Taming the Data Deluge: Computational Strategies for Large-Scale Chemogenomic NGS

The integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) into chemogenomics—the study of how genes influence drug response—generates datasets of immense scale and complexity, creating significant computational bottlenecks.

Taming the Data Deluge: Computational Strategies for Large-Scale Chemogenomic NGS

Abstract

The integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) into chemogenomics—the study of how genes influence drug response—generates datasets of immense scale and complexity, creating significant computational bottlenecks. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the computational landscape of large-scale chemogenomic NGS data. We explore the foundational data challenges and the pivotal role of AI, detail modern methodological approaches including multi-omics integration and cloud computing, present proven strategies for pipeline optimization and troubleshooting, and finally, examine rigorous frameworks for analytical validation and performance comparison. By synthesizing these core areas, this article serves as a strategic roadmap for overcoming computational hurdles to accelerate drug discovery and the advancement of precision medicine.

The Scale of the Challenge: Foundational Concepts in Chemogenomic Data Complexity

The integration of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) into chemogenomics has propelled the field squarely into the "big data" era, characterized by the three V's: Volume, Velocity, and Variety [1] [2]. In chemogenomics, Volume refers to the immense amount of data generated from sequencing and screening; Velocity is the accelerating speed of this data generation and the rate at which it must be processed to be useful; and Variety encompasses the diverse types of data, from genomic sequences and gene expression to chemical structures and protein-target interactions [1] [2]. Managing these three properties presents significant computational challenges that require sophisticated data management and analysis strategies to advance drug discovery and precision medicine [3].

Table 1: The Three V's of Chemogenomic Data

| Characteristic | Definition in Chemogenomics | Example Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Volume | The vast quantity of data points generated from high-throughput technologies. | NGS platforms, HTS assays (e.g., Tox21), public databases (e.g., PubChem, ChEMBL) [1]. |

| Velocity | The speed at which new chemogenomic data is generated and must be processed. | Rapid sequencing runs, continuous data streams from live-cell imaging, real-time analysis needs for clinical applications [2] [3]. |

| Variety | The diversity of data types and formats that must be integrated. | DNA sequences, RNA expression, protein targets, chemical structures, clinical outcomes, spectral data [1] [3]. |

Quantifying the Data Deluge: Volume in Context

The volume of publicly available chemical and biological data has grown exponentially over the past decade. Key repositories have seen a massive increase in both the number of compounds and the number of biological assays, fundamentally changing the landscape of computational toxicology and drug discovery [1].

Table 2: Volume of Data in Public Repositories (2008-2018)

| Database | Record Type | ~2008 Count | ~2018 Count | Approx. Increase | Key Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem [1] | Unique Compounds | 25.6 million | 96.5 million | >3.7x | Chemical structures, bioactivity data |

| Bioassay Records | ~1,500 | >1 million | >666x | Results from high-throughput screens | |

| ChEMBL [1] | Bioassays | - | 1.1 million | - | Binding, functional, and ADMET data for drug-like compounds |

| Compounds | - | 1.8 million | - | ||

| ACToR [1] | Compounds | - | >800,000 | - | Aggregated in vitro and in vivo toxicity data |

| REACH [1] | Unique Substances | - | 21,405 | - | Data submitted under European Union chemical legislation |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Designing a Focused Anticancer Compound Library

This methodology outlines the construction of a targeted screening library, a common task in precision oncology that must contend with all three V's of chemogenomic data [4].

Objective: To design a compact, target-annotated small-molecule library for phenotypic screening in patient-derived cancer models, maximizing cancer target coverage while minimizing library size.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Define the Target Space:

Identify Compound-Target Interactions (Theoretical Set):

Apply Multi-Stage Filtering (Large-scale & Screening Sets):

- Global Activity Filter: Remove compounds lacking robust evidence of biological activity [4].

- Potency Filter: For each target, select the most potent compounds to reduce redundancy [4].

- Availability Filter: Filter compounds based on commercial availability for screening, finalizing the physical library (e.g., 1,211 compounds) while retaining high target coverage (e.g., 84%) [4].

Validation via Pilot Screening:

Workflow: Data Generation to Analysis in NGS

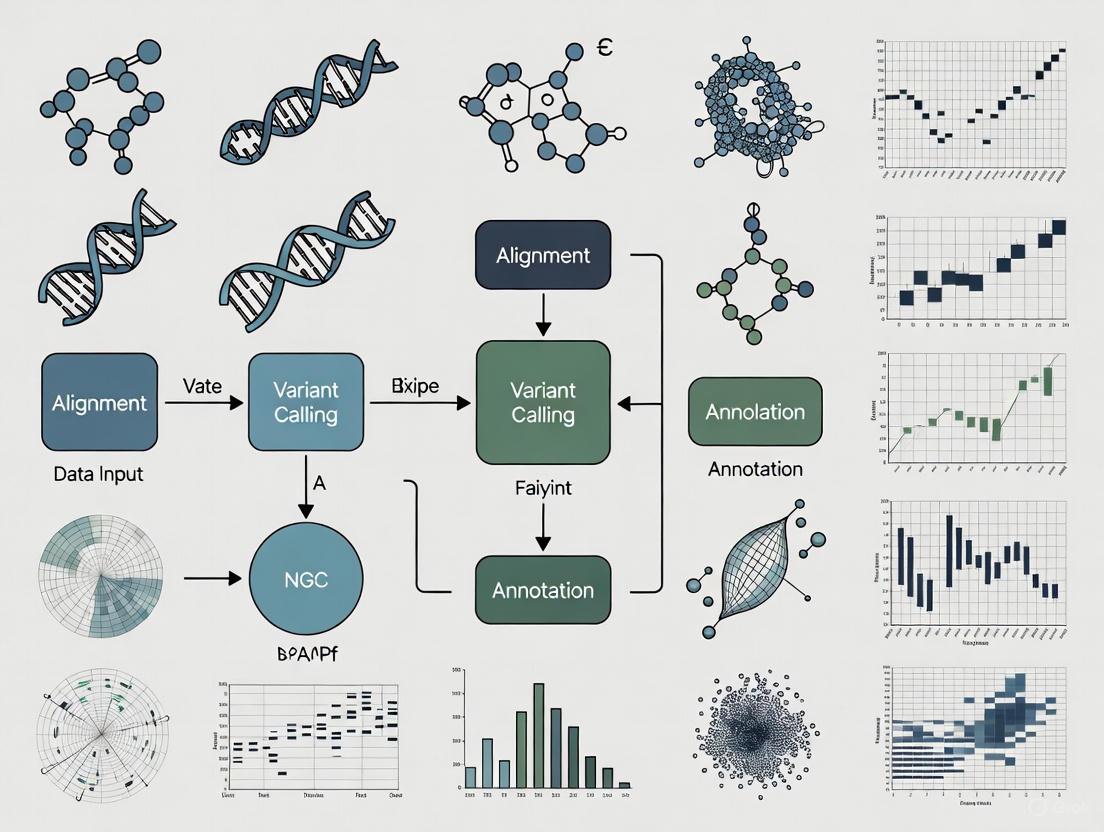

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow from sample preparation to data analysis in an NGS-based chemogenomic study, highlighting potential failure points.

Diagram 1: NGS workflow showing key failure points.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common computational and experimental challenges faced by researchers working with large-scale chemogenomic data.

FAQ: Data Management & Analysis

Q: Our lab generates terabytes of NGS data. What are the most efficient strategies for storing and transferring these large datasets?

A: The volume and velocity of NGS data make traditional internet transfer inefficient. Recommended strategies include:

- Centralized Housing: Store data in a central location and bring high-performance computing (HPC) resources to the data, rather than moving the data itself [3].

- Physical Transfer: For initial transfers, copying data to large storage drives and shipping them is often more efficient than network transfer [3].

- Cloud & Heterogeneous Computing: Leverage cloud computing environments and specialized hardware accelerators to manage processing demands and costs [3].

Q: How can we integrate diverse data types (Variety) like genomic sequences, chemical structures, and HTS assay results?

A: The variety of data requires robust informatics pipelines.

- Standardization: Invest time in converting data into common, interoperable formats. The lack of industry-wide standards for NGS data beyond simple text files makes this a critical step [3].

- Advanced Modeling: Use computational environments designed for building complex models (e.g., Bayesian networks) that integrate diverse, large-scale data sets to predict complex phenotypes like disease susceptibility or drug response [3].

Q: What are the common computational bottlenecks in analyzing large chemogenomic datasets?

A: Understanding your problem's nature is key to selecting the right computational platform [3]. Bottlenecks can be:

- Network-Bound: Data is too large to efficiently copy over the network.

- Disk-Bound: Data cannot be processed on a single disk and requires distributed storage.

- Memory-Bound: The analysis algorithm requires more random access memory (RAM) than is available.

- Computationally Bound: The algorithm itself is intensely complex (e.g., NP-hard problems like reconstructing Bayesian networks) [3].

FAQ: NGS Experiment Troubleshooting

Q: My NGS library yield is low. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A: Low yield is a frequent issue often traced to early steps in library preparation [5].

Table 3: Troubleshooting Low NGS Library Yield

| Root Cause | Mechanism of Failure | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality | Degraded DNA/RNA or contaminants (phenol, salts) inhibit enzymes. | Re-purify input sample; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit) over UV absorbance; check purity ratios (260/230 > 1.8) [5]. |

| Fragmentation Issues | Over- or under-shearing produces fragments outside the optimal size range for adapter ligation. | Optimize fragmentation time/energy; verify fragment size distribution on BioAnalyzer or similar platform [5]. |

| Inefficient Ligation | Suboptimal adapter-to-insert ratio or poor ligase performance. | Titrate adapter:insert molar ratios; ensure fresh ligase and buffer; maintain optimal reaction temperature [5]. |

| Overly Aggressive Cleanup | Desired library fragments are accidentally removed during purification or size selection. | Adjust bead-to-sample ratios; avoid over-drying magnetic beads during clean-up steps [5]. |

Q: My sequencing data shows a high percentage of adapter dimers. How do I resolve this?

A: A sharp peak around 70-90 bp in an electropherogram indicates adapter-dimer contamination [5].

- Root Cause: This is typically due to an imbalance in the adapter-to-insert molar ratio, with excess adapters promoting dimer formation, or inefficient ligation where adapters fail to ligate to the target insert [5].

- Solutions:

- Reanalyze Data: If possible, reanalyze the run with the correct barcode settings (e.g., select "RNABarcodeNone") to automatically trim the adapter sequence [6].

- Optimize Ligation: Precisely quantify your insert DNA and titrate the adapter amount to find the optimal ratio [5].

- Improve Cleanup: Use optimized bead-based cleanups to more effectively remove short adapter-dimer products prior to sequencing [5].

Q: Our automated variant calling pipeline is producing inconsistent results. What should I check?

A: Inconsistencies often stem from issues with data quality, formatting, or software configuration.

- Check Data Quality: Review sequence quality metrics (e.g., Phred scores), coverage depth, and alignment rates. Low-quality data will lead to unreliable variant calls.

- Verify File Formats: Ensure all input files are in the correct, standardized format (e.g., BAM, VCF) as required by your tools. Incompatibilities between tools are common [3].

- Review Parameters: Examine the software parameters and thresholds used in the analysis pipeline. Small changes can significantly impact results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful navigation of the chemogenomic data deluge requires both wet-lab and computational tools.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomic Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Focused Compound Libraries | Target-annotated sets of small molecules for phenotypic screening in relevant disease models. | C3L (Comprehensive anti-Cancer small-Compound Library): A physically available library of 789 compounds covering 1,320 anticancer targets for identifying patient-specific vulnerabilities [4]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Assays | Rapid in vitro tests to evaluate compound toxicity or bioactivity across hundreds of targets. | ToxCast/Tox21 assays: Used to profile thousands of environmental chemicals and drugs, generating millions of data points for predictive modeling [1]. |

| Public Data Repositories | Sources of large-scale chemical, genomic, and toxicological data for model building and validation. | PubChem: Bioactivity data [1]. ChEMBL: Drug-like molecule data [1]. CTD: Chemical-gene-disease relationships [1]. GDC Data Portal: Standardized cancer genomic data [7]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Integrated suites of software tools for processing and interpreting NGS data. | GDC Bioinformatics Pipelines: Used for harmonizing genomic data, ensuring consistency and reproducibility across cancer studies [7]. |

| Computational Environments | Platforms to handle the storage and processing demands of large, complex datasets. | Cloud Computing: Scalable resources for variable workloads [3]. Heterogeneous Computing: Uses specialized hardware (e.g., GPUs) to accelerate specific computational tasks [3]. |

The journey from raw FASTQ files to actionable biological insights is a complex computational process, particularly within large-scale chemogenomic research. This pipeline, which transforms sequencing data into findings that can inform drug discovery, is fraught with bottlenecks in data management, processing power, and analytical interpretation. This guide provides a structured troubleshooting resource to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals identify and overcome the most common challenges, ensuring robust, reproducible, and efficient analysis of next-generation sequencing (NGS) data.

Section 1: Data Quality & Preprocessing Bottlenecks

FAQ: Why is my initial data quality so poor, and how can I fix it?

Problem: The raw FASTQ data from the sequencer has low-quality scores, adapter contamination, or other artifacts that compromise downstream analysis.

Diagnosis & Solution: Poor data quality often stems from issues during sample preparation or the sequencing run itself. A thorough quality control (QC) check is the critical first step.

- Always verify file type, structure, and read quality before starting analysis [8]. Use QC tools like FastQC to assess base quality, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences [8].

- If problems are detected, use trimming tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences [8].

- Consult the following table to diagnose common quality issues:

| Failure Signal | Possible Root Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low-quality reads & high error rates | Over- or under-amplification during PCR; degraded input DNA/RNA | Trim low-quality bases. Re-check input DNA/RNA quality and quantity using fluorometric methods [5]. |

| Adapter dimer peaks (~70-90 bp) | Inefficient cleanup post-ligation; suboptimal adapter concentration | Optimize bead-based cleanup ratios; titrate adapter-to-insert molar ratio [5]. |

| Low library complexity & high duplication | Insufficient input DNA; over-amplification during library prep | Use adequate starting material; reduce the number of PCR cycles [5]. |

| "Mixed" sequences from the start | Colony contamination or multiple templates in reaction | Ensure single-clone sequencing and verify template purity [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Standard Preprocessing Workflow

- Quality Control: Run FastQC on raw FASTQ files to generate a quality report.

- Adapter Trimming: Use Trimmomatic with parameters tailored to your sequencing kit and read length (e.g.,

ILLUMINACLIP:TruSeq3-PE.fa:2:30:10:2:True). - Post-trimming QC: Re-run FastQC on the trimmed FASTQ files to confirm issue resolution.

- Data Validation: Check for and resolve any incorrect metadata or incompatible file formats to ensure pipeline compatibility [8].

Section 2: Computational & Workflow Bottlenecks

FAQ: Why is my analysis pipeline so slow, and how can I scale it?

Problem: Data processing, especially alignment and variant calling, is prohibitively slow, making large-scale chemogenomic studies impractical.

Diagnosis & Solution: The computational burden of NGS analysis is a well-known challenge. The solution involves understanding your computational problem and leveraging modern, scalable infrastructure [3].

- Understand Your Computational Problem: Determine if your analysis is disk-bound (I/O limitations), memory-bound (insufficient RAM), or computationally bound (processor-intensive algorithms) [3].

- Use Structured Pipelines: Adopt workflow management systems like Snakemake or Nextflow to create reproducible, parallelized workflows that reduce human error [8].

- Leverage Efficient Formats and Cloud Computing: Use binary formats (BAM/CRAM) to save disk space. For large-scale data, consider a multi-cloud strategy to balance cost, performance, and customizability [10].

Workflow Diagram: From FASTQ to Variants

The following diagram illustrates the core steps and their logical relationships, highlighting stages that are often computationally intensive.

Section 3: Generating Biological Insights

FAQ: How do I transition from a list of variants to a chemogenomic insight?

Problem: You have a VCF file with thousands of variants but struggle to identify which are biologically relevant to drug response or mechanism of action.

Diagnosis & Solution: The bottleneck shifts from data processing to biological interpretation, requiring integration of multiple data sources and specialized tools.

- Use Specialized Variant Detection Tools: Beyond standard callers, employ tools like pGENMI (for analyzing variants in drug responses), CODEX (copy-number variant detection), and LUMPY (structural rearrangement detection) [11].

- Integrate with Public Databases: Annotate your variants using data from sources like the 1000 Genomes Project, Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to assess population frequency and disease association [10] [11].

- Combine Genomic and Clinical Data: For true actionable insights in drug development, integrate genomic data with clinical information. Tools like OntoFusion demonstrate the ontology-based integration of genomic and clinical databases [11].

The following table details key software and data resources essential for a successful NGS experiment in chemogenomics.

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC [8] | Software | Performs initial quality control checks on raw FASTQ data. |

| Trimmomatic [8] | Software | Removes adapter sequences and low-quality bases from reads. |

| BWA [12] [10] | Software | Aligns sequencing reads to a reference genome (hg38). |

| GATK [12] [11] | Software | Industry standard for variant discovery and genotyping. |

| IGV [11] | Software | Integrated Genome Viewer for visualizing aligned sequences. |

| Snakemake/Nextflow [8] | Workflow System | Orchestrates and automates analysis pipelines for reproducibility. |

| Reference Genome (GRC) | Data | A curated human reference assembly (e.g., hg38) from the Genome Reference Consortium for alignment [10]. |

| 1000 Genomes Project | Data | A public catalog of human genetic variation for variant annotation and population context [10] [11]. |

The Central Role of AI and Machine Learning in Decoding Genetic-Drug Interactions

Technical Troubleshooting Guide: Common AI and NGS Data Analysis Issues

This section addresses frequent computational challenges encountered when applying AI to genomic data for drug interaction research.

FAQ 1: My AI model for drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction is performing poorly, with high false negative rates. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

- Problem: A common cause is severe class imbalance in the experimental datasets, where the number of known interacting drug-target pairs (positive class) is vastly outnumbered by non-interacting pairs [13] [14]. This leads to models that are biased toward the majority class and exhibit reduced sensitivity.

- Solution:

- Implement Data Balancing Techniques: Use Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to create high-quality synthetic data for the minority class [13]. One study demonstrated that this approach, combined with a Random Forest classifier, achieved a sensitivity of over 97% on benchmark datasets [13].

- Algorithmic Adjustment: Employ algorithms or loss functions designed for imbalanced data, such as weighted cross-entropy or focal loss, during model training to penalize misclassifications of the minority class more heavily.

FAQ 2: My genomic secondary analysis pipeline is too slow, creating a bottleneck in my research. How can I accelerate it?

- Problem: Traditional CPU-based alignment and variant calling tools cannot keep pace with the data deluge from next-generation sequencing (NGS). A single human genome can generate ~100 gigabytes of data, and global genomic data is projected to reach 40 exabytes by 2025 [15].

- Solution:

- Leverage Hardware Acceleration: Utilize ultra-rapid secondary analysis platforms that leverage GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) acceleration [16]. For instance, tools like the DRAGEN Bio-IT Platform or NVIDIA Parabricks have been shown to accelerate genomic analysis tasks, such as variant calling, by up to 80 times, reducing runtime from hours to minutes [15] [16].

- Optimize Data Storage: Ensure your data is in modern, compressed file formats (e.g., CRAM) and leverage efficient data management platforms like Illumina Connected Analytics to reduce data transfer and access times [16] [10].

FAQ 3: I want to identify novel drug targets from a protein-protein interaction network (PIN). What is a robust computational method for this?

- Problem: PIN data is high-dimensional and non-linear, making it difficult to extract meaningful features for predicting potential drug targets using traditional statistical methods [17].

- Solution:

- Apply Network Embedding with Deep Learning: Use a deep autoencoder to transform the high-dimensional adjacency matrix of the PIN into a low-dimensional representation [17].

- Protocol Overview:

- Data Preparation: Obtain a genome-wide PIN (e.g., with ~6,338 genes and ~35,000 interactions) [17].

- Feature Extraction: Build a symmetric deep autoencoder with multiple encoder and decoder layers. Train the network to reconstruct its input, using the bottleneck layer (e.g., 100 nodes) as the low-dimensional feature vector for each gene [17].

- Target Prediction: Use these latent features to train a classifier (e.g., XGBoost) to distinguish known drug targets from non-targets. This model can then prioritize novel candidate targets [17].

FAQ 4: The computational infrastructure for my large-scale chemogenomic project is becoming unmanageably expensive. What are my options?

- Problem: AI compute demand in biotech is surging and rapidly outpacing the supply of necessary infrastructure. Training large models, like AlphaFold, requires thousands of GPU-weeks of computation [18].

- Solution:

- Adopt a Multi-Cloud Strategy: Balance cost, performance, and customizability by not relying on a single cloud provider. This allows you to leverage best-in-class services for different tasks (e.g., specialized GPU instances for model training, optimized storage for genomic data) [10].

- Explore "Neocloud" Providers: Consider specialized GPU cloud providers like CoreWeave or Lambda, which are securing multi-billion dollar deals to supply compute specifically for AI workloads [18].

- Centralize Data and Workflows: House large datasets centrally in the cloud and bring your computation to the data to avoid costly and slow data transfers over the internet. Use workflow engines (e.g., Nextflow) to ensure reproducible and portable analyses across different cloud environments [10] [3].

Experimental Protocols for Key AI Applications in Drug Discovery

This section provides detailed methodologies for critical experiments in AI-driven genomics and drug interaction research.

Protocol: Predicting Drug-Target Interactions (DTI) with a Hybrid ML/DL and GAN Framework

This protocol is based on a 2025 Scientific Reports study that introduced a novel framework for DTI prediction [13].

1. Objective: To accurately predict binary drug-target interactions by addressing data imbalance and leveraging comprehensive feature engineering.

2. Materials & Data:

- Datasets: Use publicly available binding affinity datasets such as BindingDB (e.g., subsets for Kd, Ki, or IC50 values) [13].

- Software: Python with libraries including Scikit-learn (for Random Forest), TensorFlow or PyTorch (for implementing GANs).

3. Methodological Steps:

- Step 1: Feature Engineering

- Drug Features: Encode the molecular structure of each drug using MACCS keys, a type of structural fingerprint that represents the presence or absence of predefined substructures [13].

- Target Features: Encode the protein sequence of each target using its amino acid composition (frequency of each amino acid) and dipeptide composition (frequency of adjacent amino acid pairs) [13].

- Feature Vector Construction: Concatenate the drug and target feature vectors to create a unified representation for each drug-target pair.

- Step 2: Address Data Imbalance

- Identify Minority Class: The known interacting pairs (positive class) are typically the minority.

- Generate Synthetic Data: Train a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) on the feature vectors of the minority class. The generator learns to produce realistic synthetic feature vectors for interacting pairs, which are then added to the training set to balance the class distribution [13].

- Step 3: Model Training and Prediction

- Classifier: Train a Random Forest Classifier on the balanced training dataset. The Random Forest is robust to overfitting and handles high-dimensional data well [13].

- Validation: Perform rigorous cross-validation and evaluate the model on held-out test sets from BindingDB.

4. Expected Outcomes: The proposed GAN+RFC model has demonstrated high performance on BindingDB datasets. You can expect metrics similar to the following [13]: Table: Performance Metrics of the GAN+RFC Model on BindingDB Datasets

| Dataset | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | F1-Score (%) | ROC-AUC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BindingDB-Kd | 97.46 | 97.49 | 97.46 | 98.82 | 97.46 | 99.42 |

| BindingDB-Ki | 91.69 | 91.74 | 91.69 | 93.40 | 91.69 | 97.32 |

| BindingDB-IC50 | 95.40 | 95.41 | 95.40 | 96.42 | 95.39 | 98.97 |

Protocol: Prioritizing Novel Drug Targets using Deep Autoencoders on Protein Interaction Networks

This protocol is adapted from a 2021 study on target prioritization for Alzheimer's disease [17].

1. Objective: To infer novel, putative drug-target genes by learning low-dimensional representations from a high-dimensional protein-protein interaction network (PIN).

2. Materials & Data:

- PIN Data: A comprehensive human PIN (e.g., from curated databases like BioGRID or STRING).

- Known Drug Targets: A list of established drug targets for your disease of interest, available from databases like DrugBank [17].

- Software: A deep learning framework like Keras with a TensorFlow backend.

3. Methodological Steps:

- Step 1: Data Preparation

- Represent the PIN as a binary adjacency matrix where rows and columns are proteins, and a value of 1 indicates an interaction.

- Step 2: Dimensionality Reduction with Deep Autoencoder

- Network Architecture: Construct a symmetric deep autoencoder. The study used the following structure [17]:

- Encoder Layers: 6338 (input) -> 3000 -> 1500 -> 500 -> 250 -> 150 -> 100 (bottleneck).

- Decoder Layers: 100 -> 150 -> 250 -> 500 -> 1500 -> 3000 -> 6338 (output).

- Activation & Training: Use ReLU activation for all layers except the output layer, which uses a sigmoid function. Train the network to minimize the binary cross-entropy loss between the input and output matrices, forcing the bottleneck layer to learn a compressed, meaningful representation.

- Network Architecture: Construct a symmetric deep autoencoder. The study used the following structure [17]:

- Step 3: Target Gene Classification

- Feature Extraction: For each gene, use its 100-dimensional vector from the bottleneck layer as its feature set.

- Handle Class Imbalance: Since known drug targets are few, use techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) to balance the training data [17].

- Train a Classifier: Use a powerful classifier like XGBoost on the low-dimensional features to predict the probability of a gene being a drug target.

4. Expected Outcomes: The model will output a prioritized list of genes ranked by their predicted likelihood of being viable drug targets. The original study successfully identified genes like DLG4, EGFR, and RAC1 as novel putative targets for Alzheimer's disease using this methodology [17].

Visualization of Workflows and Data Relationships

Below are diagrams illustrating the core experimental and computational workflows described in this guide.

AI for Genomic Data Analysis Workflow

Drug-Target Interaction Prediction with GAN

Table: Essential Computational Tools and Datasets for AI-Driven Genomic Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| BindingDB [13] | Database | A public database of measured binding affinities for drug-target interactions. | Provides curated data on protein-ligand interactions; essential for training and validating DTI prediction models. |

| DrugBank [17] | Database | A comprehensive database containing detailed drug and drug-target information. | Used to obtain known drug-target pairs for model training and validation in target prioritization tasks. |

| DRAGEN Bio-IT Platform [16] | Software | A secondary analysis platform for NGS data. | Provides ultra-rapid, accurate analysis of whole genomes, exomes, and transcriptomes via hardware-accelerated algorithms. |

| Deep Autoencoder [17] | Algorithm | A deep learning model for non-linear dimensionality reduction. | Transforms high-dimensional, sparse data (e.g., protein interaction networks) into low-dimensional, dense feature vectors. |

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) [13] | Algorithm | A framework for generating synthetic data. | Used to balance imbalanced datasets by creating realistic synthetic samples of the minority class (e.g., interacting drug-target pairs). |

| Random Forest Classifier [13] | Algorithm | A robust machine learning model for classification and regression. | Effective for high-dimensional data and less prone to overfitting; commonly used for final prediction tasks after feature engineering. |

| Illumina Connected Analytics [16] | Platform | A cloud-based data science platform for multi-omics data. | Enables secure storage, management, sharing, and analysis of large-scale genomic datasets in a collaborative environment. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Data Storage and Transfer Issues

Problem: Inability to efficiently store, manage, or transfer large-scale NGS data.

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Best Practices |

|---|---|---|

| High Storage Costs [19] [20] | Storing all data, including raw and intermediate files, in expensive primary storage. | Implement a tiered storage policy. Use cost-effective cloud object storage (e.g., AWS HealthOmics) or archives (e.g., Amazon S3 Glacier) for infrequently accessed data, reducing costs by over 90% [19]. |

| Slow Data Transfer [3] | Network speeds are too slow for transferring terabytes of data over the internet. | For initial massive data migration, consider shipping physical storage drives. For ongoing analysis, use centralized cloud storage and bring computation to the data to avoid transfer bottlenecks [3]. |

| Performance Bottlenecks in Analysis [20] | Storage solution cannot support the parallel file access required by genomic workflows. | Choose a storage solution that supports parallel file access for rapid, reliable file retrieval during data processing [20]. |

| Data Security & Privacy Concerns [20] [21] | Lack of robust controls for protecting sensitive genetic information. | Select solutions with in-flight and at-rest encryption, role-based access controls, and compliance with regulations like HIPAA and GDPR [21]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Workflow Reproducibility and Provenance

Problem: Inability to reproduce or validate previously run genomic analyses.

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Best Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Failed Workflow Execution in a New Environment [22] | Implicit assumptions in the original workflow (e.g., specific software versions, paths, or reference data) are not documented or captured. | Use explicit workflow specification languages like the Common Workflow Language (CWL) to define all steps, software, and parameters. Record prospective provenance (workflow specification) and retrospective provenance (runtime execution details) [22]. |

| Inconsistent Analysis Results [22] | Use of different software versions or parameters than the original analysis. | Capture comprehensive provenance for every run, including exact software versions, all parameters, and data produced at each step. Leverage Workflow Management Systems (WMS) designed for this purpose [22]. |

| Difficulty Reusing Published Work [22] | Published studies often omit crucial details like software versions and parameter settings. | Adopt a practice of explicit declaration in all publications. Provide access to the complete workflow code, data, and computational environment used whenever possible [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Data Storage and Infrastructure

Q: What are the key features to look for in a genomic data storage solution? A: For large-scale projects, your storage solution should have:

- Scalability: The ability to scale to exabytes without performance loss, ideally in a hybrid cloud environment [20].

- Security & Compliance: Features like encryption and access controls that meet standards like HIPAA and GDPR [20] [21].

- Object Storage & Parallel File Access: Support for data lakes and parallel access to prevent bottlenecks during analysis [20].

- Cost-Effective Tiering: Integrated hot and cold storage options to manage lifecycle and reduce costs [19] [20].

Q: How can we manage the cost of storing petabytes of genomic data? A: The most effective strategy is a tiered approach. Move infrequently accessed data, such as raw sequencing data post-analysis, to low-cost archival storage like Amazon S3 Glacier Deep Archive, which can save over 90% in storage costs [19].

Reproducibility and Provenance

Q: What is the difference between reproducibility and repeatability in the context of genomic workflows? A:

- Repeatability: A researcher redoing their own analysis in the same environment to achieve the same outcome [22].

- Reproducibility: An independent researcher confirming or redoing the analysis, potentially in a different environment. Reproducibility is a higher standard and is crucial for validating scientific findings [22].

Q: What minimum information should be tracked to ensure a workflow is reproducible? A: At a minimum, you must capture:

- Prospective Provenance: The complete workflow specification, including all tools and their versions, parameters, and data inputs [22].

- Retrospective Provenance: The record of a specific workflow execution, including software versions, parameters, and data outputs at each step [22].

- Computational Environment: Details of the operating system, hardware, and library dependencies.

Workflow Management

Q: What are the main approaches to defining and executing genomic workflows? A: The three broad categories are:

- Pre-built Pipelines: Customized, command-line pipelines (e.g., Cpipe, bcbio-nextgen) supported by specific labs. They require significant computational expertise to reproduce [22].

- GUI-based Workbenches: Integrated platforms (e.g., Galaxy) with graphical interfaces that are more accessible but may be less flexible [22].

- Standardized Workflow Descriptions: Systems using standardized languages (e.g., Common Workflow Language - CWL) to define workflows in a portable and reproducible way, making them easier to share and execute across different environments [22].

Q: Why do workflows often fail when transferred to a different computing environment? A: Failure is often due to hidden assumptions in the original workflow, such as hard-coded file paths, specific versions of software installed via a package manager, or reliance on a particular operating system. Explicitly declaring all dependencies using containerization (e.g., Docker) and workflow specification languages mitigates this [22].

Workflow and Data Relationship Diagrams

NGS Data Management and Reproducibility Workflow

Genomic Workflow Reproducibility Lifecycle

Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Item / Solution | Function in Large-Scale NGS Projects |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow Management Systems (WMS) | Galaxy [22] | A graphical workbench that simplifies the construction and execution of complex bioinformatics workflows without extensive command-line knowledge. |

| Common Workflow Language (CWL) [22] | A specification language for defining analysis workflows and tools in a portable and scalable way, enabling reproducibility across different software environments. | |

| Cpipe [22] | A pre-built, bioinformatics-specific pipeline for genomic data analysis, often customized by individual laboratories for targeted sequencing projects. | |

| Cloud & Data Platforms | AWS HealthOmics [19] | A managed service purpose-built for bioinformatics, providing specialized storage (Sequence Store) and workflow computing to reduce costs and complexity. |

| Illumina Connected Analytics [21] | A cloud-based data platform for secure, scalable management, analysis, and exploration of multi-omics data, integrated with NGS sequencing systems. | |

| DNAnexus [19] | A cloud-based platform that provides a secure, compliant environment for managing, analyzing, and collaborating on large-scale genomic datasets, such as the UK Biobank. | |

| Informatics Tools | DRAGEN Bio-IT Platform [21] | A highly accurate and ultra-rapid secondary analysis solution that can be run on-premises or in the cloud for processing NGS data. |

| BaseSpace Sequence Hub [21] | A cloud-based bioinformatics environment directly integrated with Illumina sequencers for storage, primary data analysis, and project management. |

Ethical and Security Considerations for Sensitive Pharmacogenomic Data

Fundamental Concepts and Importance

What are the primary security risks associated with storing pharmacogenomic data?

Pharmacogenomic data faces significant security challenges due to its sensitive, immutable nature. Unlike passwords or credit cards, genetic information cannot be reset once compromised, and a breach can reveal hereditary information affecting entire families [23]. Primary risks include:

- Data Privacy Compromises: Genomic data is personally identifiable and immutable. Exposure can lead to identity theft and genetic discrimination [23].

- Data Integrity Attacks: Cyberattacks can manipulate genetic information, leading to incorrect diagnoses or treatment recommendations [23].

- Third-Party and Collaboration Risks: Data sharing with external collaborators increases potential entry points for attacks [23].

- Regulatory Complexity: Strict compliance requirements (HIPAA, GDPR, GINA) are difficult to maintain, and breaches can result in significant fines [23].

Why is pharmacogenomic data considered particularly sensitive?

Pharmacogenomic data is uniquely sensitive because it reveals information not only about an individual but also about their biological relatives. This data is permanent and unchangeable, creating lifelong privacy concerns [24] [23]. The ethical implications are substantial, as genetic information could be misused for discrimination in employment, insurance, or healthcare access [24]. This has led to regulations like the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) in the United States [24].

Security Framework Implementation

What technical security measures are recommended for protecting pharmacogenomic data?

A multi-layered security approach is essential for comprehensive protection of pharmacogenomic datasets [23]:

Table 1: Security Measures for Pharmacogenomic Data Protection

| Security Measure | Implementation Examples | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Robust Encryption | Data encryption at rest and in transit; Quantum-resistant encryption [23] | Prevents unauthorized access |

| Strict Access Controls | Multi-factor authentication (MFA); Role-based access control (RBAC) [23] | Limits data exposure |

| AI-Driven Threat Detection | ML models to detect unusual access patterns; Real-time anomaly detection [23] | Identifies potential breaches |

| Blockchain Technology | Immutable records of data transactions; Secure data sharing [25] [23] | Ensures data integrity |

| Privacy-Preserving Technologies | Federated learning; Homomorphic encryption [23] | Enables analysis without exposing raw data |

How can blockchain technology enhance security for pharmacogenomic data?

Blockchain provides decentralized, distributed storage that eliminates single points of failure. Its immutability prevents alteration of past records, creating a secure audit trail [25]. Smart contracts on Ethereum platforms can store and query gene-drug interactions with time and memory efficiency, ensuring data integrity while maintaining accessibility for authorized research [25]. Specific implementations include index-based, multi-mapping approaches that allow efficient querying by gene, variant, or drug fields while maintaining cryptographic security [25].

Data Protection Workflow Using Blockchain

Ethical Framework and Compliance

What are the core ethical principles for handling pharmacogenomic data?

Ethical pharmacogenomic data management requires balancing innovation with fundamental rights [24]:

- Informed Consent: Patients must understand implications of genetic testing, including risks of unforeseen findings and complexities of disclosing information [24].

- Privacy Protection: Genetic data storage and sharing must prevent misuse of sensitive information [24].

- Equitable Access: Benefits of personalized medicine must be accessible across socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic groups [24].

- Non-Discrimination: Policies must prevent discrimination based on genetic predispositions in healthcare, employment, and insurance [24].

How should researchers address informed consent for pharmacogenomic studies?

Informed consent processes must clearly communicate how genetic data will be used, stored, and shared. Patients should understand the potential for incidental findings and the implications for biological relatives [24]. Consent forms should specify data retention periods, access controls, and how privacy will be maintained in collaborative research. In multi-omics studies, ensuring informed consent for comprehensive data sharing is complex but essential [26].

Troubleshooting Common Implementation Challenges

How can researchers troubleshoot data integrity and quality issues in pharmacogenomic analysis?

Data quality issues can arise from various sources in pharmacogenomic workflows:

- Genotype Calling Problems: Undetermined results may indicate sample quality issues, degradation, or impurities. Review amplification curves and real-time traces for "noisy" data [27].

- Contamination Issues: Examine QC images for leaks or contamination. Clean instrument blocks with 95% ethanol solution using lint-free cloths [27].

- Unexpected Negative Control Results: No-template controls clustering with samples may indicate probe cleavage. Analyze using lower cycle thresholds before spurious cleavage occurs [27].

What solutions address computational challenges with large-scale pharmacogenomic datasets?

Large-scale pharmacogenomic data requires sophisticated computational strategies:

- Cloud Computing Platforms: Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Google Cloud Genomics provide scalable infrastructure to handle terabyte-scale datasets [26].

- AI and Machine Learning: Tools like Google's DeepVariant utilize deep learning to identify genetic variants with greater accuracy than traditional methods [26].

- Multi-Omics Integration: Combine genomics with transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics for comprehensive analysis [28] [26].

- Data Reduction Techniques: Implement efficient compression algorithms and data subsetting strategies for manageable analysis [26].

Regulatory Compliance and Data Sharing

What regulatory frameworks govern pharmacogenomic data management globally?

Table 2: Key Regulatory Frameworks for Pharmacogenomic Data

| Region | Primary Regulations | Key Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| United States | HIPAA, GINA, CLIA [29] | Privacy protection, non-discrimination, laboratory standards |

| European Union | GDPR, EMA Guidelines [23] [29] | Data protection, privacy by design, cross-border transfer rules |

| International | UNESCO Declaration, WHO Guidelines [29] | Ethical frameworks, genomic methodology implementation |

How can researchers enable secure data sharing for collaborative pharmacogenomics?

Secure data sharing requires both technical and policy solutions:

- Federated Learning: Analyze data across institutions without transferring raw genetic information [23].

- Blockchain-Based Sharing: Create immutable records of data transactions while maintaining transparency [25].

- Data Use Agreements: Establish clear terms for data access, purpose limitations, and security requirements.

- Standardized Formats: Use structured data formats like HL7's FHIR for consistent interpretation across systems [30].

Ethical Data Implementation Workflow

Table 3: Essential Pharmacogenomic Research Resources

| Resource Name | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| PharmGKB | Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Repository | Clinical annotations, drug-centered pathways, VIP genes [31] |

| CPIC Guidelines | Clinical Implementation | Evidence-based gene/drug guidelines, clinical recommendations [29] [31] |

| dbSNP | Genetic Variation Database | Public archive of SNPs, frequency data, submitter handles [31] |

| DrugBank | Drug and Target Database | Drug mechanisms, interactions, target sequences [31] |

| SIEM Solutions | Security Monitoring | Real-time threat detection, compliance reporting, behavioral analytics [23] |

Frequently Asked Questions

How can we prevent genomic data breaches in multi-institutional research?

Preventing breaches requires a comprehensive approach: implement robust encryption both at rest and in transit, enforce strict access controls with multi-factor authentication, deploy AI-driven threat detection to identify unusual access patterns, utilize blockchain for data integrity, and ensure continuous monitoring with automated incident response [23]. Privacy-preserving technologies like federated learning allow analysis without exposing raw genetic information [23].

What are the solutions for managing computational demands of large-scale NGS data?

Computational challenges can be addressed through cloud computing platforms that provide scalable infrastructure [26], AI and machine learning tools for efficient variant calling [32] [26], multi-omics integration approaches [28] [26], and specialized bioinformatics pipelines for complex genomic data analysis [31]. Cloud platforms like AWS and Google Cloud Genomics can handle terabyte-scale datasets while complying with security regulations [26].

How do regulatory differences across countries impact global pharmacogenomic research?

Regulatory variations create significant challenges for international collaboration. While the United States has a comprehensive pharmacogenomics policy framework extending to clinical and industry settings [29], other regions have different requirements. Researchers must navigate varying standards for informed consent, data transfer, and privacy protection. Global harmonization efforts through organizations like WHO aim to foster international collaboration and enable secure data sharing [29].

Modern Computational Architectures and AI-Driven Analytical Methods

Leveraging Cloud Computing (AWS, Google Cloud) for Scalable Genomic Analysis

FAQs: Core Concepts and Configuration

Q1: Why should I use cloud platforms over on-premises servers for large-scale genomic studies?

Cloud platforms like AWS and Google Cloud provide virtually infinite scalability, which is essential for handling the petabyte-scale data common in chemogenomic NGS research. They offer on-demand access to High-Performance Computing (HPC) instances, eliminating the need for large capital expenditures on physical hardware and its maintenance. This allows research teams to process hundreds of genomes in parallel, reducing analysis time from weeks to hours. Furthermore, major cloud providers comply with stringent security and regulatory frameworks like HIPAA and GDPR, ensuring sensitive genomic data is handled securely [33] [34] [35].

Q2: What are the key AWS services for building a bioinformatics pipeline?

A robust bioinformatics pipeline on AWS typically leverages these core services [34]:

- Amazon S3: Provides durable and scalable object storage for raw sequencing data (FASTQ), intermediate files, and final results.

- AWS Batch: A fully managed service that dynamically provisions compute resources (Amazon EC2 instances) to run hundreds of thousands of batch jobs, such as alignment and variant calling, without managing the underlying infrastructure.

- Amazon EC2: Offers a broad selection of virtual server configurations, including compute-optimized and memory-optimized instances, tailored to different pipeline stages.

- AWS HealthOmics: A purpose-built service to store, query, and analyze genomic and other omics data, simplifying the execution of workflow languages like Nextflow and Cromwell [36].

- AWS Step Functions: Used to orchestrate and visualize the multiple steps of a genomic workflow, ensuring reliable execution and error handling [34].

Q3: What are the key Google Cloud services for rapid NGS analysis?

For rapid NGS analysis on GCP, researchers commonly use [37] [38] [39]:

- Compute Engine: Provides customizable Virtual Machines (VMs). High-CPU or GPU-accelerated machine types can be tailored for specific pipelines like Sentieon (CPU-optimized) or Parabricks (GPU-optimized).

- Cloud Storage: Serves a function similar to Amazon S3, offering a unified repository for large genomic datasets.

- Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE): Allows for the containerized deployment of bioinformatics tools, enabling scalable and portable pipeline execution.

- Batch: A fully managed service for scheduling, queueing, and executing batch jobs on Google's compute infrastructure, comparable to AWS Batch.

Q4: How can I control and predict costs when running genomic workloads in the cloud?

To manage costs effectively [34] [37]:

- Use Auto-Scaling: Leverage services like AWS Batch or GCP's instance groups to automatically scale compute resources down to zero when no jobs are queued, ensuring you only pay for what you use.

- Select the Right Storage Tier: For data that is infrequently accessed (e.g., archived raw data), use low-cost storage options like Amazon S3 Glacier or its GCP equivalents.

- Monitor and Optimize: Utilize cloud monitoring tools (e.g., Cloud Monitoring, Amazon CloudWatch) to track resource utilization. Benchmark different machine types for your specific tools to find the most cost-effective option.

- Set Budget Alerts: Define budgets and alerts within your cloud console to receive notifications before costs exceed a predefined threshold.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Slow Data Transfer to the Cloud

- Symptoms: Uploading large FASTQ files from a local sequencer or data center takes days, delaying analysis.

- Solution:

- For datasets in the terabyte-to-petabyte range, use physical data transfer devices like the AWS Snow Family. You ship your data on a secure device directly to AWS, which then loads it into your S3 bucket [34].

- For large datasets transferred over the internet, use accelerated data transfer services. AWS DataSync can automate and accelerate moving data from on-premises network-attached storage (NAS) to Amazon S3, and it only transfers changed files for incremental updates [34].

- Ensure your local internet connection is not saturated by other traffic during transfers.

Problem 2: Genomic Workflow Jobs are Failing or Stuck

- Symptoms: Jobs submitted to AWS Batch or a similar orchestrator fail repeatedly or remain in a

RUNNABLEstate without starting. - Solution:

- Check Job Logs: First, examine the CloudWatch Logs for your failed job. The error message often points directly to the issue (e.g., a tool with a non-zero exit code, a missing input file in S3) [34].

- Verify Resource Allocation: Ensure the compute environment (e.g., the EC2 instance type) has sufficient vCPUs and memory for the job. A memory-intensive tool like a genome assembler will fail on an instance with insufficient RAM.

- Review IAM Permissions: Confirm that the IAM role associated with your compute environment has the necessary permissions to read from input S3 buckets and write to output S3 buckets [34].

- Inspect the Workflow Definition: For tools like Nextflow, check the

nextflow.logfile for errors in workflow definition or task execution.

Problem 3: High Costs Despite Low Compute Utilization

- Symptoms: The monthly cloud bill is unexpectedly high, but monitoring shows compute instances are idle for long periods.

- Solution:

- Implement Auto-Scaling: Configure your compute cluster (e.g., in AWS Batch) to automatically terminate instances when the job queue is empty. A common mistake is leaving a fixed-size cluster running 24/7 [40] [34].

- Use Spot Instances/Preemptible VMs: For fault-tolerant batch jobs, use AWS Spot Instances or GCP Preemptible VMs. These can reduce compute costs by 60-90% compared to on-demand prices [34].

- Optimize Storage: Apply Amazon S3 Lifecycle Policies to automatically transition old results and raw data that are no longer actively analyzed to cheaper storage classes like S3 Glacier [34].

Problem 4: Difficulty Querying Large Variant Call Datasets

- Symptoms: Researchers struggle to perform cohort-level analysis on hundreds of VCF files; queries are slow and require complex scripting.

- Solution:

- Transform your variant data into a structured, query-optimized format. Use a solution that converts VCF files into Apache Iceberg tables stored in Amazon S3 Tables. Once in this format, you can use standard SQL with Amazon Athena to run fast, complex queries across millions of variants without managing databases [36].

- Leverage AI-powered tools like an agent built on Amazon Bedrock to allow researchers to ask questions of the data in natural language, bypassing the need for SQL expertise entirely [36].

Experimental Protocols & Benchmarking

Protocol: Benchmarking Ultra-Rapid NGS Pipelines on Google Cloud Platform

This protocol outlines the steps to benchmark germline variant calling pipelines, such as Sentieon DNASeq and NVIDIA Clara Parabricks, on GCP. This is critical for chemogenomic research where rapid turnaround of genomic data can influence experimental directions [37].

1. Prerequisites:

- A GCP account with billing enabled.

- Basic familiarity with the bash shell and GCP Console.

- Valid software licenses if required (e.g., for Sentieon).

2. Virtual Machine Configuration: Benchmarking requires dedicated VMs tailored to each pipeline's hardware needs. The table below summarizes a tested configuration for cost-effective performance [37].

Table: GCP VM Configuration for NGS Pipeline Benchmarking

| Pipeline | Machine Series & Type | vCPUs | Memory | GPU | Approx. Cost/Hour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentieon DNASeq | N1 Series, n1-highcpu-64 |

64 | 57.6 GB | None | $1.79 |

| Clara Parabricks | N1 Series, custom (48 vCPU) |

48 | 58 GB | 1 x NVIDIA T4 | $1.65 |

3. Step-by-Step Execution on GCP:

- VM Creation: In the GCP Console, navigate to Compute Engine > VM Instances. Click "CREATE INSTANCE".

- Configuration: Name the VM and select a region/zone. For the Sentieon VM, select the

n1-highcpu-64machine type. For Parabricks, create a custom machine type with 48 vCPUs and 58 GB memory, and then add a NVIDIA T4 GPU. - Software Installation: Use the

gcloudcommand-line tool or SCP to transfer the pipeline software and license files to the VM. - Data Preparation: Download a publicly available WGS or WES FASTQ sample (e.g., from the SRA) to the VM's local SSD or attached persistent disk for fast I/O.

- Pipeline Execution: Run each pipeline with its default parameters on the same sample. Example commands for a WGS sample:

- Sentieon:

sentieon driver -t <num_threads> -i <input_fastq> -r <reference_genome> --algo ... output.vcf - Parabricks:

parabricks run --fq1 <read1.fastq> --fq2 <read2.fastq> --ref <reference.fa> --out-dir <output_dir> germline

- Sentieon:

- Data Collection: Record the total runtime, CPU utilization, and memory usage for each pipeline using GCP's monitoring tools or system commands like

time.

4. Expected Results and Analysis: The benchmark will yield quantitative data on performance and cost. The table below provides sample results from a study using five WGS samples [37].

Table: Benchmarking Results for Ultra-Rapid NGS Pipelines on GCP

| Pipeline | Average Runtime per WGS Sample | Average Cost per WGS Sample | Key Hardware Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sentieon DNASeq | ~2.5 hours | ~$4.48 | High CPU utilization, optimized for parallel processing. |

| Clara Parabricks | ~2.0 hours | ~$3.30 | High GPU utilization, leveraging parallel processing on the graphics card. |

Workflow Diagram: End-to-End Scalable Genomic Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key cloud services involved in a scalable genomic analysis pipeline, from data ingestion to final interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details the essential software, services, and data resources required to conduct large-scale genomic analysis in the cloud.

Table: Essential Resources for Cloud-Based Genomic Analysis

| Category | Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Core Analysis Software | Sentieon DNASeq | A highly optimized, CPU-based pipeline for secondary analysis (alignment, deduplication, variant calling) that provides results equivalent to GATK Best Practices with significantly faster speed [37]. |

| NVIDIA Clara Parabricks | A GPU-accelerated suite of tools for secondary genomic analysis, leveraging parallel processing to dramatically reduce runtime for tasks like variant calling [37]. | |

| GATK (Genome Analysis Toolkit) | A industry-standard toolkit for variant discovery in high-throughput sequencing data, often run within cloud environments [33]. | |

| Workflow Orchestration | Nextflow | A workflow manager that enables scalable and reproducible computational pipelines. It seamlessly integrates with cloud platforms like AWS and GCP, allowing pipelines to run across thousands of cores [34] [35]. |

| Cromwell | An open-source workflow execution engine that supports the WDL (Workflow Description Language) and is optimized for cloud environments [33] [34]. | |

| Cloud Services | AWS HealthOmics | A purpose-built service to store, query, and analyze genomic and other omics data, with native support for workflow languages like Nextflow and WDL [36]. |

| Amazon S3 / Google Cloud Storage | Durable, scalable, and secure object storage for housing input data, intermediate files, and final results from genomic workflows [34] [39]. | |

| AWS Batch / GCP Batch | Fully managed batch computing services that dynamically provision the optimal quantity and type of compute resources to run jobs [34] [39]. | |

| Reference Data | Reference Genomes (GRCh38) | The standard reference human genome sequence used as a baseline for aligning sequencing reads and calling variants. |

| ClinVar | A public archive of reports detailing the relationships between human genetic variations and phenotypes, with supporting evidence used for annotating and interpreting variants [36]. | |

| Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) | A tool that determines the functional consequences of genomic variants (e.g., missense, synonymous) on genes, transcripts, and protein sequences [36]. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This hub provides targeted support for researchers addressing the computational demands of large-scale chemogenomic NGS data. The guides below focus on specific, high-impact issues in variant calling and polygenic risk scoring.

DeepVariant Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: The pipeline fails with a TensorFlow error: "Check failed: -1 != path_length (-1 vs. -1)" and "Fatal Python error: Aborted". What should I do?

- Problem Overview: This is a known environment or dependency conflict issue, often occurring during the

call_variantsstep when the model loads [41]. It can be related to the TensorFlow library version or its interaction with the underlying operating system. - Diagnostic Steps:

- Check the full error log for any preceding warnings, such as end-of-life messages for libraries like TensorFlow Addons [41].

- Verify that the paths to all input files (BAM, FASTA) are correct and accessible within your container environment.

- Solution:

- Primary Action: Use a supported and updated version of DeepVariant. The error was reported on DeepVariant v1.6.1 [41]. Check the official repository for newer releases that contain bug fixes.

- Alternative Approach: If updating is not possible, ensure you are using a compatible and stable version of TensorFlow as required by your specific DeepVariant version. The Singularity container should ideally manage these dependencies.

- Prevention: Always use the standard Docker or Singularity images provided by the DeepVariant team to ensure a consistent and tested software environment.

Q2: I get a "ValueError: Reference contigs span ... bases but only 0 bases (0.00%) were found in common". Why does this happen?

- Problem Overview: This critical error occurs when the reference genome used to create the input BAM file does not match the reference genome provided to DeepVariant [42]. The tool detects no common genomic contigs between the two files.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Use

samtools view -H your_file.bamto inspect the@SQlines (contig names) in your BAM header. - Use

grep ">" your_reference.fastato see the contig names in your reference FASTA file. - Compare the outputs; you will likely find mismatches in contig names (e.g., "chr1" vs. "1") [42].

- Use

- Solution:

- Immediate Fix: Ensure consistency. Re-align your sequencing reads using the correct

your_reference.fastafile, or obtain the correct reference genome that matches your BAM file's build. - Troubleshooting Tip: This is a common issue when switching between different human reference builds (like hg19 vs. GRCh38) or when working with non-human data. Always double-check reference genome versions at the start of your project [42].

- Immediate Fix: Ensure consistency. Re-align your sequencing reads using the correct

Q3: The "make_examples" step is extremely slow or runs out of memory. How can I optimize this?

- Problem Overview: The

make_examplesstage is the most computationally intensive and memory-hungry part of DeepVariant, requiring significant resources for large genomes and high-coverage data [43]. - Diagnostic Steps:

- Monitor your system resources (e.g., using

toporhtop) during the job to confirm it is memory-bound (slowed by swapping) or CPU-bound. - Check the logging output from DeepVariant to see the number of shards being processed and their progress.

- Monitor your system resources (e.g., using

- Solution:

- Increase Memory: The memory requirement for

make_examplesis approximately 10-15x the size of your input BAM file [43]. For a 30 GB BAM file, allocate 300-450 GB of RAM. - Parallelize the Task: Use the

--num_shardsoption to break the work into multiple parallel tasks. For example, on a cluster with 32 cores, you can set--num_shards=32to significantly speed up processing [41]. - Adjust Region: Use the

--regionsflag with a BED file to process only specific genomic intervals of interest, which is highly useful for targeted sequencing or exome data [43].

- Increase Memory: The memory requirement for

Table: Common DeepVariant Errors and Solutions

| Error Symptom | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| TensorFlow "path_length" error & crash [41] | Dependency or environment conflict | Use an updated, stable DeepVariant version and official container image. |

| "0 bases in common" between reference & BAM [42] | Reference genome mismatch | Re-align FASTQ or obtain the correct reference to ensure contig names match. |

| make_examples slow/OOM (Out-of-Memory) | High memory demand for large BAMs [43] | Allocate 10-15x BAM file size in RAM; use --num_shards for parallelization [41] [43]. |

| Pipeline fails on non-human data | Default settings for human genomes | Ensure reference and BAM are consistent; no specific model change is typically needed for non-human WGS [42]. |

Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) Implementation & FAQ

Q1: How do I choose the right Polygenic Risk Score for my study on a specific disease?

- Problem Overview: There is no single, universally standardized PRS for most diseases. Different scores, built with varying methods and GWAS summary statistics, can classify individuals into different risk categories, leading to discordant results [44].

- Guidelines:

- Consult the Polygenic Score Catalog (PGS Catalog): This is a primary, regularly updated repository of published PRS for a wide range of diseases and traits [44].

- Evaluate Performance Metrics: Prioritize scores that have been validated in independent cohorts. Look for metrics like Area Under the Curve (AUC), which indicates the score's ability to discriminate between cases and controls. For example, a breast cancer PRS combined with clinical factors achieved an AUC of 0.677, a significant improvement over clinical factors alone (AUC 0.536) [44].

- Check Ancestry Match: The vast majority of GWAS data (~91%) is from individuals of European ancestry [44]. A PRS developed in one ancestry group often has degraded performance and may overestimate risk in other ancestry groups [44]. Always check the ancestral background of the development cohort and seek out ancestry-matched or multi-ancestry PRS (MA-PRS) where possible.

Q2: What are the key computational and data management challenges when calculating PRS for a large cohort?

- Problem Overview: PRS calculation itself is less computationally intense than variant calling, but it depends on the management of large genomic datasets and the integration of multiple data sources [3].

- Key Challenges & Solutions:

- Data Transfer and Storage: Moving terabytes of genotyping or sequencing data (e.g., VCF files) is a major bottleneck. The most efficient solution is often to house data centrally in the cloud and bring computations to the data [3].

- Standardization of Data Formats: Working with data from different centers in different formats wastes time. Using standardized file formats (e.g., VCF, BCF) and interoperable toolkits (e.g., PLINK, bcftools) is crucial [3] [45].

- Integration with Clinical Data: The most accurate risk models combine PRS with clinical risk factors [44] [46]. This requires robust data pipelines to merge and manage genomic and clinical data securely.

Table: Key Considerations for Clinical PRS Implementation

| Consideration | Challenge | Current Insight & Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Ancestral Diversity | Poor performance in non-European populations due to GWAS bias [44]. | Use ancestry-informed or MA-PRS; simple corrections can improve accuracy in specific groups [44]. |

| Risk Communication | Potential for misunderstanding complex genetic data [46]. | Communicate absolute risk (e.g., 17% lifetime risk) instead of relative risk (1.5x risk) [44]. |

| Clinical Integration | How to incorporate PRS into existing clinical workflows and decision-making [46]. | Combine PRS with monogenic variants and clinical factors in integrated risk models (e.g., CanRisk) [44]. |

| Regulatory Standardization | No universal standard for PRS development or validation [44]. | Rely on well-validated scores from peer-reviewed literature and the PGS Catalog; transparency in methods is key [44]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Item | Function & Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DeepVariant | A deep learning-based variant calling pipeline that converts aligned sequencing data (BAM) into variant calls (VCF/GVCF) [41] [43]. | Best run via Docker/Singularity for reproducibility. Model types: WGS, WES, PacBio [43]. |

| Bcftools | A versatile suite of utilities for processing, filtering, and manipulating VCF and BCF files [45]. | Used for post-processing variant calls, e.g., bcftools filter to remove low-quality variants [45]. |

| SAM/BAM Files | The standard format for storing aligned sequencing reads [10]. | Must be sorted and indexed (e.g., with samtools sort/samtools index) for use with most tools, including DeepVariant [45]. |

| VCF/BCF Files | The standard format for storing genetic variants [45]. | BCF is the compressed, binary version, which is faster to process [45]. |

| Polygenic Score (PGS) Catalog | A public repository of published polygenic risk scores [44]. | Essential for finding and comparing validated PRS for specific diseases and traits. |

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | The reference sequence to which reads are aligned and variants are called against [42]. | Critical that the version (e.g., GRCh38, hs37d5) matches the one used for read alignment [43] [42]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Typical Variant Calling Workflow with DeepVariant and Bcftools

This protocol details the steps from an aligned BAM file to a filtered set of high-confidence variants, integrating both DeepVariant and bcftools for a robust analysis [45].

1. Input Preparation

- Inputs: A coordinate-sorted BAM file and its index (

.bai), the reference genome in FASTA format and its index (.fai). - Software: DeepVariant (via Docker/Singularity), Bcftools.

2. Variant Calling with DeepVariant

- Run DeepVariant using the command appropriate for your data type (e.g.,

--model_type=WGSfor whole-genome data). This generates a VCF file containing all variant calls and reference confidence scores [41] [43]. - Example Command:

3. Post-processing and Filtering with Bcftools

- Step 1: Normalize Variants. Left-aligns and normalizes indels, which is critical for accurate counting and filtering. This step can merge and realign variants [45].

- Step 2: Apply Filters. Remove low-quality variants using hard filters. The specific thresholds should be tuned for your dataset. This command removes variants with a quality score below 30 or a read depth below 15 [45].

4. Output Analysis

- The final output,

filtered_variants.bcf, contains your high-confidence variant set. You can obtain a variant count withbcftools view -H filtered_variants.bcf | wc -l[45].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

DeepVariant Troubleshooting Logic

PRS Implementation Workflow

Multi-omics research represents a transformative approach in biological sciences that integrates data from various molecular layers—such as genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics—to provide a comprehensive understanding of biological systems. The primary goal is to study complex biological processes holistically by combining these data types to highlight the interrelationships of biomolecules and their functions [47]. This integrated approach helps bridge the information flow from one omics level to another, effectively narrowing the gap from genotype to phenotype [47].

The analysis of multi-omics data, especially when combined with clinical information, has become crucial for deriving meaningful insights into cellular functions. Integrated approaches can combine individual omics data either sequentially or simultaneously to understand molecular interplay [47]. By studying biological phenomena holistically, these integrative approaches can significantly improve the prognostics and predictive accuracy of disease phenotypes, ultimately contributing to better treatment and prevention strategies [47].

Key Data Repositories for Multi-Omics Research

Several publicly available databases provide multi-omics datasets that researchers can leverage for integrated analyses. The table below summarizes the major repositories:

Table: Major Multi-Omics Data Repositories

| Repository Name | Primary Focus | Available Data Types |

|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [47] | Cancer | RNA-Seq, DNA-Seq, miRNA-Seq, SNV, CNV, DNA methylation, RPPA |

| Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) [47] | Cancer (proteomics corresponding to TCGA cohorts) | Proteomics data |

| International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC) [47] | Cancer | Whole genome sequencing, somatic and germline mutation data |

| Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) [47] | Cancer cell lines | Gene expression, copy number, sequencing data, pharmacological profiles |

| Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium (METABRIC) [47] | Breast cancer | Clinical traits, gene expression, SNP, CNV |

| TARGET [47] | Pediatric cancers | Gene expression, miRNA expression, copy number, sequencing data |

| Omics Discovery Index (OmicsDI) [47] | Consolidated datasets from multiple repositories | Genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics |

Multi-Omics Integration Strategies and Tools

Integration strategies are broadly categorized based on whether the data is matched (profiled from the same cell) or unmatched (profiled from different cells) [48]. The choice of integration method depends heavily on this distinction.

Types of Integration

- Matched Integration: Also known as vertical integration, this approach merges data from different omics within the same set of samples, using the cell as the anchor to bring these omics together [48]. This is possible with technologies that profile multiple distinct modalities from within a single cell.

- Unmatched Integration: Referred to as diagonal integration, this strategy integrates different omics from different cells or different studies [48]. Since the cell cannot serve as an anchor, these methods project cells into a co-embedded space or non-linear manifold to find commonality between cells in the omics space.

- Mosaic Integration: This alternative to diagonal integration is used when experimental designs have various combinations of omics that create sufficient overlap across samples [48]. Tools like COBOLT and MultiVI can integrate data in this mosaic fashion.

Computational Tools for Integration

A wide array of computational tools has been developed to address multi-omics integration challenges. The table below categorizes these tools based on their integration capacity:

Table: Multi-Omics Integration Tools and Methodologies

| Tool Name | Year | Methodology | Integration Capacity | Data Types Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matched Integration Tools | ||||

| MOFA+ [48] | 2020 | Factor analysis | Matched | mRNA, DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility |

| totalVI [48] | 2020 | Deep generative | Matched | mRNA, protein |

| Seurat v4 [48] | 2020 | Weighted nearest-neighbour | Matched | mRNA, spatial coordinates, protein, accessible chromatin |

| SCENIC+ [48] | 2022 | Unsupervised identification model | Matched | mRNA, chromatin accessibility |

| Unmatched Integration Tools | ||||

| Seurat v3 [48] | 2019 | Canonical correlation analysis | Unmatched | mRNA, chromatin accessibility, protein, spatial |

| GLUE [48] | 2022 | Variational autoencoders | Unmatched | Chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation, mRNA |

| LIGER [48] | 2019 | Integrative non-negative matrix factorization | Unmatched | mRNA, DNA methylation |

| Pamona [48] | 2021 | Manifold alignment | Unmatched | mRNA, chromatin accessibility |

Experimental Workflows and Visualization

The integration of multiple omics data types follows specific computational workflows that vary based on the nature of the data and the research objectives. The diagram below illustrates a generalized workflow for multi-omics data integration:

Diagram: Multi-Omics Integration Workflow showing the process from raw data to biological insights.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful multi-omics research requires specific computational tools and resources. The table below details essential components of the multi-omics research toolkit:

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for Multi-Omics Research

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Examples/Formats |

|---|---|---|

| Data Storage Formats | Standardized formats for efficient data storage and processing | FASTQ, BAM, VCF, HDF5 [10] |

| Workflow Management | Maintain reproducibility, portability, and scalability in analysis | Nextflow, Snakemake, Cromwell [10] |

| Container Technology | Ensure consistent computational environments across platforms | Docker, Singularity, Podman [10] |

| Cloud Computing Platforms | Provide scalable computational resources for large datasets | AWS, Google Cloud Platform, Microsoft Azure [3] [10] |

| Quality Control Tools | Assess data quality before integration | FastQC, MultiQC, Qualimap |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Data Management and Preprocessing Issues

Q: How can I handle the large-scale data transfer and storage challenges associated with multi-omics studies?