Benchmarking Drug-Target Interaction Prediction: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape of drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction benchmarking.

Benchmarking Drug-Target Interaction Prediction: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape of drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction benchmarking. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational concepts, critically evaluates state-of-the-art methodologies from traditional chemogenomics to modern graph neural networks and Transformers, and addresses key challenges like dataset bias and model generalization. The content further offers strategic insights for troubleshooting and optimization, establishes a robust framework for model validation and comparison, and synthesizes findings to outline future directions that promise to enhance the accuracy, efficiency, and clinical applicability of DTI prediction models in accelerating drug discovery.

The Foundations of DTI Prediction: From Problem Definition to Benchmarking Necessity

Defining the Drug-Target Interaction Prediction Problem and Its Impact on Drug Discovery

Drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction is a cornerstone of computational drug discovery, enabling the rational design of new therapeutics, the repurposing of existing drugs, and the elucidation of their mechanisms of action [1]. The core problem involves predicting whether a given drug molecule will interact with a specific target protein, a task traditionally addressed through expensive, time-consuming, low-throughput experimental screening [2]. The computational challenge stems from the vast search space; with over 108 million compounds in PubChem and an estimated 200,000 human proteins, experimentally testing all possible pairs is practically impossible [2]. DTI prediction methods aim to computationally prioritize the most promising drug-target pairs for subsequent experimental validation, thereby dramatically accelerating discovery pipelines and reducing associated costs [1].

Comparative Analysis of DTI Prediction Methodologies

Modern DTI prediction methods have evolved from traditional similarity-based and docking simulations to sophisticated deep learning approaches. The table below provides a high-level comparison of the main methodological categories.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Major DTI Prediction Methodologies

| Method Category | Core Principle | Typical Data Inputs | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Similarity-Based [3] | Assumes structurally similar drugs share similar targets. | Drug SMILES, molecular fingerprints. | Computationally efficient. | Overlooks complex biochemical properties; assumes similar drugs have same targets. |

| Structure-Based [3] | Predicts binding mode and affinity based on 3D structures. | 3D structures of drugs and target proteins. | Provides detailed mechanistic insights. | Requires 3D structures; computationally expensive. |

| Network-Based [3] [2] | Models interactions within a graph of biological entities. | Drug-drug similarity, protein-protein interaction, known DTI networks. | Captures system-level relationships. | Relies on large, high-quality interaction data; poor performance on sparse networks. |

| Deep Learning (Sequence-Based) [4] | Uses neural networks to learn from raw sequences. | Drug SMILES strings, protein amino acid sequences. | Does not require expert-designed features; can learn complex patterns. | May lose structural information present in non-sequential representations. |

| Deep Learning (Graph-Based) [2] [4] | Learns representations from molecular graphs and biological networks. | Molecular graphs, heterogeneous biological networks. | Explicitly captures structural and relational information. | Can be less flexible and efficient on very large-scale graphs [5]. |

| Multimodal Learning [1] [3] | Integrates multiple data types and modalities into a unified model. | SMILES, molecular graphs, protein sequences, textual descriptions, ontologies. | Captures complementary signals; can lead to more robust and generalizable predictions. | Increased model complexity; requires strategies to handle modality imbalance. |

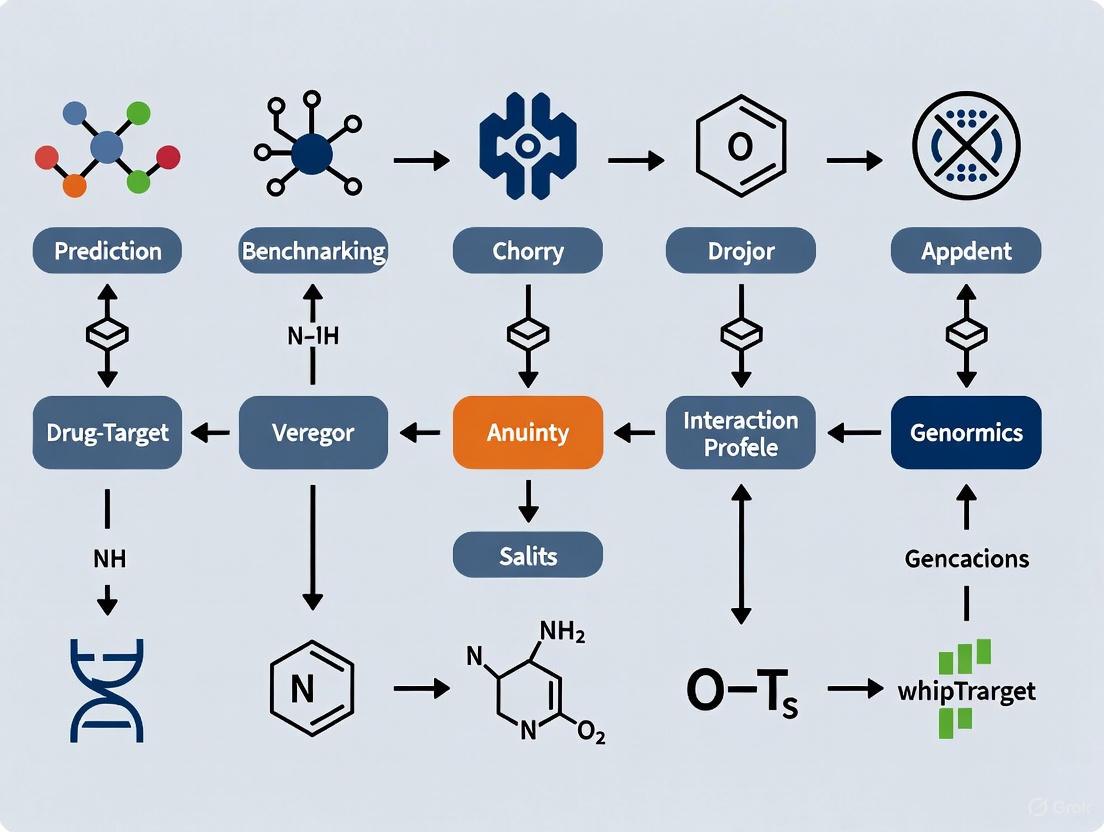

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and data flow between these primary methodological categories.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

Systematic benchmarking is crucial for objectively comparing the performance of various DTI prediction methods. The GTB-DTI benchmark provides a standardized framework for evaluating numerous models, particularly those based on Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Transformers, across multiple datasets and tasks [4]. The following table synthesizes key quantitative results from recent state-of-the-art studies, focusing on standard performance metrics such as Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR).

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of State-of-the-Art DTI Models

| Model Name | Core Methodology | Dataset | AUROC | AUPR | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hetero-KGraphDTI [2] | Knowledge-regularized Graph Neural Network | Multiple Benchmarks | 0.98 (Avg) | 0.89 (Avg) | Frontiers in Bioinformatics, 2025 |

| MVPA-DTI [3] | Heterogeneous Network with Multiview Path Aggregation | Not Specified | 0.966 | 0.901 | JMIR Medical Informatics, 2025 |

| GAN+RFC (on IC50) [6] | GAN for Data Balancing + Random Forest | BindingDB-IC50 | 0.9897 | - | Scientific Reports, 2025 |

| GRAM-DTI [1] | Adaptive Multimodal Representation Learning | Four Public Datasets | Outperforms SOTA | Outperforms SOTA | arXiv, 2025 |

| SSCPA-DTI [5] | Substructure Subsequences & Cross-Attention | Human, C.elegans, KIBA | Superior Performance | Superior Performance | PLOS One, 2025 |

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Frameworks

A critical aspect of benchmarking is the use of rigorous and reproducible experimental protocols. The DDI-Ben framework, for instance, emphasizes the importance of simulating real-world distribution changes between known drugs and new drug candidates, a factor often overlooked by traditional independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) evaluations [7]. For model evaluation, it is essential to use established benchmark datasets with known outcomes and a suite of evaluation measures, as no single metric can fully capture all aspects of performance [8]. Common protocols include:

- k-fold Cross-Validation: The dataset is partitioned into k disjoint subsets (e.g., k=10). The model is trained on k-1 folds and tested on the remaining fold, repeating the process k times. The average performance across all folds is reported to provide a robust estimate of model generalization [8].

- Stratified Splitting: Particularly for imbalanced datasets, this ensures that the distribution of positive and negative interaction labels is preserved across training, validation, and test splits.

- Evaluation Metrics: Beyond AUROC and AUPR, comprehensive evaluations often report sensitivity (recall), specificity, precision, accuracy, and the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) to provide a holistic view of model performance [6] [8].

The workflow for a systematic benchmarking experiment, integrating these protocols, is visualized below.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The development and benchmarking of modern DTI predictors rely on a suite of publicly available datasets, software libraries, and pre-trained models. These "research reagents" form the foundational toolkit for scientists in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for DTI Prediction Benchmarking

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function in DTI Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| BindingDB [6] | Database | Provides curated binding affinity data (Kd, Ki, IC50) for drug-target pairs. | Used as a primary source for training and testing data, especially for regression tasks. |

| DrugBank [2] | Database | A comprehensive knowledge base for drug and drug-target information. | Used for constructing heterogeneous networks and for external validation of predictions. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) [2] | Knowledge Base | Provides a structured framework of gene and gene product attributes. | Integrated as prior biological knowledge to regularize and improve model interpretability. |

| ESM-2 [1] | Pre-trained Model | A large-scale protein language model that generates embeddings from amino acid sequences. | Used as a frozen encoder to extract powerful, biophysically relevant protein features. |

| MolFormer [1] | Pre-trained Model | A transformer-based model pre-trained on large molecular datasets. | Used to generate initial molecular representations from SMILES strings. |

| GNN Frameworks (e.g., PyTor Geometric) | Software Library | Provides implementations of various Graph Neural Network architectures. | Used to build and train models that learn directly from molecular graph structures. |

| DDI-Ben [7] | Benchmarking Framework | A framework for evaluating DDI prediction methods under realistic distribution shifts. | Used to test model robustness and generalizability to new, unseen drugs. |

The systematic benchmarking of drug-target interaction prediction methods reveals a rapidly evolving field where multimodal and knowledge-informed approaches are setting new state-of-the-art performance levels [1] [3] [2]. The integration of diverse data modalities—from molecular structures and protein sequences to textual descriptions and ontological knowledge—appears to be a key driver for building more robust, accurate, and generalizable models [1]. Furthermore, the community's growing emphasis on rigorous benchmarking frameworks like GTB-DTI [4] and DDI-Ben [7] is crucial for ensuring fair comparisons and fostering reproducible research. Future progress will likely depend on continued innovation in model architectures, the development of larger and more diverse benchmark datasets, and a stronger focus on evaluating model performance under realistic, challenging conditions that mirror the true complexities of drug discovery.

The process of identifying new drug-target interactions (DTIs) is a critical foundation of pharmaceutical development, but it is fraught with a fundamental "data trilemma" that hinders computational progress. Researchers face three interconnected challenges: data sparsity (limited known interactions for the vast space of possible drug-target pairs), severe class imbalance (with non-interactions vastly outnumbering known interactions), and the prohibitive cost and time of wet-lab experiments required to generate new high-quality data [9] [10] [11]. While biochemical experimental methods for identifying new DTIs on a large scale remain expensive and time-consuming, computational prediction methods have emerged as essential tools for narrowing the search space and reducing development costs [9] [10]. The performance and reliability of these computational models, however, are intrinsically limited by the very data challenges they aim to overcome. This guide examines the core challenges in DTI prediction benchmarking, providing a structured comparison of methodological approaches and their effectiveness in addressing these fundamental limitations.

Understanding the Fundamental Challenges

Data Sparsity and the "Cold Start" Problem

Data sparsity in DTI prediction arises from the enormous theoretical interaction space between all possible drug compounds and protein targets, contrasted with the relatively minuscule fraction of interactions that have been experimentally verified. This challenge is particularly acute for novel drugs or targets, creating a "cold start" problem where prediction models must make inferences without historical interaction data [10]. The DTIAM framework highlights that this limitation severely constrains the generalization ability of most existing methods when new drugs or targets are identified for complicated diseases [10]. Benchmarking studies consistently show that models achieving excellent performance on known drug-target pairs suffer substantial performance degradation under realistic scenarios involving newly developed compounds, simulating the real-world distribution changes between established and emerging drugs [7].

Data Imbalance and Long-Tailed Distributions

The data imbalance problem in DTI prediction manifests in two dimensions: the overwhelming predominance of non-interactions over known interactions, and the "long-tail" distribution of multi-functional peptides where many functional categories have scarce positive examples [12]. This imbalance leads models to develop a bias toward the majority class (non-interactions), resulting in poor sensitivity for detecting true interactions. The AMCL study on multi-functional therapeutic peptide prediction explicitly notes that "long-tailed data distribution problems" significantly challenge the identification of peptide functions, as conventional methods struggle to learn robust feature representations for categories with limited examples [12]. In binary DTI classification, the unknown interactions are typically treated as negative samples, further exacerbating the imbalance issue and potentially introducing label noise into the training process [3].

The High Cost of Wet-Lab Experimental Verification

Wet-lab experiments remain the gold standard for validating drug-target interactions but constitute a major bottleneck in the discovery pipeline. Conventional peptide research methodologies that primarily rely on wet experiments, including chemical synthesis and biological expression systems, are not only costly but also time-consuming in terms of optimization, thereby limiting the efficiency of peptide drug development [12]. The enormous resources required for experimental verification create a dependency cycle where computational models lack sufficient high-quality training data, yet generating that data requires substantial investment in laboratory work. This economic reality underscores the critical need for computational methods that can maximize the utility of existing data while providing sufficiently accurate predictions to prioritize the most promising candidates for experimental validation [9].

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

Quantitative Performance Comparison of DTI Prediction Methods

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DTI Prediction Methods Across Different Challenges

| Method | Approach Type | Key Features | Performance on Sparse Data | Handling of Data Imbalance | Cold Start Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTIAM [10] | Self-supervised pre-training | Multi-task self-supervised learning on molecular graphs and protein sequences | Excellent - learns from large unlabeled data | Robust - leverages contextual information from pre-training | State-of-the-art in drug and target cold start scenarios |

| AMCL [12] | Multi-label contrastive learning | Semantic data augmentation, supervised contrastive learning with hard sample mining | Effective for long-tailed distributions | Specialized for imbalance - uses Focal Dice Loss and Distribution-Balanced Loss | Not specifically reported |

| MVPA-DTI [3] | Heterogeneous network with multiview learning | Integrates molecular transformer and protein LLM (Prot-T5) with biological network | Good - utilizes multi-source heterogeneous data | Not specifically addressed | Not specifically reported |

| GAN+RFC [6] | Hybrid ML/DL with generative modeling | GANs for synthetic minority data, Random Forest classifier | Good - synthetic data generation expands training set | Excellent - specifically designed for imbalance with GAN oversampling | Not specifically reported |

| DDI-Ben Framework [7] | Benchmarking for distribution changes | Evaluates robustness under distribution shifts | Focuses on evaluation under sparsity conditions | Not a prediction method itself | Specifically designed to measure performance degradation |

| Deep Learning Methods [11] | Various deep architectures | Multitask learning, automatic feature construction | Superior to conventional ML in large-scale studies | Benefits from multitask learning across assays | Generally suffers but outperforms other methods |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Robust Benchmarking with Cluster-Cross-Validation

To address the compound series bias inherent in chemical datasets, rigorous benchmarking studies employ cluster-cross-validation strategies [11]. This protocol involves:

- Clustering: Grouping chemical compounds based on structural similarity into distinct clusters or scaffolds

- Data Splitting: Partitioning whole clusters into training and test sets rather than individual compounds

- Performance Evaluation: Training models on training clusters and evaluating on entirely unseen structural clusters

This method ensures that performance estimates reflect real-world scenarios where models must predict interactions for novel compound scaffolds, providing a more realistic assessment of model utility in actual drug discovery settings [11]. The nested cross-validation extension further prevents hyperparameter selection bias by using an outer loop for performance measurement and an inner loop exclusively for hyperparameter tuning [11].

Distribution Shift Simulation Framework

The DDI-Ben framework introduces a systematic approach to evaluate model robustness under realistic conditions [7]:

- Distribution Change Simulation: Creating benchmark datasets that simulate distribution changes between known and new drugs

- Drug Split Strategies: Implementing various data partitioning strategies based on drug approval timelines and structural properties

- Performance Monitoring: Tracking performance metrics across different distribution shift scenarios to quantify robustness degradation

This experimental protocol reveals that most existing approaches suffer substantial performance degradation under distribution changes, though LLM-based methods and integration of drug-related textual information show promising robustness [7].

Imbalance-Aware Training with Combined Loss Functions

The AMCL framework addresses data imbalance through a sophisticated training methodology [12]:

- Semantic-Preserving Data Augmentation: Integrating back-translation substitution, sequence reversal, and random replacement of similar amino acids

- Multi-label Supervised Contrastive Learning: With hard sample mining to enhance feature discrimination

- Weighted Combined Loss: Combining Focal Dice Loss (FDL) and Distribution-Balanced Loss (DBL) to mitigate class imbalance

- Category-Adaptive Threshold Selection: Assigning independent decision thresholds for each functional category

This comprehensive approach demonstrated significant improvements across multiple key metrics, including Absolute True (from 0.637 to 0.652) and Accuracy (from 0.696 to 0.707) compared to previous state-of-the-art methods [12].

Performance Metrics Across Experimental Settings

Table 2: Detailed Performance Metrics of Key DTI Prediction Methods

| Method | AUROC | AUPR | Accuracy | Absolute True | Key Strengths | Evaluation Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVPA-DTI [3] | 0.966 | 0.901 | - | - | Integrates 3D structure and protein sequences | Standard benchmark |

| GAN+RFC (Kd) [6] | 0.994 | - | 0.975 | - | Exceptional on BindingDB-Kd data | BindingDB-Kd dataset |

| GAN+RFC (Ki) [6] | 0.973 | - | 0.917 | - | Strong on Ki measurements | BindingDB-Ki dataset |

| AMCL [12] | - | - | 0.707 | 0.652 | Superior on multi-functional peptides | Multi-functional therapeutic peptides |

| DTIAM [10] | Superior to baselines | Superior to baselines | - | - | Best in cold start scenarios | Warm start, drug cold start, target cold start |

| Deep Learning [11] | Significantly outperforms competitors | Significantly outperforms competitors | - | - | Superior in large-scale study | Cluster-cross-validation on 1,300 assays |

Visualization of Methodologies and Workflows

DTI Prediction Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Workflow for Robust DTI Prediction Benchmarking. This workflow illustrates the multi-stage process from data collection to evaluation, highlighting strategies to address data sparsity, imbalance, and distribution shifts.

Data Sparsity and Imbalance Mitigation Strategies

Diagram 2: Strategies for Addressing Data Sparsity and Imbalance in DTI Prediction. This diagram maps specific computational techniques to the fundamental data challenges they address, showing how modern methods mitigate data limitations.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DTI Prediction Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Databases | Function in Research | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL [11], BindingDB (Kd, Ki, IC50) [6] | Provide experimentally validated interactions for model training and validation | Benchmarking, training data source, performance evaluation |

| Protein Language Models | Prot-T5 [3], ProtBERT [3] | Extract biophysically and functionally relevant features from protein sequences | Protein representation learning, feature extraction for cold start scenarios |

| Molecular Representation Tools | Molecular Attention Transformer [3], MACCS Keys [6] | Capture 3D structural information and chemical features from drug compounds | Drug representation learning, structural similarity computation |

| Benchmarking Frameworks | DDI-Ben [7], Cluster-Cross-Validation [11] | Evaluate model robustness under realistic conditions and distribution shifts | Method comparison, robustness assessment, real-world performance estimation |

| Data Augmentation Libraries | GAN-based oversampling [6], Semantic-preserving augmentation [12] | Generate synthetic data to address class imbalance and data sparsity | Minority class expansion, training set diversification |

| Specialized Loss Functions | Focal Dice Loss (FDL) [12], Distribution-Balanced Loss (DBL) [12] | Mitigate class imbalance during model training by adjusting learning focus | Handling long-tailed distributions, multi-functional prediction |

| Heterogeneous Data Sources | Disease networks, Side effect databases [3] | Provide additional biological context beyond direct drug-target pairs | Multi-view learning, biological knowledge integration |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide reveals that while significant challenges remain in DTI prediction due to data sparsity, imbalance, and experimental costs, the field has developed sophisticated methodological responses to these limitations. Self-supervised pre-training approaches like DTIAM demonstrate remarkable effectiveness in cold-start scenarios by leveraging unlabeled data [10], while specialized frameworks like AMCL show that carefully designed loss functions and data augmentation strategies can substantially mitigate imbalance problems [12]. The consistent finding across studies that deep learning methods outperform traditional machine learning approaches in large-scale evaluations [11] underscores the importance of representation learning in overcoming data limitations.

The evolution of benchmarking practices toward more realistic evaluation protocols—including cluster-cross-validation and explicit testing under distribution shifts [7] [11]—represents crucial progress in aligning methodological research with real-world application needs. As the field advances, the integration of large language models for biomolecular sequence understanding [3] and the development of unified frameworks that simultaneously address multiple prediction tasks [10] offer promising pathways toward more data-efficient and robust DTI prediction systems. These advances collectively contribute to reducing the dependency on costly wet-lab experiments while increasing the likelihood of computational predictions successfully translating to experimental validation.

The accurate prediction of drug-target interactions (DTIs) is a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, enabling the rational design of therapeutics, drug repurposing, and the elucidation of mechanisms of action [1]. The development and benchmarking of DTI prediction models rely heavily on public datasets, which have evolved significantly in scale, composition, and biological realism over time. Early gold-standard datasets, such as those introduced by Yamanishi et al., provided a foundational benchmark but are increasingly seen as limited for contemporary needs [13]. Meanwhile, newer resources like DrugBank and BIOSNAP offer greater scale and network complexity but introduce their own challenges regarding data integration and fair model evaluation [14] [13].

This guide objectively compares these pivotal datasets, framing the analysis within the critical context of DTI prediction benchmarking research. The performance of a DTI model is not inherent to its algorithm alone but is profoundly shaped by the dataset used for its training and evaluation. Factors such as dataset size, the diversity of protein families, the balance between positive and negative interactions, and the experimental setting used for benchmarking can lead to dramatic differences in reported performance [13] [15]. Therefore, a deep understanding of dataset characteristics and their impact on benchmarking is essential for researchers to select appropriate resources, design robust experiments, and accurately interpret the state of the field.

Dataset Profiles and Comparative Analysis

The landscape of public DTI datasets is diverse, ranging from small, family-specific collections to large, heterogeneous networks. The following section provides a detailed profile and comparison of three key datasets.

Dataset Origins and Core Characteristics

Yamanishi Gold Standard (2008) Introduced in 2008, the Yamanishi dataset is a historical gold standard composed of four distinct subsets based on protein families: Enzymes (E), Ion Channels (IC), G-Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCR), and Nuclear Receptors (NR) [13] [15]. It consolidates DTI information from public databases like KEGG, BRITE, BRENDA, SuperTarget, and DrugBank [15]. A significant limitation is that it contains only true-positive interactions (unary data), ignoring quantitative affinities and the dose-dependent nature of drug-target binding [15].

DrugBank-DTI DrugBank is a comprehensive knowledge repository that provides detailed information on drugs, targets, and their interactions [16] [13]. The DrugBank-DTI dataset, derived from this resource, is substantially larger and more up-to-date than the Yamanishi set. It spans a wide range of therapeutic categories and target proteins, offering a broad view of the drug-target interaction space [13].

BIOSNAP (Stanford Biomedical Network Dataset Collection) BIOSNAP is a collection of diverse biomedical networks [14] [17]. Its DTI-specific component, such as the "ChG-Miner" network, contains thousands of drug-target edges [14] [13]. Like DrugBank, it represents a modern, large-scale network suitable for training complex deep-learning models, though its construction can lead to a loss of some original drug and protein nodes when integrated into heterogeneous graphs for specific models [13].

Quantitative Dataset Comparison

The table below summarizes the core quantitative differences between the datasets, highlighting the evolution in scale and scope.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Public DTI Datasets

| Characteristic | Yamanishi (2008) | DrugBank-DTI | BIOSNAP (ChG-Miner) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publication Year | 2008 [13] | Ongoing (Modern) [13] | Ongoing (Modern) [14] |

| Source Databases | KEGG, BRITE, BRENDA, SuperTarget, DrugBank [15] | DrugBank [13] | Consolidated from multiple sources [14] |

| Number of DTI Edges | Fewer than 100 per subset (e.g., NR) [13] | >15,000 [13] | 15,424 [14] |

| Protein Family Scope | Family-specific subsets (E, IC, GPCR, NR) [13] | Diverse range of protein families [13] | Diverse range of protein families [14] |

| Data Type | Binary interactions (True positives only) [15] | Primarily binary interactions | Binary interactions [14] |

| Key Strength | Established, focused benchmark for specific protein families | Scale, therapeutic context, and broad target diversity | Scale and integration within a larger biomedical network ecosystem [14] [17] |

| Key Limitation | Small, outdated, lacks quantitative affinities, can introduce bias [13] [15] | Requires binarization of affinity data if used from sources like BindingDB [13] | Network construction for models may shrink original dataset size [13] |

Impact on Model Performance and Generalization

The choice of dataset directly impacts the perceived performance and real-world applicability of DTI prediction models.

- Generalization Across Protein Families: Models trained on focused datasets like a Yamanishi subset may not generalize well to other protein families due to inherent biases [13]. In contrast, models trained on diverse datasets like DrugBank and BIOSNAP are exposed to a wider array of target types, potentially enhancing their generalization capabilities [13].

- The Problem of Data Leakage in Benchmarking: A critical issue in DTI benchmarking is the distinction between transductive and inductive learning settings [13]. Transductive models use all available data (including test samples) during training and are typically evaluated under the "S1" setting, where training and test sets share both drugs and targets. This can lead to data leakage and over-optimistic, inflated performance (e.g., AUCs >0.9) that does not reflect a model's ability to predict interactions for truly novel drugs or targets [13]. A baseline transductive classifier can achieve near-perfect performance under these conditions [13].

- Realistic Experimental Settings: For a realistic assessment of a model's utility in drug repurposing, it should be evaluated under more challenging settings [15]:

- S2: Predicting new targets for known drugs.

- S3: Predicting new drugs for known targets.

- S4: Predicting interactions for both new drugs and new targets (the most challenging "cold-start" problem) [15]. Inductive models, which learn a generalizable function, are better suited for these realistic settings and are therefore more suitable for practical drug repurposing [13].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Benchmarking

To ensure fair and realistic comparison of DTI prediction models, researchers should adhere to rigorous experimental protocols. The following workflow outlines a robust benchmarking process that accounts for dataset selection, data preparation, and critical evaluation settings.

Diagram: Robust Workflow for DTI Model Benchmarking

Detailed Methodology for Key Experimental Steps

1. Data Curation and Negative Sampling Most DTI datasets contain only verified positive interactions. Therefore, generating reliable negative samples (pairs unlikely to interact) is crucial. Randomly selecting unknown pairs as negatives can introduce false negatives, as some may be true but undiscovered interactions.

- Advanced Protocol: Employ a biologically-driven negative sampling strategy. Instead of random selection, use structural dissimilarity. One effective method involves using the root mean square deviation (RMSD) between drug structures to select negative pairs that are chemically distant from known interacting pairs [13]. This approach has been shown to help uncover true interactions that would be missed by traditional random subsampling [13].

2. Evaluation Settings and Data Splitting The method for splitting data into training and test sets must reflect the real-world application scenario.

- Standard Protocol: Implement the four experimental settings defined in the literature [15]:

- Setting Sp (Strict): Training and test sets share both drugs and targets. This is the least realistic setting and can lead to inflated performance. It involves randomly hiding a fraction of known interactions for recovery.

- Setting Sd (New Drug): Test sets contain drugs not seen during training. Evaluates the model's ability to predict targets for novel compounds.

- Setting St (New Target): Test sets contain targets not seen during training. Evaluates the model's ability to find new drugs for novel targets.

- Setting S4 (Cold Start): Test sets contain both new drugs and new targets. This is the most challenging and realistic setting for drug repurposing [13] [15].

3. Performance Metrics and Validation Beyond standard metrics like Area Under the Curve (AUC) and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC), which can be misleading on imbalanced data, additional validation is key.

- Advanced Protocol:

- Use nested cross-validation to properly tune hyperparameters without leaking information from the test set, providing a more realistic performance estimate [15].

- For top-ranked predictions, conduct in vitro experimental validation (e.g., surface plasmon resonance or cell-based assays) to confirm biological activity, moving beyond computational metrics to practical utility [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for conducting DTI prediction research using the discussed datasets.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for DTI Prediction Experiments

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in DTI Research |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Library | Processes drug molecules; converts SMILES to molecular graphs, calculates fingerprints and similarities. [18] |

| ESM-2 | Protein Language Model | Encodes protein sequences into informative, fixed-dimensional feature vectors for model input. [1] |

| MolFormer | Molecular Language Model | Encodes drug SMILES strings or molecular structures into latent representations. [1] |

| GUEST Toolbox | Benchmarking Toolkit | A Python tool provided by ML4BM-Lab to facilitate the design and fair evaluation of new DTI methods. [13] |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Data Framework | A unifying framework to systematically access and evaluate machine learning tasks across the entire drug discovery pipeline. [17] |

| PyTorch Geometric (PyG) / DGL | Deep Learning Library | Specialized libraries for implementing Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) on graph-structured data like DTI networks. [17] |

| DrugBank API | Data Access | Programmatic access to the latest DrugBank data for updating and curating DTI datasets. [16] |

| AlphaFold DB | Protein Structure DB | Provides high-accuracy predicted 3D protein structures for incorporating structural information into models. [18] |

The evolution from focused, historical datasets like Yamanishi to large-scale, heterogeneous networks like DrugBank and BIOSNAP reflects the growing complexity and ambition of DTI prediction research. While modern datasets enable the training of more powerful models, they also demand more sophisticated benchmarking practices. Researchers must move beyond simplistic, transductive evaluations that report inflated performance and instead adopt rigorous, biologically-grounded protocols that test a model's ability to generalize in realistic scenarios, such as predicting interactions for novel drugs or targets. The future of robust DTI benchmarking lies in the community-wide adoption of standardized tools, realistic data splits, and comprehensive negative sampling strategies, ensuring that reported progress translates into genuine advances in drug discovery and repurposing.

The Critical Need for Standardized Benchmarking in an Evolving Field

The field of drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction is undergoing a rapid transformation, driven by the adoption of sophisticated deep learning models such as graph neural networks (GNNs) and Transformers [4]. These models demonstrate exceptional performance by effectively extracting structural information from molecular data, which is crucial for understanding binding affinity—a key factor in therapeutic efficacy, target specificity, and drug resistance delay [4]. However, the accelerated pace of algorithmic development has created a significant challenge: the lack of standardized benchmarking. Recent surveys highlight that novel methods are often evaluated under vastly different hyperparameter settings, datasets, and metrics [4]. This inconsistency significantly limits meaningful algorithmic comparison and progress. Without a unified framework, it is impossible to determine whether performance improvements stem from a fundamentally superior model architecture or simply from advantageous but non-standardized experimental conditions. This article argues for the critical need for standardized benchmarking in DTI prediction, providing a comparative guide of current methodologies grounded in the latest research.

Macroscopical Comparison of Structure Learning Paradigms

From a structural perspective, deep learning-based frameworks for DTI prediction can be broadly categorized into explicit and implicit structure learning methods, each with distinct advantages and operational mechanisms [4].

Explicit Structure Learning with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): GNNs operate directly on graph-based representations of molecules, where atoms are nodes and chemical bonds are edges [4]. Through iterative message-passing mechanisms, GNNs explicitly propagate information through the graph to learn node and edge features, thereby capturing the structural and functional relationships between atoms [4]. The core mathematical formulation for a GNN layer involves aggregating and combining features from a node's neighbors, often followed by a non-linear transformation [4]. For example, a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) layer can be represented as ( \mathbf{H}^{(l+1)} = \sigma(\tilde{\mathbf{D}}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\tilde{\mathbf{A}}\tilde{\mathbf{D}}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\mathbf{H}^{(l)}\mathbf{W}^{(l)}) ), where ( \tilde{\mathbf{A}} ) is the adjacency matrix with self-connections, ( \tilde{\mathbf{D}} ) is its degree matrix, ( \mathbf{H}^{(l)} ) is the node feature matrix at layer ( l ), and ( \mathbf{W}^{(l)} ) is a layer-specific trainable weight matrix [4]. The final molecule representation is derived using a READOUT function that processes all node features from the final GNN layer [4].

Implicit Structure Learning with Transformers: Transformer-based methods, originally designed for natural language processing, use self-attention mechanisms to process drug molecules represented as SMILES strings [4]. Unlike GNNs, Transformers do not explicitly model molecular topology. Instead, they implicitly weight the correlations between different parts of the input SMILES string, allowing them to capture long-range dependencies and contextual information without a pre-defined graph structure [4].

The macroscopic performance of these two strategies is not uniform; their effectiveness varies significantly across different datasets and tasks, suggesting that a hybrid approach may be necessary for optimal generalization [4].

Experimental Protocol for Macroscopical Comparison

To ensure a fair comparison between these two paradigms, a standardized benchmarking protocol is essential. The GTB-DTI benchmark, for instance, lays a foundation for reproducibility by using optimal hyperparameters reported in original papers for each model [4]. The general workflow involves:

- Data Preparation: Six widely used public datasets for DTI classification and regression tasks are employed [4]. Drug molecules are featurized using multiple techniques that inform their chemical and physical properties [4].

- Model Training: GNN-based (explicit) and Transformer-based (implicit) drug encoders are trained separately. Target proteins are encoded using convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), or Transformers [4].

- Evaluation: The embeddings of drugs and targets are integrated, and their interaction is predicted using a multi-layer perceptron (MLP). Model effectiveness is measured using standard metrics like AUC (Area Under the Curve) and AUPR (Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve). Efficiency is assessed via peak GPU memory usage, running time, and convergence speed [4].

Performance Benchmarking of State-of-the-Art Models

A comprehensive, microscopical comparison of 31 different models across six datasets reveals significant performance variations. The following table summarizes the quantitative results for a selection of prominent models and frameworks, highlighting the impact of standardized assessment.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of DTI Prediction Models

| Model Name | Core Methodology | Dataset | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Reference / Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hetero-KGraphDTI | GNN with Knowledge Integration | Multiple Benchmarks | Average AUC | 0.98 | [2] |

| Average AUPR | 0.89 | [2] | |||

| Model by Ren et al. (2023) | Multi-modal GCN | DrugBank | AUC | 0.96 | [2] |

| Model by Feng et al. | Graph-based, Multi-networks | KEGG | AUC | 0.98 | [2] |

| GTB-DTI Model Combo | Hybrid (GNN + Transformer) | Various Datasets | Regression Results | State-of-the-Art (SOTA) | [4] |

| Classification Results | Performs similarly to SOTA | [4] |

Experimental Protocol for Model Evaluation

The benchmarking of individual models, such as the Hetero-KGraphDTI framework, follows a rigorous experimental procedure [2]:

- Graph Construction: A heterogeneous graph is built, integrating multiple data types (chemical structures, protein sequences, interaction networks). A data-driven approach learns the graph structure and edge weights based on feature similarity and relevance [2].

- Graph Representation Learning: A graph convolutional encoder learns low-dimensional embeddings of drugs and targets. This encoder uses a multi-layer message-passing scheme and often incorporates an attention mechanism to assign importance weights to different edges, reducing noise [2].

- Knowledge Integration: Prior biological knowledge from sources like Gene Ontology (GO) and DrugBank is incorporated using a knowledge-aware regularization framework. This encourages the learned embeddings to align with known ontological and pharmacological relationships, improving biological plausibility and interpretability [2].

- Enhanced Negative Sampling: Recognizing the positive-unlabeled (PU) learning nature of DTI prediction, a sophisticated negative sampling strategy is implemented to better train the model on non-interacting pairs [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful DTI prediction relies on a suite of computational "reagents" and resources. The table below details key components required for building and evaluating models in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DTI Prediction

| Item Name | Type | Function in the DTI Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| SMILES Strings | Data Representation | A line notation system for representing drug molecule structures in a string format, serving as a common input for sequence-based models like Transformers [4]. |

| Molecular Graph | Data Representation | A graph-based representation of a drug molecule where nodes are atoms and edges are chemical bonds; the fundamental input for GNN-based models [4]. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) | Knowledge Base | A major bioinformatics resource used for knowledge integration, providing structured, ontological relationships to infuse biological context into learned embeddings [2]. |

| DrugBank | Knowledge Base | A comprehensive database containing drug and drug-target information, used for knowledge-based regularization and ground-truth validation [2]. |

| Heterogeneous Graph | Computational Framework | An integrated graph structure that combines multiple types of nodes (drugs, targets) and edges (similarities, interactions) for holistic representation learning [2]. |

| Graph Attention Mechanism | Algorithmic Component | A learnable component that allows the model to assign varying levels of importance to different neighbors during message passing, improving interpretability and focus [2]. |

Visualizing the Standardized Benchmarking Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key components of a robust benchmarking framework for DTI prediction, as synthesized from the latest research.

The pursuit of accurate and reliable drug-target interaction prediction is paramount for accelerating drug discovery. As the field evolves with increasingly complex models, the absence of standardized benchmarking emerges as a critical bottleneck. Comprehensive efforts like GTB-DTI demonstrate that fair comparisons, achieved through individually optimized configurations and consistent evaluation metrics, are not merely academic exercises but are essential for deriving meaningful insights [4]. These benchmarks reveal the unequal performance of explicit and implicit structure learning methods across datasets and pave the way for powerful hybrid model combos that achieve state-of-the-art results [4]. Furthermore, integrating biological knowledge directly into the learning process, as seen in frameworks like Hetero-KGraphDTI, enhances both performance and interpretability, moving the field beyond black-box predictions [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, adhering to and contributing to these standardized benchmarks is no longer optional but a necessary step to ensure algorithmic progress is real, measurable, and ultimately, translatable to real-world therapeutic impacts.

A Deep Dive into DTI Prediction Methodologies: From Classical to AI-Driven Approaches

Predicting the interactions between drugs and their protein targets is a fundamental step in modern drug discovery, crucial for identifying new therapeutic applications and understanding potential side effects [19] [20]. Experimental methods to identify these relationships, while reliable, are often time-consuming, costly, and laborious, presenting significant challenges in the rapid development of new medications [19]. Computational approaches have emerged as powerful alternatives to efficiently narrow down the search space for experimental validation [21]. Among these, three traditional methodologies form the cornerstone of in silico prediction: ligand-based, docking-based (structure-based), and chemogenomic approaches [19]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these foundational strategies, focusing on their underlying principles, performance metrics, and practical applications within drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction, serving as a benchmark for evaluating current and future methodologies in the field.

The three approaches leverage different types of biological and chemical information to predict whether a small molecule (drug) will interact with a specific protein target.

Ligand-Based Approaches

The central premise of ligand-based methods is the "similarity principle," which states that chemically similar compounds are likely to exhibit similar biological activities and target the same proteins [20] [22]. These methods do not require 3D structural information of the target protein. Instead, they extract chemical features from molecules using fingerprint algorithms (e.g., Morgan fingerprints, MACCS keys) and compute similarity scores, such as the Tanimoto coefficient, between a query compound and ligands with known activities [19] [20]. The performance of these methods is highly dependent on the quality and breadth of known ligand-target annotations.

Docking-Based (Structure-Based) Approaches

Docking-based approaches model the physical interaction between a drug and its target protein [23]. They predict the three-dimensional pose of a ligand within a specific binding site of a protein and estimate the binding affinity using a scoring function [23] [24]. This process involves sampling numerous possible conformations and orientations of the ligand in the binding site and ranking them based on computed interaction energies. These methods require a 3D structure of the target protein, which can come from X-ray crystallography, NMR, or homology modeling [23]. The accuracy of docking is critically dependent on the scoring function, which can be physics-based, empirical, knowledge-based, or increasingly, machine-learning-based [24].

Chemogenomic Approaches

Chemogenomic methods, also known as chemogenomics, represent a hybrid strategy that systematically screens targeted chemical libraries of small molecules against families of drug targets (e.g., GPCRs, kinases) [25]. The goal is to identify novel drugs and drug targets simultaneously by leveraging the fact that ligands designed for one family member often bind to others [25]. In the context of DTI prediction, feature-based chemogenomic methods represent each drug and protein by a numerical feature vector, combining their physical, chemical, and molecular features into a unified representation for machine learning models [21] [19]. This approach allows for the inference of interactions for proteins with known sequences but unknown 3D structures, and for drugs without close analogs.

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for a hybrid methodology that integrates elements from all three traditional approaches:

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

The performance of these methods is typically evaluated using benchmark datasets and metrics that assess their ability to correctly identify true interactions (positives) while minimizing false predictions.

Key Benchmarking Datasets and Metrics

Common Datasets:

- Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD): A widely used benchmarking set containing 2,950 ligands for 40 different protein targets, each with 36 physically matched but topologically distinct decoy molecules designed to reduce enrichment factor bias [26].

- Golden Standard Datasets: Often include datasets for specific target families such as enzymes, ion channels, G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), and nuclear receptors, used to train and test predictive models [19].

- PDBbind: A comprehensive database of 3D protein-ligand structures with experimentally measured binding affinity data, used for developing and validating docking methodologies and scoring functions [20] [24].

- Large-Scale Docking (LSD) Database: A newer resource providing access to docking results for over 6.3 billion molecules across 11 targets, enabling benchmarking for machine learning and chemical space exploration methods [27].

Common Metrics:

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures the concentration of true active compounds among the top-ranking hits compared to their concentration in the entire database. A key metric for evaluating virtual screening performance [26] [23].

- Area Under the Curve (AUC) / logAUC: Quantifies the overall performance of a ranking method; logAUC specifically emphasizes early enrichment by applying a logarithmic scale to the fraction of the database screened [27].

- Accuracy, Precision, Recall: Standard classification metrics used to evaluate the predictive power of models, especially in feature-based and machine learning approaches [19].

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes the typical performance characteristics and data requirements of the three approaches, synthesized from multiple benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Traditional DTI Prediction Approaches

| Aspect | Ligand-Based Approaches | Docking-Based Approaches | Chemogenomic Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Chemical similarity predicts biological activity [20] | Physical simulation of binding & scoring of poses [23] | Systematic screening of compound families against target families [25] |

| Required Data | Known active ligands for the target [20] | 3D structure of the target protein [23] | Annotated ligand-target interaction data [21] [25] |

| Typical Accuracy/Performance | High if similar ligands are known; performance drops for novel scaffolds [20] | Varies by target & scoring function; can achieve high enrichment (e.g., EF>30 reported in DUD [26]) | High reported accuracy on benchmarks (e.g., >95% on enzymes/GPCRs with advanced feature-based models [19]) |

| Key Strengths | Fast; no protein structure needed; high interpretability [19] [22] | Models physical reality; can find novel scaffolds; provides binding mode [23] [24] | Can generalize to new targets & drugs; broad coverage of chemical space [21] [25] |

| Key Limitations | Fails for targets with few known ligands; cannot find novel scaffolds [20] | Computationally expensive; limited by scoring function accuracy & structure availability [23] [19] | Dependent on quality and scope of training data; "cold start" problem for novel targets [21] |

| Best Suited For | Target classes with rich ligand pharmacology (e.g., GPCRs, kinases) [22] | Targets with high-quality structures and well-defined binding pockets [23] | Proteome-wide interaction prediction and target de-orphanization [21] [25] |

To provide a concrete example of performance in a hybrid context, the following table shows results from a recent feature-based study that employed robust feature selection and classification on golden standard datasets.

Table 2: Performance of a Modern Feature-Based Model (Incorporating Chemogenomic Principles) on Golden Standard Datasets [19]

| Dataset | Reported Accuracy (%) | Classifier Used |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | 98.12 | Rotation Forest |

| Ion Channels | 98.07 | Rotation Forest |

| GPCRs | 96.82 | Rotation Forest |

| Nuclear Receptors | 95.64 | Rotation Forest |

Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Protocols

For researchers aiming to implement or benchmark these traditional approaches, a standard set of computational reagents and protocols is essential.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for DTI Prediction Research

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | A free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening [26] [23] | All (Source of small molecules) |

| PDBbind | Structured Database | Provides protein-ligand complexes with binding affinity data for benchmarking [20] [24] | Docking, Chemogenomics (Training & Testing) |

| Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD) | Benchmark Set | Public set of ligands and matched decoys to evaluate docking enrichment [26] | Docking, Virtual Screening (Benchmarking) |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Open-source software for fingerprint generation, similarity search, and descriptor calculation [20] | Ligand-Based, Chemogenomics (Feature Extraction) |

| AutoDock Vina | Docking Software | Widely used open-source program for molecular docking and scoring [23] [24] | Docking (Pose Prediction & Scoring) |

| PSOVina2 | Docking Software | An optimized docking engine used in workflows for target prediction [20] | Docking (Pose Prediction) |

| Morgan Fingerprints | Molecular Descriptor | A type of circular fingerprint encoding molecular structure, calculated by RDKit [20] | Ligand-Based, Chemogenomics (Similarity & Features) |

| Interaction Fingerprint (IFP) | Structural Descriptor | Encodes the pattern of interactions (H-bonds, hydrophobic contacts) between protein and ligand [20] | Docking, Hybrid (Binding Similarity) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ligand-Based Virtual Screening using Similarity Search

This protocol is adapted from methodologies described in benchmark studies and tool development papers [20] [22].

- Input Preparation: Compile a database of known active ligands for the target of interest. Represent the query compound and all database ligands as SMILES strings.

- Fingerprint Generation: Using a toolkit like RDKit, compute 2D structural fingerprints for all molecules. Common choices include Morgan fingerprints (radius=2), MACCS keys, or Daylight-like fingerprints [20].

- Similarity Calculation: For the query compound, calculate the pairwise Tanimoto coefficient (T) against every ligand in the database. The Tanimoto coefficient is defined as T = N_ab / (N_a + N_b - N_ab), where N_a and N_b are the number of bits set in the fingerprints of molecules a and b, and N_ab is the number of common bits set in both [20].

- Ranking and Hit Identification: Rank all database compounds based on their similarity to the query. Compounds exceeding a predefined similarity threshold (e.g., T > 0.6-0.8 for close analogs, or a more permissive T > 0.4 for a wider net [20]) are considered potential hits.

- Validation: The performance is evaluated by the model's ability to retrieve known actives from a background database (which may include decoys) in retrospective screening, typically measured by enrichment factors or AUC.

Protocol 2: Structure-Based Virtual Screening using Molecular Docking

This protocol outlines a standard docking workflow for hit identification [23] [24].

- Structure Preparation:

- Protein: Obtain the 3D structure from the PDB. Remove water molecules and cofactors not involved in binding. Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and define protonation states of key residues (e.g., His, Asp, Glu).

- Ligand Database: Prepare a library of compounds in a suitable 3D format. Generate plausible tautomers and protonation states at physiological pH. Minimize the energy of each ligand conformation.

- Binding Site Definition: Define the spatial coordinates of the binding site. This is often the known active site from a co-crystallized ligand or predicted using pocket detection algorithms.

- Docking Execution: For each ligand in the database, run the docking program (e.g., AutoDock Vina, DOCK). The software will perform a conformational search, generating multiple putative binding poses.

- Pose Scoring and Selection: The scoring function of the docking program evaluates and ranks each generated pose. The pose with the most favorable (lowest) score is typically selected as the predicted binding mode for that ligand.

- Post-Docking Analysis: The entire library of compounds is ranked based on their best docking score. Top-ranked compounds are selected for further analysis or experimental testing. Performance is benchmarked by the enrichment of known active compounds among the top ranks.

Protocol 3: Feature-Based Chemogenomic DTI Prediction

This protocol is based on modern implementations that use feature extraction and machine learning [21] [19].

- Feature Extraction:

- Proteins: From the protein sequence, extract various feature descriptors. Common ones include EAAC (Composition of Amino Acids), PSSM (Position-Specific Scoring Matrix), and APAAC (Amphiphilic Pseudo Amino Acid Composition) [19].

- Drugs: From the drug's molecular structure, compute fingerprint features such as molecular fingerprints or electro-topological state indices [19].

- Feature Vector Construction: For each drug-target pair, combine the extracted drug and protein feature vectors into a single, unified feature vector representing the interaction pair [19].

- Feature Selection: Apply feature selection algorithms (e.g., IWSSR) to the high-dimensional combined feature set to reduce noise and overfitting, selecting the most discriminative features for DTI prediction [19].

- Model Training and Classification: Train a machine learning classifier (e.g., Rotation Forest, Random Forest) on a labeled dataset of known interacting and non-interacting pairs. The model learns to associate feature patterns with interaction likelihood.

- Prediction and Validation: Use the trained model to predict interactions for unknown pairs. Evaluate performance via cross-validation on benchmark datasets using accuracy, precision, recall, and AUC.

Integrated Applications and Case Studies

The true power of these traditional methods is often realized when they are used in an integrated or hybrid fashion.

The Hybrid Paradigm: LigTMap

The LigTMap server exemplifies a successful hybrid approach [20]. Its workflow, illustrated in Section 2, integrates ligand-based and structure-based methods:

- It first uses a ligand similarity search to shortlist putative targets from a database of proteins with known ligands and structures.

- It then performs molecular docking of the query compound into the binding site of each shortlisted target.

- Finally, it compares the predicted binding mode of the query compound with the native ligand's binding mode using interaction fingerprints.

- A final ranking is produced based on a combination of ligand and binding similarity scores. This method successfully predicted targets for over 70% of benchmark compounds within the top-10 list, demonstrating performance comparable to other leading servers [20].

Chemogenomics in Target De-orphanization and Mechanism of Action Studies

Chemogenomic principles are powerfully applied in determining the Mode of Action (MOA) of traditional medicines and de-orphanizing targets. For instance, in silico target prediction using chemogenomic databases has been used to propose molecular targets for compounds in Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ayurveda, linking them to phenotypic effects like hypoglycemic or anti-cancer activity [25]. In another case, a ligand library for the bacterial enzyme murD was mapped to other members of the mur ligase family using chemogenomic similarity, successfully identifying new target-inhibitor pairs for antibiotic development [25].

Ligand-based, docking-based, and chemogenomic approaches form a robust foundational toolkit for predicting drug-target interactions. As summarized in this guide, each methodology offers distinct advantages and suffers from specific limitations, making them suitable for different scenarios in the drug discovery pipeline. While ligand-based methods are fast and effective for targets with rich ligand data, docking provides a physical model of interaction but demands structural information. Chemogenomic, particularly feature-based, methods offer a powerful machine-learning-driven framework that can generalize across the proteome. The trend in the field is moving toward hybrid methods that combine the strengths of these traditional approaches to achieve higher accuracy and reliability [20]. Furthermore, these established methods are increasingly being integrated with and enhanced by modern deep learning techniques, creating a new generation of predictive tools that build upon these traditional foundations [24]. For researchers, the selection of an approach should be guided by the specific biological question, the available data, and the computational resources, using the benchmarking data and protocols outlined here as a starting point for their investigations.

The accurate prediction of Drug-Target Interactions (DTI) is a critical bottleneck in the drug discovery pipeline. While traditional experimental methods are reliable, they are notoriously time-consuming and expensive, often taking years and consuming significant financial resources [28] [29]. The emergence of computational approaches, particularly deep learning, has dramatically reshaped this domain by providing scalable and cost-effective alternatives for early-stage screening. Among these tools, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have gained tremendous traction due to their unique ability to model complex, non-Euclidean data structures that are pervasive in biological and chemical systems [28]. GNNs operate natively on graph representations, inherently capturing intricate topological and relational information. This makes them exceptionally adept at representing molecules, which naturally conform to graph structures with atoms as nodes and chemical bonds as edges [28].

A significant paradigm shift within this field is the move from implicit learning from sequences to explicit structure learning from molecular graphs. Unlike models that process Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings, GNNs work directly on the graph structure of a drug molecule, allowing them to capture spatial relationships and functional groups that are crucial for binding affinity and specificity [4]. This explicit approach is revolutionizing computational drug discovery by enabling a more nuanced understanding of how drugs interact with their biological targets, thereby facilitating more precise predictions of binding affinities, off-target effects, and therapeutic potential [28].

Comparative Analysis of GNN Architectures for DTI Prediction

The application of GNNs in DTI prediction has led to a diverse ecosystem of architectural variants, each designed to tackle specific challenges in molecular representation learning.

Core Architectural Variants

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs): GCNs form the foundational backbone of many GNN-based DTI models. They operate by propagating and transforming node features across the graph structure using a convolutional operator. Mathematically, this is often represented as ( \mathbf{H}^{(l+1)} = \sigma(\hat{\mathbf{D}}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\hat{\mathbf{A}}\hat{\mathbf{D}}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\mathbf{H}^{(l)}\mathbf{W}^{(l)}) ), where ( \hat{\mathbf{A}} ) is the adjacency matrix with self-loops, ( \hat{\mathbf{D}} ) is its degree matrix, ( \mathbf{H}^{(l)} ) are the node features at layer ( l ), and ( \mathbf{W}^{(l)} ) is a learnable weight matrix [4]. This explicit aggregation of neighbor information allows GCNs to capture the local chemical environment of each atom.

Relational Graph Attention Networks (RGATs): RGATs extend the GAT architecture by incorporating relationship type discrimination between nodes, making them particularly suitable for heterogeneous graphs with multiple edge types [30]. In RGATs, the attention mechanism dynamically weighs the importance of neighboring nodes based on their features and the type of relationship (e.g., single bond, double bond). This allows the model to focus on the most relevant structural components when generating molecular representations [30].

GNNBlock-based Architectures: The GNNBlockDTI model introduces a novel concept of stacking multiple GNN layers into a fundamental block unit called a GNNBlock [31]. This design is specifically intended to capture hidden structural patterns within local ranges of the drug molecular graph. By using GNNBlocks as building blocks, the model can achieve a wider receptive field while maintaining stability in training deeper networks. Within each block, a feature enhancement strategy employs an "expansion-then-refinement" method to improve expressiveness, while gating units filter out redundant information between blocks [31].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance comparison of state-of-the-art GNN models on benchmark DTI datasets (Values are percentages %)

| Model | Architecture Type | Davis (AUPR) | KIBA (AUPR) | DrugBank (Accuracy) | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNNBlockDTI [31] | GNNBlock | - | - | - | Local substructure focus with feature enhancement |

| EviDTI [32] | Multi-modal + EDL | - | - | 82.02 | Uncertainty quantification |

| DeepMPF [33] | Multi-modal + Meta-path | Competitive across 4 datasets | - | - | Integrates sequence, structure, and similarity |

| GraphDTA [4] | GCN/GIN | - | - | - | Baseline GNN for DTI |

| MolTrans [32] | Transformer | - | - | - | Implicit structure learning benchmark |

Note: Specific metric values for some models on these datasets were not fully available in the provided search results. The table structure is provided to illustrate comparison dimensions.

Table 2: Cold-start scenario performance for novel DTI prediction (Values are percentages %)

| Model | Accuracy | Recall | F1 Score | MCC | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EviDTI [32] | 79.96 | 81.20 | 79.61 | 59.97 | 86.69 |

| TransformerCPI [32] | - | - | - | - | 86.93 |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Robust benchmarking is essential for evaluating the true performance and practical utility of GNN models in DTI prediction. The GTB-DTI benchmark addresses this need by providing a standardized framework for comparing explicit (GNN-based) and implicit (Transformer-based) structure learning algorithms [4] [34].

Standardized Evaluation Protocols

Comprehensive benchmarking studies follow rigorous experimental protocols to ensure fair comparisons across different model architectures. The GTB-DTI benchmark, for instance, integrates multiple datasets for both classification and regression tasks, using individually optimized hyperparameter configurations for each model to establish a level playing field [4]. Typical evaluation metrics include Accuracy (ACC), Recall, Precision, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), F1 score, Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) [32].

The standard workflow involves several critical steps. First, datasets are partitioned into training, validation, and test sets, commonly in an 8:1:1 ratio [32]. For drug representation, molecular graphs are constructed from SMILES strings using tools like RDKit, with initial node embeddings derived from atomic properties including Atomic Symbol, Formal Charge, Degree, IsAromatic, and IsInRing, resulting in a total dimension of 64 features per node [31]. For target representation, protein sequences are typically encoded using pre-trained models like ProtBert or ProtTrans [31] [32]. Finally, the learned drug and target embeddings are concatenated and processed by a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) classifier to generate interaction predictions [31].

Benchmark Dataset Characteristics

Table 3: Key benchmark datasets for DTI prediction

| Dataset | Interaction Type | Key Characteristics | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Davis [32] | Binding Affinities | Challenging due to class imbalance | Kinase binding affinity prediction |

| KIBA [32] | KIBA Scores | Complex and unbalanced | Broad-spectrum interaction prediction |

| DrugBank [32] | Binary Interactions | Comprehensive drug database | General DTI classification |

| IGB-H [30] | Heterogeneous Graph | 547M nodes, 5.8B edges (for RGAT) | Large-scale benchmarking |

Visualizing GNN Architectures for DTI Prediction

The following diagrams illustrate key architectural components and workflows discussed in this review, created using Graphviz DOT language with the specified color palette.

GNNBlock Internal Architecture with Gating

Successful implementation of GNNs for DTI prediction requires a comprehensive toolkit of software libraries, datasets, and computational resources.

Table 4: Essential research reagents and computational tools for GNN-based DTI prediction

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [31] | Cheminformatics Library | Converts SMILES to molecular graphs; extracts atomic properties | Drug graph construction and featurization |

| ProtTrans/ProtBert [31] [32] | Pre-trained Protein Model | Generates initial protein sequence embeddings | Target representation learning |

| Deep Graph Library (DGL) / PyTorch Geometric | GNN Frameworks | Implements GNN layers and message passing | Model architecture development |

| PrimeKG [29] | Knowledge Graph | Provides drug-disease-protein relationships | Multi-modal data integration |

| Davis/KIBA/DrugBank [32] | Benchmark Datasets | Standardized datasets for training and evaluation | Model benchmarking and validation |

| MG-BERT [32] | Pre-trained Molecular Model | Provides initial drug molecule representations | Drug feature initialization |

| TheraSAbDab [29] | Antibody Database | Structural and sequence data for antibodies | Specialized applications in biologics |

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

While GNNs have demonstrated remarkable success in explicit structure learning for DTI prediction, several frontiers demand attention to translate these computational advances into tangible drug discovery outcomes.

Emerging Research Frontiers

A critical challenge is model interpretability. The complex, multi-layered message-passing mechanisms of GNNs often render their predictions as "black boxes," raising concerns when decisions impact patient health or resource allocation [28]. Future research directions include developing explainable GNN architectures using attention mechanisms, subgraph extraction, and attribution methods designed to pinpoint which molecular substructures or protein residues drive binding predictions [28].

The integration of multi-modal data represents another significant frontier. While GNNs excel at capturing structural intricacies, their predictive performance can be substantially enhanced by incorporating complementary biological context such as gene expression levels, protein-protein interactions, metabolic pathways, and clinical phenotypes [28]. Frameworks like DeepMPF exemplify this approach by integrating sequence modality, heterogeneous structure modality, and similarity modality through meta-path semantic analysis [33].

Uncertainty quantification is emerging as a crucial requirement for real-world deployment. EviDTI addresses this by incorporating evidential deep learning (EDL) to provide confidence estimates alongside predictions, helping to distinguish between reliable and high-risk predictions [32]. This capability is particularly valuable for prioritizing drug candidates for experimental validation, potentially reducing the risk and cost associated with false positives.

Practical Implementation Considerations

From a practical standpoint, scalability remains a pressing issue. Drug discovery datasets can involve millions of molecules and expansive biological networks, posing computational and memory challenges for GNN training [28] [30]. The MLPerf Inference benchmark now includes an RGAT model tested on the IGB-H dataset, which contains 547 million nodes and 5.8 billion edges, highlighting the industry's focus on this challenge [30]. Optimizing algorithmic efficiency through distributed computing and sparse graph representations are active areas of research aimed at enabling large-scale analysis without sacrificing performance [28].

Furthermore, the incorporation of temporal dynamics and 3D structural information represents a frontier for capturing the evolving nature of drug-target binding. Biological interactions are dynamic, influenced by conformational changes, environmental conditions, and temporal factors [28]. Advanced 3D-GNN architectures that can leverage spatial coordinates effectively are crucial for accurately modeling molecular docking and interaction energetics [28].

As these technical challenges are addressed, the interdisciplinary collaboration between computational scientists, chemists, and biologists will be essential to bridge the gap between predictive accuracy and actionable biological insights, ultimately driving more informed decision-making in drug development.

The application of transformer architectures to molecular informatics represents a paradigm shift in computational drug discovery, moving from explicit structure-based approaches to implicit structure learning directly from sequential representations. This transition mirrors the revolution transformers sparked in natural language processing (NLP), where attention mechanisms replaced earlier recurrent architectures. In drug discovery, transformers now learn complex biochemical relationships directly from Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings and protein sequences, bypassing the need for explicit molecular descriptors or three-dimensional structural information that traditionally required significant computational resources and expert curation [35] [36]. The core innovation lies in the self-attention mechanism, which enables these models to weigh the importance of different parts of molecular and protein sequences, effectively learning the "grammar" and "syntax" of biochemical interactions without human-designed features [37] [3].

This approach is particularly valuable for drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction, where accurately identifying molecular binding partners can dramatically accelerate drug repurposing and reduce development costs [3] [2]. By treating molecules and proteins as sequences, transformer models establish a unified framework for representing diverse biological entities, enabling them to capture complex patterns across chemical and biological spaces [36]. This article examines the architectural evolution, performance benchmarks, and practical implementation of transformers that learn implicitly from SMILES and protein sequences, providing researchers with a comprehensive comparison of these powerful alternatives to traditional structure-based methods.

Architectural Evolution: From RNNs to Modern Transformer Hybrids

The Sequence Model Landscape

The development of sequence models for biochemical data has followed a trajectory from recurrent architectures to modern attention-based transformers, with each generation offering distinct advantages for processing molecular and protein sequences.

Table 1: Comparison of Sequence Model Architectures for Molecular Data

| Architecture | Key Mechanisms | Advantages | Limitations | Molecular Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNN | Recurrent connections, hidden state | Simple structure, temporal dynamics | Vanishing gradients, limited memory | Early SMILES processing, simple QSAR |

| LSTM | Input, forget, output gates | Long-term dependency capture, gradient flow | Computational intensity, complexity | Molecular property prediction |

| GRU | Reset and update gates | Faster training, parameter efficiency | Reduced long-range capability | Medium-sequence molecular modeling |