Validating Chemogenomic Libraries for Phenotypic Screening: Strategies for Unlocking Novel Drug Targets

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of chemogenomic libraries for phenotypic screening.

Validating Chemogenomic Libraries for Phenotypic Screening: Strategies for Unlocking Novel Drug Targets

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of chemogenomic libraries for phenotypic screening. It covers the foundational principles of chemogenomics and its critical role in phenotypic drug discovery, explores methodological advances in library design and application, details strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing screening campaigns, and establishes frameworks for the rigorous validation and comparative analysis of screening hits. The content synthesizes current best practices to enhance the success rate of identifying novel therapeutic targets and first-in-class medicines.

Chemogenomics and Phenotypic Screening: Foundations for Target-Agnostic Drug Discovery

Chemogenomic libraries represent structured collections of small molecules with annotated biological activities, designed to systematically probe protein function and cellular networks. These libraries have emerged as critical tools in phenotypic drug discovery, bridging the gap between traditional target-based and phenotypic screening approaches. The fundamental premise of chemogenomic libraries lies in their ability to provide starting points for understanding complex biological systems while offering potential pathways for target deconvolution—the process of identifying molecular targets responsible for observed phenotypic effects [1] [2]. Unlike diverse chemical libraries used in high-throughput screening, chemogenomic libraries are typically enriched with compounds having known or predicted mechanism of action, offering researchers a more targeted approach to interrogating biological systems.

The contemporary value of these libraries extends beyond mere compound collections to integrated knowledge systems that connect chemical structures to biological targets, pathways, and disease phenotypes [3]. This integration has become increasingly important as drug discovery shifts from a reductionist "one target—one drug" paradigm to a more nuanced systems pharmacology perspective that acknowledges most effective drugs modulate multiple targets [3]. The validation and application of chemogenomic libraries in phenotypic screening represents a critical frontier in chemical biology, enabling more efficient translation of cellular observations into therapeutic hypotheses.

Quantitative Comparison of Major Chemogenomic Libraries

The Polypharmacology Index (PPindex): A Key Metric for Library Characterization

A fundamental challenge in utilizing chemogenomic libraries is understanding their inherent polypharmacology—the degree to which compounds within a library interact with multiple molecular targets. To address this, researchers have developed a quantitative metric known as the Polypharmacology Index (PPindex), derived by plotting known targets of library compounds as a histogram fitted to a Boltzmann distribution [1]. The linearized slope of this distribution serves as an indicator of overall library polypharmacology, with larger absolute values (steeper slopes) indicating more target-specific libraries and smaller values (shallower slopes) indicating more polypharmacologic libraries [1].

Table 1: PPindex Values for Major Chemogenomic Libraries

| Library Name | PPindex (All Compounds) | PPindex (Without 0-target compounds) | PPindex (Without 0 & 1-target compounds) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSP-MoA | 0.9751 | 0.3458 | 0.3154 |

| DrugBank | 0.9594 | 0.7669 | 0.4721 |

| MIPE 4.0 | 0.7102 | 0.4508 | 0.3847 |

| DrugBank Approved | 0.6807 | 0.3492 | 0.3079 |

| Microsource Spectrum | 0.4325 | 0.3512 | 0.2586 |

This quantitative analysis reveals substantial differences in polypharmacology characteristics across commonly used libraries. The LSP-MoA (Laboratory of Systems Pharmacology-Method of Action) and DrugBank libraries demonstrate the highest target specificity when considering all compounds, while the Microsource Spectrum collection shows significantly greater polypharmacology [1]. However, the interpretation of these values requires nuance, as data sparsity—particularly the large number of compounds with only one annotated target due to limited screening—can significantly influence the metrics [1].

Comparative Analysis of Library Composition and Coverage

Beyond polypharmacology metrics, understanding the composition and target coverage of chemogenomic libraries is essential for selecting appropriate tools for phenotypic screening campaigns. Different libraries offer varying degrees of biological and chemical diversity, with implications for their utility in different research contexts.

Table 2: Composition and Characteristics of Major Chemogenomic Libraries

| Library Name | Approximate Size | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSP-MoA | Not specified | Optimally targets the liganded kinome; rational design | Kinase-focused phenotypic screening |

| MIPE 4.0 | 1,912 compounds | Small molecule probes with known mechanism of action | Target deconvolution in phenotypic screens |

| Microsource Spectrum | 1,761 compounds | Bioactive compounds for HTS or target-specific assays | General phenotypic screening |

| DrugBank | 9,700 compounds | Approved, biotech, and experimental drugs | Drug repurposing and safety assessment |

A critical limitation across all existing chemogenomic libraries is their incomplete coverage of the human genome. Even the most comprehensive libraries typically interrogate only 1,000-2,000 targets out of the 20,000+ genes in the human genome, representing less than 10% of the potential target space [2]. This coverage gap highlights a significant opportunity for library expansion and development, particularly for understudied target classes.

Experimental Approaches for Library Validation and Application

Methodologies for Assessing Library Polypharmacology

The quantitative assessment of library polypharmacology follows a rigorous methodology beginning with comprehensive target annotation. This process involves collecting in vitro binding data from sources like ChEMBL in the form of Kᵢ and IC₅₀ values, followed by filtering for redundancy [1]. Computational approaches then enable systematic analysis:

Structural Standardization and Similarity Assessment: Compound structures are standardized using canonical Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings that preserve stereochemistry information. Tanimoto similarity coefficients are calculated using tools like RDKit to generate molecular fingerprints from chemical structures [1].

Target Annotation and Histogram Generation: The number of recorded molecular targets for each compound is enumerated, with target status assigned to any drug-receptor interaction having a measured affinity better than the upper limit of the assay [1]. Histograms of targets per compound are generated and fitted to Boltzmann distributions.

PPindex Calculation: The histogram values are sorted in descending order and transformed into natural log values using curve-fitting software such as MATLAB's Curve Fitting Suite. The slope of the linearized distribution represents the PPindex, with all curves typically demonstrating R² values above 0.96, indicating excellent goodness of fit [1].

Phenotypic Validation Using High-Content Multiplex Assays

Beyond computational assessment, experimental validation of chemogenomic libraries employs sophisticated phenotypic screening approaches. High-content live-cell multiplex assays represent state-of-the-art methodologies for comprehensive compound annotation based on morphological profiling [4] [5].

Assay Design and Optimization: These assays typically utilize live-cell imaging with fluorescent dyes that do not interfere with cellular functions over extended time periods. Key dye concentrations are carefully optimized—for example, Hoechst33342 nuclear stain is used at 50 nM, well below the 1 μM threshold where toxicity concerns emerge [4]. Multiplexing approaches simultaneously monitor multiple cellular parameters including nuclear morphology, mitochondrial health, tubulin integrity, and membrane integrity.

Time-Dependent Cytotoxicity Profiling: Continuous monitoring over 48-72 hours enables distinction between primary and secondary target effects. This temporal resolution helps differentiate compounds with rapid cytotoxic mechanisms (e.g., staurosporine, berzosertib) from those with slower phenotypes (e.g., epigenetic inhibitors like JQ1 and ricolinostat) [4].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Analysis: Automated image analysis coupled with supervised machine learning algorithms classifies cells into distinct phenotypic categories including healthy, early/late apoptotic, necrotic, and lysed populations [4]. This multi-dimensional profiling generates comprehensive compound signatures that extend beyond simple viability metrics.

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The experimental workflows for chemogenomic library validation rely on specialized reagents and instrumentation that enable precise morphological profiling and data analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemogenomic Library Validation

| Reagent/Instrument | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hoechst33342 | 50 nM working concentration | Nuclear staining for morphology assessment and cell counting |

| Mitotracker Red/DeepRed | Optimized concentration based on cell type | Mitochondrial mass and health assessment |

| BioTracker 488 Green Microtubule Dye | Taxol-derived fluorescent conjugate | Microtubule cytoskeleton integrity assessment |

| CQ1 High-Content Imaging System | Yokogawa imaging platform | Automated live-cell imaging over extended time courses |

| CellPathfinder Software | High-content analysis package | Image analysis and machine learning classification |

| U2OS, HEK293T, MRC9 Cell Lines | Human osteosarcoma, kidney, fibroblast cells | Assay development and compound profiling across multiple cell types |

Strategic Implementation in Phenotypic Screening

Library Selection Guidelines for Different Research Objectives

The optimal choice of chemogenomic library depends heavily on the specific research goals and screening context. Based on the comparative analysis of library characteristics, several strategic guidelines emerge:

Target Deconvolution Applications: For phenotypic screens where target identification is the primary objective, libraries with lower polypharmacology (higher PPindex values) such as LSP-MoA and DrugBank are preferable [1]. These libraries increase the probability that observed phenotypes can be confidently linked to specific molecular targets.

Pathway and Network Analysis: When investigating complex biological pathways or seeking compounds with synergistic polypharmacology, libraries with moderate polypharmacology such as MIPE 4.0 may offer advantages by engaging multiple nodes within biological networks [6].

Disease-Specific Library Design: Emerging approaches combine tumor genomic profiles with protein-protein interaction networks to create disease-targeted chemogenomic libraries. For example, screening of glioblastoma-specific targets identified 117 proteins with druggable binding sites, enabling creation of focused libraries for selective polypharmacology [6].

Integrated Knowledge Systems for Enhanced Library Utility

The most advanced implementations of chemogenomic libraries extend beyond simple compound collections to integrated knowledge networks. These systems connect chemical structures to biological targets, pathways, and disease phenotypes using graph database technologies such as Neo4j [3]. Such integration enables:

Morphological Profiling Connectivity: Linking compound-induced morphological changes from Cell Painting assays to target annotations helps identify characteristic phenotypic fingerprints for specific target classes [3].

Scaffold-Based Diversity Analysis: Systematic decomposition of compounds into hierarchical scaffolds using tools like ScaffoldHunter enables assessment of structural diversity and identification of underrepresented chemotypes in existing libraries [3].

Target-Disease Association Mapping: Integration with Disease Ontology (DO) and KEGG pathway databases facilitates prediction of novel therapeutic applications for library compounds through enrichment analysis [3].

Chemogenomic libraries represent evolving resources that balance the competing demands of target specificity and polypharmacology in phenotypic screening. Quantitative assessment using metrics like the PPindex enables rational library selection based on specific research objectives, with different libraries offering distinct advantages for applications ranging from target deconvolution to selective polypharmacology. The ongoing development of integrated knowledge systems that connect chemical structures to biological effects and disease phenotypes promises to enhance the utility of these libraries, while advanced validation methodologies using high-content multiplex assays provide essential quality control. As these libraries continue to expand in both chemical and target coverage, they will play an increasingly vital role in bridging the gap between phenotypic observations and therapeutic hypotheses in drug discovery.

The Resurgence of Phenotypic Drug Discovery and Its Synergy with Chemogenomics

For decades, target-based drug discovery (TDD) dominated the pharmaceutical landscape, guided by a reductionist vision of "one target—one drug." However, biology does not follow linear rules, and the surprising observation that a majority of first-in-class drugs between 1999 and 2008 were discovered empirically without a target hypothesis triggered a major resurgence in phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) [7]. Modern PDD represents an evolved strategy—systematically pursuing drug discovery based on therapeutic effects in realistic disease models while leveraging advanced tools and technologies [7]. This approach has reemerged not as a transient trend but as a mature discovery modality in both academia and the pharmaceutical industry, fueled by notable successes in treating cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy, and various cancers [7].

Concurrently, chemogenomics has emerged as a complementary discipline that systematically explores the interaction between chemical space and biological targets. Chemogenomic libraries—collections of selective small molecules modulating protein targets across the human proteome—provide the critical link between observed phenotypes and their underlying molecular mechanisms [8]. The synergy between phenotypic screening and chemogenomics creates a powerful framework for identifying novel therapeutic mechanisms while overcoming the historical challenges of target deconvolution. This guide examines the quantitative performance of this integrated approach through experimental data, methodological protocols, and comparative analyses to inform strategic decision-making in drug development.

Performance Comparison: Phenotypic vs. Target-Based Discovery

Expansion of Druggable Target Space

Phenotypic screening has demonstrated a remarkable ability to identify first-in-class therapies with novel mechanisms of action (MoA) that would likely have been missed by target-based approaches. The following table summarizes key approved drugs discovered through phenotypic screening:

Table 1: Clinically Approved Drugs Discovered Through Phenotypic Screening

| Drug Name | Disease Indication | Novel Mechanism of Action | Discovery Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ivacaftor, Tezacaftor, Elexacaftor | Cystic Fibrosis | CFTR correctors (enhance folding/trafficking) & potentiators | Target-agnostic compound screens in cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants [7] |

| Risdiplam, Branaplam | Spinal Muscular Atrophy | SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing modifiers | Phenotypic screens identifying small molecules that modulate SMN2 splicing [7] |

| Lenalidomide, Pomalidomide | Multiple Myeloma | Cereblon E3 ligase modulators (targeted protein degradation) | Phenotypic optimization of thalidomide analogs [7] [9] |

| Daclatasvir | Hepatitis C | NS5A protein modulation (non-enzymatic target) | HCV replicon phenotypic screen [7] |

| Sep-363856 | Schizophrenia | Unknown novel target (non-D2 receptor) | Phenotypic screen in disease models [7] |

The distinct advantage of PDD is further evidenced by its ability to address previously undruggable target classes and mechanisms. Unlike TDD, which requires predefined molecular hypotheses, PDD has revealed unprecedented MoAs including pharmacological chaperones, splicing modifiers, and molecular glues for targeted protein degradation [7]. This expansion of druggable space is particularly valuable for complex diseases with polygenic etiology, where single-target approaches have shown limited success [7].

Quantitative Performance Metrics in Screening

The integration of chemogenomics with phenotypic screening creates a powerful synergy that enhances screening efficiency. The following table compares key performance metrics between different screening approaches:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Screening Approaches

| Screening Parameter | Traditional Phenotypic Screening | Chemogenomics-Enhanced Phenotypic Screening | Target-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Coverage | Unlimited (target-agnostic) | ~1,000-2,000 annotated targets [2] | Single predefined target |

| Hit Rate Efficiency | Low (0.001-0.1%) | 1.5-3.5% with AI-guided approaches [10] | Variable (0.001-1%) |

| Target Deconvolution Success | Challenging and time-consuming | Accelerated via annotated libraries [8] | Not applicable |

| Novel Mechanism Identification | High (numerous first-in-class drugs) [7] | Moderate to high (novel polypharmacology) [7] | Low (limited to known biology) |

| Chemical Library Size | Large (>100,000 compounds) | Focused (5,000-10,000 compounds) [8] [11] | Variable |

Recent advances in computational methods have significantly enhanced the efficiency of phenotypic screening. The DrugReflector framework, which uses active reinforcement learning to predict compounds that induce desired phenotypic changes, has demonstrated an order of magnitude improvement in hit rates compared to random library screening [10]. This approach leverages transcriptomic signatures from resources like the Connectivity Map to iteratively improve screening efficacy through closed-loop feedback [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Chemogenomic Library Development and Validation

The construction of high-quality chemogenomic libraries requires systematic approaches to ensure comprehensive target coverage while maintaining chemical diversity and optimal physicochemical properties. A representative protocol for library development includes:

Step 1: Target Space Definition

- Compile proteins implicated in disease pathogenesis from genomic, proteomic, and literature sources [11].

- Annotate protein families, biological pathways, and disease associations using resources like KEGG, Gene Ontology, and Disease Ontology [8].

- Establish selection criteria based on genetic validation, druggability assessments, and pathway relevance [11].

Step 2: Compound Selection and Annotation

- Extract bioactivity data from ChEMBL (version 22+), including Ki, IC50, and EC50 values [8].

- Apply filters for cellular activity, target selectivity, chemical diversity, and availability [11].

- Use scaffold analysis tools like ScaffoldHunter to ensure structural diversity and representativeness [8].

Step 3: Library Assembly and Profiling

- Curate final compound collection (typically 1,000-5,000 compounds) covering defined target space [8] [11].

- Generate morphological profiles using Cell Painting assay in disease-relevant cell lines [8].

- Implement quality control through replicate testing and control compounds [8].

Step 4: Data Integration and Network Construction

- Build network pharmacology database using graph databases (Neo4j) integrating drug-target-pathway-disease relationships [8].

- Incorporate morphological profiling data from high-content imaging (BBBC022 dataset) [8].

- Enable query and visualization capabilities for mechanism of action exploration [8].

This methodology was successfully applied in glioblastoma research, resulting in a minimal screening library of 1,211 compounds targeting 1,386 anticancer proteins. A physical library of 789 compounds covering 1,320 targets identified patient-specific vulnerabilities in glioma stem cells, demonstrating highly heterogeneous phenotypic responses across patients and subtypes [11].

Phenotypic Screening and Hit Triage Workflow

Successful phenotypic screening requires carefully designed experimental and computational workflows to ensure biological relevance and translatability:

Stage 1: Assay Development and Screening

- Select physiologically relevant cell systems (primary cells, iPSC-derived models, or engineered cell lines) [7] [2].

- Implement high-content readouts (Cell Painting, transcriptomics, functional metrics) capturing multidimensional phenotypes [12] [13].

- Perform quality control using Z'-factor assessment and control compounds [13].

Stage 2: Hit Triage and Validation

- Apply multiparametric analysis to distinguish true positives from artifacts [14].

- Use structure-activity relationships (SAR) to confirm pharmacologically relevant responses [14].

- Implement counter-screens against related phenotypes to assess specificity [14].

- Prioritize compounds using three knowledge domains: known mechanisms, disease biology, and safety [14].

Stage 3: Mechanism Deconvolution

- Employ chemogenomic library annotations for initial target hypothesis generation [8].

- Utilize functional genomics (CRISPR screens) to identify genetic vulnerabilities matching compound profiles [2].

- Apply proteomic approaches (thermal proteome profiling, affinity purification) for target identification [7].

- Validate mechanisms through genetic (siRNA, CRISPR) and pharmacological (selective inhibitors) approaches [7].

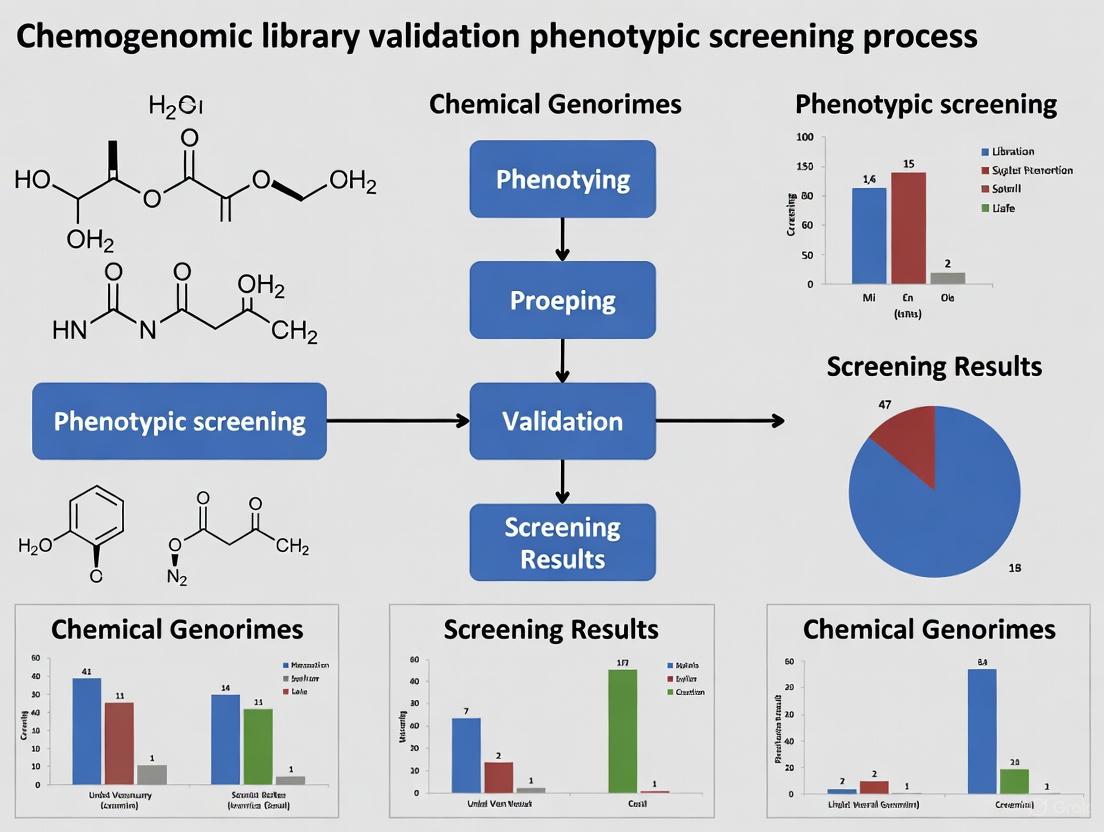

Diagram: Integrated Phenotypic Screening and Chemogenomics Workflow

Key Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Phenotypic screening has revealed several unprecedented therapeutic mechanisms that have expanded the conventional boundaries of druggable targets. Understanding these pathways is essential for designing effective screening strategies and interpreting results.

Targeted Protein Degradation via Molecular Glues

The discovery of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) like thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide represents a classic example of phenotypic screening revealing novel mechanisms. These compounds bind to cereblon (CRBN), a substrate receptor of the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, altering its substrate specificity [9]. This leads to ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of specific neosubstrates, particularly the lymphoid transcription factors IKZF1 (Ikaros) and IKZF3 (Aiolos) [9]. The degradation of these transcription factors is now recognized as the key mechanism underlying the anti-myeloma activity of these agents [9].

Diagram: Molecular Glue Mechanism of IMiDs

RNA Splicing Modulation

In spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), phenotypic screens identified small molecules that modulate SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing to increase levels of functional survival of motor neuron (SMN) protein [7]. Risdiplam and branaplam stabilize the interaction between the U1 snRNP complex and SMN2 exon 7, promoting inclusion of this critical exon and producing stable, functional SMN protein [7]. This mechanism represents a novel approach to treating genetic disorders by modulating RNA processing rather than targeting proteins.

Protein Folding and Trafficking Correction

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) correctors (elexacaftor, tezacaftor) and potentiators (ivacaftor) were discovered through phenotypic screening in cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants [7]. These compounds address different classes of CFTR mutations through complementary mechanisms: correctors improve CFTR folding and trafficking to the plasma membrane, while potentiators enhance channel gating properties at the membrane [7]. The triple combination therapy (elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor) represents a breakthrough that addresses the underlying defect in approximately 90% of CF patients [7].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Successful implementation of integrated phenotypic and chemogenomic screening requires specialized reagents and platforms. The following table details essential research tools and their applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Phenotypic-Chemogenomic Screening

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Key Features | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay | High-content morphological profiling | Multiplexed staining of 5-8 cellular components; ~1,700 morphological features [8] | Phenotypic profiling, mechanism of action studies, hit triage [8] |

| Chemogenomic Libraries | Targeted compound collections | 1,000-5,000 compounds with annotated targets; covering druggable genome [8] [11] | Phenotypic screening, target hypothesis generation, polypharmacology studies [8] |

| CRISPR Functional Genomics | Genome-wide genetic screening | Gene knockout/activation; arrayed or pooled formats [2] | Target identification, validation, synthetic lethality studies [2] |

| Graph Databases (Neo4j) | Network pharmacology integration | Integrates drug-target-pathway-disease relationships; enables complex queries [8] | Mechanism deconvolution, multi-omics data integration [8] |

| AI/ML Platforms (DrugReflector) | Predictive compound screening | Active reinforcement learning; uses transcriptomic signatures [10] | Virtual phenotypic screening, hit prioritization [10] |

| Connectivity Map (L1000) | Transcriptomic profiling | Gene expression signatures for ~1,000,000 compounds; reference database [10] | Mechanism prediction, compound similarity analysis [10] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The integration of phenotypic screening with chemogenomics represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, moving from reductionist single-target approaches to systems-level pharmacological interventions. This synergy addresses fundamental challenges in both approaches: it preserves the biological relevance and novelty capacity of phenotypic screening while accelerating the historically burdensome process of target deconvolution through annotated chemical libraries [8].

Future advancements in this field will likely focus on several key areas. First, the development of more sophisticated chemogenomic libraries with expanded target coverage beyond the current 1,000-2,000 targets will be essential [2]. Second, AI and machine learning frameworks like DrugReflector will continue to evolve, incorporating multi-omics data (proteomic, genomic, metabolomic) to enhance predictive accuracy for complex disease signatures [10]. Third, the integration of functional genomics with small molecule screening will provide complementary approaches for target identification and validation [2].

The application of these integrated approaches in precision oncology and personalized medicine shows particular promise. The demonstrated ability to identify patient-specific vulnerabilities in heterogeneous diseases like glioblastoma underscores the potential for matching chemogenomic annotations with individual patient profiles to guide therapeutic selection [11]. As these technologies mature and datasets expand, the synergy between phenotypic discovery and chemogenomics will likely become increasingly central to therapeutic development, particularly for complex diseases with limited treatment options.

The resurgence of phenotypic drug discovery, powerfully enhanced by chemogenomic approaches, represents a significant evolution in pharmaceutical research. This integrated framework combines the unbiased, biology-first advantage of phenotypic screening with the mechanistic insights provided by annotated chemical libraries. Experimental data demonstrates that this synergy enhances screening efficiency, enables novel target identification, and facilitates mechanism deconvolution. As technological advances in AI, multi-omics, and functional genomics continue to accelerate, this integrated approach promises to drive the next generation of first-in-class therapies, particularly for diseases with complex biology and unmet medical needs.

In the quest for first-in-class medicines, phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) has re-emerged as a powerful, unbiased strategy for identifying novel therapeutic mechanisms. Unlike target-based drug discovery (TDD), which focuses on modulating a predefined molecular target, PDD examines the effects of chemical or genetic perturbations on disease-relevant cellular or tissue phenotypes without prior assumptions about the target[sitation:1]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for addressing complex, polygenic diseases and has been responsible for a disproportionate share of innovative new medicines, largely because it expands the "druggable genome" to include unexpected biological processes and multi-component cellular machines[sitation:1]. This guide objectively compares the performance of phenotypic screening strategies, supported by experimental data, within the context of chemogenomic library validation.

Phenotypic Screening Successes in Novel Target Discovery

Phenotypic screening has successfully identified first-in-class drugs with unprecedented mechanisms of action (MoA), many of which would have been difficult to discover through purely target-based approaches[sitation:1]. The table below summarizes key examples of approved or clinical-stage compounds originating from phenotypic screens.

Table 1: Novel Mechanisms of Action Uncovered by Phenotypic Screening

| Compound (Approval Year) | Disease Area | Novel Target / Mechanism (MoA) | Key Screening Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risdiplam (2020)[sitation:1] | Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) | SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing modulator; stabilizes the U1 snRNP complex[sitation:1] | Cell-based phenotypic screen[sitation:1] |

| Ivacaftor, Elexacaftor, Tezacaftor (2019 combo)[sitation:1] | Cystic Fibrosis (CF) | CFTR channel potentiator and correctors (enhance folding/trafficking)[sitation:1] | Cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants[sitation:1] |

| Lenalidomide[sitation:1] | Multiple Myeloma | Binds Cereblon E3 ligase, redirecting degradation to proteins IKZF1/IKZF3[sitation:1] | Clinical observation (thalidomide analogue); MoA elucidated post-approval[sitation:1] |

| Daclatasvir[sitation:1] | Hepatitis C (HCV) | Modulates HCV NS5A protein, a target with no known enzymatic activity[sitation:1] | HCV replicon phenotypic screen[sitation:1] |

| SEP-363856[sitation:1] | Schizophrenia | Novel MoA (target agnostic discovery) | Phenotypic screen in disease models |

Experimental Protocols for Phenotypic Screening

The reliability of phenotypic screening data hinges on robust and reproducible experimental protocols. The following methodologies are critical for generating high-quality data suitable for chemogenomic library validation and AI-powered analysis.

High-Content Phenotypic Profiling (Cell Painting Assay)

The Cell Painting assay is a high-content, image-based profiling technique that uses multiplexed fluorescent dyes to reveal the morphological effects of perturbations[sitation:9].

- Cell Model: U2OS osteosarcoma cells are a standard model due to their flat, adherent morphology, ideal for imaging. The protocol is compatible with biologically relevant cell models, including induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells[sitation:9][sitation:10].

- Staining and Fixation: Cells are plated in multiwell plates, perturbed with treatments, then fixed and stained with a panel of dyes targeting key cellular compartments:

- Mitochondria: MitoTracker

- Nucleus: Hoechst 33342 (DNA)

- Nucleoli: Syto 14 (RNA)

- Endoplasmic Reticulum: Concanavalin A

- F-Actin Cytoskeleton: Phalloidin[sitation:9]

- Image Acquisition: Plates are imaged on a high-throughput microscope. Parameters like exposure time and autofocus must be meticulously optimized to prevent overexposed or blurred images, which compromise downstream analysis[sitation:10].

- Image Analysis and Feature Extraction: Automated image analysis software (e.g., CellProfiler) identifies individual cells and measures 1,700+ morphological features across cell, cytoplasm, and nucleus objects. These features quantify size, shape, texture, intensity, and granularity[sitation:9]. Advanced AI platforms like Ardigen's phenAID can further extract high-dimensional features using deep learning[sitation:10].

Chemogenomics Library Screening and Validation

Chemogenomics libraries are collections of small molecules designed to perturb a wide range of biological targets, facilitating target identification and MoA deconvolution in phenotypic screens[sitation:2][sitation:9].

- Library Design: A system pharmacology network is constructed by integrating drug-target-pathway-disease relationships from databases like ChEMBL, KEGG, and Gene Ontology. A diverse library of ~5,000 small molecules is selected to represent a broad panel of drug targets, ensuring coverage of the druggable genome. Scaffold-based analysis is used to maximize structural diversity[sitation:9].

- Screening Execution: The library is screened using the Cell Painting protocol or other phenotypic assays. Best practices include:

- Automation: Automate dispensing and imaging to minimize human error.

- Controls: Include positive and negative controls on every plate.

- Replication & Randomization: Use replicates and randomize sample positions to mitigate batch effects and positional bias[sitation:10].

- Data Integration and Network Analysis: Screening results (morphological profiles) are integrated into a graph database (e.g., Neo4j) with the underlying chemogenomic network. This allows for the connection of a compound-induced phenotypic profile to its known protein targets, pathways, and associated diseases, aiding in MoA hypothesis generation[sitation:9].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for phenotypic screening and data analysis.

Comparative Performance of Screening and Data Platforms

The success of a phenotypic screening campaign is influenced by the chosen strategy and the digital infrastructure supporting it.

Table 2: Comparison of Screening Strategies and Supporting Data Platforms

| Feature | Phenotypic Screening (PDD) | Target-Based Screening (TDD) | AI-Ready Data Platforms (e.g., CDD Vault) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Modulation of a disease phenotype or biomarker[sitation:1] | Modulation of a specific, predefined molecular target[sitation:1] | Structured data capture and management for AI/ML analysis[sitation:4] |

| Strength | Identifies first-in-class drugs; reveals novel biology and polypharmacology[sitation:1] | High throughput; straightforward optimization and derisking[sitation:1] | Ensures data consistency, context, and connectivity for robust AI modeling[sitation:4] |

| Key Challenge | Target identification ("deconvolution") and hit validation[sitation:1] | May miss complex biology and novel mechanisms[sitation:1] | Requires upfront investment in data structuring and metadata management[sitation:4] |

| Hit Rate (Example) | Order of magnitude improvement with AI (DrugReflector) vs. random library[sitation:3] | Varies with target and library; generally high for validated targets | N/A (Enabling infrastructure) |

| Data Management | Requires rich metadata (SMILES, cell line, protocols) for AI-powered insight[sitation:10] | Focuses on binding/activity data against a single target | Provides RESTful APIs, structured templates, and audit trails for FAIR data[sitation:4] |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Platforms

A successful phenotypic screening program relies on a suite of specialized reagents, tools, and data platforms.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Screening

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Dye Set | Multiplexed fluorescent dyes for staining organelles (nucleus, ER, actin, etc.)[sitation:9] | Generating high-dimensional morphological profiles in U2OS or iPS cells[sitation:9] |

| Chemogenomic Library | A curated collection of 5,000+ bioactive small molecules targeting diverse proteins[sitation:9] | Screening to link phenotypic changes to potential targets and mechanisms[sitation:9] |

| ChEMBL Database | Open-source database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties[sitation:5][sitation:9] | Annotating library compounds and building target-pathway networks[sitation:9] |

| CellProfiler / KNIME | Open-source software for automated image analysis (segmentation, feature extraction)[sitation:10] | Extracting quantitative morphological features from high-content images[sitation:9][sitation:10] |

| Scientific Data Management Platform (SDMP) | Platform (e.g., CDD Vault) to manage chemical structures, assays, and metadata[sitation:4] | Creating AI-ready datasets by enforcing structured, FAIR data principles[sitation:4] |

| AI-Powered Phenotypic Analysis | Platform (e.g., Ardigen phenAID) using deep learning for MoA prediction and hit ID[sitation:10] | Predicting compound mode of action from image-based features[sitation:10] |

Phenotypic screening represents a powerful paradigm for expanding the druggable genome and delivering first-in-class therapies with novel mechanisms. Its success hinges on the integration of robust biological models—such as the Cell Painting assay—with carefully validated chemogenomic libraries and a modern data infrastructure capable of supporting AI-driven analysis. While target deconvolution remains a challenge, the synergistic use of network pharmacology, high-content imaging, and machine learning is systematically overcoming this hurdle. As these technologies mature, phenotypic screening is poised to remain a vital engine for the discovery of groundbreaking medicines, particularly for complex diseases that have eluded single-target approaches.

This guide objectively compares two groundbreaking successes in targeted therapy: Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) correctors/potentiators and Survival Motor Neuron 2 (SMN2) splicing modulators. Framed within the context of chemogenomic library validation and phenotypic screening research, this analysis provides a detailed comparison of their clinical performance, supported by experimental data and methodologies.

Article Contents

- Introduction: Overview of Phenotypic Screening Success

- Clinical Efficacy Comparison: Quantitative Outcomes Analysis

- Mechanisms of Action: How The Therapies Work

- Experimental Protocols: Key Research Methodologies

- Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Investigation

The development of CFTR modulators and SMN2 splicing modulators represents a triumph of phenotypic screening, where compounds were first identified based on their ability to reverse a cellular defect without requiring prior knowledge of a specific molecular target. [15] These case studies highlight the power of this approach to generate first-in-class therapies for genetic disorders.

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive disease caused by loss-of-function mutations in the CFTR gene, a chloride channel critical for transepithelial salt and water transport. [16] The most common mutation, Phe508del, causes CFTR protein misfolding, mistrafficking, and premature degradation. [17] [18]

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) is a devastating childhood motor neuron disease caused by mutations in the SMN1 gene leading to insufficient levels of survival motor neuron (SMN) protein. [19] [20] The paralogous SMN2 gene serves as a potential therapeutic target, as it predominantly produces an unstable, truncated protein (SMNΔ7) due to skipping of exon 7 during splicing. [19]

Clinical Efficacy Comparison

The table below summarizes key efficacy data from clinical studies and post-approval observations for these therapeutic classes.

| Therapeutic Class | Specific Agent(s) | Indication | Key Efficacy Metrics | Clinical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFTR Modulators [17] [21] | Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor | Cystic Fibrosis (patients with Phe508del + residual function mutation) | FEV1 improvement: +6.8 percentage points vs placebo [17] | Improved lung function, early intervention most beneficial [17] |

| CFTR Highly Effective Modulator Therapy (HEMT) [21] | Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/ Ivacaftor (ELE/TEZ/IVA) | Cystic Fibrosis (patients with at least one F508del mutation) | Sustained improvement in spirometry, symptoms, and CFTR function (sweat chloride) over 96 weeks [21] | "Life-transforming" clinical benefit; reduction but not elimination of complications [21] |

| CFTR Potentiator [21] [18] | Ivacaftor (VX-770) monotherapy | Cystic Fibrosis (patients with G551D gating mutation) | FEV1 improvement: +10.6% vs placebo at 24 weeks; reduced pulmonary exacerbations [18] | First therapy to target underlying CFTR defect; approved in 2012 [21] [18] |

| SMN2 Splicing Modulator [19] | Risdiplam (Evrysdi) | Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) in adults and children ≥2 months | After 24 months: 32% of patients showed significant motor function improvement; 58% were stabilized [19] | Orally available; increases full-length SMN protein from SMN2 gene [19] |

Mechanisms of Action

The following diagrams illustrate the distinct molecular mechanisms by which these small molecule therapies correct genetic defects.

Mechanism of CFTR Modulators

Mechanism of SMN2 Splicing Modulators

Experimental Protocols

The discovery and validation of these therapies relied on robust phenotypic screening platforms. Below are detailed protocols for key assays used in their development.

Protocol 1: YFP-Based Halide Influx Assay for CFTR Modulators

This high-throughput functional assay was instrumental for identifying CFTR potentiators and correctors. [18]

Primary Application: High-throughput screening for CFTR modulators. Cell Model: Fisher Rat Thyroid (FRT) cells co-expressing mutant CFTR (e.g., Phe508del) and a halide-sensitive yellow fluorescent protein (YFP-H148Q/I152L). Key Reagents:

- YFP-Quenching Iodide Solution: Iodide concentration typically 100 mM.

- Forskolin: cAMP agonist to stimulate CFTR channel opening.

- Test Compounds: Correctors (incubated for 24-48 hours) or Potentiators (added acutely).

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Plate FRT cells in 96-well or 384-well microplates.

- Corrector Incubation (if applicable): Incubate cells with test corrector compounds for 24-48 hours at 37°C to allow for CFTR protein processing and trafficking.

- Potentiator Addition (if applicable): For potentiator screening, pre-incubate cells at a low temperature (e.g., 27°C) for 24 hours to allow some mutant CFTR to reach the membrane. Add test potentiator compounds and forskolin acutely before the assay.

- Fluorescence Measurement: Use a plate reader to record baseline YFP fluorescence.

- Iodide Challenge: Rapidly add the iodide solution to each well.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the initial rate of YFP fluorescence quenching, which is proportional to CFTR-mediated iodide influx. Correctors increase the signal by increasing membrane CFTR; potentiators increase the signal by enhancing channel activity. [18]

Protocol 2: SMN2 Splicing Modulation Assay

This molecular and functional assay identifies compounds that promote inclusion of exon 7 in SMN2 transcripts.

Primary Application: Screening and validation of SMN2 splicing modulators like risdiplam. Cell Model: Patient-derived fibroblasts or motor neurons; SMA mouse models. Key Reagents:

- qRT-PCR Assays: To quantify the ratio of full-length (exon 7 included) to truncated (exon 7 skipped) SMN2 transcripts.

- SMN Protein Detection: Western blot or ELISA for SMN protein quantification.

- Cell Viability/Cytotoxicity Assays: (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo).

Procedure:

- Compound Treatment: Treat cells with the test splicing modulator for a defined period (e.g., 24-72 hours).

- RNA Extraction & cDNA Synthesis: Isolve total RNA and generate cDNA.

- Transcript Analysis: Perform qRT-PCR using primers that distinguish between full-length and Δ7 SMN2 mRNA isoforms. Calculate the percentage of transcripts containing exon 7.

- Protein Analysis: Lyse cells and perform Western blotting to detect increases in full-length SMN protein levels.

- Functional Validation: In advanced validation, treat SMA patient-derived motor neurons and assess improvements in neurite outgrowth or motor neuron survival. [19] [20]

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential reagents and tools that form the foundation of research in this field.

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Halide-Sensitive YFP (YFP-H148Q/I152L) [18] | Genetically encoded sensor for iodide influx; fluorescence quenched by iodide. | Core component of the HTS assay for CFTR modulator discovery. Enables real-time, functional measurement of CFTR activity. |

| Fisher Rat Thyroid (FRT) Cells [18] | Epithelial cell line with low basal halide permeability that forms tight junctions. | Ideal cellular model for CFTR screening assays due to high transfection efficiency and reproducible CFTR expression. |

| SMN2 Mini-gene Splicing Reporters [19] | Constructs containing SMN2 genomic sequences with exons 6-8 and intronic splicing regulators. | Tool for rapid, high-throughput screening of compounds that alter SMN2 exon 7 splicing patterns. |

| Patient-Derived Cell Models (e.g., fibroblasts, iPSC-derived motor neurons) [20] [22] | Cells that naturally express the disease-relevant targets (mutant CFTR or SMN2). | Critical for validating compound efficacy in a pathophysiologically relevant human genetic background. |

| Structural Analogs & Chemogenomic Libraries [6] [15] | Collections of compounds with known target annotations or diverse structures. | Provides a starting point for phenotypic screens and structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies to optimize initial hits. |

Designing and Implementing a Phenotypic Screening Campaign with a Validated Chemogenomic Library

Rational library design represents a foundational step in modern drug discovery, bridging the gap between vast chemical space and practical screening constraints. This guide compares the core strategies—diversity-based, target-focused, and chemogenomic approaches—within the critical context of phenotypic screening. Phenotypic screening, which assesses observable changes in cells or organisms without pre-specified molecular targets, has re-emerged as a powerful method for identifying novel therapeutics, particularly for complex diseases like cancer and neurological disorders [8]. However, its success heavily depends on the underlying compound library, which must be systematically designed to enable both the discovery of active compounds and the subsequent deconvolution of their mechanisms of action [8] [23]. We objectively compare these strategies by synthesizing data from recent publications and screening centers, providing a framework for researchers to select and validate the optimal library for their specific project.

Comparative Analysis of Library Design Strategies

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics, advantages, and limitations of the three primary library design strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of Rational Library Design Strategies

| Design Strategy | Typical Library Size | Target & Pathway Coverage | Reported Hit Rate in Phenotypic Screens | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diversity Library | 86,000 - 125,000 compounds [24] | Broad and unbiased; ~57,000 Murcko Scaffolds [24] | Varies widely; a 5,000-compound subset yielded hits across 35 diverse biological targets [24] | Maximizes chance of discovering novel chemotypes; widely applicable | Lower probability of hitting any specific target; requires larger screening capacity |

| Target-Focused Library | Not explicitly stated | Narrow, focused on specific protein families (e.g., kinases, GPCRs) | High for the intended target class; used for "hit-finding" [8] | High efficiency for established target classes; streamlined discovery | Limited utility for novel biology or polypharmacology |

| Chemogenomic Library | ~1,600 - 5,000 compounds [8] [24] | Wide; designed to cover a large portion of the "druggable genome" [8] [25] | >50% in a multivariate filariasis screen; 2.7% in a bivariate primary screen [26] | Powerful for MoA deconvolution; uses well-annotated probes [25] | Compromise between diversity and depth; annotations are critical |

Experimental Protocols for Library Validation in Phenotypic Screening

Validating a library's utility requires rigorous phenotypic assays. The following protocols, adapted from recent high-impact studies, provide a blueprint for benchmarking library performance.

Multivariate Phenotypic Screening for Macrofilaricidal Leads

This protocol demonstrates how a chemogenomic library was used in a high-content, multiplexed assay to identify and characterize new antifilarial compounds [26].

- Library: A diverse chemogenomic library (e.g., Tocriscreen 2.0) of 1,280 bioactive compounds with known human targets [26].

- Biological System: Brugia malayi microfilariae (mf) and adult worms.

- Primary Screen (Bivariate, using mf):

- Compound Treatment: Treat mf with compounds at a single high concentration (e.g., 100 µM for optimization, 1 µM for screening) in assay plates.

- Phenotypic Measurement 1 (12 hours post-treatment): Acquire video recordings (e.g., 10 frames/well) and quantify motility using image analysis software. Normalize data based on segmented worm area to correct for population density.

- Phenotypic Measurement 2 (36 hours post-treatment): Measure viability using a live/dead stain (e.g., based on heat-killed mf controls).

- Hit Identification: Calculate Z-scores for both phenotypes. Compounds with a Z-score >1 in either phenotype are considered hits.

- Secondary Screen (Multivariate, using adults):

- Hit Validation: Test primary hits in dose-response (e.g., 8-point curves) against mf.

- Multiplexed Adult Profiling: Treat adult worms with validated hits and parallelly assess multiple fitness traits:

- Motility: Quantified via video analysis.

- Fecundity: Measured by counting released mf.

- Metabolism: Assessed using metabolic assays (e.g., AlamarBlue).

- Viability: Determined with vital stains.

- Outcome: This tiered, multivariate approach successfully identified 13 compounds with sub-micromolar potency against adults and characterized their phenotypic profiles, demonstrating high content and efficiency [26].

Phenotypic Profiling in Glioblastoma Patient Cells

This protocol outlines the use of a minimal, rationally designed chemogenomic library for identifying patient-specific vulnerabilities in a complex disease [11].

- Library: A physically available library of 789 compounds, virtually designed to cover 1,320 anticancer protein targets, selected based on cellular activity, chemical diversity, and target selectivity [11].

- Biological System: Glioma stem cells derived from patients with glioblastoma (GBM).

- Experimental Workflow:

- Cell Culture: Maintain patient-derived glioma stem cells under standard conditions.

- Compound Screening: Treat cells with the library compounds.

- Phenotypic Readout: Use high-content imaging (e.g., Cell Painting assay) to measure cell survival and other morphological profiles.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the imaging data to reveal highly heterogeneous phenotypic responses across patients and GBM subtypes.

- Outcome: The targeted library enabled the identification of patient-specific vulnerabilities, highlighting its utility for precision oncology [11].

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of the experimental strategies and the conceptual framework of chemogenomics.

Chemogenomic Phenotypic Screening Workflow

Chemogenomic Library Design Strategy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of the above protocols relies on key reagents and computational resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomic Screening

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Library Design & Validation | Example Sources / Types |

|---|---|---|

| Chemogenomic Compound Library | A collection of well-annotated, bioactive small molecules used as probes to perturb biological systems and link phenotype to target. | In-house collections [24], Tocriscreen 2.0 [26], EUbOPEN initiative [25] |

| Cell Painting Assay Kits | A high-content, morphological profiling assay that uses fluorescent dyes to label multiple cell components, generating rich phenotypic data. | Commercially available dye sets (e.g., MitoTracker, Phalloidin, Concanavalin A) |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Automated microscopes and image analyzers to capture and quantify complex phenotypic changes in cells or whole organisms. | Instruments from vendors like PerkinElmer, Thermo Fisher, Yokogawa |

| Network Analysis Software | Tools to integrate and visualize relationships between compounds, targets, pathways, and diseases (e.g., Neo4j graph database). | Neo4j, Cytoscape, custom R/Python scripts [8] |

| Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) Filters | Computational filters to identify and remove compounds with undesirable properties that often cause false-positive results in assays. | Curated PAINS sets used during assay development and hit triage [24] |

The escalating complexity of human diseases and their underlying molecular mechanisms has fundamentally challenged traditional "one drug, one target" discovery approaches [27]. Integrating systems pharmacology represents a paradigm shift that incorporates biological complexity through the analysis of molecular networks, providing crucial insights into disease pathogenesis and potential therapeutic interventions [27]. This approach examines complex interactions between genes, proteins, metabolites, and small molecules systematically, enabling researchers to identify critical molecular hubs, pathways, and functional modules that may serve as more effective therapeutic targets [27]. For chemogenomic library validation and phenotypic screening research, this network-based perspective is particularly valuable as it provides a conceptual framework for interpreting screening results and linking compound activity to biological function through defined network relationships.

The precision medicine paradigm is centered on therapies targeted to particular molecular entities that will elicit an anticipated and controlled therapeutic response [28]. However, genetic alterations in drug targets themselves or in genes whose products interact with these targets can significantly affect how well a drug works for an individual patient [28]. To better understand these effects, researchers need software tools capable of simultaneously visualizing patient-specific variations and drug targets in their biological context, which can be provided using pathways (process-oriented representations of biological reactions) or biological networks (representing pathway-spanning interactions among genes, proteins, and other biological entities) [28].

Comparative Analysis of Network Pharmacology Platforms

Platform Capabilities and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative analysis of network pharmacology platforms for drug-target-pathway-disease network construction

| Platform | Primary Function | Enrichment Methods | Data Processing Time | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NeXus v1.2 | Automated network pharmacology & multi-method enrichment | ORA, GSEA, GSVA | 4.8s (111 genes); <3min (10,847 genes) | Integrated multi-layer analysis; publication-quality outputs (300 DPI) | Limited to transcriptome data for drug signatures |

| ReactomeFIViz | Drug-target visualization in pathway/network context | Pathway enrichment | Varies by dataset size | High-quality manually curated pathways; Boolean network modeling | Focused on cancer drugs (171 FDA-approved) |

| Cytoscape | Complex network visualization & integration | Via apps (NetworkAnalyzer, CentiScaPe) | Dependent on apps and dataset | Vibrant app ecosystem; domain-independent | Requires manual data preprocessing and format conversion |

| PharmOmics | Drug repositioning & toxicity prediction | Gene-network-based repositioning | Server-dependent processing | Species- and tissue-specific drug signatures | Web server dependency for analysis |

| STRING | Protein-protein interaction network construction | Not primary focus | Rapid network building | High-confidence interaction scores | Limited drug-target integration |

Experimental Data and Validation Performance

Table 2: Experimental validation and performance metrics across platforms and approaches

| Platform/Method | Validation Approach | Key Performance Metrics | Biological System | Result Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NeXus v1.2 | Multiple datasets (111-10,847 genes) | >95% time reduction vs manual workflows; linear time complexity | Traditional medicine formulations | High (automated statistical frameworks) |

| ReactomeFIViz | Sorafenib target profiling | Targets with assay values ≤100nM: FLT3, RET, KIT, RAF1, BRAF | Cancer signaling pathways | High (experimental binding data) |

| Integrated Network Pharmacology + ML | TSGJ for breast cancer; 5 predictive targets identified | SVM, RF, GLM, XGBoost models; molecular docking validation | Breast cancer cell lines | Experimental confirmation (MTT, RT-qPCR) |

| Network Analysis of FDA NMEs | 361 NMEs (2000-2015) with 479 targets | Nerve system NMEs: highest average targets (multi-target) | FDA-approved drug classes | Comparative analysis across ATC classes |

| PharmOmics | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice | Tissue- and species-specific prediction validation | Human, mouse, rat cross-species | Known drug retrieval and toxicity prediction |

Experimental Protocols for Network Construction and Validation

Protocol 1: Multi-Layer Network Construction for Traditional Medicine Formulations

Application: Studying complex plant-compound-gene relationships in traditional medicine, such as TiaoShenGongJian (TSGJ) decoction for breast cancer [29].

Methodology:

- Bioactive Component Identification: Screen bioactive compounds and corresponding targets from specialized databases (e.g., TCMSP) using filter parameters (oral bioavailability ≥30%; drug likeness ≥0.18) [29].

- Disease Target Collection: Retrieve disease-related targets from genomic databases (GeneCards, PharmGkb, DisGeNET, OMIM) with relevance score thresholds (>10 for GeneCards) [29].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Utilize GEO datasets to identify differentially expressed genes (|log2(fold change)| >1; adjusted p-value <0.05) using "limma" package in R [29].

- Network Construction: Import intersecting targets of bioactive compounds and disease into STRING platform (confidence score >0.4; protein type: "Homo sapiens") [29].

- Topological Analysis: Calculate network centrality measures (degree, eigenvector, betweenness, closeness) using CytoNCA plugin in Cytoscape to identify hub genes [29].

Validation: Machine learning algorithms (SVM, RF, GLM, XGBoost) identify key predictive targets, with subsequent molecular docking confirmation and experimental validation (MTT, RT-qPCR assays) [29].

Protocol 2: Drug-Target Interaction Evidence Visualization

Application: Investigating supporting evidence for interactions between a drug and all its targets, including off-target effects [28].

Methodology:

- Drug Selection: Access 171 FDA-approved cancer drugs from Cancer Targetome or 2,102 worldwide approved drugs from DrugCentral within ReactomeFIViz [28].

- Evidence Filtering: Filter target interaction evidence according to strength of supporting assay values (e.g., ≤100 nM for high-confidence interactions) [28].

- Visualization: Display filtered interactions as either a table or histogram to assess drug-target relationships [28].

- Pathway Mapping: Map all target interactions to pathways and perform enrichment analysis to identify pathways with significant number of targeted entities [28].

- Pathway Perturbation Modeling: Use Boolean network or constrained fuzzy logic modeling to investigate effect of drug perturbation on pathway activities [28].

Case Example: Sorafenib target analysis reveals multiple potential targets with assay values under 100 nM, including FLT3, RET, KIT, RAF1, and BRAF, explaining its known "multi-kinase" inhibitor activity [28].

Diagram 1: Workflow for constructing drug-target-pathway-disease networks integrating multiple data types and analytical approaches.

Computational Tools and Databases

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational resources for network pharmacology

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Network Construction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoscape | Software platform | Complex network visualization and integration | Core environment for network visualization and analysis |

| ReactomeFIViz | Cytoscape app | Drug-target visualization in biological context | Pathway and network-based analysis of drug targets |

| NeXus v1.2 | Automated platform | Network pharmacology and multi-method enrichment | Integrated multi-layer network analysis |

| STRING | Database/Web tool | Protein-protein interaction network construction | Building protein interaction networks for targets |

| TCMSP | Database | Traditional Chinese Medicine systems pharmacology | Identifying bioactive components and targets |

| DrugBank | Database | Drug and drug-target information | Annotating drugs and their molecular targets |

| GeneCards | Database | Human gene database | Collecting disease-related targets |

| PharmOmics | Database/Tool | Drug repositioning and toxicity prediction | Species- and tissue-specific drug signature analysis |

Application in Chemogenomic Library Validation

Network pharmacology approaches provide critical validation frameworks for chemogenomic libraries by enabling systematic mapping of compound-target interactions to biological pathways and disease networks. The integration of machine learning algorithms with network analysis has demonstrated particular utility in identifying key predictive targets from high-dimensional screening data [29]. For instance, in the study of TSGJ decoction for breast cancer, network pharmacology identified 160 common targets, with 30 hub targets emerging from protein-protein interaction analysis [29]. Machine learning methods then screened these to identify five predictive targets (HIF1A, CASP8, FOS, EGFR, PPARG), which were subsequently validated for their diagnostic, biomarker, immune, and clinical values [29].

The application of Boolean network modeling in ReactomeFIViz further enables researchers to investigate the effect of drug perturbations on pathway activities, providing a critical link between chemogenomic screening results and their functional consequences [28]. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding drug resistance mechanisms, which can occur through gatekeeper mutations in direct drug targets or through mutations in non-drug targets that enable bypass resistance pathways [28]. Such network-based analyses help validate phenotypic screening results by placing them in the context of known biological pathways and networks.

Diagram 2: Mathematical models of drug resistance evolution integrating phenotype dynamics and treatment responses.

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The integration of systems pharmacology approaches provides a powerful framework for building comprehensive drug-target-pathway-disease networks that can significantly enhance chemogenomic library validation and phenotypic screening research. Current platforms like NeXus v1.2, ReactomeFIViz, and Cytoscape with its extensive app ecosystem offer complementary capabilities for different aspects of network construction and analysis [28] [30] [27]. The recent advancement in automation, as demonstrated by NeXus v1.2's >95% reduction in analysis time compared to manual workflows, addresses a critical bottleneck in network pharmacology applications [27].

Future developments in this field are likely to focus on several key areas. First, the integration of artificial intelligence with network pharmacology approaches shows particular promise, as demonstrated by the successful combination of network analysis with machine learning algorithms to identify key predictive targets [29]. Second, the incorporation of single-cell sequencing technologies and CRISPR libraries will provide higher-resolution data for network construction, enabling more precise mapping of drug-target interactions [31] [32]. Finally, the development of more sophisticated mathematical models of phenotype dynamics, such as those quantifying drug resistance evolution, will enhance our ability to predict therapeutic outcomes from network perturbations [31].

For researchers engaged in chemogenomic library validation, these network pharmacology approaches offer a systematic framework for interpreting screening results, identifying mechanisms of action, and predicting potential resistance mechanisms. By placing screening hits in the context of biological networks, researchers can prioritize compounds with more favorable polypharmacology profiles and identify potential combination therapies that target multiple nodes in disease-relevant networks.

High-content phenotypic profiling has revolutionized modern drug discovery and chemical safety assessment. Among these approaches, the Cell Painting assay has emerged as a powerful, untargeted method for capturing multifaceted morphological changes in cells subjected to genetic or chemical perturbations. By using multiplexed fluorescent dyes to visualize multiple organelles simultaneously, it generates rich, high-dimensional data that can reveal subtle phenotypes and mechanisms of action (MoA). As the field progresses, innovative adaptations and complementary methodologies are expanding its capabilities. This guide objectively compares the performance of the standard Cell Painting assay with emerging alternatives, providing experimental data and detailed protocols to inform their application in chemogenomic library validation and phenotypic screening.

Table 1: Comparison of Phenotypic Profiling Approaches

| Methodology | Core Principle | Multiplexing Capacity | Key Advantages | Reported Performance & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting (Standard) | Multiplexed staining of 6-8 organelles with 5-6 fluorescent dyes in a single cycle [33] [34]. | Labels nucleus, nucleoli, ER, actin, Golgi, and mitochondria [33]. | • Well-established and standardized protocol [35]• High-throughput suitability [36]• Publicly available large datasets (e.g., JUMP-Cell Painting) [37] | • Adaptability: Successfully adapted from 384-well to 96-well plates, with most benchmark concentrations (BMCs) differing by <1 order of magnitude across experiments [35].• Cell Line Applicability: Effective across diverse cell lines (U-2 OS, MCF7, HepG2, A549) without adjusting cytochemistry protocol [36]. |

| Cell Painting PLUS (CPP) | Iterative staining-elution cycles allow sequential labeling and imaging [37]. | Increased capacity for ≥7 dyes, labeling 9 compartments (e.g., adds lysosomes), each in a separate channel [37]. | • Improved organelle-specificity and signal separation• High customizability for specific research questions• No spectral crosstalk between channels | • Enhanced Specificity: Eliminates signal merge (e.g., RNA/ER, Actin/Golgi), yielding more precise profiles [37].• Limitation: Requires careful dye characterization and imaging within 24 hours for signal stability [37]. |

| Live-Cell Viability Profiling | Live-cell multiplexed assay using low-concentration dyes for time-resolved imaging [38]. | Typically 3-4 dyes for nucleus, mitochondria, and tubulin cytoskeleton [38]. | • Captures kinetic profiles of cytotoxicity• Identifies early vs. late apoptotic events• Can delineate primary from secondary target effects | • Functional Annotation: Excellent for annotating chemogenomic libraries for general cell health effects [38].• Limited Scope: Less comprehensive morphologic profiling compared to fixed-cell methods like Cell Painting [38]. |

Table 2: Key Reagents and Research Solutions

| Item | Function in Assay | Example Dyes & Concentrations |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Stain | Identifies individual cells and enables segmentation and analysis of nuclear morphology. | Hoechst 33342 (5 µg/mL) [34] |

| Cytoplasmic & RNA Stain | Defines the cytoplasmic region and labels cytoplasmic RNA and nucleoli. | SYTO 14 green fluorescent nucleic acid stain (3 µM) [34] |

| Actin Cytoskeleton Stain | Labels F-actin filaments, revealing changes in cell shape and structure. | Phalloidin/Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate (5 µL/mL) [34] |

| Golgi Apparatus & Plasma Membrane Stain | Visualizes the Golgi apparatus and outlines the plasma membrane. | Wheat-germ agglutinin (WGA)/Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate (1.5 µg/mL) [34] |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stain | Labels the endoplasmic reticulum, a key organelle for protein synthesis and folding. | Concanavalin A/Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (100 µg/mL) [34] |

| Mitochondrial Stain | Visualizes the mitochondrial network, indicative of cellular health and metabolic state. | MitoTracker Deep Red (500 nM) [34] |

| Fixation Agent | Preserves cellular morphology at the time of fixation. | Paraformaldehyde (PFA, 3.2-4%) [37] [34] |

| Permeabilization Agent | Creates pores in the cell membrane to allow dye entry for intracellular staining. | Triton X-100 (0.1%) [34] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Standard Cell Painting Assay Protocol

The following protocol, adapted for a 96-well plate format, demonstrates the robustness of the method for lower-throughput laboratories [35].

- Cell Culture and Seeding: Use U-2 OS human osteosarcoma cells cultured in McCoy’s 5a medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Seed cells at a density of 5,000 cells per well in a 96-well plate 24 hours before chemical exposure. Note: Cell seeding density has been identified as a significant experimental factor that can inversely influence the resulting Mahalanobis distances, a measure of phenotypic change [35].

- Chemical Treatment: Prepare reference compounds in DMSO and serially dilute them. Replace culture media with exposure media containing the compounds at 0.5% v/v DMSO final concentration. Include vehicle controls (0.5% DMSO). Expose cells for 24 hours. Conduct four independent biological replicates for statistical power [35].

- Staining and Fixation: Live-stain mitochondria with MitoTracker Deep Red (500 nM) for 30 minutes. Fix cells with 3.2% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes. Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 minutes. Incubate with the pre-mixed staining cocktail containing Hoechst, Phalloidin, Concanavalin A, WGA, and SYTO 14 for 30 minutes at room temperature [34].

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Acquire images using a high-content imaging system (e.g., Opera Phenix or ImageXpress Micro Confocal) with a 20x objective. Extract ~1,300 morphological features per cell using analysis software (e.g., Columbus, IN Carta). Normalize well-level data to vehicle controls and use multivariate analysis (e.g., Principal Component Analysis) to compute a Mahalanobis distance for each treatment. Model these distances to calculate a Benchmark Concentration (BMC) for toxicity [35] [34].

Cell Painting PLUS (CPP) Staining Cycle

The CPP protocol introduces iterative staining and elution to expand multiplexing capacity [37].

- First Staining Cycle: Fix cells with 4% PFA. Simultaneously stain for Actin, Golgi, Plasma Membrane, RNA, ER, and Nuclear DNA. Image each dye in a separate, dedicated channel.

- Dye Elution: Apply the CPP elution buffer (0.5 M L-Glycine, 1% SDS, pH 2.5) to remove the fluorescent signals from the first cycle while preserving cellular morphology.

- Second Staining Cycle: Stain the same cells for Mitochondria and Lysosomes. Image these dyes in their separate channels.

- Data Integration: Use the mitochondrial channel from the second cycle as a reference to register and combine image stacks from both cycles into a single, high-dimensional dataset for analysis [37].

Workflow and Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for selecting a phenotypic profiling strategy, particularly in the context of chemogenomic library validation.

Performance Analysis and Data Interpretation

The utility of phenotypic profiling data heavily depends on the chosen method for hit identification – distinguishing biologically active treatments from inactive ones.

- Hit Identification Strategies: A comparative study of Cell Painting data evaluated multiple approaches. Feature-level and category-based modeling identified the highest number of active hits. Approaches using distance metrics (Euclidean, Mahalanobis) showed the lowest likelihood of identifying high-potency false positives from assay noise. Methods based on single-concentration analysis (signal strength, profile correlation) detected the fewest actives. Despite these differences, there was high concordance for 82% of test chemicals, indicating that hit calls are generally robust across sound analytical methods [39].

- Application in Toxicology: When applied to the hazard assessment of environmental chemicals, Cell Painting has demonstrated high value. Studies screening over 1,000 chemicals showed that the bioactivity predictions (Benchmark Concentrations or BMCs) were as conservative or more protective than comparable in vivo effect levels 68% of the time. Furthermore, when HTPP data were combined with other endpoints like transcriptomics, they provided complementary and unique data streams, enhancing mechanistic understanding [35].

The standard Cell Painting assay remains a robust, well-validated tool for high-throughput phenotypic profiling, especially in large-scale screening and chemogenomic library validation. Its performance is characterized by high adaptability and inter-laboratory consistency. The emerging Cell Painting PLUS method offers a superior solution for projects demanding the highest level of organelle-specificity and customizability, albeit with a more complex workflow. For focused studies on cell health and cytotoxicity kinetics, live-cell multiplexed assays provide invaluable, time-resolved data. The choice of analysis pipeline, particularly for hit identification, further influences the outcomes and should be tailored to the screening goals, with a preference for multi-concentration methods that minimize false positives. Together, these methodologies form a powerful toolkit for deconvoluting the mechanisms of chemical and genetic perturbations in modern biological research.

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most aggressive primary brain tumor in adults, characterized by high inter- and intratumoral heterogeneity, with a median overall survival of only 8 months and a 5-year survival rate of 7.2% [40]. The standard treatment regimen for GBM patients includes surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, yet recurrence is nearly universal, occurring in over 90% of patients within six to nine months after initial therapy [41]. This poor prognosis is largely attributed to the presence of therapy-resistant glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) and the complex molecular landscape of the tumors [42] [40].

In recent years, phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) has resurged as a powerful strategy for identifying first-in-class therapeutics, particularly for complex diseases like GBM where single-target approaches have largely failed [7] [43]. Unlike target-based approaches, PDD does not rely on preconceived hypotheses about specific molecular targets but instead screens compounds for their ability to modify disease-relevant phenotypes in physiologically representative models [7]. This approach has led to the discovery of novel mechanisms of action and has expanded the "druggable target space" to include unexpected cellular processes [7].

The convergence of several advanced technologies has created new opportunities for GBM drug discovery: improved culture methods for patient-derived GBM stem cells (GSCs), CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, and high-content phenotypic screening platforms [42]. Central to these advances is the use of patient-derived spheroids and organoids that better recapitulate the cellular diversity, architecture, and therapeutic responses of native tumors compared to traditional 2D cell lines [44] [40]. This case study examines the application of chemogenomic libraries in phenotypic screening platforms using patient-derived GBM spheroids, highlighting experimental designs, key findings, and practical implementation considerations for researchers.

Chemogenomic Libraries: Design and Composition for GBM Screening