Strategies for Reducing Host DNA Background in Metagenomic NGS: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

High host DNA background remains a significant challenge in metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS), particularly in clinical samples like blood, respiratory secretions, and tissues where host content can exceed 99%.

Strategies for Reducing Host DNA Background in Metagenomic NGS: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

High host DNA background remains a significant challenge in metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS), particularly in clinical samples like blood, respiratory secretions, and tissues where host content can exceed 99%. This comprehensive review explores current methodologies for host DNA depletion, comparing physical, enzymatic, and bioinformatic approaches. We examine the impact of host depletion on diagnostic sensitivity, microbial read enrichment, and community representation across diverse sample types. Recent advancements including novel filtration technologies and optimized DNA extraction methods are evaluated for their efficacy in improving pathogen detection while preserving microbial integrity. This article provides researchers and clinicians with evidence-based guidance for selecting appropriate host depletion strategies to enhance mNGS performance in infectious disease diagnostics and microbiome studies.

The Host DNA Challenge: Understanding the Fundamental Barrier in Metagenomic NGS

The Critical Impact of Host DNA on Sequencing Efficiency and Sensitivity

FAQs: Understanding Host DNA in NGS

Q1: Why is host DNA a significant problem in metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS)? Host DNA is a major problem because it consumes the vast majority of sequencing reads, leaving limited capacity for detecting microbial pathogens. In samples like blood and respiratory secretions, host DNA can constitute over 99% of the total sequenced DNA [1] [2]. This overwhelming background leads to reduced sensitivity for identifying low-abundance microbes and significantly increases the cost and depth of sequencing required to obtain meaningful microbial data [3] [4].

Q2: Which sample types are most affected by high host DNA content? The proportion of host DNA varies significantly by sample type [3]:

- High host DNA (>90%): Blood, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), sputum, saliva, and nasopharyngeal swabs [1] [2] [4].

- Low host DNA (<10%): Stool samples [3].

Q3: What is the relationship between host DNA content and sequencing depth? As host DNA content increases, the required sequencing depth to achieve sufficient microbial genome coverage increases exponentially. Studies have shown that in samples with 90% host DNA, a reduction in sequencing depth majorly impacts sensitivity, increasing the number of undetected microbial species. Even with a fixed depth of 10 million reads, microbiome profiling becomes increasingly inaccurate as host DNA levels rise [3] [4].

Q4: Can I use bioinformatics to remove host DNA sequences? Yes, bioinformatic tools like KneadData (which uses Bowtie2) can map and remove reads that align to the host genome after sequencing [3] [4]. However, this is a post-sequencing corrective measure. It does not solve the fundamental problem of wasted sequencing resources on non-informative host reads, making pre-sequencing host depletion a more efficient strategy for enriching microbial signals [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Microbial Read Counts in mNGS

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Using high-host content samples (e.g., blood, BAL) without depletion. | Implement a pre-sequencing host depletion method tailored to your sample type [1] [2]. |

| Host Depletion Method | Method is inefficient, labor-intensive, or alters microbial composition. | Evaluate advanced methods like the ZISC-based filtration, which showed >99% WBC removal without affecting microbial integrity [1] [5]. |

| DNA Input | Using cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from plasma for septic samples. | For sepsis, use genomic DNA (gDNA) from cell pellets combined with host cell depletion. One study showed gDNA-based mNGS detected pathogens in 100% of samples, outperforming cfDNA-based methods [1]. |

| Sequencing Depth | Inadequate sequencing depth for the level of host DNA contamination. | Increase sequencing depth significantly for samples with >90% host DNA. For context, one clinical study sequenced at least 10 million reads per sample on a NovaSeq 6000 [1] [3]. |

Problem: Contamination in mNGS Workflow

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lab Layout | Pre- and post-PCR areas are not physically separated. | Designate and use distinct areas for sample preparation, PCR setup, and post-PCR analysis. Restrict equipment (pipettes, lab coats) to these dedicated areas [6]. |

| Reagents | Reagents are contaminated or cross-used. | Prepare and store reagents separately. Aliquot reagents in small portions designated for pre- or post-PCR use only [6]. |

| Practice | Amplicons from previous runs contaminate new reactions. | Always use pipette tips with aerosol filters. Never bring reagents or equipment from a post-PCR area back to a pre-PCR area [6]. |

| Controls | Contamination is not detected early. | ALWAYS include a negative control reaction (using ultrapure water instead of template DNA) in every run to check for contamination [6]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: ZISC-Based Filtration for Host Depletion in Blood

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study that optimized mNGS for sepsis diagnosis [1].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Collect whole blood sample (e.g., 4 mL) in an appropriate anticoagulant tube.

- Optionally, spike with an internal reference control (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control) to monitor microbial recovery.

2. Host Cell Depletion Filtration:

- Secure the novel ZISC-based fractionation filter (e.g., Devin filter from Micronbrane) onto a syringe.

- Transfer the blood sample into the syringe.

- Gently depress the plunger to push the blood through the filter into a clean collection tube (e.g., 15 mL Falcon tube).

- The filter achieves >99% white blood cell (WBC) removal while allowing bacteria and viruses to pass through unimpeded.

3. Plasma and Cell Pellet Separation:

- Centrifuge the filtered blood at low speed (e.g., 400g for 15 minutes) to isolate the plasma.

- Transfer the plasma to a new tube and perform high-speed centrifugation (e.g., 16,000g) to obtain a microbial cell pellet.

4. DNA Extraction:

- Extract genomic DNA (gDNA) from the microbial cell pellet using a dedicated microbial DNA enrichment kit.

- For comparison, cell-free DNA (cfDNA) can be extracted from the plasma supernatant.

5. Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare mNGS libraries using an Ultra-Low Library Prep Kit.

- Sequence on a platform such as Illumina NovaSeq 6000, aiming for a minimum of 10 million reads per sample.

Quantitative Data on Host Depletion Efficacy

Table 1: Comparison of Host Depletion Methods on Clinical Samples [1]

| Method | Principle | Host Depletion Efficiency | Key Findings in Clinical Sepsis Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel ZISC Filtration | Physical retention of host WBCs via a zwitterionic coating. | >99% WBC removal [1]. | mNGS with filtered gDNA detected all expected pathogens in 100% (8/8) of samples, with an average of 9351 microbial RPM (reads per million)—a tenfold increase over unfiltered samples (925 RPM) [1]. |

| Differential Lysis (QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit) | Selective lysis of human cells. | Varies by sample type [2]. | More labor-intensive; efficiency lower than novel filtration in side-by-side comparison [1]. |

| Methylated DNA Removal (NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit) | Removal of CpG-methylated host DNA. | Varies by sample type [2]. | Preserved microbial reads but was less efficient than novel filtration [1]. |

Table 2: Impact of Host DNA Percentage and Sequencing Depth on Microbial Detection [3] [4]

| Host DNA in Sample | Sequencing Depth | Impact on Microbial Detection Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | Standard Depth (e.g., 5-10 M reads) | Good sensitivity for most species. |

| 90% | Standard Depth | Decreased sensitivity; increased number of undetected species, particularly low-abundance ones. |

| 90% | Reduced Depth | Major impact on sensitivity; significant loss of microbial species information. |

| 99% | Fixed Depth of 10 M reads | Profiling becomes highly inaccurate due to extremely low effective microbial depth. |

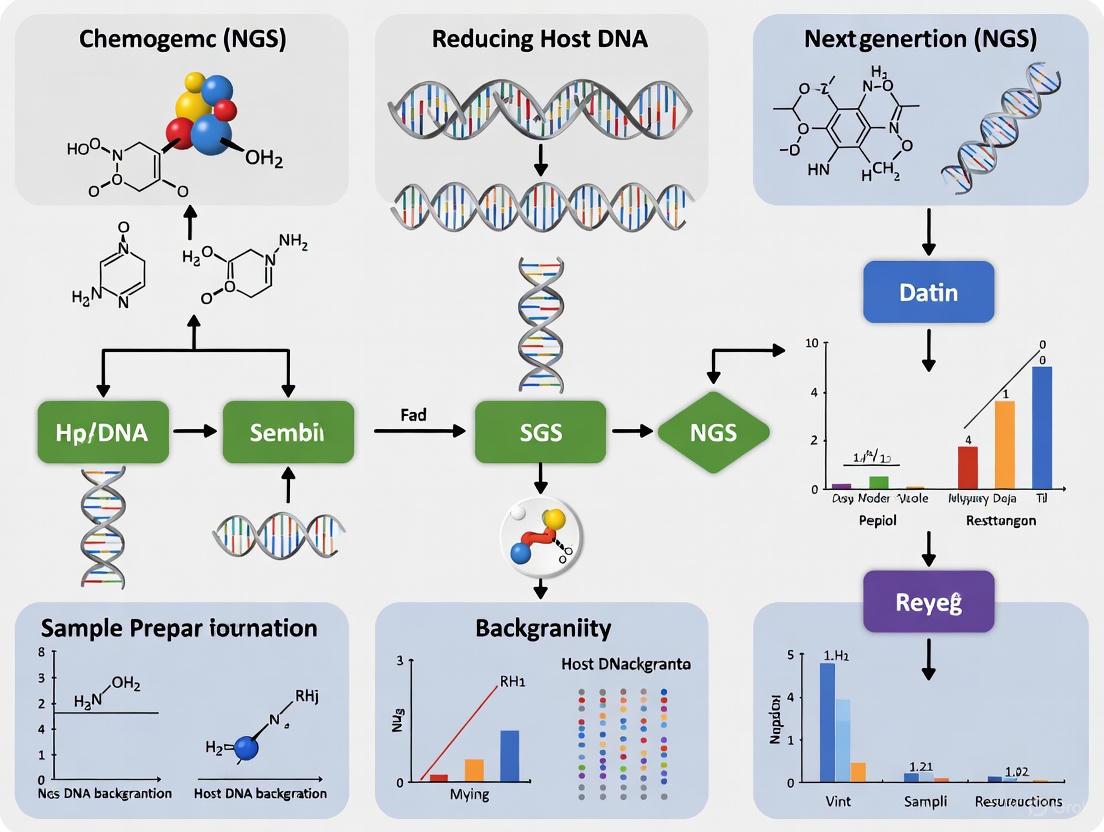

Workflow Diagrams

Host Depletion mNGS Workflow

Host Depletion Decision Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Kits for Host DNA Depletion

| Product Name | Manufacturer | Principle / Function | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Devin Filter (ZISC-based) | Micronbrane | Zwitterionic coating binds and retains host leukocytes physically. | Achieved >99% WBC removal from blood; enabled 10x enrichment of microbial reads in mNGS [1]. |

| QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit | Qiagen | Differential lysis of human cells to enrich for microbial DNA. | One of several methods evaluated for respiratory samples; performance varies by sample matrix [1] [2]. |

| NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit | New England Biolabs | Binds and removes CpG-methylated host DNA, enriching non-methylated microbial DNA. | A post-extraction method compared favorably but was less efficient than novel filtration in one study [1]. |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit | Zymo Research | Chemical and enzymatic degradation of host DNA. | Effectively decreased host DNA in frozen nasal (73.6% decrease) and sputum samples [2]. |

| MolYsis Kit | Molzym | Selective lysis of human cells and degradation of released DNA. | Effective for sputum, decreasing host DNA by 69.6% [2]. |

In chemogenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) research, host DNA contamination represents a significant bottleneck that can compromise data quality and experimental outcomes. Excessive host DNA in samples reduces microbial or target pathogen sequencing depth, increases sequencing costs, and can obscure genuine biological signals. This technical guide addresses the critical need for accurate quantification of host DNA proportions and provides evidence-based strategies for effective host depletion, enabling more sensitive and accurate NGS results in drug discovery and development workflows.

Quantitative Analysis of Host DNA Background

The proportion of host DNA varies significantly across different sample types, directly impacting the effectiveness of downstream NGS applications. The following table summarizes documented host DNA levels across various clinical and experimental samples:

Table 1: Host DNA Proportions Across Sample Types

| Sample Type | Host DNA Proportion | Post-Treatment Host DNA | Enhancement Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood (sepsis patients, gDNA-based mNGS) | High background (average 925 RPM microbial reads) | >10x increase in microbial reads (9351 RPM) | Novel ZISC-based filtration [5] | >99% white blood cell removal; significantly improved pathogen detection [5] |

| Swab specimens (COVID-19 patients) | Variable (impacted SARS-CoV-2 detection sensitivity) | Improved detection rate (92.9% for Ct ≤35) | Host DNA removal via DNA enzyme digestion [7] | Host removal enhanced sensitivity without affecting microbial RNA abundance [7] |

| Bacterial WGS from pure cultures | Contamination present in multiple studies | Taxonomic filtering enabled accurate variant calling | Kraken-based taxonomic classification [8] | 45% of samples in some studies had <90% reads from target organism [8] |

| Therapeutic proteins (CHO host cells) | Residual host cell DNA impurity | Detection limit of 0.1-0.8 ppb | Direct qPCR without DNA extraction [9] | Proteinase K/SDS digestion with Tween 20 to prevent inhibition [9] |

Host DNA Quantification Methods

Accurate quantification of host DNA is essential for assessing sample quality and determining the need for host depletion procedures. The following methods are commonly employed:

Table 2: Host DNA Quantification Methods

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV Absorbance [10] [11] | Measures absorbance at 260nm | Limited sensitivity at low concentrations | Quick, simple, no special reagents | Cannot distinguish between DNA and RNA [10] |

| Fluorescence Dyes (PicoGreen, SYBR Green) [10] [11] | Fluorescent dyes bind dsDNA | High sensitivity for low concentrations | Specific for dsDNA, more sensitive than UV | Requires standard curve, dye-specific [10] |

| qPCR/dPCR [9] [12] | Target-specific amplification | Very high (detection to 0.1 ppb) | Host-specific, extremely sensitive | Requires host-specific primers/probes [9] |

| Capillary Electrophoresis [10] [11] | Size separation with fluorescence | Moderate | Fragment size distribution, automated | Equipment intensive, lower throughput [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Host DNA Assessment and Depletion

Protocol 1: Direct qPCR for Residual Host Cell DNA Quantification

This protocol enables precise quantification of host DNA without extraction steps, adapted from Peper et al. [9]:

- Protein Digestion: Mix sample with proteinase K and SDS to digest therapeutic proteins and release DNA.

- Add Stabilizers: Include Tween 20 and NaCl to minimize precipitation of therapeutic proteins during digestion.

- qPCR Setup: Prepare qPCR mix with 2% (v/v) Tween 20 to counteract SDS inhibition.

- Amplification: Use host-specific primers and probes (e.g., CHO-specific for mammalian cell lines).

- Quantification: Calculate residual DNA against standard curve, with LOD of 0.1-0.8 ppb for most proteins.

This method has been validated according to ICH guidelines and applied to 25 different therapeutic proteins [9].

Protocol 2: Taxonomic Filtering for Bacterial WGS Contamination Removal

For comprehensive removal of contaminant reads in bacterial whole-genome sequencing:

- Taxonomic Classification: Process sequencing reads with Kraken classifier against curated database.

- Filter Implementation: Remove all reads not classified to target genus (e.g., non-Acinetobacter reads for A. baumannii studies).

- Variant Calling: Perform standard mapping and SNP calling on filtered read set.

- Validation: Compare variant profiles before and after filtering to assess contamination impact.

This approach has been shown to eliminate hundreds of false positive and negative SNPs even in slightly contaminated samples [8].

Protocol 3: Host DNA-Removed Metagenomic Sequencing

For swab and clinical specimens requiring pathogen detection:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract total nucleic acid using automated system (e.g., 200μl sample input).

- Host DNA Depletion: Treat with DNA enzyme and buffer to digest DNA and enrich for RNA pathogens.

- Reverse Transcription: Synthesize cDNA from remaining RNA.

- Library Preparation: Use probe-anchored polymer sequencing method for library construction.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence on appropriate platform (e.g., MGSEQ-2000) and remove any residual human reads bioinformatically.

This workflow achieved 92.9% detection rate for SARS-CoV-2 in samples with Ct values ≤35 [7].

Workflow Visualization: Host DNA Management in NGS

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Host DNA Management

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ribo-Zero [13] | rRNA depletion | Reduces rRNA to <1%, maintains transcript representation |

| Proteinase K with SDS [9] | Protein digestion for direct qPCR | Enables residual DNA detection without extraction |

| Kraken Classifier [8] | Taxonomic read classification | Filters contaminant reads at genus/species level |

| ZISC-based Filtration [5] | Physical host cell depletion | >99% WBC removal while preserving microbes |

| PicoGreen/SYBR Green [10] [11] | dsDNA quantification | Fluorometric detection specific to dsDNA |

| DNA Enzyme Treatment [7] | Selective host DNA removal | Digests DNA while preserving RNA pathogens |

| qPCR Host-Specific Primers [9] [12] | Targeted host DNA detection | Enables sensitive residual DNA quantification |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the acceptable threshold for host DNA proportion in NGS samples? The acceptable threshold varies by application. For metagenomic sequencing aiming to detect low-abundance pathogens, host DNA should ideally be reduced to <80% of total reads. Studies show that novel filtration methods can achieve >99% host cell removal, resulting in over tenfold increase in microbial reads [5].

Q2: Can I use UV spectrophotometry (A260/A280) alone to assess host DNA contamination? While UV spectrophotometry provides rapid assessment of nucleic acid purity (ideal A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0 for DNA), it cannot distinguish between host and target DNA, has limited sensitivity at low concentrations, and may miss contamination that doesn't affect the absorbance ratio [10]. For host-specific quantification, qPCR with host-specific primers is recommended [9] [12].

Q3: What is the most effective host depletion method for blood samples? For blood samples, the novel ZISC-based filtration device has demonstrated excellent performance with >99% white blood cell removal across various blood volumes while allowing unimpeded passage of bacteria and viruses. This method achieved an average of 9351 microbial RPM compared to 925 RPM in unfiltered samples in sepsis patient testing [5].

Q4: How does host DNA removal affect the representation of the microbial community? Properly implemented host DNA removal methods specifically target host nucleic acids while preserving microbial composition. Studies comparing workflows with and without host removal found that effective host depletion does not alter the microbial composition, making it suitable for accurate pathogen profiling [5] [7].

Q5: What bioinformatic approaches can help address host DNA contamination? Taxonomic classification tools like Kraken can filter contaminant reads bioinformatically. This approach has been shown to remove hundreds of false positive and negative SNPs even in slightly contaminated samples. For comprehensive contamination removal, combine wet-lab depletion with bioinformatic filtering [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core problem with host DNA in microbial NGS?

Host DNA acts as a major contaminant in metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS). In samples derived from human hosts (e.g., tissues, blood, saliva), the human genome can constitute over 90% of the total DNA sequenced [14] [15]. This overwhelms the microbial signal, leading to two critical issues:

- Obscured Detection: The vast majority of sequencing reads are consumed by host DNA, drastically reducing the number of reads available to identify pathogens or microbiome members, thereby lowering detection sensitivity [3] [16].

- Wasted Resources: Sequencing depth is wasted on uninformative host reads, increasing costs and computational burden without yielding useful microbial data [17] [15].

Q2: Which sample types are most affected by this issue?

The impact of host DNA varies significantly by sample type, primarily due to differences in the microbial-to-host cell ratio.

- High-Host-DNA Samples ( >90% human reads): Saliva, skin swabs, nasal swabs, vaginal swabs, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), and biopsy tissues [14] [15].

- Low-Host-DNA Samples ( <10% human reads): Stool samples [3] [15].

Q3: My 16S rRNA sequencing of colon biopsies shows strange results. Could host DNA be the cause?

Yes. During 16S amplicon sequencing, PCR primers can mis-prime, or mistakenly bind, to similar sequences in the host genome. This generates "host off-target" sequences that are misclassified as bacterial [17]. This is a significant issue with the commonly used V3-V4 primers, where mis-priming to human chromosomes 5, 11, and 17 can lead to false bacterial identifications and obscure true differences in microbiota composition [17].

Q4: What are the main strategies to deplete host DNA?

Strategies can be applied either before DNA extraction ("pre-extraction") or after DNA extraction ("post-extraction").

Pre-extraction Methods: These leverage physical or chemical differences between host and microbial cells.

- Selective Lysis: Using mild detergents (e.g., saponin) or osmotic lysis to break open fragile human cells while leaving robust microbial cells with cell walls intact [14] [15].

- Nuclease Treatment: Adding DNase enzymes to degrade the exposed host DNA after lysis. The intact microbes are then purified for DNA extraction [18] [15].

- Propidium Monoazide (PMA) Treatment: Following selective lysis, PMA dye penetrates damaged host cells, binds to DNA, and upon light exposure, permanently cross-links it, preventing its amplification in downstream steps [14].

Post-extraction Methods: These exploit genomic differences.

- Methylation-Based Capture: Eukaryotic DNA is heavily methylated. Kits using methyl-binding domain (MBD) proteins can capture and remove this methylated host DNA, leaving behind relatively unmethylated microbial DNA [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Sensitivity for Microbial Pathogens in BALF Samples

Potential Cause: Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples are typically dominated by host DNA (>95%), which can mask the signal from intracellular pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis [16].

Solutions:

- Implement a host depletion protocol. A saponin-based host DNA depletion assisted (HDA) method has been shown to significantly improve results.

- Follow this optimized HDA-mNGS protocol for BALF [16]:

- Sample Pre-treatment: Add Sputasol to the BALF sample and incubate at room temperature for 2-5 minutes.

- Centrifugation: Pellet the microbial cells.

- Selective Lysis & DNase Treatment: Resuspend the pellet and lyse the cells. Then, treat with a salt-active nuclease (e.g., HL-SAN) which is highly effective at degrading host DNA under high-salt conditions [18].

- DNA Extraction & Sequencing: Proceed with DNA extraction using a kit like the TIANamp Micro DNA Kit, followed by library preparation and sequencing.

- Expected Outcome: This method increased the sensitivity for diagnosing pulmonary tuberculosis from 51.2% (conventional mNGS) to 72.0% and provided up to a 16-fold increase in MTB genome coverage [16].

Problem: High Host DNA Background in Saliva Metagenomics

Potential Cause: Saliva contains large amounts of human epithelial cells and extracellular host DNA, routinely resulting in >90% human sequencing reads [14].

Solutions:

- Apply a simple osmotic lysis and PMA (lyPMA) treatment.

- Detailed lyPMA Protocol [14]:

- Resuspend the saliva pellet in pure water to osmotically lyse mammalian cells.

- Add PMA to a final concentration of 10 µM and incubate in the dark for 5 minutes.

- Place the sample on ice and expose it to a 650-W halogen light source for 2 minutes to photo-activate the PMA.

- Proceed with standard DNA extraction.

- Expected Outcome: This cost-effective method reduced host-derived sequencing reads from 89.29% in untreated samples to 8.53%, with minimal taxonomic bias [14].

The following table quantifies how increasing levels of host DNA reduce the sensitivity of Whole Metagenome Sequencing (WMS) for detecting microbial species.

Table 1: Impact of Host DNA Proportion and Sequencing Depth on Microbial Detection Sensitivity in WMS [3]

| Proportion of Host DNA | Sequencing Depth | Key Impact on Microbial Profiling |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | Variable | Minimal impact; high sensitivity for most species. |

| 90% | Standard Depth (~5-10M reads) | Decreased sensitivity; failure to detect very low and low-abundance species. |

| 90% | Reduced Depth | Major impact; significant increase in the number of undetected species. |

| 99% | Fixed Depth (10M reads) | Highly inaccurate and incomplete profiling due to insufficient microbial reads. |

Table 2: Comparison of Host DNA Depletion Methods

| Method | Principle | Best For | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osmotic Lysis + PMA (lyPMA) [14] | Selective lysis of host cells followed by photo-induced cross-linking of free DNA. | Fresh or frozen saliva, other host-derived samples. | Cost-effective, rapid (<5 min hands-on), low taxonomic bias. | Optimized for specific sample types. |

| Selective Lysis + Salt-Active Nuclease (e.g., HL-SAN) [16] [18] | Selective lysis followed by enzymatic degradation of host DNA in high-salt buffers. | BALF, sputum, wound swabs (targeting robust pathogens). | Highly efficient (1000-fold reduction in host DNA), robust, proven in clinical workflows. | High salt conditions may not be suitable for fragile enveloped viruses. |

| Methylation-Based Depletion [15] | Binding and removal of methylated eukaryotic DNA with MBD-bound beads. | Various samples where microbial DNA is largely unmethylated. | Post-extraction method; does not require intact cells. | Bias against microbes with methylated genomes or AT-rich genomes [14]. |

Workflow Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting a host DNA depletion strategy.

Diagram 1: Decision Workflow for Host DNA Depletion Strategy Selection

This diagram outlines the general workflow for the pre-extraction host DNA depletion method using selective lysis and nuclease treatment.

Diagram 2: Pre-extraction Host DNA Depletion Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Host DNA Depletion

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Host DNA Depletion Protocols

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Principle | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Saponin | A non-ionic detergent for selective lysis of mammalian cell membranes without disrupting microbial cell walls [15]. | Used in HDA-mNGS protocol for BALF samples [16]. |

| Salt-Active Nuclease (HL-SAN) | A nuclease that achieves optimal activity under high-salt conditions, effectively degrading host DNA after lysis. | ArcticZymes HL-SAN; used in multiple clinical metagenomic studies [16] [18]. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | A DNA intercalating dye that penetrates only membrane-compromised cells. Upon light exposure, it covalently cross-links DNA, blocking PCR amplification [14]. | Used in the lyPMA protocol for saliva samples [14]. |

| Methyl-Binding Domain (MBD) Kits | Post-extraction method that uses MBD proteins bound to magnetic beads to capture and remove methylated host DNA. | NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit [14] [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is host DNA background a major problem in chemogenomic NGS studies of pathogens? The overwhelming abundance of host DNA in samples consumes the majority of sequencing capacity, leaving few reads for detecting pathogenic organisms. In blood samples, the high concentration of human DNA can severely limit the sensitivity of metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) for pathogen detection [5] [19].

Q2: What are the main methods to reduce host DNA background? There are two primary approaches: (1) Pre-extraction methods that physically remove host cells (e.g., white blood cells) before DNA extraction, using techniques like differential lysis or novel filtration devices, and (2) Post-extraction methods that selectively remove or deplete host DNA after extraction, for example, by exploiting differences in DNA methylation patterns [5] [19].

Q3: How does whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) mNGS compare to cell-free DNA (cfDNA) mNGS for pathogen detection? wcDNA mNGS demonstrates significantly higher sensitivity for pathogen detection in clinical body fluid samples. One study reported a concordance rate with culture results of 63.33% for wcDNA mNGS versus 46.67% for cfDNA mNGS [20]. Furthermore, the mean proportion of host DNA in wcDNA mNGS (84%) was significantly lower than in cfDNA mNGS (95%) [20].

Q4: What are common sequencing preparation failures and their causes? Common issues include low library yield, adapter contamination, and over-amplification artifacts. Root causes often involve poor input DNA/RNA quality, contaminants inhibiting enzymes, inaccurate quantification, inefficient adapter ligation, or overly aggressive purification leading to sample loss [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Microbial Read Counts Due to High Host DNA Background

| Observed Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low percentage of microbial reads despite high total sequencing reads. | Inefficient host cell depletion. | Check pre-filtration and post-filtration cell counts; assess host DNA percentage in sequenced data. | Implement a robust host depletion method, such as the ZISC-based filtration, which can achieve >99% white blood cell removal [5] [19]. |

| Inconsistent pathogen detection sensitivity. | Reliance on cell-free DNA (cfDNA). | Compare microbial read counts from cfDNA vs. whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) from cell pellets. | Switch to a gDNA-based mNGS workflow from cell pellets, which is more effectively enhanced by host depletion methods [19]. |

| High host DNA percentage in wcDNA mNGS. | Suboptimal sample processing. | Review centrifugation protocols for cell pellet preparation. | Optimize the centrifugation steps to ensure effective separation of microbial cells from host components in the sample [20]. |

Problem: General NGS Library Preparation Failures

| Observed Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low library yield. | Poor input quality or contaminants (e.g., phenol, salts). | Check nucleic acid purity via spectrophotometry (A260/A280 and A260/230 ratios). A ratio of ~1.8 is desirable for DNA [22]. Re-purify input sample; use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) instead of UV absorbance alone [21]. | |

| Adapter-dimer contamination (sharp peak ~70-90 bp). | Suboptimal adapter ligation conditions; inefficient purification. | Analyze library profile using an instrument like BioAnalyzer or TapeStation [21]. | Titrate adapter-to-insert molar ratio; optimize bead-based cleanup parameters to remove short fragments [21]. |

| Over-amplification artifacts; high duplication rate. | Too many PCR cycles during library amplification. | Review library amplification protocol and cycle number. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles; amplify from leftover ligation product rather than over-cycling a weak product [21]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

This protocol details a novel pre-extraction method to deplete host white blood cells.

- Sample Preparation: Collect whole blood using standard phlebotomy techniques. Blood samples should be processed fresh for optimal results.

- Filtration Setup: Securely connect the novel ZISC-based fractionation filter (e.g., Devin filter) to a syringe.

- Host Cell Depletion: Transfer approximately 4 mL of whole blood into the syringe. Gently depress the plunger to push the blood sample through the filter into a clean collection tube. This step removes >99% of white blood cells while allowing bacteria and viruses to pass through unimpeded.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the filtered blood at low speed (e.g., 400g for 15 min) to isolate plasma. Subject the plasma to high-speed centrifugation (e.g., 16,000g) to obtain a microbial cell pellet.

- DNA Extraction: Proceed with microbial DNA extraction from the pellet using a commercial kit.

This protocol allows researchers to compare the performance of two primary mNGS approaches.

- Sample Processing: Centrifuge clinical body fluid samples at 20,000 × g for 15 minutes.

- cfDNA Extraction: Extract cell-free DNA from 400 μL of supernatant using a specialized cfDNA kit (e.g., VAHTS Free-Circulating DNA Maxi Kit).

- wcDNA Extraction: Add lysis beads to the retained precipitate and shake vigorously to facilitate cell lysis. Extract whole-cell DNA from the precipitate using a standard DNA mini kit (e.g., Qiagen DNA Mini Kit).

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare DNA libraries for both cfDNA and wcDNA. Sequence on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) with at least 10 million reads per sample.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Analyze data to determine the proportion of host vs. microbial reads and identify reportable pathogens using established criteria.

The table below summarizes key findings from recent studies comparing different methods.

| Method | Host DNA Proportion | Sensitivity / Concordance with Culture | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| wcDNA mNGS | Mean: 84% [20] | 74.07% Sensitivity; 63.33% Concordance [20] | Higher sensitivity for pathogen detection [20]. |

| cfDNA mNGS | Mean: 95% [20] | 46.67% Concordance [20] | -- |

| 16S rRNA NGS | -- | 58.54% Concordance [20] | -- |

| ZISC-Filtered gDNA mNGS | >10x increase in microbial reads (9351 RPM vs. 925 RPM in unfiltered) [5] [19] | 100% detection in culture-positive sepsis samples (8/8) [5] [19] | Effectively enriches microbial content from blood. |

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Product / Technology | Function | Application in Host/Pathogen NGS |

|---|---|---|

| ZISC-based Filtration Device (e.g., Devin filter) | Pre-extraction physical removal of host white blood cells via a specialized coating. | Enriches microbial content in blood samples by depleting >99% of host cells, significantly reducing host DNA background [5] [19]. |

| VAHTS Free-Circulating DNA Maxi Kit | Extraction of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from plasma or other liquid supernatants. | Used for preparing libraries for cfDNA-based mNGS, which can help detect pathogens but may have lower sensitivity compared to wcDNA approaches [20]. |

| Qiagen DNA Mini Kit | Extraction of high-quality whole-cell DNA from cell pellets or tissues. | Used for preparing libraries for wcDNA-based mNGS, which has been shown to have higher sensitivity for pathogen detection in body fluids [20]. |

| NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit | Post-extraction depletion of CpG-methylated host DNA. | An alternative method to reduce host DNA background by leveraging differences in methylation patterns between host and microbial DNA [19]. |

| Ultra-Low Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries from samples with low microbial biomass. | Essential for generating high-quality NGS libraries from samples where pathogen nucleic acid is scarce relative to host material [19]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Reference Material | Defined microbial community standards spiked with known quantities of bacteria and fungi. | Serves as an internal spike-in control to monitor the efficacy of the host depletion workflow and the sensitivity of pathogen detection throughout the process [19]. |

Host Depletion Methodologies: From Laboratory Techniques to Bioinformatics

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

General Principles

Q: Why are physical separation methods like filtration and centrifugation critical in chemogenomic NGS? In samples derived from a host (e.g., human tissues or blood), the vast majority of extracted nucleic acids are of host origin. This host DNA background can overwhelm sequencing capacity, drastically reducing the number of microbial reads and compromising the detection sensitivity for pathogens or other non-host organisms. Physical separation methods target the enrichment of microbial cells or DNA prior to sequencing [23].

Q: What is the fundamental difference between pre-extraction and post-extraction host DNA depletion? Pre-extraction methods physically separate microbial cells from host cells or degrade host DNA before the DNA extraction step. Examples include saponin lysis of human cells or nuclease digestion of free-floating host DNA. In contrast, post-extraction methods, such as enzymatic methylation-based depletion, selectively remove host DNA after total DNA (host and microbe) has been extracted [23].

Centrifugation

Q: My centrifuge is vibrating excessively during a run. What should I do? An unbalanced load is the most common cause of centrifuge vibration. Immediately turn off the centrifuge and ensure all sample tubes are of similar weight and are positioned opposite each other in the rotor. Also, inspect the rotor and centrifuge for any visible damage [24].

Q: Can I shorten centrifugation times to improve my workflow's turn-around-time? Yes, but this must be validated for your specific protocol. Some studies on clinical chemistry samples have found that reducing centrifugation time from 15 minutes to 7-10 minutes did not significantly alter test results, but this is highly dependent on the sample type and the relative centrifugation force (RCF) applied. Always refer to your specific protocol's requirements and validate any changes [25].

Q: The lid on my centrifuge won't lock. What could be wrong? Check for any physical obstructions preventing closure. Ensure the safety interlocks are functioning and inspect the lid gasket for tears or damage. If the gasket is damaged, do not use the centrifuge. Cleaning and lubricating the locking mechanism as per the manufacturer's manual may also help [24].

Filtration

Q: How does filtration work as a host depletion method? The F_ase method, for example, uses a 10 μm filter. This pore size allows smaller microbial cells to pass through or be captured while retaining larger mammalian host cells. The filtrate, enriched in microbial cells, is then subjected to nuclease digestion to degrade any remaining cell-free host DNA before microbial DNA extraction [23].

Q: What are the trade-offs of using filtration for host DNA depletion? While effective at increasing microbial read counts, filtration may underrepresent microbial species that are larger than the filter's pore size or those that tend to form clumps. It can also be less effective on samples with a high viscosity that may clog the filter [23].

Common Issues and Solutions

Q: I am consistently getting low yields after host DNA depletion and library preparation. What are the potential causes? Low yield can stem from multiple points in the workflow. The table below outlines common causes and corrective actions [21].

| Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality | Sample contaminants inhibit enzymatic reactions. | Re-purify input sample; check absorbance ratios (260/280 ~1.8). |

| Overly Aggressive Cleanup | Desired DNA fragments are accidentally removed during bead-based cleanup. | Optimize bead-to-sample ratio; avoid over-drying beads. |

| Inefficient Ligation | Adapters do not ligate properly to insert DNA. | Titrate adapter-to-insert molar ratio; ensure fresh ligase. |

| Suboptimal Centrifugation | Incomplete pelleting or unwanted loss of material. | Balance loads properly; follow recommended RCF and time. |

Q: After centrifugation, my sample appears turbid. What does this indicate? In tissue lysates, turbidity often indicates the presence of indigestible protein fibers. These fibers can clog silica membranes during subsequent DNA purification, leading to low yield and protein contamination. The solution is to centrifuge the lysate at maximum speed for 3 minutes to pellet these fibers before proceeding with the binding steps [26].

Experimental Protocols for Host DNA Depletion

Protocol 1: Saponin Lysis and Nuclease Digestion (S_ase)

This pre-extraction method uses saponin to lyse host cells, followed by nuclease to degrade the released host DNA [23].

- Sample Preparation: Resuspend the sample in a buffer containing 0.025% saponin.

- Host Cell Lysis: Incubate the mixture to allow saponin to selectively lyse mammalian cells.

- Nuclease Digestion: Add a nuclease enzyme (e.g., Benzonase) to digest the liberated host DNA. Incubate for the recommended time.

- Nuclease Inactivation: Add EDTA to chelate cations and inactivate the nuclease.

- Microbial Pellet Recovery: Centrifuge the sample to pellet the intact microbial cells.

- Wash and Resuspend: Wash the pellet to remove lysis and digestion remnants, then resuspend in a suitable buffer for standard DNA extraction.

Protocol 2: Filtration and Nuclease Digestion (F_ase)

This pre-extraction method physically separates microbial cells from host cells using a filter [23].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the sample if necessary to reduce viscosity.

- Filtration: Pass the sample through a 10 μm filter unit. Microbial cells pass through the filter or are captured on it, while larger host cells are retained.

- Filter Wash: Wash the filter with a buffer to recover any microbial cells.

- Nuclease Digestion: The flow-through and wash are combined, and a nuclease is added to digest any residual cell-free host DNA.

- Microbial DNA Extraction: Proceed with standard microbial DNA extraction from the nuclease-treated filtrate.

Performance Comparison of Host DNA Depletion Methods

The following table summarizes the performance of various host depletion methods as reported in a benchmark study on respiratory samples [23].

| Method | Type | Key Principle | Host DNA Load Post-Treatment (BALF) | Microbial Read Increase (BALF, fold) | Key Advantages/Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S_ase | Pre-extraction | Saponin lysis + Nuclease | 493.82 pg/mL (0.011‰ of original) | 55.8x | High host removal. Potential taxonomic bias. |

| K_zym | Pre-extraction | Commercial Kit (HostZERO) | 396.60 pg/mL (0.009‰ of original) | 100.3x | Most effective at increasing microbial reads. |

| F_ase | Pre-extraction | 10μm Filtration + Nuclease | Data not specified | 65.6x | Balanced performance. May lose large microbes. |

| R_ase | Pre-extraction | Nuclease Digestion | Data not specified | 16.2x | High bacterial DNA retention. Lower host removal. |

| O_pma | Pre-extraction | Osmotic Lysis + PMA | Data not specified | 2.5x | Least effective in increasing microbial reads. |

Centrifugation Condition Effects

A study on clinical samples showed that centrifugation time could be optimized without affecting analytical results [25].

| Centrifugation Condition | Relative Centrifugal Force (RCF) | Centrifugation Time | Impact on Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition 1 | 2180 g | 15 min | Reference standard (WHO guideline) |

| Condition 2 | 2180 g | 10 min | No significant difference from 15 min |

| Condition 3 | 1870 g | 7 min | No significant difference from 15 min |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Pre-extraction Host DNA Depletion Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Host DNA Depletion |

|---|---|

| Saponin | A detergent that selectively lyses mammalian cell membranes by complexing with cholesterol, releasing host cellular contents while leaving many microbial cells intact [23]. |

| Nuclease Enzyme (e.g., Benzonase) | An endonuclease that digests all forms of DNA and RNA (linear, circular, single- and double-stranded). Used to degrade host DNA after lysis, leaving microbial DNA protected within intact cells [23]. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | A DNA-intercalating dye that penetrates only membrane-compromised (dead) cells. Upon photoactivation, it cross-links DNA, rendering it unamplifiable. Used in methods like O_pma to selectively remove DNA from lysed host cells [23]. |

| Silica Spin Columns | Used in DNA purification kits to bind DNA after host depletion steps. The silica membrane selectively binds DNA in the presence of high-salt buffers, allowing contaminants to be washed away [26]. |

| Magnetic Beads | Used for high-throughput DNA cleanup and size selection. The bead-to-sample ratio is critical for efficient recovery of the target DNA fragment size and removal of adapter dimers [21]. |

In chemogenomic next-generation sequencing (NGS) research, the presence of high levels of host DNA in samples from tissues, blood, or respiratory fluids presents a significant analytical challenge. Selective host DNA degradation through enzymatic and chemical methods enables researchers to deplete this background interference, thereby enriching microbial or pathogen DNA for more effective sequencing and analysis. This technical support center provides essential guidance for implementing these critical techniques.

Core Concepts and Methodologies

What is selective host DNA degradation and why is it critical for NGS?

Selective host DNA degradation refers to laboratory methods that preferentially remove or deplete DNA from the host organism (e.g., human DNA from a clinical sample) to improve the detection and analysis of non-host DNA, such as from pathogens or microbes [2]. This is a crucial sample preparation step for metagenomic NGS (mNGS) in clinical and research settings.

The necessity for this step arises because many clinical samples, like respiratory fluids, blood, or tissues, contain an overwhelming amount of host DNA. For instance, untreated bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and sputum samples can consist of 99.7% and 99.2% host reads, respectively [2]. Sequencing without host depletion results in a shallow effective sequencing depth for microbial DNA, severely underestimating microbial diversity and potentially missing critical pathogens [2].

How do enzymatic and chemical methods compare?

Different methods operate on distinct principles to achieve host DNA depletion. The table below summarizes the core mechanisms of common approaches:

| Method Type | Example | Core Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Digestion | Restriction Enzyme Digestion [27] | Uses restriction enzymes (e.g., BamHI, XmaI) to cut host DNA at specific sequence sites not present in the target parasite or microbial DNA, reducing host template amplification. |

| Enzymatic Depletion | Benzonase-based method [2] | Utilizes enzymes to degrade host DNA while protecting microbial DNA, often by exploiting differences in cell wall structures. |

| Commercial Kits (Multi-mechanism) | MolYsis, HostZERO, QIAamp [2] | Often employ a combination of enzymatic, chemical, and/or physical lysis steps to selectively lyse human cells and degrade the released DNA. |

| Physical Separation | ZISC Filtration [5] | A novel filtration device that physically depletes host white blood cells (WBCs) while allowing microbes to pass through for subsequent DNA extraction. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Our lab is new to host depletion. What is the most common pitfall?

The most common pitfall is applying a single method universally across all sample types without optimization. The optimal host DNA depletion method is highly dependent on your sample type, the clinical question, and the target pathogens [28]. For example, a method optimized for frozen respiratory samples may not perform well for blood samples. It is crucial to optimize a specific workflow for each sample type and question you aim to address [28].

After host depletion and mNGS, our microbial reads are still very low. What could be wrong?

Low microbial reads post-depletion can stem from several issues in the workflow. Consider the following troubleshooting checklist:

- Inefficient Depletion Method: The chosen method may not be effective for your specific sample matrix. For example, some commercial kits like MolYsis and HostZERO showed variable efficiency across BAL, nasal, and sputum samples [2].

- Sample Input Quality: The initial microbial load may be too low, or the sample storage conditions may have reduced microbial viability. Freezing without cryoprotectants can reduce the viability of certain bacteria like Pseudomonas aeruginosa [2].

- Inhibition in Downstream Steps: Components from the host depletion kit may carry over into the DNA extraction or library preparation steps, inhibiting enzymatic reactions [29].

- Over-fragmentation of DNA: During library prep, over-digestion during enzymatic fragmentation can make DNA molecules too short for sequencing. Always follow protocol recommendations for incubation times [30].

We see a shift in the microbial community composition after host depletion. Is this a bias?

A shift in composition can occur and may represent both a true enrichment and a potential methodological bias. Host depletion increases the effective sequencing depth, revealing microbial species that were previously masked by host reads [2]. However, some methods can also introduce bias. For instance, one study noted that most methods did not change the community structure of BAL and nasal samples, but the proportion of Gram-negative bacteria decreased in sputum samples from people with cystic fibrosis after treatment [2]. Furthermore, enzymatic methods can sometimes exhibit sequence bias during fragmentation [30]. Always include appropriate controls to help distinguish true signal from bias.

How critical are controls in a host depletion workflow?

Controls are critical at every stage to ensure results are reliable and interpretable, especially given the high variability of clinical samples [28]. The table below outlines essential controls:

| Stage | Control Type | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Negative Control (e.g., sterile swab, water) | Detect contamination introduced during sample taking or from the collection medium [28]. |

| DNA Extraction | Positive Control (External Quality Assurance sample) | Verify the method yields expected results and is reproducible across runs [28]. |

| Library Preparation | Negative Control (Reagent-only control) | Identify background contamination present in extraction or library prep kits (the "kitome") [28]. |

| Sequencing | Positive Control (Known mock community) | Confirm the entire wet-lab and bioinformatics pipeline is functioning correctly [28]. |

| Bioinformatics | In-silico Negative Control | Establish a baseline for background "noise" in the final data output [28]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Quantitative Comparison of Host Depletion Methods

The following table summarizes a head-to-head comparison of five host DNA depletion methods performed on frozen human respiratory samples, as reported in a 2024 study [2]. This data can guide your method selection.

| Method | Reduction in Host DNA (by Sample Type) | Increase in Final Microbial Reads (vs. Untreated) | Impact on Species Richness |

|---|---|---|---|

| lyPMA | Not the most effective for tested frozen samples [2]. | Not significant for BAL; increased for other types [2]. | Increased for some sample types [2]. |

| Benzonase | Less effective for nasal swabs [2]. | Increased for sputum [2]. | Increased for some sample types [2]. |

| MolYsis | ~69.6% decrease in sputum [2]. | ~100-fold increase in sputum; 10-fold in BAL [2]. | Significantly increased for BAL and nasal [2]. |

| HostZERO | ~73.6% decrease in nasal; ~45.5% in sputum [2]. | ~50-fold increase in sputum; 8-fold in nasal [2]. | Significantly increased for nasal [2]. |

| QIAamp | ~75.4% decrease in nasal [2]. | ~25-fold increase in sputum; 13-fold in nasal [2]. | Significantly increased for nasal [2]. |

Detailed Protocol: Restriction Enzyme-Based Host DNA Depletion

This protocol is adapted from a method validated for detecting blood-borne parasites via 18S rRNA gene sequencing [27].

- Principle: Restriction enzymes (BamHI and XmaI) are used to digest the host 18S rRNA gene template at cut sites present in the host sequence but absent in the target parasite sequences. This reduces host template competition during subsequent PCR amplification [27].

- Workflow:

- DNA Extraction: Extract total DNA from the sample (e.g., blood) using a standard kit (e.g., Qiagen Blood Mini Kit).

- Restriction Digestion:

- Prepare a digestion reaction with the extracted DNA and the restriction enzymes (e.g., BamHI and XmaI).

- Incubate according to the enzymes' optimal conditions (temperature and time).

- DNA Clean-up: Post-digestion, clean the DNA using a PCR clean-up kit (e.g., Monarch PCR & DNA Cleanup Kit). The protocol in [27] recommends splitting the cleaned DNA to select for both >2 kb and <2 kb products to account for varying parasite DNA fragment sizes.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target gene region (e.g., ~200 bp of the 18S rRNA gene) using universal primers.

- Library Prep and Sequencing: Proceed with standard NGS library preparation and sequencing.

- Key Validation Point: This method led to a substantial reduction in human reads and a corresponding 5- to 10-fold increase in parasite reads relative to undigested samples, allowing for discrimination of mixed parasitic infections [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function in Host DNA Depletion | Applicable Sample Types |

|---|---|---|

| MolYsis Kits (e.g., Basic5, Complete5) [28] | Selective lysis of human cells and degradation of released DNA; some kits integrate microbial DNA extraction. | Liquid samples (e.g., blood, BAL) [28]. |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit [2] | Commercial kit for depleting host DNA to improve microbial sequencing. | Respiratory samples (e.g., nasal, sputum, BAL) [2]. |

| QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit [2] | Commercial kit that depletes host DNA while enriching microbial DNA. | Respiratory samples; shown to minimally impact Gram-negative bacteria viability [2]. |

| Benzonase-based Method [2] | An enzymatic approach tailored for degrading host DNA in specific matrices like sputum. | Sputum, skin swabs, saliva [2]. |

| Restriction Enzymes (BamHI, XmaI) [27] | Digests host DNA at specific sequence sites to reduce template competition in PCR-based NGS. | Blood samples for parasite detection [27]. |

| Devin Filter (ZISC) [5] | A novel filtration device that physically removes host white blood cells (>99%) while preserving microbes. | Blood samples for sepsis diagnostics [5]. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: Host DNA Depletion Method Selection Workflow

Zwitterionic Interface Ultra-Self-assemble Coating (ZISC) technology represents a significant advancement in biomedical filtration and coating methods. Inspired by the surface arrangement of the cell-lipid bilayer, zwitterionic materials create a protective layer on material surfaces that prevents contact with biological substances while maintaining strong hydrophilicity and high biocompatibility [31]. The technology is characterized by its high hydrophilicity, low surface free energy, strong hydration, and weak biomolecule interactions, resulting in adhesion resistance to common biological substances [31].

For researchers in chemogenomic next-generation sequencing (NGS), the primary application of ZISC technology lies in its ability to efficiently deplete host cells from biological samples, thereby significantly reducing human DNA background and improving microbial signal detection in metagenomic NGS (mNGS) [1]. This addresses a critical challenge in clinical diagnostics where the overwhelming abundance of human DNA consumes valuable sequencing capacity and masks pathogenic signals.

Technical FAQs and Troubleshooting

Q: What filtration efficiency can I expect from ZISC-based filters for white blood cell removal? A: ZISC-based filters consistently achieve >99% white blood cell (WBC) removal across various blood volumes while allowing unimpeded passage of bacteria and viruses [1]. This high efficiency is maintained across different blood volumes (3-13 mL in validation studies) and is crucial for effective host DNA depletion in mNGS workflows.

Q: How does ZISC-based filtration compare to other host depletion methods? A: Research demonstrates ZISC-based filtration outperforms alternative host depletion techniques in both efficiency and practicality:

Table: Comparison of Host Depletion Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Efficiency | Practical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZISC-based Filtration | Physical filtration with zwitterionic-cell binding | >99% WBC removal [1] | Less labor-intensive, preserves microbial integrity [1] |

| Differential Lysis (QIAamp Kit) | Chemical lysis of human cells | Variable efficiency | Complex workflow, may damage some microbes [1] |

| CpG-Methylated DNA Removal (NEBNext Kit) | Enzymatic removal of methylated host DNA | Post-extraction only | Doesn't prevent host DNA from consuming extraction resources [1] |

Q: Why is my post-filtration microbial recovery inconsistent? A: Inconsistent recovery typically stems from two main issues:

- Filter clogging: Ensure you're using the patented ZISC coating which prevents clogging regardless of filter pore size [1]

- Sample processing speed: Maintain gentle plunger depression when using syringe-based filtration; aggressive pressure can damage microbial cells [1]

Q: What performance improvement should I expect in my mNGS workflow? A: Clinical validations demonstrate substantial improvements:

- gDNA-based mNGS with ZISC filtration detected all expected pathogens in 100% (8/8) of clinical samples [1]

- Average microbial read count of 9,351 reads per million (RPM), over tenfold higher than unfiltered samples (925 RPM) [1]

- Microbial composition remains unaltered, ensuring accurate pathogen profiling [1]

Q: Can ZISC technology be applied to different sample types beyond blood? A: While most extensively validated for blood samples, the fundamental principles of zwitterionic interaction with biological components suggest potential application to various sample types. However, optimal performance requires validation with your specific sample matrix as binding efficiencies may vary.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard ZISC Filtration Protocol for Blood Samples

Materials Required:

- ZISC-based fractionation filter (commercially available as Devin filter from Micronbrane)

- Syringe (appropriate for sample volume)

- Collection tube (15 mL Falcon tube recommended)

- Low-speed centrifuge

- High-speed centrifuge (capable of 16,000g)

- ZISC-based Microbial DNA Enrichment Kit or equivalent

Procedure:

- Transfer approximately 4 mL of whole blood to a syringe

- Securely connect the ZISC-based filter to the syringe

- Gently depress the syringe plunger, pushing blood sample through filter into collection tube

- Subject filtered blood to low-speed centrifugation (400g for 15 min at room temperature) to isolate plasma

- Transfer plasma to new tube for high-speed centrifugation (16,000g) to obtain microbial pellet

- Extract DNA using appropriate kit (ZISC-based Microbial DNA Enrichment Kit recommended)

- Proceed with standard mNGS library preparation

Validation Protocol for Filter Performance

Purpose: Verify filter efficiency and microbial recovery Materials:

- Complete blood cell count analyzer

- Standard plate-enumeration materials

- qPCR setup for viral quantification

- Spiked controls (E. coli, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae recommended)

Procedure:

- Pre-filtration: Measure WBC count using blood analyzer

- Process blood sample through ZISC filter

- Post-filtration: Measure WBC count in filtrate

- Calculate depletion efficiency: [(Pre-count - Post-count)/Pre-count] × 100%

- For microbial passage: Spike blood with 10⁴ CFU/mL of control organisms

- Filter and quantify bacterial counts in filtrate using plate enumeration

- For viral passage: Spike with feline coronavirus and quantify using qPCR

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for ZISC-Based Host Depletion Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ZISC-based Fractionation Filter | Host cell depletion | >99% WBC removal; preserves microbial integrity [1] |

| ZISC-based Microbial DNA Enrichment Kit | DNA extraction from filtered samples | Optimized for post-filtration processing [1] |

| ZymoBIOMICS Reference Materials (D6320, D6331) | Process controls and spike-in controls | Validate microbial recovery; D6331 contains 21 bacterial/fungal species [1] |

| Ultra-Low Library Prep Kit | mNGS library preparation | Compatible with low-biomass samples post-filtration [1] |

Performance Data and Metrics

Table: Quantitative Performance of ZISC-based Filtration in mNGS

| Parameter | Unfiltered Samples | ZISC-Filtered Samples | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial RPM | 925 RPM [1] | 9,351 RPM [1] | >10-fold |

| Pathogen Detection Rate | Variable, culture-dependent | 100% (8/8 clinical samples) [1] | Significant enhancement |

| WBC Depletion | Baseline | >99% [1] | Essential for host DNA reduction |

| Genome Coverage | Limited by host background | Up to 98.9% achievable [7] | Dependent on initial pathogen load |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Recent studies have expanded ZISC technology applications beyond sepsis diagnosis. In pulmonary tuberculosis diagnosis, host DNA depletion-assisted mNGS (HDA-mNGS) demonstrated significantly improved detection sensitivity (72.0% vs 51.2% with conventional mNGS) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples [16]. The technology also provided increased coverage of the MTB genome by up to 16-fold and enhanced detection of antimicrobial resistance loci [16].

For SARS-CoV-2 detection, host DNA-removed mNGS achieved 92.9% detection rate in samples with Ct value ≤35 while simultaneously enabling analysis of host local immune signaling [7]. This dual capability of comprehensive pathogen identification and host response analysis represents a significant advantage for research applications.

The fundamental mechanism involves zwitterionic polymers creating a highly hydrated interface through electrostatic and hydrogen bonding with water molecules, forming a protective layer that resists protein adsorption and cell adhesion [31]. The specific capture of white blood cells is achieved through careful design of charge bias on the zwitterionic surface, creating selective affinity while allowing other blood components to pass through unimpeded [31].

Bioinformatics filtering is a critical post-sequencing step for reducing host DNA background in chemogenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) research. When physical or enzymatic host depletion methods are applied during sample preparation, a significant proportion of host sequences often remains in the sequencing data, particularly in low-biomass samples or those with extremely high initial host content, such as blood and tissue [32] [33]. Computational methods provide a final, vital defense by identifying and removing these residual host reads, thereby enriching the dataset for microbial or pathogenic signals and significantly improving the sensitivity of downstream analyses [33]. This guide details the methodologies, tools, and best practices for implementing effective bioinformatics host sequence removal.

Key Bioinformatics Tools and Workflows

The core task of bioinformatics host filtering involves aligning sequencing reads to a reference host genome and discarding those that map to it. The following table summarizes the primary tools and their key characteristics.

Table 1: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Host Sequence Removal

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Applicable Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| KneadData [33] | Integrated filtering pipeline | Combines quality trimming (Trimmomatic) and host read removal (Bowtie2). Includes pre-built databases for human and mouse genomes. | Short-read (Illumina) |

| Bowtie2 [33] | Read alignment | A fast and memory-efficient tool for aligning sequencing reads to large reference genomes, such as the human genome. | Short-read (Illumina) |

| BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner) [33] | Read alignment | A highly accurate alignment tool, particularly suitable for high-throughput sequencing data for host read subtraction. | Short-read (Illumina) |

| BMTagger [33] | Human sequence removal | A tool developed by NCBI specifically for detecting and tagging sequences originating from human contamination in microbiome data. | FASTA, FASTQ, SRA |

| CLEAN [34] | All-in-one decontamination | Removes host sequences, spike-in controls (e.g., PhiX), and rRNA. Works with both short- and long-read technologies (Illumina, Nanopore). | Short-read, Long-read, FASTA |

The general workflow for host sequence removal follows a logical pipeline from raw sequencing data to cleaned data ready for microbial analysis.

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarks

Protocol: Standard Host Read Removal Using KneadData and Bowtie2

This protocol is commonly used for processing short-read metagenomic data [33].

- Input: Raw sequencing reads in FASTQ format (single-end or paired-end).

- Quality Trimming: Use Trimmomatic (integrated within KneadData) to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases from the reads. Example parameters include a minimum read length of 50 bp and a minimum quality score of 20.

- Host Alignment: Use Bowtie2 to align the trimmed reads against a host reference genome (e.g., human GRCh38). The alignment process is optimized for speed and sensitivity.

- Read Separation: The output of the alignment is processed to separate reads that map to the host genome (to be discarded) from those that do not map (non-host reads).

- Output: The final output is a set of cleaned FASTQ files containing the non-host reads, which are enriched for microbial sequences and suitable for taxonomic profiling or functional analysis.

Quantitative Data on Host Depletion Impact

Empirical studies demonstrate the profound impact of combined wet-lab and computational host depletion. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent research.

Table 2: Impact of Host DNA Removal on Metagenomic Analysis

| Study & Sample Type | Method | Key Metric | Result with Host DNA Removal | Control (No Removal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis Blood Samples [5] | Novel Filtration (gDNA mNGS) + Bioinformatics | Microbial Read Count (RPM) | ~9,351 RPM | ~925 RPM |

| Human/Mouse Colon Biopsies [33] | Host DNA Removal + Bioinformatics | Bacterial Species Detected per Sample | Significantly Increased | Baseline (Lower) |

| Human/Mouse Colon Biopsies [33] | Host DNA Removal + Bioinformatics | Bacterial Gene Detection Rate | Increased by 33.89% (Human) & 95.75% (Mouse) | Baseline |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem: Incomplete Host Read Removal After Filtering

- Potential Cause: The host reference genome used is incomplete or does not match the host sample (e.g., using a standard human reference for a sample with known significant genetic variations) [33].

- Solution: Ensure you are using the most comprehensive and appropriate reference genome available. For human samples, use the latest build from the Genome Reference Consortium.

Problem: Low Microbial Read Recovery After Host Filtering

- Potential Cause: Overly stringent alignment parameters during the host filtering step can cause microbial reads with slight homology to the host genome to be incorrectly discarded [32] [34].

- Solution: Use standardized parameters from established pipelines like KneadData. For advanced users, consider tuning alignment stringency (e.g.,

--very-sensitivein Bowtie2) and validating results with a mock microbial community.

Problem: Persistent Contamination from Reagents or Spike-ins

- Potential Cause: Standard host filtering tools are designed to remove host sequences but may not target common laboratory contaminants or intentionally added control sequences (e.g., PhiX, DCS amplicon) [34] [35].

- Solution: Use a comprehensive decontamination pipeline like CLEAN, which allows for the simultaneous removal of host sequences and common spike-in contaminants using a combined reference file [34].

Problem: Challenges with Long-Read Sequencing Data

- Potential Cause: Traditional alignment tools like Bowtie2 and BWA are optimized for short reads and may not handle long-read data (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) effectively.

- Solution: Employ tools specifically designed for long-read data. The CLEAN pipeline, for instance, uses

minimap2for alignment, which is suitable for both long and short reads [34].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can bioinformatics filtering completely replace experimental host DNA depletion methods? No, it is most effective as a complementary step. Experimental methods (e.g., filtration, enzymatic digestion) reduce the host DNA burden upfront, making sequencing more cost-effective by preventing the allocation of a large majority of reads to host DNA. Bioinformatics filtering then serves as a final, precise cleaning step to remove any residual host sequences [33]. Relying solely on bioinformatics filtering after sequencing a sample with >99% host DNA is computationally wasteful and may fail to detect very low-abundance microbes.

Q2: What are the primary limitations of bioinformatics host filtering? The two main limitations are:

- Dependence on Reference Genomes: The method can only remove sequences that are present in the provided host reference genome. It cannot remove host sequences that are novel or highly divergent from the reference [33].

- Inability to Remove Homologous Sequences: Reads from microbial genes that share homology with host genes may be incorrectly identified as host and removed, potentially leading to the loss of biologically relevant signals [33].

Q3: How can I identify and manage contamination from laboratory reagents or cross-sample contamination in my data? Contamination is a significant challenge in low-biomass studies [36]. Key strategies include:

- Using Negative Controls: Process negative controls (e.g., blank water extracts) alongside your samples through the entire workflow, from extraction to sequencing [36] [35].

- Bioinformatic Identification: Tools like

Decontam(for R) use prevalence or frequency-based statistical methods to identify contaminants by comparing their abundance in true samples versus negative controls [34] [35]. - Standardized Reporting: Adhere to emerging guidelines for reporting contamination and removal workflows in microbiome studies to ensure reproducibility [36].

Q4: We are working with RNA-Seq data from host cells. Is this workflow relevant? Yes, the principle is similar. For host RNA-Seq data, a common goal is to remove ribosomal RNA (rRNA) reads to improve the resolution of mRNA sequencing. Pipelines like CLEAN can be configured to map reads to an rRNA reference database and remove those that align, leaving behind enriched mRNA sequences for downstream expression analysis [34].

Table 3: Key Resources for Bioinformatics Host Depletion

| Item | Function in Host Depletion | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Host Reference Genome | The sequence against which reads are aligned to identify and remove host-derived data. | Human: GRCh38 (hg38); Mouse: GRCm39 (mm39). |

| KneadData Pipeline | An integrated, user-friendly pipeline that performs both quality control and host read removal. | Includes built-in host databases; good for users seeking a standardized workflow [33]. |

| CLEAN Pipeline | A comprehensive, reproducible pipeline for removing host sequences, spike-ins, and rRNA from various data types. | Ideal for complex decontamination needs and long-read data [34]. |

| Negative Control Data | Sequencing data from blank extractions used to identify contaminating sequences present in reagents. | Essential for reliable interpretation of low-biomass microbiome data [36] [35]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the computational power needed for aligning millions of reads against large reference genomes. | Necessary for processing large datasets in a timely manner. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

How can I overcome excessive human DNA background in blood samples for mNGS?

Excessive host DNA in blood samples is a major obstacle, but several host depletion methods can significantly improve microbial detection.

- Pre-extraction Filtration: Novel filtration technologies, such as the Zwitterionic Interface Ultra-Self-assemble Coating (ZISC)-based filter, can physically remove host white blood cells before DNA extraction. One study demonstrated that this method achieved >99% removal of white blood cells while allowing bacteria and viruses to pass through unimpeded. When applied to clinical sepsis samples, this resulted in a tenfold increase in microbial read counts compared to unfiltered samples [19] [5].

- Post-extraction Methylation-Based Enrichment: Commercial kits like the NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit and the MethylMiner Methylated DNA Enrichment Kit exploit the differential methylation patterns between host and microbial DNA. These kits bind and remove methylated host DNA, enriching for non-methylated microbial DNA. A comparative study showed that the NEBNext kit led to a significant decrease in human genome reads and a concurrent significant increase in reads from spiked-in bacteria like K. pneumoniae and S. aureus [37].

- Choosing the Right DNA Source: For blood samples, using genomic DNA (gDNA) from a cell pellet, rather than cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from plasma, is crucial for enabling effective pre-extraction host depletion. Research has shown that host depletion methods significantly enhance gDNA-based mNGS but provide minimal benefit for cfDNA-based approaches [19].

Troubleshooting Tip: If your blood mNGS results show low microbial read counts despite high sequencing depth, consider integrating a pre-extraction host depletion step. The ZISC-based filtration method is noted for being less labor-intensive than some alternative methods [19].

What are the best practices for respiratory sample collection and analysis to ensure reliable mNGS results?

The quality of respiratory samples directly impacts the reliability of mNGS results, making proper collection and quality control paramount.

- Sample Quality Assessment: For sputum samples, use the Bartlett grading system to assess quality. Only samples with a score of ≤1 (indicating ≤10 squamous epithelial cells and ≥25 leukocytes per low-power field) should be used for mNGS. This minimizes contamination from oropharyngeal flora and ensures the sample originates from the lower respiratory tract [38].

- Appropriate Sample Type: While sputum is commonly used, Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) is often the preferred specimen type because it is collected directly from the site of infection, reducing the potential for upper respiratory tract contamination. Studies have successfully used BALF mNGS to identify a wide range of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi, with a high positive clinical impact [39] [40].

- Clinical Interpretation is Key: A positive mNGS result does not always indicate an active infection; it may represent colonization. Therefore, clinicians must correlate sequencing results with the patient's clinical symptoms, imaging findings, and other laboratory tests. A study on pulmonary infections found that a clinician committee was critical for interpreting mNGS results and guiding appropriate patient management [40].

Troubleshooting Tip: If your mNGS results from a respiratory sample show a high diversity of oral commensal bacteria, re-evaluate the sample's quality score. The sample may have been contaminated during collection, and the results should be interpreted with caution [38].

What are common library preparation failures and how can they be diagnosed and fixed?

Library preparation is a critical step where errors can lead to sequencing failure. Common issues fall into several categories [21]:

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Common Root Causes & Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Input & Quality | Low yield; smear on electropherogram; low complexity [21]. | Causes: Degraded DNA/RNA; contaminants (phenol, salts); inaccurate quantification [21].Fixes: Re-purify input; use fluorometric (Qubit) over UV quantification; check 260/230 and 260/280 ratios [21]. |

| Fragmentation & Ligation | Unexpected fragment size; high adapter-dimer peak [21]. | Causes: Over-/under-shearing; improper adapter-to-insert ratio [21].Fixes: Optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter concentration [21]. |

| Amplification (PCR) | High duplicate rate; amplification bias [21]. | Causes: Too many PCR cycles; enzyme inhibitors [21].Fixes: Reduce cycle number; use clean, high-quality input DNA [21]. |

| Purification & Cleanup | High adapter-dimer signal; sample loss [21]. | Causes: Wrong bead-to-sample ratio; over-drying beads; pipetting error [21].Fixes: Precisely follow cleanup protocols; use master mixes to reduce pipetting errors [21]. |

Diagnostic Flow: To systematically diagnose a problem, (1) check the electropherogram for abnormal peaks (e.g., a sharp ~120 bp peak indicates adapter dimers), (2) cross-validate DNA quantification with both fluorometric and qPCR methods, and (3) trace the problem backward through each preparation step [21].

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

Protocol 1: ZISC-Based Host Depletion for Blood Samples

This protocol is adapted from a study optimizing mNGS for sepsis diagnosis [19].

Principle: A specialized filter coating selectively binds and retains host leukocytes based on their surface properties, allowing microbial cells to pass through for downstream processing.

Workflow Diagram:

Key Steps: