Advanced Cell-Free DNA NGS Workflows: Integrating Chemogenomic Biomarkers for Precision Oncology

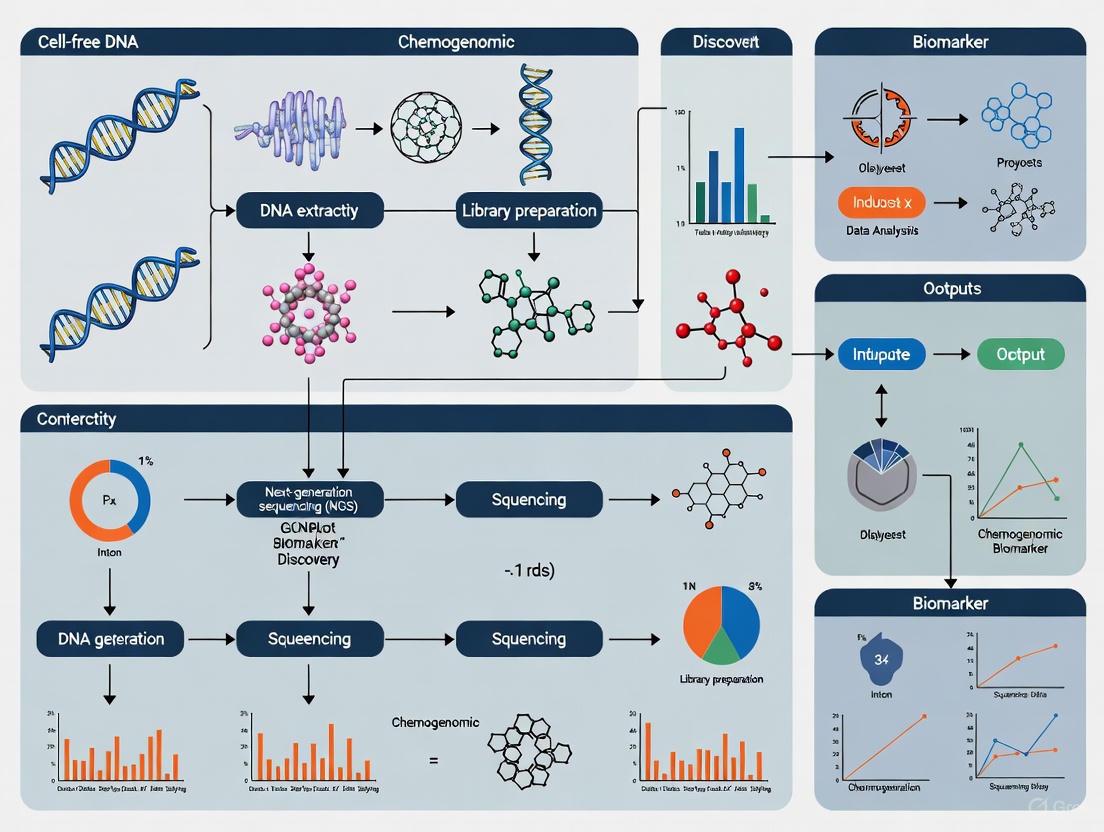

This comprehensive review explores the integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) workflows for cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis to unlock chemogenomic biomarkers in precision oncology.

Advanced Cell-Free DNA NGS Workflows: Integrating Chemogenomic Biomarkers for Precision Oncology

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) workflows for cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis to unlock chemogenomic biomarkers in precision oncology. It covers the fundamental biology of cfDNA release mechanisms and fragmentation patterns, details established and emerging methodological approaches from targeted panels to whole-genome sequencing, and addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for pre-analytical variables and computational challenges. The article further provides a framework for analytical validation and comparative performance assessment of various cfDNA assays, including tumor-informed and tumor-agnostic methods. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource aims to guide the robust implementation of liquid biopsy workflows to accelerate biomarker discovery and therapeutic monitoring.

The Biology of Cell-Free DNA and Its Role as a Chemogenomic Mirror

The analysis of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) has become a cornerstone of liquid biopsy approaches in clinical oncology and chemogenomic biomarker research. The composition and fragmentation patterns of cfDNA in circulation are direct consequences of its cellular origins and the mechanisms by which it is released. Understanding these release mechanisms—primarily apoptosis, necrosis, and active secretion—is crucial for interpreting cfDNA data in drug development workflows. This protocol details the experimental approaches for characterizing these pathways and their implications for next-generation sequencing (NGS) analyses in biomarker discovery.

Comparative Mechanisms of Cellular DNA Release

The primary pathways of DNA release differ significantly in their regulation, morphological features, and resulting cfDNA characteristics. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these mechanisms:

Table 1: Characteristics of Major cfDNA Release Mechanisms

| Feature | Apoptosis | Necrosis | Active Secretion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulation | Programmed, caspase-dependent [1] | Accidental or regulated (necroptosis) [2] [3] | Constitutive or triggered [4] |

| Inducing Stimuli | Developmental cues, DNA damage, cytotoxic drugs [5] | Infection, toxins, physical trauma [2] | Cellular signaling, differentiation [4] |

| Key Molecular Mediators | Caspases, CAD/DFF40, BCL2 family [1] [6] | RIPK1/RIPK3 (necroptosis), membrane rupture [3] | SNARE proteins, porosomes [4] |

| Membrane Integrity | Maintained until late stages; blebbing [2] | Lost; release of intracellular contents [2] [3] | Vesicle-mediated; membrane incorporated [4] |

| Inflammatory Response | Minimal ("silent" removal) [1] | Significant (release of DAMPs) [3] | Variable (depends on cargo) |

| Typical cfDNA Fragment Size | ~167 bp multi-mers (nucleosomal pattern) [6] | Larger, heterogeneous fragments (>1,000 bp) [6] | Larger fragments, often vesicle-protected [6] |

| Immunogenicity | Generally low, can be tolerogenic [3] | High (immunogenic cell death) [3] | Context-dependent |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating cfDNA Release

Protocol: In Vitro cfDNA Release Profiling

Purpose: To quantify and characterize the fragmentation profile of cfDNA released from cultured cells, allowing for the inference of the dominant release mechanism.

Background: A 2024 study profiling 24 human cell lines revealed two distinct cfDNA fragmentation patterns: a "left-skewed" pattern with a peak at ~167 bp (associated with apoptosis) and a "right-skewed" pattern with a peak >1,000 bp (associated with necrosis/vesicular release) [6].

Reagents and Materials:

- Cell lines of interest (e.g., MCF-10A, MCF-7)

- Appropriate cell culture media and supplements

- Serous or similar low-DNA background serum

- DNase/RNase-free tubes and pipette tips

- cfDNA extraction kit (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit)

- High Sensitivity DNA Analysis Kit (e.g., for Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation)

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR) system or droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Conditioning:

- Seed cells at a standardized density (e.g., 1x10^6 cells per T-75 flask) in complete media.

- Allow cells to adhere overnight.

- Replace media with fresh media and culture cells without media changes for 1-3 days. Include biological replicates for each time point.

Sample Collection:

- At each time point (e.g., Day 1, 2, 3), carefully collect the conditioned media into a centrifuge tube.

- Centrifuge media at 2,000 x g for 10 minutes to pellet any detached cells or large debris.

- Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and centrifuge at 16,000 x g for 10 minutes to remove smaller particles.

cfDNA Isolation:

- Extract cfDNA from the clarified supernatant using a dedicated cfDNA extraction kit, strictly following the manufacturer's protocol.

- Elute the cfDNA in a small volume (e.g., 20-50 µL) of the provided elution buffer.

cfDNA Quantification and Fragmentomics Analysis:

- Quantify the total yield of cfDNA using a fluorescence-based method (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay).

- Analyze the fragment size distribution using a High Sensitivity DNA kit on an Agilent Bioanalyzer or similar platform. This will determine if the profile is "left-skewed" (apoptotic) or "right-skewed" (necrotic/vesicular).

Interpretation: A dominant peak at ~167 bp with a laddering pattern is indicative of apoptosis, while a profile enriched for fragments >1,000 bp suggests a significant contribution from necrosis or active vesicular release [6].

Protocol: CRISPR-Based Genetic Screening for cfDNA Regulators (cfCRISPR)

Purpose: To identify genes that functionally regulate the release of cfDNA, providing mechanistic insight into the dominant pathways active in a given cell type.

Background: This novel screening strategy leverages the fact that sgRNA barcodes integrated into a cell's genome are shed proportionally into cfDNA. Knocking out a gene that regulates cfDNA release will alter the sgRNA's representation in the cfDNA pool relative to the cellular genome [6].

Reagents and Materials:

- Lentiviral genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 sgRNA library

- Target cell line with high cfDNA release (e.g., MCF-10A)

- Polybrene or other transduction enhancers

- Puromycin or other appropriate selection antibiotic

- cfDNA and gDNA extraction kits

- Next-generation sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Library Transduction:

- Transduce the target cell line with the lentiviral sgRNA library at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA.

- Select transduced cells with puromycin for 5-7 days.

Sample Harvesting:

- Culture the selected cell pool without media changes for 3 days to allow cfDNA accumulation.

- Harvest conditioned media for cfDNA isolation (as in Protocol 3.1).

- In parallel, harvest a portion of the cells for genomic DNA (gDNA) extraction.

Sequencing Library Preparation:

- Amplify the sgRNA barcode regions from both the cfDNA and cellular gDNA samples using PCR with indexing primers.

- Purify the PCR products and quantify the libraries.

High-Throughput Sequencing and Analysis:

- Sequence the cfDNA and gDNA libraries on an NGS platform to a sufficient depth.

- Map the sequenced reads to the sgRNA library reference to count the abundance of each sgRNA in both the cfDNA and gDNA samples.

- For each sgRNA, calculate a "cfDNA release ratio" (e.g., normalized reads in cfDNA / normalized reads in gDNA).

- Compare this ratio to the population average. sgRNAs targeting genes that positively regulate cfDNA release will be depleted in cfDNA, while those targeting negative regulators will be enriched.

Interpretation: Genes involved in apoptotic pathways (e.g., FADD, BCL2L1) are frequently identified as top hits, genetically validating apoptosis as a primary mediator of cfDNA release [6].

Signaling Pathways in DNA Release

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways that lead to DNA release via apoptosis and necroptosis, highlighting points of crosstalk and experimental intervention.

Diagram Title: Signaling Pathways in Programmed and Accidental Cell Death

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents essential for investigating cfDNA release mechanisms in a chemogenomic context.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for cfDNA Release Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant TRAIL | Inducer of extrinsic apoptosis [6] | Stimulate caspase-8 mediated apoptosis to increase apoptotic cfDNA yield. |

| Pan-Caspase Inhibitor (e.g., Z-VAD-FMK) | Inhibits executioner caspases [1] | Confirm caspase-dependent cfDNA release; distinguish apoptosis from necroptosis. |

| Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) | Selective inhibitor of RIPK1-mediated necroptosis [3] | Inhibit regulated necrosis to assess its contribution to total cfDNA pool. |

| Anti-CD27 / Anti-CD38 Antibodies | Cell surface capture of B cells/plasma cells [7] | Isolate specific immune cell populations for cell-type-specific cfDNA analysis. |

| Oligonucleotide-barcoded Antibodies | Link cell surface phenotype to transcriptome (CITE-seq) [7] | Correlate IgG secretion capacity (via SEC-seq) with transcriptional state in single cells. |

| Hydrogel Nanovials (e.g., for SEC-seq) | Platform for accumulating secretions from single cells [7] | Quantify immunoglobulin secretion from single B cells and link to surface markers/transcriptomes. |

| sgRNA Library for cfCRISPR | Genome-wide knockout screening [6] | Identify novel genetic regulators of cfDNA biogenesis and release. |

Application in Chemogenomic Biomarker Research

Integrating an understanding of cfDNA release mechanisms directly enhances NGS workflow design and data interpretation. The fragmentation pattern of cfDNA is not merely a byproduct but an rich source of biological information. For instance, a dominant ~167 bp peak suggests tumor cell death is primarily mediated by apoptosis, potentially in response to a therapeutic agent. In contrast, a shift towards a "right-skewed" profile with larger fragments in serial monitoring could indicate the emergence of treatment resistance via alternative cell death pathways or a change in the tumor microenvironment [6]. Furthermore, leveraging inducers of immunogenic cell death, which can involve specific forms of apoptosis or necrosis, may enhance the release of tumor neoantigens and improve the sensitivity of liquid biopsy assays [3]. The protocols outlined here provide a framework for researchers to deconvolute these signals, thereby refining the use of cfDNA as a dynamic biomarker in drug development.

Characteristic cfDNA Fragmentation Patterns and Nucleosomal Signatures

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis has emerged as a cornerstone of liquid biopsy, offering a non-invasive window into physiological and pathological processes. The nucleosomal organization of cfDNA imposes characteristic fragmentation patterns that are profoundly influenced by the chromatin landscape of the cell of origin. These patterns provide a rich source of biological information beyond genetic alterations, enabling insights into gene regulation, cell identity, and disease states. Within the context of chemogenomic biomarkers research, understanding these fragmentation signatures is paramount for developing sensitive diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive tools for therapeutic intervention. This document details the fundamental principles, analytical approaches, and practical protocols for investigating cfDNA fragmentation patterns and nucleosomal signatures in cancer and other diseases.

Core Principles of cfDNA Fragmentation

Circulating cfDNA fragments are generated through non-random processes primarily during cellular apoptosis and necrosis. The fragmentation is heavily influenced by the underlying chromatin structure, wherein DNA wrapped around nucleosomes is protected from nuclease digestion, while linker DNA is more susceptible to cleavage. This results in several key characteristics:

- Size Periodicity: cfDNA fragments display a prominent peak at ~166-167 base pairs (bp), corresponding to DNA wrapped around a single nucleosome plus a linker histone (a chromatosome), and show a 10.4-bp periodicity in the 100-160 bp range, reflecting the helical pitch of DNA around the nucleosome core [8].

- Nucleosome Footprints: The in vivo occupancy of nucleosomes in the tissue of origin is imprinted in the cfDNA fragmentation pattern. DNA within open chromatin regions is more susceptible to fragmentation, while nucleosome-bound DNA is protected [9] [8].

- Transcription Factor Footprinting: Very short cfDNA fragments have been found to harbor footprints of transcription factors, revealing the binding sites of these regulatory elements in the cells from which the cfDNA originated [8].

Quantitative Landscape of cfDNA Fragmentation Metrics

Multiple computational metrics have been developed to quantify cfDNA fragmentation patterns. The performance of these metrics varies, and an integrated approach often yields the most robust results. The table below summarizes key fragmentation patterns and their diagnostic performance.

Table 1: Performance of Different cfDNA Fragmentation Metrics in Cancer Detection

| Fragmentation Metric | Description | Category | Reported Performance (AUROC) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| End Motif (EDM) [9] | Analysis of the frequency of 4-mer sequences at fragment ends | Fragment sequence | 0.943 (Cross-validation) | Highest single diagnostic value in cross-validation; less stable in independent validation |

| Normalized Read Depth [10] | Fragment counts normalized to sequencing depth and region size | Fragment number | 0.943-0.964 (Avg. for cancer type prediction) | Top-performing metric on targeted panels; robust across cohorts |

| Fragment Dispersity Index (FDI) [11] | Integrates distribution of fragment ends with coverage variation | Hybrid (length & coverage) | Robust performance in early cancer diagnosis | Strongly correlates with chromatin accessibility; enables subtyping and prognosis |

| Windowed Protection Score (WPS) [9] [8] | Quantifies nucleosome protection in a sliding window | Hybrid (length & coverage) | Robust predictive capacity | Infers genome-wide nucleosome occupancy; generalizes well in validation |

| Integrated Fragmentation Pattern (IFP) [9] | Ensemble classifier combining 10 fragmentation patterns | Ensemble | Notable improvement over single patterns | Enhances cancer detection and tissue-of-origin determination; improves stability |

Different metrics are suited for various sequencing approaches. A recent study comparing fragmentomics on targeted panels versus whole-genome sequencing found that normalized fragment read depth across all exons provided the best overall performance for predicting cancer types and subtypes on targeted panels, with an average AUROC of 0.943 in one cohort and 0.964 in another [10]. Furthermore, combining multiple fragmentation patterns into an ensemble classifier (e.g., Integrated Fragmentation Pattern) has been shown to yield more stable and powerful performance for cancer detection and tissue-of-origin determination than any single pattern [9].

Experimental Protocols for Fragmentomics Analysis

Protocol: Genome-Wide Nucleosome Profiling using the Windowed Protection Score (WPS)

Principle: The WPS quantifies nucleosome protection by calculating, for a given genomic coordinate, the number of DNA fragments spanning a 120 bp window minus the number of fragments with an endpoint within that window. Protected nucleosomal regions show a high WPS, while nucleosome-depleted regions (e.g., transcription factor binding sites) show a low or negative WPS [8].

Workflow:

Sample Preparation & Sequencing:

- Isolate cfDNA from plasma using a circulating nucleic acid kit (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit).

- Prepare sequencing libraries without fragmentation or with minimal amplification to preserve native fragment length distributions. Both double-stranded and single-stranded library preparation methods can be used, with the latter offering better recovery of short fragments [8].

- Perform whole-genome sequencing. For nucleosome footprinting, a range of coverages can be effective, from high coverage (e.g., 30x) down to ultra-low-pass (0.1x) [12] [13].

Bioinformatic Processing:

- Align sequencing reads to the reference genome (e.g., hg19/hg38).

- Extract the genomic coordinates of both ends for each aligned fragment.

- Calculate the WPS across the entire genome using a sliding window approach. The formula for a base i is:

WPS(i) = (# of fragments spanning the window [i-60, i+60]) - (# of fragments with an endpoint within [i-60, i+60]). - Call nucleosome positions by identifying local maxima in the WPS profile.

Downstream Analysis:

- Aggregate WPS profiles around genomic features of interest (e.g., transcription start sites, specific transcription factor binding sites).

- Correlate WPS patterns with public epigenetic datasets (e.g., DNase I hypersensitivity, ATAC-seq) to validate inferred chromatin accessibility.

Protocol: Chromatin Accessibility Analysis via Fragmentomics in Open Chromatin Regions

Principle: This protocol leverages the fact that cfDNA within open chromatin regions is more susceptible to fragmentation. It involves calculating various fragmentation metrics specifically within predefined open chromatin regions to enhance signal-to-noise ratio in diagnostic models [9].

Workflow:

Define Open Chromatin Regions:

- Compile a set of open chromatin regions from relevant cell types. This can be sourced from public databases like ENCODE or Roadmap Epigenomics, or from cell-type-specific ATAC-seq or DNase-seq data. Key contributors to cfDNA include B cells, T cells, monocytes, and neutrophils [9].

Feature Calculation:

- From the aligned cfDNA sequencing data, compute multiple fragmentation features within the defined open chromatin regions. Key features include [9]:

- Fragment Length: Mean/median fragment size.

- Fragment Coverage: Number of fragment midpoints.

- End Motif (EDM): Frequency of specific 4-mer sequences at fragment ends.

- Orientation-aware Fragmentation (OCF): Strand-wise sequencing coverage patterns.

- Integrated Fragmentation Score (IFS): A composite score derived from multiple fragmentation features.

- From the aligned cfDNA sequencing data, compute multiple fragmentation features within the defined open chromatin regions. Key features include [9]:

Model Building and Validation:

- Use machine learning (e.g., elastic net, random forest) to train a classification model (cancer vs. healthy) using the computed fragmentation features as input.

- Employ cross-validation and validate the model on independent datasets to ensure generalizability.

- For enhanced stability and performance, integrate all fragmentation patterns into an ensemble classifier [9].

Protocol: Tissue-of-Origin Analysis using Single-Cell Reference Profiles

Principle: This approach correlates cfDNA-inferred nucleosome spacing with gene expression profiles from a comprehensive single-cell RNA sequencing atlas to rank the relative contribution of hundreds of cell types to the plasma cfDNA pool [13].

Workflow:

Nucleosome Signal Extraction:

- Perform whole-genome sequencing of cfDNA (can be ultra-low coverage, e.g., <0.3x).

- Calculate a nucleosome positioning signal, such as the Windowed Protection Score (WPS) or a Fourier Transform intensity at the 196-199 bp wavelength across gene bodies, which correlates with gene expression in the cell of origin [13].

Correlation with Reference Atlas:

- Obtain a single-cell transcriptome reference atlas encompassing a wide range of cell types (e.g., Tabula Sapiens, which includes over 490 cell types).

- For each cell type in the reference, correlate the average gene expression with the cfDNA-derived nucleosome signal (e.g., FFT intensity) across a large set of genes. A strong negative correlation indicates a higher contribution from that cell type.

Deconvolution and Interpretation:

- Rank all cell types in the reference by the strength of their correlation. In healthy individuals, immune cell types (monocytes, lymphocytes) and liver endothelial cells are typically top-ranked [13].

- In disease states (e.g., cancer), look for aberrantly up-ranked cell types that align with the disease biology (e.g., intestinal cells in colorectal cancer, plasma cells in multiple myeloma) [13].

Visualizing Workflows and Signaling Pathways

From Blood Draw to Nucleosome Profile

cfDNA Fragmentation Reflects Chromatin State

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for cfDNA Fragmentomics

| Item | Function/Application | Example Product/Note |

|---|---|---|

| cfDNA Isolation Kit | Purification of short, low-concentration cfDNA from plasma/serum. | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen). Critical for high yield and integrity. |

| Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT Tubes | Blood collection tubes that stabilize nucleosomal DNA and prevent genomic DNA release from blood cells. | Essential for preserving in vivo fragmentation profiles during sample transport. |

| Library Prep Kit for cfDNA | Construction of sequencing libraries from low-input, short-fragment DNA without bias. | KAPA HyperPrep Kit; NEB NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit. Protocols omitting fragmentation are key. |

| Enzymatic Methylation Conversion Kit | For simultaneous methylation and nucleosome occupancy profiling (cfNOMe). | NEBNext EM-Seq. Preserves fragmentation information better than bisulfite conversion [14]. |

| Targeted Gene Panels | For focused fragmentomics analysis on clinically relevant genes. | Panels from Tempus, Guardant, FoundationOne. Enable analysis on clinically available sequencing data [10]. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | For calculating fragmentation metrics (WPS, end motifs, coverage). | Custom scripts; Griffin framework (for GC-bias corrected nucleosome profiling) [12]. |

The analysis of characteristic cfDNA fragmentation patterns and nucleosomal signatures represents a powerful and rapidly advancing frontier in liquid biopsy. The protocols and data outlined herein provide a framework for integrating fragmentomics into chemogenomic biomarker research. By leveraging the rich epigenetic information encoded in the size, distribution, and ends of cfDNA fragments, researchers can gain unprecedented insights into tumor biology, disease heterogeneity, and treatment response, paving the way for more precise non-invasive diagnostics and monitoring.

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has emerged as a pivotal biomarker in precision oncology, offering a non-invasive window into tumor genomics. This analyte represents a minute fraction of the total cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in circulation, often constituting less than 0.1% in early-stage cancers, set against a background of cfDNA derived from normal cell apoptosis [15] [16]. The analysis of ctDNA within chemogenomic biomarker research provides critical insights for drug development, enabling real-time assessment of tumor dynamics, therapeutic response, and clonal evolution [17] [16]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) workflows are fundamental to unlocking the potential of this fractional biomarker, yet they present significant technical challenges. This document outlines detailed protocols and applications for ctDNA analysis, framed within the context of cfDNA NGS workflows for advanced chemogenomics research.

ctDNA Applications in Precision Oncology

The clinical utility of ctDNA spans the cancer care continuum, from early detection to monitoring treatment response. Its applications are particularly valuable in providing a comprehensive view of tumor heterogeneity, which is often limited by the spatial constraints of traditional tissue biopsies [16]. The table below summarizes the core applications of ctDNA analysis in solid tumors.

Table 1: Key Applications of ctDNA Analysis in Solid Tumors

| Application | Key Utility | Example Cancer Types | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Response Monitoring | Correlates with tumor burden; predicts radiographic response earlier than imaging [16]. | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Colorectal Cancer (CRC), Breast Cancer | A decline in ctDNA levels predicted radiographic response more accurately than follow-up imaging in NSCLC [15]. |

| Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Detection | Detects molecular relapse post-treatment, often months before clinical or radiographic recurrence [17] [15]. | NSCLC, Colorectal Cancer, Breast Cancer | In breast cancer, SV-based ctDNA assays detected molecular relapse months to years before clinical relapse [15]. |

| Therapy Selection & Genotyping | Identifies actionable genomic alterations (AGAs) to guide targeted therapy [17] [18]. | NSCLC (EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF, etc.) | Plasma-based NGS testing led to higher rates of guideline-recommended treatment (74% vs. 46%) [17]. |

| Resistance Mechanism Monitoring | Detects acquired mutations that confer resistance to targeted therapies, enabling timely treatment modification [15] [16]. | EGFR-mutant NSCLC (e.g., T790M) | In EGFR-mutant NSCLC, monitoring for the T790M resistance mutation allows for a switch to third-generation inhibitors without repeated tissue sampling [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for ctDNA Analysis

A robust ctDNA workflow requires meticulous attention from sample collection through data analysis. The following protocols detail the critical phases.

Pre-Analytical Phase: Sample Collection and Processing

The pre-analytical phase is critical, as variables here significantly impact cfDNA yield, integrity, and the success of downstream applications [19].

- Sample Collection: Collect blood using cell-stabilizing tubes (e.g., Streck, PAXgene). Standard K2EDTA tubes can be used if processing occurs within 1-4 hours of collection [19].

- Plasma Separation: Perform a double centrifugation protocol.

- First centrifugation: 800-1600 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma from cellular components.

- Transfer the supernatant to a fresh tube without disturbing the buffy coat.

- Second centrifugation: 16,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove any residual cells.

- Plasma Storage: Immediately aliquot the cleared plasma and store at -80°C to prevent degradation. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles.

- cfDNA Extraction: Use high-sensitivity, magnetic bead-based cfDNA extraction kits. These methods offer high recovery rates, consistency, and are amenable to automation, which is crucial for reproducibility [19]. Validate the extraction system using synthetic cfDNA reference materials spiked into DNA-free plasma to confirm recovery efficiency and specificity.

Analytical Phase: Library Preparation and Sequencing

This phase converts isolated cfDNA into sequence-ready libraries, with specific adaptations for low-input, fragmented material.

Library Preparation:

- Fragmentation: Typically unnecessary as cfDNA is already fragmented (~167 bp). Proceed directly to end-repair and A-tailing [20].

- Adapter Ligation: Use platform-specific adapters (e.g., Illumina P5/P7) with dual-indexing to enable sample multiplexing and reduce index hopping. Incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) during adapter ligation. UMIs are short random nucleotide sequences that tag individual DNA molecules before amplification, allowing for bioinformatic error correction and distinguishing true low-frequency variants from PCR/sequencing artifacts [16].

- Size Selection: Employ bead-based clean-up to enrich for the mononucleosomal cfDNA fraction (~150-170 bp) and remove longer genomic DNA contaminants and adapter dimers. This step enriches the ctDNA fraction and increases the detection yield of low-frequency variants [15].

- Library Amplification: Use a low-cycle, high-fidelity PCR to amplify the library. Excess cycles can exacerbate duplication rates and bias.

Sequencing:

- Platform: Use an Illumina-based NGS platform for massively parallel sequencing.

- Sequencing Depth: For ctDNA variant detection, especially in MRD settings, ultra-deep sequencing (>50,000x coverage) is mandatory to detect variants with a variant allele frequency (VAF) of <0.1% [15] [21].

- Chemistry: Sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible terminators is the standard [20].

Post-Analytical Phase: Bioinformatic Processing

The bioinformatic pipeline transforms raw sequencing data into actionable results.

- Primary Analysis:

- Base Calling: Convert raw signal data (e.g., Illumina .bcl files) into nucleotide sequences.

- Demultiplexing: Assign reads to individual samples based on their unique dual indices.

- Secondary Analysis:

- Read Trimming & UMI Consensus Building: Trim adapter sequences and group reads by their UMI and alignment coordinates. Generate a consensus sequence for each original DNA molecule to correct for random sequencing errors [16].

- Alignment: Map quality-filtered reads to a reference human genome (e.g., GRCh38).

- Variant Calling: Use specialized algorithms tuned for low-VAF variants. For tumor-informed MRD assays, specifically monitor the mutations identified in the patient's prior tumor tissue sample [17] [21]. The limit of detection for validated assays can reach a VAF of 0.0024% [21].

Table 2: Essential Quality Control Checkpoints in the ctDNA Workflow

| Workflow Stage | QC Parameter | Target Metric | QC Method/Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Isolation | cfDNA Concentration | >0.1 ng/μL (highly sample-dependent) | Fluorometry (e.g., Qubit, EzCube) [22] |

| cfDNA Integrity | Dominant peak at ~167 bp | TapeStation, Bioanalyzer [19] | |

| Genomic DNA Contamination | Absence of high molecular weight smear (>500 bp) | Electrophoresis [22] | |

| Library Preparation | Library Concentration | Within dynamic range of sequencer | qPCR-based quantification [20] |

| Library Fragment Size | ~200-300 bp (cfDNA + adapters) | TapeStation, Bioanalyzer | |

| Sequencing | Cluster Density | As per platform specification | Sequencing platform output |

| Q30 Score | >80% | Sequencing platform output | |

| Mean Coverage Depth | >50,000x for low-VAF detection | Alignment software (e.g., BWA, GATK) |

The following diagram illustrates the complete end-to-end workflow for ctDNA analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful ctDNA analysis relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table catalogs key solutions for the featured workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ctDNA Analysis

| Item | Function | Example Types & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Stabilizing Blood Collection Tubes | Preserves blood sample integrity by preventing white blood cell lysis and release of genomic DNA, which dilutes ctDNA fraction. | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT, PAXgene Blood cDNA Tube [19]. |

| Magnetic Bead-Based cfDNA Kits | Isolate and purify cfDNA from plasma with high efficiency and reproducibility; amenable to automation. | Kits from QIAGEN, Circulomics, Norgen Biotek [19]. |

| Reference Standard Materials | Act as process controls for validating extraction efficiency, assay sensitivity, and variant detection accuracy. | Seraseq ctDNA, AcroMetrix ctDNA, nRichDx cfDNA [19]. Contains predefined mutations at specific VAFs. |

| NGS Library Prep Kits (UMI) | Prepare fragmented cfDNA for sequencing while incorporating molecular barcodes for error correction. | Kits from QIAGEN (QIAseq), Bio-Rad, Swift Biosciences [16] [21]. |

| Fluorometers & Spectrophotometers | Precisely quantify low-concentration nucleic acid samples and assess purity. | Combination of EzCube Fluorometer (sensitivity) and EzDrop Spectrophotometer (purity check) is recommended [22]. |

| Targeted NGS Panels | Hybrid-capture or amplicon-based panels for deep sequencing of cancer-associated genes. | Panels covering key NSCLC drivers (EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF, etc.) [17] [18]. |

The journey of analyzing ctDNA—a fractional signal in a vast background of normal cfDNA—demands a rigorously standardized and highly sensitive workflow. From the initial blood draw to the final bioinformatic interpretation, each step must be optimized for the unique challenges posed by this analyte. The protocols and tools outlined here provide a foundation for generating reliable, actionable data in chemogenomic biomarker research. As ctDNA technologies continue to evolve, with advancements in fragmentomics, methylation analysis, and ultrasensitive assays, their integration into standardized NGS workflows will further solidify the role of liquid biopsy in accelerating precision oncology and drug development.

Application Notes

Liquid biopsy has emerged as a transformative tool in oncology research, providing a minimally invasive means to interrogate tumor heterogeneity and dynamics in real-time. By analyzing circulating tumor-derived components, researchers and drug developers can access a comprehensive view of the total tumor burden, overcoming the limitations of traditional tissue biopsies that often fail to capture spatial and temporal heterogeneity [23] [24].

Key Analytical Targets in Liquid Biopsy

The clinical and research utility of liquid biopsy stems from multiple complementary analytes that provide distinct yet overlapping information about tumor biology:

Table 1: Core Liquid Biopsy Biomarkers and Their Research Applications

| Analyte | Key Characteristics | Primary Research Applications | Detection Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) | Short DNA fragments (20-50 bp); half-life <2 hours; represents 0.1-1.0% of total cfDNA [25] [26] | Treatment response monitoring; MRD detection; early relapse prediction; identifying resistance mutations [23] [27] | Low abundance in early-stage disease; requires highly sensitive detection methods [28] |

| Cell-Free DNA (cfDNA) | Double-stranded fragments (80-200 bp); baseline concentration 1-10 ng/mL in healthy individuals [26] | Cancer screening; monitoring tumor dynamics; assessing total cellular turnover | Background from hematopoietic system; elevated in various non-malignant conditions [26] |

| Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) | Rare cells (1-50 CTCs per 7.5mL blood); metastatic potential; half-life 1-2.5 hours [25] [29] | Studying metastasis mechanisms; drug resistance mechanisms; single-cell analysis | Extreme rarity; requires sophisticated enrichment technologies [25] [29] |

| DNA Methylation Markers | Stable epigenetic modifications; emerge early in tumorigenesis; tissue-specific patterns [28] [29] | Early cancer detection; tissue-of-origin identification; cancer subtyping | Requires bisulfite conversion or enzymatic treatment; complex bioinformatics [28] |

Capturing Tumor Heterogeneity

Liquid biopsy excels at resolving spatial and temporal tumor heterogeneity, which represents a significant challenge for traditional tissue sampling. A 2025 comparative analysis demonstrated that liquid biopsies capture between 33-92% of variants identified across multiple metastatic lesions, with some mutations exclusively detected in liquid biopsy [24]. This comprehensive profiling capability enables researchers to track clonal evolution under therapeutic selective pressure.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Liquid Biopsy in Capturing Heterogeneity

| Parameter | Tissue Biopsy | Liquid Biopsy | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Coverage | Single lesion/site [24] | Multiple lesions simultaneously [23] [24] | More representative drug response assessment |

| Temporal Resolution | Limited by invasiveness [25] | Real-time monitoring (serial sampling) [23] [27] | Dynamic tracking of resistance mechanisms |

| Variant Detection | 4-12 mutations per patient (post-mortem tissue) [24] | 4-17 mutations per patient (pre-mortem LBx) [24] | Identification of dominant resistance clones |

| Variant Allele Frequency | 1.5-71.4% (tissue) [24] | 0.2-31.1% (LBx) [24] | Sensitivity to minor subclones with emerging resistance |

Clinical Translation and Validation

The transition of liquid biopsy from research to clinical applications requires rigorous validation. Current research focuses on standardizing pre-analytical variables, improving analytical sensitivity, and demonstrating clinical utility across diverse cancer types. As of 2025, multiple US-registered clinical trials are recruiting patients to validate liquid biopsy applications in immunotherapy monitoring, with 20 trials actively recruiting and 5 not yet recruiting [23].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Comprehensive ctDNA NGS Workflow for Chemogenomic Biomarker Discovery

Principle: This protocol describes an end-to-end workflow for isolation, preparation, and sequencing of ctDNA from patient plasma to identify genetic and epigenetic biomarkers relevant to drug response and resistance.

Sample Collection and Processing

Materials:

- K₂EDTA or Streck Cell-Free DNA Blood Collection Tubes

- Refrigerated centrifuge capable of 1600-2500 × g

- Plasma aspiration tools (serological pipettes or automated liquid handlers)

- -80°C freezer for plasma storage

Procedure:

- Blood Collection: Draw 10-20 mL whole blood into appropriate collection tubes. Invert gently 8-10 times.

- Initial Processing: Process within 2-4 hours of collection. Centrifuge at 1600-2500 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- Plasma Separation: Carefully transfer supernatant plasma to sterile tubes without disturbing buffy coat.

- Secondary Centrifugation: Centrifuge plasma at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove residual cells.

- Aliquoting and Storage: Transfer cleared plasma to cryovials and store at -80°C until DNA extraction.

Critical Considerations:

- Consistent processing time is essential to prevent leukocyte lysis and background cfDNA increase.

- Avoid freeze-thaw cycles which degrade cfDNA integrity.

- Document time-from-collection-to-processing for quality control.

Cell-Free DNA Extraction and Quantification

Materials:

- Commercial cfDNA extraction kit (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit)

- Magnetic bead-based purification systems

- Fluorometric quantitation system (Qubit dsDNA HS Assay)

- Fragment analyzer (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer, TapeStation)

Procedure:

- Extraction: Extract cfDNA from 1-5 mL plasma according to manufacturer's protocol.

- Elution: Elute in 20-50 μL low-EDTA TE buffer or nuclease-free water.

- Quantification: Measure DNA concentration using fluorometric methods.

- Quality Control: Assess fragment size distribution using microcapillary electrophoresis.

Expected Outcomes:

- Yield: 1-50 ng total cfDNA depending on tumor burden

- Fragment size: predominant peak at ~167 bp with 10-bp periodicity

- DNA Integrity Number (DIN) >7 for high-quality samples

Library Preparation for NGS

Materials:

- Library preparation kit (e.g., Illumina TruSight Oncology ctDNA v2)

- Dual-indexed adapters

- Solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads

- Thermal cycler with precise temperature control

Procedure:

- End Repair and A-Tailing: Convert fragment ends to blunt, 5'-phosphorylated ends with 3'-dA overhangs.

- Adapter Ligation: Add dual-indexed adapters with T4 DNA ligase.

- Size Selection: Perform double-sided SPRI bead cleanup (0.5X-0.8X ratios) to enrich for 150-250 bp fragments.

- Library Amplification: Amplify with 8-12 PCR cycles using polymerase with proofreading activity.

- Final Purification: Clean up with 1X SPRI beads and elute in 20-25 μL buffer.

Quality Control Checkpoints:

- Quantify library concentration by qPCR (library quantification kit)

- Confirm library size distribution by fragment analyzer

- Assess adapter dimer formation (<5% of total signal)

Bisulfite Conversion for Methylation Analysis

Materials:

- Bisulfite conversion kit (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation Kit)

- Thermal cycler with heated lid

- Desalting columns or magnetic beads

Procedure:

- Denaturation: Incocate DNA in conversion reagent at 95°C for 30-60 seconds.

- Conversion: Incubate at 50-64°C for 45-90 minutes (time-temperature varies by kit).

- Desalting: Bind converted DNA to silica membrane or magnetic beads.

- Desulfonation: Treat with alkaline desulfonation solution (10-20 minutes).

- Wash and Elute: Wash thoroughly and elute in low-EDTA TE buffer.

Critical Considerations:

- Account for DNA degradation during conversion (30-50% loss expected)

- Include unmethylated and methylated control DNA in each batch

- Process samples within same experiment to minimize batch effects

Target Enrichment and Sequencing

Materials:

- Hybridization capture reagents (e.g., IDT xGen Lockdown Probes)

- Sequence-specific or methyl-binding domain-based enrichment tools

- Thermomixer with accurate temperature control

- Next-generation sequencer (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq X Series)

Procedure:

- Hybridization: Denature libraries at 95°C, then incubate with biotinylated probes at 65°C for 16-24 hours.

- Capture: Bind probe-target hybrids to streptavidin magnetic beads.

- Washing: Perform stringent washes at increasing temperatures (65-72°C) to reduce off-target binding.

- Amplification: Amplify captured libraries with 10-14 PCR cycles.

- Pooling and Normalization: Pool libraries in equimolar ratios based on qPCR quantification.

- Sequencing: Sequence on appropriate platform to achieve >10,000X raw coverage for ctDNA detection.

Sequencing Parameters:

- Minimum coverage: 10,000X raw reads for 0.1% variant detection

- Read length: 2×100 bp or 2×150 bp for sufficient overlap

- Sample multiplexing: 16-96 samples per lane depending on required coverage

Protocol: Single-Cell CTC Analysis for Heterogeneity Studies

Principiple: Isolate and characterize circulating tumor cells at single-cell resolution to understand cellular heterogeneity and identify rare subpopulations with therapeutic relevance.

CTC Enrichment and Isolation

Materials:

- CTC enrichment platform (e.g., CellSearch, microfluidic devices)

- EpCAM or other surface antigen antibodies

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) instrumentation

- Single-cell dispensing system

Procedure:

- Blood Processing: Process 7.5-10 mL blood within 96 hours of collection.

- Immunomagnetic Enrichment: Incubate with antibody-conjugated magnetic beads targeting epithelial markers.

- Magnetic Separation: Place in magnetic field to retain CTCs while removing unbound cells.

- Immunofluorescence Staining: Stain with cytokeratin-FITC, CD45-APC, and DAPI.

- Identification and Sorting: Identify CTCs (CK+/CD45-/DAPI+) and sort single cells into 96- or 384-well plates.

Critical Considerations:

- Account for epithelial-mesenchymal transition (include mesenchymal markers)

- Process matched normal blood as negative control

- Minimize time between sorting and downstream processing

Whole Genome Amplification and Sequencing

Materials:

- Single-cell whole genome amplification kit (e.g., MALBAC, DOP-PCR)

- Multiple displacement amplification reagents

- Library preparation kit for low-input DNA

- Quality control reagents (Bioanalyzer, qPCR)

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Lyse single cells in alkaline buffer or with proteinase K.

- DNA Amplification: Perform whole genome amplification according to manufacturer's protocol.

- Quality Assessment: Check amplification success by qPCR of housekeeping genes.

- Library Preparation: Convert amplified DNA to sequencing libraries.

- Sequencing: Sequence at moderate coverage (0.1-0.5X) for copy number variation analysis.

Expected Outcomes:

- 50-80% single-cell amplification success rate

- Identification of subclonal copy number alterations

- Phylogenetic reconstruction of metastatic spread

Visualization Diagrams

Liquid Biopsy Workflow Diagram

Tumor Heterogeneity Capture Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Liquid Biopsy Research

| Category | Product Examples | Key Features | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | K₂EDTA tubes; Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT; PAXgene Blood cDNA Tubes | Preserves cfDNA profile; inhibits nucleases | Streck tubes allow 3-7 day shipping stability; K₂EDTA requires processing <4 hours [28] |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit; MagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit | Optimized for low-concentration samples; high reproducibility | Yields 1-50 ng cfDNA from 1-5 mL plasma; compatible with downstream NGS [29] |

| Library Preparation | Illumina TruSight Oncology ctDNA v2; Swift Accel-NGS Methyl-Seq | Low-input compatibility; unique molecular identifiers | TSO ctDNA v2 covers 600+ cancer genes; UMI error correction enables <0.1% VAF detection [29] |

| Bisulfite Conversion | EZ DNA Methylation Kit; Premium Bisulfite Kit | High conversion efficiency; minimal DNA degradation | 30-50% DNA loss expected; include methylation controls for QC [28] |

| Target Enrichment | IDT xGen Lockdown Probes; Twist Human Methylation Panels | Comprehensive coverage; uniform performance | Hybridization conditions critical for on-target rates; customize panels for specific research [29] |

| CTC Enrichment | CellSearch System; Parsortix Platform; CTC-iChip | FDA-cleared; marker-independent options | CellSearch uses EpCAM enrichment; suitable for epithelial cancers [25] |

| Single-Cell Analysis | 10X Genomics Chromium; SMART-Seq v4; MALBAC kits | Whole transcriptome; low-input sensitivity | Enables heterogeneity studies at single-cell resolution; identifies rare resistant subclones [29] |

Liquid biopsy is a minimally invasive technique that analyzes tumor-derived components from bodily fluids, offering a powerful alternative to traditional tissue biopsies. By capturing a comprehensive picture of tumor heterogeneity and enabling real-time monitoring, liquid biopsy is revolutionizing chemogenomics—the study of how genomic features influence response to pharmacological compounds [23]. The key biomarkers analyzed in liquid biopsies include:

- Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA): Fragments of DNA released into the bloodstream by tumor cells through mechanisms such as apoptosis and necrosis [30].

- Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs): Intact cancer cells shed from primary and metastatic tumors [23].

- Tumor Extracellular Vesicles (EVs): Membrane-bound particles carrying nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids that facilitate cell-cell communication [23].

The integration of these biomarkers with next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies enables the discovery of chemogenomic biomarkers, which are critical for predicting drug efficacy, understanding resistance mechanisms, and guiding personalized therapy in oncology [23] [31].

Liquid Biopsy Biomarkers and NGS Workflow

Key Biomarker Types and Characteristics

Table 1: Liquid Biopsy Biomarkers in Chemogenomics

| Biomarker Type | Origin & Composition | Primary Clinical Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) | Short DNA fragments released via cell death processes (apoptosis, necrosis) [30]. | - Tumor genotyping & mutation profiling- Monitoring treatment response- Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) detection [23] [30]. | - Captures tumor heterogeneity- Highly specific for tumor-associated mutations- Allows for serial monitoring [23]. |

| Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) | Whole, viable tumor cells shed into circulation [23]. | - Prognostic assessment- Understanding metastasis mechanisms- Ex vivo drug sensitivity testing [23]. | Provides intact cellular material for functional analyses and culture [23]. |

| Tumor Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) | Membrane-bound vesicles carrying proteins, RNA, and DNA [23]. | - Identifying therapeutic targets- Monitoring drug resistance [23]. | - Protects molecular cargo from degradation- Reflects the state of parental tumor cells [23]. |

Comprehensive NGS Workflow for ctDNA Analysis

The transformation of a blood sample into actionable chemogenomic data involves a multi-stage NGS workflow. Key stages include sample collection, library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis, each requiring rigorous optimization to ensure data accuracy and reliability [31] [32].

Diagram 1: Core NGS workflow for liquid biopsy analysis, covering sample collection to data interpretation.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Plasma ctDNA Extraction and NGS Library Construction

Objective: To isolate high-quality cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from patient blood plasma and prepare sequencing libraries for the detection of somatic variants and chemogenomic biomarkers.

Materials:

- Blood Collection Tubes: Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT or K2EDTA tubes [32].

- Extraction Kit: QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit or similar [32].

- Library Prep Kit: xGen cfDNA & FFPE DNA Library Preparation Kit or similar [32].

- Quantification Tools: Qubit fluorometer and Agilent Bioanalyzer/TapeStation [32].

- Sequencing Platform: Illumina NovaSeq or similar [31].

Procedure:

- Sample Collection and Processing:

- Collect venous blood into preservative tubes. Invert gently 8-10 times.

- Centrifuge at 1,600-2,000 x g for 10-20 minutes at 4°C within 4 hours of collection to separate plasma.

- Carefully transfer the supernatant (plasma) to a fresh tube without disturbing the buffy coat.

- Perform a second, high-speed centrifugation at 16,000 x g for 10 minutes to remove residual cells and debris. Transfer the clarified plasma to a new tube [32].

cfDNA Extraction:

- Follow the manufacturer's protocol for the chosen circulating nucleic acid extraction kit.

- Elute the purified cfDNA in a low-EDTA TE buffer or nuclease-free water. A typical elution volume is 20-50 µL [32].

Quality Control of Extracted cfDNA:

- Quantify the cfDNA using a fluorescence-based method (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay).

- Assess the fragment size distribution using a high-sensitivity instrument (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100). The expected peak should be ~167 bp, characteristic of mononucleosomal DNA [32].

NGS Library Preparation:

- End Repair & A-Tailing: Convert the fragmented DNA ends to blunt, 5'-phosphorylated ends, followed by the addition of a single 'A' nucleotide to the 3' ends.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate double-stranded DNA adapters with a 3' 'T' overhang to the cfDNA fragments. Include unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to mitigate PCR amplification bias and enable error correction.

- Library Amplification: Perform limited-cycle PCR (e.g., 8-12 cycles) to enrich for adapter-ligated fragments and add full-length sequencing primers.

- Library Clean-up and Size Selection: Purify the amplified library using solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads to remove short fragments and adapter dimers [31] [32].

Final Library QC and Sequencing:

- Quantify the final library concentration by qPCR for accurate molarity.

- Confirm library size and quality (typically ~300-400 bp) using the Bioanalyzer.

- Pool libraries as needed and sequence on the appropriate NGS platform (e.g., Illumina) to a sufficient depth (e.g., >10,000x coverage for low-frequency variants) [31] [32].

Protocol: Targeted Sequencing for Chemogenomic Biomarker Discovery

Objective: To perform deep, targeted sequencing of genes known to harbor alterations that influence drug response, using ctDNA-derived libraries.

Materials:

- Hybridization Capture Kit: xGen Hybridization and Capture Kit or similar.

- Targeted Panels: Commercially available (e.g., Illumina TSO 500 ctDNA) or custom-designed panels covering key cancer genes (e.g., EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, ALK).

- Sequencing Platform: Illumina series [31].

Procedure:

- Library Enrichment:

- Pool up to 500 ng of pre-made cfDNA libraries from multiple samples.

- Denature the library pool and hybridize with biotinylated probes complementary to the targeted genomic regions for 4-16 hours.

- Capture the probe-bound fragments using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads.

- Wash the beads stringently to remove non-specifically bound DNA.

Post-Capture Amplification and QC:

- Perform a second, limited-cycle PCR to amplify the captured library.

- Purify the final enriched library with SPRI beads.

- Validate enrichment success and quantify the library as described in Section 3.1.

Sequencing and Data Analysis:

Data Analysis and Bioinformatics Pipeline

The computational analysis of NGS data is critical for translating raw sequencing reads into validated chemogenomic insights. The pipeline involves sequential steps of data processing, variant identification, and functional annotation [31] [33].

Diagram 2: Bioinformatics pipeline for identifying and annotating chemogenomic variants from NGS data.

Key Computational Tools for NGS Analysis

Table 2: Essential Bioinformatics Tools for ctDNA NGS Analysis

| Analysis Step | Software/Tool | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastQC, QualiMap [33] | Assesses sequencing read quality and identifies potential biases. |

| Read Trimming | Trimmomatic, Fastp [33] | Removes low-quality bases and adapter sequences. |

| Sequence Alignment | BWA-MEM, HISAT2, STAR [33] | Maps sequencing reads to a reference genome. |

| Variant Calling | GATK, MuTect2, FreeBayes [33] | Identifies single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (Indels). |

| Variant Annotation | ANNOVAR, Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) [33] | Predicts functional impact of variants (e.g., missense, frameshift) and provides population frequency data. |

| Pathway Analysis | DAVID, Enrichr, GSEA [33] | Identifies overrepresented biological pathways and processes among a set of genes. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of liquid biopsy-based chemogenomics requires a suite of reliable reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example Products/Brands |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free DNA Blood Collection Tubes | Preserves blood samples to prevent genomic DNA contamination and cfDNA degradation during transport and storage [32]. | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT tubes. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate and purify high-integrity cfDNA/ctDNA from plasma samples with high efficiency and low contamination [32]. | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit. |

| NGS Library Preparation Kits | Convert fragmented cfDNA into sequencing-ready libraries via end-repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification [32]. | xGen cfDNA & FFPE DNA Library Prep Kit. |

| Targeted Hybridization Capture Panels | Biotinylated probes designed to enrich sequencing libraries for specific genes of interest, allowing for deep sequencing of chemogenomic targets [31]. | Illumina TSO 500 ctDNA, custom panels from IDT. |

| NGS Quantification Kits & Instruments | Accurately measure library concentration and quality prior to sequencing to ensure optimal cluster density and data output [32]. | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay, Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit. |

Integrative Chemogenomic Analysis and Pathway Mapping

The final stage involves integrating genomic variant data with drug response knowledge to generate testable hypotheses. This is the core of chemogenomics, where a somatic mutation identified in a liquid biopsy is linked to a potential therapeutic strategy [34] [35].

Diagram 3: The chemogenomic hypothesis generation workflow, linking a detected variant to a potential therapy.

From Biomarker to Therapy: A Clinical Example

The utility of this integrated approach is exemplified by targeting the EGFR L858R mutation in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC):

- Biomarker Discovery: Deep sequencing of ctDNA identifies an EGFR L858R activating mutation.

- Knowledge Base Integration: Databases like the FDA's Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers or the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines list this mutation as a predictive biomarker for response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [34].

- Therapeutic Decision: The patient is treated with a third-generation EGFR TKI (e.g., Osimertinib), which is specifically designed to target this mutation and overcome resistance [34].

- Monitoring: Serial liquid biopsies are used to monitor ctDNA levels, with a decrease indicating treatment response. The emergence of new mutations (e.g., EGFR C797S) in subsequent liquid biopsies can signal the development of resistance, prompting another cycle of chemogenomic analysis and treatment adjustment [23] [30].

This closed-loop workflow demonstrates how liquid biopsy and NGS workflows form a dynamic platform for precision oncology, enabling continuous therapeutic optimization based on the evolving genomic landscape of a patient's cancer.

NGS Workflow Architectures: From Library Prep to Multi-Omic Data Generation

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomic analysis, offering powerful tools for investigating chemogenomic biomarkers through cell-free DNA (cfDNA) workflows. The analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), the tumor-derived fraction of cfDNA, provides a noninvasive method for assessing the molecular landscape of cancer, enabling real-time monitoring of treatment response and identification of resistance mechanisms [36] [37]. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate NGS approach—targeted panels, whole-exome sequencing (WES), or whole-genome sequencing (WGS)—represents a critical decision point that significantly impacts project scope, cost, data volume, and biological insights. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suited to different research scenarios within precision oncology and biomarker discovery [38] [39].

Targeted panels focus on sequencing a predefined set of genes known to be associated with specific cancer types or therapeutic responses, providing deep coverage of selected genomic regions [39] [40]. Whole-exome sequencing captures the protein-coding regions of the genome (approximately 2%), where most known disease-causing variants reside [41]. Whole-genome sequencing offers the most comprehensive approach by analyzing the entire genome, including both coding and non-coding regions [42]. The choice between these methodologies must consider multiple factors, including the specific research questions, sample type and quality, required detection sensitivity, bioinformatic capabilities, and budget constraints, particularly when working with the low ctDNA concentrations typical of liquid biopsy samples [36].

Technical Comparison of NGS Methodologies

Core Characteristics and Applications

The three primary NGS approaches differ fundamentally in the genomic regions they interrogate, the data they generate, and their clinical applications, particularly in the context of cfDNA analysis for chemogenomic biomarker research.

Targeted gene panels utilize hybridization-capture or amplicon-based methods to enrich specific genomic regions of interest prior to sequencing [40]. This focused approach enables extremely high sequencing depth (often >500×), which is crucial for detecting low-frequency variants in ctDNA, where tumor-derived DNA can represent a very small fraction of the total cfDNA [36] [39]. Panels are particularly valuable when the patient's phenotype points to a well-characterized group of conditions with known genetic heterogeneity, such as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) where biomarkers like EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and BRAF offer targets for therapeutic intervention [36] [39]. The limited scope reduces data analysis burden and minimizes incidental findings while providing sufficient information for treatment decisions in many clinical scenarios [40].

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) focuses on the exome, which constitutes approximately 1-2% of the human genome (about 30 million base pairs) but harbors an estimated 85% of known disease-causing variants [38] [41]. By sequencing all protein-coding regions, WES provides a balance between comprehensive genomic coverage and practical data management, making it particularly valuable for discovery-oriented research where the genetic basis of disease or treatment response is not fully characterized [38]. However, even the best target enrichment workflows are prone to some degree of target dropout and coverage bias, especially in GC- or AT-rich regions [42]. For cfDNA applications, WES typically achieves moderate coverage (80-150×), which may limit sensitivity for detecting very low-frequency ctDNA variants compared to targeted approaches [39].

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) provides the most comprehensive genomic analysis by sequencing the entire genome (approximately 3 billion base pairs), including both coding and noncoding regions [41] [42]. This unbiased approach facilitates detection of diverse variant types—including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), structural variants (SVs), and regulatory element alterations—without prior knowledge of their location [39]. While WGS offers unparalleled opportunities for novel biomarker discovery, it generates substantial data volumes (typically >90 GB per sample) and requires significant computational resources for processing and interpretation [41] [39]. The lower sequencing depth (typically 30-50×) at comparable cost to WES may limit its sensitivity for detecting rare variants in heterogeneous cfDNA samples [39].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Targeted Panels, WES, and WGS for cfDNA Research

| Feature | Targeted Panels | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analyzed Region | 50-500 selected genes [39] | All coding exons (~1-2% of genome) [41] [39] | Entire genome (coding + non-coding) [41] [39] |

| Region Size | Tens to thousands of genes [41] | >30 million base pairs [41] | ~3 billion base pairs [41] |

| Average Coverage | 500-1000× [39] | 80-150× [39] | 30-50× [39] |

| Data Volume per Sample | Low (varies with panel size) [39] | 5-10 GB [41] | >90 GB [41] |

| Detection Sensitivity for Low-Frequency Variants | High (ideal for VAF <10%) [39] | Moderate [39] | Lower unless sequenced at high depth [39] |

| Primary Clinical/Research Applications | Conditions with clear phenotype and known genes [39]; Therapy selection [36] | Rare diseases, complex phenotypes [39]; Unexplained hereditary disorders [38] | Unresolved cases, novel biomarker discovery [39] |

| Variant Types Detected | SNPs, InDels, CNV, Fusion [41] | SNPs, InDels, CNV, Fusion [41] | SNPs, InDels, CNV, Fusion, SV [41] |

| Turnaround Time | Fast (e.g., 4 days for validated oncopanel) [40] | Moderate [39] | Slow [39] |

| Cost | Low [39] | Moderate [39] | High [39] |

| Risk of Incidental Findings | Low [39] | Moderate [39] | High [39] |

Advantages and Limitations in cfDNA Research

Each NGS approach presents distinct advantages and limitations when applied to cfDNA analysis for chemogenomic biomarker research. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for selecting the appropriate methodology.

Targeted panels offer several advantages for ctDNA analysis: (1) High sensitivity due to deep sequencing coverage, enabling detection of rare variants with allele frequencies as low as 0.1-0.25% with optimized methods [36]; (2) Cost-effectiveness through focused sequencing resources [39]; (3) Streamlined data analysis with reduced interpretation burden [39]; and (4) Rapid turnaround times, with some validated oncopanels achieving results within 4 days [40]. However, targeted panels have significant limitations: (1) Limited discovery potential as they only detect variants in predefined genes [38]; (2) Inability to detect novel biomarkers outside the panel content [43]; and (3) Rapid obsolescence as new disease-gene associations are identified, with one study noting that 23% of positive WES findings were in genes discovered within the preceding two years [38].

Whole-exome sequencing provides a balanced approach with these advantages: (1) Comprehensive coverage of protein-coding regions without being restricted to known genes [38]; (2) Cost-effective alternative to WGS for focusing on coding regions [42]; and (3) Excellent for hypothesis-generating research where the genetic basis is unclear [39]. The limitations of WES include: (1) Inability to detect functional variants in noncoding regions [38]; (2) Variable coverage uniformity across the exome, potentially missing some variants [42]; (3) Moderate sensitivity for low-frequency variants compared to targeted panels [39]; and (4) Higher interpretation burden than targeted panels due to more variants [39].

Whole-genome sequencing offers the most comprehensive approach with these advantages: (1) Complete genomic characterization including coding, noncoding, and regulatory regions [42]; (2) Superior detection of structural variants, copy number variations, and rearrangements [39]; (3) Hypothesis-free approach enabling novel biomarker discovery [39]; and (4) Future-proof dataset that can be reanalyzed as new genomic insights emerge. The limitations are substantial: (1) Highest cost per sample [39]; (2) Massive data storage and computational requirements [39]; (3) Challenging interpretation of noncoding variants with limited functional annotation [38]; and (4) Lower sensitivity for rare variants at standard coverage depths [39].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for NGS Approaches in Detecting Key Variant Types

| Variant Type | Targeted Panels | WES | WGS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) | Excellent (high sensitivity at low VAF) [40] | Good [39] | Good [39] |

| Insertions/Deletions (Indels) | Excellent (with optimized panels) [40] | Good [39] | Good [39] |

| Copy Number Variations (CNVs) | Limited [39] | Partial (depends on pipeline) [39] | Excellent [39] |

| Gene Fusions/Rearrangements | Good (for targeted genes) [41] | Moderate [41] | Excellent [41] |

| Structural Variants (SVs) | Limited [39] | Partial [39] | Excellent [39] |

| Noncoding Variants | None (unless specifically targeted) | None | Good [42] |

NGS Workflow for cfDNA Analysis

Standardized Protocol for cfDNA NGS Analysis

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive workflow for NGS analysis of cfDNA samples, with specific considerations for each sequencing approach. This methodology is adapted from validated procedures described in the literature and has been optimized for ctDNA detection sensitivity [36] [20] [40].

Sample Collection and Processing

- Collect peripheral blood (typically 10-20 mL) in cell-stabilizing tubes (e.g., Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT or PAXgene Blood cDNA tubes) to prevent genomic DNA contamination from white blood cell lysis.

- Process samples within 4-6 hours of collection by double centrifugation: first at 1600× g for 10 minutes at 4°C, then transfer plasma to a fresh tube and centrifuge at 16,000× g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove remaining cellular debris.

- Store plasma at -80°C if not proceeding immediately to DNA extraction.

cfDNA Extraction

- Extract cfDNA from 1-5 mL of plasma using specialized cfDNA extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit, Maxwell RSC ccfDNA Plasma Kit, or similar).

- Quantify cfDNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) rather than UV spectrophotometry, as fluorometry provides more accurate quantification of low-concentration samples.

- Assess cfDNA quality using microfluidic electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with High Sensitivity DNA chips or TapeStation), expecting a characteristic peak at ~160-170 bp representing mononucleosomal DNA.

- A minimum of 10-50 ng cfDNA is typically required for library preparation, though some optimized workflows can work with lower inputs [40].

Library Preparation

- Convert cfDNA into sequencing libraries using kits specifically designed for low-input and fragmented DNA (e.g., Illumina TruSeq Nano, KAPA HyperPrep, or NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep).

- For targeted panels: Use hybridization capture with biotinylated oligonucleotide probes (e.g., Illumina TruSight Oncology 500, TSO500 ctDNA) or amplicon-based approaches (e.g., AmpliSeq HD) [36] [37] [40].

- For WES: Employ exome capture using platforms such as Agilent SureSelect, Illumina Nextera Rapid Capture, or IDT xGen Exome Research Panel.

- For WGS: Use non-enriched library preparation methods with appropriate fragmentation.

- Incorporate unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to reduce sequencing artifacts and enable accurate detection of low-frequency variants by accounting for PCR amplification biases and sequencing errors [37].

Target Enrichment (for Panels and WES)

- For hybridization-based approaches: Incubate libraries with biotinylated probes targeting regions of interest, then capture with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads.

- Wash stringently to remove non-specifically bound DNA and elute the enriched targets.

- Amplify the enriched libraries with limited-cycle PCR (typically 8-12 cycles) to generate sufficient material for sequencing.

Sequencing

- Quantify final libraries using qPCR-based methods (e.g., KAPA Library Quantification Kit) for accurate quantification, as this correlates best with cluster density on the flow cell.

- Dilute libraries to appropriate concentrations (typically 1-2 nM) and denature with NaOH immediately before loading.

- Sequence on appropriate NGS platforms (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq 6000, MiSeq, or MGI DNBSEQ-G50RS) with paired-end reads [37] [40].

- For targeted panels: Sequence to high depth (typically >500× mean coverage) to enable detection of low-frequency variants (≤0.5% VAF).

- For WES: Sequence to 80-150× mean coverage.

- For WGS: Sequence to 30-50× mean coverage.

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Demultiplex sequencing data and convert BCL files to FASTQ format.

- Perform quality control assessment using tools such as FastQC.

- Align reads to the reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using optimized aligners (BWA-MEM, Bowtie 2).

- For UMI-containing libraries: Process reads to group duplicates by their molecular barcodes, correcting for sequencing errors.

- Call variants using specialized tools:

- For panels: Use vendor-specific software (e.g., Sophia DDM) or custom pipelines with MuTect2, VarScan2 for somatic variants [40].

- For WES/WGS: Use GATK best practices for variant calling, including HaplotypeCaller for germline variants and Mutect2 for somatic variants.

- Annotate variants using ANNOVAR, SnpEff, or VEP with appropriate databases (ClinVar, COSMIC, gnomAD, dbSNP).

- Filter variants based on quality metrics, population frequency, and predicted functional impact.

- For cfDNA samples: Apply additional filters for clonal hematopoiesis variants and sequencing artifacts.

Analytical Validation

- Establish limit of detection (LOD) using serially diluted reference standards with known variant allele frequencies (typically 2-5% for WES/WGS, 0.1-1% for targeted panels) [40].

- Assess reproducibility through replicate experiments (inter-run and intra-run precision).

- Validate against orthogonal methods (e.g., digital PCR) for key variants.

Quality Control Metrics

Robust quality control is essential throughout the NGS workflow to ensure reliable results, particularly when working with low-input cfDNA samples.

Pre-sequencing QC Metrics

- cfDNA Quantity: Minimum 10-50 ng for library preparation, though some optimized panels can work with lower inputs [40].

- cfDNA Quality: Fragment size distribution should show peak at ~160-170 bp. Ratio of long (>1000 bp) to short (~160 bp) fragments should be <10% to minimize contamination from cellular genomic DNA.

- Library Concentration: Typically 1-20 nM, quantified by qPCR for accurate measurement.

- Library Size Distribution: Expected size of 200-500 bp including adapters.

Sequencing QC Metrics

- Clustering Density: Optimal range depends on platform (e.g., 170-220 K/mm² for Illumina NovaSeq).

- Q-score: >80% bases with Q30 (0.1% error rate) or higher.

- % Bases ≥ Q30: Should exceed 75% for reliable variant calling.

Post-sequencing QC Metrics

- On-target Rate: Percentage of reads mapping to target regions (>80% for hybrid capture panels, >60% for amplicon-based panels).

- Uniformity of Coverage: >80% of targets covered at ≥0.2× mean coverage.

- Mean Coverage: Varies by application (>500× for targeted panels, 80-150× for WES, 30-50× for WGS) [39].

- Duplicate Rate: <20% for WGS, <50% for hybrid capture, higher rates expected for amplicon-based approaches.

- Insert Size: Should match expected cfDNA fragment distribution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Successful implementation of cfDNA NGS workflows requires careful selection of reagents, technologies, and computational tools. The following table summarizes key solutions used in the field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for cfDNA NGS Workflows

| Category | Product/Technology | Key Features | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCTPAXgene Blood cDNA tubes | Preserves blood cells, prevents gDNA releaseStabilizes nucleic acids | Enables extended sample transportMaintains cfDNA profile for days |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid KitMaxwell RSC ccfDNA Plasma KitMagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit | Optimized for low-abundance cfDNAAutomated processingHigh recovery from small volumes | Critical for low-VAF variant detectionReduces manual processing timeSuitable for high-throughput labs |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina TruSeq NanoKAPA HyperPrep KitNEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep | Low-input DNA compatibilityUMI incorporationReduced GC bias | Essential for limited cfDNA samplesEnables error correctionImproves coverage uniformity |

| Target Enrichment | Illumina TruSight Oncology 500 ctDNAKAPA HyperCaptureIDT xGen Lockdown Panels | Pan-cancer contentHybridization-based captureCustomizable target content | Detects SNVs, indels, CNVs, fusionsHigh specificity and sensitivityTailored to specific research needs |

| UMI Technologies | TruSight Oncology UMI ReagentsQIAseq UMI technologies | Unique molecular identifiersError correctionBackground noise reduction | Enables detection of variants <0.5% VAFCritical for low-frequency variantsReduces false positives |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq 6000MGI DNBSEQ-G50RSIllumina MiSeq | High-throughputCompetitive pricingRapid turnaround | Scalable for large studiesCost-effective for targeted panelsIdeal for validation studies |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Sophia DDMGATK Mutect2BWA-MEMANNOVAR | Machine learning integrationSomatic variant callingRead alignmentVariant annotation | Automated variant classificationGold standard for NGS dataFast and accurate alignmentFunctional interpretation |

Selection Framework and Decision Pathways

Choosing the optimal NGS approach requires systematic consideration of multiple scientific and practical factors. The following decision pathway provides a structured framework for selection based on key project parameters.

Application-Specific Recommendations

Different research scenarios warrant specific NGS approaches based on the biological questions, sample characteristics, and analytical requirements.

Therapy Selection and Resistance Monitoring For clinical applications focused on identifying actionable mutations for therapy selection or detecting resistance mechanisms, targeted panels are typically preferred [36]. Their high sensitivity enables detection of emerging resistance mutations at low variant allele frequencies, which is crucial for timely treatment modifications. Studies have demonstrated that ctDNA NGS testing can better recapitulate NSCLC heterogeneity compared with tissue testing and allows monitoring of therapy response and early identification of resistance mechanisms [36]. The focused nature of panels also facilitates rapid turnaround times (as short as 4 days with optimized workflows), which is often critical in clinical decision-making [40].