Automating Discovery: Advanced Strategies for High-Throughput Chemical Genetic Screens

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern automation strategies revolutionizing chemical genetic screening.

Automating Discovery: Advanced Strategies for High-Throughput Chemical Genetic Screens

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern automation strategies revolutionizing chemical genetic screening. It explores the foundational principles of using small molecules for unbiased phenotypic discovery and details the integration of robotics, liquid handling systems, and sophisticated data analysis software. The content covers practical methodologies from cell-based assays in model organisms to complex 3D organoid systems, alongside key troubleshooting and optimization techniques for ensuring data quality and reproducibility. Furthermore, it examines advanced validation approaches, including the use of artificial intelligence and computational tools like DeepTarget, to confirm hits and compare screening methodologies. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to enhance the efficiency and predictive power of automated screening pipelines.

The Principles and Power of Phenotypic Screening in Chemical Genetics

Chemical genetics is an interdisciplinary approach that uses small molecules to perturb and study protein function within biological systems. Analogous to classical genetics, which uses gene mutations to understand function, chemical genetics uses small molecules to modulate protein activity with high temporal resolution and reversibility. This field employs two primary screening strategies: target-based screening, which starts with a predefined protein target, and phenotypic screening, which begins by observing a desired cellular or organismal phenotype [1] [2].

This technical support guide addresses common experimental challenges and provides actionable protocols to enhance the reliability and efficiency of your chemical genetics research, with particular emphasis on automation-friendly approaches.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Category 1: Screening Design and Implementation

Q: What are the key considerations when choosing between target-based and phenotypic screening approaches?

A: Your choice should be guided by your research goals and resources. Target-based screening is ideal when a specific, well-validated protein target is already implicated in a disease process. In contrast, phenotypic screening is superior for unbiased discovery of both new therapeutic compounds and novel druggable targets directly in complex cellular environments. Phenotypic screening directly measures drug potency in biologically relevant systems and can reveal unexpected mechanisms of action [1].

Q: How can I improve the success rate of phenotypic screens in model organisms like yeast?

A: S. cerevisiae is an excellent platform for high-throughput phenotypic screening due to its rapid doubling time, well-characterized genome, and conserved eukaryotic processes. However, researchers often encounter issues with compound efficacy. To address this:

- Use yeast strains with mutated efflux pumps (e.g., pdr5Δ) to increase intracellular compound accumulation [1].

- Consider the cell wall as a permeability barrier; some compounds may require higher concentrations or specialized formulations for effective cellular entry.

- Utilize automated robotics like the Singer ROTOR+ for pinning high-density arrays to ensure reproducibility and throughput [1].

Category 2: Library-Related Challenges

Q: How should I select and curate a chemical library for a forward chemical genetics screen?

A: Effective library design is crucial for screening success:

- Diversity Over Size: Focus on libraries that cover maximum chemical space with enriched bioactive substructures rather than simply maximizing compound count [1].

- Source Considerations: Utilize both natural products (which provide privileged scaffolds with biological relevance) and synthetic compounds (including diversity-oriented synthesis libraries) [3].

- Drug-like Properties: Pre-filter compounds for favorable properties like solubility and bioavailability to increase hit viability [3].

- Specialized Libraries: For focused research, consider chemogenomic libraries targeting specific protein families (e.g., kinases, GPCRs) or dark chemical matter (compounds historically inactive in screens but with potential unique activities) [3].

Q: What are common reasons for high false-positive rates in primary screens, and how can I mitigate them?

A: High false-positive rates often stem from compound toxicity, assay interference, or off-target effects. Implement these strategies:

- Counterscreening: Include orthogonal assays to exclude non-specific effects early.

- Titration Studies: Confirm dose-dependent responses for initial hits.

- Quality Control: Rigorously maintain compound storage conditions (-20°C in non-frost-free freezers) to prevent degradation [4].

- Automation Consistency: Use liquid handling robots to minimize volumetric errors and cross-contamination [5].

Category 3: Target Identification and Validation

Q: What are the most effective methods for identifying cellular targets after phenotypic screening?

A: After confirming phenotype-altering compounds, several gene-dosage based assays in yeast can identify direct targets and pathway components. The following table summarizes the three primary approaches [1]:

| Method | Principle | Key Outcome | Experimental Setup |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haploinsufficiency Profiling (HIP) | Reduced gene dosage increases drug sensitivity [1] | Identifies direct targets and pathway components [1] | Heterozygous deletion mutant pool grown with compound [1] |

| Homozygous Profiling (HOP) | Complete gene deletion mimics compound inhibition [1] | Identifies genes buffering the target pathway [1] | Homozygous deletion mutant pool grown with compound [1] |

| Multicopy Suppression Profiling (MSP) | Increased gene dosage confers drug resistance [1] | Identifies direct drug targets [1] | Overexpression plasmid library grown with compound [1] |

Q: My target identification experiments are yielding inconsistent results. What could be wrong?

A: Inconsistencies often arise from technical variability or compound-related issues:

- Ensure Robust Screening Conditions: Standardize culture conditions, compound concentrations, and readouts across replicates. Automated platforms significantly enhance reproducibility [5].

- Verify Compound Integrity: Re-check compound purity, stability, and storage conditions. Degraded compounds produce unreliable results.

- Control Genetic Background: Use well-curated, barcoded strain collections for HIP/HOP/MSP assays to ensure accurate strain tracking [1].

- Leverage Bioinformatics: Integrate chemical-genetic profiles with genetic interaction databases to strengthen target inferences [1].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Automated High-Throughput Phenotypic Screening in Yeast

This protocol utilizes automated pinning robots for efficient chemical screening [1].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Yeast Strains: Choose deletion collections (e.g., BY4741 background) or disease-model strains. For enhanced sensitivity, use strains deficient in efflux pumps (e.g., pdr5Δ) [1].

- Chemical Libraries: Pre-plated compounds in 384- or 1536-well formats, maintained at -20°C until use.

- Growth Media: Standard YPD or synthetic complete media, prepared fresh.

- Automation Equipment: Singer ROTOR+ or equivalent pinning robot.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Grow yeast strains overnight in liquid media to stationary phase.

- Normalization: Adjust cultures to standard OD600 (e.g., 0.5) in fresh media.

- Replication: Using an automated pinner, transfer cells to agar plates containing compounds or vehicle control.

- Incubation: Grow plates at 30°C for 36-48 hours.

- Imaging and Analysis: Automatically capture colony size images and quantify growth using specialized software (e.g, the CNN-based tools mentioned in [6]).

- Hit Validation: Re-test candidate compounds in dose-response format.

Protocol 2: Differential Chemical Genetic Screen in Plants

This protocol adapts phenotypic screening for plant systems, incorporating machine learning for phenotype quantification [6].

Methodology:

- Plant Material: Surface-sterilize Arabidopsis thaliana seeds of wild-type and mutant genotypes (e.g., mus81 DNA repair mutant).

- Chemical Treatment: Transfer seeds to multi-well plates containing liquid media with compounds from libraries (e.g., Prestwick library) or DMSO control.

- Growth Conditions: Stratify seeds at 4°C for 48 hours, then grow under controlled light/temperature for 7-10 days.

- Phenotype Documentation: Capture high-resolution seedling images daily.

- Image Analysis: Process images using convolutional neural network (CNN)-based segmentation programs to quantify growth parameters [6].

- Hit Identification: Apply statistical analysis to identify compounds causing genotype-specific growth phenotypes.

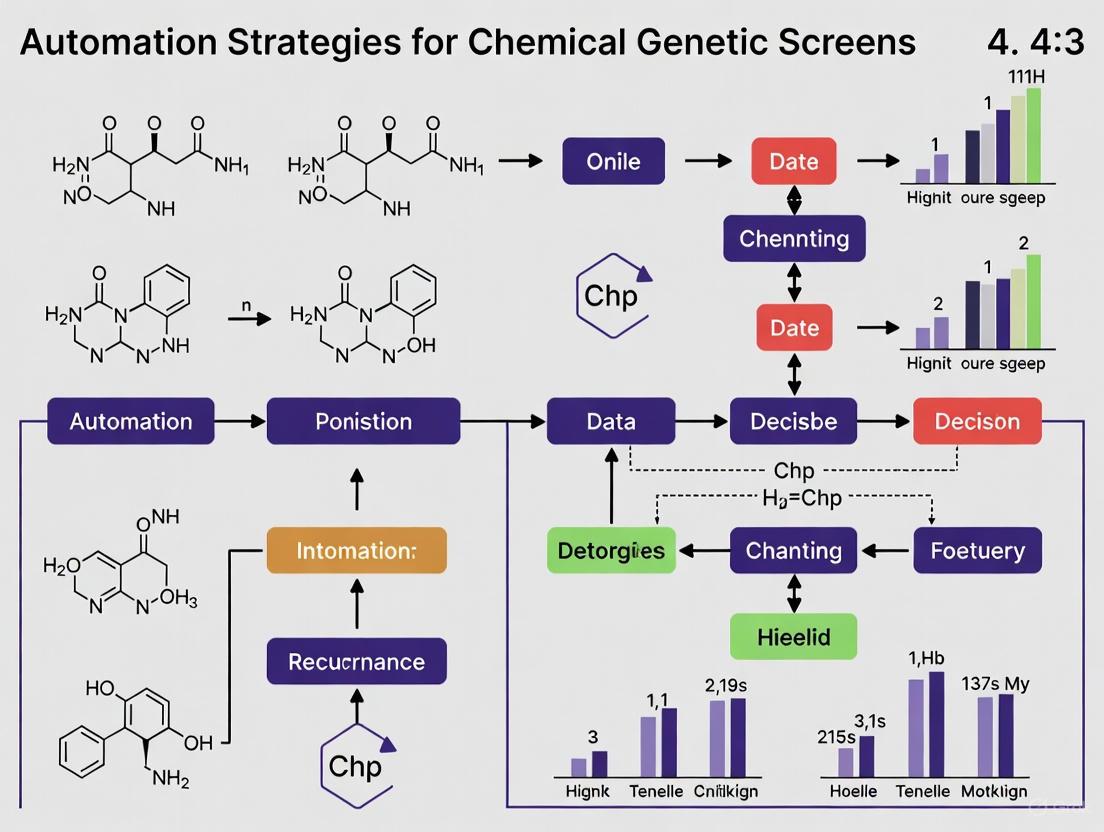

Workflow Visualization

Chemical Genetics Screening Strategies

AI-Automated Experiment Planning

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Deletion Collections | Comprehensive sets of heterozygous/homozygous deletion strains for genome-wide screening [1] | Barcoded for pooled fitness assays; ideal for HIP/HOP profiling [1] |

| Specialized Chemical Libraries | Collections of compounds enriched for bioactivity or targeting specific protein families [3] | Prestwick Library (off-patent drugs) or DOS libraries are valuable starting points [6] [3] |

| Automated Pinpoint Robot | High-density replication of microbial arrays for parallel compound testing [1] | Enables screening of 1000s of compounds/strains simultaneously (e.g., Singer ROTOR+) [1] |

| LLM Agent Systems | AI co-pilots for experimental design, troubleshooting, and data analysis [7] | Systems like CRISPR-GPT assist with CRISPR design; adaptable to chemical genetics workflows [7] |

| Barcoded Strain Pools | Molecularly tagged yeast strains for competitive growth assays [1] | Allows quantitative tracking of strain fitness in mixed cultures via barcode sequencing [1] |

| 3D Cell Culture Systems | Biologically relevant human tissue models for phenotypic screening [5] | Automated platforms (e.g., MO:BOT) standardize organoid culture for reproducible compound testing [5] |

Core Concepts & System Integration

Automated screening workflows are foundational to modern high-throughput research in fields like drug discovery and chemical genetics. They integrate three core technological components—robotics, automated liquid handling (ALH), and detection systems—to execute experiments with unparalleled speed, precision, and reproducibility. The central goal is to create a seamless, closed-loop system where these components work in concert to minimize human intervention, reduce errors, and generate high-quality, statistically significant data.

The Synergy of Core Components

The efficiency of an automated screening workflow stems from the tight integration of its parts. Robotics systems provide the high-level orchestration and physical movement of labware between stations. Liquid handlers perform the nanoscale to microliter-scale liquid manipulations that are fundamental to assay setup. Detection systems, in turn, measure the outcomes of these biological or chemical reactions. This synergy compresses traditional research timelines; for instance, AI-driven discovery platforms have compressed early-stage work from years to months, a feat reliant on automated workflows for validation [8].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common operational challenges, providing targeted questions and answers to help researchers maintain workflow integrity.

Liquid Handling Troubleshooting

| Problem Category | Specific Symptoms | Probable Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Transfer Inaccuracy | • Edge effects (errors in edge wells of a plate)• Loss of signal over time• High data variability [9] | • Wear and tear on pipette tips/tubing [9]• Loose fittings or obstructions [9]• Incorrect pipetting parameters for liquid viscosity [9] | • Perform gravimetric or photometric volume verification [9].• For high-viscosity liquids, use a lower flow rate to prevent air bubbles [9].• For sticky liquids, use a higher blowout air volume [9]. |

| System Contamination | • Reagent carryover between steps• Unexpected background signal or noise | • Residual reagent buildup on pipette tips [9] | • Regularly clean permanent tips [9].• Implement adequate cleaning protocols between sequential dispensing steps [9].• Ensure appropriate disposable tip selection for the liquid type [9]. |

| Liquid Handler Performance Verification | |||

| Verification Method | Procedure Overview | Key Metric | Advantage/Disadvantage |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Gravimetric Analysis | Dispense liquid into a vessel on a precision balance and measure the mass. | Dispensed volume (calculated from mass and density). | High precision; requires dedicated equipment [9]. |

| Photometric Analysis | Use a dye solution; dispense into a plate and measure absorbance/fluorescence. | Dispensed volume (calculated from dye concentration and signal). | Can be performed directly in standard labware [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions: Liquid Handling

Q: My liquid handler is dispensing inaccurately only in specific columns of the microtiter plate. What should I check?

- A: This pattern strongly suggests a mechanical issue with specific pipetting channels. Inspect for visible wear, kinks, or bends in the tubing corresponding to those columns. Check for loose fittings and ensure the pipette head is properly aligned and leveled. A performance verification test (gravimetric/photometric) can confirm which specific channels are affected [9].

Q: How can I prevent liquid carryover when my protocol has multiple dispensing steps?

- A: For systems with disposable tips, ensure you are using a fresh tip for each transfer. For systems with permanent tips, you must incorporate a robust washing and cleaning protocol between different reagent additions. Adjusting the blowout volume can also help ensure no residual liquid remains in the tip [9].

Robotics & Integration Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions: Robotics

Q: Our automated workflow is experiencing bottlenecks, reducing overall throughput. How can we identify the cause?

- A: Bottlenecks typically occur at the slowest step in the process. Map your entire workflow and time each discrete step (e.g., plate movement, liquid dispensing, incubation, reading). Common culprits are long incubation times that tie up the robot or a slow detection step. The solution often involves optimizing the scheduling software (e.g., Tecan's FlowPilot) to manage complex, multi-step workflows in parallel, ensuring resources are used efficiently [5].

Q: How critical is the integration between the robotic arm, liquid handler, and detector?

- A: It is paramount. The true value of automation is lost if systems operate in isolation. Seamless integration, managed by scheduling software, is what creates a walk-away operation. This requires standardized labware (e.g., specific plate types and footprints), clear communication protocols between devices (e.g., via PLC or TTL triggers), and software that can handle error recovery without human intervention [5].

Detection & Data Quality Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions: Detection

Q: We are seeing high variability in our replicate data from an automated screen. What are the primary sources of this noise?

- A: High variability can originate from several sources in an automated workflow. First, rule out liquid handling inaccuracy using photometric or gravimetric tests [9]. Second, ensure environmental factors like temperature and humidity are stable, as they can affect both reagent stability and detector performance. Finally, inconsistencies in cell seeding or viability (for cell-based assays) are a common source of biological noise. Automating cell culture with systems like the mo:re MO:BOT can significantly improve reproducibility in 3D cell culture assays [5].

Q: For AI-driven discovery, what is the most critical aspect of data generated by the detection system?

- A: Beyond the results themselves, comprehensive metadata and traceability are critical. As noted by Tecan's Mike Bimson, "If AI is to mean anything, we need to capture more than results. Every condition and state must be recorded, so models have quality data to learn from." [5] This means your detection systems and data management platforms must capture every experimental condition, instrument state, and reagent lot number to provide context for the primary data.

Performance Metrics & Benchmarking

To ensure your automated screening workflow is performing optimally, it is essential to benchmark its components against industry standards and quantitative metrics.

Automated Liquid Handling Performance Metrics

Regular verification against these key metrics is recommended for quality control.

| Performance Parameter | Target Value (Industry Standard) | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (Trueness) | ≤ 5% deviation from target volume [10] | Gravimetric or photometric analysis [9]. |

| Precision (Repeatability) | ≤ 3% CV (Coefficient of Variation) for volumes ≥ 1 µL [10] | Gravimetric or photometric analysis [9]. |

| Detection System Accuracy | Up to 97% with AI-powered algorithms [10] | Comparison against known standards and manual inspection. |

Experimental Protocols for Workflow Validation

Protocol: Gravimetric Performance Verification of a Liquid Handler

1. Principle: This method calculates the volume of liquid dispensed by accurately measuring its mass and using the known density of the liquid (typically water) for conversion.

2. Materials:

- Automated Liquid Handler

- High-precision analytical balance (capable of µg resolution)

- Suitable clean, dry weighing vessel (e.g., microtiter plate, empty PCR tube strip)

- Purified water

- Data collection sheet or software

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Place the weighing vessel on the balance and tare the balance to zero.

- Step 2: Program the liquid handler to dispense the target volume (e.g., 10 µL) into the vessel.

- Step 3: Execute the dispense command. Record the mass displayed on the balance.

- Step 4: Repeat Steps 1-3 for a minimum of 10 replicates per channel being tested.

- Step 5: Calculate the actual volume dispensed using the formula: Volume (µL) = Mass (mg) / Density (mg/µL). For water at 20°C, density is ~1.0 mg/µL.

- Step 6: Calculate the mean volume, accuracy (% deviation from target), and precision (% Coefficient of Variation) for the data set.

Protocol: Miniaturized Assay Setup for High-Throughput Screening

1. Principle: This protocol outlines a generalized procedure for using an automated workstation to prepare a compound screening assay in a 384-well microplate format.

2. Materials:

- Integrated robotic system with liquid handler

- 384-well microplates (assay ready)

- Source plates containing test compounds, controls, and reagents

- Appropriate pipette tips

- Assay-specific detection reagents

3. Workflow:

4. Procedure:

- Step 1: Dispense Buffer. The liquid handler aliquots a defined volume of assay buffer or cell culture media into all wells of the 384-well plate.

- Step 2: Compound Transfer. Using the liquid handler, transfer nanoliter volumes of test compounds from a source library plate to the assay plate. Include positive and negative controls on each plate.

- Step 3: Add Biological Component. The liquid handler adds a suspension of cells or the target enzyme to initiate the biochemical reaction.

- Step 4: Incubation. The robotic arm moves the assay plate to a controlled-environment hotel (e.g., CO₂ incubator, thermal cycler) for a specified incubation period.

- Step 5: Add Detection Reagents. After incubation, the robotic arm retrieves the plate and the liquid handler adds detection reagents (e.g., luciferin, fluorescent dye).

- Step 6: Signal Development. The plate is incubated a final time to allow the signal to develop.

- Step 7: Detection. The robotic arm transports the plate to a multimode detector (e.g., luminometer, fluorimeter) for endpoint reading.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are critical for the successful execution of automated chemical genetic screens.

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Workflow | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Assay-Ready Microplates | The standardized vessel for reactions (e.g., 96-, 384-, 1536-well). | Well geometry, surface treatment (e.g., tissue culture treated), and material compatibility with detectors (e.g., low fluorescence background). |

| Compound Libraries | Collections of small molecules or genetic agents (e.g., siRNAs) used for screening. | Solvent compatibility (e.g., DMSO tolerance), concentration, and storage stability. |

| Viability/Cell Titer Reagents | To measure cell health and proliferation (e.g., ATP-based luminescence assays). | Must be compatible with automation (viscosity, stability) and provide a robust signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Agilent SureSelect Kits | For automated target enrichment in next-generation sequencing workflows, as used in collaboration with SPT Labtech's firefly+ platform [5]. | Proven chemistry that is validated for integration with automated liquid handling protocols to ensure reproducibility [5]. |

| Validated Antibodies & Dyes | For specific detection of targets in immunoassays or cell staining. | Lot-to-lot consistency, compatibility with automated dispensers, and photostability. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why are model organisms like S. cerevisiae and A. thaliana particularly useful for chemical genetic screens?

They offer unique advantages that circumvent common limitations of traditional genetic approaches. S. cerevisiae, as a simple eukaryote, shares fundamental cellular processes like cell division with humans, making it a relevant model for studying human diseases such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [11]. A. thaliana is small, has flexible culture conditions, and a wealth of available mutant and reporter lines, making it ideal for dissection of signaling pathways at the seedling stage [12]. In chemical genetics, small molecules can overcome problems of genetic redundancy, lethality, or pleiotropy (where one gene influences multiple traits) by conditionally modifying protein function, which is difficult to achieve with conventional mutations [12].

FAQ 2: My high-throughput screening (HTS) data is noisy and inconsistent. What are the main sources of error and how can I mitigate them?

Manual liquid handling is a primary source of error in HTS, leading to inaccuracies in compound concentration and volume, which results in unreliable data [13]. Implementing automated liquid handling systems significantly improves accuracy and consistency by ensuring correct reagent preparation, mixing, and transfer [13]. Furthermore, robust assay development is crucial. Your bioassay must be reliable, reproducible, and suitable for a microplate format. Whenever possible, use quantitative readouts like fluorescence or luminescence, which provide strong signals and allow for automated, unbiased hit selection [12].

FAQ 3: I've identified "hit" compounds from my primary screen. What is the critical next step before further investigation?

Hit validation is essential. A single primary screen is not sufficient to establish a compound's biological relevance. You must perform rigorous validation to confirm the activity and, most importantly, the selectivity of the candidate compounds. This process often involves secondary assays that are orthogonal to your primary screen's detection method [12].

FAQ 4: What are the key considerations when designing a chemical screening campaign?

Successful campaigns require careful planning of three core elements [12]:

- A robust bioassay: The assay must be reliable, quantitative, and adaptable to a microplate format for HTS.

- Hit validation process: A strategy to confirm the selectivity and potency of initial hits.

- Target identification: A plan for elucidating the molecular target and mode of action of bioactive compounds, which can be the most challenging part.

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol: A Generalized Workflow for a High-Throughput Chemical Genetic Screen in A. thaliana Seedlings

This protocol is adapted from established plant chemical biology methodologies [12].

1. Assay Development and Optimization:

- Objective: Establish a robust, quantitative phenotype in a microplate format.

- Steps:

- Plant Material: Surface-sterilize A. thaliana seeds of a relevant ecotype or reporter line.

- Sowing: Dispense seeds into sterile, multi-well plates (e.g., 48- or 96-well) containing a standardized volume of liquid or solid growth medium. Using multiple plants per well can increase data robustness.

- Treatment: Use an automated liquid handler to add chemical libraries from compound source plates to the assay plates. Include positive (known bioactive compound) and negative (solvent only) controls on every plate.

- Growth Conditions: Incubate plates under controlled light and temperature for a defined period (e.g., 5-7 days).

- Readout: Quantify the phenotype using a microplate reader. For a reporter line, this could be fluorescence or luminescence. For morphological changes, high-content imaging systems can be used.

2. Primary Screening:

- Objective: To test all compounds in the library for activity in your bioassay.

- Steps:

- Automation: Use robotic systems for all liquid and plate handling to ensure speed and consistency [13].

- Data Acquisition: Automatically collect raw data (e.g., fluorescence intensity, luminescence counts) from the microplate reader.

- Hit Selection: Use statistical methods (e.g., Z'-factor for assay quality, standard deviations from the negative control mean) to automatically identify initial "hit" compounds.

3. Hit Validation and Secondary Assays:

- Objective: To confirm the activity and specificity of primary hits.

- Steps:

- Dose-Response: Re-test hit compounds across a range of concentrations (e.g., 1 nM to 100 µM) to determine potency (IC50/EC50).

- Selectivity Testing: Test compounds in secondary assays designed to rule out non-specific effects. For example, a compound affecting root growth could be tested in a general viability assay.

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR): Test structurally related analogs to identify the core chemical scaffold essential for bioactivity [12].

Quantitative Data from High-Throughput Screening

The following table summarizes key performance metrics and the impact of automation on HTS operations.

| Metric | Manual Workflow | Automated Workflow | Impact of Automation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low (limited by human speed) | High (can run 24/7) | Allows screening of larger compound libraries [13]. |

| Liquid Handling Accuracy | Prone to human error | High precision (e.g., non-contact dispensing as low as 4 nL) [13] | Reduces false positives/negatives; improves data reliability [13]. |

| Data Processing Time | Slow, labor-intensive | Rapid, automated analysis | Enables near real-time insights into promising compounds [13]. |

| Operational Cost | High (labor, repeat experiments) | Reduced (less reagent use, fewer repeats) | Saves on reagents and labor costs over time [13]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

HTS Workflow with Automation

Chemical Genetics Advantages

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for conducting high-throughput chemical genetic screens.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in High-Throughput Assays |

|---|---|

| Chemical Library | A collection of diverse small molecules used to perturb biological systems and identify novel bioactive compounds [12]. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Robotic system that ensures accurate, precise, and high-speed dispensing of reagents and compounds into microplates, essential for reproducibility [13]. |

| Quantitative Reporter Line | A genetically engineered organism (e.g., A. thaliana or S. cerevisiae) that produces a measurable signal (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence) in response to a biological event of interest [12]. |

| Microplate Reader | Instrument for automated detection of assay readouts (absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence) directly from multi-well plates, enabling quantitative data acquisition [12]. |

| S. cerevisiae Model System | A simple eukaryotic model used to study conserved pathways, cell division, and human diseases like Parkinson's, ideal for genetic and chemical manipulation [11]. |

| A. thaliana Model System | A plant model organism suited for microplate culture, offering flexible conditions and numerous genetic resources for dissecting signaling pathways [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the key criteria for selecting compounds for a focused small-molecule library? The selection should be based on a multi-parameter approach that includes binding selectivity, target coverage, structural diversity, and stage of clinical development [14]. The primary goal is to minimize off-target overlap while ensuring comprehensive coverage of your target class of interest. Key data to curate includes chemical structure, target dose-response data (Ki or IC50 values), profiling data from large protein panels, nominal target information, and phenotypic data from cell-based assays [14].

FAQ 2: How can I minimize the confounding effects of compound polypharmacology in my screen? Polypharmacology can be mitigated by using multiple compounds with minimal off-target overlap for each target of interest [14]. Utilize available tools and algorithms that optimize library composition based on binding selectivity data. These tools help assemble compound sets where each additional compound contributes unique target coverage rather than redundant activity, ensuring that any observed phenotype can be more confidently attributed to the intended target [14].

FAQ 3: What are the advantages of using smaller, focused libraries versus larger screening collections? While large libraries enable exploration of more chemical space, they typically require high-throughput assays that are biologically simplified [14]. Smaller, focused libraries (typically 30-3,000 compounds) enable complex phenotypic assays, thorough dose-response studies, screening of drug combinations, and identification of conditions that promote sensitivity and resistance [14]. Focused libraries are widely used for studying specific biological processes and uncovering drug repurposing opportunities [14].

FAQ 4: How does automation enhance small-molecule library management and screening? Automation brings reproducibility, integration, and usability to library management [5]. It replaces human variation with stable systems that generate more reliable data, enables complex multi-instrument workflows, and frees researchers from repetitive tasks like pipetting to focus on analysis and experimental design [5]. Automated systems also enhance metadata capture and traceability, which is essential for building effective AI/ML models [5].

FAQ 5: What common data quality issues affect small-molecule library screening results? Many organizations struggle with fragmented, siloed data and inconsistent metadata, which creates significant barriers to automation and AI implementation [5]. Successful screening requires well-annotated compounds with standardized identifiers and complete activity data. Solutions include implementing informatics platforms that connect data, instruments, and processes, and using structural similarity matching (e.g., Tanimoto similarity of Morgan2 fingerprints) to correctly combine data for the same compound under different names [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Reproducibility in Screening Results

Symptoms: High well-to-well variation, inconsistent dose-response curves, poor Z-factor scores.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid handling inconsistency | Check pipette calibration; run dye-based uniformity tests | Implement automated liquid handlers (e.g., Tecan Veya) with regular maintenance schedules [5] |

| Compound degradation or precipitation | Review storage conditions (-20°C or -80°C); check for crystal formation | Use standardized DMSO quality; implement freeze-thaw cycling limits; use labware management software (e.g., Titian Mosaic) [5] |

| Inadequate metadata tracking | Audit data capture for cell passage number, serum lot, operator ID | Implement digital R&D platform (e.g., Labguru) to enforce complete metadata entry [5] |

Prevention Protocol:

- Establish standardized operating procedures for compound handling, storage, and replication.

- Implement automated systems for consistent plate preparation and reduce human error [5].

- Use color-coded labeling systems (e.g., silicone bands) to prevent cross-contamination [5].

Issue 2: Ambiguous Hit Validation Due to Polypharmacology

Symptoms: Phenotype not reproducible with structurally distinct compounds targeting same nominal target; unexpected toxicity or off-target effects.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate selectivity profiling | Check published selectivity data (ChEMBL, DiscoverX KINOMEscan); analyze structural similarity to promiscuous binders [14] | Utilize tools like SmallMoleculeSuite.org to assess off-target overlap; select compounds with complementary selectivity profiles [14] |

| Insufficient compound diversity | Calculate Tanimoto similarity coefficients; identify structural clusters with similarity ≥0.7 [14] | Curate library to include structurally diverse chemotypes for each target; utilize existing diverse collections (e.g., LINCS, Dundee) [14] |

| Incomplete target coverage | Map compound-target interactions; identify gaps in target space coverage | Use library design algorithms to optimize target coverage with minimal compounds; consider LSP-OptimalKinase as a model [14] |

Validation Workflow:

- Confirm activity of primary hit in dose-response.

- Test structurally distinct compounds with same nominal target.

- Check selectivity profiles across relevant target families.

- Use CRISPR-based genetic validation where appropriate.

- Employ open, transparent AI workflows to generate interpretable biological insights [5].

Issue 3: Inefficient Library Design for Specific Biological Applications

Symptoms: Library too large for complex phenotypic assays; inadequate coverage of target class; insufficient clinical relevance.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly generic library composition | Analyze library against specific target class (e.g., kinome coverage); assess inclusion of clinical-stage compounds | Create application-specific libraries using data-driven design tools that incorporate clinical development stage [14] |

| Poor balance between size and diversity | Calculate library diversity metrics; compare to established libraries (PKIS, LINCS) [14] | Implement algorithms that minimize compound count while preserving diversity and target coverage [14] |

| Inadequate human relevance | Review model system limitations; assess translatability of previous screening results | Incorporate human-relevant models (e.g., 3D cell cultures, organoids) using automated platforms (e.g., MO:BOT) for better predictive value [5] |

Library Optimization Protocol:

- Define target coverage goals based on liganded genome concept.

- Select compounds based on multiple criteria: selectivity, structural diversity, clinical stage.

- Use optimization algorithms to minimize off-target overlap.

- Incorporate automation-compatible formats (e.g., 384-well plates).

- Establish regular update schedule to incorporate new compounds and data.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Analysis and Comparison of Existing Small-Molecule Libraries

Purpose: To quantitatively evaluate and compare the properties of different small-molecule screening libraries to inform selection or design of an optimal collection for specific research needs.

Materials:

- Library compound lists (e.g., SelleckChem Kinase Library, Published Kinase Inhibitor Set, Dundee collection, EMD Kinase Inhibitors, HMS-LINCS collection) [14]

- Cheminformatics software (e.g., SmallMoleculeSuite.org) [14]

- Chemical structure files (SDF, SMILES)

- Bioactivity database access (ChEMBL, PubChem)

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Compile compound lists from library vendors or public sources. Map all compounds to standardized identifiers (ChEMBL IDs preferred) [14].

- Structural Analysis: Calculate chemical similarity using Tanimoto similarity of Morgan2 fingerprints. Identify structural clusters with similarity ≥0.7 [14].

- Target Coverage Assessment: Annotate compounds with target data from biochemical assays (Ki, IC50). Map coverage across target class of interest [14].

- Selectivity Profiling: Integrate profiling data from panel-based assays (e.g., KINOMEscan). Calculate selectivity scores for each compound [14].

- Diversity Scoring: Quantify structural diversity by frequency and size of structural clusters. Compare diversity metrics across libraries [14].

- Clinical Relevance Assessment: Annotate compounds with stage of clinical development (approved, investigational, pre-clinical).

Data Analysis: The following table summarizes quantitative comparisons of six kinase-focused libraries performed using this methodology [14]:

| Library Name | Abbrev. | Compound Count | Structural Diversity | Unique Compounds | Clinical Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SelleckChem Kinase | SK | 429 | Medium | ~50% shared with LINCS | Varies |

| Published Kinase Inhibitor Set | PKIS | 362 | Low (designed with analogs) | 350 unique | Few |

| Dundee Collection | Dundee | 209 | High | Mostly unique | Varies |

| EMD Kinase Inhibitors | EMD | 266 | Medium | Mostly unique | Varies |

| HMS-LINCS Collection | LINCS | 495 | High | ~50% shared with SK | Includes approved drugs |

| SelleckChem Pfizer | SP | 94 | Medium | Mostly unique | Varies |

Protocol 2: Design of a Focused Screening Library

Purpose: To create an optimized, focused small-molecule library with maximal target coverage and minimal off-target effects for chemical genetics or drug repurposing screens.

Materials:

- Bioactivity database (ChEMBL recommended) [14]

- Library design tool (SmallMoleculeSuite.org or equivalent) [14]

- Structural similarity calculation software

- Target classification system

Procedure:

- Define Scope: Determine target class or biological process of interest. Define desired library size based on screening capabilities.

- Compound Selection: Identify potential inclusions from existing libraries, clinical development pipelines, and chemical probes.

- Data Integration: Curate binding selectivity data, target profiling data, structural information, and clinical stage for all candidate compounds.

- Algorithmic Optimization: Use library design algorithms to select compounds that minimize off-target overlap while maximizing target coverage. The algorithm should prioritize compounds with complementary selectivity profiles [14].

- Diversity Assessment: Ensure structural diversity by limiting analog clusters. Include structurally distinct compounds for key targets to control for polypharmacology [14].

- Clinical Relevance Integration: Incorporate approved drugs and clinical-stage compounds where possible to enhance translational potential.

- Validation: Test library performance in silico against target class. Compare to existing libraries for coverage and efficiency.

Example Implementation: The LSP-OptimalKinase library was designed using this approach and demonstrated superior target coverage and compact size compared to existing kinase inhibitor collections [14]. Similarly, an LSP-Mechanism of Action library was created to optimally cover 1,852 targets in the liganded genome [14].

Workflow Diagrams

Library Design Workflow

Screening Troubleshooting Guide

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Small-Molecule Library Screening

| Tool / Resource | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity data resource | Curates data from literature, patents, FDA approvals; provides standardized compound identifiers and activity metrics [14] |

| SmallMoleculeSuite.org | Library analysis & design tool | Online tool for scoring and creating libraries based on binding selectivity, target coverage, and structural diversity [14] |

| Automated Liquid Handlers (e.g., Tecan Veya) | Laboratory automation | Provides consistent, reproducible liquid handling; reduces human variation; enables complex multi-step workflows [5] |

| Sample Management Software (e.g., Titian Mosaic) | Compound inventory management | Tracks sample location, usage, and lineage; integrates with screening platforms; prevents compound degradation issues [5] |

| Digital R&D Platform (e.g., Labguru) | Electronic lab notebook & data management | Captures experimental metadata; enables data sharing and collaboration; supports AI-assisted analysis [5] |

| 3D Cell Culture Systems (e.g., MO:BOT) | Biologically relevant screening | Automates 3D cell culture; improves human relevance; reduces need for animal models; enhances predictive value [5] |

| KINOMEscan Profiling | Selectivity screening | Provides comprehensive kinase profiling data; identifies off-target interactions; informs compound selection [14] |

| Structural Similarity Tools | Cheminformatics analysis | Calculates Tanimoto similarity coefficients; identifies structural clusters and diversity; uses Morgan2 fingerprints [14] |

Implementing Automated Workflows: From 2D Assays to 3D Organoids

Automated Liquid Handling and Robotic Integration for Microplate Processing

Core Concepts and Performance Metrics

Automated liquid handling and robotic microplate processing are foundational to modern high-throughput laboratories, enabling the rapid and reproducible screening essential for chemical genetic screens and drug discovery [15] [16]. These systems address critical challenges such as increasing sample volumes, regulatory demands, and skilled labor shortages by enhancing efficiency, data integrity, and operational consistency [15].

Table 1: Typical Performance Metrics for Automated Microplate Systems

| Performance Parameter | Typical Value or Range | Impact on Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Handling Precision (CV) | <5% for most biological assays [16] | Ensures reproducible compound dispensing and reduces data variability. |

| Plate Handling Positioning Accuracy | ±1.2 mm and ±0.4° [17] | Enables reliable loading/unloading of instruments without jamming. |

| Throughput (24-well plates) | True leaf count: ~3.6 leaves/plant [18] | Higher well formats (e.g., 384-well) further increase throughput. |

| Economic Impact of Volume Error | 20% over-dispense can cost ~$750,000/year [16] | Underscores the financial necessity of regular calibration. |

The true transformation in laboratory efficiency occurs when automation moves beyond individual tasks to become a holistic, end-to-end concept [15]. This involves seamless workflows from sample registration and robot-assisted preparation to analysis and AI-supported evaluation, creating a highly reproducible process chain that minimizes human error [15] [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Liquid Handling Errors and Solutions

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Liquid Handling Issues

| Problem Category | Specific Symptoms | Potential Causes | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume Inaccuracy | Systematic over- or under-dispensing, high CV in assay results. | Incorrect liquid class; poorly calibrated instrument; unsuitable tip type [16]. | Use vendor-approved tips [16]; validate liquid classes for specific reagents (e.g., reverse mode for viscous liquids [16]); implement regular calibration [16]. |

| Cross-Contamination | Carryover between samples, unexpected results in adjacent wells. | Ineffective tip washing (fixed tips); droplet formation and splatter [16]. | For fixed tips: validate rigorous washing protocols [16]. For disposable tips: add a trailing air gap; optimize tip ejection locations [16]. |

| Serial Dilution Errors | Non-linear or erratic dose-response curves. | Inefficient mixing after dilution step; "first/last dispense" volume inaccuracies in sequential transfers [16]. | Ensure homogeneous mixing via on-board shaking or pipette mixing before transfer [16]; validate volume uniformity across a sequential dispense [16]. |

| Clogging & Fluidics Failure | Partial or complete failure to dispense; low-pressure errors. | Precipitates in reagent; air bubbles in lines or tips. | Centrifuge reagents to remove particulates; use liquid sensing tips cautiously with frothy liquids [16]. |

| Robotic Positioning Failure | Inability to pick up plates or insert them into instruments. | Instrument location drift; low positioning accuracy; environmental changes [17]. | Implement a localization method combining SLAM, computer vision, and tactile feedback for fine positioning [17]. |

System Integration and Operational Challenges

- Integration Complexity: Laboratories often use a mix of devices from different manufacturers with incompatible interfaces. Solution: Thoughtful planning of system architecture and process analysis is required before integration. A modular, scalable approach allows for gradual expansion without rebuilding the entire infrastructure [15].

- Data Management: Automation generates vast amounts of data. Solution: A solid plan for storing, analyzing, and utilizing this data is crucial for leveraging big data analytics and ensuring quality assurance [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary economic benefits of automating microplate processing? Automation significantly reduces human labor and error, leading to substantial time and cost savings [19]. More critically, it prevents massive financial losses caused by inaccurate liquid handling—even a slight 20% over-dispensation of critical reagents can lead to hundreds of thousands of dollars in wasted materials annually, not to mention the potential for false positives/negatives that could cause a promising drug candidate to be overlooked [16].

Q2: How do I choose between forward and reverse mode pipetting? Forward mode is standard for aqueous reagents (with or without small amounts of proteins/surfactants), where the entire aspirated volume is discharged. Reverse mode is suitable for viscous, foaming, or valuable liquids, where more liquid is aspirated than is dispensed (e.g., aspirate 8 µL to dispense 5 µL), with the excess being returned to the source or waste [16].

Q3: Our robotic system struggles with precise microplate placement. How can this be improved? Reliable plate handling requires millimeter precision. A proven method integrates multiple localization techniques: use Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) for initial navigation, computer vision (fiducial markers) for rough instrument pose estimation, and finally, tactile feedback (physically touching reference points on the instrument) to achieve fine-positioning accuracies of ±1.2 mm and ±0.4° [17].

Q4: What is the most overlooked source of liquid handling error? The choice of pipette tips is frequently underestimated. Cheap, non-vendor-approved tips can have variable material properties, shape, and fit, leading to inconsistent wetting and delivery. Always use manufacturer-approved tips to ensure accuracy and precision, and do not assume the liquid handler itself is at fault without first investigating the tips [16].

Q5: How can we ensure our automated workflows are sustainable and future-proof? Opt for modular and scalable automation systems with open interfaces that allow for gradual integration and adaptation to new technologies [15]. Furthermore, investing in systems that support AI-driven data analysis and IoT connectivity will prepare your lab for trends like real-time process optimization and predictive maintenance [15].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: High-Throughput Differential Chemical Genetic Screen

This protocol is adapted from a phenotype-based screen designed to identify small molecules that induce genotype-specific growth effects, using Arabidopsis thaliana as a model system [18].

1. Reagent and Material Setup:

- Plant Materials: Wild-type (WT) and mutant (e.g.,

mus81DNA repair mutant) seeds. - Chemical Library: For example, the Prestwick library of off-patent drugs.

- Controls: Negative control (DMSO), positive control (e.g., Mitomycin C for DNA repair mutants).

- Labware: Sterile 24-well microtiter plates.

- Growth Medium: Liquid culture medium optimized for robust seedling development.

2. Workflow Execution:

- Plate Planting: Dispense liquid medium into 24-well plates. Sow three seeds per well to ensure biological replicates.

- Compound Dispensing: Using an automated liquid handler, add small molecules from the library to respective wells. Include positive and negative control wells on every plate.

- Plant Growth: Incubate plates under controlled light and temperature conditions for 10 days.

- Image Acquisition: Capture high-resolution images of each well using a light macroscope.

3. Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Image Analysis: Process images using two complementary Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs):

- Hit Identification: Compare the growth patterns of WT and mutant seedlings for each compound. "Hits" are compounds that selectively affect the growth of one genotype but not the other.

Workflow: Integrated Robotic Microplate Processing

The following diagram illustrates a seamless, automated workflow for transporting and processing microplates between different stations, crucial for multi-stage experiments like Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) determination [17].

Diagram 1: Integrated Robotic Microplate Handling Workflow. This automated process uses a mobile manipulator with SLAM, vision, and tactile feedback for precise plate movement between benchtop instruments [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Automated Chemical Genetic Screens

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Vendor-Approved Disposable Tips | Ensures accuracy and precision; poor-quality tips are a major source of error due to variability in material, shape, and fit [16]. | All liquid handling steps, especially critical for serial dilutions and reagent transfers. |

| Liquid Sensing Conductive Tips | Detects the liquid surface during aspiration to maintain consistent tip depth (~2-3 mm below meniscus), preventing air gaps or splashing. | Aspirating reagents from reservoirs, particularly when liquid levels vary. Use with caution in frothy liquids [16]. |

| Microplates (e.g., 24-well) | Standardized labware (ANSI/SLAS format) compatible with robotic grippers and instruments. The 24-well format offers a good balance between throughput and plant growth space [18]. | Housing samples and reagents throughout the experimental workflow. |

| Fiducial Markers | Visual markers placed on instruments that are detected by a robot's camera to estimate the instrument's rough location and orientation [17]. | Enabling robotic vision-based localization for initial positioning. |

| Chemical Library (e.g., Prestwick) | A curated collection of small molecules, such as off-patent drugs, used to perturb biological systems and identify genotype-specific effects [18]. | The source of chemical compounds for the screening assay. |

| Positive Control Compound | A compound known to induce a specific phenotype (e.g., Mitomycin C for DNA repair mutants), used to validate assay performance [18]. | Included on every screening plate as a quality control measure. |

| Negative Control (DMSO) | The vehicle in which compounds are dissolved; used to establish a baseline for "normal" growth [18]. | Included on every screening plate for comparison with treated samples. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Experimental Design

Q1: What are the primary advantages of phenotypic screening over target-based approaches in drug discovery? Phenotypic screening allows for the identification of compounds based on their effects on whole cells or systems, without preconceived notions about a specific molecular target. This less-biased approach can reveal novel mechanisms of action (MoA) and is responsible for a significant proportion of first-in-class new molecular entities. It is particularly valuable when disease pathways are not fully understood, as the cellular response itself reveals therapeutically relevant targets [20].

Q2: How do reporter gene assays function in high-throughput screening (HTS)? Reporter genes are genes whose products can be easily detected and measured, serving as surrogates for monitoring biological activity. In HTS, they are invaluable for studying gene regulation. A common application involves creating a construct where a reporter gene (e.g., luciferase) is placed under the control of a regulatory element of interest. When a compound perturbs the pathway, it affects the activity of this regulatory element, leading to a change in reporter gene expression that can be quantified luminescently or fluorescently [21].

Q3: What is the role of morphological profiling in MoA deconvolution? Assays like Cell Painting use multiple fluorescent dyes to stain various cellular compartments, generating rich, high-dimensional morphological profiles. The core principle is "guilt-by-association": perturbations that induce similar morphological changes are likely to share a MoA. By clustering compounds based on their morphological profiles, researchers can infer the MoA of uncharacterized compounds and identify those with novel mechanisms [22] [23].

Q4: What are the key automation challenges in HTS, and how can they be addressed? Key challenges include human error, inter-user variability, and managing vast amounts of multiparametric data. These lead to reproducibility issues and unreliable results. Automation addresses this by:

- Standardizing liquid handling with non-contact dispensers to reduce variation [24].

- Integrating workflow components (robotic arms, incubators, imagers) for seamless, unattended operation [5].

- Implementing automated data pipelines to manage and analyze complex datasets, enabling faster insights [24].

Q5: How can AI and machine learning improve the analysis of high-content screening data? AI, particularly self-supervised learning (SSL), can transform image analysis. SSL models can be trained directly on large-scale microscopy image sets (like the JUMP Cell Painting dataset) without manual annotations to learn powerful morphological representations. These models can match or exceed the performance of traditional feature extraction tools like CellProfiler in tasks like target identification, while being computationally faster and eliminating the need for manual cell segmentation [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Z'-Factor in Viability Assays

Problem: The Z'-factor, a measure of assay quality and robustness, is unacceptably low, indicating poor separation between positive and negative controls.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in positive control | Check replicate consistency of controls. Review liquid handler performance. | Implement automated liquid handling with drop detection to ensure dispensing precision [24]. |

| Edge effects in microplates | Review plate maps for systematic evaporation patterns. | Use automation to randomize sample placement and include edge wells as blanks. Utilize environmental controls in automated incubators [5]. |

| Inconsistent cell seeding | Measure cell counts per well post-seeding. | Automate cell seeding and dispensing using systems like the MO:BOT platform for 3D cultures to ensure uniformity [5]. |

High Background or Low Signal in Reporter Gene Assays

Problem: The signal-to-noise ratio is low, making it difficult to distinguish true hits from background.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-specific reporter probe interaction | Run a no-cell control with the probe. | Switch to a different, more specific reporter system (e.g., use luciferase for its low background instead of fluorescence) [21]. |

| Promoter silencing or leakiness | Use qPCR to measure reporter mRNA levels. | Use a different, more stable promoter (e.g., EF1a instead of CMV) or an inducible system (e.g., tetracycline-on) for tighter control [25]. |

| Autofluorescence from compounds | Read plates before adding the reporter substrate. | Automate the steps for substrate addition and reading to ensure consistent timing across all wells [24]. |

Low Reproducibility in Morphological Profiles

Problem: Technical replicates of the same perturbation show low correlation, undermining downstream analysis.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent staining | Check fluorescence intensity distributions across plates and batches. | Automate all staining and washing steps using a liquid handler to standardize timing and volumes [24]. |

| Batch effects in image acquisition | Check for instrument drift or variations in lamp intensity. | Implement automated scheduling to ensure consistent imaging times post-perturbation. Use the same microscope settings across batches [5]. |

| Suboptimal feature extraction | Compare profiles generated by different segmentation parameters or models. | Replace traditional segmentation with a self-supervised learning (SSL) model like DINO, which provides segmentation-free, highly reproducible features [23]. |

Inconsistent Results in 3D Cell Culture Assays

Problem: High variability in organoid or spheroid size and viability, leading to unreliable data.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Manual handling damage | Visually inspect organoids before and after media changes. | Use an automated platform like the MO:BOT for gentle, standardized media exchange and quality control, rejecting sub-standard organoids before screening [5]. |

| Variable matrix composition | Assess polymerization consistency. | Automate the dispensing of extracellular matrix materials to ensure uniform volume and distribution in every well [5]. |

Essential Methodologies & Workflows

Detailed Protocol: A Differential Phenotypic Screen

This protocol is adapted from a screen identifying compounds with genotype-specific growth effects [6].

- Step 1: Experimental Design. Two genotypes (e.g., wild-type and a DNA repair mutant like

mus81) are used. The assay is designed to identify compounds that selectively inhibit the growth of the mutant. - Step 2: Automated Setup. Seeds or cells of both genotypes are dispensed into separate wells of 384-well plates using a liquid handler (e.g., I.DOT Non-Contact Dispenser) to ensure uniformity [24].

- Step 3: Compound Library Addition. A library of small molecules (e.g., the Prestwick library) is pin-transferred or dispensed into the plates.

- Step 4: Incubation and Imaging. Plates are incubated under controlled conditions. An automated imaging system acquires images of all wells at set time points.

- Step 5: AI-Powered Image Analysis.

- Traditional Workflow: Use CellProfiler to segment seedlings or cells and extract morphological features (area, eccentricity, intensity) [6].

- Advanced SSL Workflow: Use a pre-trained DINO model to extract powerful morphological features directly from the images without segmentation, reducing computational time and parameter tuning [23].

- Step 6: Hit Identification. Machine learning-based classifiers are trained on the extracted features to quantify growth. Hits are defined as compounds that significantly affect the mutant's growth while leaving the wild-type unaffected [6].

The logical workflow for experiment planning and troubleshooting is summarized below.

Quantitative Data for Assay Selection

The table below summarizes key characteristics of the main assay types to guide experimental design.

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput Phenotypic Assay Modalities

| Assay Type | Key Readout | Information Gained | Best for Automation | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viability/Proliferation | Cell count, metabolic activity | Gross cytotoxicity, anti-proliferative effect | Yes - homogeneous assays easily scaled [24] | Low mechanistic insight, can produce false positives/negatives [24] |

| Reporter Gene | Luminescence/Fluorescence intensity | Pathway-specific activity, target engagement [21] | Yes - plate reader friendly | Reporter context may not reflect native gene; potential for artifactual signals [25] |

| Morphological Profiling (Cell Painting) | High-dimensional image features | System-wide, unbiased MoA insight, off-target effects [23] | Yes, but data-heavy; requires automated image analysis [23] | Computationally intensive; MoA requires deconvolution [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Reagents for Automated Phenotypic Screening

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| I.DOT Liquid Handler | Non-contact, low-volume dispensing | Miniaturizing assays to 1536-well format, reducing reagent use by up to 90% [24] |

| MO:BOT Platform | Automated 3D cell culture handling | Standardizing organoid seeding, feeding, and quality control for reproducible 3D models [5] |

| CRISPR-GPT / AI Co-pilot | LLM-based experiment planning | Automating the design of CRISPR gene-editing experiments, including gRNA selection and protocol drafting [7] |

| Reporter Genes (Luciferase, GFP) | Surrogate for biological activity | Constitutively expressing GFP to track transfected cells; using luciferase under an inducible promoter to monitor pathway activation [21] |

| Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) Models (e.g., DINO) | Segmentation-free image feature extraction | Replacing CellProfiler for rapid, high-performance analysis of Cell Painting images [23] |

| copairs Python Package | Statistical framework for profile evaluation | Using mean average precision (mAP) to quantitatively evaluate phenotypic activity and similarity in profiling data [22] |

The integration of these tools into a cohesive, automated workflow is key to modern screening. The following diagram illustrates how they connect from experimental design to insight.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the major advantages of using automated midbrain organoids over traditional 2D cultures for chemical genetic screens?

Automated midbrain organoids (AMOs) offer significant advantages for screening, primarily through enhanced physiological relevance and scalability. The key differences are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of 2D Cultures and Automated 3D Midbrain Organoids for Screening

| Aspect | 2D Models | Automated 3D Midbrain Organoids |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological Relevance | Low: Lacks 3D architecture and native tissue organization [26] | High: Recapitulates human midbrain tissue organization and cell-matrix interactions [26] [27] |

| Disease Phenotypes | Often requires artificial induction of pathology (e.g., α-synuclein) [26] | Can exhibit spontaneous, disease-relevant pathology (e.g., α-synuclein/Lewy body formation) [26] |

| Throughput & Scalability | High throughput; low cost [26] | Scalable to medium/high-throughput using automated liquid handlers; higher cost per sample [26] [27] |

| Reproducibility | High (standardized protocols) [26] | High when using automated workflows, minimizing batch-to-batch heterogeneity [27] |

| Key Utility in Screening | Initial target validation, high-throughput toxicity assays [26] | Pathogenesis studies, phenotypic drug screening in a human-relevant context [26] [28] |

FAQ 2: Our organoids show high batch-to-batch variability, affecting our screen's reproducibility. How can we address this?

High variability often stems from manual handling inconsistencies. The primary solution is implementing a standardized, automated workflow.

- Utilize Automated Liquid Handlers: Systems from companies like Tecan or Beckman Coulter can perform all pipetting, media exchanges, and cell seeding with robotic precision, drastically reducing human error [5] [27].

- Adopt a Homogeneous Protocol: Use protocols specifically designed for homogeneity. For example, generating organoids in V-bottom 96-well plates promotes the consistent formation of uniform aggregates [27].

- Incorporate Quality Control (QC) Checkpoints: Implement automated imaging and analysis to assess organoid size and morphology before they enter a screening assay. Technologies like the MO:BOT platform can automatically reject sub-standard organoids, ensuring only high-quality models are screened [5].

FAQ 3: How can we efficiently analyze thousands of organoid images from a high-content screen?

Manual image analysis is a major bottleneck. Leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning is the recommended strategy.

- Employ Deep Learning Models: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), particularly U-Net architectures, are highly effective for segmenting organoids from bright-field or phase-contrast images without the need for fluorescent dyes [29]. These tools can automatically quantify organoid count, size, and shape across large image sets.

- Use Available Software: Open-source tools like CellProfiler (which can integrate U-Net) or OrganoidTracker are designed for such high-throughput analysis [29] [30].

- Focus on Functional Assays: For specific screens, you can use AI to quantify functional responses. For instance, in cystic fibrosis research, algorithms automatically measure forskolin-induced swelling (FIS) of organoids, a functional readout of CFTR channel activity [29]. A similar approach can be adapted for neuronal activity or toxicity readouts in midbrain organoids.

FAQ 4: Our organoids develop hypoxic cores, leading to cell death. How can we improve their health and maturation?

Hypoxic cores are a common challenge in larger 3D structures due to the lack of vasculature.

- Optimize Organoid Size: Generate smaller, more uniform organoids. Automated platforms that use 96-well V-bottom plates naturally produce organoids of a more controlled and manageable size, which improves nutrient penetration [27].

- Incorporate Agitation: Using bioreactors or orbital shaking during culture can enhance medium perfusion around the organoid, improving oxygen and nutrient exchange [28].

- Future Directions: The field is moving towards integrating vascular networks. This can be achieved by co-culturing organoids with endothelial cells or by fusing midbrain organoids with separately induced vascular organoids to create a perfusable blood-brain barrier-like system [26] [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Yield of Dopaminergic Neurons

Issue: After differentiation, the proportion of Tyrosine Hydroxylase-positive (TH+) dopaminergic (DA) neurons is lower than expected.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause A: Inefficient Patterning. The initial induction of a midbrain fate was not optimal.

- Solution: Ensure the precise timing and concentration of patterning molecules. The standard protocol uses SMAD inhibition (e.g., LDN-193189, SB431542) combined with WNT activation (CHIR-99021) and SHH activation (e.g., Smoothened Agonist, SAG) to direct cells toward a floor-plate and midbrain DA neuron fate [26] [27]. Verify the activity and storage of these small molecules.

- Cause B: Poor Neuronal Maturation.

- Solution: Supplement the maturation medium with key neurotrophic factors essential for DA neuron survival and maturation, specifically Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and Glial cell line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF) [26] [27]. The protocol should include these factors for several weeks.

Problem 2: Automated Image Analysis Fails to Segment Organoids Accurately

Issue: The AI model does not correctly identify the boundaries of all organoids, leading to inaccurate size or count data.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause A: Model Trained on Non-Representative Data.

- Solution: Retrain or fine-tune the deep learning model (e.g., U-Net) on your own set of annotated organoid images. This teaches the algorithm the specific morphology and appearance of your midbrain organoids. As demonstrated in respiratory organoid research, creating a custom dataset of 827 annotated images significantly boosted algorithm accuracy (IoU score of 0.8856) [29].

- Cause B: Suboptimal Image Quality or Acquisition.

- Solution: Standardize image acquisition. Use z-stack fusion (combining multiple focal planes) to ensure the entire 3D structure is in focus for analysis. Ensure consistent brightness and contrast across all images [29].

Problem 3: Inconsistent Cell Seeding During Automated Setup

Issue: The initial cell aggregation in 96-well plates is uneven, leading to organoids of vastly different sizes.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause A: Inaccurate Cell Counting or Clumping.

- Solution: Before seeding, create a single-cell suspension of high viability. Using Accutase for dissociation and passing the cells through a strainer can help. Count cells with an automated counter for accuracy and adjust the concentration precisely, as recommended in the AMO protocol (e.g., 5,000-9,000 cells per well in a V-bottom plate) [27].

- Cause B: Improper Plate Agitation.

- Solution: After seeding, ensure the plates are placed on a stable, level surface in the incubator. Any vibration or tilt can cause cells to aggregate unevenly. The static culture condition is critical for the cells to settle and form a single, uniform aggregate in the bottom of each well [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Midbrain Organoid Generation

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| smNPCs (small molecule Neural Precursor Cells) | A standardized, precursor cell type optimized for robust and rapid neural differentiation; ideal for automated workflows due to predictable growth [27]. | Alternative starting cells are iPSCs, but these may require more complex handling. |

| Patterning Molecules (CHIR-99021, SAG) | Directs regional identity. CHIR-99021 (WNT activator) and SAG (SHH agonist) pattern the organoids toward a midbrain floor-plate fate, the source of DA neurons [26] [27]. | Critical for achieving a specific midbrain identity, not just a generic neuronal culture. |

| Neurotrophic Factors (BDNF, GDNF) | Support the survival, maturation, and maintenance of dopaminergic neurons in the matured organoids [26] [27]. | Essential for long-term culture and functional maturation. |

| V-Bottom 96-Well Plates | Specialized plates that force cells to aggregate into a single, spatially confined spheroid at the well bottom, ensuring uniformity across the plate [27]. | A key to achieving high homogeneity in automated protocols. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Robotic system (e.g., from Tecan, Beckman Coulter) that performs repetitive tasks (seeding, feeding) with unparalleled precision, ensuring reproducibility for screens [5] [27]. | The core hardware for automation. |

| AI-Based Image Analysis Software | Software (e.g., CellProfiler with U-Net, OrganoidTracker) that automatically quantifies organoid morphology and functional responses from hundreds of images, enabling high-content screening [29] [30]. | Replaces slow, subjective manual analysis. |

Experimental Workflow & Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Automated Midbrain Organoid Generation Workflow

Diagram 2: Key Signaling Pathways for Midbrain Patterning

Leveraging Machine Learning for Image Segmentation and Phenotype Classification

This technical support center is designed for researchers conducting chemical genetic screens, where high-throughput microscopy generates vast amounts of image data. The core challenge lies in accurately identifying cellular components (segmentation) and categorizing the resulting morphological changes (phenotype classification) to elucidate mechanisms of action (MOA) for genetic or chemical perturbations. Machine learning (ML), particularly deep learning, has become an indispensable tool for automating these complex analytical tasks, moving beyond the limitations of classical image processing. This resource provides targeted troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and methodological protocols to help you integrate ML into your image-based profiling workflows efficiently [31] [32].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary machine learning approaches for image-based cellular profiling?

Two main approaches exist. The first is segmentation-based feature extraction, which uses classical computer vision or ML-based models to identify cellular boundaries, followed by the calculation of hand-engineered morphological features (size, shape, texture, intensity). These features are then used for downstream classification with models like Support Vector Machines or Random Forests. The second is segmentation-free or deep learning-based feature extraction, which uses deep neural networks, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), to learn relevant features directly from image pixels. These learned features can be used for classification and often provide a more hypothesis-free profiling method [31] [33].

Q2: My model performs well on training data but poorly on new images. What could be the cause?

This is typically a problem of overfitting or domain shift. Overfitting occurs when the model learns the noise and specific artifacts of the training data rather than generalizable biological features. Domain shift can arise from technical variations such as:

- Different imaging conditions (microscope, lighting, focus).

- Variations in staining protocols or dye batches.

- Changes in cell culture conditions or passage number.

To mitigate this, ensure you apply regularization techniques (e.g., dropout), use data augmentation (random rotations, flips, brightness adjustments), and, most critically, include data from multiple experimental batches in your training set. Hold back part of your data for validation to monitor performance on unseen data [32].

Q3: How can I use image-based profiling to identify a compound's mechanism of action (MOA)?

The fundamental principle is that perturbations targeting the same biological pathway often induce similar morphological profiles. To identify an unknown MOA:

- Generate a Reference Set: Create a large dataset of cells treated with compounds of known MOA or with genetic perturbations (e.g., CRISPR knockouts).

- Compute Profiles: Extract morphological profiles (using either hand-engineered or deep-learning features) for all perturbations, including your compound of unknown MOA.

- Cluster and Compare: Use similarity metrics (e.g., cosine similarity) or machine learning classifiers to cluster the unknown compound's profile with profiles of known perturbations. A close association with a known MOA cluster suggests a shared biological target or pathway [31] [33].

Q4: What are the data requirements for training a deep learning model for this application?

Deep learning models are data-hungry. The requirements vary but generally include:

- Volume: Thousands to tens of thousands of annotated cells or hundreds of well-level images are often necessary for robust performance.

- Quality: Data must be accurately labeled and of high quality. Inconsistent or noisy data is a major bottleneck.

- Diversity: The training data should encompass the expected biological and technical variability (e.g., different cell densities, slight staining variations) to ensure the model generalizes well. For smaller datasets, consider using transfer learning, where a model pre-trained on a large, general image dataset is fine-tuned on your specific biological data [34] [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Poor Image Segmentation Accuracy

Problem: The model fails to accurately identify and outline individual cells or subcellular structures.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Training Data | Check the number of annotated cells in your training set. | Annotate more data. Use data augmentation techniques (rotation, scaling, elastic deformations) to artificially expand your dataset. |