmented binary masks of cellular structures

- Computational geometry libraries (e.g., SciPy, scikit-image)

Procedure:

- Shape Feature Extraction:

- For each segmented object, calculate:

- Area: Total number of pixels in the region.

- Perimeter: Distance around the boundary of the region.

- Eccentricity: Ratio of the distance between foci of ellipse and its major axis length.

- Major and Minor Axis Lengths: Dimensions of the fitted ellipse.

- Solidity: Ratio of area to convex hull area.

- For each segmented object, calculate:

Contour-Based Analysis:

- Detect contours using border following algorithms.

- Approximate contours to reduce complexity.

- Calculate contour moments for shape representation.

Spatial Feature Extraction:

- Calculate Object Prominence metrics:

- Size: Normalized area relative to image dimensions.

- Centeredness: Distance from object centroid to image center.

- Saliency: Using saliency detection algorithms to estimate visual attention [25].

- Compute spatial relationships:

- Nearest Neighbor Distances between objects.

- Voronoi Tessellation of object centroids.

- Delaunay Triangulation of object centroids.

- Calculate Object Prominence metrics:

Spatial Statistics:

- Ripley's K-function to analyze clustering or dispersion.

- Pair correlation function for spatial patterns at different scales.

Troubleshooting:

- Overlapping objects: Use watershed segmentation or marker-controlled approaches.

- Small/fragmented objects: Apply morphological operations (closing) before analysis.

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for morphological feature extraction from cellular images, showing the sequential process from raw images to analyzable profiles.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Morphological Profiling

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Image Acquisition | High-content screening microscope | Automated acquisition of cellular images at scale |

| Cell painting assay reagents | Multiplexed staining of multiple organelles | |

| Image Processing | Python/OpenCV [24] | Implementation of feature extraction algorithms |

| ImageJ/Fiji | Open-source image analysis with plugin ecosystem | |

| CellProfiler | Domain-specific software for biological image analysis | |

| Feature Extraction | Scikit-image | Python library for image analysis algorithms |

| Mahotas | Computer vision library for biological image analysis | |

| Data Analysis | R/Python pandas | Data manipulation and statistical analysis |

| Scikit-learn | Machine learning for phenotype classification | |

| Specialized Algorithms | Canny Edge Detector [24] | Reliable boundary detection for cell segmentation |

| Harris/Shi-Tomasi Corner Detector [24] | Interest point detection for tracking | |

| Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) [24] | Blob detection for vesicles and organelles |

Analysis and Integration of Multimodal Features

Integrating multiple feature types creates a more robust and accurate representation of cellular morphology than any single feature category alone [23]. The fusion of intensity, texture, shape, and spatial features enables a comprehensive phenotypic profile that captures both intrinsic cellular characteristics and their organizational context.

Integrated Analysis Workflow:

- Feature Normalization: Standardize features across different scales using Z-score normalization or min-max scaling.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) to visualize high-dimensional feature space.

- Clustering Analysis: Use k-means or hierarchical clustering to identify distinct phenotypic clusters.

- Classification: Train supervised classifiers (Random Forest, SVM) to predict treatment classes or mechanisms of action.

- Similarity Scoring: Compute distances between profiles (e.g., Euclidean, Mahalanobis) to identify similar morphological responses.

The prominence of objects within images, as determined by factors like size, centeredness, and saliency, provides crucial contextual information for interpreting morphological features [25]. This spatial context enhances the biological interpretability of profiling data by distinguishing primary phenotypic effects from secondary changes.

Morphological profiling through comprehensive feature extraction provides a powerful framework for quantitative phenotypic analysis in drug discovery and basic research. By systematically quantifying intensity, texture, shape, and spatial characteristics, researchers can create rich, informative profiles that capture subtle biological states induced by genetic or chemical perturbations. The integrated approaches discussed here, combining multiple feature types and considering object prominence, enhance the robustness and biological relevance of analyses performed at scale. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they will further enable the detection of bioactivity in compound collections and the prediction of mechanisms of action, accelerating therapeutic development and fundamental biological discovery.

Image-based phenotypic profiling is a powerful method that combines automated microscopy and computational analysis to identify phenotypic alterations in cell morphology, providing critical insight into a cell's physiological state [26]. This approach quantitatively compares cell morphology after various chemical or genetic perturbations, enabling researchers to identify meaningful similarities and differences in the same way transcriptional profiles are used to compare samples [27]. The fundamental premise is that disturbances in cellular pathways and processes manifest as detectable changes in microscopic appearance, creating a bridge between observable morphology and underlying biology.

The field has progressed significantly through consortium efforts like the JUMP Cell Painting Consortium, which brings together pharmaceutical companies, non-profit institutions, and supporting companies to advance methodological development [27]. These collaborations have enabled the creation of benchmark datasets such as CPJUMP1, containing approximately 3 million images and morphological profiles of 75 million single cells treated with carefully matched chemical and genetic perturbations [27]. Such resources provide the foundation for optimizing computational strategies to represent cellular samples so they can be effectively compared to uncover valuable biological relationships.

Key Concepts and Biological Significance

Core Principles

Phenotypic profiling operates on several core principles. First, different perturbation types targeting the same biological pathway often produce similar morphological changes, creating recognizable profiles. Second, the directionality of correlations among perturbations targeting the same protein can be systematically explored, with some showing positive correlations (similar phenotypes) and others showing negative correlations (opposing phenotypes) [27]. Finally, these morphological profiles are reproducible across experimental replicates and can be detected using appropriate computational methods.

The biological significance of this approach lies in its ability to connect morphological patterns to specific biological states without prior knowledge of the underlying mechanisms. This makes it particularly valuable for identifying mechanisms of action for uncharacterized compounds, discovering novel gene functions, and understanding disease pathologies through comparative analysis of patient-derived cells [27].

Analytical Framework

The analytical framework for phenotypic profiling typically involves several stages: perturbation application, image acquisition, feature extraction, profile generation, and similarity analysis. In the final stage, cosine similarity or its absolute value is commonly used as a correlation-like metric to measure similarities between pairs of well-level aggregated profiles [27]. The statistical significance of these similarities is then assessed using permutation testing with false discovery rate correction to account for multiple comparisons.

Table: Benchmark Performance of Phenotypic Profiling Representations

| Perturbation Type | Cell Type | Time Point | Fraction Retrieved | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Compounds | U2OS, A549 | 2 time points | Higher than genetic | Most distinguishable from negative controls |

| CRISPR Knockout | U2OS, A549 | 2 time points | Intermediate | More detectable than overexpression |

| ORF Overexpression | U2OS, A549 | 2 time points | Lower than others | Weakest signal, potentially due to plate layout effects |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Cell Painting Assay Protocol

The Cell Painting assay is the most widely used protocol for phenotypic profiling [27]. The following detailed methodology outlines the key experimental steps:

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell lines (e.g., U2OS osteosarcoma, A549 lung carcinoma)

- Perturbations (chemical compounds, CRISPR guides, ORF constructs)

- Cell culture reagents and media

- Staining dyes: MitoTracker (mitochondria), Phalloidin (actin), Concanavalin A ( endoplasmic reticulum), SYTO 14 (nucleic acids), and Wheat Germ Agglutinin ( Golgi and plasma membrane)

- Fixative: 4% formaldehyde in PBS

- Permeabilization buffer: 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS

- Washing buffer: 1X PBS

- 384-well imaging plates

Procedure:

- Plate Cells: Seed appropriate cell density in 384-well plates, optimizing for confluency at time of imaging.

- Perturbation Application: Apply chemical or genetic perturbations in replicate wells across multiple plates. Include negative controls (DMSO or empty vector) and positive controls if available.

- Incubation: Incubate cells for predetermined time points (e.g., 24h, 48h, 96h) at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

- Fixation: Aspirate media and add 4% formaldehyde solution for 15-20 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilization: Aspirate fixative, add permeabilization buffer for 10-15 minutes.

- Staining: Apply staining cocktail containing all five dyes for 30-60 minutes protected from light.

- Washing: Perform 3×5 minute washes with 1X PBS.

- Storage: Add fresh PBS and store plates at 4°C protected from light until imaging.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire images using high-content microscopy systems with appropriate filters for each fluorescent channel.

Critical Considerations:

- Plate layout should randomize perturbation positions to minimize positional effects

- Include sufficient replicates for statistical power (typically 4-8 replicates per perturbation)

- Maintain consistent imaging parameters across all plates and experimental batches

- Include reference controls for assay quality assessment

Image Analysis and Feature Extraction Workflow

The following workflow transforms acquired images into quantitative morphological profiles:

Detailed Protocol Steps:

Image Preprocessing

- Correct for background fluorescence and uneven illumination

- Apply flat-field correction if required

- Register multiple channels if necessary

- Quality control to exclude out-of-focus images

Cell and Organelle Segmentation

- Use nuclei staining to identify individual cells

- Apply cytoplasm segmentation using actin or plasma membrane markers

- Segment individual organelles using specific channel information

- Validate segmentation accuracy manually for a subset

Feature Extraction

- Extract morphological features for each cell and subcellular compartment

- Include measurements for size, shape, intensity, texture, and spatial relationships

- Calculate both classical hand-engineered features and deep-learning derived features

- Generate population-level statistics for each well

Profile Generation and Normalization

- Aggregate single-cell measurements to well-level profiles

- Apply normalization to remove technical artifacts (plate, batch effects)

- Use control-based normalization (e.g., using in-distribution control experiments)

- Perform feature selection to reduce dimensionality

Data Analysis and Computational Approaches

Feature Representation Strategies

Different computational approaches can be employed to represent the morphological profiles:

Classical Representations: Rely on hand-engineered features carefully developed and optimized to capture cellular morphology variations, including size, shape, intensity, and texture of various stains [27]. These features require post-processing steps including normalization, feature selection, and dimensionality reduction.

Anomaly-Based Representations: Use the abundance of control wells to learn the in-distribution of control experiments and formulate a self-supervised reconstruction anomaly-based representation [26]. These representations encode intricate morphological inter-feature dependencies while preserving interpretability and have demonstrated improved reproducibility and mechanism of action classification compared to classical representations.

Deep Learning Representations: Automatically identify features directly from pixels using representation learning algorithms [27]. These methods can capture more complex patterns but may be harder to biologically interpret without specialized explainability techniques.

Table: Comparison of Feature Representation Methods

| Representation Type | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Features | Hand-engineered morphological measurements | Biologically interpretable, established methods | May not capture full complexity of cellular organization |

| Anomaly Representations | Encodes deviations from control morphology | Improved reproducibility, reduces batch effects | Requires sufficient control data for training |

| Deep Learning Features | Learned directly from raw images | Potential to capture novel patterns, minimal preprocessing | Hard to interpret biologically, requires large datasets |

Perturbation Detection and Matching

Two critical analytical tasks in phenotypic profiling are perturbation detection and matching:

Perturbation Detection: Identifies perturbations that produce statistically significant morphological changes compared to negative controls. This is often measured using average precision to retrieve replicate perturbations against the background of negative controls, with statistical significance assessed using permutation testing and false discovery rate correction [27].

Perturbation Matching: Identifies genes or compounds that have similar impacts on cell morphologies. Improved matching enables better discovery of compound mechanisms of action and virtual screening for useful gene-compound relationships [27].

The following diagram illustrates the computational pipeline for these analyses:

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful phenotypic profiling requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for consistency and reproducibility:

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Profiling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | U2OS (osteosarcoma), A549 (lung carcinoma) | Provide consistent cellular context for perturbation studies; different cell types may show varying sensitivity to perturbations |

| Chemical Perturbations | Drug Repurposing Hub compounds | Well-annotated compounds with known targets enable ground truth for method validation and mechanism of action studies |

| Genetic Perturbations | CRISPR guides, ORF overexpression constructs | Target specific genes to establish causal relationships between gene function and morphological phenotypes |

| Staining Dyes | MitoTracker, Phalloidin, Concanavalin A, SYTO 14, Wheat Germ Agglutinin | Visualize specific subcellular compartments to capture comprehensive morphological information |

| Imaging Plates | 384-well imaging-optimized plates | Provide consistent imaging surface with minimal background fluorescence and optical distortion |

| Reference Controls | DMSO, empty vectors, known pathway modulators | Enable normalization and quality control across experiments and batches |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Functional Genomics

Phenotypic profiling enables several critical applications in biological research and drug development:

Mechanism of Action Identification: By comparing morphological profiles of compounds with unknown mechanisms to those with known targets, researchers can generate hypotheses about compound mechanisms [27]. The availability of datasets with matched chemical and genetic perturbations, where each perturbed gene's product is a known target of at least two chemical compounds, significantly enhances this capability.

Functional Gene Discovery: Clustering large sets of genetically perturbed samples reveals relationships among genes, helping to assign function to uncharacterized genes [27]. Different perturbation mechanisms (CRISPR knockout vs. ORF overexpression) can provide complementary information about gene function.

Disease Mechanism Elucidation: Comparing cells from patients with specific diseases to healthy controls can identify disease-specific morphological signatures and potentially reveal underlying disease mechanisms.

Toxicity Assessment: Detracting morphological changes associated with cellular stress or death can provide early indicators of compound toxicity.

The following diagram illustrates the primary application workflows:

Future Directions and Methodological Advancements

The field of phenotypic profiling continues to evolve with several promising directions:

Integration with Other Data Modalities: Combining morphological profiles with transcriptional, proteomic, or metabolic data provides multi-dimensional views of cellular states.

Improved Representation Learning: Self-supervised and semi-supervised approaches that better leverage unlabeled data or limited annotations may enhance feature learning, particularly anomaly representations that encode morphological inter-feature dependencies [26].

Explainable AI: Developing methods to biologically interpret deep learning models and anomaly representations will be crucial for building trust and extracting biological insights [26].

Standardized Benchmarking: Resources like the CPJUMP1 dataset enable systematic comparison of computational methods and establish benchmarks for the field [27].

As these methodological advancements mature, phenotypic profiling is poised to become an increasingly powerful approach for connecting cellular morphology to underlying biology, accelerating discovery in basic research and drug development.

From Data to Discovery: AI-Powered Methodologies for Morphological Profiling

In the field of phenotypic profiling research, quantitative analysis of cellular and organismal morphology is paramount for deciphering developmental processes, disease states, and drug responses. Traditional morphological analysis has long relied on landmark-based geometric morphometrics, which requires manual annotation of anatomically homologous points by experts. This approach presents significant limitations, including difficulties in comparing phylogenetically distant species, information loss from insufficient landmarks, and inter-researcher variability in landmark placement [28]. To overcome these challenges, the Morphological Regulated Variational AutoEncoder (Morpho-VAE) framework represents a transformative advancement by enabling landmark-free shape analysis through deep learning.

Morpho-VAE constitutes an image-based deep learning framework that combines unsupervised and supervised learning models to reduce dimensionality while focusing on morphological features that distinguish data with different biological labels [28]. This hybrid architecture effectively extracts discriminative morphological signatures without requiring prior anatomical knowledge, making it particularly valuable for large-scale phenotypic screening in drug discovery where manual annotation would be prohibitively time-consuming. By capturing nonlinear relationships in morphological data, Morpho-VAE can identify subtle phenotypic changes induced by genetic or chemical perturbations that might elude conventional analysis methods.

Technical Framework and Architecture

Core Components of Morpho-VAE

The Morpho-VAE architecture integrates two fundamental modules into a cohesive framework for morphological feature extraction:

VAE Module: The foundation employs a variational autoencoder consisting of an encoder that compresses high-dimensional input images into a low-dimensional latent representation (ζ), and a decoder that reconstructs the input from this compressed latent space. This component ensures that morphological information is preserved during the compression process through its reconstruction capability [28].

Classifier Module: A supervised classification component is interconnected with the VAE through the latent variables, guiding the encoder to extract features that are maximally discriminative between specified biological classes (e.g., cell types, treatment conditions, or species) [28].

The mathematical formulation of the Morpho-VAE training objective combines both unsupervised and supervised elements through a weighted total loss function: E_total = (1 - α)E_VAE + αE_C, where E_VAE represents the variational autoencoder loss (reconstruction + regularization), E_C denotes the classification loss, and α is a hyperparameter balancing these objectives. Through cross-validation on primate mandible image data, the optimal α value has been determined to be 0.1, successfully incorporating classification capability without significantly compromising reconstruction quality [28].

Comparative Advantage Over Traditional Methods

Table 1: Performance comparison of Morpho-VAE against traditional morphometric methods

| Method | Cluster Separation (CSI) | Landmark Requirement | Nonlinear Feature Capture | Handling of Missing Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morpho-VAE | 0.75 (Superior) | No | Excellent | Yes |

| Standard VAE | 1.12 (Moderate) | No | Good | Limited |

| PCA | 1.45 (Poor) | Yes | No | No |

| Landmark-Based GM | Varies | Yes | Limited | No |

The cluster separation index (CSI) quantifies the superiority of Morpho-VAE in distinguishing morphological classes, with lower values indicating better separation. Morpho-VAE achieves a CSI of 0.75, significantly outperforming standard VAE (1.12) and PCA-based approaches (1.45) [28]. This enhanced performance stems from its ability to capture nonlinear morphological relationships that linear methods like PCA cannot represent, while simultaneously focusing on biologically discriminative features through its integrated classifier.

Application Protocols for Phenotypic Profiling

Implementation Workflow for Cellular Morphological Analysis

The following Graphviz diagram illustrates the end-to-end Morpho-VAE workflow for phenotypic profiling:

Experimental Protocol: Morpho-VAE for Drug Response Profiling

Objective: To quantify morphological changes in cell lines in response to compound treatments using the Morpho-VAE framework.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell lines relevant to research focus (e.g., U2OS, A549)

- Cell culture media and supplements

- Compound libraries for screening

- Cell Painting staining reagents [29]:

- MitoTracker (Mitochondria staining)

- Phalloidin (Actin cytoskeleton)

- WGA (Golgi and plasma membrane)

- Concanavalin A (Endoplasmic reticulum)

- SYTO (Nuclear DNA)

- Fixation and permeabilization buffers

- High-content imaging compatible plates

Procedure:

Sample Preparation

- Seed cells in 96-well or 384-well imaging plates at appropriate density

- After cell attachment, treat with compounds at multiple concentrations

- Include DMSO controls and appropriate positive/negative controls

- Incubate for predetermined time (typically 24-48 hours)

- Fix cells and perform Cell Painting staining protocol [29]

Image Acquisition

- Acquire images using high-content microscope with 20x or 40x objective

- Capture 5 fluorescent channels corresponding to Cell Painting stains

- Acquire multiple fields per well to ensure adequate cell population sampling

- Save images in standard format (TIFF preferred) with appropriate metadata

Image Preprocessing

- Apply illumination correction to correct for uneven field illumination

- Perform background subtraction to remove camera noise

- Resize images to standard dimensions (e.g., 128×128 or 256×256 pixels)

- Apply data augmentation (rotation, flipping) to increase dataset diversity

Morpho-VAE Model Configuration

- Implement encoder network with convolutional layers (4-6 layers)

- Set latent dimension based on complexity (typically 3-50 dimensions)

- Implement decoder network with transposed convolutional layers

- Add classifier network with fully connected layers

- Configure hyperparameters: α=0.1, learning rate=0.001, batch size=32

Model Training

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets

- Train model for 100-500 epochs with early stopping

- Monitor both reconstruction and classification losses

- Validate cluster separation using quantitative metrics

Feature Extraction and Analysis

- Extract latent representations for all samples

- Apply dimensionality reduction (t-SNE, UMAP) for visualization

- Perform statistical analysis to identify significant morphological responses

- Correlate morphological profiles with treatment conditions

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Poor reconstruction quality may indicate insufficient model capacity or training time

- Inadequate cluster separation may require adjustment of the α parameter

- Overfitting to training classes can be addressed with increased regularization

- Computational requirements can be significant for large datasets; consider cloud resources

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for Morpho-VAE implementation

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function in Workflow | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Staining | Cell Painting Kit | Multiplexed morphological staining | Standardized 5-6 channel staining protocol [29] |

| Microscopy | High-content imagers (e.g., ImageXpress) | Automated image acquisition | Multi-channel, high-throughput capability |

| Image Analysis | CellProfiler [2] | Image preprocessing and feature extraction | Open-source, pipeline-based processing |