Strategic Cell Health Assessment: A Guide to Effective Compound Toxicity Filtering in Drug Discovery

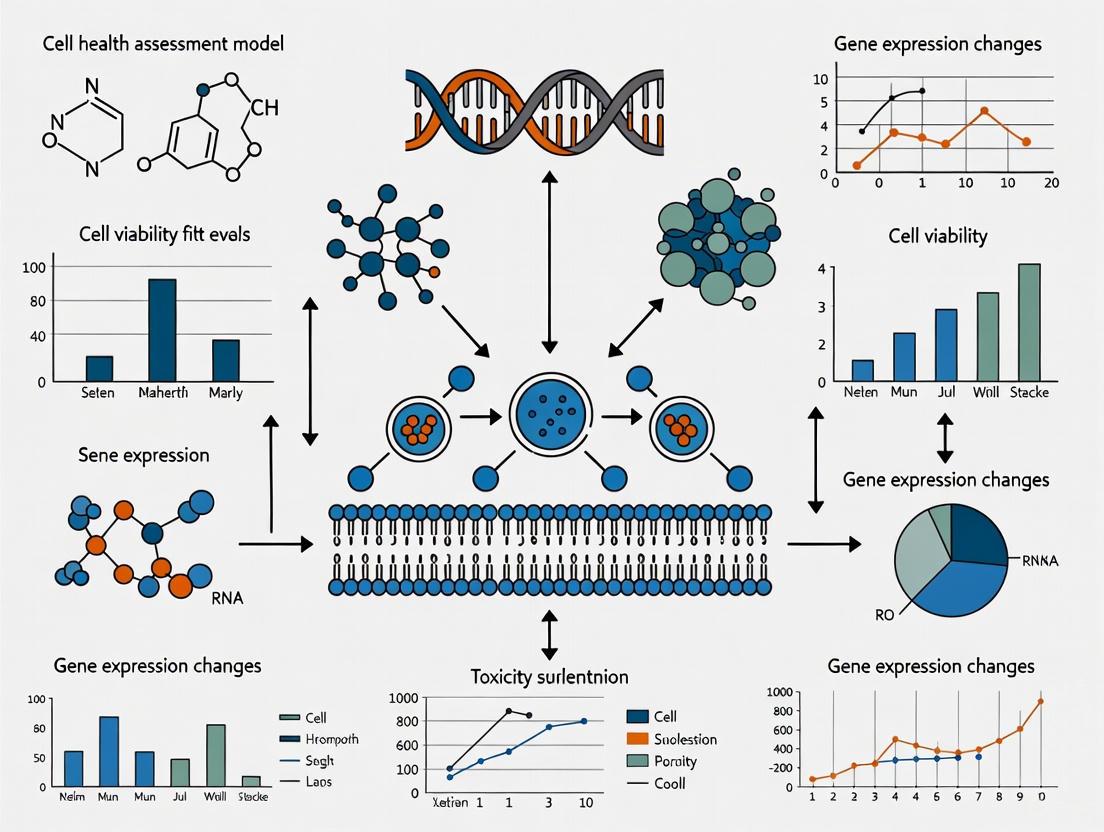

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging cell health assessment for early and predictive compound toxicity filtering.

Strategic Cell Health Assessment: A Guide to Effective Compound Toxicity Filtering in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging cell health assessment for early and predictive compound toxicity filtering. It covers the foundational mechanisms of cell toxicity, including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and DNA damage. The scope extends to a detailed comparison of traditional and advanced methodological approaches, such as high-throughput screening and multiplexed assays, while addressing common troubleshooting challenges like assay misinterpretation and timing. Furthermore, it explores validation strategies and the comparative analysis of emerging technologies, including 3D models, high-content imaging, and AI-driven analytics, to enhance predictive accuracy and streamline the drug development pipeline.

Understanding the Core Mechanisms of Cell Toxicity

Defining Cell Viability and Cytotoxicity in a Toxicological Context

Core Definitions and Their Importance in Toxicology

What is the fundamental difference between cell viability and cytotoxicity?

In the context of assessing compound toxicity, cell viability and cytotoxicity are two complementary yet distinct concepts that form the foundation of cell health assessment.

- Cell Viability refers to the number of healthy, functioning cells in a population and their capacity to maintain normal physiological processes under specific conditions, such as exposure to a test compound. It is a direct indicator of overall cell health and function. [1]

- Cytotoxicity is the property of a substance or compound to cause damage or death to cells. It specifically refers to the ability to disrupt essential cellular processes, leading to cell injury or death. Cytotoxicity assessment is a crucial parameter for evaluating the potential harm of compounds in drug development and environmental safety testing. [1]

In practice, viability assays measure the proportion of living cells, while cytotoxicity assays measure the degree of damage caused by a toxic agent. For a comprehensive safety profile in compound filtering research, it is essential to employ both types of assays, as they provide different pieces of the puzzle regarding a compound's biological impact. [1] [2]

Assay Selection Guide: Mechanisms and Applications

How do I choose the right assay to measure viability or cytotoxicity?

Selecting the appropriate assay is critical for generating reliable and meaningful data in toxicity screening. The choice depends on the mechanism of action you wish to probe and the specific readout required. The table below summarizes the most common assays used in toxicological contexts.

Table 1: Common Cell Viability and Cytotoxicity Assays in Toxicology

| Assay Name | Primary Measurement | Mechanism of Action / Target | Common Application in Toxicity Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| MTT[ [3] [4] | Metabolic Activity (Viability) | Reduction of tetrazolium salt to formazan by mitochondrial dehydrogenases. | Measuring metabolic competence of cells after compound exposure. |

| WST-1[ [5] | Metabolic Activity (Viability) | Reduction of tetrazolium salt to water-soluble formazan by cellular enzymes. | Ideal for high-throughput screening; does not require a solubilization step. |

| ATP Assay (e.g., CellTiter-Glo)[ [3] [6] | Metabolic Activity (Viability) | Quantification of cellular ATP levels using luciferase-luciferin reaction. | Highly sensitive marker for viable cell number; rapid and homogeneous. |

| LDH Release[ [7] | Membrane Integrity (Cytotoxicity) | Measurement of Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) enzyme released from damaged cells. | Quantifying cell membrane damage and necrotic cell death. |

| Neutral Red Uptake (NRU)[ [2] | Lysosomal Function & Membrane Integrity (Viability) | Uptake and retention of the supravital dye Neutral Red by viable cells. | Assessing the capacity of viable cells to incorporate and bind the dye. |

| Caspase-Glo 3/7[ [6] | Apoptosis (Cytotoxicity Mechanism) | Measurement of caspase-3 and -7 activity, key executioners of apoptosis. | Differentiating apoptotic cell death from other mechanisms like necrosis. |

| Live/Dead Staining[ [6] | Membrane Integrity (Viability/Cytotoxicity) | Simultaneous staining with fluorescent markers for live (calcein-AM) and dead (propidium iodide) cells. | Visualizing and quantifying the ratio of live to dead cells in a population. |

| Colony Forming Unit (CFU)[ [2] | Proliferative Capacity (Viability) | Ability of a single cell to grow into a colony, indicating long-term reproductive health. | Measuring the clonogenic potential of cells after treatment with a compound. |

Visual Guide to Assay Selection

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting an assay based on the biological question and the nature of the compound being tested.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

What are the standard protocols for key viability and cytotoxicity assays?

Below are detailed methodologies for two commonly used and complementary assays: the MTT assay for viability and the LDH assay for cytotoxicity.

Principle: Metabolically active cells reduce the yellow tetrazolium salt MTT to purple, insoluble formazan crystals. The amount of formazan produced is proportional to the number of viable cells.

Reagents & Materials:

- MTT reagent: Prepare at 5 mg/mL in Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS) and filter-sterilize.

- Solubilization Solution: 40% Dimethylformamide (DMF), 2% Glacial Acetic Acid, 16% Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), pH adjusted to 4.7.

- 96-well tissue culture-treated plate

- Microplate reader capable of measuring absorbance at 570 nm.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Seed cells at an optimal density in a 96-well plate and culture overnight. Expose cells to your test compounds for the desired duration.

- MTT Incubation: Add the prepared MTT solution directly to each well to achieve a final concentration of 0.2 - 0.5 mg/mL. Typically, 10-20 µL of MTT stock is added to 100 µL of culture medium.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate for 1 to 4 hours at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator. Monitor for the formation of purple formazan crystals under a microscope.

- Solubilization: Carefully remove the culture medium containing MTT. Add the solubilization solution (e.g., 100 µL per well for a 96-well plate). Agitate the plate gently on an orbital shaker to fully dissolve the formazan crystals. This may take 10-30 minutes.

- Absorbance Measurement: Read the absorbance of each well at 570 nm using a microplate reader. A reference wavelength of 630-650 nm can be used to subtract background.

Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of cell viability relative to the untreated control cells after subtracting the background absorbance from wells with medium and MTT only (blank).

Principle: This assay measures the activity of the cytosolic enzyme Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the culture medium upon cell membrane damage. The released LDH is quantified by a coupled enzymatic reaction that results in a colored product.

Reagents & Materials:

- LDH assay kit (typically containing reaction buffer, substrate, and dye).

- Lysis solution (for generating maximum LDH release control).

- 96-well plate (clear flat-bottom).

- Microplate reader capable of measuring absorbance at 490-500 nm.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: At the end of compound treatment, centrifuge the cell culture plate (e.g., 250 × g for 5 minutes) to pellet any detached cells and debris.

- Transfer Supernatant: Carefully transfer a portion of the cell-free supernatant (typically 50 µL) to a new clear 96-well assay plate.

- Reaction Setup: Add the LDH reaction mixture to each well containing the supernatant, following the kit manufacturer's instructions. Incubate for 15-30 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

- Signal Measurement: Add the stop solution (if provided) and measure the absorbance at 490-500 nm.

Data Analysis:

- Spontaneous LDH Activity: LDH released from untreated control cells (background cell death).

- Maximum LDH Activity: LDH released from control cells treated with lysis solution (represents 100% cytotoxicity).

- Compound-induced LDH Activity: LDH released from compound-treated cells.

Calculate the percentage of cytotoxicity using the formula: % Cytotoxicity = (Compound LDH - Spontaneous LDH) / (Maximum LDH - Spontaneous LDH) × 100

Workflow for a Combined Viability and Cytotoxicity Assessment

For a comprehensive analysis, researchers often run viability and cytotoxicity assays in parallel. The following diagram outlines a typical integrated workflow.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Why is my viability assay showing increased signal with a known cytotoxic compound?

This phenomenon, often called "hyper-metabolism," can occur with certain compounds at specific concentrations. Some toxicants, like oxidative phosphorylation uncouplers (e.g., tolcapone, benzarone), can cause a compensatory increase in metabolic rate and a transient rise in the signal of assays like MTT or Realtime-Glo before cell death occurs. [7] Solution: Always use multiple assays that probe different biological endpoints (e.g., combine a metabolic assay like MTT with a membrane integrity assay like LDH). This provides a more complete picture and helps identify such artifacts. [7] [6]

My assay results have high variability between replicates. What could be the cause?

High variability often stems from technical inconsistencies. Solution: Ensure a homogeneous single-cell suspension before seeding by pipetting thoroughly. Optimize and maintain consistent cell seeding density across all wells. Use multichannel pipettes for reagent addition to minimize timing differences. Finally, avoid placing control or treated wells on the edges of the plate if "edge effect" is suspected due to evaporation; instead, fill perimeter wells with PBS or medium only. [4] [5]

The formazan crystals in my MTT assay are not dissolving properly. How can I fix this?

Incomplete solubilization is a common issue. Solution: First, ensure you are using the correct solubilization solution (e.g., DMSO, acidified isopropanol, or SDS-based solutions). [4] After adding the solubilization solution, seal the plate with parafilm and incubate on an orbital shaker for an extended period (up to 1 hour). If crystals persist, gently pipette up and down or briefly sonicate the plate in a water bath sonicator. [4]

My test compound is colored and interferes with the absorbance reading. How can I account for this?

Colorimetric interference is a well-known limitation of assays like MTT and WST-1. Solution: Include control wells containing the compound at the tested concentrations in culture medium without cells. Subtract the absorbance values of these "compound-only" backgrounds from the corresponding test wells during data analysis. [4] [5] Alternatively, consider switching to a non-colorimetric assay, such as a luminescent ATP assay or a fluorometric assay like CFDA-AM or alamar blue. [3]

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful experiment relies on high-quality reagents. The table below lists essential materials and their functions for cell health assessment assays.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Viability and Cytotoxicity Testing

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Tetrazolium Salts (MTT, WST-1, MTS) | Substrates reduced by metabolically active cells to generate a colorimetric signal. | MTT, WST-1, MTS Assays [3] [4] [5] |

| LDH Assay Kit | Provides optimized reagents for the coupled enzymatic reaction to quantify lactate dehydrogenase released from damaged cells. | LDH Release Assay [7] |

| ATP Detection Reagent | Luciferase enzyme that produces luminescence in the presence of ATP, a marker of metabolically active cells. | CellTiter-Glo [3] [6] |

| Caspase Substrate | Proteolytic substrate that generates a luminescent or fluorescent signal when cleaved by active caspase-3/7. | Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay [6] |

| Fluorescent Viability Dyes (Calcein-AM, Propidium Iodide) | Live cells esterify non-fluorescent Calcein-AM to green-fluorescent calcein. Dead cells with compromised membranes are stained by red-fluorescent PI. | Live/Dead Staining [6] |

| Cell Culture Microplates | Specially treated plasticware with clear, flat bottoms for optimal cell attachment and accurate optical readings. | All microplate-based assays |

| Microplate Reader | Instrument capable of detecting absorbance, luminescence, and/or fluorescence signals from multi-well plates. | All assays |

Core Mechanisms and Scientific Background

What are the key mechanisms linking oxidative stress, ROS, and mitochondrial dysfunction in compound toxicity screening?

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a central mechanism in compound toxicity, primarily through excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and impaired cellular energy metabolism. During oxidative phosphorylation, electrons leak from mitochondrial complexes I and III, reducing oxygen to superoxide anion (O₂⁻), which is converted to other ROS like hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [8] [9]. This creates oxidative stress when ROS production overwhelms antioxidant defenses, leading to cellular damage that is critical to assess in toxicity screening [9] [10].

The resulting oxidative damage impairs ATP production, damages mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and disrupts calcium homeostasis [10] [11]. mtDNA is particularly vulnerable due to its proximity to ROS generation sites and lack of histone protection [9]. This mitochondrial impairment activates programmed cell death pathways, making it a key endpoint for assessing compound toxicity [10] [12].

Table 1: Primary Sources and Characteristics of Mitochondrial ROS

| ROS Source | Location | Primary ROS Produced | Significance in Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) | Mitochondrial matrix | O₂⁻ | Major electron leak site during impaired electron transport [8] [9] |

| Complex III (cytochrome c reductase) | Mitochondrial inner membrane | O₂⁻ | Produces ROS in both matrix and intermembrane space [9] |

| Reverse Electron Transport (RET) | Mitochondrial electron transport chain | O₂⁻ | Significant superoxide generation during electron backflow [9] |

| Glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Mitochondrial inner membrane | O₂⁻ or H₂O₂ | Additional mitochondrial ROS generation site [8] |

How does mitochondrial dysfunction propagate cellular damage in response to toxic compounds?

Mitochondrial dysfunction propagates cellular damage through several interconnected mechanisms that amplify initial toxic insults. The process typically begins with impaired electron transport chain function, leading to reduced ATP synthesis and increased electron leakage [9] [10]. These electrons directly reduce molecular oxygen, generating superoxide anions that initiate a cascade of oxidative damage [8].

The oxidative stress damages mtDNA, proteins, and lipids, creating a vicious cycle that further compromises mitochondrial function [10] [11]. Key proteins regulating mitochondrial dynamics become impaired, disrupting the balance between fission and fusion processes [8]. This leads to abnormal mitochondrial morphology and compromised quality control mechanisms, including impaired mitophagy [11].

As dysfunction progresses, the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opens, releasing cytochrome c and other pro-apoptotic factors that activate caspase-dependent apoptosis [10] [12]. Simultaneously, oxidative stress triggers inflammatory responses through damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), including mtDNA released into the cytoplasm, which activates inflammasomes and amplifies cellular injury [8].

Figure 1: Oxidative Stress Amplification Cycle in Compound Toxicity. This diagram illustrates how initial mitochondrial insult creates a self-amplifying cycle of damage through ROS production and oxidative stress.

Troubleshooting Guides: Experimental Issues and Solutions

Why is there no assay window in my mitochondrial toxicity assay, and how can I resolve this?

A completely absent assay window typically indicates fundamental issues with instrument setup or reagent problems. First, verify your microplate reader is properly configured for your specific assay type. For TR-FRET assays, ensure you're using exactly the recommended emission filters, as incorrect filter selection is the most common failure point [13].

Test your instrument setup using control reagents before running your actual experiment. Check that all stock solutions are prepared correctly at specified concentrations (typically 1 mM), as differences in stock solutions between labs frequently cause EC50/IC50 variability [13]. For cell-based assays, confirm your compounds can cross cell membranes and aren't being pumped out, which would prevent intracellular target engagement [13].

Table 2: Antioxidant Defense Systems in Mitochondrial Toxicity Assessment

| Antioxidant System | Components | Function in Toxicity Mitigation | Measurement in Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutathione System | GSH, GSSG, GPx, GR | Reduces H₂O₂ to H₂O while oxidizing GSH to GSSG; regenerated by GR [8] | GSH/GSSG ratio, GPx activity |

| Enzymatic Defenses | SOD, Catalase, Peroxiredoxin | SOD converts O₂⁻ to H₂O₂; catalase/peroxiredoxin decompose H₂O₂ to H₂O and O₂ [8] [10] | SOD activity, catalase activity |

| Small Molecule Antioxidants | Melatonin, CoQ10 | Directly scavenge ROS and indirectly boost antioxidant enzymes [8] [11] | Concentration measurements |

| Mitochondrial Dynamics | Drp1, OPA1, Mfn1/2 | Regulate fission/fusion balance; dysregulated in toxicity [8] [11] | Protein expression, localization |

Why am I getting inconsistent EC50/IC50 values between experiments when screening compounds for mitochondrial toxicity?

Inconsistent potency values typically stem from three main sources: stock solution preparation, cellular context variability, and assay execution differences. The primary reason for EC50/IC50 differences between labs is variation in stock solution preparation, particularly at the critical 1 mM concentration [13]. Use freshly prepared stocks with verified purity and concentration.

Passage number significantly influences experimental outcomes in cell-based assays [14]. Use consistent passage ranges and ensure thorough cell authentication. Mycoplasma contamination can profoundly alter mitochondrial function and cellular responses - implement regular testing using appropriate detection methods [14].

For kinase-targeted compounds, remember that cell-based assays may target inactive kinase forms or upstream/downstream kinases, while biochemical assays require active kinases [13]. This fundamental difference can explain potency discrepancies between assay formats. Always include appropriate reference compounds and controls to normalize results between experimental runs.

Figure 2: Troubleshooting Inconsistent Potency Measurements. This flowchart outlines common sources of variability in mitochondrial toxicity screening and corresponding corrective actions.

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

What is a robust protocol for assessing compound-induced mitochondrial dysfunction through oxidative stress parameters?

Principle: This protocol measures key oxidative stress parameters to evaluate compound-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, focusing on ROS production, antioxidant depletion, and oxidative damage markers [8] [10].

Materials:

- Cell culture system relevant to your toxicity model (primary cells or appropriate cell lines)

- Compounds for screening with appropriate vehicle controls

- ROS detection probes (DCFDA for general ROS, MitoSOX for mitochondrial superoxide)

- GSH/GSSG detection kit

- Lipid peroxidation assay (MDA detection)

- mtDNA damage detection reagents (Long-range PCR or appropriate kits)

- Microplate reader with appropriate filters

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Plate cells at optimized density in appropriate multi-well plates. Use consistent passage numbers and authenticate cell lines regularly [14].

- Compound Treatment: Treat cells with test compounds across a concentration range (typically 0.1-100 μM) for 4-24 hours depending on mechanism. Include vehicle and positive controls.

- ROS Measurement:

- Load cells with 10 μM DCFDA or 5 μM MitoSOX in serum-free media

- Incubate 30-45 minutes at 37°C

- Wash with PBS and measure fluorescence (DCFDA: Ex/Em 485/535nm; MitoSOX: Ex/Em 510/580nm)

- Glutathione Measurement:

- Collect cells and process for GSH/GSSG detection per kit instructions

- Measure absorbance or fluorescence to determine GSH/GSSG ratio

- Lipid Peroxidation Assessment:

- Measure malondialdehyde (MDA) levels using thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay

- Incubate samples with TBA reagent at 95°C for 60 minutes

- Measure absorbance at 532nm

- mtDNA Damage Assessment:

- Extract total DNA including mtDNA

- Perform long-range PCR of mitochondrial genes versus nuclear genes

- Quantify amplification efficiency reduction as indicator of DNA damage

Data Analysis: Calculate fold-change relative to vehicle controls for each parameter. Establish significance thresholds based on positive controls. Compounds showing concentration-dependent increases in ROS and MDA with decreased GSH/GSSG ratio indicate mitochondrial oxidative stress.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Mitochondrial Toxicity Assessment

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Mitochondrial Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| ROS Detection Probes | DCFDA, MitoSOX Red, H₂DCFDA | General and mitochondrial-specific ROS detection [10] [12] |

| Antioxidant Assays | GSH/GSSG-Glo, Total Glutathione kits | Quantify redox balance and antioxidant capacity [8] [15] |

| Oxidative Damage Markers | TBARS assay kits, Protein carbonylation kits | Lipid peroxidation (MDA) and protein oxidation measurement [10] [15] |

| Mitochondrial Function Assays | Seahorse XF kits, JC-1 dye, TMRM | Respiration, membrane potential, and function analysis [16] [11] |

| Cell Viability/Cytotoxicity | CellTiter-Glo, MTT, LDH assays | Viability correlation with mitochondrial parameters [17] |

| mtDNA Damage Detection | Long-range PCR kits, mtDNA-specific primers | Mitochondrial genome integrity assessment [9] [10] |

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I determine whether observed mitochondrial toxicity is primary or secondary to other cellular damage?

Primary mitochondrial toxicity manifests as direct, concentration-dependent impairment of mitochondrial parameters that precedes other signs of cellular distress. Key indicators include early disruption of oxygen consumption rate (OCR), decreased ATP production, and increased mitochondrial ROS specifically occurring before significant plasma membrane permeability or nuclear condensation [10] [11]. The toxic compound typically directly targets electron transport chain components, mitochondrial membranes, or mtDNA [9].

Secondary mitochondrial dysfunction occurs as a consequence of other primary insults, such as calcium overload, glutathione depletion, or activation of death receptors. This typically manifests later in the toxicity timeline and may be prevented by inhibitors of the primary insult [10] [12]. To distinguish between these mechanisms, perform time-course experiments measuring mitochondrial parameters alongside other cell health indicators, and use specific mitochondrial protectants like cyclosporine A (mPTP inhibitor) or antioxidants to determine if they prevent toxicity.

What are the most relevant positive controls for establishing mitochondrial toxicity assay performance?

For general oxidative stress induction, tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBHP) and antimycin A are excellent positive controls. tBHP directly induces peroxidative stress, while antimycin A specifically inhibits complex III, increasing superoxide production [9]. For complex I-specific dysfunction, use rotenone or piericidin A [9] [11]. For mitochondrial permeability transition, use calcium ionophores in combination with inorganic phosphate.

Include both acute (1-4 hour) and longer-term (24-hour) exposures to capture different mechanisms. Validate your positive controls against literature values for potency and maximal effects. For antioxidant response measurements, compounds like sulforaphane that induce Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses can serve as positive controls for protective pathways [8] [15].

The Role of Apoptosis, Necrosis, and Other Cell Death Pathways

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: General Cell Death Concepts

Q1: What is the core difference between accidental and regulated cell death?

A1: The fundamental difference lies in the control and physiological implications of the process.

- Accidental Cell Death (ACD): This is an uncontrolled, passive process triggered by severe physical, chemical, or mechanical insults that exceed the cell's tolerance. It is not genetically encoded and typically leads to inflammation. Necrosis is the classic example of ACD. [18]

- Regulated Cell Death (RCD): This is an active, genetically programmed process that requires specific molecular machinery. RCD plays crucial roles in development, tissue homeostasis, and the removal of damaged cells. Apoptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis are all forms of RCD. The term Programmed Cell Death (PCD) is often used interchangeably with RCD. [18] [19]

Q2: My viability assay shows reduced cell numbers, but I'm unsure if it's due to death or proliferation arrest. How can I tell?

A2: This is a common challenge, as metabolic activity assays like MTT/MTS can be influenced by both cell death and slowed metabolism. [20] To distinguish between these, a multi-parametric approach is essential.

- Confirm Cell Death Directly: Use a LIVE/DEAD assay (e.g., calcein-AM for live cells, EthD-1 or propidium iodide (PI) for dead cells) or an Annexin V/PI assay to directly quantify the proportion of dead and dying cells. [20] [21]

- Assess Proliferation: Incorporate a proliferation-specific dye like CellTrace Violet or BrdU to track cell division. A decrease in viable cell number without an increase in dead cell markers strongly suggests cytostatic effects. [20] [21]

Q3: I've heard about "crosstalk" between cell death pathways. What does this mean for my experiments?

A3: Crosstalk refers to the extensive molecular interactions where one cell death pathway can influence the initiation or execution of another. [19] [22] This has critical experimental implications:

- Inhibition is Not Always Clean: Using a caspase inhibitor (e.g., Q-VD-OPh) to block apoptosis may not prevent cell death if the stimulus is strong enough to activate a backup pathway like necroptosis. [20]

- Combined Targeting May Be Needed: For effective therapeutic outcomes, especially in cancer, it may be necessary to target multiple RCD pathways simultaneously to overcome resistance. [23] [24]

- Always Use Multiple Assays: Relying on a single method to define a cell death type is risky. Confirm your findings with complementary techniques that assess different hallmarks (e.g., morphology, caspase activation, lipid peroxidation). [20]

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying Specific Cell Death Pathways

Q4: How can I confirm that cell death in my model is truly apoptosis?

A4: Apoptosis should be confirmed by assessing multiple hallmarks. The table below summarizes key characteristics and detection methods.

| Feature to Assess | Key Markers & Reagents | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|

| Morphology | Cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, apoptotic bodies | Phase-contrast microscopy, fluorescent DNA dyes (Hoechst) |

| Phosphatidylserine Exposure | Annexin V (requires calcium buffer) | Flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy |

| Membrane Integrity | Propidium Iodide (PI) or EthD-1 | Flow cytometry (used with Annexin V) |

| Caspase Activation | Fluorogenic caspase substrates (e.g., DEVD-FMK for caspase-3), cleaved caspase-3 antibodies | Flow cytometry, Western blot, fluorescence microscopy |

| Mitochondrial Pathway | Cytochrome c release, Bax/Bak activation | Western blot (cytochrome c in cytosol), immunofluorescence |

| Key Protein Cleavage | Cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase substrates | Western blot |

| Pharmacological Inhibition | Pan-caspase inhibitor (e.g., Q-VD-OPh, Z-VAD-FMK) | Pre-treatment to rescue viability |

Experimental Protocol: Annexin V/PI Staining for Flow Cytometry

- Harvest Cells: Collect both adherent and floating cells.

- Wash: Resuspend cell pellet in cold PBS.

- Staining: Resuspend ~100,000 cells in 100 µL of Annexin V Binding Buffer.

- Add Dyes: Add Annexin V-fluorochrome conjugate (e.g., FITC) and PI. Incubate for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature.

- Analyze: Add more binding buffer and analyze immediately by flow cytometry.

Q5: My cells are dying, but it doesn't look like classic apoptosis. What other pathways should I investigate?

A5: Many non-apoptotic RCD pathways can be triggered, especially by chemotherapeutic agents or in resistant cancer cells. The table below outlines alternative pathways and their key markers.

| Pathway | Key Inducers/Inhibitors | Critical Markers & Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Ferroptosis | Inducers: Erastin, RSL3, sulfasalazine.Inhibitors: Ferrostatin-1, liproxstatin-1. | Lipid Peroxidation: C11-BODIPY 581/591 probe, MDA assay.GPX4 Inactivation: Western blot.Iron Chelation: Deferoxamine (inhibits).Morphology: Shrunken mitochondria with intact nuclei. [25] |

| Necroptosis | Inducer: TNF-α + caspase inhibitor (e.g., Z-VAD) + IAP inhibitor (e.g., SMAC mimetic).Inhibitor: Necrostatin-1 (RIPK1 inhibitor). | Phospho-RIPK1/RIPK3, MLKL oligomerization: Western blot.Morphology: Necrotic-like swelling and rupture. [20] [24] |

| Pyroptosis | Inducers: Intracellular pathogens, DAMPs/PAMPs. | Cleaved Gasdermin D (GSDMD): Western blot.Active Caspase-1: Western blot/assay.Inflammasome Formation.Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release: Cytotoxicity assay. [26] |

| Autophagic Cell Death | Inducer: Rapamycin, nutrient starvation.Inhibitor: Chloroquine, bafilomycin A1. | LC3-I to LC3-II conversion: Western blot.Autophagosome formation: GFP-LC3 puncta by microscopy.SQSTM1/p62 degradation: Western blot. [19] [24] |

Q6: I need a comprehensive view of cell health in one sample. Is there an integrated workflow?

A6: Yes, a multiparametric flow cytometry protocol can assess proliferation, cell cycle, apoptosis, and mitochondrial health simultaneously from a single sample. [21]

Experimental Protocol: Integrated Flow Cytometry Workflow

- Proliferation Staining: Prior to treatment, stain cells with CellTrace Violet dye, which dilutes with each cell division.

- Treatment & Incubation: Expose cells to your compound for the desired time.

- BrdU Incorporation: Add BrdU for a pulse (e.g., 1-2 hours) to label S-phase cells.

- Harvest and Stain:

- Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm): Stain with JC-1 dye. Healthy mitochondria show red (J-aggregates) and green (monomer) fluorescence; depolarized mitochondria show only green.

- Apoptosis & Death: Stain with Annexin V and PI.

- Cell Cycle/Fixation: Fix and permeabilize cells, then digest RNA and stain DNA with PI. Detect incorporated BrdU with a fluorescent antibody.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Acquire data on all fluorescent channels. This provides eight key parameters from one sample: CellTrace Violet (proliferation), BrdU (S-phase), PI for DNA content (cell cycle), JC-1 (ΔΨm), Annexin V (apoptosis), and PI permeability (cell death). [21]

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential reagents for studying different cell death pathways, along with their primary functions.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Q-VD-OPh | Broad-spectrum, pan-caspase inhibitor used to confirm apoptosis and prevent caspase-dependent death. [20] |

| Annexin V (FITC/APC) | Binds to phosphatidylserine (PS) exposed on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane during early apoptosis. [20] [21] |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | DNA intercalating dye that is impermeant to live and early apoptotic cells. Used to mark dead cells with compromised membranes. [21] |

| Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) | Specific inhibitor of ferroptosis; acts as a radical trapping antioxidant to prevent lipid peroxidation. [20] [25] |

| Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) | Specific inhibitor of RIPK1 kinase activity, used to inhibit necroptosis. [20] |

| Chloroquine (CQ) | Lysosomotropic agent that inhibits autophagy by raising lysosomal pH and preventing autophagosome degradation. [20] |

| JC-1 Dye | Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) sensor. A decrease in red/green fluorescence ratio indicates mitochondrial depolarization, an early event in intrinsic apoptosis. [21] |

| C11-BODIPY 581/591 | Lipid peroxidation sensor. Oxidation causes a shift in fluorescence from red to green, detectable by flow cytometry or microscopy. [25] |

| CellTrace Violet | Fluorescent cell proliferation dye that dilutes equally with each cell division, allowing tracking of proliferation kinetics. [21] |

| Z-VAD-FMK | Another common pan-caspase inhibitor, used similarly to Q-VD-OPh to block apoptotic signaling. [24] |

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the core molecular mechanisms of key cell death pathways, providing a visual reference for understanding their components and crosstalk.

Apoptosis Signaling Pathways

Ferroptosis Core Mechanism

Integrated Cell Death Crosstalk

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) as a Central Modulator in Toxicity

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) are a group of chemically reactive molecules containing oxygen, produced as natural byproducts of aerobic metabolism. In the context of compound toxicity screening, understanding ROS is paramount because they function as a double-edged sword: at low/moderate concentrations, they act as crucial signaling molecules for normal physiological processes, but at excessive levels, they induce oxidative stress, leading to macromolecular damage and cell death [27] [28].

The dual role of ROS makes them a central modulator in toxicity. Oxidative stress occurs when the production of ROS overwhelms the cell's antioxidant defenses [29]. This imbalance can be induced by toxic compounds and can severely compromise cell health, damaging lipids, proteins, and DNA, which can ultimately lead to carcinogenesis, neurodegeneration, and other disease states [29] [28]. Therefore, accurate assessment of ROS and the resulting oxidative damage is a critical component of cell health assessment in compound toxicity filtering research.

Core Concepts and Terminology

What are the key ROS molecules? ROS is a collective term that includes both oxygen radicals and certain non-radical oxidizing agents [28]. The key species, their sources, and primary reactivities are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Biological Systems

| ROS Species | Chemical Symbol | Primary Sources | Reactivity & Role in Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide | O₂•⁻ | Mitochondrial ETC (Complex I & III), NOX enzymes [27] [30] | Not highly reactive itself, but a progenitor to other ROS; inactivates Fe-S cluster proteins [27] [31] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | H₂O₂ | Dismutation of O₂•⁻ by SOD, various oxidase enzymes [27] [31] | Poorly reactive but long-lived; diffuses easily; key signaling molecule and substrate for more reactive species [31] |

| Hydroxyl Radical | HO• | Fenton reaction (H₂O₂ + Fe²⁺) [30] [28] | Extremely reactive; causes immediate, indiscriminate oxidative damage to all nearby biomolecules [31] |

| Peroxynitrite | ONOO⁻ | Reaction of O₂•⁻ with nitric oxide (NO) [27] [30] | Potent oxidant; causes nitrosative stress, leading to protein nitration and lipid peroxidation [27] |

What is the relationship between ROS, oxidative stress, and antioxidants?

- Oxidative Stress: A condition characterized by an imbalance between the production of ROS and the ability of the biological system to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or repair the resulting damage [29].

- Antioxidants: Molecules that mitigate oxidative damage. They include enzymatic systems like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and peroxidases, as well as small molecules like glutathione (GSH) [27] [31]. It is critical to note that "antioxidant" is a broad term, and the specific chemistry, location, and concentration of each antioxidant must be considered when interpreting experiments [31].

The following diagram illustrates the core dynamic between ROS production, cellular defenses, and the resulting toxicological outcomes.

Diagram 1: ROS as a Central Modulator in Compound-Induced Toxicity.

Methodologies for ROS and Oxidative Damage Assessment

Accurately measuring ROS and oxidative damage is technically challenging due to the high reactivity and short half-lives of many species. The following section provides guidelines, protocols, and a critical comparison of common methods.

Direct ROS Measurement

Direct measurement aims to quantify the levels of specific ROS molecules in cells or tissues.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Direct ROS Detection Methods

| Method / Probe | Target ROS | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations & Artefacts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dihydroethidium (DHE) / MitoSOX Red | Superoxide (O₂•⁻) | Oxidation by O₂•⁻ forms fluorescent 2-hydroxyethidium (2-OH-E+) [32]. | MitoSOX is targeted to mitochondria. HPLC separation allows specific quantification of 2-OH-E+ [32]. | Simple fluorescence (e.g., microscopy) cannot distinguish 2-OH-E+ from other oxidation products; can overestimate O₂•⁻ [32]. |

| H2DCFDA (DCFH-DA) | Various (H₂O₂, ROO•, HO•) [33] [29] | Cell-permeable probe is hydrolyzed and oxidized to fluorescent DCF [33]. | Widely used; amenable to plate readers for throughput [33]. | Not specific for H₂O₂; subject to redox cycling and artificial signal amplification; metal- and peroxidase-sensitive [32]. |

| Amplex Red | Extracellular H₂O₂ | Horseradish peroxidase uses H₂O₂ to oxidize Amplex Red to fluorescent resorufin [32]. | Highly specific and sensitive for H₂O₂; good for measuring H₂O₂ release from cells or isolated organelles [32]. | Measures extracellular H₂O₂ only. Can be interfered with by O₂•⁻ or reducing agents like NADH [32]. |

| Electron Spin Resonance (ESR/EPR) | Radical species (O₂•⁻, HO•) | Directly detects molecules with unpaired electrons. Often used with spin traps (e.g., DMPO) [32] [34]. | Considered the "gold standard" for direct radical detection; provides structural information [34]. | Technically complex; requires specialized equipment. Spin traps (e.g., DMPO) can be toxic and react slowly [32]. |

| Genetically Encoded Sensors (e.g., roGFP, HyPer) | H₂O₂ (roGFP, HyPer) | roGFP has redox-sensitive disulfides; excitation ratio changes with oxidation [33]. | Subcellular targeting; minimal perturbation; ratiometric measurement reduces artefacts [33]. | Requires genetic manipulation; signal may be influenced by the local glutathione pool [33]. |

Expert Recommendation: No single method is perfect. The research community strongly recommends against relying solely on DCFH-DA as a measure for H₂O₂ due to its lack of specificity [31] [32]. For superoxide, the HPLC-based method for DHE is preferred over simple fluorescence imaging. The use of specific ROS generators and inhibitors is encouraged to corroborate findings [31].

Protocol: HPLC-Based Detection of Superoxide Using Dihydroethidium

This protocol provides a specific and quantitative method for measuring superoxide levels in cell cultures, critical for assessing compound-induced toxicity [32].

Principle: DHE is oxidized specifically by superoxide to form 2-hydroxyethidium (2-OH-E+). HPLC separation allows for the precise quantification of 2-OH-E+, distinguishing it from other fluorescent products like ethidium, which are formed by non-specific oxidation.

Materials:

- Dihydroethidium (DHE)

- Acetonitrile (HPLC grade)

- Phosphoric acid

- C18 reverse-phase HPLC column

- Cell culture samples (treated with test compounds)

- Microplate reader or fluorometer

Procedure:

- Cell Treatment & Staining: Culture cells in appropriate plates. After treatment with the compounds of interest, load cells with DHE (e.g., 5-50 µM) in buffer for 30-60 minutes at 37°C.

- Cell Extraction: Wash cells to remove excess probe. Lyse cells and precipitate proteins. Centrifuge and collect the supernatant containing the fluorescent products.

- HPLC Analysis: Inject the supernatant onto a C18 reverse-phase HPLC column.

- Mobile Phase: Use a gradient or isocratic elution with a solvent mixture such as acetonitrile and water (containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid or phosphoric acid).

- Detection: Use a fluorescence detector with excitation at 510 nm and emission at 595 nm.

- Quantification: Identify the peak for 2-OH-E+ by comparison with a pure standard if available. Quantify the peak area, which is proportional to the superoxide production in the sample.

Assessment of Oxidative Damage

Indirect measurement of ROS through the stable biomarkers of oxidative damage they leave behind is a reliable and widely used approach.

Lipid Peroxidation:

- Marker: Malondialdehyde (MDA) is a well-studied end product.

- Method: Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) assay. MDA reacts with TBA to form a pink chromophore measurable at 532 nm [29].

- Caveat: The TBARS assay can be non-specific. For greater accuracy, HPLC or GC-MS methods are recommended [29].

Protein Oxidation:

- Marker: Protein Carbonyls (PC).

- Method: Reaction of protein carbonyls with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) to form hydrazones, which can be measured spectrophotometrically at 375 nm or via Western blot (OxyBlot) [29].

DNA Damage:

- Marker: 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG).

- Method: Typically measured using ELISA kits or HPLC with electrochemical detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for ROS and Oxidative Stress Research

| Reagent / Kit Name | Primary Function | Brief Description & Utility in Toxicity Screening |

|---|---|---|

| H2DCFDA / carboxy-H2DCFDA | General ROS sensing | A ubiquitous, cell-permeable fluorescent probe for a broad range of ROS. Useful for initial, high-throughput compound screening despite specificity limitations [33] [29]. |

| MitoSOX Red | Mitochondrial superoxide sensing | A live-cell permeant probe targeted to mitochondria. Critical for assessing compounds suspected of inducing mitochondrial toxicity [33] [32]. |

| Amplex Red Assay Kit | Extracellular H₂O₂ quantification | A highly specific and sensitive assay for measuring H₂O₂ released from cells. Ideal for profiling compound effects on extracellular H₂O₂ production [32]. |

| GSH/GSSG-Glo Assay | Glutathione redox ratio | A luminescent assay to detect both reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG) glutathione. The GSH/GSSG ratio is a central indicator of cellular redox status and oxidative stress [35]. |

| ROS-Glo Assay | H₂O₂ measurement | A luminescent, H₂O2-sensitive assay designed for high-throughput screening. Uses a substrate that generates a luminescent signal proportional to H₂O₂ levels [35]. |

| MitoPQ | Mitochondrial superoxide generation | A research tool that generates O₂•⁻ within mitochondria. Used as a positive control or to study the consequences of site-specific superoxide production [31]. |

| d-Amino Acid Oxidase (DAAO) | Controlled intracellular H₂O₂ generation | A genetically encoded system that allows controlled, dose-dependent generation of H₂O₂ inside cells by adding d-alanine. Excellent for mechanistic studies of H₂O2-mediated toxicity [31]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My DCF fluorescence signal is very high, but other markers of oxidative stress (like protein carbonyls) are low. What could be the cause? This is a classic sign of artefactual signal generation from the DCFH-DA probe. The most likely cause is redox cycling, where the partially oxidized DCF radical reacts with oxygen to generate more superoxide and H₂O₂, artificially amplifying the signal [32]. Other causes include interference from cellular peroxidases or transition metals in your buffer.

- Solution: Do not rely on DCFH-DA alone. Confirm oxidative stress using a more specific method, such as measuring the GSH/GSSG ratio, protein carbonyls, or using a genetically encoded sensor like roGFP.

FAQ 2: I am using "antioxidants" like N-acetylcysteine (NAC) to test the role of ROS in a toxic response, but the results are unclear. Why? The term "antioxidant" is often used imprecisely. NAC is a poor direct scavenger of H₂O₂ [31]. Its primary effects may be through increasing cellular cysteine pools for glutathione synthesis, cleaving protein disulfides, or generating H₂S, rather than directly neutralizing ROS.

- Solution: Be specific about the antioxidant's proposed mechanism. Use a panel of tools: enzymatic antioxidants (e.g., catalase), specific scavengers, and genetic knockdown of ROS-producing enzymes like NOX to build a compelling case.

FAQ 3: How can I be sure that the superoxide signal I'm measuring with MitoSOX is real and not an artefact? Simple fluorescence microscopy or plate reader measurements with MitoSOX can be misleading, as the fluorescence can come from both the specific product (2-OH-E+) and non-specific oxidation products.

- Solution: The gold standard is to validate your findings using HPLC to separate and quantify the specific 2-OH-E+ adduct [32]. Alternatively, use specific pharmacological inhibitors of mitochondrial superoxide production or correlate with other mitochondrial dysfunction parameters.

FAQ 4: The inhibitors apocynin and diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) are often used to implicate NOX enzymes. Is this sufficient? No. Both apocynin and DPI are not specific to NADPH oxidases (NOX). DPI inhibits all flavoproteins, including mitochondrial complex I and nitric oxide synthases [31].

- Solution: Use more specific NOX inhibitors (if available) or, preferably, use genetic approaches such as siRNA knockdown or CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of specific NOX isoforms (e.g., NOX2, NOX4) to confirm their involvement.

The following workflow diagram integrates these troubleshooting concepts into a logical framework for diagnosing and resolving common ROS measurement issues.

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Workflow for Common ROS Measurement Issues.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary types of DNA damage my assays might detect, and what are their common causes? DNA damage can be broadly categorized based on its origin. Endogenous damage arises from within the cell, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) from metabolism, hydrolysis, and replication errors such as base mismatches or slippage at repetitive sequences [36]. Exogenous damage is caused by external agents like UV radiation (creating cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers), ionizing radiation (causing single- and double-strand breaks), and chemical agents (e.g., alkylating agents, crosslinking agents) [36].

Q2: Which DNA repair pathways are most critical to consider in the context of compound toxicity screening? Cells employ several major, substrate-specific repair pathways. The choice of assay can help infer which pathway is active. Key pathways include:

- Base Excision Repair (BER): Corrects small, non-helix-distorting base lesions, such as those caused by oxidation or alkylation [36].

- Nucleotide Excision Repair (NER): Addresses bulky, helix-distorting lesions, such as those induced by UV light [36].

- Mismatch Repair (MMR): Corrects errors of DNA replication, such as base-base mismatches and small insertion/deletion loops [36].

- Homologous Recombination (HR) & Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): These are the two main pathways for repairing DNA double-strand breaks, with HR being error-free and requiring a sister chromatid template, and NHEJ being error-prone [36].

Q3: My high-throughput genotoxicity screening results show inconsistencies. What could be the source? Inconsistencies in high-throughput screening (HTS) can stem from several factors:

- Experimental Condition Variability: Results are highly sensitive to species, administration route, and measurement indicators (e.g., LD50, TDLo) [37].

- Data Imbalance: Sparse data for specific target endpoints (e.g., human oral TDLo) can lead to poor model performance and unpredictable results [37].

- Compound-Specific Effects: The same compound can yield vastly different toxicity results under different testing conditions, making extrapolation challenging [37]. Using New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) that integrate in vitro and in silico data can help mitigate these issues and improve reliability [38] [39].

Q4: How can I leverage computational tools to reduce reliance on animal testing for genotoxicity assessment? Computational toxicology offers powerful alternatives:

- Machine Learning (ML) and AI: Models like graph convolution networks (GCNs) can predict acute toxicity by learning from chemical structure data and existing toxicological databases (e.g., TOXRIC, ToxValDB) [37] [38] [39].

- Integrated Testing Strategies: Frameworks like ToxACoL use an "Adjoint Correlation Learning" paradigm to model relationships between multiple toxicity endpoints, improving prediction accuracy for data-scarce endpoints and reducing the required training data by 70-80% [37].

- QSAR and Read-Across: Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models and read-across methods use existing data on similar chemicals to predict the toxicity of data-poor compounds [38] [39].

Troubleshooting Guides

The Comet Assay (Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis)

Purpose: To detect primary DNA damage at the level of single cells, including single- and double-strand breaks and alkali-labile sites [40] [41].

Table 1: Troubleshooting the Comet Assay

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background DNA Damage in control cells | 1. Apoptotic or necrotic cells.2. Excessive UV exposure during processing.3. Overly harsh cell processing (e.g., vigorous pipetting). | 1. Use viability assays to ensure >85% cell viability. Exclude apoptotic cells by morphology.2. Use yellow or red light for sample processing.3. Use wide-bore tips and handle cell suspensions gently. |

| No "Comet" Tails | 1. Insufficient DNA unwinding or electrophoresis.2. Inappropriate lysis conditions.3. Electrophoresis buffer pH is incorrect. | 1. Optimize unwinding time (typically 20-40 min). Ensure electrophoresis voltage and time are adequate (e.g., 0.7 V/cm for 30 min).2. Ensure fresh lysis solution is used and contains all necessary components (e.g., DMSO, Triton X-100).3. Calibrate pH meter; ensure buffer pH is >13 for alkaline comet assay. |

| Irregular or Streaky Comets | 1. Uneven agarose layer.2. Air bubbles trapped in agarose.3. Cells are not in a single plane. | 1. Ensure slides are perfectly horizontal while agarose sets.2. Carefully pipette agarose to avoid bubbles.3. Use a low concentration of cells and ensure they are well-suspended before embedding. |

| High Intra-Sample Variability | 1. Inhomogeneous cell suspension.2. Inconsistent electrophoresis conditions.3. Slide staining is uneven. | 1. Mix cell suspension thoroughly before embedding. Prepare multiple replicate slides.2. Ensure the electrophoresis tank is level and buffer volume is consistent and sufficient.3. Use a fluorescent DNA stain at the appropriate concentration and ensure slides are mounted evenly. |

In Vivo Micronucleus Assay

Purpose: To detect chromosomal damage and/or damage to the mitotic apparatus, resulting in the formation of micronuclei in erythrocytes or other cell types [40].

Table 2: Troubleshooting the Micronucleus Assay

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Frequency of Micronucleated Cells | 1. Insufficient dosing or sampling time.2. Bone marrow toxicity not considered.3. Inadequate number of cells scored. | 1. Confirm dose levels based on prior toxicity studies. Sample at appropriate times post-treatment (e.g., 24-48 hours for rodents).2. Monitor the proportion of immature (polychromatic) erythrocytes (PCE) to normochromatic erythrocytes (NCE). A decrease indicates bone marrow exposure.3. Score a minimum of 2000 PCEs per animal as per OECD guidelines. |

| High Variability Between Replicates | 1. Inconsistent animal handling or dosing.2. Subjective scoring criteria.3. Slide preparation artifacts. | 1. Standardize dosing procedures and randomize animal treatment.2. Use double-blinded scoring and train all scorers with reference images. Consider automated flow cytometry-based analysis [40].3. Follow standardized protocols for smear preparation and staining to ensure uniform cell distribution. |

| Difficulty Differentiating PCEs and NCEs | 1. Suboptimal staining.2. Use of an inappropriate stain. | 1. Use fresh Giemsa or acridine orange stain. Optimize staining time and concentration.2. Confirm the stain is suitable for distinguishing RNA (in PCEs) from DNA. |

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and Computational Models

Purpose: To rapidly assess the genotoxic potential of thousands of compounds using in vitro and in silico methods [38].

Table 3: Troubleshooting HTS and Computational Models

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Predictive Accuracy for Human Endpoints | 1. Model trained on imbalanced data (scarce human data).2. Failure to account for metabolic differences.3. Over-reliance on a single data type or assay. | 1. Use advanced ML paradigms like ToxACoL that use graph topology to model endpoint associations and transfer knowledge from data-rich to data-scarce endpoints [37].2. Incorporate in vitro metabolic activation systems (e.g., S9 mix) or use metabolic simulators in silico.3. Adopt an integrated weight-of-evidence approach using multiple assays and data sources (e.g., ToxValDB) to build consensus [38] [39]. |

| Model Fails to Generalize to New Chemical Classes | 1. The model is overfit to the training set.2. New chemicals are outside the model's "applicability domain". | 1. Use rigorous cross-validation and apply regularization techniques during model training. Ensure the training set is chemically diverse.2. Define the model's applicability domain (AD) using chemical descriptors. Flag predictions for compounds outside the AD for further scrutiny [37]. |

| Inconsistencies Between In Vitro and In Silico Results | 1. False positives/negatives in the HTS assay.2. The computational model does not capture the relevant biology. | 1. Confirm HTS results with a secondary, orthogonal assay (e.g., follow a positive Ames test with a micronucleus assay).2. Use mechanistic models that incorporate biological pathways, or multi-task models that learn from multiple toxicity endpoints simultaneously [37] [38]. |

Key Signaling Pathways in DNA Damage Response

The cellular response to DNA damage is a coordinated network of pathways that sense, signal, and repair lesions. Failure in these pathways is a hallmark of cancer and can be exploited in targeted therapies [42]. The diagram below illustrates the core DNA Damage Response (DDR) network.

Experimental Workflow for Genotoxicity Assessment

Integrating multiple assays provides a comprehensive view of a compound's genotoxic potential. The following workflow outlines a standard strategy for tiered genotoxicity testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Resources for Genotoxicity Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Tester Strains (S. typhimurium TA98, TA100, etc.) | Engineered strains sensitive to specific types of base-pair or frameshift mutations. | The core reagent for the Ames test to assess mutagenicity [40]. |

| Mouse Lymphoma Cells (L5178Y Tk+/−) | Mammalian cell line for detecting gene mutations (at the Tk locus) and chromosomal damage. | In vitro mouse lymphoma assay (MLA) [40]. |

| Acridine Orange / Giemsa Stain | Fluorescent (Acridine Orange) or histological (Giemsa) dyes that bind nucleic acids. | Differentiating immature and mature erythrocytes for scoring micronucleated PCEs in the micronucleus assay [40]. |

| Low-Melting Point Agarose | A low-gelling temperature agarose used to embed cells without causing significant additional DNA damage. | Matrix for immobilizing single cells in the comet assay [40] [41]. |

| Specific DNA Repair Enzyme Inhibitors | Small molecules that selectively inhibit key DNA repair proteins (e.g., PARP, DNA-PK, ATM/ATR inhibitors). | Used as positive controls or to probe synthetic lethal interactions in targeted cancer therapy research [42] [43]. |

| ToxValDB / TOXRIC Database | Curated databases of experimental and derived human health-relevant toxicity data for thousands of chemicals. | Used for benchmarking, chemical prioritization, and as a training resource for QSAR and machine learning models [37] [39]. |

| CRISPRi/a Libraries (e.g., SPIDR) | Libraries of guide RNAs for targeted gene knockdown or activation across the genome or specific gene sets like DNA repair. | Systematically mapping genetic interactions and synthetic lethality in the DNA Damage Response (DDR) [43]. |

A Practical Guide to Cell Viability Assays and High-Throughput Implementation

Navigating the OECD Classification of Cell Viability Methods

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the OECD classification for cell viability methods and why is it important? The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) provides a standardized classification system that categorizes cell viability assessment methods into distinct groups based on their operating principles. This classification is crucial for ensuring consistency, reliability, and regulatory compliance in scientific research, particularly in toxicology and drug development. The OECD guidelines are globally accepted and help validate results across different studies, making them essential for regulatory submissions of new drugs and chemicals [44].

2. What are the main categories of cell viability methods according to the OECD framework? The OECD classifies cell viability methods into four primary categories:

- Non-invasive cell structure damage assessment

- Invasive cell structure damage assessment

- Cell growth-based methods

- Cellular metabolism-based methods

Additionally, novel methods based on cell membrane potential have been identified as an emerging category beyond the current OECD classification [44].

3. How do I choose the most appropriate cell viability assay for my compound toxicity research? Selecting the optimal assay requires considering your specific experimental endpoints, available resources (instrumentation, budget, technical expertise), and the characteristics of your test compounds. Membrane integrity assays (like LDH or trypan blue) are ideal for detecting necrotic cell death, while metabolic assays (like MTT) better reflect cellular health. Apoptosis-specific assays (caspase activation, annexin V) are preferable when studying programmed cell death pathways. Always validate your method with positive and negative controls relevant to your toxicity model [44].

4. What are common pitfalls in cell viability assessment and how can I avoid them? Common issues include false positives/negatives due to assay interference, background signals in LDH assays, dye leakage in membrane permeability assays, and metabolic activity changes unrelated to viability. To minimize these problems: use multiple assay types to confirm results, include appropriate controls, optimize incubation times to prevent dye toxicity, consider compound characteristics that might interfere with assay chemistry, and validate methods against morphological assessment [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Results in Membrane Integrity Assays

Problem: Variable results when using trypan blue or propidium iodide staining.

Solutions:

- Shorten incubation time: Prolonged incubation with trypan blue can lead to false positives as dye aggregates dissociate and penetrate viable cells. Keep incubation periods brief [44].

- Check osmolarity: Changes in solution osmolarity can cause spontaneous dye penetration into otherwise viable cells, generating false positives [44].

- Use fresh dyes: Prepare new dye solutions regularly as aging dyes can form aggregates that affect staining specificity.

- Combine with other methods: Confirm results with a metabolic activity assay to distinguish between true membrane damage and artifactual staining.

Issue 2: High Background in LDH Assay

Problem: Elevated background signals in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assays.

Solutions:

- Centrifuge samples properly: Ensure complete removal of cells and debris before measuring supernatant LDH activity.

- Account for serum LDH: Fetal bovine serum contains LDH; use serum-free media during the assay period or subtract appropriate background controls.

- Check compound interference: Some test compounds might inhibit or enhance LDH activity; include appropriate controls without cells to detect interference.

- Validate in your system: LDH may underestimate cytotoxicity in certain co-culture systems; confirm with an alternative viability method [44].

Issue 3: Discrepancies Between Metabolic and Membrane Integrity Assays

Problem: Different viability conclusions when comparing MTT/ATP assays with membrane dye exclusion.

Solutions:

- Consider biological context: Metabolic assays measure different aspects of cell health than membrane integrity assays. Senescent or quiescent cells may show reduced metabolic activity with intact membranes.

- Check assay timing: Early apoptosis may preserve metabolic activity despite membrane changes.

- Use multiple endpoints: Combine different assay types to gain comprehensive understanding of cell status.

- Include morphological assessment: Use microscopy to visually confirm cell health and identify potential confounding factors.

OECD Cell Viability Method Comparison

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Major Cell Viability Assessment Methods

| OECD Category | Specific Method | Measurement Principle | Common Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Cell Damage (Non-invasive) | LDH Release | Measures lactate dehydrogenase enzyme released from damaged cells | General cytotoxicity screening, high-throughput compound testing | High background in some systems, may underestimate cytotoxicity in co-cultures [44] |

| Adenylate Kinase (AK) Release | Detects AK enzyme released through compromised membranes | High-throughput toxicology | Potential leakage from stressed but viable cells | |

| Structural Cell Damage (Invasive) | Trypan Blue Exclusion | Dye penetration into membrane-compromised cells | Basic research, cell culture maintenance | False positives with prolonged incubation, underestimation of dead cells with short incubation [44] |

| Propidium Iodide Staining | DNA binding in cells with permeable membranes | Flow cytometry, apoptosis studies | Potential false positives from membrane invagination [44] | |

| Esterase Cleavage Assays (Calcein-AM) | Enzymatic conversion of non-fluorescent to fluorescent compounds | Live cell imaging, viability tracking | Dye leakage from viable cells, measures enzyme activity rather than direct viability [44] | |

| Cell Growth | Population Doubling | Increase in cell number over time | Long-term toxicity studies, cancer research | Does not detect non-dividing viable cells |

| Cellular Metabolism | MTT/MTS/XTT Assays | Mitochondrial reductase activity | Drug screening, toxicology | Affected by metabolic changes unrelated to viability [44] |

| ATP Assay | Cellular ATP levels | High-throughput screening, rapid toxicity assessment | Sensitive to handling conditions, requires cell lysis | |

| Beyond OECD Classification | Membrane Potential Assays | Changes in transmembrane electrical potential | Early apoptosis detection, mechanistic studies | Emerging methods, less standardized [44] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Viability Assessment

| Reagent/Kit | Manufacturer | Function | Compatible Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| ToxiLight BioAssay Kit | LONZA | Detects adenylate kinase (AK) release from damaged cells | Luminescence reader [44] |

| CytoTox Assay | Promega | Measures dead-cell protease activity released from compromised cells | Fluorescence microplate reader [44] |

| aCella-TOX | Promega | Detects Glyceraldehyde-3 Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G3PDH) release | Colorimetric microplate reader [44] |

| Vybrant/CyQUANT Cytotoxicity Assay | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Measures Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) release | Fluorescence microplate reader [44] |

| SYTOX Dead Cell Stains | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Nucleic acid staining of membrane-compromised cells | Flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy [44] |

| CellTox Green Cytotoxicity Assay | Promega | DNA-binding dye for dead cells | Fluorescence microplate reader, imaging [44] |

| Life/dead Kit | Thermo-Fisher Scientific | Dual staining combining membrane integrity and esterase activity | Flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy [44] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: LDH Release Assay for Compound Toxicity Screening

Principle: Measures lactate dehydrogenase release from cells with compromised membranes [44].

Materials:

- LDH assay kit

- Clear 96-well plate

- Microplate reader capable of measuring 490-500 nm absorbance

- Compound treatment plates

- Centrifuge

Procedure:

- Seed cells in 96-well plates at optimal density and incubate for 24 hours.

- Treat cells with test compounds at appropriate concentrations, including vehicle controls and lysis controls (for maximum LDH release).

- Following treatment period (typically 24-48 hours), centrifuge plates at 250 × g for 10 minutes.

- Transfer 50 µL of supernatant from each well to a new clear 96-well plate.

- Add 50 µL of reaction mixture from LDH assay kit to each well.

- Incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

- Measure absorbance at 490-500 nm, subtracting reference wavelength at 680 nm.

- Calculate percentage cytotoxicity: (Test compound LDH - Spontaneous LDH) / (Maximum LDH - Spontaneous LDH) × 100

Troubleshooting Notes: High background may occur with serum-containing media; consider serum-free conditions during assay. Some nanomaterials interfere with LDH measurement; validate with alternative methods [44].

Protocol 2: Trypan Blue Exclusion for Rapid Viability Assessment

Principle: Membrane-impermeant dye enters and stains dead cells with compromised membranes [44].

Materials:

- 0.4% Trypan blue solution

- Hemocytometer or automated cell counter

- PBS for dilution

- Microcentrifuge tubes

Procedure:

- Harvest cells by gentle trypsinization or scraping.

- Centrifuge cell suspension at 150 × g for 5 minutes and resuspend in PBS.

- Mix 10 µL of cell suspension with 10 µL of 0.4% trypan blue solution.

- Incubate for exactly 1-3 minutes (do not exceed 5 minutes).

- Load mixture onto hemocytometer or automated cell counter slide.

- Count unstained (viable) and blue-stained (non-viable) cells.

- Calculate viability percentage: Viable cells / Total cells × 100

Troubleshooting Notes: Strictly control incubation time as prolonged exposure can lead to false positives. For automated counters, validate settings with manual counting. For adherent cells, ensure complete detachment without causing additional damage [44].

Method Selection Workflow

Method Selection Workflow: This diagram outlines a systematic approach for selecting the most appropriate cell viability assay based on experimental requirements and constraints.

OECD Classification Framework

OECD Classification Framework: This diagram illustrates the hierarchical structure of the OECD classification system for cell viability assessment methods, including the five main categories and their specific methodologies.

Assay Selection Guide & Comparison

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How do I choose the right assay for my cell health assessment study? The choice depends on your experimental goals, cell type, and required throughput. For high-throughput screening where sensitivity and speed are critical, ATP-based luminescence assays are superior. For standard colorimetric measurement in academic settings with ample time, MTT is a common choice. If you want a simpler "add-mix-measure" colorimetric protocol, consider MTS, XTT, or WST-1 assays. [4] [45]

Q2: My MTT assay shows high background; what could be the cause? High background in MTT assays can result from several factors:

- Chemical interference from reducing compounds in your test compounds (ascorbic acid, sulfhydryl compounds)

- Exposure of MTT reagent to light or elevated pH during storage

- Microbial contamination in cell cultures

- Incomplete solubilization of formazan crystals Run appropriate controls without cells to test for chemical interference. [4] [45]

Q3: Why does my ATP assay show higher sensitivity compared to tetrazolium-based assays? ATP assays utilize luminescent detection, which generally offers greater sensitivity than colorimetric absorbance methods used in tetrazolium assays. While tetrazolium reduction assays typically detect 200-1,000 cells per well, luminescent ATP assays can detect fewer cells, making them more suitable for miniaturization and high-throughput applications. [45]

Q4: Can I multiplex these viability assays with other endpoints? Yes, but with considerations. The MTT assay requires solubilization solutions that destroy cell architecture, limiting multiplexing options unless the other assay is performed first. ATP assays involve cell lysis, making them endpoint measurements. For multiplexing, consider less destructive assays like the CellTiter-Fluor Assay, which measures protease activity, or the RealTime-Glo Assay, which allows continuous monitoring. [45]

Comparative Assay Characteristics

Table 1: Key characteristics of metabolic activity assays

| Assay Parameter | MTT | MTS/XTT/WST-1 | ATP-based Luminescence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Method | Colorimetric (Absorbance) | Colorimetric (Absorbance) | Luminescence |

| Detection Sensitivity | 200-1,000 cells/well | 200-1,000 cells/well | Higher than tetrazolium assays |

| Assay Steps | Two-step procedure | Homogeneous "add-mix-measure" | Add-mix-measure |

| Incubation Time | 1-4 hours | 1-4 hours | 10 minutes to several hours |

| Signal Stability | Requires prompt reading | More stable than MTT | Stable for extended periods |

| Multiplexing Potential | Limited | Moderate | Limited (lytic method) |

| Key Limitations | Formazan solubilization required; chemical interference; reagent toxicity | Still susceptible to chemical interference | Luciferase enzyme inhibitors may interfere |

| Best Applications | Academic research; endpoint measurements | Higher-throughput colorimetric screening | High-throughput screening; maximal sensitivity |

Table 2: Troubleshooting common assay problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Signal | Chemical reducing compounds; contaminated reagents; microbial contamination | Include no-cell controls; filter-sterilize reagents; use fresh solutions |

| Low Signal Intensity | Insufficient cells; suboptimal incubation time; loss of metabolic activity | Optimize cell seeding density; extend incubation time (avoiding toxicity); ensure cells in log growth phase |

| Poor Reproducibility | Inconsistent cell seeding; uneven solubilization; edge effects in plates | Standardize cell preparation; ensure complete formazan dissolution; use plate seals to prevent evaporation |

| Abnormal Cell Morphology | Cytotoxicity of assay reagents | Reduce MTT concentration or incubation time; consider less toxic alternatives |

Experimental Protocols

MTT Assay Protocol

The MTT assay measures the reduction of yellow tetrazolium salt to purple formazan crystals by metabolically active cells. [4] [46]

Reagent Preparation:

- MTT Solution: Dissolve MTT in DPBS to 5 mg/mL. Filter-sterilize (0.2 µm), protect from light, and store at 4°C. [4]

- Solubilization Solution: Prepare 40% dimethylformamide with 16% SDS in 2% glacial acetic acid, pH 4.7. [4]

Procedure for Adherent Cells:

- Plate cells in 96-well plates at optimized density (typically 1,000-100,000 cells/well). [46]

- Apply experimental treatments for desired duration.

- Add MTT solution to each well (final concentration 0.2-0.5 mg/mL).

- Incubate 2-4 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂ until purple formazan crystals are visible.

- Carefully aspirate MTT solution without disturbing crystals.

- Add solubilization solution (DMSO, acidified isopropanol, or SDS solution).

- Agitate plate gently to completely dissolve crystals.

- Measure absorbance at 570 nm with reference wavelength of 630 nm. [4] [46]

Procedure for Suspension Cells:

- After treatment, centrifuge plate at 1,000 × g for 5 minutes.

- Aspirate supernatant carefully.

- Add MTT solution and resuspend cell pellet gently.

- Incubate 2-4 hours at 37°C.

- Centrifuge again to pellet cells with formazan crystals.

- Aspirate supernatant and add solubilization solution.

- Measure absorbance at 570 nm. [46]

ATP Assay Protocol

ATP assays measure cellular ATP content using luciferase enzyme, which produces light proportional to ATP concentration.

Procedure:

- Culture cells in white-walled multiwell plates to minimize light scattering.

- Apply experimental treatments.

- Equilibrate CellTiter-Glo Reagent to room temperature.

- Add equal volume of reagent to each well.

- Mix contents for 2 minutes on orbital shaker to induce cell lysis.

- Allow plate to incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes to stabilize signal.

- Measure luminescence using plate-reading luminometer. [45]

Assay Workflow Visualization

MTT Assay Workflow

ATP Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| MTT Tetrazolium Salt | Substrate reduced by metabolically active cells to formazan | Light-sensitive; prepare fresh or store protected from light; cytotoxic at high concentrations |

| DMSO or Alternative Solvents | Dissolves formazan crystals for absorbance measurement | Use pure, sterile solvents; potential cytotoxicity at high concentrations |

| CellTiter-Glo Reagent | Luciferase-based system for ATP detection | Equilibrate to room temperature before use; compatible with multiwell formats |

| 96-Well Microplates | Cell culture and assay measurement | Use flat-bottom plates for adherence; white-walled for luminescence |

| Plate Reader | Detect absorbance or luminescence signals | Ensure proper calibration and wavelength selection (570 nm for MTT) |

| Sterile PBS | Physiological buffer for reagent preparation | Maintain pH at ~7.4 for optimal MTT stability and activity |

Advanced Technical Notes

Mechanistic Insights: While historically believed to measure specifically mitochondrial activity, MTT reduction occurs in multiple cellular compartments including mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and plasma membrane. The assay reflects overall cellular metabolic activity and reducing power, primarily through NADH or similar reducing molecules. [4] [46] [45]

Metabolic Considerations: Tetrazolium reduction assays measure metabolic activity, not directly cell number. Culture conditions that alter metabolism (pH, glucose depletion, confluence) will affect reduction rates independent of cell number. Activated or rapidly dividing cells show higher reduction rates per cell than quiescent cells. [4] [45]

Toxicity Testing Application: In compound toxicity filtering research, these assays provide crucial data on cell health after compound exposure. Understanding each assay's mechanism ensures appropriate interpretation—what affects metabolic activity might not immediately affect ATP levels, and vice versa. For comprehensive assessment, consider orthogonal methods measuring different viability markers. [4] [45]