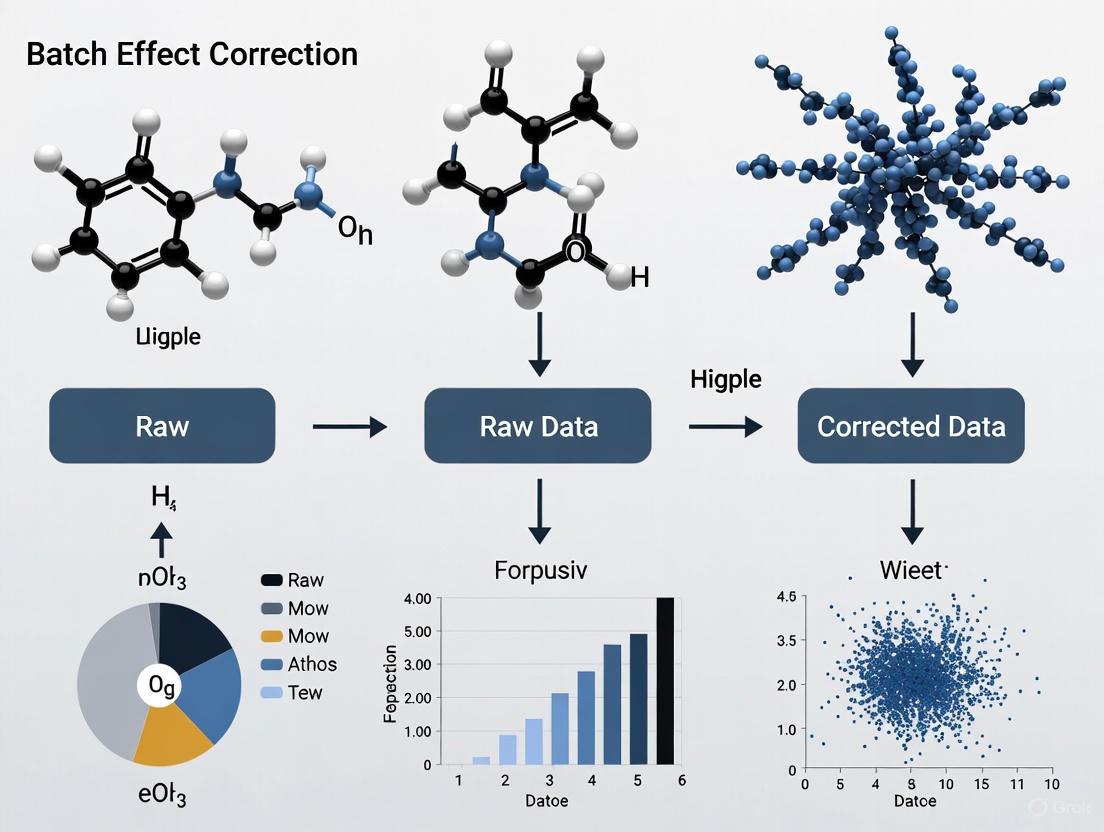

Batch Effect Correction in Chemogenomics: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Data Integration and Drug Discovery

Systematic technical variations, or batch effects, are a pervasive challenge in chemogenomic data, potentially confounding the identification of true biological signals and leading to misleading conclusions in drug discovery.

Batch Effect Correction in Chemogenomics: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Data Integration and Drug Discovery

Abstract

Systematic technical variations, or batch effects, are a pervasive challenge in chemogenomic data, potentially confounding the identification of true biological signals and leading to misleading conclusions in drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of batch effects, a detailed exploration of established and emerging correction methodologies, and strategic troubleshooting for common pitfalls like confounded designs and overcorrection. It further offers a rigorous framework for validating and comparing correction performance using benchmarks from transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, empowering scientists to implement robust data integration strategies that enhance the reliability and reproducibility of their chemogenomic analyses.

Understanding Batch Effects: The Hidden Enemy in Chemogenomic Data

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a batch effect? A batch effect occurs when non-biological factors in an experiment cause systematic changes in the produced data. These technical variations can lead to inaccurate conclusions when they are correlated with experimental outcomes of interest. Batch effects are common in high-throughput experiments like microarrays, mass spectrometry, and various sequencing technologies. [1]

What are the most common causes of batch effects? Batch effects can originate from multiple sources throughout the experimental workflow:

- Different sequencing runs, instruments, or laboratory conditions

- Variations in reagent lots or manufacturing batches

- Changes in sample preparation protocols or personnel handling samples

- Environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, atmospheric ozone levels)

- Time-related factors when experiments span days, weeks, or months [1] [2]

Why are batch effects particularly problematic in chemogenomic research? In chemogenomic studies where researchers screen chemical compounds against biological systems, batch effects can:

- Cause differential expression analysis to identify genes that differ between batches rather than between compound treatments

- Lead clustering algorithms to group samples by batch rather than by true biological similarity to compound exposure

- Result in pathway enrichment analysis highlighting technical artifacts instead of meaningful biological processes

- Severely impact meta-analyses combining data from multiple sources or screening campaigns [2] [3]

How can I detect batch effects in my data? Common approaches to detect batch effects include:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Visualize if samples cluster by batch rather than biological factors

- Hierarchical Clustering: Check if samples group by technical rather than biological variables

- Batch Effect Metrics: Use quantitative measures like kBET or silhouette scores

- Exploratory Visualization: Create PCA plots colored by both batch and biological conditions to identify confounding [2] [4]

What should I do if my biological groups are completely confounded with batches? When biological factors and batch factors are perfectly correlated (e.g., all control samples processed in one batch and all treated samples in another), most standard correction methods fail. In these scenarios:

- Consider using a reference-material-based ratio method if you have concurrently profiled reference materials

- Be transparent about the limitation in your research conclusions

- For future experiments, redesign to avoid complete confounding whenever possible [5] [6]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Batch Effects Detected in PCA Before Differential Expression Analysis

Symptoms:

- Samples cluster strongly by processing date, reagent lot, or personnel in PCA plots

- Biological groups separate by batch rather than by treatment conditions

- High within-group variation correlates with technical factors

Solutions:

Table 1: Batch Effect Correction Algorithms for Omics Data

| Method | Best For | Implementation | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat/ComBat-seq | Microarray & bulk RNA-seq | Empirical Bayes framework; ComBat-seq designed for count data | Handles known batch effects; can preserve biological variation [2] [7] |

| limma removeBatchEffect | Bulk transcriptomics | Linear model adjustment | Works on normalized data; integrated with limma-voom workflow [2] |

| Harmony | Single-cell & multi-omics | PCA-based iterative integration | Effective for complex datasets; handles multiple batch factors [8] [5] |

| Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) | Single-cell RNA-seq | Identifies overlapping cell populations | Uses "anchors" to relate shared populations between batches [1] [8] |

| Ratio-based Methods | Multi-omics with reference materials | Scales data relative to reference samples | Particularly effective for confounded designs [5] |

Step-by-Step Correction Protocol using ComBat-seq:

Problem: Irreproducible Findings Across Multiple Screening Campaigns

Symptoms:

- Biomarkers or signatures identified in one batch don't validate in others

- Inconsistent compound sensitivity profiles across different screening runs

- Poor performance of predictive models when applied to new batches

Solutions:

Table 2: Experimental Design Strategies to Minimize Batch Effects

| Strategy | Implementation | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Randomization | Randomly assign samples from all experimental groups across batches | Prevents confounding of technical and biological factors [4] |

| Balanced Design | Ensure equal representation of biological groups in each batch | Enables batch effects to be "averaged out" during analysis [6] |

| Reference Materials | Include standardized reference samples in each batch | Provides anchor points for ratio-based correction methods [5] |

| Batch Recording | Meticulously document all technical variables | Enables proper statistical modeling of batch effects [1] |

Reference Material Integration Workflow:

Problem: Over-Correction Removing Biological Signal

Symptoms:

- Loss of known biological differences after batch correction

- Reduced statistical power for detecting true differential expression

- Overly homogenized data that lacks expected biological variation

Solutions:

- Use Conservative Parameters: Start with mild correction settings and gradually increase if needed

- Validation with Positive Controls: Monitor known biological differences during correction

- Multiple Method Comparison: Compare results across different correction approaches

- Incorporate Batch in Statistical Models: Instead of pre-correcting, include batch as covariate in final analysis models:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Batch Effect Assessment in Chemogenomic Screens

Purpose: Comprehensively evaluate batch effects in compound screening data

Materials:

- Normalized screening readouts (e.g., viability, expression data)

- Sample metadata including batch identifiers

- R or Python environment with appropriate packages

Procedure:

- PCA Visualization:

Quantitative Batch Metrics:

Batch-Outcome Confounding Assessment:

Protocol 2: Multi-Method Batch Correction Comparison

Purpose: Systematically compare batch correction methods to select the optimal approach

Procedure: 1. Apply Multiple Correction Methods to the same dataset: - ComBat-seq (for count data) - limma removeBatchEffect (for normalized data) - Harmony (for complex multi-batch data) - Ratio-based method (if reference materials available)

Evaluate Using Multiple Metrics:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Biological signal preservation

- Batch Mixing: Integration of batches in reduced dimensions

- Biological Conservation: Preservation of known biological differences

Select Optimal Method based on comprehensive performance across metrics

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Batch Effect Management

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| sva package | Surrogate Variable Analysis | Identifying and correcting for unknown batch effects [1] [2] |

| limma | Linear models for microarray/RNA-seq | Batch correction as part of differential expression analysis [2] |

| Harmony | Integration of multiple datasets | Single-cell and multi-omics data integration [8] [5] |

| Seurat | Single-cell analysis with integration | Integrating single-cell datasets across batches [8] |

| kBET | Batch effect quantification | Measuring the effectiveness of batch integration [7] |

| Reference Materials | Standardized quality controls | Enabling ratio-based correction approaches [5] |

Critical Considerations for Chemogenomic Data

Preserving Compound-Specific Signals: When correcting batch effects in compound screening data, ensure that genuine compound-induced biological variation is not removed. Always validate with known positive controls.

Temporal Batch Effects: In longitudinal compound treatment studies, technical variations correlated with time can be particularly challenging. Consider specialized methods like mixed linear models that can handle time-series batch effects.

Cross-Platform Integration: When integrating public chemogenomic data from different platforms or laboratories, expect substantial batch effects. Progressive integration approaches, starting with most similar datasets, often work best.

Quality Control After Correction: Always verify that batch correction improves rather than degrades data quality by:

- Confirming known biological differences are preserved

- Ensuring technical artifacts are reduced

- Validating with orthogonal experimental methods when possible

By implementing these troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and experimental protocols, researchers can systematically address batch effects in chemogenomic studies, leading to more reproducible and reliable research outcomes.

In chemogenomics research, which integrates chemical and genomic data for drug discovery, batch effects are a pervasive technical challenge. These are variations in data unrelated to the biological phenomena under study but introduced by differences in experimental conditions. Left undetected and uncorrected, they can skew analytical results, lead to irreproducible findings, and ultimately misdirect drug development efforts. This guide addresses the common sources of these effects—namely, operators, reagent lots, and platform differences—providing researchers with actionable protocols for troubleshooting and correction.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common sources of batch effects in chemogenomics data? Batch effects arise from technical variations at multiple stages of experimentation. The most frequent sources include:

- Reagent Lots: Different manufacturing lots of calibrators, antibodies, and other reagents can have slight compositional variations, leading to shifts in measured results. This is particularly pronounced in immunoassays [9] [10].

- Platform and Instrument Differences: Data generated on different instrument models, from different manufacturers, or using different sequencing platforms (e.g., microarray vs. RNA-seq) can exhibit systematic variations [3] [5].

- Operator Variation: Differences in technique, sample handling, and protocol execution between personnel can introduce technical noise [8].

- Temporal and Laboratory Shifts: Experiments conducted at different times, on different days, or in different laboratory locations are subject to variations in environmental conditions and reagent degradation [3] [2].

2. How can I quickly check if my dataset has significant batch effects? Several visualization and quantitative methods can help detect batch effects:

- Visualization: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA), t-SNE, or UMAP plots to visualize your data. If samples cluster strongly by batch (e.g., sequencing run, reagent lot) instead of by biological condition, it indicates a batch effect [11] [2].

- Clustering: Generate heatmaps and dendrograms. If samples from the same batch cluster together irrespective of treatment, a batch effect is likely present [11].

- Quantitative Metrics: Employ metrics like the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) or others to objectively measure the degree of batch separation with less human bias [5] [11].

3. What is the difference between a biological signal and a batch effect? A biological signal is a variation in the data caused by the actual experimental conditions or phenotypes you are studying (e.g., disease state, drug treatment). A batch effect is a technical variation caused by the process of measuring the samples. The key challenge is that batch effects can be confounded with biological signals, for example, if all control samples were processed in one batch and all treated samples in another. Over-correction can remove genuine biological signals, manifesting as distinct cell types or treatment groups becoming incorrectly clustered together after correction [11].

4. My lab is changing a reagent lot for a key assay. What is the best practice for validation? A robust validation protocol involves a patient sample comparison, as quality control (QC) materials often lack commutability with patient samples [9] [10] [12].

- Establish Criteria: Define a critical difference (CD) based on clinical requirements or biological variation that represents the maximum acceptable change in patient results [9] [13].

- Select Samples: Choose 5-20 patient samples that span the assay's reportable range, with an emphasis on concentrations near medical decision limits [10] [13].

- Run Comparison: Test the selected samples using both the old and new reagent lots under identical conditions (same instrument, same day, same operator) [9].

- Analyze Data: Statistically compare the paired results against your pre-defined CD to decide if the new lot is acceptable [13].

5. Are some types of assays more prone to reagent lot variation than others? Yes. Immunoassays are generally more susceptible to lot-to-lot variation compared to general chemistry tests. This is because the production of immunoassay reagents involves the binding of antibodies to a solid phase, a process where slight differences in antibody quantity or affinity are inevitable between lots [9] [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Suspected Reagent Lot Variation

Symptoms:

- A sharp shift in internal quality control (IQC) results upon introducing a new reagent lot [10].

- Clinicians report unexpected or discrepant patient results that coincide with a lot change [9].

- A gradual, cumulative drift in patient results over multiple lot changes, even though individual lot validations passed [9] [10].

Solutions:

- Immediate Action: Perform a patient sample comparison between the old and new lots as described in the FAQ above [9] [13].

- Long-Term Monitoring: Implement a moving average (also known as an average of normals) system. This method monitors the mean of patient results in real-time and can detect small, systematic drifts that are not apparent in single lot-to-lot comparisons [9] [10].

- Categorize Assays: Adopt a risk-based approach. Group assays based on their historical performance. For stable assays, QC may suffice; for historically variable assays (e.g., hCG, troponin), mandatory patient comparisons with each lot change are recommended [9] [10].

Problem 2: Batch Effects in Multi-Omics or Multi-Center Studies

Symptoms:

- Strong batch clustering in PCA plots for data integrated from different labs, platforms, or time points [5] [11].

- Inability to reproduce findings when a different reagent batch or platform is used [3].

- High numbers of false positives or false negatives in differential expression analysis when batch and biological groups are confounded [3] [5].

Solutions:

- Experimental Design: The best solution is prevention. Whenever possible, process samples from different biological groups evenly across batches (balanced design) and use a randomized processing order [8].

- Use Reference Materials: Incorporate commercially available or community-developed reference materials (e.g., from projects like the Quartet Project) into every batch. The ratio-based method, which scales feature values in study samples relative to those of the concurrently profiled reference material, has been shown to be highly effective, especially in confounded scenarios [5].

- Computational Correction: Apply batch effect correction algorithms (BECAs). The choice of algorithm depends on your data type and the study design.

- For single-cell RNA-seq: Harmony, Seurat, and Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) are popular choices [8] [11].

- For bulk RNA-seq or other omics data: ComBat (empirical Bayes), limma's

removeBatchEffect, and the ratio-based method are widely used [5] [2]. - For microbiome data: Consider specialized methods like ConQuR, which handles zero-inflated count data [14].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a robust strategy for managing batch effects, from experimental design to data analysis:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating a New Reagent Lot (CLSI EP26-Based)

This protocol follows the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) EP26 guideline [13].

Stage 1: Setup (One-time setup for each analyte)

- Define Critical Difference (CD): Establish the maximum medically or analytically acceptable difference between reagent lots. This can be based on total allowable error (TEa), biological variation, or clinical decision limits [13].

- Determine Sample Size: Based on the desired statistical power, imprecision of the assay, and the CD, determine the number of patient samples (N). Typically, 5-20 samples are used [10] [13].

- Select Sample Concentration Range: Choose samples that cover the reportable range, with emphasis on medical decision points [10].

Stage 2: Evaluation (Performed for each new reagent lot)

- Sample Testing: Assay the selected N patient samples using both the current (old) and new reagent lots in parallel, using the same instrument and operator.

- Statistical Analysis: For each sample pair, calculate the difference between the old and new lot results. Compare these differences to the pre-defined CD.

- Acceptance Decision: If the differences for all (or a specified majority of) samples fall within the CD, the new lot is acceptable for use. If not, investigate with the manufacturer and reject the lot [9] [13].

Protocol 2: A Ratio-Based Batch Effect Correction for Multi-Batch Studies

This protocol is effective for multi-omics data when common reference materials are available [5].

- Experimental Design: In every batch of your study, include one or more aliquots of a well-characterized reference material (e.g., Quartet reference materials).

- Data Generation: Generate your omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics, etc.) for both the study samples and the reference material in each batch.

- Calculation: For each feature (e.g., gene, protein) in every study sample, transform the absolute measurement into a ratio relative to the average measurement of the reference material in the same batch.

- Formula:

Ratio(Sample) = Absolute_Value(Sample) / Mean_Absolute_Value(Reference_in_Batch)

- Formula:

- Data Integration: Use the resulting ratio-scale data for all downstream integrative analyses. This scaling effectively normalizes out batch-specific technical variations [5].

| Resource | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Reference Materials (e.g., Quartet Project) | Well-characterized, stable materials used to calibrate measurements across different batches and platforms, enabling the powerful ratio-based correction method [5]. |

| CLSI EP26 Guideline | Provides a standardized, statistically sound protocol for laboratories to validate new reagent lots, ensuring consistency in patient or research sample results [13]. |

| Batch Effect Correction Algorithms (BECAs) | Computational tools designed to remove technical variation from data post-hoc. Selection is data-specific (e.g., Harmony for scRNA-seq, ComBat for bulk genomics) [8] [5] [11]. |

| Moving Averages (Average of Normals) | A quality control technique that monitors the mean of patient results in real-time to detect long-term, cumulative drifts caused by serial reagent lot changes [9] [10]. |

| Source | Description | Typical Impact on Data |

|---|---|---|

| Reagent Lots | Variation between manufacturing batches of antibodies, calibrators, enzymes, etc. | Shifts in QC and patient sample results; can be sudden or a cumulative drift [9] [10]. |

| Platform Differences | Data generated on different instruments (e.g., sequencers, mass spectrometers) or technology platforms. | Systematic differences in sensitivity, dynamic range, and absolute values, hindering data integration [3] [5]. |

| Operator Variation | Differences in sample handling, pipetting technique, or protocol execution by different personnel. | Increased technical variance and non-systematic noise [8]. |

| Temporal / Run Effects | Variations due to experiment run date, instrument calibration drift, or environmental changes over time. | Strong clustering of samples by processing date or sequencing run in multivariate analysis [3] [2]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Selected Batch Effect Correction Algorithms

| Algorithm | Typical Use Case | Key Principle | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harmony | Single-cell genomics (e.g., scRNA-seq) | Iterative clustering and integration based on PCA embeddings. Fast and scalable [8] [11]. | May be less scalable for very large datasets according to some benchmarks [11]. |

| ComBat / ComBat-seq | Bulk genomics (Microarray, RNA-seq) | Empirical Bayes framework to adjust for location and scale shifts between batches [2]. | Assumes a parametric model; ComBat-seq is designed for count data [2]. |

| Ratio-Based Scaling | Multi-omics with reference materials | Scales feature values relative to a common reference sample processed in the same batch [5]. | Requires careful selection and consistent use of a high-quality reference material. Highly effective in confounded designs [5]. |

| ConQuR | Microbiome data | Conditional quantile regression for zero-inflated, over-dispersed count data. Non-parametric [14]. | Specifically designed for the complex distributions of microbial read counts [14]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary causes of batch effects in chemogenomic data? Batch effects are technical, non-biological variations introduced when samples are processed in different groups or "batches." Key causes include differences in reagent lots, sequencing platforms, personnel handling the samples, equipment used, and the timing of experiments [8] [15]. In mass spectrometry-based proteomics, these variations can stem from multiple instrument batches, operators, or collaborating labs over long data-generation periods [16].

2. How can I detect the presence of batch effects in my dataset? Several visualization and quantitative methods can help detect batch effects:

- Visualization: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA), t-SNE, or UMAP plots. If the data points cluster strongly by batch rather than by the expected biological conditions (e.g., case vs. control), a batch effect is likely present [15] [11].

- Quantitative Metrics: Employ metrics like the k-nearest neighbor batch effect test (kBET), adjusted rand index (ARI), or normalized mutual information (NMI) to objectively measure the degree of batch separation before and after correction [15].

3. Why might batch effects lead to an increase in false discoveries? Batch effects can confound biological signals, making technical variations appear as biologically significant findings. This is particularly problematic in high-dimensional data where features (like genes or proteins) are highly correlated. In such cases, standard False Discovery Rate (FDR) control methods like Benjamini-Hochberg can counter-intuitively report a high number of false positives, even when all null hypotheses are true [17]. This happens because dependencies between features can cause false findings to occur in large, correlated groups, misleading researchers [17].

4. What are the signs that my batch effect correction has been too aggressive (overcorrection)? Overcorrection occurs when technical variation is removed at the expense of genuine biological signal. Key signs include:

- Distinct biological cell types or conditions are clustered together on a UMAP or t-SNE plot [11].

- A significant portion of identified cluster markers are genes with widespread high expression (e.g., ribosomal genes) rather than specific markers [15] [11].

- A complete overlap of samples from very different biological conditions, indicating the loss of meaningful biological distinction [11].

- The absence of expected canonical markers for cell types known to be in the dataset [15].

5. At which data level should I perform batch-effect correction in proteomics data? Benchmarking studies suggest that for mass spectrometry-based proteomics, performing batch-effect correction at the protein level is the most robust strategy. This approach proves more effective than correcting at the precursor or peptide levels, as the protein quantification process itself can interact with and influence the performance of batch-effect correction algorithms [16].

6. How does sample size and imbalance affect the reproducibility of my analysis? In gene set analysis, larger sample sizes generally lead to more reproducible results. However, the rate of improvement varies by method [18]. Furthermore, sample imbalance—where different batches have different numbers of cells or proportions of cell types—can substantially impact the results of data integration and lead to misleading biological interpretations [11]. It is crucial to account for this imbalance during experimental design and analysis.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting for False Discoveries

Problem: After analysis, a high number of statistically significant findings are detected, but independent validation fails, suggesting false discoveries.

Investigation & Solution Protocol:

Assess Feature Dependencies:

- Action: Calculate the correlation matrix between the top significant features (e.g., genes, proteins).

- Rationale: Strong correlations between features can violate the assumptions of FDR-control methods, leading to clusters of false positives [17].

- Tool: Standard statistical software (R, Python).

Employ a Synthetic Null:

- Action: Shuffle the labels (e.g., case/control) in your dataset and re-run your primary analysis. Repeat this process multiple times (permutation testing).

- Rationale: This creates a scenario where no true biological associations exist. Any significant findings reported are, by definition, false positives. This helps estimate the true False Discovery Proportion (FDP) in your actual data [17].

- Tool: Custom scripting to automate permutation tests.

Utilize LD-Aware or Advanced Correction Methods:

- Action: If analyzing genetic data (e.g., eQTLs), avoid global FDR correction. Instead, use methods designed for correlated genomic data, such as linkage disequilibrium (LD)-aware permutation testing or hierarchical procedures [17].

- Rationale: These methods are specifically designed to handle the dependencies inherent in genomic data, providing more reliable error control [17].

- Tool: Packages like

MatrixEQTLwith permutation options, or other QTL-specific toolkits.

Guide 2: Ensuring Reproducibility After Batch Correction

Problem: Analysis results are inconsistent when the experiment is repeated or when re-analyzing the same data with different parameters.

Investigation & Solution Protocol:

Benchmark Correction Strategies:

- Action: Systematically test different batch-effect correction algorithms (BECAs) and data levels on your specific data type. For proteomics, this means comparing precursor-, peptide-, and protein-level correction [16].

- Rationale: The performance of BECAs is context-dependent. A method that works for one dataset may not be optimal for another. Protein-level correction has been shown to be particularly robust in proteomics [16].

- Tool: Benchmarking frameworks that use metrics like coefficient of variation (CV) and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Example BECAs include ComBat, Harmony, and Ratio-based methods [16].

Quantify Reproducibility with Technical Replicates:

- Action: If available, use technical replicates (the same biological sample processed multiple times) to assess the consistency of your bioinformatics tools.

- Rationale: "Genomic reproducibility" is the ability of a tool to yield consistent results across technical replicates from different sequencing runs. Tools that are sensitive to read order or use stochastic algorithms can introduce unwanted variation [19].

- Tool: The Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) consortium or MAQC/SEQC projects provide reference materials for assessing reproducibility [19].

Document the Computational Environment Exhaustively:

- Action: Record the exact software versions, parameters, and random seeds used for all analyses, including batch correction.

- Rationale: Reproducibility requires the ability to precisely repeat the computational procedures. Stochastic algorithms can produce different results unless a seed is set [19] [20].

- Tool: Electronic laboratory notebooks (eLNs), Jupyter notebooks, and containerization technologies (Docker, Singularity) [20].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating Batch Effect Correction

This table summarizes key metrics used to assess the success of batch effect correction, helping to minimize false discoveries and improve reproducibility.

| Metric Name | Brief Description | Ideal Value | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| kBET [15] | k-nearest neighbor batch effect test; tests if local neighborhoods of cells are well-mixed across batches. | Closer to 1 | Single-cell RNA-seq, general high-dimensional data. |

| ARI [15] | Adjusted Rand Index; measures the similarity between two clustering outcomes, e.g., before and after correction. | Closer to 1 | Any clustered data. |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) [16] | Measures the dispersion of data points; used to assess technical variation within replicates across batches. | Lower values | Proteomics, any data with technical replicates. |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) [16] | Evaluates the resolution in differentiating known biological groups after correction using PCA. | Higher values | General high-dimensional data. |

| Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) [15] | Measures the mutual dependence between cluster assignments and batch labels. | Closer to 0 (after correction) | Single-cell RNA-seq, general high-dimensional data. |

Table 2: Benchmarking of Common Batch Effect Correction Algorithms

This table provides a comparative overview of popular batch effect correction methods based on published benchmarking studies.

| Method | Principle | Key Findings from Benchmarks |

|---|---|---|

| Harmony [15] [11] | Iterative clustering in PCA space and cluster-specific correction. | Recommended for its fast runtime and good performance in single-cell genomics [11]. |

| Seurat Integration [8] [11] | Uses Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) and Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNNs) as anchors. | Good performance but has lower scalability compared to other methods [11]. |

| ComBat [16] | Empirical Bayes method to modify mean and variance shifts across batches. | Widely used but performance can be influenced by the quantification method in proteomics [16]. |

| Ratio [16] | Scales feature intensities in study samples based on a universal reference material. | A simple, universally effective method, especially when batch effects are confounded with biological groups [16]. |

| LIGER [15] | Integrative non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) to factorize batches. | Effective for identifying shared and dataset-specific factors. |

| scANVI [11] | A deep generative model (variational autoencoder) that uses labeled data. | In one comprehensive benchmark, it performed the best among tested methods [11]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating Batch Effect Correction Using a Balanced vs. Confounded Design

Application: This methodology is used to rigorously benchmark the performance of different batch-effect correction algorithms (BECAs) under realistic conditions, including when batch is perfectly confounded with the biological group of interest [16].

Materials:

- Reference materials with known biological truths (e.g., Quartet project reference materials) [16].

- Raw feature-level data (e.g., precursor or peptide intensities from mass spectrometry).

- Access to multiple BECAs (e.g., ComBat, Harmony, Ratio).

- Statistical computing environment (R/Python).

Procedure:

- Dataset Design:

- Balanced Scenario (Quartet-B/Simulated-B): Distribute all biological sample groups equally across all technical batches.

- Confounded Scenario (Quartet-C/Simulated-C): Deliberately confound one biological group with one batch (e.g., all "Case" samples are in Batch 1, all "Control" in Batch 2) [16].

- Apply Correction Strategies:

- Apply each BECA (e.g., Combat, Median centering, Ratio) at different data levels (precursor, peptide, protein) if applicable.

- Generate Evaluation Matrices:

- Aggregate the corrected data to the final analysis level (e.g., protein-level abundance matrices).

- Performance Assessment:

- Feature-based metrics: Calculate the Coefficient of Variation (CV) within technical replicates for each feature. Lower CV indicates better removal of technical noise.

- Sample-based metrics:

- Calculate the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to see if biological groups are better separated.

- Perform Principal Variance Component Analysis (PVCA) to quantify the proportion of variance explained by biological factors versus batch factors after correction [16].

Protocol: Assessing the Impact of Sample Size on Reproducibility in Gene Set Analysis

Application: To determine how the number of biological replicates affects the consistency and specificity of gene set enrichment results, aiding in robust experimental design [18].

Materials:

- A large original case-control gene expression dataset (e.g., from GEO or ArrayExpress) with many samples per group (>50) [18].

- Software for running multiple gene set analysis methods (e.g., GSEA, GAGE, CAMERA).

Procedure:

- Generate Replicate Datasets:

- For a range of sample sizes (e.g., n = 3 to 20 per group), randomly select 'n' samples from the control group and 'n' from the case group of the original large dataset without replacement.

- Repeat this process multiple times (e.g., m=10) for each sample size 'n' to create multiple replicate datasets [18].

- Run Gene Set Analysis:

- Apply a panel of gene set analysis methods (e.g., PAGE, GSEA, ORA) to each of the replicate datasets.

- Measure Reproducibility:

- For each method and sample size, measure how consistent the top-ranking gene sets are across the different replicate datasets. This can be done by calculating the Jaccard index or overlap coefficient of significant gene sets between replicates.

- Measure Specificity (False Positives):

- Generate negative control datasets by randomly selecting all samples from only the control group of the original dataset and artificially splitting them into "case" and "control" groups. Any gene set called significant in this analysis is a false positive.

- Run the gene set analysis methods on these negative control datasets of various sizes and count the number of reported gene sets (false positives) [18].

Experimental Workflow and Relationships

Batch Effect Correction and Evaluation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Context of Batch Effect Management |

|---|---|

| Reference Materials (e.g., Quartet Project) | Provides standardized, well-characterized samples from the same source to be profiled across different batches and labs. Essential for benchmarking batch-effect correction methods and monitoring data quality [16]. |

| Technical Replicates | Multiple sequencing/MS runs of the same biological sample. Used to assess and account for variability arising from the experimental process itself, forming the basis for evaluating "genomic reproducibility" [19]. |

| Universal Reference Sample | A single reference sample (e.g., pooled from many sources) profiled concurrently with all study samples. Enables Ratio-based batch correction, where study sample feature intensities are scaled by the reference's intensities [16]. |

| Electronic Laboratory Notebook (ELN) / Jupyter Notebook | Digital tools for exhaustive documentation of all experimental and computational procedures, including software versions, parameters, and random seeds. Critical for ensuring computational reproducibility [20]. |

| Batch Effect Correction Algorithms (BECAs) | Software tools (e.g., Harmony, ComBat, Seurat) specifically designed to identify and remove non-biological technical variation from data, thereby harmonizing datasets from different batches [8] [15] [16]. |

| Quantitative Evaluation Metrics | Algorithms and scores (e.g., kBET, ARI, CV) that provide an objective, numerical assessment of the success of batch effect correction, reducing reliance on subjective visualization [15] [16]. |

A Technical Support Center for Chemogenomic Research

This guide provides troubleshooting support for researchers addressing the critical challenge of batch effects in chemogenomic data. Understanding the distinction between balanced and confounded experimental scenarios is fundamental to selecting the correct data correction strategy and ensuring the validity of your results.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between a balanced and a confounded experimental scenario?

In the context of experimental design, particularly for batch effect correction, this distinction is paramount.

- Balanced Scenario: A balanced design is one where the biological groups of interest (e.g., treatment vs. control) are evenly distributed across all technical batches [5]. This distribution allows statistical models to separate the technical noise (batch effects) from the true biological signal more effectively. Many batch-effect correction algorithms perform well under these conditions [5].

- Confounded Scenario: A confounded design is one where the biological factor you wish to study is completely mixed up or "confounded" with a technical factor, most commonly the batch [5]. For instance, if all control samples were processed in Batch 1 and all treatment samples in Batch 2, it becomes statistically impossible to distinguish whether the differences observed are due to the treatment or the batch in which the samples were processed [5]. This scenario is high-risk and requires specific correction approaches.

The following diagram illustrates the structural difference between these two experimental setups:

Troubleshooting Guide 1: My experimental design is confounded. How can I correct for batch effects?

A confounded scenario is one of the most challenging problems in data integration. Standard correction methods often fail because they cannot tell the difference between batch and biological group, potentially removing the real signal you are trying to find [5]. The most effective strategy involves the use of reference materials.

Solution: Implement a Reference-Material-Based Ratio Method [5].

Experimental Protocol: Ratio-Based Scaling

- Select a Reference Material: Choose a well-characterized and stable reference sample. In chemogenomics, this could be a pooled cell line sample or a commercial reference standard. This same reference material must be used across all your batches [5].

- Concurrent Profiling: In every experimental batch, profile your study samples and one or more replicates of your chosen reference material alongside them [5].

- Data Transformation: For each feature (e.g., gene transcript, protein abundance) in each study sample, transform the absolute measurement into a ratio relative to the average measurement of that same feature in the reference material replicates from the same batch [5].

Ratio = Feature_Study_Sample / Feature_Reference_Material

- Data Integration: Use these ratio-scaled values for all downstream analyses and data integration. This process effectively re-baselines all batches to a common standard, mitigating the confounded batch effects [5].

The workflow below outlines this corrective process:

FAQ 2: What is a confounding variable and how does it relate to a confounded design?

A confounding variable is a third, often unmeasured, factor that is related to both the independent variable (e.g., a drug treatment) and the dependent variable (e.g., cell viability) [21] [22]. It creates a spurious association that can trick you into thinking your treatment caused the outcome when, in reality, the confounder did [21] [23].

- Relation to Design: A "confounded experimental design" is a formal manifestation of this problem, where the batch (the technical variable) acts as the confounding variable. It affects your measurements (the dependent variable) and is also perfectly correlated with your biological groups (the independent variable) [5].

Troubleshooting Guide 2: My PCA plot shows samples clustering by batch, not by treatment group. What should I do?

This is a classic symptom of significant batch effects. Your first step is to diagnose whether your design is balanced or confounded, as the solution differs.

Solution: Follow this diagnostic and correction workflow.

FAQ 3: Why is a balanced design considered the gold standard?

A balanced design is considered robust because it proactively decouples technical variation from biological variation through intelligent experimental planning [24] [5].

- Independence: It ensures that the variable "batch" is independent of the variable "treatment group." This independence allows statistical models to cleanly estimate and subtract the batch effect without significantly harming the biological signal of interest [24].

- Power: By reducing noise, a balanced design increases the statistical power of your experiment, making it easier to detect true positive effects without needing to dramatically increase your sample size [24] [5].

Comparison of Batch Effect Correction Methods

The table below summarizes the performance and applicability of common batch effect correction algorithms (BECAs) in different experimental scenarios, based on large-scale multiomics assessments [5].

| Method / Algorithm | Principle | Best For | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio-Based Scaling | Scales feature values relative to a concurrently profiled reference material [5]. | Confounded scenarios where batch and group are perfectly mixed [5]. | Requires planning and the cost of running reference samples in every batch [5]. |

| ComBat / ComBat-seq | Empirical Bayes framework to adjust for batch effects [2] [25]. | Balanced scenarios with RNA-seq count data [5]. | Can perform poorly or remove biological signal in strongly confounded designs [5]. |

| Harmony | Iterative clustering and scaling based on principal components (PCA) [5]. | Balanced scenarios, including single-cell data [5]. | Performance not guaranteed for all omics types; may struggle with confounded designs [5]. |

| Include Batch as Covariate | Adds 'batch' as a fixed effect in a linear model during differential analysis (e.g., in DESeq2, limma) [2]. | Balanced scenarios as a straightforward statistical control [2]. | Fails in confounded designs due to model matrix singularity; the effect of batch and group cannot be disentangled [5]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials essential for designing robust chemogenomic experiments, especially those aimed at mitigating batch effects.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|

| Reference Material (RM) | A stable, well-characterized sample (e.g., pooled cell lines, commercial standard) profiled in every batch to serve as an internal control for ratio-based correction methods [5]. |

| Platform-Specific Kits | Using the same lots of library preparation kits, reagents, and arrays across all batches minimizes a major source of technical variation [3] [26]. |

| Sample Tracking System | A robust system (e.g., LIMS) to meticulously track sample provenance, batch, and processing history is non-negotiable for diagnosing and modeling batch effects [3]. |

A Practical Toolkit: Batch Effect Correction Methods from Traditional to AI-Driven

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between data normalization and batch effect correction?

Both are preprocessing steps, but they address different technical variations. Normalization primarily corrects for variations in sequencing depth across cells, differences in library size, and amplification biases caused by gene length. In contrast, batch effect correction specifically addresses technical variations arising from different sequencing platforms, reagent lots, processing times, or different laboratory conditions [15].

Q2: My data still shows batch effects after running ComBat. What could be wrong?

Several factors could lead to suboptimal batch correction:

- Incorrect Data Preprocessing: ComBat requires that your data is already preprocessed and normalized gene-wise before application. Ensure proper normalization has been performed [27].

- Data Format Mismatch: Using a method designed for a different data type can cause problems. For example, applying the standard ComBat (designed for microarrays) directly to RNA-seq count data without transformation, or using methods assuming normal distributions on beta-value methylation data which is bounded between 0 and 1 [28].

- Confounded Design: If your experimental design has missing or an unbalanced proportion of treatments/controls from a batch, this risks removal of biological signal during batch correction [27].

Q3: When should I use a reference batch for correction, and how do I choose it?

Reference batch adjustment is particularly useful when you want to align all datasets to a specific gold-standard batch, such as data from a central lab or a specific sequencing platform. In the ComBat-ref method, the batch with the smallest dispersion is selected as the reference, which helps preserve statistical power in downstream differential expression analysis [29].

Q4: What are the key signs that my batch correction has been too aggressive (overcorrection)?

Overcorrection can remove biological signal along with technical noise. Key signs include [15]:

- A significant portion of cluster-specific markers comprises genes with widespread high expression (e.g., ribosomal genes).

- Substantial overlap among markers specific to different clusters.

- Notable absence of expected canonical markers for known cell types present in the dataset.

- Scarcity of differential expression hits in pathways expected based on the experimental conditions.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Batch Correction Performance with ComBat-seq on RNA-seq Data

Symptoms: Batch effects remain visible in PCA or UMAP plots after running ComBat-seq [30].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Confirm Proper Input Data Type: ComBat-seq is designed for raw RNA-seq count data. Using normalized data can lead to suboptimal results.

- Verify Preprocessing Pipeline: Ensure you are not providing a

DESeqTransformobject or other already-transformed data. The input should be a raw count matrix [30]. - Follow a Validated Workflow:

- Create a

DESeqDataSetobject from your raw count matrix. - Apply a variance-stabilizing transformation (

vst) or regularized-log transformation (rlog). - Use the transformed data for

plotPCAto assess correction [30].

- Create a

- Consider Alternative Methods: If performance remains poor, try other established methods like the

removeBatchEffectfunction from thelimmapackage, or newer algorithms like Harmony or Seurat 3 for single-cell data [30] [31].

Problem 2: Applying Gaussian-Based Methods to Non-Normal Data

Symptoms: Inaccurate correction or distorted data distributions when using methods like ComBat on DNA methylation (β-values) or count data.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Identify Your Data Distribution:

- Use Distribution-Specific Methods:

- For β-values, use ComBat-met, which employs a beta regression framework tailored for methylation data [28].

- For RNA-seq counts, use ComBat-seq or ComBat-ref, which model data with a negative binomial distribution [29].

- Alternatively, transform your data to a scale where the Gaussian assumption is more reasonable (e.g., M-values for methylation data, log-CPM for counts) before using standard ComBat [28].

Problem 3: Choosing the Right Batch Correction Method for Your Omics Data

Different data types and experimental designs require specific correction tools. The table below summarizes recommended methods.

Table 1: Batch Effect Correction Method Selection Guide

| Data Type | Recommended Methods | Key Characteristics | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microarray Gene Expression | ComBat [27], limma removeBatchEffect [32] |

Empirical Bayes framework (ComBat), linear models with precision weights (limma). | Standard choice for normalized, continuous intensity data. |

| Bulk RNA-seq | ComBat-seq [29], ComBat-ref [29], limma (voom transformation) [32] |

Preserves integer count data (ComBat-seq), reference batch alignment for high power (ComBat-ref). | ComBat-ref shows superior power when batch dispersions vary [29]. |

| DNA Methylation (β-values) | ComBat-met [28] | Beta regression model designed for [0,1] bounded data. | Avoid naive application of Gaussian-based methods [28]. |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq | Harmony [31], Seurat 3 [31], LIGER [31] | Handles high sparsity and dropout rates; fast runtime (Harmony). | Benchmarking shows these are top performers for scRNA-seq integration [31]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Batch Effect Correction for RNA-seq using ComBat-ref

Purpose: To adjust for batch effects in RNA-seq count data while maximizing statistical power for subsequent differential expression analysis.

Workflow Overview:

Title: ComBat-ref workflow for RNA-seq batch correction.

Detailed Methodology [29]:

- Input: Start with a raw RNA-seq count matrix (genes x samples).

- Dispersion Estimation: For each batch, pool gene count data to estimate a batch-specific dispersion parameter (λi).

- Reference Batch Selection: Select the batch with the smallest dispersion parameter as the reference batch.

- Model Fitting: Fit a generalized linear model (GLM) with a negative binomial distribution for each gene:

log(μ_ijg) = α_g + γ_ig + β_cjg + log(N_j)where:μ_ijgis the expected count for genegin samplejfrom batchi.α_gis the global background expression for geneg.γ_igis the effect of batchion geneg.β_cjgis the effect of the biological conditioncof samplejon geneg.N_jis the library size for samplej.

- Data Adjustment: Adjust the count data from non-reference batches towards the reference batch. The adjusted gene expression level is computed as:

log(μ~_ijg) = log(μ_ijg) + γ_1g - γ_ig(for batchi≠ 1, the reference). The dispersion for the adjusted data is set to that of the reference batch (λ~i = λ1). - Output: An adjusted count matrix, suitable for downstream analysis with tools like DESeq2 or edgeR.

Protocol 2: Integrating Mean-Centering in a Preprocessing Workflow

Purpose: To center data relative to a reference point, a crucial step before many multivariate analysis techniques like PCA.

Workflow Overview:

Title: Decision workflow for data centering.

Detailed Methodology [33]:

- Order of Operations: Centering is typically one of the last steps in a preprocessing sequence, performed after other methods like scaling or filtering but before the main multivariate analysis.

- Centering Type Selection:

- Mean-Centering: Calculates the mean of each variable (column) across all samples and subtracts it. This makes the data relative to the "average sample." It is essential for interpreting PCA eigenvalues as captured variance. Formula: X_c = X - 1x̄ (where 1 is a vector of ones and x̄ is the mean vector) [33].

- Median-Centering: A robust alternative where the median of each column is subtracted. This is less influenced by outlier samples.

- Class-Centering: Used when samples belong to known groups (e.g., different subjects). It centers each group to its own local mean, effectively removing the between-group variation and focusing analysis on variance within groups [33].

- Application: The centered data is then used for downstream modeling (e.g., PCA, PLS). Interpretation of loadings and samples in these models is done relative to the chosen reference point (e.g., the global mean for mean-centered data).

Performance Benchmarking

The performance of batch correction methods can be evaluated using simulation studies and real data benchmarks. Key metrics include True Positive Rate (TPR), False Positive Rate (FPR), and the ability to recover biological signals.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of RNA-seq Batch Correction Methods in Simulation

| Method | True Positive Rate (TPR) | False Positive Rate (FPR) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat-ref | Highest, comparable to data without batch effects in many scenarios [29]. | Controlled, especially when using FDR [29]. | Superior sensitivity without compromising FPR; performs well even with high batch dispersion [29]. |

| ComBat-seq | High when batch dispersions are similar [29]. | Controlled [29]. | Power drops significantly compared to batch-free data when batch dispersions vary [29]. |

| NPMatch | Good [29]. | Can be >20% in some scenarios [29]. | May exhibit high false positive rates [29]. |

| 'One-step' approach (batch as covariate) | Varies | Varies | Performance highly dependent on the model and data structure [28]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

This section lists key computational tools and their functions for implementing the discussed batch correction methods.

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Batch Effect Correction

| Tool / Package | Function | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| sva R package | Contains ComBat and ComBat-seq functions. |

Adjusting batch effects in microarray and RNA-seq data. |

| limma R package | Provides removeBatchEffect function and the voom method for RNA-seq. |

Differential expression analysis and batch correction for various data types. |

| Harmony R package | Fast and effective integration of single-cell data. | Removing batch effects from single-cell RNA-seq datasets. |

| Seurat R package | Comprehensive toolkit for single-cell analysis, including integration methods. | Data integration and batch correction for single-cell genomics. |

| betareg R package | Fits beta regression models. | Core statistical engine for the ComBat-met method. |

In chemogenomic research, where the goal is to understand the complex interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems, batch effects are a formidable source of technical variation that can confound true biological signals [3]. These non-biological variations, introduced during different experimental runs, by different technicians, or using different reagent lots, can lead to misleading outcomes, reduced statistical power, and irreproducible findings [3] [5]. The challenge is particularly acute in large-scale, multiomics studies that integrate data from transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics platforms [3] [7]. This technical support guide introduces the ratio-based method using common reference materials as a powerful strategy to mitigate these effects, ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of your chemogenomic data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the ratio-based method for batch effect correction? The ratio-based method is a technique that scales the absolute feature values (e.g., gene expression levels) of study samples relative to the values of a common reference material that is profiled concurrently in every batch [34] [5]. By converting raw measurements into ratios, this method effectively anchors data from different batches to a stable, internal standard, thereby minimizing technical variations.

2. Why should I use a ratio-based method over other algorithms like ComBat or Harmony? While many batch-effect correction algorithms (BECAs) exist, their performance is highly scenario-dependent. The ratio-based method has been shown to be particularly effective in confounded scenarios where biological groups of interest are completely processed in separate batches [5]. In such cases, which are common in longitudinal studies, other methods may inadvertently remove the biological signal along with the batch effect. The ratio method provides a robust and transparent alternative.

3. What are the ideal characteristics for a common reference material? An effective reference material should be:

- Stable and Homogeneous: It must be consistent across vials and over time to serve as a reliable anchor.

- Commutable: Its behavior should mimic that of your study samples across the various analytical platforms used.

- Well-characterized: Its profile should be extensively documented across multiple omics levels. Projects like the Quartet Project have developed such reference materials from characterized cell lines for this purpose [5].

4. Can the ratio method be applied to all types of omics data? Yes, evidence shows that the ratio-based scaling approach is broadly applicable across different omics types, including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data [5]. Its simplicity and effectiveness make it a versatile tool for multiomics integration.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inability to Distinguish Biological Signal from Batch Effect

Symptoms:

- Samples cluster strongly by batch instead of by treatment or disease group in PCA plots.

- Poor performance in downstream predictive models when applied to new batches.

- Inability to reproduce findings from a previous batch.

Solutions:

- Implement a Common Reference Material: Introduce a stable reference material (e.g., a well-characterized cell line or a commercial standard) to be included in every experimental batch from the start.

- Apply Ratio Transformation: For each batch, transform your data. The formula for a given feature in a study sample is:

Ratio = Value_study_sample / Value_reference_materialThis can be done on a log-scale if the data is log-normally distributed. - Validate with Balanced Designs: Whenever possible, design experiments to include replicates of biological conditions across multiple batches. This allows you to assess the success of the correction.

Problem: Over-Correction or Loss of Biological Signal

Symptoms:

- Known biological differences between sample groups disappear after correction.

- All batches are merged into a single, undifferentiated cluster.

Solutions:

- Verify the Reference Material: Ensure the reference material itself is not driving the biology. It should be representative but not identical to any single study group.

- Check for Confounding: Acknowledge that in severely confounded designs (where one batch contains only "control" and another only "treatment"), no statistical method can perfectly disentangle the effects. The ratio method is your best option here [5].

- Benchmark Performance: Use quantitative metrics (see below) to ensure that after correction, biological groups are distinct while batch differences are minimized.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and correcting for batch effects using the ratio-based method.

Performance Metrics and Data Presentation

Objective assessment is key to successful batch effect correction. The following metrics, derived from large-scale multiomics studies, can be used to evaluate the performance of the ratio-based method against other algorithms.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Batch Effect Correction Algorithms in Multiomics Data [5]

| Algorithm | Primary Approach | Performance in Balanced Scenarios | Performance in Confounded Scenarios | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio-Based | Scales data relative to a common reference material | Excellent | Superior | Requires concurrent profiling of reference material |

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes framework | Good | Poor | Can over-correct in confounded designs |

| Harmony | Iterative PCA-based integration | Good | Poor | Struggles with strong batch-group confounding |

| SVA | Surrogate variable analysis | Good | Poor | Risk of removing biological signal |

| RUV (RUVg, RUVs) | Uses control genes/factors | Variable | Variable | Dependent on quality of control features |

| BMC | Per-batch mean centering | Good | Poor | Removes batch mean but not variance |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Batch Effect Correction [5]

| Metric | Description | Interpretation | Target Outcome after Correction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Measures separation of biological groups | Higher values indicate better preservation of biological signal | Increased SNR |

| Relative Correlation (RC) | Measures consistency of fold-changes with a gold-standard reference | Values closer to 1 indicate higher data quality and reproducibility | RC closer to 1.0 |

| Classification Accuracy | Ability to cluster samples by correct biological origin (e.g., donor) | Higher accuracy indicates successful integration without signal loss | High Accuracy |

| Matthew's Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | A balanced measure of classification quality, robust to class imbalance | Values closer to 1 indicate better and more reliable clustering | MCC closer to 1.0 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Ratio-Based Correction for a Transcriptomics Experiment

Objective: To remove batch effects from a multi-batch RNA-seq dataset using a common reference material.

Materials:

- RNA-seq datasets from multiple batches

- Data from the common reference material (e.g., Quartet Reference Material D6) profiled in each batch [5]

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Ensure all datasets (study samples and reference samples) have been processed through the same bioinformatic pipeline (e.g., alignment, quantification). Normalize the data using a standard method like TPM or FPKM.

- Ratio Calculation: For each gene i in each study sample j from batch k, calculate the ratio-adjusted value:

Ratio_ij = Value_ij / Mean(Value_iD6)whereMean(Value_iD6)is the average expression of gene i across the technical replicates of the reference material D6 in batch k. - Data Transformation (Optional): Log-transform the ratio values (e.g., log2(Ratio_ij)) for downstream statistical analyses that assume normally distributed data.

- Validation: Generate a PCA plot using the ratio-corrected data. Successful correction is indicated by the clustering of samples by their biological group (e.g., donor, treatment) rather than by batch.

Protocol 2: Objective Validation Using Balanced and Confounded Study Designs

Objective: To benchmark the performance of the ratio-based method against other BECAs under controlled conditions.

Materials:

- A multiomics dataset with known ground truth, such as data from the Quartet Project, where samples from a family quartet (D5, D6, F7, M8) are profiled across many batches [5].

Methodology:

- Dataset Creation:

- Balanced Scenario: Randomly select an equal number of samples from each biological group (D5, F7, M8) from each available batch. Designate D6 as the reference.

- Confounded Scenario: Allocate specific batches to contain replicates of only one biological group (e.g., Batch 1 has only D5, Batch 2 has only F7, etc.), simulating a worst-case, confounded design.

- Apply BECAs: Process both datasets using the ratio-based method and other algorithms (e.g., ComBat, Harmony).

- Evaluate Performance: Calculate the metrics listed in Table 2 for each method and scenario.

- Use SNR to measure biological group separation.

- Use classification accuracy to assess if samples cluster by their correct donor.

- Conclusion: The method that maintains high SNR and classification accuracy in both balanced and confounded scenarios is the most robust. Studies have demonstrated the ratio-based method excels in this test [5].

The workflow for this benchmarking protocol is detailed below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials for Ratio-Based Batch Effect Correction

| Item Name | Function / Description | Application in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Quartet Reference Materials | A suite of publicly available, multiomics reference materials derived from four related cell lines. Provides a well-characterized ground truth for method validation and application [5]. | Serves as the ideal common reference material for transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics studies. Enables cross-platform and cross-laboratory data integration. |

| Common Reference Sample (CRM) | Any stable, homogeneous, and commutable biological material that can be aliquoted and profiled repeatedly. | Processed concurrently with study samples in every batch to provide the denominator for the ratio calculation, anchoring the data. |

| Reference Material Database (e.g., BioSample) | Public repositories containing metadata and data for biological source materials used in experiments [35]. | A resource for discovering and selecting appropriate reference materials for a given study type or organism. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Harmony Integration Troubleshooting

Problem 1: Error in names(groups) <- "group" during HarmonyIntegration in Seurat

- Error Message:

Error in names(groups) <- "group" : attempt to set an attribute on NULL.[36] - Description: This error occurs when using

IntegrateLayerswithHarmonyIntegrationon a subsetted Seurat object. The issue is often related to the active cell identities (Idents) of the object. [36] - Solution:

- Before subsetting, ensure your active ident is set correctly. The error may occur if you have changed the active ident from the default

seurat_clustersto another metadata column (e.g.,RNA_snn_res.0.3). [36] - Explicitly set the

group.by.varsparameter in theIntegrateLayersfunction to specify the metadata column containing your batch information. [36] - Verify that the metadata column you are using for grouping exists and is correctly formatted in the subsetted object.

- Before subsetting, ensure your active ident is set correctly. The error may occur if you have changed the active ident from the default

Problem 2: Unexpected Results from Disconnected AI Systems

- Description: In enterprise IT, a common failure mode is when multiple, independent AI systems (e.g., for ticket routing, asset management, software optimization) provide uncoordinated and conflicting recommendations for the same underlying issue, leading to operational chaos and delayed resolutions. [37] This conceptual parallel in data analysis occurs when different batch-effect correction tools are applied in an uncoordinated manner across different parts of a dataset.

- Solution:

- Unified Analysis Platform: Move away from applying multiple, siloed integration tools. Instead, use a unified platform or a carefully designed workflow that allows different modules to share information. [37]

- Centralized Data Access: Ensure that the integration algorithm has access to all relevant data sources and metadata to make a globally consistent correction, rather than a local, context-blind one. [37]

Seurat Integration Troubleshooting

Problem 1: FindIntegrationAnchors is Taking an Extremely Long Time

- Description: The standard Seurat integration process, particularly the

FindIntegrationAnchorsfunction using CCA (Canonical Correlation Analysis), is computationally intensive and can run for days on large datasets (e.g., >100 samples, ~630K cells). [38] [39] - Solution:

- Increase Computational Resources: Allocate more CPU cores and RAM. Note that memory usage often increases with the number of cores used. [39]

- Use Sketching: The Seurat v5 workflow includes a

SketchDatafunction, which down-samples each dataset to a manageable number of cells (e.g., 5,000) for a computationally cheaper and faster integration. The final integrated model is then projected onto the full dataset. [38] - Switch Integration Methods:

Problem 2: Failure in Integration after Subsetting

- Description: An integration pipeline that worked on a full object fails after subsetting the object to a specific cluster (e.g., CD4 T cells) for sub-clustering. [36]

- Solution:

- Ensure all necessary pre-processing steps (

NormalizeData,FindVariableFeatures,ScaleData,RunPCA) are repeated on the subsetted object before attempting integration. [36] - Verify that the cell identities and metadata used to define the batches for integration are still present and valid in the new, subsetted object's metadata.

- Ensure all necessary pre-processing steps (

MNN Integration Troubleshooting

Problem: The M*N Integration Problem in Custom Workflows

- Description: The M*N problem arises when you have M different applications (e.g., AI agents for data analysis) that each need to interact with N different tools or data sources. Building a custom integration for every possible app-tool pair results in a combinatorial explosion of integrations (M × N) that is complex and unsustainable. [40] In research, this mirrors building custom scripts to apply every batch-correction method to every data type.

- Solution: Adopt a Model Context Protocol (MCP)-like strategy. [40]

- Standardized Protocol: Implement a standardized protocol (like MCP servers) for data sources and tools. [40]

- Client-Server Architecture: Each tool or data source needs only one MCP server. Any application (client) that understands the MCP protocol can then connect to it. [40]

- Reduced Complexity: This reduces the integration complexity from M × N down to just M + N, making the ecosystem of tools and apps vastly more manageable and scalable. [40]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main causes of failure in batch effect correction algorithms? A1: Failures typically stem from two primary sources:

- Technical Issues: Over-correction, where biological signal is mistakenly removed along with batch effects; under-correction, where batch effects persist; and excessive computational demands that make analysis infeasible with available resources. [38] [39]

- Strategic Issues: Using multiple, disconnected correction tools that do not communicate, leading to conflicting results and conclusions, a problem often termed "disconnected intelligence" or the "M*N integration problem." [37] [40]

Q2: How do I choose between Harmony, MNN, and Seurat's CCA/RPCA for my chemogenomic data? A2: The choice involves a trade-off between computational efficiency and the strength of integration.

- Seurat CCA: A robust, widely used method that can handle strong batch effects but is computationally demanding, especially for large datasets. [39]

- Seurat RPCA: A faster, less memory-intensive alternative to CCA within the Seurat toolkit, which is more conservative and may be preferable when batch effects are less severe. [39]

- Harmony: Generally faster and less memory-intensive than Seurat's CCA, making it suitable for large-scale datasets. It is often a good choice when computational resources are a limiting factor. [39]

- MNN: As a foundational algorithm, understanding its principle is key. For practical applications, using it via a framework that solves the M*N integration problem is advised for scalability. [40]

Q3: My integration is running out of memory. What are my options? A3:

- Downsample: Use the

SketchDatafunction in Seurat v5 to perform integration on a representative subset of cells. [38] - Switch Algorithms: Move from a memory-heavy method like CCA to a more efficient one like RPCA or Harmony. [39]

- Increase Hardware: If possible, run the analysis on a machine with more RAM.

Q4: What is the "MN integration problem" and how is it solved? A4: The MN problem describes the inefficiency of building a custom integration between every one of M applications and every one of N tools, resulting in M × N integrations. [40] The Model Context Protocol (MCP) solves this by introducing a standard protocol. Each tool needs one MCP server, and each app needs one MCP client, reducing the total integrations to M + N. [40] This strategy is analogous to how Google Translate uses an interlingua approach to avoid building a model for every possible language pair. [40]

The table below summarizes key quantitative data related to integration challenges and performance.

| Metric | Value / Description | Context / Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset Size Causing Long Runtime | ~630K cells, 110 libraries [38] | FindIntegrationAnchors can take >3 days [38] |

| Recommended Sketch Size | 5,000 cells per dataset [38] | Used in Seurat v5 to make large integrations feasible [38] |

| Unintegrated Applications | 71% of enterprise applications [41] | Highlights the pervasiveness of data silos [41] |

| Developer Time Spent on Integration | 39% [41] | Significant resource drain in IT and bioinformatics [41] |

| iPaaS Market Revenue (2024) | >$9 billion [41] | Indicates massive demand for integration solutions [41] |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Seurat v5 Integration Workflow with Sketching

This protocol is designed for integrating a very large number of single-cell RNA-seq libraries. [38]

- Load and Prepare Data: Read each library as a Seurat object and combine them into a list.

- Independent Pre-processing: For each object in the list:

FindVariableFeatures(..., nfeatures = 2500)SketchData(..., n = 5000)// Down-samples each datasetNormalizeData(...)

- Select Features and Scale: Use

SelectIntegrationFeatureson the list to identify features for integration. Then, for each sketched object:ScaleData(..., features = features)RunPCA(..., features = features)

- Find Integration Anchors:

FindIntegrationAnchors(object.list = filtered_seurat.list, anchor.features = features, reduction = "rpca") - Integrate Data:

IntegrateData(anchorset = anchors) - Downstream Analysis: Set the default assay to "integrated" and proceed with

ScaleData,RunPCA,RunUMAP, andFindNeighbors/FindClusterson the sketched integrated object. - Project to Full Dataset: Use

ProjectIntegrationandProjectDatato project the integrated model back to the full, non-sketched dataset. [38]

Protocol for Subsetting and Re-integrating Clusters

This protocol is for performing sub-clustering analysis on a pre-integrated object. [36]

- Subset the Object: From a larger, analyzed Seurat object, extract a population of interest.

Idents(merged_seurat) <- "RNA_snn_res.0.3"// Set active ident to desired clusteringCD4T <- subset(x = merged_seurat, idents = c('3'))// Subset the cluster

- Re-preprocess the Subset: The subsetted object must be re-normalized and re-scaled.

CD4T <- NormalizeData(CD4T)CD4T <- FindVariableFeatures(CD4T)CD4T <- ScaleData(CD4T)CD4T <- RunPCA(CD4T)

- Re-integrate: Perform a new round of integration to remove batch effects within the sub-cluster.

CD4T <- IntegrateLayers(CD4T, method = HarmonyIntegration, orig.reduction = "pca", new.reduction = "harmony", verbose = FALSE, group.by.vars = "Your_Batch_Variable_Here")// Critical: Specify the batch variable.

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

The M*N Integration Problem vs. The MCP Solution

Seurat v5 Sketching Integration Workflow

Disconnected AI vs. Unified Intelligence

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Harmony | Fast, versatile integration algorithm for removing batch effects. | Single-cell genomics; can be called via IntegrateLayers in Seurat. [36] [39] |

| Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) | Foundational batch-effect correction algorithm that identifies mutual nearest neighbors across batches to correct the data. | A core method implemented in various tools (e.g., Seurat, scran) for single-cell data integration. [40] |