Beyond the Black Box: Strategies for Optimizing Machine Learning Interpretability in Bioinformatics

The exponential growth of complex biological data from high-throughput sequencing and multi-omics technologies has positioned machine learning (ML) as an indispensable tool in bioinformatics.

Beyond the Black Box: Strategies for Optimizing Machine Learning Interpretability in Bioinformatics

Abstract

The exponential growth of complex biological data from high-throughput sequencing and multi-omics technologies has positioned machine learning (ML) as an indispensable tool in bioinformatics. However, the 'black box' nature of many advanced models hinders their biological trustworthiness and clinical adoption. This article provides a comprehensive framework for optimizing ML model interpretability without sacrificing predictive performance. We explore the foundational principles of interpretable AI, detail methodological advances like pathway-guided architectures and SHAP analysis, address key troubleshooting challenges such as data sparsity and model complexity, and present rigorous validation paradigms. By synthesizing current research and practical applications, this review equips researchers and drug developers with the strategies needed to build transparent, actionable, and biologically insightful ML models that can reliably inform precision medicine and therapeutic discovery.

The Critical Need for Interpretability in Biological Machine Learning

FAQs on Interpretable Machine Learning

What is the difference between interpretability and explainability in machine learning?

Interpretability deals with understanding a model's internal mechanics—it shows how features, data, and algorithms interact to produce outcomes by making the model's structure and logic transparent. In contrast, Explainability focuses on justifying why a model made a specific prediction after the output has been generated, often using tools to translate complex relationships into human-understandable terms [1].

Why is model interpretability particularly important in bioinformatics research?

In computational biology, interpretability is crucial for verifying that a model's predictions reflect actual biological mechanisms rather than artifacts or biases in the data. It enables researchers to uncover critical sequence patterns, identify key biomarkers from gene expression data, and capture distinctive features in biomedical imaging, thereby transforming model predictions into actionable biological insights [2].

What are 'white-box' and 'black-box' models?

- White-box models (e.g., basic decision trees, linear regression) are inherently interpretable. Their internal logic is transparent and easy to trace, allowing users to follow the reasoning from input to output without guesswork.

- Black-box models (e.g., deep neural networks, complex ensemble methods) have internal workings that are too layered and complex to observe directly. Their decision paths are opaque, making it difficult even for experts to understand why a specific prediction was made [1].

I am using a complex deep learning model. How can I interpret it?

For complex models, you can use post-hoc explanation methods applied after the model is trained. These are often model-agnostic, meaning they can be used on any algorithm. Common techniques include:

- Feature importance methods like SHAP and LIME, which assign an importance value to each input feature based on its contribution to a prediction [2].

- Gradient-based methods like Integrated Gradients or GradCAM, which use gradients to determine feature importance [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent biological interpretations from my IML method.

- Potential Cause: Relying on a single Interpretable Machine Learning (IML) method. Different IML methods have different underlying assumptions and algorithms, and they can produce varying interpretations of the same prediction [2].

- Solution: Avoid using just one IML method. Apply multiple methods (e.g., both SHAP and LIME) to your model and compare the results. Consistent findings across multiple methods provide more robust and reliable biological interpretations [2].

Problem: My model performs well on training data but poorly on unseen test data.

- Potential Cause: Overfitting. The model has learned an overly complex mapping that captures noise specific to the training data, which does not generalize to new data [3].

- Solution:

- Apply Regularisation: Use techniques that penalize model complexity (e.g., L1 or L2 regularisation) during training to reduce overfitting [3].

- Use Cross-Validation: Partition your training data into subsets to estimate the model's performance on unseen data before final testing. This helps identify and rectify overfitting during the development phase [3].

Problem: My model's feature importance scores change drastically with small input changes.

- Potential Cause: Low stability in the IML method. Some popular explanation methods are known to be unstable, where small perturbations to the input lead to substantial variations in feature importance scores [2].

- Solution: Evaluate the stability of your IML methods. This metric measures the consistency of explanations for similar inputs. Consider choosing methods with higher demonstrated stability or use ensemble explanation techniques to produce more reliable interpretations [2].

Experimental Protocols for IML Evaluation

Protocol 1: Evaluating Explanation Faithfulness

Objective: To algorithmically assess whether the explanations generated by an IML method truly reflect the underlying model's reasoning (ground truth mechanisms) [2].

- Synthetic Data Generation: Create a dataset where the underlying logic or "ground truth" is known and controlled.

- Model Training: Train the model you wish to explain on this synthetic dataset.

- Explanation Generation: Apply the IML method (e.g., SHAP) to the trained model to get feature importance scores.

- Comparison: Compare the features identified as important by the IML method against the known ground truth features. A faithful method will correctly identify the ground truth features [2].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking IML Methods with Real Biological Data

Objective: To evaluate and compare different IML methods on real biological data where the ground truth is known from prior experimental validation.

- Dataset Selection: Identify a benchmark biological dataset (e.g., a gene expression dataset for a well-studied disease) where key biomarkers or mechanisms have been previously validated through experiments.

- Model Training & Prediction: Train a predictive model on this dataset.

- IML Application: Apply multiple IML methods to the trained model to get explanations (e.g., a ranked list of important genes).

- Validation: Check the extent to which each IML method's output recovers the known, validated biomarkers. The method that best recovers the established biology can be considered more reliable for that specific type of data and task [2].

Evaluation Metrics for IML

The table below summarizes key metrics for evaluating interpretability methods [2].

| Metric | Description | What It Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Faithfulness | Degree to which an explanation reflects the ground truth mechanisms of the ML model. | Whether the explanation accurately identifies the features the model actually uses for prediction. |

| Stability | Consistency of explanations for similar inputs. | How much the explanation changes when the input is slightly perturbed. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Method | Function in Interpretable ML |

|---|---|

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game theory-based method to assign each feature an importance value for a specific prediction, explaining the output of any ML model [2]. |

| LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) | Approximates a complex "black-box" model locally around a specific prediction with a simpler, interpretable model (e.g., linear regression) to explain individual predictions [2]. |

| Integrated Gradients | A gradient-based method that assigns importance to features by integrating the model's gradients along a path from a baseline input to the actual input [2]. |

| Interpretable By-Design Models | Models like linear regression or decision trees that are naturally interpretable due to their simple, transparent structure [2]. |

| Biologically-Informed Neural Networks | Model architectures (e.g., DCell, P-NET) that encode domain knowledge (e.g., gene hierarchies, biological pathways) directly into the neural network design, making interpretations biologically meaningful [2]. |

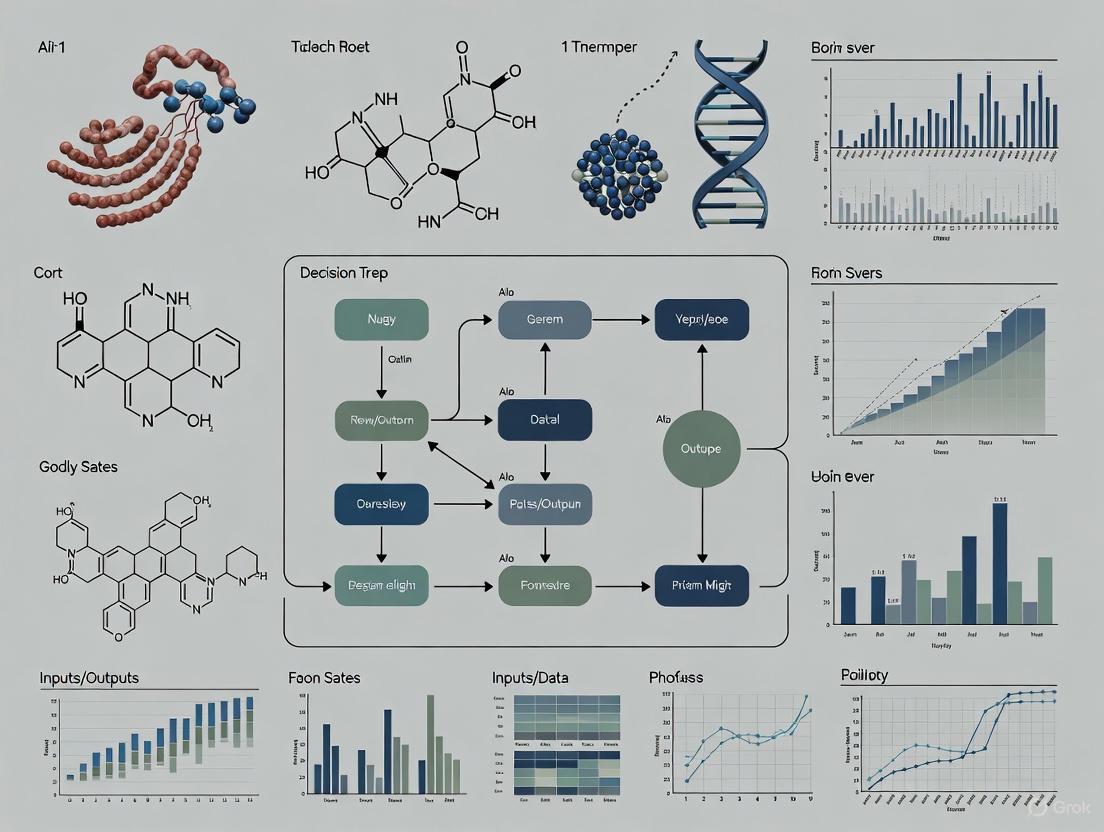

Workflow Visualization

Interpretable ML Workflow: A guide for selecting and evaluating interpretation methods.

Interpretability Approaches: Comparing by-design and post-hoc methods for biological insight.

The Crisis of Reproducibility and Trust in Omics Data Analysis

FAQs on Reproducibility and Machine Learning in Omics

What are the primary causes of the reproducibility crisis in omics research?

The reproducibility crisis is driven by a combination of systemic cultural pressures and technical data quality issues. Surveys of the biomedical research community indicate that over 70% of researchers have encountered irreproducible results, with more than 60% attributing this primarily to the "publish or perish" culture that prioritizes quantity of publications over quality and robustness of research [4]. Other significant factors include poor study design, insufficient methodological detail in publications, and a lack of training in reproducible research practices [5] [4].

Table: Key Factors Contributing to the Reproducibility Crisis

| Factor Category | Specific Issues | Reported Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural & Systemic | "Publish or perish" incentives [4] | Cited by 62% of researchers as a primary cause |

| Preference for novel findings over replication studies [4] | 67% feel their institution values new research over replication | |

| Statistical manipulation (e.g., p-hacking, HARKing) [5] | 43% of researchers admit to HARKing at least once | |

| Technical & Methodological | Inadequate data preprocessing and standardization [6] | Leads to incomparable results across studies |

| Poor documentation of protocols and reagents [5] | Makes experimental replication impossible | |

| Lack of version control and computational environment details [7] | Hinders computational reproducibility |

How can Interpretable Machine Learning (IML) help improve trust in omics data analysis?

Interpretable Machine Learning enhances trust by making model predictions transparent and biologically explainable. IML methods allow researchers to verify that a model's decision reflects actual biological mechanisms rather than technical artifacts or spurious correlations in the data [2]. This is crucial for justifying decisions derived from predictions, especially in clinical contexts [8]. IML approaches are broadly categorized into:

- Post-hoc explanations: Applied after model training to explain predictions (e.g., SHAP, LIME) by assigning importance values to input features like genes or genomic sequences [2].

- Interpretable by-design models: Models that are inherently interpretable, such as linear models, decision trees, or biologically-informed neural networks where hidden nodes correspond to biological entities like pathways or genes [2].

What are common pitfalls when applying IML to omics data and how can they be avoided?

A common pitfall is relying on a single IML method, as different techniques can produce conflicting interpretations of the same prediction [2]. To avoid this, use multiple IML methods and compare their outputs. Two other critical pitfalls are the failure to properly evaluate the quality of explanations and misinterpreting IML outputs as direct causal evidence [2].

Table: Troubleshooting Common IML Pitfalls in Omics

| Pitfall | Consequence | Solution & Best Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Using only one IML method | Unreliable, potentially misleading biological interpretations [2] | Apply multiple IML methods (e.g., both SHAP and LIME) to cross-validate findings [2]. |

| Ignoring explanation evaluation | Inability to distinguish robust explanations from unreliable ones [2] | Algorithmically assess explanations using metrics like faithfulness (does it reflect the model's logic?) and stability (is it consistent for similar inputs?) [2]. |

| Confusing correlation for causation | Incorrectly inferring biological mechanisms from feature importance [2] | Treat IML outputs as hypotheses-generating; validate key findings with independent experimental data [2]. |

What are the essential steps for data preprocessing to ensure reproducible multi-omics integration?

Reproducible multi-omics integration requires rigorous data standardization and harmonization. Key steps include [6]:

- Standardization: Collecting, processing, and storing data consistently using agreed-upon standards and protocols. This involves normalizing data to account for differences in sample size or concentration, converting to a common scale, and removing technical biases [6].

- Harmonization: Aligning data from different sources and technologies so they can be integrated. This typically involves mapping data onto a common genomic scale or reference and may use domain-specific ontologies [6].

- Documentation: Precisely describing all preprocessing and normalization techniques in the project documentation and associated articles. It is recommended to release both raw and preprocessed data in public repositories to ensure full transparency [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Irreproducible Machine Learning Models

Problem: An interpretable machine learning model yields different top feature importances when the analysis is repeated, leading to inconsistent biological insights.

Solution: Follow this structured workflow to identify and resolve the source of instability.

Steps:

- Verify Data Integrity and Preprocessing:

Assess Model and IML Method Stability:

- Avoid relying on a single IML method. Apply multiple techniques (e.g., both a gradient-based method like Integrated Gradients and a perturbation-based method like SHAP) and compare their results for consistency [2].

- For the chosen IML methods, evaluate their stability. This metric checks how consistent the explanations are for similar inputs. Many popular methods have been empirically shown to produce unstable results [2].

Implement Systematic Explanation Evaluation:

- Use algorithmic metrics to assess the quality of your IML outputs. The most common is faithfulness (or fidelity), which captures how well an explanation reflects the true reasoning of the underlying model [2].

- Compare IML outputs against known biological ground truth where available, to ensure the model is capturing real biology and not technical artifacts [2].

Ensure Complete Computational Reproducibility:

- Document the version of every tool, library, and IML package used [9].

- Use version control systems like Git for all analysis scripts and workflow management systems like Nextflow or Snakemake to capture the entire pipeline [7] [9]. This allows you and others to recreate the exact same analysis environment.

Guide 2: Debugging Multi-Omics Data Integration Pipelines

Problem: A multi-omics integration pipeline fails or produces different results upon re-running, or when used by a different researcher.

Solution: Methodically check the pipeline from data input to final output.

Steps:

- Verify Input Data and Metadata:

Check Tool Compatibility and Dependencies:

Isolate the Problem to a Specific Pipeline Stage:

Validate Final Outputs:

- Once the pipeline runs successfully, cross-check key results using an alternative method or a known dataset to ensure biological validity [7] [9].

- For multi-omics integration, confirm that the results make biological sense by checking if correlated features from different omics layers (e.g., genes, proteins) are part of established biological pathways [11].

Table: Key Resources for Reproducible Omics and IML Research

| Tool/Resource Category | Examples | Function & Importance for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow Management Systems | Nextflow, Snakemake, Galaxy [9] | Automates analysis pipelines, reduces manual intervention, and provides logs for debugging, ensuring consistent execution. |

| Data QC & Preprocessing Tools | FastQC, MultiQC, Trimmomatic [9] | Identifies issues in raw sequencing data (e.g., low-quality reads, contaminants) to prevent "garbage in, garbage out" [7]. |

| Version Control Systems | Git [7] [9] | Tracks changes to code and scripts, creating an audit trail and enabling collaboration and exact replication of analyses. |

| Interpretable ML (IML) Libraries | SHAP, LIME [2] | Provides post-hoc explanations for black-box models, helping to identify which features (e.g., genes) drove a prediction. |

| Biologically-Informed ML Models | DCell, P-NET, KPNN [2] | By-design IML models that incorporate prior knowledge (e.g., pathways, networks) into their architecture, making interpretations inherently biological. |

| Multi-Omics Integration Platforms | OmicsAnalyst, mixOmics, INTEGRATE [6] [11] | Statistical and visualization platforms for identifying correlated features and patterns across different omics data layers. |

| Standardized Antibodies & Reagents | Validated antibody libraries, cell line authentication services | Mitigates reagent-based irreproducibility, a major issue in preclinical research [5]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: How can I trust that the biological insights from my interpretable machine learning (IML) model are real and not artifacts of the data?

A primary challenge is ensuring that explanations from IML methods reflect true biology and not data noise or model artifacts [2].

- Root Cause: A common pitfall is relying on a single IML method. Different techniques (e.g., SHAP vs. LIME) are based on different assumptions and can produce conflicting interpretations for the same model prediction [2]. Furthermore, high-dimensional data is prone to spurious correlations, where features appear important by random chance rather than biological necessity [12].

- Solution Strategy:

- Use Multiple IML Methods: Consistently apply several IML techniques to your model. If multiple methods converge on the same set of important features, confidence in the biological insight increases [2].

- Evaluate Explanation Quality: Algorithmically assess the quality of your explanations using metrics like faithfulness (does the explanation reflect the model's true reasoning?) and stability (are explanations consistent for similar inputs?) [2].

- Incorporate Biological Ground Truth: Whenever possible, test your IML findings against known biological mechanisms or validate them with independent experimental data [2].

FAQ 2: My dataset has thousands of features (genes/proteins) but only dozens of samples. How does this "curse of dimensionality" affect my model, and how can I address it?

High-dimensional data spaces, where the number of features (p) far exceeds the number of samples (n), present unique challenges for analysis and interpretation [12].

- Root Cause: This "p >> n" scenario leads to the "curse of dimensionality." Key issues include [12] [13]:

- Model Overfitting: Models can become overly complex, learning noise from the training data rather than generalizable patterns, leading to poor performance on new data.

- Spurious Correlations and Clusters: The high number of features increases the probability of finding random, meaningless correlations that can be mistaken for true biological signal.

- Distance Concentration: In very high dimensions, the concept of "nearest neighbor" can break down, complicating clustering and other distance-based algorithms.

- Solution Strategy:

- Employ Robust Variable Selection: Move beyond simple one-at-a-time feature screening. Use methods that account for feature interactions, such as:

- Shrinkage Methods: Techniques like LASSO, ridge regression, or elastic net perform variable selection and regularization simultaneously to prevent overfitting [13].

- Bootstrap Confidence Intervals for Ranks: Use resampling to estimate confidence intervals for the rank importance of each feature, which honestly represents the uncertainty in the feature selection process [13].

- Ensure Proper Validation: Never validate a model's performance on the same data used for feature selection and training. Use rigorous resampling methods like cross-validation, ensuring that the entire feature selection process is repeated within each resample to get an unbiased performance estimate [13].

- Employ Robust Variable Selection: Move beyond simple one-at-a-time feature screening. Use methods that account for feature interactions, such as:

FAQ 3: My complex "black-box" model has high predictive accuracy, but I cannot understand how it makes decisions. What are my options for making it interpretable?

The tension between model complexity and interpretability is a central challenge in bioinformatics [14].

- Root Cause: Advanced models like deep neural networks and large ensembles (e.g., Random Forests) often achieve superior performance by learning highly complex, non-linear relationships. However, their internal workings are not transparent to human researchers [2] [14].

- Solution Strategy:

- Post-hoc Explanation Methods: Apply techniques to explain the model after it has been trained.

- SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): A unified framework that assigns each feature an importance value for a particular prediction based on game theory [2] [14].

- LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations): Approximates the complex model locally around a specific prediction with a simple, interpretable model (e.g., linear regression) to explain why that single decision was made [2] [14].

- Interpretable By-Design Models:

- Biologically-Informed Neural Networks: Design model architectures that encode existing domain knowledge. For example, structure the network so that hidden nodes correspond to known biological pathways (e.g., DCell, P-NET) [2]. This allows for direct interpretation of the importance of these pathways in the prediction.

- Attention Mechanisms: In sequence-based models (like transformers), attention weights can be inspected to see which parts of a DNA, RNA, or protein sequence the model "attends to" for making a prediction [2].

- Post-hoc Explanation Methods: Apply techniques to explain the model after it has been trained.

The table below compares common methods for handling high-dimensional data, highlighting their utility and limitations.

| Analytical Approach | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations / Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-at-a-Time (OaaT) Feature Screening | Tests each feature individually for association with the outcome [13]. | Simple to implement and understand. | Highly unreliable; produces unstable feature lists; ignores correlations between features; leads to overestimated effect sizes [13]. |

| Shrinkage/Joint Modeling | Models all features simultaneously with a penalty on coefficient sizes to prevent overfitting (e.g., LASSO, Ridge) [13]. | Accounts for feature interactions; produces more stable and generalizable models. | Model can be complex to tune; LASSO may be unstable in feature selection with correlated features [13]. |

| Data Reduction (e.g., PCA) | Reduces a large set of features to a few composite summary scores [13]. | Mitigates dimensionality; useful for visualization and noise reduction. | Resulting components can be difficult to interpret biologically [13]. |

| Random Forest | Builds an ensemble of decision trees from random subsets of data and features [13]. | Captures complex, non-linear relationships; provides built-in feature importance scores. | Can be a "black box"; prone to overfitting and poor calibration if not carefully tuned [13]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Framework for Robust IML in Bioinformatics

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for deriving and validating biological insights from complex models.

Objective: To identify key biomarkers and their functional roles in a specific phenotype (e.g., cancer prognosis) using a high-dimensional genomic dataset, while ensuring findings are robust and biologically relevant.

1. Pre-processing and Quality Control

- Data Validation: Before modeling, implement rigorous quality control (QC). For RNA-seq data, this involves using tools like FastQC to assess sequencing quality, alignment rates, and GC content [7].

- Combat Batch Effects: Use statistical methods to identify and correct for non-biological technical variation introduced by different processing batches [7].

2. Predictive Modeling with Interpretability in Mind

- Model Selection: Begin with a simpler, interpretable model (e.g., logistic regression with regularization). If performance is insufficient, move to a more complex model (e.g., XGBoost, neural network) [14].

- Training with Validation: Split data into training and testing sets. Use k-fold cross-validation on the training set to tune model hyperparameters. Hold the test set for final, unbiased evaluation [13].

3. Multi-Method Interpretation and Validation

- Apply Multiple IML Techniques: On the final trained model, apply at least two different post-hoc explanation methods (e.g., SHAP and Integrated Gradients) to get a consensus on important features [2].

- Functional Validation: The most critical step. Take the top candidate features (genes/proteins) identified by the IML analysis and validate them using independent experimental methods, such as:

- qPCR on selected genes from new samples.

- siRNA/gene knockout experiments to test the functional impact on the phenotype in cell cultures or animal models [12].

Workflow Visualization: From High-Dimensional Data to Biological Insight

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow and key decision points for tackling these challenges in a bioinformatics research pipeline.

Bioinformatics IML Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This table details key computational and experimental "reagents" essential for the experiments described in this guide.

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A unified game theory-based method to explain the output of any machine learning model, attributing the prediction to each input feature [2] [14]. |

| LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) | Fits a simple, local interpretable model around a single prediction to explain why that specific decision was made [2] [14]. |

| FastQC | A primary tool for quality control of high-throughput sequencing data; provides an overview of potential problems in the data [7]. |

| ComBat / sva R package | Statistical methods used to adjust for batch effects in high-throughput genomic experiments, improving data quality and comparability [7]. |

| siRNA / CRISPR-Cas9 | Experimental reagents for functional validation. They are used to knock down or knock out genes identified by the IML analysis to test their causal role in a phenotype [12]. |

| qPCR Assays | A highly sensitive and quantitative method used to validate changes in gene expression levels for candidate biomarkers discovered in the computational analysis [7]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Handling Poor Model Interpretability in High-Performance Black-Box Models

Problem: Your deep learning model achieves high predictive performance (e.g., ROC AUC = 0.944) but acts as a "black box," making it difficult to understand its decision-making process, which hinders clinical adoption [15] [16].

Diagnosis Steps:

- Verify performance metrics: Confirm the model's high performance on held-out test data.

- Attempt explanation generation: Apply post-hoc interpretation methods (e.g., LIME, SHAP) to key predictions.

- Identify explanation failure: Explanations are missing, unstable, or not clinically plausible.

Solution: Implement Model-Agnostic Interpretation Methods to explain individual predictions without sacrificing performance [17] [18].

- Recommended Method: Local Surrogate (LIME) or Shapley Values (SHAP).

LIME Workflow:

- Select a specific prediction to explain.

- Generate perturbed instances around this data point.

- Observe changes in the black-box model's predictions.

- Fit a simple, interpretable model (e.g., linear regression) to the perturbations and their resulting predictions.

- Use the coefficients of this local surrogate model to explain the original prediction [17].

SHAP Workflow:

- For a given prediction, calculate the Shapley value for each feature.

- This value represents the feature's marginal contribution, averaging over all possible feature combinations.

- The sum of all Shapley values plus the average prediction equals the actual model output, providing a consistent and locally accurate explanation [17].

Verification: You can now generate example-based explanations, such as: "This patient was predicted to have a prolonged stay primarily due to elevated blood urea nitrogen levels and low platelet count" [15].

Guide 2: Addressing Performance Loss When Using Simple, Interpretable Models

Problem: Your inherently interpretable model (e.g., linear regression or decision tree) provides clear reasoning but demonstrates unsatisfactory predictive performance (e.g., low ROC AUC), limiting its practical utility [19] [1].

Diagnosis Steps:

- Benchmark performance: Compare your model's performance against a complex baseline (e.g., neural network) on the same data.

- Analyze limitations: Simple models may fail to capture critical non-linear relationships or complex interactions in the data.

Solution: Employ a Hybrid or Advanced Interpretable Model that offers a better performance-interpretability balance [15] [20].

Option A: Data Fusion

- Combine structured data (e.g., lab results) with unstructured data (e.g., clinical notes).

- Vectorize text data using methods like Bio Clinical BERT.

- Train a model on the mixed dataset. This approach can significantly boost performance (e.g., ROC AUC from 0.944 to 0.963) while providing a richer scope of interpretable features from both data types [15].

Option B: Constrainable Neural Additive Models (CNAM)

- Use Neural Additive Models, which combine the performance of neural networks with the interpretability of Generalized Additive Models.

- CNAM learns a separate neural network for each feature, and the final output is a sum of these networks' contributions. This makes the effect of each feature easily visualizable [20].

Verification: Retrained model shows improved performance metrics (e.g., ROC AUC, Precision) while still allowing you to visualize and understand the contribution of key predictors.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between interpretability and explainability in machine learning?

A1: While often used interchangeably, a key distinction exists:

- Interpretability refers to the ability to understand the cause of a decision from a model's internal structure or mechanics. It's about mapping an abstract concept into a human-understandable form [21] [1]. It answers "how" the model works.

- Explainability often involves providing post-hoc justifications for a model's specific predictions or behaviors, requiring interpretability and additional context for a human audience. It answers "why" a specific decision was made [17] [21] [1].

Q2: Are there quantitative methods to compare the interpretability of different models?

A2: Yes, research is moving towards quantitative scores. One proposed metric is the Composite Interpretability (CI) Score. It combines expert assessments of simplicity, transparency, and explainability with a model's complexity (number of parameters). This allows for ranking models beyond a simple interpretable vs. black-box dichotomy [19].

Q3: My deep learning model for protein structure prediction is highly accurate. Why should I care about interpretability?

A3: In scientific fields like bioinformatics, interpretability is crucial for:

- Knowledge Discovery: The model itself becomes a source of knowledge. Interpreting it can reveal novel biological insights, such as unexpected features or relationships in the data [21] [22].

- Debugging and Bias Detection: Interpretability can uncover if a model has learned spurious correlations or biases from the training data, which is critical for ensuring the reliability and fairness of scientific findings [21] [1].

- Building Trust: For clinicians and researchers to adopt a model, they need to trust its outputs. Understanding the reasoning behind a prediction builds this trust and facilitates wider adoption [23] [22].

Q4: How can I quickly check if my model might be relying on biased features?

A4: Use Permuted Feature Importance [17]:

- Calculate your model's baseline error on a validation set.

- Shuffle the values of a single feature, breaking its relationship with the outcome.

- Recalculate the model's error with this shuffled feature.

- A large increase in error indicates the model heavily relies on that feature for its predictions. If the important features are sensitive attributes (e.g., race, gender), it signals potential bias that requires further investigation.

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Performance vs. Interpretability in Hospital Length of Stay Prediction

This table summarizes results from a study using the MIMIC-III database, comparing models trained on different data types. It demonstrates how data fusion can enhance both performance and interpretability [15].

| Data Type | Best Model | Performance (ROC AUC) | Performance (PRC AUC) | Key Interpretable Features Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structured Data Only | Ensemble Trees (AutoGluon) | 0.944 | 0.655 | Blood urea nitrogen level, platelet count [15] |

| Unstructured Text Only | Bio Clinical BERT | 0.842 | 0.375 | Specific procedures, medical conditions, patient history [15] |

| Mixed Data (Fusion) | Ensemble on Fused Data | 0.963 | 0.746 | Intestinal/colon pathologies, infectious diseases, respiratory problems, sedation/intubation procedures, vascular surgery [15] |

Table 2: Composite Interpretability (CI) Scores for Various Model Types

This table ranks different model types by a proposed quantitative interpretability score, which incorporates expert assessments of simplicity, transparency, explainability, and model complexity [19].

| Model Type | Simplicity | Transparency | Explainability | Num. of Params | CI Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VADER (Rule-based) | 1.45 | 1.60 | 1.55 | 0 | 0.20 |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | 1.55 | 1.70 | 1.55 | 3 | 0.22 |

| Naive Bayes (NB) | 2.30 | 2.55 | 2.60 | 15 | 0.35 |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 3.10 | 3.15 | 3.25 | ~20k | 0.45 |

| Neural Network (NN) | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.20 | ~68k | 0.57 |

| BERT (Fine-tuned) | 4.60 | 4.40 | 4.50 | ~184M | 1.00 |

Note: Lower CI score indicates higher interpretability. Scores for Simplicity, Transparency, and Explainability are average expert rankings (1=most interpretable, 5=least). Table adapted from [19].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Performance-Interpretability Trade-off Analysis

Objective: Systematically evaluate the trade-off between predictive performance and model interpretability using a real-world bioinformatics or clinical dataset [15] [19].

Materials:

- Dataset (e.g., MIMIC-III, Amazon product reviews, or a genomic dataset).

- Programming environment (e.g., Python with scikit-learn, AutoGluon, Hugging Face).

- Interpretation libraries (e.g., SHAP, LIME, Eli5).

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Perform standard cleaning: handle missing values, remove duplicates, normalize numerical features.

- For text data: remove stop words and punctuation; apply vectorization (CountVectorizer, TF-IDF) or use pre-trained embeddings (Word2Vec, Bio Clinical BERT) [15] [19].

- Define a binary classification target (e.g., Prolonged Length of Stay vs. Regular Stay) using a statistical cutoff like Tukey's upper fence [15].

Model Training and Benchmarking:

- Train a diverse set of models, from inherently interpretable to complex black boxes:

- Use k-fold cross-validation to ensure robust performance estimation [15].

Performance Evaluation:

- Calculate standard metrics for all models: Accuracy, ROC AUC, PRC AUC, F1-Score.

- Use a consistent test set for final comparison.

Interpretability Analysis:

- For interpretable models (LR, EBM), directly visualize coefficients or feature graphs.

- For black-box models (NN, BERT), apply post-hoc methods:

- Use SHAP to generate feature importance plots for global and local interpretability [17].

- Use LIME to create local surrogate explanations for specific instances [17].

- Use Partial Dependence Plots (PDP) or Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE) to understand the marginal effect of one or two features [17].

Synthesis and Trade-off Visualization:

Conceptual Diagrams

The Performance-Interpretability Trade-off

Model-Agnostic Interpretation with LIME

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Interpretable Machine Learning Research

This table lists key software tools and methods used in the field of interpretable ML, along with their primary function in a research workflow.

| Tool / Method | Type / Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SHAP (Shapley Values) [17] | Model-Agnostic, Post-hoc | Quantifies the marginal contribution of each feature to a single prediction, ensuring consistency and local accuracy. |

| LIME (Local Surrogate) [17] | Model-Agnostic, Post-hoc | Explains individual predictions by approximating the local decision boundary of any black-box model with an interpretable one. |

| Partial Dependence Plots (PDP) [17] | Model-Agnostic, Global | Visualizes the global average marginal effect of a feature on the model's prediction. |

| Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE) [17] | Model-Agnostic, Global/Local | Extends PDP by plotting the functional relationship for each instance, revealing heterogeneity in effects. |

| Explainable Boosting Machines (EBM) | Inherently Interpretable | A high-performance, interpretable model that uses modern GAMs with automatic interaction detection. |

| Neural Additive Models (NAM/CNAM) [20] | Inherently Interpretable | Combines the performance of neural networks with the interpretability of GAMs by learning a separate NN for each feature. |

| Permuted Feature Importance [17] | Model-Agnostic, Global | Measures the increase in a model's prediction error after shuffling a feature, indicating its global importance. |

| Global Surrogate [17] | Model-Agnostic, Post-hoc | Trains an interpretable model (e.g., decision tree) to approximate the predictions of a black-box model for global insight. |

| Bio Clinical BERT [15] | Pre-trained Model, Embedding | A domain-specific transformer model for generating contextual embeddings from clinical text, which can be used for prediction or interpretation. |

The Impact of Interpretable AI on Drug Discovery and Clinical Translation

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section provides practical, evidence-based guidance for resolving common challenges encountered when applying Interpretable AI (XAI) in bioinformatics and drug discovery research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My deep learning model for toxicity prediction is highly accurate but my pharmacology team does not trust its "black-box" nature. How can I make the model more interpretable for them?

A: This is a common translational challenge. To bridge this gap, implement post-hoc explainability techniques. Specifically, use SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) to generate local explanations for individual predictions [24]. These methods can highlight which molecular features or substructures (e.g., a specific chemical group) the model associates with toxicity [25]. Present these findings to your team alongside the chemical structures to facilitate validation based on their domain knowledge.

Q2: When I apply different XAI methods to the same protein-ligand binding prediction model, I get conflicting explanations. Which explanation should I trust?

A: This pitfall arises from the differing underlying assumptions of XAI methods [2]. Do not rely on a single XAI method. Instead, adopt a multi-method approach. Run several techniques (e.g., SHAP, Integrated Gradients, and DeepLIFT) and compare their outputs. Look for consensus in the identified important features. Furthermore, you must validate the explanations biologically. The most trustworthy explanation is one that aligns with known biological mechanisms or can be confirmed through subsequent laboratory experiments [2] [25].

Q3: The feature importance scores from my XAI model are unstable. Small changes in the input data lead to vastly different explanations. How can I improve stability?

A: Unstable explanations often indicate that the model is sensitive to noise or that the XAI method itself has high variance. To address this:

- Evaluate Stability Algorithmically: Use stability metrics to quantitatively assess the consistency of explanations for similar inputs [2].

- Improve Data Quality: Ensure your training data is high-quality and representative. Data augmentation techniques may help [26].

- Regularize Your Model: Apply regularization during model training to reduce over-sensitivity to minor input variations.

- Consider Interpretable-by-Design Models: For critical applications, consider using models that are inherently interpretable, such as decision trees or rule-based systems, which can provide more stable explanations [24].

Q4: We are preparing an AI-based biomarker discovery tool for regulatory submission. What are the key XAI-related considerations?

A: Regulatory bodies like the FDA emphasize transparency. Your submission should demonstrate:

- Model Interpretability: Use XAI to provide clear, human-understandable reasons for the model's predictions [27] [25].

- Biological Plausibility: Link the model's explanations and identified biomarkers to established or hypothesized disease pathways [25].

- Bias Mitigation: Use XAI to audit your model for spurious correlations and ensure it performs equitably across different populations [27]. Proactively engaging with regulators to align your XAI approach with evolving guidelines is highly recommended [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common XAI Errors and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Interpretation | Inconsistent feature attributions across different XAI tools. | Different XAI methods have varying underlying assumptions and algorithms [2]. | Apply multiple XAI methods (e.g., SHAP, LIME, Integrated Gradients) and seek a consensus. Biologically validate the consensus features [2]. |

| Model Interpretation | Generated explanations are not trusted or understood by domain experts. | Explanations are too technical or not linked to domain knowledge (e.g., chemistry, biology) [28]. | Use visualization tools to map explanations onto tangible objects (e.g., molecular structures). Foster collaboration between AI and domain experts from the project's start [24]. |

| Data & Evaluation | Explanations are unstable to minor input perturbations. | The model is overly sensitive to noise, or the XAI method itself is unstable [2]. | Perform stability testing of explanations. Use regularization and data augmentation to improve model robustness [26] [2]. |

| Data & Evaluation | Difficulty in objectively evaluating the quality of an explanation. | Lack of ground truth for model reasoning in real-world biological data [2]. | Use synthetic datasets with known logic for initial validation. In real data, use downstream experimental validation as the ultimate test [2]. |

| Implementation & Workflow | High computational cost of XAI methods slowing down the research cycle. | Some XAI techniques, like perturbation-based methods, are computationally intensive [24]. | Start with faster, model-specific methods (e.g., gradient-based). Leverage cloud computing platforms (AWS, Google Cloud) for scalable resources [24]. |

| Implementation & Workflow | Difficulty integrating XAI into existing bioinformatics pipelines. | Lack of standardization and compatibility with workflow management systems (e.g., Nextflow, Snakemake) [9]. | Use open-source XAI frameworks (SHAP, LIME) that offer API integrations. Modularize the XAI component within the pipeline for easier management [9]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the literature, ensuring reproducibility and providing a framework for your own research.

Protocol 1: Validating AI-Driven Toxicity Predictions Using XAI

Objective: To experimentally verify the molecular features identified by an XAI model as being responsible for predicted hepatotoxicity.

Background: AI models can predict compound toxicity, but XAI tools like SHAP can pinpoint the specific chemical substructures driving that prediction [26] [24]. This protocol outlines how to validate these computational insights.

Materials:

- Compound Library: Include the compound flagged for toxicity and structural analogs.

- In Vitro Assay: Hepatocyte cell culture (e.g., HepG2 cells) and a cytotoxicity assay (e.g., MTT or LDH assay).

- Analytical Chemistry: Equipment for metabolic profiling (e.g., LC-MS).

Methodology:

- In Silico Prediction & Explanation:

- Input your compound into the trained toxicity prediction model.

- Use SHAP or LIME to generate a feature importance plot. The output will highlight specific molecular substructures (e.g., a methylenedioxyphenyl group) suspected of causing toxicity [24].

- Compound Design & Synthesis:

- Based on the XAI output, design and synthesize a series of analogs:

- Analog A: Remove or alter the suspect substructure.

- Analog B: Modify the suspect substructure.

- Analog C: Retain the suspect substructure but alter a part of the molecule deemed unimportant by the XAI model.

- Based on the XAI output, design and synthesize a series of analogs:

- Experimental Validation:

- Treat hepatocyte cells with the original compound and each analog.

- Measure cell viability and markers of liver damage (e.g., ALT, AST release).

- Expected Outcome: If the XAI explanation is correct, Analog A and B should show reduced toxicity, while Analog C should remain toxic. This confirms the XAI-identified substructure is a key mediator of the toxic effect [25].

Protocol 2: Using XAI for Patient Stratification in Clinical Trial Design

Objective: To use an XAI model to identify key biomarkers for patient stratification and explain the rationale behind the stratification to ensure clinical relevance.

Background: XAI can optimize clinical trials by identifying which patients are most likely to respond to a treatment. The "explanation" is critical for understanding the biological rationale [24].

Materials:

- Dataset: High-dimensional patient data (e.g., transcriptomic, proteomic, or genetic data) with associated treatment response outcomes.

- Software: ML model (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) and XAI library (e.g., SHAP).

Methodology:

- Model Training:

- Train a classifier to predict treatment response (Responder vs. Non-Responder) using the patient data.

- Global Explanation with SHAP:

- Calculate the SHAP summary plot. This will show which biomarkers (e.g., gene expression levels) are most important for the model's prediction across the entire dataset [24].

- Stratification Rule Development:

- Analyze the SHAP plots to create actionable inclusion/exclusion criteria. For example, the model might indicate that high expression of

Gene Aand low expression ofGene Bare predictive of response.

- Analyze the SHAP plots to create actionable inclusion/exclusion criteria. For example, the model might indicate that high expression of

- Biological Validation & Trial Design:

- Collaborate with clinical scientists to assess if the XAI-identified biomarkers make biological sense for the disease and drug mechanism.

- Use this validated biomarker signature to define the patient population for the prospective clinical trial. The XAI output provides a transparent, evidence-based rationale for the trial design, which is valuable for regulatory approval [25].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz, illustrate key signaling pathways, experimental workflows, and logical relationships in interpretable AI for drug discovery.

XAI Model Interpretation Workflow

AI & XAI in the Drug Discovery Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key software tools and resources essential for implementing and experimenting with Interpretable AI in drug discovery.

Key XAI Software Tools & Frameworks

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Key Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Unified framework for explaining model predictions using game theory [2] [24]. | Explains the output of any ML model. Used to quantify the contribution of each feature (e.g., a molecular descriptor) to a prediction, such as a compound's binding affinity or toxicity [24] [25]. |

| LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) | Creates local, interpretable approximations of a complex model around a specific prediction [2] [24]. | Explains "why" a single compound was classified in a certain way by perturbing its input and observing changes in the prediction, providing intuitive, local insights [24]. |

| Integrated Gradients | An attribution method for deep networks that calculates the integral of gradients along a path from a baseline to the input [2]. | Used to interpret deep learning models in tasks like protein-ligand interaction prediction, attributing the prediction to specific features in the input data [2]. |

| DeepLIFT (Deep Learning Important FeaTures) | Method for decomposing the output prediction of a neural network on a specific input by backpropagating the contributions of all neurons [24]. | Similar to Integrated Gradients, it assigns contribution scores to each input feature, useful for interpreting deep learning models in genomics and chemoinformatics [24]. |

| Anchor | A model-agnostic system that produces "if-then" rule-based explanations for complex models [2]. | Provides high-precision, human-readable rules for predictions (e.g., "IF compound has functional group X, THEN it is predicted to be toxic"), which are easily validated by chemists [2]. |

Architectures and Techniques for Transparent Bioinformatics Models

Pathway-Guided Interpretable Deep Learning Architectures (PGI-DLA)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core advantage of using a PGI-DLA over a standard deep learning model for omics data analysis? PGI-DLAs directly integrate established biological pathway knowledge (e.g., from KEGG, Reactome) into the neural network's architecture. This moves the model from a "black box" to a "glass box" by ensuring its internal structure mirrors known biological hierarchies and interactions. The primary advantage is intrinsic interpretability; because the model's hidden layers represent real biological entities like pathways or genes, you can directly trace which specific biological modules contributed most to a prediction, thereby aligning the model's decision-making logic with domain knowledge [29] [30].

FAQ 2: My model has high predictive accuracy, but the pathway importance scores seem unstable between similar samples. What could be wrong? This is a common pitfall related to the stability of interpretability methods. High predictive performance does not guarantee robust explanations. We recommend:

- Method Audit: Apply multiple interpretation methods (e.g., SHAP, DeepLIFT, Integrated Gradients) to the same model and data to see if the instability is consistent across techniques [2].

- Faithfulness Check: Evaluate if your explanations faithfully reflect the model's true reasoning. Use synthetic data where the ground truth is known, or test on real biological data with well-established mechanisms to validate that your IML method recovers expected signals [2].

- Data Consistency: Ensure that data preprocessing and normalization steps are consistent and appropriate for your omics data type, as technical variations can disproportionately affect importance scores [8].

FAQ 3: How do I choose the right pathway database for my PGI-DLA project? The choice of database fundamentally shapes model design and the biological questions you can answer. You should select a database whose scope and structure align with your research goals. The table below compares the most commonly used databases in PGI-DLA.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Pathway Databases for PGI-DLA Implementation

| Database | Knowledge Scope & Curative Focus | Hierarchical Structure | Ideal Use Cases in PGI-DLA |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG | Well-defined metabolic, signaling, and cellular processes [29] | Focused on pathway-level maps | Modeling metabolic reprogramming, signaling cascades in cancer [29] |

| Gene Ontology (GO) | Broad functional terms across Biological Process, Cellular Component, Molecular Function [29] | Deep, directed acyclic graph (DAG) | Exploring hierarchical functional enrichment, capturing broad cellular state changes [29] |

| Reactome | Detailed, fine-grained biochemical reactions and pathways [29] | Hierarchical with detailed reaction steps | High-resolution models requiring mechanistic, step-by-step biological insight [29] |

| MSigDB | Large, diverse collection of gene sets, including hallmark pathways and curated gene signatures [29] | Collections of gene sets without inherent hierarchy | Screening a wide range of biological states or leveraging specific transcriptional signatures [29] |

FAQ 4: What are the main architectural paradigms for building a PGI-DLA? There are three primary architectural designs, each with different interpretable outputs:

- Sparse Deep Neural Networks (DNNs): The network architecture is a sparse version of a standard fully-connected network, where connections are pruned based on pathway knowledge. A gene is only connected to pathways it belongs to, and a pathway is only connected to higher-level functions it participates in [29]. Interpretability is often intrinsic, as the activity of a hidden node representing a pathway can be directly used as its importance score.

- Variable Neural Networks (VNNs): In this architecture, the nodes and connections of the neural network are explicitly defined by prior knowledge graphs. Each node (e.g., a gene) has its own dedicated subnetwork. This allows for tracing information flow through the entire network, as seen in foundational models like DCell [29] [2].

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): The pathway knowledge is structured as a graph, where entities (proteins, metabolites) are nodes and their interactions are edges. The GNN then learns from this graph structure, making it highly suited for capturing complex relational data. Interpretability can be intrinsic from the graph structure or obtained via post-hoc methods like GNNExplainer [29].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and architectural choices for implementing a PGI-DLA project.

PGI-DLA Implementation Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Model Performance is Poor Despite High-Quality Data

Problem: Your PGI-DLA model fails to achieve satisfactory predictive performance (e.g., low AUROC/AUPRC) during validation, even with well-curated input data.

Investigation & Resolution Protocol:

Diagnostic Step: Pathway Knowledge Audit.

- Action: Systematically check if the integrated pathway knowledge is relevant to the phenotype you are predicting.

- Solution: Perform a standard enrichment analysis (e.g., GSEA) on your input features against the same pathway database. If no significant enrichment is found, the pathways may not be informative for your specific task. Consider switching to a more specialized database or a different architectural approach that is less reliant on strong prior knowledge [29] [8].

Diagnostic Step: Architecture-Specific Parameter Tuning.

- Action: The constraints imposed by pathway knowledge can sometimes lead to underfitting if the model complexity is too low.

- Solution: For Sparse DNNs, investigate if adding a limited number of "cross-pathway" connections improves performance without severely compromising interpretability. For VNNs and GNNs, experiment with the dimensionality of the node embeddings and the depth (number of layers) of the network to enhance its learning capacity [29] [2].

Diagnostic Step: Input Representation.

- Action: Verify that the omics data is correctly mapped and normalized for the model.

- Solution: Ensure each gene's expression or variant data is correctly linked to its corresponding node in the network. Experiment with different data transformations (e.g., log-CPM for RNA-seq, z-scores) to find the representation that best aligns with your model's architecture and activation functions [29].

Issue: Biological Interpretations are Counterintuitive or Lack Novelty

Problem: The model identifies pathways of high importance that are already well-known (e.g., "E2F Targets" in cancer) or seem biologically implausible for the studied condition.

Investigation & Resolution Protocol:

Diagnostic Step: Pitfall of a Single IML Method.

- Action: Different interpretation methods can yield different results based on their underlying algorithms and assumptions.

- Solution: Do not rely on a single method. Apply at least two different post-hoc explanation techniques (e.g., SHAP and Integrated Gradients) to your trained model. Compare the resulting feature and pathway importance rankings. Consistent findings across methods are more reliable and warrant higher confidence [2].

Diagnostic Step: Evaluation of Explanation Quality.

- Action: Algorithmically assess the quality of your explanations.

- Solution: Perform a stability analysis by introducing small perturbations to your input data and observing the variance in the resulting explanations. Stable explanations across similar inputs are more trustworthy. Furthermore, evaluate faithfulness by measuring how much the prediction changes when you ablate the most important features identified by the IML method; a faithful explanation should correspond to a large prediction change [2].

Diagnostic Step: Validation with External Knowledge.

- Action: Contextualize your findings beyond the immediate model output.

- Solution: Corroborate your model's top predictions with independent data sources or literature. Use the model's findings as a prioritization tool to generate new, testable hypotheses for experimental validation. The goal is not just to explain the model, but to use the model to discover new biology [2] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools & Resources for PGI-DLA

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in PGI-DLA | Key Reference/Resource |

|---|---|---|---|

| InterpretML | Software Library | Provides a unified framework for training interpretable "glassbox" models (e.g., Explainable Boosting Machines) and explaining black-box models using various post-hoc methods like SHAP and LIME. Useful for baseline comparisons [31]. | InterpretML GitHub [31] |

| KEGG PATHWAY | Pathway Database | Blueprint for architectures focusing on metabolic and signaling pathways. Provides a structured, map-based hierarchy [29]. | Kanehisa & Goto, 2000 [29] |

| Reactome | Pathway Database | Detailed, hierarchical database of human biological pathways. Ideal for building high-resolution, mechanistically grounded models [29]. | Jassal et al., 2020 [29] |

| MSigDB | Gene Set Database | A large collection of annotated gene sets. The "Hallmark" gene sets are particularly useful for summarizing specific biological states [29]. | Liberzon et al., 2015 [29] |

| SHAP | Post-hoc Explanation Algorithm | A game theory-based method to compute consistent feature importance scores for any model. Commonly applied to explain complex PGI-DLA predictions [29] [2]. | Lundberg & Lee, 2017 [2] |

| Integrated Gradients | Post-hoc Explanation Algorithm | An axiomatic attribution method for deep networks that is particularly effective for genomics data, as it handles the baseline state well [29] [2]. | Sundararajan et al., 2017 [2] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Benchmarking PGI-DLA Model Performance and Interpretability

Objective: To systematically evaluate and compare the predictive performance and biological interpretability of a newly designed PGI-DLA against established baseline models.

Materials:

- Curated multi-omics dataset with associated phenotypic labels (e.g., disease vs. healthy).

- Pathway knowledge graph (from KEGG, Reactome, etc.).

- Computational environment with necessary deep learning libraries (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow).

Methodology:

Data Splitting and Preprocessing:

- Partition the data into training, validation, and held-out test sets using a stratified split to maintain label distribution.

- Apply standard normalization (e.g., z-score) to the omics data based on statistics from the training set only to prevent data leakage.

Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning:

- Train the following models:

- Baseline 1: Standard Black-Box DNN (e.g., a fully-connected multilayer perceptron).

- Baseline 2: Interpretable Glassbox Model (e.g., Explainable Boosting Machine from InterpretML) [31].

- Test Model: Your proposed PGI-DLA (e.g., a Sparse DNN or GNN).

- Optimize hyperparameters for each model using the validation set and a defined search strategy (e.g., grid or random search). Key metrics for optimization should be task-specific (e.g., AUROC for classification, C-index for survival).

- Train the following models:

Performance Evaluation on Held-Out Test Set:

- Calculate final performance metrics on the untouched test set. Record the following for each model:

- Primary Metric: e.g., AUROC, Accuracy, F1-Score.

- Secondary Metric: e.g., Precision-Recall AUROC (for imbalanced data).

Table 3: Example Benchmarking Results for a Classification Task

Model Type AUROC (±STD) Accuracy (±STD) Interpretability Level Black-Box DNN 0.927 ± 0.001 0.861 ± 0.005 Low (Post-hoc only) Explainable Boosting Machine 0.928 ± 0.002 0.859 ± 0.003 High (Glassbox) PGI-DLA (Proposed) 0.945 ± 0.003 0.878 ± 0.004 High (Intrinsic) Note: Example values are for illustration and based on realistic performance from published studies [29] [31].

- Calculate final performance metrics on the untouched test set. Record the following for each model:

Interpretability and Biological Validation:

- For the black-box DNN and the PGI-DLA, apply post-hoc explanation methods (e.g., SHAP, Integrated Gradients) to derive feature/gene-level importance scores.

- For the PGI-DLA, also extract intrinsic interpretations, such as node activities from pathway layers.

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., using GSEA) on the top genes identified by each model. Compare the resulting enriched pathways against known biology from literature. A superior model should recover established mechanisms and potentially suggest novel, plausible ones [29] [2] [8].

FAQ: Knowledge Base Selection and Access

FAQ 1: What are the key differences between major biological knowledge bases, and how do I choose the right one for my analysis?

Your choice of knowledge base should be guided by your specific biological question and the type of analysis you intend to perform. The table below summarizes the core focus of each major resource.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Biological Knowledge Bases

| Knowledge Base | Primary Focus & Content | Key Application in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Ontology (GO) | A species-agnostic vocabulary structured as a graph, describing gene products via:• Molecular Function (MF)• Biological Process (BP)• Cellular Component (CC) [32] | Identifying over-represented biological functions or processes in a gene list (e.g., using ORA) [32] [33]. |

| KEGG Pathway | A collection of manually drawn pathway maps representing molecular interaction and reaction networks, notably for metabolism and cellular processes [32]. | Pathway enrichment analysis and visualization of expression data in the context of known pathways [34]. |

| Reactome | A curated, peer-reviewed database of human biological pathways and reactions. Reactions include events like binding, translocation, and degradation [35] [36]. | Detailed pathway analysis, visualization, and systems biology modeling. Provides inferred orthologs for other species [36]. |

| MSigDB | A large, annotated collection of gene sets curated from various sources. It is divided into themed collections (e.g., Hallmark, C2 curated, C5 GO) for human and mouse [37] [38]. | Primarily used as the gene set source for Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to interpret genome-wide expression data [32] [37]. |

FAQ 2: I have a list of differentially expressed genes. What is the most straightforward method to find enriched biological functions?

Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) is the most common and straightforward method. It statistically evaluates whether genes from a specific pathway or GO term appear more frequently in your differentially expressed gene list than expected by chance. Common statistical tests include Fisher's exact test or a hypergeometric test [32] [34]. Tools like clusterProfiler provide a user-friendly interface for this type of analysis and can retrieve the latest annotations for thousands of species [33].

FAQ 3: My ORA results show hundreds of significant GO terms, many of which are redundant. How can I simplify this for interpretation?

You can reduce redundancy by using GO Slim, which is a simplified, high-level subset of GO terms that provides a broad functional summary [32]. Alternatively, tools like REVIGO or GOSemSim can cluster semantically similar GO terms, making the results more manageable and interpretable [32] [33].

FAQ 4: What should I do if my gene identifiers are not recognized by the analysis tool?

Gene identifier mismatch is a common issue. Most functional analysis tools require annotated genes, and not all identifier types are compatible [32].

- Solution: Always use official gene symbols from the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) or stable identifiers like those from Ensembl or Entrez Gene. Before analysis, use a reliable ID conversion tool (often available within analysis platforms like Omics Playground) to map your identifiers to the type required by your chosen knowledge base [32] [34].

Troubleshooting Common Analysis Problems

Problem 1: Inconsistent or Non-Reproducible IML Explanations in Integrated Models

Scenario: A researcher uses SHAP to explain a deep learning model that integrates gene expression with pathway knowledge from Reactome. The feature importance scores vary significantly with small input perturbations, leading to unstable biological interpretations.

Solution:

- Do not rely on a single IML method. Different IML methods (e.g., SHAP, LIME, Integrated Gradients) have different underlying assumptions and can produce varying interpretations for the same prediction. Always compare results across multiple methods to identify robust signals [2].

- Evaluate for stability. Check the consistency of explanations for similar inputs. An explanation is only useful if it is stable under minor, biologically reasonable perturbations to the input data [2].

- Validate against known biology. When possible, test your IML method on a biological system where the ground truth mechanism is at least partially known. This helps verify that the explanations reflect real biology and not an artifact of the model [2].

Problem 2: GSEA Yields No Significant Results Despite Strong Differential Expression

Scenario: A scientist runs GSEA on a strongly upregulated gene list but finds no enriched Hallmark gene sets in the MSigDB, even though the biology is well-established.

Solution:

- Verify your ranked list. GSEA does not use a pre-selected gene list. It requires a full ranked list of all genes measured, typically sorted by a metric like the signal-to-noise ratio or t-statistic from your differential expression analysis. Ensure you are providing the correct input [32] [34].

- Check the gene set collection. The MSigDB contains many collections. The absence of a result in the Hallmark collection does not mean no pathways are enriched. Rerun the analysis using broader collections like C2 (curated gene sets) or C5 (GO terms) [32] [38].

- Adjust permutation type. GSEA uses permutations to assess significance. For RNA-seq data with a small sample size (e.g., n < 7), use gene_set permutation instead of the default phenotype permutation to avoid inflated false-positive rates [37].

Problem 3: High Background Noise in Functional Enrichment of Genomic Regions

Scenario: A bioinformatician performs enrichment analysis on ChIP-seq peaks but gets many non-specific results related to basic cellular functions, obscuring the specific biology.

Solution:

- Use an appropriate background. The background set for ORA should reflect all possible genes or regions that could have been detected in your experiment. Using all genes in the genome is often inappropriate. Instead, use the set of all genes expressed in your experiment (for RNA-seq) or all genes associated with peaks in your input/control sample (for ChIP-seq) [32].

- Leverage specialized tools. Use tools designed for functional interpretation of cistromic data, such as ChIPseeker. These tools are integrated with public repositories like GEO, allowing for better annotation, comparison, and mining of epigenomic data [33].

Experimental Protocols for Integration with Machine Learning

Protocol 1: Building a Biologically-Informed Neural Network using Pathway Topology

This protocol uses pathway structure from Reactome or KEGG to constrain a neural network, enhancing its interpretability.

- Objective: To predict a clinical phenotype (e.g., drug response) from gene expression data using a model where hidden layers correspond to biological pathways.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Gene Expression Matrix: Normalized count matrix (e.g., TPM or FPKM) for your samples.

- Pathway Topology: Pathway information in a standard format (e.g., SBML, BioPAX) from Reactome or KEGG.

- P-NET or KPNN Framework: Implementations of biologically-informed neural networks [2].

- Research Reagent Solutions:

Methodology:

- Network Construction: Define the neural network architecture so that each node in the first hidden layer represents a single gene, and each node in the subsequent hidden layer represents a biological pathway. The connections between the "gene layer" and the "pathway layer" are not fully connected; they are defined and fixed based on the known gene-pathway membership from your chosen knowledge base [2].

- Model Training: Train the network using your gene expression data and corresponding phenotype labels. The model learns weights for the connections between pathways and the output.

- Interpretation: Analyze the learned weights on the connections from the pathway layer to the output node. Pathways with high absolute weight values are interpreted as being important for predicting the phenotype. This provides a direct, model-intrinsic explanation [2].

The following diagram illustrates the architecture of such a biologically-informed neural network.

Diagram 1: Biologically-informed neural network architecture.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking IML Methods for Pathway Enrichment Insights

This protocol provides a framework for systematically evaluating different IML explanation methods when applied to models using knowledge bases.

- Objective: To assess the faithfulness and stability of post-hoc IML explanations (e.g., SHAP, Integrated Gradients) for a model trained on gene expression data annotated with GO terms.

Materials:

- Trained Model: A black-box model (e.g., a random forest or deep learning model) for phenotype prediction.

- IML Tools: SHAP, LIME, or Integrated Gradients implementations.

- Benchmarking Dataset: A dataset where some "ground truth" pathways are known to be associated with the phenotype.

Methodology:

- Explanation Generation: Apply multiple IML methods to your trained model to generate feature importance scores for each input feature (gene) across a set of test samples.

- Pathway-Level Aggregation: Aggregate gene-level importance scores to the pathway level. For example, calculate the mean absolute SHAP value for all genes belonging to a specific GO biological process or Reactome pathway.

- Faithfulness Evaluation:

- Procedure: Systematically remove or perturb top features identified as important by the IML method and observe the drop in the model's predictive performance. A faithful explanation should identify features whose removal causes a significant performance decrease [2].

- Metric: Measure the correlation between the importance score of a feature set and the model's performance drop when that set is ablated.

- Stability Evaluation:

- Procedure: Introduce small, random noise to the input data and re-run the IML explanation generation. Compare the new explanations to the original ones.

- Metric: Calculate the rank correlation (e.g., Spearman correlation) between the original and perturbed feature importance rankings. A high correlation indicates a stable explanation [2].

The workflow for this benchmarking protocol is outlined below.

Diagram 2: IML method benchmarking workflow.

Model-Agnostic Interpretation with SHAP and LIME

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My SHAP analysis is extremely slow on my large bioinformatics dataset. How can I improve its computational efficiency?

SHAP's computational demand, especially with KernelExplainer, scales with dataset size and model complexity [39]. For large datasets like gene expression matrices, use shap.TreeExplainer for tree-based models (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) or shap.GradientExplainer for deep learning models, as they are optimized for specific model architectures [40] [41]. Alternatively, calculate SHAP values on a representative subset of your data or leverage background data summarization techniques (e.g., using shap.kmeans) to reduce the number of background instances against which comparisons are made [39].

Q2: The explanations I get from LIME seem to change every time I run it. Is this normal, and how can I get more stable results?

Yes, LIME's instability is a known limitation due to its reliance on random sampling for generating local perturbations [42] [2]. To enhance stability:

- Increase the sample size: Use the

num_samplesparameter in theexplain_instancemethod. A higher number of perturbed samples leads to a more stable local model but increases computation time [39]. - Set a random seed: Ensure reproducibility by fixing the random seed in your code (e.g.,

np.random.seed(42)) [39]. - Tune the kernel width: The kernel width parameter controls how the proximity of perturbed samples is weighted. This can significantly impact the explanation [43].

Q3: For my high-stakes application in drug response prediction, should I trust LIME or SHAP more?

While both are valuable, SHAP is often preferred for high-stakes scenarios due to its strong theoretical foundation in game theory, which provides consistent and reproducible results [42] [39]. SHAP satisfies desirable properties like efficiency (the sum of all feature contributions equals the model's output), making its explanations reliable [41]. LIME, while highly intuitive, can be sensitive to its parameters and provides only a local approximation [43]. For critical applications, it is a best practice to use multiple IML methods and validate the biological plausibility of the explanations against known mechanisms [2].

Q4: How can I validate that my SHAP or LIME explanations are biologically meaningful and not just model artifacts?

This is a crucial step often overlooked. Several strategies exist:

- Literature Validation: Compare the top features identified by SHAP/LIME with known biomarkers or biological pathways from scientific literature [2].

- Ablation Studies: Experimentally "ablate" or remove top-ranked features from your model input and observe if the model's predictive performance drops significantly.