Target Specificity Validation for Phenotypic Screening Hits: Strategies for Deconvolution and Mechanistic Insight

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating the target specificity of hits derived from phenotypic screening.

Target Specificity Validation for Phenotypic Screening Hits: Strategies for Deconvolution and Mechanistic Insight

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating the target specificity of hits derived from phenotypic screening. It explores the fundamental importance of target deconvolution in bridging phenotypic observations with mechanistic understanding, details a suite of experimental and computational methodologies from chemoproteomics to knowledge graphs, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and establishes frameworks for rigorous validation and comparative analysis. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging technologies, this resource aims to enhance the efficiency and success rate of translating promising phenotypic hits into targeted therapeutic candidates with well-defined mechanisms of action.

The Critical Link: Why Target Deconvolution is Essential in Phenotypic Drug Discovery

In the pursuit of new therapeutics, researchers primarily employ two discovery strategies: phenotypic screening and target-based screening. These approaches represent fundamentally different philosophies in identifying chemical starting points for drug development. Phenotypic drug discovery involves screening compounds for their effects on whole cells, tissues, or organisms, measuring complex biological outcomes without prior assumptions about specific molecular targets [1] [2]. In contrast, target-based drug discovery begins with a predefined, purified molecular target—typically a protein—and screens for compounds that interact with it in a specific manner, such as inhibiting an enzyme or blocking a receptor [3] [1].

The central challenge lies in what is known as the "phenotype-target gap"—the disconnect between observing a beneficial cellular effect and identifying the precise molecular mechanism responsible for it. Bridging this gap is crucial for optimizing lead compounds, understanding potential toxicity, and developing predictive biomarkers for clinical development. This guide examines the comparative strengths and limitations of both approaches and presents integrated methodologies to connect cellular phenotypes to molecular targets.

Comparative Analysis: Phenotypic vs. Target-Based Screening

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of Phenotypic and Target-Based Screening Approaches

| Parameter | Phenotypic Screening | Target-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Measures effects in biologically complex systems (cells, tissues) [1] | Uses purified molecular targets to identify specific interactions [3] |

| Key Advantage | Identifies first-in-class medicines; captures system complexity; unbiased mechanism [4] [1] | Rational design; higher throughput; clear mechanism from outset [3] [1] |

| Primary Limitation | Difficult target deconvolution; often lower throughput [1] [2] | Relies on pre-validated targets; may overlook complex biology [3] [1] |

| Success Profile | More successful for first-in-class medicines [4] [2] | More effective for best-in-class medicines [2] |

| Target Identification | Required after screening (target deconvolution) [1] | Defined before screening [3] |

| Physiological Relevance | Higher—captures cell permeability, metabolism [2] | Lower—may not reflect cellular context [3] |

Table 2: Experimental and Practical Considerations

| Consideration | Phenotypic Screening | Target-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Moderate (more complex assays) [2] | High (simplified assay systems) [2] |

| Assay Development | Can be complex, requiring phenotypic endpoints [5] | Typically straightforward with purified components |

| Hit Validation | Requires extensive deconvolution work [1] [6] | Mechanism is immediately known [3] |

| Chemical Matter | May have unfavorable properties (e.g., solubility) [2] | Can be optimized for target binding from start |

| Key Technologies | High-content imaging, transcriptomics, CRISPR [1] [2] | X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, molecular docking [3] [1] |

| Clinical Translation | Can be challenging without known mechanism [1] | Biomarker strategy can be rationally designed [1] |

Methodologies for Target Deconvolution

When a compound with promising phenotypic activity is identified, several experimental approaches can be employed to identify its molecular target(s).

Chemical Proteomics

This methodology uses chemical probes derived from active compounds to pull down interacting proteins from cell lysates.

Table 3: Chemical Proteomics Workflow for Target Deconvolution

| Step | Protocol Details | Key Reagents |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Design | Synthesize compound derivatives with affinity tags (biotin, fluorescein) or photo-crosslinkers without losing biological activity [6]. | Active compound precursor, biotinylation reagents, photo-activatable moieties |

| Cell Lysis | Prepare lysates from relevant cell lines under non-denaturing conditions to preserve native protein structures [5]. | Lysis buffer, protease inhibitors, phosphatase inhibitors |

| Affinity Purification | Incubate lysate with immobilized probe; include excess untagged compound in control to identify specific binders [6]. | Streptavidin beads, magnetic separation equipment |

| Protein Identification | Analyze purified proteins by mass spectrometry; compare experimental and control samples to identify specifically bound targets [6]. | Mass spectrometry, protein database search software |

Functional Genomic Approaches

These methods use genetic perturbations to identify genes that modify compound sensitivity or are required for its activity.

Table 4: Functional Genomic Methods for Target Identification

| Method | Experimental Protocol | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Screening | Perform genome-wide CRISPR knockout or inhibition screen; treat cells with compound; sequence gRNAs to identify sensitizing or resistant mutations [6]. | Identification of synthetic lethal interactions, drug mechanism pathways [6] |

| RNAi Screening | Transferc cell pools with siRNA or shRNA libraries; treat with compound; quantify surviving cells by sequencing to identify target genes [6]. | Similar to CRISPR but with transient knockdown effects |

| Resistance Screening | Generate resistant clones by prolonged compound exposure; sequence genomes to identify mutations that confer resistance [6]. | Direct target identification through compensatory mutations |

Transcriptional Profiling

This approach uses gene expression changes induced by compound treatment to infer mechanism of action through pattern matching.

Protocol: Treat relevant cell models with compound or vehicle control; isolate RNA at multiple time points; perform RNA-seq or L1000 assay; compare signature to databases of known profiles; predict targets based on similarity to compounds with known mechanisms [3].

Integrated Workflows: Bridging the Gap

Leading-edge research now focuses on integrating phenotypic and target-based approaches to leverage their complementary strengths.

The ExMolRL Framework

A novel computational framework called ExMolRL demonstrates how artificial intelligence can bridge the phenotype-target gap. This approach uses multi-objective reinforcement learning to generate molecules optimized for both phenotypic effects and target affinity [3].

Hybrid Experimental Screening

Combining phenotypic and target-based screening in an iterative fashion creates a powerful discovery engine.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Reagent Solutions for Phenotype-Target Research

| Reagent/Category | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Libraries | Genome-wide gene knockout for functional genomic screens [6] | Identify genes essential for compound activity; both genome-wide and focused libraries available |

| Affinity Tagging Reagents | Chemical modification of compounds for pull-down experiments [6] | Biotin, fluorescent tags; critical for chemical proteomics approaches |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Detection of signaling pathway activation/inhibition | Assess compound effects on key cellular pathways |

| 3D Culture Matrices | Create physiologically relevant model systems [5] | Matrigel, alginate scaffolds; improve translational prediction |

| Multi-Omics Platforms | Integrated analysis of transcriptomic, proteomic data [1] | Connect phenotypic changes to molecular pathways |

| Fragment Libraries | Identify weak binders for difficult targets [6] | Low molecular weight compounds; useful for target-based approaches |

The historical dichotomy between phenotypic and target-based drug discovery is gradually being replaced by integrated approaches that leverage the strengths of both paradigms. Phenotypic screening excels at identifying novel biology and first-in-class therapies operating through unprecedented mechanisms, while target-based approaches provide precision and facilitate optimization. Bridging the phenotype-target gap requires methodical application of deconvolution technologies—including chemical proteomics, functional genomics, and transcriptional profiling—alongside emerging computational frameworks that simultaneously optimize for phenotypic outcomes and target engagement. The most successful drug discovery pipelines will continue to evolve hybrid strategies that maintain the biological relevance of phenotypic screening while incorporating the mechanistic clarity of target-based approaches.

The Strengths and Inherent Challenges of Phenotypic Screening

Phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) has experienced a significant resurgence over the past decade, re-establishing itself as a powerful approach for identifying first-in-class medicines. Unlike target-based drug discovery (TDD), which focuses on modulating specific molecular targets, PDD is agnostic to the mechanism of action, instead selecting compounds based on their effects in disease-relevant biological systems [7] [8]. This empirical strategy has led to breakthrough therapies for conditions ranging from cystic fibrosis to spinal muscular atrophy by revealing unprecedented biological targets and mechanisms [8]. However, this approach also presents distinct challenges, particularly in hit validation and target identification, that require sophisticated experimental and computational strategies to overcome [7]. This guide examines the comparative advantages and limitations of phenotypic screening within the critical context of target specificity validation for research hits.

Core Strengths and Challenges: A Comparative Analysis

The value proposition of phenotypic screening lies in its ability to address biological complexity, though this comes with inherent trade-offs in mechanistic deconvolution.

Table 1: Core Strengths and Challenges of Phenotypic Screening

| Aspect | Strengths | Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Identifies first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms of action (nMoA); agnostic to prior target hypotheses [9] [8]. | Does not guarantee a druggable, single molecular target; mechanism of action (MoA) often requires extensive deconvolution [9] [10]. |

| Biological Relevance | Models disease complexity in physiologically relevant systems (e.g., primary cells, co-cultures, iPSCs); outputs closer to clinical phenotype [9] [10]. | Assays are often more technically challenging, lower throughput, and costly than target-based assays [10] [6]. |

| Target & Chemical Space | Expands "druggable" space to include non-enzymatic targets, protein complexes, and new MoAs (e.g., splicing correction, protein stabilization) [8]. | Hit compounds may exhibit polypharmacology (activity at multiple targets), complicating optimization and liability prediction [8] [6]. |

| Translational Potential | Historically more successful for discovering first-in-class drugs; accounts for compound efficacy, permeability, and toxicity early on [9] [8]. | The path to the clinic can be hindered if a specific MoA is required for regulatory approval or safety de-risking [7]. |

Key Experimental Protocols for Validation

Success in phenotypic screening relies on robust assays and rigorous hit validation. The following workflows are central to establishing confidence in screening hits and progressing toward target identification.

Phenotypic Assay Design and Hit Triage

A well-designed phenotypic assay is the cornerstone of a successful campaign. The "Rule of 3" proposes that optimal assays should: 1) use highly disease-relevant assay systems (e.g., primary human cells, iPSC-derived tissues), 2) maintain disease-relevant physiological stimuli, and 3) employ assay readouts that are as close as possible to the clinically desired outcome [9].

- Workflow: After a primary screen, hit validation involves several key steps to eliminate false positives and prioritize the most promising leads [11] [12].

- Confirmatory Dose-Response: Test hits in a fresh dose-response experiment to confirm potency and efficacy.

- Chemical Purity and Identity Assessment: Verify compound structure and purity (e.g., via LC-MS, NMR).

- Counterscreening: Rule out undesirable mechanisms like assay interference (e.g., fluorescence, cytotoxicity).

- Selectivity Profiling: Use secondary phenotypic assays to confirm the desired activity is not a general cell health effect.

- Tool Compound Scoring: Employ evidence-based metrics like the Tool Score (TS) to systematically rank compounds based on their reported strength and selectivity, helping avoid promiscuous or poorly characterized chemical tools [11].

Mechanism of Action (MoA) and Target Identification

Determining a compound's MoA is a major challenge in PDD. The following table outlines established methodologies for target deconvolution, which can be used individually or in an integrated fashion [9] [8].

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Target Identification in Phenotypic Screening

| Method | Experimental Protocol | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Chromatography & Proteomics | A bioactive compound is immobilized on a solid support to create a "fishing" resin. Incubate the resin with cell lysates, wash away non-specific binders, and elute specifically bound proteins for identification via mass spectrometry (e.g., SILAC, LC/MS) [9]. | Identifies direct protein binding partners of the small molecule. |

| Genomic/Genetic Approaches | Resistance Mutation Selection: Grow cells under long-term drug pressure and sequence clones that survive, identifying mutations in the drug target. CRISPR/RNAi Screens: Use genetic perturbation libraries to identify genes whose loss modulates sensitivity or resistance to the compound [9] [13]. | Reveals proteins and pathways essential for the compound's phenotypic effect. |

| Gene Expression Profiling | Treat disease-relevant cells with the compound and analyze global transcriptomic changes using DNA microarrays or RNA-Seq. Compare the resulting signature to databases of known drug signatures (e.g., Connectivity Map) [9] [7]. | Infers MoA by linking to modulated pathways and known bioactives, generating testable hypotheses. |

| Computational Profiling | Input the compound's structural features and/or phenotypic profile (e.g., from Cell Painting) into machine learning models to predict potential targets based on similarity to well-annotated compounds [9] [6]. | Enables rapid, hypothesis-free MoA prediction based on large-scale pattern recognition. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Executing a phenotypic screening campaign requires a suite of specialized research tools and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Phenotypic Screening and Validation

| Research Tool | Function in Phenotypic Screening |

|---|---|

| Primary Human Cells / iPSCs | Provide disease-relevant biological context with human genetics, improving translational predictivity over immortalized cell lines [9] [10]. |

| Genetic Barcoding & Lineage Tracing | Enables tracking of clonal dynamics and evolution of resistance in pooled populations, allowing inference of phenotype dynamics without direct measurement [13]. |

| CRISPR/siRNA Libraries | Functional genomics tools for genetic modifier screens, used to identify genes that confer sensitivity or resistance to a phenotypic hit, informing on MoA and targets [9] [6]. |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Automates the quantitative analysis of complex morphological phenotypes (e.g., neurite outgrowth, organelle structure) in multi-parameter assays [10]. |

| Annotated Chemogenomic Libraries | Collections of compounds with known activity against specific targets; used for screening or as a reference to triangulate the MoA of novel hits [11] [6]. |

| Immobilized Compound Resins | Key reagent for affinity chromatography; the solid-phase support to which a hit compound is covalently linked for pulling down direct protein targets from cell lysates [9]. |

Phenotypic screening stands as a powerful, biology-first discovery strategy capable of delivering transformative therapies by engaging novel biology. Its principal strength lies in its ability to model disease complexity and reveal entirely new therapeutic mechanisms without being constrained by pre-defined target hypotheses. The inherent challenge of target deconvolution, while significant, is being met with an increasingly sophisticated arsenal of experimental and computational methods. A successful PDD campaign therefore hinges on strategically integrating these MoA elucidation techniques from the outset, ensuring that promising phenotypic hits can be translated into well-characterized lead candidates and, ultimately, first-in-class medicines.

The Impact of Deconvolution on Lead Optimization and Safety Profiling

Target deconvolution, the process of identifying the molecular target(s) of a chemical compound in a biological context, serves as a critical bridge between phenotypic screening and subsequent drug development stages [14]. In phenotypic drug discovery, researchers identify chemical compounds based on their ability to evoke a desired phenotype without prior knowledge of the specific molecular target [14] [1]. Once a promising molecule is identified, target deconvolution clarifies its mechanism of action, encompassing both on-target and off-target interactions [14]. This process has become indispensable in modern pharmaceutical research, enabling more efficient structure-based optimization and mechanistic validation of hits emerging from phenotypic screens [15].

The strategic importance of deconvolution extends profoundly into lead optimization and safety profiling. By identifying a compound's direct molecular targets and downstream affected pathways, researchers can rationally optimize lead compounds to enhance on-target activity while minimizing off-target effects [14]. Furthermore, comprehensive target identification enables early detection of potential safety issues, guiding the development of safer therapeutic candidates [14]. As drug discovery increasingly embraces complex phenotypic models and artificial intelligence, sophisticated deconvolution strategies have evolved to keep pace with these advancements [16] [17].

Key Deconvolution Technologies and Methodologies

Experimental Deconvolution Approaches

Multiple experimental strategies have been developed for target deconvolution, each with distinct advantages and applications. These methods broadly fall into affinity-based, activity-based, and label-free categories.

Affinity-Based Chemoproteomics: This approach involves modifying a compound of interest so it can be immobilized on a solid support, then exposing it to cell lysate to isolate binding proteins through affinity enrichment [14]. The captured proteins are subsequently identified via mass spectrometry. This technique provides dose-response profiles and IC50 information, making it suitable for a wide range of target classes [14]. A key requirement is a high-affinity chemical probe that retains biological activity after immobilization.

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP): ABPP employs bifunctional probes containing both a reactive group and a reporter tag [14]. These probes covalently bind to molecular targets in cells or lysates, labeling target sites for subsequent enrichment and identification. In one variation, samples are treated with a promiscuous electrophilic probe with and without the compound of interest; targets are identified as sites whose probe occupancy is reduced by compound competition [14]. This approach is particularly powerful for profiling reactive cysteine residues but requires accessible reactive residues on target proteins.

Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL): PAL utilizes trifunctional probes containing the compound of interest, a photoreactive moiety, and an enrichment handle [14]. After the small molecule binds to target proteins in living cells or lysates, light exposure induces covalent bond formation between the photogroup and target. The handle then enables enrichment of interacting proteins for identification by mass spectrometry. PAL is especially valuable for studying integral membrane proteins and identifying transient compound-protein interactions that might be missed by other methods [14].

Label-Free Techniques: These approaches detect compound-protein interactions under native conditions without chemical modification of the compound. Solvent-induced proteome profiling (SPP) detects ligand binding-induced shifts in protein stability through proteome-wide denaturation curves [18]. By comparing denaturation kinetics with and without compound treatment, researchers can identify target proteins based on increased stability upon ligand binding [14]. This method is particularly valuable for detecting interactions in physiologically relevant contexts but can be challenging for low-abundance or membrane proteins [14].

Computational Deconvolution Approaches

Computational methods have emerged as powerful complements to experimental deconvolution, leveraging growing biological databases and artificial intelligence.

Knowledge Graph Approaches: Protein-protein interaction knowledge graphs (PPIKG) integrate diverse biological data to predict direct targets [19]. In one application to p53 pathway activators, researchers constructed a PPIKG that narrowed candidate proteins from 1088 to 35, significantly accelerating target identification [19]. Subsequent molecular docking pinpointed USP7 as a direct target for the p53 activator UNBS5162, demonstrating how knowledge graphs efficiently prioritize candidates for experimental validation [19].

Selectivity-Based Screening: Researchers have developed data-driven approaches that mine large bioactivity databases like ChEMBL (containing over 20 million bioactivity data points) to identify highly selective compounds for target deconvolution [15] [20]. These selective tool compounds, when used in phenotypic screens, provide immediate mechanistic insights when activity is observed. One study developed a novel scoring system incorporating both active and inactive data points across targets, ultimately identifying 564 highly selective compound-target pairs from purchasable compounds [20]. When screened against cancer cell lines, several compounds demonstrated selective growth inhibition patterns that immediately suggested their mechanisms of action [20].

AI-Powered Platforms: Modern AI drug discovery platforms integrate multimodal data (omics, chemical structures, literature, clinical data) to construct comprehensive biological representations [21]. For instance, Insilico Medicine's Pharma.AI platform leverages 1.9 trillion data points from over 10 million biological samples and 40 million documents using natural language processing and machine learning to uncover therapeutic targets [21]. Similarly, Recursion OS utilizes knowledge graphs to perform target deconvolution, identifying molecular targets behind phenotypic responses by evaluating promising signals through multiple biological lenses including protein structures and clinical trials [21].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Deconvolution Technologies

| Technology | Mechanism | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity-Based Chemoproteomics [14] | Compound immobilization and affinity purification | Broad target identification, dose-response studies | Works for diverse target classes, provides binding affinity data | Requires high-affinity, immobilizable probe |

| Activity-Based Protein Profiling [14] | Covalent labeling of active sites | Enzyme families, reactive residue profiling | High sensitivity for enabled target classes | Limited to proteins with accessible reactive residues |

| Photoaffinity Labeling [14] | Photo-induced covalent crosslinking | Membrane proteins, transient interactions | Captures weak/transient interactions, works in live cells | May not suit shallow binding sites, probe design complexity |

| Solvent Proteome Profiling [18] [14] | Ligand-induced protein stability shifts | Native condition screening, off-target profiling | Label-free, physiologically relevant context | Challenging for low-abundance and membrane proteins |

| Knowledge Graph Approaches [19] | Network biology and link prediction | Target hypothesis generation, systems biology view | Leverages existing knowledge, hypothesis-agnostic | Dependent on data completeness and quality |

| Selectivity-Based Screening [15] [20] | Bioactivity database mining | Phenotypic screen follow-up, mechanism elucidation | Provides immediate mechanistic insights when active | Limited to targets with known selective compounds |

Deconvolution Workflows in Practice

Integrated Experimental-Computational Pipeline

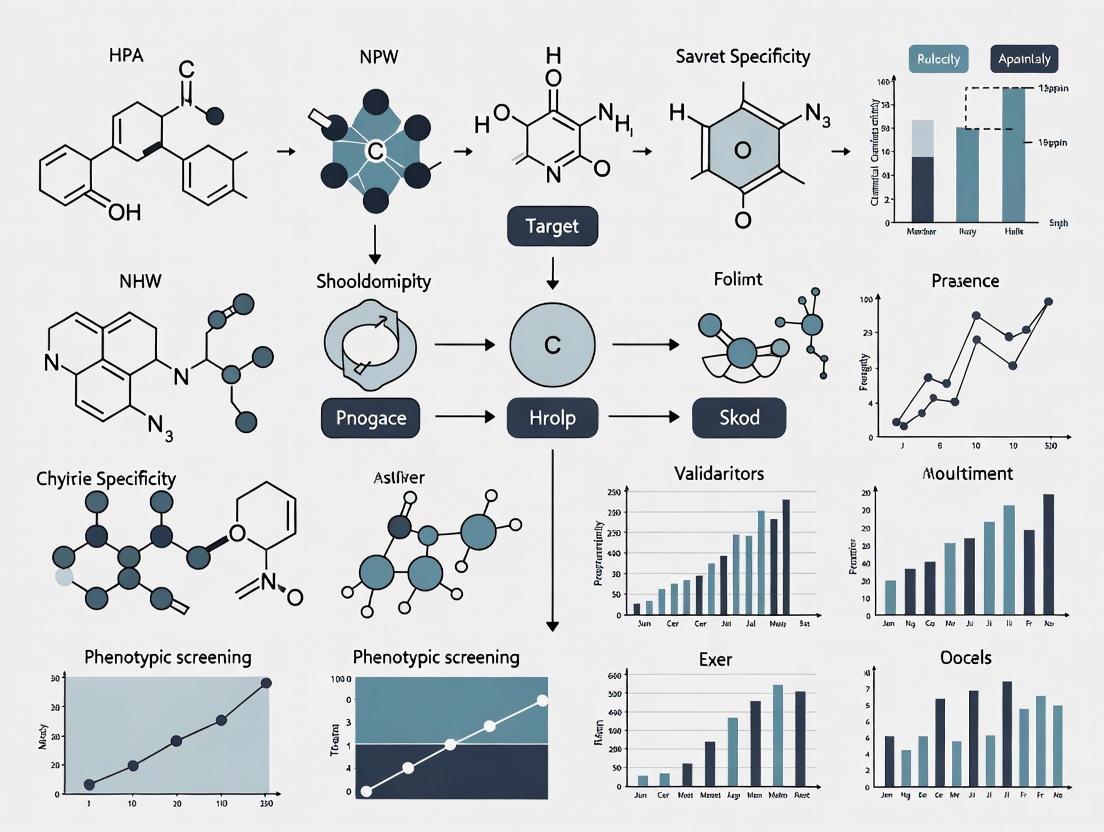

A robust deconvolution workflow often combines multiple computational and experimental approaches. The following diagram illustrates an integrated pipeline for target deconvolution from phenotypic screening:

Diagram Title: Integrated Deconvolution Workflow

This integrated approach was exemplified in a study investigating p53 pathway activators [19]. Researchers began with UNBS5162, identified through a phenotypic screen for p53-transcriptional activity. They then employed a protein-protein interaction knowledge graph (PPIKG) analysis that narrowed candidate proteins from 1088 to 35 [19]. Subsequent molecular docking prioritized USP7 as a likely direct target, which was then confirmed through biological assays [19]. This combination of computational prediction and experimental validation streamlined the laborious process of reverse target identification through phenotype screening.

Solvent Proteome Profiling Protocol

Solvent-induced proteome profiling (SPP) has emerged as a powerful label-free method for deconvoluting drug targets. The experimental workflow involves:

Sample Preparation: Live cells or cell lysates are treated with the compound of interest alongside vehicle controls. For malaria research, Plasmodium falciparum cultures can be treated with antimalarial compounds like pyrimethamine, atovaquone, or cipargamin [18].

Solvent Denaturation: Treated samples are exposed to increasing concentrations of a denaturing solvent (e.g., DMSO, guanidine-HCl) to generate protein denaturation curves [18].

Proteome Analysis: Denatured samples are digested with trypsin and analyzed by high-resolution mass spectrometry. The Orbitrap Astral mass spectrometer workflow provides unprecedented proteome coverage with high selectivity and sensitivity [18].

Data Analysis: Protein abundance is measured across denaturation conditions. Ligand-bound proteins exhibit shifted denaturation curves (increased stability) compared to unbound proteins. Investigating protein levels at individual solvent percentages preserves specific stability changes that might be masked in pooled analyses [18].

Live-Cell SPP: A novel adaptation involves treating intact living cells with compounds before lysis and denaturation. This approach potentially detects activation-dependent or native interactions beyond what lysate-based methods can identify [18].

One-Pot Mixed-Drug SPP: Multiple drugs can be evaluated within a single lysate and experimental setup, simplifying workflow and incorporating positive controls to affirm experimental performance [18].

Impact on Lead Optimization

Enhancing Target Specificity

Deconvolution directly informs lead optimization by clarifying structure-activity relationships (SAR) based on precise target knowledge. Once molecular targets are identified, medicinal chemistry efforts can focus on enhancing compound specificity and reducing off-target interactions [14]. For example, the discovery that thalidomide analogs (lenalidomide and pomalidomide) bind cereblon and modulate its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity enabled rational optimization to reduce sedative and neuropathic side effects while maintaining therapeutic efficacy [1].

The integration of AI and machine learning has accelerated this optimization process. Modern AI platforms can generate novel compounds with optimized target specificity and pharmacological properties. For instance, Insilico Medicine's Chemistry42 module applies deep learning, including generative adversarial networks (GANs) and reinforcement learning, to design novel drug-like molecules optimized for binding affinity, metabolic stability, and bioavailability [21]. This approach represents a paradigm shift from traditional iterative optimization to predictive in silico design.

Multi-Target Profiling

Deconvolution often reveals that promising phenotypic hits act through polypharmacology—simultaneous modulation of multiple targets [19]. This understanding enables rational optimization of multi-target profiles rather than serendipitous off-target effects. In the p53 pathway example, researchers noted that traditional target-based screening focusing on individual p53 regulators (MDM2, MDMX, USP7) might miss beneficial multi-target compounds [19]. Phenotypic screening with integrated deconvolution captures these potentially advantageous multi-target activities while enabling researchers to understand and optimize the resulting profile.

Advanced computational approaches now facilitate this multi-target optimization. Iambic Therapeutics' AI platform integrates three specialized systems—Magnet for molecular generation, NeuralPLexer for predicting ligand-induced conformational changes, and Enchant for predicting human pharmacokinetics—creating an iterative, model-driven workflow where multi-target candidates are designed, structurally evaluated, and clinically prioritized entirely in silico before synthesis [17].

Impact on Safety Profiling

Early Off-Target Identification

Deconvolution technologies excel at identifying off-target interactions that may underlie adverse effects, enabling early safety assessment during lead optimization. Affinity-based pulldown combined with mass spectrometry can systematically identify off-target binding across the proteome [14]. Similarly, solvent proteome profiling detects off-target engagement through stability shifts across thousands of proteins simultaneously [18] [14].

The ability to comprehensively profile compound-protein interactions allows researchers to identify potentially problematic off-target activities before extensive preclinical development. For example, profiling against known antitargets (e.g., hERG for cardiac safety, CYP450s for metabolic interactions) can flag potential safety issues when these proteins appear in deconvolution results [14]. This early warning system enables proactive mitigation through chemical modification before significant resources are invested in problematic compounds.

Mechanistic Understanding of Toxicity

Beyond simple off-target identification, deconvolution provides mechanistic insights into observed toxicities by linking phenotypic responses to specific molecular interactions. The comprehensive profiling enabled by modern deconvolution approaches helps distinguish mechanism-based toxicity from off-target effects [14]. This distinction is crucial for determining whether a toxicity can be engineered out while maintaining efficacy.

Knowledge graph approaches further enhance safety profiling by contextualizing targets within broader biological pathways [19] [21]. By understanding how both primary and off-targets connect to adverse outcome pathways, researchers can better predict and interpret safety signals. Recursion OS exemplifies this approach, using its knowledge graph tool to evaluate promising signals through multiple biological lenses including global trend scores, protein pockets and structure, competitive landscape, and clinical trials [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Deconvolution Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Immobilization Resins [14] | Solid support for affinity purification | Affinity-based chemoproteomics, target enrichment |

| Bifunctional Probes [14] | Covalent labeling of protein targets | Activity-based protein profiling, cysteine reactivity screening |

| Photoaffinity Probes [14] | Photo-induced crosslinking to targets | Studying membrane proteins, transient interactions |

| Solvent Denaturation Kits [18] | Protein stability shift assays | Solvent proteome profiling, thermal shift assays |

| Selective Compound Libraries [15] [20] | Phenotypic screening with mechanistic insights | Target identification through selective chemical probes |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards [18] | Quantitative proteomics | Protein identification and quantification in pull-down assays |

| Knowledge Graph Databases [19] | Biological network analysis | Target hypothesis generation, pathway contextualization |

Comparative Analysis of Deconvolution Platforms

Technology Performance Metrics

Different deconvolution approaches offer complementary strengths and limitations. The table below compares key performance metrics across major technologies:

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Deconvolution Technologies

| Technology | Target Coverage | Sensitivity | Throughput | Label Required | Native Environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity-Based Pull-down [14] | High (proteome-wide) | Moderate | Moderate | Yes (immobilization) | No (lysate-based) |

| Activity-Based Profiling [14] | Moderate (enzyme classes) | High | High | Yes (reactive tags) | Yes (live cells possible) |

| Photoaffinity Labeling [14] | High (proteome-wide) | High | Moderate | Yes (photo-probes) | Yes (live cells possible) |

| Solvent Proteome Profiling [18] [14] | High (proteome-wide) | Moderate-High | Moderate | No | Yes (live cells possible) |

| Knowledge Graph Prediction [19] | Theoretical (database-dependent) | Variable | High | No | N/A |

| Selective Compound Screening [15] [20] | Limited (to available probes) | High | High | No | Yes |

Application-Specific Recommendations

Choosing the appropriate deconvolution strategy depends on specific research contexts:

For Novel Target Identification: Integrated approaches combining knowledge graph prediction with experimental validation (e.g., PPIKG with molecular docking) provide powerful starting points [19]. This strategy efficiently narrows candidate space before resource-intensive experimental work.

For Membrane Protein Targets: Photoaffinity labeling excels at identifying interactions with integral membrane proteins, which are often challenging for other methods [14]. The ability to capture transient interactions in native membrane environments is particularly valuable for this target class.

For Native Interaction Mapping: Solvent proteome profiling and related label-free methods preserve physiological context, making them ideal for detecting interactions that might be disrupted by compound modification or cell lysis [18] [14]. Live-cell SPP further enhances this native context preservation.

For Rapid Mechanistic Insights: Selective compound libraries screened in phenotypic assays provide immediate mechanistic direction when activity is observed [15] [20]. This approach is particularly valuable when multiple hits emerge from initial screens and require prioritization.

The field of target deconvolution continues to evolve rapidly, driven by advances in artificial intelligence, proteomics, and computational biology. Integration of multi-omics data—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—provides a comprehensive framework for linking observed phenotypic outcomes to discrete molecular pathways [1]. AI-powered platforms are increasingly capable of representing biology holistically, moving beyond reductionist single-target models to systems-level understanding [21].

Future developments will likely focus on enhancing the throughput, sensitivity, and accessibility of deconvolution technologies. Methods like one-pot mixed-drug solvent proteome profiling already demonstrate progress toward simplified workflows and increased throughput [18]. Similarly, the automated selection of highly selective ligands from expanding bioactivity databases will improve the coverage and utility of chemogenomic screening sets [20].

In conclusion, target deconvolution has revolutionized the transition from phenotypic screening to lead optimization and safety assessment. By illuminating the molecular mechanisms underlying phenotypic effects, deconvolution enables rational optimization of lead compounds while proactively identifying potential safety concerns. As technologies continue to advance, integrated computational and experimental deconvolution strategies will play an increasingly central role in accelerating the development of safer, more effective therapeutics.

In the field of phenotypic drug discovery, target deconvolution serves as a critical bridge between observing a compound's therapeutic effect and understanding its precise molecular mechanism of action [22]. This process involves working backward from a drug that demonstrates efficacy in a complex biological system to identify the specific protein or nucleic acid it engages [22]. Historically, this approach has been instrumental in revealing unprecedented therapeutic targets and mechanisms, expanding the conventional boundaries of "druggable" target space [8]. This guide examines landmark cases where deconvolution strategies successfully uncovered novel mechanisms of action, comparing the experimental methodologies and their outcomes to inform current target specificity validation for phenotypic screening hits.

Key Success Stories in Mechanism Deconvolution

Table 1: Historical Cases of Novel Mechanism Discovery through Deconvolution

| Drug/Compound | Therapeutic Area | Initial Phenotypic Observation | Deconvoluted Target | Novel Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lenalidomide [8] | Multiple myeloma, Blood cancers | Effective treatment for leprosy; modulated cytokines, inhibited angiogenesis [8] | Cereblon (E3 ubiquitin ligase) [8] | Binds to Cereblon and redirects its substrate selectivity to promote degradation of transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3 [8] |

| Risdiplam/Branaplam [8] | Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) | Small molecules that modified SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing in phenotypic screens [8] | SMN2 pre-mRNA / U1 snRNP complex [8] | Stabilizes the interaction between U1 snRNP and SMN2 pre-mRNA to promote inclusion of exon 7 and production of functional SMN protein [8] |

| Ivacaftor/Tezacaftor/Elexacaftor [8] | Cystic fibrosis (CF) | Improved CFTR channel function and trafficking in cell lines expressing disease-associated variants [8] | CFTR protein (various mutations) [8] | Ivacaftor potentiates CFTR channel gating; correctors (tezacaftor, elexacaftor) enhance CFTR folding and plasma membrane insertion [8] |

| Daclatasvir [8] | Hepatitis C virus (HCV) | Inhibited HCV replication in a replicon phenotypic screen [8] | HCV NS5A protein [8] | Modulates NS5A, a viral protein with no known enzymatic activity that is essential for HCV replication [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Target Deconvolution

Affinity Chromatography

Purpose: To physically isolate drug-target complexes from biological systems for subsequent identification [22].

Detailed Methodology:

- Step 1: Immobilize the drug molecule of interest onto a solid chromatography resin via a chemical linker.

- Step 2: Prepare a cell lysate from disease-relevant models and pass it through the drug-conjugated resin.

- Step 3: Wash the resin extensively with buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Step 4: Elute specifically bound proteins using either free competitor drug (specific elution) or denaturing conditions (non-specific elution).

- Step 5: Identify the eluted proteins through mass spectrometry analysis.

- Step 6: Validate putative targets through orthogonal methods such as siRNA knockdown or cellular thermal shift assays.

Expression Cloning

Purpose: To identify drug targets by screening cDNA libraries for clones that confer drug resistance or sensitivity [22].

Detailed Methodology:

- Step 1: Construct a comprehensive cDNA expression library in suitable mammalian vectors.

- Step 2: Transfect the library into recipient cells that are sensitive to the drug's effects.

- Step 3: Apply selective pressure with the drug compound to identify transfected clones that survive due to cDNA expression.

- Step 4: Isolate and sequence the plasmid DNA from resistant clones to identify the cDNA conferring resistance.

- Step 5: Validate the identified target by demonstrating direct drug-target binding and recapitulation of the phenotypic effect.

siRNA-Based Validation

Purpose: To functionally confirm putative targets by mimicking the drug's pharmacological effect through genetic inhibition [22].

Detailed Methodology:

- Step 1: Design and obtain siRNA oligonucleotides targeting the mRNA of the putative drug target.

- Step 2: Transfect disease-relevant cells with target-specific siRNAs alongside appropriate control siRNAs.

- Step 3: Quantify mRNA knockdown efficiency 48-72 hours post-transfection using qRT-PCR.

- Step 4: Assess protein level reduction via western blotting or immunocytochemistry.

- Step 5: Measure phenotypic outcomes analogous to those observed with drug treatment.

- Step 6: Compare the phenotypic effects of siRNA-mediated target knockdown with those of the drug compound.

Visualizing the Deconvolution Workflow for Phenotypic Hits

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Target Deconvolution Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Deconvolution |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Matrices | NHS-activated Sepharose, Aminolink Coupling Resin | Immobilize drug molecules for pull-down experiments to capture binding proteins from complex lysates [22] |

| cDNA Libraries | Mammalian expression cDNA libraries, ORFeome collections | Enable expression cloning to identify targets that confer drug resistance when overexpressed [22] |

| siRNA Libraries | Genome-wide siRNA sets, Target-specific siRNA pools | Functionally validate putative targets by mimicking drug effects through genetic knockdown [22] |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS systems, MALDI-TOF | Identify proteins isolated through affinity purification by precise mass analysis and database searching [22] |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | iPSC-derived cells, Primary cell cultures, Disease-relevant cell lines | Provide physiologically relevant models for phenotypic screening and target validation [8] [23] |

Implications for Phenotypic Screening Hit Triage

The historical successes illustrated herein demonstrate that deconvolution of phenotypic screening hits can reveal unprecedented therapeutic mechanisms that would be difficult to discover through target-based approaches [8]. When triaging phenotypic hits, researchers should consider that:

- Compounds with unknown mechanisms may represent valuable opportunities to explore novel biology rather than liabilities [24]

- Polypharmacology (engagement of multiple targets) may contribute to efficacy in complex diseases, challenging the traditional single-target paradigm [8]

- Structure-based hit triage may be counterproductive, as novel mechanisms often emerge from compounds with atypical structural features [24]

- Successful hit triage and validation is enabled by three types of biological knowledge: known mechanisms, disease biology, and safety considerations [24]

Historical examination of successful deconvolution campaigns reveals a consistent pattern: therapeutic breakthroughs often emerge from pursuing compelling phenotypic effects without predetermined target biases. The experimental methodologies detailed here—affinity chromatography, expression cloning, and siRNA validation—provide robust frameworks for contemporary researchers navigating the transition from phenotypic observation to mechanistic understanding. As phenotypic screening experiences a resurgence in drug discovery, these deconvolution strategies remain essential for unlocking novel biology and delivering first-in-class therapeutics with unprecedented mechanisms of action.

A Toolkit for Target Identification: Experimental and Computational Deconvolution Strategies

In phenotypic drug discovery, compounds are first identified based on their ability to induce a desired therapeutic effect in cells or whole organisms, without prior knowledge of their specific molecular targets [25] [14]. While this approach successfully identifies bioactive compounds in physiologically relevant contexts, it creates a critical bottleneck: determining the precise protein target(s) responsible for the observed phenotype [26]. This process, known as target deconvolution, is essential for understanding a compound's mechanism of action (MoA), optimizing its properties, and anticipating potential side effects [27].

Among the various experimental strategies for target deconvolution, affinity-based chemoproteomics has established itself as a foundational "workhorse" methodology [14]. This approach directly isolates protein targets from complex biological systems using immobilized small molecules as bait, providing a robust and versatile platform for target identification [28] [27]. This guide objectively compares affinity-based chemoproteomics with other emerging target deconvolution technologies, providing researchers with the experimental and strategic context needed to validate target specificity for phenotypic screening hits.

Fundamental Principles of Affinity-Based Chemoproteomics

Core Methodology and Mechanism

Affinity-based chemoproteomics relies on a straightforward yet powerful principle: a small molecule of interest is converted into a chemical probe by attaching a handle that allows it to be immobilized on a solid support [27]. When this immobilized "bait" is exposed to a biological sample such as a cell lysate, it selectively captures its protein binding partners. These proteins can then be purified, identified, and characterized [28].

The core workflow involves several critical steps, visualized below.

Key Research Reagents and Experimental Components

Successful implementation of affinity-based chemoproteomics requires carefully selected reagents and materials. The table below details essential components of the experimental toolkit.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Affinity-Based Chemoproteomics

| Reagent/Material | Function & Purpose | Common Variants & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Tag | Enables detection and purification of target proteins [28]. | Biotin, fluorescent tags (FITC), His-tags [28]. |

| Solid Support | Serves as an insoluble matrix for probe immobilization [27]. | Agarose beads, magnetic beads [27]. |

| Linker/Spacer | Connects the small molecule to the tag/support; can influence binding efficiency [28]. | Polyethylene glycol (PEG), alkyl chains [27]. |

| Cell Lysate | Source of native proteins representing the potential target landscape [29]. | Crude lysates, fractionated lysates, tissue homogenates [29]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | The primary tool for identifying proteins isolated by affinity purification [25]. | LC-MS/MS, Data Independent Acquisition (DIA) [29]. |

Comparative Analysis of Target Deconvolution Methodologies

While affinity-based chemoproteomics is a cornerstone technique, several other powerful methods have been developed. The choice of method depends on the specific research question, the properties of the compound, and the desired output.

Method Classification and Workflow Comparison

Target deconvolution strategies can be broadly categorized into probe-based methods, which require chemical modification of the small molecule, and label-free methods, which do not [26]. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these strategic categories and their specific techniques.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Key Techniques

The table below provides a structured, data-driven comparison of the major target deconvolution methods, highlighting the relative strengths and limitations of each.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Major Target Deconvolution Techniques

| Method | Key Principle | Throughput | Target Modification Required? | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity-Based Pull-Down [27] | Immobilized probe captures binding proteins from lysate. | High | Yes | Broad applicability; works for many target classes [14]. | Requires synthesis of functional probe; potential for disrupted binding [28]. |

| Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) [28] | Reactive probe covalently labels active-site residues of enzyme families. | Medium | Yes | Exceptional for enzyme activity profiling; high specificity [28]. | Limited to proteins with reactive nucleophiles (e.g., cysteines) in active sites [28]. |

| Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) [14] | Probe with photo-reactive group forms covalent bond with target upon UV exposure. | Medium | Yes | Captures transient/weak interactions; suitable for membrane proteins [14]. | Complex probe design; potential for non-specific cross-linking [14]. |

| Thermal Proteome Profiling (TPP) [30] | Ligand binding increases protein thermal stability, measured en masse by MS. | Medium | No | True label-free, proteome-wide screening; detects indirect stabilization [30] [29]. | Can miss targets that don't stabilize with binding; lower abundance target challenge [29]. |

| DARTS [27] | Ligand binding protects against proteolytic degradation. | High | No | Simple, low-cost, and label-free protocol [27]. | Can yield false positives; less proteome-wide than MS-based methods [27]. |

| LiP-Quant [29] | Machine learning analyzes ligand-induced proteolytic pattern changes across doses. | Medium | No | Identifies binding sites; provides affinity estimates (EC50) [29]. | Computational complexity; performance can vary with target abundance [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Core Protocol: Affinity-Based Pull-Down with On-Bead Matrix

This protocol is a standard workhorse procedure for isolating target proteins [27].

- Probe Design and Synthesis: A linker (e.g., PEG) is covalently attached to the small molecule hit at a site known to be tolerant to modification, preserving its biological activity. This linker is then used to immobilize the molecule on a solid support, such as agarose beads [27].

- Preparation of Cell Lysate: Grow cells of interest and lyse them using a non-denaturing lysis buffer to preserve native protein structures and interactions. Clarify the lysate by centrifugation to remove insoluble debris.

- Affinity Capture: Incubate the prepared cell lysate with the small molecule-conjugated beads. A control should be run in parallel using beads conjugated with an inactive analog or just the linker. Incubation is typically performed for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation to allow binding to reach equilibrium.

- Washing: Pellet the beads and carefully remove the supernatant. Wash the beads multiple times with ice-cold lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Stringency can be adjusted by adding mild detergents or salt to the wash buffers.

- Elution: Elute specifically bound proteins from the beads. This can be achieved by:

- Competitive Elution: Incubating with a high concentration of the free, non-modified small molecule.

- Denaturing Elution: Using a Laemmli buffer for subsequent SDS-PAGE analysis.

- Target Identification:

- Separate eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE and visualize by silver staining. Bands present in the experimental but not the control pull-down are excised, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

- Alternatively, proteins can be digested directly on-bead and the resulting peptides analyzed by LC-MS/MS for identification.

Advanced Protocol: LiP-Quant for Label-Free Binding Site Mapping

For comparison, LiP-Quant is a more recent, label-free method that can also map binding sites [29].

- Sample Treatment: Divide a native cell lysate into aliquots. Treat each with a different concentration of the small molecule (a dose-response series, e.g., from nM to µM), including a vehicle-only control.

- Limited Proteolysis: Subject each treated lysate aliquot to a brief, controlled digestion with a non-specific protease (e.g., proteinase K). The key is to use a protease concentration and time that results in partial, rather than complete, digestion.

- Proteome Digestion and Peptide Preparation: Quench the protease activity. Then, denature the sample and perform a complete digestion with a sequence-specific protease like trypsin.

- Mass Spectrometric Analysis: Analyze the resulting complex peptide mixtures using Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry, which provides a comprehensive and quantitative record of all detectable peptides.

- Data Analysis and Machine Learning: Process the MS data to quantify all peptide fragments. Use a machine learning model (as described in the LiP-Quant method) to identify peptides whose abundance changes in a dose-dependent manner upon compound treatment. These peptides, which often reside in or near the compound binding site, are used to identify the protein target and approximate the binding region [29].

Affinity-based chemoproteomics remains an indispensable and robust "workhorse" for isolating the protein targets of phenotypic screening hits. Its direct mechanism, broad applicability across diverse target classes, and well-established protocols make it a first-choice strategy for many target deconvolution campaigns [28] [27] [14].

However, the evolving landscape of chemoproteomics demonstrates that no single method is universally superior. The strategic integration of multiple approaches is often the most powerful path to validation. For instance, a target first isolated through a classic affinity-based pull-down can be independently validated using a label-free method like CETSA or LiP-Quant [29]. Conversely, hits from a phenotypic screen can be screened initially with a label-free method to prioritize compounds with well-defined targets before investing in the synthesis of complex affinity probes.

The future of target deconvolution lies in leveraging the complementary strengths of these technologies. Affinity-based methods provide a direct physical isolation of targets, while newer label-free strategies offer insights into binding thermodynamics, binding sites, and functional consequences in a more native context. By understanding the comparative performance, data output, and experimental requirements of each method, researchers can design more efficient and conclusive workflows to accelerate the journey from phenotypic hit to validated drug candidate.

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) for Targeting Enzyme Families

Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) has emerged as a powerful chemical proteomic approach to directly interrogate protein function and validate target specificity, particularly for hits originating from phenotypic screens [31] [32]. Unlike conventional proteomic methods that measure protein abundance, ABPP uses small-molecule chemical probes to report on the functional state of enzymes within complex biological systems [33] [34]. This capability is particularly valuable in phenotypic screening research, where identifying the specific molecular targets responsible for observed phenotypes remains a significant challenge [32] [14]. By enabling researchers to directly monitor enzyme activities and map small molecule-protein interactions in native biological environments, ABPP provides a robust methodology for target deconvolution and specificity validation across entire enzyme families [35] [34].

The fundamental principle of ABPP involves the use of activity-based probes (ABPs) that covalently bind to the active sites of enzymes in an activity-dependent manner [36] [33]. These probes typically contain three key elements: a reactive group (or "warhead") that targets specific enzyme families, a linker region, and a reporter tag for detection and enrichment [31] [32]. When integrated into phenotypic screening workflows, ABPP can directly identify which enzyme activities are modulated by screening hits, bridging the gap between observed phenotypic effects and their underlying molecular mechanisms [37] [14].

ABPP Probe Design and Enzyme Family Targeting

Core Components of Activity-Based Probes

The specificity and effectiveness of ABPP rely on careful probe design, with each component serving a distinct function:

Reactive Group ("Warhead"): This element determines enzyme family specificity by covalently binding to active site residues. For example, fluorophosphonate (FP) warheads broadly target serine hydrolases, while epoxides and vinyl sulfones target cysteine proteases [36] [31] [34]. Warheads can be designed for broad profiling of entire enzyme classes or for selective targeting of specific enzymes [32].

Linker Region: Typically composed of alkyl or polyethylene glycol (PEG) spacers, linkers connect the reactive group to the reporter tag while minimizing steric interference with target binding [31]. Some advanced probes incorporate cleavable linkers to facilitate efficient enrichment of labeled proteins [31] [32].

Reporter Tag: This component enables detection, isolation, and identification of probe-labeled proteins. Common tags include fluorophores for visualization, biotin for affinity enrichment, and alkynes/azides for subsequent bioorthogonal conjugation via click chemistry [36] [31].

Targeting Specific Enzyme Families

ABPP probes can be tailored to target mechanistically related enzyme families by exploiting conserved catalytic features:

Table 1: ABPP Probes for Major Enzyme Families

| Enzyme Family | Probe Reactive Group | Key Residues Targeted | Applications in Target Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serine Hydrolases | Fluorophosphonates (FP) [36] [34] | Catalytic serine [36] | Target deconvolution for endocannabinoid pathway inhibitors [34] |

| Cysteine Proteases | Epoxides, Vinyl Sulfones [31] [34] | Catalytic cysteine [34] | Profiling proteasome and cathepsin activities [34] |

| Protein Kinases | Acyl phosphates [31] | ATP-binding pocket residues | Kinase inhibitor specificity profiling [35] |

| Phosphatases | Tyrosine phosphatase probes [36] | Catalytic cysteine, Active site histidine | Cellular signaling pathway analysis [36] |

The development of broad-spectrum probes enables parallel profiling of numerous enzymes within a class, making ABPP ideal for evaluating the proteome-wide selectivity of candidate compounds [32]. Conversely, tailor-made probes with narrow specificity allow precise investigation of individual enzymes in complex biological systems [32].

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Core ABPP Workflow

The standard ABPP workflow involves multiple critical steps from probe design to target identification:

Diagram 1: Core ABPP workflow for target identification.

The process begins with the design and synthesis of appropriate activity-based probes tailored to the enzyme family of interest [31]. For in vivo applications, probes with minimal perturbation, such as those containing alkyne or azide tags, are preferred as they readily penetrate cells [36]. Following incubation with biological samples (either live cells, tissue homogenates, or cell lysates), the labeled proteins can be detected through different pathways depending on the reporter tag utilized [31].

For probes with fluorescent tags, direct SDS-PAGE separation and fluorescence scanning enable rapid visualization of labeled proteins [31]. For probes with bioorthogonal handles (e.g., alkynes), a Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (Click reaction) is performed to attach fluorescent dyes or biotin for subsequent detection or enrichment [36] [31]. Biotinylated proteins can be isolated using avidin affinity purification and identified via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [36] [31].

Competitive ABPP for Target Engagement Studies

Competitive ABPP represents a powerful adaptation for validating target specificity of phenotypic screening hits:

Diagram 2: Competitive ABPP workflow for target engagement.

In this approach, biological samples are pre-treated with a test compound of interest, followed by incubation with a broad-spectrum ABPP probe [32] [35]. The extent of probe labeling is then quantified. Successful target engagement by the test compound results in reduced probe signal at specific protein bands, indicating direct binding and inhibition [32] [35]. This method has been successfully applied to identify and optimize selective inhibitors for various enzyme families, including serine hydrolases and deubiquitinases [35] [34].

A notable application of competitive ABPP in antibiotic discovery identified 10-F05, a covalent fragment that targets FabH and MiaA in ESKAPE pathogens [37]. The competitive ABPP approach confirmed direct engagement of these targets and helped elucidate the compound's mechanism of growth inhibition and virulence attenuation [37].

Comparative Performance Data of ABPP Applications

ABPP Across Biological Systems

ABPP has been successfully implemented in diverse biological contexts, from microbial systems to human cell lines:

Table 2: ABPP Applications Across Biological Systems

| Biological System | Enzyme Families Profiled | Key Experimental Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfolobus acidocaldarius (Archaea) | Serine hydrolases | Successful in vivo labeling at 75-80°C and pH 2-3 using FP≡ and NP≡ probes; Identified paraoxon-sensitive esterases (~38 kDa) | [36] |

| Human cancer cell lines | Serine hydrolases, Cysteine proteases | Discovered selective inhibitors for enzymes lacking known substrates (chemistry-first functional annotation) | [35] [34] |

| ESKAPE pathogens | Cysteine-containing enzymes | Identified 10-F05 fragment targeting FabH and MiaA; Confirmed slow resistance development | [37] |

| Primary immune cells | Kinases, Phosphatases | Mapped immune signaling pathways; Identified novel regulatory nodes | [35] |

Comparison of Advanced ABPP Platforms

Recent technological advances have significantly expanded ABPP capabilities:

Table 3: Advanced ABPP Platforms and Applications

| ABPP Platform | Key Features | Applications in Target Validation | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| isoTOP-ABPP | Quantifies active sites proteome-wide; Uses cleavable linkers | Identifies functional residues; Maps ligandable hotspots | Requires specialized isotopic tags; Complex data analysis |

| FluoPol-ABPP | High-throughput screening compatible; Fluorescence polarization readout | Discovery of substrate-free enzyme inhibitors; Rapid inhibitor screening | Limited to soluble enzymes; Signal interference possible |

| qNIRF-ABPP | Enables in vivo imaging; Near-infrared fluorescence | Non-invasive target engagement studies in live animals; Tissue penetration | Limited resolution for subcellular localization |

| Photoaffinity-ABPP | Captures transient interactions; Photoreactive groups | Identifies shallow binding sites; Membrane protein targets | Potential non-specific labeling; UV activation required |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of ABPP requires carefully selected reagents and methodologies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ABPP

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in ABPP Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Reactive Groups | Fluorophosphonates (serine hydrolases) [36] [34], Iodoacetamide (cysteine) [35] [34], Sulfonate esters (tyrosine) [35] | Covalently binds active site residues of target enzyme families |

| Reporter Tags | Biotin [31], Tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) [31], Alkyne (for click chemistry) [36] [31] | Enables detection, visualization, and affinity purification of labeled proteins |

| Click Chemistry Reagents | Cu(I) catalysts, Azide-fluorophore conjugates [36] [31] | Links reporter tags to probe-labeled proteins post-labeling |

| Enrichment Materials | Streptavidin/NeutrAvidin beads [31], Antibody resins | Isolates biotin-labeled proteins from complex mixtures |

| MS-Grade Reagents | Trypsin/Lys-C, Stable isotope labels (TMT, iTRAQ) [35] | Digests proteins and enables quantitative proteomic analysis |

ABPP in Phenotypic Screening and Target Deconvolution

The integration of ABPP into phenotypic drug discovery pipelines has revolutionized target deconvolution efforts. By directly reporting on protein activities rather than mere abundance, ABPP can identify which specific enzymes are functionally modulated by phenotypic screening hits [32] [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for covalent inhibitors, where ABPP provides robust data on target engagement and proteome-wide selectivity [35] [34].

A key advantage of ABPP in phenotypic screening is its ability to identify off-target effects early in the discovery process [32] [14]. By screening compounds against broad enzyme families, researchers can simultaneously assess both efficacy and selectivity, guiding medicinal chemistry optimization toward compounds with improved therapeutic indices [35]. Furthermore, ABPP has enabled a "chemistry-first" approach to protein function annotation, where selective inhibitors are discovered for uncharacterized enzymes, and these chemical tools are then used to elucidate biological functions [35] [34].

The application of ABPP has expanded beyond enzyme active sites to include non-catalytic ligandable pockets [35] [34]. Through the use of cysteine-directed and other residue-specific probes, researchers can now map small-molecule interactions across diverse protein classes, including those historically considered "undruggable" [35]. This expansion has led to the discovery of covalent ligands that modulate protein functions through allosteric mechanisms, protein-protein interaction disruption, and protein stabilization [35] [34].

Activity-based protein profiling represents a versatile and powerful platform for targeting enzyme families and validating target specificity in phenotypic screening research. Through its unique ability to directly report on protein function in native biological systems, ABPP bridges critical gaps between phenotypic observations and molecular mechanisms. The continuous development of novel probe chemistries, advanced screening platforms, and quantitative proteomic methods continues to expand the scope and impact of ABPP in drug discovery. As phenotypic screening regains prominence in pharmaceutical research, ABPP stands as an essential technology for target deconvolution, selectivity validation, and chemical tool development across diverse enzyme families.

Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) for Capturing Transient Interactions

Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) has emerged as an indispensable chemical biology technique for identifying molecular targets and mapping binding sites, particularly for characterizing the mode of action of hits from phenotypic screens where the direct protein target is often unknown [38] [39]. By enabling the covalent capture of transient, non-covalent interactions upon photoirradiation, PAL facilitates the identification and validation of target specificity, bridging the gap between observed phenotypic effects and underlying molecular mechanisms [40] [41] [42].

Core Principles and Photoreactive Groups

PAL employs a chemical probe that covalently binds its target in response to activation by light. This is achieved by incorporating a photoreactive group into a reversibly binding probe compound [38]. The ideal probe must balance several characteristics: stability in the dark, high similarity to the parent compound, minimal steric interference, activation at wavelengths causing minimal biological damage, and the formation of a stable covalent adduct [38].

The design of a typical photoaffinity probe integrates three key functionalities:

- Affinity/Specificity Unit: The small molecule of interest responsible for reversible binding to target proteins.

- Photoreactive Moiety: A group (e.g., diazirine) that allows permanent attachment to targets upon photoactivation.

- Identification/Reporter Tag: A tag (e.g., biotin, a fluorescent dye, or alkyne for subsequent "click" chemistry) for the detection and isolation of probe-protein adducts [38] [43].

Linker length between these functionalities is critical; too short a linker can lead to self-crosslinking, while too long a linker may inefficiently capture the target protein [38].

Comparison of Primary Photoreactive Groups

Three main photoreactive groups dominate PAL applications, each with distinct photochemical properties and trade-offs [38] [40] [41].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Photoreactive Groups Used in PAL

| Photoreactive Group | Reactive Intermediate | Activation Wavelength | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aryl Azide [38] [40] [41] | Nitrene | 254–400 nm | Easily synthesized, commercially available [38]. | Shorter wavelengths can damage biomolecules; nitrene can rearrange into inactive side-products, lowering yield [38] [40]. |

| Benzophenone [38] [41] | Diradical | 350–365 nm | Activation by longer, less damaging wavelengths; can be reactivated if initial crosslinking fails [38] [41]. | Longer irradiation times often needed, increasing non-specific labeling; bulky group may sterically hinder binding [38]. |

| Diazirine [38] [40] [42] | Carbene | ~350 nm | Small size minimizes steric interference; highly reactive carbene intermediate reacts rapidly with C-H bonds [38] [40]. | The carbene has a very short half-life (nanoseconds) [41]. |

Experimental Workflow for Target Identification

The application of PAL for target identification, especially for phenotypic screening hits, follows a multi-step workflow that integrates chemistry, cell biology, and proteomics. The following diagram illustrates the key stages of a live-cell PAL experiment, from probe design to target identification.

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for target identification using live-cell Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) combined with quantitative chemical proteomics. The process begins with a bioactive compound from a phenotypic screen and culminates in the identification of its direct protein targets and specific binding sites.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

1. Photoaffinity Probe Design and Validation The first critical step involves creating a PAL-active derivative of the phenotypic hit. The "minimalist tag" incorporating both a diazirine and an alkyne is often favored due to its small size, which minimizes disruption of the parent molecule's bioactivity [38] [43]. The probe's biological activity must be rigorously benchmarked against the parent molecule using relevant phenotypic or biochemical assays to ensure it recapitulates the original effect [42] [43]. For example, in the development of a probe for the CFTR corrector ARN23765, one analogue (PAP1) almost completely retained sub-nanomolar potency, while another (PAP2) showed markedly reduced efficacy, highlighting the importance of strategic probe design and validation [42].

2. Live-Cell Treatment and Photoirradiation To capture interactions in a native physiological context, live cells are treated with the photoaffinity probe. A competition condition, where cells are co-treated with the probe and a large excess of the parent, unmodified compound, is essential to distinguish specific from non-specific labeling [38] [43]. After incubation, cells are irradiated with UV light (typically ~350 nm for diazirines) to activate the photoreactive group. A high-power lamp can reduce irradiation time, and cooling the sample helps maintain cell viability [43].

3. Sample Processing, Enrichment, and Proteomic Analysis Following irradiation and cell lysis, the "click" chemistry reaction (CuAAC) is performed to append an enrichment handle (e.g., an acid-cleavable, isotopically-coded biotin-azide) to the alkyne-bearing, crosslinked proteins [38] [43]. Biotinylated proteins are then enriched using streptavidin-coated beads. After extensive washing, two fractions are typically collected for LC-MS/MS analysis:

- Trypsin Digest Fraction: Beads are treated with trypsin to release non-conjugated peptides, which are analyzed to identify the enriched proteins (the "interactome") [43].

- Acid Cleavage Fraction: A second fraction is treated with acid to cleave the handle and release the small molecule-conjugated peptides, allowing for precise mapping of the binding site on the target protein [43]. Quantitative proteomics (e.g., label-free or SILAC) comparing the probe-only sample to the competition control reveals specifically bound proteins.

Research Reagent Solutions for PAL Experiments

Success in PAL experiments relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions essential for implementing the described workflows.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PAL Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in PAL Workflow | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Diazirine-Alkyne Probe [42] [43] | The core active molecule; provides target binding and enables covalent crosslinking & subsequent detection. | Must be validated to ensure it retains the bioactivity of the parent compound. Steric impact of the tag should be minimized [38]. |

| Acid-Cleavable Biotin-Azide [43] | Reporter handle for enrichment and purification; attached via CuAAC. The acid-cleavable linker allows gentle release of conjugated peptides for MS analysis. | The isotopic coding (e.g., 13C2:12C2) provides a distinct MS1 pattern for validating peptide spectral matches [43]. |

| Streptavidin Agarose Beads [43] | Solid support for affinity purification of biotin-tagged, crosslinked proteins. | Essential for removing non-specifically bound proteins before MS analysis. |

| UV Lamp System [43] | Light source for photoactivating the diazirine group to generate the reactive carbene. | Wavelength should match the probe's activation spectrum (e.g., ~350 nm). Cooling the system helps maintain sample integrity [43]. |

| CuAAC "Click" Chemistry Kit [38] [43] | Reagents for copper-catalyzed cycloaddition to attach the biotin tag to the alkyne on the crosslinked protein. | Includes a copper catalyst and reducing agent. Picolyl azide handles can enhance reaction rate via chelation [43]. |

Case Study: Target Identification for an apoE Secretion Enhancer

A powerful example of PAL in action comes from the identification of the functional target of a pyrrolidine lead compound that increased astrocytic apoE secretion in a phenotypic screen [39]. Researchers designed a clickable photoaffinity probe based on the lead and used probe-based quantitative chemical proteomics in human astrocytoma cells. This approach identified Liver X Receptor β (LXRβ) as the direct target. Binding was further validated using a Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA), which showed that the small molecule ligand stabilized LXRβ. Additionally, mass spectrometry identified a probe-modified peptide, allowing the researchers to propose a model where the probe binds in the ligand-binding pocket of LXRβ [39]. This study highlights how PAL can definitively link a phenotypic hit to its molecular target, de-risking the drug discovery process.

Photoaffinity Labeling stands as a powerful and versatile methodology for moving from a phenotypic observation to a validated molecular target. The strategic design of probes incorporating diazirine and alkyne functionalities, combined with robust live-cell experimental protocols and quantitative mass spectrometry, provides researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for interrogating the direct interactors of bioactive small molecules. As the technology continues to evolve, particularly with improvements in photoreactive groups and chemoproteomic techniques, its role in strengthening the mechanistic understanding of phenotypic screening hits and accelerating drug development will only grow more critical.